Doc Searls's Blog, page 4

September 11, 2025

Privacy is a Contract

SD-BASE is a contract you might proffer that means service delivery only. It makes explicit the tacit understanding we have when we go into a store for the first time: that the store’s service is what you came for, and nothing more. Other terms from a roster of MyTerms choices might allow, for example, anonymous use of personal data for AI training. Or for intentcast signaling*.

SD-BASE is a contract you might proffer that means service delivery only. It makes explicit the tacit understanding we have when we go into a store for the first time: that the store’s service is what you came for, and nothing more. Other terms from a roster of MyTerms choices might allow, for example, anonymous use of personal data for AI training. Or for intentcast signaling*.In the natural world, privacy is a social contract: a tacit agreement that we respect others’ private spaces. We guard those spaces with the privacy tech we call clothing and shelter. We also signal what’s okay and what’s not using language and gestures. “Manners” are as formal as the social contract for privacy gets, but those manners are a stratum in the bedrock on which we have built civilization for thousands of years.

We don’t have it online. The owner of a store who would never think of planting tracking beacons inside the clothes of visiting customers does exactly that on the company website. Tracking people is business-as-usual online.

The reason we can’t have the same social contract for privacy in the online world as we do in the offline one is that the online world isn’t tacit. It can’t be. Everything here is digital: ones, zeroes, bits, bytes, and program logic. If we want privacy in the online world, we need to make it an explicit requirement.

Policy won’t do it. The GDPR, CCPA, DMA, the ePrivacy Directive, and other regulations are all inconveniences for the $trillion-plus adtech (tracking-based advertising) fecosystem.

“Consent” through cookie notices doesn’t work, because you have no way of knowing if “your choices”are followed. Neither does the website, which has jobbed that work out to OneTrust, Admiral, or some other CMP (consent management platform), which we presume also doesn’t know or much care. Nearly all of those “choices” are also biased toward getting your okay to being tracked.

Polite requests also don’t work. We tried that with Do Not Track, and by the time it finished failing, the adtech lobby had turned it into Tracking Preference Expression. Like we wanted to be tracked after all.

What we need are contracts—ones you proffer and sites and services agree to. Contracts are explicit, which is what we need to make privacy work in the online world. Again, there is no tacit here, beyond the adtech fecosystem’s understanding that every person on the Web is naked, and perfect for exploitation.

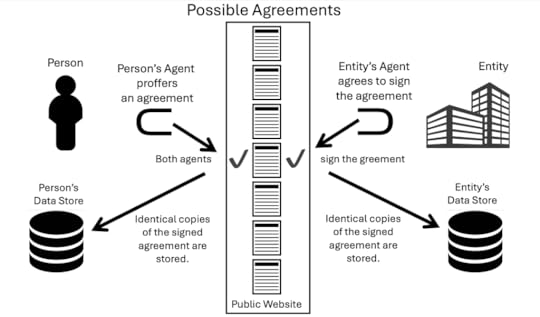

This is why we’ve been working for eight years on IEEE P7012 Draft Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, aka MyTerms. With MyTerms, you are the first party, and the site or service is the second party. You present an agreement chosen from a limited roster posted on the public website of a disinterested nonprofit, such as Customer Commons, which was built foro exactly this purpose. When the other side agrees, you both keep an identical record. (The idea is for Customer Commons to be for privacy contracts what Creative Commons is for copyright licenses.)

MyTerms might look scary to business-as-usual. But so did the PC, the Internet, and the smartphone. All did far more for business than the incumbent systems they obsolesced. When customers and companies start relating as partners who fully respect each other, the range of what’s possible in business widens much farther than what the old tracking-based fecosystem will allow.

We can explore those frontiers in other posts. Right now, I just want to make clear that contract is the only way to personal privacy online. And MyTerms will get us started.

*Intentasting is where you let a market of qualified sellers know what you’re looking for, in ways that preserve your privacy.

September 9, 2025

Remembering R.C. Ward

The first thing R.C. Ward taught in our biology class at Guilford College was his eponymous Law:

“If it works, it’s good.”

He frequently mentioned Ward’s Law by name and required it as an answer to nearly every test. As Richard Nilson explains here, Professor Ward was not a normal dude:

It was 1966 and I was a freshman in college taking an intro to biology class with Richard Carleton Ward, a teacher of peculiar manners and prejudices. I could write a whole chapter on him, the way he spoke out of the side of his mouth in a gravelly grunt, the way he bought conspiracy theories, his suburban house blocked from view in a bourgeois neighborhood by a jungle of bamboo, vines and weeds. He wrote an article for the underground newspaper I was publishing in which he complained ferociously about students’ inability to spell the word, “spaghetti.”

From another Richard Nilson post:

One day, he brought a potted plant to class, and as the bell sounded, he held it up in front of us. “This is the sacred lotus of India,” he said through his teeth. “It sheds water as we are supposed to shed our sins.” He took up a pitcher of water and poured it over the plant, dripping onto the floor, saying to us in biblical voice, “Go forth and sin no more.”

In that same post, Richard reminded me of another Ward’s Law:

His explanation of sex on campus was: “Some do, some don’t.”

He pronounced “some” with a whistled s. That went for every word with an s or a c that sounded like s, such as in the word “pronounced.” All came not just with an ssss sound, but with a  .

.

So let’s call those Ward’s First and Second Laws:

If it work , it’

, it’ good.

good. ome do, and

ome do, and  ome don’t.

ome don’t.There is a lot more about Professor Ward in Green-Wood.com‘s WWII project, featuring biographies of deceased soldiers with surnames running from Pizza to Zeldmann. Scroll way down and you’ll find eight paragraphs above this shot of his grave marker:

Because you probably won’t click on the photo or the link above it, and I want to give the man and his laws full respect, here are those paragraphs:

WARD, RICHARD CARLETON (1916-2005). Sergeant, United States Army. The Ward family members were among the early English settlers in Rhode Island, arriving in the 1670s. John Ward had been an officer in one of Cromwell’s cavalry regiments, arriving in America from Gloucester, England, after the accession of King Charles II. Another ancestor married the son of Benedict Arnold. Burr H. Nicholls and Rhoda Holmes Nicholls, Richard Carleton Ward’s maternal grandparents, were both noted artists. Burr Nicholls was an oil painter and Rhoda Holmes Nicholls was a painter, water colorist, and art editor in the early 1900s.

The 1918 Darien, Connecticut City Directory records the Ward family living on Runkenhage Road in the Tokeneke neighborhood. On March 19, 1927, Richard Ward was listed as sailing from London, England on the SS American Shipper, arriving in New York on March 30, 1927, with his mother Olive Nicholls Ward, age 39, and his sister, Alida Carleton Ward, age 18. Richard, 10 years old, was listed as having been born in Darien, while his mother and sister were listed as born in New York City.

The 1930 federal census lists Richard Ward’s father, Henry Marion Ward, who was 59 and a lawyer at a law office. His mother, Olive, was 42 and an interior decorator. Sister Alida was 15 and Richard was 13. The home they lived in was valued as $60,000. Richard’s grandparents were all born in New York, except for his maternal grandmother, who was born in England. The family also had a female servant living with them, listed as a 46-year-old “Negro” born in North Carolina.

Richard Ward registered in Darien for the draft on October 16, 1940, when he was 24 years old. He listed his date of birth as August 17, 1916, in Darien, and his residence as on Runkenhage Road in Darien. His contact was his mother Olive Nicholls Ward who also lived at that same address. Richard worked at S. W. Hoyt Jr. Co., Inc. on Washington Street in South Norwalk, Connecticut. He was 6′ 4½” tall and weighed 165 pounds, with a light complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. He had a small scar on his left shoulder. He signed his registration card as “R. Carleton Ward.” He enlisted in the United States Army on December 17, 1943, and was discharged on November 5, 1949, according to Department of Veterans Affairs records.

Family trees on the ancestry website indicate that Richard married Antonina Pavlova in Canada in 1949. Per Antonina’s obituary in the Greensboro News & Record, she was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, had been a prisoner of war and, after being liberated by the Allied Forces in Austria, she met United States Army Sergeant Richard Carleton Ward there. The 1950 federal census confirms their marriage, showing Ward’s age as 31 and Antonia’s as 26. Per the 1950 United States census, they were living in New London, Connecticut, along with their newborn daughter, who had been born in Canada in August 1949, but was an American citizen. The additional information for Ward shows that he had been living at Westerly, Rhode Island, the previous year, that he had finished one year of college, and that he had served in World War II, but there was no job listed, although he was not noted as unemployed.

Antonina Ward’s 1954 naturalization record, issued in 1954 in Hartford, Connecticut, shows her residing at Bay Road in Amherst, Massachusetts. In the 1950s, Richard Carleton Ward was a botany instructor at the University of Vermont, holding a Bachelor of Arts degree and appointed in 1954, according to the school’s catalogs for 1954-55 and 1955-56. The 1956 Burlington, Vermont City Directory lists Richard and Antonina as living in Vermont. Ward was active in botanical societies and contributed to collections in many parts of the United States. For example, in 1961, he submitted several samples to the Southern Appalachian Botanical Club. Later, he was a biology professor at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina.

According to Ward’s daughter Tanya, Ward and his wife had three daughters, Tamara Olive Ward, Lalla Ward Reid, and Tanya Ward Feagins. The 1970 North Carolina Divorce Index shows that Ward and his wife were divorced on November 30, 1970, in Guilford, North Carolina. In 1994, Ward was living at 8101 Oak Arbor Road in Greensboro, North Carolina and, in 1995, at 410 Guilford Avenue, Greensboro, North Carolina. Per Social Security records, Ward passed away on December 2, 2005. The Piedmont Bird Club of Greensboro, North Carolina, posted an obituary of Ward in their February-April 2006 newsletter. He was known as Carl and was active in the club for many years. He was an activist and lover of nature.

Ward was interred on October 10, 2007, in the same section as his father. His daughter Tamara’s 2014 obituary in the Greensboro News & Record, states that she was laid to rest in what was termed “the Ward family ancestral burial site.” “Professor Ward Devoted to Preserving the Environment” is carved on his gravestone. Section 77, lot 72.

Some possibly interesting bonus facts:

I started hunting down data on Professor Ward when I wanted to credit the source of Ward’s First Law, which I haven’t forgotten in the sixty years since I learned it. Short on luck in my diggings, I asked ChatGPT for help, and it produced both of the sources I used above.One of those sources, Richard Nilsen, was a year behind me at Guilford, so I am sure that, being a small college (around just 800 students), we at least breathed some of the same air now and then.Richard is a known—and excellent—writer, and much else. It is a treat to have discovered him after all these decades. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we are both from New Jersey. Related fact:::New Jersey, until the last few decades, was bereft of state colleges and universities of any prestige, other than Rutgers. So New Jersey exported more college students to colleges and universities elsewhere than any other US state. In fact, I was accepted at Guilford only because, despite bad grades and SAT scores, I wasn’t from North Carolina and would commit to come on “early decision.”I can’t find one, but I recall seeing blue bumper stickers that said, “DUKE The University of New Jersey at Durham.”My two oldest kids are related to the Ward family. That’s because one of Professor Ward’s children, Tanya, married David Feagins (son of Professor Carroll S. Feagins, who headed the Philosophy Department, where I majored). David’s brother married the sister of my first wife (both kids of Hiram H. Hilty, another faculty member), and their daughter is a first cousin to both of my two kids by that first wife, making Professor Ward their great-uncle by marriage. I think I have that right. I hadn’t thought about that until I read the long biography above.Guilford in those days required that graduating students prove proficiency in a second language. I took no language at Guilford, and my joke about German was that I took two years of it in high school—one of them twice—and gave them back when I was done. So I submitted myself to a test by the German expert at Guilford, Mary Feagins, wife of Carroll Feagins, and future grandma to my kids’ first cousin. Her test required that I read two pages of a German from a textbook out loud, and then translate it. She passed me, saying “I’ve never met anyone who could pronounce a language better while understanding it less.”Guilford has had financial woes in recent years, which is why, five years ago, I made a radically simple recommendation for it. They haven’t followed my advice, but I still stand by it.September 8, 2025

Tis the Seasons

It’s a battle of the holidays at the Sam’s Club here in Bloomington: Christmas on one aisle and Halloween on the next one, back-to-back. Hey! Come in and stock up on stuff that occupies otherwise useful space for 350 partially overlapping non-seasonal days of the year!

At least this stuff (at Sam’s Club in June) tends to get used up, and not stored in your attic:

Unless you’re in Indiana, I suppose. Wondering what percentage of customers store their un-launched fireworks at home, I’ve found nothing about Indiana or the U.S., but I did find Consumer Behaviours and Attitudes to Fireworks in the UK. An excerpt: “Once bought, two-fifths (43%) of people store fireworks in the house, a fifth (20%) in the garage and a sixth (15%) in the shed.” So there ya go.

September 4, 2025

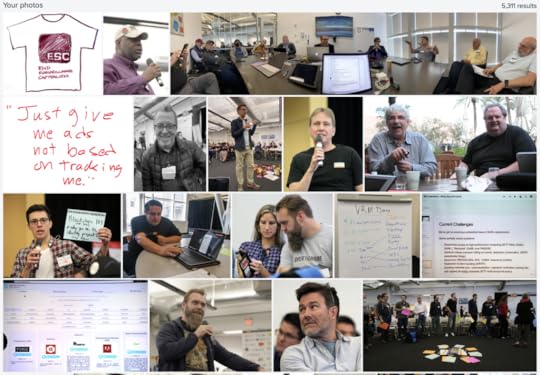

Some Pix and a Few Words About IIW

A top few (said by the site to be the most interesting) of the thousands of IIWs since 2005 that I’ve posted on Flickr.

A top few (said by the site to be the most interesting) of the thousands of IIWs since 2005 that I’ve posted on Flickr.I wrote for Linux Journal from 1996 to 2019, and have been involved with IIW since I helped start it in 2005. So, in an effort to help substantiate a future Wikipedia article on IIW, I wanted a list of all my Linux Journal contributions mentioning “IIW” and/or “Internet Identity Workshop.” (Never mind that my founding role with IIW may disqualify that list from citation. I still wanted it.) So I asked Gemini and ChatGPT separately to provide me with one, and in chronological order. Gemini gave me just three. ChatGPT gave me the whole list, which I already knew by looking through the /linuxjournal/ directory on my hard drive. (I just didn’t want to hand-organize them chronologically.) So, surfacing the effort, here ya go:

Let’s go bust some silosCan we relate?Getting beyond Brad’s ParadoxAn open source approach to fixing public media fundingEOF – Driving Markets from Our Own KernelsWho Controls Your Data?Cluetrain at FifteenThe True Internet of ThingsDealing with Boundary IssuesIdentity: Our Last StandNew Hope for Digital IdentityCookies That Go the Other WayHow Can We Bring FOSS to the Virtual World?FWIW, https://www.linuxjournal.com/search/ at Linux Journal no longer works. Images are also gone from most of the pieces themselves. But it is truly great that Linux Journal is still alive, and the archives are there and link-able. Hats off to Slashdot Media for keeping it up.

For a time in the ’00s, I wrote a newsletter for Linux Journal that isn’t anywhere online. I think I’ll put that up somewhere at searls.com, eventually.

In case you didn’t click on the photo collection above, the link is here.

August 30, 2025

A Small Request to the Goodwill Folks

A Goodwill price sticker before and after I failed to peel and scrape it completely off.

A Goodwill price sticker before and after I failed to peel and scrape it completely off.Please find pricing labels that stick well enough to do their job, and the customer can get off without too much work.

Thanks!

P.S. In an unrelated matter, Grammarly suggested rewriting that second sentence this way:

Please find pricing labels that adhere well enough to perform their intended function, yet can be easily removed by the customer without excessive effort.

Which is better? (Note: I’m posting this thing in a rush between runs to a Costco an hour away from here.)

August 26, 2025

Speaking as a Great Lakes Megacitizen

I’m in the little circle southwest of Indianapolis.

I’m in the little circle southwest of Indianapolis.In Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America, Alec MacGillis notes that the city at the center of a circle containing the largest population within a one-day drive is Dayton, Ohio. You can kinda see that in the map above, which I discovered through Brilliant Maps. They got it from the highly precient Defining US Megaregions, published by the Regional Plan Association in 2009, long before interstate highways across the US became flanked by transport transfer buildings big enough hold five Costcos, and trucks hadn’t yet threatened to outnumber cars on major highways.

When we got a place in Bloomington four years ago, we thought the town was basically isolated. But we quickly found that we were kinda close to a mess of major league cities. Indianapolis was closest, less than an hour up I-69. Lousiville was a bit under two hours away. Cincinnati was about two and a half hours. Columbus was three hours. Chicago was a bit under four hours. Same with St. Louis. Detroit was five hours, and Milwaukee a few minutes more. Cleveland was five and a half. All of these cities were options for a day trip, and we’ve been doing our best to visit them all.

On trips to these cities, we’ve noticed that open country between them is part of what makes them cohere as a region: a feature rather than a bug— especially as the truck traffic between them gets thicker:

Trucks, mostly, passing one of many “cross-dock,” “transload,” “parcel hub,” and “distribution centers” alongside I-70 on the northwest corner of Dayton, Ohio. Shot this when I was driving through earlier this month.

Trucks, mostly, passing one of many “cross-dock,” “transload,” “parcel hub,” and “distribution centers” alongside I-70 on the northwest corner of Dayton, Ohio. Shot this when I was driving through earlier this month.There is something new about all this.

What’s old are Designated Market Areas, or DMAs, also known as TMAs, or Televsion Market Areas:

These are (or were), defined by what collections of TV stations households watched most. My company was once hired by the three major network stations in the Greenville-New Bern-Washington DMA, to help pull viewers in Nash, Wilson, and Wayne Counties away from stations on the same networks in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill market. All stations on both sides had built 2000-foot towers to maximize their signals across their overlapping regions. It was quite the war. (One we lost, but that’s another story.)

By now, TV watching has drifted from “What’s On” to “What’s Where.” And there are a zillion choices of “where”: Everything on YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, on-demand subscription streaming services such as Netflix, HBO, Prime, Disney+, and your nearby cities’ TV stations. Inside that broad and growing mix, TV stations’ slice of the pie is smaller every day.

Regions now are defined more by commercial connections. Across those transport “corridors,” forests and farmlands contextualize the cities with wide rural frames. In McLuhan’s terms, the medium sending the message is the countryside flanking transport corridors between the cities. I suspect this is true of all these megaregions, in different ways. Even the highly urbanized Northeast megaregion has lots of wild and open rural areas to unify the cities between them.

And what organizes the flow of all that commerce? Logistics. Which is digital. And full of AI—for decades.

My thoughts on all this are just starting rather than finishing. I think a good place to do that together is by reading the study that got this started.

August 23, 2025

The Hotel Model of AI

What I like best about Keith Teare‘s latest essay, Who Owns The Front Door to AI? If it isn’t you, its game over, is that it sounds like he’s setting up the case for personal AI.

What I like best about Keith Teare‘s latest essay, Who Owns The Front Door to AI? If it isn’t you, its game over, is that it sounds like he’s setting up the case for personal AI.But he’s not. He’s describing how our AI-assisted lives will get sucked through better interfaces deep into one or more of AI’s giant castles, as “the chat interface replaces the browser as the primary user interface for computing on the web.”

His case is not pretty, but it is clear, thoughtful, knowing, and well-described. He concludes, “Bottom line: Winners will own a trusted front door with standards and auditing and settlements behind it—and help teams actually change how they work and consumers find what they want without dethroning content owners. Everyone else will keep shipping demos into a narrowing feed.”

Note that the winners are giants. You and I? We’re just consumers. Our agency in this system will be no greater than what these giants allow us. Each giant will be (hell, already is) a hotel with a know-it-all concierge who can get us what we want, within the hotel’s confines. But the space is not ours. So, what Cluetrain said in 1999—

—will remain untrue.

—will remain untrue.And the only way our reach will exceed their grasp is with our own personal AI. Simple as that.

August 17, 2025

Happy 79th Anniversary

Eleanor and Allen Searls, at their wedding in Minneapolis on this day in 1946.

Eleanor and Allen Searls, at their wedding in Minneapolis on this day in 1946.Happy for my sister and me, who are both still alive and well. I’m also happy for the thirty-three years Eleanor and Allen made a life and a family together. They were great people, great parents, great teachers, great friends to many, and much more. Both are still missed. Some links:

Their weddingEleanor SearlsAllen SearlsLater… I also did some digging through 2011 correspondence with local realtor Tom Dunn, who said the wedding took place at the late Grace Methodist Church. This Facebook post says the church was at “2125 Thirty Third Avenue North,” but that does not appear to be a valid address. But the photo matches this one in the Hennepin County Library’s digital collection. It’s 2501 NE Taylor Street in Minneapolis. The closest match on Google StreetView is this one here. Tom sent literature on the property, which was then for sale. About the building, it says, “The Church community at the property began in the 1880s when the first sanctuary was built. Then, between 1915 and 1918, a new sanctuary was constructed alongside.” The church was being sold off because its congregation merged with a larger one in 2011.

Still, it could be that Mom and Pop got married at a different Methodist church in Minneapolis. Possibilities:

2125 Thirty Third Avenue North, Minneapolis. According to this 2017 piece in Medium, it is “a church building now housing the Spirit and Truth Worship Center. The original occupant was Grace Methodist Episcopal Church, subsequently Grace United Methodist Church. The original part of the building, on the left of this photo taken from Penn Avenue, dates from 1920.” Here are some historic photos, via the United Methodist Church.Grace United Methodist (often called “Grace–Lowry”) is the building at 2510 Cleveland St NE, on the corner of Cleveland & Lowry, one block west of Taylor St NE. The congregation still meets there today under the name Northeast United Methodist Church. Google’s latest StreetView, in 2023, shows building renovation going on.I’m sure there is correspondence from that time in my sister’s archives or mine that will shed more light on the question. No rush, though. What matters is that the wedding happened, and so did the kids and the grandkids.

August 15, 2025

Questions

What does the Internet make of us? was hard to find until I found it. Now it’s easy to find. What did Google learn, and how did it learn it?

The law professors to whom I made The Case for MyTerms two weeks ago seemed to buy it. What, if anything, will happen next?

When I read The Power of the Swarm: How Collective Intelligence is Reshaping Our World, I thought PI meant personal AI. It means predictive. Which is fine, but we need the personal kind, just like we need personal computers, phones, and shoes. Just saying.

The Consent Management business, which give us cookie notices and all of us hate, is hot and growing. Will MyTerms give it a better reason than consent (which actually fails) to live and grow?

Wholly shit! Github.org, now redirected to Github.com, just turned into a thing that says “Join the world’s most widely adopted AI-powered developer platform.” Is Micorsofting now a verb?

August 14, 2025

The Case for MyTerms

We know more than we can tell.

That was how Michael Polanyi distinguished between tacit and explicit knowing. We may know tacitly how we form speech, ride a bike, or sense when to shake hands with someone, or hug them. But we can’t explain all the signals and mechanisms involved. Not exactly.

In the natural world, privacy is almost entirely based on tacit understandings. Clothing, for example, is a privacy technology that both covers private regions of the body and signals what the person might or might not welcome in respect to those regions. Plus much else, none of which can easily or completely be described explicitly and in detail.

The digital world, however, is entirely explicit. There is no tacit there. As users of tech, we have tacit understandings of how digital things work, but for programming to happen, for logic to operate, we need bits, bytes, and data upon which logical operations can work.

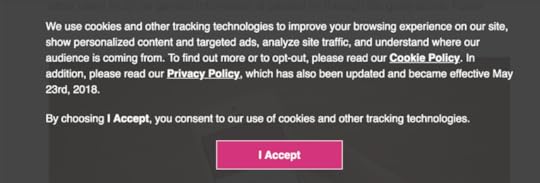

And that is the problem with privacy in the digital world. We don’t have any ways yet to make our privacy requirements explicit. That’s the main reason why it has been almost impossible for marketers to resist spying on us constantly. That’s what has given us the “consent”-based fecosystem we have today, which manifests with shit like this:

These “agreements” do less than nothing to give us privacy, or even the faintest sense of it. Even if a site provides a choice such as this—

—we have no record of our decision, and no faith that it will be respected (unless it’s to allow tracking, which we are right to assume happens anyway).

The status quo here was established in the industrial age, and was best explained by this guy:

Friedrich Kessler (1901-1998) was a self-described legal realist whose most widely cited work was Contracts of Adhesion—Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract (Columbia Law Review, 1943). In it, Kessler argues that contract law is individualistic by nature, and “closely tied up with the ethics of free enterprise capitalism and the ideals of justice of a mobile society of small enterprisers, individual merchants and independent craftsmen.”

Friedrich Kessler (1901-1998) was a self-described legal realist whose most widely cited work was Contracts of Adhesion—Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract (Columbia Law Review, 1943). In it, Kessler argues that contract law is individualistic by nature, and “closely tied up with the ethics of free enterprise capitalism and the ideals of justice of a mobile society of small enterprisers, individual merchants and independent craftsmen.”That economic system, however, was sidelined by giantism in the industrial age, which was already huge in Kessler’s time. He goes on to explain that freedom of contract had become “a one-sided privilege.” Specifically, “Freedom of contract enables enterprisers to legislate by contract and, what is even more important, to legislate in a substantially authoritarian manner without using the appearance of authoritarian forms. Standard contracts in particular could thus become effective instruments in the hands of powerful industrial and commercial overlords enabling them to impose a new feudal order of their own making upon a vast host of vassals.”

That was where we were in 1943, and where we remain today. (Bruce Schneier started writing about the “feudal Internet” twelve years ago.)

The pro forma standard form contract, Kessler explained, forced the weaker party—the ordinary consumer or customer—into “subjection more or less voluntary to terms dictated by the stronger party, terms whose consequences are often understood only in a vague way, if at all.”

He called these agreements “contracts of adhesion,” and “á prendre ou ai laisser” (in English, “take it or leave it”). These contracts are ones the weaker party adheres to and the stronger party can change. So it’s glue for you and me, velcro for the world’s sites and services.

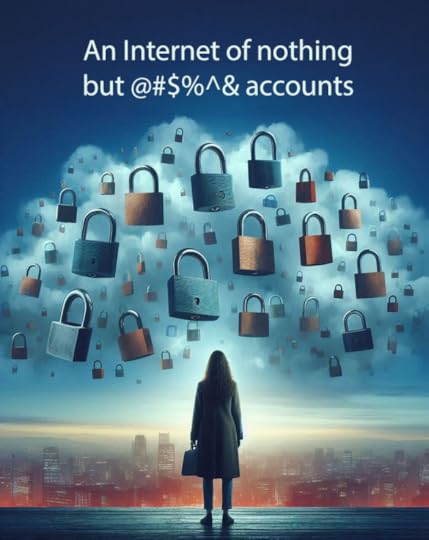

Also, as long as all the sites and services of the world are separately in charge of all their agreements with consumers and customers, the digital world is this:

This is not only a locked-up hell of too many logins, passwords, and second-factor authentication gauntlets. It’s a place where we have an equal number of adhesive “agreements” that aren’t, and which the feudal lords can change while we cannot. Their velcro, our glue.

Are we stuck here? Do we have to be?

No, because there is nothing about digital technology that requires it. And there is lots about digital technology to give us ways of very explicitly designing and programming far better ways to make the digital world work. Also, Kessler explains, the work of the legal realist is “constantly testing out the desirability, efficiency and fairness of inherited legal rules and institutions in terms of the present needs of society.”

I submit that our most pressing present need is to move past surveillance capitalism and into an intention economy where the demand side of the marketplace can better signal its wants, needs, and ability to engage in mutually beneficial ways, and to obtain clear commitments to respect for those. And to do that in ways that are explicit and on which programmatic decisions can be made that all parties know—explicitly—and understand.

If we have that, the supply side can stop spending $trillions on wasteful and unwelcome surveillance-fed guesswork. And we can do that by starting with personal privacy.

I also submit that there is only one way for people to secure a measure of privacy online, and that is through contract. People need to be able to proffer their own privacy terms as first parties to sites and services performing as second parties—and to do that at scale.

And now they can, using a new standard called P7012 IEEE Draft Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, nicknamed MyTerms. (Much as IEEE 802.11 is nicknamed WiFi.) The IEEE approached Customer Commons with the idea for making personal privacy terms machine-readable in 2017. Today the draft is done and due to become official by early next year.

Freedom of contract can be far more useful to both customers and companies than what companies today get out of adhesive contracts and “consents” (such as the one above) that are typically written to obey the letter of privacy laws (such as the GDPR, the DMA, and the CCPA) while violating their spirit.

Here is how MyTerms works:

Lots of business can be built on top of this simple system, which at the ground level starts with service provision without surveillance or unwanted data sharing by the company with other parties. New agreements can be made on top of that, but MyTerms are where genuine and trusting (rather than today’s coerced and one-sided) relationships can be built.

When companies are open to MyTerms agreements, they don’t need cookie notices. Nor do they need 10,000-word terms and conditions or privacy policies because they’ll have contractual agreements with customers that work for both sides.

On top of that foundation, real relationships can be built by VRM systems on the customers’ side and CRM systems on the corporate side. Both can also use AI agents: personal AI for customers and corporate AI for companies. Massive businesses can grow to supply tools and services on both sides of those new relationships. These are businesses that can only grow atop agreements that customers bring to the table, and at scale across all the companies they engage.

Here are some of the possibilities that open up, and I explained at ProjectVRM:

CMPs—Content Management Platforms—can provide sites & services with easy ways to respond to MyTerms choices brought to the table by visitors. Let’s call this a Terms Matching Engine. The current roster of terms we’re working with at Customer Commons (abbreviated CuCo, hence the cuco.org shortcut) starts with CC-BASE, which is “service provision only.” It says to a website, “just give me your service, and nothing more.” In other words, no tracking. Yet. Negotiation toward additional provisions comes after that. Those can be anything, but they should be in the spirit of We’re starting with personal privacy here, and the visitor sets the terms for that.There is a whole new business (which, like the VPN, grammar-help, and password management businesses, people would pay for) in helping people present, manage, remember, and monitor compliance with their terms, and what additional agreements have been arrived at. This can involve browser add-ons such as the one pictured on the ProjectVRM r-button page. CMP companies can make money there too, adding a C2B business to their B2B ones.Go beyond #2 to provide real VRM. Back in the last millennium, Iain Henderson pointed out that B2B relationships tend to have hundreds or thousands of variables over which both parties need to agree. Nitin Badjatia, another CRM veteran (and a Customer Commons board member like Iain and myself), has also pointed out that companies like Oracle have long provided AI-assisted ways for B2B relationships to arrive at contractual agreements. The same can work for C2B, once the base privacy agreement is established. There can be a business here that expands on what gets started with that first agreement.Verticals. There can be strong value-adds for regulated industries or companies wanting to acquire and signal accountability, or look for firmer ways to establish a privacy regime better than the called consent, which doesn’t work (except as thin ass-covering for companies fearing the GDPR and the CCPA). For example: banks, insurers, publishers, health care providers.For people (not just corporate clients), CMPs could offer browser plugins or apps (mobile and/or computer) that help people choose and present their privacy terms, track who honors them, notify them of violations, and have r-buttons mean something. Or multiple things.Here is an example of r-buttons in a browser:

Real relationships, including records of agreements, can be unpacked when a person (not a mere “user”) clicks on either the ⊂ or the ⊃ symbols. There are golden opportunities here for both VRM and CRM vendors. And, of course, companies such as Admiral and OneTrust working both sides—and being truly trusted.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers