Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 16

October 28, 2016

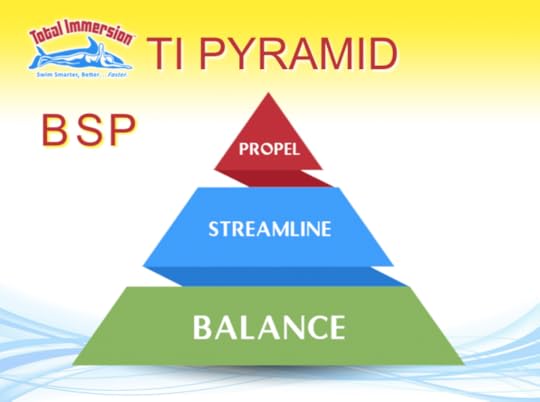

Climb–and Master–the TI Pyramid of Skills

Naval architects observe principles of physics and hydrodynamics in designing a sea-worthy vessel. Nature followed the same principles in the evolution of fish like the barracuda and aquatic mammals like the dolphin.

TI is the only swimming method to observe the same laws and principles in shaping and propelling a human ‘vessel.’ Three decades of experience—and countless thousands of teaching opportunities–have definitively shown that teaching three foundations in this order Balance–>Streamline–>Propel brings better outcomes faster than any other approach.

Balance

Our first goal is to create a balanced vessel, one that can maintain a horizontal, comfortable, low-drag position with a minimum of kicking or heartbeats. We achieve this by cooperating with the natural forces of gravity and buoyancy

A balanced body will rest parallel to—but mostly beneath–the surface with just 5% of body mass above the surface. When the body is balanced that 5% will be distributed all along the body—a ‘slice’ of the head, some upper back, a glimpse of one buttock, then the other.

Since the head, by itself, is 8% of body mass, if most of it is visible above the surface, other body parts must sink. Thus our first Balance mini-skill is to release the head’s weight to rest upon the water. When we do, we should see only a hand-sized slice of the back of the head above the surface. This is true for all strokes.

Another balancing action is to extend the bodyline fully in each stroke—improving water displacement by extend the body over more water-surface area. In freestyle, a third critical Balancing action is to enter early and reach forward at an angle that will put the hand below the bodyline at full extension or Catch.

A balanced and stable vessel allows the swimmer to move the limbs in ways that minimize drag and maximize forward motion, rather than wasting energy fighting gravity. This produces immediate and dramatic energy savings.

Finally, when we are active 90% of the brain’s energy goes maintaining balance—and 90% of that energy goes into correcting imbalance when it occurs. When the brain senses the body is no longer fighting gravity, is no longer in danger of sinking, it calms down–freeing up mental energy and bandwidth for mastering other efficient-swimming skills—like Streamlining.

Lesson 1 of the 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course teaches Balance skills.

Streamline

After establishing a balanced, stable vessel, the swimmer gains the capability to create a shape that moves through the water with a minimum of resistance. The benefits of drag reduction increase as we swim faster since drag goes up as a square of the increase in velocity: 2x faster = 4x more drag. So energy savings from Streamlining can be quite significant—second only to achieving Balance.

Even better, like Balance, actions that improve Streamlining (i) are relatively easy to learn, since they involve mostly whole-body, or larger body part actions, not fine-motor control; and (ii) save far more energy than it takes to execute them.

Three basic Streamlining mini-skills are:

Shape your ‘vessel’ to be as long, sleek, and stable as possible—as in the Freestyle Skate drill.

Lengthen your bodyline—and keep it long for a bit more of each stroke cycle.

Minimize waves, splash (noise), and bubbles as you stroke.

Lesson 3 of the 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course teaches Streamlining skills.

Propulsion

When your vessel is balanced and streamlined, your arms and legs are freed up to contribute far more effectively toward producing locomotion, rather than diverted to controlling body position and stability, or moving water around.

To a large extent, Propulsion improves automatically as a result of improving Balance and Streamline. At least 75% of maximum propulsive efficiency is achieved while you’re not even concentrating on it—simply by liberating arms and legs from correcting body position/shape errors.

The first three mini-skills of Propulsion are:

Put hand and arm in position to trap-and-hold the maximum volume of water, then press on the water with patience, care and sensitivity—not heedless application of force. You learn this in the Skate position.

Calm ‘busy’ legs by achieving Balance, then learn to coordinate a toe-flick on one foot to drive the opposite hand to its Catch position below the bodyline.

Set your rhythm or tempo, and initiate power from your core, rather than in the arms and shoulders.

Lessons 1-2-3 of the 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course teach ‘automatic’ Propulsion skills.

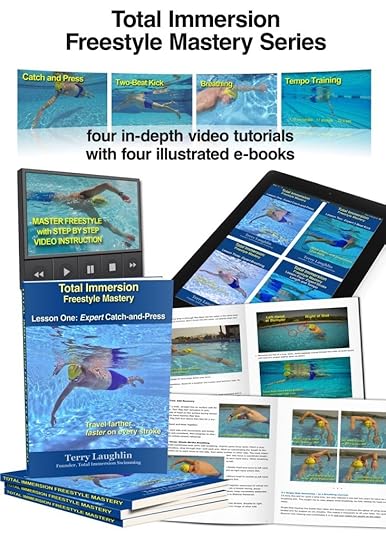

The 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course teaches expert-level Propulsion skills.

The post Climb–and Master–the TI Pyramid of Skills appeared first on Total Immersion.

October 21, 2016

How to Learn Perfect Pace

Last month, in How to Have Amazing Swimmer’s Hands, I wrote about one of my two favorite swimming tools, fist gloves. In this post–which is excerpted from Lesson 4 of the TI 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course, I write about the other.

I’m a minimalist when it comes to swimming equipment. I haven’t used buoys, paddles, kickboards, or fins for 25 years. However, one tool–the Finis Tempo Trainer–has deepened my capacity for mindfulness, yielded priceless insights into my stroke, and taught me to ‘encode’ pacing skills in my nervous system. The Tempo Trainer (hereafter TT) is a small electronic metronome you can tuck under cap or clip to goggles. Here’s why I would even choose the TT over any other timing device, including pace clock or sports watch:

It focuses you. Swimmers often leave one end of the pool thinking only about getting to the other end. The Tempo Trainer–set to beep at a frequency of, say, 1.2 seconds–transforms each lap into a series of 1.2 second intervals. You soon realize that each of those intervals is composed of ‘consequential nanoseconds’ within which you make or break the stroke you’re taking. When you feel a tiny stroke error you know in that instant, it will cost you an extra stroke—and an extra 1.2 seconds—when you reach the other end. You also realize those tiny errors are almost always the result of a moment’s inattention. This is powerful motivation to pay attention.

It improves rhythm. Consistent—even metronomic–rhythm is a central element of success at distance swimming. It’s also the quality that harmonizes all parts of the stroke into a seamless

It teaches unerring pace. Many people believe sense of pace (sometimes called ‘clock in the head’) is a trait you’re either born with or acquire through endless repetition. The TT is a fast and methodical way to learn this critical skill. Just keep SPL (Strokes Per Length) consistent and synchronized to the beep as you continue swimming. If SPL and Tempo both remain steady, so does your pace.

It ‘cracks the code’ on speed. If you save a stroke while maintaining tempo, or increase tempo by a few hundredths of a second while maintaining stroke count, you swim faster. Add a stroke to your count on any length, you go slower. This quickly produces an awareness that any pace is the inevitable product of a particular SPL and Tempo; not of how fast—or hard–you stroke. You also become newly confident that you have control over how fast you swim.

It emphasizes the benefits of training your brain. It’s eye-opening to discover how quickly your brain and nervous system can solve a pace or speed ‘problem’ in a thoughtfully-designed set (examples follow). You often experience striking efficiency gains in as little as 10 or 15 minutes—and make thrilling progress in the course of a week. This demonstrates that you can improve far more quickly when you focus on training the brain and nervous system–as advocated by TI–than when you train limbs, lungs, and muscles as in traditional training.

Swimming with the TT develops a new habit: To focus on repeating high quality strokes at incrementally faster tempos over gradually greater distances. This will produce far more improvement than any other form of training. The TT provides a clear structure, incentives, and rewards for making this an ever more instinctive habit. So strong that, over time you also race that way.

Experienced competitive swimmers can generally begin with a Tempo Setting between 1.0 and 1.10 sec/stroke. Newer swimmers should begin with a setting between 1.20 and 1.40 seconds. In some of the examples below, I use a setting of 1.2 seconds; SPL=Strokes Per Length.

Task #1 Explore Your Stroke

When using the TT, you synchronize the beep with a key body movement present in the stroke—most commonly the hand entry. Swim several 25s, getting accustomed to timing your pushoff to synchronize first hand entry with 4th beep. Adjust tempo to one that feels quite comfortable. For now this is your Tempo Sweet Spot. Then try this set:

Swim 4 rounds of (3 x 25). In Round 1, synchronize beep to hand entries. In Round 2, synchronize to hips movements (we call them hip ‘nudges’). In round 3, synchronize to feet (toe ‘flicks’). In round 4, you have two options: Cycle through one 25 of each; or stay with your favorite.

Did you feel anything new or different as you moved synch point from hands to hips? When you synchronize beep to feet, for an effective 2BK, take note of any foot movements between beeps.

Task #2 Examine your Breathing

Set TT at most comfortable tempo. Swim 4 rounds of (3 x 25) In each round, cycle through: 25 Breathe Right, 25 Breathe Left, 25 Bilateral.

Do you notice any variation in your ability to stay with the beep as you change breathing side or pattern.

Task #3 Constant SPL and Tempo (means constant pace).

Swim 8 x [25 or 50] @ ‘Tempo Sweet Spot.’ Rest 10 beeps between swims. Count strokes per 25 or 50. Your basic goal is to keep focus and SPL constant. If you keep SPL constant, your Pace is teady. A great outcome is to reduce stroke count by end of set. This means your pace has increased—as a result of strong focus leading to improved efficiency. This demonstrates that focus is usually the key to faster swims.

Task #4 Tempo Pyramid

This is my absolute favorite set. It is enormously effective at helping you pinpoint your personal ‘Green Zone’ range of efficient stroke counts. While the TI Green Zone chart (download for free here) is a great starter guide , this exercise (after repeating many times over weeks or months) tells you your best personal range of efficient SPL with complete precision.

Choose your most comfortable tempo from previous tasks as your starting point.

Swim 4 x 25 (or 50), slowing tempo by .06 (i.e. 1.20, 1.26, 1.32, 1.38) on each. Subtract as many strokes as possible while Tempo slows.

Then swim 6 x 25 (or 50) increasing tempo by half the increment–.03 (i.e. 1.35, 1.32, 1.29, 1.26, 1.23, 1.20). Try to maintain lower stroke counts for as many tempo changes as possible.

Remember SPL on #1, lowest SPL (likely on #4), and SPL on #10. How many SPL did you ‘save?’ How many seconds did you save?

Task #5 Hold Pace; Lengthen your Stroke.

Swim a series of timed 50s or 100s. Set initial tempo at 1.2 seconds. Slow tempo by .01 each 100 (i.e. 1.21, 1.22, 1.23, etc.) For how many 100s (and .01 tempo changes) can you maintain your initial pace or time? Each time you slow tempo slightly, you’ll have to lengthen your stroke slightly to keep your time the same.

Task #6 Swim Faster while Maintaining Stroke Length.

Set Tempo at Comfort Zone. Swim a series of 25s. Count strokes. Increase tempo by .01 each 25. (i.e. 1.20, 1.19, 1.18, etc. For how many 25s (and .01 tempo changes) can you hold your initial stroke count? A good goal is to complete 8 x 25 (.07 sec increase in tempo) without adding a stroke to your count. Repeat this set regularly until you can do this.

The Total Immersion 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course teaches ‘Expert’ Pacing/Tempo Training and three other Mastery skills for freestyle. Learn more here.

The post How to Learn Perfect Pace appeared first on Total Immersion.

October 20, 2016

Thinking or Feeling?

The conscious mind is going to stay busy. You can choose, with training, what it stays busy with. Mindfulness is about directing the attention to what maters and keeping it there for intention. You get that ability only by…

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Thinking or Feeling?

The post Thinking or Feeling? appeared first on Total Immersion.

October 7, 2016

Zeroing Out Cancer with Swim Across America

How familiar are you with Swim Across America? Until the last few weeks, I knew little more than that it was involved in fundraising for cancer research. After participating in the SAA-San Francisco on Oct 1, I’m not only far more familiar with the organization and the wonderful work it performs, I’m committing to deeper involvement and support. I’m encouraging TI swimmers and coaches to investigate, and if there is a Swim event near where you live, to consider participating, as a swimmer or volunteer.

Next year will be Swim Across America’s 30th year. In that time, it’s grown from a single event in Nantucket MA to 18 open water swims plus dozens of pool swims across America. It has raised more money for cancer research each year, and is now approaching $70 million total.

Those who swim in a SAA event are always familiar with the effect of their efforts and contributions have because all money raised through SAA events stays local. By swimming in an SAA event you improve the odds for cancer patients—today and tomorrow–in your own city.

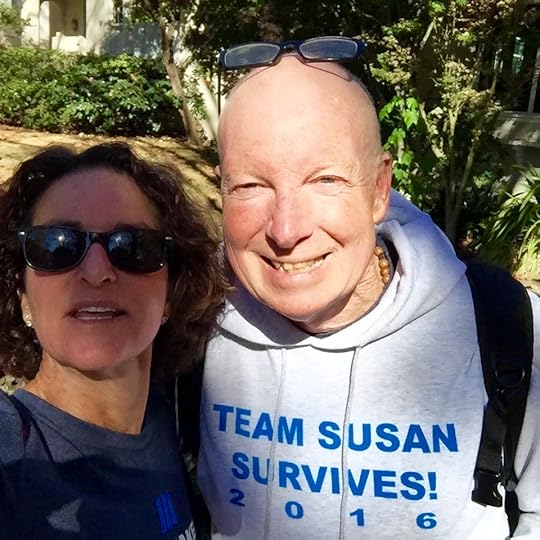

So why did I swim in San Francisco? My close friend Susan Helmrich, lives in Berkeley CA but her mother lives in Woodland Pond, the senior living center in New Paltz where my students 98 year old Dr. Paul Lurie and swimming legend Marilyn Bell DiLascio reside. Susan visits her mother quite frequently. During those visits, a shared interest in swimming has brought her into close contact with Paul and Marilyn. Susan—an avid Masters swimmer–and I meet to share a swim nearly every time she visits.

Susan takes a selfie.

During our years of friendship I learned that Susan was a 3-time cancer survivor, her first bout being a reproductive cancer nearly 40 years ago at age 21, and her most recent neuroendocrine pancreatic cancer in 2009. Each time, swimming was an essential part of her return to vibrant health. And since becoming co-chairman (with Anthony DuComb) of SAA-SF 10 years ago, organizing that event has grown into a year-round personal mission.

Susan has urged me for several years to come visit her and husband Richard Levine (both attended a TI workshop nearly 20 years ago, long before we met) in Berkeley. After my own cancer diagnosis, it became clear that the perfect occasion to visit Susan and Rich would be to swim as part of Team Susan Survives.

On Oct 1, 350 swimmers boarded to San Francisco Spirit Hornblower yacht to cruise to our dropoff point just east of the Golden Gate Bridge. On the 40-minute trip, dozens of current cancer patients and cancer survivors told moving stories of why they swim. Before we jumped in, each of us had the opportunity to drop a flower into the Bay to dedicate our swim to the memory of a friend or loved one who’d succumbed to cancer. Nearly everyone did so.

Our swim was 1.5 miles (there was also a half-mile option) to Yacht Harbor. There was a huge flotilla of support craft, kayaks and stand-up paddleboards for safety and guidance. This was not a race, but a friendly ‘swim together.’ There were dozens of Swim Angels—many of them former Olympians–to accompany anyone who wanted the comfort of an experienced escort. And a group of four former Women’s Water Polo Olympians, led by SAA-SF honorary chair Heather Petri, passed a water polo ball back and forth during their 1.5-mile swim in choppy waters!

In total SAA-SF raised over $600,000 (Team Susan Survives raised over $100,000 of that total) to support the work of The Center for Cancer Research at Children’s Hospital Oakland, led by Dr Julie Saba, who is herself battling an aggressive form of leukemia; and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital and Dr. Rob Goldsby of the UCSF Survivor Program. The day before the swim, 18 Olympians spent hours with children in the cancer wards of both hospitals.

Next year I plan to return to SAA-SF and to participate in a NY-area event, and do all I can to support SAA’s aims generally. Donations are still welcome for the completed event. If you’d like to help this most worthy organization, please visit my page.

Zero Cancer Update

On Sept 12, I had a whole-body PET scan. For this scan, I was injected with a radioactive glucose solution. (How radioactive? I was advised to stay away from small children for 24 hours.) The glucose travels straight to cancer cells (one reason refined sugars are a dietary no-no for cancer patients). The radioactive element causes active tumors to light up like a Christmas tree on the scan.

Nothing on my scan lit up, meaning whatever tumors I had are inactive at the moment. My oncologist used the welcome words “in remission” to describe my status. This brought peace of mind because my sense of health has declined over the last six weeks, which led to concern that my cancer was advancing despite chemotherapy. I now understand it’s likely this was from the accumulating effect of having ‘poison’ in my system.

The scan did show extensive scar tissue in my pelvis (I do have increasing discomfort there) from formerly cancerous cells that are now dead bone cells. There were also spots on three vertebrae and two ribs. It’s possible for this scar tissue to regenerate into healthy bone cells. I’ll do all I can to help along that process.

Though one effect of the chemo is that my stamina is significantly less than it was even two months ago in mid-summer, I’ve continued swimming regularly, albeit seldom more than 1600m and quite slowly. Even so I was able to swim open water events the last three weekends.

Prior to the SAA 1.5-miler (TI Coach Stuart McDougal also swam), I swam a 5K club swim with CIBBOWS (Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimmers) from Breezy Point in Queens to Coney Island in Brooklyn on Sept 17 and a 2-mile race between Coney Island and Brighton Beach on Sept 24.

This doesn’t quite complete my 2016 Open Water calendar. On Nov 3-5 I will swim portions of 3Days, 3Seas—a series of 10K swims in the Red Sea and Mediterranean, organized by TI Israel.

The post Zeroing Out Cancer with Swim Across America appeared first on Total Immersion.

October 6, 2016

Remain in This Moment

It is so much easier to concentrate on quality while swimming in the Abundant Energy Zone – at the beginning, when things feel fresh for the body and the mind. But after some distance – and that distance is personal to each one – when energy starts to feel scarce, what does your mind and body tend to do?

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Remain in This Moment.

The post Remain in This Moment appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 27, 2016

How to Have Amazing Swimmer’s Hands

This post is excerpted from Lesson 1 of the TI 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course.

I’m known for my strong belief in swimming with the natural ‘training equipment’ with which we come into the world. I do make a few exceptions however, having received great benefit from thoughtful use of three pieces of man-made equipment—the Swimmer’s Snorkel and Tempo Trainer from Finis and the fistglove. In this post, I’ll cover the fistglove.

Fistgloves are a latex glove which wraps the hand into a fist. They were invented by Scott Lemley, swim coach at University of Alaska-Fairbanks. Lemley, an aikido practitioner for many years, was inspired to develop fistgloves after practicing aikido blindfolded. (To understand how much we rely on sight for balance, try standing still with eyes closed.)

In water, the hands are our most important source of sensory information. Take them away and we feel a bit helpless. Just as people who lose their sight become much keener in their use of other senses, depriving the hands of sensory input with fistgloves enhances sensory awareness on all other body surfaces.

Fistgloves are an invaluable learning tool because of three effects:

Better Balance and Stability We unconsciously use the hands to compensate for poor body control. Fistgloves make it exceedingly difficult to use the hands to correct body position. This forces us to develop a balanced and stable core body–freeing the hands to be far more effective in creating propulsion, enabling a more efficient 2-Beat Kick, and making breathing easier and more comfortable.

Hyper-Sensitive Hands The most elusive and important element in an effective Catch-and-Press is the ability to distinguish subtle changes in water pressure with your hands. Just 10 minutes with fistgloves will dramatically increase that awareness.

Better Arm Position Positioning hand and arm to trap a large volume of water is the first step to creating maximum forward motion. When using fistgloves, traction from your hands is reduced so dramatically that you must use your forearm to hold the water. This teaches you to convert your hand-and-arm into a huge ‘living’ paddle.

Can you substitute Fists or Paddles?

Swimming with fists closed (or with index finger extended) is a popular way to improve hand sensitivity–and has the advantage of being quite simple. I did fist-and-finger swimming for decades before I used fistgloves. I always felt it was worthwhile. However, the added effect of ‘wrapping’ my hands in latex made a difference beyond anything I’d ever imagined.

After fist swimming, my hands felt a little more sensitive and my stroke a little better. The first time I used fistgloves, I experienced transformative change in awareness. As I wrote at the time, it felt like “Alexander Popov’s hands had been magically grafted onto my arms.”

Scott Lemley calls fistgloves “the Unpaddle.” I agree. I used paddles for over 20 years. I always felt significantly greater grip while I had them on. And I always felt ineffectual after taking them off. Fistgloves produce precisely the opposite effect: I struggle for grip with them on, and feel utterly amazing after removing them. What could be better than a practice aid that makes your ‘normal equipment’ feel extraordinary?

As well, use of paddles is one of the most common causes of shoulder injury. If you have an error in your stroke, paddles will magnify it. Fistgloves will fix it.

A Starter Guide to Fistgloves

Here are a few guidelines for ‘fistglove rookies.’ With experience, you’ll come up with even more applications.

Focus on sensation. Focus first on creating a sensation of ‘hypersensitive hands.’ You’ll feel helpless at first–like paddling a kayak with a popsicle stick. A few laps later you’ll feel a tiny bit of grip and control. After 20 minutes you may feel almost normal. At that point, remove the gloves. Your hands will instantly feel extraordinary. Continue as long as that feeling persists. At first the effect may last about half as long as it took to create it. With practice, you’ll achieve the ‘fistglove effect’ faster and sustain it longer. Eventually the feeling of hypersensitive hands will become permanent.

Swim short repeats. At first I did mostly 25s and 50s because of how helpless I felt. As I felt more control, I swam farther, eventually up to 500y/m continuously with fistgloves, taking just 1 to 2 additional SPL compared to my ungloved stroke count.

Count strokes. Compare stroke count with and without gloves. Work patiently to reduce that difference. Also compare your stroke count with ungloved hands, before and after using fistgloves. Try this sample set:

Swim 3 rounds of 4 x 25.

Round 1: Swim with ungloved hands. Count strokes.

Round 2: Swim with fistgloves. Count strokes and compare to Round 1. Strive to reduce the difference in counts.

Round 3: Swim with ungloved hands. Count strokes and compare with Round 1. You should be taking fewer strokes.

Optional: Repeat Rounds 2 and 3 to see if you can do slightly better on Rounds 4 and 5 than on Rounds 2 and 3.

The TI 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course teaches ‘Expert’ Catch-and-Press and three other Mastery skills for freestyle. Learn more here.

* * *

Join Me: Swim Across America

On Saturday, Oct 1, I will swim from Golden Gate Bridge to Chrissy Field in San Francisco Bay to raise money for Swim Across America. This is my first time participating in a SAA event.

I’ll swim to honor to honor the memory of two people–my dear friend, Betsy Owens, former chair of Adirondack Masters Swimming, and my cousin, Beverly Sharkey. Each died from cancer. I am also swimming to support my friend Susan Helmrich, a 3-time cancer survivor and the captain of Team Susan Survives.

Please join me in giving to support cancer research, prevention and treatment and make an impact in the fight to find a cure. Even a gift as modest as $10 can make a difference. You may donate here.

Thank you for your generosity and may it lead to a cancer-free world!

May your laps,and life, be as happy as mine.

The post How to Have Amazing Swimmer’s Hands appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 22, 2016

Sleep Your Way To Improvement

When demands build up, sleep is the account we make the most withdrawals upon, rarely paying it back sufficiently. But what price in health, performance and longevity do we really end up paying for that debt?

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Sleep Your Way to Improvement.

The post Sleep Your Way To Improvement appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 13, 2016

Blend-and-Harmonize: A Key to Kaizen

At some point, all Kaizen swimmers employ a learning strategy that cognitive scientists refer to as ‘chunking.’ Chunking refers to grouping separate pieces of information together to facilitate learning by remembering the groups as opposed to a much larger number of individual pieces of information. The types of groups can also act as a memory cue. In TI we group by body segment (head, torso, arms, legs) and skill type (Balance, Core Stability, Streamlining, Propulsion.

We learn to read via a chunking process. First, we learn the sounds of individual letters which assemble into words we generally know before beginning to read. Three individual letters d-o-g or c-a-t form a group that represents a family pet.

In step two, we combine a series of words into a phrase or sentence. Via several additional chunking steps we may acquire the skill of speed reading, in which we rapidly scan a page or more of text, identifying key phrases which convey the main ideas of what we’re reading.

Chunking is a key strategy for learning complicated physical skills such as swimming. In TI, we call this ‘Blend-and-Harmonize’ as in blend several discrete mini-skills, then bring the new skill set into harmony with the whole stroke.

Long before I knew of it as a strategy, I instinctively employed a chunking process to learn new skills. This first occurred nine months before the first TI camp, before I’d chosen the name Total Immersion, or even thought of offering a swim camp for adults.

The first skill was Balance, to which I was introduced by Bill Boomer. Bill taught me to align my head with my spine and shift weight forward to my upper chest. We called it ‘swimming downhill.’ Together, they made my legs feel light, something I’d never experienced in almost 25 years of swimming.

From the start, I realized that I couldn’t fully concentrate on both new thoughts or sensations at once. So I’d spend 10 to 30 minutes concentrating on feeling a straight line from the top of my head to the base of my spine. Then I’d focus on leaning on my upper chest (we no longer teach this) for a similar duration. This is called Block practice.

After several weeks I felt sufficiently familiar with both sensations to begin alternating them—focusing on head-spine alignment one length and swimming downhill on the next. This is called Random practice. (Note: I also practice a drill—similar to today’s Torpedo—that highlighted both, giving me a heightened sensory benchmark to aim for in whole stroke.

After another few weeks, I began to blend the two thoughts. One length focusing on head-spine alignment, one on swimming downhill, and a third blending them. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Now I was Chunking.

I learned later that sequencing Block, Random, and Chunking practice (the names for which I didn’t even know when I began doing that) accelerates transfer of skllls from conscious to autonomic control. Or to use a more familiar phrase: Forming a Muscle Memory.

It took me about five years of similar experimentation to achieve Balance in even a rudimentary way (it felt great at the time, but I didn’t yet know how much better that sensation would become.) Over the next 10 years, I continued to discover new mini-skills—like the Mail Slot entry and reaching below my bodyline–that improved my sense of weightlessness in the water.

But the bottom line is that originally Balance occurred to me as several discrete skills, which I focused on and sensed individually. After the passage of time, and without my realizing consciously what had occurred the multiple, individual sensations consolidated or ‘chunked’ into a single awareness I call “Swimming in Balance.”

When Balance became a single, seamlessly-integrated ‘sensory package,’ that freed up mental bandwidth to add new skills—Stability, Streamlining, Propulsion, and Breathing.

It would be many years before I read about chunking and could apply that term to what had occurred to me. Before and since I’ve developed countless skills by the same process.

For instance—as outlined in the 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course—I achieved a far more refined and efficient freestyle recovery by breaking it into three discrete mini-skills, each of which occupy only a micro-second in the stroke—Elbow Swing, Rag Doll Arm, and Paint a Line.

As brief as they are, I have a keen awareness of each, acquired by applying the proven sequence of Block, Random, and Chunking (or Blend-and-Harmonize) practice to them.

Fast forward to the present day and I have a far more expansive and holistic ‘chunk’ to which I could give the term “My Utterly Blissful Freestyle” which integrates six to eight sizable chunks I’ve developed over the years.

Accessing such high level sensation used to be hit-or-miss. It often took 30 to 60 minutes to ‘find’ the peak feeling I’d acquired at that point. Now those high quality sensations are absolutely dependable—always there–and I can consistently access them within just a lap or two.

May your laps, and life, be as happy as mine,

Terry

The post Blend-and-Harmonize: A Key to Kaizen appeared first on Total Immersion.

September 2, 2016

Zero Cancer Swimming: When the Flesh is Frail; the Mind can be Strong

Last weekend (Aug 28) the NY Times published an essay titled Even Roger Federer Gets Old by Brian Phillips. It was beautifully written and highly entertaining. And it referenced one of my two all-time favorite pieces of sports writing, published exactly 10 years earlier “Roger Federer as Religious Experience,” by David Foster Wallace. (The other is the famous New Yorker article by John Updike on Ted Williams’s last game, Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.)

But I digress. These excerpts sum up the main points of “Even Roger Federer Gets Old.”

When we watch Federer in peak moments, Wallace says, we imagine what it would be like to experience a physical freedom unburdened by pain or weakness, and this in turn helps us cope with the troubling fact of our own mortal embodiment . . . How do you square the image of the transcendent, unchanging champion with the fact of a player who is growing old?

All athletes eventually age out of the games they excel in, because bodies, even supremely capable bodies, are imperfect and subject to time.

While I thoroughly enjoyed reading this essay–and recommend it to you–I thought it struck a more mournful tone than what I’d felt earlier in the month while watching the ‘transcendent champion’ Katie Ledecky (as well as Simone Manuel and Katinka Hosszu) in Olympic Swimming finals.

We all age. We all experience ‘mortal embodiment.’ At 65, I’ve had decades of experience adapting to declines in physical capacity. (I can even work up a bit of empathy for an athlete who–at only 35–is described as ‘growing old.’)

Indeed, in my mid-50s, I felt anything but old–as I enjoyed a few years of unexpectedly fast swims, eclipsing times I’d swum for over 10 years previously. I fancied that stretch of middle-aged ‘youthfulness’ might continue indefinitely. However, at 57, I was hit by an autoimmune syndrome, which aged me athletically to a degree I hadn’t imagined possible.

I learned to adapt to my new limits and, at age 60, found my way back to a performance level which brought enormous satisfaction Though I was still far off the freestyle times I’d done at 55, I felt they were the very best of which I was capable just then. I even managed to record a lifetime best in the 200 Fly that year, showing the benefit of having many events to swim.

The medical treatment I’m now receiving has taken away considerable stamina and strength. Even so–though nearly every race I’ve swum since beginning treatment has been a ‘lifetime slowest.’ I still consider several of these the best swims of my life.

Katie Ledecky as Religious Experience

Far from feeling wistful at the contrast with my current state, I absolutely thrill to watch strong, young athletes performing at their peak. There was a particular shot from the swimming events at the Olympics that brought me to a nearly-ecstatic state: On the final length of several of Ledecky’s races, the NBC cameras cut to a low, front-leading shot that displayed better than any other the extraordinary athleticism of the world’s most dominant swimmer.

I guested on a Slate podcast that week. The interviewer quoted someone as saying Ledecky swam like a man. I said I disagreed. Rather, I said, she swam like a fabulously athletic woman. As a career coach, I LOVE watching that. So, on one side is my capacity to be excited by watching great young athletes at their peak.

On the other, is the question of how–as a lifelong athlete myself–I deal with the frailty of my own flesh. Certainly, not everyone feels this way–but I have absolutely embraced the challenges of continuing to strive to be at my very best–even if that best is considerably diminished from ten years ago–or even last year.

Between normal aging, autoimmune, and now cancer, I’ve had ample opportunity to learn to compensate for loss of athleticism by raising my game–quite significantly–on the side of focus and a wide range of mental and psychological strengths.

In fact the most satisfying race of my life has come since my diagnosis with stage IV cancer. Though it was the slowest 1650-yard free I’d ever swum (albeit less than 30 seconds behind my time when I first swam the event at age 17) I maintained absolutely unwavering focus for 23m10s.

So I experience no conflict between celebrating and being uplifted by young athletes at the peak of their powers and my present physical capabilities. In fact, I believe that–mentally–I’m a match for any swimming gold medalist I saw in Rio. That’s a strength we build upon indefinitely.

[Note: If you are a devoted friend of TI and have M&A experience/expertise, we’d love to talk. Please message Terry at terryswim@gmail.com.]

The post Zero Cancer Swimming: When the Flesh is Frail; the Mind can be Strong appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 26, 2016

Zero Cancer Swimming: Healing “Exercise” and Striving Together

TI Coach Suzanne Atkinson is an M.D., a trained exercise physiologist, and a highly versatile and successful coach of swimmers, triathletes, and cycling. With such academic and professional credentials, you might expect Suzanne to define exercise in physiological terms—e.g. “increase the heart’s stroke volume.”

But two years ago, while making an exercise physiology presentation to a gathering of TI Coaches, Suzanne defined exercise as: “Moving your body in a functional way for health, fitness, and enjoyment.”

I found that definition so relatable and holistic I immediately adopted it as my own. This allowed me to again think of my swim practice as a form of exercise—something I hadn’t done in 10 years.

In a shift that was so gradual as to be almost unconscious, I’d begun thinking of swimming as a movement art—like aikido, or dance, or yoga–which I sought continuously to refine. I still received the aerobic and muscular benefits of exercise but–as a motivation–that had become distinctly secondary to the sheer satisfaction of how good my stroke felt.

Years earlier I’d made a conscious terminology change–referring to my regular hour-plus of swimming as a practice, rather than the far more common term ‘workout’ which I’d also used for 25 years. Initially, I meant practice session: Conditioning ‘happened’ while I devoted my pool time to honing skills.

Since turning 60, I’ve thought of swimming as a life practice, as defined by George Leonard, the author of Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment: “A set of related activities done with the intent to create enduring positive change in body, mind, and spirit.”

Channeling Qi

I was introduced to Qigong as a healing modality by my daughter Carrie in April following a mini stroke. Carrie credited Qigong with helping her overcome a debilitating chronic illness. After years of conventional medicine had left her feeling hopeless, Qigong practice brought reliable relief and made her feel she was taking charge of her recovery.

Qigong perfectly complemented my vision of swimming as life practice. It’s a 4000-year old Chinese health practice used to heal illness, maintain health and improve vitality through movement, breathing, and focused intention. The word Qigong combines two Chinese words: Qi (chee) is the life force that flows through all things. Gong (kung) refers to skill cultivated through regular practice.

There are hundreds of Qigong sequences, some so complicated they take months to learn. Carrie taught me just one—the Flowing Movement, which had the virtue of being so simple it took only 10 minutes to master the basics.

Stand with knees slightly bent, arms at sides and erect—but relaxed–posture. Lift straight arms forward to shoulder level–palms first–rising onto the balls of your feet as you do. Inhale as the arms lift and visualize drawing qi from the earth through the balls of your feet. Circulate the qi through your body, concentrating it where you wish healing to occur.

Then turn palms down and press the arms down and slightly behind your legs, rocking onto your heels as you do. (Carrie recommended I imagine moving my hands through water; this really helped.) Exhale as arms come down and send the qi back into the earth through your heels.

While I learned the movement in minutes, it many hours to learn to maintain a steady focus on concentrating and directing qi, which is the essential part of qigong practice.

I did 40 to 60 repetitions (in sets of 10 to 20) first thing in the morning, then another 20 to 30, during breaks from work at my desk, throughout the day. On each, I employed visualizations directed at healing symptoms from the stroke I’d suffered April 7.

To regain steadiness on my feet, I practiced barefoot on grass, visualizing that I was rooted deep into the earth. To heal blurred vision, I gazed at a tree while practicing, striving to see the outlines of individual leaves. Like Carrie, I felt empowered during practice and healthier in body, mind, and spirit after it.

The Zero-Cancer Zone

I brought Qigong influence to the three or more yoga classes I attended each week. When the opportunity presents, I look in the mirror with a wide smile, note how healthy I look and feel gratitude for being there.

In standing positions, I visualize drawing prana (the yoga equivalent of qi) from the earth through my front foot as I inhale, circulate it through my body, and return it to the earth through the rear foot as I exhale. Next breath, I reverse the flow. As with qi, I direct the prana to the places needing healing.

Strength training has become increasingly vital as a health practice because hormone treatments put me at risk of osteopenia/osteoporosis and because strength training, as part of a well-rounded exercise program has been shown to significantly enhance the effect of chemotherapy or radiation.

As with yoga and qigong, I employ visualization in strength training. Pushing a weight up becomes an ‘active affirmation’ that says: “My body is strong and healthy and has the resources it needs to get better.” I call these blogs Zero-Cancer Swimming because swimming, and these other activities do, in fact, ‘zero-out’ cancer. I feel feel healthy, strong, and vital while doing them. I always feel better after moving my body than before. And they are proven cancer-fighters.

Challenge the Mind: Heal the Body

This brings us full circle to swimming. While I need to take it easier on myself than before, my practices remain as cognitively and neurally demanding as ever with a keen focus on attaining mastery in the subtlest skills, and/or doing exacting tasks involving SPL, Tempo and/or Time.

For instance, earlier this week I swam a mile in Lake Minnewaska, four 400-meter loops along the cable. Because I was recovering from a bout with gastroenteritis and my energy level was low, I swam quite gently.

Northbound, I focused on forming long, sleek, stable lines with each side of my body; ‘holding my place’ by applying feather-light pressure with a soft lead hand; and avoiding water disturbance as I entered and rotated to form a new line.

Southbound, I counted strokes, trying to swim 200 meters in fewer than 190 strokes. It took laserlike concentration to reach the end of the cable in 188 to 189 perfect strokes.

The following day at the Ulster County Pool, I swam another mile in 8 repetitions of 200 meters. Again I swam gently, but I challenged myself to steadily increase my 200-meter pace while maintaining Stroke Length. My baseline focal points were the same as at the lake.

On my first 200, I averaged 43 strokes per 50-meter length and my 200 time was 4:00. On the next three repeats my time improved only slightly, to 3:57, but I gradually reduced stroke count to an average of 41 SPL by being softer and more patient with my lead hand. On the final four, I added back a few strokes per 200, while swimming slightly faster. On my final 200, I averaged 42 SPL and finished in 3:54.

Twelve months ago I was swimming 50% to 100% farther in each practice, at paces 5% to 10% faster, but these metrics matter less than what my senses and spirit tell me. By those measures I’m swimming as well or better than I ever have. Most importantly, as in my other activities, I now sense every stroke channeling vitality and healing energy where I need it.

Three concrete measures of the efficacy of my self-healing modalities are:

My stroke symptoms—unsteadiness and blurred vision—have disappeared. My gait and vision are as good as they were before the stroke.

My blood pressure, which had spiked as high as 190/100 is now consistently lower than it’s ever been in my life. Yesterday it was 116/69.

In the spring, pain in my hips often required me to take powerful pain meds to sleep. Now I’m barely aware of hip pain.

Striving Together in Memory of Betsy Owens

On Aug 13, I did my first open water race of the summer—the Betsy Owens Memorial 2-Mile Cable Swim in Lake Placid. For two weeks prior I’d been laid low by gastroenteritis and cellulitis (due to lowered resistance from chemo), so my energy level and preparation were below what I’d hoped for. But I wouldn’t miss the event for anything, since it memorializes Betsy Owens, a former chair of Adirondack Masters Swimming and a dear friend, who’d succumbed to breast cancer in 2003.

There were 1- and 2-mile options, but I really wanted to swim the 2-mile, though I hadn’t swum as far as two miles (3200m) in any practice this summer. I had no concern with time or place; I just wanted the joy of participating and to see old friends.

I planned to swim quite easily for the first seven of eight 400m lengths on the cable then see how I was feeling and whether I could finish a bit more briskly. The night before the event I timed two 400m cable lengths on the course at what felt like a sustainable effort level. The first was 8:17, a pace slightly over 1:06 (1 hour 6 minutes) for 2 miles. The second was 8:30, a pace of 1:08.

I’d swum the Betsy at least a dozen times before with a best time of 45:40, at age 54, and a slowest of 53 minutes at 63. But this year I’d enjoy the swim, whatever time I might record.

We started in waves of 10 swimmers, 30 seconds apart. Based on my estimated seed time of 26 minutes for 1500m, I started in the third wave. On the start I allowed everyone else in the wave to move ahead, to avoid slowing anyone with my leisurely pace. Halfway down the 400m course I found myself on another swimmer’s feet. It took a bit more effort than I’d planned on expending to stay in his draft, but I decided to try to maintain that position and see what happened.

Lap after lap, I was intently focused on maintaining an optimum drafting position without touching my draftee’s toes; minimizing drag and water disturbance; and making every stroke count. With the exception of closely following another swimmer it was just like my every practice swim.

As we passed a mile, I began to smile at how good I felt. Not only at being able to maintain relaxation while swimming at a brisker pace and higher effort level than I’d thought possible—or had practice all summer. But also at the feeling of using my body to its fullest present capacity, and the sheer pleasure of racing in open water, and especially on a cable course.

On the seventh leg, we picked up another swimmer and I could feel our pace pick up. I stayed with it by more consciously driving the high hip. I anticipated an even brisker pace on the final leg. As we rounded the buoy I pressed more firmly with my hands and lower leg (in the 2-Beat Kick). It took all I had to stay with our little group. I felt real joy as we crossed the finish line.

John Lomasney on right, with whom i Strived Together

In the chute as we walked to shore where our numbers and places would be recorded, the swimmer I’d been following and I embraced. My race partner, without whom I could never have recorded my time of 1:02:15.87, was John Lomasney. It turns out that John is a TI fan. He knew it was me on his feet and was conscious throughout the race of using his best form. John is a member of the Binghamton University Masters Swimmers (BUMS).

Apres-Swim with the ‘BUMS’

The Latin root for compete—com petere—means “strive together.” And that is certainly what John and I did for just over an hour that day.

The post Zero Cancer Swimming: Healing “Exercise” and Striving Together appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers