Doc Searls's Blog, page 20

October 3, 2024

Think Globally, Eat Here

Fifteenth in the News Commons series.

This semester’s Beyond the Web salon series for the Ostrom Workshop and Hamilton Lugar School at Indiana University is themed Think Globally, Eat Here—Small Solutions for Big Tech Problems. I will give the opening talk, about the News Commons (subject of fourteen prior posts here) at noon (Eastern) next Tuesday, October 10. If you’re in town, please attend in person. If not, join us by Zoom. Do that here.

Our plan is to prototype and prove locally what can apply globally for local news, starting with what Columbia Journalism Review called “news deserts” back in 2017—a label that has since caught on. There are many efforts toward seeding and watering these deserts, most prominently Press Forward, which is devoting $500 million to that challenge.

Bloomington is advantaged by not being one of those deserts, and instead having a talented pool of local journals, journalists, and organizations—including its legacy newspaper—all doing good work that could still be improved by putting to use some of the innovations I’ll be talking about, and by working together as a commons.

So join the conversation. I look forward to seeing you in the room or on the wall (because one whole wall is our Zoom screen).

October 1, 2024

2024_10_01 Postings

Croissants (the edible kind) on display at Peets in Santa Barbara.

Croissants (the edible kind) on display at Peets in Santa Barbara.A radio item

Over on my blog about infrastructure, I put up a brief post about WART, volunteer-powered community radio station with studios in a railroad caboose, that was lost in the flood that just devastated Marshall, North Carolina.

Write once, publish everywhere

Dave turned me on to Croissant today. Looks good. I’d even be willing to pay the monthly fee to post once across Bluesky, Mastodon, Threads, and Xitter. But it appears to be only for iOS mobile devices. I have some of those (including a new iPhone 16 Pro), but I mostly write on a computer. So I’ll hold out for real textcasting, like Tim Carmody talks up here. Because why should you have to post separately at all those places? Why should you have to go to a place at all, when you’ve got your own devices to write on and distribute from?

A heading convention

I started curating my photos (e.g. these) in the last millennium using this date-based naming convention: YYYY_MM_DD_topical-text_NNN.jpg (where the NNNs are just sequential numbers and the file type suffix could be .jpg, .arw, .cr2, .png or whatever. Same for folder titles.) So, because I don’t want a new title for every day I do this, I’m adopting the same convention, at least for now.

Not fast enough

In The End of Advertising, Michael Mignano says (in the subhead, and beyond), The business model that funded the internet is going away, and the open web will never be the same. He says AI is already killing it, by giving us answers to everything, and performing other handy tasks, without advertising to distract or annoy us. He also says AI services will attempt to invent ads, but that’s a losing proposition, mostly because it won’t work and we’ll hate it, but also because “content wants to be free.” (I submit that no art forms, ever, wanted to be called “content.”) I agree. I also agree that “Premium content will become even more premium.” He concludes, “the relationship between us and publishers will become much more transactional and direct. And we will feel it. Over time, it’ll be a new internet, and the open web will be a memory. Great content will still find a way to reach us, just like it always has. But we’ll look back on the first few decades of the internet as the golden age of content, when everything felt free.” Well, you’re reading some premium content right now, and it’s free. Thanks to what I do here, I can make money in other ways. We call those because effects.

Podcasts, Wallcasts, and Paycasts

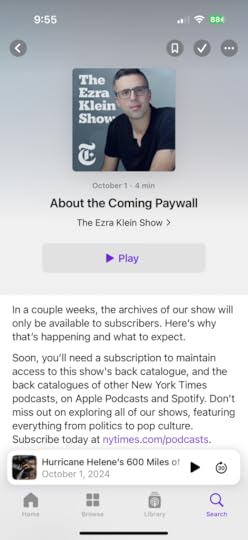

The Ezra Klein Show, as it appeared on my podcast app this morning. It is now a wallcast.

The Ezra Klein Show, as it appeared on my podcast app this morning. It is now a wallcast.Would a blog be a blog if it went behind a paywall, or if you needed a subscription to read it?

Of course not. Blogs are on the open Web, and tend to stay there so long as they don’t move away from their original location.

Same should go for podcasts. “Wherever you get your podcasts” certifies the open nature of podcasting.

But now the New York Times is putting Ezra Klein’s podcast archives behind a paywall.

Never mind how icky this is on several grounds. Our challenge now is classification. We need a new noun for restricted ‘casts such as Ezra’s. I suggest wallcasts.

For subscription-only ‘casts, such as some on SiriusXM*, I suggest paycasts.

Bottom line: It can’t be a podcast if you have to pay for any of it, including archives.

By the way, it won’t matter if a Times subscription opens wallcast archives, as it does for print. By putting their podcast archives behind a paywall, the Times is changing the DNA of those casts. A wallcast is not a podcast. Full stop.

Spread the words.

*SiriusXM’s paycasts include “SmartLess,” “Freakonomics Radio,” “The Joel Osteen Podcast,” “Last Podcast on the Left,” and “Andy Cohen’s Daddy Diaries.” They require a subscription to SiriusXM or its Podcasts+ service. Some, such as “Marvel’s Wastelanders” and “Marvel/Method also require a subscription. I’m not sure what kind. (FWIW, I’ve been a SiriusXM subscriber since 2005, but only listen to live subscription streams. I’ve never listened to any of its podcasts.) SiriusXM does have some shows in podcast form, however. Examples are “The Megyn Kelly Show,” “Best Friends with Nicole Byer and Sasheer Zamata,” and “Chasing Life with Dr. Sanjay Gupta.” I believe it also has some wallcasts. For example, “SmartLess” episodes are on the open Web, but early access and bonus episodes are behind a paywall. Or so it seems to me in the here and now. I invite corrections.

September 30, 2024

When Radio Delivers

For live reports on recovery from recent Hurricane Helene flooding, your best sources are Blue Ridge Public Radio (WCQS/88.1) and iHeart (WWNC/570 and others above, all carrying the same feed). Three FM signals come from the towers on High Top Mountain, which overlooks Asheville from the west side: 1) WCQS, 2) a translator on 102.1 for WNCW/88.7, and 3) a translator on 97.7 for WKSF/99.9’s HD-2 stream. At this writing, WCQS (of Blue Ridge Public Radio) and the iHeart stations (including WKSF, called Kiss Country) are running almost continuous public service coverage toward rescue and recovery. Hats off to them.

For live reports on recovery from recent Hurricane Helene flooding, your best sources are Blue Ridge Public Radio (WCQS/88.1) and iHeart (WWNC/570 and others above, all carrying the same feed). Three FM signals come from the towers on High Top Mountain, which overlooks Asheville from the west side: 1) WCQS, 2) a translator on 102.1 for WNCW/88.7, and 3) a translator on 97.7 for WKSF/99.9’s HD-2 stream. At this writing, WCQS (of Blue Ridge Public Radio) and the iHeart stations (including WKSF, called Kiss Country) are running almost continuous public service coverage toward rescue and recovery. Hats off to them.Helene was Western North Carolina‘s Katrina—especially for the counties surrounding Asheville: Buncombe, Mitchell, Henderson, McDowell, Rutherford, Haywood, Yancey, Burke, and some adjacent ones in North Carolina and Tennessee. As with Katrina, the issue wasn’t wind. It was flooding, especially along creeks and rivers. Most notably destructive was the French Broad River, which runs through Asheville. Hundreds of people are among the missing. Countless roads, including interstate and other major highways, are out. Communities have been washed away.

For following what’s happening there, I highly recommend listening to Blue Ridge Public Radio (WCQS/88.1) and any of the local iHeart stations (listed the image above). All of them are carrying the same continuous live coverage, which is excellent. (I’m listening right now to the WWNC/570 stream.)

Of course, there’s lots of information on social media (e.g. BlueSky, Xitter, Threads), but if you want live coverage, radio still does the job. Yes, you need special non-phone equipment to get it when the cell system doesn’t work, but a lot of us still have those things. Enjoy the medium while we still have it.

Item: WWNC just reported that WART/95.5 FM in Marshall, with its studios in a train caboose by the river, is gone (perhaps along with much of the town).

More sources:

WISE/1310 streamWTMT/105.9 streamThis is cross-posted on Trunkli, my blog on infrastructure.

Post flow

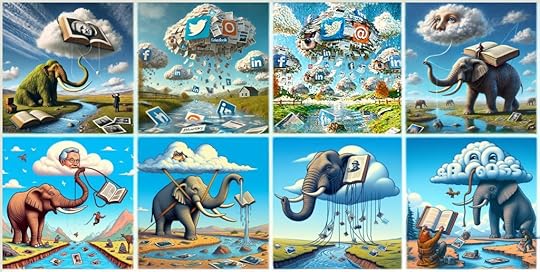

These are eight (among many other) failed attempts to get ChatGPT and Copilot to create an image of posts in X (née Twitter), Linkedin, Facebook, Threads, BlueSky, Mastodon, and Instagram to flow or rain down from their clouds into a river of blogs.

These are eight (among many other) failed attempts to get ChatGPT and Copilot to create an image of posts in X (née Twitter), Linkedin, Facebook, Threads, BlueSky, Mastodon, and Instagram to flow or rain down from their clouds into a river of blogs.A watershed* is land that drains through a river to the sea or into an inland body of water. That’s what came to mind for me when I read this from Dave Winer:

If you want to help the open web, when you write something you’re proud of on a social web site like Bluesky or Mastodon, also post it to your blog. Not a huge deal but every little bit helps.#

I love the idea of using one’s blog (as Dave does) as the personal place to collect what one posts on various social media. So the flow, which we might call a postshed (would post shed be better because it’s easier to read?) is from social media clouds into one’s own river of blog posts. (Maybe postflow would be better. I invite better nouns and/or verbs.)

So I’ll try doing some of that flow today. Here goes:

On X I pointed to Death as a Feature, which was my response six years ago to Elon Musk’s Martian ambitions. This was in response Doge Designer tweeting “Elon Musk is projected to become world’s first trillionaire. He said ‘My plan is to use the money to get humanity to Mars & preserve the light of consciousness,” to which Elon’s reply was, “That’s the goal.”

On Threads (and perhaps on other federated media, if that works): Besides Blue Ridge Public Radio bpr.org (which is great) what else should we tune in to hear what’s happening in the flooded parts of Western North Carolina? The best answer is any iHeart station in the region, over the air or on the iHeart app. I’m listening right now to WWNC/570.

On Facebook: Due to popular request (by one person, but not the first), I’ve put a pile of headshots up here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/docsearls/albums/72177720312529167/

Also on Facebook, While I was never a fan of his teams (I swang with the Mets), I loved watching Pete Rose play baseball. He was truly great. RIP, Charlie Hustle. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/30/sports/baseball/pete-rose-baseball-star-who-earned-glory-and-shame-dies-at-83.html

*Wikipedia calls watersheds “drainage basins.” Not appetizing.

September 24, 2024

Open-Source Journalism

Fourteenth in the News Commons series.

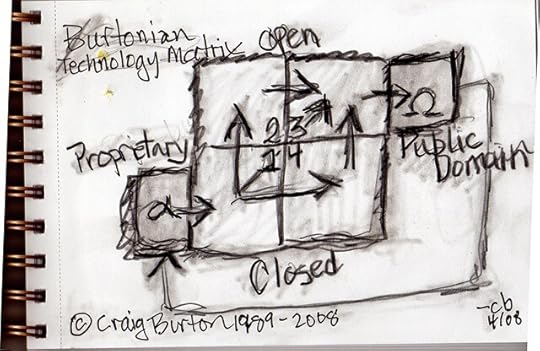

Craig Burton’s view of the open source ecosystem.

Craig Burton’s view of the open source ecosystem.The main work of journalism is producing stories.

Questions following that statement might begin with prepositions: on what, of what, about what. But the preposition that matters most is with what.

Ideally, that would be with facts. Of course, facts aren’t always available in the pure form that researchers call data. Instead, we typically have reports, accounts, sightings, observations, memories, and other fuzzy coatings or substitutes for facts.

Craig Burton used to say that he discounted first-hand reports by 50% and withheld trust in second- and third-hand reports completely. In some cases, he didn’t even trust his memory, because he knew (and loved) everyone’s fallibility, including his own.

But still, we need facts, in whatever form. And those come from what we call sources. Those can be anybody or anything.

Let’s look at anything, and into the subset in archives that are not going away.

How much of that is produced by news organizations? And how much of what’s archived is just what is published?

I ask for two reasons.

One is because in this series I have made a strong case, over and over, for archiving everything possible that might be relevant in future news reporting and scholarship.

The other is because I have piles of unpublished source material that informed my writing in Linux Journal. This material is in the following forms:

Text files on this laptop and on various connected and disconnected drivesSound recordings on—Cassette tapesMicrocassette tapesSony MiniDisc disks.mp3, ogg, and other digital files, mostly on external drivesVideo recordings on—Hi-8 tapesMini-DV tapesAnd I’m not sure what to do with them. Yet.

Open-sourcing them will take a lot of time and work. But they cover the 24 years I wrote for Linux Journal, and matter to the history of Linux and the open source movement (or movements, since there were many, including the original free software movement).

Suggestions welcome.

On Intelligence

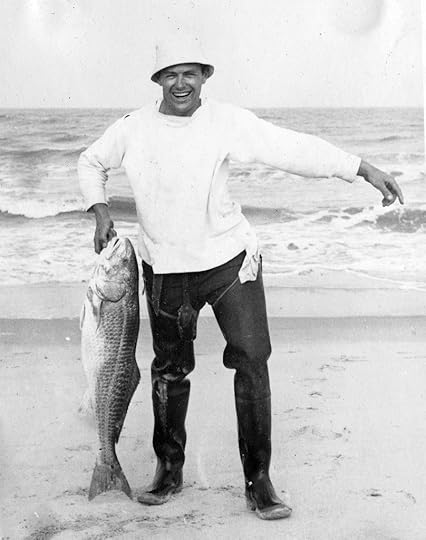

My father, Allen H. Searls, scored 159 on an Army IQ test when he re-enlisted to fight in WWII. But that didn’t make him a great fisherman, even though he loved to do it (and scored big with that striped bass, one of the few he ever caught.) Nor did it make him a good speller. (He was awful.) Or a good student. At fifteen he dropped out of high school and went to work as a longshoreman in New York City, commuting to work from New Jersey on a ferry, and then later working high steel construction on the bridge that obsolesced that ferry. But he was a great card player (almost always winning at poker), a math whiz, brilliant at making tools in his shop, and outstanding in many other ways (friend, husband, father) that can’t and shouldn’t be measured. Except maybe his looks. The guy was a 10.

My father, Allen H. Searls, scored 159 on an Army IQ test when he re-enlisted to fight in WWII. But that didn’t make him a great fisherman, even though he loved to do it (and scored big with that striped bass, one of the few he ever caught.) Nor did it make him a good speller. (He was awful.) Or a good student. At fifteen he dropped out of high school and went to work as a longshoreman in New York City, commuting to work from New Jersey on a ferry, and then later working high steel construction on the bridge that obsolesced that ferry. But he was a great card player (almost always winning at poker), a math whiz, brilliant at making tools in his shop, and outstanding in many other ways (friend, husband, father) that can’t and shouldn’t be measured. Except maybe his looks. The guy was a 10.Now that AI is a huge thing, it’s worth visiting what intelligence is, and how we mismeasure it—for example, by trying to measure it at all.

I’ve been on this case for a while now, mostly by answering questions ab0ut IQ on Quora. My answer with the most upvotes is this one, to the question “What is considered a good IQ?” Here is the full text:

What makes an IQ score “good” is the advantage it brings. That’s it.

When I read the IQ questions here in Quora — “How high an IQ do I need to have to become a good hacker?” “Is 128 a good IQ for a nine year old?” — my heart sinks.

IQ tests insult the intelligence of everybody who takes them, by reducing one of the most personal, varied and human qualities to a single number. Worse, they do this most typically with children, often with terrible results.

It is essential to remember that nobody has “an IQ.” Intelligence cannot be measured as if by a ruler, a thermometer or a dipstick. It is not a “quotient.” IQ test scores are nothing more than a number derived from correct answers to puzzle questions on a given day and setting. That’s it.

Yet our culture puts great store in IQ testing, and many actually believe that one’s “IQ” is as easily measured and unchanging as a fingerprint. This is highly misleading and terribly wrong. I speak from ample experience at living with the results of it.

I grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, going a public school system that sorted kids in each grade by a combination of IQ test scores, achievement test scores and teacher judgement. (My mother taught in the same system, so she knew a lot about how it worked, plus the IQ scores of my sister and myself.) After testing well in kindergarten, I was put in the smart kids class, where I stayed through 6th grade, even though my IQ and achievement test scores fell along with my grades, which were worse every year.

In 6th grade the teacher insisted that I was too dumb for his class and should be sent to another one. My parents had me IQ-tested by an independent center that said I was still smart, so I stayed. By 8th grade, however, my IQ score, grades and achievement test scores were so low that the school re-classified me from the “academic” to the “general” track, and shunted me toward the region’s “vocational-technical” high school to learn a “trade” such as carpentry or auto mechanics. I was no longer, as they put it, “college material.”

So my parents decided to take me out of the public school system and send me to a private school. All the ones we visited used IQ tests in their admissions process. I did so poorly at the school I most wanted to attend (because a girl I had a crush on was already headed there) that the school told my parents I was downright stupid, and that it was cruel of them to have high expectations of me. At another school they forgot to time the test, which gave me a chance to carefully answer the questions. I got all of them right. Impressed by my score, the admissions director told my parents they were lucky to have a kid like me. But the school was itself failing, so my parents kept looking.

The school that ended up taking me was short on students, so my IQ score there (which I never learned) wasn’t a factor. I got bad grades and test scores there too, including the SAT. Luckily, I ended up going to a good small private college that took me because it needed out-of-state students and I was willing to commit to an early decision. I did poorly there until my junior year, when I finally developed skilled ways of working with the system.

Since college I’ve done well in a variety of occupations, and in all of them I’ve been grateful to have been judged by my work rather than by standardized tests.

Looking back on this saga, I was lucky to have parents who respected my intelligence without regard for what schools and test scores told them. Other kids weren’t so lucky, getting categorized in ways that shut off paths to happy futures, violating their nature as unique individuals whose true essence cannot be measured. To the degree IQ tests are still used, the violation continues, especially for kids not advantaged by scoring at the right end of the bell curve.

John Taylor Gatto says a teacher’s main purpose is not to add information to a kid’s empty head (the base assumption behind most formal schooling, ) but to subtract everything that “prevents a child’s inherent genius from gathering itself.”

All of us have inherent genius. My advice is to respect that, and quit thinking IQ testing is anything but a way of sorting people into groups for the convenience of a system that manufactures outputs for its own purposes, often at great human cost.

Here is Walt Whitman on inherent genius:

It is time to explain myself. Let us stand up.

I am an acme of things accomplished,

and I an encloser of things to be.

Rise after rise bow the phantoms behind me.

Afar down I see the huge first Nothing,

the vapor from the nostrils of death.

I know I was even there.

I waited unseen and always.

And slept while God carried me

through the lethargic mist.

And took my time.

Long I was hugged close. Long and long.

Infinite have been the preparations for me.

Faithful and friendly the arms that have helped me.

Cycles ferried my cradle, rowing and rowing

like cheerful boatmen;

For room to me stars kept aside in their own rings.

They sent influences to look after what was to hold me.

Before I was born out of my mother

generations guided me.

My embryo has never been torpid.

Nothing could overlay it.

For it the nebula cohered to an orb.

The long slow strata piled to rest it on.

Vast vegetables gave it substance.

Monstrous saurids transported it in their mouths

and deposited it with care.

All forces have been steadily employed

to complete and delight me.

Now I stand on this spot with my soul.

I know that I have the best of time and space.

And that I was never measured, and never will be measured.

Back to Gatto. Here is the full context of that pull-quote on genius. It’s from Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling:

Over the past thirty years, I’ve used my classes as a laboratory where I could learn a broader range of what human possibility is — the whole catalogue of hopes and fears — and also as a place where I could study what releases and what inhibits human power.

During that time, I’ve come to believe that genius is an exceedingly common human quality, probably natural to most of us. I didn’t want to accept that notion — far from it: my own training in two elite universities taught me that intelligence and talent distributed themselves economically over a bell curve and that human destiny, because of those mathematical, seemingly irrefutable scientific facts, was as rigorously determined as John Calvin contended.

The trouble was that the unlikeliest kids kept demonstrating to me at random moments so many of the hallmarks of human excellence — insight, wisdom, justice, resourcefulness, courage, originality — that I became confused. They didn’t do this often enough to make my teaching easy, but they did it often enough that I began to wonder, reluctantly, whether it was possible that being in school itself was what was dumbing them down. Was it possible I had been hired not to enlarge children’s power, but to diminish it? That seemed crazy on the face of it, but slowly I began to realize that the bells and the confinement, the crazy sequences, the age-segregation, the lack of privacy, the constant surveillance, and all the rest of the national curriculum of schooling were designed exactly as if someone had set out to prevent children from learning how to think and act, to coax them into addiction and dependent behavior.

Bit by bit I began to devise guerrilla exercises to allow as many of the kids I taught as possible the raw material people have always used to educate themselves: privacy, choice, freedom from surveillance, and as broad a range of situations and human associations as my limited power and resources could manage. In simpler terms, I tried to maneuver them into positions where they would have a chance to be their own teachers and to make themselves the major text of their own education.

In theoretical, metaphorical terms, the idea I began to explore was this one: that teaching is nothing like the art of painting, where, by the addition of material to a surface, an image is synthetically produced, but more like the art of sculpture, where, by the subtraction of material, an image already locked in the stone is enabled to emerge. It is a crucial distinction.

In other words, I dropped the idea that I was an expert whose job it was to fill the little heads with my expertise, and began to explore how I could remove those obstacles that prevented the inherent genius of children from gathering itself. I no longer felt comfortable defining my work as bestowing wisdom on a struggling classroom audience. Although I continue to this day in those futile assays because of the nature of institutional teaching, wherever possible I have broken with teaching tradition and sent kids down their separate paths to their own private truths.

The italics are mine.

Knowing that we have industrialized education should help us understand how un-human AI “training,” “learning,” and “knowledge” actually are. (Side note: I love AI and use it every day. I also don’t think it’s going to kill us. But this post isn’t about that.)

Start with the simple fact that institutional teaching and its traditions don’t work for lots of kids. Today’s system is better in some ways than the one Gatto bested. then quit, but it’s still a system. If I were a child in the system we have today, I would surely be classified as an ADHD and ALD case,* given drugs, and put in a special class for the otherwise unteachable.

What worked for me as a student was one kind statement from one teacher: , who taught English in my junior year. One day he said to me, “You’re a good writer.” It was as if the heavens opened. That was the first compliment I had ever received from any teacher, ever, through twelve years of schooling. I wish he were still alive, so I could thank him.

Fortunately, I can thank my high school roommate, Paul Marshall, who was (and still is) a brilliant writer, musician, preacher—and exceptionally funny. He was voted Class Wit (among other distinctions, which he declined, preferring the Wit one), and as a senior he substitute-taught biology to sophomores when their teacher was out sick. (These days he is the retired Episcopal Bishop of Bethlehem Pennsylvania. Before that, he was a professor at Yale Divinity School. There’s more at both those links.)

I remember a day when a bunch of us were hanging in our dorm room, talking about SAT scores. Mine was the lowest of the bunch. (If you must know, the total was 1001: a 482 in verbal and a 519 in math. Those numbers will remain burned in my brain until I die.) Others, including Paul, had scores that verged on perfection—or so I recall. (Whatever, they were all better than mine.). But Paul defended me from potential accusations of relative stupidity by saying this: “But David has insight.” (I wasn’t Doc yet.) Then he gave examples, which I’ve forgotten. By saying I had insight, Paul kindly and forever removed another obstacle from my path forward in life. From that moment on, insight became my stock in trade. Is it measurable? Thankfully, no.

Okay, back to AI.

As Don Norman told us in his salon here at Indiana University,

First, these machines are not intelligent. Second, remember the A in AI. A means artificial. They don’t work the way we do. And it’s a mistake to think they do. So let’s take a look at what they are. They are pattern-matchers.

I could let Don go on (which you can, at that last link), but there are a zillion explanations of what AI is and does, which you’ll find everywhere on the Web, and in answers from questions you can ask ChatGPT, CoPilot, Anthropic, Perplexity, Claude, and the rest of them. And all of them will be full of metaphorical misdirection. (Which Don avoids, being the linguist that he is.)

We may say an AI is “trained,” that it “learns,” “knows” stuff, and is “smart” because it can beat the most skilled players of chess and go. But none of those metaphors are correct, even though they make sense to us. Still, we can’t help using those metaphors, because we understand everything metaphorically. (To digress into why, go here. Or dig into George Lakoff‘s work, starting here. A summary statement might be, all metaphors are wrong, and that’s why they work. )

To be human is to be different from every other human, by design. We all look and sound different so we can tell each other apart. We also differ from how we were ten minutes ago, because we learn constantly.

So, to be human is to diverge in many ways from norms. Yet, being pattern recognizers and given to organizing our collective selves into institutional systems, we tend to isolate and stigmatize those who are, as we now say, divergent. Constantly recognizing patterns and profiling everything we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch is not just one of the many ways we are all human, but also how we build functioning societies, prejudices included. (As a side note, I am sure the human diaspora was caused both by our species’ natural wanderlust and by othering those who were not like us. We would fight those others, or just migrate away from them until we filled the world. Welcome to now.)

To sum this all up, just remember that when we talk about intelligence, we are talking about a human quality, not a quantity of anything. That machines test out better at pattern recognition than we do does not make them intelligent in a human sense. It just makes them more useful in ways that appear human but are not.

So have all the fun you want with AI. Just remember its first name.

*In my forties and at my wife’s urging (because my ability to listen well and follow directions was sub-optimal), I spent whole days being tested for all kinds of what we now call neurodivergent conditions. The labels I came away with were highly qualified variants of ADHD and APD. Specifics:

I was easily distracted and had trouble listening to and sorting out instructions for anything. (I still have trouble listening to the end of a long joke.)On puzzle-solving questions, I was very good.My smarts with spacial and sequence puzzles were tops, as was my ability to see and draw patterns, even when asked to rotate them 90° or 180°.My memory was good.I had “synchronization issues,” such as an inability to sing and play drums at the same time. This also involved deficiencies around “cognitive overload,” “context switching,” multitasking, coping with interruptions, and “bottlenecks” in response selection. They also said I had become skilled at masking all those problems, to myself and others.I could easily grasp math concepts but made many mistakes with ordinary four-function calculations.I did much better at hearing and reading long words than short ones, and I did better reading wide columns of text than narrow ones.When made to read out loud a simple story comprised of short and widely spaced words in a narrow column, I stumbled through it all and remembered little of the story afterward. They told me that if I had been given this test alone, they would have said I had trouble reading at a first-grade level and I would have been called (as they said in those days) mentally retarded.My performance on many tests suggested dyslexia, but my spelling was perfect and I wasn’t fooled by misplaced or switched letters in words. They also said that I had mostly self-corrected for some of my innate deficiencies, such as dyslexia. (I remember working very hard to become a good speller in the fourth grade, just as a challenge to myself.)They said I did lots of “gestalt substitution,” when reading out loud, for example replacing “feature” with “function,” assuming I had read the latter when in fact I’d read the former.Unlike other ADHD cases, I was also not more impulsive, poorly socialized, or easily addicted to stuff than normal people.Like some ADHD types, I could hyperfocus at times.My ability to self-regulate wasn’t great, it also wasn’t bad. Just a bit below average. (So perhaps today they’d call me ADHD-PI, a label I just found in Wikipedia).The APD (auditory processing disorder) diagnosis came mostly from hearing tests. But, as with ADHD, I only hit some of the checkboxes. (Specifically, about half of the ten symptoms listed here.)My ability to understand what people say in noisy settings was in the bottom 2%. And that was when my hearing was still good.I also apologize for the length of this post. If I had more time, I would have made it shorter.

Which, being a blog post, I will. Meanwhile, thanks for staying (or jumping) to the end.

September 16, 2024

Remembering Iris Harrelson

In the late ’70s, I worked for a while at the Psychical Research Foundation, which then occupied a couple of houses on Duke University property and did scientific research into the possibility of life after death. My time there was a lever that has lifted my life on Earth ever since, including many deep and enduring friendships.

The PRF also involved many fascinating characters. One was Iris, a brilliant woman from Savannah with a strong personality, dyed red hair, and lots of talents. Her surname was pronounced “Mock,” but spelled with an “a” or two. She also mentioned occasionally that her brother was Ken “Hawk” Harrelson, the baseball player I remember most from his peak years with the Boston Red Sox, but who for many years has been the play-by-play announcer for the Chicago White Sox. Now 83, he is still calling games for what will almost certainly be the losing-ist team in major league history.

So this morning, after I read “Hawk Harrelson spent 3 decades calling the White Sox. Now he can’t stand to watch” in the NY Times (sorry, paywall), I looked up “Hawk Harrelson” plus “sister” and “Iris” and landed on this 2018 page, which has this passage from Hawk’s autobiography:

“My sister was a heavy smoker who had died of lung cancer when she was only 40. I was so proud of what Iris had done with her life after such a tough start, having to get married at the age of 14. She wrote a few books and became a gourmet cook. She also learned to speak fluent German, Russian, and Spanish. She lectured at Duke University and at the University of Toronto. She became an accomplished pianist. She also dabbled in acting and landed a few holes on stage in New York. And she was an interior designer, having turned my penthouse pad into a beautiful home.“But we had a falling out several years before she died when I turned down her request to borrow $250,000. She had wanted to open a nightclub in downtown Savannah and I didn’t have that much cash at the time. Plus, I didn’t think her business idea was a good one. When I refused her request, she walked out the door and I never saw her again.“Apparently, she never quit smoking.”While I’m not surprised to learn that Iris is gone (she was older than me, and I’m seventy-seven), it’s a shock to hear that she died so young, so long ago, and so full of talent and promise.I’m also not surprised that there is almost zero information about her on the Web. But then, the Web was born long after she died, and is something of a whiteboard as well. So maybe this post (titled with her birth name) will at least help the world not completely forget one of its especially interesting and talented human beings.

September 11, 2024

On Journalism and Principles

Thirteenth in the News Commons series.

I grabbed the spottedhawk.org domain after hearing Garrison Keilor read this passage from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself over Leo Kottke improvising on guitar:

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me.

He complains of my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed. I too am untranslatable.

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

Most of what I do is in deficient obedience to Whitman’s spotted hawk. Including this blog.

Early in this millennium, when it was as easy to blog as it later was to tweet, I blogged constantly. The stretch from 1999 to 2007 was blogging’s golden age, though we didn’t know it at the time. (My blog from that time is archived at weblog.searls.com.) My blog then was a daily journal, and in a literal way that made me even more of the journalist I had always been.

On that career side, I was also employed for all that time by Linux Journal. My name was on its masthead for twenty-four years, from 1996 to 2019. When LJ was sold at the end of that stretch, I left as editor-in-chief. After that, I was the host of FLOSS Weekly on the TWiT network. Both were paid gigs, and when the FLOSS Weekly gig ended last December, so did my long career in journalism.

And maybe that happened just in time, because journalism has since then acquired a taint. In this past weekend’s Cornerstone of Democracy newsletter, Dan Gillmor sources Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo on the topic:

I guess I would say that as journalists our core mission is fundamental honesty with readers. That means always telling readers the truth, an accurate story as nearly as we are able to uncover it and understand it, as well as being transparent with the values, commitments and core beliefs we bring to the work we do. We believe in always being fair to everyone and everything we write about. Fairness is really only another permutation of accuracy. Balance is a construct applied after the fact that is often as not at odds with accuracy. A belief in democratic republicanism or civic democracy has always been at the core of what we do. It’s central to what stories we choose to focus on, it’s a value structure that permeates our organizational approach to what we do. I can’t speak for everyone at TPM. But as founder and still a guiding light, I think our understanding of what journalism is or should be is inextricably connected with democratic republicanism/civic democracy. I don’t think I would say we’re activists for democracy. But to me being on the side of civic democracy is inextricably connected to what we do and who we are. We’re on the side of civic democracy as much as we’re on the side of journalism.

I don’t want to label other journalists. But to the extent many other journalists don’t operate in this way, or understand their job this way, it’s because they work for publications whose business models simply aren’t compatible with this approach to journalism. What we now commonly call “both-sidesism” is rooted in the business structure of most contemporary journalism, specifically the need to have purchase across of wide ideological spectrum of the population.This is especially so in large corporate journalism because the need for scale and advertiser buy-in really requires that access to all parts or most parts of the political spectrum. In a hyperpolarized political culture when one side veers off the democratic rail that inevitably pulls a lot of that kind of journalism with it. I see that as fundamentally a structural reality. This goes back many decades, long before the current moment. It was more workable in a different political climate. But in this one that’s how it works. Journalists think they’re following core journalistic principles. But it’s driven really by business models.

That’s why now I just call myself a writer. Or a photographer.† Unless it’s to write a book (which typically pays little or nothing), to be a paid journalist today requires frequent or constant production of “content.” But I’d rather yawp, like I am now, here, or over at ProjectVRM, TrunkLine (a blog on infrastructure), or Customer Commons (which will in the next year become more important than everything else I’m doing).

All three of those involve work, but don’t pay. Same goes for serving as Chief Intention Officer of Kwaai.ai, a commuity of 600+ volunteers working on personal AI. (Check it out. Good stuff going on there.)

But before I give up on the journalist label, let’s ask Perplexity.ai* to answer What is the purpose of journalism? Here’s the answer I just got:

Based on the search results, the primary purpose of journalism can be summarized as follows:

To provide citizens with accurate and reliable information they need to function in a free society. This is considered the central purpose of journalism.To inform the public about current events, issues, and developments happening in their communities and around the world.To serve as an independent monitor of power and act as a watchdog over those in positions of authority.To provide a forum for public criticism, debate, and compromise on important issues.To convey context and help citizens understand the significance of events.To set the tone for public discourse and help define community goals and values.To empower citizens to make informed decisions about their lives and society.To facilitate democratic processes by educating voters and inspiring civic engagement.To support commerce by creating awareness about products and services.To drive cultural transformation by connecting people to communities and ideas beyond their immediate surroundings.Journalism is considered essential because it helps citizens navigate their lives, make important decisions, and participate effectively in democratic societies. It serves as a crucial source of verified information in an increasingly complex world, helping to separate fact from fiction and provide context to current events.

Is that what journalists are doing today? Was it ever? Really? All of it?

I don’t know. Mostly journalists write stories. If you’ve read Where Journalism Fails, or Stories vs. Facts, you know I think the story-telling imperative has its own problems.

Back in the early ’90s, when I was doing PR for a hot Silicon Valley startup, I asked a top reporter at one of the tech magazines why he didn’t want to see my client’s brilliant and charismatic marketing director. The reporter said, “He abuses the principle of instrumentality.” When I pressed the reporter to expand on that, he explained that everyone involved knows that reporters are used as instruments by whoever spins them. The “principle of instrumentality” is about knowing, and trying to ignore, the simple fact that journalism is instrumented in many ways. While Josh Marshall talks above about the instrumenting of journalism by business models, in this reporter’s case, it was by the persuasive charisma of a strong personality who wanted positive coverage.

I realized then that I wasn’t being hired at the same magazine, or at any publication before Linux Journal (and I pitched many) was that I didn’t want to be an instrument. More specifically, they all wanted me to write about what I called “vendor sports.” “Apple vs. Microsoft,” for example. I wanted to write about interesting stuff without favor to anybody or anything other than what seemed right, important, fun, or just interesting. Vendor sports wasn’t it for me. Nor was any of the other usual stuff. Linux was a cause, however, so I worked to make my Linux Journal writing as non-evangelical as possible, though I did get credited with helping put both Linux and open source on the map.

Was I a journalist while working as an editor there? I suppose so, given that my work hit at least some of the ten items above. At least I thought of myself that way.

A difference today is that we are all both digital and physical beings. Here in the digital world (where I am now), anybody can publish anything, on many different platforms, including their own if they’re geeky enough to make that work. According to the Podcast Index, there are 4,262,711 podcasts right now. Instagram has over two billion users. Says here there are over three billion blog posts published every year, and over six hundred million active bloggers. (I suppose I am three of them.) The same piece says “Over 90% of blog posts receive zero traffic.” Many of those blogs are faked-up, of course, but it’s still clear that the world of online publishing is a red ocean, while Mastodon, Threads, Bluesky, Nostr, and the like are more like small rivers or bays than one blue ocean. (Links in that last sentence go to my tiny presence in each. I’m also still on Xitter and Linkedin, for what those are worth.)

So now I’m thinking about what principles, old and new, work in the digital media environment and not so much in the old analog one.

Here’s one: We’re past the era of “What’s on.”** Unless it’s a live sport or some other kind of scheduled must-see or must-hear event, you can catch it later, on your own time.

Here’s another: We don’t have to fill time and space with a sum of “content.” Really, we don’t. Yes, it helps to have a schedule and be predictable. But it’s not necessary. Especially if you’re being paid little or nothing.

Here’s another: The challenge now is building and maintaining an archive of facts, and not just of stories. I’ve written about this elsewhere in this series. Go look it up.

Another: Try to grab as many of those facts as you can before and after they turn into stories or don’t. This is what calendars are for. Even if nothing comes out of a meeting or an event that appears on a calendar, it’s good to know that something happened. And to archive that as well.

I also believe both of those principles are easiest to apply in local contexts, simply because there is a relatively finite sum of facts to work with locally, and facts still matter there. (Scott Adams tells us they don’t in the wider world. And he has a case.)

This is one reason I’m embedded in Bloomington, Indiana. We’re working on all that stuff here.

† My photos here and here on Flickr have about twenty millon views so far. The last peak was five thousand on Sunday. The top attraction that day was this shot of Chicago I got on a cross-country flight between Phoenix and Boston in 2011. That one photo has logged 26,159 views so far. All my photographs are CC-licensed and free to use, which is why over 4,000 of them are in Wikimedia Commons, a library of images used in Wikipedia. So thousands of those (it’s hard to tell exactly how many) end up in Wikipedia. Many more accompanying news stories, such as this one from Lawrence, Mass, this one from a power plant, this one from a lithium mine, and all these from Chicago. And I put none of them in either Wikimedia Commons or Wikipedia. Other people do that. I just put the photos out there. Meanwhile, this blog maxed at a little over 300 views one day last week, but usually gets a dozen or so. My old blog ran at about five thousand a day, and sometimes ten times that many. To bring this back to a theme of this post, while I do a lot of photography, I don’t think of myself as a photographer. I take pictures. And I write. And I talk some. All for the same purpose: to be useful, and to make stuff happen. Good stuff, hopefully.

By the way, the bird at the top is a juvenile red-tailed hawk. There is no one species called a spotted hawk, so this one will have to do. I shot this bird a couple of months ago, perched on a 480-volt line in the alley behind our house in Bloomington, Indiana. I was looking to hear a barbaric yawp, but he, or she, failed me on that one.

*I first asked ChatGPT 4o and got a cliché’d answer with no sources. Perplexity gave me a longer answer, just as cliché’d, but with eight sources. For fun, go ask both and see what you get. Try Claude and Gemini too. No two will be the same. Some will be better, some worse.

**I’ve written about this, but haven’t published it yet. Stay tuned.

August 25, 2024

The Organ Builder

In The Soul’s Code, James Hillman says each of us is born with as much of a destiny, calling, mission, or fate, as an acorn has within it an oak tree. He also says “Reading life backward enables you to see how early obsessions are the sketchy preformation of behaviors now… Reading backward means that growth is less the key biographical term than form, and that development only makes sense when it reveals a facet of the original image.”

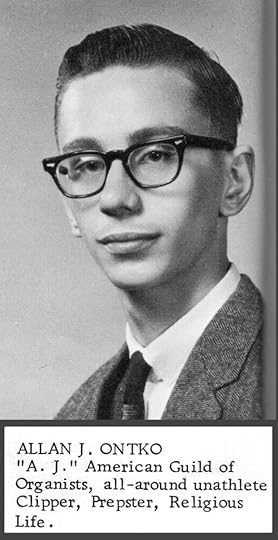

The original image on the right is the high school yearbook picture of Allan John Ontko, one of my best friends during the three years we were classmates at what I half-jokingly call a Lutheran academic correctional institution. Because that’s what it was for me. For most of the boys there, however, it was a seminary. Allan, then known to all as A.J., was one of the seminarians. He was also completely obsessed with pipe organ music and production.

At the time that picture was taken, in May 1965, A.J. was seventeen, a senior about to graduate, and the builder of his a pipe organ in his parents’ basement. The main parts of the organ were so large that a cinder-block wall needed to be removed so the thing could be extracted. It was also hand-built and tested, with thousands of drilled holes, thick webworks of wiring, and solder joints. All the pipes, stops, keyboards, and foot pedals were scavenged or bought used. I went with him on some of his trips around New Jersey and New York to obtain pipe organ parts. His determination toward completing the project was absolute. Just as amazing was that he did this work on weekends, since ours was a boarding school in Westchester, New York, and his home was more than an hour’s drive away in New Jersey. His parents’ patience and moral support seemed infinite.

A.J. sold the organ to some church. That was the first step on his main path in life. Look up Ontko pipe organ and you’ll find plenty of links to his work on the Web. One of his companies, Ontko & Young, has fifteen listed organs in the the Pipe Organ Database. His website, ontkopipeorgans.com, is partially preserved in the Internet Archive. Here’s one snapshot.

After high school, Allan (no longer A.J.) went to Westminster Choir College. In that time he continued building pipe organs, advancing his skills as an organist, and singing as well, I suppose. Both of us sang bass, though he could hold a tune while I could not. He had many amusing reports of his choir’s collaborations with the New York Philharmonic, and did a brilliant impression of Leonard Bernstein’s conducting style. Allan could be very funny. I recall a list of fake organ stops that he and another organist friend (who I am sure is reading this) created for a fake pipe organ design worthy of National Lampoon or The Onion. (Some stops were named after teachers. The only one I recall is the Roschkeflöte, named after Rev. Walter Roschke, who taught church history.)

After that, we were only in occasional contact. I know he married twice. I met his first wife when he still lived in New Jersey. That was soon after college. Later he divorced, moved to Charleston, South Carolina and remarried. Most of what I know about this period was that the organ-building continued, along with work composing and playing music.

A surprise came in 2011, when I got a friend request on Facebook from Olivia Margaret Ontko. I assumed that this must be a relative of Allan’s, since he came from a large Slovak family in New Jersey. When I went to Olivia’s website, I thought for a moment that looks kind of like Allan but… then realized this was Allen. He was a woman now.

I accepted the request, and marveled at how well Olivia had gathered a large collection of very supportive friends, and had become an active advocate for trans rights and acceptance of gender choices. And so, for the next few years, we would occasionally comment on each others’ posts, and talk now and then on the phone. Olivia also created a Linkedin account which is still there.

Our longest conversation was in June 2015, while I was driving to the 50th reunion of our high school class, and reporting on it afterwards. Olivia was in Charleston and said she couldn’t afford to come, and didn’t have much appetite for it anyway. Nor did the rest of the class, except for me. I was the only one from the Class of ’65 to show up at the reunion, outnumbered six-to-one by photos of dead classmates taped to one wall of the room. Fortunately, the room was not empty of people, because it was also the 50th reunion of the graduating class of the junior college that shared the same campus, and had absorbed our high school dorm and its classrooms the year after I left. Eighteen Concordia College alumni attended, including some guys who had been two years ahead of me in high school.*

Back to Olivia.

In a high, thin voice, she recounted for me how tortured she felt through all those decades as a female in a male body. She regretted not having been born at a time, like the present, when a child who knows their body is wrongly gendered can get the medical interventions required to grow up in the right one. She said she knew from a young age that she was a lesbian, because she was sexually attracted to girls as a kid, and then women as an adult. She also lamented that the term “transsexual” was not in wide circulation back in our high school years, when it mostly referred to pioneering work Johns Hopkins was doing at the time. So Allan repressed his urge to change sex until finally deciding to become Olivia. This was a deep and moving conversation because A.J. and I were so close in our high school years and yet I had no idea what he, or she, was going through. Finally, she told me she had written an autobiography, and that she would send it to me, hoping I might find a publisher. I told her I would do my best. This was a promise she repeated each time we talked after that.

Two years later, I got a surprising friend request from Allan Ontko on Facebook. The account for Olivia was gone. I accepted, and got this in response to an email:

I gave up on Olivia… the surgery involved in making the full change would have posed some serious risks and would have been totally out of my budgetary means (not to mention the cost of an entirely new wardrobe)… HA!

As we used to say in SC: Call me anything except late for supper…

Not long after that, he wrote this:

It is inconcievable that I will turn 70 this September – but for the nonce I would rather be alive and kicking. I have had a few medical problems – I am developing cataracts and double vision but they aren’t bad enough to require immediate treatment; I had total joint replacement of my right shoulder about 1 1/2 years ago; my Parkinsons is very much under control since about 2 1/2 years ago I was fitted with two brain implants (DBS).

And, I have moved since last May to Spangle WA; a little town of about 238 people which is 18 miles South of Spokane.

His address was a post office box. His phone was a cell.

Our last contact was a series of audio calls over Facebook totaling about an hour on December 17, 2020. He was by then very hard to understand, because advancing Parkinson’s had severely impaired his speech, and the call kept dropping because the connection was so bad. I did gather that he was in a facility of some kind, but I didn’t catch the name. Attempts to reach him after that were for naught.

Then a few days ago I heard from a mutual friend that Allan had died in 2022 of Covid. A search for an obituary then led me to in the Spokane Spokesman-Review, with this entry among them:

ONTKO, Olivia (Age 74) Passed away February 9, 2022

I don’t know where Allan/Olivia died, or what was done with remains or belongings. I also think those facts matter far less than whatever might be in that autobiography. I hope someone reading this might help find it. Sure, it’s a long shot, but ya never know.

It is also an appeal for others to help me fill out this short biography of sorts. (One friend already has, and I’ve made adjustments in the text above.) Allen/Olivia was an extremely unique, talented, and deep person, who deserves to be recognized and remembered for what he and she brought to the world.

*The college, called Corcordia (one of many Lutheran institutions by that name) was by then a four-year college. Five years later it too was gone. The campus, on White Plains Road in Bronxville, New York, is now part of Iona University. It’s quite lovely. Check it out if you’re in the hood.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers