Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 14

February 16, 2017

Triathlon/Endurance Radio: One Week; Two Podcasts

We usually try to give you a good weekend read. This week, it’s a good listen–or two. In late January, I was interviewed by two podcast hosts. Eric Schwartz of the Triathlon Training Podcast and Rich Soares of the Mile High Endurance Podcast. Coincidentally during the same week.

On MHE, the TI segment begins at the 14:30 mark. Rich and his two co-hosts, Bill Plock and Khem Suthiwan, talk about their respective familiarity, exposure and impressions of TI for 3+minutes before the actual interview begins at around 18:00. This podcast includes some personal history–how I got started and how I achieved certain milestones like my first Manhattan Island Marathon.

Then Rich asks me about some specific takeaways he got from reading the TI book, which gave me the opportunity to talk about how our analysis and instruction have changed since I wrote that over 20 years ago. (And to note that I’m currently engaged in writing the 2.0 version of that best-selling book.) What are the ‘rules’ for swimming faster? What is the TI way of accessing swimming power? Parallels between TI and Chi Running. (Look for a series of video conversations between me and Danny Dreyer, beginning in March.) From 1:20 to 1:25 Rich was joined by his co-hosts (who didn’t sit in on our interview) for a review. It was fascinating to hear the evolution of Bill and Khem’s views of TI before listening to the podcast and after. And enormously flattering to hear Bill, at one point, compare me to one of my all-time personal heroes–John Wooden, the ‘Wizard of Westwood.’

Eric Schwartz, the host of Triathlon Training Podcast

The Triathlon Training Podcast is hosted by Eric Schwartz of EnduranceOne Coaching in Los Angeles. We covered in-depth history of TI’s early years (like how I paid the bills when TI was still a hobby, not a business) before getting into a discussion of TI methodology. I told Eric at the conclusion of our conversation that it had been one of my all-time favorite interviews because of how deftly he guided the conversation. Eric regularly paused our conversation to probe deeper on a topic–asking great questions–then seamlessly returned us to where we’d left off.

Post-Script: Do You Have Magazine/Periodical Experience?

It’s been my dream for many years to launch a Total Immersion Magazine. Obviously this would be a magazine for swimming–but unlike any that has ever existed. The mission of TI Magazine would be to cover swimming as a lifestyle, rather than as a sport. If you want to read the results of the NCAA or Olympic–or even US Masters–Championships, or training programs or athlete profiles, there are plenty of publications–in print or on-line–where you can do that.

On the other hand, if you’re more interested in the latest and most enlightened thinking on swimming for health, happiness, self-realization–for life–I’ve never seen a magazine whose mission is to cover that. TI Magazine will be that publication.

This month I’ve been galvanized to stop wishing, and begin acting on that dream. It’s remarkable how quickly my vision became much more clear as soon as I got serious with myself about making it happen.

If you have magazine or periodical experience, in print or on-line, on the editorial or business side, and share our vision that the swimming world will be a better place with a swimming lifestyle publication, I’d love to talk with you. Please message me at terryswim@gmail.com

The post Triathlon/Endurance Radio: One Week; Two Podcasts appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 10, 2017

How to get better at things you care about: Practice in your Learning Zone

The most important new insight for me from this talk is the importance of organizing your efforts into Learning Zone and Performance Zone activities. In the Learning Zone, you try to stay on the edge of discomfort, working at skills that are difficult to perform at the moment. How would this work in TI practice?

Suppose you’ve been working on some skill challenges that are still elusive. Two good examples include (i) Holding Your Place with the lead hand–or maintaining a Patient Lead Hand–until the other hand is about to enter the Mail Slot; and (ii) keeping your stroke count in the lower half of your Green Zone

Maybe you manage to succeed at them occasionally, or in just the right circumstances–for instance only at tempos of 1.2 sec and slower, carefully controlled effort, and for repeat distances of 100y/m or less. But when you try to increase the distance or swim a little faster, you fall short. Or perhaps you can do it during solo practice, but not during training sessions with a group–a Masters team or tri club. In Emily’s case she is adding an extra challenge–doing so in a group practice environment, rather than solo practice. I think that’s good.

What I’ve described–solo practice under controlled conditions–is a Learning Zone. In this zone, the stakes are fairly low–mainly falling short of what you’re aiming to do. If you fall a just slightly short–just enough to feel success is just a matter of time–that’s good. It means you’ve got the skills-challenge balance right. If you fall hopelessly short, you need to rebalance the challenge of what you’re trying to better match your current skill level.

In Performance Zone activities, you stay within your comfort zone–i.e. performing these skills a bit less rigorously. If you swim a time trial, a more speed-oriented set, or train with a Masters group the stakes–how well you measure up to others, or to previous speed standards–are higher.

The key is to spend most of your time in the Learning Zone, then apply what you’ve learned there during brief ventures into the Performance Zone.

Unless you are purely oriented to quality of experience, or lifelong learning as a swimmer, which many are. Then it can all be Learning Zone.

Personally I’ve had periods of up to 10 years–early 40s through early 50s–when I was quite satisfied to remain in Learning Zone. This prepared me for some pretty exciting swims–national championships and national records–when I ventured back into the Performance Zone at age 55.

The post How to get better at things you care about: Practice in your Learning Zone appeared first on Total Immersion.

February 3, 2017

Super-Aging Part II: Is there an optimal mindset (and higher purpose) for swimming faster?

Today’s post was inspired by two things:

A book I read 25 years ago Zen in the Art of Archery by German philosophy professor Eugen Herrigel. The book’s main message is captured in this sentence: “A zen archer practices not to shoot bullseyes, but to achieve greater self-knowledge.” That was my first glimpse of a higher purpose for the swimming-improvement process TI had recently begun teaching.

2 An email from Liz Bippart, following our Open Water Camp at St. John USVI in early January. Liz read this post in which I explained that the starting point for improving performance in longer distance events is to know your time for a fairly short distance—100 yards or meters.

In reading surveys completed by those attending that open water camp, I was surprised that 75% reported that they had participated in a triathlon or open water swim, yet fewer than 50% knew their time for 100y/m. This struck me as backwards. In her email Liz asked what motivated ‘average’ swimmers to do the sort of rigorous measurement of their swimming that I detailed in describing the varied ways I time 100 yards—different stroke counts, different tempos, different levels of effort, and with more or fewer repeats.

So I’m devoting this post to exploring where intrinsic motivation to go beyond the routine comes from. It turns out to have surprising overlap with why zen archers practice.

Let’s start with examining the two categories into which all tasks or problem-solving exercises fall—algorithmic and heuristic.

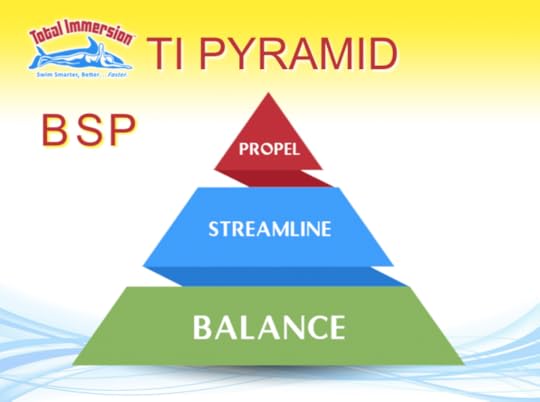

Algorithmic tasks follow a set of standardized steps (i.e. an algorithm) to a predictable outcome or solution. A great example is the algorithm Total Immersion has created for learning highly efficient technique in any stroke. If you follow our proven skill-building sequence of BalanceàStreamlineàPropulsion, you can enjoy a high degree of confidence in becoming dramatically more efficient. Success at this and other algorithmic tasks is dependent on focus, patience and discipline. You cultivate these qualities in learning and integrating the sequence of mini-skills that lead to a high-efficiency stroke.

Heuristic tasks require you to experiment with a range of possibilities and come up with a novel solution. A great example of this is the shift in process that occurs when you work toward achieving a best time in a distance from 100 yards to 1500 meters or more. Total Immersion gets you started with an established step—swim in your Green Zone range of efficient stroke counts. But then you can pursue many possibilities involving elements such as distance, tempo, rest interval and effort level.

It’s inevitable that some of your experiments in combining these elements will produce less effective outcomes. But even ‘unsuccessful’ experiments can produce a valuable learning experience by improving your ability to evaluate different possibilities.

But the most important outcome isn’t the time or place you achieve through your training. Those who pursue only passing or extrinsic rewards may be tempted to seek shortcuts. In contrast, when your practice itself deepens self-knowledge, brings pleasure and satisfaction, and produces a feeling of using all your faculties a their highest level, it becomes unimaginable to seek shortcuts.

It’s typically an extrinsic goal—such as improving your time for 1500 meters, or gaining a higher place in a competition—that gets you started. But soon the sense of engagement and purpose you experience makes practice its own reward. While you have a satisfying sense of achievement from a best time or a ‘podium’ finish in your age group at an open water swim or triathlon, a few hours later the glow fades and a day or two later you return to the pool inspired by the possibility of experiencing the elevated state—sometimes called ‘Flow’– that occurs as you master the varied skills that produced that outcome.

I’ll outline those skills in my next post. Here I want to focus on the three ingredients to practice that produce a Flow state—Autonomy, the desire to be self-directed and in control of your own destiny; Mastery, the drive to keep improving at something that’s important to us; and Purpose, the sense that what we do produces something transcendent or meaningful beyond the immediate moment or goal.

Autonomy From our start in 1989, TI has worked mainly with late-starting, self-coached swimmers. It has been a point of pride for us that TI swimmers are equipped with the most advanced and essential knowledge and skills needed to coach themselves effectively. In the spirit of Kaizen, our process for transferring that knowledge to you has improved continuously—whether you learned from one of our Certified Coaches or through our downloadable Self-Coaching Courses. Algorithmic tasks provide a straighter and narrower path for developing that sense of Autonomy, or self-reliance. Heuristic tasks deepen it. Pursuing a better swim time—the smart and logical way we teach–is a great way to enhance the sense of Autonomy you began developing by learning TI technique.

Mastery Mastery begins with Flow–heightened experiences that occur when we tackle challenges that require us to stretch to the very limit of our current abilities. In a flow state, you can become so deeply engaged that your sense of time, place, and ego melt away. The difference between the two is time scale. Flow happens initially occurs in a moment. With practice it can stretch to most of an hour-long practice. In contrast, mastery develops over months, years, and decades.

Mastery follows three principles:

Mastery is a mindset in which you view your abilities not as fixed or finite, but as infinitely improvable (Kaizen). You place a higher value on learning goals over performance goals and embrace difficulty and effort as a way to improve at something that matters.

Mastery demands effort, grit, and deliberate practice. As enjoyable as flow is, the path to mastery is a challenging process over a long period of time.

Mastery is a moving target: You never really feel you’ve achieved it. If a skill is infinitely improveable, how we can we ever say “That’s it. I’ve arrived. I’m now a Master.”

Purpose The third ingredient is purpose, which provides a context for its two mates. Purpose creates a sense that you’re working for a cause greater and more enduring than the immediate goal or present moment. Like those zen archers who practice for greater self-knowledge, what’s your higher purpose?

In traditional swimming, you swim faster by working harder and stroking faster. In TI World, you recognize that swimming faster requires you to solve complex and deeply interesting problems. Such problems reward an inquiring mind and the willingness to experiment with many combinations of stroke count and tempo leading to an original, completely personal solution.

Later this month, I’ll provide examples and details on how to do this.

The post Super-Aging Part II: Is there an optimal mindset (and higher purpose) for swimming faster? appeared first on Total Immersion.

January 20, 2017

Swim for Health and Vitality: Swimming as ‘Moving Meditation’

In 2006 I swam in the 3K open water event of the FINA Masters World Championship. Held in San Francisco Bay, it was the most interesting event I’d ever swum, because it exposed the field of several hundred swimmers to three distinct settings, each presenting different challenges and opportunities.

We were sent off in waves five minutes apart. I started with the seventh wave–men in their 50s. In the first kilometer, we swam across a calm, sheltered bay. The main choice presented was how far to dolphin off the bottom before beginning to swim, as the course was quite shallow for the first 50 meters. My own approach was informed by watching earlier heats to observe how the lead swimmers handled this.

In the middle section, we entered a narrow channel, 800-meters long, lined with boats tethered to the walls. I’d swum the course a day earlier to familiarize myself and had made a plan to navigate by breathing bilaterally, keeping the channel walls equidistant. This minimized the need to lift my head and look forward.

As we approached the outlet of the channel into the main body of San Francisco Bay, there was a car-tire breakwater. Still breathing bilaterally and looking forward only infrequently, I could feel large swells. This alerted me that we’d encounter strong winds and rough seas beyond the breakwater.

From my reconnaissance swim the day before, I knew the first part of this section followed the curve of the island for approximately 200 meters before striking out across the bay straight to the finish. After passing the breakwater, I took one look forward and could see only a wall of green water. I decided to navigate this curving section of the course by breathing only to the left, keeping the shore at a constant distance.

TI Coach Shinji Takeuchi was positioned at the breakwater with a video camera. He picked me up as I passed the breakwater and walked the shoreline for several minutes, tracking me and a dozen or so swimmers. What I saw when I viewed the video later was striking.

Everyone around me flailed their arms and whipped their heads around in response to the rough water. Many looked forward virtually every stroke. Their forward peeks provided no useful information, yet they kept doing it time after time. In contrast, I stroked with control and breathed repeatedly to my left, smoothly navigating through the pack without ever looking forward.

This video provides an example of mindfulness vs. mindlessness in challenging conditions. Swimmers who picked up their heads weren’t acting rationally, as they never changed their tactic despite seeing nothing of value. Overcome by their circumstances they reacted by reflex.

From Distraction to a Powerful Tool

This leads to a definition of Mindfulness: The ability to control and direct your thinking, transforming your thoughts from a distraction to a powerful tool, particularly in a demanding or stressful situation, such as we commonly face in open water. In each section of that race, I faced conditions that offered opportunity or challenge. Being mindful allowed me to calmly assess each situation and respond with a strategy to optimize an opportunity, or minimize a challenge. It also helped me win a World Championship medal.

The great majority in any open water event practice mainly in pools, where conditions are predictable and little-changing. Our challenge—or opportunity—is to use pool training to lay a foundation for the ability to be observant-and-opportunistic in the unpredictable conditions we face in open water.

Though I didn’t practice formal meditation until recently, I discovered mindfulness through swimming—though it wouldn’t have occurred to me to call it that at the time. From 1964 to 1988, I’d swum much as other competitive swimmers—active and retired—did, focused mainly on ‘getting in the yardage.’ But in 1988 an innovative coach named Bill Boomer taught me a balance drill that lifted my formerly-heavy hips and legs to the surface.

It was such a novel and welcome sensation that I wanted to make it permanent. This required me to focus on aligning my head and spine and to extend my hand at a slight downward angle. As those thoughts were completely new, I had an inkling that I’d return to old habits if I didn’t focus on these new sensations on every lap.

How I Learned to Be Mindful

I thought of them, and almost nothing else, for six months before it felt ‘safe’ to turn my attention to another thought without losing the still-fragile sensation of ‘weightlessness.’ That new thought was to use my arm to lengthen my bodyline, more than push back, and keep it long between strokes. That became another six-month project.

It also set me on a path I remain on to this day:

Start every practice (pool and open water) with an intention to improve my swimming, and a plan to produce that result.

Start every length, repeat, and set with a mental blueprint of a mini-skill I will try to perform better than I ever have in my life.

Take every stroke with keen awareness: What sensation will tell me I’m accomplishing my skill goal?

In the summer of 1989, nine months after my life-changing balance lesson with Bill Boomer, I held the first Total Immersion camp, and began teaching my new way of practicing to others. I did so fully aware that acquiring the ability to maintain focus on a single thought would be even more challenging than, say, aligning the head and spine. New habits are difficult to form; old habits even harder to break.

We swimmers face a unique challenge to mindfulness: Everything in swimming’s ‘training culture’ encourages autopilot–rather than mindful–thinking. Follow the black line . . . Get to the other end . . . Long sets of rote repetition that we just get through . . . The ‘hamster on a wheel’ (chased by several other hamsters) feeling of group training.

The Fundamental Skill of Change and Growth

That told me we had to emphasize to our students that mindfulness—the ability to stay focused on one chosen thought—would be the fundamental skill of change, improvement, and growth. It would also be vulnerable to the mainly-physical emphasis of the environment to which they’d return.

But we soon received enthusiastic feedback from those to whom we’d taught this practice habit:

Being mindful played as large a role as newly pleasurable physical sensations in their becoming passionate about swimming.

Practice had become its own reward; they’d finish one practice looking forward to the next.

Applying mindfulness to swimming reminded them of other forms of practice—music, dance, aikido . . . surgery. It also helped relieve stresses encountered outside the pool.

Over the intervening 25 years, mindfulness has become a core value of Total Immersion, and our applications of it in TI learning and training methods have steadily become more robust. When we began organizing open water ‘learning vacations’ 15 years ago, it was natural to make mindfulness a centerpiece.

At the beginning of each open water clinic or camp, we tell our students: Pool swimming is predictable and controllable; open water is unpredictable and—sometimes—difficult to control. The most important thing we’ll teach you here is how to think when the unpredictable happens—as it almost certainly will.

Habits I began developing while trying to align head and spine in the pool converted easily and naturally into essential tools for adapting to the many things one encounters in open water that are impossible to prepare for in the pool–wide open and ill-defined spaces; pack swimming and physical contact; very great distances; conditions of all sorts from chop and swells to changing wind direction to bone-chilling temperatures.

And the moving meditation that has made pool practice its own reward, for me and countless others, has also enabled us to transform any open water swim—from a 3K race to an 18K swim across Gibraltar Strait—into an art form, or a kind of game.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: Swimming as ‘Moving Meditation’ appeared first on Total Immersion.

January 13, 2017

Swim for Health and Vitality: How to Become a ‘Super-ager’

I’d like to recommend the article How to Become a ‘Super-ager’ which was published Dec 31, in the NY Times. I’ve read several articles on this topic. This was one of the better ones because it’s succinct and pretty clear.

The main argument of the article is captured in this paragraph:

“How do you become a superager? Which activities, if any, will increase your chances of remaining mentally sharp into old age? We’re still studying this question, but our best answer at the moment is: work hard at something. Many labs have observed that these critical brain regions increase in activity when people perform difficult tasks, whether the effort is physical or mental. You can therefore help keep these regions thick and healthy through vigorous exercise and bouts of strenuous mental effort. My father-in-law, for example, swims every day and plays tournament bridge.”

It’s terrific that the writer’s father-in-law swims every day and plays tournament bridge. My good friend Bruce Gianniny swims Masters in Rochester NY and has broken the two national age group records I once held. He also has standing bridge and chess games with groups of friends.

I admire Bruce for his ‘brain-teasing’ pursuits and would emulate him if I found a group locally who would bring along a beginner by the hand. I’ve been encouraging my 92 y.o. mom, who hasn’t played bridge in over 40 years, to take it up again to maintain her already impressive mental acuity. The social aspects would be just as valuable as the cognitive demands as elements of a Super-aging program.

However my favorite way of pursuing the Super-aging effect is to work hard at swimming. But, the TI way of working hard at swimming is different than for most people.

It’s not about coming to the wall huffing and puffing, with muscles aching, after a set of repeats or dragging into the shower after pushing to your physical limits for an hour or so.

And it’s not that I entirely avoid high level physical exertion; I do occasionally explore the limits of my physical capability, as I described in last month’s post How to Be Kaizen While Swimming Slower Than Ever.

It’s that the one constant of my practice is that there’s always at least one set in which I combine a very demanding level of skill and cognitive difficulty. You see, synthesizing physical and mental demands in a single activity is far more valuable than doing two activities, one in which you work physically and a separate one in which you sit quietly and work your brain.

How so?

Researchers say the brain works best during, or immediately following, exercise because it gets a rich supply of oxygen and glycogen, the fuel on which both brain and muscles work.

Brain scientists have a saying “Neurons that fire together wire” When you are focused intently on entering your hand through the Mail Slot, for instance, the motor neurons that do the physical action and the cognitive neurons that carry the intention and visualization that guide you form a more powerful circuit.

Finally, when you are working physically your muscles secrete Neural Growth Factor (NGF), a group of proteins that are the raw material for neurogenesis—the growth of new neurons. These new neurons form new circuits to support the activity you’re doing at the moment—let’s say, honing the timing of your 2-Beat Kick.

Collectively all of this activity is thought to be your best insurance for staying mentally sharp as you age. And you’re maintaining peak physical health at the same time!

If you’re like me, the feelings of happiness, fulfillment, and being fully engaged with life you experience while working on fine points in your stroke–or connecting with a TI swim buddy in a sync-swim–are examples of that rare synthesis of mind and body.

Two other blogs I published in the past month give more examples of swim practices that can help you be a Super-ager.

Better Information and Understanding

As can one of our freestyle Self-Coaching Courses—the 1.0 Effortless Endurance and 2.0 Freestyle Mastery courses.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: How to Become a ‘Super-ager’ appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 30, 2016

A New Year’s Resolution: Better Information and Understanding

Do you feel you have reasonable command of the skills in the TI Effortless Endurance Pyramid (Do you feel balanced and stable in the water? Do you move through the water, more than move it around? Is your stroke smoothly integrated . . . including breathing?) Not perfect, but comfortable and with relatively little energy waste?

If so I’d like to encourage you to make a New Year’s Resolution to develop a better understanding of how you create and improve the pace you can sustain for a longer distance–say 1500m or 1650y. We can’t predict an open water pace, but an improvement in our pool pace for distances such as 400m/500y, 800m or 1000y or 1km, and 1500m/1650y should be reflected in an improvement of the open water paces we can achieve.

There’s a fairly simple baseline for being able to improve performance through more effective (and personally relevant) training. That is to know your time for 100y or 100m.

This blog was prompted by reading the survey responses of those attending this week’s Open Water Experience at Concordia Eco-Resort in St John USVI. I noted that 75% of attendees reported that they had participated in a triathlon or open water swim. But fewer than 50% knew their time for 100y or 100m. To me this is a bit like putting the cart before the horse: I’d want to train with information and understanding before venturing into such an event.

Do you know your time for 100y or 100m? Even if you have no plans to swim in an organized event, this info can be invaluable to Mastery and Kaizen aspirations.

To be clear, I’m not talking about what your time would be for a single all-out time trial for 100y or 100m. I’m referring to the time you record at a relatively relaxed pace. A pace you could repeat 3 to 5 times, resting less than a minute between trials.

So let me suggest several ways of recording a time for 100y/m.

Time + Tempo: Time yourself at several tempos within your Tempo Comfort Range (This requires a Tempo Trainer, which I would suggest you make standard training equipment in 2017, if it’s not already.) At the moment, I’m working in a range of tempos a bit faster and slower than my calculated tempo of 1.1 sec from my 1650y race on Dec. 11. You might compare times at tempos across a range like this 1.1, 1.15, 1.2, 1.25, 1.3. Your time should be faster when tempo is faster.

Time + SPL: Time yourself at, say, 3 different stroke counts. At the moment, I am familiar with my 100y times at 15, 16, and 17 SPL. At 15 SPL, I can swim 3 to 5 x 100y repeats in about 1:35. At 16 SPL, I can hold a pace of about 1:32, At 17 SPL, I can hold a pace of about 1:29. In other words, time should improve as SPL goes up. I will look to improve each of these paces over the next few months. As I do, I’ll have great confidence that my 1650 pace/100 will improve similarly. I.E. 2 sec improvement in my 100y paces (at any of these stroke counts) should result in about 30 sec improvement in my 1500m/1650y time.

Time + RPE: RPE is an acronym for Rate of Perceived Exertion–a fairly accurate self-assessment of how hard we’re working. (It gets far more accurate with practice.) In TI we have a 5-point RPE. RPE1 = Perfect (the effort at which you can swim your most perfect form). RPE2 = Cruise. RPE3 = Brisk. RPE-4 = Race (how you’d want to feel, at say, the 1KM mark of a 1500m swim, RPE-5 = Race+ (how you’d want to feel in a final 50m sprint to the finish line of a 1500m race). Virtually all of my training these days is between RPE1 and RPE3 (Even my race pace at, say, 1000y of a 1650y swim would be pretty relaxed.). There’s a natural overlap as well between RPE, SPL and Tempo. I.E. At RPE-3 I’m likely to be swimming at a tempo of around 1.15 and SPL of 16.

What’s your 100y/m time when you are swimming at Warmup/Recovery/Perfect pace — the most relaxed you can swim? How much faster is your 100y/m time when swimming at RPE-2 Cruise (just a bit faster than perfect–like conversational running pace)? How much more do you gain when raising your effort to RPE-3 Brisk (still well short of max effort) pace? The more time improvement you make with each step-up in RPE the better.

And the most important pacing skill of all is to minimize time lost with each reduction in Tempo, SPL and RPE

With information like this you’ll get more engagement, enjoyment, and productivity from your training in 2017.

For more info on this approach to training, see Lesson 4 Pace Mastery in the TI 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course.

May your laps be as happy–and effective–as mine in 2017

The post A New Year’s Resolution: Better Information and Understanding appeared first on Total Immersion.

Year End Blog

Today I feel dramatically different. Though the cancer, and its effects, have progressed considerably, I’m fully recovered from the effects of the stroke and I wake early every morning excited and with a sense of high purpose about the potential of the day ahead to focus on family, work and swimming. I continue to have galvanizing goals for my swimming and I’m happy to say I experience relatively little anxiety or depression, compared to how I felt in the initial stages.

I’m really looking forward to going to St John for our annual OW camp. I leave in less than two weeks. After I return, I’ll be home for a week for treatment, then go to Barcelona and Alicante Spain for two weeks. Barcelona for three days, simply because I really want to visit. Alicante for 10 days for three coach training courses with some time off between them.

The post Year End Blog appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 23, 2016

Swim For Health and Vitality: Try Something New (and impediments to doing so)

Amby Burfoot sent a comment after reading my recent post How to be Kaizen while swimming slower than ever. “I admire how you remain open to trying new things after decades of the same old, same old.” This is partly correct. I did the same old for 25 years from 1965 to about 1990, but shortly after starting TI I began experimenting and was so thrilled by the discoveries I’ve made it’s become a deeply ingrained habit.

In that post, I contrasted the far greater number of occasions for error or inefficiency in swimming with those in running. Given the almost limitless opportunity to fix and improve stuff in your swim, why are so few people inclined to pursue change in–or critically examine–their swimming. The dual culprits in this are the nearly universal inclination to view swimming as mostly an aerobic activity–like running–and the unfortunate tendency of most folk to fall into autopilot mode while ‘following the black line.’ (This phrase is oft cited by those who complain that swimming is boring.)

In group practice–i.e. Masters–an additional impediment to noticing/examining/fixing is the feeling of being on a hamster wheel–in a group chase with three or four other hamsters. Until a month ago I hadn’t swum with the local Masters group in nine years. But since I resumed–partly to prod myself to swim more often, partly for the social aspect–I’ve found value in the great discipline it requires to maintain a personal and purposeful focus.

A typical skill that has served as a prod to this kind of focus (and the new thing on which Amby commented) is the new way of breaking out from a push off, with which I’ve been experimenting the last two weeks. As I wrote in my last blog, while watching video of Lou Tharp during a 1650 race we both swam on Dec 11, I noticed that he traveled a long way on his pushoffs. (I counted laps for him, but was too busy with that to notice then.) Though Lou is a left-breather, he took his first stroke and breath to the right on each push off, then began breathing left on his very next stroke.

When I first tried it I noticed a tendency to drift left, a couple of times brushing the lane line on that side. Like every other worthwhile skill, it requires practice to refine and imprint. For those of you curious to try it, I asked Masters Coach Matt Kessler to shoot a clip of me doing this last night. Notice the two consecutive breaths after each push off. On that second breath I have to be very conscious of using my right hand and arm to maintain direction.

What’s been the effect of this new push off on my practice performance? Well. on Dec 11 in my 1650 race my average pace and total strokes per 100y was 1:35.5 and 70 strokes. Last night in practice, during Mat’s main set of 5 rounds of 5 x 100 on 1:45, I averaged 1:32 to 1:33 at 64 strokes.

And this shows one of the values I derive from swimming a race. Besides testing my strength of focus, I can also collect data on my performance and use that to set mathematically specific improvement goals. I call this an Improvement Project. (In the past I’ve gotten data of similar quality from a time trial performed during practice. Besides my time I need one other metric–tempo or stroke count–to create my data set.)

I hope to swim another 1650–two if possible–between Feb and May. My goal is to shave a minute or more off my latest time (and Adirondack 65-69 record). I’ll need to hold a pace of about 1:30 per 100y to do so. I’ll be highly confident in my ability to do that if I can swim sets of 100 to 200y repeats in that pace or faster, taking fewer strokes, or at a slower tempo, than I project for the race.

I expect my new breakout and first stroke to be one of the skills that help me attain that goal.

The post Swim For Health and Vitality: Try Something New (and impediments to doing so) appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 16, 2016

Swim for Health and Vitality: How to be Kaizen while swimming slower than ever

Last month, in the blog Cancer as Opportunity, I related examples of how I’ve used instances of illness or injury to become a better swimmer. In the instances I described, the cited condition had put a significant dent in my speed and stamina and/or greatly limited my ability to train. Aging has the same effect. Illness or injury simply speeds up that process greatly—if temporarily.

When that has occurred, I viewed the situation as an opportunity to take a problem-solving approach, replacing physical capacity with a higher level of skill, something that prepares me for the losses that come with aging.

I wrote that I would be swimming a 1650y freestyle race on Dec 11, an event in which I swam my lifetime best of 18:02 at age 20. At age 55, I swam it in 19:50, adding only 1 min 48 sec from what I’d done 35 years earlier.

But my decline has become far more precipitous since, especially in the year since my cancer diagnosis. Last March, I swam the 1650 in 23:10. Though it was a ‘lifetime slowest’ I considered it the best swim of my life, all things considered. I described that swim in the blog 1390 Seconds of Unwavering Focus.

In that lifetime best/lifetime slowest swim, I added 3 min 20 sec, far more in nine years than I’d added in the previous 35 years.

Last Sunday I had another swim in which I take great pride, finishing in 25:57.6, remarkably close to what I’d estimated I could do, demonstrating how well I know myself.

Though I added just under 3 min in the past nine months, I’m enormously proud of this swim because of how I performed in challenging circumstances. After only 600 yards—with 42 laps (and flip turns) to go–I was already feeling quite breathless after each turn. It hurt enough that I considered doing open turns in a race for the first time in 50 years.

Instead I deepened my focus on stroke and turn technique, finding a way to relax slightly more and still maintain my pace. It didn’t hurt any less; I just didn’t have any available bandwidth to focus on discomfort, since I was devoting every brain cell to my stroke and turn form in an effort to maintain my pace.

When I hit the touchpad and saw 25:57 displayed for my lane I allowed myself a little celebration since it was an Adirondack Masters record for the 65-69 age group. And almost immediately I began thinking of how to go faster in the next few months.

In the Cancer as Opportunity post I stated that there are almost limitless opportunities in swimming to improve a performance, with little or no change in fitness. In every practice repeat, there are many mini-skills to hone. Your time for a 1650-yard/1500-meter/mile swim is the product of whether you’ve exploited those opportunities.

I cited breathing and turns as two great examples of areas that can be improved by specific focus. In my 1650 I took about 560 breaths and did 65 flip turns. And the greatest challenge I faced was breathlessness caused by turns!

In the heat immediately following mine, I counted laps for my friend Lou Tharp—he had also counted for me. My daughter Fiona filmed the last few laps of my race and the first few of Lou’s. While watching the video, I noticed that Lou breathed to his right coming out of each turn then breathed immediately to his left on the next stroke, continuing to breathe left the rest of the lap.

By not taking his first breath to the left, he traveled another yard or two coming out of the turn. By breathing on consecutive strokes, he compensated for the breath-holding one must do during a flip turn and pushoff.

I immediately recognized that as a skill I could practice and hone—it’s a great challenge to hold a straight line out of the turn and maintain good form while breathing on your first two strokes. I committed to practicing it until I did it well.

Last night, in just my third practice since seizing on this problem-solving opportunity I swam 3 rounds of 3 x 100 free repeats in an average pace of 1:30 and 60 strokes—five seconds faster and about 6 strokes fewer than I averaged during the race, and a considerable improvement on my training swims before I introduced this tweak to my repeats.

This is one small example of Kaizen. Nearly 50 years after swimming my first 1650, I’m experimenting with a significant change in how I come out of my flip turns on each lap, and seeing it pay off in measurable improvement to my practice.

I believe I can knock another minute off that record in the next few months. I’ll let you know how I do.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: How to be Kaizen while swimming slower than ever appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 14, 2016

Going Beyond Easy Speed

You may have begun your training in a structured, methodical program like TI and made dramatic improvements in your ease and in your speed in those first few months of devoted practice. But then progress seemed to slow down. What happened?

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Going Beyond Easy Speed.

The post Going Beyond Easy Speed appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers