Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 19

December 21, 2015

Opportunity in Adversity

Ten years ago, several months before my 55th birthday, I set a group of BHAGs or Big Hairy Audacious Goals. The term comes from the book Built to Last by Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, who studied businesses that had maintained influence and excellence over many decades. BHAGs focus on enduring and meaningful impact: Henry Ford set out to democratize the automobile; in the early days of Apple, Steve Jobs talked of putting a computer in every home–40 years later there’s a computer in everyone’s pocket!

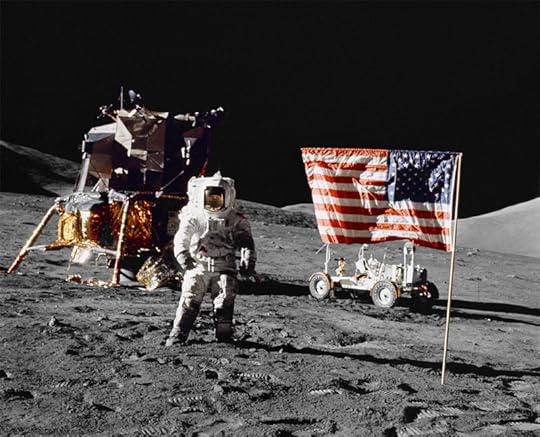

BHAGs embody visionary thinking. In 1960, JFK proposed to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. This achievement, fulfilled in 1969, remains a defining and uplifting moment in American history–and, well, “a giant step for all mankind,” as Neil Armstrong put it.

“A small step for man; a giant lap for all mankind”

Like the moon mission, BHAGs usually take a decade, or decades, to achieve. But I aimed to fulfill mine within a year. They included:

Complete a second Manhattan Island Marathon Swim.

Win my first National Open Water Championship.

Break a National Masters Record in open water. (I’d never even set a team record in high school or college.)

Win a World Masters Championship Medal in the 3K Open Water event.

Happily, I did achieve all of those and more–winning four national championships, at distances from 1 mile to 10K, and breaking two national records for the 55-59 age group, the 1- and 2-Mile Cable Swims.

My greatest benefit was gaining a sense of having a mission to accomplish, which lasted for nearly a year from the time I conceived of them. Not a single practice during that time ever felt like a check-off in my daily routine. They all felt important–even urgent. The imprint of a ‘year of high purpose’ endured well beyond that period and has had far-reaching impacts.

While I couldn’t have achieved my goals without a highly-efficient stroke, even more critical than how I swam was how I thought. For a decade previously, I’d become increasingly interested in Positive Psychology–the study of thought processes displayed by high-performing individuals.

I learned about the traits, behaviors and mindsets of such people in books such as Learned Optimism by Dan Seligman, Mastery by George Leonard, Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi PhD, and the principles of Deliberate Practice by Anders Ericsson PhD. Setting such galvanizing goals provided an ideal opportunity to test these principles.

By applying these lessons I achieved far beyond what I’d always thought was possible. As a result of that experience, Total Immersion has emphasized effective thinking as much as effective movement.

Goal-setting with the Flow

As I approached my 60th birthday in 2011, I faced physical challenges that limited what I could accomplish athletically. In my late 50s, I began to experience fatigue and chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with the autoimmune syndrome, Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR). I also began to suffer foot and calf cramps after barely an hour of swimming–an effect of arthritic narrowing in my lower spine.

Between them, my training was significantly limited compared to previously. If I swam a bit too long or hard, I could be left feeling drained for hours after. And my feet and calves often began cramping after little more than 2000 yards.

Yet though my training was likely to be quite limited, I still craved the sense of purpose and urgency I’d experienced five years earlier. Going with the flow means seeking opportunity in adversity. So I decided to Goal-set with the Flow.

My mid-50s accomplishments had been in my lifelong strong suit, distance freestyle. At 60 I decided to strike out in a new direction, emphasizing events outside my comfort zone–shorter distances and the other strokes. I’d swum only freestyle for most of my life and had only begun to focus on other strokes a few years earlier.

As well, the limitations on how long or intensively I could train resulted in two surprising developments:

Knowing that I had a practice ‘budget’ of 2500 yards made every lap seem far more precious. I would allot time only for activities proven to improve performance.

Needing to be careful about intensity, pushed me to rely less than ever on power and muscle, and find the easiest way to accomplish any task.

The results were thrilling and have transformed my approach to practice and training. In 2011, at Masters Nationals I entered every discipline but backstroke–and meldaled in all four! In 200 Butterfly, I even did a lifetime best, swimming faster than I had at 55 when I was in the midst of achieving BHAGs in distance freestyle.

Taking a ‘sneaky’ breath in butterfly

Briefer, More Focused, Better Than Ever

Finding opportunity in adversity has led me to embrace practices that emphasize focus over duration. I seldom swim beyond an hour; many of my practices last just 40 to 50 minutes. What I love most is how keen my focus remains for that duration–quite literally from first stroke to last at times.

I include only two to three sets or activities in most practices. In each I’m either trying to perform a subtle skill better than I ever have in my life. Or ‘solving problems’ related to controlling stroke count, while swimming faster–on the clock, or on my Tempo Trainer. I can succeed at most tasks only by giving it my full attention. Moments of Flow have become more routine than ever before.

Practicing this way has produced surprising–even thrilling–breakthroughs in awareness or control each year. My pull, kick, and breathing are all strikingly more efficient than they were before I turned 60–a development confirmed by comparing recent video with video shot in my 50s.

And it my stroke doesn’t just look better. It feels amazing almost every day–better than it ever has. Twice in one recent week I posted this on the TI Facebook page: “I felt fantastic in the water today–I’ve never felt this good before.” Not an insignificant claim after 50 years of swimming.

I’ve never looked forward to swimming as much as I do now, nor have I felt a greater sense purpose and flow. I still have PMR symptoms; I often feel achy and mildly flu-like as I get in the water. But within minutes I feel indescribably great. Swimming has always been known for its unique healing properties. I seem to have tapped into something beyond.

In three months I’ll enter the 65-69 age group. As I did at 55 and 60, I plan to attend Masters Nationals in the spring to get a concrete gauge on my performance capabilities. In early November I wrote out my goals for the next six months. As I was writing them, I felt the familiar sense of purpose and urgency.

Two weeks later I received a diagnosis of prostate cancer–fairly common in men my age. Fortunately my prognosis is good. I’m more grateful than ever for how central swimming goals have become for my life.

In my next post, I’ll write about the opportunity in this latest adversity.

The post Opportunity in Adversity appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 20, 2015

Opportunity in Adversity

Ten years ago, several months before my 55th birthday, I set a group of BHAGs or Big Hairy Audacious Goals. The term BHAG comes from a business book Built to Last by Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, who studied businesses that had maintained influence and excellence over many decades. BHAGs focus on enduring and meaningful impact–Henry Ford set out to democratize the automobile; in the early days of Apple, Steve Jobs talked of putting a computer in every home. (Now it’s in everyone’s pocket!)

The main value of a BHAG is to avoid too-small thinking In 1960, JFK proposed to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. This achievement, fulfilled in 1969, remains a defining and uplifting moment in American history. And scientific advances associated with it have brought countless benefits here on earth.

While business BHAGs usually have a time frame similar to the moon mission–taking a decade or more to achieve–I aimed to fulfill my goals within a year. They included:

Complete a second Manhattan Island Marathon Swim.

Win my first National Open Water Championship.

Break a 55-59 National Record in open water. (I’d never even set a team record on undistinguished high school and college teams.)

Win a World Masters Championship Medal in the 3K Open Water event.

Happily, I did achieve all of those and more–winning four national championships, at distances from 1 mile to 10K, and breaking two national records for the 55-59 age group, the 1- and 2-Mile Cable Swims.

Attaining each goal provided a great sense of accomplishment. More important though was the sense of vision and purpose I experienced from the moment I set them. Virtually every practice had a greater sense of urgency–at times even a sense of mission.

While I gained great satisfaction from achieving them, the lessons I learned during the year between conceiving and completing them have endured ever since and had far-reaching impacts.

While the stroke efficiency I’d been working on since founding TI was instrumental, the more critical factors were behaviors and mindsets I cultivated while pursuing them. Years earlier, I’d become interested in Positive Psychology–the study of our thought processes while performing at our greatest potential. Those who are high-functioning and report the greatest sense of satisfaction with their lives display many traits, behaviors and mindsets in common.

I learned about them in books such as Learned Optimism by Dan Seligman, Mastery by George Leonard, Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi PhD, and the principles of Deliberate Practice by Anders Ericsson PhD. Setting such galvanizing goals provided an ideal opportunity to test these principles.

By adopting new mindsets and behaviors I swam far better than I’d previously thought was possible. And as a result of that experience, Total Immersion has emphasized effective thinking as much as effective movement.

Goal-setting with the Flow

As I approached my 60th birthday in 2011, I faced physical challenges that limited what I could accomplish athletically. In my late 50s, I began to experience fatigue and chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with the autoimmune syndrome, Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR). I also began to suffer foot and calf cramps after barely an hour of swimming–an effect of arthritic narrowing in my lower spine.

Between them, my training was significantly limited compared to previously. If I swam a bit too long or hard, I could be left feeling drained for hours after. And my feet and calves often began cramping after little more than 2000 yards.

Yet though my training was likely to be quite limited, I still craved the sense of purpose and urgency I’d experienced five years earlier. Going with the flow means seeking opportunity in adversity. So I decided to Goal-set with the Flow.

My mid-50s accomplishments had been in distance freestyle. At 60 I decided to strike out in a new direction–emphasizing shorter distances and the other disciplines–butterfly, backstroke, breaststroke and individual medley. As well, the limitations on how long or intensively I could train resulted in two surprising , developments.

Knowing that I had a practice ‘budget’ of 2500 yards or less created a determination to make every stroke count. I thought carefully about what I allotted time to in practice and eliminated anything for which there wasn’t a proven positive effect on performance.

Needing to be very careful about intensity, pushed me to rely less than ever on power and muscle, and find the easiest way to accomplish any task.

The results were thrilling and have transformed my approach to practice and training. In 2011, at Masters Nationals I entered and medaled in four of the five disciplines–Butterfly, Breaststroke, Individual Medley, and Freestyle. Prior to my 40s I’d never swum anything but freestyle, and it wasn’t until my mid-50s that I became goal oriented in the other strokes. In the 200 Butterfly, I even did a lifetime best, swimming faster than I had at 55 when I was in the midst of achieving BHAGs in distance freestyle.

Briefer, More Focused, Better Than Ever

Finding opportunity in adversity has led me to embrace practices that substitute focus for duration. I seldom swim beyond an hour; many of my practices last just 40 to 50 minutes. What I love most is the keen focus I can maintain for that duration–quite literally from first stroke to last. (I’ve done the same in other activities–riding my mountain bike briskly for an hour or less, practicing yoga at home for 25 minutes–or attending classes that last an hour, completing strength training in 25 minutes.)

Most practices consist of only two to three sets or activities. Each one combines a focus on executing some subtle skill better than I ever have in my life, while ‘solving problems’ in maintaining a constant stroke count, while trying to swim slightly faster–on the clock, or on my Tempo Trainer. I design these sets so I can succeed only by giving it my full attention. That produces moments of Flow in virtually every practice.

Since turning 60, I’ve made thrilling breakthroughs in awareness or control each year. My pull, kick, and breathing are all strikingly more efficient than they were in my 50s. (And they were better at that time than ever before.)

I can honestly say that my swimming feels better than it ever has. Twice in one week recently I posted on the TI Facebook page “I felt fantastic in the water today–I’ve never felt this good before.” Not an insignificant claim after 50 years of swimming.

As a result, I go to the pool with a keen sense of anticipation, and enjoy a greater sense of flow and purpose, than I ever have. I still have PMR symptoms; I often feel achy and mildly flu-like as I get in the water. But within minutes I feel indescribably great. I’m fortunate that swimming has such remarkable healing properties.

In March I will enter the 65-69 age group. As I did at 55 and 60, I plan to attend Masters Nationals next spring to get a concrete gauge on my performance capabilities. In early November I wrote out my goals for the next six months. As I was writing them, I felt the familiar sense of purpose and urgency that has become so addictive.

Two weeks after my goal-setting exercise I receive a diagnosis of prostate cancer–something quite common in men my age. Fortunately my prognosis is good. In my next post, I’ll write about the opportunity in this latest adversity.

The post Opportunity in Adversity appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 12, 2015

Test For Progress And Weakness

A few excerpts from the post Test For Progress And Weakness…

Remember that the results – both successes, and more importantly, your failures – are just information which will show you how well new skills have been integrated into your swimming system. Data that reveals weak spots is good news because it shows you where you need to concentrate your effort in your precious practice times.

Success in this program is defined as improvement, not perfection. More specifically, success is indicated by an improvement in your external results because of a specific changes you’ve made in your internal control. Improvements in quality (it feels better, easier) come before improvements in quantity (it makes me move farther, faster), so don’t overlook those internal improvements when looking at your external results in the test swims.

Testing is a tool that is very effective for learning when used frequently. It forces the brain to recall and strengthen the synapses where information and skills are wired, and to reveal which information and skills are not wired well – weaknesses – so the student (and teacher/coach) knows where to focus further effort.

~ ~ ~

To read more of this article – Test For Progress And Weakness – visit Coach Mat’s Smooth Strokes Blog.

The post Test For Progress And Weakness appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 11, 2015

How to Practice

Two days ago I brought two students, Dmitry and Sergey, to Bard College to guide them through a practice that was 100% focused on increasing efficiency via improving technique. They had just completed two days of instruction–four 90-minute sessions in the Endless Pool at our Swim Studio. During the final session, they said they’d like to extend their stay and squeeze in one more session.

Both had radically transformed their strokes during the previous two days. But such rapid transformation isn’t always easy to maintain–especially after returning to the very different environment of a lap pool, and to a setting where the pull to resume old routines may be strong. If we did another session in the Endless Pool, I wouldn’t attempt to introduce anything new–only to review and deepen the skills they’d already learned.

But I felt there could be even more value in testing the new skills in the same environment to which they’d be returning. I proposed we go to Bard College the next morning, where I could guide them through their first post-workshop ‘real world’ practice. The experience turned out to be as valuable for me as for Sergey and Dmitry.

We began by reviewing the first and most ‘non-negotiable’ skill of efficient swimming: Establishing a neutral–and weightless–head position. I had them repeat Superman four times. Glide five yards from wall to backstroke flags. Stand for a breather and return.

On the first two reps both were holding the head slightly elevated. I lightly wagged the head to reveal that they were maintaining slight neck tension. On the next two reps, their heads were fully released and aligned with the spine. The visual cue–shown below–is that only a small sliver of the back of the head is visible above the surface.

Ready for the next step: Add a few strokes to test whether they could continue resting their heads on the water. Would I still see that same small sliver of head as they stroked?

We did four reps of Superman plus 4 to 5 non-breathing strokes. I asked them to assess whether their head position felt the same–with same degree of relaxation in neck muscles–after they began stroking. Thet passed that test, so we advanced to a slightly more demanding skill.

Could they maintain this new skill for a full 25 yards–14 to 17 strokes rather than 4–and while breathing. I instructed them to push off in Superman, establish the weightless head sensation, take four non-breathing strokes, then breathe bilaterally the rest of the way. Could they maintain a neutral, weightless head while breathing–as shown below?

Sergey succeeded. Dmitry lifted his head while breathing. I asked him to tune into the feeling of having the head rest on the surface during the non-breathing strokes, then check whether he felt the same sensation as he breathed. While he didn’t fully correct this error, it was valuable information to identify this as a problem to be solved in practices that followed. I made a mental note to finish the practice by having Dmitry review the TI “Nod” drill–shown below–which can correct head-lifting in as little as 10 minutes.

Nodding to the left

Following the same sequence, we cycled through several foundational mini-skills. For each cycle, choose ONE Focal Point or Mini-Skill while doing the following:

Do several reps of a standing rehearsal or drill–depending on the skill.

Swim several short reps, transitioning seamlessly from the drill to 4 to 5 non-breathing strokes.

Swim 4 to 8 x 25 to test the durability of the new mini-skill with more strokes and while breathing.

The second cycle was most instructive for all three of us. In our first cycle, I’d observed that both Sergey and Dmitry looked a bit tight, and uncertain, during Recovery. To address this, I instructed them to lightly Paint a Line on the surface with fingertips (hanging from a Rag Doll arm)

First they rehearsed Rag Doll/Paint a Line–as shown below..

Rehearsal: Paint A Line and Rag Doll with right arm

Then they tested their ability to do it while stroking. It should look like this:

In this case, it was Dmitry who succeeded. Sergey’s hand was a bit too close to his body–increasing tension in his shoulder. It was also several inches off the water–an occasion for energy waste, especially when multiplied by the thousands of strokes he would take in a triathlon or open water swim.

A much more important revelation was the keen degree of attention required for new skills that call on fine motor coordination–requiring the cooperation of multiple small muscles. This was an opportunity for a critical takeaway about the Skill of Focus.

Just as with motor skills, one must begin developing mental skills with relatively undemanding tasks. E.G. Forjust 4 to 5 strokes, can you lightly trace a wide straight line on the surface with fingertips. There’s no point in going farther–either a more complex skill, or swimming a greater distance–until you succeed at this.

To develop the ability to perform complex skills, one must first achieve consistency–and a degree of effortlessness–in a series of much simpler mini-skills.

To acquire the capacity for laser-sharp and unwavering focus–e.g. to remain calmly observant in a chaotic-seeming environment like the start of a triathlon swim–one must first be able to concentrate on doing one simple thing for 25 yards or even less in a quiet pool.

During our practice I was able to not only make corrections to form, but also to leave a much larger lesson: Your goal on each rep is not only to improve a motor skill; it’s to strengthen your capacity to hold one thought.

By the way, my own swimming received a striking benefit. When I wasn’t observing, I swam behind Dmitry and Sergey, practicing the same skills and testing my own focus. (I [passed that test–a result of tireless practice.)

At the beginning I took 13 strokes for 25 yards. Then my count improved to 12 strokes. And a few times I crossed the pool in 11 strokes. Before we got out I had to test this efficiency on a continuous 50.

First 25, 12 strokes. Flip turn and pushoff. 2nd 25, 12 strokes for a total of 24 strokes for 50 yards.

I hadn’t swum 25 yards in fewer than 25 strokes in several years. I was so pleased I immediately swam another to see if I could repeat it. Voila, I did.

Very happy laps indeed.

All skills and Focal Points mentioned in this post are shown and described in the downloadable TI Ultra-Efficient Freestyle Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit.

And if you’d like to spend five days in a warm climate Feb 25-29, receiving this kind of coaching from me and several TI Master Coaches–swim in open water, join us at our Tri-Swim Camp at the National Triathlon Training Center in warm, sunny Clermont FL.

The post How to Practice appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 27, 2015

Guest Post: From Swimming Nightmare to Swimming Dream in One Month

Ten days ago, I received an email notification to moderate a new comment on my recent blog “Guaranteed” Speed: Swim Faster the Smart Way While I receive such notifications every day, something about this one caught my attention: The commenter was from Saudi Arabia–the first time since founding TI in 1989, I’d heard of a TI fan in that country. So I emailed back to inquire how he’d become interested in TI. The story Amir Khan shared with me was so unique I invited him to tell it in a guest post. I hope you enjoy it as much as I have.

By Amir Khan

This is the story of how I went, in one month, from a ‘nightmare’ relationship with swimming to a dream of becoming the first TI Coach in Saudi Arabia. It began when we moved to a community with a 25- meter pool. My youngest son Humza immediately became fascinated with the idea of swimming. I’d taught him squash, badminton, basketball, and many other things. He thought of me as his superhero.

My wife chimed in, asking me almost daily when I would teach Humza to swim. I didn’t have the heart to reveal my guilty secret to them: As a grown man, I still couldn’t swim myself. How would that look in Humza’s eyes?

Outside swimming, I was accustomed to setting goals, working diligently, and achieving them. After carving out a successful career as a CPA, at 36, I became Chief Financial Officer of a billion-dollar corporation. At 44, I was an uplifting example for my community, family, and son, yet haunted by failure as a swimmer.

I couldn’t disappoint my son. I needed to learn to swim. And quickly. But how?

My swimming ‘nightmare’ began at age 7, when my mother took me to the school swimming coach. She didn’t have to force me. I was as excited about learning to swim then as Humza is now. But my excitement was quickly extinguished.

The coach’s militaristic manner, the endless kicking, and the feeling of dragging my body through the water discouraged and depressed me so much that I told my mother I would quit school rather than continue with swimming classes.

After 37 years it was time to confront and conquer my lifelong demon. The esteem of my family and son was at stake.

After joining a gym with a 25-yard pool, I browsed YouTube for swimming examples and tips. But it seemed as if nothing had changed in 35 years—coaches telling me to work hard and kick more.

Fortunately I found a video of Terry Laughlin demonstrating TI. I was mesmerized by his calm grace. I’d never seen anyone swim like that—he looked like a happy dolphin enjoying the touch of water!

Another video showed someone demonstrating Superman. I tried that on my next visit to the pool. A few minutes of gliding effortlessly, feeling almost like I was flying, was all it took to convince me this was the solution I’d sought.

I returned home and ordered a downloadable TI self-coaching program. Minutes later it was on my desktop. I began studying it immediately. I felt I’d found a magic wand for swimming transformation!

I started practicing Superman, Torpedo, Skate–taking a few strokes after each. I began to fall in love with swimming, spending over two hours each time practicing and enjoying the TI way.

My fellow swimmers were skeptical. They said I was wasting my time and should go back to kicking with a board. The swim coach was no more encouraging: After watching me practice balance and streamline drills, he asked, “What are you doing; you can’t swim even 10 feet this way.” I replied, “I’m using the TI method to learn to swim like Terry Laughlin.”

But after 10 days of practice, I completed my first full length of the pool, and was still breathing easily at the finish. After seeing this, the coach said, “Whatever you’re doing is working; keep it up.” And after only 10 more days, I swam a full kilometer with rest breaks along the way.

I was fortunate to discover TI at the very start and avoid wasting time. I followed the TI method in spirit and as described step by step. I wonder if I’m the first person in Saudi Arabia who is practicing TI.

While few people here speak English, Saudi Arabia is a quite prosperous country with per capita income almost on par with the US. I believe interest in TI will grow as more people see it for themselves. The other swimmers at my pool can’t believe that I learned on-line. They ask if I’m keeping a secret. But now they want to learn TI, and I’m helping them as best I can.

I also created a TI fan club on an iPhone app. Within days it had more than 35 members—20 from my pool, plus others from my neighborhood. Though I was a non-swimmer just a month ago, I already feel inspired to become the first TI Coach in Saudi Arabia.

Who could imagine that an on-line program could create such complete transformation so quickly? But the TI method is logical, natural, and easy to follow. And swimming the TI way feels like following a stream of water as it flows from the hills to the sea.

I also love the Kaizen philosophy. Each time I dive into the pool I have key points to focus on and I always leave the pool happy and feeling that I’m a better swimmer than before.

My next goal is to swim open water, ideally with Terry! Before becoming a coach I must continue improving my freestyle. And I already have my New Year’s resolution: In January I will begin using my Academy subscription to learn Butterfly the TI way, followed by learning TI Breaststroke.

I am a proud father, an exemplary figure for my son—and a future TI Coach. No one but my fellow swimmers knows that only a month ago I couldn’t even float. My neighbors now say I swim like a fish!

Humza, now age 11, with his ‘superhero’ dad, Amir

The post Guest Post: From Swimming Nightmare to Swimming Dream in One Month appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 21, 2015

What if I am practicing the wrong thing?

I’ve approached questions and comments like these at least a couple times before on my blog, and let me try another…

What if I am practicing the wrong thing? I don’t want to get good at something that is incorrect!

Two recent blog posts address part of this concern:

How Long Will It Take?

Correction vs. Over-Correction

There may be many features in your stroke that are not ‘correct’ or not close to the ideal you have in mind. The first post offers some perspective on how much you need to work before experiencing a change that sticks. The second post offers some guidance and encouragement for improving your understanding of how focal points work, and how to cooperate with the correction process better.

In this post I want to help improve understanding and attitude about working through the change process.

First, the kind of help many swimmers are seeking is about changing something from ‘incorrect’ to ‘correct’. Obviously, the swimmer needs to affect some sort of change in her stroke pattern and needs a method for doing that.

The next kind of help swimmers seek is taking something that is ‘correct’ and making it even better. We might call that enhancing the stroke skills.

Consider that if you change your stroke length or the tempo a little in order to adapt to a different pace or different water conditions, that requires a change in the stroke pattern, does it not? There is a range of possibilities for some parts of the ‘correct’ stroke, and the better choice is dependent on the situation. A swimmer who is capable of handling a wider range of swimming events, conditions and paces needs to be able to adjust these variables to adapt appropriately to that situation. So, even a ‘nearly perfect’ swimmer has to be able to change things in her stroke, and do it quickly, and hold it consistent. She has to have a box full of memorized patterns she can choose from.

What does correcting a stroke error and enhancing a stroke by adjusting some variable have in common?

The intentional act of changing a feature in the stroke.

~ ~ ~

To read more of this article – Stroke-Change Skill – visit Coach Mat’s Smooth Strokes Blog.

The post What if I am practicing the wrong thing? appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 20, 2015

Corsica to Sardinia: A ‘Bucket List’ Swim

On October 19 I swam from Corsica to Sardinia–covering 15.5 km (9.6 miles) in 4 hours 31 minutes–with Tommi Patilla and Lennart Larsson. This is the story of that swim.

L to R: Tommi, Terry, and Lennart. Rear: Corsica

Some swim for exercise, others for a sense of accomplishment or to achieve personal bests. Since my 50s, I’ve swum mostly for the sheer pleasure of it. If it’s not fun, why do it?

Exercise? That ‘happens.’ And meaningful goals are never far from mind. But what I want most is to feel engaged in body, mind, spirit–that there’s nothing I’d rather be doing and to leave the pool counting the hours until I can swim again.

Even in an aging 25-yard chlorine-scented box, I have literally magical moments virtually every time. As good as that may sound, my peak experience in swimming is swimming with friends in a beautiful natural setting. It’s hard to surpass the Shawangunk ‘Sky Lakes’ where I swim as often as possible from early May to late October.

August 28, 2014 7:30 pm Lake Minnewaska Twilight with Catskill Mountain backdrop.

My most memorable experiences of all happen during swimming ‘treks’–swims that belong on any swimmer’s bucket list. During these, I explore a part of ‘Planet Water’ to which access is granted only to a few.

Think of these as a swimmer’s Mount Everest–one that puts you in far more exclusive company, at a fraction of the expense . . . and no risk of falling into a crevasse or being caught in an avalanche. Such an experience is made far richer when shared with friends, such as Lennart and Tommi.

Lennart, 66, is chairman of Oppboga, a packaging company in Orebro, Sweden. He began swimming at age 57, after running dozens of marathons–including an impressive five sub-2:35. Lennart became a TI swimmer early on and has completed about 15 marathon swims in his 60s, including the challenging Gertrude Ederle Swim in NY, and–twice–the 22K Vidostern in Sweden. Lennart’s greatest pleasure is informal, self-organized swims with friends for fun.

Tommi, 47, began swimming at age 40. At a TI Open Water Experience in St John USVI, Tommi fell in love with long open water swims. Because of the demands of his work as a cardiothoracic surgeon, Tommi can train only four to five hours a week. Even so, he completed the 28.5-mile Manhattan Island Marathon June 28 of last year, placing 3rd of 23 swimmers and still feeling fresh after nine hours. In 2016, Tommi plans to tackle Catalina Channel, swim from Mallorca to Menorca . . . and book a 2017 English Channel slot.

We swam Gibraltar Strait in Oct. 2013, covering the 18K from Spain to Morocco in 5:11. We did the whole swim as a “school of humans” — in close formation and synchronizing our strokes, as shown below. Read about this amazing experience in Crossing Gibraltar Strait: A Journey to Joy.

From Top to Bottom: Terry, Lennart and Tommi–Gibraltar Strait Oct 11, 2013

That was so enjoyable that we immediately began planning our next aqua-trek. The following week, another close friend–English Channel luminary Nick Adams–swam Corsica to Sardinia with three friends. While Nick has tackled extraordinary challenges–a double Channel crossing and an attempt at a triple–this swim was more of a lark.

Only a few had swum Corsica-Sardinia before; Nick and friends were the first to do it sans neoprene. To encourage others to follow in his strokes, Nick had prepared an entertaining and richly detailed “Corsica to Sardinia No BS Guide.” With Nick having done the legwork, and another beautiful Mediterranean strait to cross, our choice was easy.

Corsica is French and Sardinia part of Italy, making this a literally international swim. How often can you say you’ve swum not only from one land mass to another, but from one country to another? (Crossing Gibraltar we swam from one continent to another–the top of the hierarchy . . . until someone figures out interplanetary swimming.)

The Strait of Bonifacio is just 12km across at its narrowest point and unlike the English Channel and Gibraltar, currents are a non-factor. Pretty easy pickings when it comes to swimming between countries.

I booked a 3-bedroom flat in Santa Teresa di Gallura, a picturesque town with a beautiful bay for swimming . . . and a view of Corsica–shown below–that makes the idea of swimming to it almost irresistible. Joining Lennart, Tommi and me are two new friends from Barcelona, who’d swum it–wearing wetsuits–over the summer.

Terry and Tommi L and 2nd L, Lennart 2nd R with our friends from Barcelona

We all flew into Cagliari. Oops. We’d missed Nick’s recommendation to fly into Olbia–just an hour from Santa Teresa. Cagliari was a 5-hour drive. Plus Lennart’s luggage hadn’t arrived. So we took a swim and had a superb Italian (what else?) dinner. Then back to the airport. Still no luggage. So we headed north, arriving after midnight.

Lined up to begin . . . processing!

Friday morning, after sleeping til 8, we made the short walk to Santa Teresa’s central piazza. There we were delighted to happen upon a procession with women in folk garb, men in splendiferous uniforms, a marching band, a horse drawn cart with a holy statue and a priest showering all with blessings. We’d arrived in Santa Teresa, fortuitously, just in time for the annual Festa.

The day turned overcast with a strong, chill wind churning the sea into whitecaps. Seeking calmer water, we drove to Porto Pozzo, a protected inlet shown below. We swam out-and-back from the small marina at center left to the mouth of the sea at upper left. Unlike the day pictured, there was little water traffic. The water was a bit cool at 18C/64F, but comfortable so long as we kept moving.

I tried several times to call Tomasso, our swim organizer and guide but had incorrectly entered his phone number into my iPhone, mistaking the city code for Italy’s country code. We walked around town looking for his dive shop, but no luck. He emailed me late in the day–nervous at not having heard from us. We made plans to meet at his curio shop (he also owns a restaurant and a dive shop) at 10 the next morning.

Our meeting on Saturday morning was leisurely and covered only basic details of the swim: Meet on the dock the next morning at 7. Cruise to Corsica. Swim back. Free for the rest of the day, we donned our suits and headed for the bay. Instantly, we regretted not having contacted Tomasso earlier–and thus having the option of swimming Saturday.

Conditions were perfetto; Warm sun, mirror-flat water (shown in the ‘5 Guys’ photo) and a light-but-favorable breeze. The next best thing was simply to enjoy. We swam about 50 minutes in glorious conditions, synchronizing every stroke. Then an alfresco lunch at a beachside restaurant . . . why we love swim excursions.

We’d checked weather and wind forecasts several times a day since arriving. After several days of winds strong enough to noisily rattle the shutters at our flat, Saturday was the first calm day–going back to before we arrived. We hoped we wouldn’t regret ‘wasting’ it.

We awoke around 5:30 on Sunday to the sound of rattling shutters. Tomasso called us at 6:45 confirming what we already knew. The swim was off until at least Monday. Tommi and Lennart took the car and explored a bit. Just five minutes from Santa Teresa, they found this spot.

That’s Capo Testa at the end of the isthmus. In the bay on the right, a strong wind was pushing up whitecaps and rolling swells. Just steps away, in the bay on the left, the water was calm with a breeze gently ruffling the surface. The water was as inviting as it looks. For 50 fantastic minutes, we cruised back and forth in synch. Tommi and I finished by ‘racing’ 200 meters–still in synch. We felt ready. Now all we needed was a good day. We only had Monday and part of Tuesday. Fingers crossed.

Monday dawned calm with patchy sunshine. It was our day. Around 7:30 am we left the dock on Tomasso’s boat for Corsica.

Leaving the harbor on our way to Corsica.

Our crew included Tomasso at the helm, Domenico, a local MD who came along as medical officer, and my wife, TI Coach Alice Laughlin, to take video and photos. All three prepared our hydration and feeds. As this would be a relatively brief swim–we anticipated between 4 and 5 hours–I brought only water, a banana and a few packs of energy gel.

L to R: Medical Officer Domenico, Captain Tomasso, First Mate Alice

We left the boat and swam to shore. Once on the beach, we stood clear of the tide line–the customary way to start a marathon–waved a hand, and began. By plan, we’d swim for an hour prior to our first feed, then feed at 30-minute intervals.

As I often do, I felt ambivalent in the early going: Do I really want to do this? Am I ready? Will some unexpected impediment arise? After we finished, Tommi said his thoughts at that point had mirrored mine.

I banished distracting thoughts with the reliable cure of focus–trying to make every stroke the best it could be. Synchronizing with Tommi and Lennart took more focus than usual too.

We’d synchronized with little difficulty during our Gibraltar swim. But during our practice swims the previous three days, it was evident that Tommi had gotten faster, while Lennart had lost some speed. However, Lennart swam straighter which evened things out.

Tommi, while the fastest among us, was also more subject to chilling. Slowing his pace would make that more likely. Tommi solved it by periodically veering to the east, then tacking back toward us, covering more distance at a brisker pace. Sometimes I went with Tommi; sometimes I stayed with Lennart.

One of my concerns was real though. In September, I’d been forced to drop out of a 10K at Coney Island after two hours and 6K of swimming, because I couldn’t pee. I was fine the first hour, but during the second hour, no matter how hard I tried, nothing came forth–even when I stopped for water at 5K. Once I got out, the bottleneck cleared. It might have been the water temperature–about 65F–but I’d swum much longer in colder water many times before (including Gibraltar) without a hitch.

My worries were confirmed about 40 minutes in. Consequently I refused water at the 1-hour mark and again 30 minutes later. I made up my mind to just swim from feed to feed, as long as I could, and hope the problem would resolve somehow. And as is nearly always true, the feed stops came with surprising speed. Often it seemed as if we’d only been swimming for 15 minutes when they beckoned us to the boat.

But my discomfort increased steadily. At the 2-hour mark I conceded that I couldn’t swim any longer this way. I exited the water and thought my swim was done. Indeed by the rules of marathon swimming, even touching the boat is grounds for disqualification.

Happily after a couple of minutes on the boat I–well there’s no delicate way to put this–I peed copiously and felt complete relief. For a moment I wondered if it was kosher to resume swimming. “Why not?” I thought. “You came here to swim Corsica to Sardinia. Now do it.”

I jumped back in. Lennart and Tommi were 60 meters ahead, but within a few minutes I’d caught them. I repeated this two more times, at 1-hour intervals.

The only time we looked to see how far we’d swum or how much remained, was during our feeds. But with each stop, our steady progress toward our destination was evident and we had a growing sense of excitement as the 3-hour mark passed. “Just two more feeds,” we said. Counting down feeds is a common way for marathoners to mark progress toward the finish line.

At our 4-hour feed, Tomasso asked where we preferred t finish–at the nearest landfall, a rock face a short distance away, or swim a mile farther to finish on the beach below Santa Teresa. It was an easy call: We’d finish on the beach.

In the final kilometer, Tommi and I picked up the pace, replicating the ‘races’ we’d had at the end of our practice swims–yet staying closely synchronized as we did. A short distance from the beach we pulled up, so we could finish all together. Below see the final minute or so before we stopped.

And listen to the conversation, around the 1:00 mark where Tommi says “So fun.” Eloquently said, Tommi. If it’s not fun, why do it?

Mission Accomplished. Back at the dock, we toast our swim. What waters beckon next?

When we reached the beach, Tommi and Lennart checked their gps watches: We’d swum 15.5K in 4:31, including our feed stops. A bit short of the unofficial record set by Nick Adams and friends of 4:22.

One thing that surprised me was how good I felt over the final mile. On a swim that long, I should have drunk at least 1.5 liters of water. But, fearful of ‘pee backup,’ I took only a couple of quick swigs of water, 4 to 6 oz. total. I never felt the need for an energy gel, but I ate a banana, in small bites over several stops. Still, I felt fresh and fast at the end. Swimming in synch with Tommi, I felt like the Energizer Bunny-fish.

Before leaving Sardinia we discussed options for our next swimming trek. Croatia, Mallorca, the Atlantic coast of Morocco, and Arizona’s Lake Powell are all options

And the Corsica-to-Sardinia record of 4:22 is just waiting for someone to better it. Whether to break a record or simply to have as brilliant an overall experience as we did, if you’d like to swim the Strait of Bonifacio–before crowds of swimmers discover and descend upon it–Nick has kindly agree to let us share his No BS Guide with you. Download here.

To prepare for doing so, you might consider attending a TI Open Water event, as Lennart and Tommi did. Upcoming events include:

January 3-8, 2016 – Open Water Experience – St. John, U.S.V.I. - details

January 31- February 5 , 2016 – All Women’s Open Water Experience – St. John, U.S.V.I. - details

February 25-29, 2016 – Triathlon Swim Camp (pool and open water) – Clermont, FL – details

March 7-12, 2016 – Open Water Experience – Kona, HI – details

The post Corsica to Sardinia: A ‘Bucket List’ Swim appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 6, 2015

Can It Get Any Better Than This?

On Tuesday of this week I returned home from a trip to Italy and England. On the first leg of that trip, (Oct 19) I swam Corsica to Sardinia. I’ll recount that in next week’s blog.

That evening, I read the New Yorker magazine article, WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE RUN, a review of “Poverty Creek Journal” a collection of reflections from a year of running. It also summarized a study published in the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Sports psychologists gave clip-on microphones to 10 distance runners and asked them to narrate their thought process during a run.

What did these runners think about?

How hard it was to move at their desired speed: “Come on, keep the stride going, bro.”

How soon they could stop: “Come on, you have enough energy for a mile and a half.”

How miserable they felt while running. In the words of the researchers: “Pain and discomfort were never far from their thoughts.”

I’d previously given little thought to what runners think about–other than pondering that if more runners were exposed to the sensuous pleasures of moving like water, they’d become swimmers instead. Reading this made me wonder, why do people carry on with such a masochistic exercise. The contrast with my practice from just a day earlier could not be more stark.

As it always is, my practice was guided by principles of TI Fast Forward training methodology . . . which come, in turn, from the principles of Deliberate Practice and Mastery:

1. Always focus on improving your swimming.

2. Create feedback loops. These can be subjective (Focal Points) or objective (SPL, Tempo, Time).

3. Design practice tasks as problem-solving exercises. E.G. Holding Stroke Length, while increasing Stroke Rate–the ‘Algorithm of Swimming Success.’

Monday morning, six hours before flying back to NY, I joined Sean Haywood (he swims for TI UK Coach Tracey Baumann in Windsor) for a swim at the Hampton Lido, an outdoor 36-meter pool. Having never swum in a 36m pool–have you?–I went in with no idea what stroke count or pace I should aim for.

But that’s never a problem. I can ‘create meaning’ in any pool, simply by counting strokes during my Tuneup. So that’s what I did.

Swimming with a feather-light catch and barely-there kick, I took 24 strokes the first length, then added a stroke on each of the next three laps–reaching 27 SPL on the 4th. (I later did a calculation and found that the Green Zone for my 6-foot height in a 36-meter pool should be 24 to 28 strokes.) As my sensitivity to the water increased, I shaved a stroke bringing me to 26SPL then held that consistently for another 10 to 12 minutes. This gave me my first data point.

Moving into the ‘fast’ lane, I turned on my Tempo Trainer. It was set to 1.17 sec/stroke from a previous practice. I figured that was as good a place as any to start so I tucked it under my cap and swam 4 lengths (144m), counting strokes. I averaged 27 SPL. That gave me a second data point. I could comfortably hold 27 strokes in a 36m pool at 1.17 tempo.

That suggested two possible problem-solving exercises:

Could I swim farther at that Tempo and SPL ? I could test this with a series of repeats-each one length farther than the previous (swim 5 lengths, then 6, then 7, etc ). This would be an endurance and steady pacing exercise.

Could I swim faster, by maintaining an efficient stroke, while incrementally increasing tempo? This would be a Smart (and Easy) Speed exercise.

I chose the latter and decided to swim a Tempo Pyramid. I would swim a series of 4-length (144m) repeats, slowing tempo by .02 on each until my SPL returned to 26–or 104 strokes for a 144m swim. I reached that at 1.23 tempo–25 strokes on the 1st length, 26 strokes on the 2nd and 3rd and 27 strokes on the 4th.

Then I reversed tempo, increasing by .01 sec after each 144m rep. My objective was to avoid adding a stroke for as many repeats–and .01 tempo increases–as possible. I held 26SPL for 11 reps–reaching a tempo of 1.13 sec/stroke–before my stroke count went up.

The ‘Math of Speed’

By maintaining 104 total strokes while tempo increased by a tenth of a second, I improved my pace for each 144m repeat by 10.4 seconds. Yet I’d never tried to swim faster. In fact my thought process was just the opposite: To stay very relaxed–and even maintain a sense of lightness and leisure in my stroke–as tempo steadily increased. The fact that my tempo changes were quite minute–just a hundredth of a second–made it easier to adapt.

When I finally exceeded my target SPL at 1.12 tempo, I modified the set to 3-length (98m) reps and held my 26SPL average (25-26-27 strokes) until I reached 1.09.

At 1.08 my SPL rose again, so I cut another length from my repeats, carrying on with 72m repeats, holding 26 SPL to 1.06. At 1.05, in order to hold 26 SPL, I cut another length and finished my practice by holding 26 strokes for four 36 meters taking me to 1.02 sec/stroke. Allowing 3 seconds for pushoff, at 1.02 and 26 strokes, I crossed the 36-meter pool in 29.5 sec. At 1.23 tempo and the same number of strokes, each 36-meter lap had taken 35.7 seconds.

Better than Ever . . .

If a researcher had given me a waterproof mic and asked me to record my thoughts between repeats, I’d have reported feeling a nearly-blissful Flow State the entire time–a product of a problem-solving exercise that required unblinking focus on every single stroke. In other words, I was Totally Immersed in the process of swimming at high efficiency.

And how did I feel physically? Fabulous! As my 36-meter pace improved by 6 seconds, my movement through the water felt better and better–more integrated, more fluent. During the closing lengths I literally felt the best I ever have in 50 years of swimming.

Can it get any better than that?

The post Can It Get Any Better Than This? appeared first on Total Immersion.

What We Think About When We Swim

On Tuesday of this week I returned home from a trip to Italy and England. On the first leg of that trip, (Oct 19) I swam Corsica to Sardinia. I’ll recount that in next week’s blog.

Tuesday evening, I read the New Yorker magazine article, WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE RUN. It was mainly a review of “Poverty Creek Journal” a collection of essays on a year’s worth of runs. It also summarized a study published in the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Sports psychologists gave clip-on microphones to 10 distance runners and asked them to narrate their thought process during a run.

What did these runners think about?

How hard it was to move at their desired speed: “Come on, keep the stride going, bro.”

How soon they could stop: “Come on, you have enough energy for a mile and a half.”

And quite often about how miserable they felt while running. The researchers summarized: “Pain and discomfort were never far from their thoughts.”

I couldn’t help but wonder why people carry on with such a masochistic exercise. And then I thought: If they knew how it feels to practice Kaizen Swimming, would they give up running? Or would they run differently–the way ChiRunning teaches?

In any case the contrast between the runners in this study and the practice I’d done just a day earlier could not be more stark.

Before I describe my practice, I’ll review several principles of TI Fast Forward training methodology:

1. Always focus on improving your swimming.

2. Create a feedback loop-either subjective (Focal Points) or objective (SPL, Tempo, Time). If the latter, use two metrics. Tempo+SPL or Tempo+Time or SPL+Time.

3. To swim faster, design problem-solving exercises that strengthen your ability to hold Stroke Length, while increasing Stroke Length. We call this the [I]’Algorithm of Swimming Success.'[/I]

On Monday morning, six hours before flying back to NY, I joined Sean Haywood (he swims for TI UK Coach Tracey Baumann and was among 27 members of her training group who went with Tracey to Ironman Mallorca the previous month) for a swim at the Hampton Lido, an outdoor 36-meter pool. Having never swum in a 36m pool, I went in with no idea what stroke count or pace I should aim for.

But that’s never a problem. I can ‘create meaning’ in any pool, just by counting strokes during my tuneup, which I swam in the ‘medium speed’ lane.

Swimming with a feather-light catch and barely-there kick, I took 24 strokes the first length, then added one stroke on each of the next three laps–reaching 27 SPL on the 4th. (I later did a calculation and found that the Green Zone for my 6-foot height in a 36-meter pool should be between 24 and about 28 strokes.) When the ‘tuneup effect’ began to take hold, I shaved a stroke bringing me to 26SPL. I swam continuously for another 10 to 12 minutes, holding quite steady at 26SPL (except when I overtook another swimmer and sped up to pass).

Feeling ready for a challenge, I moved into the ‘fast’ lane and turned on my Tempo Trainer. It was set to 1.17 sec/stroke. I figured that was as good a place as any to start. I swam 4 lengths (144m) continuously, and averaged 27 SPL. Armed with that information, I decided to swim a Tempo Pyramid, slowing tempo by .02 each repeat until my SPL returned to 26–or 104 strokes for a 4-lap, 144m swim. I reached that at 1.23 tempo–25 strokes on the 1st length, 26 strokes on the 2nd and 3rd and 27 strokes on the 4th.

Next I would test how long I could hold this stroke count, while increasing tempo by .01 sec after each rep. I held this count for 11 reps–to a tempo of 1.13 sec/stroke. Doing the math, my pace at 1.13 tempo–and the same number of strokes–was 14.4 seconds faster than at 1.23 tempo. Yet I’d never tried to swim faster. I simply executed strokes of consistent quality while making minute increases in tempo.

At 1.12 I exceeded my target count so on the next rep, I dropped down to 3-length (98m) reps and held my 26SPL average (25-26-27 strokes) until I reached 1.09.

At 1.08 my SPL rose again, so I cut another length from my repeats, carrying on with 2-length (72m) repeats, holding 26 SPL to 1.06. When my stroke count rose above 26 again, I cut another length and finished my practice by holding 26 strokes for 36 meters from 1.05 to 1.02 sec/stroke. My final length was 27 strokes at 1.01.

If a researcher had given me a waterproof mic and asked me to record my thoughts between repeats, I’d have said I was in a nearly-blissful Flow State the entire time, from focusing on every single stroke . . . Totally Immersed in what I was doing.

And how did I feel physically? Fabulous! As I swim steadily faster, my movement through the water felt better and better–more integrated, more fluent. And the overall effect produced a highly satisfying Flow State.

Can it get any better than that?

The post What We Think About When We Swim appeared first on Total Immersion.

October 30, 2015

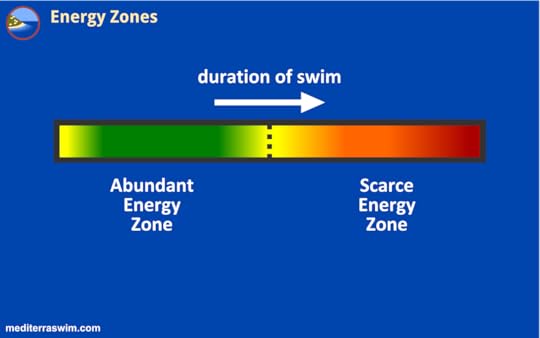

Swimming in Your Scarce Energy Zone

Maintaining best form when energy is abundant is a great Level 1 accomplishment. That is really a good functional goal for recreational swimming, and that may be as far as some want to go – those who don’t intend to swim under any sort of metabolically stressful conditions (think ‘getting tired’ in open water, long distance, racing, etc).

But if one intends to swim with good form (shape) under stressful conditions then he must train to hold good form under those conditions.

Let’s divide a swim into two zones – the Abundant Energy Zone and the Scarce Energy Zone.

It is challenging at first to develop superior form for the first time – while in that private lesson or workshop we may have an abundance of physical energy but the brain is really taxed while building new motor circuits for these new body positions and movement patterns. Eventually, those get ‘hard-wired’ into the brain (automation) and one can keep working on them for hours with relatively low physical energy demand. To make it easiest to build those new circuits for the first time our learning method deliberately limits swimmers to working within the Abundant Energy Zone. When energy gets scarce the brain and body will compete for the diminishing energy – often the old physical patterns take over again and are reinforced, while the new patterns are neglected.

~ ~ ~

To read more of this article – Swimmer Speed Curve – Part 4 – visit Coach Mat’s Smooth Strokes Blog.

The post Swimming in Your Scarce Energy Zone appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers