A Better Way to Do News

Twelfth in the News Commons series

Last week at DWeb Camp, I gave a talk titled The Future, Present, and Past of News—and Why Archives Anchor It All. Here’s a frame from a phone video:

[image error]

DWeb Camp is a wonderful gathering, hosted by the Internet Archive at Camp Navarro in Northern California. The talk was at 9:30am, when it was still just 59°. It hit the 90s later.

In this post I’ll give the same talk, adding some slides and points I didn’t get to my 25-minute window. Here goes.

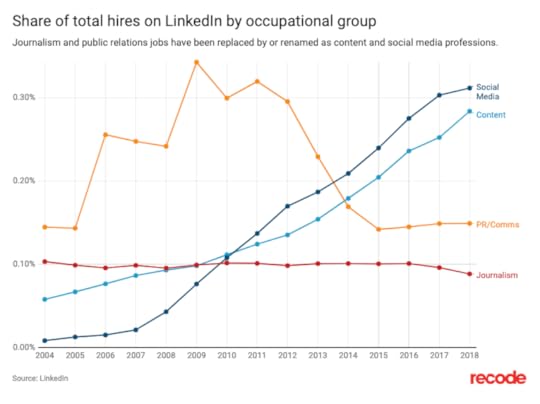

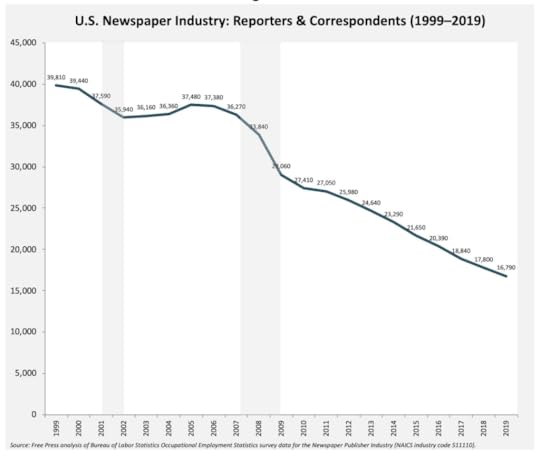

For journalism, news is bad:

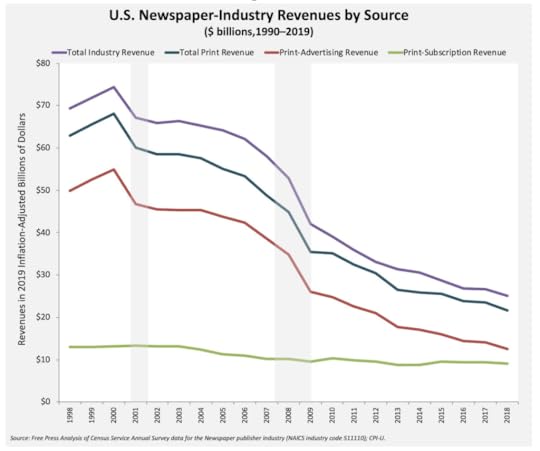

Revenue sources are going away:

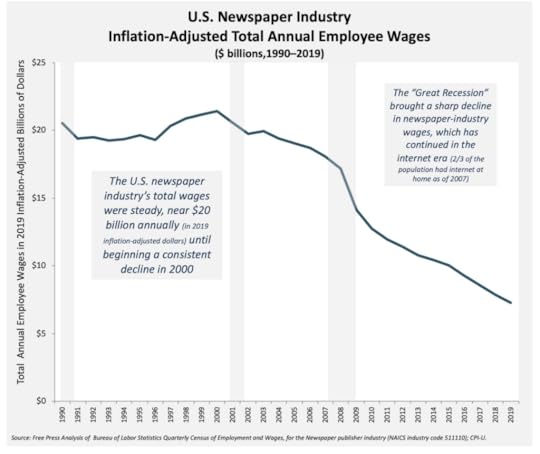

Wages suck:

So does employment:

But it’s looking up for bullshit and filler:

So what can we do?

There’s the easy choice—

But bear in mind that,

News only sucks as a big business.

But not as a small one.

For example, here:

Bloomington, Indiana. That’s where my wife and I are living while we serve as visiting scholars with the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University. It’s a great place. (I’ve lived in many college towns, and this is my favorite, for many reasons.)

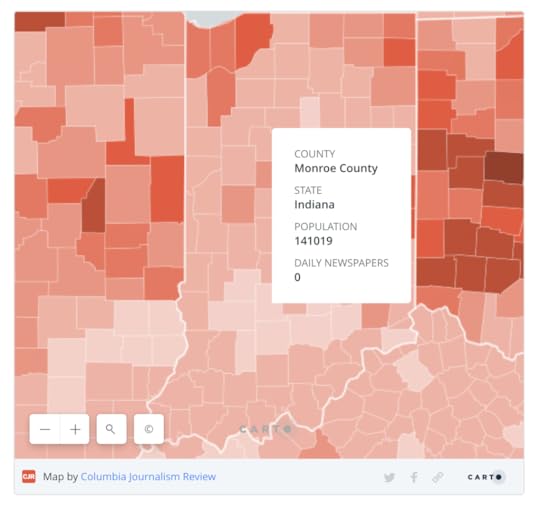

In 2017, Columbia Journalism Review produced an interactive map of America’s “news deserts.” One of them is Monroe County, most of which is Bloomington:

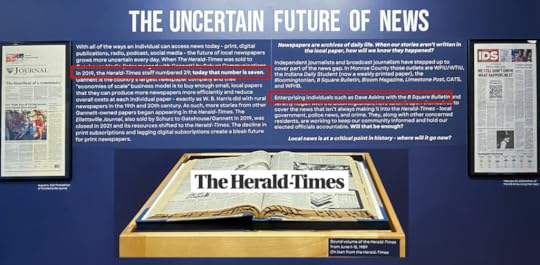

This was in error, because Bloomington did still have a daily paper then: the Herald-Times. And it is still does. The H-T persists in print and online. But, as “Breaking the News: The Past and Uncertain Future of Local Print Journalism” explained last year in a huge and well-curated exhibit at the Monroe County History Center,

the Herald-Times has shrunk quite a bit, while some “enterprising individuals” are taking up the slack—and then some. One they single out is Dave Askins of the B Square Bulletin:

Dave’s beat is city and county government. His “almost daily” newsletter and website are free, but they are also his business, and he makes his living off of voluntary support from his readers. More importantly, Dave has some original, simple, and far-reaching ideas about how local news should work. That’s what I’m here to talk about.

We’ll start with the base format of human interest, and therefore also of journalism: stories.

Right now, as you read this, journalists are being asked the same three words, either by themselves or by their editors:

I was 23 when I got my first job at a newspaper, and quickly learned that there are just three elements to every story:

CharacterProblemMovementThat’s it.

The character can be a person, a ball club, a political party, whoever or whatever. They can be good or bad, few or many. It doesn’t matter, so long as they are interesting.

The problem can involve struggle, conflict, or any challenge—or collection of them—that holds your interest. This is what gets and keeps readers, viewers, and listeners engaged.

The movement needs to be toward resolution, even if it never gets there. (Soap operas never do, but the movement is always there.)

Lose any one of those three and you don’t have a story.

So let’s start with Character. Do you know who this is?

Probably not. (Nobody in the audience at my talk recognized him.)

He’s Pol Pot, who gets bronze medal for genocide, given the number of people he had killed (at 1.5 to 2 million, he comes in behind Hitler and Stalin) and a gold medal for killing the largest percentage of his own country’s population (a quarter or so).* His country was Cambodia, which he and the Khmer Rouge regime rebranded Kampuchea while all the killing was going on, from 1975 to 1979.

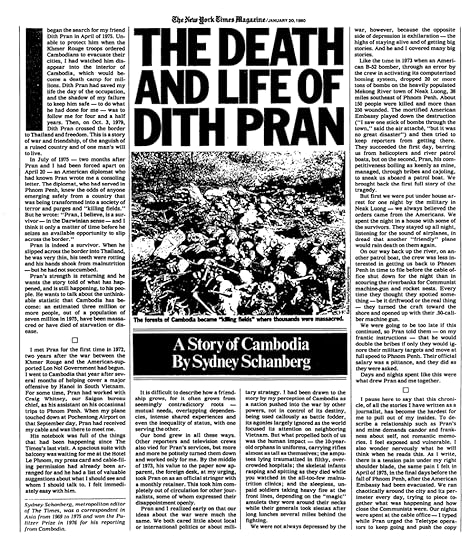

The first we in the West heard much about the situation was in the mid-70s, for example by this piece in the May 9, 1975 edition of The New York Times:

The link here goes to the paper’s TimesMachine archives. Seeing it requires a subscription. We’ll discuss this more below.

The link here goes to the paper’s TimesMachine archives. Seeing it requires a subscription. We’ll discuss this more below.It’s a front-page story by Sydney Shanberg, who himself becomes a character later (as we’ll see).

The first we (or at least I) heard about the genocide was sometime in 1976 or ’77, while watching Hughes Rudd on the CBS Morning News. He said something like this:

[image error]

Wierdly, it wasn’t the top story. It was like, “All these people died, back after this.”

So I went to town (Chapel Hill at the time) and bought a New York Times. There was … something small on an inner page, as I recall. (I’ve dug a lot but still haven’t found it.)

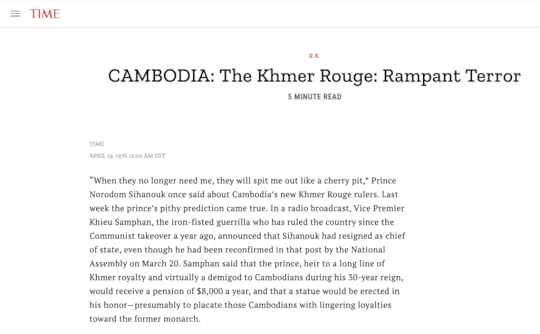

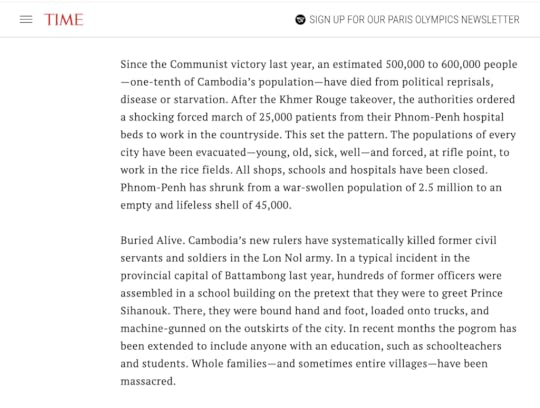

But Time, the weekly news magazine, did cover at least the beginning of the genocide, in the April 19, 1976 issue. (By the way, all hail to Time for its open archives. This is a saving grace I’ll talk about later, and much appreciated.) Here is how that story begins:

Note how Prince Norodom Sihanoouk stars in the opening sentence. He’s there because he was a huge character. (Go read about him. He was a huge piece of work, but not a bad one.) Pol Pot doesn’t appear at all. And the number of dead doesn’t show up until the second paragraph:

Coverage of Cambodia in the late ’70s remained sparse, considering the death count. Pol Pot didn’t show up in the Times until this was posted on page 164 of 446 in the massive Sunday paper on October 7, 1977:

The Times‘ most serious coverage of Cambodia was in opinion pieces. For example, an editorial titled The Unreachable Terror in Cambodia ran on July 3, 1978, and mentions Pol Pot in the third paragraph. Holocaust II!, by Florence Graves, ran on Page 210 of the November 26, 1978 Sunday Magazine. It begins, “They don’t talk about extermination ovens or about freaky medical experiments or about lampshades fashioned from human skin. But the Cambodian refugees do talk about forced labor camps, about “deportations,” and about mass executions.” Later she adds, “It’s a horror story which, for the most part, has gone unreported in the American press.”

It wasn’t reported because it wasn’t a story. Why:

No character of any interest (besides the deposed prince).A problem that was gigantic but not of much interest otherwise. At least not outside the region.Not much movement aside from a torrent of refugees into Thailand.Then came this, in January 1980:

In the opening paragraph, Sydney Schamberg writes, “This is a story of war and friendship, of the anguish of a ruined country and of one man’s will to live.” As human stories about genocides go, the only one that might top Dith Pran‘s is Anne Frank‘s. The new story was so compelling that four years later it became a huge movie:

And the Cambodian genocide has had plenty of coverage ever since. One guy’s story made all the difference. One guy.

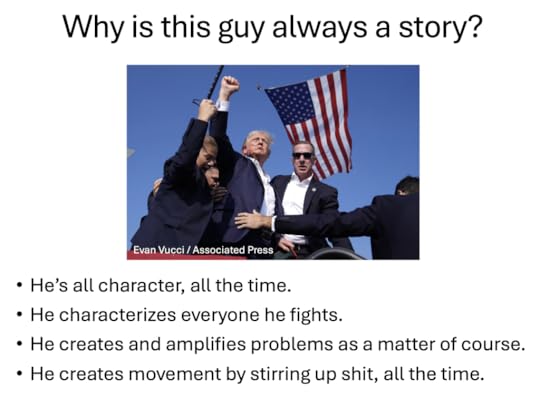

Now let’s go closer to home:

Trump is a genius at all that stuff. And he keeps his ball rolling by making shit up constantly. You’re a lot more free to tell stories—and to move them along—if facts don’t matter to you. Here’s how I put it in Stories vs. Facts:

Here are another three words you need to know, because they pose an extreme challenge for journalism in an age when stories abound and sources are mostly tribal, meaning their stories are about their own chosen heroes, villains, and the problems that connect them: Facts don’t matter.

Daniel Kahneman says that. So does Scott Adams.

Kahneman says facts don’t matter because people’s minds are already made up about most things, and what their minds are made up about are stories. People already like, dislike, or actively don’t care about the characters involved, and they have well-formed opinions about whatever the problems are.

Adams puts it more simply: “What matters is how much we hate the person talking.” In other words, people have stories about whoever they hate. Or at least dislike. And a hero (or few) on their side.

These days we like to call stories “narratives.” Whenever you hear somebody talk about “controlling the narrative,” they’re not talking about facts. They want to shape or tell stories that may have nothing to do with facts.

But let’s say you’re a decision-maker: the lead character in a personal story about getting a job done. You’re the captain of a ship, the mayor of a town, a general on a battlefield, the detective on a case. What do you need most? Somebody’s narrative? Or facts?

Depends on what you need. Donald Trump needs to win an election. He’ll do that with stories, just like he always has. As characters go, Kamala Harris is a much tougher opponent than Joe Biden was, because she’s harder for Trump to characterize, and she has plenty of character on her own. And both make good stories because they’re in a fight against each other.

Things are different in places like Bloomington, where people live and work in the real world.

In the real world, there are potholes, homeless encampments, storms, and other problems only people can solve—or prevent—preferably by working together. In places like that, what should journalists do, preferably together?

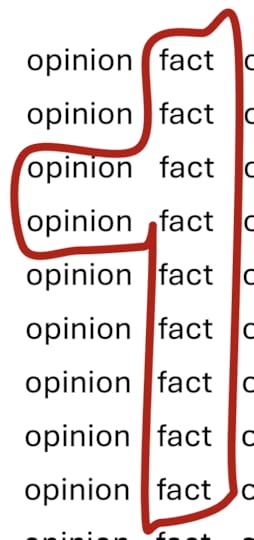

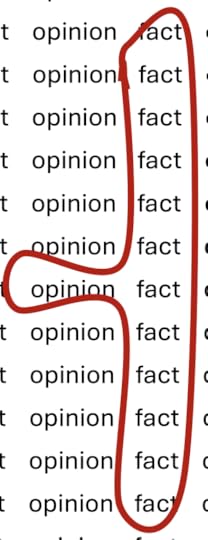

To clarify the options, look at journalism’s choice of sources and options for expression. Put simply, you’ve got facts and opinions. A typical story has a collection of facts, and some professor or other authoritative source provides a useful opinion about those facts. Sometimes both come from the same place, such as the National Weather Service. So let’s look at different approaches to news against this background:

Here is roughly what you’ll get from serious and well-staffed news organizations such as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the BBC, and NPR:

Mostly facts, but some opinions, typically in columns and on pages for that purpose.

How about research centers that publish studies and are often sourced by news organizations? Talking here about Pew, Shorenstein, Brookings, Rand. How do they sort out? Here’s a stab:

Lots of facts, plus one official opinion derived from facts. Sure, there are exceptions, but that’s a rough ratio.

How about cable news networks: CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and their wannabes? Those look like this:

These networks are mostly made of character-driven shows. They may be fact-based to some degree, but their product is mostly opinion. Facts are filtered out through on-screen performers.

Talk radio of the political kind is almost all opinion:

Yes, facts are involved, but as Scott Adams says, facts don’t matter. What matters are partisan opinions.

Sports talk is different. It’s chock full of facts, but with lots of opinions as well:

Blogs like the one you’re reading? Well…

In a general way, that’s what you get.

Finally, there’s Dave Askins. Here’s what he gives you in the B Square Bulletin:

[image error]

Dave is about facts. And that’s at the heart of his plan for making local journalism a model for every other kind of journalism that cares about being fully useful and not just telling stories all the time. One source he consulted for this plan is Bloomington mayor Kerry Thompson. When Dave asked her what might appeal about his approach, she said this:

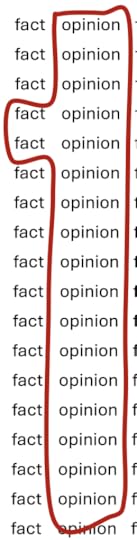

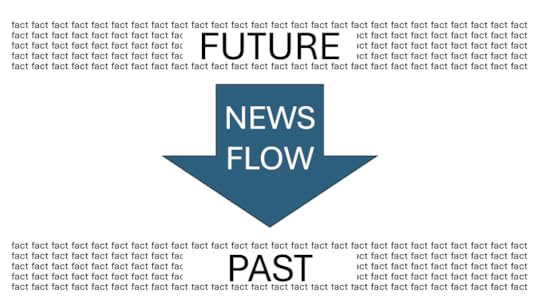

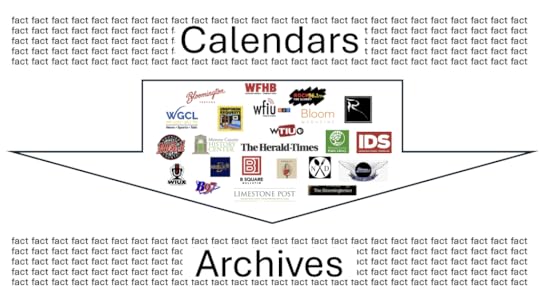

Dave sees facts flowing from the future to the past, like this:

The same goes for lots of other work, such as business, scholarship, and running your life. But we’re talking about local journalism here. For that, Dave sees the flow going like this:

[image error]

Calendars tell journalists what’s coming up, and archives are where facts go after they’ve been plans or events, whether or not they’ve been the subjects of story-telling. That way decision-makers, whether they be journalists, city officials, or citizens, won’t have to rely on stories alone—or worse: their memory, or hearsay.

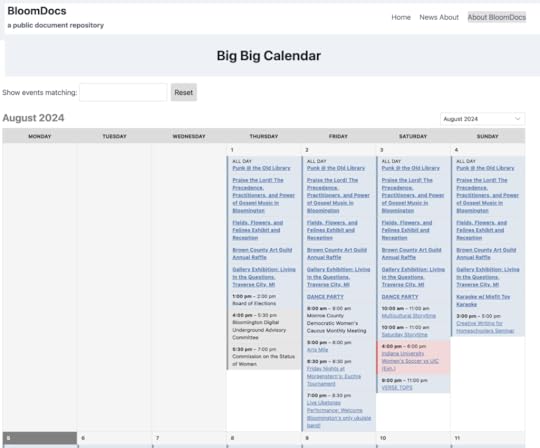

Dave has started work on both the future and the past, starting with calendars. On the B Square Bulletin, he has what’s called the Big Big Calendar. Here is how this month started:

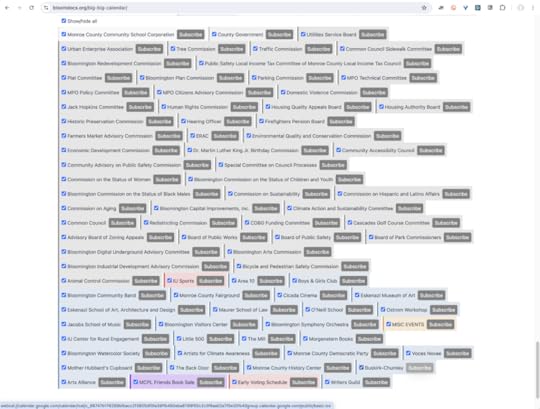

And here are the sources:

Every outfit Dave can find in the county that publishes a calendar and also has a feed is in there. They don’t need to do any more work than that. I suspect most don’t even know they syndicate their calendars automatically.

On the archive side, Dave has BloomDocs, which he explains this way on the About page:

BloomDocs is a public document repository. Anyone can upload a file. Anyone can look at the files that have been uploaded. That’s it.

What use is such a thing?

For Journalists: Journalists can upload original source files (contracts, court filings, responses to records requests, ordinances, resolutions, datasets) to BloomDocs so that they can link readers directly to the source material.

For Residents: Residents who have a public document they’d like to make available to the rest of the world can upload it to BloomDocs. It could be the government’s response to a records request. It could be a slide deck a resident has created for a presentation to the city council.

For Elected Officials: Elected officials who don’t have government website privileges and do not maintain their own websites can upload files to BloomDocs as a service to their constituents.

For Government Staff: Public servants who have a document they would like to disseminate to the public, but don’t have a handy place to post it on an official government website, or if they want a redundant place to post it, can upload the file to BloomDocs.

A future vision: “Look for it on BloomDocs” is a common answer to the question: Where can I get a copy of that document?

Dave also doesn’t see this as a solo effort. He (and we, at the Ostrom Workshop, who study such things) want this to be part of the News Commons I’ve been writing about here (this is the 12th post in the series). In that commons, the flow would look like this:

All the publishers, radio and TV stations, city and county institutions, podcasts, and blogs I show there (and visit in We Need Wide News and We Need Whole News) should have their own arrows that go from Future to Past, and from Calendars to Archives. And when news events happen, which they do all the time, and not on a schedule, those should flow into archives as well. We need to normalize those as much as we can.

Which brings us to money. What do we need to fund here?

Let’s start with the calendar. Dave’s big idea here is DatePress, which he details at that link. DatePress would be something WordPress might do, or somebody might do with WordPress (the base code of which is open source). I’m writing on WordPress right now. Dave publishes the B Square on WordPress. I’ll bet that the websites for most of the entities above are on it too. It’s the world’s dominant CMS (content management system). See the stats here and here.

On the archiving side, BloomDocs is a place to upload and search files, of which there are hundreds so far. But to work as a complete and growing archive, BloomDocs needs its own robust CMS, also based on open source. There are a variety of choices here, but making those happen will take work, and that will require funding. Archives, being open, should also be backed up at the Internet Archive as well.

Which brings us to money.

There are several possibilities, starting with funding Dave’s work so he can add functions and not do all of this himself.

Here are two aother ideas that aren’t the usual (advertising, subscriptions, subsidy).

The first is to drop the long-standing newspaper practice of locking up archives behind paywalls. (In Bloomington this would apply only to the Herald-Times). The new practice would be to charge for the news (if you like), but give away the olds. In other words, stop charging for access to archives. Be like Time and not the Times and nearly every other paper. (I first brought this up here in 2007.)

The second is to make EmancPay happen.

EmanciPay is an idea we cooked up in ProjectVRM at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center in 2009. Here’s how the description begins:

Simply put, Emancipay makes it easy for anybody to pay (or offer to pay) —

as much as they likehowever they likefor whatever they likeon their own terms— or at least to start with that full set of options, and to work out differences with sellers easily and with minimal friction.

Emancipay turns consumers (aka users) into customers by giving them a pricing gun (something which in the past only sellers used) and their own means to make offers, to pay outright, and to escrow the intention to pay when price and other requirements are met. And to be able to do this at scale across all sellers, much as cash, browsers, credit cards and email clients do the same. Payments themselves can also be escrowed.

In slightly more technical terms, EmanciPay is a payment framework for customers operating with full agency in the open marketplace, and at scale. It operates on open protocols and standards, so it can be used by any buyer, seller or intermediary.

It was conceived as a way to pay for music, journalism, or what any artist brings into the world. But it can apply to anything. For example, [subscriptions], which have become a giant fecosystem in which every seller has separate and non-substitutable scale across all subscribers, while subscribers have zero scale across all sellers, with the highly conditional exceptions of silo’d commercial intermediaries. As [Customer Commons] puts it,

There’s also not much help coming from the subscription management services we have on our side: Truebill, Bobby, Money Dashboard, Mint, Subscript Me, BillTracker Pro, Trim, Subby, Card Due, Sift, SubMan, and Subscript Me. Nor from the subscription management systems offered by Paypal, Amazon, Apple or Google (e.g. with Google Sheets and Google Doc templates). All of them are too narrow, too closed and exclusive, too exposed to the surveillance imperatives of corporate giants, and too vested in the status quo.

That status quo sucks (see here, or just look up “subscription hell”), and it’s way past time to unscrew it.) But how?

The better question is where?

The answer to that is on our side: the customer’s side.

While EmanciPay was first conceived by ProjectVRM as a way to make live payments to nonprofits and to provide a new monetization method for publishers. it also works as a counterpart to sellers’ subscription systems in what Zuora (a supplier of subscription management systems to the publishing industry, including The Guardian and Financial Times) calls the “subscription economy“, which it says “is built on ever changing relationships with your customers”. Since relationships are two-way by nature, EmanciPay is one way that customers can manage their end, while publisher-side systems such as Zuora’s manage the other.

More sources:

An Easy Way to Pay for Journalism, Music, and Everything Else We LikeAn Immodest Proposal for the Music IndustryA citizen-sovereign way to pay for news — or for any creative workThe New News BuisnessFar as I know, all the ideas you just read about are original, or close enough.

Let’s make them happen.

*Based on estimates. Nobody knows for sure. Here’s Wikipedia.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers