Doc Searls's Blog, page 43

July 29, 2019

Getting past broken cookie notices

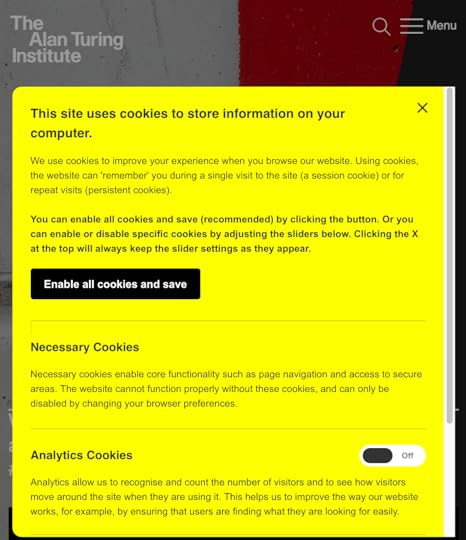

Go to the Alan Turing Institute. If it’s a first time for you, a popover will appear:

Among the many important things the Turing Institute is doing for us right now is highlighting with that notice exactly what’s wrong with the cookie system for remembering choices, and lack of them, for each of us using the Web.

As the notice points out, the site uses “necessary cookies,” “analytics cookies” (defaulted to On, in case you can’t tell from the design of that switch), and (below that) “social cookies.” Most importantly, it does not use cookies meant to track you for advertising purposes. They should brag on that one.

What these switches highlight is that the memory of your choices is theirs, not yours. The whole cookie system outsources your memory of cookie choices to the sites and services of the world. While the cookies themselves can be found somewhere deep in the innards of your computer, you have little or no knowledge of what they are or what they mean, and there are thousands of those in there already.

And yes, we do have browsers that protect us in various ways from unwelcome cookies, but they all do that differently, and none in standard ways that give us clear controls over how we deal with sites and how sites deal with us.

One way to start thinking about this is as a need for cookies go the other way:

I wrote about that last year at Linux Journal in a post by that title. A nice hack called Global Consent Manager does that.

Another way is to think (and work toward getting the sites and services of the world to agree to our terms, and to have standard ways of recording that, on our side rather than theirs. Work on that is proceeding at Customer Commons, the IEEE, various Kantara initiatives and the Me2B Alliance.

Then we will need a dashboard, a cockpit (or the metaphor of your choice) through which we can see and control what’s going on as we move about the Web. This will give us personal scale that we should have had on Day One (specifically, in 1995, when graphical browsers took off). This too should be standardized.

There can be no solution that starts on the sites’ side. None. That’s a fail that in effect gives us a different browser for every site we visit. We need solutions of our own. Personal ones. Global ones. Ones with personal scale. It’s the only way.

July 23, 2019

Where journalism fails

“What’s the story?”

No question is asked more often by editors in newsrooms than that one. And for good reason: that’s what news is about: stories.

I was just 22 when I got my first gig as a journalist, reporting for a daily newspaper in New Jersey. It was there that I first learned that all stories are built around just three elements:

Character

Problem

Movement toward resolution

You need all three. Subtract one or more, and all you have is an item, or an incident. Not a story. So let’s unpack those a bit.

The character can be a person, a group, a team, a cause—anything with a noun. Mainly the character needs to be worth caring about in some way. You can love the character, hate it (or him, or her or whatever). Mainly you have to care about the character enough to be interested.

The problem can be of any kind at all, so long as it causes conflict involving the character. All that matters is that the conflict keeps going, at least toward the possibility of resolution. If the conflict ends, the story is over. For example, if you’re at a sports event, and your team is up (or down) by forty points with five minutes left, the character you now care about is your own ass, and your problem is getting it out of the parking lot. If that struggle turns out to be interesting, it might be a story you tell later at a bar.)

Movement toward resolution is nothing more than that. Bear in mind that many stories, and many characters in many conflicts around many problems in stories, never arrive at a conclusion. In fact, that may be part of the story itself. Soap operas work that way.

For a case-in-point of how this can go very wrong, we have the character now serving as President of the United States.

Set the politics aside and just look at the dude through the prism of Story.

Trump—clearly, deeply and instinctively—understands how stories work. He is experienced and skilled at finding or causing problems that generate conflict and enlarge his own character to maximum size in the process.

He does this through constant characterization of others, for example with : “Little Mario,” “Low Energy Jeb,” “Crooked Hillary,” “Sleepy Joe,” “Failing New York Times.”

He stokes the fires of conflict by staying on the attack at all times: a strategy he learned from Roy Cohn., who Frank Rich felicitously calls “The worst human being who ever lived … the most evil, twisted, vicious bastard ever to snort coke at Studio 54.” Talk about character. Whoa. As Politico puts it here, “Cohn imparted an M.O. that’s been on searing display throughout Trump’s ascent, his divisive, captivating campaign, and his fraught, unprecedented presidency. Deflect and distract, never give in, never admit fault, lie and attack, lie and attack, publicity no matter what, win no matter what, all underpinned by a deep, prove-me-wrong belief in the power of chaos and fear.” There is genius to how Trump succeeds at this, especially in these early years of our new digital age, when the entire Internet is one big gossip mill.

Trump’s success at capturing the attention of everyone and the loyalty of many calls to mind The Mule in Isaac Azimov’s Foundation and Empire. (It from noting this resemblance that, along with Scott Adams, I expected Trump to win in 2016.)

So that’s the first way journalism fails: its appetite for stories proves a weakness when it’s fed by a genius at hogging the stage.

Journalism’s second failing is not reporting what doesn’t fit the story format. Stories are inadequate ways to represent facts and truths. Too much of both get excluded if they don’t fit “the narrative,” which is the modern way to talk about story.

There is a paradox here: that we need to know more than stories can tell, and yet stories are pretty much all human beings are interested in. Character, problem and movement give shape and purpose to every human life. We can’t correct for it.

Perhaps our best hope is to recognize something I learned from a shrink I was talking to at a party long ago. Most mental illness, she said, is just OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder. And it’s hard to say exactly what’s a “disorder,” because all human accomplishments worth celebrating owe in large measure to obsessive and compulsive interests and behaviors. And, in some cases (for example our current president’s) to narcissism and other disorders as well.

I don’t know how to fix any of that, or if it can be fixed at all. I’m just sure that journalism as a discipline will benefit by looking more closely at how stories fail: at what they can’t do, as well as at what they can.

_________

*However, if you want good advice on how best to write stories about the guy, you can’t beat what @JayRosen_NYU tweets here. I suggest it also applies to the UK’s new prime minister.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers