Doc Searls's Blog, page 39

October 17, 2020

Time to unscrew subscriptions

The goal here is to obsolesce this brilliant poster by Despair.com:

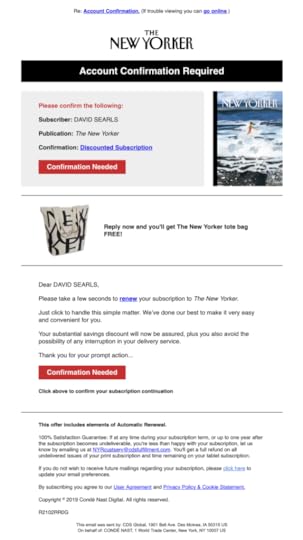

I got launched on that path a couple months ago, when I got this email from The_New_Yorker at e-mail.condenast.com:

Why did they “need” a “confirmation” to a subscription which, best I could recall, was last renewed early this year?

So I looked at the links.

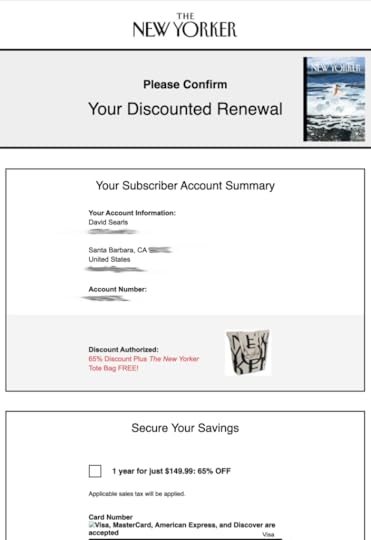

The “renew,” Confirmation Needed” and “Discounted Subscription” links all go to a page with a URL that began with https://subscriptions.newyorker.com/pubs…, followed by a lot of tracking cruft. Here’s a screen shot of that one, cut short of where one filled in a credit card number. Note the price:

I was sure I had been paying $80-something per year, for years. As I also recalled, this was a price one could only obtain by calling the 800 number at NewYorker.com.

Or close. I finally found it at

https://w1.buysub.com/pubs/N3/NYR/accoun…, which is where the link to Customer Care under My Account on the NewYorker website goes. It also required yet another login.

So, when I told the representative at the call center that I’d rather not “confirm” a year for a “discount” that probably wasn’t, she said I could renew for the $89.99 I had paid in the past, and that the deal would be good through February of 2022. I said fine, let’s do that. So I gave her my credit card, and had the conversation I mention at the top of this post, when I suggested that this was way too complicated, adding that a single simple subscription price would be better, and to which she replied, “Never gonna happen.”

Then I got this by email:

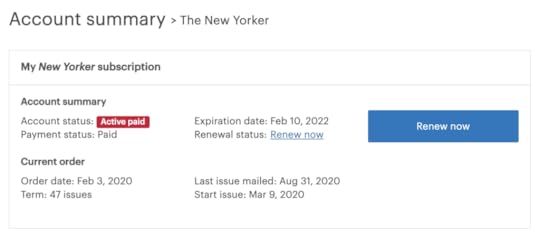

This appeared to confirm the subscription I already had. To see if that was the case, I went back to the buysub.com website and looked under the Account Summary tab, where it said this:

I think this means that I last renewed on February 3 of this year, and what I did on the phone in August was commit to paying $89.99/year until February 10 of 2022.

If that’s what happened, all my call did was extend my existing subscription. Which was fine, but why require a phone call for that?

And WTF was that “Account Confirmation Required” email about? I assume it was bait to switch existing subscribers into paying $50 more per year.

Then there was this, at the bottom of the Account summary page:

This might explains why I stopped getting Vanity Fair, which I suppose I should still be getting.

So I clicked on”Reactivate and got a login page where the login I had used to get this far didn’t work.

After other failing efforts that I neglected to write down, I decided to go back to the New Yorker site and work my way back through two logins to the same page, and then click Reactivate one more time. Voila! ::::::

So now I’ve got one page that tells me I’m good to March 2021 next to a link that takes me to another page that says I ordered 12 issues last December and I can “start” a new subscription for $15 that would begin nine months ago. This is how one “reactivates” a subscription? OMFG.

I’m also not going into the hell of moving the print subscription back and forth between the two places where I live. Nor will I bother now, in October, to see why I haven’t seen another copy of Vanity Fair. (Maybe they’re going to the other place. Maybe not. I don’t know.)

I want to be clear here that I am not sharing this to complain. In fact, I don’t want The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Wred, Condé Nast (their parent company) or buysub.com to do a damn thing. They’re all FUBAR. By design. (Bonus link.)

Nor do I want any action out of Spectrum, SiriusXM, Dish Network or the other subscription-based whatevers whose customer disservice systems have recently soaked up many hours of my life.

See, with most subscription systems, FUBAR is the norm. A matter of course. Pro forma. Entrenched. A box outside of which nobody making, managing or working in those systems can think.

This is why, when an alien idea appears, for example from a loyal customer just wanting a single and simple damn price, the response is “Never gonna happen.”

This is also why the subscription fecosystem can only be turned into an ecosystem from the outside. Our side. The subscribers’ side.

I’ll explain how at Customer Commons, which we created for exactly that purpose. Stay tuned for that.

Two exceptions are Consumer Reports and The Sun.

October 15, 2020

Higher education adrift

In Your favorite cruise ship may never come back: 23 classic vessels that could be laid-up, sold or scrapped, Gene Sloan (aka @ThePointsGuy) named the Carnival Fantasy as one those that might be headed for the heap. Now, sure enough, there it is, in the midst of being torn to bits (HT 7News, above) in Aliağa, Turkey. Other stories in the same vein are here, here, here, here, here and here.

I been on a number of cruises (here’s one) in the course of my work as a journalist, and I’ve enjoyed them all. I’ve also hung out at a similar number of colleges and universities, and have long found myself wondering how well the former might be a good metaphor for the latter. Both are expensive, well-branded and self-contained structures with a lot of specialized staff and overhead. Both are also vulnerable to pandemics, and in doomed cases their physical components turn out to be worth more than their institutional ones. John Naughton also notes the resemblance. But it’s Scott Galloway who runs all the way with it; first with Higher Ed: Enough Already, and then with a long and research-filled post titled USS University, featuring this title graphic:

Those three schools are adrift across a 2×2 with low valuehigh value on the X axis and high vulnerabilitylow vulnerability on the Y axis. At the lower left are the low-value/high vulnerability schools in a quadrant Scott calls “challenged,” meaning . Among those are—

Adelphi

Brandeis

Bard

Dickenson

Dennison

Hofstra

Kent State

Kenyon

LIU

Mt. Holyoke

Old Dominion

Pace

Pacific

Robert Morris

Sarah Lawrence

Seton Hall

Skidmore

Smith

St. John’s (Maryland & New Mexico)

The New School

Union

UC Santa Cruz

U Mass Dartmouth

Valparaiso

Wittenberg

— plus a plethora of mostly state-run “directional” schools (e.g. University of Somewhere at Somewhere).

These “challenged” schools, Scott says, are afflicted by the “sodium pentathol cocktail of high admit rates, high tuition, low endowments, dependence on international students, and weak brand equity.” Seems a bit harsh, since I’d say a third of those (Bard, Brandeis, Kenyon, Smith) have good brand equity. (According to me, anyway.) Still, a question looms: how many have more value as real estate than as what they are today?

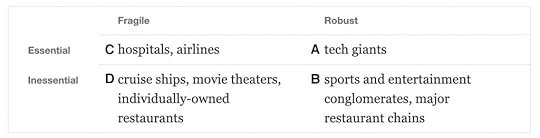

I started wondering in the same direction in May, when I posted Figuring the Future and Choose One. Both pivoted off this 2×2 by Arnold Kling—

On Arnold’s rectangle, D (Fragile/Inessential) is Scott’s “challenge” quadrant. What I’m wondering, now that school as started and at least some results should be coming in (or at least trending in a direction), if any colleges or universities are headed already toward their own Aliağa.

Thoughts? If so, let me know on Twitter (where I am @dsearls), Facebook (here) or by email (doc at searls dot com). I hope to have comments working again here soon, but for now they don’t, alas.

September 28, 2020

Remembering Gail Sheehy

It bums me out that Gail Sheehy passed without much notice—meaning I only heard about it in passing. And I didn’t hear about it, actually; I saw it on CBS’ Sunday Morning, where her face passed somewhere between Tom Seaver’s and John Thompson’s in the September 6 show’s roster of the freshly dead. I was shocked: She was older than both those guys and far less done. Or done at all, except technically. Death seems especially out of character for her, of all people.

It bums me out that Gail Sheehy passed without much notice—meaning I only heard about it in passing. And I didn’t hear about it, actually; I saw it on CBS’ Sunday Morning, where her face passed somewhere between Tom Seaver’s and John Thompson’s in the September 6 show’s roster of the freshly dead. I was shocked: She was older than both those guys and far less done. Or done at all, except technically. Death seems especially out of character for her, of all people.

Credit where due: The New York Times did post a fine obituary, and New York, for which she wrote much, has an excellent remembrance in the magazine by Christopher Bonanos (@heybonanos). Writes Bonanos,

Sheehy had an 18th book in the works, and it would have been — or will be, if someone else takes to the finish line — a fascinating one. Instead of reporting amid her peers (she was a few years older than the boomers, but roughly in their cohort), she set out to write a kind of echo of Passages, but this time about the millennial generation. And I can tell you that she was reveling in the immersion among people 50 and 60 years younger than she. She went to clubs with college guys and got out on the dance floor, and (by her account, at least) they were disarmed and amused by her — which is to say that she’d found every journalist’s sweet spot, where people get loose and comfortable enough to reveal themselves. She was constantly offering bits and pieces of her findings as magazine stories and columns. Some would work as stand-alone pieces and others wouldn’t, but all were tesserae in what was clearly going to be a big ambitious swoop of sociology. At New York, we were so taken with this project that we had also begun work on a profile of her…

@Gail_Sheehy is chronologically uncorrected. Her website, GailSheehy.com, also still speaks of her in the present tense: “For her new book-in-progress, she’s a woman on a mission to redefine the most misunderstood generation: millennials. They are struggling with the rupture in gender roles and a crisis in mental health. But this generation of 20- and 30-somethings is also inventing radically new passages.”

Gail Sheehy’s writing isn’t just solid; it is enviably good. BrainyQuotes has 71 samples, which is far short of sufficient. One goes, It is a paradox that as we reach our prime, we also see there is a place where it finishes. (Tell me about it. I’m only ten years younger than she was.)

As it happens, I’m writing this in the home library of a friend. On its many shelves a single spine stands out: Pathfinders, published in 1981. I pull it down and open it at random, knowing I’ll find something worth sharing from a page there. Here ya go, under the subhead Secrets of Well-being:

Like the dance of brilliant reflections on a clear pond, well-being is a shimmer that accumulates from many important life choices, mad over the years by a mind that is not often muddied by pretense or ignorance and a heart that is open enough to sense people in their depths and to intuit the meaning of most situations.

If there is an afterlife, I am sure Gail Sheehy is already reporting on it.

September 26, 2020

How early is digital life?

Bits don’t leave a fossil record.

Bits don’t leave a fossil record.

Well, not quite. They do persist on magnetic, optical and other media, all easily degraded or erased. But how long will those last?

Since I’ve already asked that question, I’ll set it aside and ask the one in the headline.

Some perspective: depending on when you date its origins, digital life—the one we live by extension through our digital devices, and on the Internet (which, like The Force, connects nearly all digital things)—is decades old.

It’s an open question how long it will last. But I’m guessing it will be more than a few more decades. More likely we will remain partly digital for centuries or millennia.

So I’m looking for guesses more educated than mine.

Since this blog no longer takes comments from outside of Harvard (and I do want to fix that), please tag your responses, wherever they may be on the Internet with #DigitalLife. Thanks.

September 22, 2020

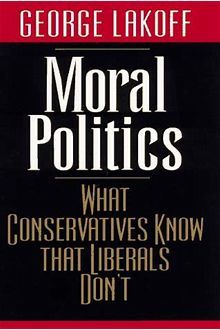

On Moral Politics

I spent 17 minutes while exercising the other day, thinking out loud about what @GeorgeLakoff says in his 1996 book Moral Politics: What Conservatives Know That Liberals Don’t, (also in his expanded 2016 edition, re-subtitled How Liberals and Conservatives Think). I also tweeted about the book this morning here. In it I explain what pretty much nobody else is saying about Trump, Biden, and how each actually appeals to their voters (and those in between).

I spent 17 minutes while exercising the other day, thinking out loud about what @GeorgeLakoff says in his 1996 book Moral Politics: What Conservatives Know That Liberals Don’t, (also in his expanded 2016 edition, re-subtitled How Liberals and Conservatives Think). I also tweeted about the book this morning here. In it I explain what pretty much nobody else is saying about Trump, Biden, and how each actually appeals to their voters (and those in between).

Here’s the audio file:

http://blogs.harvard.edu/doc/files/2020/09/2020_09_09_lakoff-moral-politics.mp3

This blog no longer takes comments, alas, so post a response elsewhere, if you like, or write me. I’m doc @ my surname dot com.

September 18, 2020

Saving Mount Wilson

This was last night:

And this was just before sunset tonight:

From the Mt. Wilson Observatory website:

Mount Wilson Observatory StatusAngeles National Forest is CLOSED due to the extreme fire hazard conditions. To see how the Observatory is faring during the ongoing Bobcat fire, check our Facebook link, Twitter link, or go to the HPWREN Tower Cam and click on the second frame from the left at the top, which looks east towards the fire (also check the south-facing cam and the recently archived timelapse movies below which offer a good look at the latest events in 3-hour segments. Note to media: These images can be used with credit to HPWREN). For the latest updates on the Bobcat fire from U.S. Forest Service, please check out their Twitter page.

Last night the firefighters set a strategic backfire to make a barrier to the fire on our southern flank. To many of us who did not know what was happening it looked like the end. Click here to watch the timelapse. The 12 ground crews up there have now declared us safe. They will remain to make sure nothing gets by as the fires tend to linger in the canyons below. They are our heroes and we owe them our existence. They are true professionals, artists with those backfires, and willing to put themselves at considerable risk to protect us. We thank them!!!!

There will be plenty of stories about how the Observatory and the many broadcast transmitters nearby were saved from the Bobcat Fire. For the curious, start with these links:

Mt. Wilson Observatory website

Tweets from the Mount Wilson Observatory

Tweets from the Angeles National Forest

Space.com’s report on the event

I’ll add some more soon.

September 10, 2020

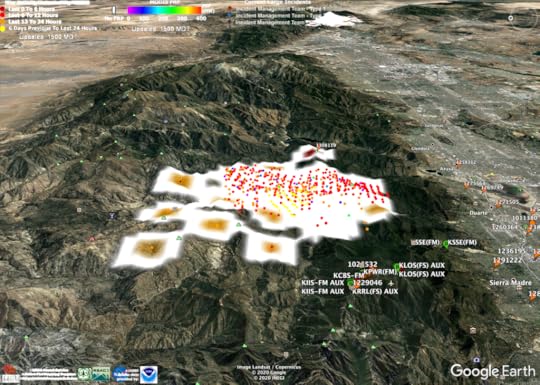

On fire

The white mess in the image above is the Bobcat Fire, spreading now in the San Gabriel Mountains, against which Los Angeles’ suburban sprawl (that’s it, on the right) reaches its limits of advance to the north. It makes no sense to build very far up or into these mountains, for two good reasons. One is fire, which happens often and awfully. The other is that the mountains are geologically new, and falling down almost as fast as they are rising up. At the mouths of valleys emptying into the sprawl are vast empty reservoirs—catch basins—ready to be filled with rocks, soil and mud “downwasting,” as geologists say, from a range as big as the Smokies, twice as high, ready to burn and shed.

Outside of its northern rain forests and snow-capped mountains, California has just two seasons: fire and rain. Right now we’re in the midst of fire season. Rain is called Winter, and it has been dry since the last one. If the Bobcat fire burns down to the edge of Monrovia, or Altadena, or any of the towns at the base of the mountains, heavy winter rains will cause downwasting in a form John McPhee describes in Los Angeles Against the Mountains:

The water was now spreading over the street. It descended in heavy sheets. As the young Genofiles and their mother glimpsed it in the all but total darkness, the scene was suddenly illuminated by a blue electrical flash. In the blue light they saw a massive blackness, moving. It was not a landslide, not a mudslide, not a rock avalanche; nor by any means was it the front of a conventional flood. In Jackie’s words, “It was just one big black thing coming at us, rolling, rolling with a lot of water in front of it, pushing the water, this big black thing. It was just one big black hill coming toward us.

In geology, it would be known as a debris flow. Debris flows amass in stream valleys and more or less resemble fresh concrete. They consist of water mixed with a good deal of solid material, most of which is above sand size. Some of it is Chevrolet size. Boulders bigger than cars ride long distances in debris flows. Boulders grouped like fish eggs pour downhill in debris flows. The dark material coming toward the Genofiles was not only full of boulders; it was so full of automobiles it was like bread dough mixed with raisins. On its way down Pine Cone Road, it plucked up cars from driveways and the street. When it crashed into the Genofiles’ house, the shattering of safety glass made terrific explosive sounds. A door burst open. Mud and boulders poured into the hall. We’re going to go, Jackie thought. Oh, my God, what a hell of a way for the four of us to die together.

Three rains ago we had debris flows in Montecito, the next zip code over from our home in Santa Barbara. I wrote about it in Making sense of what happened to Montecito. The flows, which destroyed much of the town and killed about two dozen people, were caused by heavy rains following the Thomas Fire, which at 281,893 acres was biggest fire in California history at the time. The Camp Fire, a few months later, burned a bit less land but killed 85 people and destroyed more than 18,000 buildings, including whole towns. This year we already have two fires bigger than the Thomas, and at least three more growing fast enough to take the lead. You can see the whole updated list on the Los Angeles Times California Wildfires Map.

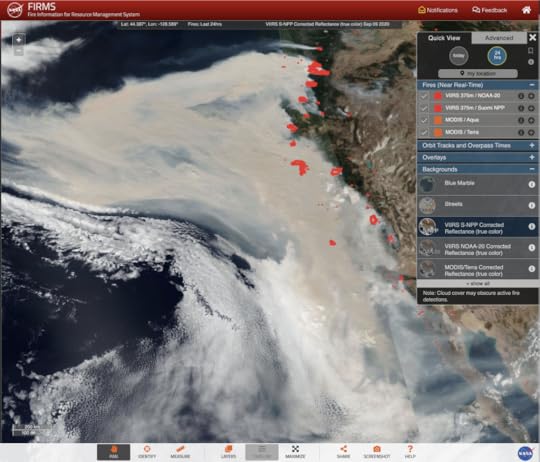

For a good high-altitude picture of what’s going on, I recommend NASA’s FIRMS (Fire Information for Resource Management System). It’s a highly interactive map that lets you mix input from satellite photographs and fire detection by orbiting MODIS and VIIRS systems. MODIS is onboard the Terra and Aqua satellites; and VIIRS is onboard the Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) spacecraft. (It’s actually more complicated than that. If you’re interested, dig into those links.) Here’s how the FIRMS map shows the active West Coast fires and the smoke they’re producing:

That’s a lot of cremated forest and wildlife right there.

I just put those two images and a bunch of others up on Flickr, here. Most are of MODIS fire detections superimposed on 3-D Google Earth maps. The main thing I want to get across with these is how large and anomalous these fires are.

True: fire is essential to many of the West’s wild ecosystems. It’s no accident that the California state tree, the Coast Redwood, grows so tall and lives so long: it’s adapted to fire. (One can also make a case that the state flower, the California Poppy, which thrives amidst fresh rocks and soil, is adapted to earthquakes.) But what’s going on here is something much bigger. Explain it any way you like, including strange luck.

Whatever you conclude, it’s a hell of a show. And vice versa.

September 8, 2020

The smell of boiling frog

I just got this email today:

Which tells me, from a sample of one (after another, after another) that Zoom is to video conferencing in 2020 what Microsoft Windows was to personal computing in 1999. Back then one business after another said they would only work with Windows and what was left of DOS: Microsoft’s two operating systems for PCs.

What saved the personal computing world from being absorbed into Microsoft was the Internet—and the Web, running on the Internet. The Internet, based on a profoundly generative protocol, supported all kinds of hardware and software at an infinitude of end points. And the Web, based on an equally generative protocol, manifested on browsers that ran on Mac and Linux computers, as well as Windows ones.

But video conferencing is different. Yes, all the popular video conferencing systems run in apps that work on multiple operating systems, and on the two main mobile device OSes as well. And yes, they are substitutable. You don’t have to use Zoom (unless, in cases like mine, where talking to my doctors requires it). There’s still Skype, Webex, Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts and the rest.

But all of them have a critical dependency through their codecs. Those are the ways they code and decode audio and video. While there are some open source codecs, all the systems I just named use proprietary (patent-based) codecs. The big winner among those is H.264, aka AVC-1, which Wikipedia says “is by far the most commonly used format for the recording, compression, and distribution of video content, used by 91% of video industry developers as of September 2019.” Also,

H.264 is perhaps best known as being the most commonly used video encoding format on Blu-ray Discs. It is also widely used by streaming Internet sources, such as videos from Netflix, Hulu, Prime Video, Vimeo, YouTube, and the iTunes Store, Web software such as the Adobe Flash Player and Microsoft Silverlight, and also various HDTV broadcasts over terrestrial (ATSC, ISDB-T, DVB-T or DVB-T2), cable (DVB-C), and satellite (DVB-S and DVB-S2) systems.

H.264 is protected by patents owned by various parties. A license covering most (but not all) patents essential to H.264 is administered by a patent pool administered by MPEG LA.[9]

The commercial use of patented H.264 technologies requires the payment of royalties to MPEG LA and other patent owners. MPEG LA has allowed the free use of H.264 technologies for streaming Internet video that is free to end users, and Cisco Systems pays royalties to MPEG LA on behalf of the users of binaries for its open source H.264 encoder.

This is generative, clearly, but not as generative as the Internet and the Web, which are both end-to-end by design. .

More importantly, AVC-1 in effect slides the Internet and the Web into the orbit of companies that have taken over what used to be telephony and television, which are now mooshed together. In the Columbia Doctors example, Zoom the new PBX. The new classroom is every teacher and kid on her or his own rectangle, “zooming” with each other through the new telephony. The new TV is Netflix, Disney, Comcast, Spectrum, Apple, Amazon and many others, all competing for wedges our Internet access and entertainment budgets.

In this new ecosystem, you are less the producer than you were, or would have been, in the early days of the Net and the Web. You are the end user, the consumer, the audience, the customer. Not the producer, the performer. Sure, you can audition for those roles, and play them on YouTube and TikTok, but those are somebody else’s walled gardens. You operate within them at their grace. You are not truly free.

And maybe none of us ever were, in those early days of the Net and the Web. But it sure seemed that way. And it does seem that we have lost something.

Or maybe just that we are losing it, in the manner of boiling frogs.

Do we have to? I mean, it’s still early.

The digital world is how old? Decades, at most.

And how long will it last? At the very least, more than that. Centuries or millennia, probably.

So there’s hope.

August 23, 2020

Bet on obsolescence

In New Digital Realities; New Oversight Solutions, Tom Wheeler, Phil Verveer and Gene Kimmelman suggest that “the problems in dealing with digital platform companies” strip the gears of antitrust and other industrial era regulatory machines, and that what we need instead is “a new approach to regulation that replaces industrial era regulation with a new more agile regulatory model better suited for the dynamism of the digital era.” For that they suggest “a new Digital Platform Agency should be created with a new, agile approach to oversight built on risk management rather than micromanagement.” They provide lots of good reasons for this, which you can read in depth here.

I’m on a list where this is being argued. One of those participating is Richard Shockey, who often cites his eponymous law, which says, “The answer is money. What is the question?” I bring that up as background for my own post on the list, which I’ll share here:

The Digital Platform Agency proposal seems to obey a law like Shockey’s that instead says, “The answer is policy. What is the question?”

I think it will help, before we apply that law, to look at modern platforms as something newer than new. Nascent. Larval. Embryonic. Primitive. Epiphenomenal.

It’s not hard to think of them that way if we take a long view on digital life.

Start with this question: is digital tech ever going away?

Whether yes or no, how long will digital tech be with us, mothering boundless inventions and necessities? Centuries? Millenia?

And how long have we had it so far? A few decades? Hell, Facebook and Twitter have only been with us since the late ’00s.

So why start to regulate what can be done with those companies from now on, right now?

I mean, what if platforms are just castles—headquarters of modern duchies and principalities?

Remember when we thought IBM, AT&T and the PTTs in Europe would own and run the world forever?

Remember when the BUNCH was around, and we called IBM “the environment?” Remember EBCDIC?

Remember when Microsoft ruled the world, and we thought they had to be broken up?

Remember when Kodak owned photography, and thought their enemy was Fuji?

Remember when recorded music had to be played by rolls of paper, lengths of tape, or on spinning discs and disks?

Remember when “social media” was a thing, and all the world’s gossip happened on Facebook and Twitter?

Then consider the possibility that all the dominant platforms of today are mortally vulnerable to obsolescence, to collapse under their own weight, or both.

Nay, the certainty.

Every now is a future then, every is a was. And trees don’t grow to the sky.

It’s an easy bet that every platform today is as sure to be succeeded as were stone tablets by paper, scribes by movable type, letterpress by offset, and all of it by xerography, ink jet, laser printing and whatever comes next.

Sure, we do need regulation. But we also need faith in the mortality of every technology that dominates the world at any moment in history, and in the march of progress and obsolescence.

Another thought: if the only answer is policy, the problem is the question.

This suggests yet another another law (really an aphorism, but whatever): “The answer is obsolescence. What is the question?”

As it happens, I wrote about Facebook’s odds for obsolescence two years ago here. An excerpt:

How easy do you think it is for Facebook to change: to respond positively to market and regulatory pressures?

Consider this possibility: it can’t.

One reason is structural. Facebook is comprised of many data centers, each the size of a Walmart or few, scattered around the world and costing many $billions to build and maintain. Those data centers maintain a vast and closed habitat where more than two billion human beings share all kinds of revealing personal shit about themselves and each other, while providing countless ways for anybody on Earth, at any budget level, to micro-target ads at highly characterized human targets, using up to millions of different combinations of targeting characteristics (including ones provided by parties outside Facebook, such as Cambridge Analytica, which have deep psychological profiles of millions of Facebook members). Hey, what could go wrong?

In three words, the whole thing.

The other reason is operational. We can see that in how Facebook has handed fixing what’s wrong with it over to thousands of human beings, all hired to do what The Wall Street Journal calls “The Worst Job in Technology: Staring at Human Depravity to Keep It Off Facebook.” Note that this is not the job of robots, AI, ML or any of the other forms of computing magic you’d like to think Facebook would be good at. Alas, even Facebook is still a long way from teaching machines to know what’s unconscionable. And can’t in the long run, because machines don’t have a conscience, much less an able one.

You know Goethe’s (or hell, Disney’s) story of The Sorceror’s Apprentice? Look it up. It’ll help. Because Mark Zuckerberg is both the the sorcerer and the apprentice in the Facebook version of the story. Worse, Zuck doesn’t have the mastery level of either one.

Nobody, not even Zuck, has enough power to control the evil spirits released by giant machines designed to violate personal privacy, produce echo chambers beyond counting, amplify tribal prejudices (including genocidal ones) and produce many $billions for itself in an advertising business that depends on all of that—while also trying to correct, while they are doing what they were designed to do, the massively complex and settled infrastructural systems that make all if it work.

I’m not saying regulators should do nothing. I am saying that gravity still works, the mighty still fall, and these are facts of nature it will help regulators to take into account.

August 17, 2020

A side view of the Ranch 2 Fire

What you see there is a cumulonimbus cloud rising to the north above Ranch 2, a wildfire about fifteen miles east of here in the San Gabriel Mountains, just north of Asuza (one of too many towns to remember, in greater Los Angeles). If the video works, you’ll see how how the clouds give shape to the heat from the fire, even as smoke (darker and with a gray/magenta color) stopping at a lower elevation, spreads northward in the same direction.

The fire was caused by arson, says the guy who confessed to starting it.

It’s interesting to see how much reporting on fires has changed in the time I’ve been following stories like this in Southern California. Inciweb, the canonical close-to-live running catalog of wildfires in the U.S. has moved from the .org where it started to NCWG.gov, the National Coordinating Wildfire Group. When I first wrote about Inciweb, back in ’06, I didn’t mention that it was entirely the heroic work of one Linux hacker at the Forest Service who didn’t wish to be identified.

Anyway, if you want to catch up on the Ranch2, one of too many wildfires clouding the western skies right now, here’s the Twitter search for the latest.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers