Doc Searls's Blog, page 38

January 11, 2021

How we save the world

Let’s say the world is going to hell. Don’t argue, because my case isn’t about that. It’s about who saves it.

I suggest everybody. Or, more practically speaking, a maximized assortment of the smartest and most helpful anybodies.

Not governments. Not academies. Not investors. Not charities. Not big companies and their platforms. Any of those can be involved, of course, but we don’t have to start there. We can start with people. Because all of them are different. All of them can learn. And teach. And share. Especially since we now have the Internet.

To put this in a perspective, start with Joy’s Law: “No matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else.” Then take Todd Park‘s corollary: “Even if you get the best and the brightest to work for you, there will always be an infinite number of other, smarter people employed by others.” Then take off the corporate-context blinders, and note that smart people are actually far more plentiful among the world’s customers, readers, viewers, listeners, parishioners, freelancers and bystanders.

Hundreds of millions of those people also carry around devices that can record and share photos, movies, writings and a boundless assortment of other stuff. Ways of helping now verge on the boundless.

We already have millions (or billions) of them are reporting on everything by taking photos and recording videos with their mobiles, obsolescing journalism as we’ve known it since the word came into use (specifically, around 1830). What matters with the journalism example, however, isn’t what got disrupted. It’s how resourceful and helpful (and not just opportunistic) people can be when they have the tools.

Because no being is more smart, resourceful or original than a human one. Again, by design. Even identical twins, with identical DNA from a single sperm+egg, can be as different as two primary colors. (Examples: Laverne Cox and M. Lamar. Nicole and Jonas Maines.)

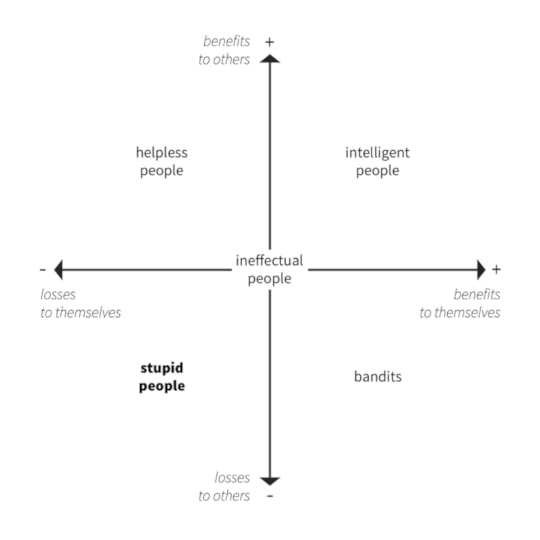

Yes, there are some wheat/chaff distinctions to make here. To thresh those, I dig Carlo Cipolla‘s Basic Laws on Human Stupidity (.pdf here) which stars this graphic:

The upper right quadrant has how many people in it? Billions, for sure.

I’m counting on them.

If we didn’t have the Internet, I wouldn’t.

Bonus links: Cluetrain, New Clues, Customer Commons.)

And a big HT to my old buddy Julius R. Ruff, Ph.D., for turning me on to Cipolla.

December 27, 2020

We’ve seen this movie before

When some big outfit with a vested interest in violating your privacy says they are only trying to save small business, grab your wallet. Because the game they’re playing is misdirection away from what they really want.

The most recent case in point is Facebook, which ironically holds the world’s largest database on individual human interests while also failing to understand jack shit about personal boundaries.

This became clear when Facebook placed the ad above and others like it in major publications recently, and mostly made bad news for itself. We saw the same kind of thing in early 2014, when the IAB ran a similar campaign against Mozilla, using ads like this:

That one was to oppose Mozilla’s decision to turn on Do Not Track by default in its Firefox browser. Never mind that Do Not Track was never more than a polite request for websites to do what so far the GDPR and the CCPA are still mostly failing to make them do, which is track you like a marked animal everywhere you go after leaving their premises. (But, credit where due: the GDPR and the CCPA have at least forced websites to put up insincere and misleading opt-out popovers in front of every website whose lawyers are scared of violating the letter—but never the spirit—of those and other privacy laws.)

The IAB succeeded, effectively defeating Do Not Track as well. But the IAB’s victory was Pyrrhic, because users decided to install ad blockers instead, which by 2015 led to the largest boycott in human history. We also got the GDPR, the CCPA and other privacy laws.

Not quite finally, we got Apple on our side. That’s good, but not good enough.

What we need are working tools of our own. Examples: Global Privacy Control (and all the browsers and add-ons mentioned there), Customer Commons‘ #NoStalking term, the IEEE’s P7012 – Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, and other approaches to solving business problems from the our side—rather than always from the corporate one.

In those movies, we’ll win.

Because if only Apple wins, we still lose.

Dammit, it’s still about what The Cluetrain Manifesto said in the first place, in this “one clue” published almost 21 years ago:

we are not seats or eyeballs or end users or consumers.

we are human beings — and out reach exceeds your grasp.

deal with it.

We have to make them deal. All of them. Not just Apple. We need code, protocols and standards, and not just regulations.

All the projects linked to above can use some help, plus others I’ll list here too if you write to me with them. (Comments here only work for Harvard email addresses, alas. I’m doc at searls dot com.)

December 26, 2020

Wonder What?

Our Christmas evening of cinematic indulgence was watching Wonder Woman 1984, about which I just posted this, elsewhere on the Interwebs:

Our Christmas evening of cinematic indulgence was watching Wonder Woman 1984, about which I just posted this, elsewhere on the Interwebs:

I mean, okay, all “super” and “enhanced” hero (and villain) archetypes are impossible. Not found in nature. You grant that. After a few thousand episodes in the various franchises, one’s disbelief becomes fully suspended. So when you’ve got an all-female island of Amazons (which reproduce how?… by parthenogenesis?) playing an arch-Freudian Greco-Roman Quidditch, you say hey, why not? We’re establishing character here. Or backstory. Or something. You can hang with it, long as there are a few connections to what might be a plausible reality, and while things move forward in a sensible enough way. And some predictability counts. For example, you know the young girl, this movie’s (also virgin-birthed) Anakin Skywalker, is sure to lose the all but endless Quidditch match, and will learn in losing a lesson (taught by … who is that? Robin Wright? Let’s check on one of our phones) that will brace the front end of what turns out at the end of the story to be its apparent moral arc.

And then the girl is an introverted scientist-supermodel who hasn’t aged since WWI (an item that hasn’t raised questions with HR since long before it was called “Personnel,” and we later learn has been celibate or something ever since her only-ever boyfriend died sixty-four years ago while martyring his ass in a plane crash you’re trying to remember from the first movie) has suddenly decided, after all this time, to start fighting crime with her magic lasso and her ability to leap shopping mall atria in a single bound; and then, after same boyfriend inexplicably comes back from the dead to body-snatch some innocent dude, they go back to hugging and smooching and holding hands like the intervening years of longing (her) and void (him) were no big deals, and then they jack an idle (and hopefully gassed up) F18 Hornet, which in reality doesn’t have pilot-copilot seats side-by-side (or even a co-pilot, beging a single-seat plane), and which absolutely requires noise-isolating earphones this couple doesn’t have, because afterburner noise in the cockpit in one of those mothers is about 2000db, and the undead boyfriend, who flew a Fokker or something in the prior movie, knows exactly and how to fly a jet that only the topmost of guns are allowed to even fantasize about, and then he and Wondermodel have a long conversation on a short runway during which they’re being chased by cops, she kinda doubts that one of the gods in her polytheistic religion have given her full powers to make a whole plane invisible to radar, which she has to explain to her undead dude exists now in 1984 (because he wouldn’t know about that, even though he knows everything else about the plane), and the last thing she actually made disappear was a paper cup, and then they somehow have a romantic flight, without refueling, from D.C. to a dirt road in an orchard somewhere near Cairo, while in the meantime the most annoying and charmless human being in human history—a supervillain-for-now whose one human power was selling self-improvement on TV—causes a giant wall to appear in the middle of a crowded city while apparently not killing anyone… Wholly shit.

And what I just described was about three minutes in the midst of this thing.

But we hung with it, in part because we were half-motivated to see if it was possible to tally both the impossibilities and plot inconsistencies of the damn thing. By the time it ended, we wondered if it ever would.

December 23, 2020

A simple suggestion for Guilford College

Guilford College made me a pacifist.

This wasn’t hard, under the circumstances. My four years there were the last of the 1960s, a stretch when the Vietnam War was already bad and getting much worse. Nonviolence was also a guiding principle of the civil rights movement, which was very active and local at the time, and pulled me in as well. I was also eligible for the draft if I dropped out. Risk of death has a way of focusing one’s mind.

As a Quaker college, this was also Guilford’s job. Hats off: I got a fine education there. Learned a lot, and enjoyed every second I was there.

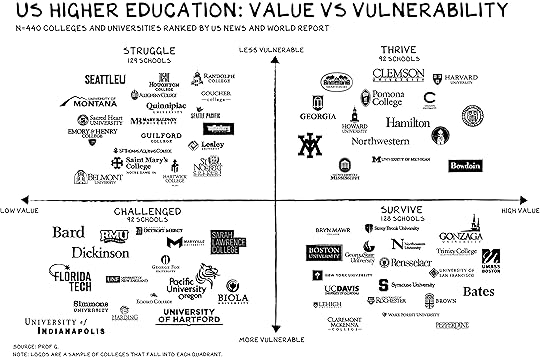

These days, however, Guilford—like lots of other colleges and universities—is in trouble. Scott Galloway and his research team at NYU do a good job of sorting out every U.S. college’s troubles here:

You’ll find Guilford in the “Struggle” quadrant, top left. That one contains “Tier-2 schools with one or more comorbidities, such as high admit rates (anemic waiting lists), high tuition, or scant endowments.”

So I’d like to help Guilford, but not (yet) with the money they constantly ask me for. Instead, I have some some simple advice: teach peace. Become the pacifist college. There’s a need for that, and the position is open. A zillion other small liberal arts colleges do what Guilford does. (Run a global search and replace replacing “Guilford” with any other good small liberal arts college and it’ll work for them all.)But none of the others teach peace, or wrap the rest of their curricular offerings around that simple and straightforward purpose.

Any institution can change in a zillion different ways. The one thing it can’t change is where it comes from. Staying true to that is one of the strongest, most high-integrity things a college can do. By positioning around peace and pacifism, Guilford aligns with its origins and stands alone in a field that will inevitably grow—if our species is to survive and thrive in an overcrowded and rapidly changing world.

True, Quakers started a bunch of other colleges and universities (twenty by this count). And they include some pretty big names: Cornell, Bryn Mawr, Haverford, Johns Hopkins. But none are positioned on peace and pacifism. And maybe only a few could be. Among those known as well as Guilford, I’d say Earlham for sure. Maybe Wilmington. Anyway, the position is open, and I think Guilford should take it.

Fortuitously, a few days ago I got an email from Ed Winslow, chair of Guilford’s Board of Trustees, that began with this paragraph:

The Board of Trustees met on Dec. 15 to consider the significant feedback we have received and for a time of discernment. In that spirit, we have asked President Moore to pause implementation of the program prioritization while the Board continues to listen and gather input from those of you who wish to offer it. We are hearing particularly from alumni who are offering fundraising ideas. We are also hearing internally and from those in the wider education community who are offering ideas as well.

So that’s my idea for focusing the college itself: own the Peace Position.

For fundraising I have another idea that I understand is implemented by a few other universities (I’m told that Kent State is one): tell alumni you’re done asking for money constantly and instead ask only to be included in their wills. I know this is contrary to most fundraising advice; but I believe it will work—and does, for some schools. Think about it: just knowing emails from one’s alma mater aren’t almost always shakedowns for cash is a giant benefit.

But my main advice here is about positioning Guilford.

And, in case anyone at Guilford wonders who the hell I am and why my advice ought to carry some weight, forgive me while I waive vanity and present these two facts: 1) I was a success in the marketing business (much of it doing positioning) for much of my long professional life; and 2) I’m tops on the notable Guilford alumni list in search results. I even beat fellow alums Howard Coble, Tom Zachary, M.L. Carr, Bob Kauffman and World B. Free. Yes, all of those guys are more deserving; but there it is. Eat my dust.

And peace, y’all.

December 15, 2020

Social shell games

If you listen to Episode 49: Parler, Ownership, and Open Source of the latest Reality 2.0 podcast, you’ll learn that I was blindsided at first by the topic of Parler, which has lately become a thing. But I caught up fast, even getting a Parler account not long after the show ended. Because I wanted to see what’s going on.

If you listen to Episode 49: Parler, Ownership, and Open Source of the latest Reality 2.0 podcast, you’ll learn that I was blindsided at first by the topic of Parler, which has lately become a thing. But I caught up fast, even getting a Parler account not long after the show ended. Because I wanted to see what’s going on.

Though self-described as “the world’s town square,” Parler is actually a centralized social platform built for two purposes: 1) completely free speech; and 2) creating and expanding echo chambers.

The second may not be what Parler’s founders intended (see here), but that’s how social media algorithms work. They group people around engagements, especially likes. (I think, for our purposes here, that algorithmically nudged engagement is a defining feature of social media platforms as we understand them today. That would exclude, for example, Wikipedia or a popular blog or newsletter with lots of commenters. It would include, say, Reddit and Linkedin, because algorithms.)

Let’s start with recognizing that the smallest echo chamber in these virtual places is our own, comprised of the people we follow and who follow us. Then note that our visibility into other virtual spaces is limited by what’s shown to us by algorithmic nudging, such as by Twitter’s trending topics.

The main problem with this is not knowing what’s going on, especially inside other echo chambers. There are also lots of reasons for not finding out. For example, my Parler account sits idle because I don’t want Parler to associate me with any of the people it suggests I follow, soon as I show up:

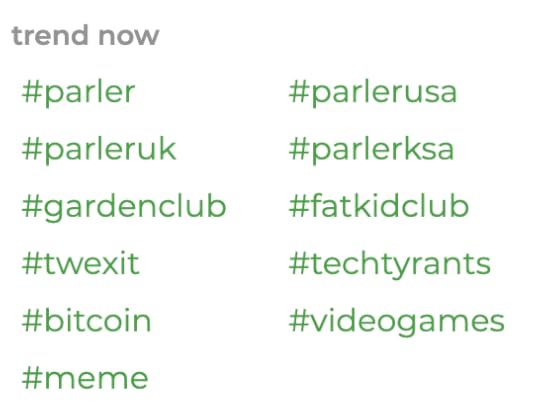

l also don’t know what to make of this, which is the only other set of clues on the index page:

Especially since clicking on any of them brings up the same or similar top results, which seem to have nothing to do with the trending # topic. Example:

Thus endeth my research.

But serious researchers should be able to see what’s going on inside the systems that produce these echo chambers, especially Facebook’s.

The problem is that Facebook and other social networks are shell games, designed to make sure nobody knows exactly what’s going on, but feels okay with it, because they’re hanging with others who agree on the basics.

The design principle at work here is obscurantism—”the practice of deliberately presenting information in an imprecise, abstruse manner designed to limit further inquiry and understanding.”

To put the matter in relief, consider a nuclear power plant:

Nothing here is a mystery. Or, if there is one, professional inspectors will be dispatched to solve it. In fact, the whole thing is designed from the start to be understandable, and its workings accountable to a dependent public.

Now look at a Facebook data center:

What it actually does is pure mystery, by design, to those outside the company. (And hell, to most, maybe all, of the people inside the company.) No inspector arriving to look at a rack of blinking lights is going to know either. What Facebook looks like to you, to me, to anybody, is determined by a pile of discoveries, both on and off of Facebook’s site and app, around who you are and what to machines you seem interested in, and an algorithmic process that is not accountable to you, and impossible for anyone, perhaps including Facebook itself, to fully explain.

All societies, and groups within societies, are echo chambers. And, because they cohere in isolated (and isolating) ways it is sometimes hard for societies to understand each other, especially when they already have prejudicial beliefs about each other. Still, without the further influence of social media, researchers can look at and understand what’s going on.

Over in the digital world, which overlaps with the physical one, we at least know that social media amplifies prejudices. But, though it’s obvious by now that this is what’s going on, doing something to reduce or eliminate the production and amplification of prejudices is damn near impossible when the mechanisms behind it are obscure by design.

This is why I think these systems need to be turned inside out, so researchers can study them. I don’t know how to make that happen; but I do know there is nothing more large and consequential in the world that is also absent of academic inquiry. And that ain’t right.

BTW, if Facebook, Twitter, Parler or other social networks actually are opening their algorithmic systems to academic researchers, let me know and I’ll edit this piece accordingly.

December 14, 2020

Be the hawk

On Quora the question went, If you went from an IQ of 135+ to 100, how would it feel?

Here’s how I answered::::

I went through that as a kid, and it was no fun.

In Kindergarten, my IQ score was at the top of the bell curve, and they put me in the smart kid class. By 8th grade my IQ score was down at the middle of the bell curve, my grades sucked, and my other standardized test scores (e.g. the Iowa) were terrible. So the school system shunted me from the “academic” track (aimed at college) to the “general” one (aimed at “trades”).

To the school I was a failure. Not a complete one, but enough of one for the school to give up on aiming me toward college. So, instead of sending me on to a normal high school, they wanted to send me to a “vocational-technical” school where boys learned to operate machinery and girls learned “secretarial” skills.

But in fact the school failed me, as it did countless other kids who adapted poorly to industrialized education: the same industrial system that still has people believing IQ tests are a measure of anything other than how well somebody answers a bunch puzzle questions on a given day.

Fortunately, my parents believed in me, even though the school had given up. I also believed in myself, no matter what the school thought. Like Walt Whitman, I believed “I was never measured, and never will be measured.” Walt also gifted everyone with these perfect lines (from Song of Myself):

I know I am solid and sound.

To me the converging objects of the universe

perpetually flow.

All are written to me,

and I must get what the writing means…

I know this orbit of mine cannot be swept

by a carpenter’s compass,

I know that I am august,

I do not trouble my spirit to vindicate itself

or be understood.

I see that the elementary laws never apologize.

Whitman argued for the genius in each of us that moves in its own orbit and cannot be encompassed by industrial measures, such as standardized tests that serve an institution that would rather treat students like rats in their mazes than support the boundless appetite for knowledge with which each of us is born—and that we keep if it doesn’t get hammered out of us by normalizing systems.

It amazes me that half a century since I escaped from compulsory schooling’s dehumanizing wringer, the system is largely unchanged. It might even be worse. (“Study says standardized testing is overwhelming nation’s public schools,” writes The Washington Post.)

To detox ourselves from belief in industrialized education, the great teacher John Taylor Gatto gives us The Seven Lesson Schoolteacher, which summarizes what he was actually paid to teach:

Confusion — “Everything I teach is out of context. I teach the un-relating of everything. I teach disconnections. I teach too much: the orbiting of planets, the law of large numbers, slavery, adjectives, architectural drawing, dance, gymnasium, choral singing, assemblies, surprise guests, fire drills, computer languages, parents’ nights, staff-development days, pull-out programs, guidance with strangers my students may never see again, standardized tests, age-segregation unlike anything seen in the outside world….What do any of these things have to do with each other?”

Class position — “I teach that students must stay in the class where they belong. I don’t know who decides my kids belong there but that’s not my business. The children are numbered so that if any get away they can be returned to the right class. Over the years the variety of ways children are numbered by schools has increased dramatically, until it is hard to see the human beings plainly under the weight of numbers they carry. Numbering children is a big and very profitable undertaking, though what the strategy is designed to accomplish is elusive. I don’t even know why parents would, without a fight, allow it to be done to their kids. In any case, again, that’s not my business. My job is to make them like it, being locked in together with children who bear numbers like their own.”

Indifference — “I teach children not to care about anything too much, even though they want to make it appear that they do. How I do this is very subtle. I do it by demanding that they become totally involved in my lessons, jumping up and down in their seats with anticipation, competing vigorously with each other for my favor. It’s heartwarming when they do that; it impresses everyone, even me. When I’m at my best I plan lessons very carefully in order to produce this show of enthusiasm. But when the bell rings I insist that they stop whatever it is that we’ve been working on and proceed quickly to the next work station. They must turn on and off like a light switch. Nothing important is ever finished in my class, nor in any other class I know of. Students never have a complete experience except on the installment plan. Indeed, the lesson of the bells is that no work is worth finishing, so why care too deeply about anything?

Emotional dependency — “By stars and red checks, smiles and frowns, prizes, honors and disgraces I teach kids to surrender their will to the predestined chain of command. Rights may be granted or withheld by any authority without appeal, because rights do not exist inside a school — not even the right of free speech, as the Supreme Court has ruled — unless school authorities say they do. As a schoolteacher, I intervene in many personal decisions, issuing a pass for those I deem legitimate, or initiating a disciplinary confrontation for behavior that threatens my control. Individuality is constantly trying to assert itself among children and teenagers, so my judgments come thick and fast. Individuality is a contradiction of class theory, a curse to all systems of classification.”

Intellectual dependency — “Good people wait for a teacher to tell them what to do. It is the most important lesson, that we must wait for other people, better trained than ourselves, to make the meanings of our lives. The expert makes all the important choices; only I, the teacher, can determine what you must study, or rather, only the people who pay me can make those decisions which I then enforce… This power to control what children will think lets me separate successful students from failures very easily.

Provisional self-esteem — “Our world wouldn’t survive a flood of confident people very long, so I teach that your self-respect should depend on expert opinion. My kids are constantly evaluated and judged. A monthly report, impressive in its provision, is sent into students’ homes to signal approval or to mark exactly, down to a single percentage point, how dissatisfied with their children parents should be. The ecology of “good” schooling depends upon perpetuating dissatisfaction just as much as the commercial economy depends on the same fertilizer.

No place to hide — “I teach children they are always watched, that each is under constant surveillance by myself and my colleagues. There are no private spaces for children, there is no private time. Class change lasts three hundred seconds to keep promiscuous fraternization at low levels. Students are encouraged to tattle on each other or even to tattle on their own parents. Of course, I encourage parents to file their own child’s waywardness too. A family trained to snitch on itself isn’t likely to conceal any dangerous secrets. I assign a type of extended schooling called “homework,” so that the effect of surveillance, if not that surveillance itself, travels into private households, where students might otherwise use free time to learn something unauthorized from a father or mother, by exploration, or by apprenticing to some wise person in the neighborhood. Disloyalty to the idea of schooling is a Devil always ready to find work for idle hands. The meaning of constant surveillance and denial of privacy is that no one can be trusted, that privacy is not legitimate.”

Gatto won multiple teaching awards because he refused to teach any of those lessons. I succeeded in life by refusing to learn them as well.

All of us can succeed by forgetting those seven lessons—especially the one teaching that your own intelligence can be measured by anything other than what you do with it.

You are not a number. You are a person like no other. Be that, and refuse to contain your soul inside any institutional framework.

More Whitman:

Long enough have you dreamed contemptible dreams.

Now I wash the gum from your eyes.

You must habit yourself to the dazzle of the light and of every moment of your life.

Long have you timidly waited,

holding a plank by the shore.

Now I will you to be a bold swimmer,

To jump off in the midst of the sea, and rise again,

and nod to me and shout,

and laughingly dash your hair.

I am the teacher of athletes.

He that by me spreads a wider breast than my own

proves the width of my own.

He most honors my style

who learns under it to destroy the teacher.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then. I contradict myself.

I am large. I contain multitudes.

I concentrate toward them that are nigh.

I wait on the door-slab.

Who has done his day’s work

and will soonest be through with his supper?

Who wishes to walk with me.

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me.

He complains of my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed. I too am untranslatable.

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

Be that hawk.

December 9, 2020

Is Flickr in trouble again?

I have two Flickr accounts, named Doc Searls and Nfrastructure. One has 73,355 photos, and the other 3,469. They each cost $60/year to maintain as pro accounts. They’ve both renewed automatically in the past; and the first one is already renewed, which I can tell because it says “Your plan will automatically renew on March 20, 2022.”

The second one, however… I dunno. Because, while my Account page says “Your plan will automatically renew on December 13, 2020,” I just got emails for both accounts saying, “This email is to confirm that we have stopped automatic billing for your subscription. Your subscription will continue to be active until the expiration date listed below. At that time, you will have to manually renew or your subscription will be cancelled.” The dates match the two above. At the bottom of each, in small print, it says “Digital River Inc. is the authorized reseller and merchant of the products and services offered within this store. Privacy Policy Terms of Sale Your California Privacy Rights.”

Hmmm. The Digital River link goes here, which appears to be in Ireland. A look at the email’s source shows the mail server is one in Kansas, and the Flickr.com addressing doesn’t look spoofed. So, it doesn’t look too scammy to me. Meaning I’m not sure what the scam is. Yet. If there is one.

Meanwhile, I do need to renew the subscription, and the risk of not renewing it is years of contributions (captions, notes, comments) out the window.

So I went to “Manage your Pro subscription” on the second one (which has four days left to expiration), and got this under “Update your Flickr Pro subscription information”

Plan changes are temporarily disabled. Please contact support for prompt assistance.

Cancel your subscription

The Cancel line is a link. I won’t click on it.

Now, I have never heard of a company depending on automatic subscription renewals switching from those to the manual kind. Nor have I heard of a subscription-dependent company sending out notices like these while the renewal function is disabled.

I would like to contact “customer support”; but there is no link for that on my account page. In fact, the words “customer” and “support” don’t appear there. “Help” does, however, and goes to https://help.flickr.com/, where I need to fill out a form. This I did, explaining,

I am trying to renew manually, but I get “Plan changes are temporarily disabled. Please contact support for prompt assistance.” So here I am. Please reach out. This subscription expires in four days, and I don’t want to lose the photos or the account. I’m [email address] for this account (I have another as well, which doesn’t renew until 2022), my phone is 805-705-9666, and my twitter is @dsearls. Thanks!

The robot replied,

Thanks for your message – you’ll get a reply from a Flickr Support Hero soon. If you don’t receive an automated message from Flickr confirming we received your message (including checking your spam folders), please make sure you provided a valid and active email. Thanks for your patience and we look forward to helping you!

Me too.

Meanwhile, I am wondering if Flickr is in trouble again.

I wondered about this in 2011 and again in 2016, (in my most-read Medium post, ever). Those were two of the (feels like many) times Flickr appeared to be on the brink. And I have been glad SmugMug took over the Flickr show in 2018. (I’m a paying SmugMug customer as well.) But this kind of thing is strange and has me worried. Should I be?

(Comments here only work for Harvard people; so if you’re not one of those, please reply elsewhere, such as on Twitter, where I’m @dsearls.)

November 8, 2020

We’re in the epilogue now

The show is over. Biden won. Trump lost.

Sure, there is more to be said, details to argue. But the main story—Biden vs. Trump, the 2020 Presidential Election, is over. So is the Trump presidency, now in the lame duck stage.

We’re in the epilogue now.

There are many stories within and behind the story, but this was the big one, and it had to end. Enough refs calling it made the ending official. President Trump will continue to fight, but the outcome won’t change. Biden will be the next president. The story of the Trump presidency will end with Biden’s inauguration.

The story of the Biden presidency began last night. Attempts by Trump to keep the story of his own presidency going will be written in the epilogue, heard in the coda, the outro, the postlude.

Fox News, which had been the Trump administration’s house organ, concluded the story when it declared Biden the winner and moved on to covering him as the next president.

This is how stories go.

This doesn’t mean that the story was right in every factual sense. Stories aren’t.

As a journalist who has covered much and has been covered as well, I can vouch for the inevitability of inaccuracy, of overlooked details, of patches, approximations, compressions, misquotes and summaries that are more true to story, arc, flow and narrative than to all the facts involved, or the truths that might be told.

Stories have loose ends, and big stories like this one have lots of them. But they are ends. And The End is here.

We are also at the beginning of something new that isn’t a story, and does not comport with the imperatives of journalism: of storytelling, of narrative, of characters with problems struggling toward resolutions.

What’s new is the ground on which all the figures in every story now stand. That ground is digital. Decades old at most, it will be with us for centuries or millennia. Arriving on digital ground is as profound a turn in the history of our species on Earth as the one our distant ancestors faced when they waddled out of the sea and grew lungs to replace their gills.

We live in the digital world now now, in addition to the physical one where I am typing and you are reading, as embodied beings.

In this world we are not just bodies. We are something and somewhere else, in a place that isn’t a place: one without distance or gravity, where the only preposition that applies without stretch or irony is with. (Because the others—over, under, beside, around, though, within, upon, etc.—pertain too fully to positions and relationships in the physical world.)

Because the digital world is ground and not figure (here’s the difference), it is as hard for us to make full sense of being there as it was for the first fish to do the same with ocean or for our amphibian grandparents to make sense of land. (For some help with this, dig David Foster Wallace’s This is water.)

The challenge of understanding digital life will likely not figure in the story of Joe Biden’s presidency. But nothing is more important than the ground under everything. And this ground is the same as the one without which we would not have had an Obama or a Trump presidency. It will at least help to think about that.

November 4, 2020

How the once mighty fall

For many decades, one of the landmark radio stations in Washington, DC was WMAL-AM (now re-branded WSPN), at 630 on (what in pre-digital times we called) the dial. As AM listening faded, so did WMAL, which moved its talk format to 105.9 FM in Woodbridge and its signal to a less ideal location, far out to the northwest of town.

They made the latter move because the 75 acres of land under the station’s four towers in Bethesda had become far more valuable than the signal. So, like many other station owners with valuable real estate under legacy transmitter sites, Cumulus Media, sold sold the old site for $74 million. Nice haul.

I’ve written at some length about this here and here in 2015, and here in 2016. I’ve also covered the whole topic of radio and its decline here and elsewhere.

I only bring the whole mess up today because it’s a five-year story that ended this morning, when WMAL’s towers were demolished. The Washington Post wrote about it here, and provided the video from which I pulled the screen-grab above. Pedestrians.org also has a much more complete video on YouTube, here. WRC-TV, channel 4, has a chopper view (best I’ve seen yet) here. Spake the Post,

When the four orange and white steel towers first soared over Bethesda in 1941, they stood in a field surrounded by sparse suburbs emerging just north of where the Capital Beltway didn’t yet exist. Reaching 400 feet, they beamed the voices of WMAL 630 AM talk radio across the nation’s capital for 77 years.

As the area grew, the 75 acres of open land surrounding the towers became a de facto park for runners, dog owners and generations of teenagers who recall sneaking smokes and beer at “field parties.”

Shortly after 9 a.m. Wednesday, the towers came down in four quick controlled explosions to make way for a new subdivision of 309 homes, taking with them a remarkably large piece of privately owned — but publicly accessible — green space. The developer, Toll Brothers, said construction is scheduled to begin in 2021.

Local radio buffs say the Washington region will lose a piece of history. Residents say they’ll lose a public play space that close-in suburbs have too little of.

After seeing those towers fall, I posted this to a private discussion among broadcast engineers (a role I once played, briefly and inexpertly, many years ago):

It’s like watching a public execution.

I’m sure that’s how many of who have spent our lives looking at and maintaining these things feel at a sight like this.

It doesn’t matter that the AM band is a century old, and that nearly all listening today is to other media. We know how these towers make waves that spread like ripples across the land and echo off invisible mirrors in the night sky. We know from experience how the inverse square law works, how nulls and lobes are formed, how oceans and prairie soils make small signals large and how rocky mountains and crappy soils are like mud in a strong signal’s wheels. We know how and why it is good to know these things, because we can see an invisible world where other people only hear songs, talk and noise.

We also know that, in time, all these towers are going away, or repurposed to hold up antennas sending and receiving radio frequencies better suited for carrying data.

We know that everything ends, and in that respect AM radio is no different than any other medium.

What matters isn’t whether it ends with a bang (such as here with WMAL’s classic towers) or with a whimper (as with so many other stations going dark or shrinking away in lesser facilities). It’s that there’s still some good work and fun in the time this old friend still has left.

October 22, 2020

On KERI: a way not to reveal more personal info than you need to

You don’t walk around wearing a name badge. Except maybe at a conference, or some other enclosed space where people need to share their names and affiliations with each other. But otherwise, no.

You don’t walk around wearing a name badge. Except maybe at a conference, or some other enclosed space where people need to share their names and affiliations with each other. But otherwise, no.

Why is that?

Because you don’t need a name badge for people who know you—or for people who don’t.

Here in civilization we typically reveal information about ourselves to others on a need-to-know basis: “I’m over 18.” “I’m a citizen of Canada.” “Here’s my Costco card.” “Hi, I’m Jane.” We may or may not present credentials in these encounters. And in most we don’t say our names. “Michael” being a common name, a guy called “Mike” may tell a barista his name is “Clive” if the guy in front of him just said his name is “Mike.” (My given name is David, a name so common that another David re-branded me Doc. Later I learned that his middle name was David and his first name was Paul. True story.)

This is how civilization works in the offline world.

Kim Cameron wrote up how this ought to work, in Laws of Identity, first published in 2004. The Laws include personal control and consent, minimum disclosure for a constrained use, justifiable parties, and plurality of operators. Again, we have those in here in the offline world where your body is reading this on a screen.

In the online world behind that screen, however, you have a monstrous mess. I won’t go into why. The results are what matter, and you already know those anyway.

Instead, I’d like to share what (at least for now) I think is the best approach to the challenge of presenting verifiable credentials in the digital world. It’s called KERI, and you can read about it here: https://keri.one/. If you’d like to contribute to the code work, that’s here: https://github.com/decentralized-identity/keri/.

I’m still just getting acquainted with it, in sessions at IIW. The main thing is that I’m sure it matters. So I’m sharing that sentiment, along with those links.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers