The Personal Internet

—is not this:

A netizen isn’t just an account-holder

A netizen isn’t just an account-holderBy now we take it for granted.

To live your digital life on the Internet, you need accounts. Lots of them.

You need one for every website that provides a service, plus your Mac or Windows computers, your Apple or Google-based phones, your home and mobile ISPs. Sure, you can use a Linux-based PC or phone, but nearly all the services you access will still require an account.

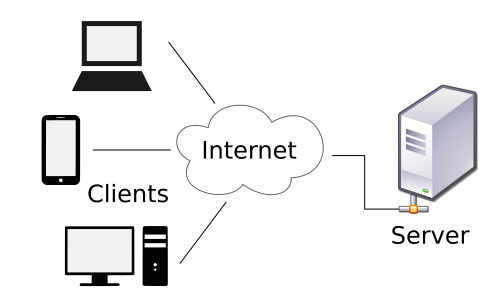

Everything that requires an account has a lock on you—for their convenience. They don’t know any other way. That’s because all the services we use in the online world operate inside a model called client-server, which looks like this:

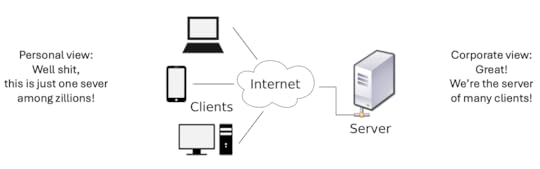

This is great for the server operator, but not for the rest of us:

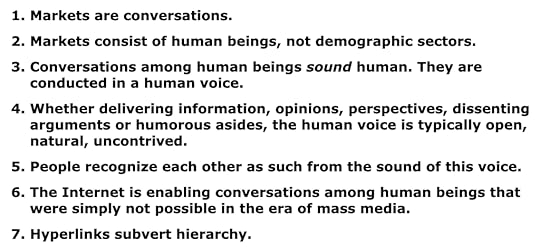

This was not the promise of the Internet described by John Perry Barlow in Death From Above in 1995 and A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace in 1996. Nor was it what Chris Locke, Rick Levine, David Weinberger, and I said in The Cluetain Manifesto‘s ‘one clue’—

—and in the 95 Theses that followed, starting with these:

Since I’ve often heard that an unintended consequence of Cluetrain was causing social media in some way, I just asked ChatGPT and Perplexity the same question: Did The Cluetrain Manifesto help start social media? The answers were roughly the same, but Perplexity provides sources, so I’ll quote that answer:

The Cluetrain Manifesto did not directly start social media, but it did play a significant role in predicting and shaping the philosophy behind social media marketing and online communication. Published in 1999, the manifesto anticipated many of the changes that would occur with the rise of social media and online conversations. (link) (link)

Key points about The Cluetrain Manifesto’s influence on social media:

Predicted global conversations: The manifesto accurately foresaw that the internet would enable powerful global conversations, allowing people to share knowledge rapidly (link).Emphasized authentic communication: It stressed the importance of companies engaging in genuine, human conversations with customers, which became a cornerstone of social media marketing (link) (link).Highlighted networked markets: The manifesto recognized that customers were becoming more connected and influential through online networks, a concept that social media platforms later embodied (link).Challenged traditional marketing: It criticized the “homogenized voice” of traditional business communication, encouraging a more authentic and conversational approach that social media later facilitated (link).Empowered employees: The manifesto suggested that companies should empower employees to engage with customers, an idea that became crucial in social media strategies (link).Recognized the shift in power: It predicted that customers would gain more influence over companies through online conversations, which social media platforms later enabled (link).While The Cluetrain Manifesto didn’t create social media technologies, it provided a philosophical foundation that aligned closely with how social media would eventually function. Its ideas about authentic communication, networked conversations, and customer empowerment became central to social media marketing strategies and practices (link) (link) (link).

Alas, we all still are seats, eyeballs, end users, and consumers, and our reach still does not exceed corporate, government, and organizational grasp, because all of those entities operate their services on the client-server model. And, so long as nearly everyone believes that client-server is the only way to go, the fact that the Internet is end-to-end beneath everything done on it remains irrelevant. Nothing in any of these (and many other) efforts before and since has done anything to change the damned Internet of Accounts:

The Rise of the Stupid Network (by David Isenberg) in 1997The Cluetrain Manifesto in book form, in 2000 and in a 10th Aniversary version (with seven new chapters) in 2010World of Ends (by David Weinberger and me) in 2003Internet Identity Workshop (by Phil Windley, Kaliya Young, and me) since 2005ProjectVRM (by hundreds of people and projects) since 2006 The Intention Economy , a book by me in 2012New Clues (by David Weinberger and me) in 2015I do, however, see hope coming from three angles.

First is self-sovereign identity, or SSI. I’ve written about SSI in many ways and places over the years, but perhaps the best is New Hope for Digital Identity, published in Linux Journal back in 2017. What SSI wishes to replace is the familiar client-server model in which you are the account holder, and two servers are the “identity provider” and the “relying party.” With this system, your “ID” is what you get from the identity provider and their server. With SSI, you have a collection of verifiable credentials issued by the DMV, your church, your school, a performance venue, whatever. They get verified by an independent party in a trustworthy way. You’re not just a client or just an account holder. You disclose no more than what’s required, on an as-needed basis.

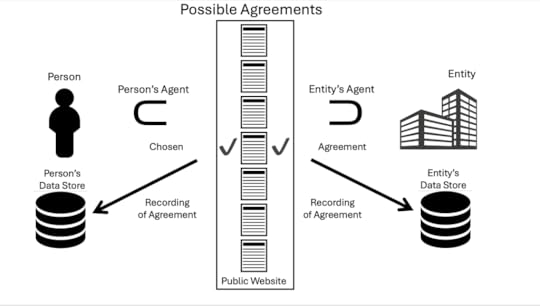

Second is contract. Specifically, terms we proffer as first parties and the sites and services of the world agree to as second parties. Guiding the deployment of those is IEEE P7012 Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms, which I’ve called the most important standard in development today. I’m the chair of the P7012 working group, which has been on the case since 2017. The standard is now drafted and moving though the IEEE’s approval mill. If all goes well, it will be ready early next year. It works like this:

Possible agreements sit at a public website. Customer Commons was created for this purpose, and to do for personal contracts what Creative Commons does for personal copyrights. The person’s agent, such as a browser, acting as the first party, tells the second party (an entity of any kind) what agreement the person has chosen from a small roster of them (again, on the Creative Commons model). The entity either agrees or declines. If the two agree, the decision is recorded identically by both parties. If the entity declines, that decision is also recorded on the person’s side.

Customer Commons has one such agreement already, called P2B1 (beta), or #NoStalking. As with all contracts, there’s something in it for both parties. With #NoStalking, the person isn’t tracked away from the site or service, and the site or service still gets to advertise to the person. Customer Commons (for which I am a founder and board member) plans to have a full list of agreements ready before the end of this year. If this system works, it will replace the Internet of Accounts with something that works far better for everyone. It will also put the brakes on uninvited surveillance, big time.

Third is personal AI. This is easy to imagine if you have your own AI working on your side. It can know what kind of agreement you prefer to proffer to different kinds of sites and services. It can also help remember all the agreements that have been made already, and save you time and energy in other ways. AI on the entities’ sides can also be involved. Imagine two robot lawyers shaking hands and you can see where this might go.

There are a variety of personal (not just personalized) AI efforts out there. The one I favor, because it’s open source and inspired by The Intention Economy, is Kwaai.ai, a nonprofit community of volunteers where I also serve as chief intention officer.

I welcome your thoughts. Also your work toward replacing the Internet of Accounts with the Internet of People—plus every other entity that welcomes full personal agency.

Doc Searls's Blog

- Doc Searls's profile

- 11 followers