Doc Searls's Blog, page 22

May 28, 2024

The People’s AI

Prompt: “A vast field on which the ground spells the letters A and I, with people on it, having a good time.” Via Copilot | Designer

Prompt: “A vast field on which the ground spells the letters A and I, with people on it, having a good time.” Via Copilot | DesignerPeople need their own AIs. Personally and collectively.

We won’t get them from Anthropic, Apple, Google, Meta, or Microsoft. Not even from Apple.

All of those companies will want to provide AIaaS: AI as a Service, rather than AI that’s yours alone. Or ours, collectively.

The People’s AI can only come from people. Since it will be made of code, it will come from open-source developers working for all of us, and not just for their employers—even if those employers are companies listed above.*

That’s how we got Linux, Apache, MySQL, Python, and countless other open-source code bases on which the digital world is now built from the ground up. Our common ground is open-source code, standards, and protocols.

The sum of business that happens atop that common ground is incalculably vast. It also owes to what we first started calling because effects twenty years ago at Bloggercon. That was when people were making a lot more money because of blogging than with blogging.

Right after that it also became clear that most of the money being made in the whole tech world was because of open-source code, standards, and protocols, rather than with them. (I wrote more about it here, here, and here.)

So, thanks to because effects, the most leveraged investments anyone can make today will be in developing open source code for The People’s AI.

That’s the AI each of us will have for our own, and that we can use both by ourselves and together as communities.

Those because investments will pay off on the with side as lavishly as investments in TCP/IP, HTTP, Linux, and countless other open-source efforts have delivered across the last three decades.

Only now they’ll pay off a lot faster. For all of us.

*See what I wrote for Linux Journal in 2006 about how IBM got clueful about paying kernel developers to work for the whole world and not just one company.

May 16, 2024

Blog + Newsletter

Newsletters are all the rage now. In recognition of that, I blogged here two years ago about the idea of writing a solo newsletter. Since then I’ve been co-producing this one with Katherine Druckman at Reality 2.o. It’s a Substack one, so I know how that game works on the production as well as the consumption ends.

Recently I also learned that WordPress makes it easy to turn blogs into newsletters, which is why you see “Get New Posts by Email” in the right column here. So, wanting an image to go with the news that this blog can now be a newsletter if you like, I said to ChatGPT, “Draw me Doc Searls blogging on the left side of the image, and producing a newsletter on the right side.” It gave me this, including the caption:

Here’s the illustration depicting Doc Searls engaging in two different activities. On the left, he is blogging, and on the right, he is producing a newsletter. This split scene captures his multitasking abilities in digital content creation.

Here’s the illustration depicting Doc Searls engaging in two different activities. On the left, he is blogging, and on the right, he is producing a newsletter. This split scene captures his multitasking abilities in digital content creation.Except for the slouch, I never looked like that. But what the hell. AI is wacky shit, so there ya go.

Feel free to subscribe.

May 10, 2024

Personal vs. Personalized AI

There is a war going on. Humanity and nature are on one side and Big Tech is on the other. The two sides are not opposed. They are orthogonal. The human side is horizontal and the Big Tech side is vertical.*

The human side is personal, social, self-governed, heterarchical, open, and grounded in the physical world. Its model is nature, and the cooperative contexts in which competition, creation, and destruction happen in the natural world.

The Big Tech side is corporate, industrial, hierarchical, competitive, mechanistic, extractive, and closed, even though it produces many positive-sum products and services that are good for people and good for nature. It is also, being competitive and rewarding toward winner-take-most outcomes, dominated by giants.

This war has been fought over many other things in the past, especially in tech. But AI is the big one right now—and perhaps the biggest one of all time.

Over the long run, both sides will win, because we need the best of what both bring to the world’s big round table. In the past, this has happened in countless markets, countries, polities, societies, and other contexts. In tech it happened with the conflict between PCs and mainframes, between the open and public Internet and closed private networks, and between open operating systems and closed ones. None of those conflicts have final outcomes, but they have arrived at stable and cooperative states. They arrived at those states because everyone recognized that people can do more with their tools than those big entities can do on their own, or by using people as extracted resources.

This conflict is perhaps best represented by the ironies that have been at work within OpenAI and Sam Altman, its prior and current CEO. We can also see it with sparkling clarity in something amazing that Sam said near the close of his keynote at the first OpenAI Developer Conference, in November of last year:

Lets unpack that.

Individual empowerment means exactly what it says. Agency is the ability to take action or to choose what action to take (Cambridge Dictionary). Scale means growth toward ubiquity.

You have individual empowerment and agency when you ride your bike, drive your car, mow your lawn, or button your shirt. You also have it when you work on your laptop, phone, and other smart rectangles. Scale means your power and agency will grow to the max while the same will happen for nearly everyone else. Scale for you alone won’t cut it. When most of us have it, that’s scale.

Technologies extend us. They enlarge our capacities in the world. Intelligence is one of those capacities. So is memory. Your rectangles help a lot with both. That’s why those have already scaled to ubiquity, or close enough.

AI will do the same, but only if it’s personal. Not if it’s just”personalized.”

ChatGPT4 doesn’t know that yet. I can tell because I just asked:

Me:

What is “personal AI”?ChatGPT4:

“Personal AI” refers to artificial intelligence systems that are designed to serve individual users through personalized interactions and services. These AI systems learn from the specific preferences, behaviors, and needs of their users to offer more tailored assistance, recommendations, or information. The goal of personal AI is to enhance user experience by adapting to unique personal profiles.There are various applications of personal AI, including:

Virtual Assistants: Like Siri, Google Assistant, and others, these AIs help with daily tasks such as scheduling, reminders, searching information, and controlling smart home devices, all customized to the user’s habits and preferences.Recommendation Systems: Used in streaming services like Netflix or shopping platforms like Amazon, these AI systems analyze your past behavior to recommend movies, shows, or products you might like.Healthcare: Personal AI can track individual health metrics and provide personalized advice, monitor conditions, or even alert medical professionals if needed.Learning and Development: In education, personal AI can adapt learning materials to the pace and learning style of the student, offering a customized educational experience.Gaming: AI in gaming can adapt to provide a challenge tailored to the player’s skill level or alter the game narrative based on choices made by the player.The development of personal AI focuses on enhancing user engagement by creating more intuitive and responsive interactions that feel uniquely suited to each individual.

For a second opinion, I asked Google’s Gemini the same question.

Me:

What is “personal AI”?Gemini:

Personal AI refers to artificial intelligence designed to assist and interact with a specific individual. It’s essentially your own AI companion that learns about you and tailors its services to your needs. Here are some key aspects of personal AI:

Personalization: Unlike general-purpose AI assistants, personal AI focuses on you. It learns from your interactions, preferences, and habits to become more helpful over time.Focus on Memory and Knowledge: Some personal AI systems aim to become an extension of your mind. They can store your memories, knowledge, and experiences, making them readily accessible and even usable to help with tasks like writing or communication.Varied Applications: Personal AI can have a wide range of applications. Imagine an AI that helps you:Organize your life: Manage schedules, appointments, and reminders.Boost productivity: Assist with tasks, research, and communication.Enhance creativity: Help you brainstorm ideas or generate creative content.Improve learning: Personalize learning experiences and provide targeted information.Privacy Concerns: Storing personal data on an AI raises concerns about privacy and security.

Overall, personal AI holds promise for a future where technology seamlessly integrates with our lives, offering personalized assistance and support.

To both companies, personal AI is a personalized service—from them. It’s not something you own and control. It’s not about individual empowerment and agency. It doesn’t extend you. It’s hired prosthesis: an extension of them rather than of you.

But hats off. OpenAI and Gemini do an amazing job. So do lots of other AI services by wannabe giants. I use AI every day to improve what I write, to generate and fix images, to answer questions that old-fashioned search engines can’t answer or suck at. I even pay extra for some of it (such as ChatGPT4 and Adobe’s Creative Suite). And it seems they all get better, all the time, at everything. Won’t personalization be good enough, eventually?

No. Because they aren’t you. They also aren’t yours, so they can’t extend you. They can seem to. But they don’t. They also don’t have access to most of your private life. Nor should they.

But your private life could use some AI help. For example—

Schedules, including on your calendars, past and futureHealth data, including all your medical reports, prescriptions, appointments, insurance information, past and present providers, plus what your watch, phone, and other devices record about youFinancial records, including bills, receipts, taxes, and anything called an account that involves moneyTravel, including all the movements your phone (and phone company), watch, and car record about where you go and where you’ve beenWork—past and present, including whatever HR systems know or knew about youContacts—all the people, businesses, and other entities you knowBusiness relationships, with brokers, retailers, service providers, whateverSubscriptions, including all those “just $1 for the first four weeks” offers you’ve accepted, plus other forms of screwage that are stock-in-trade for companies selling subscription systems to businesses.Property, including all the stuff on your shelves, floors, closets, garages, and storage spaces—plus your stocks and real estate.It’s not easy to visualize what a personal AI might do for those, but let’s try. Here’s how Microsoft’s Copilot (or whatever it’s called this week) did it for me before I got rid of all its misspellings and added my own hunks of text:

All that stuff is data. But most of it scattered between apps and clouds belonging to Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, phone companies, cable companies, car makers, health care systems, insurance companies, banks, credit card companies, retailers, and other systems that are not yours. And most of them think that data is theirs and not yours.

To collect and manage all that stuff, you need tools that don’t yet exist: tools that are yours and not theirs. We could hardly begin to imagine those tools before AI came along. Now we can.

For example, you should be able to take a picture of the books on your shelves and have a complete record of what those books are and where you got them. You’ll know where you got them because you have a complete history of what you bought, where and from whom. You should be able to point your camera in your closets, at the rugs on your floors, at your furniture, at the VIN number of your car that’s visible under your windshield, at your appliances and plumbing fixtures, and have your AI tell you what those are, or at least make far more educated guesses than you can make on your own.

Yes, your AI should be able to tap into external databases and AI systems for help, but without divulging identity information or other private data. Those services should be dependent variables, not independent ones. For full individual empowerment and agency, you need to be independent. So does everyone else with personal AI.

Now imagine having a scanner that you can feed every bill, every receipt, every subscription renewal notice, and have AI software that tells you what’s what with each of them, and sorts records into the places they belong.

Ever notice that the Amazon line items on your credit card bill not only aren’t itemized, but don’t match Amazon’s online record of what you ordered? Your personal AI can sort that out. It can help say which are business and personal expenses, which are suspicious in some way, what doesn’t add up, and much more.

Your personal AI should be able to answer questions like, “How many times have I had lunch at this place? Who was I with? When was it we drove to see so-and-so in Wisconsin? What route did we take? What was that one car we rented that we actually liked?

Way back in 1995, when our family first got on the Internet over dial-up, using the first graphical browsers on our PC, and e-commerce began to take off with Amazon, eBay, and other online retailers, my wife asked an essential question: Why can’t I have my own shopping cart that I take from site to site?

Twenty-nine years later, we still don’t have the answer, because every retailer wants you to use its own. And we’re stuck in that system. It’s the same system that has us separately consenting to what sites ironically call “your privacy choices.” And aren’t.

There are countless nice things we can’t have in the digital world today because we aren’t people there. We are accounts. And we are reduced to accounts by every entity that requires a login and password.

This system is a legacy of client-server, a euphemism for slave-master. We might also call it calf-cow, because that’s how we relate to businesses with which we have accounts. And that model is leveraged on the Web like this:

We go to sites for the milk of content and free cookies, whether we want them or not. We are also just “users.”

In the client-server world, servers get scale. Clients have no more scale than what each account—each cow—separately allows. Sure, users get lots of benefits, but scale across many cows is not one of them. And no, “login with Google” and “login with Facebook” are just passes that let calves of ruling cows wander into vassal pastures.

For individual empowerment and scale to happen, we need to be self-sovereign and independent. Personal AI can give that to us. It can do that by solving problems such as the ones listed above, and by working as agents that represent us as human beings—rather than mere users—when we engage with Big Tech’s cows.

This will be a fight at first, because the cows think they run all of nature and not just their own farms. And $trillions are being invested in the same old cattle industry, with AI painted all over the new barns. Comparatively speaking, close to nothing is going toward giving independent and self-sovereign individuals the kind of power and scale Sam Altman says he wants to give us but can’t because he’s on the big cow side of this thing.

So where do we start?

First, with open source code and open standards. We have some already. Llama 3, from Meta AI, is “your own intelligent assistant,” and positions Meta as a more open and user-friendly cow than OpenAI. But Meta is still on the top-down Big Tech side of the war we’re in. But hell, we can use what they’ve got. So let’s play with it.

Here on the ground there are all these (with quotage lifted from their sites or reviews such as this one)—

MindsDB: “an open-source AutoML framework”Keras: “a multi-backend deep learning framework, with support for JAX, TensorFlow, and PyTorch”PyTorch: “Python package that provides two high-level features: Tensor computation (like NumPy) with strong GPU acceleration, and Deep neural networks built on a tape-based autograd systemTensor Flow: “open-source framework for machine learning”CoreNet: a deep neural network toolkit for small and large-scale models, from AppleHaystack: an “open source Python framework by deepset for building custom apps with large language models (LLMs).” Image Super-Resolution (ISR): “(an) open source tool employs a machine learning model that you can train to guess at the details in a low-resolution image:Blender: “A rich interface and numerous plugins make it possible to create complex motion graphics or cinematic vistas”DeepFaceLab: “open source deepfake technology that runs on Python”tflearn: “an advanced deep learning library”PYTensor: “a Python library that allows you to define, optimize/rewrite, and evaluate mathematical expressions involving multi-dimensional arrays efficiently.” (Was Theano)HuggingFace Transformers: “a popular open-source library for Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks”Fast.ai: “a library for working with deep learning tasks”OpenCV: “a popular Computer Vision and Image Processing library developed by Intel”Detectron2: “a next-generation library that provides advanced detection and segmentation algorithm”Ivy.ai: “an open-source deep learning library in Python focusing on research and development”OpenAssistant: “a project aimed at giving everyone access to a great chat-based large language model”PaddleNLP: ” a popular open source NLP library that you can use to glean search sentiment and flag important entities”Fauxpilot: an open-source locally hosted alternative to the GitHub Copilot serverRay: “An open source framework to build and scale your ML and Python applications easily”Solid: “Solid is a specification that lets individuals and groups store their data securely in decentralized data stores called Pods. Pods are like secure web servers for data. When data is stored in a Pod, its owners control which people and applications can access it.”YOLOv7: “is one of the fastest and most accurate open source object detection tools. Just provide the tool with a collection of images full of objects and see what happens next.”—and lots of others that readers can tell me about, and to which I will add links later. Because this is a work in progress.

I believe, however, that we need something Linux-like in the sense that it becomes the open base on which lots of other stuff runs. The closest I’ve seen so far is pAI-OS, by Kwaai.ai, a nonprofit I now serve as Chief Intention Officer. I got recruited by Reza Rassool, Kwaai’s founder and chair, because he believes personal AI is required to make The Intention Economy finally happen. So that was a hard offer to refuse. Kwaai also has a large, growing and active community, which I believe is both necessary and cool.

As with most (maybe all) of the projects listed above, Kwaai is a grass-roots effort by human beings on the natural, human, and horizontal side of a battle with giants who would rather give us personalized AI than have us meet them in the middle with personal AI powers of our own. In the long run we will meet in that middle. Because personal AI will be better for everyone than personalized AI alone. Watch us prove it. Better yet, join the effort.

*I am indebted to Lavonne Reimer for introducing and co-thinking the horizontal vs. vertical frame, and look forward eagerly to her own writings and lecturings on the topic.

May 7, 2024

Burning to Write. And Vice Versa.

I shot this photo in July 2007, while sitting with friends in that same booth at the Eagle and Child in Oxford.

I shot this photo in July 2007, while sitting with friends in that same booth at the Eagle and Child in Oxford.Among all artists, writers alone suffer the illusion that the world needs to hear what they have to say.

I thought that line, or something like it, came from Rollo May, probably in The Courage to Create. But a search within that book says no. ChatGPT and Gemini both tell me May didn’t say it anywhere.

Still, I think it’s true that writers write because they have to. They can’t not write. It’s what they do, how they live. And I’m one of them.

The need to write is for me a vivid fact this morning, a few days past a catheter ablation on my heart. There is so much I need to say, because I suffer the illusion that the world needs to hear it. Does it?

I am sure C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkein had the same affliction. I am also sure that the world is better for having read both of them, even if the world could have lived without their writing.

As for time, I have had twelve more years to write than Lewis got, so far, and five less than Tolkein.

Time to say what?

I want to say that personal AI will do far more for all of us than what we will ever get from AI as a corporate service. And to say it better than I just did.

I want to say that we will do better with rulers who care about people than with rulers who merely rule. And to say that better than I just did.

I want to complete the work of John McPhee by reporting as best I can what has happened to the great characters that anchored every one of his essays and books. But that project is not on the back burner. It’s in the fridge, where I’ve kept it for decades (while continuing to read the entire McPhee oeuvre, much of it repeatedly).

Speaking of burning, I am impelled by Dylan Thomas, who wrote “Do not go gentle into That Good Night,” before dying at just thirty-nine. The poem was for his father:

Old age should burn and rave at close of day,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And so I do.

May 2, 2024

World Wide Whiteboard

We thought the Web was a library. Turns out it’s not. (Image via ChatGPT 4o.)

We thought the Web was a library. Turns out it’s not. (Image via ChatGPT 4o.)Before there were search engines, there were directories. The biggest and best-known was Yahoo. On the first graphical browser (Mosaic), it looked like this:

The directory idea made sense, because the Web is laid out like the directory in your computer. There is a “domain” with a “location” or a “site,” containing something after the last / in a path of /something/something/something. Geeks call these directories too, and the string of somethings a path. Directories in computing also follow an outline format: heads, subheads, and subheads of subheads.

While this design is boundlessly flexible, it also suggests durability, if not permanence, because it’s good to find stuff where it rightly goes and to find it in the same place over and over again.

That was what Yahoo assumed in the early days of the Web—as did everyone who bought a domain name. I’ve had searls.com since 1995. Dave Winer (father of outlining and progenitor of much else) has had Scripting.com for even longer (and has a lot more in that domain).

But we don’t own domain names. We rent them. And the World Wide Web isn’t a library. It’s a whiteboard with stuff written on it. Some of that stuff is located on directory paths. A lot more is coughed up by database systems on an as-needed basis.

The Yahoo directory failed. In its place search engines appeared. Search engines don’t catalog the Web like a library might. They index it. That means they send crawlers down the Web’s directory paths, recording everything they see into a searchable index. I explain here how that works and where this went:

The Web is a haystack.

This isn’t what Tim Berners-Lee had in mind when he invented the Web. Nor is it what Jerry Yang and David Filo had in mind when they invented Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web, which later became Yahoo. Jerry and David’s model for the Web was a library, and Yahoo was to be the first catalog for it. This made sense, given the prevailing conceptual frames for the Web at the time: real estate and publishing.

Both of those are still with us today. We frame the Web as real estate when we speak of “sites” with “locations” in “domains” with “addresses” you can “visit” and “browse”—then shift to publishing when we speak of “files” and “pages,” that we “author,” “edit,” “post,” “publish,” “syndicate” and store in “folders” within a “directory.” Both frames suggest durability if not permanence. Again, kind of like a library.

But once we added personal movement (“surf,” “browse”) and a vehicle for it (the browser), the Web became a World Wide Free-for-all. Literally. Anyone could publish, change and remove whatever they pleased, whenever they pleased. The same went for organizations of every kind, all over the world. And everyone with a browser could find their way to and through all of those spaces and places, and enjoy whatever “content” publishers chose to put there. Thus the Web grew into billions of sites, pages, images, databases, videos, and other stuff, with most of it changing constantly.

The result was a heaving heap of fuck-all.*

Back in 2005, I wrote in Linux Journal about a split between the “static” Web that was like a library (with its “locations,” “sites,” and “domains” you could “visit” and “browse”), and the “live” Web of blogs and posts. Then social media came along, and the live branch of the Web outgrew the static Web’s trunk.

Last week came news that a leak revealed lots of interesting poop about how Google actually ranks search results. Here are two things I don’t need those leaked documents to tell me:

Google favors the present over the past, the current over the archival.Google no longer indexes, or ranks very old Web pages.I speak from experience here, because I have some old pages that are on the Web but don’t seem to be indexed, meaning searches don’t find them. I also have Easter eggs on a couple of those pages: words that exist in no language but made those pages easy to find when I did keyword searches for them. Now I get “No results found for _____.” (I won’t reveal the word because I want to keep testing Google.)

Countless publications have also come and gone on the Web without leaving a trace. Upside was a gigantic publication from the Nineties through the dotcom boom. Not a trace of it remains. Far as I know, nothing remains of Fast Company‘s early issues.

But hey, God bless the Internet Archive. Here’s a piece I wrote for PC Magazine in December 1982 about a PC application that taught card counting in blackjack:

As the evanescence of “content” increases, so does the importance of archives.

So maybe stop reading here and start reading here. We have a lot of work to do.

April 21, 2024

Archives as Commons

The Santa Barbara library, viewed from the county courthouse. Is this where the dead local paper’s archives will go? How about future archives of all the local news organs?

The Santa Barbara library, viewed from the county courthouse. Is this where the dead local paper’s archives will go? How about future archives of all the local news organs?The Santa Barbara News-Press was born in 1868 and died in 2023 at age 155. Its glory years ran from 1932 until 2000, when the New York Times sold it to Wendy McCaw, who rode it to hell.

That ride began with the Santa Barbara News Press Controversy in 2006 and ended when Ampersand, the company McCaw created to hold the paper’s bag of assets (which did not include its landmark building downtown, which McCaw kept), filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in late July of last year. Here are stories about the death of the paper in three local news journals that have done a great job of taking up the slack left when the News-Press began to collapse, plus one in the LA Times:

‘Santa Barbara News-Press’ Files for Bankruptcy: Publisher Ampersand Claims Few Assets and Many Creditors, by Jean Yamamura in the Santa Barbara Independent (July 23, 2023)Santa Barbara News-Press Declares Bankruptcy, Staff Told All Jobs ‘Eliminated’, by Joshua Molina, in Noozhawk (July 23, 2023)Santa Barbara News-Press Files for Bankruptcy, Staff Fired, by Edhat Staff (July 24, 2023)Santa Barbara News-Press bankruptcy brings uneasy end to an owner’s bitter tenure, by James Rainey, in the Los Angeles Times. (July 29, 2023)I followed those with this in We Need Deep News:

From what I’ve read so far (and I’d love to be wrong) none of those news reports touch on the subject of the News-Press‘ archives, which conceivably reach back across the century and a half it was published. There can’t be a better first draft of history for Santa Barbara than that one. If it’s gone, the loss is incalculable. (August 18 2023)

Last month brought bad news about that:

‘Santa Barbara News-Press’ Online Assets to Be Sold: Bankruptcy Sale for $250,000 Subject to Bids in April, by Jean Yamamura in the Santa Barbara Independent March 8, 2024A local paper went bankrupt. Now a faraway buyer wants its assets: The Santa Barbara News-Press’s digital assets are up for sale. Locals worry they could become a farm for AI-generated SEO bait. By Ernie Smith in Fast Company. (March 5, 2024)Santa Barbara’s Collective Memory, Sold for Kindling: Will ‘NewsPress.Com’ Become a Zombie Website? by William Belfiore in the Independent. (March 29, 2024)But then, thanks to William Belfiore’s appeal in that last piece, we learned this:

‘Santa Barbara News-Press’ Website Goes to ‘Local Kids’ Group Fronted by Ben Romo Makes Winning Auction Bid of $285,000, by Jean Yamamura in the Independent (Apr 09, 2024)The only mention of archives was in the closing sentences of that piece:

The purchase of the website included the Santa Barbara News-Press trademark, which would be important to the groups looking at the physical archive of back issues, photographs, and clippings by topic. Romo, who was once a paper boy for the daily, acknowledged that his group was supportive of the archive remaining local, too.

I don’t know what that means, and I haven’t checked. But I am sure that the archives ought to be managed by the community as a common pool resource.

As it happens, my wife and I are visiting scholars at the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University, which is concerned with this kind of thing, because its namesake, Elinor Ostrom, won a Nobel Prize in Economics for her work on how commons are self-governed. In her landmark book, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, she lists eight principles for managing a commons, which are summarized here:

Define clear group boundaries.Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions.Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules.Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities.Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior.Use graduated sanctions for rule violators.Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution.Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.Journalists, especially those who report news, are not herding animals. They tend to be competitive and territorial by both nature and purpose. So the collection of news entities I wrote about in We Need Wide News and We Need Whole News will almost certainly not cohere into a commons such as Lin (her nickname) Ostrom addresses in that list.

But they should cohere around archives—not only because that’s the right thing to do, but because they need those archives. We all do.

So I hope Santa Barbara’s many journals, journalists, friends, supporters, and interested local institutions get together around this challenge. Build a commons around those archives, whatever and wherever they happen to be.

Meanwhile here in Bloomington, my other hometown, we are pushing forward with The Online Local Chronicle that Dave Askins wrote about in the previous installment in this series. We might call that a commons interest here.

April 20, 2024

This Thing is Bigger Than Journalism

Journalism as we knew it is washing away. But the story is bigger than journalism alone, and bigger than a story alone can tell. (Image borrowed from the brilliant Despair.com.)

Journalism as we knew it is washing away. But the story is bigger than journalism alone, and bigger than a story alone can tell. (Image borrowed from the brilliant Despair.com.)We who care about journalism are asked to join the Save Journalism Project, and its fight against Big Tech. Their pitch begins,

and adds,

On the first point, we should note that journalists have been working for magazines, broadcasters, newsletters and themselves for many dozens of years. So journalism isn’t just about newspapers. Also, because so many journalists have long made livings in those other media, the loss of work is far greater than the 2,400 gone from newspapers. It’s truly massive. I don’t know any field where the loss of paying jobs is larger on a percentage basis. Not taxi driving, not hospitality, not retail, not manufacturing… not anything I can think of. (Well, maybe nuns. I don’t see many of those these days.)

We should also respect the simple fact that now there is more journalism than ever: in blogs, social media, podcasting, and other places. Most of those kinds of journalism don’t pay, but that doesn’t disqualify the work from the label. Hell, I’m committing journalism here and this doesn’t pay.

“The story of big tech’s threat to journalism” (what the Project wants us all to tell) is also something of a red herring because it distracts our attention from causes much bigger than Big Tech.

Every new technology “works us over completely,” Marshall McLuhan says (in The Medium is the Massage). And no new medium, no new technologies, have ever worked us more than the digital kind. The change began with digital tech and integrated circuits and then went absolute with the Internet. Together, digital technologies and the Internet have radiacally changed our species, our civilization, and our planet.

Not long ago, in a conversation about this with Joi Ito, I asked him how big he thought the digital transformation was. Bigger than broadcast? Print? Writing? Speech? Stone tools?

“No,” he replied. “It’s the biggest thing since oxygenation.” In case you don’t remember, that happened between about two and a half billion years ago. (Joi also writes about it here.)

So, while journalism matters enormously, it’s just one casualty of digitalization. And, let’s face it, a beneficiary as well. Either way, we need to understand the whole picture, which is about a lot more than what journalism sees happening in the mirror.

Here’s one outfit working on that bigger picture. I‘m involved with it.

I also don’t expect most journalists to take much interest in the subject, because it’s too big, and it doesn’t make full sense as a story, which is journalism’s stock in trade. (I explain a bit about journalism’s “story problem” in this TEDx talk.)

Still, some journalists are on the case, including me. Love to have others join in. But please don’t bother if you think Big Tech is alone to blame. Because the story is bigger than that, and far more than a story.

I just copied and pasted this post from here in Medium, where I posted it in July 2019. It expands on a post now archived here. It’s kinda sad that not much has changed over all that time.

April 8, 2024

Aviation vs. Eclipse

Contrails in the stratosphere, smearing sideways into broad cloud cover. This view is toward the place in the sky where a full solar eclipse will happen a few hours later.

Contrails in the stratosphere, smearing sideways into broad cloud cover. This view is toward the place in the sky where a full solar eclipse will happen a few hours later.Contrails form behind jet aircraft flying through the stratosphere. Since high-altitude aviation is happening all around the earth more or less constantly, planes are painting the sky everywhere. (Here is one time-lapse.)

Many contrails don’t last, of course, but many do, and together they account for much of the cloud cover we see every day. The altocumulus, altostratus, and cirrus clouds that contrails produce are now officially recognized as homogenitus and homomutatus, which are anthropogenic: owing to human activity.

And today, Eclipse Day, Delta is offering to fly you along the path of totality. Others too? I don’t know. I’m taking a few moments to write this before we walk up to our hilltop cemetery to watch the eclipse for over four minutes, thanks to our lucky location near the very center of Totality.

I’m curious to see and hear contrail reports from others now awaiting their few minutes out of the sun.

1:14pm—The moon’s shadow made landfall in Mexico a short time ago. Here in Bloomington, the sky is well-painted by contrails. Mostly it looks like high-altitude haze, but believe me: if it weren’t for commercial aviation, the sky would be solid blue. Because the contrails today are quickly smeared sideways, losing their form but not their color.

April 5, 2024

Talking Artificial Intelligence with the Real Don Norman

Artificial is AI’s frst name. And Intelligence is a quality, not a quantity. You can’t measure it with a dipstick, a ruler, or an IQ test. If you could, you’d get the same result every time.*

But being artificial doesn’t mean AI isn’t dangerous, fun or both. It is, and will be, what we make of it.

That’s what Don Norman says, and he’s been publishing in AI journals since 1973. His laboratory produced the first multi-layer neural nets in the 1980s. He wrote Things that Make us Smart in 1993.

In the opinion of myself and countless others, Don is also the foremost authority on design—of anything and everything. For more on that, check out Don’s Web page, his Wikipedia page, and his books. Or, if you just want to sample some of his thoughts on AI, watch this.

Or you can skip all that and come to the good stuff: joining us in a talk with Don in the final salon of this semester on the topic of Artificial +/vs. Human Intelligence. It’s next Tuesday, April 9, at Noon Eastern time. (That’s less than 24 hours after the shadow of the Moon passes over the Indiana University campus. Yes, totality will be local here.)

Also, this won’t be a lecture or a presentation. It will be a lively discussion because Don is especially good at that.

It’s also free and online, but you have to register first. Do that here.

*For what it’s worth, my own known IQ test scores have an 80-point range. I’ve written about that, and the myth of “IQ” here, here, here, here, and I suppose in too many other places.

April 4, 2024

Fishing For Free TV Signals

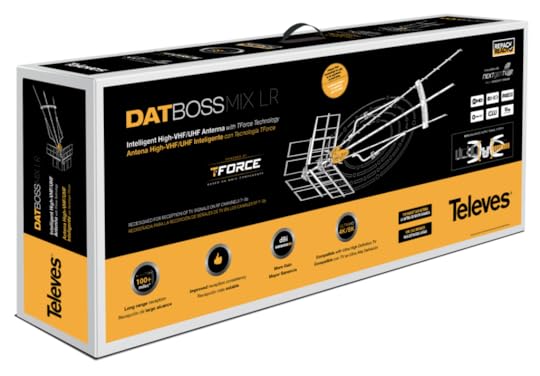

By expert acclaim, this is the best antenna for receiving hard-to-get over-the-air (OTA) TV signals

By expert acclaim, this is the best antenna for receiving hard-to-get over-the-air (OTA) TV signalsI think I will be the last person in Bloomington to try getting free over-the-air TV from what’s left of all the major networks. But that’s just my style, so roll with me while I explain how I’m hoping to do it, with the antenna above, which I’ll need because here is what the Search Map at RabbitEars.info says we might get here:

We live next door right now, and the top station above, WTIU from Indiana University (our PBS affiliate), comes from a tower you can walk to from here. We can get that signal by using a straightened paper clip for an antenna. (You jam the clip into the center hole of the coaxial connector in the back of the TV.) Even a real indoor antenna connected to the same jack gets nothing else.

But this Televes antenna might do the job because we’re on the slope of a hill that faces the Indianapolis stations that carry CBS, ABC, NBC, and Fox. These range from 27 to 54 miles away, in roughly the same direction. VHF and UHF signals always gain strength when they hit the faces of hills, similar to how surf builds as it approaches a sand bar or a shore. Also, the Televes DAT BOSS antenna gets great reviews:

TechHive: Televes Dat Boss Mix LR review: This is a great outdoor antennaTyler the Antenna Guy: Televes DATBOSS LR Mix Outdoor Antenna Review 149883Solid Signal: ALL NEW Televes DATBOSS Mix LR Antenna TESTED (w/assembly instructions)Amazon: Televes DAT Series BOSS Mix LR Outdoor High-VHF/UHF HDTV Antenna (see the reviews)I was going to put it in our new attic before the drywall goes up. However, the attic space is low and full of close cross-braces. Worse, the antenna is not small and kinda complicated to fit in a space that’s a web of short 2x4s. Dig:

So it will go on a pole in the backyard and feed a coaxial line that will tunnel through conduit under the yard and inside to the new living room.

But I would like to test it first, preferably with a tuner gizmo I can plug into my laptop. I had one of those for years: the Elgato EyeTV Hybrid TV Tuner stick, which looked like a fat thumb drive,with USB-A at one end and a coax connector for an antenna at the other. It picked up analog and digital TV, on every North American channel, and came with good software that ran on a Mac. Far as I can tell there are no replacements out there. If anybody knows of one, please tell me. My only other option is to get a cheap TV and try that out. Any advice is welcome. Thanks!

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers