Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 9

March 16, 2018

The (Re-) Education of a Competitive Swimmer

This is a guest post by TI Coach John Fitzpatrick, originally published in 2014. John is owner and head coach of Chicago Blue Dolphins, an aquatic fitness business based in downtown Chicago. He has been is a Total Immersion Coach since 2002 and is a member of the American Swim Coaches Association (ASCA) and an ASCA Certified Level 2 Masters Coach.

John has been a competitive swimmer for over thirty years and competes as a Masters swimmer in backstroke, butterfly, and individual medley events. Chicago Blue Dolphins runs 12 large group swim practices for adults in multiple Chicago locations to help bridge the lessons in the Swim Studio to practice and training in pools and open-water.

I’d been a swimmer since early childhood, but I don’t feel like I started to understand swimming until the fall of 2000 when someone recommended I read Total Immersion: The Revolutionary Way to Swim Better, Faster, and Easier.

Reading the book began a journey, which, before long, led to my becoming a TI Coach. TI taught me a new pain-free way of swimming, which I thought everyone should learn.

Birmingham MI, where I grew up, was kind of a swimming hotbed. I started lessons at age 3, and joined a swim team soon after. I continued through high school, specializing in backstroke and individual medley.

We trained in the usual way, doing long, intense workouts for months on end, then radically reducing volume and intensity over a week to 10 days. We endured constant fatigue and depressingly slow times for several months, in expectation of swimming much faster in a ‘tapered and shaved’ final meet. Or so the theory went.

For me it seldom seemed to work that way and enduring the pain and tedium came to seem pointless. By the end of high school, I literally hated swimming and didn’t go near a pool for years after.

After graduating from the University of Michigan, I moved to Chicago for work in 1997. I joined a Masters team because swimming seemed like the sensible way to get back i shape and the team provided a great social outlet as well. I was soon back into a familiar training routine—attending four to five workouts per week, and chasing whoever was ahead of me in the lane.

But as the workouts picked up, my shoulders began to ache, which eventually became searing pain on every stroke. When I told a friend how discouraging this was, he suggested I read the TI book. That was so eye-opening, I immediately read the 4-stroke TI book Swimming Made Easy

For the next five months, I didn’t so much as look at the pace clock. Instead I spent hours each week lap learning and refining drills from TI’s VHS tapes. I found myself absorbed by new sensations and distinctions I experienced in the drills, then applied in short, easy swims.

My Masters teammates thought I was crazy, but not only did my pain disappear (and has never returned) but for the first time in my life I was actually paying attention to how I moved through the water.

Among competitive swimmers, the idea of striving to feel good in the water is antithetical to an ethos that glorifies ‘pushing through pain barriers.’ Yet I found that feeling better translated into swimming better.

During all those years of hard training my freestyle stroke count was 18 to 19 strokes per length, at best. After learning TI, I swam as fast as before—but much more easily–taking just 14 to 15 strokes per length.

I rejoined my Masters teammates in training and meets, and experienced far more success, despite reducing my training hours by 30 to 40 percent—to make time to coach at some of our workouts. My challenge was finding a way to incorporate what I’d learned from TI into traditional interval workouts.

The less experienced swimmers had an immediate positive response to the TI drills I slipped in during warmups. More advanced swimmers resisted the drills, so I resorted to what we call ‘Sneaky TI.’

I gave the interval repeats they craved–but included focal points and stroke counting. They still got their workout, but admitted that doing it with a concrete focus made it more enjoyable.

It dawned on me that, whereas traditional workouts usually amounted to little more than physical pounding, TI training—when applied in competitive-swimming framework—were actually a ‘rehearsal’ of the skills, strategies, and pacing that actually won races. And, as Terry says: Training happened.

Twelve years as a TI coach have shown me that TI is a ‘holistic system.’ While those who simply learn the techniques swim more efficiently, those who take time to pursue the whole process, as I did, experience a farther-reaching transformation.

When you begin with ‘vessel shaping,’ then progress to refining and imprinting whole-stroke efficiency, you gain a foundation that sets you up for lifetime improvement.

When swimmers realize TI lessons aren’t the swimming equivalent of a flu shot, or simply a pro-forma exercise, they not only change movements, they also make behavioral and mindsetchanges that allow you to apply TI methodology to any task or goal.

For competitive athletes like myself and those I coach, this means gaining the ability to modify a generic workout to your own specific needs; and to focus on personal improvement priorities, instead of racing and chasing lane mates.

As a coach, I strive to give my athletes a foundation of sound biomechanics, then train their physiology to support those mechanics at race speeds, counts, and tempos.

If you’re reading this and are just becoming acquainted with TI (and especially if your goals include performance-oriented swimming) I urge you to consider the process I followed. Allow yourself time to explore new sensations, and to measure your swimming by how good it feels, not by minutes and seconds. You’ll not only learn to love and understand swimming, but—over the long term–you’ll swim faster too.

Below is a video in which Terry and I discuss how I learned to seamlessly blend technique and training in my own development and how I coach my swimmers.

The post The (Re-) Education of a Competitive Swimmer appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 2, 2018

Guest Post: In Memory of Terry Laughlin

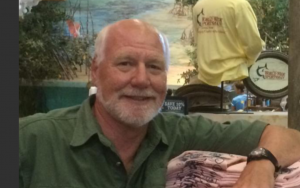

Ray Bosse Coached at the United States Military Academy for 19 years, 13 (1989-2001) as the head coach of both the men’s and women’s programs.

During his tenure he led women to 3 conference championships and the men to 9 conference titles. Ray was named conference coach of the year 9 times, coached swimmers at the 1984 and 1988 Olympic Trials, and coached three NCAA champions (2 women Div II and 1 male Div I).

I met Terry when he came to West Point in 1984 to train a swimmer long course for the ’84 Olympic Trials. I had known him in passing as a coach on deck, but when he came to West Point I got to know him on a more personal level. We became friends and in 1989 I needed to fill an unexpected vacancy on the staff in October for just the season. I knew Terry was in between coaching jobs and I needed someone who could immediately step in and coach for the remainder of the year.

During this year is when Terry visited Coach Bill Boomer in Rochester and was began to formulate the concept of TI. We talked about it on many of the bus rides to meets, and while at Colgate for a dual meet Terry met the director of summer camps and that summer held the first adult TI camp at Colgate.

After the 1989 season I hired another full time assistant and Terry focused on building the Total Immersion brand. As the freestyle weekend workshops grew in popularity I often assisted conducting the them in the Northeast. Terry was constantly adjusting the process based on his observations and was always eager to discuss new ideas.

In 1996 Terry and I had lunch and he asked about becoming a volunteer coach to show that the TI principles were applicable to Division I competitive swimmers. Many competitive coaches thought that TI only focused on slow technique based swimming and only applied to adults and open water swimmers. Having already applied many of the TI techniques to my teams at West Point, I quickly agreed to Terry’s request and gave him the sprint group because I felt they would be the most open to new ideas and I felt were frankly the most under performing group at the time.

Terry started in 1997 and coached through 1999. He would coach 3 times a week on deck and email his workouts the other two days. All the while he ran the growing TI company; at times I worried that he was burning the candle at both ends but that was Terry! By the end of the 1999 season the proof was there as evidenced by two of many success stories highlighted in the newsletter article below. Terry left to build TI into the world wide brand it would become.

I continued to work with Terry as he developed TI techniques to teach the the four competitive strokes to age group and masters swimmers. We had just two summers ago began filming in New Paltz with age group swimmers the teaching cues and steps for backstroke, breaststroke and butterfly.

What I miss most about Terry is his genuine kindness and the long discussions we would have on his back deck after doing a private lesson in his home-based swim studio. He was such an outside the box thinker, but most of all a real friend.

Ray Bosse contributed to the following tribute which appeared in this month’s ‘Army Swimming & Diving’ newsletter:

Terry Laughlin, an Army assistant coach in 1989 and from 1997 through 1999, passed away in October after suffering from prostate cancer. He began coaching at West Point when Head Coach Ray Bosse (’77) asked him to fill an unexpected opening in the staff.

“I got to know Terry when one of his swimmers who qualified for the ’84 Olympic Trials came to West Point to train long course,” Ray

says. “I found out how well he could coach, so when the position opened up, I thought of him right away.”

During the season, Terry conceived a process for teaching swimmers how to move through the water more efficiently using techniques that reduce drag and emphasize streamline and balance. The overreaching concept was more speed from less energy. He dubbed his novel approach Total Immersion, or TI, and left West Point after the ’89 season to develop the concept further. He stayed in touch with Ray, who from time to time assisted with TI workshops.

Total Immersion found a home in the 1990’s among triathletes and adult open water swimmers, but coaches of in-pool, competitive swimmers had their doubts. Terry approached Ray before the 1997 season about becoming a part-time assistant coach so that he could test his ideas on a group of Army swimmers.

“I was only too happy to accommodate him,” Ray says.

Terry was instrumental in the success of Heidi Borden (’01) and Joe Novak (’99) among others. Heidi went on to become the swimmer of the meet at the Patriot League Championships her senior year. Joe remains the only male named swimmer of the meet three consecutive years. His Academy record in the 100 free lasted 17 years until Chris Szekely (’16) broke it in 2015. He’s still ranked third all-time at Army the 50 and 100 free. In 2015, both Heidi and Joe were named to the Patriot League’s all-time team.

“Terry took me from a mediocre college swimmer to elite in one season,” Joe says. “However, what I remember most was his passion, his ability to break problems down, and most of all, his belief in us. He made me feel like I could do anything, and then he gave me the tools to be successful.”

Mary Roush (’00) gave a moving tribute at Terry’s memorial service in November in New Paltz, New York. Terry is survived by his wife Alice and their three daughters Fiona, Cari and Betsy.

The post Guest Post: In Memory of Terry Laughlin appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 9, 2018

Guest Post: What Terry Laughlin Taught me about Swimming and Mastery

Sasha Dicther has been blogging and speaking about philanthropy, generosity and social change since 2008.

For more by Sasha Dichter you can follow his writing at http://sashadichter.com or watch his TED talk here.

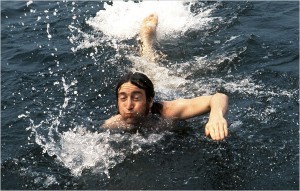

Swimming is a funny thing: on a planet covered by water, more than 37 percent of adults cannot swim the length of a 25 yard pool. I was nearly part of those numbers. Though I’m a lifelong athlete, from the age of 6 swim lessons terrified me, and as recently as three years ago, while I could swim 25 yards of freestyle, I’d grab at the end of the pool, panting, looking incredulously around me at the people of all ages, shapes and sizes swimming lap after lap without needing a breather.

In 2015 an arm injury finally got me back into the pool. Over the course of a year, I willed my way to swimming a mile. But there was always a sense of lurking panic, always a survival instinct kept at bay that could kick in at any moment—never mind that air is literally an inch away and all I need to do is turn my head to breathe.

I finally decided that muscling my way through the water wasn’t my goal, and, urged on by a friend who can swim across the Long Island Sound, I bought some of Terry’s books and videos.

The funny thing about these books and videos is that they don’t start with swimming. They start with floating.

Terry’s entire philosophy is based on the notion that all of swimming is taught the wrong way. In Terry’s view, we spend most of our energy in the water trying not to drown, which is why we get so tired and why we move forward so little. If we could learn to float and balance, we could swim effectively, efficiently, and with joy. As Terry famously states, “it’s not the size of the motor [how hard you stroke and kick] that matters, it’s the shape of the vessel.”

That may be, but “vessel shaping,” Terry Laughlin-style, can feel like a pretty silly activity.

Having read much of Terry’s Ultra Efficient Freestyle e-book, I eventually find myself in my local pool trying out Lessons One and Two from the book. They are titled “Torpedo” and “Superman,” and both involve pushing off the bottom of the pool and just floating with arms at your side (Torpedo) and extended (Superman). Over and over again.

Imagine, if you will, those same swimmers speeding past me, cranking lap after lap, and I’m just trying to float the right way. Funny, right?

But eventually I learn how to float face down and not sink.

And then I learn how to float on my back and not sink.

And then I learn to float on my side and not sink, and to extend one arm and not sink.

And then I learn to float on my side, with one arm extended, and face my head down and kick. And then I’m supposed to effortlessly rotate up to breathe.

But I can’t.

Whenever I try, I start to struggle, and then strain, and then panic. After a few tries, and lots of water up my nose, I stop. A few weeks after that, I skip to the next lesson and tell myself that this step probably wasn’t all that important after all. I work my way to the end of the book. I’m a bit of a better swimmer. But in my heart I know that I skipped the most important parts.

When Terry passed away, I had a sense of loss, and, in honor of him, I went all the way back to the beginning of the book to start again. A year later after I’d given up, I find myself back at lesson two, trying to learn to breathe on my side without panicking.

And it still doesn’t come easily to me. But I’m keeping at it. And this time, with a bit more perspective and appreciation, I’m also using it as a chance to learn about how I learn: to observe how committed I really am; and to notice the gap between the narrative I tell myself about what I’d like to learn (the videos I’m happy to watch, the book I’m happy to read) and how many hours I’m willing to spend in the pool—when I have lots of other priorities and lots of other ways to exercise that come more easily.

Most of all, it’s a chance to watch my own narrative of failure, because mostly I feel like I’m failing. Each time I fail, after blowing up water out of my nose and cursing a bit, I ask myself: do I really, truly, believe that I will fail at this forever? Is it possible that if I put in time and concerted effort, that I am the one person in the world who simply cannot accomplish this?

Yes, it’s possible. But it’s unlikely. And since each next “thing” that Terry has me do is such a tiny increment on the last thing, failing this time means I never really mastered the last step, or I’m not willing to master the next one.

The frustrating, amazing thing is, it’s never Terry’s fault, and it’s never a lesson that doesn’t work. It’s really about what I’m willing to do: the time I am willing to put in, how deliberately I am willing to practice, how well I deal with the plateaus.

And while part of this endeavor is about my interest in learning how to swim, beyond that, I am interested in what Terry has to teach me, and teach all of us, about mastery. Because what Terry has done is to take his passion for swimming and create a program for self-taught mastery that literally anyone can accomplish. Each step is so clear, so well thought through, and broken into such small pieces that each can be digested and practiced if you have the will and the persistence and the capacity for reflection and self-observation.

And what Terry’s done with swimming could be applied to just about anything. It’s a question of our willingness to take the time to deconstruct something, to deeply understand its component parts, and to commit ourselves to the often repetitive, focused, intentional work of rewiring our nervous system or our limbic system or our musculoskeletal system or our habitual thoughts and feelings, until they, slowly but surely, change.

This is how we can learn anything, without all the false stories about our own limits and the talent we do and don’t have.

If you want to get a taste of Terry’s joy, insight, and wisdom, I’d encourage you to listen to this podcast he recorded with Tim Ferris less than two weeks before he passed away. I found it deeply moving.

In the meantime, I’ll keep going to the pool, less than I’d like to think I would, but more than not at all. I believe that one day I will become an effortless swimmer, and I commit that until then, I will keep walking the path.

Here’s to you, Terry.

The post Guest Post: What Terry Laughlin Taught me about Swimming and Mastery appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 2, 2018

What Made Terry Laughlin Such a Great Swimming Coach?

Bob McAdams was trained in freestyle at age 7 using conventional training methods and began swimming regularly for fitness as an adult after his doctor told him that he needed to get more aerobic exercise. Initially, he was just trying to increase the distance he could swim without needing to stop, but he became interested in trying to improve his speed after watching the 1996 Olympics on television. Around that same time, he learned about U.S. Masters Swimming and realized that it was possible for adults to swim competitively, and even though he had never been exposed to competitive swimming as a kid, he developed a goal of becoming a competitive swimmer as an adult. This eventually led him to Total Immersion, and he finally participated in his first swim meet in 2002. Around that same time, he was recruited by Terry Laughlin to become a coach and went through his TI coach training. He began coaching at a TI kids’ camp and at TI weekend workshops the following year, and began offering private lessons in 2004. Since then, he has worked with beginning swimmers, fitness swimmers, triathletes, and competitive swimmers ranging in age from 3 to 74. He has also had several articles on various aspects of swimming published in the online newsletter Total Swim. Bob continues to swim competitively and to work on improving his times and increasing the spectrum of pool events in which he has participated.

Bob McAdams was trained in freestyle at age 7 using conventional training methods and began swimming regularly for fitness as an adult after his doctor told him that he needed to get more aerobic exercise. Initially, he was just trying to increase the distance he could swim without needing to stop, but he became interested in trying to improve his speed after watching the 1996 Olympics on television. Around that same time, he learned about U.S. Masters Swimming and realized that it was possible for adults to swim competitively, and even though he had never been exposed to competitive swimming as a kid, he developed a goal of becoming a competitive swimmer as an adult. This eventually led him to Total Immersion, and he finally participated in his first swim meet in 2002. Around that same time, he was recruited by Terry Laughlin to become a coach and went through his TI coach training. He began coaching at a TI kids’ camp and at TI weekend workshops the following year, and began offering private lessons in 2004. Since then, he has worked with beginning swimmers, fitness swimmers, triathletes, and competitive swimmers ranging in age from 3 to 74. He has also had several articles on various aspects of swimming published in the online newsletter Total Swim. Bob continues to swim competitively and to work on improving his times and increasing the spectrum of pool events in which he has participated.

It was three months ago that I learned of Terry Laughlin’s death, and since then, I’ve been thinking a lot about the question posed in the title.

First, let me say a little bit about what constitutes greatness when it comes to swim coaching. I doubt that there is any swim coach who has achieved enough greatness for their name to be widely known outside of swimming circles. And within swimming circles, the coaches who have been regarded as “great” have typically been those who coached elite swimmers while they were making impressive achievements. The rationale is that since elite swimmers are already doing so many things correctly, a coach who can help them to become even better must be a real expert.

But when we examine Terry’s accomplishments, it becomes clear that he took greatness in swim coaching to a whole new level. Here is a man who, during his 66 years on Earth, created a swim coaching program that:

has established a continuing presence on 5 continents

has worked successfully with swimmers ranging in age from young children to people in their 90s

has benefited swimmers ranging in level from beginners who are still trying to feel comfortable in the water to advanced competitive swimmers who are pursuing lofty goals

has programs that are designed to meet the needs of both pool swimmers and open water swimmers

has helped a wide variety of swimmers pursue their swimming goals, whether those goals involve competition, fitness, meeting job prerequisites, or simply obtaining more enjoyment from being in the water.

I can’t think of another swimming coach whose accomplishments have been that broad!

So how did he do it? What set Terry apart from other coaches? I came up with 7 things.

Terry focused on the science of efficient swimming.

One of the most significant things about this statement is that it is significant. After all, we might expect that every swimming coach would be focusing on this, and of course many do in varying degrees. But the fact is that much of traditional swim coaching has, essentially, tried to treat swimmers like runners, saying, in effect, “You know how to do it. So now let’s condition you so that you can do it at faster speeds and/or over longer distances.” But Terry realized that because water is such a dense medium when you’re moving through it, and such a slippery medium when you’re pushing against it, the science of how humans move efficiently through the water is central to good swimming.

I suspect that the reason why the train-swimmers-like-runners paradigm was so persistent has to do with the way that people typically become swim coaches. Most swim coaches are people who joined a swim team as a kid and did well enough at it that they were still swimming competitively when they entered college. So while their classmates were getting summer and part-time jobs working at a fast food restaurant or grocery store, they got jobs coaching swimming, and their chief qualifying credential was their success as competitive swimmers.

It was only natural that these coaches would adopt the same training paradigm that had been used with them, for two reasons: First, it was what they were used to, so they assumed it was “how things are done.” Second, the swimmers who succeeded under the train-swimmers-like-runners paradigm were those who were able to figure out intuitively how to move efficiently through the water, so they assumed that other swimmers would be able to do the same thing.

What happened in practice, of course, was that some swimmers failed, decided they weren’t any good at swimming, and quit, while others partially succeeded and stayed with swimming until their mediocre performance caused them to get cut from their team, or until they became discouraged with it and quit on their own. And a few succeeded and went on to become the next crop of swim coaches. It was easy to pass off the first group as people who weren’t cut out to be swimmers and the second group as people who either weren’t cut out to be great swimmers or who didn’t work at it hard enough.

But Terry was one of those mediocre swimmers. He at one point got cut from his team, and by his own account was only able to make his college team because it wasn’t all that good. So when he began coaching, he felt empathy for the mediocre swimmers, and knew from experience that many of them were just as fit and were working just as hard as those who were succeeding. So Terry made it his life’s work to figure out what the successful swimmers were doing differently. And that led him into basic physics, hydrodynamics, and human physiology (as it compares with fish physiology).

Terry also focused on the science of effective training.

About 10 years ago, I read some posts in a swimming group by a man whom some of his peers described as the most dedicated masters swimmer they had ever seen. They said that he spent an enormous number of hours in the pool, but added that he was only achieving mediocre results because his technique was poor. After repeated suggestions, the man finally signed up for a lesson with an Olympic swimmer (he was convinced that only an Olympian was qualified to give him advice on his technique), but he reported in disappointment that he hadn’t been able to make the technique changes the Olympian had told him he needed to make in order to move faster in the water.

And this illustrates an important point: It doesn’t do any good to know where the destination is unless you also know a path that will get you there! Terry realized that the science of how humans learn new motor skills (particularly as a replacement for old, faulty motor skills that have been so deeply ingrained that they have become muscle memories) is every bit as important to swim coaching as is the science of how humans move efficiently through the water. And this led Terry to the drill sequences that form the core of the Total Immersion training program.

Terry cared about people.

It appeared to me that Terry genuinely cared about every person he encountered, and that led him to want to help them pursue their swimming goals, whatever those goals were.

I originally found Total Immersion because of two events that happened a few months apart.

First, I went to a one-hour stroke clinic on freestyle at a local pool in the hope of improving my freestyle times (as I had done a year earlier when I attended a clinic on flip turns at the same pool). But, to my disappointment, I didn’t see any immediate improvements in my freestyle speed. And, as I continued practicing what we were taught, I developed, for the first time in my swimming career, shoulder problems! In fact, in the very month when I had been hoping to achieve some benchmarks I had set for myself, I was instead having to stay out of the pool to give my shoulder time to recover. In desperation, I went to a local bookstore and looked through books on swimming to see if any of them had exercises for recovering from shoulder problems. I ended up buying a blue and yellow book by Terry Laughlin called Total Immersion.

Several months later, I approached the aquatic director at the YMCA where I was swimming and asked what she would recommend for someone who was trying to learn competitive stroke technique and was willing to spend some money on it. Without hesitation, she picked up a piece of paper and wrote out the web id of the Total Immersion website, and said that a couple of their coaches had attended Total Immersion training and their facility had begun using the Total Immersion drills with their kids’ swim team (which, by the way, had a very good record of achievement). This recommendation confirmed the interest I had already begun to develop in the Total Immersion program, but when I thought about it afterward, I realized that there was also a second subtle message: Here was a woman who directed an aquatic program that got its revenues by providing swim training, officially to both kids and adults, and yet an adult had just walked up to her, figuratively waved money in her face, and said he wanted to learn competitive stroke technique, and she had responded by sending him somewhere else. While she was clearly recommending Total Immersion, she was also, in a roundabout way, saying that their facility didn’t want to deal with an odd fish like me.

And that was not the last time I was to encounter the same attitude from their facility. Three years later, when I had honed my freestyle and backstroke skills and learned butterfly and breaststroke through the Total Immersion videos, I was starting to think about entering my first swim meet, but realized that there were some things I still needed to learn before I could do this: forward starts, backstroke starts, open turns (for butterfly and breaststroke), and the stroke-changing turns that are unique to individual medley. After waiting in vain for the facility to offer any training in these things for adults, I finally decided that maybe I really was an odd fish and that they weren’t offering training in these things because nobody but me wanted to learn them. So I signed up for a couple of private lessons.

Although it became clear that neither of the instructors they assigned to me knew how to teach forward starts, the second one enlisted the help of another instructor who was a teen on their swim team, and they managed to teach me a decent enough start to enable me to be in my first meet. But I was shocked, the next time the facility advertised private lessons, to find that they had added a stipulation that the lessons were only open to swimmers aged 18 and under! They really didn’t want to deal with an odd fish like me!

I gathered that one of the reasons Terry spent so much time training adults was because almost no one else was doing it, and Terry felt strongly that the same swimming opportunities should be available to everyone, regardless of age, background, race, nationality, or any disability they might have.

Terry liked to give people new dreams and help them find new ways to enjoy the water.

Several years ago, I had the experience, for the first time, of giving a lesson to a swimmer in real open water (as opposed to a roped-in, lifeguarded section of a lake). I am a pool swimmer rather than an open water swimmer, and I described in an email to Terry how, for the first time in my life, I had gone far enough in a lake to see the scenery change on the shore, and had had the realization that I could actually use swimming to go somewhere! Terry had, of course, had this experience many times, but he seemed delighted that I had finally experienced it.

Again and again I saw Terry find real joy in the fact that he had helped a swimmer to have a new experience in the water or gain a new insight. And while I had given some thought to becoming a Total Immersion coach before Terry approached me about it, the fact remains that he approached me before I approached him.

Terry also suggested at one point that I think about writing a book on the experience of becoming a competitive swimmer as an adult, since so few people do it. I haven’t done it yet, but I have given some thought to it, and it still might happen!

Terry was humble.

I don’t recall ever seeing Terry try to toot his own horn or assert his own importance. And I believe that that humility also affected the Total Immersion program in several important ways.

A reason Total Immersion has worked with such a wide variety of swimmers is because Terry was willing to help swimmers achieve goals that weren’t likely to help build Terry’s reputation. A coach might build his acclaim in swimming circles by helping a swimmer to make it to Olympic trials, or by helping a member of an Olympic team to win a gold medal. but they aren’t likely to do it by helping a swimmer who’s afraid of the deep end to feel comfortable in water over their head, or by helping an adult to be in their first swim meet or make it through the swim leg of their first triathlon, or by helping a man in his 90s to improve his swimming.

Terry’s humility also kept him open to the possibility that someone else might have gained an insight into swimming that he hadn’t, and that undoubtedly benefited the Total Immersion program in a number of ways.

It also takes a certain amount of humility for an accomplished swim coach like Terry to believe that he can teach other people to train swimmers as well as he can. And it takes even more humility for him to believe that he can teach other people to train coaches as well as he can. But if Terry had not had that kind of humility, the Total Immersion program couldn’t have established a continuing presence on 5 continents. And it would have died (or at least begun dying) on the day Terry died.

Terry had an amazing way of turning experiences that would discourage most people into learning experiences.

Being cut from a swim team has been enough to cause many swimmers to give up competitive swimming, but for Terry it became the beginning of a lifelong quest to figure out why some swimmers move through the water with greater ease than others. And Terry applied this same attitude toward other setbacks. When he had to stop swimming for several months because of shoulder surgery and avoid stressing the shoulder too much during the recovery, Terry turned it into a learning experience and actually gained some new insights into how our bodies interact with the water, which he chronicled in a series of articles. And Terry even turned his final illness into a learning experience.

Terry had an infectious passion for the sport of swimming.

One of the last things Terry wrote was an account of swimming in an open water event with one of his daughters in late August. That seems really appropriate, because it means that one of the last things he did, even while his cancer was progressing, was to participate in an activity that had been the passion of his life.

You didn’t have to interact with Terry very much to realize that, for him, swim coaching was not just a job—swimming and swim coaching were a passion! I saw him on numerous occasions take the time to give people his counsel, even though there appeared to be no conceivable way he could ever receive any compensation for it, and I suspect that he would have coached for free if his financial needs were already being met. I gather that, for him, receiving money for coaching was just a means of allowing him to devote more of his time to it.

As I think about all of these things, I must admit that it makes me a bit nervous. I find myself wondering whether Terry really succeeded in teaching us all of that. Did he succeed in giving us, not just his knowledge, but also the other qualities that made him such a success? Above all, did he succeed in filling us with his passion for the sport of swimming? To that, I can only say: I hope so!

The post What Made Terry Laughlin Such a Great Swimming Coach? appeared first on Total Immersion.

January 10, 2018

Maximize Return on Your Aerobic Investment: Zenman’s Brief Guide

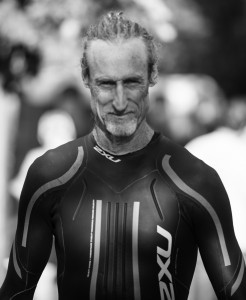

Shane Eversfield is Founder and Head Coach of Kaizen-durance, serves as a Total Immersion Master Coach, and isan accomplished ultra endurance athlete. Shane and Terry met after Terry read Shane’s first book “Zendurance”.

Shane enjoyed countless hours swimming and dialoging with Terry. (And they cooked many meals together too!) Frequently their discussions centered around endurance sports as a highly effective form of mindfulness practice, and how mindfulness skills enhance the quality of our lives in every area.

Shane Eversfield is a Total Immersion Master Coach, and Founder of Kaizen-durance, Your Aerobic Path to Mastery. He is offering the inaugural Advanced Total Immersion Weekend Workshop and Kaizen-durance Introductory Running Lab in Coral Springs, FL, 27-28 January.

Introduction

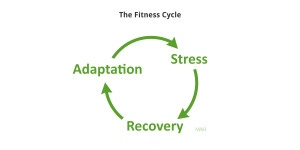

In my previous blog, we explored the Fitness Cycle. This is the process we use to swim faster, run longer and climb steeper hills on the bike. The Fitness Cycle has three phases:

Stress

Recovery

Adaptation

In this blog, we identify what we actually target in this cycle, and how we can most effectively improve our fitness now, and for many years to come. I call this “hacking performance potential”. Are you ready to hack your potential?

The Big Three

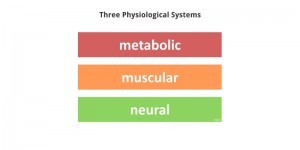

First, we must identify what is affected by the Fitness Cycle. When we train we are stressing three physiologic systems:

Muscles

Metabolic (Aerobic)

Neural

If we really want to maximize the return on our training investment, then we should target the physiologic system that will respond and improve the most to training. Before we identify and focus on that specific system, it is vital to recognize that we will always stress all three systems when we exercise. If we design and structure our training to emphasize stress on one specific system, the others will also experience stress – perhaps to a lesser degree.

OK, So What Do They Do?

Let’s also look at the function of each of these three physiologic systems and how they enable us to swim each stroke and run each stride.

Our muscular system moves the bones of our skeleton. This is the real working system.

Our metabolic system provides a healthy operating environment for the muscles (as well as the nerves). This optimal environment includes an adequate supply of energy and oxygen, and the removal of waste and carbon dioxide, among other supports.

Our neural system coordinates and synchronizes the movements of all of our muscles so that we move the more than 300 bones of the skeleton in a coordinated and efficient manner. This complex task of oversight and control involves both perception and action. Our neural also provides feedback and adjustment of the metabolic system to maintain an optimal working environment.

Each of these systems is essential for us to swim, bike, run, or to perform any action in our lives – even breathing.

And Now … Back to the Big Question

What system responds and improves most readily to training? More specifically, what system recovers and adapts best when we stress it?

Some of you may be surprised to discover: It’s your neural system. Surprising, because most of us have focused all along on the metabolic system – especially if we are performance-oriented.

After all, cutting edge exercise science focuses on improving our aerobic capacity – our ability to provide an optimal working environment for the muscles. Technology has given us heart rate monitors, power meters and GPS pacing devices that we correlate to specific zones of metabolic intensity. By monitoring this intensity, we can train to improve the optimal operating environment for our muscles to maximize performance potential – for a specific race at a specific pace, from sprint to ultra, or simply to maintain an active and healthy lifestyle.

This conventional method of focusing on metabolic fitness enables coaches, athletes and recreational exercises to achieve reliable and even remarkable results, using precise metrics. It’s easy to follow, with clear numeric guidelines. However…

Beware The Aerobic Wall

“VO2 Max” is a measure of an individual’s metabolic potential – a scientific standard of fitness. Well…

Once we surpass the ripe old age of 25, our VO2 Max begins to decline at a rate of 1% per year. Picture this decline as a massive wall that is steadily advancing towards you. Yikes!! In the panic to slow this rate of decline, most performance-driven athletes devote every training session to the desperate effort of slowing that advancing wall. I call this…

Banging Your Head Against the Aerobic Wall

If we devote every swim stroke and every run stride to resisting this inevitable aerobic decline, where is the joy and satisfaction that Terry Laughlin shared with us over the years in his teachings, his blogs, his life? If every workout is just another fruitless effort to push as hard as we can against that encroaching wall, where is the kaizen – the lifelong improvement?

Where is it? It’s quietly and patiently waiting for us in our neural systems. When we can let go of our fixation with resisting the inevitable decline of metabolic capacity, we can begin to cultivate the gift of wisdom that comes with experience and (Dare I say it?) with age.

What is this wisdom of the experienced and aging athlete, that enables us to improve for many decades beyond our 25th year?

“K.I.”: Kinetic Intelligence

If aerobic potential begins to decline at a rate of 1% per year after age 25, why are all the Hawaii Ironman World Champions – both male and female – always in their mid-to-late 30’s? (Paula Newby-Fraser won her eighth crown at age 40.) What do these athletes have that the younger athletes don’t?

They have what I call kinetic intelligence. With experience and practice these “older” athletes have done more than just trained aerobic capacity. They have learned:

How to use less energy for each swim stroke, pedal stroke and run stride

How to go faster with less fatigue and damage

How to sustain these activities for a longer duration, and with more precise pacing

They have acquired the wisdom of KI.

Connecting the Dots

As Terry has taught us, we cannot pursue swim speed or even endurance, until we learn technique. Here is the sequence we use to acquire and improve technique:

Target the neural system when you train. This is the system that learns.

Develop kinetic intelligence: You acquire KI through consistent and mindful neural training.

Focus on efficient technique: A strong foundation of KI empowers you to rapidly improve and continuously master efficient technique.

Train to Learn

The primary component of neural training is developing and improving technique. Neural training is a learning process. If we focus on developing and improving our technique in every training session – from recovery to high metabolic intensity – we can maximize the return on our training investment… for a lifetime. We can enjoy improved performance for decades beyond our aerobic peak.

And here is a most important point: Our neural systems can cycle through the Fitness Cycle faster than our muscles or metabolic systems, regardless of our age.

Neural Training: Here ’s How

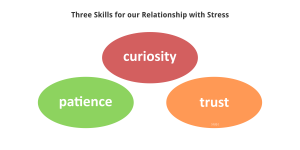

In my previous blog, we considered three skills that are invaluable for navigating the Fitness Cycle:

Beginner’s Mind

Trust

Patience

These same navigational skills empower us to to pursue KI every time we train:

With Beginner’s Mind, we bring curiosity to each training session. Curiosity is rocket fuel for learning.

With Trust, we use our own unique sense-felt experience in each moment as the most effective day-to-day guidance for building KI. Trust is the gateway into our own personal experience. And we trust that building this personal wisdom will provide a much greater long-term yield than just banging our heads against the Aerobic Wall, day-after-day.

With Patience, we can slow down enough to learn and discover, to practice and master great technique. Patience is our telescope to see well into the future from where we are right now. It allows us to relax and craft each stroke and each stride perfectly.

Abraham Lincoln Said it Best

Years ago, Terry included this insightful quote from Abe Lincoln as the byline for his emails: “Give me six hours to chop down a tree, and I will spend the first four hours sharpening the axe.”

No matter how much aerobic capacity and muscular strength we have, we can’t cut that tree down with a sledge hammer. We need a sharp axe. The same is true for swimming: Arms the size of tree trunks won’t help you swim fast if your body is like a sledge hammer in the water.

When we approach each training session well prepared and with a sharp axe, we can reliably hack into the process of rapid discovery and learning. What is this “axe” you need to sharpen? It is your neural system. When your neural system is tuned-in and focused, your perceptions and observations are sharp, and your responses and actions are brilliant.

Training: Workout or Practice?

Neurally targeted training sessions are no longer goal-fixated workouts that punish our bodies. They are diligent practice sessions. We approach each training session in the same way that a musician approaches each practice session:

The musician diligently attends to each note she plays. We too are attentive to each stroke, each stride we craft. How can we make each one better?

With “Aural Intelligence”, the musician constantly questions and refines her standards of excellence, her experience of technique mastery. With KI, we constantly evolve our experience of technique mastery.

The musician patiently examines how each note fits into the overall composition and performance. With patience, we craft each stride, each stroke to bring us gracefully and masterfully to our goal.

Sharpen Your Axe

To maximize the return on your training investment, and to hack your performance potential, sharpen your axe of attention and perception:

Pause: before you begin your session, even for just a brief moment

Question: What am I here to do? What can I learn today?

Summon the curiosity of your Beginner’s Mind

Invest your awareness and attention completely: No “auto-pilot”!

Trust the learning process, as it is guided by your sense-felt experience

Be Patient in striving for your goals, so you can be hyper-aware in each moment

Hack Your Performance Potential: Practice

As you begin each practice session, proceed:

Slowly and patiently

With focused purpose and accuracy

Consistently and faithfully, with perseverance

Embrace your weaknesses as the greatest opportunities for growth and discovery.

Go Slow? Forever?

When we specifically target the neural system, does that mean we always have to train slowly? Again, let’s look to the musician: When she is first learning to play a challenging composition, she practices slowly and patiently, with focused purpose and accuracy. With perseverance, she practices faithfully and consistently, even when it’s difficult.

Gradually, the musician is able to craft the sequence of notes with flow and ease. Now, she can begin to increase the tempo and still maintain the precision and accuracy. As performance-oriented athletes, our successful practice follows the same progression – from slow and easy to fast and intense.

Progression is always governed by your ability to maintain efficient technique. If technique erodes, slow down.

Speaking from my personal experience, I devote every training session to crafting graceful and efficient strokes and strides. I do this from low to high metabolic intensity. While I target my neural system in every training session, my muscular and metabolic systems still get trained.

Proof? Recently I visited the Endurance Sports Performance Center affiliated with Island Health and Fitness, where I teach. The technicians there performed a Ventilatory Threshold Test to evaluate my metabolic fitness. I scored in the 99th percentile of VO2 Max for my age – even though I don’t bang my head against the Aerobic Wall.

Conclusion

When we target neural fitness during our training sessions, it’s not about the exertion of mind over matter, or success at any cost. Our neural system is as much mind as it is body. Now, we are training mind IN matter. We are acquiring kinetic intelligence – the wisdom of the master athlete.

Lots More!

“Kaizen-durance, Your Aerobic Path to Mastery” is a six-book series I am producing that deeply investigates our Kinetic Intelligence Hack. We also explore the Pursuit of Mastery to maximize our performance potential in every area of our lives.

Read a synopsis of each book at this link and order Book One, “An Introduction to Kaizen-durance: Hacking Your Performance Potential at Any Age”, available in three digital formats.

The post Maximize Return on Your Aerobic Investment: Zenman’s Brief Guide appeared first on Total Immersion.

January 3, 2018

Terry Laughlin as a Mentor In and Out of the Water

Jeanne Safer, PhD is a psychotherapist who has been in private practice for over forty years, and the author of six acclaimed and thought-provoking books on neglected psychological issues—the “Taboo Topics” that everybody thinks about but nobody talks about publicly. Her special areas of expertise include siblings with difficult or dysfunctional brothers and sisters, women making choices about motherhood or who have chosen not to have children, adults struggling about whether to forgive people who have betrayed them, and those coping with the death of a parent. She lectures on these and other unusual and compelling topics.

Jeanne Safer, PhD is a psychotherapist who has been in private practice for over forty years, and the author of six acclaimed and thought-provoking books on neglected psychological issues—the “Taboo Topics” that everybody thinks about but nobody talks about publicly. Her special areas of expertise include siblings with difficult or dysfunctional brothers and sisters, women making choices about motherhood or who have chosen not to have children, adults struggling about whether to forgive people who have betrayed them, and those coping with the death of a parent. She lectures on these and other unusual and compelling topics.

Dr. Safer’s books include Cain’s Legacy: Liberating Siblings from a Lifetime of Rage, Shame, Secrecy and Regret (January 2012); The Normal One: Life with a Difficult or Damaged Sibling, Beyond Motherhood: Choosing a Life without Children; Forgiving and Not Forgiving: Why Sometimes It’s Better NOT to Forgive; and Death Benefits: How Losing a Parent Changes an Adult’s Life—For the Better. Both The Normal One and Beyond Motherhood were Books for a Better Life Finalists for the year’s best self-improvement books.

Dr. Safer has appeared on television (The Today Show, Good Morning America and CBS World News Tonight), as a psychological expert on The Montel Williams Show, and on radio (NPR’s Talk of the Nation and The Diane Rehm Show). She has contributed articles to The New York Times, The New York Times Book Review, O: The Oprah Magazine, More Magazine, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and other publications.

Dr Safer lives in New York City with her husband, historian and political journalist Richard Brookhiser.

This is the tribute I gave to Terry at his family memorial soon after his death. I want to share my long experience with this remarkable man with the TI community:

I’m Jeanne Safer, and I’ve had the extraordinary good fortune to have had almost weekly swim lessons with Terry for the past 15 years. Terry’s daughter Carrie was my first coach—she taught me, with enormous patience, how to breathe on the left—and then Terry took over. As a result I’ve been welcomed as an honorary member of the Laughlin family.

I’m going to read you the story of my most life-changing lesson with Terry. It’s from my latest book, The Golden Condom and Other Essays on Love Lost and Found, which is dedicated to him. Here’s the dedication: For Terry Laughlin—My coach, my friend, my inspiration. This is an excerpt from the chapter on mentors and the effects they have on your life:

Mentors are not just for the young. They can be found at any age if you seek them, although what you need and what you get from them changes later in life. Since your own character is no longer unformed and your identity is more secure, you are no longer so naive, impressionable, or adoring. As a result, you are more conscious of personality quirks, more attuned to the dynamics between you, and freer to know and to speak your mind. Since these late editions of the mentor/protege relationship are usually voluntary, you are not beholden to the mentor as an employer, or a professor, or as a professional role-model. At last, there is no discrepancy of experience, only of expertise in a particular area.

Terry, my mentor and coach for the last fifteen years, gave me something unexpected and extraordinary, which turned out to be even more potent and profound than the skill—learning the Total Immersion approach to swimming—that I came to acquire from him. He never consciously sought to teach it to me, nor I to learn it from him, and yet it sustained me through the most terrifying experience of my life, and continues to unfold its riches. In addition to making a sleek and speedy swimmer out of me, he taught me the uses of adversity.

Thus began over a decade-long, and still continuing, dialogue between us that metamorphosed from focusing on the technique of moving joyfully and expertly through the water (or, as he would say, “with the water,”) to considering the psychological (I’m a psychoanalyst) and philosophical implications of his innovative approach. His approach, painstaking, patient, and passionate, transformed me into an athlete for first time in my life, and I became what I called the “guinea fish” on which he tried out his constantly evolving ideas. I worked with him practically every week, and the lessons were a highlight of those weeks. The water became both my refuge and a source of intellectual stimulation.

At first I felt intimidated by his prowess—was I good enough to study with such a teacher? But I need not have been, because I never known a more accessible or generous expert in anything. The thing that particularly suited him to his vocation was that the sport he revolutionized never came easily to him; he wasn’t a naturally gifted athlete. He hadn’t even been good enough to make the sixth grade team at his Catholic school. And yet he became, in middle age, a champion distance swimmer, and an attuned and inspiring coach with an international reputation, whose mission was to illuminate the sensual and spiritual joys of being in the water by reimagining how human bodies, with their inconvenient appendages, move most efficiently in that alien element.

Terry’s motto, bas ed on his life experience as well as his unusually optimistic temperament, was “Injury is Opportunity,” and he took it seriously both in and out of the pool. He himself was no stranger to pain and suffering, since he had sustained many injuries as an athlete, and had to contend daily with a congenital tremor that caused his hands to shake uncontrollably at times. He didn’t just profess this attitude; he embodied it, never complaining or feeling victimized by something that would have seriously frustrated or depressed most people. He swam through it, with remarkable eclat, and approached his students’ physical limitations and psychological struggles the same way he handled his own.

ed on his life experience as well as his unusually optimistic temperament, was “Injury is Opportunity,” and he took it seriously both in and out of the pool. He himself was no stranger to pain and suffering, since he had sustained many injuries as an athlete, and had to contend daily with a congenital tremor that caused his hands to shake uncontrollably at times. He didn’t just profess this attitude; he embodied it, never complaining or feeling victimized by something that would have seriously frustrated or depressed most people. He swam through it, with remarkable eclat, and approached his students’ physical limitations and psychological struggles the same way he handled his own.

I had an unexpected opportunity to discover the uses of injury and to put Terry’s philosophy into practice: One day eight years into our partnership, I showed up for a lesson with a number of unaccountable bruises in strange places. Within a week, I was admitted to the hospital with a rare form of dangerously acute leukemia whose only virtue was that it was curable. The cure entailed daily infusions of arsenic for a month as an in-patient, followed by another nine months of the same treatment as an outpatient. It was as awful as it sounds.

The night before I had to start the outpatient regimen, I had an astonishing dream that defined the task before me: Terry and I were standing on the shore of a forbidding body of water. We could dimly see the other shore far off in the distance. This was clearly the course for a very long, treacherous open-water swim that I was about to undertake, finding my way and conserving my strength all alone, through darkness, undertow, jellyfish, and dread. It reminded me of the English Channel, the Everest of swimming, which he had swum as part of a relay team at age sixty, an exceptional feat. On both shores there were massive, rocky, precipitous hills, which I saw that I would have to navigate both going down to the water and coming back up from it—a reference to the treacherous physical and psychological experiences ahead. As much as I dreaded the treatment, I had not consciously realized that it would be as difficult to clamber back up to the normal world at the end of the ordeal as it was to submerge myself in that dangerous, uncharted “ocean” of pain and fear at the beginning; the two struggles were of a piece. The scene was a physical representation of, and a psychic preparation for, what lay before me.

But I was not alone. Terry turned to me and said, in his calm, direct manner, “There is much to be learned from these daunting cliffs.”

I awoke deeply relieved, confident, with a mission—to be a student of my own experience, just as I was in my swim lessons—rather than a victim. I knew what I was facing, and that, arduous as the labor would be, it would offer me something priceless.

I clung to the dream image, and to his voice, throughout my ordeal. For the next nine months, I returned repeatedly to this dream. Terry’s pronouncement reminded me that I could, and I would, convert suffering into knowledge. He was telling me that this “race” was, blessedly, finite, and that I had the will and the expertise, not just to endure it, but to win it.

***

The most recent lesson I had with Terry was a phone conversation, facilitated by Carrie and Terry’s eldest daughter, Fiona, from his hospital bed the week before he died. His last words to me, which I shall never forget, were “We’ll have more lessons.”

That has already proved to be true. I hear his voice whenever I swim. Every time I get into the pool, I thank him and dedicate my swim to him, resolving, as he taught me, that it will be the most satisfying one I ever undertake, and the most joyous.

And I know I’ll continue to have lessons with him, and hear his voice, in the water and out, for the rest of my life. He will help me understand how to swim, how to live, and how to die.

The post Terry Laughlin as a Mentor In and Out of the Water appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 15, 2017

Swimming That Changes Your Life…How?

Shane Eversfield is Founder and Head Coach of Kaizen-durance, serves as a Total Immersion Master Coach, and is an accomplished ultra endurance athlete. Shane and Terry met after Terry read Shane’s first book “Zendurance”.

Shane enjoyed countless hours swimming and dialoging with Terry. (And they cooked many meals together too!) Frequently their discussions centered around endurance sports as a highly effective form of mindfulness practice, and how mindfulness skills enhance the quality of our lives in every area.

Can swimming really change your life once you pull off the goggles and leave the pool? Let’s explore one way this is possible – through a process called the “Fitness Cycle”.

Why do we swim?

Some of us jump into the cold water of our community lap pool simply for mindful exercise, with no specific athletic goals. We’re just looking for some exercise and some quiet time. Some of us swim each time with a structured “game plan” to train for a specific event, striving for a goal pace and time. Regardless of whether we are recreational or goal-driven, each time we swim or engage in any form of exercise, we are engaged in the first phase of the Fitness Cycle.

The Fitness Cycle

There are three phases in the Fitness Cycle:

- Stress

- Recovery

- Adaptation

When we are actually exercising, we stress our bodies. When we finish, we shower, rest and eat to support our bodies to recover. If we are consistent and wise with the balance of stress and recovery, our bodies will adapt to make us stronger and fitter.

The Balancing Act

As TI Swimmers, we know that balance in the water is Priority #1. Balance is the most empowering skill we bring to swimming. Our success at orchestrating the Fitness Cycle also requires balance, and determines how much fitness we can build. If we don’t really stress our bodies much at all, we won’t stimulate the capacity to adapt. If we stress our bodies beyond the rate at which we can recover, we won’t be able to adapt. The long term effect of consistent and sensible training is a gain of fitness specific to that activity, at the intensity and duration we have trained for. It’s a balancing act.

As we improve our skill set for orchestrating the Fitness Cycle, we can use swimming and other forms of physical activity to change our lives by transforming aerobic fitness into life fitness. How is this possible? Growth and improvement in every area of our lives occurs through the same three phases of the Fitness Cycle – stress recovery and adaptation.

The Real Secret

We “maximize return on our aerobic investment” when we use the fitness we gain through aerobic training to improve every area of our lives. How?

Here’s the secret: Develop a healthy and empowering relationship with stress. There are three ways we can relate to stress:

- Avoid

- React

- Respond

- If we avoid stress, we will not grow, because we never even engage the Fitness Cycle. We feel stagnant, bored, unchallenged, and are often depressed.

- If we react to stress, we resist it. This requires energy and force, and often compounds the stress. In our daily lives this occurs when we blame someone else or some circumstance for the stress we are experiencing. We make ourselves the victims of the stress. As victims, we disable our own capacity to recover. We feel stuck in the stress, angry, resentful and disempowered.

- If we respond to stress, we embrace and accept it. This does not mean we “like” the stress. However, we use the stressful experience as an opportunity for growth and fitness. Isn’t this true every time we exercise?

The Power of Choice

When we swim, we embrace the discomforts of cold water, aerobic exertion and effort, and limited access to oxygen. When we run, we welcome the hot, cold or rainy weather, the discomfort of impact with every foot fall, the effort to run up the hill. Why do we embrace these discomforts? We know that growth and fitness first require stress. We are clear about our choice. Our choice is to respond to stress.

Three Skills

Here are three skills we can develop every time we swim, bike or run to empower our relationship to every form of stress in any area of our lives:

- Patience

- Trust

- Curiosity

With patience, when we first encounter stress, we can pause. In that pause, we can acknowledge the urge to avoid or to resist the stress. Every time you lace up your shoes to head out the door and run, or put on your swim suit and brace yourself for the that cold plunge, you can use that ritual to pause and check-in with yourself. Notice any reservations you may have. Be present for a moment with your fears, with your reluctance, your resistance. Acknowledge and embrace them. And then consider why you are choosing to embrace and experience this stress. What are the benefits?

With trust, we can choose to respond. As we begin to run or swim, we trust our own experience and skills to respond masterfully to the stress that arises. After all, we have done this before, many times. The most valuable thing we must trust is our own sense-felt experience. If we can clearly perceive exactly what is arising in this moment, we are most apt to respond brilliantly. This is precisely how we can continue to refine and improve our efficient swim technique when we don’t have a coach to guide us. Through our sense-felt experience of how we move through the water, the water becomes our coach!!

With curiosity, we pique our senses. We let go of our judgements and attitudes and truly attend to what is arising in this moment. This is when brilliance arises. Zen culture recognizes “Beginner’s Mind” as an attribute of mindfulness and mastery. “In the mind of the Beginner, there are infinite possibilities. In the mind of the expert, there are very few.” Beginners are curious.

Training Fitness in Everyday Life

We have the opportunity to train life fitness in every area of our lives, whenever we encounter stress – if we choose to respond, rather than avoid or react. The training skills we develop through our formal practice of swimming empower us to transform stresses of daily life into life fitness through the Fitness Cycle.

Each day, make a commitment to practice your power of choice at least once in each of these three areas:

- Exercise: Your formal practice of swimming, biking, running, etc.

- A mundane task: Washing the dishes, cooking, any household chore

- Relationships: Every relationship from the most casual to the most intimate

Practice Your Power of Choice

It’s probably easiest to practice your power of choice every time you exercise. That’s why I choose to exercise as early in my day as I can. I skillfully respond to stress and experience balance and harmony. This prepares me to transform the stresses I encounter in the rest of my day into life fitness.

Mundane tasks may not feel stressful at all. Instead they seem boring or annoying. However, these ordinary chores are a great opportunity to hone our skills of patience, trust and curiosity. With patience, we can perform them well. We can trust that there really is time and energy to do them well. If we approach the mundane with curiosity, we perform with brilliance.

Relationships are perhaps the most challenging arena. It is easy to blame the other person when we experience discord and make ourselves the victim. Embracing the stress we experience in relationship and transforming it into life fitness for both people is a high level skill that requires patience, trust and curiosity. Patience and curiosity empower us to really listen and to accurately perceive what is true for someone else outside of our own point of view. And we need trust to let go of our defensive point of view and experience what is really true.

Streamlining and Relationships

In swimming, we are rewarded when we seek the path of least resistance and greatest harmony through the water. We call it streamlining. Our streamlining skills are quite valuable in relationship as well. We don’t blame the water for creating resistance, and we don’t fight it. Instead, it becomes our guide to efficiency and grace. The same is true when we experience resistance in relationships.

Fitness for Life

Every moment of our lives offers us an opportunity to strengthen our fitness and change our lives. The secret? Moment-to-moment throughout each day, we must constantly choose to respond to stress. When stress arises, pause. Summon your patience, trust and curiosity – skills you use every day to enhance and further your swimming practice. And then move forward with the balance and grace you embody.

Shane is the producer of Zendurance Cycling, available on DVD in the Total Immersion online store. To learn more about Shane “Zenman” Eversfield visit the Kaizen-durance website.

The post Swimming That Changes Your Life…How? appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 9, 2017

A Tribute to Terry Laughlin

Message from Terry Laughlin’s wife, Alice, and daughters, Fiona, Carrie, and Betsy:

After living with metastatic prostate cancer for two years (about which he blogged widely), Terry passed away on Friday, October 20th, 2017, of complications related to his condition. He displayed his characteristic optimism, wit, and passion for life– and swimming– until the very end. Our family is in mourning and we ask that we be given time and space to grieve a beloved husband and father privately. While he was “Ter” and “Dad” to us, we fully recognize that Terry was also a legend in the swimming world and admired by countless people whose lives he touched in meaningful ways. We appreciate the well-wishes of Terry’s many friends, fellow coaches, students, and fans. A formal obituary is forthcoming and plans for a public memorial, including several memorial swim events, will be announced for 2018.

We’ll be using this page to post remembrances from Terry’s friends, family and staff, as well as obituaries and recent interviews he gave. If you’d like to share a memory or photo please send an email to info@totalimmersion.net.

Terry with TI staff (Keith, Tracey, Angela)

Message from Keith Woodburn, Operations Director:

Like many of you reading this I’m still having a hard time accepting the fact that Terry’s gone – that he’s not in his home-office typing away at a blog post, or working on his book….or taking the best swim of his life. One reason this is so difficult to come to grips with is that Terry still had so much to give. His creative fire burned bright until his last days, and even in the face of a terminal illness he approached life with optimism and a plan for improvement.

I’m forever grateful to have been Terry’s right-hand-man and to have had the chance to work with a true visionary. Terry put his full trust in me and took a sincere interest in my development and well-being. I can honestly say that in my 15 year tenure at TI I’ve never had to compromise my values, or do work that challenged my integrity. That in itself is an enormous gift.

Terry was an entrepreneur in the purist sense of the word. He was on a mission to change how swimming was taught all over the globe – the business was a byproduct of that passion. Terry stood tall in stature and influence, and to some he appeared larger than life. But those who knew him well were struck by his child-like curiosity about the world, and the optimism with which he confronted life’s challenges and rewards. Terry showed us that if you focus on what’s important to you, and bring a clear and open mind, the work becomes enjoyable. The work becomes its own reward.

While I mourn the loss of my mentor and friend, I find comfort in considering the body of work and the company he leaves behind. Total Immersion allowed him to to devote himself to the urgent task of improving lives and changing the world, one swimmer at at time.

Nothing in life is guaranteed, and Terry’s passing reminds us of that. But one thing that’s certain is his legacy will live on. Total Immersion – a platform for swimming innovation – will live on.

Farewell my friend, I’ll see you on the other side of the lake.

Message from Tracey Baumann, Director of Coaching Services and TI Master Coach:

I first met Terry in Los Angeles. He was swimming in an ocean race and as I stood on the shore watching a huge pod of Dolphins appeared, and starting playing in between the swimmers. Dolphins have been my favourite animals for as long as I can remember. I stood there on this beautiful beach in LA watching my favourite animal and my mentor/idol swim together. It was one of the most surreal and awesome moments of my life, and one I will never forget.

I feel privileged to say that I then went on to be able to work very closely with Terry over the next few years and ended up being on his main TI Central staff helping Keith and Angela run the business. During our weekly Skype calls we would discuss pressing matters on our agenda, but Terry always managed to tell us a story of a swim or an amazing person he had met, or to chat to us about what he was currently writing. During his many visits to Windsor, UK, we would often be in hysterics with tears rolling down Terry’s eyes as he laughed at a Youtube video or a story he was reciting – not to mention his many hilarious impressions.

Terry was a true genius. I was endlessly in awe of his general knowledge and I will be forever thankful for all I learned from him about swimming. He challenged me as a coach and made me the coach I am today, and I hope my skills and knowledge will continue to grow for years to come. I would not be the person or coach I am today without having met and worked so closely with Terry. A huge void has been left and I am still in utter disbelief that Terry’s gone. His legacy will thrive because of the commitment of TI coaches and swimmers, and the strength of the methodology that he developed.

As the quote says below – Terry sure gave us all so much for it to be impossible to forget him and therefore he will live on in every stroke I teach and every stroke any of us swims.

“It’s hard to forget someone who gave you so much to remember”

Happy Laps Terry! Until we meet again.

Message from Angela Dorris, Events Director:

I learned so much from Terry. He was a positive mentor and the most empowering leader I’ve ever worked under. His solutions were creative and he loved to lead others toward outside the box thinking. What a gift to be around someone that approached everything with kindness and creativity.

Our final swim together was the Monday after an open water camp ended in Rosendale, NY – just down the road from where we live. He called to ask what time I would return to the lake to pick up supplies, and if I’d like to join him for a swim. Though it was August, it was a chilly morning and it was raining. But that didn’t dampen our spirits. The swim was nothing short of fantastic, and a good reminder that we can always pause to make room for what is important.

I’ll be forever grateful for all Terry taught me and feel lucky to have known and worked with him. I’ll be swimming some happy laps for you, Terry.

Terry Laughlin, Who Taught Swimmers Not to Struggle, Dies at 66

Terry Laughlin, who developed a popular method of swimming instruction that emphasized form over speed to help thrashing swimmers learn to glide through the water, died on Oct. 20 in Albany. He was 66.

His daughter Fiona Laughlin said the cause was complications of metastatic prostate cancer.

Mr. Laughlin (pronounced LOCK-lin) became a coach after competing as a swimmer in high school and college. Early on, while observing his swimmers in the pool, he noticed that those with the fastest times usually completed their laps with the fewest strokes, slipping through the water with ease instead of struggling against it.

Conventional swimming instruction at the time called for vigorous kicking and arm strokes in expending a maximum amount of energy for a faster lap time. Competitive swimmers endured endless laps and strength training without concentrating much on the manner with which they moved through the water.

“Only about 2 percent of the human race swims with instinctively long strokes,” Mr. Laughlin told The Washington Post in 1999. “The rest of us have powerful instincts telling us to swim faster by stroking faster.”

Mr. Laughlin studied the motions of the best swimmers, along with hydrodynamics, kinesiology and ship design, to develop a better way to swim. He first taught a class on what he called Total Immersion Swimming in 1989.

CONTINUE TO NEW YORK TIMES OBITUARY

EX-USMMA and USA Swimming Coach Terry Laughlin Dies at 66

Terry Laughlin, who was cut from his junior high school swimming team but went on to coach successfully at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point and revolutionize the sport with his teachings, died Oct. 20 at his home in New Paltz.

Laughlin, 66, who was from Williston Park, lost a battle with prostate cancer according to information posted on totalimmersion.net, named for Total Immersion Swimming, the company he founded in 1989 that taught the sport to adults using a then-radical style that became popular over the years for swimmers of all ages and levels.

“His technique is very innovative. He changed the direction of swimming and will continue to do so,” said USMMA men’s swimming coach Sean Tedesco. “The style can be used for all ages. I use it for clinics and for college when I teach. From little kids to Olympians the technique is all the same, if taught properly.”

Laughlin’s “total immersion” method utilizes a ‘fishlike’ style of swimming that emphasizes streamlining bodylines instead of muscling the water with arms and legs.

Laughlin remained a serious swimmer into his 60s and, according to his blog, completed a Corsica-to-Sardinia swim of nearly 10 miles in 4 hours, 31 minutes, with two friends in 2015.

Terry Laughlin, Founder of Total Immersion, Passes Away at 66

Terry Laughlin, who created the technique-focused swim training system known as “Total Immersion,” passed away Friday, Oct. 20, after complications with prostate cancer. Laughlin was 66 years old.

Laughlin is survived by his wife, Alice, and daughters Fiona, Carrie and Betsy. The family announced his death Monday:

“After living with metastatic prostate cancer for two years, Terry passed away on Friday, October 20th, 2017, of complications related to his condition.