Doc Searls's Blog, page 26

November 3, 2023

Some remodeling work

As Dave says here, we’re remodeling this blog a bit, starting with the title image, which for the last few years has been a portrait of me at work, drawn by the fashion illustrator Gregory Wier-Quitton.

My likeness online is not in short supply. Here’s a sampling from a DuckDuckGo image search for my name:

image search for Doc Searls

Dave likes this one, from Flickr:

Lacking vanity toward my visage, I don’t like any of them.

I also don’t think it’s right to use a shot in which my head still had enough hair on top to comb. Until my late ’60s, I thought I was free of the family curse (on my mother’s side), but then most of it fell out as if I was on chemo. While it’s true, as Dave says, that I’ve had hair for most of the time I’ve been blogging—and for the much longer stretch of the time I’ve been writing—the simple fact is that I no longer look like I did when I needed a barber. Also, in 2017 my eyelids were surgically exposed by removing the forehead that was falling down into my vision and squeezing my eyeballs out of spherity. (This was a medical move, not a cosmetic one.) This also altered my look.

Somewhere in the oeuvre of Fran Liebowitz, she advises readers worried about their aging faces to confront a mirror and realize this: “It only gets worse.”

With that and the spirit of whatever-based renovation in mind, does this blog need an image of me on top? I could fill my screen and yours running down a list of fine blogs and newsletters that don’t feature their authors’ image in a header—or anywhere except maybe an About page.

I love how Dave’s blog is titled with self-replacing images from his own library. If we were to do that here, I have 6 TB of photos we can choose from, with more than 66,000 of them on Flickr alone.

There are lots of possibilities. So, I invite recommendations.

October 31, 2023

Whither Medium?

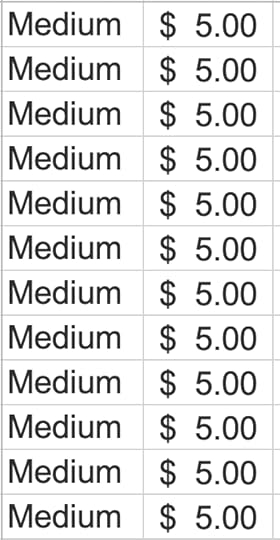

I subscribe to Medium. It’s not expensive: $5.00 per month. I also pay about that much to many newsletters (mostly because Substack makes it so easy). And that’s 0n top of what I also pay The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Reason, The Sun, Wired, and others that aren’t yet showing up on the giant spreadsheet I’m looking at, with expense-cutting in mind.

I subscribe to Medium. It’s not expensive: $5.00 per month. I also pay about that much to many newsletters (mostly because Substack makes it so easy). And that’s 0n top of what I also pay The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Reason, The Sun, Wired, and others that aren’t yet showing up on the giant spreadsheet I’m looking at, with expense-cutting in mind.

I started blogging in Medium because Ev Williams created it, with lots of noble intentions, and I wanted to support Ev and his work. I also liked its WYSIWYG-y approach to composing pages. And I liked the stats, though I mostly stopped looking at them after they defaulted to highlighting how many claps a piece gets. I never liked the claps thing.

I forget why I started paying. I half remember that it was around when they pitched me on maybe making money blogging after the subscription system started up. I wasn’t interested in that, but I was interested in Medium experimenting with money-making.

But the whole system seemed kinda complicated, so I didn’t pay much attention to it. I just kept posting now and then, and it seemed to work well enough, I suppose because I didn’t see the paywall. Or worse, I did see the paywall when something I wrote got popular and became “Members Only” somehow.

I see it now on this post by Doug Rushkoff and this one by Cory Doctorow. Yes, I can read them in this browser, which has a cookie that remembers that I’m a paying member; but it doesn’t on any of the other browsers I use for different purposes, and I don’t feel like logging in on all of them.

Call me old-fashioned, but I hate being teased into subscriptions. That’s why I’ve been dropping subscriptions to newsletters that tease readers into a paywall. I feel over-subscribed as it is, and the paywall tease is just rude. Ask, don’t coerce.

Here’s a lesson, newsletter writers: Heather Cox Richardson’s Letters From an American is the top-earning newsletter out there, and she doesn’t have a paywall. She makes all that money (an estimated $5 mllion/year) in voluntary payments.

The question for me now is, Do I want to move my 105 Medium posts somewhere else, or just have faith that they’ll stay up where they are?

The one thing I’m sure about now is that I’m done posting there. Ev is gone. My own reading and writing energies are too spread out. One less place to write is a good thing.

I have three blogs right here using WordPress, and I want to focus on those, and on allied efforts that seem to be moving in the same directions.

Some of my old Medium posts may be worth saving somewhere else, such as here. But maybe what I haven’t yet written is more important than what I’ve written already.

October 20, 2023

Deeper News

The Tessereact, a structure that allows travel in time through a deep library, from the movie “Interstellar.”

Let’s say you’re a public official. Or an engineer. Or a journalist researching a matter of importance, such as a new reservoir or a zoning change. What do you need?

In a word, facts. This should go without saying, but it bears saying because lots of facts are hard to find. They get lost. They decay. Worse, in their absence you get hearsay. Conjecture. Gossip. Mis and Dis information. Facts can also get distorted or excluded when they don’t fit a story. This is both a feature and a bug of storytelling. I reviewed this problem in Stories vs. Facts.

So how do we keep facts from decaying? How do we make them useful and accurate when future decisions require them?

Two ways.

One is by treating news as history. You do this by flowing news into well0-curated archives that remain accessible for the duration.

The other is to gather and produce facts that don’t make news but might someday—and flow those into curated archives as well.

In both cases, we are talking about facts that decision-makers may need to do their work, whether or not their work produces news.

So let’s start with history.

Timothy Snyder defines history as “what’s possible.” In his Yale lectures on The Making of Modern Ukraine, he also says history is discontinuity. By that, he means we give the most significance to moments of change, to times of transition. Elections. Wars. Disasters. Championships. And we tend to ignore what’s not making news in the meantime. We also tend to ignore the kind of news that just burbles along, not sounding especially historical, but is interesting to readers, watchers, and listeners—and might be relevant again. This is most of what gets reported by the obsessives who still produce local news. But how much of that stuff gets saved? And where?

Here in Bloomington, Indiana, the big industries for more than a century were limestone, furniture, and radio and television manufacture. Specifically,

The limestone industry is still large and likely to stay that way until demand for premium limestone goes away (my guess is a few centuries from now).The furniture industry came and went in about seven decades, but at its peak Showers Brothers Furniture produced a lion’s share of the affordable furniture sold in the U.S.In the Forties and Fifties, so many radios and TVs were made here that Bloominngton for a time called itself “the color TV capitol of the world.”If you haven’t seen Breaking Away yet, please do. Besides being one of the greatest coming-of-age stories ever told, it’s an excellent look at Bloomington’s small-town/big university charms, plus its limestone industry and the people who worked in it, back when the quarries and the cutting plants were still right in town. (They’re still around, but out amidst the farmlands.)

In Showers Brothers Furniture Company: The Shared Fortunes of a Family, a City and a University (Quarry Books, 2012), Carol Krause gives a sense of how huge a business Showers Brothers was at the time:

Shipments averaged seventy rail carloads per month. The sawmill daily cut 25,000 feet of lumber at that time and secured its lumber by purchasing large tracts of land and then logging them. This is undoubtedly part of the reason that so much of the land around Monroe and surrounding counties had been completely clear-cut early by the twentieth century.” (p. 121)

Her source for that was the April 26, 1904 issue of Bloomington Courier, then one of two papers competing to serve a town of about seven thousand people. But countless other bits of history are forever gone. In her notes about sources, Krause writes,

The business records of the Showets company have unfortunately been lost, and only a handful of the annual furniture catalogs survive, despite decades of publication. We no longer have the training materials that the company distributed to its salesme, and we have virtually no remaining business correspondence. As for family papers, we possess only the handwritten memoir of James Showers, the spiritual daybook of his mother, Elizabeth, and a small handful of family photographs. There is also no comprehensive Bomington history that sums up the major events or characters in the company’s history. Owing to the lack of records, this work relies largely upon accounts published in newspapers of the period. this record is fragmentary during the early years and we cannot consider any of it fully accurate or complete, because of the political partiality of the newspaper publishers. Nevertheless, newppaper records are the single largest remaining source of information available about the Showers family and its company, so this book reflects countless hours spent at the microfilm machines at the public library, perusing the headlines of bygone times. (p. xv)

Bloomington is fortunate to have an unusually thick collection of factual resources in the Monroe County library system and history center. Without those, Carol Krause probably wouldn’t have written her book at all. (Alas, she passed in 2014. Here is a Herald-Times obituary.)

The best sources I’ve found for Bloomington’s history as a broadcasting town are Bloomingpedia and Wikipedia. From the former:

In 1940 RCA moved a major manufacturing plant from Camden, NJ to Bloomington. The 1.5 million square foot RCA plant, although originally planned to build radios, was converted to televisions when that technology became viable, and when the first television came off the line on September 6, 1949, “TV Day” was declared in Bloomington. The plant was located on south Rogers Street, and produced more than 65 million televisions over the next 50 years. The factory employed over 8,000 workers at its peak, roughly 2% of the entire Bloomington workforce, and also provided many jobs for industries servicing the plant. Sarkes Tarzian, Inc. was among these. For a while, Bloomington called itself the “Color Television Capital of the World”.

Labor unrest began to swirl in the 1960’s. In 1964 5000 workers walked off the job over the protest of both management and union leaders. After a week, a new contract was approved and the workers returned to the assembly lines; but in October of 1966 the workers stuck again, claiming the company was in violation of the union contract, and several violent scuffles were reported. In 1967 a third, rather disorganized strike also took place.

In 1968, over 2000 people were laid off; mostly the young female workers that were considered to be most skilled at the delicate work of assembling televisions on the line.

RCA was bought by General Electric in 1986, then immediately sold to the French company Thomson SA, and rumors of the plant closing immediately began. On April 1, 1998, the last television rolled off the line and Thomson moved the plant to Juarez, Mexico, where RCA had had a small plant as early as 1968.

And from Wikipedia:

The Sarkes Tarzian company was an important manufacturer of radio and television equipment, television tuners, and components. Its FM radio receivers helped to popularize the broadcast medium. Sarkes Tarzian manufactured studio color TV cameras in the mid-1960s.[16] The manufacturing operations were spun off in the 1970s and today the company still exists as a broadcaster, owning several television and radio stations. Gray Television has owned a partial stake in Sarkes Tarzian, Inc., since the early 2000s.

Those are all great sources, the holes are bigger than the hills.

We also have a new situation on our hands, now that we are completing what Jeff Jarvis calls The Gutenberg Parenthesis: the age of print. How do we best accumulate and curate useful facts in our still-new digital age?

Back in 2001, my son Allen astutely noted that the World Wide Web was splitting between what he called the Static Web and the Live Web. Here is what I wrote about the former in the October 2005 edition of Linux Journal:

There’s a split in the Web. It’s been there from the beginning, like an elm grown from a seed that carried the promise of a trunk that forks twenty feet up toward the sky.

The main trunk is the static Web. We understand and describe the static Web in terms of real estate. It has “sites” with “addresses” and “locations” in “domains” we “develop” with the help of “architects”, “designers” and “builders”. Like homes and office buildings, our sites have “visitors” unless, of course, they are “under construction”.

One layer down, we describe the Net in terms of shipping. “Transport” protocols govern the “routing” of “packets” between end points where unpacked data resides in “storage”. Back when we still spoke of the Net as an “information highway”, we used “information” to label the goods we stored on our hard drives and Web sites. Today “information” has become passé. Instead we call it “content”.

Publishers, broadcasters and educators are now all in the business of “delivering content”. Many Web sites are now organized by “content management systems”.

The word content connotes substance. It’s a material that can be made, shaped, bought, sold, shipped, stored and combined with other material. “Content” is less human than “information” and less technical than “data”, and more handy than either. Like “solution” or the blank tiles in Scrabble, you can use it anywhere, though it adds no other value.

I’ve often written about the problems that arise when we reduce human expression to cargo, but that’s not where I’m going this time. Instead I’m making the simple point that large portions of the Web are either static or conveniently understood in static terms that reduce everything within it to a form that is easily managed, easily searched, easily understood: sites, transport, content.

At the time I thought—we all thought—that the Live Web was blogs. But then social media came along, mostly in the forms of Twitter and Facebook. Google also began to index the Web in real time, and soon began to supply the world with live information such as traffic densities on maps in apps running on hand-held phones connected to the Internet full time.

As I shared in Deep News., Dave Askins of the B Square Bulletin would like us to create a “digital file repository”—” a place where anyone—journalists, public officials, and residents of all stripes—can upload digital files, so that others can have access to those files now and until the end of time. It can also serve as a backup for files that the city has made public on its website, but could remove at any time.”

Dave has also added Monroe County (including Bloomngton) to LocalWiki, which is Wikipedia’s place for places to have their own wikis, including digital file repositories. I’ve contributed a local media section.

I have a lot more to say about this, but want to get what I have so far up on the blog, where others can help improve the post. So stay tuned for that.

October 18, 2023

What is a “stake” and who holds one?

I once said this:

That’s Peter Cushing (familiar to younger folk as Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars) pounding a stake through the heart of Dracula in the 1958 movie that modeled every remake after it. Other variants of that caption and image followed, some posted on Twitter before it was bitten by Musk and turned into a zombie called X.

After work started on IEEE P7012—Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, I posted this one:

Merriam-Webster says stakeholder means these things:

1: a person entrusted with the stakes of bettors

2: one that has a stake in an enterprise

3: one who is involved in or affected by a course of action

Specifically (at that second link), a stake is an interest or share in an undertaking or enterprise (among other things irrelevant to our inquiry here).

Do we have an interest in the Internet? In the Web? In search? In artificial intelligence? When “stakeholders” are talked about for any of those things, they tend to be ones in government and industry. Not you and me.

Was anyone representing you at the White House Summit on Artificial Intelligence? How about the AI World Congress coming up next month in London? Or any of the many AI conferences going on this year? Of course, our elected representatives and regulators are supposed to represent us, mostly for the purpose of protecting us as mere “users.” But as we know too well, regulators inevitably work for the regulated. Follow the money.

So my case here is not for regulators to play the Peter Cushing role. That job is yours and mine. We just need the weapons—not just to kill surveillance capitalism, but to do all we can to stop AI from making surveillance more pervasive and killproof than ever.

At this point, just imagining that is still hard. But we need to.

October 13, 2023

Building Better AI

What shall we make of AI?

Marina Zannoli has something to say about that, and she’ll say it this coming Tuesday, October 17, at Indiana University—and online too, at 12pm Eastern time. The title of her talk is Mastering AI: What I Learned as the Chief of Staff of Fundamental AI Research at Meta.

Though her work at Meta, Dr. Zannoli has come to believe that maximizing what’s useful about AI and minimizing what’s scary requires close collaboration between academic, industry, and governmental organizations. She’ll explain how in a lively discussion that will take place at the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies at IU, and online via Zoom (on a wall-sized screen).

Her talk is the second in this year’s Beyond the Web Salon Series, themed Human +/vs. Artificial intelligence. It is co-hosted Ostrom Workshop and the Hamilton Lugar School, both at IU.

The cost is $0, but you have to register to attend the Zoom. Do that here. And I’ll see you there.

The image above was generated by Bing Image Creator, using a prompt I can’t find right now but was something like, “Give me an image of people building a giant AI.” It was my first whack at using the service, and I think it worked pretty well.

October 12, 2023

Stories vs. Facts

Stories and facts have always been frenemies. Stories can get along fine without facts, though facts are good to have for framing up stories. Facts by themselves are blah, and need stories to become interesting. So: different beasts, often in conflict, which can make great stories too.

Like right now, when my wife and I are watching The Diplomat on Netflix. The whole series is about the conflict between stories and facts. But then, so is every movie or series about journalism, newsrooms, or any topic where what’s true and what’s being said don’t square up.

In Where Journalism Fails I explain that stories are what journalism sells. Back when we still had newspapers with newsrooms, senior editors constantly barked the same three words at reporters: What’s the story? Because stories are the base format of human interest. That’s why stories sell. It’s why you keep watching, listening, and turning pages.

So it helps to know what the story format is, and how it works. Fortunately, it’s simple. Stories have three elements:

CharacterProblemMovementThe character can be a person, a cause, a team, a politician, whatever. They can be good or bad, old or young, rich, poor, strange, or anything—as long as they are interesting. To be a character is to be interesting. Stories usually have a collection of them.

The problem is anything that creates or sustains conflict. There can any number of problems as well.

Movement has to be toward resolution, even if that never happens. Without movement, the story collapses.

If your team is up by forty points and there are two minutes left to play, the character that matters is you, and your problem is getting out of the parking lot. After all, many stories are happening at any one time, and you are the lead character in most of them.

Here are another three words you need to know: Facts don’t matter.

Daniel Kahneman says that. So does Scott Adams.

Kahneman says facts don’t matter because people’s minds are already made up about most things, and what their minds are made up about are stories. People already like, dislike, or actively don’t care about the characters involved, and they have well-formed opinions about whatever the problems are.

Adams puts it more simply: “What matters is how much we hate the person talking.” In other words, people have stories about whoever they hate. Or at least dislike.

Now we like to call stories “narratives.” Whenever you hear somebody talk about “controlling the narrative,” they’re not talking about facts. They want to shape or tell stories that may have nothing to do with facts.

But let’s say you’re a decision-maker: the lead character in a personal story about getting a job done. You’re the captain of a ship, the mayor of a town, the detective on a case. What do you need most? Somebody’s narrative? Or facts?

Wouldn’t it be better to have facts than to guess at them? Or to take as fact what somebody simply claims?

This is half of my case for Deep News. The other half is the need to formalize the way we accumulate facts over time, so the result is what we might call history-based news. Because history is made of facts. We’ll tell better stories and make better decisions if we base them on facts.

So it matters how we assemble and accumulate facts, and how we do this together. I’ll visit that in my next post

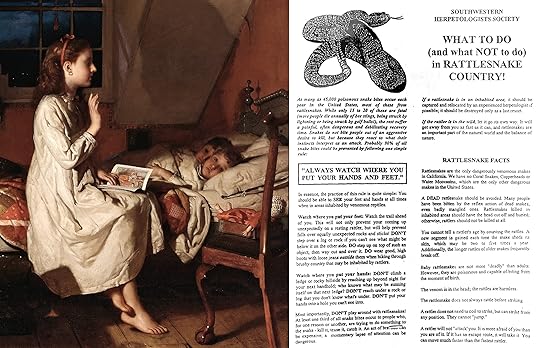

The image above combines the Story of Golden Locks, a painting by Seymour Joseph Guy (MET, 2013.604), via Wikimedia Commons, and a warning posted on Mt. Wilson in California.

September 24, 2023

Facts vs. Stories

Facts don’t matter.

Daniel Kahneman says that. So does Scott Adams. Kahneman follows those three words with these: ” .” Adams follows his three with “What matters is how much we hate the person talking.”

September 15, 2023

We Need Whole News

Journalism is in trouble because journals are going away. So are broadcasters that do journalism rather than opinionism.

Basically, they are either drowning in digital muck or adapting to it. Also in that muck are a zillion new journalists, born native to digital life. Those zillions include everybody with something to say, for example with blogs or podcasts. As Clay Shirky said (in a book that’s relevant in ways we’ll visit below), Here Comes Everybody.

An odd fact about digital life is that its world is the Internet, which works by eliminating the functional distance between everybody and everything. Think of this habitat as a giant three-dimensional zero: a hollow sphere with an interior that is as close to zero as possible in both distance and cost. This is a very weird space that isn’t one, even though we call it one because space works as a metaphor.

But we are all embodied creatures operating in a natural world with plenty of distance and lots of costs. This is why we form communities, towns and cities, organizations, institutions, and social networks of people who see and talk to each other in the flesh.

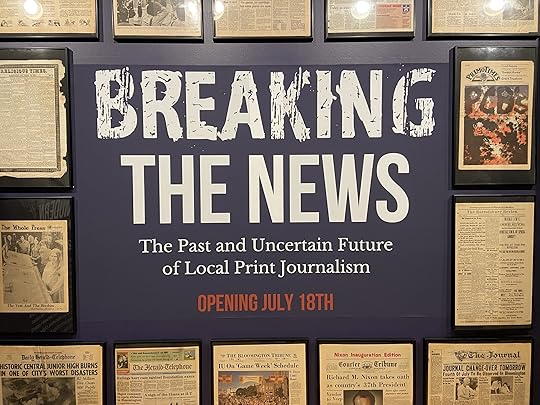

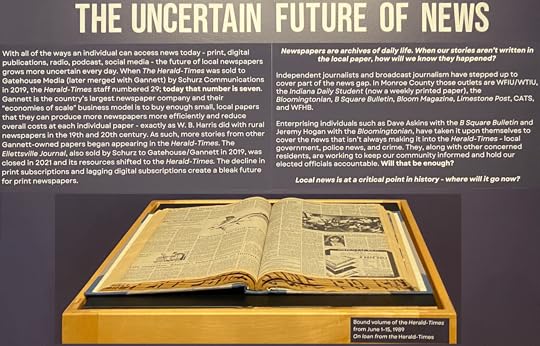

For more than a century, the information center that held a town or a city together was its newspaper. This is no longer the case. Here is how the Monroe Country History Center and the Herald-Times (our local paper) explain the situation in an outstanding exhibit at the Center’s museum called Breaking the News:

If you’re reading this on something small, click on it to see the full-size original.

But hey! There are still plenty of journals, journalists, and news sources here in town, including the Herald-Times. That’s some of their logos, gathered at the top of this page. I also listed them in my last post, calling them all, together, wide news. If their work is well-archived we’ll also have what I call deep news in the prior post.

I suggest that the answer to the question asked by that exhibit—where will it go now?— is whole news. That’s what you get when all these media cohere into both a commons and a market.

And, as it happens, we have some resources for creating both.

One is the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University, where my wife Joyce and I are both visiting scholars. The workshop carries forward the pioneering work of Elinor Ostrom, who won a Nobel Prize in economics for her work on commons of many kinds. If we’re going to make a whole news commons, the Workshop can be hugely helpful. (So can other folks we know, such as Clay Shirky. Note that the subtitle of Here Comes Everybody is The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. Clay will be here to speak in our salon series at IU in December.)

Another is Customer Commons, a nonprofit that Joyce and I started as part of ProjectVRM, which we launched when I started a fellowship at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center in 2006. Customer Commons (says here) is “a public-facing organization focused on emerging issues at the intersection of empowered individuals and the public good,” while ProjectVRM is a community with hundreds of developers and others working on new business models that start with self-empowered customers. Within both are business model ideas for journalism that have been waiting for the right time and place to try out.

But the first step for us is getting to know the people and organizations on the supply side of news here in Bloomington, where Joyce and have now lived for two years. We know some local journalists already, and would love to know the rest. If I don’t reach you first, email me at doc at searls dot com.

August 31, 2023

We Need Wide News

Bloomington, Indiana, my new hometown

How do people get news where you live? How do they remember it?

For most of the industrial age, which is still with us, newspapers answered both those questions—and did so better than any other medium or civic institution. Newspapers were required reading, delivered daily to doorsteps, and sold from places all around town. Old copies also accumulated in libraries and other archives, either as bound volumes or in microfilm reels and microfiche cards. News also came from radio and TV stations, though both did far less archiving, and none were as broad and deep in what they covered and how. Newspapers alone produced deep news.

And wide news as well. Local and regional papers covered politics, government, crises, disasters, sports, fashion, travel, business, religion, births, deaths, schools, and happenings of all kinds. They had reporters assigned across all their sections. No other medium could go as wide.

After the Internet showed up in the mid-’90s, however, people also began getting news from each other, through email, blogs, texting, online-only publications, and social media. To keep up and participate, newspapers, magazines, and other legacy print media built websites and began to publish online. Broadcast media began to stream online too. But the encompassing trend was the digitization of everything and everyone. Consumers became producers. Every person with a computer or a phone was equipped to become a reporter, a photographer, a videographer, or a podcaster. (In the 24 September 2004 issue of IT Garage, I reported that a Google search for podcasts got 24 results. Today it gets 3,84 billion.)

In the midst of all this, the local and regional newspaper business collapsed. The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post found ways to survive and continue to thrive. Many other major papers are getting along but none are what they were. Nor can they be. Today most local papers are gone or shrunk to tiny fractions of their former selves. Countless local commercial radio stations are now owned by national chains, fed “content” from elsewhere, and maintain minimized or absent local staff. Public radio has survived mostly because it learned long ago how to thrive on listener contributions, bequests, and institutional support. TV news is still alive, but also competing with millions of other sources of video content. None of its coverage is as wide as newspapers were in their long prime.

Another reason for the decline of local news media is economic. Craigslist and its imitaters killed newspapers’ classified sections, which had been a big source of income. Advertisers abandoned the practice of targeting whole populations interested in sports, business, fashion, entertainment, and other subjects. With digital media, advertisers can target tracked individuals. As I put it in Separating Advertising’s Wheat and Chaff, “Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself.” That replica cares not a whit for supporting journalism of any kind.

Eyeballs and eardrums were also pulled toward direct response marketing by algorithms rigged to increase engagement. A collateral effect was pulling individual interests into affinity groups that grew tribal as they became echo chambers favoring the voices that excelled at eliciting emotional responses. Naturally, media specialized for feeding tribal interests emerged, obsolescing media that worked to cross partisan divides—such as old-fashioned newspapers. (In the old days, papers with a bend to the left or the right isolated partisanship to their opinion pages.) Talk radio and cable news became entirely partisan operations.

So, by the time Scott Adams (of Dilbert fame) said “Facts don’t matter. What matters is how much we hate the person talking” (March 13, 2022), what Yeats poetized in The Second Coming seemed fulfilled:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

And yet, as James Fallows told my wife and me a couple of months ago, if you talk to people in small towns about anything but politics, they’re just fine. Moreover, they still work together and get things done. (Jim and Deb gained this wisdom while researching their book and movie, both titled Our Towns.)

Towns do have their fault lines, but people everywhere are held together by their natural need for the conveniences that arise out of shared necessity—for markets, medical help, education, public spaces, and each other. They also need good information about what’s going on where they live. By good I mean the kind of information they used to get before newspapers—and the daily ceremony of innocence newspapers provided—were obsolesced by the Internet.

Back in the mid-’00s, the idea of “citizen journalism” (which went by other labels) first showed up in the writings of Dan Gillmor, J.D. Lasica, Dave Winer, Jeff Jarvis, Jay Rosen, myself, and others. All of us were also concerned about the decline of newspapers. So, in January 2007, after The New York Times sold the Santa Barbara News-Press to a billionaire who fired the staff and made the paper a vehicle for her personal interests, the Center for Information Technology and Society (CITS) at UC Santa Barbara convened a charrette to discuss the future of local newspapers. The title was “Newspaper 2.0.” It was led by yours truly, then (and still) a fellow of the Center. Some of the people mentioned earlier in this paragraph were there, along with exiled News-Press staffers, educators, and other local media, including “place blogs” that were also daily newsletters. Here is a photo series from the event, which was reported on positively in several places online that now seem to be gone. (I hope some are in the Internet Archive, which I haven’t finished searching.)

I don’t know to what extent that gathering helped expand the degree to which other media made up for the failure of the News-Press (which finally filed for bankruptcy this summer, after a decade and a half of irrelevance). I do know that Santa Barbara is now something of a news commons, with lots of sources covering lots of topics. Not everything gets covered, but a lot does. I’ll know better when I get back there and talk to local reporters about it. (I can at least say that Santa Barbara is the leading public radio market in the country—or at least was when I last checked in 2019. Public stations there have widened news in the region enormously.)

Meanwhile, my full attention is here in Bloomington, Indiana. Our local newspaper, the Herald-Times, is still alive and kicking, but not what it was when giant rolls of paper were delivered by train car weekly to the back of the paper’s building at 1900 South Walnut Street, and it was the source of wide news for the town and the region.

Now it’s e pluribus unum time. There are many other media in town, covering many topics, and I’m not yet clear on how much they comprise a news commons. But, as a visiting scholar (along with my wife Joyce) at Indiana University’s Ostrom Workshop, which is all about studying commons, I want to see if our collection of local news media can become an example of wide news at work, whether we call it a commons or not. From my current notes, here is a quick, partial, and linky list of local media—

Periodicals (including newsletters and websites):

The Herald-TimesB Square BulletinThe BloomingtonianIDSBloomThe RyderVisit BloomingtonBloomington OnlineHoosleft (also a podcast)Radio:

WFHB (has local news and podcasts)WFIU (has local news and podcasts)WIUX (IU student station, has local stuff)WGCL (legacy local radio, AM & FM)WBWB (B97) (pop music, has local news, sister of WHCC)WTTS (legacy Tarzian FM music station, broadcasting from Trafalgar, on the south side of Indianapolis, with a popular local translator of its HD2 channel called Rock96 The Quarry)WHCC (local country station, has some local news, sister of WBWB)WCLS (local album rock station, has a calendar)TV:

WTTV-4 CBS (licensed to Bloomington )WTHR-13 NBCWTIU-33 PBSWRTV-6 ABC (has local Bloomington news on its website)WXIN (Fox 59) (has local Bloomington news on its website)WISH-8 CWPodcasts

NoDishesBeyond BTownUnspoken RequestsIndiana University

IU Media School(Note that every department—Sociology, Law, Sports, Medicine, Music, and many others—make and report on local happenings)Civic Institutions:

Monroe County Public LibraryMonroe County History CenterGreater Bloomington Chamber of CommerceSo my idea is to hold a charrette like the one we had in Santa Barbara, to see how those interested in making wide news better can get along. No rush. I just want to put the idea out there and see what happens.

I think one thing that will help is that nobody is trying to do it all anymore. But everybody brings something to the table. Metaphorically speaking, I’d like to put the table there.

Thoughts and ideas are invited. So are corrections and improvements to the above. I see this post, like pretty much everything I write online, as a public draft.

My email is doc at searls dot com.

I shot the photo above on a flight from Indianapolis to Houston after giving this lecture at IU. Here is a whole series on Bloomington from that flight. And here is the rest of the flight as well. All the photos in both are Creative Commons licensed to encourage use and reuse, by anybody. I have about 60,000 photos such as these published online here, and another 5,000 here, all ready for anyone to put in a news story. I bring this up because public photography is one of my small contributions to wide news everywhere. You can see results in countless news stories and at Wikimedia Commons, where photos in Wikipedia come from. I put none of those where they are. Others found them and put them to use.

August 18, 2023

We Need Deep News

Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate to prefer the latter.

— Thomas Jefferson

News is the first rough draft of history. — Countless journalists

“Breaking the News” is the title of an exhibit at the Monroe County History Center here in Bloomington, Indiana.* It traces the history of local news from the mid-18oos, when several competing newspapers served a population of a thousand people or less, to our current time, when the golden age of newspapers is long past, and its survivors and successors struggle to fill the empty shoes of local papers while finding new ways to get around and get along.

Most of the exhibits are provided by what’s left of the city’s final major newspaper, the Herald-Times, which thankfully still persists online. Archives of the paper are also online, going back to 1988. I am told that there are microfilm archives going back farther, available at the Monroe County Public Library. Meanwhile, bound volumes of the paper, from the 1950s through 2013, are up for auction.

Meanwhile, in our other hometown, the Santa Barbara News-Press is gone after serving the city for more than 150 years. The Wikipedia article for the paper now speaks of it in the past tense: was. Its owner, Ampersand Publishing (for which I can find nothing online), filed for bankruptcy late last month. You can read reports about it in KSBY, the LA Times, the Independent, Noozhawk, Edhat, and a raft of other local and regional news organizations.

From what I’ve read so far (and I’d love to be wrong) none of those news reports touch on the subject of the News-Press‘ archives, which conceivably reach back across the century and a half it was published. There can’t be a better first draft of history for Santa Barbara than that one. If it’s gone, the loss is incalculable.

Back here in Bloomington, Dave Askins of the B Square Bulletin, which reports on what public offices and officials are up to, has issued a public RFQ for a digital file repository that will be a first step in the direction of what I suggest we call deep news. Namely, the kind that depends on archives. It begins,

Introduction:

The B Square is seeking proposals from qualified web developers to create a digital file repository. The purpose of this repository is to provide a platform where residents of the Bloomington area can contribute and access digital files of civic or historical interest. This repository will allow users to upload files, add metadata, perform searches, and receive notifications about new additions. We invite interested parties to submit their proposals, outlining their approach, capabilities, and cost estimates for the development and implementation of this project. For an example of a similar project, see: https://a2docs.org/ For the source code of that project, see: https://github.com/a2civictech/docstore.

The links go to a project in Ann Arbor (where Dave used to live and work) that was clearly ahead of its time, which is now.

We also need wide news, which is what you get from lots of organizations and people doing more than filling the void left by shrunken or departed newspapers. (Also local radio, most of which is now just music and talk programs piped in from elsewhere.)

News reporting is a process more than a product, and one the Internet opens to countless new participants and approaches. Many of us have been writing, talking, and working toward Internet-enabled journalism since the last millennium. Jim Fallows (see below), Dan Gillmor, Dave Winer, JD Lasica, Jay Rosen, Jeff Jarvis, Emily Bell & crew at the Tow Center, and Joshua Benton and the crew at NiemanLab, are among those who come to mind. (I’ll be adding more.) Me too (for example, here).

Wide news, when it happens, is a commons: an informal cooperative. (The Ostrom Workshop, where my wife and I are visiting scholars, studies them.) I think we are getting there in Santa Barbara. But, as the LA Times story on the News-Press suggests in its closing paragraphs, there are gaps:

Santa Barbarans have turned to other sources as the newspaper’s staff withered to just a handful of journalists. Along with the Independent and Noozhawk, some locals said they turn to KEYT television and to Edhat, a website that relies heavily on “citizen journalists” to report on local events.

Melinda Burns, one of many reporters who left the paper after feuding with management, now provides freelance stories to many of the alternative news organizations. Burns, who has spent decades in the news business, including a stint at the Los Angeles Times, said she has seen gaps in coverage in recent years, particularly in the areas of water policy and the changes wrought by legalized cannabis. She continues to report on those topics and said she gives away her in-depth stories free to reach as many people as possible.

“It keeps me engaged with the community and, God, do we need the coverage,” she said. “The local news outlets are valiant but overworked. It’s just a constant scramble for them to try to keep up.”

Maybe it helps to know that a landmark local news institution is gone, and the community needs to create a journalistic commons, together: one without a single canonical source, or a scoop-driven culture.

I think the combination of deep and wide news is a new thing we don’t have yet. I’ll call it whole news. We’ll know it’s whole by what’s not missing. Is hard news covered? City hall? Sports? Music? Fashion? Culture? Events? Is there a collected calendar where anyone can see everything that’s going on? With whole news, there is a checkmark beside each of those and more.

Toward one of those checkmarks (in addition to the one for city hall), Dave Askins has put together a collective calendar for Bloomington. Wherever you are, you can make one of your own, filled by RSS feeds and .ics files.

At the close of all his news reports, Scoop Nisker (who just died, dammit) said, “If you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own.”

So let’s do it.

*Breaking the News is also James Fallows‘ newsletter on Substack. I recommend it highly.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers