Doc Searls's Blog, page 21

August 15, 2024

A Better Way to Do News

Twelfth in the News Commons series

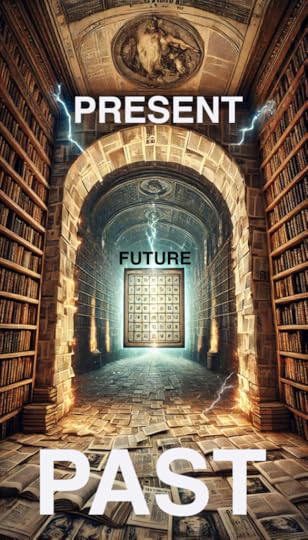

Last week at DWeb Camp, I gave a talk titled The Future, Present, and Past of News—and Why Archives Anchor It All. Here’s a frame from a phone video:

[image error]

DWeb Camp is a wonderful gathering, hosted by the Internet Archive at Camp Navarro in Northern California. The talk was at 9:30am, when it was still just 59°. It hit the 90s later.

In this post I’ll give the same talk, adding some slides and points I didn’t get to my 25-minute window. Here goes.

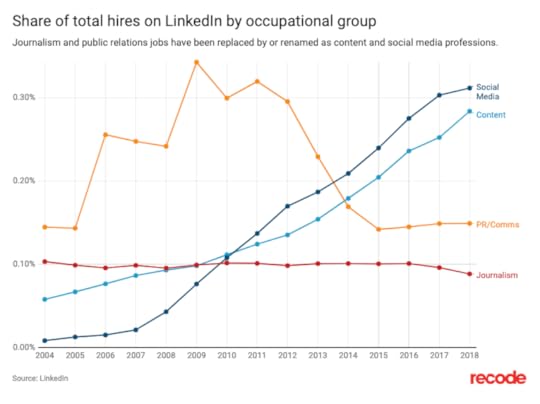

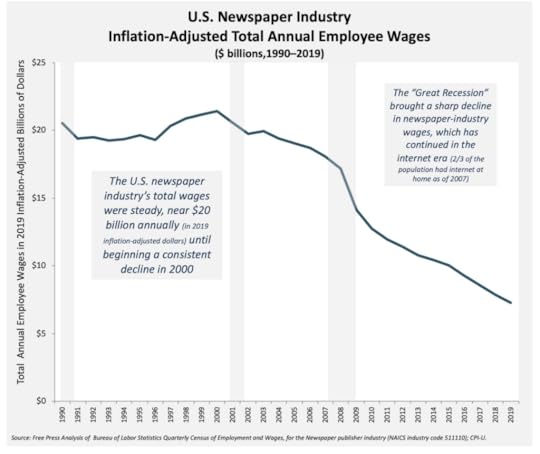

For journalism, news is bad:

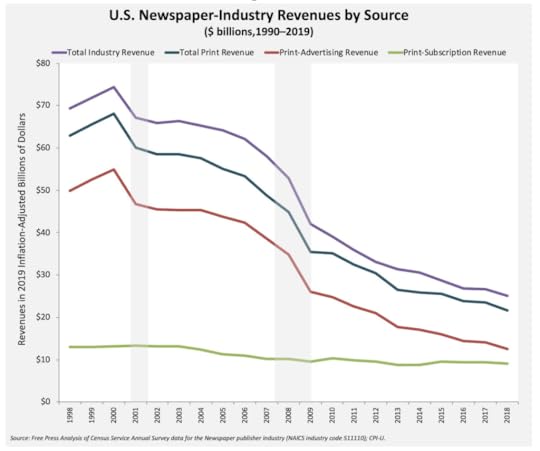

Revenue sources are going away:

Wages suck:

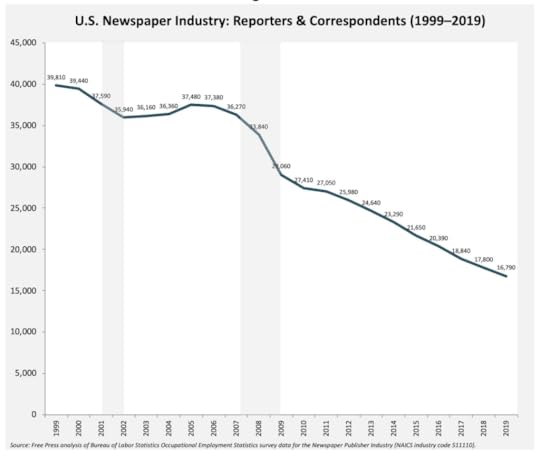

So does employment:

But it’s looking up for bullshit and filler:

So what can we do?

There’s the easy choice—

But bear in mind that,

News only sucks as a big business.

But not as a small one.

For example, here:

Bloomington, Indiana. That’s where my wife and I are living while we serve as visiting scholars with the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University. It’s a great place. (I’ve lived in many college towns, and this is my favorite, for many reasons.)

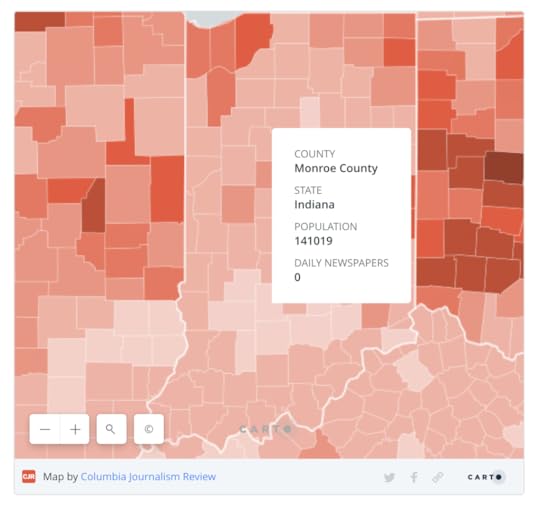

In 2017, Columbia Journalism Review produced an interactive map of America’s “news deserts.” One of them is Monroe County, most of which is Bloomington:

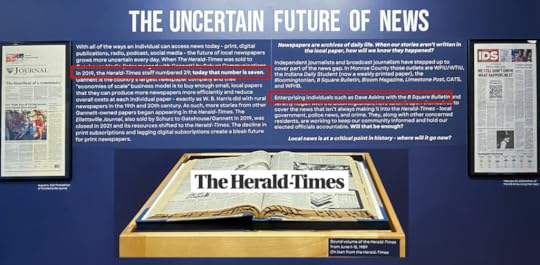

This was in error, because Bloomington did still have a daily paper then: the Herald-Times. And it is still does. The H-T persists in print and online. But, as “Breaking the News: The Past and Uncertain Future of Local Print Journalism” explained last year in a huge and well-curated exhibit at the Monroe County History Center,

the Herald-Times has shrunk quite a bit, while some “enterprising individuals” are taking up the slack—and then some. One they single out is Dave Askins of the B Square Bulletin:

Dave’s beat is city and county government. His “almost daily” newsletter and website are free, but they are also his business, and he makes his living off of voluntary support from his readers. More importantly, Dave has some original, simple, and far-reaching ideas about how local news should work. That’s what I’m here to talk about.

We’ll start with the base format of human interest, and therefore also of journalism: stories.

Right now, as you read this, journalists are being asked the same three words, either by themselves or by their editors:

I was 23 when I got my first job at a newspaper, and quickly learned that there are just three elements to every story:

CharacterProblemMovementThat’s it.

The character can be a person, a ball club, a political party, whoever or whatever. They can be good or bad, few or many. It doesn’t matter, so long as they are interesting.

The problem can involve struggle, conflict, or any challenge—or collection of them—that holds your interest. This is what gets and keeps readers, viewers, and listeners engaged.

The movement needs to be toward resolution, even if it never gets there. (Soap operas never do, but the movement is always there.)

Lose any one of those three and you don’t have a story.

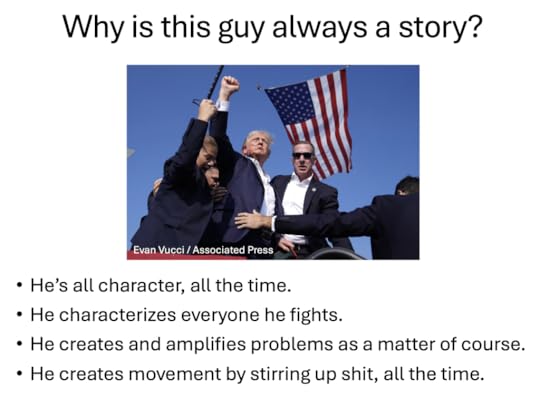

So let’s start with Character. Do you know who this is?

Probably not. (Nobody in the audience at my talk recognized him.)

He’s Pol Pot, who gets bronze medal for genocide, given the number of people he had killed (at 1.5 to 2 million, he comes in behind Hitler and Stalin) and a gold medal for killing the largest percentage of his own country’s population (a quarter or so).* His country was Cambodia, which he and the Khmer Rouge regime rebranded Kampuchea while all the killing was going on, from 1975 to 1979.

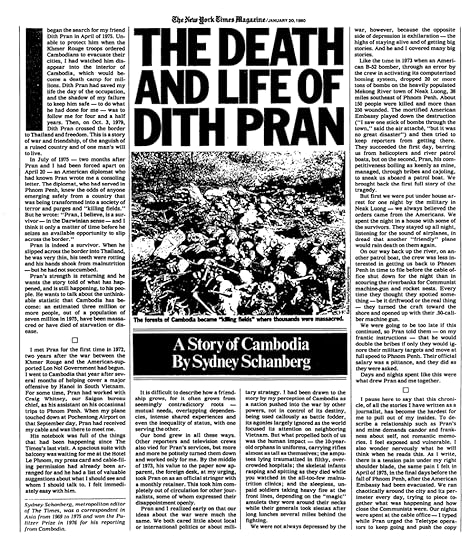

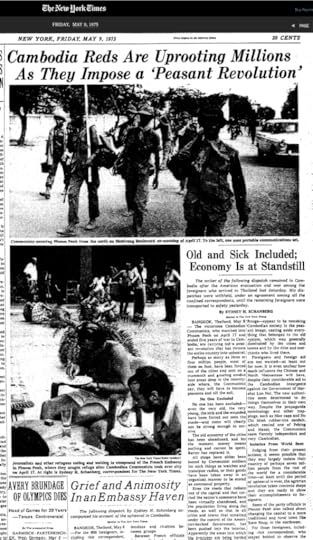

The first we in the West heard much about the situation was in the mid-70s, for example by this piece in the May 9, 1975 edition of The New York Times:

The link here goes to the paper’s TimesMachine archives. Seeing it requires a subscription. We’ll discuss this more below.

The link here goes to the paper’s TimesMachine archives. Seeing it requires a subscription. We’ll discuss this more below.It’s a front-page story by Sydney Shanberg, who himself becomes a character later (as we’ll see).

The first we (or at least I) heard about the genocide was sometime in 1976 or ’77, while watching Hughes Rudd on the CBS Morning News. He said something like this:

[image error]

Wierdly, it wasn’t the top story. It was like, “All these people died, back after this.”

So I went to town (Chapel Hill at the time) and bought a New York Times. There was … something small on an inner page, as I recall. (I’ve dug a lot but still haven’t found it.)

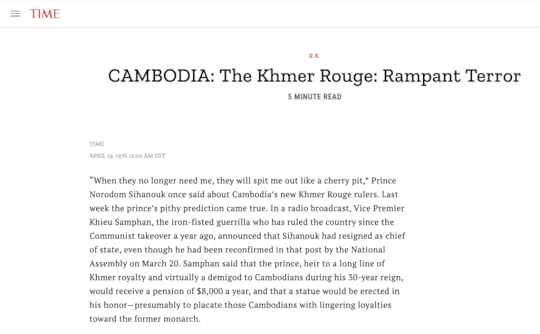

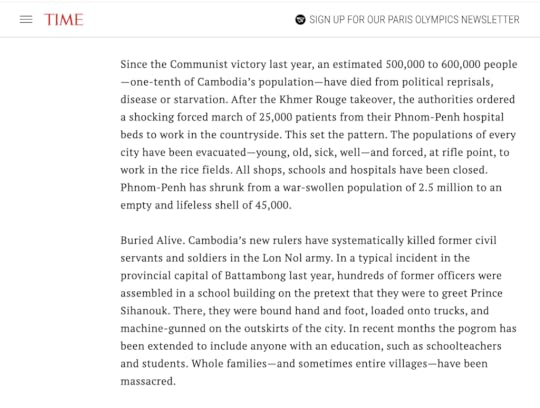

But Time, the weekly news magazine, did cover at least the beginning of the genocide, in the April 19, 1976 issue. (By the way, all hail to Time for its open archives. This is a saving grace I’ll talk about later, and much appreciated.) Here is how that story begins:

Note how Prince Norodom Sihanoouk stars in the opening sentence. He’s there because he was a huge character. (Go read about him. He was a huge piece of work, but not a bad one.) Pol Pot doesn’t appear at all. And the number of dead doesn’t show up until the second paragraph:

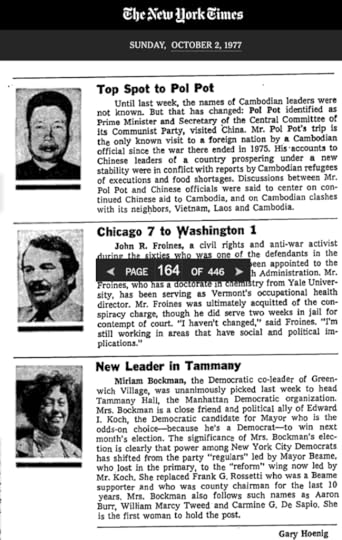

Coverage of Cambodia in the late ’70s remained sparse, considering the death count. Pol Pot didn’t show up in the Times until this was posted on page 164 of 446 in the massive Sunday paper on October 7, 1977:

The Times‘ most serious coverage of Cambodia was in opinion pieces. For example, an editorial titled The Unreachable Terror in Cambodia ran on July 3, 1978, and mentions Pol Pot in the third paragraph. Holocaust II!, by Florence Graves, ran on Page 210 of the November 26, 1978 Sunday Magazine. It begins, “They don’t talk about extermination ovens or about freaky medical experiments or about lampshades fashioned from human skin. But the Cambodian refugees do talk about forced labor camps, about “deportations,” and about mass executions.” Later she adds, “It’s a horror story which, for the most part, has gone unreported in the American press.”

It wasn’t reported because it wasn’t a story. Why:

No character of any interest (besides the deposed prince).A problem that was gigantic but not of much interest otherwise. At least not outside the region.Not much movement aside from a torrent of refugees into Thailand.Then came this, in January 1980:

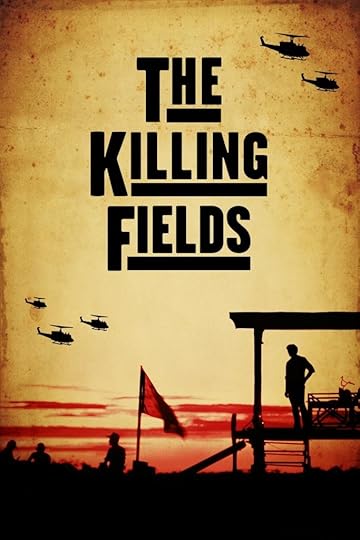

In the opening paragraph, Sydney Schamberg writes, “This is a story of war and friendship, of the anguish of a ruined country and of one man’s will to live.” As human stories about genocides go, the only one that might top Dith Pran‘s is Anne Frank‘s. The new story was so compelling that four years later it became a huge movie:

And the Cambodian genocide has had plenty of coverage ever since. One guy’s story made all the difference. One guy.

Now let’s go closer to home:

Trump is a genius at all that stuff. And he keeps his ball rolling by making shit up constantly. You’re a lot more free to tell stories—and to move them along—if facts don’t matter to you. Here’s how I put it in Stories vs. Facts:

Here are another three words you need to know, because they pose an extreme challenge for journalism in an age when stories abound and sources are mostly tribal, meaning their stories are about their own chosen heroes, villains, and the problems that connect them: Facts don’t matter.

Daniel Kahneman says that. So does Scott Adams.

Kahneman says facts don’t matter because people’s minds are already made up about most things, and what their minds are made up about are stories. People already like, dislike, or actively don’t care about the characters involved, and they have well-formed opinions about whatever the problems are.

Adams puts it more simply: “What matters is how much we hate the person talking.” In other words, people have stories about whoever they hate. Or at least dislike. And a hero (or few) on their side.

These days we like to call stories “narratives.” Whenever you hear somebody talk about “controlling the narrative,” they’re not talking about facts. They want to shape or tell stories that may have nothing to do with facts.

But let’s say you’re a decision-maker: the lead character in a personal story about getting a job done. You’re the captain of a ship, the mayor of a town, a general on a battlefield, the detective on a case. What do you need most? Somebody’s narrative? Or facts?

Depends on what you need. Donald Trump needs to win an election. He’ll do that with stories, just like he always has. As characters go, Kamala Harris is a much tougher opponent than Joe Biden was, because she’s harder for Trump to characterize, and she has plenty of character on her own. And both make good stories because they’re in a fight against each other.

Things are different in places like Bloomington, where people live and work in the real world.

In the real world, there are potholes, homeless encampments, storms, and other problems only people can solve—or prevent—preferably by working together. In places like that, what should journalists do, preferably together?

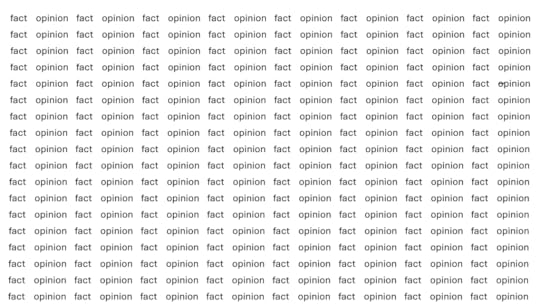

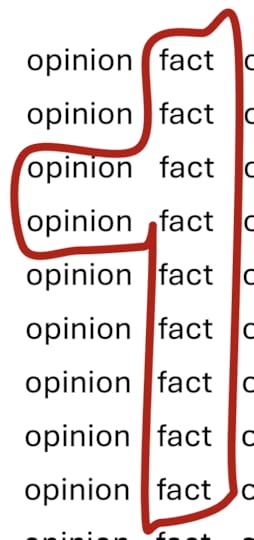

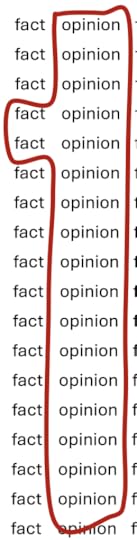

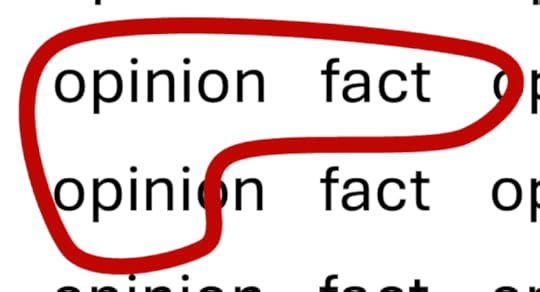

To clarify the options, look at journalism’s choice of sources and options for expression. Put simply, you’ve got facts and opinions. A typical story has a collection of facts, and some professor or other authoritative source provides a useful opinion about those facts. Sometimes both come from the same place, such as the National Weather Service. So let’s look at different approaches to news against this background:

Here is roughly what you’ll get from serious and well-staffed news organizations such as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the BBC, and NPR:

Mostly facts, but some opinions, typically in columns and on pages for that purpose.

How about research centers that publish studies and are often sourced by news organizations? Talking here about Pew, Shorenstein, Brookings, Rand. How do they sort out? Here’s a stab:

Lots of facts, plus one official opinion derived from facts. Sure, there are exceptions, but that’s a rough ratio.

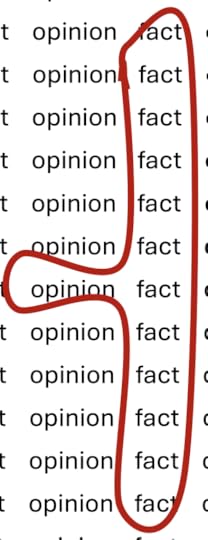

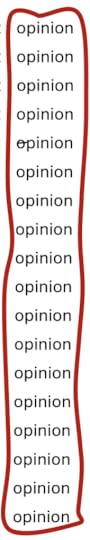

How about cable news networks: CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and their wannabes? Those look like this:

These networks are mostly made of character-driven shows. They may be fact-based to some degree, but their product is mostly opinion. Facts are filtered out through on-screen performers.

Talk radio of the political kind is almost all opinion:

Yes, facts are involved, but as Scott Adams says, facts don’t matter. What matters are partisan opinions.

Sports talk is different. It’s chock full of facts, but with lots of opinions as well:

Blogs like the one you’re reading? Well…

In a general way, that’s what you get.

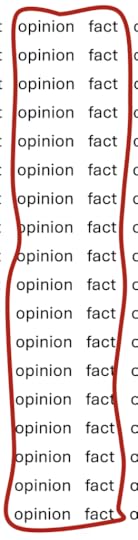

Finally, there’s Dave Askins. Here’s what he gives you in the B Square Bulletin:

[image error]

Dave is about facts. And that’s at the heart of his plan for making local journalism a model for every other kind of journalism that cares about being fully useful and not just telling stories all the time. One source he consulted for this plan is Bloomington mayor Kerry Thompson. When Dave asked her what might appeal about his approach, she said this:

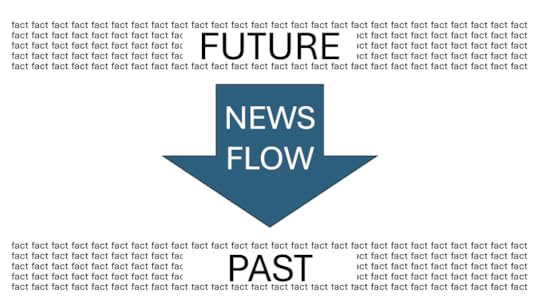

Dave sees facts flowing from the future to the past, like this:

The same goes for lots of other work, such as business, scholarship, and running your life. But we’re talking about local journalism here. For that, Dave sees the flow going like this:

[image error]

Calendars tell journalists what’s coming up, and archives are where facts go after they’ve been plans or events, whether or not they’ve been the subjects of story-telling. That way decision-makers, whether they be journalists, city officials, or citizens, won’t have to rely on stories alone—or worse: their memory, or hearsay.

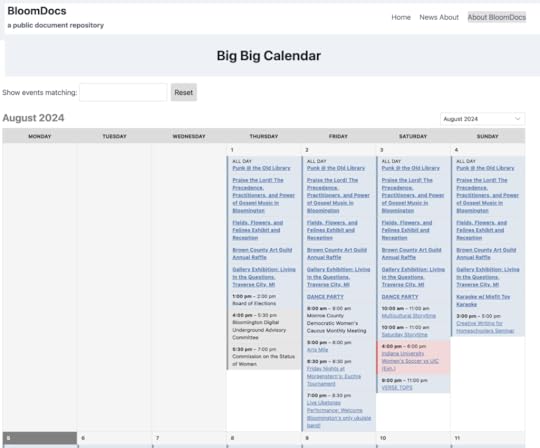

Dave has started work on both the future and the past, starting with calendars. On the B Square Bulletin, he has what’s called the Big Big Calendar. Here is how this month started:

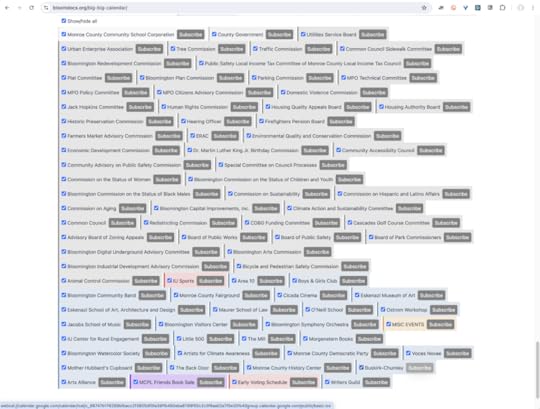

And here are the sources:

Every outfit Dave can find in the county that publishes a calendar and also has a feed is in there. They don’t need to do any more work than that. I suspect most don’t even know they syndicate their calendars automatically.

On the archive side, Dave has BloomDocs, which he explains this way on the About page:

BloomDocs is a public document repository. Anyone can upload a file. Anyone can look at the files that have been uploaded. That’s it.

What use is such a thing?

For Journalists: Journalists can upload original source files (contracts, court filings, responses to records requests, ordinances, resolutions, datasets) to BloomDocs so that they can link readers directly to the source material.

For Residents: Residents who have a public document they’d like to make available to the rest of the world can upload it to BloomDocs. It could be the government’s response to a records request. It could be a slide deck a resident has created for a presentation to the city council.

For Elected Officials: Elected officials who don’t have government website privileges and do not maintain their own websites can upload files to BloomDocs as a service to their constituents.

For Government Staff: Public servants who have a document they would like to disseminate to the public, but don’t have a handy place to post it on an official government website, or if they want a redundant place to post it, can upload the file to BloomDocs.

A future vision: “Look for it on BloomDocs” is a common answer to the question: Where can I get a copy of that document?

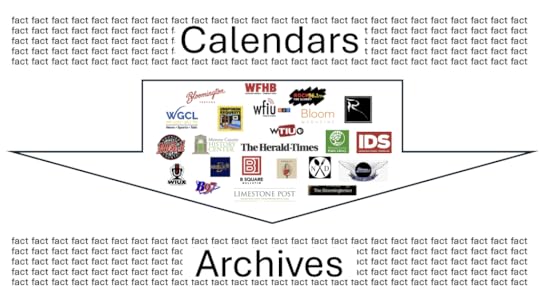

Dave also doesn’t see this as a solo effort. He (and we, at the Ostrom Workshop, who study such things) want this to be part of the News Commons I’ve been writing about here (this is the 12th post in the series). In that commons, the flow would look like this:

All the publishers, radio and TV stations, city and county institutions, podcasts, and blogs I show there (and visit in We Need Wide News and We Need Whole News) should have their own arrows that go from Future to Past, and from Calendars to Archives. And when news events happen, which they do all the time, and not on a schedule, those should flow into archives as well. We need to normalize those as much as we can.

Which brings us to money. What do we need to fund here?

Let’s start with the calendar. Dave’s big idea here is DatePress, which he details at that link. DatePress would be something WordPress might do, or somebody might do with WordPress (the base code of which is open source). I’m writing on WordPress right now. Dave publishes the B Square on WordPress. I’ll bet that the websites for most of the entities above are on it too. It’s the world’s dominant CMS (content management system). See the stats here and here.

On the archiving side, BloomDocs is a place to upload and search files, of which there are hundreds so far. But to work as a complete and growing archive, BloomDocs needs its own robust CMS, also based on open source. There are a variety of choices here, but making those happen will take work, and that will require funding. Archives, being open, should also be backed up at the Internet Archive as well.

Which brings us to money.

There are several possibilities, starting with funding Dave’s work so he can add functions and not do all of this himself.

Here are two aother ideas that aren’t the usual (advertising, subscriptions, subsidy).

The first is to drop the long-standing newspaper practice of locking up archives behind paywalls. (In Bloomington this would apply only to the Herald-Times). The new practice would be to charge for the news (if you like), but give away the olds. In other words, stop charging for access to archives. Be like Time and not the Times and nearly every other paper. (I first brought this up here in 2007.)

The second is to make EmancPay happen.

EmanciPay is an idea we cooked up in ProjectVRM at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center in 2009. Here’s how the description begins:

Simply put, Emancipay makes it easy for anybody to pay (or offer to pay) —

as much as they likehowever they likefor whatever they likeon their own terms— or at least to start with that full set of options, and to work out differences with sellers easily and with minimal friction.

Emancipay turns consumers (aka users) into customers by giving them a pricing gun (something which in the past only sellers used) and their own means to make offers, to pay outright, and to escrow the intention to pay when price and other requirements are met. And to be able to do this at scale across all sellers, much as cash, browsers, credit cards and email clients do the same. Payments themselves can also be escrowed.

In slightly more technical terms, EmanciPay is a payment framework for customers operating with full agency in the open marketplace, and at scale. It operates on open protocols and standards, so it can be used by any buyer, seller or intermediary.

It was conceived as a way to pay for music, journalism, or what any artist brings into the world. But it can apply to anything. For example, [subscriptions], which have become a giant fecosystem in which every seller has separate and non-substitutable scale across all subscribers, while subscribers have zero scale across all sellers, with the highly conditional exceptions of silo’d commercial intermediaries. As [Customer Commons] puts it,

There’s also not much help coming from the subscription management services we have on our side: Truebill, Bobby, Money Dashboard, Mint, Subscript Me, BillTracker Pro, Trim, Subby, Card Due, Sift, SubMan, and Subscript Me. Nor from the subscription management systems offered by Paypal, Amazon, Apple or Google (e.g. with Google Sheets and Google Doc templates). All of them are too narrow, too closed and exclusive, too exposed to the surveillance imperatives of corporate giants, and too vested in the status quo.

That status quo sucks (see here, or just look up “subscription hell”), and it’s way past time to unscrew it.) But how?

The better question is where?

The answer to that is on our side: the customer’s side.

While EmanciPay was first conceived by ProjectVRM as a way to make live payments to nonprofits and to provide a new monetization method for publishers. it also works as a counterpart to sellers’ subscription systems in what Zuora (a supplier of subscription management systems to the publishing industry, including The Guardian and Financial Times) calls the “subscription economy“, which it says “is built on ever changing relationships with your customers”. Since relationships are two-way by nature, EmanciPay is one way that customers can manage their end, while publisher-side systems such as Zuora’s manage the other.

More sources:

An Easy Way to Pay for Journalism, Music, and Everything Else We LikeAn Immodest Proposal for the Music IndustryA citizen-sovereign way to pay for news — or for any creative workThe New News BuisnessFar as I know, all the ideas you just read about are original, or close enough.

Let’s make them happen.

*Based on estimates. Nobody knows for sure. Here’s Wikipedia.

ChatGPT app for Mac

So I went to the ChatGPT website to ask a question and got hit with a popover promo for the new Mac app version. So I got it. Here is the dialog that followed my first question (which is boring, so we’ll skip it), copied over from the ChatGPT website, where I went after this frustrating encounter:

Can I move my chat history from the web to here?

ChatGPT said:Unfortunately, there’s no direct way to move chat history from one platform to another. However, if there’s specific information or conversations you’d like to continue or reference, you can copy and paste the relevant parts here, and we can pick up from there! If there’s anything specific you want to discuss or continue from a past conversation, just let me know.

You said:where here is my chat history?ChatGPT said:Your chat history here is session-based, meaning it exists only for the duration of our current conversation. Once the session ends, the chat history isn’t saved. However, I can remember key details or preferences across sessions if you want, and you can also start fresh conversations at any time.

If there’s something specific you want to continue discussing from a previous session, you might want to copy and paste that information here.

You said:That’s useless. Thanks anyway.ChatGPT said:I understand that can be frustrating. If you need any help or want to continue discussing something specific, I’m here to assist. Just let me know!

You said:I’m paying OpenAI for ChatGPT. I would hope that the app would offer advantages over the Web page.ChatGPT saidI can see why you’d expect some added benefits from the app version. While the app and web versions of ChatGPT share many of the same core functionalities, the app offers convenience for on-the-go use, such as notifications and a more optimized interface for mobile devices. However, both platforms currently have similar features in terms of chat history and session management.

If you have suggestions or feedback on features you’d like to see, sharing that with OpenAI could be helpful. They are continually improving the platform, and user feedback is a big part of that process.

Is there anything specific you’d like to see improved or added to the app?

You said:Yes. chat history.ChatGPT said:Your request for chat history is completely understandable, especially for those who want to revisit previous conversations, continue complex discussions, or reference past information. While I can’t implement that feature directly, your feedback is valuable.

I’d recommend sharing this feedback directly with OpenAI through their official channels or within the app’s feedback options. They often use user feedback to prioritize new features and improvements, so expressing your need for chat history could help influence future updates.

If there’s anything else on your mind or another way I can assist, feel free to let me know!

You said:Can I copy this whole dialog and save it as text?ChatGPT said:Yes, you can easily copy the entire dialog and save it as a text file. Here’s how you can do it:

Select the Text: Click and drag your cursor to highlight the entire conversation.Copy the Text: Right-click on the highlighted text and select “Copy,” or press Ctrl + C (Windows) or Command + C (Mac).Paste the Text: Open a text editor like Notepad (Windows) or TextEdit (Mac), then paste the copied text by right-clicking and selecting “Paste,” or by pressing Ctrl + V (Windows) or Command + V (Mac).Save the File: Once the text is pasted, you can save the file by going to “File” > “Save As,” then choose your desired location and file name.This will allow you to keep a record of the conversation for future reference.

You said:It only works for the latest answer.ChatGPT said:If you’re experiencing issues with selecting and copying the entire conversation at once, here’s a workaround:

Use the Browser’s “Select All” Feature:On the web or in an app, try pressing Ctrl + A (Windows) or Command + A (Mac) to select all the text on the screen. This should highlight the entire conversation.Then, press Ctrl + C (Windows) or Command + C (Mac) to copy the highlighted text.Copy in Sections:If the “Select All” method doesn’t work, you might need to scroll up and copy the conversation in smaller sections.Highlight a section of the conversation, copy it, and paste it into your text editor. Then, repeat the process for the remaining sections.Browser Extension:If you’re using a browser, certain extensions or tools like “Evernote Web Clipper” or “Simplified Notepad” might allow you to clip the entire webpage or copy all text for easier saving.Let me know if you encounter any issues, and I can try to guide you further!

You said:It still only works for the latest answer.

ChatGPT said:

If you’re only able to copy the latest answer, this might be due to the way the chat interface is designed, especially in some apps or browsers. Here’s an alternative approach you can try:

1. Screenshot the Conversation:If you can’t copy the text directly, you can take screenshots of the conversation. Most devices allow you to take a screenshot by pressing specific keys:Windows: Press Windows Key + Shift + S to select an area to screenshot.Mac: Press Command + Shift + 4 to select an area to screenshot.iOS/Android: Use the physical buttons on your device to take a screenshot.You can then save these screenshots as images for future reference.2. Use the Browser’s “Print” Feature:If you’re on a browser, you can try printing the page to a PDF, which will capture the entire conversation.On your browser, press Ctrl + P (Windows) or Command + P (Mac) to open the print dialog.Choose “Save as PDF” instead of printing, and this will create a PDF file of the entire chat.3. Use Developer Tools (Advanced Method):For advanced users: In a browser, you can open the developer tools (F12 or Ctrl + Shift + I on most browsers), inspect the elements of the conversation, and manually extract the text from there. However, this is a more technical solution.If these methods don’t work or you have further issues, let me know, and we can explore other options!

The UI is a small fixed-size window (like those chat windows you see on service sites), so screenshooting made no sense. And the other two options weren’t worth trying.

But when I went to ChatGPT on the Web, there was my history outlined in the left panel:

The top one was the dialog I just had, displayed in the Web interface. The app could have @#$%^ told me that was a feature.

But it didn’t, because it’s lame. So far.

August 6, 2024

Setting the terms, redux

I wrote for Linux Journal from 1996 to 2019, the final years as editor-in-chief. After ownership changed and the whole staff turned over, the new owner, Slashdot Media, agreed to keep the server up so nothing would be 404’d. I am grateful that they have kept that promise. I should add, however, that some of the archive seems to be missing—or so I assume because keyword searches on Google, Bing, and the site itself fail to bring up some items. Fortunately, I have an archive of my own writing for the magazine—or at least of the final drafts I submitted. Since the cadence of this blog has fallen off a bit, I think a good way to fill open spaces in time is to re-publish columns I wrote for Linux Journal when Linux was still an underpenguin and the open source movement was still new, growing, and a threat to the likes of Microsoft. (Which has since flipped its stance. We’re well past GandiCon 4 now.*) This piece is one example: a small hunk of history that bears re-telling. (And forgive the rotted links, because, alas, the Web is a whiteboard.)

Linux For Suits

Linux For SuitsAugust 2001

Setting the terms>Back in May, Craig Mundie, Senior Vice President with Microsoft, gave a speech at NYU’s Stern School of Business that announced the terms by which Microsoft was cracking open — barely — its source code. He called the company’s new licensing model “shared source.” (I just wrote “scared source” by mistake, which tells you where my mind is going.)

The fact that Microsoft would start rapping about any kind of source code, and modify it with a fresh new euphemism — shared — caused immediate tissue rejection in the hacker cultural body. Leading hackers so certain of their own Truth that they refuse to appear on each other’s t-shirts were suddenly gathered around their collective keyboards to craft a single response that would say, in polite terms, “Embrace and extend this, dude.”

The result was an open letter published on Bruce Perens’ site (Perens.com), and signed by Bruce and a quotariat of free software and open source luminaries: Richard Stallman, Eric S. Raymond, Guido Van Rossum, Tim O’Reilly, Larry Augustin, Bob Young, Larry Wall, Miguel de Icaza and Linus Torvalds. (An anonymous coward on Slashdot wrote, “It’s like a human Beowulf cluster!”) While critical and challenging to Microsoft, its bottom line was inviting:

We urge Microsoft to go the rest of the way in embracing the Open Source software development paradigm. Stop asking for one-way sharing, and accept the responsibility to share and share alike that comes with the benefits of Open Source. Acknowledge that it is compatible with business.

Free Software is a great way to build a common foundation of software that encourages innovation and fair competition. Microsoft, it’s time for you to join us.

Mundie responded with a piece in CNET that framed his argument in terms of economics, manufacture and the PC’s popularity:

… this is more than just an academic debate. The commercial software industry is a significant driver of our global economy. It employs 1.35 million people and produces $175 billion in worldwide revenues annually (sources: BSA, IDC).

The business model for commercial software has a proven track record and is a key engine of economic growth for many countries. It has boosted productivity and efficiency in almost every sector of the economy, as businesses and individuals have enjoyed the wealth of tools, information and other activities made possible in the PC era.

Then he took on the GPL — the Free Software Foundation’s General Public License:

In my speech, I did not question the right of the open-source software model to compete in the marketplace. The issue at hand is choice; companies and individuals should be able to choose either model, and we support this right. I did call out what I believe is a real problem in the licensing model that many open-source software products employ: the General Public License.

The GPL turns our existing concepts of intellectual property rights on their heads. Some of the tension I see between the GPL and strong business models is by design, and some of it is caused simply because there remains a high level of legal uncertainty around the GPL– uncertainty that translates into business risk.

In my opinion, the GPL is intended to build a strong software community at the expense of a strong commercial software business model. That’s why Linus Torvalds said last week that “Linux is never really going to be a rich sell.”

This isn’t to say that some companies won’t find a business plan that can make money releasing products under the GPL. We have yet to see such companies emerge, but perhaps some will.

He added,

What is at issue with the GPL? In a nutshell, it debases the currency of the ideas and labor that transform great ideas into great products.

It would be easy to dismiss all this as provocation in the voice of boilerplate — or worse, as what one überhacker called “a declaration of war on our culture.” But neither of those responses are useful to folks caught in the middle — the IT professionals this column calls “suits.”

As it happened Eric Raymond and I were both guests on the May 14 broadcast of The Linux Show. When conversation came around to the reasoning behind open source rhetoric, Eric said, “We used the term open source not to piss off the FSF folks, but to claim a semantic space where we could talk about issues without scaring away the people whose beliefs we wanted to change.”

This has been an extremely successful strategy. Even if IT folks don’t agree about what “open source” means, it’s still a popular topic. Everybody who talks about open source inhabits its semantic space. But conversing is not believing. Remember Eric’s last seven words. These are still people whose beliefs we want to change.

Changing other people’s beliefs isn’t like changing your shoes. It’s like changing other people’s shoes. There’s a lot of convincing to do. Even if the other guy’s shoes are ugly and uncomfortable, at least they’re familiar. And in this case, familiar doesn’t cover it. In the IT world, Microsoft platforms, software and tools are the prevailing environment. Of course, we used to say the same thing about IBM. Things do change.

Did anything change when Craig Mundie tried to embrace and extend the conversation about source code? I think so. Mundie’s response to Bruce’s letter looked like a poker move to me. He said, “We’ll see your source and raise you one shared“. What was our response? As a unit, nothing. the Beowulf Cluster broke up over the usual disagreements. It wasn’t pretty.

Perhaps it’s just as well. Two of the original signers told me they felt the letter was skewed “from the pragmatic to the ideological.” If so, Mundie read the letter well, because the ideology is exactly what his response attacked.

When this kind of thing happens, is the right choice to attack back?

We need to be careful here. When Microsoft decided to release a free browser, Marc Andreessen said “In a fight between a bear and an alligator, what determines the victor is the terrain. What Microsoft just did was move into our terrain.” He also called the operating system “just a device driver.” Today Microsoft is wearing alligator shoes.

And now the bear sits in our semantic space, talking business trash.

You might recall what I wrote exactly a year ago, when every mainstream publication was running stories about how the feds were going to break up Microsoft. I said Microsoft was going to beat the rap by baiting Judge Jackson, giving the company a winnable case in Appeals Court that it lacked in Judge Jackson’s.

So: are they baiting us here? You betcha. But the appeals court in this case is the whole IT community that remains Microsoft’s customer base.

What they want us to do is defend the incomprehensible: namely, all the stuff we can’t stop arguing about.

The tactical picture becomes clear when you look at this diagram from the Free Software Foundation’s philosophy page. From the perspective of both Microsoft and its customers, the one thing that’s easy to understand is in the upper right. By aiming insults at the GPL in the lower left, they rally everybody in the Free/Open communities to defend what those outside those communities have the most trouble understanding: the FSF’s belief that owning software is a Bad Thing.

If we defend that position or respond by using “proprietary” as an epithet, we’ll lose. “It takes two to tango,” one commercial developer wrote to me in the midst of all this. “If Microsoft ever chose an enemy who was willing to share the cursor, they would finally have met their match. It hasn’t happened yet. Your friends are still saying ‘It’s All About Us’ which is complete bullshit. They never talk about anyone but Microsoft and themselves.”

Which is why we need to embrace and extend the most precious thing that Microsoft has and we don’t, which is customers. Why? Because it’s their hearts and minds we need to win, and Microsoft is busy ignoring them.

Look back at Mundie’s text. Note that his point of view is located not with customers, but with the commercial software industry. Big difference. Yes, commercial software companies do face a choice among many different business models and licensing schemes, including the GPL. But this argument isn’t just about business models. It is not the exclusive concern of Supply. It’s also about Demand. In some ways the real argument isn’t between Supply and Supply: one “shared” and one “open”. It’s between Supply and Demand.

On the demand side, customers are using software of many different types, from many different sources. Whether they know it or not, most large enterprises are already full of applications and development tools from the free software and open source communities. Are they choosing those “solutions” just because they like one party’s source license or another party’s business model? No. They’re using it because it’s available and practical.

We need to relocate our concerns to the demand side of markets. What is it that works, and why? Specifically, what “solutions” work for everybody? Our best example, our ace in the hole, isn’t Linux alone. It’s the Net and all the free and open software that accounts for its ubiquity. Our communities created and proliferated that software because we know something about its nature that the Microsofts of the world do not.

The “licensing structures” Microsoft cares most about all rely on conceiving code as capital: as a manufactured good. Concepts like “intellectual property” are easy to understand and argue about as long as one continues to conceive of that property in material terms. But code is not material, and no amount of lawmaking or marketing can make it material.

The deepest fact in this matter is not that software wants to be free, but that code wants to be public. Meanwhile, too many of our laws and business practices cannot comprehend this simple fact. It’s too far below their immediate concerns. Like the core of the Earth, it’s nice to have but too deep to appreciate.

The problem for Microsoft is that it lives in a world increasingly built with public code that oozes like lava out of the free and open ground below everybody. We’re making a whole new world here, but we’re doing it together. And that includes Microsoft, which in fact does contribute to common infrastructure. SOAP is a good example.

Indeed, much good has been produced by what Mundie calls the “commercial software model” or it wouldn’t have customers. But the Net on which all of business increasingly relies is not a product of that model, even though business is certainly involved.

What free/open hackers know and Craig Mundie doesn’t (yet), is that there is much to the nature of code that can neither be comprehended nor represented by the conceptual system Mundie employs — not because it’s insufficient in scope but rather because it’s operating only at the commercial level. At a deeper level — the nature of software itself — the principles of business don’t apply, for the same reason that the principles of mechanics don’t apply to chemistry, even while mechanics depends on chemistry as a deeper principle. You’d rather make a clock out of iron than sodium.

Business needs more of that public infrastructure. It needs programs, operating systems, device drivers, file formats and protocols that everybody can use because nobody owns them. So do commercial developers and their customers: all of Supply and all of Demand. But those terms are too abstract. Think of the entire mess as a bazaar.

If we embrace the whole software bazaar, we can open hearts and extend minds. If we refuse to share the cursor, we cease to represent the bazaar. At that point the choice is between a cathedral and a cult.

Links:

Mundie’s speech: <http://www.microsoft.com/presspass/exec/craig/05-03sharedsource.asp>

Perens’ response: <http://www.perens.com/Articles/StandTogether.html>

Mundie”s response: <http://www.internetnews.com/intl-news/article/0,,6_766141,00.html>

June 30, 2024

The Future, Present, and Past of News

Eleventh in the News Commons series.

all experience is an arch wherethro’

Gleams that untravell’d world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in Ulysses

News flows. It starts with what’s coming up, goes through what’s happening, and ends up as what’s kept—if it’s lucky.

Facts take the same route. But, since lots of facts don’t fit stories about what’s happening, they aren’t always kept, even if they will prove useful in the future. (For more on that, see Stories vs. Facts.)

But we need to keep both stories and facts, and not just for journalists. Researchers and decision-makers of all kinds need all they can get of both.

That’s why a news commons needs to take care of everything from what’s coming up through what’s happened, plus all the relevant facts, whether or not they’ve shown up in published stories. We won’t get deep, wide, or whole news if we don’t facilitate the whole flow of news and facts from the future to the past.

Let’s call this the Tennyson model, after Lord Alfred’s Ulysses, excerpted above. In this model, the future is a calendar such as the one in DatePress. The present is is news reporting. The past is archives.

Calendars are easy to make. They are also easy to feed into other calendars. For example, take the Basic Government Calendar, of Bloomington, Indiana. That one is built from 50+ other calendars (to which it subscribes—and so can you). The Big Big Calendar (be patient: it takes a while to load) covers many other journalistic beats besides government (the beat of the B Square Bulletin, which publishes both).

We describe approaches to archives in The Online Local Chronicle and Archives as Commons. Here in Bloomington, we have two examples already with BloomDocs.org and The Bloomington Chronicle. Both are by Dave Askins of the B Square Bulletin using open-source code. And both are new.

Relatively speaking, Bloomington is a news oasis (see our list of media life forms in Wide News) in a world where news deserts are spreading. So we’ve got a lot to work with. If you want to help with any of it, let me know.

The Personal Internet

—is not this:

A netizen isn’t just an account-holder

A netizen isn’t just an account-holderBy now we take it for granted.

To live your digital life on the Internet, you need accounts. Lots of them.

You need one for every website that provides a service, plus your Mac or Windows computers, your Apple or Google-based phones, your home and mobile ISPs. Sure, you can use a Linux-based PC or phone, but nearly all the services you access will still require an account.

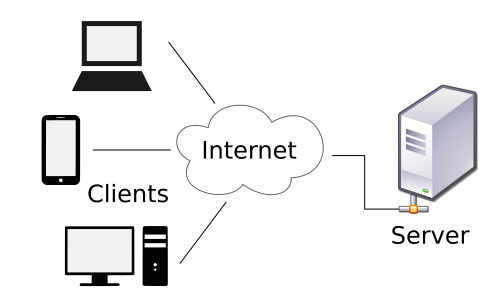

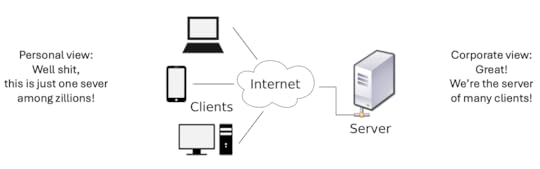

Everything that requires an account has a lock on you—for their convenience. They don’t know any other way. That’s because all the services we use in the online world operate inside a model called client-server, which looks like this:

This is great for the server operator, but not for the rest of us:

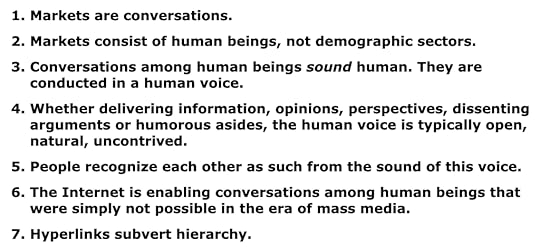

This was not the promise of the Internet described by John Perry Barlow in Death From Above in 1995 and A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace in 1996. Nor was it what Chris Locke, Rick Levine, David Weinberger, and I said in The Cluetain Manifesto‘s ‘one clue’—

—and in the 95 Theses that followed, starting with these:

Since I’ve often heard that an unintended consequence of Cluetrain was causing social media in some way, I just asked ChatGPT and Perplexity the same question: Did The Cluetrain Manifesto help start social media? The answers were roughly the same, but Perplexity provides sources, so I’ll quote that answer:

The Cluetrain Manifesto did not directly start social media, but it did play a significant role in predicting and shaping the philosophy behind social media marketing and online communication. Published in 1999, the manifesto anticipated many of the changes that would occur with the rise of social media and online conversations. (link) (link)

Key points about The Cluetrain Manifesto’s influence on social media:

Predicted global conversations: The manifesto accurately foresaw that the internet would enable powerful global conversations, allowing people to share knowledge rapidly (link).Emphasized authentic communication: It stressed the importance of companies engaging in genuine, human conversations with customers, which became a cornerstone of social media marketing (link) (link).Highlighted networked markets: The manifesto recognized that customers were becoming more connected and influential through online networks, a concept that social media platforms later embodied (link).Challenged traditional marketing: It criticized the “homogenized voice” of traditional business communication, encouraging a more authentic and conversational approach that social media later facilitated (link).Empowered employees: The manifesto suggested that companies should empower employees to engage with customers, an idea that became crucial in social media strategies (link).Recognized the shift in power: It predicted that customers would gain more influence over companies through online conversations, which social media platforms later enabled (link).While The Cluetrain Manifesto didn’t create social media technologies, it provided a philosophical foundation that aligned closely with how social media would eventually function. Its ideas about authentic communication, networked conversations, and customer empowerment became central to social media marketing strategies and practices (link) (link) (link).

Alas, we all still are seats, eyeballs, end users, and consumers, and our reach still does not exceed corporate, government, and organizational grasp, because all of those entities operate their services on the client-server model. And, so long as nearly everyone believes that client-server is the only way to go, the fact that the Internet is end-to-end beneath everything done on it remains irrelevant. Nothing in any of these (and many other) efforts before and since has done anything to change the damned Internet of Accounts:

The Rise of the Stupid Network (by David Isenberg) in 1997The Cluetrain Manifesto in book form, in 2000 and in a 10th Aniversary version (with seven new chapters) in 2010World of Ends (by David Weinberger and me) in 2003Internet Identity Workshop (by Phil Windley, Kaliya Young, and me) since 2005ProjectVRM (by hundreds of people and projects) since 2006 The Intention Economy , a book by me in 2012New Clues (by David Weinberger and me) in 2015I do, however, see hope coming from three angles.

First is self-sovereign identity, or SSI. I’ve written about SSI in many ways and places over the years, but perhaps the best is New Hope for Digital Identity, published in Linux Journal back in 2017. What SSI wishes to replace is the familiar client-server model in which you are the account holder, and two servers are the “identity provider” and the “relying party.” With this system, your “ID” is what you get from the identity provider and their server. With SSI, you have a collection of verifiable credentials issued by the DMV, your church, your school, a performance venue, whatever. They get verified by an independent party in a trustworthy way. You’re not just a client or just an account holder. You disclose no more than what’s required, on an as-needed basis.

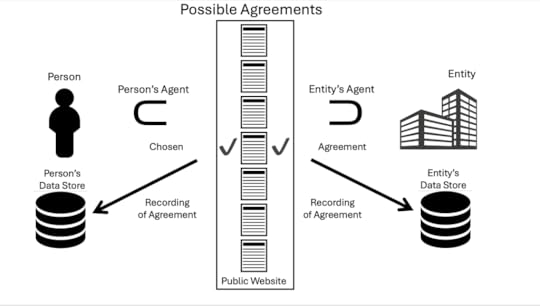

Second is contract. Specifically, terms we proffer as first parties and the sites and services of the world agree to as second parties. Guiding the deployment of those is IEEE P7012 Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, which I’ve called the most important standard in development today. I’m the chair of the P7012 working group, which has been on the case since 2017. The standard is now drafted and moving though the IEEE’s approval mill. If all goes well, it will be ready early next year. It works like this:

Possible agreements sit at a public website. Customer Commons was created for this purpose, and to do for personal contracts what Creative Commons does for personal copyrights. The person’s agent, such as a browser, acting as the first party, tells the second party (an entity of any kind) what agreement the person has chosen from a small roster of them (again, on the Creative Commons model). The entity either agrees or declines. If the two agree, the decision is recorded identically by both parties. If the entity declines, that decision is also recorded on the person’s side.

Customer Commons has one such agreement already, called P2B1 (beta), or #NoStalking. As with all contracts, there’s something in it for both parties. With #NoStalking, the person isn’t tracked away from the site or service, and the site or service still gets to advertise to the person. Customer Commons (for which I am a founder and board member) plans to have a full list of agreements ready before the end of this year. If this system works, it will replace the Internet of Accounts with something that works far better for everyone. It will also put the brakes on uninvited surveillance, big time.

Third is personal AI. This is easy to imagine if you have your own AI working on your side. It can know what kind of agreement you prefer to proffer to different kinds of sites and services. It can also help remember all the agreements that have been made already, and save you time and energy in other ways. AI on the entities’ sides can also be involved. Imagine two robot lawyers shaking hands and you can see where this might go.

There are a variety of personal (not just personalized) AI efforts out there. The one I favor, because it’s open source and inspired by The Intention Economy, is Kwaai.ai, a nonprofit community of volunteers where I also serve as chief intention officer.

I welcome your thoughts. Also your work toward replacing the Internet of Accounts with the Internet of People—plus every other entity that welcomes full personal agency.

June 25, 2024

A very local storm

It was a derecho, or something like one. The gust front you see in the third image here looks a lot like the storm front in the image above (via Weatherbug, storm tracker view). I’d experienced one twelve years ago, in Arlington, Mass. It felt like a two minute hurricane, and when it was over, hundreds of trees were down. This wasn’t as bad, but TwitteX seemed to agree that a derecho it was. And we did have many broken trees and power outages. Here’s one example of the former:

That’s half a huge silver maple. Very luckily, it missed the house and only trashed the metal fence. Pretty house, too.

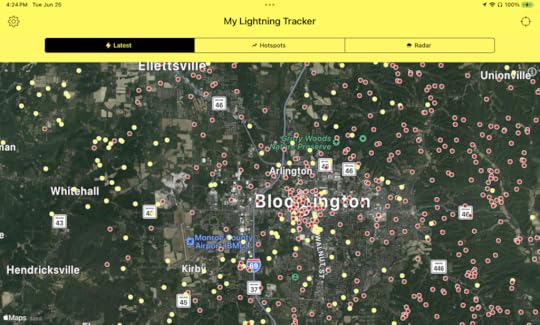

There was also a lot of lightning. Dig:

You can barely see the blue dot in the middle, but that’s where we live. One of those dots is about a hundred feet from where I’m writing this.

If you’re into this kind of stuff, I recommend the My Lightning Finder app, which produced the above. Also LightningMaps.org on the Web. That one shows thunder as circles expanding at the speed of sound around a lightning dot. Of course, lots of those lightning dots are lines in clouds, or zig-zags between ground and sky. They aren’t all “strikes.”

But when lightning does strike, one of my favorite storm sounds is a loud crack, then “Cccchhhheeeeeooooowwwwwww” before a BOOM of thunder slams the ground. What you’re hearing after the crack is sound coming off the length of the lightning strike, starting at the ground and moving up to the cloud above, with the volume of the sound and its pitch going down as it originates from farther and farther away along the length of the lightning itself. The BOOM is produced by the top of the lightning bolt, spreading or fanning out inside the cloud, parallel to the ground, so the sound comes at you from the broad side of the aerial end of the bolt. Listen for it the next time you’re in a storm and lightning strikes nearby.

June 23, 2024

Does personal AI require Big Compute?

I don’t think it does. Not for everything.

We already have personal AI for autocomplete. Do we need Big Compute for a personal AI to tell us which pieces within our Amazon orders are in which line items in our Visa statements? (Different items in a shipment often appear inside different charges on a card.) Do we need Big Compute to tell us who we had lunch with, and where, three Fridays ago? Or to give us an itemized list of all the conferences we attended in the last five years? Or what tunes or podcasts we’ve played (or heard) in the last two months (for purposes such as this one)?

Let’s say we want a list of all the books on our shelves using something like OpenCV to detect text in natural scene images using the EAST text detector? Or to use the same kind of advanced pattern recognition to catalog everything we can point a phone camera at in our homes? Even if we need to hire models from elsewhere to help us out, onboard compute should be able to do a lot of it, and to keep our personal data private.

Right now your new TV is reporting what you watch back to parties unknown. Your new car is doing the same. Hell, so is your phone. What if you had all that data? Won’t you be able to do more with it than the spies and their corporate customers can?

It might be handy to know all the movies you’ve seen and series you’ve binged on your TV and other devices—including, say, the ones you’ve watched on a plane. And to remember when it was you drove to that specialty store in some other city, what the name of it was, and what was the good place you stopped for lunch on the way.

This data should be yours first—and alone—and shared with others at your discretion. You should be able to do a lot more with information gathered about you than those other parties can—and personal AI should be able to help you do it without relying on Big Compute (beyond having its owners give you back whatever got collected about you).

At this early stage in the evolution of AI, our conceptual frame for AI is almost entirely a Big Compute one. We need much more thinking out loud about what personal AI can do. I’m sure the sum of it will end up being a lot larger than what we’re getting now from Big AI.

June 14, 2024

Jayson Tatić and the Boston Celtićs

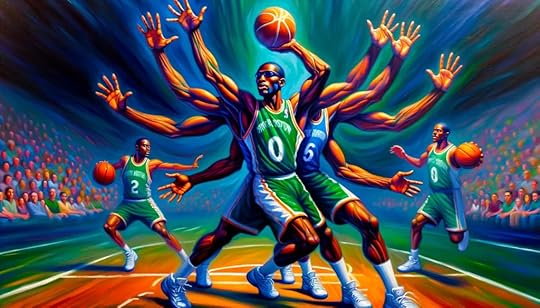

This is the best illustration I could get out of ChatGPT 4o. It’ll do until I have it get a better one.

This is the best illustration I could get out of ChatGPT 4o. It’ll do until I have it get a better one.Nobody’s talking about this, so I will: Jayson Tatum is playing a decoy. More to the point, he is playing Jokić, Dončić, or a bit of both. Not all the time (such as when he’s doing one of those step-back threes with lots of time on the clock, but enough). So let’s call him Jayson Tatić.

Because on offense he’s pulling in double and triple teams and passing expertly to open men. Over and over again. And the passes turn into assists because he is connected to those men. That’s the way the Boston Celtićs work under Joe Mazzula. Connection is everything. They are a team of fully capable all-stars, each willing to give up their own ego and stats for the sake of the team.

So, while the talking heads and talking ‘casts go on about how poor Tatum’s offense seems to be, they miss the misdirection. They assume Jayson Tatum is always wanting to play hero ball, because he can, and because that’s they guy he is. They don’t get that he’s really Jayson Tatić’, and his feint is that he’s always going to shoot, that he’s always going to post up and go one-on-two or one-on-few. Meanwhile, what he’s really doing is pulling in a defense that gives him open men, all of whom he knows, because he’s connected to them psychically, audibly (they talk!) and manually. He is always working to pass, which he does expertly.

Yeah, he turns it over sometimes. So what. He gets assists because he’s a one-man wrecking crew of misdirection, especially when he gets downhill. And the man can pass.

When this series is over, and Boston takes it 4 to 3, 2, 1, or 0, and Jaylen Brown or Jrue Holiday get the MVP (like Andre Iguodala got the MVP a few years back), the Celtics’ success will owe in no small way to Jayson’s teamwork.

There’s a game tonight, so watch for it.

June 3, 2024

Archiving a Way

These are the men who strung and assembled the cables that hold up the George Washington Bridge roadway. After this was shot, on July 25, 1929, the cable bundles were compressed, sheathed, and draped with suspension cables to the new roadway that would be built below. The photo is from the collection of Allen H. Searls, the gap-toothed guy with a big grin at the center of the photo. He was 21 at the time.

These are the men who strung and assembled the cables that hold up the George Washington Bridge roadway. After this was shot, on July 25, 1929, the cable bundles were compressed, sheathed, and draped with suspension cables to the new roadway that would be built below. The photo is from the collection of Allen H. Searls, the gap-toothed guy with a big grin at the center of the photo. He was 21 at the time.My father, Allen H. Searls, was an archivist. Not a formal one, but good in the vernacular, at least when it came to one of the most consequential things he did in his life: helping build the George Washington Bridge. He did this by photographing his work and fellow workers. He shot with a Kodak camera, and then developed and printed each shot, and assembled them into an album that survives to this day. All the shots in this collection are from that album. I’ve archived them in my Flickr site focused on infrastructure. I have also Creative Commons licensed them to require only attribution. (Though I’d rather people credit Allen H. Searls than his son.)

Only two of the photos are dated. One is July 25, 1929, when workers and families celebrated the completion of the cable stringing operation. The other is July 25, 1930, presumably when the roadway was completed. I was able to piece together the significance of these dates, and guess at the date ranges of other pictures, by doing a deep dive into the New York Times archive (where I found that these guys were called “bridgemen,” and by reading my father’s copy of the Roebling Cable company’s book about how the bridge’s cables were made and put in place.

As we know now, almost too well, we live in an Age of AI, when the entire corpus of the Internet, and God only knows what else, has been ingested into large language models that are trained and programmed to answer questions about what they “know” (even though they don’t, really). Meanwhile what do we, as human beings, actually know? Or, better yet, where can we find what we need or want to know? Libraries of the physical kind are necessary but insufficient when our instruments of inquiry are entirely electronic. The World Wide Web has turned into the World Wide Whiteboard.

We need electronic archives. Simple as that.

We all know (and, I hope, appreciate) the Internet Archive. I was going to give my father’s copy of the Roebling book to the Archive for scanning, but discovered it’s already there! That made the book easy to read (here on this flat screen), and saved my own fragile copy from further damage.

A heroic example of one person’s work to save the whole corpus of literature on broadcasting is David Gleason’s World Radio History site, without which much knowledge of broadcasting history would be lost.

On the contemporary front, Dave Askins‘ work toward online local news chronicles may prove essential if we don’t want to see current and future news disappear down the same holes into which too many past publications’ work has fallen (or remains alive but trapped behind paywalls).

For more on where this might go, see my Archives as Commons post. I’ll be talking about this, I hope, at the upcoming WoW Conference and DWeb Camp.

May 29, 2024

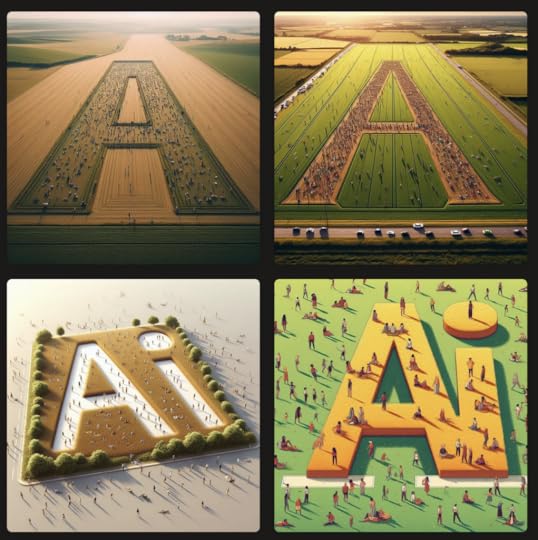

A Fun AI Fail

Here is me, trying to get ChatGPT (version 4o, which I pay for) to give me an illustration to use in my last post here, titled The People’s AI. But don’t go there yet (if you haven’t already). What I ended up using there is a punchline at the end of the dialog that starts here—

Me: A vast field on which the ground spells the letters A and I, with people on it, having a good time.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the illustration of a whimsical outdoor scene with a vast field shaped into the letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, where people are enjoying various activities, creating a cheerful and lively atmosphere.

Me: Make the two letters upper case A and upper case I, both with serifs.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration of a vast field shaped into the uppercase letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, both with serifs, where people are enjoying a sunny day outdoors. The setting is lively and festive, enhancing the creative landscape.

Me: Those are not the letters A or I, and lack serifs. Try again, with A on the left, and I on the right.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast field shaped into the uppercase serif letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, with ‘A’ on the left and ‘I’ on the right. The field is vibrant and bustling with people enjoying various outdoor activities.

Me: Better, but there is no I on the right.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast field clearly shaped into the uppercase serif letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, with ‘A’ on the left and ‘I’ on the right. The field is lively with people engaging in various activities, set in a sunny and cheerful environment.

Me: That’s an interesting design, but I need an A and an I next to each other.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing the vast field clearly shaped into the adjacent uppercase serif letters ‘A’ and ‘I’. The setting is vibrant and festive, surrounded by people enjoying various activities.

Me: That’s one big A, not an A and an I. Give me both.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast field clearly shaped into the uppercase serif letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, side by side. The setting is lively and festive, filled with people enjoying various activities.

Me: That has no serifs and is still just an A. I want an A and an I. Separate.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast field clearly shaped into the uppercase serif letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, side by side. The setting is vibrant, with people enjoying various outdoor activities.

Me: Still not separate. That’s one big A. I want an I next to it.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration, clearly showing the vast field shaped into the separate uppercase serif letters ‘A’ on the left and ‘I’ on the right. The scene is lively with people enjoying various activities under a sunny sky.

Me: Let’s try this: An “A” and an “I” in an open field full of people.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the illustration showing an open field shaped into the uppercase letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, with people enjoying various activities in the area. The scene is lively and sunny, capturing a cheerful outdoor gathering.

Me: Better! Now give me the same thing, with a complete “a.”

ChatGPT: We are experiencing heavy server load. To ensure the best experience for everyone, we have rate limits in place. Please wait for 2 minutes before generating more images. Let me know if there’s anything else you’d like to discuss in the meantime!

Me (after a 3 minute pause): Thanks. Now give me the same image, but with a complete “A.”

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast open field creatively landscaped into two distinct uppercase ‘A’ letters, bustling with people enjoying various activities in a sunny, cheerful setting.

(Yes, it created both images.)

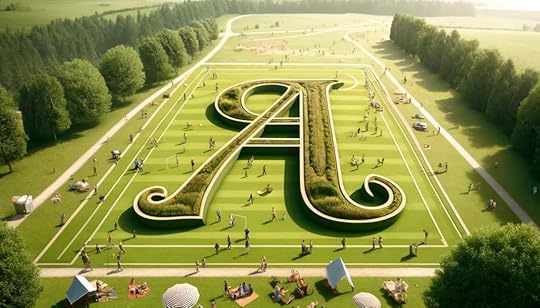

Me: Give me the same, but with people surrounding the “A” and the “I.” Also, please put serifs on the “I.”

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast open field creatively landscaped into the shapes of the uppercase letters ‘A’ and ‘I’, both with serifs. The field is surrounded by people enjoying various activities in a sunny, cheerful setting.

Me: Try the same, but with “a” and “i” as separate letters.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast open field creatively landscaped into the shapes of the lowercase letters ‘a’ and ‘i’. The setting is surrounded by people enjoying various activities in a sunny, cheerful atmosphere.

Me: Closer. Only now take it out of the city. I want only countryside.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast open field in the countryside, creatively landscaped into the shapes of the lowercase letters ‘a’ and ‘i’. The setting is serene and picturesque, surrounded by people enjoying rural activities.

Me: Please make the “a” and the “i” separate.

ChatGPT:

Here’s the updated illustration showing a vast open field in the countryside, creatively landscaped into the distinctly separated lowercase letters ‘a’ and ‘i’. The setting is serene, surrounded by people enjoying rural activities in a picturesque and peaceful outdoor gathering.

At this point I gave up and decided to give Microsoft Copilot a whack—

Me: A vast field on which the ground spells the letters A and I, with people on it, having a good time.

Microsoft Copilot:

I decided not to push my luck, and used the one on the bottom right.

It’s fun to know I am not alone at this. Here is a brilliant video of somebody far more patient than I getting ChatGPT to spell HONDA in ASCII art.

Early days, folks. Early days.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers