Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 10

October 7, 2017

Can you swim an EASY Butterfly? Part 1 of 3

What is Easy Fly?

Easy Fly is a specialized way to learn and swim butterfly, refined by Total Immersion over the past 12 years. and designed to allow swimmers of any age or athletic ability to learn a smooth, relaxing and rhythmic butterfly within hours . . . then to progress to swimming butterfly for longer distances (200 yards or meters for many; a mile or more for some) within few weeks or months, by following thoughtful methods of practice oriented to improving and imprinting efficiency.

While Easy Fly is designed to prioritize ease more than speed, it can give competitive swimmers—especially Masters–the potential to set and improve on personal records and perform with distinction in competition. This ‘secret’ to Easy Fly is taking advantage of existing/natural forces to replace work traditionally done by the muscles.

Is Butterfly truly the hardest stroke?

If you’ve read or heard descriptions of butterfly in the press, you know that it’s unfailingly described as grueling. And it’s not just the media that thinks of fly this way: Swimmers often swim the stroke specifically to get a ‘good workout’ from just a single lap. Swim coaches regularly inflict butterfly repeats on wayward swimmers as punishment for some practice transgression. The swimming mainstream considers butterfly the aquatic equivalent of ‘hard labor.’ Thus, it’s no surprise that newer or non-competitive swimmers often view butterfly with a mix of intimidation and fascination.

In June 2010, Wall Street Journal reporter Kevin Helliker, in the article For the Athlete Who Has It All, wrote “Like many fitness swimmers, I can go mile after mile of freestyle without stopping. But a single lap of butterfly leaves me gasping. In an age of ultra-marathons, Ironman triathlons, and crowds chugging up Mount Everest, long-distance butterfly swimming is becoming a new frontier for fitness fanatics. The mere sight of a swimmer doing lap after lap of butterfly garners attention of the sort that merely finishing an Ironman triathlon no longer generates.”

Why is the ability to swim lap after lap of fly so rare that it leaves other swimmers semi-awestruck? According to Helliker, “Fly swimming requires enormous strengthening of every muscle in the body.” One of the distance flyers quoted in the article, Tom Boettcher (the author of a book called Core Training), told Helliker he spends two hours training in the gym for every hour in the pool.

Yet if you closely study Olympic medalists, such as American swimmers Michael Phelps and Dana Vollmer, you’re more likely to be struck by their rhythm and grace. The power in their strokes is more inherent than overt. Indeed, it’s while swimming butterfly that humans most resemble those most graceful of all swimmers–dolphins.

Vollmer, who broke the women’s world record in winning the 100-meter butterfly at the London 2012 Olympics, told the NY Times just days before her record-breaking swim: “I really think about being light in the water and everything moving forward as I swim. The butterfly is really about grace and rhythm.” She added: “People struggle in the last 25 meters; that’s when I really focus on staying as light as I can with my arms, and not punching down with my legs,”

London 2012 Olympic Champion Dana Vollmer

66 y.o. TI Founder Terry Laughlin

So which is the real butterfly—graceful water-dance or energy-sapping, muscle deadening struggle? This series of blog posts will explain the difference between ‘ButterStruggle’—the version the vast majority of us fall into—and ‘Easy Fly’, a revolutionary new way to swim butterfly. Easy Fly is based on the fluent grace of elite swimmers like Dana Vollmer, but anyone can learn it.

Coming Next: Part 2 40 Years of HARD Fly: Why I Almost Gave Up on Swimming Butterfly

Click here to learn more about our newest Self Coaching Course: Butterfly, Backstroke, and Breaststroke Made Easy

The post Can you swim an EASY Butterfly? Part 1 of 3 appeared first on Total Immersion.

October 5, 2017

Guest Post: A goal without a plan is just a wish!

This week’s guest post was authored by Ed Horne (white cap in the video) who completed a Gibraltar Strait swim with swim partner Michael Fabray in June 2017.

Well, the goal was simple . . . I wanted to join the list of swimmers who have swum from Europe to Africa across the Gibraltar Straits, joining the ranks of such renowned swimmers as Colin Hill (founder of Chillswim), Simon Murie (founder of Swimtrek) and, of course, Total Immersion founder, Terry Laughlin, who completed the swim with two TI compadres—Lennart Larsson of Sweden and Tommi Patilla of Finland—in October 2013.

But, as I lay there in my hospital bed on 26 September 2015 only 24 hours after receiving a ceramic replacement left hip (the original had atrophied following a skiing accident in March 2012), the plan was going to be a little more complicated!

By the end of March 2016, I had confirmed my slot for the swim for late June 2017 and had worked with a personal trainer to generally improve my physical well-being including walking without a limp and strengthening my core. I had got back into the pool and could reasonably swim for 60-90 minutes. With 15 months to go, all I had to do now was:

Jettison the wetsuit in open water;

Improve my base swim speed and stroke efficiency; and

Get plenty of sea swimming experience.

During this time, I was also guided by a great piece of advice from Professor Greg White, an elite performance coach, who amongst his many ‘claims to fame’ coached the English comedian, David Walliams, to swim both the English Channel and the length of the River Thames for charity. Greg’s advice was simple: ‘Make sure you enjoy the process, because you cannot predict what will happen on the day’!

Jettisoning the wetsuit was relatively easy; I put two river swim events on the calendar, a 6K/3.7mi swim in late July 2016 and a 10K/6.2mi swim in September. As practice, I swam without a wetsuit both in a local lake and, a couple of times, in Dover Harbour with the (soon to be) Channel swimmers.

Improving my base swim speed and stroke efficiency was the key to completing the swim. This brought me into contact with Tracey Baumann, a very experienced Total Immersion teacher and Master Coach. Tracey has a cadre of excellent open water swimmers who this year alone have done a 20-hour English Channel swim, a 2-person English Channel relay and a Jersey to France solo swim. I found myself in exalted company.

Over a series of one to one lessons, Tracey managed to (i) adjust my head position, (ii) commence my breathing rotation earlier, (iii) shorten and soften my hand entry position, (iv) steepen my arm entry ahead of the catch, (v) correct my over-rotation and (vi) introduce me to the 2-Beat kick! In just four months, she remodelled my stroke, improved my stroke efficiency (as measured by stroke count in a 25m pool) by 15%, and my base swim speed had improved by 10%. This ‘old dog’ had clearly learned new tricks.

Ed displays TI form in mid-swim—streamlined legs and “Front Quadrant” timing.

During this period, my personal trainer continued to work principally on shoulder strength, flexibility, and core development.

The final piece of the jigsaw was to increase my sea swimming experience. With my window booked for the end of June 2017, I would only have six possible opportunities to get into the sea, knowing that, in early May, the temperature would be no more than 53 degrees. So, during the winter, I joined the cold-water enthusiasts/lunatics at Tooting Bec Lido in South London and swam outdoors unheated throughout the winter. The temperature in January dropped as low as 35F. The endorphin buzz and general health benefits from this were enormous and I will continue this practice in future years. Anyway, after sea swims of 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours and 5 hours on successive weekends all in sub-60 degree water, I tapered back down to 2 hours for the weekend before we flew out to Spain.

On the morning of the swim, I could confidently look at myself in the mirror and happily confirm two things:

I was as well prepared as I could possibly be; and

Whatever happened, I had enjoyed the process.

I hope that you enjoy the youTube video beautifully compiled by my wife and daughter for me. It was a truly memorable and in many ways life-changing event for me. I had proved to myself that I could make my own wishes come true both by planning properly and, as importantly, executing on that plan.

I cannot thank Jerome Sawyers (personal trainer), Tracey Baumann (Total Immersion teacher) and Emma France (Channel Training co-ordinator) enough for their help in allowing me to realise my goal.

Last but not least, I must mention my good friend and swimming partner, Michael Fabray. We intuitively worked as a team throughout the swim whilst spurring each other on. A little testosterone in the water on the day clearly increased the intensity and enabled us to swim out through the incoming tide for the first hour. Indeed, I am convinced that it was this close partnership that enabled us to complete the swim in a very respectable time. I think for both of us it was a shared experience that neither of us will ever forget.

I am genuinely not sure what is next but . . . I know that there will be a next!

Ed Horne, a 62 year old resident of London, England is a member of both the RAC Swim Team and the South London Swimming Club. Over the last seven years, Ed has become an experienced open water swimmer completing other notable swims including The Hellespont (from Europe to Asia), Coniston Water, the river Dart 10K and the 14K Thames Marathon (aka The Bridge to Bridge).

The post Guest Post: A goal without a plan is just a wish! appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 25, 2017

Guest Post: Swimming Nevis to St Kitts the TI Way

Our regular mid-week guest post comes from Jim Nostrum who recounts how he progressed, in just three months, from being able to swim 100 yards of continuous freestyle to an almost effortless 2.4-mile swim from the island of Nevis to St. Kitts.

I have always been a very average swimmer. I learned old-school freestyle technique as a kid at my local YMCA. As an adult, my distance swimming was limited to a handful of short distance triathlons, and the swim was my weakness in these races. I’d become resigned to thinking I could not become a strong distance swimmer without a lot of laps, paddles, and time.

Over the last 10 years my fitness routine has been devoted exclusively to road biking. A back injury kept me from running, and swimming was something I did occasionally at my health club to help break up my biking routine. I usually swam 20 to 40 minutes, mixing freestyle with breaststroke. I could swim only 100 yards of freestyle before I got winded, then would swim breaststroke to recover from fatigue.

Last November, a friend of mine, who has always been a strong swimmer, suggested we both train for the Nevis to St Kitts Channel Swim. I was not sure I could manage a 2.5-mile swim in open ocean. My open water experience was limited to short (a mile or less) lake swims more than 20 years ago. Nonetheless, I agreed to do the event that was scheduled in late March.

I began pool training for the swim in December. I started adding laps and using paddles in my routine. After a few weeks, I found that I was sore and could only manage an hour of slow freestyle. Then, in late December, I found some TI videos on YouTube and purchased your Effortless Endurance Self Coaching Course and the “Total Immersion” book.

Almost overnight I found myself improving! Using your tips on head position (“release your head”), “stroke thoughts” and “shaping the vessel” dramatically changed how I felt in the water. Quickly, I was swimming freestyle almost effortlessly and found myself able to focus on every stroke as I tried to limit the bubbles around my hand and perfect my 2 beat kick. By early March, I had completed several 4,000 yd training swims in approx 1.5 hours and felt great at the end of each session. I felt ready for the ocean.

The Nevis/St Kitts Channel swim in late March was outstanding! Despite no ocean swimming experience, I was comfortable and relaxed. There was some chop/swell as we crossed the channel, but your tips about how to stabilize myself made all the difference. I enjoyed the entire swim and finished respectably in 1hr 47 minutes.

Jim Nostrum comes ashore on St. Kitts after swimming from Nevis in the background.

TI has made a huge difference in my swimming and fitness and has helped me to balance a very busy life. Thanks again Terry for sharing your experience and knowledge.

Jim Nystrom is an aviation professional and lives with his family in Scottsdale, Arizona. Swimming is an important part of his life and is a great complement to his road biking. In addition to the physical benefits from his time in the pool, he enjoys the focus, learning, solitude, and rejuvenation that swimming gives him, especially as he maintains a very busy travel schedule for his job. He is now working on mastering bilateral breathing and has also begun to explore the benefits of stretching.

The post Guest Post: Swimming Nevis to St Kitts the TI Way appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 21, 2017

Podcast on Bilateral Breathing

This week, our mid-week post is a podcast I recently recorded with Rich Soares of Mile High Endurance on the topic of bilateral breathing.

Our interview begins at the 25:00 mark of this audio file.

http://www.totalimmersion.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Episode_082_Terry_Laughlin_of_Total_Immersion_on_Bilateral_Swimming.mp3

Rich and I discuss a blog post I’d written: What prompted me, after 28 years, to begin breathing to both sides?

Twenty-five of those left-side breathing years were pre-TI, so my breathing habits had become mostly unconscious incompetence.

Breathing to the right for the first time (in 1992) felt uncomfortable, but alerted me that my left-breathing was inefficient, because I took two more strokes for 50 meters than when I breathed to the right.

Yet I was initially trying to achieve the same level of comfort when breathing to the right side. So left-side breathing, while less efficient provided the benchmark I tried to match on my new breathing side.

However, because my right-side breathing lacked bad habits that had built up over 28 years of ‘unconscious’ breathing, it progressed fairly rapidly.

Honestly cannot recall the time when right side displaced left for me in setting the standard for left side breathing technique, but I can remember the specific breathing skill that I recognized I was better at on my new breathing side, I had a noticeably more patient lead (left) hand while breathing right. So my first example of Conscious Incompetence was to try to make my lead (right) hand more patient, while breathing left.

I now keep my head low while breathing to the left.

Next I noticed that I slightly lifted my head while breathing left . . . which caused my lead hand to stroke prematurely. So that became Conscious Incompetence item #2, And so on.

Just as I do on the right.

Enjoy the podcast.

The post Podcast on Bilateral Breathing appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 16, 2017

A Simple, Guaranteed Way to Improve: Time Yourself

Do you know your time for 100 yards? Not your time for a single all-out time trial, but the time you would record at a relatively relaxed pace. A pace you could repeat three to five times, resting less than a minute between trials. I would guess that a minority of those reading this post would answer in the affirmative.

My guesstimate is based on surveys we conduct of participants in our Open Water workshops or camps. Typically, about 75 percent report that they’ve participated in a triathlon or open water swim. But fewer than 50 percent know their time for 100 yards or meters.

To me this is putting the cart before the horse: The most reliable baseline for being able to improve performance through more effective (and personally relevant) training is to know your time for 100 yards or meters. And even if you have no plans to swim in an organized event, this information can be invaluable to personal improvement and mastery aspirations.

The Power of Two Metrics

Now that I’ve made the case for you to begin recording your time for short sets (three to five repeats) of 100 yards, I’ll urge you to track a second metric at the same time—stroke count or SPL; Tempo or stroke rate; and/or RPE, Rate of Perceived Effort. Just as you must know both length and width to calculate the area of a square, knowing time plus a second metric (i) gives you invaluable insight into how you ‘constructed’ that time; and (ii) helps develop critical skills for steady pacing.

100 Metres: Three Ways

Here are the three ways in which I combine 100-yard time with a second metric to gain more complete information about the quality and repeatability of my swims. Each requires you to swim only a short set of 3 x 100 to gain invaluable insight into how efficiently you create more speed.

Time + Tempo: This requires a Tempo Trainer, which I would urge you to make standard training equipment, if it’s not already. Time yourself at a range of tempos within your Tempo Comfort Range (your stroke doesn’t feel rushed.) For this article, I’ll use a starting tempo of 1.25 seconds/stroke (mode 1 on the Tempo Trainer). Use a different tempo if you feel more comfortable.

Swim 3 x 100 at 1.25 tempo. Your goal is to record the same time on each repeat. Doing so means you have kept both Stroke Length and Stroke Rate consistent. This is the first skill of effective pacing.

Next, swim 3 x 100 at 1.25, 1.22, 1.19 tempo (tempo increases by .03 sec. each repeat.) Your goal is to swim faster on each repeat. This means you have effectively converted greater stroke rate into more speed.

If you succeed at that, try the same set at tempos of 1.25, 1.23, 1.21. A smaller increase (.02 sec) in tempo requires more skill to swim faster. If you do not succeed at the second set, repeat it at tempos of 1.25, 1.21, 1.17. A larger increase in tempo requires less skill to swim faster.

Continue experimenting with short sets like these until you find the smallest increase in tempo at which you can descend a set of 3 x 100.

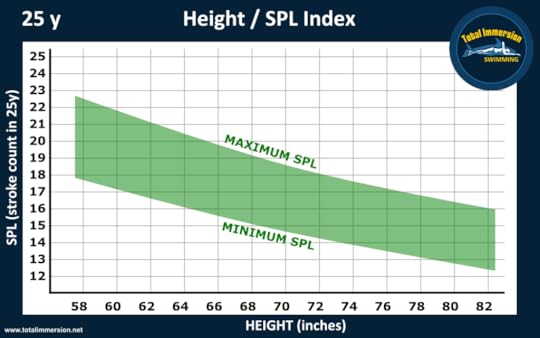

Time + SPL: This requires you to keep track of your stroke count for 100 yards. If you find that difficult, substitute sets of 3 x 50 yards.

For this article, I’ll use a 100-yard total stroke count of 65 as a starting point. You should choose a stroke count that is (a) within your Green Zone and (b) at which you feel highly comfortable.

Find your efficient stroke count range of 25y pools.

Swim 3 x 100 at 65 strokes. Your goal is to swim the same time on all three. Doing so means you have mastered the first skill of effective pacing—keeping both Stroke Length and Stroke Rate consistent.

If you succeed at that, swim 3 x 100 at 65-64-63 strokes (reduce SPL by slightly lengthening your stroke. Your goal is to swim the same time on all three repeats.

If you do not succeed at the first set, try 3 x 100 at 65-66-67 strokes with a goal of repeating the same time on each.

Çontinue experimenting until you can subtract two or more strokes per 100 during the set and maintain the same repeat time.

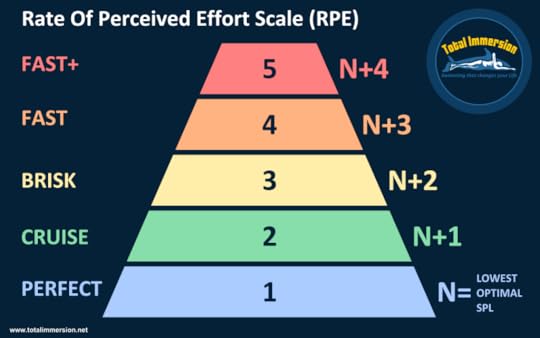

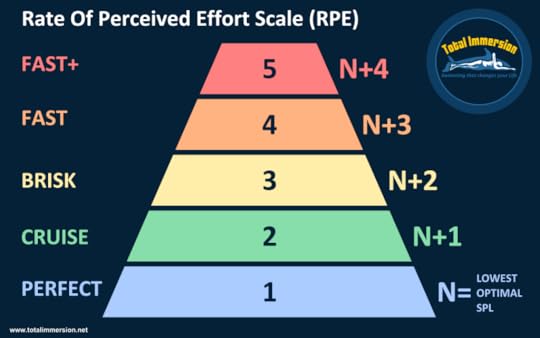

Time + RPE: RPE is an acronym for Rate of Perceived Effort–a fairly accurate self-assessment of how hard we’re working. This measure becomes far more accurate with regular practice. In Total Immersion, we employ a 5-point RPE scale.

TI-RPE-Scale

Swim 3 x 100 at RPE-1, the easiest, most relaxed pace of which you’re capable, with the most impeccable technique. How different is that pace from your normal 100-yard pace? Repeat several times (over a week or two), trying to reduce the difference between your RPE-1 pace and normal. (Hint: Strategies you employed in the Time+Tempo and Time+SPL sets should work here too.)

Then swim 3 x 100 at RPE-1, RPE-2, and RPE-3. How much faster do you swim by increasing your RPE? Experiment with this set several times over a week or two to see if you can gain more speed with less increase in effort.

May your laps be as happy—and purposeful—as mine.

The post A Simple, Guaranteed Way to Improve: Time Yourself appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 14, 2017

TI Technique and Neurosurgery Training: A Survival Guide…

This is another in a series of mid-week guest posts by TI coaches and fans. This one is by Ioannis Karampelis, MD.

On a September afternoon in 2005 I was wandering around a Barnes & Noble bookstore in Buffalo, NY, trying partly to kill time, partly to see whether a book about self-teaching for beginning swimmers was available.

Coming from Greece—a land blessed with beautiful, open seas where I swam for as long as I can remember—to this country as a fresh, foreign medical graduate, I hoped to find something that would improve my swimming technique. Most swimming books looked like hard-core training manuals: Full of programs dictating intensity levels and featuring tables depicting target heart rates and lap durations.

It was a revelation when I came across Terry’s “Blue-and-Yellow book.” Everything made sense: the greater importance of the shape of the vessel compared to its engine power, the science-based description of the importance of streamlining and stroke length, the explanation of the role of the chest cavity in determining the body’s center of gravity. I was hooked.

Then followed the DVDs and endless hours of slow, progressive drills. Patiently finding my own “sweet spot”, how to breathe better on both sides, front quadrant swimming . . . etc . . . etc.

I started a neurosurgical residency in 2007. It was a 7-year marathon. Few other professional training courses are so demanding in terms of physical, emotional and mental powers that need to be cultivated and ingrained to the person going through it.

Our days as residents would regularly start around 5 am and end around 8 pm. We would still work the next day after being up all night when we were on-call. Most of us would leave the hospital dead tired, wishing to go straight to bed.

I was no different. But somehow, I elected to keep making a stop at the nearby swimming pool, just 100 yards from the hospital, to practice TI, before going home.

This was one of the smartest things I elected to do. It was not just that I was getting better at swimming.

After a while I noticed that I was getting out of the pool feeling less tired, needing less sleep, and waking in the morning feeling better overall.

I felt restored as I came out of the pool. I could tolerate longer hours of standing in the operating room without backache, In my work, I could feel my hands and arms coordinate better with the rest of my body and I could sense more fluidity in my surgical technique.

Above all, swimming and the TI technique helped me tremendously in relieving the daily stresses of work, rejuvenating my psychological resources and sustaining my body through very tough times. Progression in swimming technique generated positive feedback for progress in mind and spirit.

Balance and streamlining in the pool would find a parallel in balancing my acts and thoughts during interpersonal interactions and streamlining my daily work in the hospital.

I often say to my friends that I survived residency because of the support I got from my mentors, family and TI. To this day, I feel eternally obliged to Terry Laughlin and his commitment to make a change in peoples’ lives. A change that goes beyond becoming a better swimmer.

TI and its mastery, as George Leonard would no doubt agree, is an endless path. Along the way, we honor the process more than the results, we cherish the journey more than the destination, we acquire wisdom by the epochs and not by the instant.

Ioannis Karampelas is a neurological surgeon practicing is St. Cloud, MN. He continues to enjoy the plateau of focusing in each focal point time and again. He recently experienced first class instruction and feedback in a Twin Cities TI freestyle course from outstanding teacher Tim Walton and decided to share some of his TI experiences. While in the pool, part of his brain is still able to ponder upon the things he values the most: personal health, science, culture, and above all, family and the future of his children.

The post TI Technique and Neurosurgery Training: A Survival Guide… appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 9, 2017

Do you exhale from mouth or nose?

Twenty years ago I’d never thought about nose-breathing. But then I read the book Body, Mind, and Sport by Dr John Douillard. In it he endorsed training for aerobic sports (walking, hiking, running, and cycling) with nose breathing. In ayurvedic practice, nose breathing encourages deeper breathing and fuller relaxation. I tried it and enjoyed it.

In running and cycling, you can both inhale and exhale from the nose. I did experience the deeper breathing and relaxation that occurred when I tried it while walking, running or cycling. (Changing terrain—i.e. going uphill—made it very challenging.)

But while swimming, you must inhale through the mouth. While exhaling however, you have a choice. When I inhaled though my mouth and exhaled exclusively from my nose, I noticed the same effects I’d felt while nose breathing on land.

So I began to make a regular practice of exhaling through my nose during warmup/tuneup and technique-intensive practice, and while swimming at tempos slower than 1.2 sec/stroke.

These days, I exhale from both mouth and nose, depending on circumstances. When I’m super-relaxed, I exhale all or mostly through my nose, which helps both mental and physical relaxation. As I increase speed, effort and/or tempo, and need to clear a greater volume of air exchange more quickly, I still use both, but the mouth exhale predominates.

(I inhale through my mouth, exhale primarily through the nose, while doing technique-intensive practice.)

The post Do you exhale from mouth or nose? appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 30, 2017

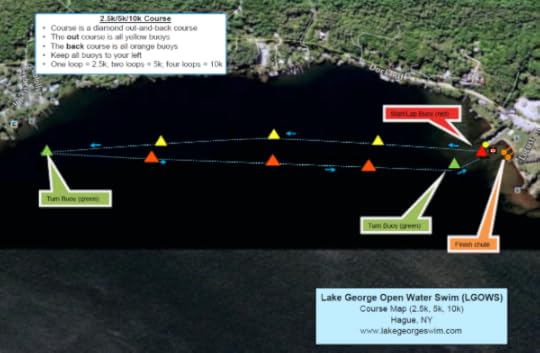

The Joy of Swimming-in-Synch with my Daughter

Last Saturday, Sept 26, I swam my second open water event in two weeks, and second of the summer. It was part of the Lake George Open Water Swim (LGOWS) in Hague NY, at the northern end of Lake George, in the southern Adirondacks. They offered 3 distances 2.5K, 5K, 10K. The course was an elongated diamond shape. One loop for 2.5K. Two loops for 5K. Four loops for 10K. At times in the past, I’ve swum all three distances (though not on the same day.) There were 271 entrants total from 21 states and the UK, the largest number the race organizers had ever attracted—reflecting the steady growth of interest in open water swimming and the growing reputation of this event, in its 6th year.

I chose the 2.5 K (1.55 miles) because it would be the longest distance—by 55 percent—I’d swum this summer. And I made plans for a road trip and a swim-together with my daughter Carrie Loveland. This would be the first time in about 10 years that Carrie and I would swim in the same event. I hope to do it again soon.

Indeed, unless Carrie had agreed to join me for LGOWS, I doubt I would have entered myself. Our plan was to swim the entire way together, while synchronizing our strokes. We’d done ‘synch swims’ for 200m in Lake Minnewaska, but had never attempted one in an official event, nor for a distance as great as 2.5K. Because I’m 7 inches taller than Carrie with a much longer reach—and a highly efficient stroke—she would have to attain great stroke length and efficiency to match strokes with me.

Synch-swimming is absolutely my greatest pleasure in open water. I begin practicing it with friends in Lake Minnewaska in 2001 and noticed it made the time and distance fly. It takes considerable practice to make the micro-adjustments in stroke length and rate, and in your course to not only keep your strokes in synch, but to coordinate your heading to stay closely abreast while minimizing contact. My longest synch swims have been:

10 miles in 4h 50m from Lanai to Maui in the Hawaiian Islands with David Barra in 2010. Willie Miller swam with us, but at a faster stroke rate.

11 miles in 5h 10m across Gibraltar Strait in 2013 with Lennart Larsson and Tommi Patilla in 2011.

10 miles from Corsica to Sardinia in 4h 30m with Lennart and Tommi in 2015. This time we found it much more challenging to stay in synch, though Tommi and I swam the last 2K at a fairly brisk pace in perfect synch.

Carrie and I had no plans for a brisk pace at Lake George. Rather to swim quite easily and deeply immerse ourselves in the whole experience.

The air temp was a chilly 46F at the 7:45 am start which made the 72F water feel positively balmy. Carrie and I positioned ourselves at the back of the pack and took our time to let the field clear out a bit after the starter’s horn sounded. We immediately fell into a comfortable mutual rhythm, Carrie to my left.

After breathing bilaterally for the first 400m I breathed mostly to the left to keep Carrie in view. She breathed to the right to do the same. Each time I looked I could see that our outside arms were stretched forward in parallel and our inside arms recovering in synch. I also saw the bright morning sun and green hills on the lake’s eastern shore. And on many strokes I recited a mantra of gratitude for the beautiful day and beautiful experience shared with my daughter.

As we approached the green turnaround buoy at the course’s southern end, the leaders in the 10K field (the 5K would begin about an hour after the conclusion of the 2.5K) began passing us with impressive speed. We stayed calmly in our little bubble of synchronization as they passed on both sides.

We paused at the turnaround buoy to check in with each other, survey the course and take in our surroundings. As we swam the homeward leg the breeze picked up, but the chop felt like it was pushing us home. We came upon two other 2.5K swimmers, swam with each for a while, then gradually pulled away, while still maintaining our very relaxed pace.

We made steady, easy process past the orange buoys which marked the eastern (homeward) leg of the course, until we passed the third and last. With the sun slightly behind us, then were quite easy to see as we approached them. We could now once again see the bottom beneath us.

Very soon we rounded the final green buoy and made a left turn toward the finish chute. With about 100 meters to go, it became too shallow to swim so we got to our feet. The timing clock read 1:13:38. To have our finish be considered official we would have to cross the timing mat (each swimmer wore timing chips on their ankles) by 1:15:00. At 1:14:50, hand in hand, we strolled nonchalantly across the finish line, 77th and 78th in a field of 86 starters.

We stand just beyond the finish line shortly after strolling across it.

Following the swim we spent an hour, catching up with many good friends and waiting for other friends in the 10K field. I look forward to more days like this—especially those I can share with family—in the not-too-distant future. I’m contemplating a trip to St Croix with family to swim in the St Croix Coral Reef Swim on Nov 5.

Chris Zeoli, right, of the Middlebury (VT) Muffintops after finishing the 10K in 3:04:52.

The post The Joy of Swimming-in-Synch with my Daughter appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 25, 2017

What’s your favorite stroke? All of them!

I imagine that the vast majority of TI enthusiasts swim only, or mainly freestyle. In this post, I make the case for becoming a well-rounded, even complete, swimmer.

I’ve been a distance swimmer since the summer of 1964 when—at 13 years of age–I earned the Red Cross 50-Mile Swim badge by swimming a mile every day. Today, at age 66, if someone was to ask my athletic identity, I’d say “distance swimmer.” Distance swimmers, by custom, swim mostly—if not entirely–freestyle.

Yet my proudest accomplishment in a lifetime of competitive swimming came at age 60 when I won medals in all four strokes, at Masters Nationals. My medal-winning races were the 1000 and 500 freestyles, 200 butterfly, 200 breaststroke, and 400 individual medley—100 yards each of butterfly, backstroke, breaststroke and freestyle.

That accomplishment would have been inconceivable to me 40 years earlier, in college, when I swam my fastest times. My training consisted almost exclusively of freestyle, and I raced in other strokes exactly twice in four years, when my coach entered me in individual medley races, despite not having done a lick of training in other strokes.

Following college, I coached for 20 years with great distinction in all strokes and distances, but—when I swam—did almost exclusively freestyle, simply out of habit. At age 37, I joined Masters Swimming and resumed swimming distance freestyle events, certain that they offered the best chance of success—and that I lacked the inborn talent to swim well in other strokes.

It wasn’t until my early 50s that I decided to get serious about mastering the ‘different’ strokes. I discovered that I thoroughly enjoyed the new learning challenges and variety they offered. It never occurred to me that I might win national championship medals in them. Ever since they’ve been a mainstay in my practice. I’ve since come to believe it’s not a coincidence that I enjoyed my greatest success in distance freestyle and open water competition since becoming a more well-rounded swimmer.

Why Swim Different Strokes?

Let me answer a question that occurs to many triathletes and fitness swimmers: “How will learning other strokes help me if I swim only freestyle events—or swim purely for fitness?”

Too much of anything often leads to staleness. My freestyle is stronger when I do just enough, and avoid too much. Swimming other strokes can give my freestyle muscles a form of ‘active’ recovery. Alternating strokes allows me to swim crisper, faster freestyle with less fatigue. I never go through the motions on my different-strokes ‘resting’ laps. I use the opportunity to hone technique.

Practicing all strokes creates the opportunity for more training adaptations. Once the body gets accustomed to any workload, the opportunity for adaptation or growth diminishes. The more varied a training program, the more potential for growth or improvement. Swimming is unique among movement sports in offering four truly distinct styles. Asked to swim a new stroke, the body’s response is “This is a new task. I’d better attack it with vigor.” A triathlete and recent convert to all-strokes practice described it this way: “I realized that swimming only freestyle, it’s like running or biking the same loop every day—you eventually do it on autopilot. Swimming new strokes is like setting out on a brand new course.” Your body learns to adapt to different demands.

The highest-quality fitness programs use as many muscle groups as possible. Freestyle swimming uses one set of muscles. Other strokes activate other muscles—or the same ones in different ways. Swimming a medley of strokes also minimizes potential for overuse injuries. Using multiple movement patterns reduces the potential for repetitive overwork in any one movement.

All-stroke swimming is more beneficial aerobically. Even EZ-Fly, the style we teach, elevates your heart rate more than an equivalent effort in freestyle, because it’s harder to bring both arms out of the water at once. When you mix fly with other strokes, you’ll be pleasantly surprised at your ability to swim that more demanding stroke longer.

My motivation has been greatest since I introduced more stroke variety. I can devise a much wider variety of challenging skill exercises and set many more personal improvement goals. I sometimes set aside several weeks to see how much I can improve backstroke or another stroke. When focusing intently that way, I always make significant progress—at least 5 percent–in just a few weeks. Because my improvement potential in other strokes remains relatively untapped, personal achievements occur with greater frequency. This refreshes me, both physically and mentally.

The key to these benefits is that I never swim on autopilot. I aim to swim all strokes, at all times, with the best possible form in a specific aspect of technique. The better my interaction with the water in any form, the more I learn about aquatic fluency and economy in a universal sense. And that has kept my freestyle learning curve fairly steep, even after 50+ years.

London 2012 Olympic Champion Dana Vollmer takes a ‘Sneaky Breath.’

Immediately after that Masters Nationals in 2011, I drove from Phoenix, the site of the meet, to Flagstaff Arizona, for a brief visit. While there, I joined a local Masters group for practice one evening. The main set was a series of 200 individual medley repeats in a 50-meter pool. Though I was swimming at the unaccustomed altitude of 7600’ I swam strongly throughout the set. At the conclusion of the set, the coach asked me, “What’s your favorite stroke?” Without hesitation, I replied, “All of them!”

Butterfly Sneaky Breath as performed by 66 y.o. TI Founder Terry Laughlin

At that moment, I realized I’d attained that transcendent state in which all four strokes felt so good that I could experience ‘flow’ while swimming any of them. At age 60, after nearly 50 years, I was truly a complete swimmer.

Want to transform yourself into a Complete Swimmer? Our new downloadable Self-Coaching Courses for Butterfly, Backstroke, and Breaststroke are the most convenient way.

The post What’s your favorite stroke? All of them! appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 23, 2017

Why I Relish Timing My Swims—even as they get slower and slower and . . .

In a post published last January I expressed surprise that athletes who had completed several triathlons—in which they know, to the second, their split times for each leg, swim/cycle/run—did not know their pace for a 100 yard or meter timed swim.This information emerged from a pre-camp survey of participants in our open water camp in the Virgin Islands.

I thought of this yesterday as I was doing a timed set of 200-meter repeats in the 50-meter Ulster County Pool in New Paltz. My favorite swimming venue is open water. Close behind that is swimming in a 50-meter outdoor pool in the morning. I hope to do one or the other every day from now until Labor Day, Monday Sept 4, when Lake Minnewaska and the county pool will close for the season.

When swimming in the 50-meter county pool I always measure something—SPL (strokes per length), Tempo, or Time. And I often monitor two of those measures at once. Partly because measuring (by time) is a habit formed nearly 50 years ago when I was a freshman on the St. John’s University swim team . But even more, at this moment, because the rigor of a timed swim brings an enhanced sense of purpose and accomplishment to my practices. It also maintains my identity as a goal-oriented, improvement-minded athlete as I battle a debilitating disease.

My swim times may have slowed far more in the past two years than in the previous 48, yet they represent just as much my best, most exacting effort as any times I did 10 years ago when I reached my lifetime (age-adjusted) performance peak. And thus I am equally excited by them.

Here’s what I did yesterday. Following an untimed 300-meter warmup/tuneup swim at an average of 42 SPL, I swam 5 x 200 on an interval of 7 minutes. I counted strokes on every length and timed each 200. My intention was to swim progressively faster throughout, while minimizing increase in SPL. I breathed mostly bilaterally, every 3 strokes throughout the set, as a way of testing my ability to minimize breathlessness due to anemia.

I started with a featherlight touch, lightly dragging my fingertips over the surface on recovery and kicking as little as possible. I averaged 43 SPL and my time was 5:00. My TI-RPE (rate of perceived exertion) was 1.5 to 2 on a scale of 5.

TI-RPE-Scale

It may have been the slowest 200 meters I’ve ever swum. That didn’t matter. All that mattered was that it measured what I was capable of at this very moment at that effort level. And I intended to swim faster on each 200 that followed.

On the next 200, I slightly increased the firmness of my catch-and-press. My SPL held at an average of 43. My RPE rose slightly to 2. My time improved to 4:45—which reflected as much that I was finding a groove, as any increase in effort.

On the third 200, I maintained the same degree of firmness in catch-and-press, and increased the energy in my hip ‘nudge’ which drives the stroke. My SPL held again at 43 and RPE at 2. My time improved to 4:42.

On the fourth 200, I slightly increased firmness in catch-and-press while keeping the same energy level in my hip action. My SPL increased to 44. RPE rose to 2.5. Time improved to 4:40.

On the fifth 200, I increased stroke rate, while keeping catch-and-press and hip energy as before, but I increased the energy and firmness in my 2BK. On the final 50, I raised everything to max. My SPL increased to 45. My RPE went to 3.5 and my time dropped 10 seconds to 4:30. Though it was slower than the easiest 200 I could possibly have swum two years ago, I was thrilled to see those digits on my watch.

Start Where You Are

I learned years ago the wisdom of erecting a ‘fire wall’ between times I may have swum years ago, and those I swim today. Or even times I may have swum a month or two ago and those I swim today. Because whatever time I swim today is what I’m capable of at this moment. I know, because it’s such a strong habit to practice with purpose and focus, because I am never complacent, and never always give a quality effort.

I start today’s set where I am today. And then—as I did yesterday—I strive to improve upon it over the rest of practice with all the cunning of which I’m capable.

May your laps be as happy, and purposeful, as mine!

Related: Should You Quantify Performance?

Want to learn more about how to combine multiple measures of capability, efficiency, and performance—like SPL, RPE, Tempo, and Time? Learn from Lesson 4 in our 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course.

The post Why I Relish Timing My Swims—even as they get slower and slower and . . . appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers