Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 6

September 25, 2017

Clothing fashions during the Dyers' lifetime--part 1

This post is the first of two, on fashions of the early and mid-17th century, during the lifetimes of William and Mary Barrett Dyer and Anne and William Hutchinson. I tried to cover the various social strata, whose type of clothes were prescribed. For instance, shoe height had to be low for the poorer sorts, and gowns or men's boots had to match their station.

Since Mary and William Dyer were respected and in a higher merchant class, as well as William's social status as colonial attorney general, they wouldn't be wearing court dress of the aristocrats, but they'd be very well turned out with fabrics, colors, and ornaments like collars and hats.

When they moved from London to Boston, they probably wore more sober Puritan dress, but even so, it would have been of high quality, with laces and quality boots to show their status and educational level. But for some years, there were no riding horses or carriages, so most people, even Gov. John Winthrop, walked for miles in sunshine, rain, or snow.

When they moved to Rhode Island, they would have added clothing that would be practical for their farming and sailing activities, though they certainly would have had servants and laborers to do heavier chores than feeding poultry or milking goats. Of course, William would have had courtroom clothes (and possibly a wig), and Mary would have dressed plainly when she became a Quaker in the 1650s. Plain doesn't mean shabby, though--unless you think of living in the same clothes for weeks or months at a time while in prison.

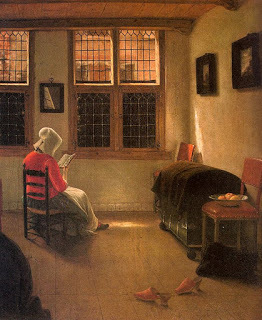

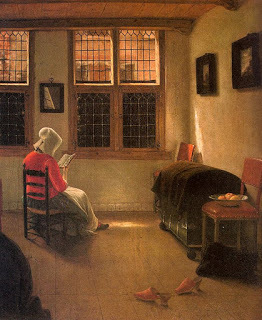

1. 1660s: Dutch woman reading (detail), by Pieter Janssens Elinga

1. 1660s: Dutch woman reading (detail), by Pieter Janssens Elinga

2. ca 1600: Bartholomew family group--grandparents, parents, and children.

2. ca 1600: Bartholomew family group--grandparents, parents, and children.

Two of the boys emigrated to Massachusetts as young adults.

I'm not sure, but this may be the Bartholomew family

who were friends with William and Anne Hutchinson

in London, but turned against Anne in Boston. Their clothes

indicate they were respected members of society, and the

deep black shows their wealth. (It was difficult to match black pieces,

and they tended to fade with cleaning.) 3. About 1615: Lady Arabella Stuart, falsely claimed to

3. About 1615: Lady Arabella Stuart, falsely claimed to

be Mary Dyer's biological mother. 4. 1630: Four Figures at Table, by Louis Le Nain

4. 1630: Four Figures at Table, by Louis Le Nain

5. 1620s-30s: Netherlands Family Making Music, Molenaer

5. 1620s-30s: Netherlands Family Making Music, Molenaer

6. 1600s- Cecelia, by Bernardo Strozzi

6. 1600s- Cecelia, by Bernardo Strozzi

7. 1615-Frances Howard, Countess Somerset

7. 1615-Frances Howard, Countess Somerset

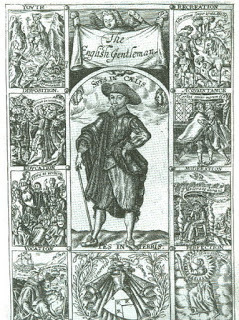

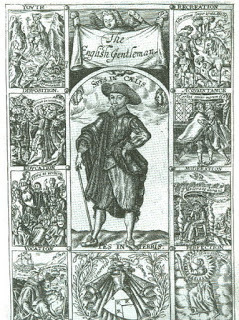

8. In 1630 London, this was the suggested "look" for the

8. In 1630 London, this was the suggested "look" for the

English gentleman. Click photo to enlarge, so you can

see the smaller images around the border. 9. 1630s: English satin evening dress.

9. 1630s: English satin evening dress.

This is how Queen Henrietta Maria dressed. 10. 1630s-40s: Country woman

10. 1630s-40s: Country woman

11. 1630s-40s: Lady of the court

11. 1630s-40s: Lady of the court

12. 1630s-40s: English dress with lace shawl collar, fur muff

12. 1630s-40s: English dress with lace shawl collar, fur muff

13. 1630s-40s: English gentlewoman

13. 1630s-40s: English gentlewoman

14. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif (woman's cap)

14. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif (woman's cap)

15. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif

15. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif

16. 1630s-40s: Merchant's wife of London

16. 1630s-40s: Merchant's wife of London

17. 1630: Helene Fourment in her wedding gown. She was married to

17. 1630: Helene Fourment in her wedding gown. She was married to

painter Peter-Paul Rubens. 18. The Jewish Bride, by Rembrandt van Rijn. This may be

18. The Jewish Bride, by Rembrandt van Rijn. This may be

a depiction of the biblical patriarch Isaac with his bride Rebekah,

but it shows how a bride would dress in 17th-century Netherlands.

In fact, author Donald Michael Platt discovered that the male model

for this painting was Vicente Rocamora, the subject of his historical novels! 19. Anabaptist family, suppertime. Unknown year and country.

19. Anabaptist family, suppertime. Unknown year and country.

20. 1630s-Queen Henrietta Maria of England.

20. 1630s-Queen Henrietta Maria of England.

Note the crown near her left hand. 21. 1630-35: Family group in a landscape, England

21. 1630-35: Family group in a landscape, England

22. 1647- Portrait of Lady Mary Fairfax (1638-1704), aged nine,

22. 1647- Portrait of Lady Mary Fairfax (1638-1704), aged nine,

with her tutor, by Robert Walker (1607-60). Lady Mary

was the daughter of General (Lord) Thomas Fairfax of the English Civil Wars.

The girl went on to become Lady Mary Villiers, Duchess of Buckingham. 23. 1630s-woman's shoe height related to societal status

23. 1630s-woman's shoe height related to societal status

24. 1633: Henrietta Maria of France, Queen consort of England.

24. 1633: Henrietta Maria of France, Queen consort of England.

A Catholic, she dressed more modestly than many Anglican

and Puritan women of her time.

Part two of two on this subject coming soon!

************************************

Christy K Robinson is the author of the books:

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2017)

Since Mary and William Dyer were respected and in a higher merchant class, as well as William's social status as colonial attorney general, they wouldn't be wearing court dress of the aristocrats, but they'd be very well turned out with fabrics, colors, and ornaments like collars and hats.

When they moved from London to Boston, they probably wore more sober Puritan dress, but even so, it would have been of high quality, with laces and quality boots to show their status and educational level. But for some years, there were no riding horses or carriages, so most people, even Gov. John Winthrop, walked for miles in sunshine, rain, or snow.

When they moved to Rhode Island, they would have added clothing that would be practical for their farming and sailing activities, though they certainly would have had servants and laborers to do heavier chores than feeding poultry or milking goats. Of course, William would have had courtroom clothes (and possibly a wig), and Mary would have dressed plainly when she became a Quaker in the 1650s. Plain doesn't mean shabby, though--unless you think of living in the same clothes for weeks or months at a time while in prison.

1. 1660s: Dutch woman reading (detail), by Pieter Janssens Elinga

1. 1660s: Dutch woman reading (detail), by Pieter Janssens Elinga

2. ca 1600: Bartholomew family group--grandparents, parents, and children.

2. ca 1600: Bartholomew family group--grandparents, parents, and children. Two of the boys emigrated to Massachusetts as young adults.

I'm not sure, but this may be the Bartholomew family

who were friends with William and Anne Hutchinson

in London, but turned against Anne in Boston. Their clothes

indicate they were respected members of society, and the

deep black shows their wealth. (It was difficult to match black pieces,

and they tended to fade with cleaning.)

3. About 1615: Lady Arabella Stuart, falsely claimed to

3. About 1615: Lady Arabella Stuart, falsely claimed to be Mary Dyer's biological mother.

4. 1630: Four Figures at Table, by Louis Le Nain

4. 1630: Four Figures at Table, by Louis Le Nain

5. 1620s-30s: Netherlands Family Making Music, Molenaer

5. 1620s-30s: Netherlands Family Making Music, Molenaer

6. 1600s- Cecelia, by Bernardo Strozzi

6. 1600s- Cecelia, by Bernardo Strozzi

7. 1615-Frances Howard, Countess Somerset

7. 1615-Frances Howard, Countess Somerset

8. In 1630 London, this was the suggested "look" for the

8. In 1630 London, this was the suggested "look" for the English gentleman. Click photo to enlarge, so you can

see the smaller images around the border.

9. 1630s: English satin evening dress.

9. 1630s: English satin evening dress. This is how Queen Henrietta Maria dressed.

10. 1630s-40s: Country woman

10. 1630s-40s: Country woman

11. 1630s-40s: Lady of the court

11. 1630s-40s: Lady of the court

12. 1630s-40s: English dress with lace shawl collar, fur muff

12. 1630s-40s: English dress with lace shawl collar, fur muff

13. 1630s-40s: English gentlewoman

13. 1630s-40s: English gentlewoman

14. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif (woman's cap)

14. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif (woman's cap)

15. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif

15. 1630s-40s: English, modest dress and coif

16. 1630s-40s: Merchant's wife of London

16. 1630s-40s: Merchant's wife of London

17. 1630: Helene Fourment in her wedding gown. She was married to

17. 1630: Helene Fourment in her wedding gown. She was married to painter Peter-Paul Rubens.

18. The Jewish Bride, by Rembrandt van Rijn. This may be

18. The Jewish Bride, by Rembrandt van Rijn. This may be a depiction of the biblical patriarch Isaac with his bride Rebekah,

but it shows how a bride would dress in 17th-century Netherlands.

In fact, author Donald Michael Platt discovered that the male model

for this painting was Vicente Rocamora, the subject of his historical novels!

19. Anabaptist family, suppertime. Unknown year and country.

19. Anabaptist family, suppertime. Unknown year and country.

20. 1630s-Queen Henrietta Maria of England.

20. 1630s-Queen Henrietta Maria of England. Note the crown near her left hand.

21. 1630-35: Family group in a landscape, England

21. 1630-35: Family group in a landscape, England

22. 1647- Portrait of Lady Mary Fairfax (1638-1704), aged nine,

22. 1647- Portrait of Lady Mary Fairfax (1638-1704), aged nine, with her tutor, by Robert Walker (1607-60). Lady Mary

was the daughter of General (Lord) Thomas Fairfax of the English Civil Wars.

The girl went on to become Lady Mary Villiers, Duchess of Buckingham.

23. 1630s-woman's shoe height related to societal status

23. 1630s-woman's shoe height related to societal status

24. 1633: Henrietta Maria of France, Queen consort of England.

24. 1633: Henrietta Maria of France, Queen consort of England.A Catholic, she dressed more modestly than many Anglican

and Puritan women of her time.

Part two of two on this subject coming soon!

************************************

Christy K Robinson is the author of the books:

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2017)

Published on September 25, 2017 20:07

September 15, 2017

Autographed books on Mary Dyer, less expensive than Amazon!

Limited number of author-signed books now available!

I have available 10 two-volume sets of my biographical* novels,

Mary Dyer Illuminated

and

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

, that I will personalize for you or your gift recipient.

Limited number of author-signed books now available!

I have available 10 two-volume sets of my biographical* novels,

Mary Dyer Illuminated

and

Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This

, that I will personalize for you or your gift recipient. The retail (unsigned) price on Amazon is $20 each, plus shipping. But I will sign and ship them to US addresses as a pair, for $36 postage paid.

The story is told in two volumes because having researched Mary Dyer for years, I couldn’t write her story without her extremely remarkable husband, William Dyer. No one has written of his accomplishments until I did, perhaps because he was overshadowed by Mary’s famous death.

The story is told in two volumes because having researched Mary Dyer for years, I couldn’t write her story without her extremely remarkable husband, William Dyer. No one has written of his accomplishments until I did, perhaps because he was overshadowed by Mary’s famous death. At the end of the second volume, there’s a nonfiction section that ties off the stories of all the characters and the Dyer children, and discusses what happened after Mary’s execution on the Boston gallows in 1660.

Additionally, there are 10 copies of a companion volume, the nonfiction The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport, that I will sign and mail to US addresses for $14.

If interested, please leave your name in my website contact form(<--click link) and I’ll email and then invoice you through PayPal, allowing you to pay securely with a bank card or from your checking account.

HURRY! I only have these few books on hand, and they go first-come, first-served, along with a bookmark photo of William Dyer's letter about his condemned wife.

*****

*What is a biographical novel? Among my author colleagues, it's defined as a book that's been researched as a biography, but with dialogue and scenes included (necessarily called fiction), and some deep thinking about what motives passed through our subjects' minds that moved them to their larger-than-life events. The 1994 book, Mary Dyer, Biography of a Rebel Quaker, by Ruth Plympton, was a biographical novel, in that she speculated on a number of events and included the notion that Mary Dyer was the child of royalty--which had been soundly refuted by historians 50 years before Plympton dredged it up again.

In the case of these Mary Dyer novels, I researched hundreds of modern and 17th-century books, medical papers, epidemiology, astronomy, climate and weather, John Winthrop's books, journals and letters of the time, tavern ballads, the theology position papers of John Cotton and Roger Williams, the court records of Anne Hutchinson's trials, short genealogies of every character, English and Dutch maps of the era, information on the Native Americans around Narragansett Bay, the culture of white, Native, and African slavery, the records of the English secretary of state and spymaster, and many other fascinating documents--and then wrote Mary's and William's story without it being an info-dump, or for the villains to be flat cartoons instead of fleshed-out human beings.

Thank you for your support! Christy K Robinson

Thank you for your support! Christy K RobinsonChristy K Robinson is the author of the books:

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2017)

Published on September 15, 2017 01:35

September 5, 2017

Big respect for a departed friend, Carolina Capehart

I was saddened to learn today of the passing of a friend of several years, Carolina M Capehart.

Carolina Capehart, my friend because we both

Carolina Capehart, my friend because we both

love history, and came together because of

this Dyer blog. Rest in peace.

Carolina was a food historian and hearth-cooking expert, who could be relied upon for good advice in research and writing on foods, menus, and cooking in the 17th-19th centuries. I sometimes consulted her for my Dyer research and for this blog.

Over the seven years I knew her online, she was a frequent presence on the Mary Barrett Dyer profile, and she commented often in this blog.

I tried to convert her to the joys of green chilies, even mild ones, but she would have none of it. There was no way she'd adulterate her corn pudding with a nice, juicy pasilla or Anaheim diced in.

"I'm pretty much stuck in my ways," she said. "Besides, I'm too old to start experimenting now! LOL oy."

Carolina said "LOL oy" a lot. It was like she’d hit her funny bone on the table. She also ruefully cussed with "Dagnabbit."

Carolina was an actress in her youth, and as an adult was a historical reenactor or interpreter. She taught hearth-cooking and fed samples to countless thousands of people in historical houses or battlefields, Colonial Williamsburg, and other places.

She wrote to me, “I always follow a recipe from an historic cookbook. The other thing is...I don't cook...as in modern cooking...it's Stouffer's frozen entrees for me! Or 5 Guys. Or KFC popcorn chicken. Maybe a steak now 'n then. YUM! The only way to go. I may render my own lard, but I sure ain't gonna spend much time cooking my own meals.”

She passed away in April 2017.

Her friends don't know why she passed, and might never learn, for her Christian Science denomination doesn't talk about illness and death, and there's no post from a relative on her Facebook page. I had messaged her and didn't receive an answer, but assumed she was taking a break from Facebook.

If you have an interest in historic cookery, visit Carolina's blog. She was an excellent writer (don't judge by our informal messages above). https://firesidefeasts.wordpress.com/about/

So as you think about your ancestors and how they might have lived, how they cooked and what they ate, think kindly of Carolina and remember her.

*****

Here's an article on Carolina and her work: http://www.brooklynpaper.com/stories/31/26/31_26_vintage_victuals.html

Carolina Capehart, my friend because we both

Carolina Capehart, my friend because we bothlove history, and came together because of

this Dyer blog. Rest in peace.

Carolina was a food historian and hearth-cooking expert, who could be relied upon for good advice in research and writing on foods, menus, and cooking in the 17th-19th centuries. I sometimes consulted her for my Dyer research and for this blog.

Over the seven years I knew her online, she was a frequent presence on the Mary Barrett Dyer profile, and she commented often in this blog.

I tried to convert her to the joys of green chilies, even mild ones, but she would have none of it. There was no way she'd adulterate her corn pudding with a nice, juicy pasilla or Anaheim diced in.

"I'm pretty much stuck in my ways," she said. "Besides, I'm too old to start experimenting now! LOL oy."

Carolina said "LOL oy" a lot. It was like she’d hit her funny bone on the table. She also ruefully cussed with "Dagnabbit."

Carolina was an actress in her youth, and as an adult was a historical reenactor or interpreter. She taught hearth-cooking and fed samples to countless thousands of people in historical houses or battlefields, Colonial Williamsburg, and other places.

She wrote to me, “I always follow a recipe from an historic cookbook. The other thing is...I don't cook...as in modern cooking...it's Stouffer's frozen entrees for me! Or 5 Guys. Or KFC popcorn chicken. Maybe a steak now 'n then. YUM! The only way to go. I may render my own lard, but I sure ain't gonna spend much time cooking my own meals.”

She passed away in April 2017.

Her friends don't know why she passed, and might never learn, for her Christian Science denomination doesn't talk about illness and death, and there's no post from a relative on her Facebook page. I had messaged her and didn't receive an answer, but assumed she was taking a break from Facebook.

If you have an interest in historic cookery, visit Carolina's blog. She was an excellent writer (don't judge by our informal messages above). https://firesidefeasts.wordpress.com/about/

So as you think about your ancestors and how they might have lived, how they cooked and what they ate, think kindly of Carolina and remember her.

*****

Here's an article on Carolina and her work: http://www.brooklynpaper.com/stories/31/26/31_26_vintage_victuals.html

Published on September 05, 2017 19:34

August 31, 2017

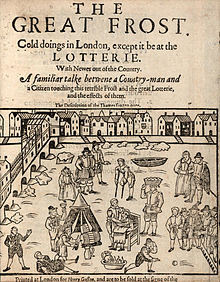

The Great Frost of 1608

As a few of you know, I'm researching and writing a nonfiction book about Anne Marbury Hutchinson. I haven't posted blog articles very often over the months of research and writing, and trying to make a living. Someone who negatively reviewed one of my Dyer books complained that some of the articles were taken from this Dyer blog and were unsupported with references, because I didn't provide a bibliography. So I've removed articles from this blog, to make the book even more exclusive. When I researched the Dyer books, I read literally hundreds of books and scholarly papers about their culture, beliefs, and practices, spoke with experts and scholars, and I visited the places in the books.

In the forthcoming Hutchinson book, there's a very long bibliography. This article, actually a chapter of the Hutchinson book, is about an event that took place when Anne Marbury (not yet Hutchinson) was a teenager living with her family in London. Her father was a popular minister and had authority over several churches at the time.

I will probably remove this chapter from the blog, or severely edit it when the book is published, but as with the other books, I wanted to give you a taste of the book and an opportunity for input (in the comments).

In the meantime, it's really, really hot, and I hope this article will help you forget for a few minutes. Cheers!

PS: This is the sixth anniversary of the Dyer blog. Thank you for visiting and clicking the articles and links. At the moment, the page views are 471,634. Half a million is only a few days away!

The Great Frost © 2017 by Christy K Robinson

T he Great Frost of 1608 began in December 1607, when a massive freeze descended on Great Britain, Iceland, and Europe. It enveloped city and country alike, freezing animals and people, stopping trading ships, sending icebergs on the North Sea between England and the Continent, and freezing seaports so that coastal shipping trade came to a stop for three months.

“The first decade of the 17th century was marked by a rapid cooling of the Northern Hemisphere, with some indications for global coverage. A burst of volcanism and the occurrence of El Niño seem to have contributed to the severity of the events. … Additional paleoclimatic, global evidence testifies for an equatorward shift of global wind patterns as the world experienced an interval of rapid, intense, and widespread cooling.” Schimmelrnann, Lange, Zhao, and Harvey, abstract, http://aquaticcommons.org/14822/1/Arndt%20Schimmelmann.pdf The Peruvian silica volcano, Huaynaputina, erupted in 1600, with so much ejecta that more than 12 cubic miles of rock and ash filled the atmosphere, causing rapid global cooling and catastrophic weather events for a decade, including a Russian famine that killed two million people, epic mud flows in California, great droughts and freezes that affected the Popham and Jamestown colonies in Virginia, and die-offs in European vineyards. The far-off Peruvian volcano affected Great Britain, too.

A succession of hot, dry summers and extra-cold winters in England heralded the coldest years of the Little Ice Age in the seventeenth century. No one knew it then, of course. They just knuckled down and got on with survival.

In January 1607, there were “great floods;” in March it was unseasonably hot; the summer was extremely hot and dry, and many died because of it. But then came December 1607, which many judged to be the coldest winter in memory.

Fruit orchards that would only go dormant in a normal winter split their trunks and died. It cost more to feed livestock than to sustain people on that grain. Birds froze in flight or fell from their roosts. In London, the River Thames froze solid.

According to Meriel Jeater of the Museum of London, the Thames froze 23 times between 1309 and 1814, and then never again. “The Old London Bridge at the time … had 19 arches, and each of the 20 piers was supported by large breakwaters. When chunks of ice got caught between them, it slowed the flow of the river above the bridge, making it more likely to freeze over. … When New London Bridge opened in 1831 it only had five arches. The Thames never froze over in the London area again.” http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2524252/How-Londoners-celebrated-River-Thames-freezing-frost-fairs-ice.html#ixzz4r7J3ptFu Perhaps to profit from the phenomenon of a once-in-a-lifetime cold spell, an anonymous author wrote a 28-page book, The Great Frost: Cold doings in London, except it be at the Lottery, With newes out of the country. A familiar talke betwene a country-man and a citizen touching this terrible frost and the great lotterie, and the effects of them. the description of the Thames frozen over, which may have a longer title than the interior text. The cover says it was printed on London Bridge (then supporting shops and tenements above the shops), so undoubtedly the book was meant to be sold on the frozen river below. There were two characters, the Countryman and the Citizen, having a dialogue about the first Frost Fair ever held, and the economic conditions of England because of the extended freeze.

In the city, the Frost Fair meant that shops could set up market tents on the frozen river that “shows like grey marble roughly hewn” and sell souvenirs and winter clothing and shoes, serve alcohol from bars on wheels, gamble on sports or animal baiting, provide hot fair food from fires built on the ice (I wonder if they deep fried odd things as we do now), and have sleigh rides up and down the river. Ice skating was well-known in the Netherlands and Germany, and perhaps the English tried it. They also played football, and shot arrows and muskets. The Citizen said: “Both men, women, and children walked over, and up and downe in such companies, that I verily believe, and I dare almost sweare it, that one half (if not three parts) of the people in the Citie, have been seene going on the Thames.”

And right there in London, probably out on the ice on a Saturday, we’d find the Marbury family, listening to musicians and watching dancers, playing, and eating fair food like turkey leg, meat or fruit pies, and gingerbread.

But at home, they were bundled up against the cold, as much as they’d been out on the Thames. The river was the main artery for shipping food, trade goods, and fuel like coal and wood into the city, and the ships were stuck out at sea, or frozen in ports. Wagons were similarly prevented from moving goods on frozen roads. The Citizen in The Great Frost bemoans the “unconscionable and unmerciful raising of the prices of fuel.” A man golfing on ice, whose clothing style

A man golfing on ice, whose clothing style

puts him in this time frame. Some avid golfers

will tell you that their sport of chasing

a little ball is silly in the best of summer

weather—but this man is very determined

to improve his game.

With little or no firewood or coal, people shared beds, mixing up aunties and grandchildren, parents and babies, servants and any guest staying the night. They had cupboard beds or four-posters with a canopy and curtains to keep their body heat and warm breath captive. The large Marbury family would have shared beds and body heat at night.

The Countryman commended the city council for having stockpiled coal and wood against an emergency and price gouging.

“Their care for fire was as great as for food. Nay, to want it was a worse torment than to be without meat. The belly was now pinched to have the body warmed: and had not the provident Fathers of this city carefully, charitably and out of a good and godly zeal, dispersed a relief to the poor in several parts and places about the outer bounds of the City, where poverty most inhabiteth; by storing them beforehand with sea coal and other firing at a reasonable rate, I verily persuade myself that the unconscionable and unmerciful raising of the prices of fuel by chandlers, woodmongers, &c.—who now meant to lay the poor on the rack—would have been the death of many a wretched creature through want of succour.”

The Citizen responded: “Strangers may guess at our harms: yet none can give the full number of them but we that are the inhabitants. For the City by this means [the closure of the river and roads] is cut off from all commerce.”

With commercial traffic stopped in its tracks during the Great Frost, the merchants, warehouses, dock hands, ship crews, and others were forced into stoppages they called “The dead vacation,” “The frozen vacation,” and “The cold vacation.” We can imagine the effect on their economy, especially if they were living hand to mouth.

Coupled with the loss of work and little to sell in the shops, the price of food rose precipitously. “For you of the country being not able to travel to the City with victuals, the price of victail must of necessity be enhanced; and victail itself brought into a scarcity,” wrote the Citizen.

The church poor rolls, the parish charity for widows and orphans, would have been stretched past their limits when they experienced weather and epidemiological catastrophes, so of course the Marburys would have been no stranger to hard work, short rations, and sharing small spaces.

The Great Frost was harsh, and it wasn’t the only time the Thames froze, but it was the most memorable. It lasted a little more than fourth months until the ice broke up and life returned to normal. Well, normal for them. Warmer meant… Plague.

In the forthcoming Hutchinson book, there's a very long bibliography. This article, actually a chapter of the Hutchinson book, is about an event that took place when Anne Marbury (not yet Hutchinson) was a teenager living with her family in London. Her father was a popular minister and had authority over several churches at the time.

I will probably remove this chapter from the blog, or severely edit it when the book is published, but as with the other books, I wanted to give you a taste of the book and an opportunity for input (in the comments).

In the meantime, it's really, really hot, and I hope this article will help you forget for a few minutes. Cheers!

PS: This is the sixth anniversary of the Dyer blog. Thank you for visiting and clicking the articles and links. At the moment, the page views are 471,634. Half a million is only a few days away!

The Great Frost © 2017 by Christy K Robinson

T he Great Frost of 1608 began in December 1607, when a massive freeze descended on Great Britain, Iceland, and Europe. It enveloped city and country alike, freezing animals and people, stopping trading ships, sending icebergs on the North Sea between England and the Continent, and freezing seaports so that coastal shipping trade came to a stop for three months.

“The first decade of the 17th century was marked by a rapid cooling of the Northern Hemisphere, with some indications for global coverage. A burst of volcanism and the occurrence of El Niño seem to have contributed to the severity of the events. … Additional paleoclimatic, global evidence testifies for an equatorward shift of global wind patterns as the world experienced an interval of rapid, intense, and widespread cooling.” Schimmelrnann, Lange, Zhao, and Harvey, abstract, http://aquaticcommons.org/14822/1/Arndt%20Schimmelmann.pdf The Peruvian silica volcano, Huaynaputina, erupted in 1600, with so much ejecta that more than 12 cubic miles of rock and ash filled the atmosphere, causing rapid global cooling and catastrophic weather events for a decade, including a Russian famine that killed two million people, epic mud flows in California, great droughts and freezes that affected the Popham and Jamestown colonies in Virginia, and die-offs in European vineyards. The far-off Peruvian volcano affected Great Britain, too.

A succession of hot, dry summers and extra-cold winters in England heralded the coldest years of the Little Ice Age in the seventeenth century. No one knew it then, of course. They just knuckled down and got on with survival.

In January 1607, there were “great floods;” in March it was unseasonably hot; the summer was extremely hot and dry, and many died because of it. But then came December 1607, which many judged to be the coldest winter in memory.

Fruit orchards that would only go dormant in a normal winter split their trunks and died. It cost more to feed livestock than to sustain people on that grain. Birds froze in flight or fell from their roosts. In London, the River Thames froze solid.

According to Meriel Jeater of the Museum of London, the Thames froze 23 times between 1309 and 1814, and then never again. “The Old London Bridge at the time … had 19 arches, and each of the 20 piers was supported by large breakwaters. When chunks of ice got caught between them, it slowed the flow of the river above the bridge, making it more likely to freeze over. … When New London Bridge opened in 1831 it only had five arches. The Thames never froze over in the London area again.” http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2524252/How-Londoners-celebrated-River-Thames-freezing-frost-fairs-ice.html#ixzz4r7J3ptFu Perhaps to profit from the phenomenon of a once-in-a-lifetime cold spell, an anonymous author wrote a 28-page book, The Great Frost: Cold doings in London, except it be at the Lottery, With newes out of the country. A familiar talke betwene a country-man and a citizen touching this terrible frost and the great lotterie, and the effects of them. the description of the Thames frozen over, which may have a longer title than the interior text. The cover says it was printed on London Bridge (then supporting shops and tenements above the shops), so undoubtedly the book was meant to be sold on the frozen river below. There were two characters, the Countryman and the Citizen, having a dialogue about the first Frost Fair ever held, and the economic conditions of England because of the extended freeze.

In the city, the Frost Fair meant that shops could set up market tents on the frozen river that “shows like grey marble roughly hewn” and sell souvenirs and winter clothing and shoes, serve alcohol from bars on wheels, gamble on sports or animal baiting, provide hot fair food from fires built on the ice (I wonder if they deep fried odd things as we do now), and have sleigh rides up and down the river. Ice skating was well-known in the Netherlands and Germany, and perhaps the English tried it. They also played football, and shot arrows and muskets. The Citizen said: “Both men, women, and children walked over, and up and downe in such companies, that I verily believe, and I dare almost sweare it, that one half (if not three parts) of the people in the Citie, have been seene going on the Thames.”

And right there in London, probably out on the ice on a Saturday, we’d find the Marbury family, listening to musicians and watching dancers, playing, and eating fair food like turkey leg, meat or fruit pies, and gingerbread.

But at home, they were bundled up against the cold, as much as they’d been out on the Thames. The river was the main artery for shipping food, trade goods, and fuel like coal and wood into the city, and the ships were stuck out at sea, or frozen in ports. Wagons were similarly prevented from moving goods on frozen roads. The Citizen in The Great Frost bemoans the “unconscionable and unmerciful raising of the prices of fuel.”

A man golfing on ice, whose clothing style

A man golfing on ice, whose clothing styleputs him in this time frame. Some avid golfers

will tell you that their sport of chasing

a little ball is silly in the best of summer

weather—but this man is very determined

to improve his game.

With little or no firewood or coal, people shared beds, mixing up aunties and grandchildren, parents and babies, servants and any guest staying the night. They had cupboard beds or four-posters with a canopy and curtains to keep their body heat and warm breath captive. The large Marbury family would have shared beds and body heat at night.

The Countryman commended the city council for having stockpiled coal and wood against an emergency and price gouging.

“Their care for fire was as great as for food. Nay, to want it was a worse torment than to be without meat. The belly was now pinched to have the body warmed: and had not the provident Fathers of this city carefully, charitably and out of a good and godly zeal, dispersed a relief to the poor in several parts and places about the outer bounds of the City, where poverty most inhabiteth; by storing them beforehand with sea coal and other firing at a reasonable rate, I verily persuade myself that the unconscionable and unmerciful raising of the prices of fuel by chandlers, woodmongers, &c.—who now meant to lay the poor on the rack—would have been the death of many a wretched creature through want of succour.”

The Citizen responded: “Strangers may guess at our harms: yet none can give the full number of them but we that are the inhabitants. For the City by this means [the closure of the river and roads] is cut off from all commerce.”

With commercial traffic stopped in its tracks during the Great Frost, the merchants, warehouses, dock hands, ship crews, and others were forced into stoppages they called “The dead vacation,” “The frozen vacation,” and “The cold vacation.” We can imagine the effect on their economy, especially if they were living hand to mouth.

Coupled with the loss of work and little to sell in the shops, the price of food rose precipitously. “For you of the country being not able to travel to the City with victuals, the price of victail must of necessity be enhanced; and victail itself brought into a scarcity,” wrote the Citizen.

The church poor rolls, the parish charity for widows and orphans, would have been stretched past their limits when they experienced weather and epidemiological catastrophes, so of course the Marburys would have been no stranger to hard work, short rations, and sharing small spaces.

The Great Frost was harsh, and it wasn’t the only time the Thames froze, but it was the most memorable. It lasted a little more than fourth months until the ice broke up and life returned to normal. Well, normal for them. Warmer meant… Plague.

Published on August 31, 2017 23:22

July 22, 2017

The new church and the pastor's battle with a chicken

Enjoy this guest post, a slice of life in 1682 New England.

© 2017 Ken Horn

Those old, stern Puritans. I love to study them. And because they are my ancestors, and some of my forebears experienced persecution at the hands of their ministers and leaders, I love to criticize them. But Puritan clergy were not always the staid, stern destroyers of all that might be enjoyable.

Old Tunnel Meeting House, Lynn, Mass., 1682.

Old Tunnel Meeting House, Lynn, Mass., 1682.

Notice the signature of "Jeremiah Shepard," the hero of

this story.

Photo: Digital Commonwealth, Massachusetts Collections OnlineI came across a delightful account of a feast given at the dedication of the Old Tunnel Meeting-House in Lynn, Mass., in 1682:

"Ye Deddication Dinner was had in ye greate barne of Mr. Hoode which by reason of its goodly size…. Ye kine [cattle] that were wont to be there were forced to keep holiday in the field."

Kine "forced to keep holiday in the field." Better than

Kine "forced to keep holiday in the field." Better than

being on the menu!

Photo: Colonial Williamsburg Though the cows were out and the place had been swept and cleaned, it appears that “the fowls persisted in flying in and roosting over the table, scattering feathers and hay on the parsons beneath.” The writer was apparently too delicate to mention what else they might be scattering on the parsons and the table beneath.

The sitcom begins when a Reverend Mr. Shepard runs afoul of a fowl: The fowl might have been upset at the loss of a family

The fowl might have been upset at the loss of a family

member or two, for purposes of the meal.

The banquet ended with some "mawdlin songs and much roistering laughter."

The account ends: "So noble and savoury a banquet was never before spread in this noble town, God be praised."

Indeed. One wonders how long it took for townfolk to pass by the unfortunate Rev. Mr. Shepard without snickering. And this would surely come to mind every time the poor parson preached.

******

Rev. Jeremiah Shepard, 1648-1720, was the son of Thomas Sheperd, one of three inquisitors of Anne Marbury Hutchinson while she was incarcerated in Joseph Weld's home in Roxbury during the harsh winter of 1637-38.

For more on Rev. Jeremiah Shepard, who was a strange bird himself, see Wikipedia.

Also see the 1905 book, Life of Rev. Jeremiah Shepard: Third Minister of Lynn, 1680-1720, by John Joseph Mangan. Rev. Shepard was accused of wizardry in the Salem witch trials and narrowly escaped trial and imprisonment.

******

Dr. Ken Horn is a minister and author, a history-loving descendant of Anne and William Hutchinson and William and Mary Dyer, and lives in Springfield, Missouri.

© 2017 Ken Horn

Those old, stern Puritans. I love to study them. And because they are my ancestors, and some of my forebears experienced persecution at the hands of their ministers and leaders, I love to criticize them. But Puritan clergy were not always the staid, stern destroyers of all that might be enjoyable.

Old Tunnel Meeting House, Lynn, Mass., 1682.

Old Tunnel Meeting House, Lynn, Mass., 1682.Notice the signature of "Jeremiah Shepard," the hero of

this story.

Photo: Digital Commonwealth, Massachusetts Collections OnlineI came across a delightful account of a feast given at the dedication of the Old Tunnel Meeting-House in Lynn, Mass., in 1682:

"Ye Deddication Dinner was had in ye greate barne of Mr. Hoode which by reason of its goodly size…. Ye kine [cattle] that were wont to be there were forced to keep holiday in the field."

Kine "forced to keep holiday in the field." Better than

Kine "forced to keep holiday in the field." Better than being on the menu!

Photo: Colonial Williamsburg Though the cows were out and the place had been swept and cleaned, it appears that “the fowls persisted in flying in and roosting over the table, scattering feathers and hay on the parsons beneath.” The writer was apparently too delicate to mention what else they might be scattering on the parsons and the table beneath.

The sitcom begins when a Reverend Mr. Shepard runs afoul of a fowl:

The fowl might have been upset at the loss of a family

The fowl might have been upset at the loss of a family member or two, for purposes of the meal.

"Mr. Shepard's face did turn very red and he catched up an apple and hurled it at ye birds. But he thereby made a bad matter worse for ye fruit being well aimed it hit ye legs of a fowl and brought him floundering and flopping down on ye table, scattering gravy, sauce and divers things upon our garments and in our faces. But this did not well please some, yet with most it was a happening that made great merryment.”

The banquet ended with some "mawdlin songs and much roistering laughter."

The account ends: "So noble and savoury a banquet was never before spread in this noble town, God be praised."

Indeed. One wonders how long it took for townfolk to pass by the unfortunate Rev. Mr. Shepard without snickering. And this would surely come to mind every time the poor parson preached.

******

Rev. Jeremiah Shepard, 1648-1720, was the son of Thomas Sheperd, one of three inquisitors of Anne Marbury Hutchinson while she was incarcerated in Joseph Weld's home in Roxbury during the harsh winter of 1637-38.

For more on Rev. Jeremiah Shepard, who was a strange bird himself, see Wikipedia.

Also see the 1905 book, Life of Rev. Jeremiah Shepard: Third Minister of Lynn, 1680-1720, by John Joseph Mangan. Rev. Shepard was accused of wizardry in the Salem witch trials and narrowly escaped trial and imprisonment.

******

Dr. Ken Horn is a minister and author, a history-loving descendant of Anne and William Hutchinson and William and Mary Dyer, and lives in Springfield, Missouri.

Published on July 22, 2017 18:17

July 18, 2017

Holden, Gorton, Greene, and the Rolling Stones

© 2017 Christy K Robinson

This article is adapted from a chapter in my book manuscript on Anne Marbury Hutchinson.

R andall Holden was one of the Rhode Island men abducted in 1643 by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He wrote a long, angry letter to the General Court from his prison cell in Salem.

Holden, 41, Samuel Gorton, 51, and John Green, 49, and other men had been supporters of Anne Hutchinson, and shortly after founding Pocasset/Portsmouth, had moved to lands they purchased in January 1643 from the sachem Miantonomo at Shawomet, now called Warwick, Rhode Island. It was land falsely claimed by Massachusetts Bay Colony, based upon a fraudulent charter that Rev. Thomas Weld, an agent and envoy of the Bay, was sending around to important government figures for their signatures, as if they’d approved it in Parliament.

In the letter, Holden called Gov. Winthrop and the Court the “Idol General” and “Judas Iscariot’s fellow confessor for hire,” and he’d heard that Winthrop had said that either the Rhode Islanders (Holden, Gorton, and Greene, Robert Potter and Richard Waterman) would be subjected to him or removed to Boston, “though it should cost blood.”

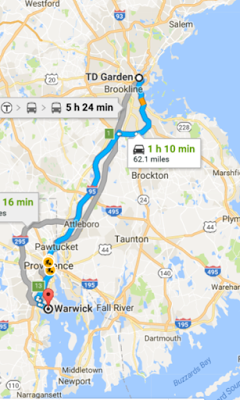

Warwick to Boston via I-95.

Warwick to Boston via I-95. Google MapsThey’d been summoned to Boston and given words of safe conduct, but when they’d ignored the summons, they’d been violently abducted by a 40-man force, beaten, and imprisoned in several Massachusetts Bay towns, with iron fetters on their legs to prevent escape. They were not charged or tried on their possession of the disputed land, but on new charges of sedition and heretical religious beliefs—the same charges Anne Hutchinson had faced six years before. Their conviction was a foregone conclusion, and they were put to hard labor on nearby farms, still shackled. But they were saved from execution by only two votes of the General Court. Gorton, a fiery-tempered man in those years (though he later mellowed and was a credit to Rhode Island), was warned that if he should speak or write of his blasphemous and abominable heresies, he’d be condemned to death and executed. Holden, Greene, and the others were similarly threatened with death if they spoke to anyone but an officer of state or church. They were “silenced.” After a winter at hard labor, they were banished upon pain of death, both from Massachusetts Bay and from their homes at Shawomet.

Randall Holden’s letter had a long passage that accused the MassBay government of knowing Anne Hutchinson’s move to Pelham, where she and much of her family were massacred, had been preventable, but they said nothing, making them complicit in the deaths.

Holden, Greene, and Gorton went to England in 1644 to resolve their grievance and get a charter from the Earl of Warwick, a Puritan who was an overseer of colonies in the western hemisphere. The three Shawomet men had to sail from New Amsterdam (New York City) because of the animosity of Boston’s authorities. They were successful in their quest, but the King was executed in 1649, which meant that Rhode Island needed a new charter in 1650-51, when William Dyer was the colony’s attorney general.

* * * * *

Jagger and Richards on the American

Jagger and Richards on the American Tour in 1972.

Wikipedia So what brought this story to mind? I learned from a post by New England Historical Society that on July 18, 1972, Rolling Stones musicians Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were in jail in Warwick, Rhode Island (formerly Shawomet, remember), for messing with drugs and scuffling with a photographer. (I know this drug connection comes as a shock to you, right?)

But over in Boston, 15,000 Rolling Stones fans were short on “Satisfaction,” and eager to rock out at a Stones concert at the Boston Garden. The Boston mayor, Kevin White, was concerned that a riot would break out if the Stones didn’t roll in. This was a distinct possibility, considering previous violence at concerts around America that summer. He persuaded Rhode Island police to release the criminals into his custody, and Massachusetts police, using lights and sirens, rushed the rockers up I-95 to Boston, where opening act Stevie Wonder had played the longest warm-up set of his career. At 1:00 a.m., the Stones arrived at the venue and performed their concert, while the mayor arranged with the transit authority to keep running so concert-goers could get home.

For comments from people who attended the concert, see this Facebook link: https://www.facebook.com/NewEnglandHistoricalSociety/photos/a.150432615140239.1073741826.149729011877266/722370191279809/?type=3&theater

Massachusetts State Police car, 1972

Massachusetts State Police car, 1972The parallels between 1643 and 1972 are not very close, but it’s fun to compare the Warwick-Boston relationship! This is why we enjoy history, right?

* * * * *

Christy K Robinson is the author of this Dyer website and three five-star-reviewedbooks on the Dyers, available by clicking these links.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2017)

Published on July 18, 2017 19:22

June 1, 2017

#OnThisDay, a page from the city of Boston

original page location:

https://www.boston.gov/news/notes-archives-mary-dyer-executed-onthisday-1660

Notes from the Archives: Mary Dyer executed #onthisday in 1660 Published by: City of Boston Archives and Records ManagementOn this day in 1660, Mary Dyer was executed on the Boston Common for defying her banishment from Boston. Mary’s execution is one story in a larger narrative of frequent religious clashes in Boston's early days. Her death is often linked to the easing of anti-Quaker laws in Boston. Mary Dyer was born in England and emigrated to Boston with her husband in about 1635. The Dyers, like many others emigrating to Boston, were fleeing religious persecution in England. Shortly after arriving in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Dyers joined the church in Boston. Less than a year later, the Dyers became embroiled in a theological controversy called antinomianism. This controversy engulfed the Boston church between 1636 and 1638 and tore it apart. Boston's leaders took dissenting community members to trial for their beliefs. But, dissenters typically refused to change their convictions.

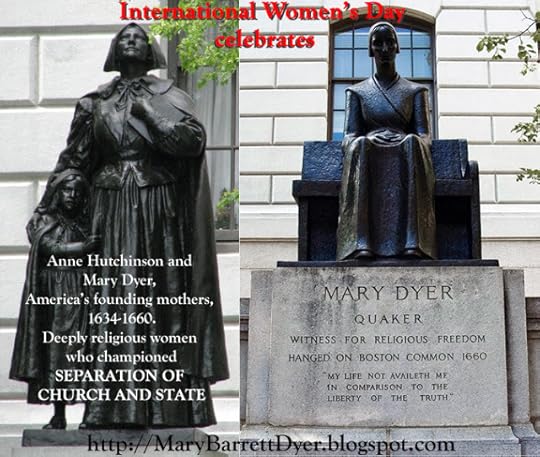

Quaker sculptor Sylvia Shaw Judson created the bronze

Quaker sculptor Sylvia Shaw Judson created the bronze

statue of Mary Dyer. The statue stands in front

of the Massachusetts State House,

and was photographed by Peter Dyer in 1976.

In the midst of the controversy, Mary gave birth to a severely deformed stillborn child. Common cultural beliefs of the time held that physical deformities indicated spiritual unfitness. Boston's church leaders exhumed her child's grave. They declared the child's deformities both a sign and result of Mary's deformed religious beliefs. Shortly after the exhumation, the Dyers left Boston for Rhode Island with other antinomians. These included Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright.

In the early 1650s, Mary Dyer returned to England where she was introduced to the Society of Friends. They were widely known as the Quakers. She became a devoted Quaker, committed to spreading her new found spirituality. Boston’s Puritan establishment did not tolerate Quaker proselytism. When Dyer returned to Boston in 1657, she was immediately imprisoned. Dyer was then banished for both her Quaker beliefs and her attempts to spread her beliefs to others.

Dyer defied the banishment order. She returned to Boston with the intention of spreading her religion. She was again banished, and threatened with execution if she returned. Dyer broke the banishment order a third time. She traveled to Boston in October of 1659 where she was immediately sentenced to death. However, on the date of her execution, she was pulled from the gallows and given a reprieve. She left Boston, but returned again in the spring of 1660. She was again sentenced to execution, and this time, did not receive a reprieve.

On the day of her execution, Mary was given a chance to recant her beliefs and escape execution. She stated, “Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death.”

****************************

Continue Mary Dyer's legacy. See: http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2017/05/celebrate-your-connection-to-mary-dyers.html

https://www.boston.gov/news/notes-archives-mary-dyer-executed-onthisday-1660

Notes from the Archives: Mary Dyer executed #onthisday in 1660 Published by: City of Boston Archives and Records ManagementOn this day in 1660, Mary Dyer was executed on the Boston Common for defying her banishment from Boston. Mary’s execution is one story in a larger narrative of frequent religious clashes in Boston's early days. Her death is often linked to the easing of anti-Quaker laws in Boston. Mary Dyer was born in England and emigrated to Boston with her husband in about 1635. The Dyers, like many others emigrating to Boston, were fleeing religious persecution in England. Shortly after arriving in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Dyers joined the church in Boston. Less than a year later, the Dyers became embroiled in a theological controversy called antinomianism. This controversy engulfed the Boston church between 1636 and 1638 and tore it apart. Boston's leaders took dissenting community members to trial for their beliefs. But, dissenters typically refused to change their convictions.

Quaker sculptor Sylvia Shaw Judson created the bronze

Quaker sculptor Sylvia Shaw Judson created the bronze statue of Mary Dyer. The statue stands in front

of the Massachusetts State House,

and was photographed by Peter Dyer in 1976.

In the midst of the controversy, Mary gave birth to a severely deformed stillborn child. Common cultural beliefs of the time held that physical deformities indicated spiritual unfitness. Boston's church leaders exhumed her child's grave. They declared the child's deformities both a sign and result of Mary's deformed religious beliefs. Shortly after the exhumation, the Dyers left Boston for Rhode Island with other antinomians. These included Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright.

In the early 1650s, Mary Dyer returned to England where she was introduced to the Society of Friends. They were widely known as the Quakers. She became a devoted Quaker, committed to spreading her new found spirituality. Boston’s Puritan establishment did not tolerate Quaker proselytism. When Dyer returned to Boston in 1657, she was immediately imprisoned. Dyer was then banished for both her Quaker beliefs and her attempts to spread her beliefs to others.

Dyer defied the banishment order. She returned to Boston with the intention of spreading her religion. She was again banished, and threatened with execution if she returned. Dyer broke the banishment order a third time. She traveled to Boston in October of 1659 where she was immediately sentenced to death. However, on the date of her execution, she was pulled from the gallows and given a reprieve. She left Boston, but returned again in the spring of 1660. She was again sentenced to execution, and this time, did not receive a reprieve.

On the day of her execution, Mary was given a chance to recant her beliefs and escape execution. She stated, “Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death.”

****************************

Continue Mary Dyer's legacy. See: http://marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/2017/05/celebrate-your-connection-to-mary-dyers.html

Published on June 01, 2017 13:12

May 30, 2017

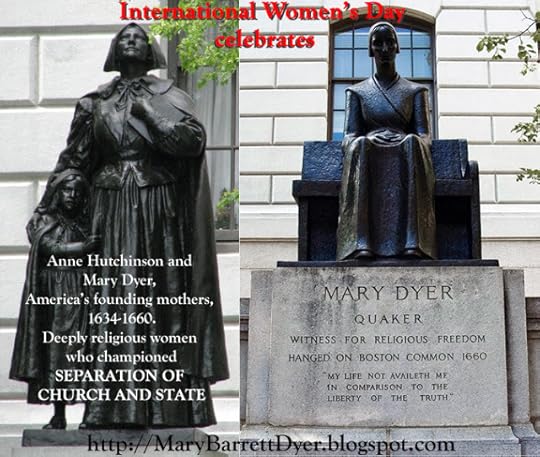

Celebrate your connection to Mary Dyer's cause: religious liberty

Honor Mary Dyer’s sacrifice,

or your connection to her,

by giving in her name!Gifts to Americans United for Separation of Church and State

are tax-deductible.

Click the link to go to their secure page.

© 2017 Christy K Robinson

No one knows Mary Dyer's date or even year of birth. Because of when she married, her husband's birth in 1609, and various life events, genealogists and historians have assumed that it was between 1609 and 1611.

But we do know her date of death: June 1, 1660. That's when, after she deliberately violated her banishment-upon-pain-of-death if she returned to Massachusetts, Mary Dyer was executed by hanging.

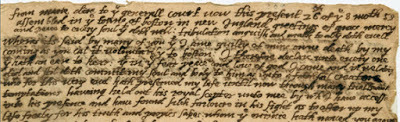

The opening sentences of Mary Dyer's handwritten letter to

The opening sentences of Mary Dyer's handwritten letter to the Massachusetts General Court.

marybarrettdyer.blogspot.com/p/mary-dyer-1659-letter.htmlMary (and many other Rhode Islanders) had been cast out of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth and New Haven Colonies, when the zealous fundamentalists clashed with people who were coming to terms with other religious concepts and practices. Religion wasn't just an hour of church once a week--it was your short time on earth preparing your soul for eternity in heaven or hell. The fundamentalists (aka the Puritans) outlawed Antinomians, Baptists, Catholics, Quakers, and other groups as they cropped up. They had strained relations with Anglicans because they considered it their duty before God to purify the Church of England of its remnants of Catholicism (therefore the Anglican pejorative name of "Puritan.") And that same hard-line zeal extended to purifying their communities of people (mostly women) they suspected of being witches.

The people who emigrated to MassBay Colony were ultra-conservative zealots, far more fundamental in nature than the English Puritans they left behind: Endecott, Shelton, Winthrop, Dudley, Weld, Shepherd, Cotton, Wilson, and many others in power. Their parishioners followed, and they attempted to build a Puritan utopia--which of course was impossible, because of the oppression they created as a theocracy.

God has mercy and boundless grace. Theocrats do not.

New England's government was inextricably combined with religion. From the moment they conceived of a new colony in the wilderness of New England, it was going to be a utopia where they lived by the precepts of the Bible's Old Testament law. The voters, called freemen, were members of churches that were very difficult to get membership. The magistrates and governor assistants were often ministers and teachers in the churches. If a tradesman turned in an invoice that seemed to ask too much money, it could be both a religious and civil offense. If a couple had an affair, the offenders could be hanged. Fornication (sex before marriage) could be punished by hanging, flogging, and time in stocks. Observing May Day or Christmas originated in pagan or Catholic tradition, and could be punished by fines, confiscation of goods, and flogging. Having a sharp tongue got Gov. Bellingham's sister hanged.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony banned Catholic priests in 1647 because they were afraid of French-Canadian and Indian converts warring against them, and a Jesuit takeover of the already-theocratic government. The same issues that New England faced in 1647 face America today. That's 370 years. Don't let your guard down, friends. Be vigilant about preserving religious liberty for ALL.

The religious utopia the founders envisioned never existed--it couldn't, flawed people being flawed people. This is how it's always been, for millennia, in all civilizations.

When Anne Marbury Hutchinson was tried for sedition and heresy in 1637 and 1638, her judges were the ministers of the colony. Her crimes: holding Bible studies in her home that included men and women, speaking against the (male) ministers by saying that all but her brother-in-law Rev. Wheelwright, and her friend of two decades, Rev. John Cotton, preached a ministry of salvation, instead of a covenant of grace. She broke the fifth commandment to "honor her father and mother," by disobeying the men in authority over her. Even after she was exiled and moved to Rhode Island, she was hounded and threatened, until at last she moved to the Bronx and was killed by Native Americans who had been incited by the Dutch colonists, who also had a religious government.

So you see, religion plus government equaled fear, judgment, and punishment. Religious fundamentalists can't keep themselves self-disciplined or their own relatives under their thumbs, much less a community or society. They can't create a New Jerusalem or a paradise on earth.

Rhode Island, while William Dyer was a government official (Recorder, Secretary of State, Attorney General, and Solicitor General), began under Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson--both of them what we'd consider to be deeply religious people--and it was a secular government that encoded religious liberty, or "liberty of conscience," as they called it. They'd had enough of persecution back in England, then in Massachusetts, in the name of God. They wrote their separation of powers into their first documents, acknowledging God, but keeping religion separate from what Hutchinson called the "magistracy." And they wrote their liberty into charters (like a constitution) that were ratified by successive English governments, even in a time of civil war back in England. The charter of 1663, written by Dr. John Clarke, Rev. Roger Williams, and (I believe because of some of the stipulations) Attorney General William Dyer, became one of the templates for the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The first Quaker missionaries to America arrived in 1656 and immediately clashed with the authorities. Mary Dyer returned from her nearly five years in England in early 1657 and was imprisoned right off the ship for being a Quaker. (She was quite aware of the potential for arrest, and she could have sailed for another port, but she went to Boston anyway.) She was rescued and imprisoned several more times before 1660. Mary witnessed and heard about Baptists and Quaker Friends who had been beaten nearly to death (certainly to a disability), imprisoned without blankets or warmth in New England's severe winters, had property confiscated, had ears sliced off, had two teens condemned to slavery, and other bloody torments. Finally, as she stood ready to die, two male Friends were hanged and she was reprieved. She believed as they did that God had called her to die in order to shock the New England people into forcing governors to stop the torture and death. It didn't work for the two English Quakers, but Mary Dyer, a woman with a high social status, known to be intelligent and beautiful, was the notorious shock needed. Her impassioned letter to the General Court (see tab above this article) was edited into an appeal to King Charles II, who ordered a halt. Shortly after that order, he granted the Rhode Island charter that had been written by Clarke, Williams, and Dyer, which granted and guaranteed freedom of conscience to worship without interference or support of the government. The document is the first of its kind in the world.

But despite the charter and others like it made in later years, and despite the US Constitution and other laws, religious liberty is under attack. I'm not talking about a War on Christmas or the right to refuse to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding. But there are numerous attacks on religious liberty for all: a narrow slice of fundamentalists (Christian, Muslim, it makes no difference) tries to legislate or force their beliefs and behaviors on the rest of society via bedroom and bathroom laws, women's health, refusal of voting rights or permits to certain groups, Christian-only prayer in government functions or public schools, vouchers for taxpayer-funded religious education--the list is endless. It's growing every day, but it hasn't helped the morals of Americans, so it's obviously not working.

The only way to change America for the better is to teach kindness, mercy, compassion, and justice from home, from your own behavior.

We don't know her birthday, but we do know the day she inherited eternal life. In honor of Mary Dyer's ultimate sacrifice in the cause of religious liberty and separation of church and state on June 1, 1660, I invite you to memorialize her and make a gift in Mary Dyer's name to the nonprofit organization Americans United for Separation of Church and State (AU). <--Click the link for their secure page.

AU, whose vision and mission are below the image, was founded in 1947.

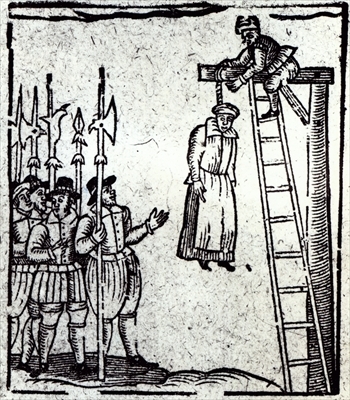

This woodcut does not depict Mary Dyer, but the pikemen and the gallows give you an idea of how it was done.

This woodcut does not depict Mary Dyer, but the pikemen and the gallows give you an idea of how it was done.In Mary's case, the pikemen and musketeers who escorted her from the prison to the gallows, about a mile,

weren't there to keep her from escaping. They were there to protect the magistrates and officials from the

angry, unruly crowd that may have numbered more than 3,000 people.

MISSION

Americans United for Separation of Church and State is a nonpartisan educational and advocacy organization dedicated to advancing the constitutional principle of church-state separation as the only way to ensure freedom of religion, including the right to believe or not believe, for all Americans.

VISION

We envision an America where everyone can freely choose a faith and support it voluntarily, or follow no religious or spiritual path at all, and where the government does not promote religion over non-religion or favor one faith over another.AU Facebook page

Americans United home page

************************************

Christy K Robinson is the author of the books:

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated Vol. 1 (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This Vol. 2 (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Anne Hutchinson, American Founding Mother (2017)

Published on May 30, 2017 16:15

March 28, 2017

Life sketch of Charles Dyer, 1650-1709

© 2017 Christy K Robinson

Charles Dyer was the last child of Mary and William Dyer. He was born the year after King Charles I was beheaded, at the time when the young Charles II was fighting Cromwell’s forces before he fled to exile in France. To name the Dyer baby after the Anglican (with Catholic leanings) king was a rather bold statement in Puritan, republican-leaning New England!

King Charles I of England

King Charles I of England1650: Charles Dyer born in Newport, Rhode Island, the last of Mary Dyer’s six living children. His parents were co-founders of Portsmouth in 1638 and Newport in 1639.

1652: He was about one and a half or two years old when both parents went to England. William went as an agent of Rhode Island, and came home after a short time, with a political charter for the colony that replaced their former charter; but Mary Dyer stayed until 1657. Mary returned when Charles was about seven, so he probably didn’t recognize her. He may have been fostered with friends when his father had to leave town on business. (Read "Mary Dyer, the mother.")

The Dyer family probably attended the Baptist church of Rev. Obadiah Holmes, in Newport. There’s no record of Charles in the Friends/Quaker books, which is understandable, considering his mother’s actions as a Quaker. There’s probably no birth record like a Congregational (Puritan) or Anglican family might have, because Baptists didn’t baptize infants—they waited until the teen or adult years when the person reached an age of accountability.

Was Charles educated as well as his parents had been? Mary had been known for her conversational ability and we know she both read and wrote, which was not the usual attainment of most women of her time. William had probably been educated at a grammar school in Lincolnshire before his elite apprenticeship in London, and he had trained as a surveyor and attorney after he emigrated to New England. It was the custom of hundreds of years that boys were educated and/or apprenticed sometime around age 14, but we don’t know about the Dyer boys. But Charles was a farmer by age 18, so perhaps he learned on his father’s Newport farm.

1660: Mary Dyer, a Quaker, was hanged in Boston for religious liberty, having violated her banishment orders and been imprisoned several times between 1657 and 1660.

1661: William Dyer Sr. married a woman named Katherine and they had one daughter, Elizabeth, by 1661-1662. In her twenties, Elizabeth Dyer married John Greenman, they had several children, and she died in 1755. Though Katherine sued her husband’s children after his death (and lost each of her cases), Charles named his only daughter after his half-sister Elizabeth.

Little Compton, Rhode IslandPhoto by LandVest

Little Compton, Rhode IslandPhoto by LandVest

1668: Charles married very young, perhaps at age 17-18, for his first child, James, was born in May 1669 in Little Compton, Rhode Island . The village is located across the Sakonnet water to the east of Newport, on the mainland. Even today, it’s a rural setting with green farms and a rocky Atlantic coastline.

For many years, Charles' first wife has been assumed to be Mary Lippett, and there was a family of Lippetts in Rhode Island, but Mary is not confirmed to be one of them. Did the teenage Charles and Mary fornicate and get pregnant, and marry in haste? So how did a teenager come to be a husbandman (a farmer and stock breeder)? Was Charles given the land by his wealthy father, or was the land a dowry of his wife Mary (of whatever surname)? Little Compton is close to Newport as the crow flies (in a sailboat), but they could have farmed in Middletown, between Portsmouth and Newport, or across Narragansett Bay at Kingston. Or perhaps it was the perfect distance to start your family if it came less than nine months after the wedding.

Charles and Mary had children between 1669 and 1687, and Mary must have died between 1687 and 1689, perhaps in or shortly after childbirth.

Their children were:

1. James, b. 1669-d. abt 17352. William b. 1671, d. 1719 (executed for murdering his wife)3. Elizabeth, b. 1677, m. Tristram Hull 1699, d. 17194. Charles, b. 1685, d. 17265. Samuel, b. 1687, d. 1767. This man raised his brother William’s orphaned children after William was hanged for murdering his wife.1670: Death of brother Maher Dyer. Maher left a young wife, but no children.

1670: William Dyer Sr. deeds Newport lands to sons Samuel, Henry, and William, but not to youngest son Charles, who was already living in Little Compton with wife and child. Perhaps William Sr. had already provided land to Charles on his wedding.

1676-77: King Philip’s War raged between Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut colonists and Native American tribes. His oldest brother Samuel evacuated colonists from mainland Rhode Island across Narragansett Bay to Newport. His brother Henry Dyer supplied horses to the military. Charles, being about 26 years old, would have been very insecure at Little Compton, so he may have moved his family to better-defended Newport during the war. Also, his father’s health may have been failing at this time. Charles moving back to manage the Dyer farm would make sense, but we can’t know.

1677: Charles’ father, William Dyer Sr., dies in Newport at age 67. 1678: Death of eldest brother Samuel Dyer. 1679: Death of sister Mary Dyer Ward.1680: Half-sister Elizabeth Dyer receives her £40 inheritance from her father’s estate.1681: His stepmother Katherine Dyer sues Charles over "trespass" on her land. She loses. 1687: After lawsuits which she lost, Charles buys back Newport land and house from his stepmother Katherine.

Oct. 5, 1687: “Charles Dyre of Newport, Husbandman bought of [nephew] Samuel Dyre of Boston, carpenter, land in Newport RI. Bounded on the East, partly by certain lands in possession Mr. Francis Brinley & Lt . Collo of Peleg Sanford on the South, by land of Late Mr. Nicholas Easton and Mr. Johnson the West, by the sea on North by land of Henry Dyre.—with house, orchards, Gardens, meadows, woods - swamp--layed out unto mis Katharin Dyre [his stepmother] by town of Newport 1681 as her Right of Dower. 5 Oct1687. Witt[nesses]. Weat Clarke, Robert Little, Daniel Vernon. “

Source: Rhode Island Land Evidence 1648-1696 -Abstracts Vol 1 p. 206.

1687: Grants for land in Delaware secured for Charles and Henry, by older brother, Major William Dyre. Neither Charles nor Henry take possession of the land. [WAD] But it’s very possible that Charles’ oldest son James did, for James died in Bucks Co., Penn.

1687-88?: Death of Charles’ wife Mary. They’d been married for 20 years.

1688: Death of brother Maj. William Dyer in Delaware/Pennsylvania.

Mar. 8, 1690: Charles married Martha Brownell Wait. Martha was a childless widow who was seven years older than Charles. On the same day they married, Martha bought for £20, of her brother Robert Brownell, 30 acres in Little Compton, RI. Charles and Martha did not have children together, but Martha raised his younger children, and perhaps grandchildren. She died in 1744 at age 100.

From age 40 to his death at 59, I've seen no records of Charles and Martha. But it seems from his will that he owned land at Little Compton and Newport, and Martha owned land in Massachusetts, so they would have been very busy managing farms, or possibly leasing them to others.

1690: Death of brother Henry Dyer. Henry (and possibly his wife) had been buried on the Dyer Farm, but after 199 years, his headstone and remains were moved to the Farewell Cemetery in Newport.

1699: Daughter Elizabeth marries Tristram Hull, the grandson of the Quakers Robert and Deborah Harper of Sandwich, who Mary Dyer would have known. Elizabeth and Tristram had nine children, the first named Mary--perhaps after Mary Dyer the great-grandmother, or after Elizabeth's birth mother. Elizabeth and Tristram were Quakers.

1709: Charles dies, age 59, in Newport. He was buried with his brothers and parents on the Dyer family farm in Newport. He'd owned several farms, livestock, and equipment, and he had a respectable amount of money to leave to his children and widow. Will of Charles Dyer Sr.

Dated May 9, 1709; proved May 12, 1709 Newport.

Overseers: brothers George Brownell, Thomas Cornell & Benjamin Thayer.

Sons James, Samuel, William & Charles; daughter Elizabeth, now wife of Tristram Hull.

· To son James, all land and tenements in Little Compton, which he now liveth on, part of which I had with my wife Martha Dyer.

· To son Samuel, all my land and homestead that I now live on, with the old end of the dwelling house, barns, stables, &c., to be for him and his heirs unto the third generation, he paying legacies. To him also commonage in Newport and great bible.

· To son William, £100.

· To son Charles, £100.

· To daughter Elizabeth, the now wife of Tristram Hull, £30.

· My earnest will and desire is (that) piece of ground that is now called the Burying Ground, shall be continued for the same use unto all my after generations that shall see cause to make use of it, and I order that it shall be well kept fenced in by my son Samuel Dyre and his heirs forever.

· To wife Martha, the new end of Newport house for life, and then to son Samuel. To her also, all my household stuff, plate, cash, bills, bonds, six of best cows of her choice, twenty ewe sheep, best of flock, and two cows and six sheep to be kept for her winter and summer by Samuel, who is to take a reasonable care of her, as food, firing, &c. without any grudging or grumbling.

· To four sons James, William, Samuel and Charles, rest of stock.

· To son Samuel, carts, plows, &c.

· To overseers, £3 each. Source: Austin. https://books.google.com/books?id=LA7ntaS11ocC&pg=PA439&lpg=PA439&dq=Charles+Dyer,+1709+will&source=bl&ots=ZshqrzqpTc&sig=GNz6MDFHPUhWOdtT0ooUAt7uvXM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjWptvRo_jSAhUIwlQKHcn0BCgQ6AEIQzAJ#v=onepage&q=Charles%20Dyer%2C%201709&f=false

The Dyer Farm burying ground was on the coast of Narragansett Bay. Since the early 20th century, it's under what is now the Naval College hospital or clinic. William and Mary Dyer were buried there, as well as Charles and Henry. Probably Maher and Charles Dyer’s wife Martha, as well as other Dyer generations, were buried there. But the farm was broken into smaller and smaller parcels from the time of the Revolution. In 1889, workmen came across seven graves with headstones, and moved them to the Farewell Cemetery and Common (meaning the common grazing land) Burying Ground near the center of Newport. Among the seven were stones for Mary’s sons Henry (d. 1690) and Charles (d. 1709). Other graves, unmarked, probably remain there on the former Dyer property. If you're in Newport, you can drive on Cypress Street, right up to the fence, or you can visit it on Google Maps at this link. Then choose Street View.

Cypress Street fence. Approximate location of Dyer burying ground.

Cypress Street fence. Approximate location of Dyer burying ground.Photo by Christy K RobinsonCharles Dyer's headstone in Newport's Common Burying Ground

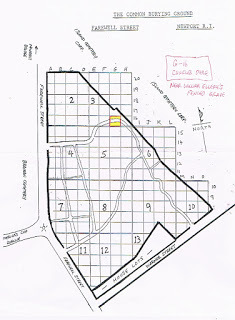

I met Bert Lippincott, Newport Historical Society librarian and genealogist, who marked a map of Common Burying Ground so I could visit the grave of Charles Dyer, 1650-1709. Charles may have been buried first on the Dyer home farm, where he lived after his father and brothers died. His remains were moved to the large cemetery later. (Alternatively, the officials took the headstones but not the skeletons.)

Common Burying Ground

Common Burying Groundclick to enlarge

Common Burying Ground, Newport, with inset of Charles Dyer's headstone.