Doc Searls's Blog, page 33

April 10, 2022

What’s up with Dad?

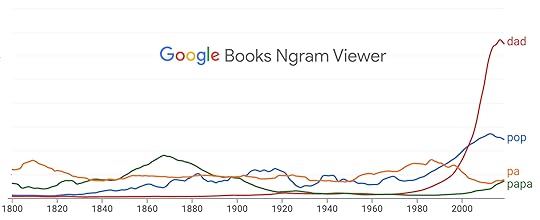

My father was always Pop. He was born in 1908. His father, also Pop, was born in 1863. That guy’s father was born in 1809, and I don’t know what his kids called him. I’m guessing, from the chart above, it was Pa. My New Jersey cousins called their father Pop. Uncles and their male contemporaries of the same generation in North Carolina, however, were Dad or Daddy.

To my kids, I’m Pop or Papa. Family thing, again.

Anyway, I’m wondering what’s up, or why’s up, with Dad?

April 2, 2022

The Age of Optionality—and its costs

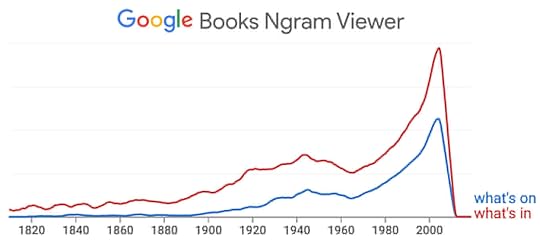

Throughout the entire history of what we call media, we have consumed its contents on producers’ schedules. When we wanted to know what was in newspapers and magazines, we waited until the latest issues showed up on newsstands, at our doors, and in our mailboxes. When we wanted to hear what was on the radio or to watch what was on TV, we waited until it played on our stations’ schedules. “What’s on TV tonight?” is perhaps the all-time most-uttered question about a medium. Wanting the answers is what made TV Guide required reading in most American households.

But no more. Because we have entered the Age of Optionality. We read, listen to, and watch the media we choose, whenever we please. Podcasts, streams, and “over the top” (OTT) on-edmand subscription services are replacing old-fashioned broadcasting. Online publishing is now more synchronous with readers’ preferences than with producers’ schedules.

The graph above illustrates what happened and when, though I’m sure the flat line at the right end is some kind of error on Google’s part. Still, the message is clear: what’s on and what’s in have become anachronisms.

The centers of our cultures have been held for centuries by our media. Those centers held in large part because they came on a rhythm, a beat, to which we all danced and on which we all depended. But now those centers are threatened or gone, as media have proliferated and morphed into forms that feed our attention through the flat rectangles we carry in our pockets and purses, or mount like large art pieces on walls or tabletops at home. All of these rectangles maximize optionality to degrees barely imaginable in prior ages and their media environments: vocal, scribal, printed, broadcast.

We are now digital beings. With new media overlords.

The Digital Markets Act in Europe calls these overlords “gatekeepers.” The gates they keep are at entrances to vast private walled gardens enclosing whole cultures and economies. Bruce Schneier calls these gardens feudal systems in which we are all serfs.

To each of these duchies, territories, fiefs, and countries, we are like cattle from which personal data is extracted and processed as commodities. Purposes differ: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Twitter, and our phone and cable companies each use our personal data in different ways. Some of those ways do benefit us. But our agency over how personal data is extracted and used is neither large nor independent of these gatekeepers. Nor do we have much if any control over what countless customers of gatekeepers do with personal data they are given or sold.

The cornucopia of options we have over the media goods we consume in these gardens somatizes us while also masking the extreme degree to which these private gatekeepers have enclosed the Internet’s public commons, and how algorithmic optimization of engagement at all costs has made us into enemy tribes. Ignorance of this change and its costs is the darkness in which democracy dies.

Shoshana Zuboff calls this development The Coup We Are Not Talking About. The subhead of that essay makes the choice clear: We can have democracy, or we can have a surveillance society, but we cannot have both. Her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, gave us a name for what we’re up against. A bestseller, it is now published in twenty-six languages. But our collective oblivity is also massive.

We plan to relieve some of that oblivity by having Shoshana lead the final salon in our Beyond the Web series at Indiana University’s Ostrom Workshop. To prepare for that, Joyce and I spoke with Shoshana for more than an hour and a half last night, and are excited about her optimism toward restoring the public commons and invigorating democracy in our still-new digital age. This should be an extremely leveraged way to spend an hour or more on April 11, starting at 2PM Eastern time. And it’s free.

Use this link to add the salon to your calendar and join in when it starts.

Or, if you’re in Bloomington, come to the Workshop and attend in person. We’re at 513 North Park Avenue.

March 30, 2022

Exitings

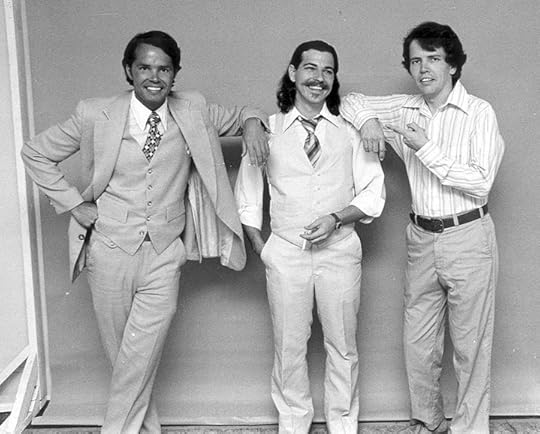

The photo above dates from early 1978, when Hodskins Simone & Searls, a new ad agency, was born in Durham, North Carolina. Specifically, at 602 West Chapel Hill Street. Click on that link and you’ll see the outside of our building. Perhaps you can imagine the scene above behind the left front window, because that’s where we stood, in bright diffused southern light. Left to right are David Hodskins, Ray Simone and me.

The photo above dates from early 1978, when Hodskins Simone & Searls, a new ad agency, was born in Durham, North Carolina. Specifically, at 602 West Chapel Hill Street. Click on that link and you’ll see the outside of our building. Perhaps you can imagine the scene above behind the left front window, because that’s where we stood, in bright diffused southern light. Left to right are David Hodskins, Ray Simone and me.

That scene, and the rest of my life, were bent toward all their possibilities by a phone call I made to Ray one day in 1976, when I was working as an occasionally employed journalist, advertising guy, comedy writer, radio voice and laborer: anything that paid. I didn’t yet know Ray personally, but I loved the comics he drew, and I wanted his art for an ad I had written for a local audio shop. So I called him at the “multiple media studio” where he was employed at the time. Before we got down to business, he also got into an off-phone conversation with another person in his office. After Ray told the other person he was on the phone with Doctor Dave (the comic radio persona by which I was widely known around those parts back then), the other person told Ray to book lunch with me at a restaurant downtown.

I got there first, so I was sitting down when Ray walked in with a guy who looked like an idealized version of me. This was the other person who worked with Ray, and who told Ray to propose the lunch. That’s how I met David Hodskins, who used the lunch to recruit me as a copywriter for the multiple media studio. I said yes, and after a few months of that, David decided the three of us should start Hodskins Simone & Searls. Four years and as many locations later, we had a building in Raleigh with dozens of people working for us, and were the top ad agency in the state specializing in tech and broadcasting.

But, after a client said “Y’know, guys, there’s more action on one street in Sunnyvale than there is in all of North Carolina,” David flew out to scout Silicon Valley. That resulted in a tiny satellite office in Palo Alto, where David prospected for business while running the Raleigh headquarters by phone and fax. After a year of doing that, David returned, convened a dinner with all the agency managers, and said we’d have to close Palo Alto if he didn’t get some help out there. This was in August, 1985.

To my surprise, I heard myself volunteering duty out there, even though a year earlier when David asked me to join him there I had said no. I’m not even sure why I volunteered this time. I loved North Carolina, had many friends there, and was well established as a figure in the community, mostly thanks to my Doctor Dave stuff. I said I just needed to make sure my kids, then 15 and 12, wanted to go. (I was essentially a single dad at the time.) After they said yes, we flew out and spent a week checking out what was for me an extremely exotic place. But the kids fell instantly in love with it. So I rented a house near downtown Palo Alto, registered the kids in Palo Alto junior and high schools, left them there with David, flew back to North Carolina, gave away everything that wouldn’t fit in a small U-Haul trailer, and towed my life to west in my new 145-horse ’85 Camry sedan with a stick shift. With my Mom along for company, we crossed the country in just four days.

The business situation wasn’t ideal. Silicon Valley was in a slump at that time. “For Lease “signs hung from new buildings all over the place. Commodore, Atari, and other temporary giants in the new PC industry were going down. Apple, despite the novelty of its new Macintosh computer, was in trouble. And ad agencies—more than 200 of them—were fighting for every possible account, new and old. Worse, except for David, me, and one assistant, our whole staff was three time zones east of there, and the Internet that we know today was decades away in the future. But we bluffed our way into the running for two of the biggest accounts in review.

As we kept advancing in playoffs for those two accounts, the North Carolina office was treading water and funds were running thin. In our final pitches, we were also up against the same incumbent agency: one that, at that time, was by far the biggest and best in the valley, and did enviably good work. So we were not the way to bet. The evening before our last pitch, David told Ray and me that we needed to win both accounts or retreat back to North Carolina. I told him that I was staying, regardless, because I belonged there, and so did my kids, one of whom was suddenly an academic achiever and the other a surfer who totally looked the part. We had gone native.

But we won both accounts, got a mountain of publicity for having come out of nowhere and kicked ass, and our Palo Alto office quickly outgrew our Raleigh headquarters. Within a year we closed Raleigh and were on our way to becoming one of the top tech agencies in Silicon Valley. None of this was easy, and all of it required maximal tenacity, coordination, and smarts, all of which were embodied in, and exemplified by, David Hodskins. He was wickedly smart, charismatic, tough, creative, and entrepreneurial: perfect for leading a small and rapidly growing company. While hard-driving and often overbearing (sometimes driving Ray and me nuts) he was also great fun to work and hang out with, and one of the best friends I’ve ever had.

One of the passions we shared was basketball. David was a severely loyal Duke alumnus and grandfathered with two season tickets every year to games at the Duke’s famous Cameron Indoor Stadium. I became a Duke fan as his date for dozens of games there. When we moved to Palo Alto, he and I got our basketball fix through season tickets to the Golden State Warriors. (In the late ’80s, this was still affordable for normal people.) At one point, we even came close once to winning the Warriors’ advertising business.

In the early 90s, I forked my own marketing consulting business out of HS&S, while remaining a partner with the firm until it was acquired by Publicis in 1998. By then I had also shifted back into journalism as an editor for Linux Journal, while also starting to blog. (Which I’m still doing right here.) David, Ray, and I remained good friends, however, while all three of us got married (Ray), remarried (David and I), and had California kids. In fact, I had met my wife with Ray’s help in 1990.

Ray died of lung cancer in 2011, at just 63. I remember him in this post here, and every day of my life.

On November 13 of last year, my wife and I attended the first game of the season for the Indiana Univesity Men’s basketball team, which David and I had rooted against countless times when they played Duke and other North Carolina teams. While there, I took a photo of the scene with my phone and sent it in an email to David, saying “Guess where I am?” He wrote back, “Looks suspiciously like Assembly Hall in Bloomington, Indiana, where liberals go to die. WTF are you doing there?”

I explained that Joyce and I were now visiting scholars at IU. He wrote back,

Mr. visiting scholar,

Recuperating from a one-week visit by (a friend) and his missus, before heading to Maui for T’giving week.

The unwelcome news is that I’m battling health issues on several fronts: GERD, Sleep Apnea, Chronic Fatigue, and severe abdominal pain. Getting my stomach scoped when I’m back from Maui, and hoping it isn’t stomach cancer.

Actual retirement is in sight… at the end of 2022. (Wife) hangs it up in February, 2024, so we’ll kick our travel plans into higher gear, assuming I’m still alive.

Already sick of hearing that coach K has “5 national titles, blah, blah, blah” but excited to see Paulo Banchero this year, and to see Jon Scheyer take the reins next year. Check out the drone work in this promotional video: https://youtu.be/Dp1dEadccGQ

Thanks for checking in, and glad to hear you’re keeping your brain(s) active. Please don’t become a Hoosier fan.

d

David’s ailment turned out to be ALS. After a decline too awful to describe, he died last week, on March 22nd. Two days earlier I sent him a video telling him that, among other things, he was the brother I never had and a massive influence on many of the lives that spun through his orbits. Unable to speak, eat or breathe on his own, he was at least able to smile at some of what I told him, and mouth “Wow” at the end.

And now there is just one left: the oldest and least athletic of us three. (Ray was a natural. And David actually played varsity basketball. Best I ever got was not being chosen last for my college dorm’s second floor south intramural team.)

I have much more to think, say, and write about David. But it’s hard because his being gone is completely out of character.

But not really, I suppose. Hemmingway:

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

My joke about aging is that I know I’m in the exit line, but I let others cut in. I just wish this time it hadn’t been David.

But the line does keep moving, while the world holds the door.

March 25, 2022

An arsonoma

While walking past this scene on my way to the subway in New York last week, I saw that a woman was emptying out what hadn’t burned from this former car. Being a curious extrovert, I paused to ask her about it. The conversation, best I recall:

“This your car?”

“Yeah.”

“I’m sorry. What happened?”

“Somebody around here sets fire to bags of garbage*. One spread to the car.”

“Any suspects?”

“There are surveillance cameras on the building.” She gestured upward toward two of them.

“Did they see anything?”

“They never do.”

So there you have it. In medicine they call this kind of thing a fascinoma. Perhaps in civic life we should call this an arsonoma. Or, in law enforcement, a felonoma.

*In New York City, we now put out garbage and recycling in curbside bags.

March 6, 2022

The frog of war

“Compared to war, all other forms of human endeavor shrink to insignificance. God help me, I do love it so.” — George S. Patton (in the above shot played by George C. Scott in his greatest role.)

Is the world going to croak?

Put in geological terms, will the Phanerozoic eon, which began with the Cambrian explosion a half billion years ago, end at the close of the Anthropocene epoch, when the human species, which has permanently put its mark on the Earth, commits suicide with nuclear weapons? This became a lot more plausible as soon as Putin rattled his nuclear saber.

Well, life will survive, even if humans do not. And that will happen whether or not the globe warms as much as the IPCC assures us it will. If heat in the climate of our current interglacial interval peaks with both poles free of ice, the Mississippi river will meet the Atlantic at what used to be St. Louis. And yet life will abound, as life tends to do, at least until the Sun gets so large and hot that photosynthesis stops and the phanerozoic finally ends. That time is about a half billion years away. That might seem like a long time, but given the age of the Earth itself—about 4.5 billion years—life here is much closer to the end than the beginning.

Let’s go back to human time.

I’ve been on the planet for almost 75 years, which in the grand scheme is a short ride. But it’s enough to have experienced history being bent some number of times. So far I count six.

First was on November 22, 1963, when John F. Kennedy was assassinated. This was when The Fifties actually ended and The Sixties began. (My great aunt Eva Quakenbush, née Searls or Searles—it was spelled both ways—told us what it was like when Lincoln was shot and she was 12 years old. “It changed everything,” she said. So did the JFK assassination.)

Second was the one-two punch of the Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy assassinations, on April 4 and June 6, 1968. The former was a massive setback for both the civil rights movement and nonviolence. And neither has fully recovered. The latter assured the election of Richard Nixon and another six years of the Vietnam war.

Third was the Internet, which began to take off in the mid-1990s. I date the steep start of hockey stick curve to April 30, 1995, when the last backbone within the Internet that had forbidden commercial traffic (NSFnet) shut down, uncorking a tide of e-commerce that is still rising.

Fourth was 9/11, in 2001. That suckered the U.S. into wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and repositioned the country from the world’s leading peacekeeper to the world’s leading war-maker.

Fifth was the Covid pandemic, which hit the world in early 2020 and is still with us, causing all sorts of changes, from crashes in supply chains to inflation to complete new ways for people to work, travel, vote, and think.

Sixth is the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began on February 24, 2022: just eleven days ago as I write this.

Big a thing as this last bend is—and it’s huge—there are too many ways to make sense of it all:

The global struggle between democracy and autocracyThe real End of HistoryAt last, EU gets it togetherPutin the warlordThe man is nutsZelensky the heroRussia about to collapse, maybeWWIIIUkraine will winHard to beat propagandaPutin’s turning Russia into

It’ll get worse before it ends badly while we all do more than nothing but not enoughWhatever it is, social media is reporting it allWorld War WiredRussia does not have an out

It’ll get worse before it ends badly while we all do more than nothing but not enoughWhatever it is, social media is reporting it allWorld War WiredRussia does not have an outI didn’t list the threat of thermonuclear annihilation among the six big changes in history I’ve experienced because I was raised with it. Several times a year we would “duck and cover” under our desks when the school would set off air raid sirens. Less frequent than fire drills, they were far more scary, because we all knew we were toast, being just five miles by air from Manhattan, which was surely in the programmed crosshairs on one or more Soviet nukes.

In fact I put so little faith in adult wisdom, or its collective expression in government choices, that I had a bucket list of places I’d like to see before blasts of nuclear fallout doomed us all. Two were the Grand Canyon and California, both exotic places for a kid whose farthest venturings from New Jersey were in North Carolina. (of no importance but of some possible interest is that I’ve been a citizen of California for 37 years, married to an Angelino for 32 of those, and it still seems exotic to me. Mountains next to cities? A tradition of wildfires? Here? Wow.)

But I’m an optimist, and if I have a provisional bottom line in this crisis, it’s that the bad guys can’t win World War Wired. Unless, that is, the worst guy ends things by killing the world.

March 3, 2022

Three thoughts about NFTs

There’s a thread in a list I’m on titled “NFTs are a Scam.” I know too little about NFTs to do more than dump here three thoughts I shared on the list in response to a post that suggested that owning digital seemed to be a mania of some kind. Here goes…

First, from Walt Whitman, who said he “could turn and live for awhile with the animals,” because,

They do not sweat and whine about their condition.

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins.

Not one is dissatisfied.

Not one is demented with the mania of owning things.

Second, the Internet is NEA, meaning,

No one owns it

Everyone can use it

Anyone can improve it

Kind of like the Universe that way.

What makes the Internet an inter-net is an agreement: that every network within it will pass packets from any one endpoint to any other, regardless of origin or destination. That agreement is a protocol: TCP/IP. Agreeing to use that protocol is like molecules agreeing to use gravity or the periodic table. Everything everyone does while operating or using the Internet is gravy atop TCP/IP. The Web is also NEA. So is email. Those are held together by simple protocols too.

Third is that the sure sign of a good idea is that it’s easy to do bad things with it. Look at email, which is 99.x% spam. Yet I’m writing one here and you’re reading it. NFT’s are kind of like QR codes in the early days after the patent’s release to the word by Denso Wave early in this millennium. I remember some really smart people calling QR codes “robot barf.” Still, good things happened.

So, if bad things are being done with NFTs, that might be a good sign.

The image above is of a window into the barn that for several decades served the Crissman family in Graham, North Carolina. It was toward the back of their 17 acres of beautiful land there. I have many perfect memories of time spent on that land with my aunt, uncle, five cousins and countless visitors. The property is an apartment complex now, I’m told.

February 18, 2022

Clearing things up

Back in 2009 I shot the picture above from a plane flight on approach to SFO. On Flickr (at that link) the photo has had 16,524 views and has been faved 420 times as of now. Here’s the caption:

These are salt evaporation ponds on the shores of San Francisco Bay, filled with slowly evaporating salt water impounded within levees in former tidelands. There are many of these ponds surrounding the South Bay.

A series microscopic life forms of different kinds and colors predominate to in series as the water evaporates. First comes green algae. Next brine shrimp predominate, turning the pond orange. Next, dunaliella salina, a micro-algae containing high amounts of beta-carotene (itself with high commercial value), predominates, turning the water red. Other organisms can also change the hue of each pond. The full range of colors include red, green, orange and yellow, brown and blue. Finally, when the water is evaporated, the white of salt alone remains. This is harvested with machines, and the process repeats.

Given the popularity of that photo, I’ve decided to make a large print of it to mount and hang somewhere. But there’s a problem: this photo was shot with a 2005-vintage Canon 30D, an 8.2 megapixel SLR with an APS-C )(less than full frame) sensor, and an aftermarket zoom lens. It’s also a JPEG shot, meaning compressed, which means it shows artifacts when you look closely or enlarge a lot. To illustrate the problem, here’s a close-up of one section of the photo:

See how grainy and full of artifacts that is? Also not especially sharp.

So that was an enlargement deal breaker. Until today, that is, when my friend Marian Crostic, a fine art photographer who often prints large, told me about Topaz Labs‘ Gigapixel AI. I’ve tried image enhancing software before with mixed results, but on Marian’s word and an $80 price, I decided to give this one a whack. Here’s the result:

Color me impressed enough to think it’s worth sharing.

February 11, 2022

Building a Relationship Economy

In faith that nothing lasts forever, and that an institution that’s been around since 1636 is more likely to keep something published online for longer than one that was born in 1994 and isn’t quite dead yet (and with full appreciation to the latter for its continued existence), I’ve decided to re-publish some of my Linux Journal columns that I hope have persistent relevance. This one is from the February 2007 issue of the magazine.

Building a Relationship Economy

Is there something new that open source development methods and values can bring to the economy? How about something old?

I think the answer may come from the developing world, where pre-industrial methods and values persist and offer some helpful models and lessons for a networked world that’s less post-industrial than industrial in a new and less impersonal way.

This began to become apparent to me a few years ago I had a Socratic exchange with a Nigerian pastor named Sayo, whom I was lucky to find sitting next to me on a long airplane trip.

We were both on speaking junkets. He was coming from an event related to his latest work: translating the Bible to Yoruba, one of the eight languages he spoke. I was on my way to give a talk about The Cluetrain Manifesto, a book I co-authored.

My main contribution to Cluetrain was a chapter called “Markets are conversations”. Sayo asked me what we meant by that. After hearing my answer, he acknowledged that our observations were astute, but also incomplete. Something more was going on in markets than just transactions and conversations, he said. What was it?

I said I didn’t know. Here is the dialogue that followed, as close to verbatim as I can recall it…

“Pretend this is a garment”, Sayo said, picking up one of those blue airplane pillows. “Let’s say you see it for sale in a public market in my country, and you are interested in buying it. What is your first question to the seller?”

“What does it cost?” I said.

“Yes”, he answered. “You would ask that. Let’s say he says, ‘Fifty dollars’. What happens next?”

“If I want the garment, I bargain with him until we reach an agreeable price.”

“Good. Now let’s say you know something about textiles. And the two of you get into a long conversation where both of you learn much from each other. You learn about the origin of the garment, the yarn used, the dyes, the name of the artist, and so on. He learns about how fabric is made in your country, how distribution works, and so on. In the course of this you get to know each other. What happens to the price?”

“Maybe I want to pay him more and he wants to charge me less”.

“Yes. And why is that?”

“I’m not sure.”

“You now have a relationship”.

He went on to point out that, in his country, and in much of what we call the developing world, relationship is of paramount importance in public markets. Transaction still matters, of course. So does conversation. But the biggest wedge in the social pie of the public marketplace is relationship. Prices less set than found, and the context for finding prices is both conversation and relationship. In many cases, relationship is the primary concern, not price. The bottom line is not everything.

Transaction rules the Industrialized world. Here prices are set by those who control the manufacturing, distribution and retail systems. Customers do have an influence on prices, but only in the form of aggregate demand. The rates at which they buy or don’t buy something determines what price the “market” will bear in a system where “market” means aggregated demand, manifested in prices paid and quantities sold. Here the whole economic system is viewed mostly through the prism of price, which is seen as the outcome of tug between supply and demand.

Price still matters in the developing world, Sayo said, but relationship matters more. It’s a higher context with a higher set of values, many of which are trivialized or made invisible when viewed through the prism of price. Relationship is not reducible to price, even though it may influence price. Families and friends don’t put prices on their relationships. (At least not consciously, and only at the risk of cheapening or losing a relationship.) Love, the most giving force in any relationship, is not about exchanging. It is not fungible. You don’t expect a payback or a rate of return on the love you give your child, your wife or husband, your friends.

Even in the industrialized world, relationship has an enormous bearing on the way markets work, Sayo said. But it is poorly understood in the developed world, where so much “comes down to the bottom line”.

I shared this conversation a few weeks later with Eric S. Raymond, who put the matter even more simply. “All markets work at three levels”, he said. “Transactions, conversations and relationships”. Eric is an atheist. Sayo is a Christian. With those two triangulating so similarly on the same subject, I began to figure there was something more to this relationship business.

I began to ask questions. For example, What happens when you view markets through the prism of relationship? Why do we write free or open source code?

Linus says (in the title of his only book) he does it “Just for Fun”. Yes, there are practical purposes there have to be. Scratching itches, for example. Development communities are notoriously long on conversation (check out the LKML for starters), and on relationship as well. Not a whole lot of transaction there, either, since the code is free. Next question: Are there economies involved?

I think the answer is yes, and they are concentrated on the manufacturing end. We make useful code for its “because effects”. Thanks to Linux, much money will be made; but because of it, far more than with it. Just look at Google and Amazon as two obvious examples. Perhaps a billion of the world’s Websites are Apache on Linux.

Relationship is involved here, too. Writing code that serves as abundant and free building material is an act of generosity. Dare we say we do it for love? Certainly a lot of us love doing it.

Likewise with performing artists. Musicians don’t take up an instrument and develop their skills just to make money at it. They do it for love of the experience, of playing together with other musicians, of giving something to an audience, and to the world.

Of course, professionals like to get paid for their work too. That’s what makes them professionals.

What if the goods are essentially free (as in beer, air or love)? That’s the case with code, music, art, and anything else that can be digitized and copied. Many artists want or need to be paid for what they do. The question is how we get our love to fund theirs — how we can relate in ways that work financially for both the supply and the demand of essentially free stuff.

The entertainment industry has had an answer ever since the Net showed up. Hollywood wasn’t blind to the Net. Quite the opposite. They correctly saw the Net as a way for every device to be zero distance from every other device — and to pass identical copies of anything between anybody a cost that rounded to zero. They saw this a threat to their incumbent business model. So they came up with a way to deal with that threat: DRM, or Digital Rights Management. DRM worked by crippling recorded goods so it can’t easily be copied except by those whose rights were managed by suppliers.

It hasn’t worked. A few days ago Steve Jobs said so himself, in a landmark essay titled Thoughs on Music, published on February 6. It not only notes the failure of DRM, but subtly recruits customers and fellow technologists to help Apple convince the record industry that it’s best to sell music that isn’t DRM’d. He concludes, “Convincing them to license their music to Apple and others DRM-free will create a truly interoperable music marketplace. Apple will embrace this wholeheartedly”.

The operative verb here is “license”.

Let’s ignore the record companies for a minute. Instead, lets look behind them, back up the supply chain, to the first sources of music: the artists. Part of the system we need is already built for these sources, through Creative Commons. By this system, creative sources can choose licenses that specify the freedoms carried by their work, and also specify what can and cannot be done with that work. These licenses are readable by machines as well as by lawyers. That’s a great start on the supply side.

Now let’s look at the same work from the demand side. What can we do — as music lovers, or as customers — to find, use, and even pay for, licensed work? Some mechanisms are there, but nothing yet that is entirely in our control — that reciprocates and engages on the demand side what Creative Commons provides on the supply side.

Yes, we can go to websites, subscribe to music services, use iTunes or other supply-controlled intermediating systems and deal with artists inside those systems. But there still isn’t anything that allows us to deal directly, on our own terms, with artists and their intermediaries. Put another way, we don’t yet have the personal means for establishing relationships with artists.

For example, I relate in some ways to Stewart Copeland, though he doesn’t know it. Stewart is best known as the drummer in The Police, even though the band hasn’t recorded an album since 1983 and Stewart has since then established himself as a first-rank composer of soundtracks, including “Rumble Fish”, “Talk Radio” and “Wall Street”. IMDb lists him as a composer of scores for sixty-nine movies and TV productions. You have to hit “page down” six times or more to get to the bottom of the listings. Still, much as I appreciate Stewart’s compositions, I’ve always loved his drumming. I’m not a drummer, but I’m a serviceable percussionist. (When I pick up bongos, congas, a rub-board or a tambourine, I get approving nods from the real musicians I jam with — as rarely as the occasion arises.) When the Police ceased touring and producing albums, I missed Stewart’s drumming most of all.

Last year I got a big charge out of hearing an IT Conversations podcast interview with Stewart, though I was disappointed to hear he doesn’t drum much anymore.

Then I heard last week on the radio that the Police may be getting back together and touring again. I can relate to that. But how? Stewart’s website is one of those over-produced flash-filled things that recording an performing artists seem to think they need in order to “deliver an experience” or whatever. Nearly every internal link leads to a link-proof something-or-other in the same window, among other annoyances. To call it relationship-proof would be an inderstatement.

So instead let’s look at relating through the IT Conversations podcast. I say that because yesterday Phil Windley, who runs IT Conversations, posted Funding Public Radio (and ITC) with VRM on his blog, and listed some of the things he might be looking for from VRM or Vendor Relationship Management. That is, from something that lives on the demand side, but can relate on mutually useful terms with the sjupply side which in his case is IT Conversations.

Here’s the first answer: It can’t be limited to a browser. I want a button, or a something, on my MP3 player that allows me to relate not only to IT Conversations as an intermediary, but to the artist as well — if the artist is interested. They may not be. But I want that function supported. What we need on the user’s side is a tool, or a set of tools, that support both independence and engagement.

If what we’re looking for doesn’t exist, how hard will it be to build? I’m sure it won’t be easy, but it will be less hard than it was before the roster of open source tools and applications grew to six figures, which is where it stands now. And that’s not counting all the useful standards that are laying around too.

What do we need?

First, I think we need protocols. These should be modeled on the social ones we find in free and open marketplaces. They should work like the ones Sayo talked about in his Socratic dialogue with me on the airplane. They should be simple, useful and secure.

Second, we need ways of supporting transactions. This is a tough one, because to work they need to be low-friction. I should be able to pay IT Conversations (or any public radio station, or any podcaster) as easily as I pay for a coffee. Or better yet, as easily as I tip a barista. So PayPal won’t cut it. (Not the way I’ve experienced PayPal, anyway.)

Third, we need ways of selectively and securely asserting our identities, including our choice to remain anonymous. This means getting past sign-on hurdles on the Web, and past membership silos out in the physical world (such as the ones that require a special card, or whatever). Again, the friction should be as low as possible.

Fourth, we need ways of expressing demand that will bring supply to us. Let’s say I want to hear other interviews with Stewart Copeland. I don’t want to go through the standard Google/Yahoo text search. I want to tell the marketplace (in some cases without revealing yet exactly who I am) that I’m looking for these interviews, and then have them find me. Then I want an easy way to pay for them if I feel like it. As Sayo suggests, I might be more willing to pay something if I can relate to the source, and not just invisibly use goods produced by that source.

In Putting the Wholes Together, which I posted recently at Linux Journal, I said public broadcasting would be a good place to start — not just because public broadcasting needs to find ways to make more money from more listeners and viewers, but because payment is voluntary. Seems to me that when payment is voluntary, relationship will drive up the percentage of those who pay. It’s just a theory, but one that should be fun to test.

Soon as I get the time to put it together, I’ll put out a challenge for developers (that’s you, if you write code) to help out on this. Some developers are already collected at ProjectVRM, which is where we’re organizing the effort.

I’m meeting with NPR in Washington, D.C. in a couple hours, and again tomorrow. I’ll bring up the possibility of help from you guys when I talk to them. And I’ll be in many meetings and talks next week at the IMA Convention in Boston and Beyond Broadcast in Cambridge. Help is welcome.

Let’s show these folks how much more they can do because they relate. Let’s obsolete those annoying fund-raising marathons when they shut off programming, plead poverty and give you some schwag if you send money. There has to be a better way. Let’s build it.

January 15, 2022

TheirCharts

If you’re getting health care in the U.S., chances are your providers are now trying to give you a better patient experience through a website called MyChart.

This is supposed to be yours, as the first person singular pronoun My implies. Problem is, it’s TheirChart. And there are a lot of them. I have four MyChart accounts with four health care providers, so far: one in New York, two in Santa Barbara, and one in Los Angeles. I may soon have another in Bloomington, Indiana. None are mine. All are theirs, and they mostly don’t get along. Especially with me.

Not surprisingly, all of them come from a single source: Epic Systems, the primary provider of back-end information tech to the country’s health care providers, including most of the big ones: the Harvard, Yale, Mayo, UCLA, UChicago, Duke, Johns Hopkins, Mount Sinai, and others like them. But, even though all these MyChart portals are provided by one company, and (I suppose) live in one cloud, there appears to be no way for you, the patient, to make those things work together, or for you to provide them with data you already have from other sources. Which you could presumably do if My meant what it says.

The way they work is also often perverse. For example, a couple days ago, one of my doctors’ offices called to tell me we would need to have a remote consult before she changed one of my prescriptions. This, I was told, could not be done over the phone. It would need to be done over video inside MyChart. So now we have an appointment for that meeting on Monday afternoon, using MyChart.

I decided to get ahead of that by finding my way into the right MyChart and leaving a session open in a browser tab. Then I made the mistake of starting to type “MyChart” into my browser’s location bar, and then not noticing that my browser auto-completed the URL to one of the countless other MyCharts maintained by countless other health care providers. Then I wasted an hour or more, failing to log in and then failing to recover my login credentials. It wasn’t until I called the customer service number on the website that I found I was trying to get into a MyChart that looked like mine but was for some provider I’d never heard of. And which had never heard of me.

Now I’m in looking at one of my two MyCharts for Santa Barbara, where it shows no upcoming visits. I can’t log into the other one to see if the Monday appointment is noted there, because that MyChart doesn’t know who I am. So I’m hoping to unfuck that one on Monday before the call on whichever MyChart I’ll need to use. Worst case, I’ll just tell the doctor’s office that we’ll have to make do with a phone call. If they answer the phone, that is.

Just one story among millions.

The problem is, we have hundreds or thousands of isolated health care providers here, all using one company’s back end to provide personal health care information to millions of patients through hundreds or thousands of different portals, all called the same thing (or something close), while providing no way for patients to gather their own data from multiple sources and look at it or use it in sensible ways in that system. Or any system.

To call this fubar understates the problem.

Here’s what matters: Epic can’t solve this. Nor can any or all of these separate health care systems. Because none of them are you.

And you’re where the solution needs to happen. You need a simple-and standardized way to collect and manage your own health-related information and engagements with multiple health care providers.

This doesn’t mean you need to be out there your own. You need expert help. In the old days, you used to get that through your primary care physician. But large health care operations have been hoovering up private practices for years, and one of the big reasons for that has been to make the data management side of medicine easier for physicians and their many associated providers.

In the midst of this there presists a market hole where your representation in the health care marketplace needs to sit. I know of one example of how that might work: the HIE of One. (HIE is Health Information Exchange.) For all our sakes, somebody please fund that work.

Far too much time, sweat, money, and blood is being spilled trying to solve this problem from the center outward. (For a few details on how awful that is, start reading here.)

While we’re probably never going to make health care in the U.S. something other than the B2B insurance business it has become. But we can at least start working on a Me2B solution in the place it most needs to work: with patients. Because we’re the ones who need to be in full command of our relationships with our providers as well as with our selves.

Health care, by the way, is just one category that cries out for solutions that can only come from the customers’ side. Customer Commons has a list of fourteen, including this one.

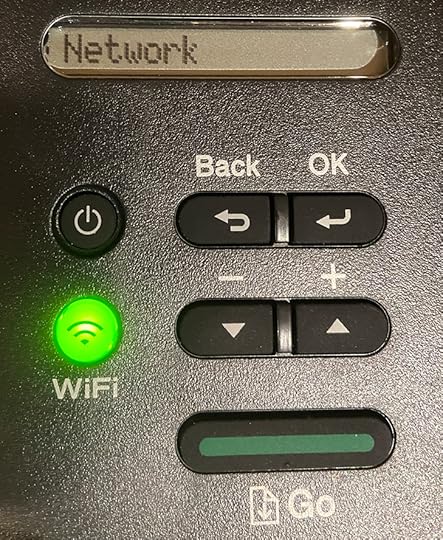

Bothering with Brother

That’s the UI for the Brother HL-L2305w laser printer, which you can get for $140 right now at OfficeMax (or Office Depot, same thing). It’s a good deal. It also took me a whole day to set up.

See, it comes with instructions that say to use the UI above to make CONNECTING WLAN happen. It doesn’t. Instead it sits for awhile, says TIMED OUT, and then prints out a page that says “The WLAN access point/router cannot be detected,” and gives instructions to locate the printer as close as possible to your wi-fi (that’s the WLAN) access point, to make sure you’re not using MAC address filtering or other secure things that might prevent connection.

After parking an access point (we have four in our house, all connected by Ethernet through a switch to the cable modem) right on top of the printer, I gave up, assumed it was bad, took it back and swapped it for another that had the same problem, meaning I was dealing with a feature.

Then, after failing to find help in the Brother Product Support Center, I registered the printer and logged in as a now-known customer. In that state I was able to chat with an entity (human, it seemed, but ya never know) who pointed me to a page with useful instructions, plus a video that’s also on YouTube, where I should have looked in the first place. Lesson re-learned.

So, if you get one, go straight to that YouTube link and save a lot of trouble/

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers