Doc Searls's Blog, page 5

August 13, 2025

A Cure for Corporate Addiction to Personal Data

I wrote the original version of this post for the March 2018 issue of Linux Journal. You can find it here. Since images from archival material in the magazine no longer load, and I want to update this anyway, here is a lightly edited copy of the original. Bear in mind that what you’ll read here was at the idea stage seven years ago. Now we’re at the action stage. Let’s make this happen.

Since the turn of the millennium, online publishing has turned into a vampire, sucking the blood of readers’ personal data to feed the appetites of adtech: tracking-based advertising. Resisting that temptation nearly killed us. But now that we’re alive, still human, and stronger than ever, we want to lead the way toward curing the rest of online publishing from the curse of personal data vampirism. And we have a plan. Read on.

This is the first issue of the reborn Linux Journal, and my first as editor-in-chief. This is also our first issue to contain no advertising.

We cut out advertising because the online publishing industry has become cursed by the tracking-based advertising vampire called adtech. Unless you wear tracking protection, nearly every ad-funded publication you visit sinks its teeth into the data jugulars of your browsers and apps, to feed adtech’s boundless thirst for knowing more about you.

Both online publishing and advertising have been possessed by adtech for so long that they can barely imagine how to break free and sober up—even though they know adtech’s addiction to human data blood is killing them while harming everybody else as well. They even have their own twelve-step program.

We believe the only cure is code that gives publishers ways to do exactly what readers want, which is not to bare their necks to adtech’s fangs every time they visit a website.

We’re doing that by reversing the way terms of use work. Instead of readers always agreeing to publishers’ terms, publishers will agree to readers’ terms. Specifically, we’re doing it with a new standard called IEEE P7012—IEEE Draft Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, aka MyTerms.

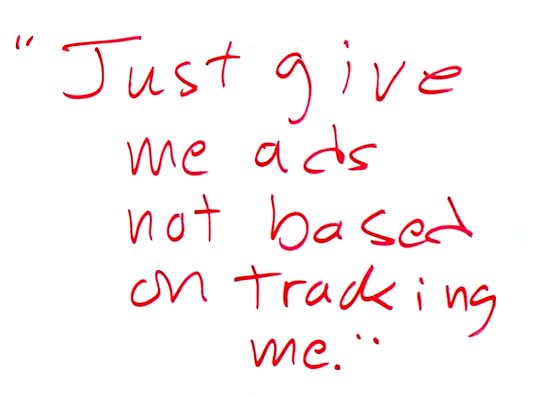

The first of these terms will say something like this:

That scrawled statement appeared on a whiteboard one day at IIW when we were talking about terms readers might proffer to publishers. Let’s call it #NoStalking. Like others of its kind, #NoStalking will live at Customer Commons, which will do for personal terms what Creative Commons does for personal copyright.

Publishers and advertisers can both accept that term, because it’s exactly what advertising has always been in the offline world, and still in the too-few parts of the online world where advertising sponsors publishers without getting personal with readers.

By agreeing to #NoStalking, publishers will also have a stake it can drive into the heart of adtech.

Teeth for enforcing this idea will erupt from the jaws of the EU on 25 May 2018. That’s the day when the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) takes full enforcement effect. The GDPR is aimed at the same data vampires, and its fines for violations run up to 4% of a company’s revenues in the prior fiscal year. It’s a very big deal, and has opened the minds of publishers and advertisers to anything that moves them toward GDPR compliance.

With the GDPR putting fear in the hearts of publishers and advertisers everywhere, the likes of #NoStalking may succeed where DoNotTrack (which the W3C has now ironically relabeled Tracking Preference Expression) failed.

I want to make clear here that we are not against advertising. In fact we rely on it. What we don’t rely on is adtech. Here is the difference:

Real advertising isn’t personal, doesn’t want to be . To do that, adtech spies on people and violates their privacy as a matter of course, and rationalizes it completely, with costs that include becoming a big fat target for bad actors.Real advertising’s provenance is obvious, while adtech messages could be coming from any one of hundreds (or even thousands) of different intermediaries, all of which amount to a gigantic four-dimensional shell game no one entity fully comprehends. Those entities include SSPs, DSPs, AMPs, DMPs, RTBs, data suppliers, retargeters, tag managers, analytics specialists, yield optimizers, location tech providers… the list goes on. And on. Nobody involved—not you, not the publisher, not the advertiser, not even the third party (or parties) that route an ad to your eyeballs—can tell you exactly why that ad is there, except to say they’re sure form of intermediary AI decided it is “relevant” to you, based on whatever data about you, gathered by spyware, reveals about you. Refresh the page and some other ad of equally unclear provenance will appear.Real advertising has no fraud or malware (because it can’t—it’s too simple and direct for that), while adtech is full of both.Real advertising supports journalism and other worthy purposes, while adtech supports “content production”—no matter what that “content” might be. By rewarding content production of all kinds, adtech gives fake news a business model. After all, fake news is “content” too, and it’s a lot easier to produce than the real thing. That’s why real journalism is drowning under a flood of it. Kill adtech and you kill the economic motivation for most fake news. (Political motivations remain, but are made far more obvious.)Real advertising sponsors media, while adtech undermines the brand value of both media and advertisers by chasing eyeballs to wherever they show up. For example, adtech might shoot an Economist reader’s eyeballs with a Range Rover ad at some clickbait farm. Adtech does that because it values eyeballs more than the media they visit. And most adtech is programmed to cheap out on where it is placed, and to maximize repeat exposures wherever it can continue shooting the same eyeballs.In the offline publishing world, it’s easy to tell the difference between real advertising and adtech, because there isn’t any adtech in the offline world, unless we count direct response marketing, better known as junk mail, which adtech actually is.

In the online publishing world, real advertising and adtech look the same, except for ads that feature this symbol:

Only not so big. You’ll only see it as a 16×16 pixel marker in the corner of an ad. So it actually looks like this:

Click on that tiny thing and you’ll be sent to an “AdChoices” page explaining how this ad is “personalized,” “relevant,” “interest-based” or otherwise aimed by personal data sucked from your digital neck, both in real time and after you’ve been tracked by microbes adtech has inserted into your app or browser to monitor what you do.

Text on that same page also claims to “give you control” over the ads you see, through a system run by Google, Adobe, Evidon, TrustE, Ghostery or some other company that doesn’t share your opt-outs with the others, or provide any record of the “choices” you’ve made. In other words, together they all expose what a giant exercise in misdirection the whole thing is. Because unless you protect yourself from tracking, you’re being followed by adtech for future ads aimed at your eyeballs using source data sucked from your digital neck.

By now you’re probably wondering how adtech came to displace real advertising online. As I put it in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff, “Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself.” That happened because Madison Avenue, like the rest of big business, developed a big appetite for “big data,” starting in the late ’00s. (I unpack this history in my EOF column in the November 2015 Linux Journal.)

Madison Avenue also forgot what brands are and how they actually work. After a decade-long trial by a jury that included approximately everybody on Earth with an Internet connection, the verdict is in: after a $trillion or more has been spent on adtech, no new brand has been created by adtech; nor has the reputation of an existing brand been enhanced by adtech. Instead, adtech damages a brand every time it places the brand’s ad next to fake news or on a crappy publisher’s website.

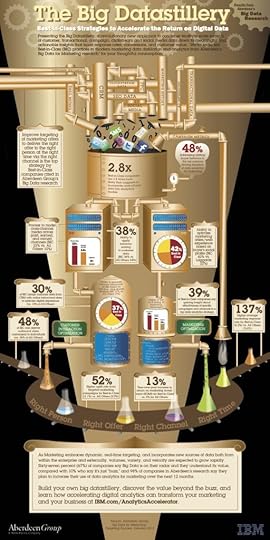

In Linux vs. Bullshit, which ran in the September 2013 Linux Journal, I pointed to a page that still stands as a crowning example of how much of a vampire the adtech industry and its suppliers had already become: IBM and Aberdeen‘s The Big Datastillery: Strategies to Accelerate the Return on Digital Data. That link goes to the Internet Archive snapshot of the page. Give it time to load. If it doesn’t, go here. Or just click on this .jpg I just made from the .pdf verion of the thing:

The “datastillery” is a giant vat modeled on a whiskey distillery. Going into the top are pipes of data labeled “clickstream data,” “customer sentiment,” “email metrics,” “CRM” (customer relationship management), “PPC” (pay per click), “ad impressions,” “transactional data,” and “campaign metrics.” All that data is personal, and little if any of it has been gathered with the knowledge or permission of the persons it concerns.

At the bottom of the vat, distilled marketing goop gets spigoted into beakers rolling by on a conveyor belt through pipes labeled “customer interaction optimization” and “marketing optimization.” Those beakers are human beings.

Farther down the conveyor belt, exhaust from goop metabolized in the human beakers is farted upward into an open funnel at the bottom end of the “campaign metrics” pipe, through which it flows up to the top and is poured back into the vat.

Look at this image as an MRI of the vampire’s digestive system, or a mirror in which the reflections of IBM’s and Aberdeen’s images fail to appear because their humanity is gone.

No wonder ad blocking became the largest boycott in human history by 2015. Here’s how large:

PageFair’s 2017 Adblock Report says at least 615 million devices were already blocking ads by then. That number is larger than the human population of North America.GlobalWebIndex says 37% of all mobile users worldwide were blocking ads by January 2016, and another 42% would like to. With more than 4.6 billion mobile phone users in the world, that means 1.7 billion people were blocking ads already—a sum exceeding the population of the Western Hemisphere.Naturally, the adtech business and its dependent publishers cannot imagine any form of GDPR compliance other than continuing to suck its victims dry while adding fresh new inconveniences along those victims’ path to adtech’s fangs—and then blaming the GDPR for delaying things.

A perfect example of this non-thinking is a recent Business Insider piece that says “Europe’s new privacy laws are going to make the web virtually unsurfable” because the GDPR and ePrivacy (the next legal shoe to drop in the EU) “will require tech companies to get consent from any user for any information they gather on you and for every cookie they drop, each time they use them,” thus turning the Web “into an endless mass of click-to-consent forms.”

Speaking of endless, the same piece says, “News sites — like Business Insider — typically allow a dozen or more cookies to be ‘dropped’ into the web browser of any user who visits.” That means a future visitor to Business Insider will need to click “agree” before each of those dozen or more cookies gets injected into the visitor’s browser.

After reading that, I decided to see how many cookies Business Insider actually dropped in my Chrome browser when that story loaded, or at least tried to. Here’s what Baycloud Bouncer reported:

That’s ten dozen cookies.

This is in addition to the almost complete un-usability Business Insider achieves with adtech already. For example,

On Chrome, Business Insider‘s third party adtech partners take forever to load their cookies and auction my “interest” (over a 320MBp/s connection), while populating the space around the story with ads—just before a subscription-pitch paywall slams down on top of the whole page like a giant metal paving slab dropped from a crane, making it unreadable on purpose and pitching me to give them money before they life the slab.The same thing happens with Firefox, Brave, and Opera, though not at the same rate, in the same order, or with the same ads. All drop the same paywall, though. It’s hard to imagine a more subscriber-hostile sales pitch.Yet I could still read the piece by looking it up in a search engine. It may also be elsewhere, but the copy I find is on MSN. There, the piece is also surrounded by ads, which arrive along with cookies dropped in my browser by only 113 third-party domains. Mercifully, no subscription paywall slams down on the page.So clearly, the adtech business and its publishing partners are neither interested in fixing this thing, nor competent to do it.

But one small publisher can start. That’s us. We’re stepping up.

Here’s how: by reversing the compliance process. By that I mean we are going to agree to our readers’ terms of data use, rather than vice versa. Those terms will live at Customer Commons, which is modeled on Creative Commons. Look for Customer Commons to do for personal terms what Creative Commons did for personal copyright licenses.

It’s not a coincidence that both came out of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. The father of Creative Commons is law professor Lawrence Lessig, and one of Customer Commons’ parents is me. In the great tradition of open source, I borrowed as much as I could from Larry and friends.

For example, Customer Commons’ terms will come in three forms of code (which I illustrate with the same graphic Creative Commons uses):

Legal Code is being baked by Customer Commons’ counsel: Harvard Law School students and teachers working for the Cyberlaw Clinic at the Berkman Klein Center.

Human Readable text will say something like “Just show me ads not based on tracking me.” That’s the one we’re dubbing #DoNotByte.

For Machine Readable code, we now have a working project at the IEEE: 7012 – Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms. There it says,

The purpose of the standard is to provide individuals with means to proffer their own terms respecting personal privacy, in ways that can be read, acknowledged and agreed to by machines operated by others in the networked world. In a more formal sense, the purpose of the standard is to enable individuals to operate as first parties in agreements with others—mostly companies—operating as second parties.

That’s in addition to the protocol and a way to record agreements that JLINCLabs or some other protocol will provide.

And we’re wide open to help in all those areas.

Here’s what agreeing to readers’ terms does for publishers:

Provide real GDPR compliance , by recording the publisher’s agreement with the reader not to track them. Note that contract is one of the six lawful reasons the GDPR lists for processing personal data. See item (b) here. Note that (a) is for consent, which is clearly now a fail. Put publishers back on a healthy diet of real (tracking-free) advertising . Which should be easy to do because that’s what all of advertising was before publishers, advertisers and intermediaries turned into vampires. Restore publishers’ status as good media for advertisers to sponsor , and on which to reach high-value readers. Model for the world a complete reversal of the “click to agree” process . This way we can start to give readers scale across many sites and services. Pioneer a whole new model for compliance , where sites and services comply with what people want, rather than the reverse (which we’ve had since industry won the Industrial Revolution). Raise the value of tracking protection for everybody . In the words of Don Marti, “publishers can say, ‘We can show your brand to readers who choose not to be tracked.'” He adds, “If you’re selling VPN services, or organic ale, the subset of people who are your most valuable prospective customers are also the early adopters for tracking protection and ad blocking.”But mostly, we get to set an example that publishing and advertising both desperately need. It will also change the world for the better.

You know, like Linux did for operating systems.

Now, eight years after the MyTerms working group started drafting its standard, the draft is finished and likely to be published early next year. Meanwhile, there is nothing to stop work based on that standard, which is simplified here.

By the way, third-party tracking is disallowed in all thirteen of Customer Commons’ current set of draft agreements (which we hope to publish soon). The base agreement, currently nicknamed CC-BASE, says “service provision only.” This is what we experience in the natural world. If your business is selling clothes, we expect to see clothes, not to get infected with spyware. If one wants some spyware later, that offer can go on the table later.

MyTerms is the table on which future agreements are set, under the complete control of the individual operating as the first party—and at scale across all the sites and services the individual engages.

The only way we will ever get full agency in the digital world is through contracts. Full stop. And full start.

August 2, 2025

It was real

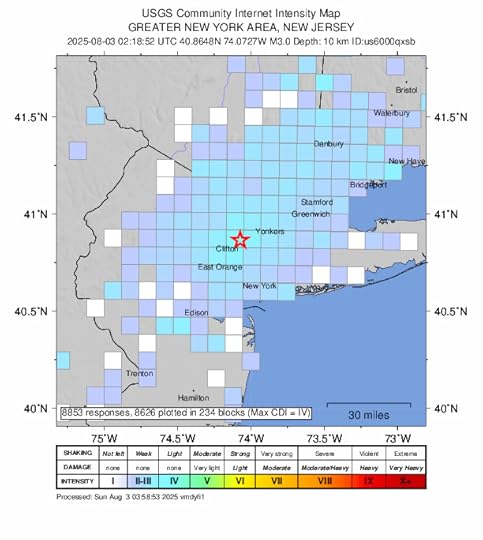

I grew up under the red star, and right now I’m just to the right of it, on the third and top floor of the smallest residential building in northern Manhattan.

When it hit, my wife and I both said, “That’s an earthquake.” We’ve experienced many in California, and know the feel.

But none of the quake sources online noted it in real time, or close.

Now the details are in. Nothing big, just interesting.

Getting Real With AI.

The incorporeal non-place where we also live. By Hugh McLeod, 2004.

The incorporeal non-place where we also live. By Hugh McLeod, 2004.When I read that some conversations with ChatGPT had appeared in Google searches, I did a search for “Doc Searls” ChatGPT and got a long and not-bad but not entirely accurate AI summary below which normal-ish search results appeared. When I went back later to do the same search, the results were different. I tried the exercise again in another browser and again got different results. I also found no trace of personal chats with ChatGPT surfacing on Google. But with returns diminishing that fast, why bother to keep looking?

What I did come to realize, quickly, is that there is no “on” anymore with Google. And there may never be an “on” with AI as it seems to be playing out.

There is also no “on” in “online.” No “in.”

We use adpositions, which include prepositions, to make sense of the natural world. They are made for our embodied selves. Under, around, through, beside, within, beneath, above, into, near, toward, with, outside, amid, beyond (and dozens more) make full sense where we eat, breathe, use all five of our senses. In the natural world up truly is up, and down is down, because we have distance and gravity here. We don’t have distance or gravity in the digital world. But the digital world is no less real for the absence of distance, gravity, substance, shape, and everything we can see, smell, hear, weigh, touch, and feel here in the natural world.

Cyberspace is beyond ironic. It is oxymoronic, self-contradictory. It’s a spaceless non-place except in an abstract way. When people in Sydney, Lucerne, New York, and Tokyo meet on (or through, or with—pick your inadequate preposition) Zoom, they are not in (or of, or whatever) a where in the physical sense. They are co-present in the non-space that Craig Burton called a giant zero: a hollow virtual sphere across which any two points can see each other.

But we treat this zero as a real place, because we have to. Hence the real estate metaphors: domains with locations on sites where we construct or build the non-things we call homes. And it all goes pfft into nothingness when we fail to pay our virtual landlords (e.g. domain registrars and hosting companies) to keep it up. And nothing is permanent. All those domain names and home spaces are rented, not owned.

All these thinkings came to mind this morning when I read two pieces:

Peter Thiel Just Accidentally Made a Chilling Admission. Five Decades Ago, One Man Saw It Coming. By Nick Ripatrazone in Yahoo NewsWhat’ll happen if we spend nearly $3tn on data centres no one needs? by somebody behind the FT paywall. But I could read it here, so I did, and maybe you can too.The first speaks to living disembodied lives along with our embodied ones.

The second speaks to the mania for Big AI spend:

It’s also worth breaking down where the money would be spent. Morgan Stanley estimates that $1.3tn of data centre capex will pay for land, buildings and fit-out expenses. The remaining $1.6tn is to buy GPUs from Nvidia and others. Smarter people than us can work out how to securitise an asset that loses 30 per cent of its value every year, and good luck to them.

Where the trillions won’t be spent is on power infrastructure. Morgan Stanley estimates that more than half of the new data centres will be in the US, where there’s no obvious way yet to switch them on.

I now think at least some of that money will be far better spent on personal AI.

That’s AI for you and me, to get better control of our lives in the natural world where we pay bills, go to school, talk to friends, get sick and well, entertain ourselves and others, and live lives thick with data over which we have limited control at most. Do you have any record of all your subscriptions, your health and financial doings and holdings, what you’ve watched on TV, where you’ve been, and with whom? Wouldn’t it be nice to have all that data handy, and some AI help to organize and make sense of it? I’m talking here about AI that’s yours and works for you. Not a remote service from some giant that can do whatever it pleases with your life.

It’s as if we are back in 1975, but instead of starting to work on the personal computer, all the money spent on computing goes into making IBM and the BUNCH more gigantic than anything else ever, with spendings that dwarf what might be spent on simple necessities, such as the electric grid and roads without holes. Back then, we at least had the good fortune of Jobs, Wozniac, Osborne, and other mammals working on personal computing underneath the feet of digital dinosaurs. Do we have the same people working on personal AI today? Name them. I’m curious.

Note that I’m not talking about people working on better ways to buy stuff, or to navigate the digital world with the help of smart agents. I’m talking about people working on personal (not personalized) AI that will give us ways to get control of our everyday lives, without the help of giants.

Like we started doing with personal computers fifty years ago.

July 26, 2025

In fewest words, yes.

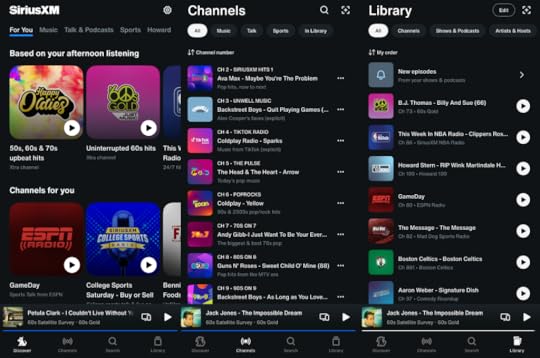

When I just opened the app, I got the screen on the left. Since I wasn’t listening this afternoon, it made no sense. The one in the middle appeared when I returned to the app. It just lists channels, starting at the bottom (from which they annoyingly moved “Fifties on 5” and “Sixties on 6” to other channels), and then shows me the right screen when I hit Library, which used to have the much more sensible label “Favorites.” I hate the whole mess, but that’s beside the point of this post, so read on.

When I just opened the app, I got the screen on the left. Since I wasn’t listening this afternoon, it made no sense. The one in the middle appeared when I returned to the app. It just lists channels, starting at the bottom (from which they annoyingly moved “Fifties on 5” and “Sixties on 6” to other channels), and then shows me the right screen when I hit Library, which used to have the much more sensible label “Favorites.” I hate the whole mess, but that’s beside the point of this post, so read on.Here is my answer to the question Does SiriusXM know what station you are listening to?

The SiriusXM streaming app logs what you listen to, when, and how you interact with programs and channels across your devices (phone, pad, smart speaker, website through your browser, whatever).

This data is used to personalize your “experience” (as the marketers like to say), sync your profile across devices, and support marketing efforts (which these days are mostly surveillance-based) while maintaining “pseudonymous tracking.”

Older SiriusXM radios (before about 2020) had no return path for usage data to flow to the company, but almost all new cars have their own cellular data connections (over which you have no control) for reporting many kinds of driving and usage data, including what you do with your car’s infotainment system.

Your SiriusXM radio use is among the many forms of personal data being reported by your car to its maker and to other parties known and unknown. To explain this, the SiriusXM privacy policy provides, in the current business fashion, what Paul Simon (in “The Boxer”) calls “a pocket full of mumbles such are promises.”

All that said, there isn’t much in my experience of SiriusXM to suggest that I am being understood much in any way by the system. There are many more of what used to be called “favorites” in the Library. But there is no obvious order to how and why they appear where they do on the list. I have other complaints, but none are worth going into. And I’ve already posted my biggest complaint in How to Make Customers Hate You.

New Life for LIVE

Colbert’s cancellation looks political, but it’s not. The show was a ratings winner, but a money loser. And the ratings for all of late night, like all of live TV, have been in decline for decades, along with the question, “What’s on?”

We live in the Age of Optionality now. Watch or listen to whatever you want, whenever you want, on whatever you want.

Except for sports, news, and Saturday Night Live, live programming is disappearing from radio and TV. Meanwhile, radio and TV themselves are being sidelined by apps on phones, flat screens, smart speakers, and CarPlay/Android Auto.

Fact: The only thing that makes your TV a TV is the cable/antenna jack in the back. Otherwise, it’s a monitor with a computer optimized for clickbait and spying on you. The clickbait is the (often spying-based) “for you” shit, plus what the industry calls FAST (Free Ad-Supported Streaming Television) channels: old westerns, local TV from elsewhere, looping news from services you never heard of, hustlers selling junk, foreign language programs, a fireplace that doesn’t go out, plus other crap.

Broadcasting has devolved from Macy’s to Dollar General.

But live programming is still with us. It’s just not on TV or radio, just like food trucks aren’t in buildings. At this stage what we have are pop-up shows with very high harbinger ratings and uncertain persistence. Here are a few I just looked up:::

Newsletter WritersCasey Newton (Platformer)Matt Taibbi (Racket News)Heather Cox Richardson (Letters from an American)Anne Helen Petersen (Culture Study)Emily Atkin (Heated)Puck News team (e.g. Dylan Byers, Teddy Schleifer)Influencers (Mostly on TikTok and Instagram)TinxChris OlsenBretman RockTabitha BrownCelebrities (on YouTube, Substack, TikTok, X Spaces, etc.)Andrew CallaghanMarc MaronHank GreenElon Musk & David SacksWritersTim Urban (Wait But Why)Bari Weiss (The Free Press)Douglas Rushkoff (Team Human)Since I’m not on TikTok and barely on Instagram, I know none of the influencers I just listed with a bit of AI help. If I have time later, I’ll add links.

Meanwhile, the writing isn’t just on the wall for live old-school broadcasting. The wall is falling down, and new ones are being built all over the place by creative voices and faces themselves. Welcome to Now.

July 22, 2025

How about ASO, for Attention Surfeit Order?

Royal Society: Attention deficits linked with proclivity to explore while foraging. To which Thom Hartman adds, The Science Catches Up: New Research Confirms ADHD as an Evolutionary Advantage, Not a Disease.

Which I've always believed. But that didn't make me normal. Far from it.

In my forties and at my wife’s urging (because my ability to listen well and follow directions was sub-optimal), I spent whole days being tested for all kinds of what we now call neurodivergent conditions. The labels I came away with were highly qualified variants of ADHD and APD. Specifics:

I was easily distracted and had trouble listening to and sorting out instructions for anything. (I still have trouble listening to the end of a long joke.)On puzzle-solving questions, I was very good.My smarts with spatial and sequence puzzles were tops, as was my ability to see and draw patterns, even when asked to remember and rotate them 90° or 180°.My memory was good.I had “synchronization issues,” such as an inability to sing and play drums at the same time. This also involved deficiencies around “cognitive overload,” “context switching,” multitasking, coping with interruptions, and “bottlenecks” in response selection. They also said I had become skilled at masking all those problems, to myself and others. (While I thought I was good at multitasking, they told me, "You're in the bottom 1%.")I could easily grasp math concepts, but I made many mistakes with ordinary four-function calculations.I did much better at hearing and reading long words than short ones, and I did better reading wide columns of text than narrow ones.When asked to read out loud a simple story composed of short and widely spaced words in a narrow column, I stumbled through it and remembered little of the content afterward. They told me that if I had been given this test alone, they would have said I had trouble reading at a first-grade level, and I would have been called (as they said in those days) mentally retarded.My performance on many tests suggested dyslexia, but my spelling was perfect, and I wasn’t fooled by misplaced or switched letters in words. They also said that I had probably self-corrected for some of my innate deficiencies, such as dyslexia. (I remember working very hard to become a good speller in the fourth grade, just as a challenge to myself. Not that the school gave a shit.) They said I did lots of “gestalt substitution,” when reading out loud, for example, replacing “feature” with “function,” assuming I had read the latter when in fact I’d read the former.Unlike other ADHD cases, I was not more impulsive, poorly socialized, or easily addicted to stuff than normal people. I was also not hyperactive, meaning I was more ADD than ADHD.Like some ADHD types, I could hyperfocus at times.My ability to self-regulate wasn’t great, but it also wasn’t bad. Just a bit below average. (So perhaps today they’d call me ADHD-PI, a label I just found in Wikipedia).The APD (auditory processing disorder) diagnosis came mostly from hearing tests. But, as with ADHD, I only hit some of the checkboxes. (Specifically, about half of the ten symptoms listed here.)My ability to understand what people say in noisy settings was in the bottom 2%. And that was when my hearing was still good.So there's no good label for me, but…

July 20, 2025

Good read

I just got turned on to Paul Ford's What is Code, from 2015, but still current today. Shoulda been a book, like Neal Stephenson's In the Beginning Was the Command Line. You can still find the text online, such as here.

Nice, I hope

That "intention economy" appears (in a positive way) in this story from South Africa, in IOL.

July 18, 2025

One reason I love Indiana

My car's dashboard has been telling me we have a slow leak in the right front tire. So I drove up to Tieman Tire here in Bloomington. It was busy, but they took me as a walk/drive-in, and then took an hour to remove the tire, find the leak in a tub of water (which wasn't easy, because the leak was too sphinctered to make bubbles: they had to feel in and on the tread all around the tire to locate the leak, which was from a tiny nail), remove and patch the tire, balance it, and torque it back onto the car… and then to make sure all four tires and the spare were all properly inflated—all with some enjoyable and informative shop-talk about cars and tires.

Price: $20.

They now have me as a loyal customer.

Dame Time!

I love that Damien Lillard is returning to the Portland Trailblazers. He and the town love each other, and the team is already on the ascent. It's a great move.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers