Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 6

January 11, 2019

FREE STUFF: Sneaky Speed e-book, Tempo Trainer basics, and more T.I. bonus material

(A free 40 page sample from the Ultra-Efficient Freestyle e-book)

Just a heads-up for our readers, in case any of you were unaware that the website has a number of complimentary products– a reader recently pointed out that he searched and searched for the “Sneaky Speed” e-book that he saw in one of our advertisements, but he couldn’t find it for sale on the website. The good news is, it’s not for sale– it’s actually FREE! You can download that guide, as well as a load of other T.I. freebies, by heading to this LINK. There is, in fact, a tab labeled “FREE STUFF” on the site, but since it’s not in flashing lights and neon font, you may have overlooked it while browsing the products. Below is a brief overview of some our popular free downloads– there are more free products than can be listed here succinctly, so check out the full library of swag when you head over there.

For future reference, you can find our free products by:

1) First clicking on the “STORE” tab on the main page of the website

2) Once you’ve navigated to the store page, click on the “FREE STUFF” tab (the last tab on the far right, next to the “GEAR AND TOOLS” tab)

We’re delighted to offer free supplemental info to T.I. enthusiasts, as well as those of you new to our method and looking to sample what we teach. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

POPULAR FREE DOWNLOADS YOU CAN CHECK OUT HERE:

Product Description:

More Effort or Smarter Choices?

You can’t get around it; the idea of swimming faster is undeniably sexy.

And triathletes– most of them new to swimming– are constantly confronted by blogs, articles, and exhortations expressing urgency about swimming faster. For many people, the primary effect is to increase existing insecurity about swimming and how to train for it.

While you probably have little familiarity with swimming for speed or time, those urging you to swim faster seem to be in the know. And, often, your efforts to follow their advice don’t seem very encouraging.

You try to swim faster, but it seems awfully hard work just to gain a few ticks on the clock. You wonder if you simply lack swimming talent or as one triathlete wrote me– if you’ve hit a personal speed limit. Will this limit your potential in triathlon?

In fact, what you’re experiencing is perfectly normal– practically universal, actually. Humans are terrestrial mammals. Swimming is an aquatic skill. Our land-adapted bodies (heavier than water, many moving parts) and innate discomfort in water mean we become energy-wasting machines when we enter the water– a tendency only made worse when someone urges, “Work harder; swim faster!”

In this book, we’ll show that the too-narrow question of swimming faster or slower obscures a more fundamental question: whether your swimming should focus on greater effort or smarter choices.

Product Description:

What is the Green Zone?

The most efficient range of stroke counts for a swimmer of any height. These are derived from data on the Stroke Length of elite freestylers, and modified to give “average” swimmers a realistic-but-challenging efficiency target. When you keep your count in this range, you make every stroke count. (We’ve made this chart available in both meters and yards.)

Product Description:

This complimentary e-book has been made freely available to allow you to sample the content and format of the full Effortless Endurance Freestyle book. This excerpted version includes 40 pages of the 130-page full version. Included are these 7 sections:

· Introduction: There is a better way! Describes the core elements of the ultra-efficient technique for freestyle; how and why it evolved; and for whom it’s intended.

· History of Freestyle A succinct history of 6000 years of evolution in swimming techniques, with a focus on the 150-year evolution of ‘front crawl’ or freestyle, and why TI’s ultra-efficient technique is the first significant “evolutionary leap” in almost 100 years!

· About Total Immersion How and why TI differs from traditional approaches; the three requirements that must be satisfied for any technique to become part of our method; and the four fundamental changes we seek to effect in every TI student (How to Think is #1.)

· Swim 25% Faster at 90-plus? Dr. Paul Lurie took his first TI lesson at age 94, and is still improving in form—and speed—at 97! (Paul, now 98, swims 20 lengths every morning.)

· Why Haven’t You Swum Better? We all experience some degree of frustration or outright failure with traditional teaching or training, yet tend to blame ourselves when we fail. Learn why there’s nothing wrong with you that can’t be fixed by a change in approach. Features Tim Ferriss.

· The ‘Universal Human Swimming Problem’ (UHSP) Describes 6 inherent causes of energy waste that are innate to being “a terrestrial mammal in an aquatic environment” and how each undermines your efforts; the shockingly low rate (3%) at which the average human swimmer converts energy into forward motion; and why traditional approaches fail to solve them.

· How to Swim Efficiently Learn the counter-intuitive solutions to the UHSP; the foolproof 3-step Pyramid of Skills leading to ultra-efficiency; and the two little-known keys to success that allow you to bypass “error points” and build confidence while learning.

AND MORE FREE PRODUCTS… Click HERE to view full bonus library!

The post FREE STUFF: Sneaky Speed e-book, Tempo Trainer basics, and more T.I. bonus material appeared first on Total Immersion.

January 4, 2019

VIDEO: Terry teaching Advanced Propulsion Skills for Racing– 2013 Kona Open Water Camp

(Terry, in Mar. 2013, pausing at the 1.2 mile buoy– the turnaround– on the Kona Ironman course)

This week’s featured video–courtesy of T.I. Master Coach Dave Cameron’s YouTube Channel– shows Terry at the 2013 T.I. Kona Open Water Camp, teaching an advanced group of swimmers (including Ironman competitors) about higher-level propulsion and positioning techniques, particularly for racing. The skills taught in this 16 min. video are subtle, detailing the finer points of propulsion that swimmers begin to practice after they have mastered all the foundational skills that T.I. teaches (Breathing, Balance, Streamlining, Propulsion with weight shifts of the core body). Terry comprehensively describes how to practice and “wire in” the most advantageous arm position, by applying strategic pressure with the hand and forearm, for faster swimming. Many thanks to Coach Dave for taping one of the teaching sessions in Kona, back in 2013! For the many T.I. swimmers who always wished to experience a coaching session with Terry but missed the opportunity, this is a valuable up-close look at how he taught advanced skills. A bit more loose and improvisational than our scripted instructional videos– with dryland rehearsal demos of stroke technique, some interesting observations from Terry about how world-class swimmers create effective propulsion, and the difference in form that he noticed from the first finishers of the Ironman swim in Kona, versus the finishers at back of the pack in the swim. BONUS: we’ve attached a transcript below the video, so you can read along as you watch/listen! If this fires you up to take your own T.I. Swimming to open water, you can click HERE for info on our upcoming 2019 T.I. Open Water Experience in Kailua-Kona on March 14-18 . Enjoy this virtual session with Terry… and Happy Laps!

[Editorial Note: This was a non-professional recording, spontaneously taped at the beach by Kailua Pier, with some ambient noise of other beachgoers in that informal environment. We highly recommend, at the 10:25-12:40 time signature, that you check out the transcript we’ve provided, due to the distraction of a paddle-boarding dog– yep, it’s Hawaii!– barking very loudly in the background. Real world conditions during this filming! The transcript is an excellent supplement to refer to at that point in the video.]

(TRANSCRIPT)

Terry:

With propulsion, you’re really working on higher-level skills—you’re also working on the things that have a higher inherent cost in power and energy, and those are really limited and relatively non-renewable resources. So, how we apply them, when we apply them really, really makes a difference… The reason we don’t do too much of this [motions with hand to show the lead arm catch position] too early is that, first of all, you must have your balance, your stability, really wired in strongly in order to actually do these things effectively. If you don’t have those [fundamentals], it’s really hard to do those things [advanced propulsion skills]. So what are we talking about here? Alright, so we’re talking about, when we apply pressure, that we move ourselves forward—don’t move the water around. Alright? And that pressure may be from the hand and forearm—it may be from the leg. The legs’ pressure does not move us forward, it helps with the power generation, by assisting with the weight shift, and the propulsion is actually produced from how you apply pressure to water with your arm. So, as you do that, one of the things you want to have spent countless hours thinking about—before the race, before you’re under pressure—is the fact that what you’re pressing on is water. And that water is a bunch of disaggregated molecules. It’s really easy to start those molecules moving so that the molecules get stirred up, but you don’t really move very far… We need stroke length and we need rate. And to some degree, another trading chip we have is how much pressure we choose to apply [Terry motions with position of lead arm].

In a race, I’m constantly trying to find the right marriage—the right blend—of rate and pressure, for that stage in the race, knowing what’s coming forward. And I rely on having done that countless times, in repetitions swimming in the pool, as well as in open water practice, so that literally, I don’t really have to think very much about it. I have these auto-responses that are programmed into my brain, so that when I race, they come out. This is so—the opportunity to use this sort of thinking, this sort of strategic awareness, and finesse in how you apply those resources—is so much greater in open water, than it is in the pool. In the pool, it [competitive racing] really does come down to—a lot—to fitness, athleticism, inherent power you have, and things like that. I’m not very competitive with the best people in the pool—I’m very competitive with the best people in open water, and I can out-swim people that are far faster than me in the pool because… I love swimming in open water because it really appeals to me that, as Margie [a swimmer attending the Kona camp] said, ‘You can punch above your weight in open water’… which is really hard to do in the pool. So, what we’re going to do today, with the caveat that you need to still be working on your balance and stability over time, so that these things we do today work better and better and better… And especially work when you’ve raised your rate, when you’ve started applying more pressure, when there’s a lot of people around you and you’re feeling under pressure, ok? So that’s got—keep working on that [balance and stability], you never, never stop.

So… alright, so the first part of how you create propulsion with your arm starts with, your arm has to be in the right position… The other two groups [at swim camp]—and I haven’t swum with you [the advanced group] yet, so I haven’t had the chance to observe you underwater—but in the other two groups [beginner and intermediate groups], virtually no one has their arm in the optimal position. I haven’t mentioned it to them because they’re dealing with other stuff [balance, stability, streamlining skills]. At some point, it will be appropriate to bring that in, but they’re dealing with other stuff… Having watched you swim surface [during surface videotaping] the other day, looks like, for the most part, you’re ready to do this, cause your form looks… You look stable! You look stable on the surface, you look smooth on the surface. So what I’ll be looking at as we swim is the extent to which you have an arm position that looks like this [demonstrates applying pressure with the lead arm catch]. So just visualize a balance ball and drape your arm over it… [Group rehearses arm position together] Alright, as we start this exercise, we’re going to be focused mostly on creating a sense of shape and volume under the arm… The shape we want is one where it’s really easy to get the hand position to apply pressure so the resultant force is that way [motions forward]. Alright? Any force you apply in any other direction is wasted, and we can’t afford to waste. So, the first thing is to have the hand position so that when you apply any pressure, the resultant force is going to move you forward.

Unless you are Oussama Mellouli [Tunisian Olympic triple medalist] or Grant Hackett [Australian Olympic multiple medalist], or any of these guys– and women– who are world-class, and have an ability to almost dislocate the shoulder blade…that, what they call ‘the early vertical forearm’ and they promise you that paddles will teach you, and so on—that is pure nonsense. Alright? What you require is a shoulder blade that practically is able to dislocate—that’s one of those ‘talents’ that allows a person to be a world-class freestyler and get the arm in and do that [motions with lead arm in vertical position]… Ok? Cause if you watch video of someone like Oussama bin… bin… [Laughter]… Mellouli! From the side, underwater, you see his shoulder blade popping out, alright? And practically bursting through the skin—mine doesn’t do that. It doesn’t matter if every single brain cell I have is thinking about doing that…it’s just never going to happen. Alright…so, I make sure that I’ve got the hand facing back and I do that by relaxing [demos relaxing the lead wrist], not by turning on [muscles]. And then, I have to use muscles– the posterior deltoid primarily—to lift the scapula and open the axilla [underarm]. Those are the two actions, and they’re pretty subtle actions. Alright?… And the limiting factor on how much pressure I can apply is not the power I have here, it’s the ability of these much smaller, and less powerful muscles to hold that position. Because if I maximize the power in the prime movers, these secondary movers are just going to give up, and I end up with something that is sort of sliding the hand back, as opposed to holding that position. And by the way, you do have [points to swimmer in group]—I did see you enough yesterday—to see that you do have an inherent ability to do that, that’s better than most people’s. So that’s good… [Swimmer replies: It’s Pilates…”] Pardon? [Swimmer says again: “It’s Pilates, I think…”] I think you’re born with it! [Laughter] I’ve done Pilates and I’ve done yoga, and I’ve done all kinds of things, and it doesn’t happen…

So, in any case, you visualize… We’re going to start out, we’re going to go through a series of focal points… We’ll do a couple of rehearsals on a series of focal points, alright? You’re not going to learn this [master it] in the next 90 minutes—what you’re going to learn is the process that you can continue to make this better. So the starting point is to visualize a balance ball, and drape your arm over it [demos lead arm position], and I use that word ‘drape’ very consciously to connote that it’s relaxed… [Swimmer asks: “Where is the bowl?”] Hmm? The ball is between… [Swimmer: “Oh, ball!”…] A balance ball—a Swiss ball. A Swiss ball. [Swimmer: “Ohhh…”] So you visualize… and as you do that, think about… How large is that ball? Is it 55 centimeters? 65 centimeters?… And the space between my [lead] palm and my hip is what I’m conscious of, I’m thinking about the size of the ball that I’ve got there. Ok? And then once [I], having draped and defined the space, defined the volume, as best I can, alright?… Now what I’m going to do is just—in my mind—just hold the ball, so that there’s light activation of the arm muscles, so I feel I’m lightly holding it against my hip. Ok? That’s the feeling that you want to have as you begin applying pressure… As I drop in, as I drop into the water [with the recovery arm] through the ‘mail slot’ [angle of hand entry]… This is why we teach the ‘mail slot’ early—because it sets you up to do that [achieve optimal lead arm position for propulsion]…

I’ll mention one more thing I’ve observed about triathlon: I’ve watched the end of the [Kona] Ironman from up here, on the pier, as people are coming in, after swimming their 2.4 miles… I’ve watched other races from the shore, and seen people moving through the latter stages of the race, and you can really observe things about what predominates in the early part of the pack, in the mid part of the pack, in the rear. And when I look at the first 10-20% of the field, I see a large percentage of people going in [demos hand entry] so that the hand precedes the forearm, precedes the elbow. And then as you go further back in the field, you see more of that on entry [demos collapsed forearm]… the flat entry, elbow hitting. The further back you go [the last swimmers finishing], the more it’s the elbow hitting first…alright? So, that ‘mail slot’ entry is really characteristic of success in triathlon swimming, and other swimming, as well.

So, we’re setting ourselves up for that position with the mail slot, so we keep in mind that’s really critical, at some point in the race, to be checking in whether you’re going through the mail slot [as the hand enters the water], even listening, because that entry is quieter than this thing [flat entry]. So, one of the things you do while racing is be checking in on how much noise you’re making, especially when you’re in a pack, especially when you’re starting to pick it up [pace]. Am I staying quiet? Am I still going through the slot? Or am I—in my excitement and rate—am I starting to do this? [demos windmilling the arms with flat entry] Ok?

So—now hold the ball. Just visualize holding the ball… Alright, now lift the ball out of the water—lift the ball a few inches. Just visualize that you’re holding the ball—you’re still holding it—lift it a few inches, and then rotate your shoulder while still holding the ball, and drop the ball behind your hip. Rotate your shoulder and drop the ball behind your hip. Now, I’m going to do this several times—I’m going to lift the ball from behind my hip, I’m holding it back here… I’m going to leave my [lead] hand here, fingers at the bumper [as if reaching down the bumper of a VW Beetle’s curved hood], ok? I’m going to lift the ball, carry it forward and put it here [demos lead arm position], against this part of my hip. Lift it—return it, drop it. Ok, this is a visualization we’re going to start with.. We’re going to re-think our recovery from 3 thoughts: elbow circles, paint the line, ear hop, mail slot [TI recovery and entry focal points]—4 thoughts. From 3 or 4 thoughts– we’re going to consolidate into 1 thought, which is: what’s my optimal position to start the stroke? And can I come out of the water already in that position, carry an arm forward without any change in shape, and drop it. Alright?

So we’re simplifying the [stroke] thought into 1—one awareness… If I watch you swimming, and you go that way with 3 thoughts, little bit with one, and the second, and the third…and then you get over there. And then you come back with the 1 [stroke] thought—I should not see anything different. You should experience something that you distinguish as different, once you’ve changed from the 3 thoughts to 1. [DOG BARKING CONTINUOUSLY—refer to transcript] And this process of being a little bit more demanding of your brain in how to conceptualize what you’re doing, is one of the things that wires it [proper technique] in, so that when you’re under pressure, when you increase rate, and so on—it doesn’t break down. Ok? So you have to create a more robust circuit, so these things don’t break down under difficulty, alright? So once we introduce racing, pressure, by that I mean this pressure [motions to pressure on lead arm], as well as that pressure [pressure of competing], and rate… we need this thing [our form] to be unbreakable. And one of the tools you use in practice is more thoughts to wire it in. Ok?

