Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 13

April 21, 2017

What’s YOUR best stroke count: How I found mine. And why it’s still evolving

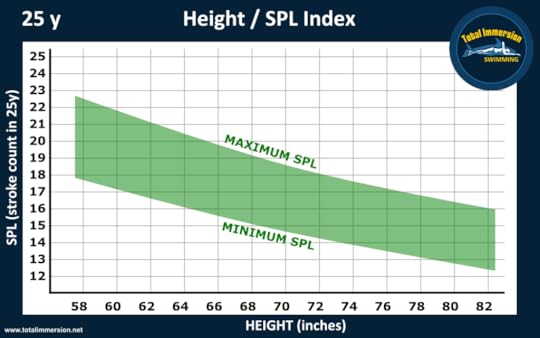

The answer to “What’s your best stroke count?” is “It depends.” As we hope to make clear with our Green Zone chart, any swimmer should have a range of efficient counts. not a single all-purpose count. But that range may evolve–upward or downward–over time. Therefore it helps to be flexible–but not complacent–about this.

I consider stroke count such an important measure that I’ve counted almost every stroke I’ve taken in pool practices and Masters races for the past 25 years. I’ve done this because Strokes Per Length (SPL) is a simple, moment-by-moment measure of Stroke Length (SL)–long recognized as the strongest factor correlating with higher-level performance.

Is it difficult to count strokes? It can be at the beginning. But if you are patient and consistent in doing it, it becomes second nature fairly quickly. For many years it has required almost no brainpower for me to maintain an accurate count, which allows me to also pay close attention to my focal points–and even remember most of my stroke count details to record in a practice log an hour or so after finishing practice.

Here’s a brief history of my SPL Journey:

1964-1972 Throughout my years on summer league, high school, and college teams I believed that a fast turnover was all that mattered in swimming fast. I never counted strokes–and never swam fast either. Recalling the windmill sensation of my stroke during those years, I’m fairly sure my average count was above 20SPL for 25 yards.

1973-1989 From Day One of my coaching career, I became convinced of the importance of longer strokes. Soon after I began to have my swimmers count strokes on certain training sets. The objective of these sets was to consciously reduce the count as a stroke-lengthening exercise. I also began to instruct them to add the time for the repeat to the stroke count to achieve a score. This was an early–though primitive–way of taking Stroke Rate into account.

These were just two, among many, modalities I used to improve my swimmers’ efficiency. I swam irregularly during this time, but had begun counting my own strokes. The lowest count I could attain for 25 yards was 17SPL, because I didn’t yet know much about streamlining. (Learn about streamlining in our 1.0 Effortless Endurance Freestyle Self-Coaching Course.)

1990-2004 As we began teaching ‘Fishlike’ technique to TI camp and workshop attendees, I gained a steadily increasing understanding of ‘vessel-shaping’ as Bill Boomer termed it. The first 10 years of my own TI practice, I worked assiduously to reduce my stroke count. It dropped steadily until in the early 2000s, I managed once (while swimming with Shane Gould in Perth, Australia) to cross a 50m pool in 26 strokes . My SPL in 25y pools was typically 10 to 13.

2005-2014 I first used a Tempo Trainer in 2004. This revealed to me that I’d been focused so intently on lowering my SPL that I had dramatically slowed my stroke rate to do so. Consequently, I had a bit of a “rut” in my nervous system, unable to swim comfortably and efficiently at tempos of 1.2 sec/stroke or faster. As a result, I wasn’t swimming very fast. But I could go long. I swam the Manhattan Island Marathon in 2002 at an average SR of 49 strokes per minute (about 1.2 sec/stroke), completing my 28.5-mile loop in 30% fewer strokes than nearly anyone else in the field.

Tempo Trainer–the efficient, and fast, swimmer’s friend.

Beginning in 2005 my emphasis shifted from maximizing stroke length to maximizing the paces at which I could swim–without forgetting that one needs both Length and Rate to achieve Velocity. The Tempo Trainer was an invaluable tool to achieving comfort and maintaining efficiency at tempos as fast as .85 sec/stroke–about 70 strokes per minute. While I only swam at this tempo infrequently, doing so made me even more comfortable at my typical racing tempo (for a mile in open water) of .95 seconds.

As a result of increasing tempo, my range of SPL in a 25 yd pool rose to 13-16. According to the Green Zone chart, this is a zone of exceptional efficiency for someone of my 6′ height.

Find your efficient stroke count range of 25y pools.

2015-2017 During the past two years, my stroke count range has increased again–mainly as a result of cancer treatments that have sapped my strength. So now my SPL range in a 25y pool is 14-17. My tempo is also down considerably, because my red blood cell count is lower than it used to be, meaning the rate of oxygen delivery to my muscles is down quite a bit. My fastest comfortable tempo at the moment is 1.2. That combination of taking more strokes and a considerably higher tempo (which means the ‘time cost’ of every added stroke is now about 1.2 seconds whereas it used to be about 1 second) is the ‘mathematical’ reason my times have slowed considerably.

At 14-17 SPL I remain within my Green Zone and have a far more efficient stroke than I did in my teens, 20s, and 30s. As this account illustrates, your stroke count can go down, then you might choose to let it rise again. It makes swimming interesting and fun and keeps your brain engaged.

Learn More

If there was any period during which I feel I overachieved, with regards to my full potential, it was between 2006 and 2011, during which I won all of my six National Masters Open Water Championships. medaled in the World Masters OW Championship and broke two USMS records. I’ve recorded many of the insights I gained then on optimizing Stroke Length and Tempo in Lesson 4 of our 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self Coaching Course. Click here to order.

The post What’s YOUR best stroke count: How I found mine. And why it’s still evolving appeared first on Total Immersion.

April 13, 2017

Swim for Health and Vitality: Finding Bright Spots Everywhere

In my last post, I promised to report on my next 1650, following the one I swam in Boston on March 11 and described in the post Can a Mile Swim Race Save or Extend Your Life. First of all, because I waited too long to enter the Colonies Zone meet in Fairfax VA, I was shut out of the 1650. So I entered the 1000-yard free with high hopes of swimming it at significantly faster paces than I swam on March 11.

To review that swim, it was practically magical. It felt better than any 1650 I’d ever swum. I paced it impeccably, and I maintained a highly efficient 15 strokes per length for nearly the whole swim. When I entered the 1000-yard event I had to guesstimate my seed time because my last 1000 free came early in my treatment and I’d lost considerable speed since then.

I looked at the results of last month’s 1650. I’d swum the first 1000 yards of that race was 16:22, but I swam the last 1000 (from 650 to 1650) in 16:08. Based on that I estimated 15:59 when I put down my seed time.

My training for two weeks after the Boston meet was highly encouraging–including my unprecedented birthday set of 100 x 100. I’d analyzed my previous 1650, finding that I averaged 15.5 strokes per 25y (62 strokes/100) and a pace of 24.3 sec per 25y. Based on these two figures (and subtracting ‘non-stroking time for turns and pushes) I was able to calculate my average Tempo at 1.28 seconds.

For the first two weeks after Boston I showed significant improvement on these measures, progressing (.01 second in tempo at a time) to feeling comfortable at 62 strokes/100 and a tempo of 1.2 seconds in training repeats up to 200 yards. But over the next two weeks, I began to experience intense neuropathy (nerve pain) in my legs, and noticeably more fatigue in the course of the day.

That seemed to take a toll on my training. I could no longer swim comfortably at those combinations of SPL and Tempo. When I attempted them I felt a general burning sensation in my muscles–a sign of shifting from the aerobic zone to anaerobic training. Since aerobic training is far better for my health, I reduced my pace.

So I went into my 1000y race on April 7 feeling far less certain of my outcome. I started the race at what felt like a very cautious and comfortable pace, yet by the 500y midpoint, I felt tired, weak and had an increasing sense of breathlessness. The final 500y felt like quite a struggle. My strokes per length increased from 15 to 17, my turns were slower and my pushoffs shorter. I felt increasingly short of breath.

When I hit the timing touchpad at the finish, the display board showed 16:19 for my lane, 20 seconds slower than I had thought I should be capable of swimming. I didn’t know my splits, but–based on how I’d felt–I was fairly certain that I’d slowed considerably in the second half of the race.

Yet I felt no discouragement or disappointment after the race, nor on the ride home with my close friend Lou Tharp. Rather I felt continuing gratitude at being able to travel to these meets, at the many old friends I meet when I attend them, at the affirmation of life that occurs every time I swim in a meet or race, and the conviviality Lou and I enjoy when traveling to meets together. We had a thoroughly enjoyable 5-hour drive back to NY with great conversation all the way to our 1 am arrival back at Lou’s house.

Life is so incredibly rich because of the presence of Masters and open water swimming events in my life that the times I may swim in events becomes very secondary. Even so I remained curious about how I’d paced (or split, as coaches say) my swim, as slow as it may have been. When the race splits were posted on-line two days later, I checked them out.

I’ve already made clear that the slower time had cast no cloud over my outlook, so it would be a mistake to say it had a silver lining. Rather I found my splits to be a noteworthy bright spot–and an affirmation of something that’s always been a strength. When I checked my splits I found that–taking away the first and last 50-yard splits–on the 36 laps between them, there was variation in my pace of less than half a second per lap. Despite how I’d struggled, as breathless as I’d felt, I found a way to maintain incredible consistency in my splits.

Which shouldn’t be all that surprising, considering the consistency with which I focus on precise pace control in my training–seeking to imprint such consistency on my brain and nervous system. I discovered that–when I experience difficulty and discomfort in a race, when it feels as if nothing is going right–my nervous system and muscles still respond as I’ve trained them to do.

This is an example of an emotionally healthy habit I’ve developed in the last 20 years, a Growth Mindset behavior that would have been alien to my in my teens. During my 50s and 60s I’ve been happy to enter races when my physical conditioning is far from ideal for an endurance event, or when I have little expectation of swimming fast. First I expect to enjoy and feel enormous gratitude for the overall experience.

And second–regardless of whether my time for, say, 1000 yards is 12 minutes, 16 minutes or 20 minutes–what I care most about is how I arrive at my final time. If I swim a well-paced 20-minute 1000, I will take great satisfaction from having done so. And considering how much my paces have slowed during the 16 months since I began cancer treatment, that’s an invaluable outlook to have.

And in a further bright spot, two days after my slow-and-struggling 1000y race I seem to have recovered my mojo in practice. On a set of 15 x 100y repeats I steadily increased my tempo from 1.25 to 1.2 seconds, while comfortably holding a count of 63 strokes/100 yards, and improving my pace from 1:37 to 1:31 per 100 yards, faster than I’d swum in the past month and feeling no hint of struggle. Now I’m looking forward to my next planned meet–Canadian Masters Nationals May 11-13 in picturesque Quebec City (it will be my first visit) and to the return of open water swimming and events shortly afterward.

The Latest on my Prognosis and Treatment

I’ve been through three treatment regimes over the past 16 months–hormone therapy, then chemotherapy, and most recently radiation therapy (administered intravenously). In each instance I had encouraging results initially but my lab markers went markedly in the wrong direction soon after. Each treatment was ended short of its planned duration due to those outcomes.

However I’m most fortunate to live near enough to NYC to be able to take advantage of the fact that there are multiple hospitals–Sloan Kettering, Mt Sinai (where I’d been treated up to now), New York, and Columbia–that are rated very highly for research and treatment of prostate cancer. Yesterday I visited a new oncologist at New York Hospital’s Weill Cornell Medical School.

Though she is quite young, she has been on the cutting edge of the most exciting and promising research advances into prostate cancer treatment. She gave me a far better understanding of my disease than I’ve had before. She found a positive in my repeated treatment failures, telling me that it indicates that I do not have an adenocarcinoma–as it has been labeled since my initial diagnosis.

She described a highly sophisticated testing program that can reveal the molecular and genetic basis of my cancer and whether it has mutated over the course of the disease. Following this analysis, they’ll be able to treat it in new ways–of which there are quite a few highly promising options.

During my visit, they drew eight vials of blood for extremely detailed analysis. The most vials that has been drawn in a previous lab visit had been three. I’ll return to her clinic each of the next two Wednesdays for further testing and a bone biopsy. I will also be able to begin my first clinical trial in two weeks. She inspired such optimism and hope that I’m quite certain I will put myself under her care.

So as the title of this post says, there are bright spots everywhere.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: Finding Bright Spots Everywhere appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 30, 2017

A Birthday Swim-to-Remember. (In fact 100 of them!)

Several weeks ago, I swam a 2-hour Sunday morning practice with the Excel Masters program at Long Island’s Nassau County Aquatic Center. I surprised myself by swimming nearly 5000 yards–the farthest I’d swum in a single pool session since my mid-50s.

While I was there the Excel coach, Lisa Baumann (a friend since I coached her in her teens over 40 years ago) invited me to take part in the club’s annual training event–100 x 100 (100 repeats of 100 yards)–on March 26. I immediately began giving it serious consideration. To commit myself further, I invited a few friends to join me.

I thought that a meaningful goal would be to swim 66 x 100 (30% farther than I’d swum on that Sunday morning) to celebrate my 66th birthday, on March 25. I didn’t seriously consider swimming 100 x 100 (5.6 miles of 100y repeats) since I’d never attempted it previously–even when in full health. But I told several people that if all was well when I reached 66, I’d carry on with an open mind.

Fellow TI Coach Lou Tharp and I shared a lane with Larry Maraldo and Michael Pasquale of the Excel program. We agreed to swim on intervals between 1:50 and 2:00 per 100. Lisa’s workout plan made it easier to stay engaged by breaking 100 repeats into 5 sets (and each set into 3 or more sub-sets) with the opportunity for periodic breaks for fueling up, hydrating, or visiting the rest room.

Still feeling fresh after 55 x 100: Terry, Larry and Lou front; Michaal rear.

30 x 100 (10 each on 2:00, 1:55. 1:50)

25 x 100 (1 easy, then 8 each on 1:50, 1:55. 2:00)

20 x 100 (1 easy, 1 fast, 1 easy, 2 fast, 1 easy, 3 fast, 1 easy, 4 fast, 1 easy, 5 fast)

15 x 100 (6 on 1:50, 5 on 1:55, 4 on 2:00)

10 x 100 (4 on 1:50, 3 on 2:00, 3 on 2:10)

I made my own plan to swim:

Set #1 at 58 strokes per 100 quite easily. My average pace was 1:40 to 1:41. This was 4 fewer strokes/100 than than my recent 1650, and 2-3 sec. slower.

Set #2 at 60 strokes per 100 a bit faster. I averaged 1:38-1:39. Fewer strokes but the same pace as my 1650.

Set #3 I took 60 strokes on the easy 100s, 64 strokes on the faster ones. I held 1:35 to 1:37 on the faster 100s. Two more strokes/100 and 1 to 3 sec faster than on my 1650.

This would make 75 x 100, farther than my goal. If I made it that far, I’d assess whether to attempt the final 25 x 100.

I had no solid food prior to starting (I drank a protein shake on the drive to Long Island.) And I took no sustenance nor hydration during those 75 x 100, but I felt neither thirst nor hunger, reflecting how economically I had swum on them.

I felt I’d accomplished enough already and was a bit leery of swimming farther at the risk of needing a long recovery period. But Lou said he was game to continue so I said I would too. He got out to fill a bottle with a muscle-recovery drink. We each took several sips.

On the final 25 x 100 I dropped my stroke count to 60/100 and let my pace ease to an effortless 1:42 to 1:45. We sipped from the bottle between sets. When we finished, Lou and I both felt elated at achieving something significant for the first time at age 66 (Lou is a month older than me.) It had taken us about 3.5 hours. We celebrated in the hot tub.

What made this a birthday swim-to-remember was:

Accomplishing something I’d never attempted in 50+ years of swimming. (I wonder how many swimmers with stage IV cancer have done this.)

Doing every repeat (yes, all 100) with clear focus and purpose. I made a plan–related to my recent 1650–and executed my plan.

Finishing with no fatigue, and nota hint of joint or muscle soreness.

Feeling strikingly energized in body, mind, and spirit for the next 10 hours until bedtime. In fact I felt better sustained physical energy than on most days!

Once again, swimming provides an illness-free zone, where I feel boundless and vibrant health. Not only during, but for hours after as well.

May your laps be as happy–and purposeful–as mine.

The post A Birthday Swim-to-Remember. (In fact 100 of them!) appeared first on Total Immersion.

Meet TI Coach Todd Erickson. His clients say that they never see him taking a breath.

(We would like to introduce you to our worldwide network of Certified TI Coaches. The people we profile here have invested a lot of time and effort into their practice as swimmers and coaches. We hope you enjoy getting to know them and hearing about their strengths, challenges, and accomplishments).

Todd Erickson

St. Antonio Texas, USA

Family Summary: Married to Nancy, my High School Sweetheart (that’s 47 years), my companion and training partner/coach. Two grown children: Garth, his wife Carolijn (from Suriname) and their two girls, Isabella and Elsa; Kate (also a TI Coach and running summer children swim program at Aviano AB IT), her husband Oushan and their son Gunnar who all live in Sacile IT. And our newest member of the family, Floki, a 14 week old Portuguese Water Dog, my newest training partner.

What made you decide to become a TI Coach?

I had been swimming my entire life and coaching off and on during my Air Force Career. Upon retiring in 1996 I started coaching High School Boys and Girls Swimming and Water Polo. I came across TI in a National High School Swim Coaches publication and it made me delve deeper into it. TI dove tailed perfectly with what we were using/teaching. As I began to swim for myself again in 2003 I turned again to TI, as I had seen its’ success with beginning and advance high school swimmers. The stroke had changed and was closer to my old technique that had been corrected by unknowing coaches. I fell in love with the new technique and philosophy of Kaizen – always striving to improve to be better every time I got in the water. With that renewed inspiration, and after several jobs coaching high school, I decided to come back to my first passion of swimming and get certified in TI so I could teach adult on-set swimmers how to swim easily and enjoy the water as much as I do.

Tell us about your best swim.

I am not an overly experienced open water swimmer. I did a baby step with the SERC annual Alcatraz swim in 2009. I started serious long open water swims in 2011 with the Waikiki Rough Water. My goal is to do at least one to two long open water swims a year. I participated twice in the 8 Bridges Swims in the Hudson River, NY (2014, 2016). They are fantastic, fun and well run by Dave Barra and Rhondi Davies. However, to get to your question, I’d have to say my English Channel attempt last summer was the best I have done in open water. Even though I was a mile short of completion, it was the furthest swim for me to date (approx. 35 miles) and longest (14.5 hours) in 62-63 degree water. I would not have even considered this swim before TI, which gave me an efficient stroke and gave me the confidence in my swimming ability

Tell us about kaizen opportunities you’ve identified in your own swimming.

There were really two that jumped out at me. First learning the 2 beat kick and how it timed the entire stroke even when I purposely revert to a 6 beat kick for pool competition. In over 50+ years of swimming, no coach had ever explained the purpose of the kick to me other than kick as hard and fast as you can. The other was pressing the buoy. This direction had always escaped me and I had finally given up on trying to understand what they meant. It wasn’t until practicing skating and opening the axilla that I finally felt this press and it was a WOW moment.

Are there any TI Coaches who you find inspiring?

Well there are two.

David Cameron. He has such a great program and facilities with his association with the YWCA and then his TI Coaching Business and his constant travel to do clinics world-wide.

The second would be Marjon Huibers. She brought a wealth of swimming knowledge and swimming safety knowledge with her to TI and with her marketing background I have witnessed a tremendous amount of growth of TI.

The post Meet TI Coach Todd Erickson. His clients say that they never see him taking a breath. appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 24, 2017

Can a Mile Swim Race Save–or Extend–Your Life?

Today’s post weaves together strands from two posts from last week What is Neural Training and Why do it and A Rare Peek into a Champion’s Mind (Katie counts strokes!) which also provided a peek into my mind, as I raced a mile (1650y) in the pool on March 11.

Despite having just 2 weeks of practice following a 7-week layoff, my 1650 felt absolutely exquisite. I never fatigued. I swam the middle third (550y) faster than the first third–and the final third faster yet. I maintained a highly efficient count of 15-16 SPL throughout. I also maintained laser-like focus, and experienced Flow nearly the entire time, meeting every goal I’d set for myself.

I’ll swim my next 1650 two weeks from today, on April 7, four weeks after my last. Despite that short time frame, I’m highly confident I can significantly improve on my last performance.

Before talking about performance, I want to emphasize how essential these races are to my all-fronts, give-no-quarter battle with cancer. There’s incontrovertible evidence that regular exercise doubles survival rates for those with cancer. As typical survival time for men with my kind of cancer is about 30 months, I’m literally fighting for time as each year I can add to survival will bring promising advances in treatment.

Second, I’m convinced that—despite swimming significantly slower than a year ago—enthusiastic pursuit of performance goals gives a measurable boost to my physical and mental health compared to simply getting regular exercise. I continue to train for, and race the 1650 not only because I have cancer. In the last decade, Kaizen–devoting every practice to making measureable improvements—has come to define me as much as anything else.

And, on this count, neural-oriented training has become absolutely vital. So let’s review the differences between two modes of training—traditional aerobic training and cutting-edge neural training, which I firmly believe is the wave of the future.

Metabolic or aerobic. Swim coaches call this ‘energy system’ training (EST). EST is organized around duration of work, heart rate, and work:rest ratio, combinations of which put you into a particular ‘energy zone.’ Put more simply: How long and how hard must you swim . . . in order to swim longer and harder?

EST is overwhelmingly embraced by swim coaches—age group, school, college, and Masters–and consequently by tri coaches too. Seeing the ‘experts’ train this way, those without coaching tend to use a version of EST.

Here’s an irony: While there’s reasonable correlation between energy system measures (like VO2max) and performance in land-based sports, there is no correlation, and often a negative correlation between these measures and performance in swimming. Yet swim coaches follow energy system protocols more slavishly than any others–some with a high degree of organization, most in a much less organized manner.

In EST, there’s never a guarantee that quality neural training takes place. And in the less-sophisticated approach most take—swim harder and harder, longer and longer–the neural impacts for the great majority of swimmers is strikingly negative–i.e. ‘practicing struggling skills.’ It also tends to be one-size-fits-all and offers little opportunity for meaningful feedback.

Neural Neural training focuses on two things:

Honing proven-critical skills–Balance, Streamline, Integrated Movement, Breathing; and/or

Working the formula Velocity = Stroke Length x Stroke Rate. (V=SL x SR)

In either case, the swimmer strives to incrementally improve and imprint a specific element of one of those measures. Both are skill oriented, completely personalized, and much more precise. Aerobic training still ‘happens,’ but is specific to the swimmer’s current level of neural development–i.e. the skill level they possess at the moment.

The swimmer works patiently on a level of task difficulty to which they are currently adapted, striving to strike a fine balance between the skills they currently possess and the difficulty of the task. a threshold for moving to the next level. Unlike the measures for energy system training, those for neural training (SPL, Tempo, Duration, RPE) are completely transparent and known to the swimmer at every moment.

More contrasts:

Neural training includes elements that teach Mastery habits, follow the principles of Deliberate Practice–and can even improve mental acuity as we age. Energy system training violates nearly all those principles.

Neural training focuses on capabilities that are limitlessly improvable. Energy system training adaptations are limited by genetics, age, and athleticism.

Neural training also focuses on capabilities that can adapt at lightning speed, often within 15 minutes. Energy system adaptations occur at a comparatively glacial pace—seldom less than several months.

Finally, neural training puts the world’s most powerful organ–the human brain–at the center of its focus. It focuses the brain on concretetasks–the type which it has spent millions of years adapting. Energy system training puts billions of neurons to sleep, and focuses on tasks that are mostly abstract. This is because most swimmers experience EST as tedious rote repetition . . . with no evident purpose other than to make you sweat.

Preparing for my next 1650

My goal for my next 1650, two weeks from today, is to experience it just as much as a work of art—an experience I’ll remember with appreciation for years—while also swimming 30 seconds faster, if not more.

If I were training aerobically—focused only on the distance and time of my repeats–this much improvement in a matter of weeks, especially while enduring cancer treatment, would be out of the question. But with neural training, it feels eminently achievable—even inevitable!

Here’s my process:

During my last 1650, I counted strokes on every lap. This may seem hard to some but wasn’t, because (1) I count strokes on every lap of training; it’s become a habit almost like breathing; and (2) A good friend, Lou Tharp, counted laps for me. (And I counted for him.)

The meet organizers provided my final time and all splits.

These two pieces of information allowed me to calculate a third critical data point—Tempo.

My average stroke count per 25y was 15.5 (62 strokes/100).

My average pace per 25y was 24.3 sec (26m47s divided by 66 lengths).

My stroking time (lap time minus estimated turn-and-pushoff time of 4.5 sec) was 19.8 sec.

My average Tempo (stroking time/# of strokes or 19.8/15.5) was 1.28 seconds.

Central Pattern Generation

That combination of 15-16 SPL at a tempo of 1.28 seconds represents a specific movement pattern in my central nervous system (CNS). That 1650 felt so easy and pleasurable because my brain and CNS were so well adapted to that pattern. I.E. They activated–and turned off–just the right muscles in just the right sequence. As a result I consumed minimal oxygen while doing it. That’s the secret to swimming an impeccably paced distance event on only two weeks of practice.

In the four weeks between swims, I’m focusing the bulk of my training on adapting my brain and CNS to a new pattern, actually a series of new patterns, in the tiniest of increments.

A little more math illustrates.

On March 11, I took approximately 1203 strokes to complete the 1650 (15.5 avg SPL x 66 lengths = 1203.

On April 7, every hundredth (.01) of a second increase in tempo will result in a savings of 12 seconds (.01 second x 1200 strokes).

At 1.27 tempo, and the same stroke count, I’ll save 12 seconds.

At 1.26 tempo, I’ll save 24 seconds.

At 1.25 tempo, I’ll save 36 seconds.

And each of these combinations represent a unique new pattern in my CNS. The neuroscience term for this approach to training is Central Pattern Generation.

I have a better term. Because I go to the pool each day with a galvanizing sense of mission and clear purpose, I call this Nirvana.

As of today, I already feel very relaxed at 62 strokes per 100 and 1.2 tempo on sets of 100y repeats. I feel confident that in two weeks time I can nudge that effortless feeling down a few more ticks in tempo—at least to 1.17.

Someone training aerobically would be trying to work harder and longer. In contrast, each time I push the left button on my Tempo Trainer—increasing tempo by .01 second—I’m focused on recapturing the sense of swim-all-day ease I enjoyed at the previous tempo.

If this seems like a daunting amount of math, it probably would be if you tried to leap right into it. But it’s really simple arithmetic, once you’re familiar with the formulas I outlined above. And to start, all you need to do is count those strokes.

And for me this is far more than math. I’m convinced it’s literally a lifesaver.

In two weeks, following my next 1650, I’ll let you know how my ‘math problem’ worked out.

The post Can a Mile Swim Race Save–or Extend–Your Life? appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 17, 2017

A Rare Peek into a Champion’s Mind (Katie counts strokes!)

Last night (Thursday, March 16) at the 2017 Women’s NCAA Championship, “the best athlete in the world” Katie Ledecky broke her own personal best (4:25, set earlier this month at PAC 12 Championships), NCAA record, and American Record in the 500 yard freestyle by over a second with a time of 4:24.06.

Following the race, in this video, Katie explains why she’s not quite satisfied with her record-breaking performance. The interview contains insight into the mind of a champion that is absolute gold for any swimmer interested in achieving their own personal best—whether it’s completing 500 yards nonstop for the first time, improving on one’s personal best for a mile, or simply experiencing more engagement, and enjoyment and sense of purpose in practice.

What this video reveals:

Katie counts strokes. If she has the presence of mind to count during a race, she unquestionably counts on a routine basis in practice.

Her race plans include stroke count. At 48 seconds, Ledecky says her planned 14-SPL count crept up to 15 on the 2nd lap . . . and that she couldn’t get it back down.

Even the world’s best athlete can get rattled. Later in the video she reveals that “the excitement of the meet got to me.” That’s reasonable, considering it was her first NCAA final, as a freshman. Even a veteran of many high-pressure Olympic and world-championship finals (both oriented to individual performance) can get a little bit caught up in the even more adrenaline-fueled environment of a team championship meet like NCAA’s.

Stroke counts are critical to efficient pacing. Though her time of 4:24.0 was the fastest ever, her splits were not ideal. She swam the first half in 2:10 and the second half in 2:14, a 4-second differential. Her world records have been split much more evenly. No doubt the extra stroke per lap–so early in the race–figured into that. If she’d gone to 15 SPL in the second half, her pacing would have been more even. Listening to her reflections on the race, I’m sure it’s a mistake she will not repeat.

And My Latest Race

As promised in last week’s post, here’s a report from my latest race, 1650-yards at the New England Masters Championship last Saturday. You’ll note that while my pace was far slower than Katie’s (she’ll swim the 1650 at NCAA’s tomorrow with many expecting her to become the first woman under 15 minutes; in my case it was the first time in 50 years I went over 26 minutes), like Katie, I had a race plan in which SPL was a key element and actually exceeded my stroke count goals.

My 1650 felt just exquisite and considering that I only had 2 weeks of practice following a 7-week layoff, about as good performance-wise as could be expected.

I felt somewhat poorly from the time I awoke until I got in the pool, but once I began warmup felt much better. I warmed up for about 30 minutes, super-easy at first then rehearsing the way I hoped to feel for the first 60 of 66 lengths.

My goals for the race were to stay efficient, pace it well–being mindful of how much physical conditioning I’d lost during the 7-week layoff–feel fantastic, and stay focused.

When the race started I felt just as I had in tuneup (no surprise–that’s the point of tuning my nervous system and sensory faculties). I counted my strokes every lap and consistently swam 15 SPL on odd lengths and 16 on even. (Could there have been a current?) This is nearly 2SPL lower than I’ve been able to hold during a 1650 in the last two years. I felt silky smooth the whole way. I can recall only 3 turns out of 65 on which my timing was a little off. I never felt the breathlessness that is common during this race.

My splits for the three 550s were 9:01-8:58-8:47, while holding my stroke count consistent.

And finally I was keenly focused for every one of the 1607 seconds the race took, and experienced Flow for virtually all of it.

While it was my slowest 1650 ever–as a work of art, it felt like my best ever.

Today is your lucky day. Two blogs (Read What Is Neural Training and Why Do It) plus an unprecedented St Patrick’s Day sale (because of my Irish roots) on all TI videos and our Self-Coaching Courses. Our 1.0 Effortless Endurance Freestyle course teaches you how to achieve your most efficient stroke count. Our 2.0 Freestyle Mastery course, teaches you how to combine Tempo and SPL to achieve your best pace ever. Available today for 40% off the normal retail price. If you already ordered one, today’s an ideal opportunity to order the other. Use coupon code LUCKY2017 at checkout!

The post A Rare Peek into a Champion’s Mind (Katie counts strokes!) appeared first on Total Immersion.

What is Neural Training and Why do it?

In September 1988–nine months before the first Total Immersion camp–I heard Bill Boomer, who would become my most influential mentor, talk at a coaching clinic. Two sentences he spoke that day remain core beliefs for TI nearly 30 years later. One was on the value of ‘vessel-shaping’ over ‘engine-building.’

The second was: “Conditioning is something that ‘happens’ while you practice skills.” That was the first time I’d ever heard another coach state a principle that has turned out to be as important as any other in the TI Method.

Skill-oriented training should take precedence over aerobic-oriented training.

In 2005, I contacted Jonty Skinner for advice on how to achieve some quite lofty goals the following year, when I entered the 55-59 age group. At the time, Jonty was Performance Science Director for USA Swimming’s elite program, and—in my estimation—one of the keenest and most progressive thinkers in the world of swimming.

Like Boomer, Jonty pronounced a principle for performing at your best. He said “Aerobic conditioning may win the workout, but neural conditioning wins the race.”

I immediately grasped what he meant. In college, we swam over 6000 yards and two hours in our daily workouts. In my races—the longest on the college dual-meet program I swam 500 or 1000 yard, or between five and 10 minutes. All other races were much briefer—as little as 22 seconds. The requirements for success in racing must be very different from those for working out.

I distinctly recall that our workouts were designed mainly to help us work out better, not to race our best. How to blend aerobic and neural training in a single practice is complicated and a topic for another blog—or several. However, the connection between Boomer’s statement of principle and Jonty’s is this.

Any skill is the result of an electro-chemical signal traveling from the brain, via the nervous system, to a group of muscles. To refine and encode that skill—make it impervious to fatigue, loss of focus, or the adrenaline-fueled atmosphere of a race—one must perform it in an exacting manner, thousands of times. Each repetition makes the neural wiring a bit more robust—meaning ‘signal strength’ is greater when it reaches the muscle.

Sub-optimal repetitions—those that are even a little bit off your best–not only fail to advance your neural conditioning. They actually degrade it, meaning you must work that much harder and longer to achieve your performance goal.

Neural-oriented training is always conscious of the skill you’re trying to improve or encode and employs unique principles, protocols and forms of feedback to keep you on course. Most of the time, the skill is a mini- or micro-skill, a tiny but critical component of a larger skill.

In contrast, aerobic training is designed to make you work harder and longer, trying to develop the cardiovascular ‘plumbing’ to . . . work yet harder and longer. In other words, just like the training I did nearly 50 years ago in college.

TI training methodology and programs are based on neural training principles. Other training programs—youth, school and college, Masters, and triathlon specific—are virtually all based on aerobic training principles.

Let’s examine the differences further and investigate how to train your brain and nervous system.

Training for the 21st Century.

Aerobic training is based on research conducted between the 1940s and 1970s on how the body metabolizes oxygen and glycogen into muscle fuel, and eliminates waste products—dependent on work intensity and duration. It essentially treats the body as a complex chemistry set.

This research—and the training based on it—seldom looked at efficiency measures. The core elements of aerobic system training—how far to swim, at what speed, and on what rest interval–remained little changed in over 50 years—from before I was in grade school until today.

The possibility of neural-oriented training first received mention during the 1980s, as in Boomer’s 1988 clinic talk. But it was the development, in the first decade of this century, of advanced tools for observation of changes to brain structures–fMRI and PET scans—that permitted research which led to far sharper definition of neural training protocols.

Rationale for Neural Training

Swimming is a skill-oriented activity. According to Mike Joyner MD, director of human performance research at the Mayo Clinic, performance at the elite level—think Katie Ledecky–swim performance is determined 75% by skill and only 25% by aerobic conditioning. At the novice to intermediate level—you, me and 99.99% of everyone else–Mike estimates the contribution of skill to performance at closer to 90%.

Energy is an incredibly precious resource. DARPA–the Pentagon’s research arm–estimated the energy efficiency of uncoached swimmers at just 3%. Elite swimmers convert just 10% of energy into forward motion. Even the amazing Katie diverts 90% of her energy into moving water around and other forms of waste! Thus, the most logical focus of training—for elites as well as the rest of us–is to reduce energy waste, rather than continually “top up” a seriously leaky tank of muscle fuel.

Speed is not a product of how hard you work or how fast you stroke. Rather it’s a ‘math’ equation: Velocity = Stroke Length x Stroke Rate, or V=SL x SR. In that equation Stroke Length is the foundation; Stroke Rate is a ‘trading chip.’ Creating an ‘unbreakable’ SL foundation–and effectively trading SL for SR to maximize speed, while minimizing fatigue—is an exacting skill developed primarily by neural-oriented training.

Benefits of Neural Training

Converts generic workouts into precise and personalized training. Minimizes wasted time and effort. Maximizes sense of engagement and purpose.

Completely transparent and measurable. While working toward aerobic development, you never know how much you’ve achieved, nor when you have ‘enough.’ Nervous system training employs simple metrics that let you know exactly how you are progressing. Seek incremental, measurable, week-by-week progress in those metrics.

Can occur at lightning speed. While significant change in aerobic-system capacity takes months, measurable adaptations of brain and nervous system can sometimes occur in as little as 20 to 30 minutes.

Protocols of Neural Training

Always focus on improvement. The goal of neural training is never to get in a certain number of yards, or test your tolerance for hard work or pain. It’s always to be a better swimmer at the end of the session.

Set up ‘smart feedback’ to measure improvement. In traditional training, the primary—and often only–measure of performance is time. In neural training, time is but one of several revealing measures. The others include SPL or strokes per length (the simplest measure of Stroke Length); Tempo—another term for Stroke Rate (measured with precision by a Tempo Trainer). You must employ at least two measures—e.g. SPL + Time; Tempo + SPL; Tempo + Time—to have a complete understanding of how you performed during a swim or set, It may seem complicated at first, but quickly becomes second nature with practice.

During practice, focus on finding the easiest way to perform a task or achieve a goal—rather than on testing how hard you can work. Remember, the biggest payoff from training is in reducing energy waste–not topping up that leaky fuel tank.

Sample Neural Training Set

After a brief warmup, swim a short ‘benchmark’ set of 3 x 50. Count strokes and take time. Add stroke count to seconds for a SWAM Score. E.G. 45 strokes + 50 seconds equals a score of 95.

Swim several series of 4 to 8 x Focal Point 25s–e.g. weightless neutral head; quieter entry; less kick. On these, your task is to devote your entire attention to a single, narrow aspect of technique. After each 25, assess both how close you came to the feeling described and the quality of your attention. (I.E. Make your mind work as hard as your muscles.)

After completing the Focal Point series, choose your favorite Focal Point, or sensation—or try to blend two or more. Repeat the benchmark set of 3 x 50. Your goal is to match, or improve, your score, while expending less effort.

May your laps be as happy—and purposeful—as mine.

Today is your lucky day. Two blogs (Read A Rare Peek into a Champion’s Mind) plus an unprecedented St Patrick’s Day sale (because of my Irish roots) on all TI videos and our Self-Coaching Courses. Both of our Self-Coaching Courses, 1.0 Effortless Endurance Freestyle and 2.0 Freestyle Mastery, are also the best courses ever created in Neural Training. Available today for 40% off the normal retail price. If you already ordered one, today’s an ideal opportunity to order the other. Use coupon code LUCKY2017 at checkout!

The post What is Neural Training and Why do it? appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 10, 2017

How Mental Endurance Improves Physical Performance: A Primer

Our recent Triathlon Swim Camp (March 1 to 5 in St Petersburg FL) offered two instructional sessions each day. The camp featured six 2-hour pool practices plus four 90-minute open water practices. The first three pool practices—morning and afternoon on Day 1 plus the following morning—were technique-intensive; the next three blended technique with introduction to TI Smart Speed training methodology.

During our 1-day Effortless Endurance Workshops, instruction relies heavily on technique drills, with coaches providing a great deal of hands-on guidance in the water for every participant. With the luxury of far more coaching time at the Tri-Swim Camp, we taught almost entirely through Whole Stroke with Focal Points. We had coaches in the water at each session, but their hands-on assistance was more selective—directed where a camper struggled with a particular mini-skill.

The whole-stroke/minimal-drill approach to learning can work equally well. Every TI student should employ it at some point. Drill-intensive learning accelerates the process, but should always be followed by, well, a lifetime of Whole-Stroke Focal Point practice. Anyone can start with whole-stroke practice and achieve mastery of TI technique, but it places considerable demands on the student’s strength of focus—and mental endurance.

This was reflected in a comment by Tri-Swim camper Art Mannarn midway through the morning of Day 2, as we layered breathing-skill focal points over previously-taught focal points for Balance and Streamlining. This can be an especially challenging moment in the learning process, as breathing is the most likely activity to disrupt body position and shape.

While taking a break between practice reps, Art exclaimed, “Wow, this is mentally exhausting!” This led me to ponder the nature of mental stamina. It turns out that we develop mental endurance almost exactly as we do metabolic (or cardiovascular) endurance. And since mental endurance is the keystone, it’s important to understand it. So here’s a quick primer.

Fuel Supply

The brain runs on exactly the same fuel as the muscles—oxygen and glycogen. And there’s great symbiosis between physical and mental activity: In several experiments, research subjects were asked to solve simple mental problems—memorization, reasoning, or calculation. They did so first in a rested state. They then took a test of similar difficulty after 20 minutes of aerobic activity. A high percentage of subjects raised their scores following exercise. Because training increases circulation, the brain—like the muscles–receives an increased supply of energy during exercise.

The Effect of Work

The popular phrase “The mind is a muscle” is more true than most of us know: The brain and muscles both respond to work—or exercise—in the same way. The muscles become larger and develop a better network of capillaries to deliver energy through the bloodstream—and take away the byproducts of work. This is also true of the brain. Advanced scans—fMRI and PET scans—show increasing mass in areas of the brain that have been made to work harder. This reflects an increase in the gray matter that performs the motor control, sensory perception, and decision making that is critical to building new skills. And the white matter which connects one region of the brain to others, making those new skills easier and more fluent.

Increasing Efficiency

When muscles perform work, they increase in size. By adding more motor units to a muscle or group of muscles, the muscle can perform a given task—e.g. lifting a 25-lb weight—with more ease. When the brain performs work, that region of the brain not only increases in size, increasing the number of neurons available for the activities described above. Each new rep of a task–for instance integrating a new breathing skill with a recently-learned body position skill—results in two exciting changes to the brain:

The brain develops more robust neural networks (by adding neurons to the circuit which directs the skill) that carry the signal to the muscles performing the task. A stronger signal leads to more consistency—and fewer errors–in that movement.

The brain also ‘learns’ the task—becoming more precise in turning on just the right combination of motor units (and turning off those that need to relax). This reduces the amount of muscle tissue needed to perform the task effectively.

Both decrease energy cost, meaning ‘precious’ energy can go farther.

Mental Endurance

So, mental endurance looks a whole lot like physical endurance. As you do more repetitions of a specific task, the muscles involved in performing it gain in size and blood supply, allowing them to perform the task more times before fatigue. At the same time, the brain develops in ways that mean it gets better at the motor control, sensory perception and decision-making necessary to achieve mastery of the skill—and makes the working muscles operate more efficiently. And these adaptations occur many times faster in the brain than in muscle. So there’s a strong case for training that targets the brain first and muscles second.

Tomorrow’s Race

Tomorrow morning (Sat March 11), I’ll swim the 1650y (1500m equivalent) at the New England Masters Championship in Boston. I’ve swum this event with greater frequency since my cancer diagnosis. For nearly 50 years, I’ve used it as my primary gauge of my current swimming speed. And especially over the past year, registering to swim in one brings a pleasant sense of urgency and meaning to my practices.

Two weeks ago, I resumed swimming after a 7-week layoff required for a nasty gash in my lower left leg to close. I described my first day back in the water in the blog How to Resume Swimming After a Layoff. My goals on that day were to experience the ‘deliciousness’ of being back in the water and to measure what I was capable of. I found that I could swim 200 yards in 16SPL and times ranging from 3:40 to 3:35 (1:47 to 1:50 per 100y). With my 25y stroke count and pace per 25y, I was able to calculate my tempo at 1.28 sec. per stroke.

In the two weeks since, I’ve patiently improved my pace and increased my tempo at a 16 SPL stroke count. At every moment, I focused on ease—on feeling the very controlled effort I must maintain for most of tomorrow’s race to maintain a steady pace for 66 lengths in a state of compromised physical conditioning.

Yesterday, in my final practice before the race, I did the following set with a Tempo Trainer, while also keeping track of strokes per length and my time for each swim.

14 x 100 on an interval of 2:10/100. I did two each at tempos of 1.27, 1.26, 1.25, 1.24, 1.23,1.22 and 1.21. I focused on keeping my stroke count consistent (striving to avoid added strokes) while swimming with as much relaxation possible.

By keeping my stroke count consistent, while incrementally speeding up tempo (.01 sec every other 100), I saw my 100y pace improve gradually from 1:38 to 1:35—despite making no effort to swim faster. Instead, I simply focused on executing strokes of consistent quality and ease as the tempo got faster.

I finished this 1800-yard set by swimming 2 x 200 at 1.2-second tempo, doubling repeat distance while increasing tempo by another .01 sec. Again, I was able to hold 16 SPL. Consequently, my 200y times were 3:10 and 3:11.

This is a pace improvement of 9% in just two weeks, illustrating how quickly the brain can adapt to training which targets it. I could not have made even a fraction of that much improvement in my aerobic endurance in such a short time frame. But mental endurance can improve with lightning speed.

In next week’s blog, I’ll write more about Mind-Body training that targets brain and muscles together.

Improve your ability to build mental endurance with our downloadable 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course. Fourteen short videos illustrate the skill-building drills and skills to be performed in a series of logical steps. The companion workbook provides detailed guidance on how to use Focal Points for each step.

The post How Mental Endurance Improves Physical Performance: A Primer appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 3, 2017

Endurance: Wow, It’s Complicated!

One week ago today, I recorded my second interview with Rich Soares and Bill Plock of Mile High Endurance. Our topic was What Does Endurance Mean? I opened the discussion by asking the hosts for their definition of endurance.

Bill said, since becoming an endurance athlete, he has subscribed to Ellen Hart Peña’s description of endurance as a ball of string. The string represents energy needed for effective muscle function. When you begin an endurance event, you send the ball rolling toward a distant wall, representing your finish line. Your goal is for the string to run out just as it reaches the wall.

I like that analogy as well. But to illustrate the complexity a swimmer faces, let’s consider three different ways to swim 1500 meters – in a pool race or time trial, in an open water event, or as the first leg of a triathlon.

When swimming a 1500m event in the pool the ball of string analogy is quite apt. You want to have enough energy to be going with a full head of steam as you reach the finish, yet have nothing left as you get there. But even with a lap counter to let you know how much remains, it’s extremely challenging to make that string reach the wall.

Most athletes start too fast, and the string must be stretched more and more—often to the breaking point. Stroke length and/or stroke rate fall off markedly in the middle and last half and pace slows markedly. One needs highly developed pacing skills to roll that string out evenly for the entire 1500.

In a 1500m open water event, the goal is the same–run through the finish line chute having spent your energy wisely and nearly entirely. But without distance markers along the way, it’s very difficult to gauge. Even when I’ve swum quite well and fast, I’m generally far fresher at the finish of an OW race than at the end of a pool race and happily so. In part, this is because there are no turns, meaning you make little use of the body’s largest muscle groups—thighs and glutes—and because you don’t experience the oxygen deprivation of being underwater for as many as 65 turns and pushoffs.

In a 1500m triathlon swim the goal radically different: The smart triathlete, wants to have rolled out as little of the string as possible when you complete the swim leg, because that string will produce far more speed (relative to each discipline) on land than in the water.

This means that the best training for each of these examples will differ in important regards than for each of the others. I participate in the first two, yet my training during the colder months—preparing for 1500m/1650y pool races—undergoes some significant changes during warmer months preparing for open water events of 1500m or longer.

Training for Economy

Host Rich Soares said that the longer he’s been an endurance athlete, the more he’s come to appreciate a highly nuanced definition: The smart athlete focuses on training for economy of motion and aerobic efficiency as much as for work capacity. In other words, train to reduce the demand side of the energy equation, rather than maximize the supply side. Seek the least amount of energy expenditure for the greatest amount of performance—and be grateful to have string in reserve as you cross the finish line.

Additional topics we discuss on this podcast include:

How much does land endurance help swimming and how much can swim endurance help land endurance? Does the training I do on a bike help my distance swimming ability in any way?

How much time must a triathlete devote to swim training to optimize their tri-swim?

How many hours of training does it take to increase bench press by 10%, run or cycle distance or speed by 10%, swim distance or speed by 10%?

How to Swim Faster in an Ironman—and Feel Amazing

Finally, there’s a great exchange where Bill reveals that he’s hit a wall with his swim speed—as many swimmers and triathletes have. No matter how much he trains, his swim pace never improves—and he routinely runs out the string during training. He often starts a set of 100m repeats at a brisk 1:30, then gradually fades—often to a pace as slow as 1:50.

Bill can do an Ironman swim in a respectable 1:10, but—given what happens during his training swims–wonders if it’s worth the effort it might take to swim faster.

When I explained the techniques that will allow him to both swim faster and become a far more ‘tireless’ swimmer—able to complete longer swims at a faster pace, and feel completely fresh upon finishing—Bill says “My mind is blown” upon realizing that the techniques, and stroke emphases, that will increase his efficiency are exactly the opposite of what he thought.

‘Permission’ to swim less

During the post-interview wrapup, Bill tells Rich: “I feel like Terry gave me permission to trade an 3000y training session for a 1500y session focused on increasing my stroke efficiency.” Why is this so? Because it takes far less time and dramatically less training volume to increase economy—the priority Rich cited—than it does to make that ball of string larger. And shorter training sessions are almost always more effective in doing so.

Please give a listen. I promise you’ll enjoy.

We’ve planned at least one more interview segment where we discuss the advantages of training designed to created adaptations to the brain and nervous system—instead of the aerobic system—and how to get it. Which will also be the topic of next week’s blog. Stay tuned.

The post Endurance: Wow, It’s Complicated! appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 24, 2017

Swim for Health and Vitality: How to resume swimming after a layoff–Learn and Discover

Thursday January 5th was my final full day of coaching at our Open Water camp at St John USVI. After swimming twice a day in the Caribbean since Jan 1, I was excited about returning home to New Paltz to resume pool training with a goal of improving my Adirondack Masters 65-69 age group record of 25:57.6 for 1650 yards set the previous month.

That afternoon, while hurrying down a rugged trail to the beach for my final session of coaching at the camp, I tripped and fell headlong—hard enough to get a faceful of dirt. When I stood up and brushed myself off I saw blood pouring from a long and deep gash on my left shin, just above the ankle. It looked like something that could be bone-deep.

I made my way up the trail to the Concordia Eco-Resort guest center, where I was fortunate to receive expert first aid—initially from a couple of fellow guests who’d had Red Cross training, and soon after from Rena Stewart, a trauma surgeon and her husband Melvin, a nurse, who were among our campers.

I was transported by ambulance to St Johns’ small medical center where my wound was stitched up (16 stitches) by Dr. Jason Snow, who turned out to be a TI enthusiast. He told me the stitches should remain in for at least two weeks, after which a bit more time might be needed for complete healing of the wound.

But I was scheduled to leave Jan 17 for Elche Spain for nine days of coaching training. Consequently, the stitches weren’t removed until I returned home, four weeks later. And the wound was so slow in healing that it was only yesterday—seven weeks to the day since my fall–that the wound closed sufficiently to allow me to swim again.

I was in Sarasota FL, visiting old coaching buddy Ira Klein, with whom I’d coached 40 years earlier. It was 7 am as I stood at poolside preparing for my first swim after my longest layoff since I’d joined Masters swimming in 1988. I had a lane to myself, with Ira’s Masters group on one side and his teenaged swimmers on the other side. In what I thought was a lovely omen for my first swim, the sun broke through the clouds over my left shoulder, while at the same moment a rainbow formed over my right shoulder.

I stood at the edge of the pool with no goal other than to find a ‘happy place’ and learn how I would swim after 7 weeks ‘dry.’ How would my stroke feel, what would my stroke count be?

I also had in mind that, two weeks earlier–still unsure when I might be able to swim again–I had entered the 1650y free in the New England Masters Championships on March 11. Forty-five years ago I would never have dreamed of attempting such a demanding race distance on anything less than three to five months of hard training. Now I view it differently: As an opportunity learn—rather than prove—something about myself.

How efficiently could I swim 66 consecutive lengths of a 25-yard pool, and how masterfully could I pace myself—on even a very modest level of fitness? On the plus side is that I now rate neural fitness more highly as a predictor of performance than aerobic fitness. Neural fitness being the durability of efficient movement patterns in my brain and nervous system.

The advantage of neural fitness is that it survives layoffs far better than aerobic fitness. My muscle memory should be quite good, even if my cardiovascular fitness—how much oxygen and fuel I can supply my muscles—was quite compromised.

So this first swim would first of all take inventory of my muscles’ memory of how to maintain an efficient stroke with minimal fatigue. I eased into the pool and swam my first length. A little stiff and my stroke count was 17—the highest count in my Green Zone.

I swam another length, a bit less stiff and 16 strokes. After a short rest, I swam another. It was feeling more familiar and I took only 15 strokes. So I decided to explore how I might do if I stretched it out: I would continue swimming as long as I felt fresh and could maintain a 16-SPL stroke count.

I swam 15-SPL on my first length, flip-turned and went 16 on my second, flipped again and kept going. On the third length I flipped after 16 strokes, but my toes barely grazed the wall. I’d lost some speed or momentum on that last length. I stopped and returned to the wall.

I took a short breather. On my next swim, I was able to hold 16 strokes quite easily through six lengths, after taking 14 then 15 on the first two. The key was a better turn and relaxed, super-streamlined pushoff, maintaining a slippery bodyline as I surfaced with my first stroke and a perfectly integrated first breath.

What was most striking was how rapidly I was regaining my sense of swimming economy. With each repeat—and almost every length—I was making a better connection with a deeply imprinted efficiency patterns and recapturing muscle memory. Despite my lack of conventional fitness, the farther I swam, the better I seemed to do

I hadn’t timed any of my laps yet. I decided to try a timed 200—so long as I could maintain that relaxed feeling and 16-SPL stroke count for the entire 200. My time was 3:39. My slowest timed 200 ever, but it gave me a benchmark. I’d chosen 200 because I felt it would provide a decent indicator of what pace I might be able to hold for 1650 yards after two more weeks of—possibly intermittent–swimming.

I rested for just 20 seconds and, on a 4:00 interval, swam another. It felt just as good and I slowed by only a second to a time of 3:40. I had only a few minutes before the pool had to be cleared, and I felt so good, I decided to do one more 200. It felt just as relaxed, was just as efficient, but it was five seconds faster—3:35.

I left the pool feeling completely elated—over how delicious the water and my stroke felt, and how quickly I’d been able to tap into my neural fitness. I also now had specific benchmarks or measures to build upon in the two weeks prior to my 1650 at New England Masters.

Specifically that I could—with very little physical effort, but considerable mental effort or focus—swim 200 yards at an average stroke count for 25 yards of 16, and an average pace per 25 yards of just over 25 seconds. And with a little calculation I knew my average stroke tempo as well—1.28 seconds per stroke. I’ll work steadily and at low pressure over the next two weeks to incrementally improve the pace and tempo at which I can hold 16 SPL, over incrementally greater distances, without working any harder.

I emailed my good friend Lou Tharp about that first practice. Lou will also swim the NEMS 1650 and we’ll count for each other. Lou wrote back with a really eloquent description of that approach to practice. Lou’s description strikes me as the ideal prescription for how to return to training after a layoff. And for a many other reasons or benefits as well.

Lou wrote: “I also swam yesterday after a layoff—six days due to a stomach virus. But before that I was practicing to find an objective. I’d start with no plan and trust that one would emerge – the opposite of fly fishing because I didn’t ever snap the line back. I just let the practice go where ever it went. This creates an opening for learning and discovery. Sometimes having structure takes my focus away from learning/discovering.

The extreme counter-example is a masters practice of lots of general work with no skill emphasis. When I get finished, I have an empty feeling – like talking on the phone while driving. I’m not sure what happened on the road while I was on the phone just as I’m not sure what happened in my mind when I was in the water.

The no-objective practice learning/discovery could be mechanical or emotional, and it could be something I’d learned before that I forgot about. It’s like being a basset hound out for a walk. You never know what you’re going to sniff out, but when you get back home, it’s been a satisfying experience.”

May your laps be as happy as mine—and may they be filled with learning and discovery.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: How to resume swimming after a layoff–Learn and Discover appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers