Christy K. Robinson's Blog: William & Mary Barrett Dyer--17th century England & New England, page 8

August 17, 2016

The titans of early Boston

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

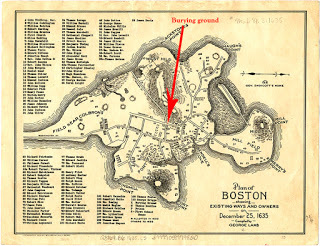

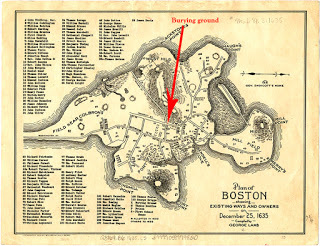

On my first day in Boston in years, I visited the graves of Gov. John Winthrop and his family, Rev. John Cotton, Rev. John Wilson, Rev. John Davenport, Isaac Johnson, and others who I learned to know very well as I researched and wrote my books on the Dyers.*

Click to enlarge the map

Click to enlarge the map

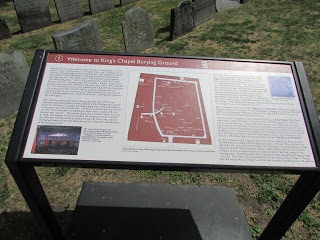

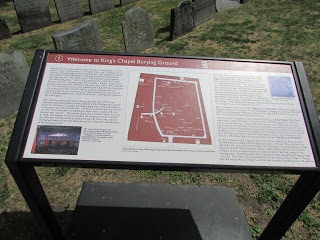

They were buried in what is now known as the King's Chapel Burying Ground. Boston was founded in 1630 to be a Puritan version of the New Jerusalem, where its people would be able to live good lives and prove their election (predestination) to eternal life. It was never the heavenly City Upon a Hill that they hoped it would be, but their rebellious spirit did create a beacon of culture, education, commerce, and patriotism that still shines brightly today.

In the 1680s, that rebellious nature, and their refusal to produce their royal charter from 1629 after repeated recalls by kings and Parliaments, came to (virtual) blows with the appointment of a royal governor, Sir Edmund Andros. During his short term, he declared there was no other land available in Boston (because the Calvinist Puritans wouldn't sell any for a Church of England meetinghouse), and an Anglican church must be built right there on the cemetery. So in 1686, the graves of Boston's founders were disturbed, moved, or otherwise covered by construction of what came to be known as King's Chapel. (Imagine how the fur would fly in Boston parlors!)

And so it was that the first founders of Boston, who had left the English church at great expense to their lives and estates, were disturbed by that very church not long after their deaths.

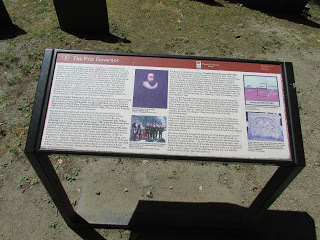

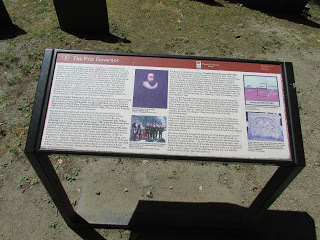

I walked down Beacon Street in the steamy heat to visit the graves of the men who I didn't necessarily like as I researched my books on Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson, but who I greatly respected for the commitment of their very lives and families and fortunes to the Christian utopia they hoped to build. These were never cartoon villains as I read their letters, journals, and testimony, but human beings who were well-respected and loved by many. They were leaders who inspired their followers. They were titans.

(Click photos to enlarge.)

Burial vault for Gov. John Winthrop's family. Once down

Burial vault for Gov. John Winthrop's family. Once down

the steps, the vault extends under the fence and sidewalk. I

couldn't detect any inscription on the tomb cover. Though his grave appears neglected, John Winthrop

Though his grave appears neglected, John Winthrop

is remembered at Boston First Church in the Back Bay

neighborhood of Boston, far from its original place near the harbor.

He was a founder of the church in 1630, but it is no longer

Puritan/Congregational. It's Unitarian Universalist.

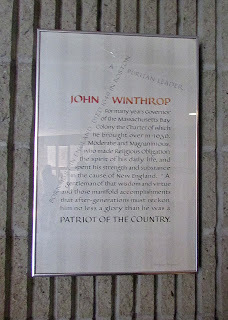

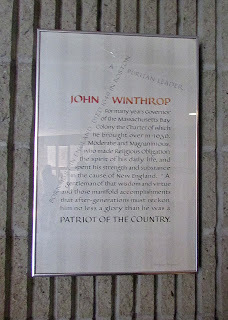

The building is a 21st-century ultra-modern construction. Winthrop and other First Church founders

Winthrop and other First Church founders

are remembered with calligraphic pictures

at the back of the main sanctuary.*Christy K Robinson is the author of five books, three of them revolving around the titans of New England. Click their titles to read the five-star reviews and purchase the paperback or Kindle editions.

Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014)

On my first day in Boston in years, I visited the graves of Gov. John Winthrop and his family, Rev. John Cotton, Rev. John Wilson, Rev. John Davenport, Isaac Johnson, and others who I learned to know very well as I researched and wrote my books on the Dyers.*

Click to enlarge the map

Click to enlarge the mapThey were buried in what is now known as the King's Chapel Burying Ground. Boston was founded in 1630 to be a Puritan version of the New Jerusalem, where its people would be able to live good lives and prove their election (predestination) to eternal life. It was never the heavenly City Upon a Hill that they hoped it would be, but their rebellious spirit did create a beacon of culture, education, commerce, and patriotism that still shines brightly today.

In the 1680s, that rebellious nature, and their refusal to produce their royal charter from 1629 after repeated recalls by kings and Parliaments, came to (virtual) blows with the appointment of a royal governor, Sir Edmund Andros. During his short term, he declared there was no other land available in Boston (because the Calvinist Puritans wouldn't sell any for a Church of England meetinghouse), and an Anglican church must be built right there on the cemetery. So in 1686, the graves of Boston's founders were disturbed, moved, or otherwise covered by construction of what came to be known as King's Chapel. (Imagine how the fur would fly in Boston parlors!)

And so it was that the first founders of Boston, who had left the English church at great expense to their lives and estates, were disturbed by that very church not long after their deaths.

I walked down Beacon Street in the steamy heat to visit the graves of the men who I didn't necessarily like as I researched my books on Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson, but who I greatly respected for the commitment of their very lives and families and fortunes to the Christian utopia they hoped to build. These were never cartoon villains as I read their letters, journals, and testimony, but human beings who were well-respected and loved by many. They were leaders who inspired their followers. They were titans.

(Click photos to enlarge.)

Burial vault for Gov. John Winthrop's family. Once down

Burial vault for Gov. John Winthrop's family. Once downthe steps, the vault extends under the fence and sidewalk. I

couldn't detect any inscription on the tomb cover.

Though his grave appears neglected, John Winthrop

Though his grave appears neglected, John Winthropis remembered at Boston First Church in the Back Bay

neighborhood of Boston, far from its original place near the harbor.

He was a founder of the church in 1630, but it is no longer

Puritan/Congregational. It's Unitarian Universalist.

The building is a 21st-century ultra-modern construction.

Winthrop and other First Church founders

Winthrop and other First Church founders are remembered with calligraphic pictures

at the back of the main sanctuary.*Christy K Robinson is the author of five books, three of them revolving around the titans of New England. Click their titles to read the five-star reviews and purchase the paperback or Kindle editions.

Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014)

Published on August 17, 2016 00:00

August 10, 2016

Where the Rhode Island Assembly met in Newport

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

The Rhode Island General Assembly met in homes and inns for decades before a Colony House was purpose-built for the assembly's business meetings.

White Horse Tavern, a Newport establishment dating to the 1650s,

White Horse Tavern, a Newport establishment dating to the 1650s,

first as the home of Francis Brinley, “the massively framed building

and quarter acre of land fenced with Pailes at the corner of

Farewell and Marlborough Streets”;

then in 1673, it was converted to a tavern by William Mayes, Sr.During my July 2016 visit to Newport, I was treated to dinner at the White Horse Tavern by my new friends, Newport residents Paul and Valerie Debrule. The White Horse Tavern was one of the places that the Rhode Island colonial government met in the 17th and 18th centuries.

We had the latest reservations for dinner that night because I'd been speaking at the Barnes & Noble Booksellers earlier in the evening. The restaurant was packed with people when we arrived at 8:15. Except for one or two people in the bar, we were the last to leave, and the manager kindly showed me around the building. To access the upstairs dining room and bar, we climbed a very narrow circular staircase. The ladies' room, with its three tiny stalls, was smaller than you'd find in some private homes. The levels changed on the hardwood floors between the older and newer parts of the house: there was a slant down from the entry lobby to the dining room. (The newer part of the house faces the street corner in the photo here.) Because it was summer, and we were in a heat wave, there were no fires in the working fireplaces.

Though the Rhode Island Assembly, of which William Dyer was a member for many years, didn't meet at this house until some years after he died in 1677 at age 68, it's a sure thing that William would have enjoyed meals or drinks with his colleagues and friends in this building in 1673 and afterward. And so would his sons and grandsons.

From an 1897 book published by the state of Rhode Island:

Did you notice the final paragraph of that selection? It's another instance of Rhode Islanders believing heartily in the separation of church and state. They were upset that a minister held church services in the Colony House, and they resolved that the government building should be used only for judicial and military business. Rev. Clapp was a Congregational (Puritan) minister from Dorchester, Massachusetts who preached in Newport for 50 years. It's worth noting that even though the Puritans had cast out the original founders of Rhode Island, there were Puritan congregations meeting in peace right alongside the Episcopalians, Baptists, Quakers, Catholics, Jews, and others. As long as there was no mixture of religion and government, all was well.

Learn more about the White Horse Tavern at their website .

One of the dining rooms in the "new" part of the tavern,

One of the dining rooms in the "new" part of the tavern,

added after the Revolutionary War When we arrived for our dinner reservation, the tavern

When we arrived for our dinner reservation, the tavern

was packed, but as we were the last to leave, it was set up

for the next meal.

Tables and fireplace in the upstairs bar in the 1652 part

Tables and fireplace in the upstairs bar in the 1652 part

of the building. Imagine William Dyer eating a roast

chicken or seafood, and drinking with friends. The bar upstairs, in the oldest part of the building. There

The bar upstairs, in the oldest part of the building. There

was another bar in another room, which had a Victorian-era

wooden "cage" around it that could be raised and lowered, probably

to keep the liquor from being stolen when the bar wasn't manned. My Newport hosts, Paul and Valerie Debrule

My Newport hosts, Paul and Valerie Debrule

The Rhode Island General Assembly met in homes and inns for decades before a Colony House was purpose-built for the assembly's business meetings.

White Horse Tavern, a Newport establishment dating to the 1650s,

White Horse Tavern, a Newport establishment dating to the 1650s,first as the home of Francis Brinley, “the massively framed building

and quarter acre of land fenced with Pailes at the corner of

Farewell and Marlborough Streets”;

then in 1673, it was converted to a tavern by William Mayes, Sr.During my July 2016 visit to Newport, I was treated to dinner at the White Horse Tavern by my new friends, Newport residents Paul and Valerie Debrule. The White Horse Tavern was one of the places that the Rhode Island colonial government met in the 17th and 18th centuries.

We had the latest reservations for dinner that night because I'd been speaking at the Barnes & Noble Booksellers earlier in the evening. The restaurant was packed with people when we arrived at 8:15. Except for one or two people in the bar, we were the last to leave, and the manager kindly showed me around the building. To access the upstairs dining room and bar, we climbed a very narrow circular staircase. The ladies' room, with its three tiny stalls, was smaller than you'd find in some private homes. The levels changed on the hardwood floors between the older and newer parts of the house: there was a slant down from the entry lobby to the dining room. (The newer part of the house faces the street corner in the photo here.) Because it was summer, and we were in a heat wave, there were no fires in the working fireplaces.

Though the Rhode Island Assembly, of which William Dyer was a member for many years, didn't meet at this house until some years after he died in 1677 at age 68, it's a sure thing that William would have enjoyed meals or drinks with his colleagues and friends in this building in 1673 and afterward. And so would his sons and grandsons.

From an 1897 book published by the state of Rhode Island:

The first General Assembly was held in May, 1647, at Portsmouth. On this occasion "it was voted and found that the major part of the colony were present at this assembly, whereby was full power to transact." The charter was adopted and a government formed under it. In 1648 the General Assembly met at Providence; in 1649 at Warwick; in 1650 at Newport. The sessions of the assembly were usually limited in these early times to three or four days. The adjournments from day to day were commonly until 6 o'clock the next morning, or until half an hour or an hour after sunrise. At the meeting held in Portsmouth in June, 1655, the adjournment on the 29th of the month was "till morninge sunn an houre high and he that stays longer shall pay twelve pence." On June 29th the sun rises at 4:25 A.M., which brought the meeting of the assembly at about 5:30 in the morning. No suitable buildings being in existence, the assembly met in public inns or at the houses of prominent persons. In May, 1676, the assembly met in Newport at the house of Capt. Morris. This was undoubtedly Capt. Richard Morris, who was often the bearer of important letters between the assembly of Connecticut and of Rhode Island. In 1676 it was voted that the assembly "sett in time of election in the kitchen of Henry Palmer's house at Newport." At different times during the latter part of the seventeenth century, the assembly met at the house of William Mayes, innkeeper of Newport [this would be the White Horse Tavern]; of John Davis, Newport; of Col. John Low, Warwick; of John Whipple, Providence. In 1734-5 the meeting place was at the house of the Widow Drake in East Greenwich; in 1738-41 at the house of Thomas Potter in Newport. In the "last year Thomas Potter was allowed £100 for the use of his house for holding the general elections and for the meetings of the assembly and the court.”The first Colony House was erected at Newport about 1690. It was built of wood, and occupied the site of the present State House in Newport. It was used by the General Assembly and also by the town council of Newport. In 1694-5 the Rev. Nathaniel Clapp of Dorchester occupied the Colony House for religious meetings. It caused considerable dissatisfaction and resulted in the passage of a resolution by the General Assembly on July 2. 1695, "whereas several and most of the inhabitants, freemen of this colony, are dissatisfied that the Colony House is [approved] to other uses than what it was built for; therefore upon consideration thereof, by this assembly and to settle the House for the use it was built, do hereby order and declare, that the said Colony House in Newport, shall not be [approved] for any other use than judicial and military affairs: and not for any ecclesiastical use or uses of that nature." A portion of the first Colony House about 1738 or 1739 was moved to Prison Street in Newport, where it still stands occupied as a tenement house. Another portion was removed to Broad Street, now Broadway, iu Newport, and has since been entirely demolished.https://books.google.com/books?id=qgNLAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA4-PA13&lpg=RA4-PA13&dq=Where+did+assembly+meet+in+Newport+in+1650s?&source=bl&ots=tVeRegnbq8&sig=2PXka-PNDlWFbivhiWJyOEiZcjk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjCjqfBj7HOAhXH7SYKHTVJAQ4Q6AEILDAC#v=onepage&q=Where%20did%20assembly%20meet%20in%20Newport%20in%201650s%3F&f=falseAnnual Report of the State Board of Pharmacy Made to the General Assembly. E.L. Freeman and Sons, Printers to the State: Providence, Rhode Island, 1897The first paragraph says that the government meetings must "adjourn" (close) by an hour past sunrise. I take that to mean that they worked at their own business during the day and met for government business by night. Usually, the assembly met at least quarterly, and sometimes more often.

Did you notice the final paragraph of that selection? It's another instance of Rhode Islanders believing heartily in the separation of church and state. They were upset that a minister held church services in the Colony House, and they resolved that the government building should be used only for judicial and military business. Rev. Clapp was a Congregational (Puritan) minister from Dorchester, Massachusetts who preached in Newport for 50 years. It's worth noting that even though the Puritans had cast out the original founders of Rhode Island, there were Puritan congregations meeting in peace right alongside the Episcopalians, Baptists, Quakers, Catholics, Jews, and others. As long as there was no mixture of religion and government, all was well.

Learn more about the White Horse Tavern at their website .

One of the dining rooms in the "new" part of the tavern,

One of the dining rooms in the "new" part of the tavern, added after the Revolutionary War

When we arrived for our dinner reservation, the tavern

When we arrived for our dinner reservation, the tavernwas packed, but as we were the last to leave, it was set up

for the next meal.

Tables and fireplace in the upstairs bar in the 1652 part

Tables and fireplace in the upstairs bar in the 1652 partof the building. Imagine William Dyer eating a roast

chicken or seafood, and drinking with friends.

The bar upstairs, in the oldest part of the building. There

The bar upstairs, in the oldest part of the building. Therewas another bar in another room, which had a Victorian-era

wooden "cage" around it that could be raised and lowered, probably

to keep the liquor from being stolen when the bar wasn't manned.

My Newport hosts, Paul and Valerie Debrule

My Newport hosts, Paul and Valerie Debrule

Published on August 10, 2016 00:00

August 4, 2016

Visiting Newport Historical Society

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

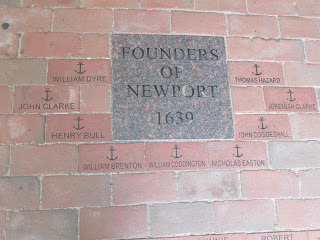

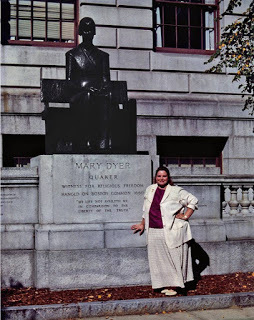

William Dyer's name is to the left of the center tile.On my recent visit to Newport, Rhode Island, on a mission to do research, and get a Dyer monument project rolling, I visited the Newport Historical Society. Their museum and shop is located at the nearby Brickmarket. Outside the shop is a brick mosaic with the Newport co-founders' names on it.

William Dyer's name is to the left of the center tile.On my recent visit to Newport, Rhode Island, on a mission to do research, and get a Dyer monument project rolling, I visited the Newport Historical Society. Their museum and shop is located at the nearby Brickmarket. Outside the shop is a brick mosaic with the Newport co-founders' names on it.  At Newport Historical Society:

At Newport Historical Society: Christy Robinson, author, with Molly Bruce Patterson,

archivist and manager of digital initiatives. The documents

on the table were written by William Dyer, and there were

other documents written by William's descendant, about

90 years later. I made an appointment to visit the Newport Historical Society to view documents in William Dyer's handwriting. They had several papers there from the 1640s, that I was able to breathe upon at least, though they're very fragile and touching 400-year-old documents is not a best practice for preservation. They photographed the documents (for a price) and sent me the links to download my purchases.

Seventh-day Baptists in Newport

While I was in the NHS headquarters building waiting for my appointment, my friend Valerie and I wandered around the main floor, and into a chapel. The NHS membership man, Mathew J. DeLaire, left his desk to show us around the chapel, which was actually an 18th-century Seventh-day Baptist meetinghouse . I asked if I could take photos of the room, but was told no. Click that link above to see the photos on their website.

The Sabbatarians (Saturday) and first-day (Sunday) Baptists shared the same minister, as I knew they did in Shiloh, New Jersey, where I had numerous SDB ancestors for many generations. In fact, there was a strong connection between Newport Baptists and the Shiloh Baptists: Obadiah Holmes, the Newport Baptist pastor when Dr. Jeremiah Clarke was acting as the Rhode Island agent in England, had a son by the same name. Obadiah Sr. was whipped to a bloody pulp by Massachusetts Bay Colony Puritans in 1650 when he celebrated Communion with a Baptist man in Salem. The son, Obadiah Holmes Jr., practiced his Baptist ministry in New Jersey and was a well-known colleague of Rev. Nathaniel Jenkins. Jenkins was a Baptist minister who also was a New Jersey assemblyman in the early 1700s. He stood up against a bill that would punish people for believing in a unitarian Deity rather than a trinitarian Deity, and the bill was quashed. Rev. Jenkins was only two or at most three "degrees of Kevin Bacon" from Mary Dyer! Read my article about Jenkins and religious liberty at http://rootingforancestors.blogspot.com/2015/01/nathaniel-jenkins-another-brick-in-wall.html

Charles Dyer's headstone in Newport's Common Burying Ground

I met Bert Lippincott, NHS librarian and genealogist, who marked a map of Common Burying Ground so I could visit the grave of Charles Dyer, 1650-1709. Charles may have been buried first on the Dyer home farm, where he lived after his father and brothers died. His remains were moved to the large cemetery later.

Common Burying Ground

Common Burying Groundclick to enlarge

Dyre Avenue in the CBG cemetery

Dyre Avenue in the CBG cemetery Lovely ancient tree with old headstones in CBG

Lovely ancient tree with old headstones in CBG Headstone of Charles Dyre:

Headstone of Charles Dyre: Here Lyeth Ye Body of Charles Dyre Senior, He Dececed May 15, 1709, Aged 59 Years.

Christy K Robinson is the author of this Dyer website and three five-star-reviewed books on the Dyers, available by clicking these links.

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on August 04, 2016 00:30

July 29, 2016

In the steps of William and Mary Dyer

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Flying into Boston over the harbor.

Flying into Boston over the harbor.

Logan International Airport is built on an island and landfill.In July 2016, I traveled from my home in Arizona to Boston, Massachusetts, to participate in a historical event conducted by the Anne Marbury Hutchinson Foundation. The five-day event celebrated Anne Hutchinson on her 425th birthday with a ceremony at her statue on the Massachusetts Statehouse grounds, lectures and a reception at the Congregational (Puritan) Library and Archives, a panel at the New England Historical Genealogical Society, a tour of the Boston First Church (organized in 1630 by Gov. John Winthrop, but now an ultra-modern building in a different location), a walking tour of Hutchinson sites, a quick trip to Harvard University (founded to train ministers to refute upstart women like Anne Hutchinson), and then a road trip to Portsmouth, Rhode Island and Eastchester, New York.

Dyer monument!

I've returned with all kinds of resources to share with you, and I was able to meet with some important people who are excited about creating a monument to Mary and William Dyer in Newport. There's nothing firm yet, as it's just begun and will be a multi-year project, but there is an opportunity for a Dyer monument placement in Newport. When it's time to combine financial resources of corporate sponsors, city government, crowdsourcing, and private donors, you'll be a much-needed component, and when it's time for the grand opening or unveiling, you'll have plenty of notice to plan your travel and vacation time to be there for those events and much more.

Wonking out on 17th-century history

Apart from group activities, I also was able to revisit the Mary Dyer statue at the Statehouse, but missed visiting a couple of other points I wanted to see. I "hiked" in the 95/90 heat and humidity to the King's Chapel Burying Ground to find the grave of Gov. John Winthrop and Rev. John Cotton, and accidentally found an ancestor's headstone there (that's my kind of Pokemon Go). I also visited Plimoth Plantation (1624 English and Wampanoag villages) as the guest of culinary historian Kathleen Wall, who treated me to 17th century Pilgrim and Native American foods for lunch.

I'm grateful to friends (and even strangers!) who contributed to my GoFundMe campaign to pay my trip expenses. My event at Harvard University was changed to a professional video shoot there, and that means more people will have access to the Dyer story.

During my time in Rhode Island, I walked in the steps of the Dyers, 375 years ago, visiting Dyer Point/Battery Park, the area on the west coast where their farm was and where they were buried, the Portsmouth Founders Brook Park where they lived in 1638, the cemetery where Charles Dyer (their youngest son) is buried, the White Horse Tavern where William almost surely drank a pint in the 1670s, and taking an 80-foot sailboat ride out on Narragansett Bay. I visited the Newport Historical Society and viewed two documents in William Dyer's handwriting, and ordered a copy of a deed on which Mary Dyer's signature appears.

My hosts, who were friends of friends, and now are my friends, live in a beautiful home in the "boot" of Newport (see maps below). I went to sleep with a lightning show in the guest room windows and awoke refreshed with a view of a pond, a marsh with birdsong and tiny frogs, and the Atlantic Ocean breaking on the rocks nearby. They treated me like a celebrity, and helped with networking for the monument project.

I gave an author talk at the Middletown Barnes & Noble Booksellers, and met Suegray Fitzpatrick, a jewelry designer, from whom I purchased a necklace pendant of an anchor with the word "hope" that is similar to the Rhode Island state seal that William Dyer presented to the colonial assembly in 1648--and is still in use on the Rhode Island flag and seal today. I even flew into and out of Boston Harbor, as the Dyers did in ocean-going ships (see photo above).

1777 Revolutionary War map, plus Google satellite map of the southern end of Aquidneck Island, where Newport is located. Note "Dyers Point" is the same location as the modern "Ft. Greene" which is a lovely point called Battery Park. The island shape has not significantly changed in 240 years (which we can project backward all the way to the Ice Age).

1777 Revolutionary War map, plus Google satellite map of the southern end of Aquidneck Island, where Newport is located. Note "Dyers Point" is the same location as the modern "Ft. Greene" which is a lovely point called Battery Park. The island shape has not significantly changed in 240 years (which we can project backward all the way to the Ice Age).

Newport (on Aquidneck Island) from the air, with part of Conanicut Island under the clouds, on my Boston-to-New York flight on July 26, 2016. I awoke on the southern coast of the island, drove my rental car up to Boston, took an Uber cab to the airport (in Boston Harbor), and then flew over Narragansett Bay and Shelter Island, NY. A fitting end of a week-long history fest for a Dyer follower!

Newport (on Aquidneck Island) from the air, with part of Conanicut Island under the clouds, on my Boston-to-New York flight on July 26, 2016. I awoke on the southern coast of the island, drove my rental car up to Boston, took an Uber cab to the airport (in Boston Harbor), and then flew over Narragansett Bay and Shelter Island, NY. A fitting end of a week-long history fest for a Dyer follower!

And then there's DYER ISLAND, which the 28-year-old William Dyer asked for and received in early 1638 when the Hutchinson party were purchasing Rhode Island from the Native Americans. Behind (to the west of) Dyer Island is part of Prudence Island, where Governor Winthrop owned land. At the bottom, to the east of Dyer Island, is Aquidneck Island and the town of Portsmouth. Dyer Island is a bird sanctuary. Photo by Christy K Robinson, July 26, 2016.

And then there's DYER ISLAND, which the 28-year-old William Dyer asked for and received in early 1638 when the Hutchinson party were purchasing Rhode Island from the Native Americans. Behind (to the west of) Dyer Island is part of Prudence Island, where Governor Winthrop owned land. At the bottom, to the east of Dyer Island, is Aquidneck Island and the town of Portsmouth. Dyer Island is a bird sanctuary. Photo by Christy K Robinson, July 26, 2016.

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015) Sailing on Narragansett Bay,

Sailing on Narragansett Bay,

with the Dyer farm far behind, in the

center of the photo.

Flying into Boston over the harbor.

Flying into Boston over the harbor. Logan International Airport is built on an island and landfill.In July 2016, I traveled from my home in Arizona to Boston, Massachusetts, to participate in a historical event conducted by the Anne Marbury Hutchinson Foundation. The five-day event celebrated Anne Hutchinson on her 425th birthday with a ceremony at her statue on the Massachusetts Statehouse grounds, lectures and a reception at the Congregational (Puritan) Library and Archives, a panel at the New England Historical Genealogical Society, a tour of the Boston First Church (organized in 1630 by Gov. John Winthrop, but now an ultra-modern building in a different location), a walking tour of Hutchinson sites, a quick trip to Harvard University (founded to train ministers to refute upstart women like Anne Hutchinson), and then a road trip to Portsmouth, Rhode Island and Eastchester, New York.

Dyer monument!

I've returned with all kinds of resources to share with you, and I was able to meet with some important people who are excited about creating a monument to Mary and William Dyer in Newport. There's nothing firm yet, as it's just begun and will be a multi-year project, but there is an opportunity for a Dyer monument placement in Newport. When it's time to combine financial resources of corporate sponsors, city government, crowdsourcing, and private donors, you'll be a much-needed component, and when it's time for the grand opening or unveiling, you'll have plenty of notice to plan your travel and vacation time to be there for those events and much more.

Wonking out on 17th-century history

Apart from group activities, I also was able to revisit the Mary Dyer statue at the Statehouse, but missed visiting a couple of other points I wanted to see. I "hiked" in the 95/90 heat and humidity to the King's Chapel Burying Ground to find the grave of Gov. John Winthrop and Rev. John Cotton, and accidentally found an ancestor's headstone there (that's my kind of Pokemon Go). I also visited Plimoth Plantation (1624 English and Wampanoag villages) as the guest of culinary historian Kathleen Wall, who treated me to 17th century Pilgrim and Native American foods for lunch.

I'm grateful to friends (and even strangers!) who contributed to my GoFundMe campaign to pay my trip expenses. My event at Harvard University was changed to a professional video shoot there, and that means more people will have access to the Dyer story.

During my time in Rhode Island, I walked in the steps of the Dyers, 375 years ago, visiting Dyer Point/Battery Park, the area on the west coast where their farm was and where they were buried, the Portsmouth Founders Brook Park where they lived in 1638, the cemetery where Charles Dyer (their youngest son) is buried, the White Horse Tavern where William almost surely drank a pint in the 1670s, and taking an 80-foot sailboat ride out on Narragansett Bay. I visited the Newport Historical Society and viewed two documents in William Dyer's handwriting, and ordered a copy of a deed on which Mary Dyer's signature appears.

My hosts, who were friends of friends, and now are my friends, live in a beautiful home in the "boot" of Newport (see maps below). I went to sleep with a lightning show in the guest room windows and awoke refreshed with a view of a pond, a marsh with birdsong and tiny frogs, and the Atlantic Ocean breaking on the rocks nearby. They treated me like a celebrity, and helped with networking for the monument project.

I gave an author talk at the Middletown Barnes & Noble Booksellers, and met Suegray Fitzpatrick, a jewelry designer, from whom I purchased a necklace pendant of an anchor with the word "hope" that is similar to the Rhode Island state seal that William Dyer presented to the colonial assembly in 1648--and is still in use on the Rhode Island flag and seal today. I even flew into and out of Boston Harbor, as the Dyers did in ocean-going ships (see photo above).

1777 Revolutionary War map, plus Google satellite map of the southern end of Aquidneck Island, where Newport is located. Note "Dyers Point" is the same location as the modern "Ft. Greene" which is a lovely point called Battery Park. The island shape has not significantly changed in 240 years (which we can project backward all the way to the Ice Age).

1777 Revolutionary War map, plus Google satellite map of the southern end of Aquidneck Island, where Newport is located. Note "Dyers Point" is the same location as the modern "Ft. Greene" which is a lovely point called Battery Park. The island shape has not significantly changed in 240 years (which we can project backward all the way to the Ice Age).  Newport (on Aquidneck Island) from the air, with part of Conanicut Island under the clouds, on my Boston-to-New York flight on July 26, 2016. I awoke on the southern coast of the island, drove my rental car up to Boston, took an Uber cab to the airport (in Boston Harbor), and then flew over Narragansett Bay and Shelter Island, NY. A fitting end of a week-long history fest for a Dyer follower!

Newport (on Aquidneck Island) from the air, with part of Conanicut Island under the clouds, on my Boston-to-New York flight on July 26, 2016. I awoke on the southern coast of the island, drove my rental car up to Boston, took an Uber cab to the airport (in Boston Harbor), and then flew over Narragansett Bay and Shelter Island, NY. A fitting end of a week-long history fest for a Dyer follower!  And then there's DYER ISLAND, which the 28-year-old William Dyer asked for and received in early 1638 when the Hutchinson party were purchasing Rhode Island from the Native Americans. Behind (to the west of) Dyer Island is part of Prudence Island, where Governor Winthrop owned land. At the bottom, to the east of Dyer Island, is Aquidneck Island and the town of Portsmouth. Dyer Island is a bird sanctuary. Photo by Christy K Robinson, July 26, 2016.

And then there's DYER ISLAND, which the 28-year-old William Dyer asked for and received in early 1638 when the Hutchinson party were purchasing Rhode Island from the Native Americans. Behind (to the west of) Dyer Island is part of Prudence Island, where Governor Winthrop owned land. At the bottom, to the east of Dyer Island, is Aquidneck Island and the town of Portsmouth. Dyer Island is a bird sanctuary. Photo by Christy K Robinson, July 26, 2016.  Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:

Christy K Robinson is the author of five books:We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Sailing on Narragansett Bay,

Sailing on Narragansett Bay, with the Dyer farm far behind, in the

center of the photo.

Published on July 29, 2016 15:44

July 4, 2016

Revolutionary New Englanders--in the 1600s

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Because Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer, Roger Williams and John Clarke, and almost every co-founder of Rhode Island, were very religious people (zealous Puritans, Antinomians, Baptists, Quakers, etc.) who sacrificed worldly goods and even their lives for their faith in God, we might think of these "Founders before the Founding Fathers" as desirous of a religious utopia in the New World.

Not. At. All.

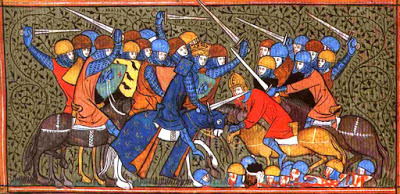

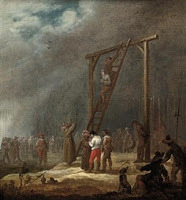

They'd faced religious persecution by their governments in Europe, to such a degree that they fled to the wilds of North America. But the people who governed the new society were theocrats who based their laws in the Old Testament laws given to the Israelites in the wilderness of Sinai. Ministers and magistrates locked arms and wills to accuse and prosecute, imprison, torture, and execute in the name of God. This marriage of religion and government is called theocracy.

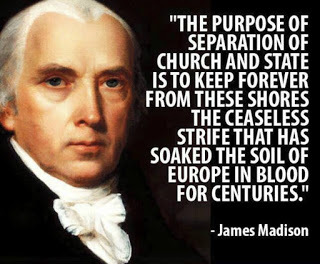

Williams, the Hutchinsons, the Dyers, and scores of others were banished from Massachusetts Bay Colony, reviled as heretics, and ridiculed for the rest of their lives, for insisting on liberty of conscience and separation of church and state. In the 1630s, though they believed and practiced their deep faith, they were the first people in Western civilization to form a secular (non-religious) government. They insisted on it, to the degree that religious liberty is encoded in the charter (constitution) of Rhode Island, which was central to the formation of the First Amendment to the US Constitution 130 years later.

In the 21st century, particularly in election years, there are many people who believe that the United States is a Christian nation, founded on Christian principles. Real, documented history says that is not true. The documents of the United States are completely secular. (Read the link below.)

The article at the link below was posted in February 2016, because theocratic advocates Sen. Ted Cruz, Sen. Marcus Rubio, Gov. Mike Huckabee, fundamentalist fundraising organizations, and others have agitated against Supreme Court (yes, conservative-majority Supreme Court!) decisions on same-sex rights and contraception and abortion. In state legislatures around the country, unconstitutional "bathroom" laws were passed against transgender people. (A Tennessee lawmaker said he knew their law was unconstitutional and he simply didn't care.) Those beliefs come from a religious base, which not everyone follows. And if everyone is not protected, there is no liberty.

Religion enforced by government always results in oppression.

Ancient Egyptians on IsraelitesIsraelites on Moabites/Canaanites, etc.Assyrians and Babylonians on HebrewsRomans on Greeks, Egyptians, Jews, and ChristiansChristians versus pagans Western Christianity versus Orthodox or Coptic Christianity Christians on Jews and Muslims Muslims versus Christians (the Crusades)Catholics versus reformersThe Inquisition in Europe and Latin America Anglicans versus Catholics and non-conformists (Puritan, Brownists like Pilgrims, Quaker, etc.)Portuguese Catholics versus Reformed Dutch and Jews in Brazil Puritans versus Quakers and BaptistsGenocidal and terrorist purges are often based in religion (World War II, Yugoslavia, Armenia, ISIS, etc.) Different sects of Muslims on Muslims The problem is not that people have strong religious beliefs. The problem is enforcing one set of beliefs on another person or a community, or discriminating against another because of their beliefs or behaviors.

Ancient Egyptians on IsraelitesIsraelites on Moabites/Canaanites, etc.Assyrians and Babylonians on HebrewsRomans on Greeks, Egyptians, Jews, and ChristiansChristians versus pagans Western Christianity versus Orthodox or Coptic Christianity Christians on Jews and Muslims Muslims versus Christians (the Crusades)Catholics versus reformersThe Inquisition in Europe and Latin America Anglicans versus Catholics and non-conformists (Puritan, Brownists like Pilgrims, Quaker, etc.)Portuguese Catholics versus Reformed Dutch and Jews in Brazil Puritans versus Quakers and BaptistsGenocidal and terrorist purges are often based in religion (World War II, Yugoslavia, Armenia, ISIS, etc.) Different sects of Muslims on Muslims The problem is not that people have strong religious beliefs. The problem is enforcing one set of beliefs on another person or a community, or discriminating against another because of their beliefs or behaviors.Liberty of conscience is what Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer, Roger Williams and John Clarke lived for, and in Mary Dyer's case, died for. They didn't impose their beliefs on others, but advocated for the full rights of others. They were the Founders before the Founders, the great-great grandparents of the revolutionaries of the United States and authors of its Constitution.

“Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?”

― Sandra Day O'Connor, conservative Supreme Court Justice

Read the link:

Founding Fathers: We Are Not a Christian Nation

by Jeff Schweitzer, scientist and former White House Senior Policy Analyst; Ph.D. in neurophysiology

Published on July 04, 2016 14:32

June 29, 2016

Up close and personal with the Hutchinson and Dyer statues

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Hutchinson statue seen from

Hutchinson statue seen from Beacon Street over the iron fence.

That's as close as you get,

most times.

The memorial statue of Anne Marbury Hutchinson was cast in bronze in 1915, and placed on the grounds of the Massachusetts State House in 1922. For generations, it was a landmark easily visited by descendants and admirers of Hutchinson. But after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the state raised an iron fence around the statehouse, and no access is granted except by permit. For most people, the best they can do is shoot photos with a long lens, from Beacon Street. (The Mary Dyer statue, on the east wing of the State House, is fenced but open to the public.)

But lucky ticket holders have a chance to get up close and personal on July 20, 2016, the 425th anniversary of Anne Marbury's baptism. The Anne Hutchinson Society, in conjunction with OurFoundingMothers.org, is holding a ceremony at the statue in Anne's honor. Honored guests include biographer Eve LaPlante and former Massachusetts governor, the Honorable Michael Dukakis, who granted a pardon to Mistress Hutchinson in 1987, 349 years after she was convicted of heresy and banished from Massachusetts Bay Colony. Bring your camera and stock up on photos! Rub elbows with Hutchinson descendants and friends. For information on and tickets to the Hutchinson statue ceremony, visit https://www.eventbrite.com/e/founding-mothers-celebration-state-house-event-the-hon-michael-dukakis-tickets-26222921464 .

For info and tickets for other events surrounding Anne Hutchinson, visit: http://ourfoundingmothers.org/learning-event-series/

Christy K Robinson is the author of three books on William and Mary Dyer,

Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014)

and of this Dyer history site. The Dyers' lives were inextricably linked with Anne and William Hutchinson, Gov. John Winthrop, Rev. John Cotton, and many others whose descendants can be found all over North America. Read their stories in the Robinson books.

Published on June 29, 2016 20:13

June 13, 2016

Review of "The Savage Apostle"

King Philip's War, 1675-1676, was fought between the Native American tribes of New England, and the English colonists, many who were first-generation emigrants like William and Mary Dyer (William lived until 1677), or their children and grandchildren who were born in the colonies. The Dyers may have known Rev. John Eliot if he was one of the inquisitors on Anne Hutchinson's trial. William Dyer was acquainted with the Indian sachems Massasoit (whose signature mark was a sailboat or a bow) and his son Metacom/Metacomet. The Dyers' sons were involved with the war, and Samuel Dyer, their eldest son, rescued Rhode Island colonists from grave danger when he evacuated them to Newport. Katherine Marbury Scott lost both her sons in the war. Edward Hutchinson died a short time after being struck by a musket ball late in the conflict. We don't know much about the women who suffered death, injury, the firings of their homes and crops, and the loss of their children, but we can learn from the story of Mary Rowlandson, who was abducted by Native Americans and then redeemed. But fear not, our friend Jo Ann Butler is nearly finished with her volume encompassing this time, The Golden Shore.

I invite you to learn more about King Philip's War by reading The Savage Apostle, by John B. Kachuba. You can access the Amazon sales page and the other reviews by clicking the title hotlink.

The Savage Apostle, by John B. Kachuba(Review by Christy K Robinson)

The Savage Apostle, named after John Eliot, the Congregational (Puritan) pastor to the Native Americans (“savages”) of New England, is the first historical novel by author John B. Kachuba. The “novel” genre assignment seems wrong, when the events and people were real and documented, but the narrative follows the thoughts and speech of two primary figures: Rev. John Eliot (1604-1690) and the Wampanoag sachem Metacom (1638-1676), also known as King Philip. Historical fiction can breathe new life into dusty history, when thought through as carefully as it was by author Kachuba.

The book begins with the musings of Eliot, who mourns the death of the Native American Sassamon, who was a Christian convert. Sassamon had been murdered and dumped in a frozen pond, perhaps by someone of his own tribe, or by the English settlers of Plymouth Colony. In 1675, tensions were high between the natives of New England, and the thousands of English families pushing them back into the wilderness. When the first settlers arrived in the 1620s and 1630s, they found whole villages made ghost towns by disease. They purchased land from native sachems, but by 1636, tensions broke out in the Pequot War, in which the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay militias massacred thousands and sold women and children captives to the Caribbean slave trade (because they had a naughty habit of running away from their “servanthood” in New England). As tens of thousands of settlers arrived in the Great Migration, the various tribes suffered encroachment on their lands and waters, destruction of their crops by English cattle, and overhunting of fowl and deer. Over the next decades, even as John Eliot tried to convert them to Christianity and “civilization,” they lost civil rights and were treated disrespectfully by the second generation of colonists.

In the book, Metacom has equal time with John Eliot, as they both realize that war will come to New England, no matter how hard they work to avoid it. They both envision innocent deaths and burned-out villages. Eliot wonders if he has failed his God when he sees the “Praying Indians” deserting their villages ahead of the war to return to their tribes. He agonizes over the will of God: why did God seem to direct his missionary work, and then deny Eliot, in his old age, the fulfillment of happy, fulfilled Christian converts? Metacom wants only to die peacefully as an old man, with his children and grandchildren nearby, and go to the afterlife to be with his father and brother, but his advisors are bent on avenging the executions of the three Pokanoket men who were falsely accused and falsely convicted of murdering Sassamon.

Author Kachuba’s depiction of the exhumed body of Sassamon was (as I imagine) quite realistic, but so was his depiction of sudden emotion from Rev. Eliot, looking on the decomposing body of his friend and convert. “From where I now stood, trembling, I had an unobstructed view of the corpse, a view I would gladly have given up so as to have Sassamon’s memory from happier times live on within me… I had to close my eyes for several moments to calm my wild heart. My knees shook and I thought I should fall.”

I’ve read several books set in the time before and during King Philip’s War (among them Flight of the Sparrow, by Amy Belding Brown; Mayflower, by Nathaniel Philbrick; Caleb’s Crossing, by Geraldine Brooks), and have seen descriptions of Eliot and his ministry, and the English versus Indian conflict from several outside angles. It’s a new dimension to read about the precursors to war through the eyes of Eliot and Metacom, who perhaps had the best perspective.

As an author and a student of 17th-century New England history, I found the personal narratives fascinating. The story is so believable as told here, that I’m tempted to think this is what must have happened. As a genealogy enthusiast, I knew some of the peripheral players in the story, and though they weren’t covered in detail in the book (which was proper), it drove me back to my files to compare information. And it fits! Those dusty ancestors contributed to the story in my head. Dr. Fuller administered a potion which may have killed Metacom’s brother. Others lived heroically through the atrocities of King Philip’s War, ferried colonists from grave danger to safety at Newport, or, like one great-great, didn’t survive, when he was taken captive and marched to Canada, where he was burned at the stake.

There were a few confusing bits in The Savage Apostle: Metacom’s flashbacks to his experiences with father and brother took us back about 13 years but didn’t explain the timehop. What was the medieval law of cruentation? And the Pokanoket name of Montaup (Mount Hope, Bristol, Rhode Island) and other places could have been set for the reader who is not from New England, by a map or two. Sure, I can Google them, but that would mean getting out of bed where I’m reading in the wee hours!

The book contains a reading list and discussion guide, and would be appropriate reading for high school and college history students, as well as history enthusiasts of all ages. The few descriptions of violence (at the very end of the book) are necessary to a book about the prelude to war. The physical book is well made and the text is easy on the eyes. The cover image appears to be an aerial view of a landscape with water and clouds in the distance. The cover texture feels a bit like peachskin.

Disclosure: The publisher sent me an advance copy of the book in exchange for an honest review.

I invite you to learn more about King Philip's War by reading The Savage Apostle, by John B. Kachuba. You can access the Amazon sales page and the other reviews by clicking the title hotlink.

The Savage Apostle, by John B. Kachuba(Review by Christy K Robinson)

The Savage Apostle, named after John Eliot, the Congregational (Puritan) pastor to the Native Americans (“savages”) of New England, is the first historical novel by author John B. Kachuba. The “novel” genre assignment seems wrong, when the events and people were real and documented, but the narrative follows the thoughts and speech of two primary figures: Rev. John Eliot (1604-1690) and the Wampanoag sachem Metacom (1638-1676), also known as King Philip. Historical fiction can breathe new life into dusty history, when thought through as carefully as it was by author Kachuba.

The book begins with the musings of Eliot, who mourns the death of the Native American Sassamon, who was a Christian convert. Sassamon had been murdered and dumped in a frozen pond, perhaps by someone of his own tribe, or by the English settlers of Plymouth Colony. In 1675, tensions were high between the natives of New England, and the thousands of English families pushing them back into the wilderness. When the first settlers arrived in the 1620s and 1630s, they found whole villages made ghost towns by disease. They purchased land from native sachems, but by 1636, tensions broke out in the Pequot War, in which the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay militias massacred thousands and sold women and children captives to the Caribbean slave trade (because they had a naughty habit of running away from their “servanthood” in New England). As tens of thousands of settlers arrived in the Great Migration, the various tribes suffered encroachment on their lands and waters, destruction of their crops by English cattle, and overhunting of fowl and deer. Over the next decades, even as John Eliot tried to convert them to Christianity and “civilization,” they lost civil rights and were treated disrespectfully by the second generation of colonists.

In the book, Metacom has equal time with John Eliot, as they both realize that war will come to New England, no matter how hard they work to avoid it. They both envision innocent deaths and burned-out villages. Eliot wonders if he has failed his God when he sees the “Praying Indians” deserting their villages ahead of the war to return to their tribes. He agonizes over the will of God: why did God seem to direct his missionary work, and then deny Eliot, in his old age, the fulfillment of happy, fulfilled Christian converts? Metacom wants only to die peacefully as an old man, with his children and grandchildren nearby, and go to the afterlife to be with his father and brother, but his advisors are bent on avenging the executions of the three Pokanoket men who were falsely accused and falsely convicted of murdering Sassamon.

Author Kachuba’s depiction of the exhumed body of Sassamon was (as I imagine) quite realistic, but so was his depiction of sudden emotion from Rev. Eliot, looking on the decomposing body of his friend and convert. “From where I now stood, trembling, I had an unobstructed view of the corpse, a view I would gladly have given up so as to have Sassamon’s memory from happier times live on within me… I had to close my eyes for several moments to calm my wild heart. My knees shook and I thought I should fall.”

I’ve read several books set in the time before and during King Philip’s War (among them Flight of the Sparrow, by Amy Belding Brown; Mayflower, by Nathaniel Philbrick; Caleb’s Crossing, by Geraldine Brooks), and have seen descriptions of Eliot and his ministry, and the English versus Indian conflict from several outside angles. It’s a new dimension to read about the precursors to war through the eyes of Eliot and Metacom, who perhaps had the best perspective.

As an author and a student of 17th-century New England history, I found the personal narratives fascinating. The story is so believable as told here, that I’m tempted to think this is what must have happened. As a genealogy enthusiast, I knew some of the peripheral players in the story, and though they weren’t covered in detail in the book (which was proper), it drove me back to my files to compare information. And it fits! Those dusty ancestors contributed to the story in my head. Dr. Fuller administered a potion which may have killed Metacom’s brother. Others lived heroically through the atrocities of King Philip’s War, ferried colonists from grave danger to safety at Newport, or, like one great-great, didn’t survive, when he was taken captive and marched to Canada, where he was burned at the stake.

There were a few confusing bits in The Savage Apostle: Metacom’s flashbacks to his experiences with father and brother took us back about 13 years but didn’t explain the timehop. What was the medieval law of cruentation? And the Pokanoket name of Montaup (Mount Hope, Bristol, Rhode Island) and other places could have been set for the reader who is not from New England, by a map or two. Sure, I can Google them, but that would mean getting out of bed where I’m reading in the wee hours!

The book contains a reading list and discussion guide, and would be appropriate reading for high school and college history students, as well as history enthusiasts of all ages. The few descriptions of violence (at the very end of the book) are necessary to a book about the prelude to war. The physical book is well made and the text is easy on the eyes. The cover image appears to be an aerial view of a landscape with water and clouds in the distance. The cover texture feels a bit like peachskin.

Disclosure: The publisher sent me an advance copy of the book in exchange for an honest review.

Published on June 13, 2016 23:04

June 8, 2016

Old Boston, the angels' view

© 2016 by Christy K Robinson

What a photo from above Boston.

What a photo from above Boston.

This was taken from Lincolnshire-based Kurnia Aerial Photography with a drone on June 6, 2016.

This large parish church, St Botolph's (aka "The Stump"), was the church where Rev. John Cotton was the minister for 20 years, and Anne and William Hutchinson attended here often. (Their children were baptized in the local church in Alford.) The young William Dyer and his parents and siblings lived in nearby Kirkby LaThorpe, so it's very possible that the Dyers occasionally or regularly attended this large church. St Botolph's (Anglican) church is located in Boston, Lincolnshire, near the northeast coast of England. Boston, Massachusetts, was named after this town in the hope that John Cotton would accept their repeated invitations to emigrate to New England. After The Book of Sports was republished by King Charles I, and the bishops and archbishop of the Church of England cracked down on Puritan power, Cotton was forced into hiding for a year lest he be imprisoned (which could be a death sentence in itself). He sailed to the new Boston in 1633, and about ten percent of old Boston followed him!

William Dyer and his father, a farmer who owned his land about 15 miles to the west (behind the drone camera), were certainly familiar with the market square at the east end of the church. Whether they brought crops or wool or livestock to market, Boston was a second "hometown" to them.

Christy K Robinson is the author of these five-star books, three of them about the Dyers (with liberal mention of Anne Hutchinson and son Edward):

Christy K Robinson is the author of these five-star books, three of them about the Dyers (with liberal mention of Anne Hutchinson and son Edward):

We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

What a photo from above Boston.

What a photo from above Boston.This was taken from Lincolnshire-based Kurnia Aerial Photography with a drone on June 6, 2016.

This large parish church, St Botolph's (aka "The Stump"), was the church where Rev. John Cotton was the minister for 20 years, and Anne and William Hutchinson attended here often. (Their children were baptized in the local church in Alford.) The young William Dyer and his parents and siblings lived in nearby Kirkby LaThorpe, so it's very possible that the Dyers occasionally or regularly attended this large church. St Botolph's (Anglican) church is located in Boston, Lincolnshire, near the northeast coast of England. Boston, Massachusetts, was named after this town in the hope that John Cotton would accept their repeated invitations to emigrate to New England. After The Book of Sports was republished by King Charles I, and the bishops and archbishop of the Church of England cracked down on Puritan power, Cotton was forced into hiding for a year lest he be imprisoned (which could be a death sentence in itself). He sailed to the new Boston in 1633, and about ten percent of old Boston followed him!

William Dyer and his father, a farmer who owned his land about 15 miles to the west (behind the drone camera), were certainly familiar with the market square at the east end of the church. Whether they brought crops or wool or livestock to market, Boston was a second "hometown" to them.

Christy K Robinson is the author of these five-star books, three of them about the Dyers (with liberal mention of Anne Hutchinson and son Edward):

Christy K Robinson is the author of these five-star books, three of them about the Dyers (with liberal mention of Anne Hutchinson and son Edward):We Shall Be Changed (2010) Mary Dyer Illuminated (2013) Mary Dyer: For Such a Time as This (2014) The Dyers of London, Boston, & Newport (2014) Effigy Hunter (2015)

Published on June 08, 2016 10:03

May 27, 2016

Where were Anne Hutchinson's trials held?

© 2016 Christy K Robinson

Have you been to Cambridge, Mass., which was at first called New Towne, and wondered where the meetinghouse was, when Anne Hutchinson was tried for heresy in 1637 and 1638?

The trial should have been held in Boston where Anne had committed her "crime" of teaching men, but there were too many supporters and friends there to guarantee a conviction, so the venue was moved to what is now Cambridge. The very strait-laced Gov. Thomas Dudley and others lived there, across the Charles River from the Shawmut Peninsula from Boston. In 1637, former Gov. Dudley actually accused former Gov. John Winthrop of being too lenient on lawbreakers, and current Gov. Harry Vane, that young whippersnapper in his early 20s, intervened. From Winthrop’s Journal entries, you can tell that he’s miffed at Vane’s attempt to reconcile the two older men who had founded the colony, but Winthrop knew his Journal was intended as a historical record, not a personal diary, so he kept his temper. But you couldn’t call Winthrop and Dudley bosom buddies, even though his daughter Mary Winthrop married Dudley’s son Samuel.

Holding Anne’s trials at the meetinghouse in New Towne was designed to make her defense more difficult. She had to walk from Boston (where she was staying at Rev. Cotton's home as a semi-prisoner) to the river ferry, and then from the ferry uphill to the meetinghouse, in whatever weather. She had two small children which could have been cared for by other family members, but it’s not easy to stay focused on your trial defense (she wasn’t allowed an attorney) when there are domestic issues to decide. And during both trials, she was on her own. William Hutchinson, William Dyer, and the other Antinomian men were scouting and buying the land for their town and farms when (as they all knew) Anne would be exiled.

It was at or near the end of Anne’s second trial in March 1638 that Mary Dyer took her hand as Anne walked out of the meetinghouse, having been excommunicated and banished. That’s when someone in the crowd outside said that Mary’s miscarriage five months before had been a “monster.”

Boston and Cambridge have changed in countless ways over the last 380 years. Swamps and bays were filled in and islands connected to the mainland. But though roads can be renamed, sometimes the modern streets and highways follow the original path. In my research for my books on Mary Dyer and her associates, I found a paragraph about the neighborhood near Harvard University (see text on the image), that pinpoints the location of the original meetinghouse. Then I went to Google Maps and zoomed in, and there it is. Not the meetinghouse, but the very place where Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer made their dramatic stand of solidarity and defiance. It took extraordinary courage and love for Mary to stand up, alone, before all those severe, frowning ministers and magistrates and take the hand of a woman who’d just been convicted of heresy. The map pin is stuck where the meetinghouse stood. Click the image to enlarge.

The map pin is stuck where the meetinghouse stood. Click the image to enlarge.

Christy K Robinson, the author of this Dyer research blog and three books on William and Mary Barrett Dyer, has been invited to participate in a conference on Anne Hutchinson, held in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York in July 2016. Christy will take her place on a panel discussion, and speak about Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer at Harvard University. (Which, as you may know, is a very big deal!) If the books, blog, and Facebook pages have been a valuable resource to your genealogy and family history, please consider making a gift to enable Christy to attend the conference. You may click this link to learn more:

https://www.gofundme.com/23txdvq8

Christy K Robinson, the author of this Dyer research blog and three books on William and Mary Barrett Dyer, has been invited to participate in a conference on Anne Hutchinson, held in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York in July 2016. Christy will take her place on a panel discussion, and speak about Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer at Harvard University. (Which, as you may know, is a very big deal!) If the books, blog, and Facebook pages have been a valuable resource to your genealogy and family history, please consider making a gift to enable Christy to attend the conference. You may click this link to learn more:

https://www.gofundme.com/23txdvq8

Have you been to Cambridge, Mass., which was at first called New Towne, and wondered where the meetinghouse was, when Anne Hutchinson was tried for heresy in 1637 and 1638?

The trial should have been held in Boston where Anne had committed her "crime" of teaching men, but there were too many supporters and friends there to guarantee a conviction, so the venue was moved to what is now Cambridge. The very strait-laced Gov. Thomas Dudley and others lived there, across the Charles River from the Shawmut Peninsula from Boston. In 1637, former Gov. Dudley actually accused former Gov. John Winthrop of being too lenient on lawbreakers, and current Gov. Harry Vane, that young whippersnapper in his early 20s, intervened. From Winthrop’s Journal entries, you can tell that he’s miffed at Vane’s attempt to reconcile the two older men who had founded the colony, but Winthrop knew his Journal was intended as a historical record, not a personal diary, so he kept his temper. But you couldn’t call Winthrop and Dudley bosom buddies, even though his daughter Mary Winthrop married Dudley’s son Samuel.

Holding Anne’s trials at the meetinghouse in New Towne was designed to make her defense more difficult. She had to walk from Boston (where she was staying at Rev. Cotton's home as a semi-prisoner) to the river ferry, and then from the ferry uphill to the meetinghouse, in whatever weather. She had two small children which could have been cared for by other family members, but it’s not easy to stay focused on your trial defense (she wasn’t allowed an attorney) when there are domestic issues to decide. And during both trials, she was on her own. William Hutchinson, William Dyer, and the other Antinomian men were scouting and buying the land for their town and farms when (as they all knew) Anne would be exiled.

It was at or near the end of Anne’s second trial in March 1638 that Mary Dyer took her hand as Anne walked out of the meetinghouse, having been excommunicated and banished. That’s when someone in the crowd outside said that Mary’s miscarriage five months before had been a “monster.”

Boston and Cambridge have changed in countless ways over the last 380 years. Swamps and bays were filled in and islands connected to the mainland. But though roads can be renamed, sometimes the modern streets and highways follow the original path. In my research for my books on Mary Dyer and her associates, I found a paragraph about the neighborhood near Harvard University (see text on the image), that pinpoints the location of the original meetinghouse. Then I went to Google Maps and zoomed in, and there it is. Not the meetinghouse, but the very place where Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer made their dramatic stand of solidarity and defiance. It took extraordinary courage and love for Mary to stand up, alone, before all those severe, frowning ministers and magistrates and take the hand of a woman who’d just been convicted of heresy.

The map pin is stuck where the meetinghouse stood. Click the image to enlarge.

The map pin is stuck where the meetinghouse stood. Click the image to enlarge. Christy K Robinson, the author of this Dyer research blog and three books on William and Mary Barrett Dyer, has been invited to participate in a conference on Anne Hutchinson, held in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York in July 2016. Christy will take her place on a panel discussion, and speak about Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer at Harvard University. (Which, as you may know, is a very big deal!) If the books, blog, and Facebook pages have been a valuable resource to your genealogy and family history, please consider making a gift to enable Christy to attend the conference. You may click this link to learn more:

https://www.gofundme.com/23txdvq8

Christy K Robinson, the author of this Dyer research blog and three books on William and Mary Barrett Dyer, has been invited to participate in a conference on Anne Hutchinson, held in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York in July 2016. Christy will take her place on a panel discussion, and speak about Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer at Harvard University. (Which, as you may know, is a very big deal!) If the books, blog, and Facebook pages have been a valuable resource to your genealogy and family history, please consider making a gift to enable Christy to attend the conference. You may click this link to learn more:

https://www.gofundme.com/23txdvq8

Published on May 27, 2016 00:16

May 18, 2016

Anne Hutchinson: Brief life of Harvard's "midwife" from Harvard Magazine

Your independent source for Harvard news since 1898

Anne Hutchinson

Brief life of Harvard's "midwife": 1595-1643by Peter G. Gomes

The Reverend Peter J. Gomes, B.D. '68, is Plummer professor of Christian morals and Pusey minister in the Memorial Church.

On June 2, 1922, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts received from the Anne Hutchinson Memorial Association and the State Federation of Women's Clubs a bronze statue of Anne Hutchinson. The inscription read in part:

In Memory of Anne Marbury Hutchinson

Courageous Exponent of Civil Liberty

and Religious Toleration It might have added that Mrs. Hutchinson was the mother of New England's first and most serious theological schism (traditionally known as the Antinomian Controversy); that in debate she bested the best of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's male preachers, theologians, and magistrates; and that as a result of her heresy the colony determined to provide for the education of a new generation of ministers and theologians who would secure New England's civil and theological peace against future seditious Mrs. Hutchinsons "when our present ministers shall lie in the dust," as the inscription on the Johnston Gate puts it. Thus, Anne Hutchinson was midwife to what would become Harvard College...

Read the rest of the story at Harvard Magazine , http://harvardmagazine.com/2002/11/anne-hutchinson.html

________________________________

Christy K Robinson, the author of this Dyer research blog and three books on William and Mary Barrett Dyer, has been invited to participate in a conference on Anne Hutchinson, held in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York in July 2016. Christy will take her place on a panel discussion, and speak about Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer at Harvard University. (Which, as you may know, is a very big deal!) If the books, blog, and Facebook pages have been a valuable resource to your genealogy and family history, please consider making a gift to enable Christy to attend the conference. You may click this link to learn more:

https://www.gofundme.com/23txdvq8

Christy K Robinson, the author of this Dyer research blog and three books on William and Mary Barrett Dyer, has been invited to participate in a conference on Anne Hutchinson, held in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York in July 2016. Christy will take her place on a panel discussion, and speak about Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer at Harvard University. (Which, as you may know, is a very big deal!) If the books, blog, and Facebook pages have been a valuable resource to your genealogy and family history, please consider making a gift to enable Christy to attend the conference. You may click this link to learn more:

https://www.gofundme.com/23txdvq8

Published on May 18, 2016 22:43