Doc Searls's Blog, page 41

June 27, 2020

An audio blog post

I’m trying something new here, speaking instead of writing. Here it is:

http://blogs.harvard.edu/doc/files/2020/06/2020_06_27-audioblog.mp3

[Note: this didn’t work at first on iPhones, so I changed the file type to .mp3. Should work now.]

I recorded it last night while walking twelve thousand steps, briskly, on the deck of my house.

Think of it as a kind of voice mail to readers.

The topic I cover is one I’ve written about here; but I’m not going to provide any links—at least not yet.

That’s because I want to see if what I’m trying to say comes across better in speaking than in writing. Also because I think it matters, and it’s worth the effort.

If I’m encouraged by the response, I’ll keep it up.

June 22, 2020

So far, privacy isn’t a debate

Remember the dot com boom?

Doesn’t matter if you don’t. What does matter is that it ended. All business manias do.

That’s why we can expect the “platform economy” and “surveillance capitalism” to end. Sure, it’s hard to imagine that when we’re in the midst of the mania, but the end will come.

When it does, maybe then we can have a “privacy debate.” Meanwhile, there isn’t one. In fact there can’t be one, because we don’t have privacy in the online world.

We do, however, in the offline world, and we’ve had it ever since we invented clothing, doors, locks and norms for signaling what’s okay and what’s not okay in respect to our personal spaces, possessions and information.

That we hardly have the equivalent in the networked world doesn’t mean we won’t. Or that we can’t. The Internet in its current form was only born in the mid-’90s. In the history of business and culture, that’s a blip.

Really, it’s still early.

So, the fact that websites, network services, phone companies, platforms, publishers, advertisers and governments violate our privacy with wanton disregard for it doesn’t mean we can’t ever stop them. It means we haven’t done it yet, because we don’t have the tech for it. (Sure, some wizards do, but muggles don’t. And most of us are muggles.)

And, since we don’t have privacy tech yet, we lack the simple norms that grow around technologies that give us ways signal what’s okay and what’s not okay. We’ll get those when we have the digital equivalents of buttons, zippers, doors, locks, shades and door knockers and bells.

This is what many of us have been working on at ProjectVRM, Customer Commons, the Me2B Alliance, MyData and other organizations whose mission is getting each of us the tech we need to operate at full agency when dealing with the companies and governments of the world.

I bring all this up as a “Yes, and” to a piece in Salon by Michael Corn (@MichaelAlanCorn), CISO of UCSD, titled We’re losing the war against surveillance capitalism because we let Big Tech frame the debate. Subtitle: “It’s too late to conserve our privacy — but to preserve what’s left, we must stop defining people as commodities.”

Yes, that. Also what he calls “optimism and activism.” In the latter category is code. Specifically, the digital equivalents of clothes, doors, locks, bells and knockers.

Some of those are in the works. Others are not—yet.

If you want to help, join one or more of the efforts in the links four paragraphs up. And, if you’re a developer already on the case, let us know how we can help get your solutions into each and all of our digital hands.

For guidance, this privacy manifesto should help. Thanks.

June 9, 2020

The best way to forget is to never know

@EvanSelinger tweeted, While some companies think it’s enough to tweet support for social justice while marketing a tool for oppression, IBM gets out of the facial recognition business & states opposition to mass surveillance & racial profiling. In that tweet he pointed to IBM will no longer offer, develop, or research facial recognition technology (Subhead: IBM’s CEO says we should reevaluate selling the technology to law enforcement), by @jaypeters in The Verge. Here is the letter to the U.S. Congress in which Arvind Krishna, IBM’s CEO, says his piece. The relevant passage: “IBM no longer offers general purpose IBM facial recognition or analysis software. IBM firmly opposes and will not condone uses of any technology, including facial recognition technology offered by other vendors, for mass surveillance, racial profiling, violations of basic human rights and freedoms, or any purpose which is not consistent with our values and Principles of Trust and Transparency. We believe now is the time to begin a national dialogue on whether and how facial recognition technology should be employed by domestic law enforcement agencies.”

In About face, I went on the record (while it lasts, anyway) in opposition to facial recognition in general. Specifically, The only entities that should be able to recognize people’s faces are other people. And maybe their pets. But not machines.

Privacy Badger found 46 potential trackers trying to load into my browser as I read that piece in The Verge. I’m on record opposing that kinda shit too.

June 1, 2020

Bad $20

I once tried to pass a counterfeit $20 bill. Actually, twice.

The first was when I paid for a lunch at Barney Greengrass in New York, about two years ago. After exposing the $20 to a gizmo at the cash register, the cashier handed it back to me, saying it was counterfeit. Surprised—I had no idea there were counterfeit $20s in circulation at all—I asked how he could tell. He pointed at the gizmo and explained how it worked. I said “Okay,” gave him a different $20, got my change and walked out, intending later to compare the fake 20 with a real one.

The second was when I paid for something with the bad $20 at some other establishment, not meaning to. I just forgot I still had it in my wallet.

In respect to the current meltdown in this country—one that started, reportedly, when George Floyd attempted to pay for something with a bad $20 bill, two facts ricochet around in my mind. One is that the cashier at Barney Greengrass didn’t call the cops on me. Nor was I killed. The other is that I surely got my bad $20 where everybody gets all their $20s: from a cash machine. And that there must be a lot of counterfeit $20s floating about in the world.

Beyond that I have nothing to add. What’s happening in the U.S. today says more than enough.

May 25, 2020

The GDPR’s biggest fail

If the GDPR did what it promised to do, we’d be celebrating Privmas today. Two years after the GDPR became enforceable, privacy should have become be the norm rather than the exception in the online world.

But it didn’t. And it’s not because the GDPR is poorly enforced. It’s because it’s too easy to claim compliance to the letter of GDPR law while violating its spirit.

Want to see how easy? Try searching for GDPR+compliance+consent:

https://www.google.com/search?q=gdpr+compliance+consent

Nearly all of the ~21,000,000 results you’ll get are from sources pitching ways to continue tracking people online, mostly by obtaining “consent” to privacy violations that almost nobody would welcome in the offline world.

Imagine if every shop you passed on the street sent someone outside to painlessly jab a needle into your neck, to inject a load of tracking beacons into your bloodstream. If you were to ask why they do that, they’d say it’s so their third parties can do “analytics” and show you “relevant” and “interest-based” advertising. Would you be okay with that?

Well, that’s what you’re saying when you click “Accept” or “Got it” when a typical GDPR-complying website presents a cookie notice that says something like this:

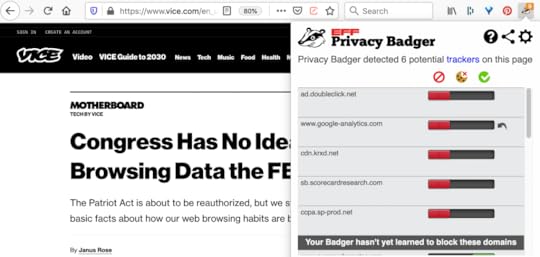

That one is from Vice, by the way. Here’s how the top story on Vice’s front page looks in Belgium (though a VPN), with Privacy Badger looking for trackers:

The number of potential trackers Privacy Badger finds here in California (without a VPN) is fourteen.

The number of potential trackers Privacy Badger finds here in California (without a VPN) is fourteen.

What are these entities up to? I do know DoubleClick follows you for advertising purposes. Google Analytics follows you too. Yes, Google says you’re anonymized somehow in both systems, but you are being followed. Worse, stalked. (Look up the verb. Top result: “to pursue or approach prey, quarry, etc., stealthily” That’s what’s going on.)

Get this: There is also no way for you to know exactly how you’re being tracked or what is done with that information, because the instrument for that—a tool on your side—isn’t available. It probably hasn’t even been invented.

And this: You have no record of having agreed to anything. No audit trail. Nothing of the kind.

Let’s go back to first principles here: It is just as wrong to track a person like a marked animal in the online world as it is in the offline one.

The GDPR was made to thwart online tracking. On the whole it has not. Instead, it has made the experience of being tracked online a worse one.

Yes, that was not the intent. And yes, the GDPR has done some good.

But if you are any less followed online today than you were when the GDPR became enforceable two years ago, it’s because you and the browser makers have worked to thwart at least some of it.

So, nothing to celebrate. Not this Privmas.

May 15, 2020

Will our digital lives leave a fossil record?

In the library of Earth’s history, there are missing books, and within books there are missing chapters, written in rock that is now gone. The greatest example of “gone” rock is what John Wesley Powell observed in 1869, on his expedition by boat through the Grand Canyon. Floating down the Colorado river, he saw the canyon’s mile-thick layers of reddish sedimentary rock resting on a basement of gray non-sedimentary rock. Observing this, he correctly assumed that the upper layers did not continue from the bottom one, because time had clearly passed between the basement rock and the floors of rock above it. He didn’t know how much time, and could hardly guess. The answer turned out to be more than a billion years. The walls of the Grand Canyon say nothing about what happened during that time. Geology calls that nothing an unconformity.

I the decades since Powell made his notes, the same gap has been found all over the world, and is now called the Great Unconformity. Because of that unconformity, geology knows close to nothing about what happened in the world through stretches of time up to 1.6 billion years long.

All of those stretches end abruptly with the Cambrian Explosion, which began about 541 million years ago, when the Cambrian period arrived, and with it an amplitude of history, written in stone.

Many theories attempt to explain what erased such a large span of Earth’s history, but the prevailing paradigm is perhaps best expressed in “Neoproterozoic glacial origin of the Great Unconformity”, published on the last day of 2018 by nine geologists writing for the National Academy of Sciences. Put simply, they blame snow. Lots of it: enough to turn the planet into one giant snowball, informally called Snowball Earth. A more accurate name for this time would be Glacierball Earth, because glaciers, all formed from accumulated snow, apparently covered most or all of Earth’s land during the Great Unconformity—and most or all of the seas as well.

The relevant fact about glaciers is that they don’t sit still. They push immensities of accumulated ice down on landscapes and then spread sideways, pulverizing and scraping against adjacent landscapes, abrading their ways through mountains and across hills and plains like a trowel through wet cement. In this manner, glaciers scraped a vastness of geological history off the Earth’s continents and sideways into ocean basins, so plate tectonics could hide the evidence. (A fact little known outside geology is that nearly all the world’s ocean floors are young: born in spreading centers and killed by subduction under continents or piled as debris on continental edges here and there.) As a result, the stories of Earth’s missing history are partly told by younger rock that remembers only that a layer of moving ice had erased pretty much everything other than a signature on its work.

I bring all this up because I see something analogous to Glacierball Earth happening right now, right here, across our new worldwide digital sphere. A snowstorm of bits is falling on the virtual surface of our virtual sphere, which itself is made of bits even more provisional and temporary than the glaciers that once covered the physical Earth. Nearly all of this digital storm, vivid and present at every moment, is doomed to vanish, because it lacks even a glacier’s talent for accumulation.

There is nothing about a bit that lends itself to persistence, other than the media it is written on, if it is written at all. Form follows function, and right now, most digital functions, even those we call “storage”, are temporary. The largest commercial facilities for storing digital goods are what we fittingly call “clouds”. By design, these are built to remember no more of what they once contained than does an empty closet. Stop paying for cloud storage, and away goes your stuff, leaving no fossil imprints. Old hard drives, CDs and DVDs might persist in landfills, but people in the far future may look at a CD or a DVD the way a geologist today looks at Cambrian zircons: as hints of digital activities may have happened during an interval about which otherwise nothing is known. If those fossils speak of what’s happening now at all, it will be of a self-erasing Digital Earth that began in the late 20th century.

This isn’t my theory. It comes from my wife, who has long claimed that future historians will look on our digital age as an invisible one, because it sucks so royally at archiving itself.

Credit where due: the Internet Archive is doing its best to make sure that some stuff will survive. But what will keep that archive alive, when all the media we have for recalling bits—from spinning platters to solid state memory—are volatile by nature?

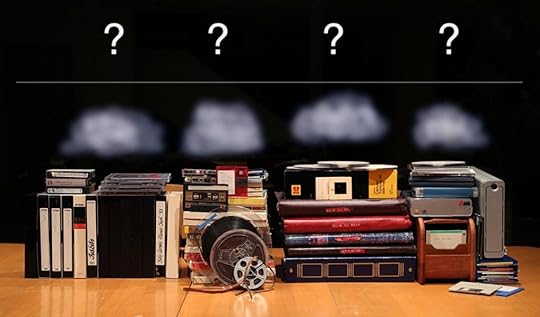

My own future unconformity is announced by the stack of books on my desk, propping up the laptop on which I am writing. Two of those books are self-published compilations of essays I wrote about technology in the mid-1980s, mostly for publications that are long gone. The originals are on floppy disks that can be read only by PCs and apps of that time, some of which are buried in lower strata of boxes in my garage. I just found a floppy with some of those essays. (It’s the one with a blue edge in the wood case near the right end of the photo above.) If those still retain readable files, I am sure there are ways to recover at least the raw ASCII text. But I’m still betting the paper copies of the books under this laptop will live a lot longer than will the floppies or my mothalled PCs, all of which are likely bricked by decades of un-use.

As for other media, the prospect isn’t any better.

At the base of my video collection is a stratum of VHS videotapes, atop of which are strata of Video8 and Hi8 tapes, and then one of digital stuff burned onto CDs and stored in hard drives, most of which have been disconnected for years. Some of those drives have interfaces and connections no longer supported by any computers being made today. Although I’ve saved machines to play all of them, none I’ve checked still work. One choked to death on a CD I stuck in it. That was a failure that stopped me from making Christmas presents of family memories recorded on old tapes and DVDs. I meant to renew the project sometime before the following Christmas, but that didn’t happen. Next Christmas? Maybe.

Then there are my parents’ 8mm and 16mm movies filmed between the 1930s and the 1960s. In 1989, my sister and I had all of those copied over to VHS tape. We then recorded my mother annotating the tapes onto companion cassette tapes while we all watched the show. I still have the original film in a box somewhere, but I haven’t found any of the tapes. Mom died in 2003 at age 90, so her whole generation is now gone.

The base stratum of my audio past is a few dozen open reel tapes recorded in the 1950s and 1960s. Above those are cassette and micro-cassete tapes, plus many Sony MiniDisks recorded in ATRAC, a proprietary compression algorithm now used by nobody, including Sony. Although I do have ways to play some (but not all) of those, I’m cautious about converting any of them to digital formats (Ogg, MPEG or whatever), because all digital storage media are likely to become obsolete, dead, or both—as will formats, algorithms and codecs. Already I have dozens of dead external hard drives in boxes and drawers. And, since no commercial cloud service is committed to digital preservation in perpetuity in the absence of payment, my files saved in clouds are sure to be flushed after neither my heirs nor I continue paying for their preservation.

Same goes for my photographs. My old photographs are stored in boxes and albums of photos, negatives and Kodak slide carousels. My digital photographs are spread across a mess of duplicated back-up drives totaling many terabytes, plus a handful of CDs. About 60,000 photos are exposed to the world on Flickr’s cloud, where I maintain two Pro accounts (here and here) for $50/year a piece. More are in the Berkman Klein Center’s pro account (here) and Linux Journal‘s (here). It is unclear currently whether any of that will survive after any of those entities stop paying the yearly fee. SmugMug, which now owns Flickr, has said some encouraging things about photos such as mine, all of which are Creative Commons-licensed to encourage re-use. But, as Geoffrey West tells us, companies are mortal. All of them die.

As for my digital works as a whole (or anybody’s), there is great promise in what the Internet Archive and Wikimedia Commons do, but there is no guarantee that either will last for decades more, much less for centuries or millennia. And neither are able to archive everything that matters (much as they might like to).

It should also be sobering to recognize that nobody owns a domain on the internet. All those “sites” with “domains” at “locations” and “addresses” are rented. We pay a sum to a registrar for the right to use a domain name for a finite period of time. There are no permanent domain names or IP addresses. In the digital world, finitude rules.

So the historic progression I see, and try to illustrate in the photo at the beginning of this post, is from hard physical records through digital ones we hold for ourselves, and then up into clouds that go away. Everything digital is snow falling and disappearing on the waters of time.

Will there ever be a way to save for the very long term what we ironically call our digital “assets” for more than a few dozen years? Or is all of it doomed by its own nature to disappear, leaving little more evidence of its passage than a Digital Unconformity, when everything was forgotten?

I can’t think of any technical questions more serious than those two.

The original version of this post appeared in the March 2019 issue of Linux Journal.

May 9, 2020

Choose One

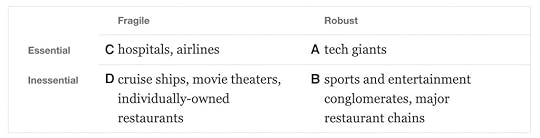

A few days ago, in Figuring the Future, I sourced an Arnold Kling blog post that posed an interesting pair of angles toward outlook: a 2×2 with Fragile Robust on one axis and Essential Inessential on the other. In his sort, essential + fragile are hospitals and airlines. Inessential + fragile are cruise ships and movie theaters. Robust + essential are tech giants. Inessential + robust are sports and entertainment conglomerates, plus major restaurant chains. It’s a heuristic, and all of it is arguable (especially given the gray along both axes), which is the idea. Cases must be made if planning is to have meaning.

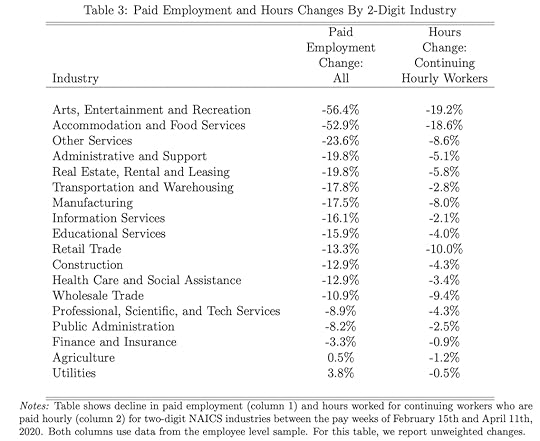

Now, haul Arnold’s template over to The U.S. Labor Market During the Beginning of the Pandemic Recession, by Tomaz Cajner, Leland D. Crane, Ryan A. Decker, John Grigsby, Adrian Hamins-Puertolas, Erik Hurst, Christopher Kurz, and Ahu Yildirmaz, of the University of Chicago, and lay it on this item from page 21:

The highest employment drop, in Arts, Entertainment and Recreation, leans toward inessential + fragile. The second, in Accommodation and Food Services is more on the essential + fragile side. The lowest employment changes, from Construction on down to Utilities, all tending toward essential + robust.

So I’m looking at those bottom eight essential + robust categories and asking a couple of questions:

1) What percentage of workers in each essential + robust category are now working from home?

2) How much of this work is essentially electronic? Meaning, done by people who live and work through glowing rectangles, connected on the Internet?

Hard to say, but the answers will have everything to do with the transition of work, and life in general, into a digital world that coexists with the physical one. This was the world we were gradually putting together when urgency around COVID-19 turned “eventually” into “now.”

In Junana, Bruce Caron writes,

“Choose One” was extremely powerful. It provided a seed for everything from language (connecting sound to meaning) to traffic control (driving on only one side of the road). It also opened up to a constructivist view of society, suggesting that choice was implicit in many areas, including gender.

Choose One said to the universe, “There are several ways we can go, but we’re all going to agree on this way for now, with the understanding that we can do it some other way later, thank you.” It wasn’t quite as elegant as “42,” but it was close. Once you started unfolding with it, you could never escape the arbitrariness of that first choice.

In some countries, an arbitrary first choice to eliminate or suspend personal privacy allowed intimate degrees of contract tracing to help hammer flat the infection curve of COVID-19. Not arbitrary, perhaps, but no longer escapable.

Other countries face similar choices. Here in the U.S., there is an argument that says “The tech giants already know our movements and social connections intimately. Combine that with what governments know and we can do contact tracing to a fine degree. What matters privacy if in reality we’ve lost it already and many thousands or millions of lives are at stake—and so are the economies that provide what we call our ‘livings.’ This virus doesn’t care about privacy, and for now neither should we.” There is also an argument that says, “Just because we have no privacy yet in the digital world is no reason not to have it. So, if we do contact tracing through our personal electronics, it should be disabled afterwards and obey old or new regulations respecting personal privacy.”

Those choices are not binary, of course. Nor are they outside the scope of too many other choices to name here. But many of those are “Choose Ones” that will play out, even if our choice is avoidance.

May 8, 2020

Reality 2020.05.08

In The Web and the New Reality, which I posted on December 1, 1995 (and again a few days ago), I called that date “Reality 1.995.12,” and made twelve predictions. In this post I’ll visit how those have played out over the quarter century since then.

1. As more customers come into direct contact with suppliers, markets for suppliers will change from target populations to conversations.

Well, both. While there are many more direct conversations between demand and supply than there were in the pre-Internet world, we are more targeted than ever, now personally and not just as populations. This has turned into a gigantic problem that many of us have been talking about for a decade or more, to sadly insufficient effect.

2. Travel, ticket, advertising and PR agencies will all find new ways to add value, or they will be subtracted from market relationships that no longer require them.

I don’t recall why I grouped those four things, so let’s break them apart:

Little travel agencies went to hell. Giant Net-based ones thrived. See here.

Tickets are now almost all digital. I don’t know what a modern ticket agency does, if if any exist.

Advertising agencies went digital and became malignant. I’ve written about that a lot, here. All of those writings could be compressed to a pull quote from Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff: “Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself.”

PR agencies, far as I know (and I haven’t looked very far) are about the same.

3. Within companies, marketing communications will change from peripheral activities to core competencies.New media will flourish on the Web, and old media will learn to live with the Web and take advantage of it.

If we count the ascendance of the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) as a success, this was a bulls-eye. However, most CMOs are all about “digital,” by which they generally mean direct response marketing. And if you didn’t skip to this item you know what I think about that.

4. Retail space will complement cyber space. Customer and technical service will change dramatically, as 800 numbers yield to URLs and hard copy documents yield to soft copy versions of the same thing… but in browsable, searchable forms.

Yep. All that happened.

5. Shipping services of all kinds will bloom. So will fulfillment services. So will ticket and entertainment sales services.

That too.

The web’s search engines will become the new yellow pages for the whole world. Your fingers will still do the walking, but they won’t get stained with ink. Same goes for the white pages. Also the blue ones.

And that.

6. The scope of the first person plural will enlarge to include the whole world. “We” may mean everybody on the globe, or any coherent group that inhabits it, regardless of location. Each of us will swing from group to group like monkeys through trees.

Oh yeah.

7. National borders will change from barricades and toll booths into speed bumps and welcome mats.

Mixed success. When I wrote this, nearly all Internet access was through telcos, so getting online away from home still required a local phone number. That’s pretty much gone. But the Internet itself is being broken into pieces. See here

8. The game will be over for what teacher John Taylor Gatto labels “the narcotic we call television.” Also for the industrial relic of compulsory education. Both will be as dead as the mainframe business. In other words: still trucking, but not as the anchoring norms they used to be.

That hasn’t happened; but self-education, home-schooling and online study of all kinds are thriving.

9. Big Business will become as anachronistic as Big Government, because institutional mass will lose leverage without losing inertia.

Well, this happened. So, no.

10. Domination will fail where partnering succeeds, simply because partners with positive sums will combine to outproduce winners and losers with zero sums.

Here’s what I meant by that.

I think more has happened than hasn’t. But, visiting the particulars requires a whole ‘nuther post.

11. Right will make might.

Nope. And this one might never happen. Hey, in 25 years one tends to become wiser.

12. And might will be mighty different.

That’s true, and in some ways that depresses me.

So, on the whole, not bad.

May 6, 2020

Figuring the future

During our drive to Baltimore on March 7 (to visit the grandkids one last time before the lockdown came—and we knew it would), we talked, inconclusively, about the likely cascading effects that would come if large parts of the economy shut down. For example, if people weren’t going to theaters and sporting events, or traveling much at all, what would that do to the businesses involved, especially if one looked at all the dependencies between different kinds of businesses? Like, how would restaurants and office businesses not paying rent affect building owners, and the banks to which those businesses owe money?

Now that the shut-down (partial in some categories and places, complete in others) has been here for almost two months, we’re still not hearing much about where this all goes for various economic sectors. Sure, there’s plenty about what experts, politicians and various talking heads say. Also lots of human interest stories, especially of the tragic kind. And lots on bouncing stock prices and all that. But not much on what cascades back through supply chains: effects of effects of effects.

Toward help with that, there’s The economic outlook, on Arnold Kling’s blog (one of the most thoughtful and challenging about this kind of thing). On it is a 2×2 that looks like this:

I added the letters. They mean this:

A — Robust/Essential

B — Robust/Inessential

C — Fragile/Essential

D — Fragile/Inessential

Then I went down a longer list of business categories, assigning each to one of those four (respecting that some are in gray areas along both axes).

Note that this is a heuristic, meant to stimulate thought rather than to pose arguments. Anyway, here goes. More below:

accounting – A

agriculture: small and family farms and ranches – C

agriculture: industrial farms and ranches, logging – A

airlines – C

alcohol – B

automotive – C

banks and finance – A

churches – B

construction: residential – C

construction: commercial – C

cooperatives – A

public education: K-12 schools – A

public education: colleges and universities – C

private education: K-12 schools – D

private education: colleges and universities – D

offline education: A

home/self schooling, all levels – B

engineering: heavy – A

engineering: light – A

performing artists – D

sports events – B

arts – D

museums – D

gambling – B

oil and gas – A

mining and quarrying – A

firearms – B

freight forwarding (shipping, trucking, transport) – A

government – A

hospitals – C

insurance – A

legal – A

manufacturing – A

marketing and advertising – D

books – B

periodicals – C

free over-the-air commercial radio – D

free over-the-air commercial TV – D

free over-the-air non-commercial radio – B

free over-the-air non-commercial TV – D

subscription radio (including podcasting) – B

subscription (non-premium) cable TV – C

subscription- B

medical – A

nonprofits – B

public transit – A

real estate: residential – C

real estate: commercial – C

real estate: industrial – A

restaurants: chains – B

restaurants: non (or small)-chain – D

small businesses – D

retail: big chains – B

retail: small chains – D

Other: administrative support, agents and agencies, scientific and technical services, outsourced management, professional & specialized services, wholesale everything, rental of many kinds.

What I’m looking for here is a way (better than this) for looking at effects that cascade from any of these to any number of others.

Thoughts?

April 22, 2020

The Web and the New Reality

I posted this essay in my own pre-blog, Reality 2.0, on December 1, 1995. I think maybe now, in this long moment after we’ve hit a pause button on our future, we can start working on making good the unfulfilled promises that first gleamed in our future a quarter century ago.

Contents

Reality 2.0

Polyopoly

An economy of abundance

The Age of Enlightenment

Time to subtract the garbage

So what’s left

Web of the free, home of the Huns

A market is a conversation

How it all adds up

The Plus Paradigm

Reality 2.0

The import of the Internet is so obvious and extreme that it actually defies valuation: witness the stock market, which values Netscape so far above that company’s real assets and earnings that its P/E ratio verges on the infinite.

Whatever we’re driving toward, it is very different from anchoring certainties that have grounded us for generations, if not for the duration of our species. It seems we are on the cusp of a new and radically different reality. Let’s call it Reality 2.0.

The label has a millenial quality, and a technical one as well. If Reality 2.0 is Reality 2.000, this month we’re in Reality 1.995.12.

With only a few revisions left before Reality 2.0 arrives, we’re in a good position to start seeing what awaits. Here are just a few of the things this writer is starting to see…

As more customers come into direct contact with suppliers, markets for suppliers will change from target populations to conversations.

Travel, ticket, advertising and PR agencies will all find new ways to add value, or they will be subtracted from market relationships that no longer require them.

Within companies, marketing communications will change from peripheral activities to core competencies.New media will flourish on the Web, and old media will learn to live with the Web and take advantage of it.

Retail space will complement cyber space. Customer and technical service will change dramatically, as 800 numbers yield to URLs and hard copy documents yield to soft copy versions of the same thing… but in browsable, searchable forms.

Shipping services of all kinds will bloom. So will fulfillment services. So will ticket and entertainment sales services.

The web’s search engines will become the new yellow pages for the whole world. Your fingers will still do the walking, but they won’t get stained with ink. Same goes for the white pages. Also the blue ones.

The scope of the first person plural will enlarge to include the whole world. “We” may mean everybody on the globe, or any coherent group that inhabits it, regardless of location. Each of us will swing from group to group like monkeys through trees.

National borders will change from barricades and toll booths into speed bumps and welcome mats.

The game will be over for what teacher John Taylor Gatto labels “the narcotic we call television.” Also for the industrial relic of compulsory education. Both will be as dead as the mainframe business. In other words: still trucking, but not as the anchoring norms they used to be.

Big Business will become as anachronistic as Big Government, because institutional mass will lose leverage without losing inertia.Domination will fail where partnering succeeds, simply because partners with positive sums will combine to outproduce winners and losers with zero sums.

Right will make might.

And might will be mighty different.

Polyopoly

The Web is the board for a new game Phil Salin called “Polyopoly.” As Phil described it, Polyopoly is the opposite of Monopoly. The idea is not to win a fight over scarce real estate, but to create a farmer’s market for the boundless fruits of the human mind.

It’s too bad Phil didn’t live to see the web become what he (before anyone, I believe) hoped to create with AMIX: “the first efficient marketplace for information.” The result of such a marketplace, Phil said, would be polyopoly.

In Monopoly, what mattered were the three Ls of real estate: “location, location and location.”

On the web, location means almost squat.

What matters on the web are the three Cs: content, connections and convenience. These are what make your home page a door the world beats a path to when it looks for the better mouse trap that only you sell. They give your webfront estate its real value.

If commercial interests have their way with the Web, we can also add a fourth C: cost. But how high can costs go in a polyopolistic economy? Not very. Because polyopoly creates…

An economy of abundance

The goods of Polyopoly and Monopoly are as different as love and lug nuts. Information is made by minds, not factories; and it tends to make itself abundant, not scarce. Moreover, scarce information tends to be worthless information.

Information may be bankable, but traditional banking, which secures and contains scarce commodities (or their numerical representations) does not respect the nature of information.

Because information abhors scarcity. It loves to reproduce, to travel, to multiply. Its natural habitats are wires and airwaves and disks and CDs and forums and books and magazines and web pages and hot links and chats over cappuccinos at Starbucks. This nature lends itself to polyopoly.

Polyopoly’s rules are hard to figure because the economy we are building with it is still new, and our vocabulary for describing it is sparse.

This is why we march into the Information Age hobbled by industrial metaphors. The “information highway” is one example. Here we use the language of freight forwarding to describe the movement of music, love, gossip, jokes, ideas and other communicable forms of knowledge that grow and change as they move from mind to mind.

We can at least say that knowledge, even in its communicable forms, is not reducible to data. Nor is the stuff we call “intellectual property.” A song and a bank account do not propagate the same ways. But we are inclined to say they do (and should), because we describe both with the same industrial terms.

All of which is why there is no more important work in this new economy than coining the new terms we use to describe it.

The Age of Enlightenment finally arrives

The best place to start looking for help is at the dawn of the Industrial Age. Because this was when the Age of Reason began. Nobody knew more about the polyopoly game — or played it — better than those champions of reason from whose thinking our modern republics are derived: Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin.

As Jon Katz says in “The Age of Paine” (Wired, May 1995 ), Thomas Paine was the the “moral father of the Internet.” Paine said “my country is the world,” and sought as little compensation as possible for his work, because he wanted it to be inexpensive and widely read. Paine’s thinking still shapes the politics of the U.S., England and France, all of which he called home.

Thomas Jefferson wrote the first rule of Polyopoly: “He who receives an idea from me receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.”

Thomas Jefferson wrote the first rule of Polyopoly: “He who receives an idea from me receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.”

He also left a live bomb for modern intellectual property law: “Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.” The best look at the burning fuse is John Perry Barlow’s excellent essay “The Economy of Ideas,” in the March 1994 issue of Wired. (I see that Jon Katz repeats it in his paean to Paine. Hey, if someone puts it to song, who gets the rights?)

If Paine was the moral father of the Internet, Ben Franklin’s paternity is apparent in Silicon Valley. Today he’d fit right in, inventing hot products, surfing the Web and spreading his wit and wisdom like a Johnny Cyberseed. Hell, he even has the right haircut.

Franklin left school at 10 and was barely 15 when he ran his brother’s newspaper, writing most of its content and getting quoted all over Boston. He was a self-taught scientist and inventor while still working as a writer and publisher. He also found time to discover electricity, create the world’s first postal service, invent a heap of handy products and serve as a politician and diplomat.

Franklin’s biggest obsession was time. He scheduled and planned constantly. He even wrote his famous epitaph when he was 22, six decades before he died. “The work shall not be lost,” it reads, “for it will (as he believed) appear once more in a new and more elegant edition, revised and edited by the author.”

One feels the ghost of Franklin today, editing the web.

Time to subtract the garbage

Combine Jefferson and Franklin and you get the two magnetic poles that tug at every polyopoly player: information that only gets more abundant, and time that only gets more scarce.

As Alain Couder of Groupe Bull puts it, “we treat time as a constant in all these formulas — revolutions per minute, instructions per second — yet we experience time as something that constantly decreases.”

After all, we’re born with an unknown sum of time, and we need to spend it all before we die. The notion of “saving” it is absurd. Time can only be spent.

So: to play Polyopoly well, we need to waste as little time as possible. This is not easy in a world where the sum of information verges on the infinite.

Which is why I think Esther Dyson might be our best polyopoly player.

“There’s too much noise out there anyway,” she says in ‘Esther Dyson on DaveNet‘ (12/1/94). “The new wave is not value added, it’s garbage-subtracted.”

Here’s a measure of how much garbage she subtracts from her own life: her apartment doesn’t even have a phone.

Can she play this game, or what?

So what’s left?

I wouldn’t bother to ask Esther if she watches television, or listens to the radio. I wouldn’t ask my wife, either. To her, television is exactly what Fred Allen called it forty years ago: “chewing gum for the eyes.” Ours heats up only for natural disasters and San Jose Sharks games.

Dean Landsman, a sharp media observer from the broadcast industry, tells me that John Gresham books are cutting into time that readers would otherwise spend watching television. And that’s just the beginning of a tide that will swell as every medium’s clients weigh more carefully what they do with their time.

Which is why it won’t be long before those clients wad up their television time and stick it under their computer. “Media will eat media,” Dean says.

The computer is looking a lot hungrier than the rest of the devices out there. Next to connected computing, television is AM radio.

Fasten your seat belts.

Web of the free, home of the Huns

Think of the Industrial world — the world of Big Business and Big Government — as a modern Roman Empire.

Now think of Bill Gates as Attilla the Hun.

Because that’s exactly how Bill looks to the Romans who still see the web, and everything else in the world, as a monopoly board. No wonder Bill doesn’t have a senator in his pocket (as Mark Stahlman told us in ‘Off to the Slaughter House,’ (DaveNet, 3/14/94).

Sadly for the the Romans, their empire is inhabited almost entirely by Huns, all working away on their PCs. Most of those Huns don’t have a problem with Bill. After all, Bill does a fine job of empowering his people, and they keep electing him with their checkbooks, credit cards and purchase orders.

Which is why, when they go forth to tame the web, these tough-talking Captains of Industry and Leaders of Government look like animated mannequins in Armani Suits: clothes with no emperor. Their content is emulation. They drone about serving customers and building architectures and setting standards and being open and competing on level playing fields. But their game is still control, no matter what else they call it.

Bill may be our emperor, but ruling Huns is not the same as ruling Romans. You have to be naked as a fetus and nearly as innocent. Because polyopoly does not reward the dark tricks that used to work for industry, government and organized crime. Those tricks worked in a world where darkness had leverage, where you could fool some of the people some of the time, and that was enough.

But polyopoly is a positive-sum game. Its goods are not produced by huge industries that control the world, but by smart industries that enable the world’s inhabitants. Like the PC business that thrives on it, information grows up from individuals, not down from institutions. Its economy thrives on abundance rather than scarcity. Success goes to enablers, not controllers. And you don’t enable people by fooling them. Or by manipulating them. Or by muscling them.

In fact, you don’t even play to win. As Craig Burton of The Burton Group puts it, “the goal isn’t win/win, it’s play/play.”

This is why Bill does not “control” his Huns the way IBM controlled its Romans. Microsoft plays by winning support, where IBM won by dominating the play. Just because Microsoft now holds a controlling position does not mean that a controlling mentality got them there. What I’ve seen from IBM and Apple looks far more Monopoly-minded and controlling than anything I’ve seen from Microsoft.

Does this mean that Bill’s manners aren’t a bit Roman at times? No. Just that the support Microsoft enjoys is a lot more voluntary on the part of its customers, users and partners. It also means that Microsoft has succeeded by playing Polyopoly extremely well. When it tries to play Monopoly instead, the Huns don’t like it. Bill doesn’t need the Feds to tell him when that happens. The Huns tell him soon enough.

A market is a conversation

No matter how Roman Bill’s fantasies might become, he knows his position is hardly more substantial than a conversation. In fact, it IS a conversation.

I would bet that Microsoft is engaged in more conversations, more of the time, with more customers and partners, than any other company in the world. Like or hate their work, the company connects. I submit that this, as much as anything else, accounts for its success.

In the Industrial Age, a market was a target population. Goods rolled down a “value chain” that worked like a conveyor belt. Raw materials rolled into one end and finished products rolled out the other. Customers bought the product or didn’t, and customer feedback was limited mostly to the money it spent.

To encourage customer spending, “messages” were “targeted” at populations, through advertising, PR and other activities. The main purpose of these one-way communications was to stimulate sales. That model is obsolete. What works best to day is what Normann & Ramirez (Harvard Business Review, June/July 1993) call a “value constellation” of relationships that include customers, partners, suppliers, resellers, consultants, contractors and all kinds of people.

The Web is the star field within which constellations of companies, products and markets gather themselves. And what binds them together, in each case, are conversations.

How it all adds up

What we’re creating here is a new economy — an information economy.

Behind the marble columns of big business and big government, this new economy stands in the lobby like a big black slab. The primates who work behind those columns don’t know what this thing is, but they do know it’s important and good to own. The problem is, they can’t own it. Nobody can. Because it defies the core value in all economies based on physical goods: scarcity.

Scarcity ruled the stone hearts and metal souls of every zero-sum value system that ever worked — usually by producing equal quantities of gold and gore. And for dozens of millennia, we suffered with it. If Tribe A crushed Tribe B, it was too bad for Tribe B. Victors got the spoils.

This win/lose model has been in decline for some time. Victors who used to get spoils now just get responsibilities. Cooperation and partnership are now more productive than competition and domination. Why bomb your enemy when you can get him on the phone and do business with him? Why take sides when the members of “us” and “them” constantly change?

The hard evidence is starting to come in. A recent Wharton Impact report said, “Firms which specified their objectives as ‘beating our competitors’ or ‘gaining market share’ earned substantially lower profits over the period.” We’re reading stories about women-owned businesses doing better, on the whole, because women are better at communicating and less inclined to waste energy by playing sports and war games in their marketplaces.

From the customer’s perspective, what we call “competition” is really a form of cooperation that produces abundant choices. Markets are created by addition and multiplication, not just by subtraction and division.

In my old Mac IIci, I can see chips and components from at least 11 different companies and 8 different countries. Is this evidence of war among Apple’s suppliers? Do component vendors succeed by killing each other and limiting choices for their customers? Did Apple’s engineers say, “Gee, let’s help Hitachi kill Philips on this one?” Were they cheering for one “side” or another? The answer should be obvious.

But it isn’t, for two reasons. One is that the “Dominator Model,” as anthropologist (and holocaust survivor) Riane Eisler calls it, has been around for 20,000 years, and until recently has reliably produced spoils for victors. The other is that conflict always makes great copy. To see how seductive conflict-based thinking is, try to find a hot business story that isn’t filled with sports and war metaphors. It isn’t easy.

Bound by the language of conflict, most of us still believe that free enterprise runs on competition between “sides” driven by urges to dominate, and that the interests of those “sides” are naturally opposed.

To get to the truth here, just ask this: which has produced more — the U.S. vs. Japan, or the U.S. + Japan? One produced World War II and a lot of bad news. The other produced countless marvels — from cars to consumer electronics — on which the whole world depends.

Now ask this: which has produced more — Apple vs. Microsoft or Apple + Microsoft? One profited nobody but the lawyers, and the other gave us personal computing as we know it today.

The Plus Paradigm

What brings us to Reality 2.0 is the Plus Paradigm.

The Plus Paradigm says that our world is a positive construction, and that the best games produce positive sums for everybody. It recognizes the power of information and the value of abundance. (Think about it: the best information may have the highest power to abound, and its value may vary as the inverse of its scarcity.)

Over the last several years, mostly through discussions with client companies that are struggling with changes that invalidate long-held assumptions, I have built table of old (Reality 1.0) vs. new (Reality 2.0) paradigms. The difference between these two realities, one client remarked, is that the paradigm on the right is starting to work better than the paradigm on the left.

Paradigm

Reality 1.0

Reality 2.0

Means to ends

Domination

Partnership

Cause of progress

Competition

Collaboration

Center of interest

Personal

Social

Concept of systems

Closed

Open

Dynamic

Win/Lose

Play/Play

Roles

Victor/Victim

Partner/Ally

Primary goods

Capital

Information

Source of leverage

Monopoly

Polyopoly

Organization

Hierarchy

Flexiarchy

Roles

Victor/Victim

Server/Client

Scope of self-interest

Self/Nation

Self/World

Source of power

Might

Right

Source of value

Scarcity

Abundance

Stage of growth

Child (selfish)

Adult (social)

Reference valuables

Metal, Money

Life, Time

Purpose of boundaries

Protection

Limitation

Changes across the paradigms show up as positive “reality shifts.” The shift is from OR logic to AND logic, from Vs. to +:

Reality 1.0

Reality 2.0

man vs nature

man + nature

Labor vs management

Labor + management

Public vs private

Public + private

Men vs women

Men + women

Us vs them

Us + them

Majority vs minority

Majority + minority

Party vs party

Party + party

Urban vs rural

Urban + rural

Black vs white

Black + white

Business vs govt.

Business + govt.

The Plus Paradigm comprehends the world as a positive construction, and sees that the best games produce positive sums for everybody. It recognizes the power of information and the value of abundance. (Think about it: the best information may have the highest power to abound, and its value may vary as the inverse of its scarcity.)

For more about this whole way of thinking, see Bernie DeKoven’s ideas about “the ME/WE” at his “virtual playground.”]

This may sound sappy, but information works like love: when you give it away, you still get to keep it. And when you give it back, it grows.

Which has always been the case. But in Reality 2.0, it should become a lot more obvious.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers