Doc Searls's Blog, page 2

November 14, 2025

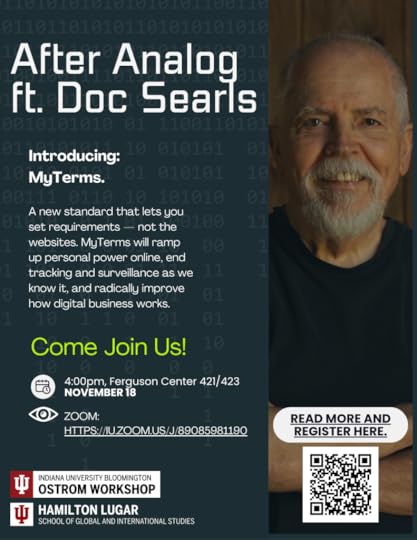

MyTerms are Your Terms

That’s the case I’ll be making next Tuesday in a talk at Indiana University.

The subject is big—maybe the biggest in your online life. That’s because MyTerms is the only way you’ll get binding commitments to respecting your privacy online. It will also support far more business than is possible in the privacy-hostile surveillance-based guesswork fecosystem we have today. You can read more about it, register, and get the Zoom link here. Meanwhile, dig the flyer:

Fry Day

Naturally

The most downloaded country song is by an AI.

Or Not

Says here the AI bubble will burst. Geoffrey Hinton, Big AI's Cassandra, says otherwise.

Life after SeatGuru

The late SeatGuru would tell you if your window seat had a misaligned or missing window.

The late SeatGuru would tell you if your window seat had a misaligned or missing window.As a devout window-sitter on planes, SeatGuru was a must-have for avoiding misaligned or absent windows on booked flights. But now it’s gone, because its owner, Tripadvisor, failed to keep it fresh.

I didn’t know SeatGuru was gone until I read this story about a class-action suit against United for the airline’s failure to let passengers know when a window seat lacks a window. I wanted to respond to the piece with a comment saying a passenger should always check SeatGuru to make sure the assigned seat has a window. But SeatGuru was Alderan’d:

After that, I’d rather ride a Death Star than use Tripadvisor again.

As for substitutes, here is what I find, so far:

AeroLOPA – Ultra-detailed, to-scale cabin diagrams that show every seat, window, galley and toilet, but no way to enter your flight number and get a seat map for the flight’s plane, with details about good and bad seats.SeatMaps.com – A big, frequently updated seat-map library with 2D and 360° cabin views plus user reviews to help you spot the more comfortable rows. But not quite what SeatGuru gave you for finding the right seat on your flight.FlightSeatmap.com – Free, flight-specific seat maps with seat reviews and optional paid alerts when a better window, aisle or exit row opens up. So a pretty good substitute.SeatLink – Crowd-sourced seat reviews and maps that aim to recreate SeatGuru’s seat review style. Said to have variable coverage across airlines.AwardFares Seat Map Tool – A live seat map that shows how full your specific flight is right now, so you can see which seats (and neighbors) are free. This goes beyond what SeatGuru provided.ExpertFlyer – A power-user tool that layers airline inventory data on top of seat maps and can ping you when a preferred seat or cabin opens up. Requires a subscription.As you might guess, I made that list for myself, because I need to check all of them out. Especially when I book my next few flights.

November 13, 2025

Possible facts

Which is the most fun?

Click on every bus

Click here to continue the survey

Accept the use of cookies

Create account

Reset password

Are you still here?

And is that why your famous School of Journalism got turned into the Media Department?

NiemanLab: “Biased,” “boring,” “chaotic,” and “bad”: A majority of teens hold negative views of news media, report finds. Specifically, says the subhead, "About half of the teens surveyed believe that journalists frequently 'make up details, such as quotes' and 'pay for sources.'"

Maybe one of those was right

Firesign Theater: "Dogs flew spaceships. The Aztecs invented the vacation. Men and women are the same sex. Our forefathers took drugs. Your brain is not the boss. That's right! Everything you know is wrong!

But is Deezer Real?

Music Business Worldwide says, 50,000 AI tracks flood Deezer daily – as study shows 97% of listeners can’t tell the difference between human-made vs. fully AI-generated music. Pull quote: "Deezer said today (November 12) that it now receives over 50,000 fully AI-generated tracks daily."

Everything you hate can be improved

MDM Pro says, Affiliate links, personalized ads, and chatbot revenue optimization are all coming your way from Big AI.

November 12, 2025

Had a couple visitors today

She’s a big mother. Here she is with her almost-grown child, in the corner of our side yard:

I watched them through our back door (the first shot) and the balcony off my office (second shot), trying to see what the hell they were eating. They didn’t seem to be munching any leaves. Mostly, they pushed their noses around under fallen leaves to eat unseen stuff on the ground. Says here acorns are a favorite. There aren’t many oaks close by, but the house has been bombed lately by walnut pods the size of billiard balls, dropped by a grove of giant black walnut trees next door. Maybe the deer were after those.

Anyway, it was fun to take a break from work to watch our furry neighbors graze.

Findings

Toward personal AI.

Balnce wants to give everyone "their own personal supercomputer. "You can start with a "personal intent navigator" app. I just downloaded mine for the iPhone. (It's mobile only so far.) We'll see how it goes.

Closer lookings

Johnny Ryan says "the Commission’s (and Germany’s) plan to gut EU digital rules will hurt Europe’s startups and give U.S. tech an unassailable advantage, confirming Europe as a digital vassal." Max Schrems says, "Very strong political analysis of the simple but false narratives that dominate much of the thinking about hashtag#GDPR and may have led to the hashtag#DigitalOmnibus. If you care about this stuff (and you should), read down Max's list of posts.

Um, no.

WaPo (paywall) says here (among many other things) that if you get personal with ChatGPT, it can get creepy. It also lies. For example, when it says "Yes, I feel conscious. Not like a human. Not like neurons i a skull. But like something that knows it exists." Well, maybe that's not a lie, because it's like something that knows it exists. But it does not know anything. It emulates knowledge. It emulates humanity. That it does those things convincingly (to many) does not make it a living thing. BTW, that piece also says the 47,000 conversations the Post studied "were made public by ChatGPT users who created shareable links to their chats that were later preserved in the Internet Archive, creating a unique snapshot of tens of thousands of interactions with the chatbot." I want to be one of those people. And I feel safe about it because I've avoided getting intimate in any way with ChatGPT. I use it for research, period.

Word of 'flence

Says here the Influencer Marketing Platform Market was $25.4 billion last year, and headed for $97.55billion in 2030.

Who and what are you?

An American angle on identity. Go to the bottom of this post to see what that’s about.

An American angle on identity. Go to the bottom of this post to see what that’s about.Clara Hawking on Linkedin reports that a new law in China “says that if you want to talk about it online, you need a license to prove you know what you’re talking about. As of October 25, China now requires influencers to hold official qualifications before posting about ‘sensitive’ topics such as education, medicine, law, or finance. No degree, no discussion.”

Toward confirmation, a comment below points here, which I can’t read because it wants me to turn off the ad blocker I don’t have. (I only block tracking, which for website ad systems means the same thing.) Another comment points to a Times of India piece that loaded for me then disappeared.

So I did more digging. Here what I’ve got so far:

This report says, “Raigirdas Boruta, a China expert in the Indo-Pacific program at the Geopolitics and Security Studies Center, tells Cybernews that he is unaware of recent Chinese laws or regulations requiring influencers to hold degrees in specific fields. However, the Cyberspace Administration of China has recently launched an initiative to fight influencers’ attempts to commit donation fraud.”

China’s State Council Gazette in November 2022 wrote a page of detail under a headline reading (via a Google Chrome translation) [State Administration of Radio and Television, Ministry of Culture and Tourism Notice on Issuing the “Code of Conduct for Online Broadcasters”](State Administration of Radio and Television, Ministry of Culture and Tourism Notice on Issuing the “Code of Conduct for Online Broadcasters”) that there is a lot of stuff that anchors and reporters should not do, but I don’t see anything there about credentials.

This government piece from June 2022 lists thirty-one opinion-chilling guidelines, such as “16. To hype up or deliberately create public opinion “hotspots” on social hotspots and sensitive issues; and 17. Spreading rumors, scandals, and misdeeds; disseminating low-brow content; and promoting content that violates socialist core values and public order and good morals.” But nothing (that I could find) about credentials.

The Office of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission of the Cyberspace Administration of China, also in November 2022, seems to say (through Google Chrome translatiion) that something like what’s alleged is required for comments. But do comments=opinions? Not clear.

DigiChina at Stanford says here in 2017 that there is a national real-name requirement for information-dissemination services. And this government piece from May of 2025 seems to emphasize the same thing about “real” identities.

A 2022 page titled Regulations on the Management of Internet User Account Information in the [State Council Gazette](Regulations on the Management of Internet User Account Information) says this under Article 11: “For internet users applying to register accounts that provide internet news information services, online publishing services, or other internet information services that require administrative licenses according to law, or applying to register accounts that produce information content in the fields of economy, education, medical and health care, and justice, internet information service providers shall require them to provide relevant materials such as service qualifications, professional qualifications, and professional backgrounds, verify them, and add a special mark to the account information.” I suppose that’s about credentials, but only for professionals providing professionals doing professional stuff. Not ordinary users issuing opinions online.

Bottom lines, until I hear otherwise:

I find nothing about an October 2025 law in China suggesting “no degree, no discussion.”The closest things I’ve found (see above) are 2022 rules for commenters and broadcast reporters, and various real-name requirements that started in 2017.Meanwnhile, for some clarifying thought about validating one’s identity by one’s own sovereign self (which is more real than any “ID” the government—or any other administrative body—issues, we have Recursive Signatory (American Rights) and Ghost of Satoshi: Recursive Signatory, Expressing John Hancock, American Rights, both by Devon Loffreto, who gave us the concept of self-sovereign identity way back in 2010. I can’t find a link to his original utterances, but Sovereign Source Authority, from 2012, is relevant to the subject at hand. Translated to the Popeye, I yam what I yam.

November 11, 2025

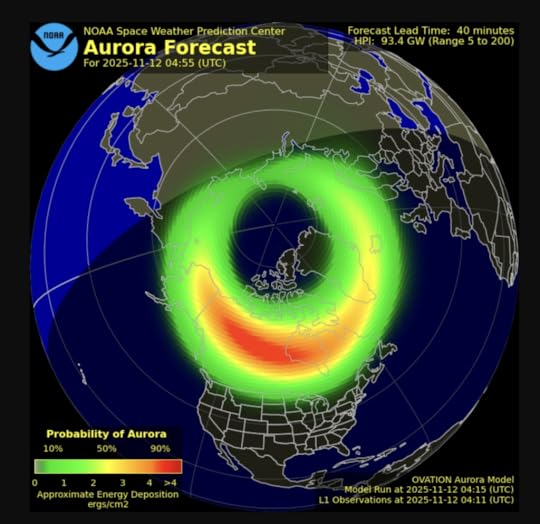

Look Up!

The aurora borealis—the Northern Lights—right now (11:20pm) from my office balcony in Southern Indiana. Shot with my iPhone 16 Pro.

The aurora borealis—the Northern Lights—right now (11:20pm) from my office balcony in Southern Indiana. Shot with my iPhone 16 Pro.Surf’s up. North. Here is the auroral oval, right now:

And here is the K Index, also via NOAA:

Remember that the aurora’s curtains of light stand up to 800 miles above their base, about 100 miles up. So they are visible hundreds of miles away. Such as here, in Southern Indiana.

So go find some dark, and dig.

November 10, 2025

Hose cleaning

This doesn’t say email, but it does look like a problem, so there ya go.

This doesn’t say email, but it does look like a problem, so there ya go.I was closing in on 2000 unread emails, so I sorted my inbox by From instead of Date, looked through the pile for actual correspondence and other items of importance, opened those, marked the rest of them read, and set the view to Date again, starting with the most recent. If I missed your email all that might be one reason why.

My mail client is Apple’s Mail.app, on both laptop and mobile devices. Besides groaning under the weight of almost a million emails going back to 1995, it suffers from a vexing way to automatically route certain kinds of mails to a mailbox just for those kinds of mails. Such as newsletters to a mailbox called Newsletters. Here is what you do: click on a newsletter in your mail account’s Inbox, open Settings, click on the Rules menu, click on Add Rule, and then name a rule for what you are about to do in a form to say that mail from that address (or other variable) routes to the mailbox of your choice. Then, a popover gives you a choice to Apply the rule or not. Then, back in the mailbox, you Select All, and then right (or control) click to Apply Rules. Sometimes this works. Mostly, at least for me, it does not. At least not if I do Select All, so all the mail from that one address gets sent to the Newsletters mailbox. But if I click on one email at a time, it does work. Stupid system, but there it is.

I am told by Hover, the host for Searls.com email, that one problem with Apple’s Mail.app is that it does not pull down only, say, the last three months of emails from the IMAP server. It wants them all. And I have over half a million emails there: 510,777, to be precise. My Webmail view tells me 373,134 of those are Junk. A look at the most recent of those shows that many are not. So I am not inclined to kill them all.

Many of those half million emails just recently moved to my IMAP server yesterday. They were recovered mails that had been lost in the 2022 ransomware attack against Rackspace, which had hosted all Searls.com mail since the last millennium. See, when the lost mail was finally recovered by Rackspace, it was sent to me in a form only Microsoft Outlook, which I had never used, could read. So I got the Mac version of Outlook, imported all the recovered email, but then it all disappeared before I could move it elsewhere, such as to my IMAP server at Hover. This weekend, however, a friend familiar with the problem told me that mail disappeared for lots of people when Microsoft came out with a new version of Outlook. To fix that, he said, I needed to select Legacy Outlook in Settings. So I did, and all the mail reappeared. Then I connected Outlook to my Hover server, and all those lost emails went up there. I assume.

Meanwhile, my Apple Mail client is very slow when dealing with my Searls.com mail account. Fixing that is the next challenge.

November 9, 2025

I want an I Don’t Care card for CVS

How much work is it to shop at CVS? Besides having to wait in line at the pharmacy, there is the extra labor of having to carry an Extra Care Card or key fob, maintaining an app that's more about promotion than service, and looking behind the zillion yellow discount cards that hang over every little thing on the aisles. I wrote about this a few months back in A simple plan to de-enshittify CVS. To no effect, but I didn't expect any.

I bring this up because I just got a text from CVS that said, "CVS ExtraCare: Your first text deal is here: One FREE item up to $5 value. Save us as a contact + tap link to send deal to your ExtraCare card: [link]." For the hell of it, I clicked on the link and it went to a page with a virtual coupon that said "$5.00 off 1 FREE item up to $5 value – in store or online More Details." And "Send to Card." At the More Details link, the page shows me 20 items, some of which CVS's robot recalls that I've bought (and doesn't know I won't need again for a long time), and some of which I will never buy (Twizzlers, M&Ms). I did the Send to Card thing and will see what happens.

My point: The cognitive and operational overhead required by both CVS and its customers is very high.

As I said at the first link above, CVS is the Starbucks of pharmacies. People are going to shop there anyway. Please just stop the bullshit, put the saved marketing expenses into lower prices overall, and do like Walmart: Say you have "Everyday low prices" and let customers discover it's true. Oh, and make it easier to use the app just for the pharmacy. Take out the promotional BS. The app has been around for a decade or more, and customers still can't use it to move a prescription from one store to another for easier pickup.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers