Doc Searls's Blog, page 36

May 30, 2021

Apple vs (or plus) Adtech, Part II

My post yesterday saw action on Techmeme (as I write this, it’s at #2) and on Twitter (from Don Marti and Augustine Fou), and in long from blog posts by John Gruber in Daring Fireball and Nick Heer in Pixel Envy. All pushed back on at least some of what I said. Here are some excerpts, with responses. First, John:

Doc Searls:

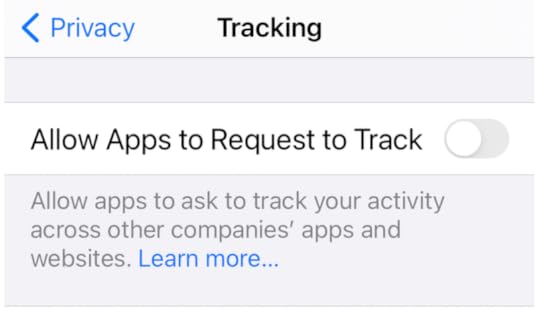

Here’s what’s misleading about this message: Felix would have had none of those trackers following him if he had gone into Settings → Privacy → Tracking, and pushed the switch to off […].

Key fact: it is defaulted to on. Meaning Apple is not fully serious about privacy. If Apple was fully serious, your iPhone would be set to not allow tracking in the first place. All those trackers would come pre-vaporized.

For all the criticism Apple has faced from the ad tech industry over this feature, it’s fun to see criticism that Apple isn’t going far enough. But I don’t think Searls’s critique here is fair. Permission to allow tracking is not on by default — what is on by default is permission for the app to ask. Searls makes that clear, I know, but it feels like he’s arguing as though apps can track you by default, and they can’t.

But I don’t think Searls’s critique here is fair. Permission to allow tracking is not on by default — what is on by default is permission for the app to ask. Searls makes that clear, I know, but it feels like he’s arguing as though apps can track you by default, and they can’t.

I’m not arguing that. So I’ll try again.

At issue here is that a system for asking in both directions (apps asking to track, and users asking apps not to track) is weird and unclear, while simply disallowing tracking globally would be clear. So would a setting that simply turns off all apps’ ability to track. But that’s not what we have here.

Or maybe we do.

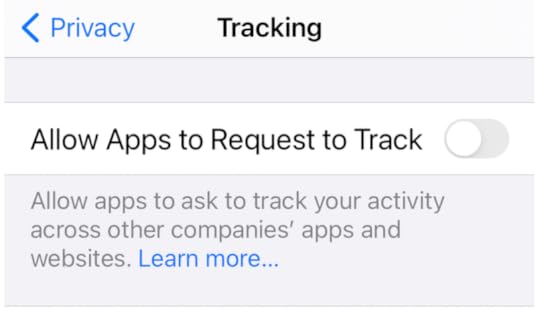

To review… in Settings—>Privacy—>Tracking, is a single OFF/ON switch for “Allow Ads to Request to Track.” It is by default set to ON. (I called AppleCare to be sure about this. The guy I spoke to said yes, it is.) Below that setting a bit of text with a “Learn more” link that goes to this long column of text one swipes down four times (at least on my phone) to read:

Okay, now look in the fifth paragraph (three up from where you’re reading now). There it says that by turning the setting to OFF, “all apps…will be blocked from accessing the device’s Advertising Identifier.” Maybe I’m reading this wrong, but it seems clear to me that this will at least pre-vaporize trackers vectored on the device identifier (technically called IDFA: ID For Advertisers).

After explaining why he thinks the default setting to ON is the better choice, and why he likes it that way (e.g. he can see what apps want to track, surprisingly few do, and he knows which they are), John says this about the IDFA:

IDFA was well-intentioned, but I think in hindsight Apple realizes it was naive to think the surveillance ad industry could be trusted with anything.

And why “ask” an app not to track? Why not “tell”? Or, better yet, “Prevent Tracking By This App”? Does asking an app not to track mean it won’t?

This is Apple being honest. Apple can block apps from accessing the IDFA identifier, but there’s nothing Apple can do to guarantee that apps won’t come up with their own device fingerprinting schemes to track users behind their backs. Using “Don’t Allow Tracking” or some such label instead of “Ask App Not to Track” would create the false impression that Apple can block any and all forms of tracking. It’s like a restaurant with a no smoking policy. That doesn’t mean you won’t go into the restroom and find a patron sneaking a smoke. I think if Apple catches applications circumventing “Ask App Not to Track” with custom schemes, they’ll take punitive action, just like a restaurant might ask a patron to leave if they catch them smoking in the restroom — but they can’t guarantee it won’t happen. (Joanna Stern asked Craig Federighi about this in their interview a few weeks ago, and Federighi answered honestly.)

If Apple could give you a button that guaranteed an app couldn’t track you, they would, and they’d label it appropriately. But they can’t so they don’t, and they won’t exaggerate what they can do.

On Twitter Don Marti writes,

Unfortunately it probably has to be “ask app not to track” because some apps will figure out ways around the policy (like all mobile app store policies). Probably better not to give people a false sense of security if they are suspicious of an app

—and then points to P&G Worked With China Trade Group on Tech to Sidestep Apple Privacy Rules, subtitled “One of world’s largest ad buyers spent years building marketing machine reliant on digital user data, putting it at odds with iPhone maker’s privacy moves” in The Wall Street Journal. In it is this:

P&G marketing chief Marc Pritchard has advocated for a universal way to track users across platforms, including those run by Facebook and Alphabet Inc.’s Google, that protects privacy while also giving marketers information to better hone their messages.

Frustrated with what it saw as tech companies’ lack of transparency, P&G began building its own consumer database several years ago, seeking to generate detailed intelligence on consumer behavior without relying on data gathered by Facebook, Google and other platforms. The information is a combination of anonymous consumer IDs culled from devices and personal information that customers share willingly. The company said in 2019 that it had amassed 1.5 billion consumer identifications world-wide.

China, where Facebook and Google have a limited presence, is P&G’s most sophisticated market for using that database. The company funnels 80% of its digital-ad buying there through “programmatic ads” that let it target people with the highest propensity to buy without presenting them with irrelevant or excessive ads, P&G Chief Executive Officer David Taylor said at a conference last year.

“We are reinventing brand building, from wasteful mass marketing to mass one-to-one brand building fueled by data and technology,” he said. “This is driving growth while delivering savings and efficiencies.”

After I tweeted,

Won’t app makers find ways to work around the no tracking ask, regardless of whether it’s a global or a one-at-a-time setting? That seems to be what the

@WSJ is saying about @ProcterGamble ‘s work with #CAID device fingerprinting.

Don replied,

Yes. Some app developers will figure out a way to track you that doesn’t get caught by the App Store review. Apple can’t promise a complete “stop this app from tracking me” feature because sometimes it will be one of those apps that’s breaking the rules

Augustine Fou replied,

of course, MANY ad tech companies have been working on fingerprinting for years, as a work around to browsers (like Firefox) allowing users to delete cookies many years ago. Fingerprinting is even more pernicious because it is on server-side and out of control of user entirely

Augustine’s last point is what I’ve been trying to address (in ways surely no less arguable than what I’ve said on this topic) the problem of the client server model itself, which all but guarantees a feudal system in which clients are all serfs and site operators (and Big Tech in general) are our lords and masters. Though my original metaphor for client-server (which I have been told was originally a euphemism for slave-master) was calf-cow:

That one and other metaphors follow:

A sense of bewronging (from 2011)Stop making cows. Quit being calves (from 2012)Is being less tasty vegetables our best strategy? (2021)Thinking outside the browser (2021)Toward e-commerce 2.0 (2021)How the cookie poisoned the Web (2021)I’ll pick up that thread after visiting what Nick says about fingerprinting:

There are countless ways that devices can be fingerprinted, and the mandated use of IDFA instead of those surreptitious methods makes it harder for ad tech companies to be sneaky. It has long been possible to turn off IDFA or reset the identifier. If it did not exist, ad tech companies would find other ways of individual tracking without users’ knowledge, consent, or control.

And why “ask” an app not to track? Why not “tell”? Or, better yet, “Prevent Tracking By This App”? Does asking an app not to track mean it won’t?

History has an answer for those questions.

Remember Do Not Track? Invented in the dawn of tracking, back in the late ’00s, it’s still a setting in every one of our browsers. But it too is just an ask — and ignored by nearly every website on Earth.

Much like Do Not Track, App Tracking Transparency is a request — verified as much as Apple can by App Review — to avoid false certainty. Tracking is a pernicious reality of every internet-connected technology. It is ludicrous to think that any company could singlehandedly find and disable all forms of fingerprinting in all apps, or to guarantee that users will not be tracked.

I agree. This too is a problem with the feudal world that the Web + app world has become, and Nick is right to point it out. He continues,

The thing that bugs me is that Searls knows all of this. He’s Doc Searls; he has an extraordinary thirteen year history of writing about this stuff. So I am not entirely sure why he is making arguments like the ones above that, with knowledge of his understanding of this space, begin to feel disingenuous. I have been thinking about this since I read this article last night and I have not come to a satisfactory realistic conclusion.

Here’s a realistic conclusion (or at least the one that’s in my head right now): I was mistaken to assume that Apple has more control here than it really does, and it’s right for all you guys (Nick, John, Augustine, Don and others) to point that out. Hey, I gave in to wishful thinking and unconscious ad hominem argumentation. Mea bozo. I sit corrected.

He continues,

Apple is a big, giant, powerful company — but it is only one company that operates within the realities of legal and technical domains. We cannot engineer our way out of the anti-privacy ad tech mess. The only solution is regulatory. That will not guarantee that bad actors do not exist, but it could create penalties for, say, Google when it ignores users’ choices or Dr. B when it warehouses medical data for unspecified future purposes.

We’ve had the GDPR and the CCPA in enforceable forms for awhile now, and the main result, for us mere “data subjects” (GDPR) and “consumers” (CCPA) is a far worse collection of experiences in using the Web.

At this point my faith in regulation (which I celebrated, at least in the GDPR case, when it went into force) is less than zero. So is my faith in tech, within the existing system.

So I’m moving on, and working on a new approach, outside the whole feudal system, which I describe in A New Way. It’s truly new and small, but I think it can be huge: much bigger than the existing system, simply because we on the demand side will have better ways of informing supply (are you listening, Mark Pritchard?) than even the best surveillance systems can guess at.

May 29, 2021

Apple vs (or plus) Adtech, Part I

This piece has had a lot of very smart push-back (and forward, but mostly back). I respond to it in Part II, here.

If you haven’t seen it yet, watch Apple’s Privacy on iPhone | tracked ad. In it a guy named Felix (that’s him, above) goes from a coffee shop to a waiting room somewhere, accumulating a vast herd of hangers-on along the way. The herd represents trackers in his phone, all crowding his personal space while gathering private information about him. The sound track is “Mind Your Own Business,” by Delta 5. Lyrics:

Can I have a taste of your ice cream?

Can I lick the crumbs from your table?

Can I interfere in your crisis?

No, mind your own business

No, mind your own business

Can you hear those people behind me?

Looking at your feelings inside me

Listen to the distance between us

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Can you hear those people behind me?

Looking at your feelings inside me

Listen to the distance between us

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Why don’t you mind your own business?

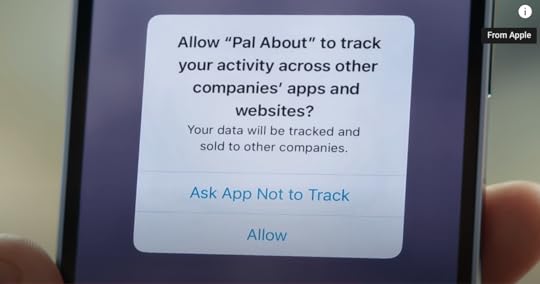

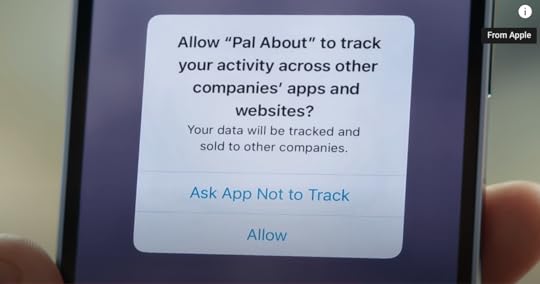

The ad says this when Felix checks his phone from the crowded room filled with people spying on his life:

Then this:

Finally, when he presses “Ask App Not to Track,” all the hangers-on go pop and turn to dust—

Followed by

Except that she gets popped too:

Meaning he doesn’t want any one of those trackers in his life.

The final image is the one at the top.

Here’s what’s misleading about this message: Felix would have had none of those trackers following him if he had gone into Settings—>Privacy—>Tracking, and pushed the switch to off, like I’ve done here:

Key fact: it is defaulted to on. Meaning Apple is not fully serious about privacy. If Apple was fully serious, your iPhone would be set to not allow tracking in the first place. All those trackers would come pre-vaporized. And Apple never would have given every iPhone an IDFA—ID For Advertisers—in the first place. (And never mind that they created IDFA back in 2013 partly to wean advertisers from tracking and targeting phones’ UDIDs (unique device IDs).

Defaulting the master Tracking setting to ON means Felix has to tap “Ask App Not To Track” for every single one of those hangers-on. Meaning that one click won’t vaporize all those apps at once. Just one at a time. This too is misleading as well as unserious.

And why “ask” an app not to track? Why not “tell”? Or, better yet, “Prevent Tracking By This App”? Does asking an app not to track mean it won’t?

History has an answer for those questions.

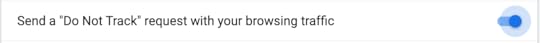

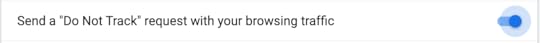

Remember Do Not Track? Invented in the dawn of tracking, back in the late ’00s, it’s still a setting in every one of our browsers. But it too is just an ask—and ignored by nearly every website on Earth.

Here is how the setting looks, buried deep on Google’s Chrome:

It’s hardly worth bothering to turn that on (it’s defaulted to off), because it became clear long ago that Do Not Track was utterly defeated by the adtech biz and its dependents in online publishing. The standard itself was morphed to meaninglessness at the W3C, where by the end (in 2019) it got re-branded “Tracking Preference Expression.” (As if any of us has a preference for tracking other than to make it not happen or go away.)

By the way, thanks to adtech’s defeat of Do Not Track in 2014, people took matters into their own hands, by installing ad and tracking blockers en masse, turning ad blocking, an option that had been laying around since 2004, into the biggest boycott in world history by 2015.

And now we have one large company, Apple, making big and (somewhat, as we see above) bold moves toward respecting personal privacy. That’s good as far as it goes. But how far is that, exactly? To see how far, here are some questions:

Will “asking” apps not to track on an iPhone actually make an app not track?How will one be able to tell?What auditing and accounting mechanisms are in place—on your phone, on the apps’ side, or at Apple?As for people’s responses to Apple’s new setting, here are some numbers for a three-week time frame: April 26 to May 16. They come from FLURRY, a subsidiary of Verizon Media, which is an adtech company. I’ll summarize:

For “Worldwide daily op-in rate after iOS 14.5 launch across all apps,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who allow app tracking among uses who have chosen to either allow or deny tracking” started at 11% and rose to 15%.The “U.S. Daily opt-in rate after iOS launch across all apps,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who allow app tracking among users who have chosen to either allow or deny tracking” started at 2% and rose to 6%.The “Worldwide daily opt-in rate across apps that have displayed the prompt,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who allow app tracking among users who have chosen to either allow or deny tracking” started at 31% and went down to 24%.The “Worldwide daily share of mobile app users with ‘restricted’ app tracking” (that’s where somebody goes into Settings—>Privacy—>Tracking and switches off “Allow Apps to Request to Track”), expressed as “% of mobile active app users who cannot be tracked by default and don’t have a choice to select a tracking option” started and stayed within a point of 5% .And the “U.S. daily share of mobile app users with ‘restricted’ app tracking,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who cannot be tracked by default and don’t have a choice to select a tracking option” started at 4% and ended at 3%, with some dips to 2%.Clearly tracking isn’t popular, but those first two numbers should cause concern for those who want tracking to stay unpopular. The adtech business is relentless in advocacy of tracking, constantly pitching stories about how essential tracking-based “relevant,” “personalized” and “interest-based” advertising is—for you, and for the “free” Web and Internet.

It is also essential to note that Apple does advertising as well. Here’s Benedict Evans on a slope for Apple that is slippery in several ways:

Apple has built up its own ad system on the iPhone, which records, tracks and targets users and serves them ads, but does this on the device itself rather than on the cloud, and only its own apps and services. Apple tracks lots of different aspects of your behaviour and uses that data to put you into anonymised interest-based cohorts and serve you ads that are targeted to your interests, in the App Store, Stocks and News apps. You can read Apple’s description of that here – Apple is tracking a lot of user data, but nothing leaves your phone. Your phone is tracking you, but it doesn’t tell anyone anything.

This is conceptually pretty similar to Google’s proposed FLoC, in which your Chrome web browser uses the web pages you visit to put you into anonymised interest-based cohorts without your browsing history itself leaving your device. Publishers (and hence advertisers) can ask Chrome for a cohort and serve you an appropriate ad rather than tracking and targeting you yourself. Your browser is tracking you, but it doesn’t tell anyone anything -except for that anonymous cohort.

Google, obviously, wants FLoC to be a generalised system used by third-party publishers and advertisers. At the moment, Apple runs its own cohort tracking, publishing and advertising as a sealed system. It has begun selling targeted ads inside the App Store (at precisely the moment that it crippled third party app install ads with IDFA), but it isn’t offering this tracking and targeting to anyone else. Unlike FLoC, an advertiser, web page or app can’t ask what cohort your iPhone has put you in – only Apple’s apps can do that, including the app store.

So, the obvious, cynical theory is that Apple decided to cripple third-party app install ads just at the point that it was poised to launch its own, and to weaken the broader smartphone ad model so that companies would be driven towards in-app purchase instead. (The even more cynical theory would be that Apple expects to lose a big chunk of App Store commission as a result of lawsuits and so plans to replace this with app install ads. I don’t actually believe this – amongst other things I think Apple believes it will win its Epic and Spotify cases.)

Much more interesting, though, is what happens if Apple opens up its cohort tracking and targeting, and says that apps, or Safari, can now serve anonymous, targeted, private ads without the publisher or developer knowing the targeting data. It could create an API to serve those ads in Safari and in apps, without the publisher knowing what the cohort was or even without knowing what the ad was. What if Apple offered that, and described it as a truly ‘private, personalised’ ad model, on a platform with at least 60% of US mobile traffic, and over a billion global users?…

Apple has a tendency to build up strategic assets in discrete blocks and small parts of products, and then combine them into one. It’s been planning to shift the Mac to its own silicon for close to a decade, and added biometrics to its products before adding Apple Pay and then a credit card. Now it has Apple Pay and ‘Sign in with Apple’ as new building blocks on the web, that might be combined into other things. It seems pretty obvious that Privacy is another of those building blocks, deployed step by step in lots of different places. Privacy has been good business for Apple, and advertising is a bigger business than all of those.

All of which is why I’ve lately been thinking that privacy is a losing battle on the Web. And that we need to start building a byway around the whole mess: one where demand can signal supply about exactly what it wants, rather than having demand constantly being spied on and guessed at by adtech’s creepy machinery.

Apple vs (or plus) Adtech

If you haven’t seen it yet, watch Apple’s Privacy on iPhone | tracked ad. In it a guy named Felix (that’s him, above) goes from a coffee shop to a waiting room somewhere, accumulating a vast herd of hangers-on along the way. The herd represents trackers in his phone, all crowding his personal space while gathering private information about him. The sound track is “Mind Your Own Business,” by Delta 5. Lyrics:

Can I have a taste of your ice cream?

Can I lick the crumbs from your table?

Can I interfere in your crisis?

No, mind your own business

No, mind your own business

Can you hear those people behind me?

Looking at your feelings inside me

Listen to the distance between us

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Can you hear those people behind me?

Looking at your feelings inside me

Listen to the distance between us

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Why don’t you mind your own business?

The ad says this when Felix checks his phone from the crowded room filled with people spying on his life:

Then this:

Finally, when he presses “Ask App Not to Track,” all the hangers-on go pop and turn to dust—

Followed by

Except that she gets popped too:

Meaning he doesn’t want any one of those trackers in his life.

The final image is the one at the top.

Here’s what’s misleading about this message: Felix would have had none of those trackers following him if he had gone into Settings—>Privacy—>Tracking, and pushed the switch to off, like I’ve done here:

Key fact: it is defaulted to on. Meaning Apple is not fully serious about privacy. If Apple was fully serious, your iPhone would be set to not allow tracking in the first place. All those trackers would come pre-vaporized. And Apple never would have given every iPhone an IDFA—ID For Advertisers—in the first place. (And never mind that they created IDFA back in 2013 partly to wean advertisers from tracking and targeting phones’ UDIDs (unique device IDs).

Defaulting the master Tracking setting to ON means Felix has to tap “Ask App Not To Track” for every single one of those hangers-on. Meaning that one click won’t vaporize all those apps at once. Just one at a time. This too is misleading as well as unserious.

And why “ask” an app not to track? Why not “tell”? Or, better yet, “Prevent Tracking By This App”? Does asking an app not to track mean it won’t?

History has an answer for those questions.

Remember Do Not Track? Invented in the dawn of tracking, back in the late ’00s, it’s still a setting in every one of our browsers. But it too is just an ask—and ignored by nearly every website on Earth.

Here is how the setting looks, buried deep on Google’s Chrome:

It’s hardly worth bothering to turn that on (it’s defaulted to off), because it became clear long ago that Do Not Track was utterly defeated by the adtech biz and its dependents in online publishing. The standard itself was morphed to meaninglessness at the W3C, where by the end (in 2019) it got re-branded “Tracking Preference Expression.” (As if any of us has a preference for tracking other than to make it not happen or go away.)

By the way, thanks to adtech’s defeat of Do Not Track in 2014, people took matters into their own hands, by installing ad and tracking blockers en masse, turning ad blocking, an option that had been laying around since 2004, into the biggest boycott in world history by 2015.

And now we have one large company, Apple, making big and (somewhat, as we see above) bold moves toward respecting personal privacy. That’s good as far as it goes. But how far is that, exactly? To see how far, here are some questions:

Will “asking” apps not to track on an iPhone actually make an app not track?How will one be able to tell?What auditing and accounting mechanisms are in place—on your phone, on the apps’ side, or at Apple?As for people’s responses to Apple’s new setting, here are some numbers for a three-week time frame: April 26 to May 16. They come from FLURRY, a subsidiary of Verizon Media, which is an adtech company. I’ll summarize:

For “Worldwide daily op-in rate after iOS 14.5 launch across all apps,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who allow app tracking among uses who have chosen to either allow or deny tracking” started at 11% and rose to 15%.The “U.S. Daily opt-in rate after iOS launch across all apps,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who allow app tracking among users who have chosen to either allow or deny tracking” started at 2% and rose to 6%.The “Worldwide daily opt-in rate across apps that have displayed the prompt,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who allow app tracking among users who have chosen to either allow or deny tracking” started at 31% and went down to 24%.The “Worldwide daily share of mobile app users with ‘restricted’ app tracking” (that’s where somebody goes into Settings—>Privacy—>Tracking and switches off “Allow Apps to Request to Track”), expressed as “% of mobile active app users who cannot be tracked by default and don’t have a choice to select a tracking option” started and stayed within a point of 5% .And the “U.S. daily share of mobile app users with ‘restricted’ app tracking,” expressed as “% of mobile active app users who cannot be tracked by default and don’t have a choice to select a tracking option” started at 4% and ended at 3%, with some dips to 2%.Clearly tracking isn’t popular, but those first two numbers should cause concern for those who want tracking to stay unpopular. The adtech business is relentless in advocacy of tracking, constantly pitching stories about how essential tracking-based “relevant,” “personalized” and “interest-based” advertising is—for you, and for the “free” Web and Internet.

It is also essential to note that Apple does advertising as well. Here’s Benedict Evans on a slope for Apple that is slippery in several ways:

Apple has built up its own ad system on the iPhone, which records, tracks and targets users and serves them ads, but does this on the device itself rather than on the cloud, and only its own apps and services. Apple tracks lots of different aspects of your behaviour and uses that data to put you into anonymised interest-based cohorts and serve you ads that are targeted to your interests, in the App Store, Stocks and News apps. You can read Apple’s description of that here – Apple is tracking a lot of user data, but nothing leaves your phone. Your phone is tracking you, but it doesn’t tell anyone anything.

This is conceptually pretty similar to Google’s proposed FLoC, in which your Chrome web browser uses the web pages you visit to put you into anonymised interest-based cohorts without your browsing history itself leaving your device. Publishers (and hence advertisers) can ask Chrome for a cohort and serve you an appropriate ad rather than tracking and targeting you yourself. Your browser is tracking you, but it doesn’t tell anyone anything -except for that anonymous cohort.

Google, obviously, wants FLoC to be a generalised system used by third-party publishers and advertisers. At the moment, Apple runs its own cohort tracking, publishing and advertising as a sealed system. It has begun selling targeted ads inside the App Store (at precisely the moment that it crippled third party app install ads with IDFA), but it isn’t offering this tracking and targeting to anyone else. Unlike FLoC, an advertiser, web page or app can’t ask what cohort your iPhone has put you in – only Apple’s apps can do that, including the app store.

So, the obvious, cynical theory is that Apple decided to cripple third-party app install ads just at the point that it was poised to launch its own, and to weaken the broader smartphone ad model so that companies would be driven towards in-app purchase instead. (The even more cynical theory would be that Apple expects to lose a big chunk of App Store commission as a result of lawsuits and so plans to replace this with app install ads. I don’t actually believe this – amongst other things I think Apple believes it will win its Epic and Spotify cases.)

Much more interesting, though, is what happens if Apple opens up its cohort tracking and targeting, and says that apps, or Safari, can now serve anonymous, targeted, private ads without the publisher or developer knowing the targeting data. It could create an API to serve those ads in Safari and in apps, without the publisher knowing what the cohort was or even without knowing what the ad was. What if Apple offered that, and described it as a truly ‘private, personalised’ ad model, on a platform with at least 60% of US mobile traffic, and over a billion global users?…

Apple has a tendency to build up strategic assets in discrete blocks and small parts of products, and then combine them into one. It’s been planning to shift the Mac to its own silicon for close to a decade, and added biometrics to its products before adding Apple Pay and then a credit card. Now it has Apple Pay and ‘Sign in with Apple’ as new building blocks on the web, that might be combined into other things. It seems pretty obvious that Privacy is another of those building blocks, deployed step by step in lots of different places. Privacy has been good business for Apple, and advertising is a bigger business than all of those.

All of which is why I’ve lately been thinking that privacy is a losing battle on the Web. And that we need to start building a byway around the whole mess: one where demand can signal supply about exactly what it wants, rather than having demand constantly being spied on and guessed at by adtech’s creepy machinery.

May 19, 2021

Making useful photographs

I guess (though I don’t yet know) that we drive a bucket of lithium around in the battery our new hybrid Toyota. Whether that’s the case or not, I’m interested in the topic, because getting more lithium (second from the top on the left edge of your periodic table) out of the ground is kind of a big, news-making issue right now. For example, Ivan Penn and Eric Lipton visit the topic in The Lithium Gold Rush: Inside the Race to Power Electric Vehicles, in the 6 May New York Times. At issue is extraction, which “might not be very green.”

But it is blue. Or turquoise. Or aqua. Or whatever colors you see in the photo above.

I took that shot on a 2010 flight between Reno and Phoenix, on my way back from the former to Boston: RNO to PHX to BOS, as the airlines say. I posted 130 photos from that flight in one album on Flickr, plus 17 in Lithium Mines in Nevada and the same collection in a 329-photo album called Mines and Mining. None are especially artistic, though all are useful, especially to writers and publications covering the topic of lithium mining. For example, photos like the one above appear in—

Biden clean energy talk fuels mining reform bills in E&EWhat an ancient lake in Nevada reveals about the future of tech in Fast CompanyTRANSITION TO ELECTRIC CARS NEED NOT DEMAND A TOXIC LITHIUM LEGACY, in Energy MixLeading the Charge…To Lithium And Beyond? in Nevada ForwardLithium: Commodity Overview in Geology for InvestorsLithium mining innovators secure investment from Bill Gates-led fund in Mining TechnologyThe Path to Lithium Batteries: Friend or Foe? in TreehuggerAnd those are just the first six among 23,200 results in a search for my name + lithium. And those results are just from pubs that have bothered to obey my Creative Commons license, which only requires attribution. Countless others don’t.

Google also finds 57,400 results for my name + mining. On top of those, there are also thousands of other results for potash, river, geology, mining, mountains, dunes, desert, beach, ocean, hebrides, glacier, and other landforms sometimes best viewed from above. And that’s on top of more than 1500 photos of mine parked in Wikimedia Commons, of which many (perhaps most) are already in Wikipedia (sometimes in multiple places) or on their way there.

I have placed none of those photos in any of those places. I just put them up where they can easily be found and put to use. For example, when I shot Thedford, Nebraska, I knew somebody would find the photo and put it in Wikipedia (at that last link).

Shots like these are a small percentage of all the photos I’ve produced. I’ve taken many more photos of people and other subjects on the ground or in buildings. Most of those are on hard drive nobody else looks at, or in albums or boxes likely to be tossed by unsentimental heirs after I’m gone. Meaning that my main calling as a photographer is this kind of stuff.

Which brings me to a camera question.

My main camera is a 2015-vintage Canon 5D Mark III with a 24-105 f4 L lens, both of which are beat up and showing signs of mortality. I also have an iPhone 11 that I use quite a bit because it is far more portable than the Canon. Most of the photos you see in those searches were taken with this Canon or one of its elders: a 5D from 2005 or a 30D from 2000. A few more were shot with a Nikon Coolpix replaced by the series of Canons.

Now an old friend is giving me her Sony a7R, which has been idle since she replaced it with a Sony a7Riii. I’ve played with her newer Sony, and really like how much lighter mirrorless full-frames can be. (And the one she’s giving me is lighter than the newer model.) The question is, what kind of lens do I want to start with here, given that my budget is $0 (though I will spend more than that). The equivalent of the Canon 24-105 f4 L that I used to shoot most of the photos the world is leveraging runs ~$1000. I suppose I could get non-Sony lenses for less, but … I’m not sure. I’m kinda tempted to get a telephoto zoom or prime for the Sony and keep using the Canon for everything else. But then I’m carrying two cameras everywhere.

But I just looked at this, so maybe I’ll find a bullet to bite, and spend the grand.

May 14, 2021

How the cookie poisoned the Web

Have you ever wondered why you have to consent to terms required by the websites of the world, rather than the other way around? Or why you have no record of your own of what you have accepted or agreed to?

Blame the cookie.

Have you wondered why you have no more privacy on the Web than what other parties grant you, which happens only by opt-in or opt-out choices that others provide—while the only controls you have over your privacy are to skulk around like a criminal (thank you, Edward Snowden and Russell Brand, for that analogy) or to stay offline completely?

Blame the cookie.

And have you paused to wonder why Europe’s GDPR regards you as a mere “data subject” while assuming that the only parties qualified to be “data controllers” and “data processors” are the sites and services of the world, leaving you with little more agency than those sites and services allow, or provide you?

Blame the cookie.

Or why California’s CCPA regards you as a mere “consumer” (not a producer, much less a complete human being), and only gives you the right to ask the sites and services of the world to give back data gathered about you, or not to “sell” that personal data, whatever the hell that means?

Blame the cookie.

There are more examples, but you get the point: this situation has become so established that it’s hard to imagine any other way for the Web to operate.

Now here’s another point: it didn’t have to be that way.

The World Wide Web that Tim Berners-Lee invented didn’t have cookies. It also didn’t have websites. It had pages one could publish or read, at any distance across the Internet.

This original Web was simple and peer-to-peer. It was meant to be personal as well, meaning an individual could publish with a server or read with a browser. One could also write pages easily with an HTML editor, which was also easy to invent and deploy.

It should help to recall that the Apache Web server, which published most of the world’s Web pages through most the time the Web has been around, was meant originally to work as a personal server. Because the original design assumption was that anyone, from individuals to large enterprises, could have a server of their own, and publish whatever they wanted on it. The same went for people reading pages on the Web.

Back in the 90s my own website, searls.com, ran on a box under my desk. It could do that because, even though my connection was just dial-up speed, it was on full time over its own static IP address, which I easily rented from my ISP. So easy, in fact, that I had sixteen of those addresses, so I could operate another server in my office for storing and transfering articles and columns I wrote for Linux Journal. Every night a cron utility would push what I wrote to the magazine itself. Both servers ran Apache. And none of this was especially geeky. (I’m not a programmer and the only code I know is Morse.)

My point here is that the Web back then was still peer-to-peer and welcoming to individuals who wished to operate at full agency. It even stayed that way through the Age of Blogs in the early ’00s.

But gradually a poison disabled personal agency. That poison was the cookie.

Technically a cookie is a token—a string of text—left by one computer program with another, to help the two remember each other.

But the Web got a special kind of cookie called the HTTP cookie. This, Wikipedia says (at that link)

…is a small piece of data stored on the user‘s computer by the web browser while browsing a website. Cookies were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember stateful information (such as items added in the shopping cart in an online store) or to record the user’s browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, or recording which pages were visited in the past). They can also be used to remember pieces of information that the user previously entered into form fields, such as names, addresses, passwords, and payment card numbers.

It also says,

Cookies perform essential functions in the modern web. Perhaps most importantly, authentication cookies are the most common method used by web servers to know whether the user is logged in or not, and which account they are logged in with.

This, however, was not the original idea, which Lou Montulli came up with in 1994. His idea was just for a server to remember the last state of a browser’s interaction with it. But that one move—a server putting a cookie inside every visiting browser—crossed a privacy threshold: a personal boundary that should have been clear from the start but was not.

And the number and variety of cookies only increased. To switch metaphors, a snowball started rolling.

Today that snowball is so large that nearly all personal agency on the Web is within the separate silos of every website on the Net, all of them maintaining browser and personal app dependency on websites and third party services, most of which are unknown to the individual.

This is why most of the great stuff you can do on the Web is by grace of Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, WordPress and countless others, including those third parties.

Lost—because they never happened—are native capacities of your own that can operate at scale across all those websites and services. Instead we all now live inside what Bruce Schneier calls a feudal system:

Some of us have pledged our allegiance to Google: We have Gmail accounts, we use Google Calendar and Google Docs, and we have Android phones. Others have pledged allegiance to Apple: We have Macintosh laptops, iPhones, and iPads; and we let iCloud automatically synchronize and back up everything. Still others of us let Microsoft do it all. Or we buy our music and e-books from Amazon, which keeps records of what we own and allows downloading to a Kindle, computer, or phone. Some of us have pretty much abandoned e-mail altogether … for Facebook.

These vendors are becoming our feudal lords, and we are becoming their vassals.

Bruce wrote that in 2012, about the time we invested hope in Do Not Track, which was designed as a polite request one could turn on in a browser, and servers could obey.

Alas, the tracking-based online advertising business and its dependents in publishing dismissed Do Not Track with contempt.

Starting in 2013, we serfs fought back, by the hundreds of millions, blocking ads and tracking: the biggest boycott in world history. This, however, did nothing to stop what Shoshana Zuboff calls Surveillance Capitalism and Brett Frischmann and Evan Selinger call Re-engineering Humanity.

And, despite landmark works such as those, the snowball keeps rolling.

Nearly all of advertising on the Internet today is of the personalized kind that requires cookies shoved into your browsers and apps on your personal devices, so ads can be aimed at you.

Never mind that the tracking based advertising business (aka adtech) is deeply corrupt: filled with fraud, botnets and malware. And that most of the money spent on adtech goes to intermediaries and not to the media you (as they like to say) consume. It’s a freaking fecosystem, and every participant’s dependence on it is extreme.

Take, for example, Vizio TVs. As Samuel Axon puts it in Ars Technica, Vizio TV buyers are becoming the product Vizio sells, not just its customers Vizio’s ads, streaming, and data business grew 133 percent year over year.

Without cookies and the cookie-like trackers by which Vizio and its third parties can target customers directly, that business wouldn’t be there.

As a measure of how deeply this poisoning has gone, dig this: FouAnalytics‘ PageXray says the Ars Technica story above comes to your browser with all this spyware you don’t ask for or expect when you click on that link:

Adserver Requests: 786Tracking Requests: 532Other Requests: 112

I’m also betting that nobody reporting for a Condé Nast publication will touch that third rail, which I have been challenging journalists to do in 139 posts, essays, columns and articles, starting in 2008.

(Please prove me wrong, @SamuelAxon—or any reporter other than Farhad Manjoo, who so far is the only journalist from a major publication I know to have bitten the robotic hand that feeds them. I also note that the hand in this case is The New York Times‘, and that it has backed off a great deal in the amount of tracking it does. Hats off for that.)

At this stage of the Web’s moral devolution, it is nearly impossible to think outside the cookie-based fecosystem. If it was, we would get back the agency we lost, and the regulations we’re writing would respect and encourage that agency as well.

But that’s not happening, in spite of all the positive privacy moves Apple, Brave, Mozilla, Consumer Reports, the EFF and others are making.

My hat’s off to all of them; but the poisoning is too far advanced. After fighting it for more than 22 years (dating from publishing The Cluetrain Manifesto in 1999), I’m moving on.

To here.

May 7, 2021

First iPhone mention?

I wrote this fake story on January 24, 2005, in an email to Peter Hirshberg after we jokingly came up with it during a phone call. Far as I know, it was the first mention of the word “iPhone.”

Apple introduces one-button iPhone Shuffle

To nobody’s surprise, Apple’s long-awaited entry into the telephony market is no less radical and minimalistic than the one-button mouse and the gum-stick-sized music player. In fact, the company’s new cell phone — developed in deeply secret partnership with Motorola — extends the concept behind the company’s latest iPod, as well as its brand identity.

Like the iPod Shuffle, the new iPhone Shuffle has no display. It’s an all-white rectangle with a little green light to show that a call is in progress. While the iPhone Shuffle resembles the iPod Shuffle, its user interface is even more spare. In place of the round directional “wheel” of the iPods, the iPhone Shuffle sports a single square button. When pressed, the iPod Shuffle dials a random number from its phone book.

“Our research showed that people don’t care who they call as much as they care about being on the phone,” said Apple CEO Steve Jobs. “We also found that most cell phone users hate routine, and prefer to be surprised. That’s just as true for people answering calls as it is for people making them. It’s much more liberating, and far more social, to call people at random than it is to call them deliberately.”

Said (pick an analyst), “We expect the iPhone Shuffle will do as much to change the culture of telephony as the iPod has done to change the culture of music listening.”

Safety was also a concern behind the one-button design. “We all know that thousands of people die on highways every year when they take their eyes off the road to dial or answer a cell phone,” Jobs said. “With the iPhone Shuffle, all they have to do is press one button, simple as that.”

For people who would rather dial contacts in order than at random, the iPhone Shuffle (like the iPod Shuffle) has a switch that allows users to call their phone book in the same order as listings are loaded loaded from the Address Book application.

To accommodate the new product, Apple also released Version 4.0.1 of Address Book, which now features “phonelists” modeled after the familiar “playlists” in iTunes. These allow the iPhone Shuffle’s phone book to be populated by the same ‘iFill’ system that loads playlists from iTunes into iPod Shuffles.

A number of online sites reported that Apple negotiating with one of the major cell carriers to allow free calls between members who maintain .Mac accounts and keep their data in Apple’s Address Book. A few of those sites also suggested that future products in the Shuffle line will combine random phone calling and music playing, allowing users to play random music for random phone contacts.

The iPhone Shuffle will be sold at Apple retail stores.

May 4, 2021

My podcasts of choice

As a follow-up to what I wrote earlier today, here are my own favorite podcasts, in the order they currently appear in my phone’s podcast apps:

Radio Open Source (from itself)Bill Simmons (on The Ringer)Fresh Air (from WHYY via NPR)JJ Reddick & Tommy Alter (from ThreeFourTwo)The Mismatch (on The Ringer)The New Yorker Radio Hour (WNYC via NPR)Econtalk (from itself)On the Media (WNYC)How I Built This with Guy Raz (from NPR)The Daily (from New York Times)Reimagining the Internet (from Ethan Zuckerman and UMass Amherst)Planet Money (from NPR)Up First (from NPR)Here’s the thing (WNYC via NPR)FLOSS Weekly (TWiT)Reality2.0 (from itself)Note that I can’t help listening to the last two, because I host one and co-host the other.

There are others I’ll listen to on occasion as well, usually after hearing bits of them on live radio. These include Radiolab, This American Life, 99% Invisible, Snap Judgement, Freakonomics Radio, Hidden Brain, Invisibilia, The Moth, Studio 360. Plus limited run podcasts, such as Serial, S-Town, Rabbit Hole and Floodlines.

Finally, there are others I intend to listen to at some point, such as Footnoting History, Philosophize This, The Infinite Monkey Cage, Stuff You Should Know, The Memory Palace, and Blind Spot.

And those are just off the top of my head. I’m sure there are others I’m forgetting.

Anyway, most of the time I’d rather listen to those than live radio—even though I am a devoted listener to a raft of public stations (especially KCLU, KPCC, KCRW, KQED, WNYC, WBUR and WGBH) and too many channels to mention on SiriusXM, starting with Howard Stern and the NBA channel.

A half-century of NPR

NPR, which turned 50 yesterday, used to mean National Public Radio. It still does, at least legally; but in 2010. The reason given was “…most of our audience — more than 27 million listeners to NPR member stations and millions more who experience our content on NPR.org and through mobile or tablet devices — identify us as NPR.” Translation: We’re not just radio any more.

NPR, which turned 50 yesterday, used to mean National Public Radio. It still does, at least legally; but in 2010. The reason given was “…most of our audience — more than 27 million listeners to NPR member stations and millions more who experience our content on NPR.org and through mobile or tablet devices — identify us as NPR.” Translation: We’re not just radio any more.

And they aren’t. Nor are television, newspapers and magazines. All of those are now experienced mostly on glowing rectangles connected to the Internet. Put another way, the Internet is assimilating all of them. On the Internet, radio is also fracturing into new and largely (though not entirely) different spawn. The main two are streaming (for music, live news and events) and podcasting (for talk and news).

Thus the broadcast sources called stations are being obsolesced. Think about it: how much these days do you ask yourself “What’s on?” And how much do you listen to an actual radio, or watch TV through an antenna? Do you even have a radio that’s not in a car, or stored away in a drawer or a box in the garage?

If you value and manage your time, chances are your own usage of what used to be broadcasting is moving to apps that allow you to store and forward your listening and viewing to later times, when you can easily speed up the program or skip over ads and other “content” you don’t want to “consume.” (I put those in quotes because only the supply side talks that way about what they produce and what you do with it.)

Over the last few years I’ve been documenting the primary delivery mechanisms of radio and TV stations: their transmitters, towers and antennas. I do that because within a few decades, or perhaps just a few years, most or all of these will be as gone as horse-drawn carriages and steam engines. You can see a collection of those photos here and here.

The word station derives from the Latin station- and statio from stare, which means to stand. In a place.

In the terrestrial world, we needed stationary places for carriages, trains and busses to stop, and where, on what we used to call a “dial,” radio stations could be found. On dials these places were channels or frequencies.

But even those were being obsolesced decades ago in Europe, by a standard called RDS, which used a function called alternative frequency (AF) to make a radio play the station on whatever whichever of its more than one signals sounded best. But this only made sense when a station (especially a big national one, like BBC Radio 1, 2, 3 or 4) had many signals spread across the landscape.

The same thing would work in North America if here we didn’t deploy a lesser derivative standard called RDBS, which lacked the AF function. And NPR wouldn’t have wanted it anyway, because NPR is just a producer and distributor. Its customers are stations, and it has a vested interest in maintaining those.

This is working especially well in pandemic time.

In radio ratings for New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, San Diego, and dozens of other markets, the top news station is the NPR one. Here in Santa Barbara, about a quarter of all listening goes to non-commercial stations, led by KCLU, the most local of the NPR affiliates with transmitters here. (Best I can tell, Santa Barbara, which I wrote about here in 2019, is still the top market for public radio in the country. Number two is still Vermont.)

But I gotta wonder how long the station-based status quo will remain stationary in our listening habits. To the degree that I’m a one-person bellwether, the prospects aren’t good. Nearly all my listening these days is to podcasts or to streams on the Net. Some of those are from stations, but most are straight from producers, only one of which is NPR.

But I expect NPR to do well for decades to come. Its main challenge will be to survive the end of station-based live broadcasting. Because that eventuality is starting to become visible.

The gizmo at the top is the antenna of KPCC/89.3, the top news station for the Los Angeles market, and one of the top few overall. KPCC, an NPR affiliate, is only 600 watts: by far the weakest of the many other stations in the same location: atop 6000-foot Mt. Wilson, overlooking the vast population spread below. (Tops is the also non-commercial KPFK/90.7, which is 110,000 watts.)

May 2, 2021

On the persistence of KPIG

On Quora, William Moser asked, Would the KPIG radio format of Americana—Folk, Blugrass, Delta to modern Blues, Blues-rock, trad. & modern C&W, country & Southern Rock, jam-bands, singer/songwriters, some jazz, big-band & jazz-singers sell across markets in America?

I answered,

I’ve liked KPIG since its prior incarnation as KFAT.I’ve liked KPIG since its prior incarnation as KFAT.

It’s a great fit in the Santa Cruz-Salinas-Monterey market, anchored in Santa Cruz, which is a college/beach/hippie/artist kind of town.

Ratings have always been good, putting it in the top few. See here.

It has also done okay in San Luis Obispo, for similar reasons.

For what it’s worth, those are markets #91 and #171. Similar in a coastal California kind of way.

The station is also a throwback, with its commitment to being the institution it is, with real personalities who actually live there, aren’t leaving, and having a sense of humor about all of it. Also love. And listener participation. None of that is a formula.

Watch this and you’ll get what I mean. It’s what all of radio ought to be, in its own local ways, and way too little of it is.

William replied,

I have played tha brilliant ‘Ripple’ since it was released; the editing is spot-on.I have played tha brilliant ‘Ripple’ since it was released; the editing is spot-on.

With respect to DJ personalities, there are at least two that, in my fantasy of owning that station, would be gone before the ink was dry. (You might even have an idea of whom). Paradoxically, that’s probably part of what makes KPIG work.

It’s really the cross-country market appeal of the ‘Americana’ music format that is my question.

My response:

I think it’s a local thing. KPIG (and KFAT and KHIP before it) is a deeply rooted local institution. It’s not a formula, and without standing one up in some other region like it, and funding it long enough to see if it catches on, it’s hard to say.

All of radio is in decline now, as talk listening moves to podcasts and music listening moves to streaming. The idea that a city or a region needs things called “stations,” all with limited geographical coverage, and with live talent performing, and an obligation to stay on the “air” 24/7, designed to work through things called “radios,” which are no longer sold in stores and persist as secondary functions on car dashboards, is an anachronism at a time when damn near everything (including chat, telephony, video, photography, gaming, fitness tracking and you-name-it) is moving onto phones—which are the most persistently personal things people carry everywhere.

There are truly great alternative stations, however, that thrive in their markets: KESP in Seattle and WWOZ in New Orleans are two great examples. That KPIG manages to persist as a commercial station is especially remarkable in a time when people would rather hit a 30-second skip-forward button on their phone app than listen to an ad.

So I guess my answer is no. But if you want Americana, there are lots of stations that play or approximate it on the Internet. And all of them can be received on your phone or your computer.

That was a bit tough to write, because yesterday I was poised to enjoy Ron Phillips‘ long-standing Saturday morning show on WWOZ when I learned he had died suddenly of a heart attack. Ron has been a great friend since the 1970s, when he was a mainstay at WQDR in Raleigh, and I was a partner in its ad agency (while still at cross-market non-rival WDBS), and I had planned to give him a call after his show, to see how he was doing. (He’d had carpal tunnel surgery recently.)

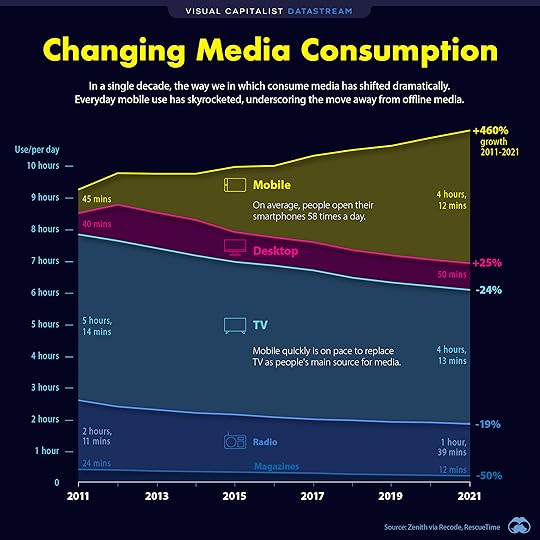

Though WWOZ is alive and thriving, and there persist many radio stations that are vital institutions in their towns and regions, radio on the whole has been in decline. See here:

The slopes there are long, and a case can be made, on that low angle alone, that radio will persist forever, along with magazines and TV. But it’s clear that our media usage is moving, overall, to the Internet, where mobile devices are especially good at doing what radio, TV and magazines also do—and in some ways doing it better.

But back to William Moser’s question.

There are already many ways to stream Americana (aka American roots music) on the Internet, whether from stations, streaming services like Spotify, Pandora, or a channel or two on SiriusXM. But those are largely personality-free.

What KPIG has (once described to me as “mutant cowboy rock & roll”) isn’t a format. It’s an institution, like a favorite old tavern, music club, outdoor festival, or coffee shop—or all of those rolled into one. Can one replicate that with an Internet station, or a channel on some global service?

I think not, because those services are all global. You need to start with local roots. WWOZ has that, because it started as a radio station in New Orleans, a place that is itself deeply rooted. After years of living all over the place, Ron moved to New Orleans to be with those roots, and near its greatest radio voice.

Radio is geographical. All the stations I mentioned above, living and dead, are not the biggest ones in their towns. KPIG’s signal is almost notoriously minimal. So is KEXP’s in Seattle. They are local in the most basic sense.

I suppose that condition will persist for another decade or two. But it’s hard to say. Mobile devices are also evolving quickly, getting old within just a few years.

I’m not sure we’ll miss it much, the succession of generations being what it is. But we are losing something. And you can still hear it on KPIG.

March 16, 2021

How anywhere is everywhere

On Quora, somebody asked, Which is your choice, radio, television, or the Internet?. I replied with the following.

If you say to your smart speaker “Play KSKO,” it will play that small-town Alaska station, which has the wattage of a light bulb, anywhere in the world. In this sense the Internet has eaten the station. But many people in rural Alaska served by KSKO and its tiny repeaters don’t have Internet access, so the station is either their only choice, or one of a few. So we use the gear we have to get the content we can.

TV viewing is also drifting from cable to à la carte subscription services (Netflix, et. al.) delivered over the Internet, in much the same way that it drifted earlier from over-the-air to cable. And yet over-the-air is still with us. It’s also significant that most of us get our Internet over connections originally meant only for cable TV, or over cellular connections originally meant only for telephony.

Marshall and Eric McLuhan, in Laws of Media, say every new medium or technology does four things: enhance, retrieve, obsolesce and reverse. (These are also caled the Tetrad of Media Effects.) And there are many answers in each category. For example, the Internet—

enhances content delivery;retrieves radio, TV and telephone technologies;obsolesces over-the-air listening and viewing;reverses into tribalism;—among many other effects within each of those.

The McLuhans also note that few things get completely obsolesced. For example, there are still steam engines in the world. Some people still make stone tools.

It should also help to note that the Internet is not a technology. At its base it’s a protocol—TCP/IP—that can be used by a boundless variety of technologies. A protocol is a set of manners among things that compute and communicate. What made the Internet ubiquitous and all-consuming was the adoption of TCP/IP by things that compute and communicate everywhere in the world.

This development—the worldwide adoption of TCP/IP—is beyond profound. It’s a change as radical as we might have if all the world suddenly spoke one common language. Even more radically, it creates a second digital world that coexists with our physical one.

In this digital world, we are at a functional distance apart of zero. We also have no gravity. We are simply present with each other. This means the only preposition that accurately applies to our experience of the Internet is with. Because we are not really on or through or over anything. Those prepositions refer to the physical world. The digital world is some(non)thing else.

This is why referring to the Internet as a medium isn’t quite right. It is a one-of-one, an example only of itself. Like the Universe. That you can broadcast through the Internet is just one of the countless activities it supports. (Even though the it is not an it in the material sense.)

I think we are only at the beginning of coming to grips with what it all means, besides a lot.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers