Doc Searls's Blog, page 34

December 28, 2021

Wayne Thiebaud, influencer

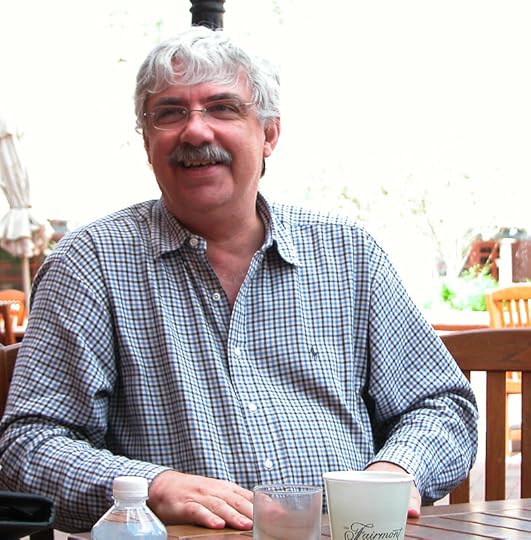

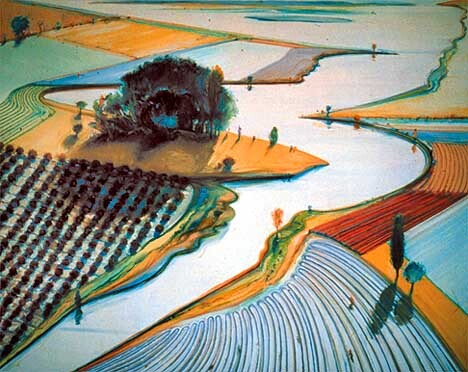

Just learned Wayne Thiebaud died, at 101. I didn’t know he was still alive. But I did know he had a lot of influence, most famously on pop art. Least famously, on me.

Many of Thiebaud’s landscapes were from aerial perspectives. For example, this—

—and this:

In me, those influenced this—

In me, those influenced this—

—and this—

—and this—

—and this—

—and this—

—and this—

—and this—

—and even this:

Like Thiebaud, I love the high angle on the easily overlooked, and opportunity for revelations not obtainable from the ground, or in the midst.

Example. Can you guess where these mountains are?

Try Los Angeles. I shot that, as I did the others in this album, during the approach to LAX on a flight from Houston.

Here’s another shot in that series:

That’s 10,068-foot Mt. San Antonio, aka Old Baldy, highest of the San Gabriel Mountains, which wall the north side of the L.A. basin, thwarting northward sprawl. The view is up San Antonio Canyon, with a series debris catch basins at the base of the canyon, separated as terraces to sort rocks rolling down the canyon.

Since these mountains are geologically new, and formed where the Pacific Plate grinds against the North American one, the mountains are heaps of loose rock that are rolling and sliding down almost as fast as the mountains are going up. Hence the catch basins.

Anyway, while there is Thiebaud-informed art to that shot, there is also purpose. I want people to see how these mountains are as alive as an active volcano.

My main influence toward that purpose is John McPhee, the best nonfiction writer ever to walk the Earth—and report on it. Dig Los Angeles Against the Mountains. Doesn’t get better than that.

McPhee is 90 now. I dread losing him.

December 21, 2021

Rage in Peace

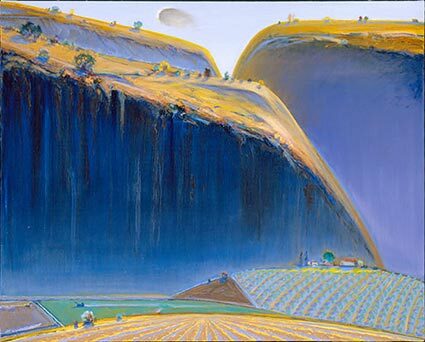

The Cluetrain Manifesto had four authors but one voice, and that was Chris Locke‘s.

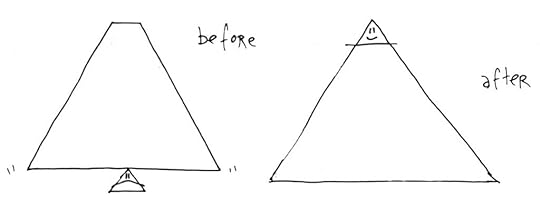

Cluetrian, a word that didn’t exist before Chris (aka RageBoy), David Weinberger, Rick Levine and I made it up during a phone conversation in early 1999 (and based it on a joke about a company that didn’t get clues delivered by train four times a day), is now tweeted constantly, close to 23 years later. (And by now belongs in the OED.) Our conversational foursome might not have had a material outcome had Chris not emailed this little graphic to the other three of us:

After we got that, we had to put up the Cluetrain website. And then we had to expand that site into a book, thanks to the viral outbreak of interest that followed a column about the site—and Chris especially, face and all—in The Wall Street Journal. A great enemy of marketing-as-usual, nobody was better than Chris at spreading a word.

Alas, Chris died yesterday, after a long struggle with COPD. (Too much smoke, for too long. Got my dad and my old pal Ray too. That it’s becoming unfashionable is a grace of our time.)

You know how, when two people are first getting to know each other, they exchange stories about parts of their lives? It’s hard to top Chris’s. For example, I remember telling Chris that my parents were frontier types who met in Alaska. But, while I thought that might take us down an interesting story hole, Chris blasted open a bigger one of his own: “My father was a priest and my mother was a nun.”

Once, when I missed a plane from SFO to meet Chris in Denver, I mentioned that I was standing next to a strangely wide glass wall at my just-vacated gate in Terminal 1. “I know that gate well,” he said. “And that glass is a trip. I once missed a plane there myself while I was on acid and got totally into that glass wall.” I don’t remember what he said after that, except that it was outrageous (for anyone but Chris) and I couldn’t stop laughing as his story went on.

Good God, what a great writer he was. Try Winter Solstice. One pull-quote: “We learn to love the lie we must tell ourselves to survive.”

Among too many stories to count, here is one I hope his soul forgives me for lifting from a thread on Facebook:

on this Father’s Day I am recalling getting drunk with MY dad on Christmas Eve 1968, as was our custom back then (this month I am 34 years sober). he told me he was suicidal and i knew he meant it. so I turned him on to acid there and then. it was a bit of a rocky trip, but things were better for him after that.

btw, when the trip got really rough, I tricked him into thinking he could fall asleep. “If you want to come down, just take six of these big bomber multivitamin pills and that’ll be it.” fat chance! but he fell sound asleep. as I sat next to him marveling at the sound of guardian angel wings softly beating over us, THE PHONE RANG!!! OMG. at like 4am! and worse, it was my judgmental hyper-Catholic MOTHER!! she said…

hello, is your father over there

….yes… I said.

are you two taking LSD?

oh no! had she gone psychic??

….yes… I said, fearful of what was coming next.

THANK GOD, she said. SOMETHING had to give.

and then:

“well, have a good trip,” she said, and rang off.

I have more to say, but not enough time right now. (Holiday stuff calls.) So I’ll leave you with this, also from Chris, in Cluetrain:

And remember the man who said it.

And remember the man who said it.

December 6, 2021

The gentle lawgiver

This is about credit where due, and unwanted by the credited. In this case I speak of Kim Cameron, who passed last week and I remembered fondly in the last post.

What I want to celebrate now is how an open and generous person in a giant company can use its power for good, and not play the heavy doing it. That’s how Kim worked for two decades while he was the top architect of Microsoft approach to digital identity. I first saw this at work at the inaugural meeting of a group that called itself the Identity Gang.

That name was given to the crew by Steve Gillmor, who hosted a Gillmor Gang podcast (here’s the audio) on the topic of digital identity, the last day of 2004. To follow that up, seven of the nine people in that podcast, plus about as many more, gathered during a break at Esther Dyson‘s PC Forum conference in Scottsdale, Arizona, on March 20, 2005. Here is an album of photos I shot of the Gang, sitting around an outside table.

Kim was the most powerful participant, owing both to his position at Microsoft and having issued, one by one, his Seven Laws of Identity, over the preceding months.

The next time the Identity Gang met was in October of that year, in Berkeley. By then the gang had grown to about a hundred people. Organized by Kaliya Young, Phil Windley and myself (but mostly those other two), the next meeting was branded Internet Identity Workshop (IIW), and it has been held every Fall and Spring since then at the Computer History Museum (and, in pandemic time, online), with hundreds, from all over the world, participating every time.

I’m biased by my involvement with it, but I do believe IIW is the most essential and productive conference of any kind. Conversations and developments of many kinds are moved forward at every one of them.

I am also sure that progress made around digital identity would not be the same (or as advanced) without Kim Cameron’s strong and gentle guidance. Hats off to his spirit and his legacy—especially those laws.

December 3, 2021

Remembering Kim Cameron

Got word yesterday that Kim Cameron had passed.

Hit me hard. Kim was a loving and loved friend. He was also a brilliant and influential thinker and technologist.

That’s Kim, above, speaking at the 2018 EIC conference in Germany. His topics were The Laws of Identity on the Blockchain and Informational Self-Determination in a Post Facebook/Cambridge Analytica Era (in the Ownership of Data track).

The laws were seven:

User control and consentMinimum disclosure for a constrained useJustifiable partiesDirected identity (meaning pairwise, known only to the person and the other party)Pluralism of operatorsHuman integrationConsistent experience across contextsHe wrote these in 2004, when he was still early in his tenure as Microsoft’s chief architect for identity (one of several similar titles he held at the company). Perhaps more than anyone at Microsoft—or at any big company—Kim pushed constantly toward openness, inclusivity, compatibility, cooperation, and the need for individual agency and scale. His laws, and other contributions to tech, are still only beginning to have full influence. Kim was way ahead of his time, and its a terrible shame that his own is up. He died of cancer on November 30.

But Kim was so much more—and other—than his work. He was a great musician, teacher (in French and English), thinker, epicure, traveler, father, husband, and friend. As a companion, he was always fun, as well as curious, passionate, caring, gracious.

I am reminded of what a friend said of Amos Tversky, another genius of seemingly boundless vitality who died too soon: “Death is unrepresentative of him.”

That’s one reason it’s hard to think of Kim in the past tense, and why I resisted the urge to update Kim’s Wikipedia page earlier today. (Somebody has done that now, I see.)

We all get our closing parentheses. I’ve gone longer without closing mine than Kim did before closing his. That also makes me sad, not that I’m in a hurry. Being old means knowing you’re in the exit line, but okay with others cutting in. I just wish this time it wasn’t Kim.

Britt Blaser says life is like a loaf of bread. It’s one loaf no matter how many slices are in it. Some people get a few slices, others many. For the sake of us all, I wish Kim had more.

Here is an album of photos of Kim, going back to 2005 at Esther Dyson’s PC Forum, where we had the first gathering of what would become the Internet Identity Workshop, the 34th of which is coming up next Spring. As with many other things in the world, it wouldn’t be the same—or here at all—without Kim.

November 7, 2021

On using Wikipedia in schools

In Students are told not to use Wikipedia for research. But it’s a trustworthy source, Rachel Cunneen and Mathieu O’Niel nicely unpack their case for the headline. In a online polylogue in response to that piece, I wrote,

“You always have a choice: to help or to hurt.” That’s what my mom told me, a zillion years ago. It applies to everything we do, pretty much.

The purpose of Wikipedia is to help. Almost entirely, it does. It is a work of positive construction without equal or substitute. That some use it to hurt, or to spread false information, does not diminish Wikipedia’s worth as a resource.

The trick for researchers using Wikipedia as a resource is not a difficult one: don’t cite it. Dig down in references, make sure those are good, and move on from there. It’s not complicated.

Since that topic and comment are due to slide down into the Web’s great forgettery (where Google searches do not go), I thought I’d share it here.

November 1, 2021

Going west

Long ago a person dear to me disappeared for what would become eight years. When this happened I was given comfort and perspective by his maternal grandfather, a professor of history whose study concentrated on the American South after the Civil War.

“You know what the most common record of young men was, after the Civil War?” he asked.

“You mean census records?”

“Yes, and church records, family histories, all that.”

“I don’t know.”

“Two words: Went west.”

He went on to explain that that, except for the natives here in the U.S., nearly all of our ancestors had gone west. Literally or metaphorically, voluntarily or not, they went west.

More importantly, most were not going back. Many, perhaps most, were hardly heard from again in the places they left. The break from the past in countless places was sadly complete for those left behind. All that remained were those two words.

Went west.

This fact, he said, is at the heart of American rootlessness.

“We are the least rooted civilization on Earth,” he said. “This is why we have weaker family values than any other country.”

This is also why he also thought political talk about “family values” was especially ironic. We may have those values, but they tend not to keep us from going west anyway.

This comes to mind because I am haunted by Harry Chapin‘s song, “Cat’s in the Cradle.” It’s hard not to be moved by it.

October 15, 2021

On solving the worldwide shipping crisis

The worldwide shipping crisis is bad. Here are some reasons:

To wrap one’s head around all of those (and more), it might help to start with Aristotle’s four “causes” (which might also be translated as “explanations”). Wikipedia illustrates these with a wooden dining table:

Its material cause is wood.Its efficient cause is carpentry.Its final cause is dining.Its formal cause (what gives it form) is design.Of those, formal cause is what matters most. That’s because, without knowledge of what a table is, it wouldn’t get made.

But the worldwide supply chain (which is less a single chain than braided rivers spreading outward from many sources through countless deltas) is impossible to reduce to any one formal cause. Mining, manufacturing, harvesting, shipping on sea and land, distribution, wholesale and retail sales are all involved, and specialized in their own ways, dependencies withstanding.

I suggest, however, that the most formal of the supply chain problem’s causes is also what’s required to sort out and solve it: digital technology and the Internet. From What does the Internet make of us?, sourcing the McLuhans:

“People don’t want to know the cause of anything”, Marshall said (and Eric quotes, in Media and Formal Cause). “They do not want to know why radio caused Hitler and Gandhi alike. They do not want to know that print caused anything whatever. As users of these media, they wish merely to get inside…”

We are all inside a digital environment that is making each of us while also making our systems. This can’t be reversed. But it can be improved.

One way might be to build ways to fully (or at least adequately) comprehend whole systems that subsume and transcend the scope and interests of any part, whether those parts be truckers, laws, standards, or whatever. Global aviation has some of this, but it’s also a much simpler system than the braided rivers between global supply and demand.

Is there something like that? I don’t yet know. Closest I’ve found is the UN’s IMO (International Maritime Organizaiton), and that only covers “the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine and atmospheric pollution by ships.” Not very encompassing, that. If any of ya’ll know more, fill us in.

By the way, Heather Cox Richardson (whose newsletter I highly recommend) yesterday summarized what the Biden administration is trying to do about all this:

Biden also announced today a deal among a number of different players to try to relieve the supply chain slowdowns that have built up as people turned to online shopping during the pandemic. Those slowdowns threaten the delivery of packages for the holidays, and Biden has pulled together government officials, labor unions, and company ownership to solve the backup.

The Port of Los Angeles, which handles 40% of the container traffic coming into the U.S., has had container ships stuck offshore for weeks. In June, Biden put together a Supply Chain Disruption Task Force, which has hammered out a deal. The port is going to begin operating around the clock, seven days a week. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union has agreed to fill extra shifts. And major retailers, including Walmart, FedEx, UPS, Samsung, Home Depot, and Target, have agreed to move quickly to clear their goods out of the dock areas, speeding up operations to do it and committing to putting teams to work extra hours.

“The supply chain is essentially in the hands of the private sector,” a White House official told Donna Littlejohn of the Los Angeles Daily News, “so we need the private sector…to help solve these problems.” But Biden has brokered a deal among the different stakeholders to end what was becoming a crisis.

Hopefully helpful, but not sufficient.

Bonus link: a view of worldwide marine shipping. (Zoom in and out, and slide in any direction for a great way to spend some useful time.)

October 4, 2021

Where the Intention Economy Beats the Attention Economy

There’s an economic theory here: Free customers are more valuable than captive ones—to themselves, to the companies they deal with, and to the marketplace. If that’s true, the intention economy will prove it. If not, we’ll stay stuck in the attention economy, where the belief that captive customers are more valuable than free ones prevails.

Let me explain.

The attention economy is not native to human attention. It’s native to businesses that seek to grab and manipulate buyers’ attention. This includes the businesses themselves and their agents. Both see human attention as a “resource” as passive and ready for extraction as oil and coal. The primary actors in this economy—purveyors and customers of marketing and advertising services—typically talk about human beings not only as mere “users” and “consumers,” but as “targets” to “acquire,” “manage,” “control” and “lock in.” They are also oblivious to the irony that this is the same language used by those who own cattle and slaves.

While attention-grabbing has been around for as long as we’ve had yelling, in our digital age the fields of practice (abbreviated martech and adtech) have become so vast and varied that nobody (really, nobody) can get their head around everything that’s going on in them. (Examples of attempts are here, here and here.)

One thing we know for sure is that martech and adtech rationalize taking advantage of absent personal privacy tech in the hands of their targets. What we need there are the digital equivalents of the privacy tech we call clothing and shelter in the physical world. We also need means to signal our privacy preferences, to obtain agreements to those, and to audit compliance and resolve disputes. As it stands in the attention economy, privacy is a weak promise made separately by websites and services that are highly incentivised not to provide it. Tracking prophylaxis in browsers is some help, but itworks differently for every browser and it’s hard to tell what’s actually going on.

Another thing we know for sure is that the attention economy is thick with fraud, malware, and worse. For a view of how much worse, look at any adtech-supported website through PageXray and see the hundreds or thousands of ways sthe site and its invisible partners are trying to track you. (For example, here’s what Smithsonian Magazine‘s site does.)

We also know that lawmaking to stop adtech’s harms (e.g. GDPR and CCPA) has thus far mostly caused inconvenience for you and me (how many “consent” notices have interrupted your web surfing today?)—while creating a vast new industry devoted to making tracking as easy as legally possible. Look up GDPR+compliance and you’ll get way over 100 million results. Almost all of those will be for companies selling other companies ways to obey the letter of privacy law while violating its spirit.

Yet all that bad shit is also a red herring, misdirecting attention away from the inefficiencies of an economy that depends on unwelcome surveillance and algorithmic guesswork about what people might want.

Think about this: even if you apply all the machine learning and artificial intelligence in the world to all the personal data that might be harvested, you still can’t beat what’s possible when the targets of that surveillance have their own ways to contact and inform sellers of what they actually want and don’t want, plus ways to form genuine relationships and express genuine (rather than coerced) loyalty, and to do all of that at scale.

We don’t have that yet. But when we do, it will be an intention economy. Here are the opening paragraphs of The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012):

This book stands with the customer. This is out of necessity, not sympathy. Over the coming years, customers will be emancipated from systems built to control them. They will become free and independent actors in the marketplace, equipped to tell vendors what they want, how they want it, where and when—even how much they’d like to pay—outside of any vendor’s system of customer control. Customers will be able to form and break relationships with vendors, on customers’ own terms, and not just on the take-it-or-leave-it terms that have been pro forma since Industry won the Industrial Revolution.

Customer power will be personal, not just collective. Each customer will come to market equipped with his or her own means for collecting and storing personal data, expressing demand, making choices, setting preferences, proffering terms of engagement, offering payments and participating in relationships—whether those relationships are shallow or deep, and whether they last for moments or years. Those means will be standardized. No vendor will control them.

Demand will no longer be expressed only in the forms of cash, collective appetites, or the inferences of crunched data over which the individual has little or no control. Demand will be personal. This means customers will be in charge of personal information they share with all parties, including vendors.

Customers will have their own means for storing and sharing their own data, and their own tools for engaging with vendors and other parties. With these tools customers will run their own loyalty programs—ones in which vendors will be the members. Customers will no longer need to carry around vendor-issued loyalty cards and key tags. This means vendors’ loyalty programs will be based on genuine loyalty by customers, and will benefit from a far greater range of information than tracking customer behavior alone can provide.

Thus relationship management will go both ways. Just as vendors today are able to manage relationships with customers and third parties, customers tomorrow will be able to manage relationships with vendors and fourth parties, which are companies that serve as agents of customer demand, from the customer’s side of the marketplace.

Relationships between customers and vendors will be voluntary and genuine, with loyalty anchored in mutual respect and concern, rather than coercion. So, rather than “targeting,” “capturing,” “acquiring,” “managing,” “locking in” and “owning” customers, as if they were slaves or cattle, vendors will earn the respect of customers who are now free to bring far more to the market’s table than the old vendor-based systems ever contemplated, much less allowed.

Likewise, rather than guessing what might get the attention of consumers—or what might “drive” them like cattle—vendors will respond to actual intentions of customers. Once customers’ expressions of intent become abundant and clear, the range of economic interplay between supply and demand will widen, and its sum will increase. The result we will call the Intention Economy.

This new economy will outperform the Attention Economy that has shaped marketing and sales since the dawn of advertising. Customer intentions, well-expressed and understood, will improve marketing and sales, because both will work with better information, and both will be spared the cost and effort wasted on guesses about what customers might want, and flooding media with messages that miss their marks. Advertising will also improve.

The volume, variety and relevance of information coming from customers in the Intention Economy will strip the gears of systems built for controlling customer behavior, or for limiting customer input. The quality of that information will also obsolete or re-purpose the guesswork mills of marketing, fed by crumb-trails of data shed by customers’ mobile gear and Web browsers. “Mining” of customer data will still be useful to vendors, though less so than intention-based data provided directly by customers.

In economic terms, there will be high opportunity costs for vendors that ignore useful signaling coming from customers. There will also be high opportunity gains for companies that take advantage of growing customer independence and empowerment.

But this hasn’t happened yet. Why?

Let’s start with supply and demand, which is roughly about price. Wikipedia: “the relationship between the price of a given good or product and the willingness of people to either buy or sell it.” But that wasn’t the original idea. “Supply and demand” was first expressed as “demand and supply” by Sir James Denham-Steuart in An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Oeconomy, written in 1767. To Sir James, demand and supply wasn’t about price. Specifically, “it must constantly appear reciprocal. If I demand a pair of shoes, the shoemaker either demands money or something else for his own use.” Also, “The nature of demand is to encourage industry.”

Nine years later, in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith, a more visible bulb in the Scottish Enlightenment, wrote, “The real and effectual discipline which is exercised over a workman is that of his customers. It is the fear of losing their employment which restrains his frauds and corrects his negligence.” Again, nothing about price.

But neither of those guys lived to see the industrial age take off. When that happened, demand became an effect of supply, rather than a cause of it. Supply came to run whole markets on a massive scale, with makers and distributors of goods able to serve countless customers in parallel. The industrial age also ubiquitized standard-form contracts of adhesion binding all customers to one supplier with a single “agreement.”

But, had Sir James and Adam lived into the current millennium, they would have seen that it is now possible, thanks to digital technologies and the Internet, for customers to achieve scale across many companies, with efficiencies not imaginable in the pre-digital industrial age.

For example, it should be possible for a customer to express her intentions—say, “I need a stroller for twins downtown this afternoon”—to whole markets, but without being trapped inside any one company’s walled garden. In other words, not only inside Amazon, eBay or Craigslist. This is called intentcasting, and among its virtues is what Kim Cameron calls “minimum disclosure for constrained purposes” to “justifiable parties” through a choice among a “plurality of operators.”

Likewise, there is no reason why websites and services can’t agree to your privacy policy, and your terms of engagement. In legal terms, you should be able to operate as the first party, and to proffer your own terms, to which sites and services can agree (or, as privacy laws now say, consent) as second parties. That this is barely thinkable is a legacy of a time that has sadly not yet left us: one in which only companies can enjoy that kind of scale. Yet it would clearly be a convenience to have privacy as normalized in the online world as it is in the offline one. But we’re slowly getting there; for example with Customer Commons’ P2B1, aka #NoStalking term, which readers can proffer and publishers can agree agree to. It says “Just give me ads not based on tracking me.” Also with the IEEE’s P7012 Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms working group.

Same with subscriptions. A person should be able to keep track of all her regular payments for subscription services, to keep track of new and better deals as they come along, to express to service providers her intentions toward those new deals, and to cancel or unsubscribe. There are lots of tools for this today, for example Truebill, Bobby, Money Dashboard, Mint, Subscript Me, BillTracker Pro, Trim, Subby, Card Due, Sift, SubMan, and Subscript Me. There are also subscription management systems offered by Paypal, Amazon, Apple and Google (e.g. with Google Sheets and Google Doc templates). But all of them to one degree or another are based more on the felt need by those suppliers for customer captivity than for customer independence.

As Customer Commons unpacks it here, there are many largely or entirely empty market spaces that are wide open for free and independent customers: identity, shopping (e.g. with shopping carts of your own to take from site to site), loyalty (of the genuine kind), property ownership (the real Internet of Things), and payments, for example.

It is possible to fill all those spaces if we have the capacity to—as Sir James put it—encourage industry, restrain fraud and correct negligence. While there is some progress in some of those areas, the going is still slow on the global scale. After all, The Intention Economy is nine years old and we still don’t have it yet. Is it just not possible, or are we starting in the wrong places?

I think it’s the latter.

Way back in 1995, when the Internet first showed up on both of our desktops, my wife Joyce said, “The sweet spot of the Internet isn’t global. It’s local.” That was the gist of my TEDx Santa Barbara talk in 2018. It’s also why Joyce and I are now in Bloomington, Indiana, working with the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University on deploying a new way for demand and supply to inform each other and get business rolling—and to start locally. It’s called the Byway, and it works outside of the old supply-controlled industrial model. Here’s an FAQ. Please feel free to add questions in the comments here.

The title image is by the great Hugh Macleod, and was commissioned in 2004 for a startup he and I both served and is now long gone.

September 9, 2021

The Matrix 4.0

The original Matrix is my favorite movie. Not because I think it’s the best. I just think it’s the most important. Also among the most rewatchable. (Hear that, Ringer? Rewatch the whole series before Christmas.)

And now the fourth movie in the series is coming out: The Matrix Resurrections. Here’s the @TheMatrixMovie‘s new pinned tweet of the first trailer.

Yeah, it’s a sequel, and sequels tend to sag. Even The Godfather Part 2. (But that one only sagged in the relative sense, since the original was perfect.)

If anything bothers me about this next Matrix it’s that what was seemed an untouchable Classic is now a Franchise. Not a bad beast, the Franchise. Just different: same genus, different species.

Given the way these things go, my expectations are low and my hopes high.

Meanwhile, I’m wondering why Laurence Fishburn, Hugo Weaving, and Lilly Wachowski don’t return in Resurrections. Not being critical here. Just curious.

Bonus link: a must-see from 2014.

Also, from my old blog in 2003,

William Blaze has an interesting take on the political agenda of The Matrix Franchise.

My own thoughts about the original Matrix (that it was a metaphor for marketing, basically) are here, here and here.†

That was back when blogging was blogging. Which it will be again, at least for some of us, when Dave Winer is finished rebooting the practice with Drummer.

† I know those two links are duplicates, but don’t have the time to hunt down the originals. And Google is no help, because it ignores lots of old material.

September 8, 2021

Is there a way out of password hell?

Passwords are hell.

Worse, to make your hundreds of passwords safe as possible, they should be nearly impossible for others to discover—and for you to remember.

Unless you’re a wizard, this all but requires using a password manager.†

Think about how hard that job is. First, it’s impossible for developers of password managers to do everything right:

Most of their customers and users need to have logins and passwords for hundreds of sites and services on the Web and elsewhere in the networked worldEvery one of those sites and services has its own gauntlet of methods for registering logins and passwords, and for remembering and changing themEvery one of those sites and services has its own unique user interfaces, each with its own peculiaritiesAll of those UIs change, sometimes often.Keeping up with that mess while also keeping personal data safe from both user error and determined bad actors, is about as tall as an order can get. And then you have to do all that work for each of the millions of customers you’ll need if you’re going to make the kind of money required to keep abreast of those problems and providing the solutions required.

So here’s the thing: the best we can do with passwords is the best that password managers can do. That’s your horizon right there.

Unless we can get past logins and passwords somehow.

And I don’t think we can. Not in the client-server ecosystem that the Web has become, and that industry never stopped being, since long before the Internet came along. That’s the real hell. Passwords are just a symptom.

We need to work around it. That’s my work now. Stay tuned here, here, and here for more on that.

† We need to fix that Wikipedia page.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers