Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 5

April 12, 2019

PRACTICE CUES: Kaizen Focal Point Checklist For Transition From Drills to Whole Stroke Swimming

One of the single most common questions that T.I. swimmers ask after first learning the T.I. drill process and technique-focused approach is: “How do I apply what I’ve learned in the drills to my whole stroke practice?” To help guide our students with integrating T.I. skills in the transition to whole stroke practice, we have long provided a companion instructional manual to our workshop attendees. Below is an excerpt from a workshop manual that Terry Laughlin adapted from his 2006 book “Extraordinary Swimming for Every Body,” providing practical suggestions to guide T.I. swimmers through the first several weeks or months following a T.I. workshop. This post highlights a detailed list of freestyle focal points that aims to answer the question of how to transition the skills of T.I. drills to whole stroke swimming– an indispensable aid for both new T.I. swimmers and long-term kaizen learners! Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

SELECTED EXCERPT FROM:

“KAIZEN SWIMMING: HOW TO MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR TOTAL IMMERSION WORKSHOP”

DEVELOP YOUR STROKE

This phase of practice can last a lifetime for those most committed to Kaizen Swimming, but it should certainly last between one and several years. Your minimum goal is to swim whole stroke with the same degree of balance, ease, and control that you enjoy in the drills. You do that by:

(1) Learning to swim balanced and tall

(2) Learning to breathe rhythmically without interrupting your flow and while keeping a hand extended and anchored

(3) Learning to start each stroke with a “patient hand”– taking time to trap the water with hand/forearm before stroking

(4) Develop “gears” by establishing an SPL (strokes per length) range of three to four 25 yd/m stroke counts (e.g. 14-17 strokes per length, calibrated precisely according to your chosen pace) at which you can swim efficiently… and be able to swim 400-1500 meters without exceeding your SPL range… and to swim sets of shorter repeats (repeats of 25-200 yd/m in sets that last 10-20 min.) in the lower half of your SPL range

PRACTICE TIPS

Following a period of intensive drill practice, you have two priorities: (1) Apply what you’ve learned in drills to whole-stroke and (2) Begin imprinting an economical stroke into muscle memory. The two key ingredients are Drill/Swim Set and Mindful Swimming. Earlier in this practice guide Coach Brian Van de Krol gave great guidance on Drill/Swim sets. [Those particular drill/swim sets will be shared in a separate blog post in the coming weeks.] Basically, take what feels good in the drill and make it feel the same while swimming whole stroke. At first, it might take you 75 yds of a drill to get a clear idea of the sensation you’re trying to replicate, and you might be able to “hold that feeling” for only 25 yds of swimming. With time, that mix should become 50 yds drill and 50 whole stroke, then 25 drill and 75 whole stroke. Prioritize clarity by having a specific focus at all times and keeping that focus from drill to whole stroke. For example, if you practice Skating with a focus on establishing “wide tracks,” then focus on following those wide tracks in whole stroke.

When you increase your whole-stroke practice, it’s best to simplify your task and heighten your focus with Mindful Swimming. Pages 115-127 of “Extraordinary Swimming for Every Body” [available for purchase– follow this link to the T.I .Store] provide a detailed context for all Freestyle Focal Points. Here is a consolidated list to begin your freestyle practice.

FOR BALANCE

Completely release the weight of your head to the water

Imagine a laser beam coming from your head-spine line– keep it pointed forward

Feel that the back of your neck is lengthened

Hang your extended hand– keep fingers below wrist and wrist below elbow

FOR LATERAL STABILITY

Keep extended lead hand outside of shoulder

Follow “Wide Tracks” with recovery and extension

Rotate only enough for shoulder to clear the water

FOR LONG, SLEEK BODYLINES

Spear hand forward to a target located in Skating and reinforced in Switch drills

Line up your body to follow your spearing hand down the track

Keep legs inside the “shadow” or slipstream of your body

Always have a hand forward of your head

FOR RECOVERY AND ENTRY

Ear Hops– Hop fingers over an imaginary bar coming from your ear, then into the water

Marionette Arms– Hang hand/forearm from your shoulder like a marionette or rag doll

Mail Slot– On entry, slip hand and forearm through a visualized mail slot forward of your shoulder

Soft Hand– Entering hand should be relaxed enough that fingers separate loosely

HOLD YOUR PLACE

Enter fingers opposite the elbow of extended hand

Pause hand– fingers down– for a brief moment before stroke

Trap the water behind hand/forearm before stroking

Hold– don’t pull– as best you can

PROPEL EFFORTLESSLY WITH YOUR CORE

Spear your entering hand past your grip

Spear your hand through the target established in Skating and Switch drills

Drive down the high hip as you spear

Count strokes with hip drives instead of hand entries

Drive opposite foot as you spear your hand

Finish each stroke to the front

BREATHING

Bubble out immediately and continuously after inhale

Blow out the final 20% more forcefully as you roll to air

Use the spearing hand to take you to air

Follow shoulder back with your chin and look past your shoulder

Keep the top of your head down, aligned with spine

Get taller as you roll to breathe; stay taller as you return face-down

KICKING

Legs should be as passive as possible (if you came to workshop with “busy” legs)

Keep kick as small and “neat” as possible

Try to close feet briefly as you spear

Kick from “gut” and top of legs– don’t feel it in your thighs

Synchronize left foot drive with right hand spear and vice-versa

AND FINALLY

Do everything as quietly as possible– drilling, swimming, increasing speed or cadence

Never Practice Struggle

If you’re counting, that makes 38 different focal points– but it’s not an exhaustive list. I’ve used every one of these, some for hundreds of thousands of strokes, others for tens of thousands. All have contributed something meaningful to my efficiency. I never take a stroke– in training or racing– without thinking about one of them. Each focal point works on a particular part of the stroke. And each lap you consciously focus on, for example, slipping your arm into a mail slot, faintly imprints a new groove in your nervous system. After 5 or 10 minutes thinking only about that, it will feel a bit more natural and improve the chances that you’ll continue doing it when you’re thinking about something else.

Through practice, you’ll narrow the list to a few particular favorites. Once you do, you might note those on an index card and laminate, or put it in a Ziploc baggie and take it to the pool with you. Put it at the end of your lane, and then do several 25s of each “cue” on the card. Take enough time between reps to catch your breath and think about how you feel. As they become easier, progress to 4 x 50 of each cue. Then, 4 x 75. The level of focus required to do these and groove them into your nervous system makes the time fly, so enjoy this exercise in Mindful Swimming, while you build efficiency and fitness.

The post PRACTICE CUES: Kaizen Focal Point Checklist For Transition From Drills to Whole Stroke Swimming appeared first on Total Immersion.

April 5, 2019

PRACTICE STRATEGY: Learning How We Learn Any New Skill Is the Key to Kaizen Swimming Mastery

Terry practices “chunking” several mini-skills during this breath rehearsal drill

Terry practices “chunking” several mini-skills during this breath rehearsal drill

One of the most distinctive and effective aspects of the T.I. approach to swimming is not merely our focus on efficient technique– it’s the way in which we approach the learning process itself. “Meta-learning”– or learning how to learn– is a key element of how we pursue swimming as a path for kaizen mastery (continuous, life-long improvement). We set clear intentions through deliberate practice of specific and discrete skills, and every feature of practice is purposeful, designed to sharpen our mastery of even the subtlest movements within a swim stroke. The complex movements of whole-stroke swimming are deconstructed into its simpler skill components (“mini-skills”) for ease of learning and practice, building the stroke piece by piece, from the ground up. Teaching though this building-block method has always been an integral part of the T.I. process and our swimmers’ success, as each drill and skill in our learning progression builds upon the previous drill and skill. A credo Terry often quoted from the U.S. military is the philosophy that “Slow is smooth and smooth is fast”– it is imperative to learn and master foundational skills at slow speeds in order to perform them impeccably at faster speeds and in more complex movements. This September 2016 post from Terry is an in-depth look at how T.I. applies the specific learning strategy of “chunking”– breaking a component into smaller “chunks” of related information– to the practice of swimming, and how this approach is a key to your success in swimming mastery.

September 13, 2016

At some point, all kaizen swimmers employ a learning strategy that cognitive scientists refer to as “chunking.” Chunking refers to grouping separate pieces of information together to facilitate learning by remembering the groups as opposed to a much larger number of individual pieces of information. The types of groups can also act as a memory cue. In TI we group by body segment (head, torso, arms, legs) and skill type (Balance, Core Stability, Streamlining, Propulsion).

We learn to read via a chunking process. First, we learn the sounds of individual letters which assemble into words we generally know before beginning to read. Three individual letters (d-o-g, c-a-t) form a group that represents a family pet.

Next, we combine a series of words into a phrase or sentence. Via several additional chunking steps we may acquire the skill of speed reading, in which we rapidly scan pages of text, identifying key phrases which convey the main ideas of what we’re reading.

Chunking is a key strategy for learning complicated physical skills such as swimming. In T.I. methodology, we call this approach “Blend-and-Harmonize”– as in, blend several discrete mini-skills, then bring the new skill set into harmony with the whole stroke.

Long before I knew of it as a learning strategy, I instinctively employed a chunking process to learn new skills. This first occurred nine months before the first T.I. camp, before I’d chosen the name Total Immersion, or even thought of offering a swim camp for adults.

The first skill was Balance, to which I was introduced by Bill Boomer. Bill taught me to align my head with my spine and shift weight forward to my upper chest. We called it “swimming downhill.” Practiced together, these two skills (aligning head and spine; shifting my weight forward) made my legs feel light, something I’d never experienced in almost 25 years of swimming.

From the start, I realized that I couldn’t fully concentrate on both of these new thoughts or sensations at once. So I’d spend 10 to 30 minutes concentrating on feeling a straight line from the top of my head to the base of my spine. Then I’d focus on leaning on my upper chest (we no longer teach balance this way) for a similar duration. This particular approach is called “Block practice.”

After several weeks, I felt sufficiently familiar with both sensations to begin alternating them—focusing on head-spine alignment one length and swimming downhill on the next length. This approach is called “Random practice.” (Note: I also practiced a head-lead balance drill—similar to today’s Torpedo—that highlighted both, giving me a heightened sensory benchmark to aim for in whole stroke.)

After another few weeks, I began to blend the two thoughts. One length focusing on head-spine alignment, one length on swimming downhill, and a third length blending the two thoughts/skills. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Now I was “Chunking.”

I learned later that sequencing Block, Random, and Chunking practice (the names for which I didn’t even know when I began doing that) accelerates transfer of skills from conscious to autonomic control. Or to use a more familiar phrase: Forming a Muscle Memory.

It took me about five years of similar experimentation to achieve Balance in even a rudimentary way –it felt great at the time, but I didn’t yet know how much better that sensation would become in the years ahead. Over the next 10 years, I continued to discover new mini-skills—like the Mail Slot entry and reaching below my bodyline–that improved my sense of weightlessness in the water.

But the bottom line is that Balance originally occurred to me as several discrete skills, which I focused on and sensed individually. After the passage of time– and without my realizing consciously what had occurred– the multiple, individual sensations consolidated or “chunked” into a single awareness I call “Swimming in Balance.”

When Balance became a single, seamlessly-integrated “sensory package,” that freed up mental bandwidth to add new skills—Stability, Streamlining, Propulsion, and Breathing.

It would be many years before I read about chunking as a learning strategy and I could apply that term to what had occurred to me– finally, I could articulate the theoretical framework to describe how I’d intuitively been practicing all along. Both before learning about chunking, and since then, I’ve developed countless skills by the same process.

For instance—as outlined in the 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course—I achieved a far more refined and efficient freestyle recovery by breaking it into three discrete mini-skills, each of which occupy only a micro-second in the stroke—Elbow Swing, Rag Doll Arm, and Paint a Line.

As brief as these mini-skills are, I have a keen awareness of each, acquired by applying the proven sequence of Block, Random, and Chunking (or “Blend-and-Harmonize”) practice to them.

Fast forward to the present day: I have a far more expansive and holistic “chunk” to which I could give the term “My Utterly Blissful Freestyle,” which integrates six to eight sizable chunks of skills that I’ve developed over the years.

Accessing such high level sensation used to be hit-or-miss. It often took 30-60 minutes to “find” the peak feeling I’d acquired at that point. Now those high quality sensations are absolutely dependable—always there–and I can consistently access them within just a lap or two.

Learn all the skills of efficient freestyle with the Total Immersion Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course!

The post PRACTICE STRATEGY: Learning How We Learn Any New Skill Is the Key to Kaizen Swimming Mastery appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 29, 2019

How To Swim Efficiently: An Excerpt from Terry’s Final Book

An exclusive excerpt in an ongoing series of material from Terry’s forthcoming final book, Total Immersion: Swimming That Changes Your Life

Over the last year, this blog has released several excerpts from the unpublished draft of Terry’s final book, of which he was nearing completion when he passed away in October 2017. It is currently being edited– for anticipated release sometime in 2019– and this week’s post is another exclusive excerpt from his book. This post is adapted from an early chapter of the book, entitled “How To Swim Efficiently.” In this piece, Terry details the origin and evolution of T.I. techniques; their foundations in the laws of physics, fluid dynamics, and biomechanics; the characteristics of an efficient swim stroke; the T.I. “Pyramid of Skills”; and how our approach has been refined over 30 years and thousands of swimmers. Terry also discusses the ease and grace that is typical of the T.I. stroke, noting the popularity (9+ million views) of a YouTube video of TI Japan Founder and Master Coach Shinji Takeuchi demonstrating T.I. freestyle. If you’ve never seen this remarkable video, we’ve embedded it– and another brief video demo by Terry of the “Elements of Effective Swimming”– within this article as vivid illustration of impeccable technique. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

How To Swim Efficiently

Five-time Olympic running coach Bobby McGee refers to running as “primal” – something we do well by nature. ChiRunning founder Danny Dreyer talks of helping runners rediscover the instinctively relaxed and efficient way they ran as children.

Swimming is precisely the opposite: As you read in the last chapter, in the water we become energy-wasting machines. To develop a high-efficiency stroke, you must make a conscious choice to eliminate energy waste—and renew that choice every time you swim. You’ll need patience and persistence to resist a return to old habits so that new ones can take root.

This chapter details the origin and evolution of TI techniques; their foundations in the laws of physics, fluid dynamics, and biomechanics; and how they were refined over 30 years and thousands of swimmers.

While the efficiency principles described here apply to all strokes, this book focuses primarily on freestyle.

Seeking Grace

When you’re at the pool, what kind of swimming catches your eye? A swimmer going fast, or one who swims with consummate ease and grace?

On YouTube, the most popular swim video [embedded below] is TI Coach Shinji Takeuchi’s “Most Graceful Freestyle,” which has been viewed more than 9 million times since it was posted in 2008. In second place, with some 5 million views, is a video of Michael Phelps which was posted a year earlier.

Why are so many more people interested in watching an unheralded, middle-aged man than the most decorated swimmer ever? Could it be because grace is a much rarer quality in swimming than speed? And yet—as Shinji, and thousands of other TI swimmers, have shown—grace is attainable, while Phelps’s kind of speed is available only to those with youth, strength, and special talents?

You’ll see countless references to efficiency in these pages. Think of grace as a warmer word for efficiency—and one that’s more accessible. While few of us feel qualified to assess a swimmer’s efficiency, we know it when we see it because all of us feel comfortable recognizing graceful movement vs. ragged or ugly movement.

With human’s baseline efficiency at just 3 percent in swimming, there are nearly limitless opportunities to improve it—with the result of swimming any distance with far more ease and enjoyment, while taking far fewer strokes.

Saving energy will take you almost effortlessly from first strokes, to first comfortable lap, to first mile, and even to a faster mile. When you swim your first continuous mile—and feel energized upon finishing— your stroke is likely to display these characteristics:

Balanced: You feel well-supported by the water—even weightless. This is the characteristic that enables those that follow.

Long: You travel more than the length of your body on each stroke cycle (right plus left arm). When you do, your hand will exit the water, at the conclusion of each stroke, about where it entered.

“Slippery”: You fully extend your bodyline on each stroke, and minimize bubbles, noise, and splash in your stroke.

Integrated: You take each stroke with your whole body—limbs, head and torso–working in seamless coordination, not disconnected parts.

Relaxed: You appear relaxed—never strained–even while swimming at a brisk pace.

And finally, you always feel great while swimming—and better after swimming than before.

A Groundbreaking Way to Learn Efficiency

Prior to 1990, I spent nearly two decades coaching club and college swimmers in their teens and early 20s. My highest-performing swimmers-–especially those who won national championships or achieved world rankings—had the best-looking strokes. That motivated me to prod all my athletes to swim with the best form possible at all times.

In maintaining high technique standards for my athletes, I had the luxury of coaching a group of just 15 to 25 swimmers six days a week. And finally, these swimmers were all from the rarefied group ‘inside the bubble’ who—seemingly from birth—were very much at home in the water.

In the early 1990s, I faced a challenge for which all these years of experience had left me unprepared. At each T.I. weekend workshops, some 20 or more inexperienced, and mostly self-coached, swimmers showed up seeking instruction. We had just two days to prepare these new swimmers to successfully coach themselves.

This required an entirely new way of teaching swimming technique—a process that:

1) Could be standardized for many swimmers

2) Would quickly solve significant challenges

3) Be simple enough to follow on their own

Using Bill Boomer’s insights as a starting point, T.I. workshops became a laboratory for refining an all-new approach to improving technique.

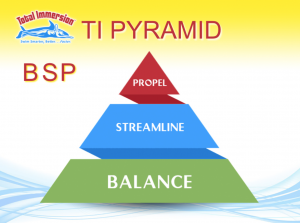

The Pyramid of Skills

Learning three skills—in a particular order—has proven to be virtually a sure thing in learning to be efficient. It helps to view these skills as a pyramid.

Balance provides the body control and mental calm essential to learning every skill that follows. Learning Balance replaces the sinking sensation with a comforting sense of feeling ‘weightless’. You accomplish this by working with—instead of fighting—gravity.

Streamline skills come next because water is 880 times denser than air. Why waste energy trying to overpower water resistance when you can reduce it quickly and with relative ease? You accomplish this by shaping your vessel to slip through a smaller ‘hole’ in the water—and by using your limbs as much for minimizing drag as for creating propulsion.

Propulsion skills follow the others because they require a stable body, a high level of coordination and keen self-perception. Yet you can learn them with striking ease after establishing Balance and Streamline skills. You accomplish this by originating power and rhythm in the core and by propelling with your whole body, not your arms and legs.

Besides offering a proven way to become efficient, this sequence of skill acquisition offers these advantages:

Immediate Energy Savings

As energy-wasting machines, we must consider the energy cost of every aspect of swimming—starting with our learning process.

Balance skills focus on relaxing, floating, and extending. These require virtually no energy and lead to immediate, significant energy savings. As well, balance is the key to swimming at the equivalent of a runner’s easy ‘conversational’ pace. You could well be swimming farther after 10 to 20 hours of balance practice than following months of endurance training.

Streamlining skills—lengthening and aligning the body– require only slightly more energy than those for Balance. And, because drag–and the power needed to overcome it–increase exponentially as you swim faster, minimizing drag will make your energy savings exponential.

Propulsion actions—those that move you forward—indeed have a greater energy cost than those we use to balance and streamline. We reduce that by using natural forces—primarily gravity and buoyancy—before generating force with our muscles; and by propelling with the whole-body, rather than fatigue-prone arms and legs.

Put the Odds in Your Favor

The Balance→Streamline→Propulsion pyramid increases your odds of success in two ways:

Avoid Failure Points. One of Tim Ferriss’s key strategies for meta-learning is to avoid common “failure points” at the start. For newer swimmers, the two aspects of swimming most likely to defeat you before you’ve barely begun are kicking and breathing. TI technique is explicitly designed to minimize reliance on kicking. And we introduce breathing only when you have the body control and comfort in the water to handle it with aplomb.

A Glimpse of Success In The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg writes that, to replace an undesired habit with an improved one, experiencing a “small win” early provides motivation to persist through challenges you encounter later. The T.I. learning sequence starts with Balance skills, which reveal how it feels to glide weightlessly and effortlessly. For adult novices, that experience is liberating– even thrilling—and comes as a ray of hope for those who had felt hopeless before.

In the next chapter, let’s move straight-away to learning complete details of the three essential aspects of TI Swimming: Balance, Streamlining, and Core Powered Propulsion.

Glad you enjoyed this sneak peak of Terry’s final book– you can learn all the skills of efficient freestyle with the Total Immersion Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course!

The post How To Swim Efficiently: An Excerpt from Terry’s Final Book appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 15, 2019

VIDEO: Swimming Lessons From The World’s Fastest Runner

A still from “Cheetahs on the Edge: Groundbreaking Footage of the World’s Fastest Runner”

The key elements of the T.I. approach– balance, streamlining, and propulsion– are based upon the physics of how bodies move through water, a combination of the principles of hydrodynamics and the principles of biomechanics. It’s interesting, then, to see how these key elements of movement science that we emphasize in swimming efficiently can be observed in parallel examples in other areas of life, be it in other sports or in nature. Inspired by the incredible slow-motion footage of cheetahs captured by photographer Greg Wilson in his award-winning video (video embedded below), this December 2012 blog from Terry Laughlin is an insightful analysis of what humans can learn from the world’s fastest runners about cultivating efficient speed– and how there are analogous connections between the natural speed of cheetahs and the consciously-cultivated speed of T.I. swimming. Enjoy this rare footage… and Happy Laps!

December 3, 2012

I’ve long believed that there are universal laws underpinning the highest skilled movement. Among the simplest is “What Is Most Beautiful Is Also Best.” This extraordinary National Geographic Channel video of the fastest creature on four legs reaffirms my faith in that. These slow motion studies offer an unprecedented opportunity to understand why cheetahs can reach speeds of up to 60mph/97kph. And will probably not surprise regular readers of this blog that I discerned in the cheetah’s running mechanics several matches for key points in T.I. Technique principles (outlined below) — as well as a lesson we could all do well to emulate.

Cheetahs on the Edge–Director’s Cut from Gregory Wilson on Vimeo

Technique Tips from the World’s Fastest Runner

Balance and Stability

The cheetah’s head is amazingly stable.

The cheetah’s head-spine line is always moving in the direction of travel

Streamlining

The cheetah achieves full extension of its bodyline in every stride.

The cheetah uses a compact, relaxed “recovery” (bringing fore paws forward close to the body).

Propulsion

The cheetah runs with its whole body, not its limbs.

The cheetah places its fore paw with striking care — even delicacy. The equivalent in T.I. Swimming is relaxed hands, patient catch, and “gathering moonbeams” (taking care in initiating pressure).

The Lesson

The cheetah sacrifices none of these qualities at its highest speeds and stride rates. In fact it seems to do them most exquisitely when it is moving at maximum speed. It reaches its Maximum Stride Length when it’s also at Maximum Speed — which is, of course, the secret to being the fastest runner on the planet. As we know, human swimmers do exactly the opposite when striving to swim fast. We sacrifice Stroke Length as we increase Stroke Rate– sometimes quite radically. Alain Bernard, while anchoring France’s 4×100 relay in Beijing, being a high profile example; Usain Bolt, in contrast, ran as the cheetah does, achieving his Max Stride Length at max speed. Cheetahs run fast by nature. We must swim fast mindfully.

Additional info about “Cheetahs on the Edge” from director Greg Wilson:

-Winner of the 2013 National Magazine Awards for best Multimedia piece of the year-

Cheetahs are the fastest runners on the planet. Combining the resources of National Geographic Magazine and the Cincinnati Zoo, and drawing on the skills of an incredible crew, we documented these amazing cats in a way that’s never been done before.

Using a Phantom camera filming at 1200 frames per second while zooming beside a sprinting cheetah, the team captured every nuance of the cat’s movement as it reached top speeds of 60+ miles per hour. The extraordinary footage that follows is a compilation of multiple runs by five cheetahs during three days of filming.

For more information about cheetah conservation, visit causeanuproar.com/Director, DP, Producer – Greg Wilson

The post VIDEO: Swimming Lessons From The World’s Fastest Runner appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 8, 2019

VIDEO: How Balance Improves Breathing– And A Practice Set for This Skill

Terry keeping his head low while breathing to the left

This week’s blog is a look back at a Nov. 2010 post from T.I. founder Terry Laughlin on the ever-popular topic of breathing in freestyle: an essential component of swimming with ease and confidence, no matter the distance. Being able to breathe comfortably is the very foundation of being able to swim comfortably– can’t do anything without air! And yet, this primary skill of swimming mystifies and confounds many swim students because our instinctive human impulses to get to the air (lifting the head up, pushing down on the water with the arm as a “brace” to stay aloft during a breath, etc.) contradict the elements of efficient breathing that characterize T.I. swimming. Terry often remarked that virtually every skill of efficient swimming (as opposed to “survival swimming”) is counter-intuitive and he referred to this dilemma as the “Universal Human Swimming Problem” or “UHSP.” Swimmers who struggle are not outliers, he observed, once writing: “Indeed, swimming poorly–or swimming ‘okay’ without realizing you could be swimming much better–is so common we call it the ‘Universal Human Swimming Problem.’” Fortunately, we can transform our reflexively inefficient “survival swimming” through conscious practice of the counter-intuitive skills of efficient swimming. Learning to breathe in balance is a huge piece of solving the “UHSP” and this article addresses that specific issue, offering insights and practical suggestions for how to develop and refine this crucial skill. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

Editor’s Note: The discussion thread Terry mentions below is now archived as a “read-only” thread in the old discussion forum.

November 24, 2010

A focus on Balance shows up virtually every day in one or more threads on the TI Discussion Forum. Today, in a thread titled Back to the Roots, forum member Haschu reported:

This morning I practiced in a 15-meter hotel pool. I watched Shinji’s video of holding Superman Glide for 12.5 m. I wondered how he could glide such a long distance and tried to match that. So I did SG repeats for about 20 minutes, finally reaching 10, perhaps even 12 m.

Haschu continued:

After that, I did a few laps of full-stroke breathing to my left, which is my ‘bad’ breathing side. I’m deeper in the water and always lift my head when breathing left. I could never figure out why. I tried to adjust my right spearing arm and other things, but nothing seemed to work. Yet after that extended period of SG [Superman Glide] my mouth was clear of water as I breathed. I find it quite amazing how much benefit one can gain from very ‘basic’ drills like SG and core balance. I can only encourage everybody to use those drills intensively. They make everything else so much easier.

I’m not at all surprised that extending one’s practice of Superman Glide far beyond what most people would consider resulted in finding the solution to a long-term “breathing puzzle.”

Once you’ve practiced T.I. for several years, most of your Kaizen – continuing improvement – opportunities will be rather subtle. You can swim as far as you like. On the whole you feel pretty good when swimming – perhaps even experience “flow states” (aka: feeling “in the zone”) at times.

Yet – because you tirelessly seek small flaws to improve – you find them. Your “symptom”– feeling a bit lower in the water, and that you lift your head slightly when breathing to the left — is clearly balance-related. But it’s difficult to correct because (to quote Sting) every breath you take reinforces the error.

If you analyze a bit, you realize:

1) Lifting your head causes the “sinking feeling”

2) It probably also means that your right hand is “bracing” rather than extend-and-catch

3) All of this happens because you don’t feel as well supported as you roll to your left

Nothing deepens sense-of-support (and emotional security) like Superman Glide. As well, no drill is quite as good at helping you really, really, really release your head. At first just when looking down. It takes greater focus to keep really, really, really releasing your head as you roll to breathe.

“Really, really, really release your head” while breathing

One way to develop this skill is to repeat SG (Superman Glide) until you feel yourself really, really, really releasing your head while gliding.

Then add some strokes and really, really, really release your head while stroking.

Finally, take a few breaths to evaluate whether you’re still really, really, really releasing your head while breathing. I look for a feeling that the side of my head is floating on a cushion as I breathe. I don’t mind doing 20 minutes of very short, intensely-focused repeats in pursuit of it.

That kind of practice will often look something like this:

4 x SG (7 to 8 yds)

4 x SG + 3-5 strokes (10-15 yds)

4 x SG + 2-3 breaths (15-18 yds)

4 x SG

4 x SG + 3-5 strokes

4 x SG + 3-5 breaths

4 x SG

4 x SG + 3-5 strokes

4 x SG + 4-6 breaths

As I’ve said previously, just because there’s a convention to make pools 25y/m doesn’t mean we always have to swim that far without stopping. I stop in mid-pool regularly when working on an elusive skill or sensation. As I feel it improve, I keep adding one more successful cycle at a time.

15m hotel pools are not so good for lap swimming, but they’re perfect for refining subtle skills, as is extended practice of the more basic drills.

Blog Comment– Troubleshooting Question for Terry

Blog reader Craig: I have tried to find this kind of balance for years, but haven’t [gotten it]! I am 6′ 1″ and 165 lbs. so floating is difficult and my legs are very “heavy” in the water. Is this possible for my bodytype? Thanks for all your great info/videos!

Terry: When you say you’re 6-1 and 165 and so floating is difficult I don’t understand, because many elite swimmers have similar body type. Please don’t confuse “balance” with “floating.” The human body is intended to sink to some extent – i.e. only 5% of body mass will typically be above the surface. Balance means to “sink in a horizontal position.” It’s a skill acquired by specific changes in head and limb position and redistribution of body weight.

Craig: I have tried everything to achieve the “Superman glide,” but still end up with my feet about 3 feet under water as soon as my forward speed is lost. If I blow out my air, then I will sink level, but go straight to the bottom of the pool? I can’t find leverage to keep my chest down and legs up? Thanks.

Terry: Mine sink too . . . at some point. Start stroking while you still have a bit of momentum. Start with 3 to 5 strokes and just one thought.

Learn all skills and drills described in this post– and the other elements of efficient freestyle– in our downloadable product: Effortless Endurance Freestyle Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit

The post VIDEO: How Balance Improves Breathing– And A Practice Set for This Skill appeared first on Total Immersion.

March 1, 2019

HOW TO PRACTICE: Terry’s “Mini-Skill” Focal Point Progression from Drills to Whole Stroke Swimming

Terry demonstrating focal points for the timing of the weight shift, Feb. 2016

This Dec. 2015 photo-illustrated article from T.I. Founder Terry Laughlin is a thorough breakdown of how one can apply several core fundamentals of T.I. technique to a practice session. With great detail, he describes the step-by-step tactical approach of a lesson he conducted with two students. Below, he recounts how he guided his students’ practice with targeted focal points– or “mini skills”– to test how well they could maintain efficiency as they moved from drilling to more seamless whole stroke swimming. Terry’s account of this T.I. practice session with students is an excellent example of how you can integrate foundational technique skills into your own swim practice. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

December 11, 2015

Two days ago I brought two students, Dmitry and Sergey, to Bard College to guide them through a practice that was 100% focused on increasing efficiency via improving technique. They had just completed two days of instruction–four 90-minute sessions in the Endless Pool at our Swim Studio. During the final session, they said they’d like to extend their stay and squeeze in one more session.

Both had radically transformed their strokes during the previous two days. But such rapid transformation isn’t always easy to maintain–especially after returning to the very different environment of a lap pool, and to a setting where the pull to resume old routines may be strong. If we did another session in the Endless Pool, I wouldn’t attempt to introduce anything new–only to review and deepen the skills they’d already learned.

But I felt there could be even more value in testing the new skills in the same environment to which they’d be returning. I proposed we go to Bard College the next morning, where I could guide them through their first post-workshop ‘real world’ practice. The experience turned out to be as valuable for me as for Sergey and Dmitry.

We began by reviewing the first and most ‘non-negotiable’ skill of efficient swimming: Establishing a neutral–and weightless–head position. I had them repeat Superman four times. Glide five yards from wall to backstroke flags. Stand for a breather and return.

On the first two reps both were holding the head slightly elevated. I lightly wagged the head to reveal that they were maintaining slight neck tension. On the next two reps, their heads were fully released and aligned with the spine. The visual cue–shown below–is that only a small sliver of the back of the head is visible above the surface.

Ready for the next step: Add a few strokes to test whether they could continue resting their heads on the water. Would I still see that same small sliver of head as they stroked?

We did four reps of Superman plus 4 to 5 non-breathing strokes. I asked them to assess whether their head position felt the same–with same degree of relaxation in neck muscles–after they began stroking. They passed that test, so we advanced to a slightly more demanding skill.

Could they maintain this new skill for a full 25 yards–14 to 17 strokes rather than 4–and while breathing. I instructed them to push off in Superman, establish the weightless head sensation, take four non-breathing strokes, then breathe bilaterally the rest of the way. Could they maintain a neutral, weightless head while breathing–as shown below?

Sergey succeeded. Dmitry lifted his head while breathing. I asked him to tune into the feeling of having the head rest on the surface during the non-breathing strokes, then check whether he felt the same sensation as he breathed. While he didn’t fully correct this error, it was valuable information to identify this as a problem to be solved in practices that followed. I made a mental note to finish the practice by having Dmitry review the TI “Nod” drill–shown below–which can correct head-lifting in as little as 10 minutes.

Nodding to the left

Following the same sequence, we cycled through several foundational mini-skills. For each cycle, choose ONE Focal Point or Mini-Skill while doing the following:

Do several reps of a standing rehearsal or drill–depending on the skill.

Swim several short reps, transitioning seamlessly from the drill to 4 to 5 non-breathing strokes.

Swim 4 to 8 x 25 to test the durability of the new mini-skill with more strokes and while breathing.

The second cycle was most instructive for all three of us. In our first cycle, I’d observed that both Sergey and Dmitry looked a bit tight, and uncertain, during Recovery. To address this, I instructed them to lightly Paint a Line on the surface with fingertips (hanging from a Rag Doll arm).

First they rehearsed Rag Doll/Paint a Line– as shown below.

Rehearsal: Paint A Line and Rag Doll with right arm

Then they tested their ability to do it while stroking. It should look like this:

In this case, it was Dmitry who succeeded. Sergey’s hand was a bit too close to his body–increasing tension in his shoulder. It was also several inches off the water– an occasion for energy waste, especially when multiplied by the thousands of strokes he would take in a triathlon or open water swim.

A much more important revelation was the keen degree of attention required for new skills that call on fine motor coordination–requiring the cooperation of multiple small muscles. This was an opportunity for a critical takeaway about the Skill of Focus.

Just as with motor skills, one must begin developing mental skills with relatively undemanding tasks. E.G. For just 4 to 5 strokes, can you lightly trace a wide straight line on the surface with fingertips. There’s no point in going farther–either a more complex skill, or swimming a greater distance–until you succeed at this.

To develop the ability to perform complex skills, one must first achieve consistency–and a degree of effortlessness–in a series of much simpler mini-skills.

To acquire the capacity for laser-sharp and unwavering focus– e.g. to remain calmly observant in a chaotic-seeming environment like the start of a triathlon swim– one must first be able to concentrate on doing one simple thing for 25 yards or even less in a quiet pool.

During our practice I was able to not only make corrections to form, but also to leave a much larger lesson: Your goal on each rep is not only to improve a motor skill; it’s to strengthen your capacity to hold one thought.

By the way, my own swimming received a striking benefit. When I wasn’t observing, I swam behind Dmitry and Sergey, practicing the same skills and testing my own focus. (I [passed that test–a result of tireless practice.)

At the beginning I took 13 strokes for 25 yards. Then my count improved to 12 strokes. And a few times I crossed the pool in 11 strokes. Before we got out I had to test this efficiency on a continuous 50.

First 25, 12 strokes. Flip turn and pushoff. 2nd 25, 12 strokes for a total of 24 strokes for 50 yards.

I hadn’t swum 50 yards in fewer than 25 strokes in several years. I was so pleased I immediately swam another to see if I could repeat it. Voila, I did.

Very happy laps indeed.

All skills and Focal Points mentioned in this post are shown and described in the downloadable Effortless Endurance Freestyle Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit.

The post HOW TO PRACTICE: Terry’s “Mini-Skill” Focal Point Progression from Drills to Whole Stroke Swimming appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 22, 2019

Guest Blog: This T.I. Swimmer Learned to Swim at 49– Now He Directs One of The “World’s Top 100 Open Water Swims”

Mark Fromberg coaching an open water swim clinic at Okanagan Lake, Jun. 2012

Guest blogger and T.I. Swimmer Dr. Mark Fromberg lives in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia and first learned to swim in 2004 at the age of 49, through practicing exercises in the learn-to-swim sequence in Total Immersion’s “Happy Laps” video. Since then, he has swum in many long-distance open water events and raced in triathlons, including some world championship events. Most notably, Mark has become the longest term director of Kelowna’s “Across The Lake Swim,” Canada’s largest open water swim event, and recognized in 2015 as one of the “World’s Top 100 Open Water Swims” by openwaterpedia.com. As a retired physician, he has also provided medical support for dozens of triathlons, including the Kona Ironman World Championships. From October to May, he swims with his local triathlon club twice a week and enjoys trying to keep up with club members half his age. From May to September, he swims in the Okanagan Lake 2-3 times a week, mostly for fitness and relaxation, and often accompanies novice swimmers who need to build their open water swim confidence. He’s recently started to kiteboard and hopes to get good enough to travel to some fantastic kiteboarding meccas—in addition, he also plans to pursue scuba diving certification, something he could never have considered when he was younger!

Mark pausing during a swim at at Gellatly Bay, Okanagan Lake, Sept. 2016

I just read the T.I. blog posted today regarding the common theme of how swimming changes people’s lives, so I thought I would respond to share the story of how swimming changed my life. For me, it was one of Terry Laughlin’s older T.I. DVDs—“Happy Laps”—that changed everything for me. In early September of 2004, I was playing an extended game of squash with a younger and fitter opponent, when I had an awkward twisting injury to my back as I lunged into a corner to try to return a ball. Fatigued and dehydrated by that point, I had to stop due to the acute spasms and my sudden inability to even walk normally, or get into and out of my car. For 3 weeks I couldn’t do anything physical at all—even walking, sitting, and rolling over in bed caused sharp back spasms. After just a week of this, with no ability to exercise, I was going into some kind of exercise withdrawal—I had to do something. So, even though I didn’t swim, I thought I would find some rehab value in just walking chest deep in a pool, since I used to work in a rehab center where this was a common strategy. I discovered I could walk easily in the pool and both floating and doing basic breast strokes were pain-free, as well. So learning to swim became my salvation to recovering from my back injury.

But even before I had started lessons, I found myself asking what it was about me that kept me a non-swimmer all this time. I recalled having a couple of YMCA-sponsored free swimming lessons when I was 7 or 8 years old, in a public, unheated outdoor pool in Vancouver, in a group situation that really didn’t allow for much individual coaching. Needless to say, I didn’t get far, and only remember how afraid I was of being asked to go into the deep end. The one time I was asked to tread water there for just a minute, I was all but exhausted as a result of how frantically I was moving, afraid I would sink to the bottom if I didn’t. Although nothing bad happened, I never learned to relax in the water and, as a skinny kid, I never enjoyed the coldness of the water either. And deep water? Not me! When I decided to learn to swim as an adult, I remember thinking how embarrassed I often felt about my non-ability to swim, and since my own kids were both in early adolescence then, about to start their Bronze Cross training to become pool lifeguards, I wondered how it was possible that they could be such naturals in the water, while I was not. Since I have always prided myself on being able to learn anything I put my mind to, I decided to take on this challenge to learn to swim: for rehab for my back pain, to end my chronic embarrassment, and to not be the “weak link” of the family in the water.

[Click HERE to check out this video Mark used to learn to swim– click HERE to download the free user’s manual]

So before I showed up for the first day of lessons at the local community center, I resolved to find some kind of easy-to-understand study guide for beginners like me. That is how I came across Total Immersion’s learn-to-swim DVD called “Happy Laps”—I actually no longer have it because I lent it out to other beginners a few times too many and lost track of it years ago! However, what I still remember in the video was a sequence with a middle-aged, non-athletic-looking African-American woman who followed a very simple and logical progression over what appeared to be only a single session in the pool, and then she was swimming by the end. Seeing that was very inspiring for me– despite my 49 years of age at the time, and despite my successes in health and fitness in a variety of milieus, I was still completely stumped by swimming. It was a sport that I just had not been able to master, or even feel comfortable with, for no explicable reason I could discern. I thought I was smart enough, fit enough, competent enough, and still young enough to learn something that kids could do, and yet… something was missing.

Mark enjoying a midsummer swim in Okanagan Lake, Jul. 2016

Mark enjoying a midsummer swim in Okanagan Lake, Jul. 2016

When I watched the practice sequence in the “Happy Laps” video over and over again, I recall saying to myself, with each progressive drill, “I can do that”… “I can do that”… “I can do that…” and “I can do that”… all the way to the end of the sequence. When I signed up for some local learn-to-swim lessons at the community center, armed with what I had learned from Terry’s instructional video, I became a swimmer very quickly! I went from maxing out after a gasping, frantic, anxiety-provoking 25 meters to 400 meters of calm stroking just a half hour later. I was a swimmer!! Something I could never have said for the previous 5 decades of my life. I did my first sustained, relaxed swim around my 49th birthday, but in the year following, by joining the local masters swim club, I really learned the finer details of swim strokes to the point that I could do a triathlon just a few months shy of my 50th birthday.

Thinking back to my university years in an undergraduate kinesiology program, there were a couple of occasions where I did ask swimmer-classmates to teach me how to swim. And although they were happy to oblige, they would focus just on the arm strokes, without any discussion of how to integrate breathing—so my frustrations continued back then. I find that adult swimmers who learned to swim as kids do not recall what they learned way back when— for example, forcefully and completely exhaling in the water eventually feels natural as a kid, but it sure doesn’t for an adult swimmer. Thanks to the exercise hiatus that was forced upon me when I strained my back, I finally wanted to get to the bottom of what I was not understanding about swimming, so I decided to read about it, and then watch instructional videos about it, both courtesy of Terry’s T.I. teachings.

I must say that, for me anyway, successfully learning how to swim has first and foremost been a conceptual exercise, much of which can be done as a thought exercise without being anywhere near water. In fact, in recent years, I have conceptually “taught” swimming to people who were interested in learning, even while chatting with them socially—by simply telling them the sequence that appeared in “Happy Laps,” combined with what wound up being a similar process in my community pool lessons. I would ask them, “Do you think you could blow bubbles into water, for 5 minutes, while standing in chest deep water and holding on to the edge of a pool? Where the only rule is, every exhalation has to be in water?” Then I’d ask, “Okay, if you can do that, can you do the same, but not hanging on to the edge of the pool?” “Can you do it while walking in the shallow end of the pool?” “Can you do it while floating on your side/back with flippers on for easy propulsion, with one arm extended, in the shallow end of the pool?” And so on. Most beginners, like I did when I saw the video, would embrace the baby steps of progression, responding “Yes, I can do that.” Prior to even getting in the pool, I had watched the steps on the DVD again and again, and then, while in the pool, the consistent instruction made it easier to believe in it as the right way of doing it—so I progressed very quickly.

Mark savoring the open water near Tulum, Mexico, Jan. 2016

A major epiphany I had when first learning to swim was realizing that my breathing rate and pattern would dictate my arm stroke frequency, and not the other way around—a simple lesson that took 4 decades to understand! Once again, learning to swim was actually conceptual for me, much more so than physical, although I did need to get comfortable with being more forceful in breath exhalation when my face was in the water than when it was in the air. In my experience, once you shore up and believe in a principle that makes sense, it is easy to progress, even rapidly. My first “aha!” moments were:

that breathing control is of paramount importance—these days, I teach that it is the only thing that matters—if you do not have breath control, you can’t swim

that breath control can be quickly lost if you are not fully committed to full and complete, forceful exhalations (lest you build up CO2, which quickly gets you short of breath)

that breath control can be quickly lost with the shock of cold water, so ease into it, and do some easy strokes to get used to the cold and establish your breathing

that swimming is probably the only sport where breathing matters—a lot—and cannot be taken for granted

to manage a sustained (especially open water) swim, you must stay relaxed, so that your breathing stays under control

Learn about breathing in our video “O2 in H2O: A Self-Help Course on Breathing in Swimming”

After learning to swim, I went on to tackle things that I had previously thought would be impossible for me–swimming in distance open water swim events (I have swum across Okanagan Lake in B.C. about 20 times, and I swim along its shores for exercise every summer), and racing in triathlons, including some world championship events. Learning to swim, and feel comfortable swimming in open water has been one of the most liberating experiences I have ever had—swimming was once a challenge that for so long seemed insurmountable, and now it is a part of my life, a great exercise, and a great reminder of what you can attain if you believe you can succeed.

Mark at the finish of Beijing ITU Aquathon World Championships, Sept. 2011

When I swim in the lake now, even when I am with others, I am really swimming by myself—I feel embraced by the water, one with the water. I do not feel it is my enemy, or that it is out to get me; instead, I feel for what it wants to show me, what it is doing that day, whether with waves, swells, or currents. I give myself to it freely, since I have confidence in my abilities now that I never had before. Just like the Japanese concept of “shinrin-yoku,” [which means “forest-bathing” — see link here: http://www.shinrin-yoku.org/] I think swimming in open water has a remarkably meditative quality, allowing you to connect with the primordial soup from which we all evolved. Just like the intangible, calming experience of communing with nature within a forest canopy, regular open water swimming has a profound effect on people that is hard to describe in words. But I am sure every one of the T.I. instructors, and certainly Terry himself, would have been intimately acquainted with this experience.

Since my transcendent experience 15 years ago, I have become deeply involved in nurturing Kelowna’s “Across the Lake Swim,” becoming its longest term director, while growing it from about 250 swimmers, to now over 1200 per year–and becoming Canada’s largest open water swim in the process. Because of the many unique attributes we have incorporated into the event, most especially our obsession with safety, a de-emphasis on racing (we call it an event, not a race), a 6 week training period in open water, unparalleled swag, and an inclusive, supportive environment, we were recognized in 2015 as one of the “World’s Top 100 Open Water Swims” by openwaterpedia.com. In addition, all of our proceeds go toward supporting swimming lessons for kids in our area. Last year, we sent 3000 3rd and 4th grade kids in our region for a series of lessons, as our way of both: 1) drown-proofing a generation of kids in our community– Okanagan Lake, being a tourist town, is the most-drowned-in lake in British Columbia; and 2) exposing everyone here to the gift of swimming from a young age, a sport and experience they can enjoy for life. We consider swimming as a life skill. As a primary care physician, I frequently counseled older people to consider swimming as a great exercise for those with chronic health problems, but I was always dismayed when I would hear the retort similar to, “I could never do that. I am petrified of water.” So we want to change that too.

In fact, in June 2015, the Doctors of British Columbia’s Council on Health Promotion advised us that our Across The Lake Swim Society was selected as the 2015 recipient of the Doctors of British Columbia’s Excellence in Health Promotion Award – Nonprofit category. They stated that, “We felt your program is of great importance to youth growing up in the Central Okanagan, and ensures prevention of needless fatalities in your region. This program also empowers children to live healthier lifestyles and experience the benefits of regular activity that will hopefully continue into their adult life. We consider you a very deserving recipient of the award and would be honoured to present it to you at the Doctors of B.C. Awards ceremony and banquet…”

Mark directing the start line of Kelowna’s “Across The Lake Swim” in 2016

I especially enjoy the teaching aspect of open water swimming to the many adults that, like me, need to get over a mental hump to become a competent swimmer, and they use our event as the “bucket list” item to prove that they can do it. Last year, I even wrote a book on how to become less anxious and more confident when swimming in open water, and stated several times throughout it how learning to swim in open water will change your life [link to book in blogger bio below]. Since I am a recently retired physician, I have also taken a medical interest in swimming, and especially open water swimming. I have provided medical support for dozens of triathlons, including the Kona Ironman World Championships, Ironman Canada for three years, and Kelowna Apple Triathlon Canadian National Championships. In that time, I became aware of the unsettling trend of triathletes dying in the swim portion of their event, well before fatigue or dehydration would normally be expected to occur. I personally reviewed virtually every one of these cases in the hope to gain a better understanding of these deaths, so we could take the necessary steps to reduce risk at our open water event. I eventually wrote about this in another book as well, to reassure aspiring open water swimmers that most risks are preventable [link to book link in blogger bio below].

Here are some further insights I’ve had in more recent years:

1) Recognizing just how many adults have never learned this life skill of swimming because they never understood the breathing aspects that I think are pivotal. I always get excited hearing of someone who has reached the same barrier that I did 15 years ago, since I know how to fix them!

2) Discovering just how liberating learning to swim is—I am more willing to take on learning challenges, I enjoy the water like never before, and I find extended open water swims pure meditation, which is a stress-releaser I never knew existed previous to learning to swim.

3) I have come to realize how important it is for all of our communities to get committed to getting every child to learn how to swim—an inexpensive exercise for a lifetime, a drowning prevention strategy, and a confidence and self-esteem builder. Unfortunately, fears get hardened with age, yet deep down, most people who have had a history of bad swimming experiences or fear really know that they could learn swimming if they really wanted to. The mental game of swimming is the most important aspect of successful learning.

Anyone can learn to swim, whether, young, old, weak, strong, big, small, even paraplegics and amputees. Like most skills, it is easier to learn as a kid, before you develop multiple fears or overthink it. To learn swimming as an adult, you have to accept some seemingly paradoxical messages—like learning to forcefully exhale into water, like prioritizing breath control over stroking your arms, like staying relaxed while doing something physical. And you have to have the courage to face your fears, and revisit them as just a mental barrier to overcome. Do not compare your swim progress to someone else’s—we all learn at our own rate. If you really want to learn to swim, you can, especially if you are doing it in a reliably safe environment.

Given the interest I have developed in promoting open water swimming, it should be pretty obvious that learning to swim, and particularly, learning to swim in open water, has changed my life. I have thrived on my swim event volunteering, open water swim coaching, and have become an impassioned author and website designer as well. I am now starting to write my third book– it will be a race director’s guide to running a successful open water swim event, a treatise to inspire more people to take the plunge. And I have recently organized the first swim-run event in British Columbia (kelownaswimrun.com).

For me, learning to swim was certainly about proving to myself what I could finally do, but now it has really become more about “sharing the wealth” afforded by swimming– the riches of self-discovery, self-efficacy and personal growth, and the joy that fulfills you once you learn how to swim competently. After a long career of helping people mostly return to their normal state of health, I find tremendous satisfaction mentoring people to become something more than they ever were, helping non-swimming adults (like I was) overcome what is often a large hurdle (and vulnerability) in their lives—doing so within the context of our bucket-list signature open water swim event. Despite Terry Laughlin’s many amazing personal swimming accomplishments, I really think Terry’s greatest contribution to the swimming world was his loving embrace of this sport, and one that he shared in earnest every way he could, helping all of us T.I. followers to become swimmers. For me, he deconstructed my most daunting hurdle into simple components, and led me to a promised land I never thought I could reach. And I am certain he and Total Immersion have done this for many thousands of others.

Mark finishing a summer swim in Okanagan Lake, Jul. 2016

Mark finishing a summer swim in Okanagan Lake, Jul. 2016

Guest Blogger and T.I. Swimmer Mark Fromberg is a recently retired physician from the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia who only learned how to swim at age 49, primarily with the help of one of Total Immersion’s dvds: the learn-to-swim “Happy Laps” video. Since then, Mark has been making up for lost time, having completed innumerable open water swim events and almost 50 triathlons, and has become deeply involved in providing race support for a variety of triathlons and swim events, most notably Canada’s largest and longest running open water swim event, Kelowna’s Across The Lake Swim. This event is now on the “World’s Top 100 Open Water Swim” events, due to its commitment to safety, its great swag, its unique pre-event training program, its financial support of swimming lessons of every grade 3 and 4 child in the community, and its remarkable growth in the last decade, now over 1000 participants per year. In 2018, Dr. Fromberg published two books on open water swimming (linked here): one to help get over open water anxiety and develop confidence, and the other to better understand some important physiological principles that can affect open water swimmers. Mark’s wife is also an open water swimmer and former lifeguard, and they have two grown children in their late twenties, one of whom worked as a lifeguard for many years at their local YMCA.

Do YOU have a personal Total Immersion success story that you’d like to share with us? We LOVE hearing about the positive impact– both in and out of the water– that learning to swim with T.I. has had on those of you who have experienced transformation using our approach. If you’d like to send us your success story, please email blog editor Carrie Loveland at carrie@totalimmersion.net — we look forward to reading your stories!

The post Guest Blog: This T.I. Swimmer Learned to Swim at 49– Now He Directs One of The “World’s Top 100 Open Water Swims” appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 15, 2019

PRACTICE TIPS: How to Swim Faster AND Pain-Free with a Relaxed Recovery Arm

This exhaustively-detailed Oct. 2014 post from Terry Laughlin explains how we teach and practice the arm recovery of freestyle and why we teach this way, as opposed to the more traditional “straight-arm recovery,” which requires more strain and exertion. Like Balance, Streamlining, and most TI technique fundamentals, the “Rag Doll Recovery” emerged from a problem-solving process: Terry initially adopted this technique as a stroke modification which allowed him to swim with minimal pain following an injury to his right shoulder (while lifting weights). However, he soon discovered that this modified, relaxed arm recovery actually enabled him to swim faster than before the injury, even with his right biceps tendon detached from his shoulder! Terry was so struck by the advantage he gained through pain-avoidance that these modifications eventually became standard T.I. freestyle techniques: the Rag Doll (or Marionette) Recovery, Mail Slot Entry, and Patient Catch. This article with photo illustrations is an excellent primer for anyone wanting more clarity on the T.I. method of arm recovery, and how there are several critical advantages in the Rag Doll Recovery based on anatomy, physics, and stroke mechanics. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

October 11, 2014

Is there a technique that allows you to swim much faster–while also minimizing the potential for shoulder pain? There is! And it’s one that nearly all coaches and swimmers overlook.

Most people treat the recovery portion of the crawl stroke as incidental. Since it’s not involved in propulsion, they figure, it serves only to get the arm back to where it can resume pushing water back—the part they consider all-important.

But Total Immersion—virtually alone in the swim world—considers the recovery phase consequential. We know that small errors in recovery can create large problems elsewhere–increasing drag and reducing propulsion.

The Rag Doll (aka Marionette) Recovery—the name we initially gave the focal point for suspending a fully relaxed forearm from the elbow during recovery—is one of three essential elements of an efficient recovery. (Swinging the elbow away on exit—not lifting it—and cleanly entering hand before forearm are the others.)

Origins

Like Balance, Streamlining, and most TI technique fundamentals, the Rag Doll Recovery emerged from a problem-solving process.

In Oct 2004, I ruptured the biceps tendon in my right shoulder while lifting weights. It was an almost crippling injury. Normally undemanding actions –like donning a seat belt, or pouring water from a kettle–were too painful to perform with my right arm.

Despite this, I continued swimming. My health insurer required five months of therapy before approving surgery, and I knew that I was likely to regain strength and function more quickly post-surgery if I remained active.

Three Techniques for Pain-Free Swimming

Within a week or two following the injury, I began seeking stroke modifications that would allow me to swim with minimal pain. I discovered that I could minimize discomfort by doing the following:

‘Turning off’ arm muscles as I lifted it from the water–relying on a highly-mobile shoulder blade to bring the arm forward.

Dropping my hand in earlier and steeper on entry.

Letting my arm sink until my shoulder was in a highly stable position, and I felt natural—even effortless–leverage, before applying pressure.

To my great surprise I was soon swimming pain-free. Then, within weeks, I was stunned to find myself swimming slightly faster than before the injury.

Even with my right biceps detached from my shoulder—and despite still being unable to pour tea without searing pain!

I was so struck by the advantage I seemed to have gained through pain-avoidance that these three modifications eventually became standard TI crawl techniques. You know them today as the Rag Doll (or Marionette) Recovery, Mail Slot Entry, and Patient Catch.

Why It Works

Though the Rag Doll Recovery emerged as a workaround to a painful injury, I was intensely curious why this combination of technique adjustments allowed me to swim faster with what would have been a disabling injury for the vast majority of swimmers.

Thinking about anatomy, physics, and stroke mechanics, I recognized several critical advantages in the Rag Doll Recovery:

It provided a rest break for arm muscles that had work to do during propulsion–maintaining a firm hold on the water. Turning off muscles when they’re not needed saves energy and eliminates a common source of muscle fatigue.

Suspending a relaxed forearm from the elbow during recovery—instead of swinging it stiffly through the air eliminates ballistic forces that would destabilize the core or divert momentum sideways. (This evolved into a core TI efficiency principle: Any body part which leaves the water should move in the direction of travel.)

It moves the hand from exit to entry by the shortest possible path. This enables higher strokes rates with no loss of length. I.E. You swim faster efficiently.

How I’ve Used It

In the years since I made the Rag Doll Recovery a core element of technique, I’ve discovered it provides distinct advantages in several challenging situations:

Because my arms never tire, I’ve been able to swim great distances—8+ hours in the Manhattan Island Marathon and nearly 12 hours in the Tampa Bay Marathon—on quite moderate training and with minimal fatigue.

A compact recovery lets me swim in undisturbed comfort and control in the congested conditions of pack swimming in open water

Because my forearm is so relaxed, my core remains stable in rough water. My forearm yields when waves or chop hit it, instead of communicating the impact to my core body.

But even more important, these techniques are so biomechanically sound that it’s been nearly 10 years since I experienced any swimming-related shoulder pain.

Learn the skills of relaxed arm recovery and the other elements of efficient freestyle with the Total Immersion Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course!

The post PRACTICE TIPS: How to Swim Faster AND Pain-Free with a Relaxed Recovery Arm appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 8, 2019

Guest Blog: From The Mainland to A Marathoner– My T.I. Journey from Non-Swimmer to Open Water Long Distance

Naji Ali swimming from Point Bonita to The Bay Bridge (9.3 miles)

Guest blogger and T.I. Swimmer Naji Ali learned to swim as an adult in 2008, when he took his first T.I. workshop. Since that time he now swims year-round in San Francisco Bay and is scheduled to swim the Santa Barbara Channel in 2019, from the mainland to Anacapa Island. If successful, he’ll be the first African-American man to accomplish this. He follows official channel rules in his practice and does not wear a wetsuit– he trains in a regular bathing suit, cap, and goggles. He rises at 4 AM, 5-6 times a week, and is in the water by 4:45 AM. He usually swims in the dark and, at times, swims till sunrise. Water temps in the Bay range as low as 48F in the winter, and as high as 60F in the summer and fall, with the temps usually hovering about 55F. We are delighted to share his inspiring story with you– he truly exemplifies the spirit of mastery, kaizen learning, patient dedication, and enthusiastic practice that are hallmarks of our approach to swimming with Total Immersion. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

I have lived near the water my entire life. I love it. I absolutely love living next to the Pacific Ocean, watching the waves crash upon the shore, seeing surfers ply their trade. I can sit around and gaze out over the water for hours and never get bored.

To me, the water is magic. About as close to paradise as one can get.

As luck would have it– or more appropriately, upon the demands of my mom– at 13 years old, I got a summer job working for a marine biologist at Scripps Institute of Oceanography, located in La Jolla, CA. Every day I’d hop on a bus and ride an hour down to my job. My boss, a very kind man, taught me about sea turtles, seals, sea lions, and jellyfish, better than any school teacher ever could. In fact, I can still dissect a frog and list all its organs in detail to this day.

About two months into my time with him, he invited me to go on a boat that was going out to fish for albacore tuna. He and several other biologists wanted to be the first scientists to bring one back in captivity. We went out about 20 miles from shore to fish. I remember that day being very calm, with gentle “rollers” rocking the boat like a mother would a sleeping child. I also remember that it was very hot, so hot that one of the crew members decided to go for a quick dip. He stripped down to his trunks and dove in. I ran over to the railing and watched as he swam breaststroke, backstroke, and freestyle. “Wow,” I thought to myself, “I wish I could do that.” Afterward, he climbed back onboard and toweled off. I approached him and asked: “That was pretty cool… could you teach me how to swim like that?” He looked on and said: “Kid, Black people don’t swim.” The whole boat erupted into laughter. Even I was laughing… but not really.

I was embarrassed. Embarrassed because I was the butt of the joke, and more importantly, that I didn’t know how to swim.

I told no one about that day and didn’t think about it for another 27 years. Fast-forward to 2008, and I’m sitting watching the Beijing Olympics, and witnessing history as Michael Phelps won 8 gold medals. Although this was a truly amazing feat, the most exciting thing for me was watching the Men’s 4 x100m relay final [click link to view race]. No, not because Jason Lezak, the anchor of the relay, came from behind to win the gold for the Americans and defeated the French; nor was it that they set a new world record. I was excited because a young Black man named Cullen Jones was a part of that record setting team. At that moment, I determined that I was going to learn to swim. The memory of everyone laughing at me on that boat– and my embarrassment– needed to end. I had to learn to swim. The question was: How do I get that done?

I looked online and found a man not far from me that taught swim lessons. He showed me how to float with my face down in the water, float on my back in a comfortable position, and the rudimentary skills of pulling, kicking, etc. He was a nice enough person and certainly knew how to swim himself, but it didn’t feel right for me. So, I went to a second person who specialized in working with adults who didn’t know how to swim. She too was kind, but didn’t offer much more than the previous person. But one thing she did do, and I’m forever grateful that she did, was mention a system of learning how to swim called “Total Immersion” (TI).

“What the heck is that?” I asked, confused.

She told me to look it up online and see for myself. So, I started researching TI and noticed that they had a book that a man I had never heard of– Terry Laughlin– had written. I went to the library and checked out a copy. The minute that I started reading, I knew this was what I needed. But just reading the book wasn’t going to help me– I’m a visual person and I have to see someone doing something, or get in-person teaching to catch on. That’s when I discovered that there was going to be a TI workshop held in San Francisco not far from where I lived!

Naji Ali doing a training swim in Aquatic Park in San Francisco

To say I was initially confused and intimidated at my first TI workshop would be an understatement.

I was with about 20 people, all of whom– with the exception of me– had either average swimming skills, were triathletes, or were former competitive swimmers. At this workshop, I was coached by Coach Fiona Laughlin and Coach Dave Cameron. They showed me all the drills: Superman glide, right skate, left skate, torpedo drills into right skate and left… Well, you get the idea! I did my best to try to keep up, but the more they did my video analysis, the more I cringed. “What the heck have I done?” I said to myself. “I can’t swim. I’m never gonna learn to swim. The guy on the boat years ago was right.”

I should say that throughout this workshop, Coach Dave and Coach Fiona never had the negative attitude that I had about my learning process. They saw the positive that I couldn’t see. They focused on continuous improvement.

After the workshop was over, and I was left all alone to try and sort things out, I began going to the pool to do the drills. At first they were beyond frustrating; I rolled too far to stacked shoulders in skating, I wasn’t moving forward during Superman flutter, my head position was incorrect… Arrggghhh!