So… so, we’re going to start with some visualization and rehearsal—the rehearsal means standing on one side, with that hand on the bumper, hold the ball against your hip, lift it a bit, carry it backward, drop it in. Lift it, carry it forward, drop it in. Alright? So we’ll do that, a bit with the right arm, and then swim over, just checking whether we feel the same sensation as we go across, alright? Then we’ll do the same thing with the left, and swim back, checking whether we’re doing the same thing. Ok? That will be the first step. The second step will be, having dropped it [the lead arm] in, we will visually verify the position. Alright? We won’t do this first because all our focus is on something that’s happening over here [motions with the recovery arm]. Then after we’ve had a little bit of time to familiarize ourselves with that thought—and the sensations that accompany it—then what you’re going to do is visually verify that the position that you have entered into is the one you want—the water-holding position. I call this ‘the arm full of water position’ cause it’s the optimal position for trapping water behind hand and forearm. Alright?… Step two will be to visually verify and see that it’s still [the lead arm] for at least a nanosecond after you drop it in.

And this idea of it being still is a hyper-critical one. The men’s 4 x 100 relay in Beijing– where Jason Lezak went by Alain Bernard from France, incredibly… They had, for a while, on NBC Olympics(dot)com, they had underwater video of that race. And in studying it, if you have the opportunity, this is what you would see: Lezak, despite swimming—I don’t know what the rate was, but it was exceptionally fast rate swimming, alright… His hand dropped in and there was a nanosecond where it was still, after he dropped in, before he began pulling. And Bernard, in contrast, slammed his hand in, and it just kept going back. Bernard took 46 strokes on the second lap when the wheels came off—Lezak, 34. 12 fewer strokes, and he [Lezak] went by him in the last 25 like he [Bernard] was standing still… because Bernard was moving water. Lezak was moving his body, and it’s that position [with lead arm] and that moment that makes all the difference. Ok? So that will be our second thing—that we’ll visually verify that we’re in that position and that it’s still for a moment. We’ll take some time on that. And then finally, how we begin applying pressure [on the lead arm] after that, is we’re going to visualize this disaggregated ball of molecules, not just water, alright? What it really is, is a ball of molecules, and as you press on it you’re going to do it with sufficient patience and care, that in your mind, you’re keeping those molecules together to move your body forward. Alright? When you do that, you should notice something that may have escaped your attention before—that water has density, that it has thickness. And if you apply that pressure in the right way, you can feel it return that pressure… You want to feel that pressure, so that it converts into forward movement…Ok? I can’t tell you how many dozens, if not hundreds, of hours I’ve spent visualizing like that—and it makes huge, huge difference. I can go 0.95, 0.90 rate [stroke rate with the Tempo Trainer] and not feel any turbulence as I start the stroke. Makes all the difference…

CLICK BELOW TO LEARN MORE:

TAKE YOUR T.I. SWIMMING TO OPEN WATER– JOIN US IN KAILUA-KONA, MARCH 14-18, 2019!

The post VIDEO: Terry teaching Advanced Propulsion Skills for Racing– 2013 Kona Open Water Camp appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 21, 2018

DEMO: Master the 2-Beat Kick– Connect Your Legs to the Power of Core Rotation for Maximal Speed & Efficiency

(Terry mid-stroke, poised to flick the toes of the bottom leg to drive his top hip down and entering hand forward, and propel him into a streamlined position on the other side)

This week we shift our focus to a more advanced skill in the T.I. swimming sequence: the 2-beat kick. As most readers of this blog will know, the first fundamental skills that we prioritize are balance and active streamlining, which reduce drag and optimize body position in the water. Once a balanced and streamlined body position is mastered, we then turn our attention to creating propulsion, through weight shifts of the core-body and a fully-connected stroke, powered by “the kinetic chain.” To understand how the kinetic chain functions in baseball, for example, here’s a brief description from an article on overhand pitching in the academic journal, “Sports Health”:

“The overhand pitching motion consists of a sequence of body movements that start when the pitcher lifts the lead foot, progresses to a linked motion in the hips and trunk, and culminates with a ballistic motion of the upper extremity to propel the ball toward home plate. The effective synchronous use of selective muscle groups maximizes the efficiency of the kinetic chain. The lower extremity and trunk generate and transfer energy to the upper extremity. Coordinated lower extremity muscles (quadriceps, hamstrings, hip internal and external rotators) provide a stable base for the trunk (core musculature) to rotate and flex…”

(Frame-by-frame, pitching windup and release in baseball, illustrating the kinetic chain)

Similarly, in swimming, the propulsion of the stroke is generated via the kinetic chain– transferring energy by connecting the arms and legs to the power of whole-body rotation and extension. Watching a pitcher, we may see the baseball released rapidly by the player’s arm– but that singular body part is clearly not the entire source of the power and speed. It’s generated in the integrated full-body windup, of course. Likewise– in swimming– using the diagonal power of an effective 2-beat kick to connect our legs to the hip drive and core-body rotation, as one spears an arm forward, is rather analogous to a pitcher’s windup and release. Or a golfer’s swing. Or that of a tennis player! Obviously, the kinetic chain is evidenced in all sports– the point is, our true power lies in fully-connected, whole body movements. Once balance and streamlining skills can be performed easily, mastering a 2-beat kick is an excellent way to develop a more integrated stroke that maximizes your speed and efficiency.

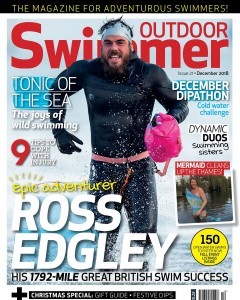

For a complete, illustrated breakdown of the 2-beat kick, check out Terry’s article below, previously published in “Outdoor Swimmer” magazine. And if a picture’s worth a thousand words, a video’s worth even more– take a look at the instructive, brief YouTube video demo and analysis of the 2-beat kick by TI Coach Mandy McDougal. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

Outdoor Swimmer, 2/18/16: “Master the Two-Beat Kick” — Terry Laughlin

What’s the best front crawl kick pattern to use in open water – whether for pleasure or speed? Most swimmers have little familiarity with their kick or understanding of its role in propulsion. I was no exception. For 40 years, my legs fatigued each time I raced while adding precious little speed. I believed I needed to kick harder to swim faster, but doing so only disrupted my stroke rhythm while exhausting me. Decades of kicking sets did nothing to improve the functionality of my kick, nor minimize that ‘dead legs’ sensation.

There are two distinct kick rhythms in freestyle: the six-beat kick (6BK), with six leg beats per arm cycle (i.e. two strokes) and the two-beat kick (2BK), with just two beats per arm cycle. In both styles, only two beats contribute to propulsion through body rotation. In 6BK, the other four beats are preoccupied with body position and alignment.

The 6BK is unquestionably best for maximizing speed over distances of 100 metres or less. From 200 to 400 metres, either can be effective, depending on swimmer preference. As racing distance increases beyond 400 metres, the 2BK offers ever greater advantages in speed-for-effort.

The fastest distance swimmer ever, Sun Yang, uses both kicks to great effect. When he broke the 1500m world record in the 2012 Olympics, he used a 2BK for 90 per cent of the race before shifting up to a powerful 6BK in the final 150 metres. He used the 6BK exclusively in the 200m final, where he finished third. Given that, I believe a 2BK is the most efficient for virtually all distances and fitness levels in open water swimming.

To read the entire article, with accompanying illustrations, and step-by-step breakdown, click HERE.

T.I. Coach Mandy McDougal Demonstrating the 2-Beat Kick (2:50)

Slow-mo & frame-by-frame analysis, illustrating how the 2-beat kick integrates with the whole stroke

LEARN MORE: Purchase the Total Immersion Freestyle Mastery Lesson Two: Expert 2-Beat Kick video as a digital download!

The post DEMO: Master the 2-Beat Kick– Connect Your Legs to the Power of Core Rotation for Maximal Speed & Efficiency appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 14, 2018

Going with the Flow: Audacious Goals & Seeking Opportunity in Adversity

Terry leaps off a cliff in Eleuthera, the Bahamas, December 2006 (photo: Dennis O’Clair)

Terry leaps off a cliff in Eleuthera, the Bahamas, December 2006 (photo: Dennis O’Clair)

Continuing with the theme of goal-setting, which we explored in last week’s post– “Strategies for Achieving Your Breakthrough Season: Success is Not the Result of Luck!”– this week, we revisit Terry’s December 2015 blog on the pursuit of accomplishing “audacious” swimming goals and the vital importance of consciously mastering one’s mindset in such endeavors. In this article, Terry discussed how visionary goals which imbued him with a deep sense of purpose enabled him to accomplish all of the following within a year:

Complete a second Manhattan Island Marathon Swim

Win his first National Open Water Championship

Break a National Masters Record in open water

Win a World Masters Championship Medal in the 3K Open Water event

And more importantly, he shared his approach in order to demonstrate that these strategies for success can work for any of us, if we choose to cultivate these habits of excellence: learned optimism, seeking “flow” states,” following a path of mastery, choosing an approach of “deliberate practice,” setting meaningful goals, and finding worthy challenges even in adverse circumstances. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

12/21/15

Ten years ago, several months before my 55th birthday, I set a group of BHAGs or Big Hairy Audacious Goals. The term comes from the book Built to Last by Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, who studied businesses that had maintained influence and excellence over many decades. BHAGs focus on enduring and meaningful impact: Henry Ford set out to democratize the automobile; in the early days of Apple, Steve Jobs talked of putting a computer in every home–40 years later there’s a computer in everyone’s pocket!

BHAGs embody visionary thinking. In 1960, JFK proposed to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. This achievement, fulfilled in 1969, remains a defining and uplifting moment in American history–and, well, “a giant step for all mankind,” as Neil Armstrong put it.

“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Like the moon mission, BHAGs usually take a decade, or decades, to achieve. But I aimed to fulfill mine within a year. They included:

Complete a second Manhattan Island Marathon Swim.

Win my first National Open Water Championship.

Break a National Masters Record in open water. (I’d never even set a team record in high school or college.)

Win a World Masters Championship Medal in the 3K Open Water event.

Happily, I did achieve all of those and more–winning four national championships, at distances from 1 mile to 10K, and breaking two national records for the 55-59 age group, the 1- and 2-Mile Cable Swims.

My greatest benefit was gaining a sense of having a mission to accomplish, which lasted for nearly a year from the time I conceived of them. Not a single practice during that time ever felt like a check-off in my daily routine. They all felt important–even urgent. The imprint of a ‘year of high purpose’ endured well beyond that period and has had far-reaching impacts.

While I couldn’t have achieved my goals without a highly-efficient stroke, even more critical than how I swam was how I thought. For a decade previously, I’d become increasingly interested in Positive Psychology–the study of thought processes displayed by high-performing individuals.

I learned about the traits, behaviors and mindsets of such people in books such as Learned Optimism by Dan Seligman, Mastery by George Leonard, Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi PhD, and the principles of Deliberate Practice by Anders Ericsson PhD. Setting such galvanizing goals provided an ideal opportunity to test these principles.

By applying these lessons I achieved far beyond what I’d always thought was possible. As a result of that experience, Total Immersion has emphasized effective thinking as much as effective movement.

Goal-setting with the Flow

As I approached my 60th birthday in 2011, I faced physical challenges that limited what I could accomplish athletically. In my late 50s, I began to experience fatigue and chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with the autoimmune syndrome, Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR). I also began to suffer foot and calf cramps after barely an hour of swimming–an effect of arthritic narrowing in my lower spine.

Between them, my training was significantly limited compared to previously. If I swam a bit too long or hard, I could be left feeling drained for hours after. And my feet and calves often began cramping after little more than 2000 yards.

Yet though my training was likely to be quite limited, I still craved the sense of purpose and urgency I’d experienced five years earlier. Going with the flow means seeking opportunity in adversity. So I decided to Goal-set with the Flow.

My mid-50s accomplishments had been in my lifelong strong suit, distance freestyle. At 60 I decided to strike out in a new direction, emphasizing events outside my comfort zone–shorter distances and the other strokes. I’d swum only freestyle for most of my life and had only begun to focus on other strokes a few years earlier.

As well, the limitations on how long or intensively I could train resulted in two surprising developments:

Knowing that I had a practice ‘budget’ of 2500 yards made every lap seem far more precious. I would allot time only for activities proven to improve performance.

Needing to be careful about intensity, pushed me to rely less than ever on power and muscle, and find the easiest way to accomplish any task.

The results were thrilling and have transformed my approach to practice and training. In 2011, at Masters Nationals I entered every discipline but backstroke–and medaled in all four! In 200 Butterfly, I even did a lifetime best, swimming faster than I had at 55 when I was in the midst of achieving BHAGs in distance freestyle.

Briefer, More Focused, Better Than Ever

Finding opportunity in adversity has led me to embrace practices that emphasize focus over duration. I seldom swim beyond an hour; many of my practices last just 40 to 50 minutes. What I love most is how keen my focus remains for that duration–quite literally from first stroke to last at times.

I include only two to three sets or activities in most practices. In each I’m either trying to perform a subtle skill better than I ever have in my life. Or ‘solving problems’ related to controlling stroke count, while swimming faster–on the clock, or on my Tempo Trainer. I can succeed at most tasks only by giving it my full attention. Moments of Flow have become more routine than ever before.

Practicing this way has produced surprising–even thrilling–breakthroughs in awareness or control each year. My pull, kick, and breathing are all strikingly more efficient than they were before I turned 60–a development confirmed by comparing recent video with video shot in my 50s.

And it my stroke doesn’t just look better. It feels amazing almost every day–better than it ever has. Twice in one recent week I posted this on the TI Facebook page: “I felt fantastic in the water today–I’ve never felt this good before.” Not an insignificant claim after 50 years of swimming.

I’ve never looked forward to swimming as much as I do now, nor have I felt a greater sense purpose and flow. I still have PMR symptoms; I often feel achy and mildly flu-like as I get in the water. But within minutes I feel indescribably great. Swimming has always been known for its unique healing properties. I seem to have tapped into something beyond.

In three months I’ll enter the 65-69 age group. As I did at 55 and 60, I plan to attend Masters Nationals in the spring to get a concrete gauge on my performance capabilities. In early November I wrote out my goals for the next six months. As I was writing them, I felt the familiar sense of purpose and urgency, and I’m more grateful than ever for how central swimming goals have become for my life.

Learn the skills of Efficient Freestyle with the Total Immersion Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course!

The post Going with the Flow: Audacious Goals & Seeking Opportunity in Adversity appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 7, 2018

Strategies for Achieving Your Breakthrough Season: Success is Not the Result of Luck!

“Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.”

– Anonymous

The above quote was one of Terry’s favorite epigrams in his latter years. Its message so resonated with his personal ethos that he even included it in the signature of his email for a period of time, prior to swapping it out for his own message: “May your laps be as happy as mine.” Together, both quotes reflect two primary themes that drove Terry and his mission with Total Immersion, and form the continuing legacy today:

1) Success is cultivated consciously, through deliberate, daily choices about where to focus one’s attention and energy.

2) Enjoying the practice of swimming as a life-long path of mastery and flow is as valuable as achieving any end goal.

That said, these two philosophies linked together synergistically, motivating Terry to pursue “peak performance” and “flow states” as a daily habit in his swimming life. Whether setting an intention that each practice session be “the best swim of my life,” reading voraciously on any relevant new research, or tirelessly seeking to simplify and refine the most elegant and efficient method of teaching swimming, this underlying credo deeply informed Terry’s life and his mission with T.I.

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that even the early years of Total Immersion were shaped by Terry’s understanding of the importance of conscious and strategic goal-setting. This week, we’ve reached deep into Terry’s archives to pull material from his “Swimmer’s Bible,” a self-published booklet he wrote and sold in 1991, just 2 years after Total Immersion was founded. This document exists only as a hard copy from Terry’s personal library (perhaps some early alumni have tattered copies) and has never been published online until now– he wrote it before the internet existed! Though T.I. was still in its infancy when it was published in ’91 (5 years before his best-selling Simon & Schuster book), Terry had already been coaching elite age-group and college swimmers for nearly 20 years and had achieved considerable success, developing 24 national champions between 1973 and 1988.

Terry’s primary aim with the “Swimmer’s Bible” was to share with average adult swimmers the same successful strategies that he had employed with the accomplished swimmers he had coached at the highest levels of elite competition. The following excerpt on goal-setting is the opening section of the “Swimmer’s Bible”– the fact that goal-setting was the introduction to his first guidebook to swimming is not incidental, but completely fundamental to his approach. He recognized, from years of successfully coaching high-level athletes, that how one thinks about one’s swimming is integral to how one performs. This understanding is a philosophical thread that connects the founding years of Total Immersion to its current incarnation, and his guidance from 1991 is as practical and effective now as it was then. Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

Total Immersion Adult Swim Camps: “The Swimmer’s Bible” (1991) — p. 1-5

(Scanned copy of original 1991 “Swimmer’s Bible”– Cover and p. 1-5)

The Breakthrough Season

Success strategies to get whatever you want out of swimming!

Success, particularly in training for athletic performance, is not the result of luck, but the predictable outcome of planning, concentration, and cultivating the basic talent we all have. No great success is ever achieved without great commitment. Your swimming can and should provide you with results that are deeply satisfying, and renew your enthusiasm, ensuring your long-term involvement. This could be anything from setting a world Masters record to simply swimming for peak mental, physical, and emotional health. You can achieve all your goals, but it won’t happen by accident. You need a success system, and we have one for you.

Achieving the Breakthrough Season– Six Steps to Success

Have a well-defined goal that really matters.

Believe totally that you have the resources and capabilities to achieve that goal.

Develop a strategy or plan for achieving your goal.

Execute that strategy with purposeful, effective, and consistent actions.

Monitor your progress and learn from your experience in pursuit of your goal.

Adjust your plan as necessary to reach your goal.

Who Needs Goals?

[Editorial Note: Triathletes are not listed because it was still a relatively new sport, hence T.I. was primarily teaching Masters swimmers and fitness swimmers at the time of this writing in 1991. This guidance naturally applies to triathletes, as well.]

Competitive Swimmers: Clearly, the answer is yes; those who define the outcomes they want to achieve greatly increase their chances of obtaining them. Goals engender passion, give power and meaning to what you do, strengthen your resolve to adhere to a training schedule, make a tight interval, do a drill correctly, etc. when your will is weak.

Fitness Swimmers: Yes. Nearly 70% of all Masters swimmers never compete, but they all attend workouts for good reasons: fitness, weight control, stress relief, etc. Swimming for health and enjoyment is no less important than training for competition. Doing anything without some sort of purpose eventually becomes dull, boring, and repetitive. If you allow that to happen, you’ve defeated your original purpose. Therefore, it is important to express your purpose for swimming, then set goals that will help you achieve it.

Know Your Outcome in Advance! Do this exercise in writing:

Setting the Goal

Professionals in the field of motivation and achievement believe strongly that the development and ultimate accomplishment of goals begins with a vision, and that the more vivid and specific that vision is, the better the chance of a successful outcome.

4-Step Goal Setting Process

List your goals. Limit to 5 or fewer to sharpen your focus and force yourself to prioritize. State them in positive terms. Describe them in specific and sensory-rich language– what, when, where, why, and how. Impose deadlines and time-frames.

Write a paragraph on why each goal has value. Describe how you will benefit from reaching your goals, what you will risk by not reaching them. Your goals should be challenging but realistic. They should have sufficient value and immediacy to carry you through difficulties, to inspire you to passion and extraordinary efforts when needed, but more importantly, to energize and reinforce you for consistent, persistent use of your resources day-in, day-out.

Inventory your strengths and capabilities, your resource to get the job done. You can do this best by recalling several past successes and capabilities that made them possible.

Identify resources and capabilities that you must acquire, develop, and improve to reach your goal. What has kept you from reaching this goal in the past?

Be consistent and persistent. Keep taking action until you reach your goal. Persist! Commit to applying your efforts over long periods of time. Persist! Nothing worthwhile comes easily or quickly. Persist! — personal credo of Ande Rasmussen, Masters swimmer from Austin, TX

Believe in Yourself

Develop an unshakeable faith that you can and will reach your goal. Belief is a catalyst for taking action– the biggest difference between success and failure. If you were guaranteed success, what actions would you undertake right now?

As recommended above, remember your past successes and see them in your mind as if they were happening now. Live and breathe the success of the past and project it into the present. Then use that to create a vivid mental image of your goal as reality right now. Experience your outcome on a daily basis, as being already true.

Develop a Plan to Make Your Goal Reality

Martial arts guru Bruce Lee said that 10 minutes of workout with mind and body completely focused is more valuable than 10 hours of going through the motions. How to do it? For adult athletes with limited training time: precise, effective, goal-oriented use of that time is critical.

Focus on 2-3 closely related events (in either stroke or distance), identify the capacities needed to perform well in them, and use the information acquired here at camp to plan a training program that devotes the bulk of your time and energy to enhancing those capacities. Minimize time spent on anything that does not directly enhance your chances of reaching your goal.

To assist in your planning process, consider finding a role model who is achieving what you want to [achieve]. Ask them to identify the critical abilities, attitudes, and training habits that permit them to perform as you would like to. Work at developing the same traits and habits.

Write down your plan, including:

Actions to take– what, how, and when you must do.

Beliefs to cultivate– affirmations and thought patterns.

Schedules needed– daily, weekly, and a total span.

Results in Real Time

Commit to purposeful activity directed at achieving goals that contribute to the mission! Do something purposeful each day to reach your goal. Even if you have no workout scheduled, you can still review your log book, refine a training schedule, or seek information that will improve your preparation.

Begin immediately. Even the greatest journey must begin with one small step, and nothing happens until you take it. Once your goal is set, don’t wait until your plan or conditions are ideal. Even if your plan is incomplete, it is important to take that first step, to be action-oriented. Have confidence that you can adjust and improve your plan as you go through experience and increased understanding.

Review your actions critically each day and evaluate what you have done to advance towards your goal. Compare actions and outcomes to the requirements of your goal. Be willing to make adjustments as you learn more. Examine your continuing motivation and commitment.

Learn From Your Experiences, But Don’t Be Limited By Them

Two thought patterns common to highly successful people which will prove useful to you:

Everything happens for a reason and a purpose, and it serves them. They think in terms of possibilities and benefits, though those may not always be immediately apparent.

Failure is an emotionally-charged concept which they do not entertain. There are only results– some successful, others are opportunities for learning experiences which improve chances for ultimate success.

The best way to measure the effectiveness of your personal training program is to keep a detailed diary or log book of practices and meets [or races]. Over time, the information collected will reveal successful patterns in your training, and make future planning a more educated process.

Course Correction

Peak performers exhibit the flexibility/adaptability to change direction when necessary and find more effective methods– the mental agility to balance the competing demands of work, family, and training.

When a training program leaves you feeling flat and stale rather than strong and sharp, when a race brings poor results, when a taper isn’t working– get more information, understand why, consider alternatives, don’t be complacent. You may simply need to consult with someone– a coach or another swimmer– who can take a more objective or informed view of your situation. Then be willing to try something new. Even failed plans have value because, by eliminating what doesn’t work, they help narrow the path to ultimate success.

It isn’t performing well that makes you feel great– it’s feeling great that makes you perform well.” — Dr. Jim Loehr, sports psychologist

Succeeding in Competition

“Psyching out” in competition can undermine the world’s greatest training program because physical skills and great conditioning are no match for self-doubt and nervousness. Sports psychologist Dr. Jim Loehr, author of the book Mentally Tough, says that the mental game of handling competitive stress can be taught just as systematically as a good stroke, and mental muscles [can be] conditioned just as predictably as your physical ones.

The most important trait for sports success is the ability to shut out stress, doubt, and distraction, and concentrate on the job at hand. Mental toughness, as Loehr calls it, means staying in a calm, focused state. Negative thoughts cause physiological reactions: increased heart rate, muscle tightness, shortness of breath, and reduced blood flow. Pre-race anxiety can even increase blood lactate levels. Positive emotions (Loehr’s “Ideal Performance State”– an internal feeling of high arousal combined with a profound sense of calmness, clarity, and control) produce desirable physiological reactions: greater muscle flexibility and increased endurance.

What can you do at meets [or races] to minimize anxiety and maximize calmness and confidence?

Project confidence even when you don’t feel it– “lying with your body,” as Loehr calls it. Anthony Robbins, author of Unlimited Power, says you can overcome fear and uncertainty by projecting energy, confidence, strength, and joy in your posture, voice, and mental state. Such actions can actually produce a shift in your emotions.

Enjoy yourself. Sure, competition can be stressful, but racing is your most direct opportunity to reap the rewards of your training. So, mount the block [or enter the water] with eagerness, not dread. When you have long waits between races, don’t sit around contemplating the next race– move around, make friends, socialize, stay loose. “In any kind of performance, we’ve found that the more you enjoy what you’re doing, the more all the other qualities fall into place,” says Loehr.

To shut out doubt and distractions just before the race, concentrate on one, well-focused technical point that will help you execute better.

A gentle warmup just before your race can also be very effective in calming your nerves and getting focused on what you can do to cultivate a swim that feels great.

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit. — Will Durant, philosopher

The post Strategies for Achieving Your Breakthrough Season: Success is Not the Result of Luck! appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 30, 2018

VIDEO: “Guaranteed” Speed– Swim Faster the Smart Way

(Top to Bottom: Terry, Lennart Larsson, and Tommi Patilla swimming the Gibraltar Strait, 10/11/13)

“It’s thrilling to have mastered a form of training that offers a mathematically precise—almost ‘guaranteed’—way of improving my speed. The accompanying video illustrates how it works…”

– Terry Laughlin

This week we revisit an October 2015 post from Terry, on developing “smart speed” with a deliberate and strategic approach, using the key elements in the Math of Speed, based on the formula Velocity = Stroke Length x Stroke Rate. It’s well worth taking the time to explore this approach to speedwork because, as Terry noted in this post, “40 years of data collected by USA Swimming has revealed that this is the closest thing to an algorithm for swimming success.” Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

[Editorial Note: Terry references the “Green Zone” in this post. For those not familiar with this, Green Zone refers to the most efficient range of stroke counts for a swimmer of any height. These are derived from data on the Stroke Length of elite freestylers, and modified to give ‘average’ swimmers a realistic-but-challenging efficiency target. When you keep your count in this range, you make every stroke count. Green Zone Chart available for FREE, in both meters, and yards, HERE.]

10/20/15

In a few weeks, I’ll mark the 50th anniversary of when I first got serious about swimming—i.e. training with an explicit goal of swimming fast. In November of 1965, I joined the newly-launched swim team at my high school, St. Mary’s in Manhasset NY.

For the next five or six years, I got faster each year simply because growing taller and stronger as I matured mattered more than the inefficiency of my stroke or generic nature of the my training. But at age 20 I plateaued. Though I was still maturing, I was already stroking as fast and working as hard as I could. In the 45 years since, speed has never again simply ‘happened.’

However, while I’ll celebrate my 65th birthday in just a few months, I’m still highly motivated to swim as fast as my physical capabilities, and limited training time, allow. Thus it’s thrilling to have mastered a form of training that offers a mathematically precise—almost ‘guaranteed’—way of improving my speed. The accompanying video illustrates how it works.

The first clip shows me swimming a continuous 100 yards. The onscreen graphics display the key elements in the Math of Speed, based on the formula Velocity = Stroke Length x Stroke Rate. However I’m far less interested in sprinting a breathless 25 meters, than in sustaining a brisk pace for a mile or more. That requires easy—and smart—speed.

My plan for this 100-yard swim included two elements.

I swam the first length at ‘cruise’ pace—a relaxed and restorative pace that feels as if I could swim indefinitely and never tire. This approximates the pace and effort I’ve used in marathon swims of 20 or more miles. On each of the next two lengths, I increased tempo and stroke pressure slightly. On the last length, I swam at what I call ‘brisk’ pace—strong, but quite controlled. It equates to how I like to feel in the latter stages of an open water mile race.

I counted strokes (as I do habitually) while swimming this 100. My plan was to take 13 strokes on the first length, 14 on the next two and 15 on the fourth. ( My “Green Zone” in a 25-yard pool is 13 to 16 SPL.) I missed my target counts by one stroke, taking 15 on the third length. As I increased tempo, pressure, and speed, I focused on keeping my stroke quiet and splash-free—as I always do when increasing pace.

From the video, I took split times, counted strokes, and timed tempo for each length. The seconds, stroke count and Tempo for each length are displayed on screen:

1st 25: 21.7 sec., 13 strokes, 1.24 sec/stroke

2nd 25: 21.7 sec., 14 strokes, 1.20 sec/stroke

3rd 25: 21.6 sec., 15 strokes, 1.16 sec/stroke

4th 25: 20.2 sec., 15 strokes, 1.06 sec/stroke

My 1500-meter pool pace (calculated by multiplying 25-yard split times by 66) improved from 23:52 on the first length to 22:12 on the final length.

Besides the efficiency skills of balance, stability, streamline, etc., this swim also displays a high level of pacing skill, which is critical to racing success at any distance from 100 meters up—and to maximizing your personal speed potential.

Few swimmers can maintain or increase pace on each successive 25 of a continuous 100. Fewer still can increase pace by 6.5% from start to finish. And here’s another thing to consider while watching this video. Drag increases exponentially as speed increases. So an increase of 6.5% in speed should result in a 47% increase in drag. Does it seem as if I’m working 47% harder on the 4th length than on the first or second?

The ability to generate easy speed requires practice of two kinds of skills:

1. The ability to keep one’s stroke efficient, relaxed, and highly integrated at a wide range of tempos and speeds.

2. The ability to precisely control and adjust stroke length, tempo, and pressure.

Both of these come from regularly performing challenging task or problem-solving exercises such as the one illustrated in the next two video clips, shot in a 25-meter pool. Those shown are the first and last in a series of 7 x 25.

I started at a tempo of 1.10 seconds/stroke, and increased tempo by .04 on each successive 25 (1.06, 1.02, 0.98, 0.94, 0.90.) My goal was to test whether I could maintain a consistent stroke count—i.e. travel as far on each stroke—on each 25, to a cumulative tempo increase of two-tenths of a second. At a tempo of 1.1 seconds, 17 SPL converts mathematically to a 25-meter pace of 22.4 sec 0r 22:24 for 1500m. At a tempo of .9, 17 SPL converts mathematically to a 25-meter pace of 18.8 sec or 18:00 for 1500 meters. That’s what I mean by ‘guaranteed’ speed.

When I first began using a Tempo Trainer, I adjusted in smaller increments—as little as .01 second—and was pleased if I could hold one stroke count while increasing by .06 of a second. Years of practice have significantly improved my ability to hold Stroke Length, while increasing Stroke Rate. As I noted in the post, “Want to swim like Katie Ledecky? You Can!”, 40 years of data collected by USA Swimming has revealed that this is the closest thing to an algorithm for swimming success.

As also noted in that post, training for Smart and Easy Speed starts with two steps:

1. Learn to swim consistently in your Green Zone range of stroke counts.

2. Patiently learn to swim each of those stroke counts at incrementally faster tempos.

To test your own level of Smart Speed Skills, download our free Green Zone chart and order a Tempo Trainer.

The post VIDEO: “Guaranteed” Speed– Swim Faster the Smart Way appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 16, 2018

The 4 Stages of Skill-Learning– and the critical Kaizen Loop of Continuous Mastery

This week we revisit one of our most popular blog posts from 2016– a post from Terry on the metacognitive aspects of skill acquisition (i.e. “learning how we learn”) and how that relates to Total Immersion’s mindful, kaizen approach to swimming. Below, Terry explains the stages through which we all must progress in learning any new skill, and why it’s so critical that the final two stages become an endless loop of skill mastery, as we pursue a deliberate, lifelong path of continuous improvement. Naturally, this approach applies to mastering any skill in life, so it’s not surprising that this article struck a chord with so many readers! Enjoy… and Happy Laps!

4/15/16

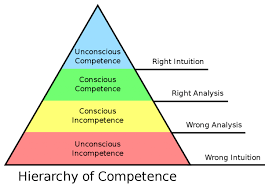

The Four Stages of Learning emerged from the field of psychology in the 1970s, and has since become widely familiar and accepted. It identifies four levels of competence one must experience in learning any new skill. Also known as the “conscious competence” learning model, it describes “the psychological states involved in the process of progressing from incompetence to competence in a skill.”

According to this model, we generally start out with a blind spot: “We don’t know what we don’t know.” We must recognize our deficit to progress further. Next, we must consciously acquire the skill, then consciously use it. By doing so, we gradually acquire the ability to use the skill somewhat automatically.

The four stages are called:

Unconscious Incompetence We fail to recognize that a higher skill level exists or that it has value. You may have escaped this stage quite early in your swimming experience. I didn’t do so for 25 years, until almost age 40. Until then, I believed my swimming potential was limited by a lack of ‘genetic’ traits. That notion was dramatically dispelled—in less than 10 minutes–when Bill Boomer taught me a balance drill, and I recognized I had a serious blind spot in my knowledge of technique… even after coaching with great success for nearly 20 years!

Conscious Incompetence Like most TI swimmers, the first skill deficit I identified was balance. For 25 years, I’d thought I had ‘heavy’ legs and the only solution was to kick harder. When Boomer taught me to align my head and spine and shift weight forward, I was stunned at how my legs automatically—and effortlessly—lifted to the surface. That remains my single most transformative moment in 50 years of swimming.

Conscious Competence For the next six months I thought of almost nothing but maintaining a straight line between head and hips, and leaning on my chest (a technique called Press Your Buoy which we taught until the late ‘90s), fearful that—after 25 years of unbalanced swimming—I would lose this magical feeling if I wasn’t explicitly focused on it.

Unconscious Competence When I finally trusted that balance had become a moderately-durable habit, I immediately adopted a new skill goal—Swim ‘Taller,’ which I’d learned would reduce drag. This change was just as challenging: For 25 years I’d focused exclusively on pushing water back. Now I had to train myself to ignore the hand pushing back and focus on the one going forward.

This amounted to a dramatic change in a pretty fundamental values system of traditional swimming—that I should place a higher value on extending my bodyline, than on pushing water back. The fact that I felt markedly better convinced me. Swimming Taller kept me occupied for several more months—during which I regularly made time to check on head-spine alignment.

As soon as Swimming Taller began to feel consistent and more natural, I again chose a new skill focus—Holding My Place. After reaching forward, my focus would be to consciously hold my place with the lead hand—then spear the entering hand past it. This was a more complex and challenging skill that the first two I’d tackled. Fortunately I was prepared—in two ways.

If I hadn’t already learned balance, it would have been physically impossible to Hold My Place. As well, when I began to concentrate on aligning head and spine, it was my first experience in trying to hold a single ‘stroke thought’ for an extended period. That was surprisingly hard at first, but got easier over time, as those skills moved into the level of Unconscious Competence.

When I tried to Hold My Place, I could feel my hand moving back. I had to learn to resolve the conflict between my intention and what I experienced. Fortunately, I was prepared for this far more demanding level of Conscious Competence, by nine months of prior conscious skill practice.

That occurred in 1989. In the 27 years since, I’ve never lacked for a new skill goal to maintain in Conscious Competence, which illustrates a critical distinction between the TI view of the learning stages, from that which is commonly taught.

The Kaizen Continual Loop

In the kaizen approach to mastery, learning is not a stairstep progression from Unconscious Incompetence, ending in Unconscious Competence, as shown in this illustration.

Rather, one’s goal should be to maintain a continual loop of mastery. Upon moving from Conscious to Unconscious Competence in one skill, immediately identify a logical next step. Recognize your Conscious Incompetence at a related, slightly more challenging skill and bring it into Conscious Competence, then work consciously on it until it happens more autonomously. Then start the process all over again, as illustrated here.

Here’s one more thing:

This process actually involves a change in the physical location in the brain where we process cognitive and motor skill. During the Conscious Competence stage, we process in the cerebral cortex, an area with especially dense neural connections. The cerebral cortex consumes a lot of energy; the same energy—oxygen and glycogen—used by the muscles.

When we achieve Unconscious Competence that activity is run by the cerebellum, which uses far less energy. Each time we learn a new skill this way, we not only increase our mechanical efficiency, we also increase our energy efficiency in a surprising way.

Learn the skills of Efficient Freestyle with the Total Immersion Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course!

The post The 4 Stages of Skill-Learning– and the critical Kaizen Loop of Continuous Mastery appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 9, 2018

PODCAST: Endurance in Swimming– Wow, It’s Complicated!

Last month we shared a blog post on “Endurance Skills: A Practice Set to Improve Balance, Streamline, and Focus.” This week we delve deeper into the topic of endurance. We revisit Terry’s March 2017 blog post on the topic of swimming endurance, featuring his interview last year in an episode of the “Mile High Endurance” podcast with Rich Soares and Bill Plock.

Highlights include:

Training for economy of motion and aerobic efficiency, as much as for work capacity

How to Swim Faster in an Ironman—and Feel Amazing

“Permission” to swim less: shorter, more effective training sessions

Here’s a brief description of their podcast:

“Mile High Endurance is your weekly connection to coaches, experts and professional athletes to help you reach your endurance and triathlon goals. Rich, Khem and Bill bring their passion for triathlon, cycling, running and other endurance sports to help you learn and enjoy being an athlete. Join them each week as they bring you the latest authors, coaching insights and relevant topics to endurance athletes all over the world.”

We at T.I. would like to thank the folks at Mile High Endurance for hosting Terry on their podcast for multiple episodes last year, to discuss and deconstruct many different aspects of swimming, and offer practical guidance for training. We’re happy to be able to share this engaging discussion and we’ll re-post Terry’s other podcast episodes in the coming weeks. If you prefer to skip Terry’s accompanying article (which discusses their conversation) and go straight to the podcast, scroll all the way down to the bottom of the post for the embedded audio.

Enjoy and Happy Laps!

Terry and friend David Barra sync swimming in Eleuthera, the Bahamas, December 2006 (Credit: Dennis O’Clair)

3/1/17

One week ago today, I recorded my second interview with Rich Soares and Bill Plock of Mile High Endurance. Our topic was What Does Endurance Mean? I opened the discussion by asking the hosts for their definition of endurance.

Bill said, since becoming an endurance athlete, he has subscribed to Ellen Hart Peña’s description of endurance as a ball of string. The string represents energy needed for effective muscle function. When you begin an endurance event, you send the ball rolling toward a distant wall, representing your finish line. Your goal is for the string to run out just as it reaches the wall.

I like that analogy as well. But to illustrate the complexity a swimmer faces, let’s consider three different ways to swim 1500 meters: in a pool race or time trial; in an open water event; or as the first leg of a triathlon.

When swimming a 1500m event in the pool, the ball of string analogy is quite apt. You want to have enough energy to be going with a full head of steam as you reach the finish, yet have nothing left as you get there. But even with a lap counter to let you know how much remains, it’s extremely challenging to make that string reach the wall.

Most athletes start too fast, and the string must be stretched more and more—often to the breaking point. Stroke length and/or stroke rate fall off markedly in the middle and last half and pace slows markedly. One needs highly developed pacing skills to roll that string out evenly for the entire 1500.

In a 1500m open water event, the goal is the same–run through the finish line chute having spent your energy wisely and nearly entirely. But without distance markers along the way, it’s very difficult to gauge. Even when I’ve swum quite well and fast, I’m generally far fresher at the finish of an OW race than at the end of a pool race and happily so. In part, this is because there are no turns, meaning you make little use of the body’s largest muscle groups—thighs and glutes—and because you don’t experience the oxygen deprivation of being underwater for as many as 65 turns and pushoffs.

In a 1500m triathlon swim the goal radically different: The smart triathlete, wants to have rolled out as little of the string as possible when you complete the swim leg, because that string will produce far more speed (relative to each discipline) on land than in the water.

This means that the best training for each of these examples will differ in important regards than for each of the others. I participate in the first two, yet my training during the colder months—preparing for 1500m/1650y pool races—undergoes some significant changes during warmer months preparing for open water events of 1500m or longer.

Rich Soares shows how much he enjoys podcasting.

Training for Economy

Host Rich Soares says that the longer he’s been an endurance athlete, the more he’s come to appreciate a highly nuanced definition: The smart athlete focuses on training for economy of motion and aerobic efficiency as much as for work capacity. In other words, train to reduce the demand side of the energy equation, rather than maximize the supply side. Seek the least amount of energy expenditure for the greatest amount of performance—and be grateful to have “string” in reserve as you cross the finish line.

Additional topics we discuss on this podcast include:

How much does land endurance help swimming and how much can swim endurance help land endurance? Does the training I do on a bike help my distance swimming ability in any way?

How much time must a triathlete devote to swim training to optimize their tri-swim?

How many hours of training does it take to increase bench press by 10%, run or cycle distance or speed by 10%, swim distance or speed by 10%?

How to Swim Faster in an Ironman—and Feel Amazing

Finally, there’s a great exchange where Bill reveals that he’s hit a wall with his swim speed—as many swimmers and triathletes have. No matter how much he trains, his swim pace never improves—and he routinely runs out the string during training. He often starts a set of 100m repeats at a brisk 1:30, then gradually fades—often to a pace as slow as 1:50.

Bill can do an Ironman swim in a respectable 1:10, but—given what happens during his training swims–wonders if it’s worth the effort it might take to swim faster.

When I explain the techniques that will allow him to both swim faster and become a far more ‘tireless’ swimmer—able to complete longer swims at a faster pace, and feel completely fresh upon finishing—Bill says “My mind is blown” upon realizing that the techniques and stroke emphases that will increase his efficiency are exactly the opposite of what he thought.

“Permission” to swim less

During the post-interview wrapup, Bill tells Rich: “I feel like Terry gave me permission to trade an 3000y training session for a 1500y session focused on increasing my stroke efficiency.” Why is this so? Because it takes far less time and dramatically less training volume to increase economy—the priority Rich cited—than it does to make that “ball of string” larger. And shorter training sessions are almost always more effective in doing so.

Please give a listen. I promise you’ll enjoy.

We’ve planned at least one more interview segment where we discuss the advantages of training designed to created adaptations to the brain and nervous system—instead of the aerobic system—and how to get it. Which will also be the topic of next week’s blog. Stay tuned.

Learn the skills of Efficient Freestyle with the Total Immersion Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course!

The post PODCAST: Endurance in Swimming– Wow, It’s Complicated! appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 2, 2018

Halloween Plunge: Swimming in Cold Open Water

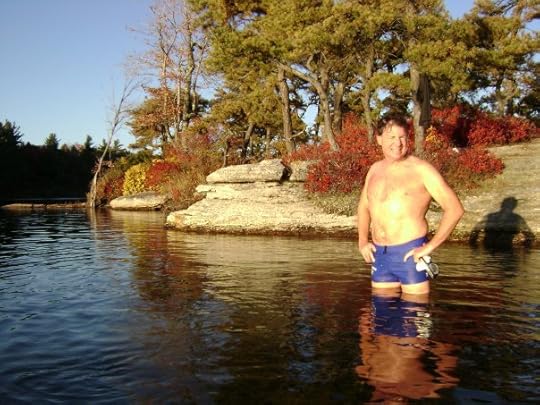

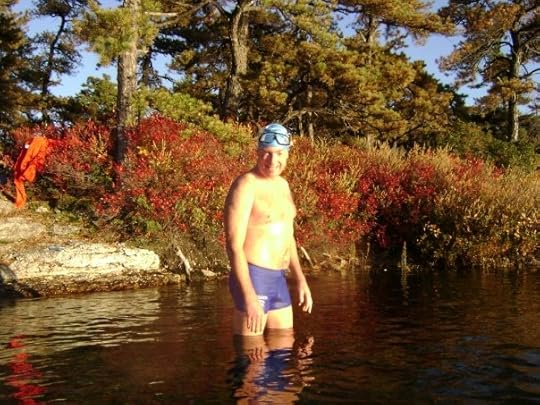

(Terry post-swim at Lake Awosting– in 53F–Nov. 2009, a year after this ’08 blog)

FROM THE ARCHIVES:

As the weather cools, we take a look back at a post on cold open water swimming that Terry wrote for the T.I. blog in late Fall 2008. He first describes a short Halloween swim with a friend in 45 degree (Fahrenheit) water at a local lake, and then shares insights on cold water swimming from famed long-distance open-water swimmers, Lynne Cox and Lewis Pugh, including some of the scientific research from cold water experiments conducted on Cox. Cox is best known for being the first person to swim between the United States and the Soviet Union, in the Bering Strait. She also swam more than a mile in the waters of Antarctica, which she recounted in her 2004 book, “Swimming to Antarctica.” Lewis Pugh is a British- South African endurance swimmer and ocean advocate. He has been described as the “ Sir Edmund Hillary of swimming” and was the first person to complete a long-distance swim in every ocean of the world; he frequently swims in vulnerable ecosystems to draw attention to their plight.

PLEASE NOTE: Extreme caution must be exercised when swimming in cold open water. The swims described in this blog were undertaken by expert long distance, cold open water swimmers. Extensive experience is needed to attempt this type of swimming, as it can lead to hypothermia and other serious medical conditions, and is potentially fatal. Always use good judgment and prepare properly with appropriate precautions if attempting cold open water swimming– be smart and stay safe!

(Terry biking around Lake Awosting with friend Willie Miller, en route to swim– Nov. 2009)

(Terry biking around Lake Awosting with friend Willie Miller, en route to swim– Nov. 2009)

11/9/08

Crazy Men in Halloween Plunge

Willie Miller and I swam at a local lake on Oct 31, Halloween. It had snowed four days earlier and there were still patches of snow an inch or two deep alongside the trail, and some snow and ice on the trail at points as we biked to the lake. The higher we climbed, the more snow we saw. We briefly questioned our own sanity, but our sense of excitement over doing something so “out there” was stronger than anything that might dissuade us.

A little background: Willie, Adirondack Masters Chair Dave Barra (a TI open water coach), and I had been swimming in open water continuously throughout the fall. In early September, the water temp was about 70F and we swam approximately an hour, three times a week. When the water dropped below 60 in mid-October, we shortened our swims to 25 or 30 minutes. We often saw other swimmers during September, but saw only two other swimmers in October, the last one around mid-month, when the water temperature was 57F.

With water temperature dropping gradually over the eight weeks between Labor Day and Halloween, we found the adjustment quite easy. There was some initial discomfort at 56-58F, but within five minutes, we’d feel just as comfortable in the core as we had at 70F. We were quite aware of the water’s coldness, on our skin, but it never penetrated.

(Terry’s friend, Willie Miller, pausing on the bike ride to swim in Awosting– Nov. 2009)

The complicating factor was less water temperature than the fact that, before and after swimming, we ride mountain bikes between our cars and the lake – 30 minutes uphill before the swim and 20+ minutes downhill afterward. The uphill ride is a good warm-up, but the downhill ride – with the addition of wind chill and subtraction of warming exertion – sometimes left us quite chilled. By mid-October, with days growing colder and shorter, we would return to our cars near dark and with air temps once or twice in the mid-40s. On Oct 15, an overcast and blustery day with air temp in the high-40s, Dave and I swam 40 minutes in 56F water and felt quite chilled as we finished our swim. By the time we got back to the cars, both of us were pretty well frozen, with hands and feet so numb we could hardly feel the pedals and were fumbling as we tried to shift gears. After that we made sure to complete our swims before the cold could penetrate.

(Terry, pre-swim, at Lake Awosting– Nov. 2009)

Which brings us to Oct 31. For all the snow around the lake, the water, as always, looked inviting. Our first immersion was unquestionably painful. Standing ankle-deep for a few moments, my feet hurt as they do when first submerged in a bucket of ice water. It was stingingly cold, but quite bearable, as we waded to the “shrinkage zone” and paused for a few moments there. When I crouched to submerge my torso, I began to gasp uncontrollably and had to stand again to regain control. When I crouched again, the gasp reflex had subsided a bit. I stayed there until my breathing slowed, then immersed my face experimentally to see if the gasping would resume. When it didn’t, I pushed off into a glide and began stroking.

What was surprising was the “ice cream headache” on the back of my neck, which I’d experienced 9 days earlier in 53F water and seemed no worse than before. But my hands and feet quickly went numb, my skin burned everywhere else, and even my teeth felt frozen. I decided I’d be happy to swim just a few minutes or, say, 200 yards. But as I went on and felt no more discomfort, I entertained the possibility I might hold out a bit longer – perhaps all the way around the near cove, which is maybe 200 yards of swimming, and then back, as the crow flies, to the rock where we entered.