Doc Searls's Blog, page 23

April 4, 2024

Feed Time

I asked ChatGPT to give me “people eating blogs” and got this after it suggested some details.

I asked ChatGPT to give me “people eating blogs” and got this after it suggested some details.Two things worth blogging about that happened this morning.

One was getting down and dirty trying to make DALL-E 3 work. That turned into giving up trying to find DALL-E (in any version) on the open Web and biting the $20/month bullet for a Pro account with ChatGPT, which for some reason maintains its DALL-E 3 Web page while having “Try in ChatGPT ︎” on that page link to the ChatGPT home page rather than a DALL-E one. I gather that the free version of DALL-E is now the one you get at Microsoft’s Copilot | Designer, while the direct form of DALL-E is what you get when you prompt ChatGPT (now 4.0 for Pro customers… or so I gather) to give you an image that credits nothing to DALL-E.

︎” on that page link to the ChatGPT home page rather than a DALL-E one. I gather that the free version of DALL-E is now the one you get at Microsoft’s Copilot | Designer, while the direct form of DALL-E is what you get when you prompt ChatGPT (now 4.0 for Pro customers… or so I gather) to give you an image that credits nothing to DALL-E.

The other thing was getting some great help from Dave Winer in putting the new Feedroll category of placed on this blog, in a way similar stylistically to old-fashioned blogrolls (such as the one here). You’ll find it in the right column of this blog now. One cool difference from blogrolls is that the feedroll is live. Very cool. I’m gradually expanding it.

Meanwhile, after failing to get ChatGPT or Copilot | Designer to give me the image I needed on another topic (which I’ll visit here later) I prompted them to give me an image that might speak to a feedroll of blogs. ChatGPT gave me the one above, not in response to “people eating blogs” (my first attempt), but instead to “People eating phone, mobile and computer screens of type.” Microsoft | Designer gave me these:

Redraw your own inconclusions.

Death is a Feature

When Parisians got tired of cemeteries during the French Revolution, they conscripted priests to relocate bones of more than six million deceased forebears to empty limestone quarries below the city: a hundred miles of rooms and corridors now called The Catacombes. It was from those quarries that much of the city’s famous structures above—Notre Dame, et. al.—were built in prior centuries, using a volume of extracted rock rivaling that of Egypt’s Great Pyramids. That rock, like the bones of those who extracted it, was once alive. In the shot above, shadows of future fossils (including moi) shoot the dead with their cell phones.

When Parisians got tired of cemeteries during the French Revolution, they conscripted priests to relocate bones of more than six million deceased forebears to empty limestone quarries below the city: a hundred miles of rooms and corridors now called The Catacombes. It was from those quarries that much of the city’s famous structures above—Notre Dame, et. al.—were built in prior centuries, using a volume of extracted rock rivaling that of Egypt’s Great Pyramids. That rock, like the bones of those who extracted it, was once alive. In the shot above, shadows of future fossils (including moi) shoot the dead with their cell phones.Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars.

This is a very human thing to want. But before we start following his lead, we might want to ask whether death awaits us there.

Not our deaths. Anything’s. What died there to make life possible for what succeeds it?

From what we can tell so far, the answer is nothing.

To explain why life needs death, answer this: what do plastic, wood, limestone, paint, travertine, marble, asphalt, oil, coal, stalactites, peat, stalagmites, cotton, wool, chert, cement, nearly all food, all gas, and most electric services have in common?

They are all products of death. They are remains of living things or made from them.

Consider this fact: about a quarter of all the world’s sedimentary rock is limestone, dolomite and other carbonate rocks: remains of beings that were once alive. The Dolomites of Italy, the Rock of Gibraltar, the summit of Mt. Everest, all products of death.

Even the iron we mine has a biological source. Here’s how John McPhee explains it in his Pulitzer-winning Annals of the Former World:

Although life had begun in the form of anaerobic bacteria early in the Archean Eon, photosynthetic bacteria did not appear until the middle Archean and were not abundant until the start of the Proterozoic. The bacteria emitted oxygen. The atmosphere changed. The oceans changed. The oceans had been rich in dissolved ferrous iron, in large part put into the seas by extruding lavas of two billion years. Now with the added oxygen the iron became ferric, insoluble, and dense. Precipitating out, it sank to the bottom as ferric sludge, where it joined the lime muds and silica muds and other seafloor sediments to form, worldwide, the banded-iron formations that were destined to become rivets, motorcars and cannons. The is the iron of the Mesabi Range, the Australian iron of the Hammerslee Basin, the iron of Michigan, Wisconsin, Brazil. More than ninety percent of the iron ever mined in the world has come from Precambrian banded-iron formations. Their ages date broadly from twenty-five hundred to two thousand million years before the present. The transition that produced them — from a reducing to an oxidizing atmosphere and the associated radical change in the chemistry of the oceans — would be unique. It would never repeat itself. The earth would not go through that experience twice.

Death produces building and burning materials in an abundance that seems limitless, at least from standpoint of humans in the here and now. But every here and now ends. Realizing that is a vestigial feature of human sensibility.

Take for example, The World Has Plenty of Oil, which appeared in The Wall Street Journal ten years ago. In it, Nansen G. Saleri writes, “As a matter of context, the globe has consumed only one out of a grand total of 12 to 16 trillion barrels underground.” He concludes,

The world is not running out of oil any time soon. A gradual transitioning on the global scale away from a fossil-based energy system may in fact happen during the 21st century. The root causes, however, will most likely have less to do with lack of supplies and far more with superior alternatives. The overused observation that “the Stone Age did not end due to a lack of stones” may in fact find its match.

The solutions to global energy needs require an intelligent integration of environmental, geopolitical and technical perspectives each with its own subsets of complexity. On one of these — the oil supply component — the news is positive. Sufficient liquid crude supplies do exist to sustain production rates at or near 100 million barrels per day almost to the end of this century.

Technology matters. The benefits of scientific advancement observable in the production of better mobile phones, TVs and life-extending pharmaceuticals will not, somehow, bypass the extraction of usable oil resources. To argue otherwise distracts from a focused debate on what the correct energy-policy priorities should be, both for the United States and the world community at large.

In the long view of a planet that can’t replace any of that shit, this is the rationalization of a parasite. That this parasite can move on to consume other irreplaceable substances it calls “resources” does not make its actions any less parasitic.

Or, correctly, saprophytic; since a saprophyte is “an organism which gets its energy from dead and decaying organic matter.”

Moving on to coal, the .8 trillion tons of it in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin now contributes 40% of the fuel used in coal-fired power plants in the U.S. Here’s the biggest coal mine in the basin, called Black Thunder, as it looked to my camera in 2009:

About half the nation’s electricity is produced by coal-fired plants, the largest of which can eat the length of a 1.5-mile long coal train in just 8 hours. In Uncommon Carriers, McPhee says Powder River coal at current rates will last about 200 years.

Then what? Nansen Saleri thinks we’re resourceful enough to get along with other energy sources after we’re done with the irreplaceable kind.

I doubt it.

Wind, tide, and solar are unlikely to fuel aviation, though I suppose fresh biofuel might. Still, at some point, we must take a long view, or join our evolutionary ancestors in the fossil record faster than we might otherwise like.

As I fly in my window seat from place to place, especially on routes that take me over arctic, near-arctic, and formerly arctic locations, I see more and more of what geologists call “the picture”: a four-dimensional portfolio of scenes in current and former worlds. Thus, when I look at the seashores that arc eastward from New York City— Long Island, Block Island, Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, Cape Cod—I see a ridge of half-drowned debris scraped off a continent and deposited at the terminus of an ice cap that began melting back toward the North Pole only 18,000 years ago—a few moments before the geologic present. Back then, the Great Lakes were still in the future, their basins covered by ice that did not depart from the lakes’ northern edges until about 7,000 years ago or 5,000 B.C.

Most of Canada was still under ice while civilization began in the Middle East and the first calendars got carved. Fly over Canada often enough and the lakes appear to be exactly what they are: puddles of a recently melted cap of ice. Same goes for most of the ponds around Boston. Every inland swamp in New England and upstate New York was a pond only a few dozen years ago, and was ice only a dozen or so centuries before that. Go forward a few thousand years and all of today’s ponds will be packed with accumulated humus and haired over by woods or farmland. In the present, we are halfway between those two conditions. Here and now, the last ice age is still ending.

As Canada continues to thaw, one can see human activity spark and spread across barren lands, extracting “resources” from ground made free of permafrost only in the last few years. Doing that is both the economic and the pestilential thing to do.

On the economic side, we spend down the planet’s principal, and fail to invest toward interest that pays off for the planet’s species. That the principal we spend has been in the planet’s vaults for millions or billions of years, and in some cases cannot be replaced, is of little concern to those spending it, which is roughly all of us.

Perhaps the planet looks at our species the same way and cares little that every species is a project that ends. Still, in the meantime, from the planet’s own one-eyed perspective, our species takes far more than it gives, and with little regard for consequences. We may know, as Whitman put it, the amplitude of time. We also tend to assume in time’s fullness all will work out.

But it won’t.

Manhattan schist, the bedrock anchoring New York City’s tallest buildings, is a little over half a billion years old. In about the same amount of time, our aging Sun, growing hotter, will turn off photosynthesis. A few billion years later, the Sun will swell into a red giant with a diameter wider than Earth’s orbit, roasting the remains of our sweet blue planet and scattering its material out into the cosmos, perhaps for eventual recycling by stars and planets not yet formed.

In a much shorter run, many catastrophes will happen. One clearly is what our species is already doing to the planet during what geologists correctly call the Anthropocene. I suppose that’s a good reason for Elon and crew to “save” a few members of our vain little species. But why fuck up Mars before we’re done fucking up Earth, when there’s still some leverage with the death we have at home and that Mars won’t begin to have until stuff dies on it?

I’ve always been both an optimist and a realist. Specifically, I’m an optimist for at least the short run, by which I mean the next few dozen years. But I’m a pessimist for our civilization — and our species. Death is always a winning bet.

But hey, maybe nature knows better what to do with us than we do.

The first ancestor of this piece appeared in blogs.harvard.edu on 4 March 2008. The second is here on Medium.

Looking for DALL-E 3 Help

I just returned to DALL-E 3 after using its Microsoft version (currently called Copilot | Designer) for a while. But I can’t get in.

I just returned to DALL-E 3 after using its Microsoft version (currently called Copilot | Designer) for a while. But I can’t get in.See how it says “Try in ChatGPT ︎?” When I do that, it goes to https://chat.openai.com/. After I log in there, it offers no clue about where DALL-E 3 is. So I asked, “How do I get to the DALL-E 3 page after I’m logged in here?”

︎?” When I do that, it goes to https://chat.openai.com/. After I log in there, it offers no clue about where DALL-E 3 is. So I asked, “How do I get to the DALL-E 3 page after I’m logged in here?”

ChatGPT answered, “As of my last update in January 2022, DALL-E 3 is a hypothetical iteration of the DALL-E model, and there’s no information about its existence or how to access it. If it were to be released, you might typically find access through OpenAI’s website or platform if they make it available to the public. However, without further updates or announcements, it’s challenging to provide specific instructions. If OpenAI releases DALL-E 3 or any similar model in the future, you can check their official website or announcements for information on how to access it.”

Additional useless dialog followed. So now I’ll ask the Lazyweb. Does anyone know how to get into DALL-E 3?

March 27, 2024

Why selling personal data is a bad idea

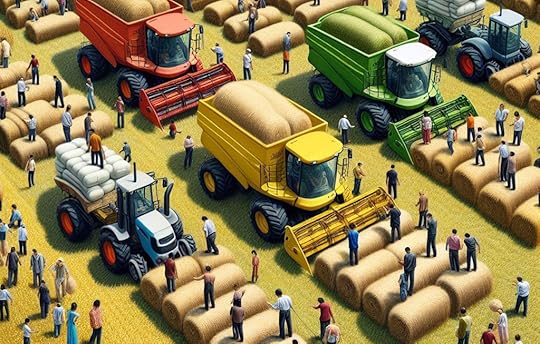

Prompt: “a field of many different kinds of people being harvested by machines and turned into bales of fertilizer.” Via Microsoft CoPilot | Designer.

Prompt: “a field of many different kinds of people being harvested by machines and turned into bales of fertilizer.” Via Microsoft CoPilot | Designer.This post is for the benefit of anyone wondering about, researching, or going into business on the proposition that selling one’s own personal data is a good idea. Here are some of my learnings from having studied this proposition myself for the last twenty years or more.

The business does exist. See eleven companies in Markets for personal data listed among many other VRM-ish businesses on the ProjectVRM wiki.The business category harvesting the most personal data is adtech (aka ad tech and “programmatic”) advertising, which is the surveillance-based side of the advertising business. It is at the heart of what Shoshana Zuboff calls surveillance capitalism, and is now most of what advertising has become online. It’s roughly a trillion-dollar business. It is also nothing like advertising of the Mad Men kind. (Credit where due: old-fashioned advertising, aimed at whole populations, gave us nearly all the brand names known to the world). As I put it in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff, Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself.Adtech pays nothing to people for their data or data about them. Not personally. Google may pay carriers for traffic data harvested from phones, and corporate customers of auctioned personal data may pay publishers for moments in which ads can be placed in front of tracked individuals’ ears or eyeballs. Still, none of that money has ever gone to individuals for any reason, including compensation for the insults and inconveniences the system requires. So there is little if any existing infrastructure on which paying people for personal data can be scaffolded up. Nor are there any policy motivations. In fact,Regulations have done nothing to slow down the juggernaut of growth in the adtech industry. For Google, Facebook, and other adtech giants, paying huge fines for violations (of the GDPR, the CCPA, the DMA, or whatever) is just the cost of doing business. In fact, the GDPR compliance services business is itself n the multi-$billion range, and growing fast. In fact,Regulations have made the experience of using the Web worse for everyone. Thank the GDPR for all the consent notices subtracting value from every website you visit while adding cognitive overhead and other costs to site visitors and operators. In nearly every case, these notices are ways for site operators to obey the letter of the GDPR while violating its spirit. And, although all these agreements are contracts, you have no record of what you’ve agreed to. So they are worse than worthless.Tracking people without their clear and conscious invitation or a court order is wrong on its face. Period. Full stop. That tracking is The Way Things Are Done online does not make it right, any more than driving drunk or smoking in crowded elevators was just fine in the 1950s. When the Digital Age matures, decades from now, we will look back on our current time as one thick with extreme moral compromises that were finally corrected after the downsides became clear and more ethically sound technologies and economies came along. One of those corrections will be increasing personal agency rather than just corporate capacities. In fact,Increasing personal independence and agency will be good for markets, because free customers are more valuable than captive ones. Having ways to gather, keep, and make use of personal data is an essential first step toward that goal. We have made very little progress in that direction so far. (Yes, there are lots of good projects listed here, but there we still a long way to go.)Businesses being “user-centric” will do nothing to increase customers’ value to themselves and the marketplace. First, as long as we remain mere “users” of others’ systems, we will be in a subordinate and dependent role. While there are lots of things we can do in that role, we will be able to do far more if we are free and independent agents. Because of that,We need technologies that create and increase personal independence and agency. Personal data stores (aka warehouses, vaults, clouds, life management platforms, lockers, and pods) are one step toward doing that. Many have been around for a long time: ProjectVRM currently lists thirty-three under the Personal Data Stores heading. Some have been there a long time. The problem with all of them is that they are still too focused on what people do as social beings in the Web 2.0 world, rather than on what they can do for themselves, both to become more well-adjusted human beings and more valuable customers in the marketplace. For that,It will help to have independent personal AIs. These are AI systems that work for us, exclusively. None exist yet. When they do, they will help us manage the personal data that fully matters:Contacts—records and relationshipsCalendars—where we’ve been, what we’ve done, with whom, where, and whenHealth records and relationships with providers, going back all the wayFinancial records and relationships, including past and present obligationsProperty we have and where it is, including all the small stuffShopping—what we’ve bought, plan to buy, or might be thinking about,Subscriptions—what we’re paying for, when they end or renew, what kind of deal we’re locked into, and what better ones might be out there.Travel—Where we’ve been, what we’ve done, with whom, and whenPersonal AIs are today where personal computers were fifty years ago. Nearly all the AI news today is about modern mainframe businesses: giants with massive data centers churning away on ingested data of all kinds. But some of these models are open sourced and can be made available to any of us for our own purposes, such as dealing with the abundance of data in our own lives that is mostly out of control. Some of it has never been digitized. With AI help it could be.

I’m in a time crunch right now. So, if you’re with me this far, read We can do better than selling our data, which I wrote in 2018 and remains as valid as ever. Or dig The Intention Economy: When Customers Take Charge (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012), which Tim Berners Lee says inspired Solid. I’m thinking about following it up. If you’re interested in seeing that happen, let me know.

March 19, 2024

The Online Local Chronicle

Bloomington Hospital on October 15, 2022, right after demolition began.

Bloomington Hospital on October 15, 2022, right after demolition began.After we came to Bloomington in the summer of 2021, we rented an apartment by Prospect Hill, a quiet dome of old houses just west of downtown. There we were surprised to hear, nearly every night, as many police and ambulance sirens as we’d heard in our Manhattan apartment. Helicopters too. Soon we realized why: the city’s hospital was right across 2nd Street, a couple blocks away. In 2022, the beautiful new IU Health Bloomington Hospital opened up on the far side of town, and the sounds of sirens were replaced by the sounds of heavy machinery slowly tearing the old place down.

Being a photographer and a news junkie, I thought it would be a good idea to shoot the place often, to compile a chronicle of demolition and replacement, as I had done for the transition of Hollywood Park to SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, California. But I was too busy doing other things, and all I got was that photo above, which I think Dave Askins would categorize as a small contribution to topical history.

Dave is a highly productive local journalist, and—by grace of providence for a lifelong student of journalism such as me—the deepest and most original thinker about what local news needs. I’ve shared some of Dave’s other ideas (and work) in the News Commons series, but this time I’m turning a whole post over to him. Dig:::::

In the same way that every little place in America used to have a printed newspaper, every little place in America could have an online local chronicle.

Broadly speaking, an online local chronicle is a collection of facts organized mostly in chronological order. The “pages” of the chronicle can be thought of as subsets of a community’s universal timeline of events. These online local chronicles could become the backbone of local news operations.

First a word about what a local chronicle is not. It is not an online encyclopedia about the little place. It’s not a comprehensive history of the place in any conventional sense. Why should it not try to be those things? Because those things are too hard to think about building from scratch. Where would you even start?

It is at least conceivable that an online local chronicle could be built from scratch because you start by adding new facts that are newsworthy today. A new fact added to the chronicle is a touchstone, about which anyone can reasonably ask: What came just before that?

A working journalist in a little place with an online local chronicle will be in a good position to do two things: (1) add new facts to the local chronicle (2) help define sets of old facts that would be useful to include in the online local chronicle.

A journalist who is reporting the news for a little place would think not just about writing a report of new facts for readers today. They would keep this question in mind: What collection of old facts, if they were included in the local chronicle, would have made this news report easier to write?

Here’s a concrete example. A recent news report written for The B Square Bulletin included a mention of a planned new jail for Monroe County. It included a final sentence meant to give readers, who might be new to that particular topic, a sense of the basic reason why anyone was thinking about building a new jail: “A consultant’s report from two and a half years ago concluded that the current jail is failing to provide constitutional levels of care.”

About that sentence, a reader left the following comment on the website: “I know it’s the last sentence in an otherwise informative article, but at the risk of nit-picking that sentence seems inadequate to the task of explaining the context of the notion of a new jail and the role of the federal court and the ACLU.”

The comment continues: “It would have been better, Dave, to link to your own excellent previous work: https://bsquarebulletin.com/2023/02/20/monroe-county-sheriff-commissioners-square-off-at-committee-meeting-aclu-lawyer-says-look-you-need-a-new-jail-everyone-knows-that/”

What this reader did was to identify a set of old facts that should be a collection (a page) in Bloomington’s local chronicle.

It’s one thing to identify a need to add a specific collection of facts to the local chronicle. It’s quite another to figure out who might do that. Working journalists might have time to add a new fact or two. But to expect working journalists to add all the old sets of facts would, I think, be too tall an order.

The idea would be to recruit volunteers to do the work of adding old facts to the online local chronicle. They could be drawn from various segments of the community—including groups that have an interest in seeing the old facts about a particular topic not just preserved, but used by working journalists to help report new facts.

I think many community efforts to build a comprehensive community encyclopedia have foundered, because the motivation to make a contribution to the effort is mostly philosophical: History is generally good to preserve.

The motivation for helping to build the online local chronicle is not some general sense of good purpose. Rather it is to help working journalists provide useful facts for anyone who in the community who is trying to make a decision.

That includes elected leaders. They might want to know what the reasons were at the time for building the current jail at the spot where it is now.

Decision makers include voters, who might be trying to decide which candidate to support.

Decision makers also include rank-and-file residents—who might be trying to decide where to go out for dinner and want to know what the history of health inspections for a particular restaurant are.

For the online local chronicle I have set up for Bloomington, there are very few pages so far. They are meant to illustrate the general concept:

https://thebloomingtonchronicle.org/index.php/Main_PageThe pages are long on facts that are organized in chronological order, and short on narrative. Here are the categories that include at least one page.

Category: People

Category: Data

Category: Boards, Commissions, Councils

Category: List

Category: Topical History

==========

–Dave

By the way, if you’d like to help local journalism out, read more about what Dave is up to—and what he needs—here: https://bsquarebulletin.com/about/

The end of what’s on, when, and where

But not of who, how, and why. Start by looking here:

That’s a page of TV Guide, a required resource in every home with a TV, through most of the last half of the 20th century.

Every program was on only at its scheduled times. Sources were called stations, which broadcast over the air on channels, which one found using a dial or a display with numbers on it. Stations at their largest were regional, meaning you could only get them if you were within reach of signals on channels. To get those signals you needed an antenna on “rabbit ears” on your TV. Signals came from high on towers, buildings, or mountains, but were thwarted by other buildings, mountains, the inverse square law, and the inconvenient fact that the Earth is round.

By the time TV came along, America had already devoted its evenings to consuming scheduled

programs on AM radio, which was the only kind at the time. After TV took over, America whole populations sat in rooms bathed in soft blue light from TV screens. Radio was repurposed for music, especially rock & roll. My first radio was the one on the right. My stations were WMCA/570, WMGM/1050, WINS/1010, WABC/770, and WKBW/1520. All of those are still on the air, but playing talk and sports. Many fewer people know that fact, or care, or listen to AM radio, or over-the-air anything, anymore. They watch and listen to glowing rectangles that connect to the nearest router, wi-fi hot spot, or cellular data site. Antennas exist, but wavelengths are so short that the antennas fit inside the rectangles.

The question “what’s on?” is mostly gone. “Where?” is still in play, because nobody knows what streaming service carries what you want. All the “guides”—Apple’s, Google’s, Amazon’s, everyone’s—suck, either because they’re biased to promote their own content or because there’s simply too much content and no system can cover all of it. Search engines help, but not enough.

The age we’re closing is the one Jeff Jarvis calls The Gutenberg Parenthesis. The age we’re entering is the Age of Optionality. It began for print with blogging, for TV with VCRs and DVRs, and for radio with podcasting and streaming. And it began to obsolesce all the media we knew, almost too well, by putting it in hands Clay Shirky told us about in 2009 with Here Comes Everybody.

So what we make of it is up to all of us. We are who, how, and why.

March 13, 2024

Happy Birthday, Mom

Eleanor Oman, Alaska, circa 1942

Eleanor Oman, Alaska, circa 1942Mom would have been 111 today. She passed in ’03 at 90, but that’s not what matters.

What matters is that she was a completely wonderful human being: as good a mother, sister, daughter, cousin, friend, and teacher as you’ll find.

There is a thread in Facebook (which seems to be down now) on the subject of Mom as a third and fourth grade teacher in the Maywood New Jersey public school system. Students who inhabited her classes more than half a century ago remember her warmly and sing her praises. Maybe I’ll quote some of those later. (I’m between flights right now, but getting ready to board.)

Once, sitting around a fire in the commune-like place where I lived north of Chapel Hill in the mid-’70s, discussion came around to “Who is the sanest person you know?” I said “My mother.” Others were shocked, I suppose because they had issues with their moms. But I didn’t. Couldn’t. She was too wise, good, and loving. (Also too smart, quick-witted, tough, and unswayed by bullshit.)

Perhaps I’m idealizing too much. She had flaws, I’m sure. But not today.

February 21, 2024

Ripples

The song “Ripple,” by the Grateful Dead, never fails to move me. Here’s a live performance by the Dead, in 1980, on YouTube.

My favorite version, however, is this one by KPIG’s Fine Swine Orchestra, recorded by Santa Cruz musicians sheltering in place during the pandemic. That’s a screen grab, above.

I am pretty sure I’ve blogged about “Ripple” before, but can’t find evidence of that right now, perhaps because I published it somewhere obscure, or perhaps because we have entered the Enshittocene. Whatever the case, it doesn’t hurt to re-hear a classic.

KPIG, long one of my favorite radio stations, is no longer live streaming for the world, but for subscribers only. (It’s free only for a week.) I know they need the money. But so does Radio Paradise, which has KPIG ancestry, is free, and supported by donations.

Toward normalizing the donations for every worthy thing, see what I wrote here.

On Blogs

Kurt Vonnegut’s typewriter (and glasses), at the Vonnegut Museum in Indianapolis. Shot by me with a phone.

Kurt Vonnegut’s typewriter (and glasses), at the Vonnegut Museum in Indianapolis. Shot by me with a phone.Thoughts I jotted down on Mastodon*:

1) Blogs are newsletters that don’t require subscriptions.

2) Blogrolls are lists of blogs.

3) Both require the lowest possible cognitive and economic overhead.

4) That’s why they are coming back.

I know, they never left. But you get my point.

*I just learned that my Mastodon account is only for followers. I hope to fix that.

February 19, 2024

On too many conferences

Prompt: “Many different conferences and meetings happening all at once in different places” Rendered by Microsoft Copilot / Designer

Prompt: “Many different conferences and meetings happening all at once in different places” Rendered by Microsoft Copilot / Designer

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers