Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 17

August 12, 2016

What Can You Learn from Katie Ledecky?

Tonight, Katie Ledecky swims the final of the 800 meter freestyle at the Rio Olympics, an event in which she owns the top 10 or so performances in history, and in which her closest competitors will probably be far behind by the halfway point.

As yesterday’s NY Times article Long Swims Are Boring? Not When Katie Ledecky Is Racing the Clock notes “The distance freestyles used to be swimming’s equivalent of baseball’s seventh-inning stretch: a convenient time to take a commercial break or make a trip to the restroom or concession stand.”

No more. As with millions of others, Katie’s race will be “can’t-miss TV” for me. And I hope for you too. Not only for the thrill and inspiration of seeing her break a world record, but for what you can observe about her form and apply to your own swimming.

TI and the Olympics

This week I’ve been invited to comment on Olympic swimming on two occasions. On Monday, I appeared on the public radio program The Takeaway, to talk with host John Hockenberry why the US is so good at developing Olympic medalists and horribly ineffective at teaching beginners.

http://www.totalimmersion.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/takeaway080816-swimming.mp3

On Thursday I joined Slate sports editor Josh Levin for a podcast to explain the techniques that make Michael Phelps and Katie Ledecky so special–and seemingly so different from the rest of us.

http://www.totalimmersion.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/SM1896432112.mp3

But you can swim more like Katie than you think, by studying these aspects of her technique this evening then emulating on your next pool visit:

Head Position and Breathing (i) Her head is quite low in the water and aligned with her spine–though I think she could do even better with this. If you study TI video, you’ll see even less of the head visible above the surface. (ii) She breathes inside the bow wave, often with only on

e goggle above the surface and water at the corner of her mouth. (iii) When she breathes, her head moves in synch with her body not independently. Compare my breathing position–at super-easy pace–with Katie’s–swimming super-fast–at the same point in the breath.

Stroke Length. As I wrote in last summer’s blog Swim like Katie Ledecky? You Can! the most obvious (and measurable) advantage Katie has over her peers is a longer stroke. Click to read ‘secrets’ of Stroke Length.

Streamlined Kick Katie will probably use a 2-Beat Kick (the one TI teaches for distance and OW swimming) during parts of her 800m race (she uses it for most of her 1500m), before shifting to a 6-Beat Kick for extra speed near the end. In either case, her kick will be controlled, integrated with core-body movement, and–most of all–streamlined. No matter how she kicks, her legs will remain in the ‘slipstream’ behind her upper torso.

Katie in Flow

My favorite aspect of Katie’s swimming–and the one I consider most significant–is psychological, not physical. She takes a zen-like enjoyment in the wonderfulness of how her stroke feels. This was best illustrated by her attitude while racing at a low-key meet in June 2014. I wrote about it in the blog Zen and the Art of Breaking World Records.

Learn both the physical and psychological skills that make Katie a 1-in-7,000,000,000 phenomenon with TI Self Coaching Courses–the Freestyle Mastery course if you’re a TI vet; the Ultra-Efficient Freestyle course if you still have a lot of upside potential in efficiency.

The post What Can You Learn from Katie Ledecky? appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 5, 2016

Zero Cancer Swimming: The Physical Becomes Metaphysical

Friends

I would love to take credit for the title of today’s blog. However, my devoted student and friend, Jeanne Safer, said it as we talked about how what had once been purely physical/fitness activities had become transformed as I discovered that they created a Zero-Cancer Zone in which real healing occurred.

This is my first Zero Cancer blog since March. For several months, my condition seemed to change almost weekly, and I wanted to wait until it stabilized, and I could make some sense of it, to share it with you. That time has come.

Here is a brief summary of news I’ve received in the last eight months:

Nov 20: “You have prostate cancer.”

Jan 23: “Your cancer has metastasized to your pelvis and seminal vesicles.”

Apr 21: “Your cancer has become hormone-resistant after two months.” (The norm is two years.)

Apr 27: “It looks as if you had a small stroke earlier this month.”

Following my initial diagnosis, I experienced a funk. Surprisingly, it lasted only 15 minutes. Partly because the urologist had soft-pedaled it, saying: “Prostate cancer is slow-moving and very treatable.” (I now wish he hadn’t.) I had recently set ambitious goals for my first season as a Masters swimmer in the 65-69 age group in Masters swimming and I was nearly as concerned about how treatment might affect my training plans as about having cancer.

But updates which followed were considerably more sobering. After each I experienced emotions ranging from “Why me?” to terror. At the same time, I was keenly conscious that my prospects for remission would depend heavily on my ability to maintain a strong spirit and a belief in my ability to prevail.

But I found I had the resilience to work my way back to a sense of optimism after each. I took a Deliberate Practice approach to facing challenges for which nothing else prepares you. Each challenge taught me something about regaining calm, and prepared me for the next.

I was also uplifted repeatedly by the love, care, and prayers of countless people whose own lives had been touched by TI. And, through them, I’ve also been introduced to some of the world’s top prostate cancer specialists.

My evolving prognosis has been accompanied by a parade of symptoms, one following another. I felt great—and had just finished a fantastic Corsica-Sardinia swim—when I received my initial diagnosis. I still felt great the first week of January as I coached at our open water camp at St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. However, within weeks I began to feel ill, and by mid-February, I felt sick every day.

After my first testosterone-suppressing hormone injection Feb 11, I improved dramatically, to the point where I was able to coach at our Tri-Swim camp in Clermont the last week of Feb. Being there was itself strong medicine. The first two weeks of March I felt truly vibrant health—to the point where I could almost forget about cancer. During this period I trained exceptionally well and swam the thrilling 1650 race recounted in 1390 Seconds of Unwavering Focus.

A Downward Turn

By the time I had my second injection Mar 16, my sense of health had begun to decline. When I received my third injection in mid-April I was again feeling quite sick. I had an inkling the hormones had lost their effectiveness, even before the oncologist confirmed a day later that my PSA, which had dropped from 29 to 5 after the first injection, had risen to 21 by the time of the third.

That month, I was thrown another wild card after suffering a 26-hour spell of acute dizziness, which started while giving a lesson in our Swim Studio. After being examined by my doctor, I had a brain scan a week later. On April 27 a neuro-oncologist at Mt. Sinai, after reviewing test results, told me I’d had a small stroke, most likely related to the cancer.

I’d recovered from the dizzy spell with no apparent ill effects. But, soon after, I began to experience unsteadiness on my feet and blurring vision. Every few days, each of those conditions—particularly the deterioration in my vision–seemed slightly more advanced than before. It was becoming harder to read my computer monitor as I worked, and I was limited to driving short distances.

This momentarily sidelined my concerns about cancer. I discovered I was less worried about dying than by the prospect of being robbed of function and the ability to move around freely and do my work. In the weeks that followed, the advance of these symptoms caused the highest level of anxiety I’d yet faced.

I’d planned to drive to Greensboro NC and swim in Masters Nationals the last week of April. But vision problems made a long drive out of the question and I’d begun to feel far too ill—along with constant pain in my hips–to withstand the rigors of the trip or racing. Instead I began chemotherapy that week.

While you seldom hear of people speaking positively about their chemotherapy experience, I welcomed it. On the day of my first infusion, my daughter Betsy and I left New Paltz to drive to Manhattan at 5:30 am. During the 2-hour drive, I maintained a positive and expectant attitude about the healing potential of the medication I was about to receive. The initial infusion took 3 hours, during which I relaxed in a comfortable recliner and engaged in self-hypnosis and meditation, telling my body “This medicine is a life-saving partner. We will work together.”

I’ve now had five chemo treatments, at 3-week intervals, during which the pain in my hips has declined to being quite tolerable, though still an occasional distraction. My sense of overall health has mostly been quite good. People who learn I have stage IV cancer nearly always tell me it’s hard to square with my healthy appearance.

The 5-year survival rate for metastatic prostate cancer is 28%. However between 5% and 10% stretch that to 10 or even 15 years. The strongest predictor for being in that group is one’s state of health at the time of diagnosis. Mine had been great as I was just coming off a very strong 10-mile Corsica-Sardinia swim.

The key to resisting the advance of cancer is the strength of one’s immune system. The greatest threat to that is the anxiety I spoke of earlier. My anxiety began to increase as my vision deteriorated,. This accelerated when I learned my cancer had become hormone-resistant, which my oncologist described as “the far side of bad news.”

Something else that spiked was my blood pressure—to a scary 190/101 during an oncologist appointment on April 21. Hypertension caused my vision to deteriorate further, and raised my fears of another stroke. Following that appointment I determined to use mind-over-body measures to bring my BP down to the 120/70 range.

Over the next three weeks, using daily qigong, meditation, and visualization; healthy eating; and up to five yoga classes per week (because of vertigo I wasn’t swimming at the time) my BP dropped steadily to a level lower than it had been in over 30 years. As it did my vision and steadiness on my feet improved. This felt like the most important accomplishment of my life. It also increased my confidence that I could use the same strengths to slow cancer growth.

For a few weeks I felt upbeat and healthy. But then, between June 10 and 12, I had daily anxiety attacks, and blood pressure levels so high that each of those days I considered going to the ER to have my BP medically reduced. This also caused my vision to deteriorate again. On June 14, my doctor changed my anti-anxiety meds, transitioning me from Xanax to Lexapro, which has more permanent effects.

I Regain my Sense of Self

On June 18, Lake Minnewaska reopened for swimming. As the date approached, I was excited about swimming where I’ve experienced so much joy, but also nervous: Would vertigo return? Could I tolerate the 68F water? (I’d been prone to both overheating and chilling since starting hormone treatment.)

My first 400m loop dispelled all my fears. It felt like absolute bliss and brought a flood of pleasant memories. By the start of my second loop I was swimming with an ear-splitting grin. Though I hadn’t swum in six weeks, I continued for 2000m, coming out pleasantly fatigued.

That day marked the beginning of the most pronounced upswing in my state of physical and mental health. Since then I’ve swum regularly, at Minnewaska and the outdoor 50m pool in New Paltz, complementing three to five weekly yoga classes.

In early July I saw a program on Australian TV which reported on a rigorous study in which cancer patients who undertook a targeted exercise program–including a weight workout on the day of treatment–doubled survival time compared to those who did not exercise.

This resonated because because I’ve always enjoyed using my body in a physical way and I’d felt vibrant health during and immediately after every yoga class or swim practice. While looking in the yoga studio mirror while doing, say, Warrior 1 pose, I could see a smiling and healthy individual looking back at me.

I’d stopped lifting weights in late April when I felt poorly. Since then, because my hormone treatments suppress testosterone, I’d lost a shocking amount of muscle mass and strength. This treatment greatly increases risk of osteopenia/osteoporosis. And because chemotherapy leaves dead bone cells in place of tumor cells, men with my cancer often suffer fractures.

Thus, I resumed strength training two weeks ago. In just four training sessions, I’ve already seen a return of tone to muscles that had shrunk and grown flaccid. I’ve also enjoyed the feeling of mindfully overcoming resistance. The physical has become metaphysical–activity that impacts the very core and nature of my being. I’ll write more in the very near future how that came about, but it started in earnest when I began practicing qigong in April.

The most exciting development of all came in the past few weeks. From the time of diagnosis, awareness of cancer had become a full-time preoccupation that weighed down my spirit every day. However, from mid-July on, my spirit has become light and I’ve experienced periods of profound joy nearly every day. In part I attribute this to new medication finally taking effect. But also it is due to the Kaizen habits I’ve learned from TI practice. Both are allowing me to regain my sense of self.

I strive to live each day as fully as possible, and to use each moment and action to strengthen my spirit, mind, and body. How much life extension I can achieve is in my hands, more than in my doctors’. Each year I can add will bring advances in treatment options. This week, I read about promising immunotherapy discoveries that will come to market in the coming year.

In addition to what I’ve described here, the two factors that will make the biggest difference are that I have a lust for life, and feeling that I have much important unfinished work. In my next post, I’ll write more about the latter.

May your laps, and life, be as happy as mine.

Terry

The post Zero Cancer Swimming: The Physical Becomes Metaphysical appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 1, 2016

Become One With The Water (Guest Post)

Coach Scott Lemley talks about “feel for the water” and how it can be learned. He’s coached swimming at four levels: club (38 years), college (17 years), high school (17 years) and masters (10 years). He’s an accomplished masters swimmer having won the Sri Chinmoy La Jolla swim-run at the age of 40 with his 36 year old training partner, a marathon runner of some repute. Their combined ages was nearly twice that of the 2nd place finishers. Lemley is a member of the U.S. Martial Arts Hall of Fame and patented the fistglove stroke trainer 25 years ago.

When athletes talk about being “in the flow” they often describe that feeling as being “effortless”, moving with a sense of beauty and grace. Watch Roger Federer play tennis and notice how he glides across the court, completely fluid, never in a hurry, yet deceptively quick with both his footwork and his hands. Great tennis players “in the zone” say the ball looks huge and time slows to a crawl. They’re able to get to the part of the court exactly where they need to be BEFORE the ball gets there. Then they make perfect contact with that tiny sphere which is traveling 100 miles an hour and is both spinning around its axis and either curving towards them or curving away from them. They do this hundreds of times in a match and make it look easy.

For golfers the task at hand is very different; the golf ball, though much smaller than a tennis ball, doesn’t move at all. What great golfers need is the ability to see the perfect line from the ball to the hole, often 400 yards in the distance over hills and through trees. They must hit the ball and shape its flight during conditions which at times are both windy and rainy. When they’re on, these players only need to strike the ball once in order to roll it into a cup nearly a quarter mile away. Being a successful golfer requires a very different kind of zone than a tennis player yet it’s still understood at the highest level as attaining a “state of flow”, being one with the game.

Basketball players refer to how huge the rim seems when they’re “in rhythm” and can drop the ball straight through the hoop touching nothing but net, over and over again, from any spot on the court, all the while being pushed, shoved and blocked by other 6 foot 6 inch 250 pound supremely gifted athletes in the process.

How do we explain the ability these athletes demonstrate? Is it extreme talent? Is it the product of decades of nearly constant and perfect practice? I think it’s a combination of a thoroughly practiced physical skill, an uncommon degree of focus and a high level of sensory perception. We might say they have “the touch”. Oddly, “the touch” is as universal a term as it is elusive. Universal in that some people have “the touch” for everything from making money to producing hit records. Or throwing an unhittable baseball at a batter 60 feet away. And elusive in this respect – though many of us may have experienced having “the touch” or “being in the zone” at least once in our lives, understanding how we got there and knowing how to get back seem nearly impossible.

I’ve coached swimming for close to 40 years and almost every swimmer I’ve ever talked with has related to me at least one time in their lives when a race felt completely fluid and smooth, when they were “in the flow”. They didn’t talk about their power or their conditioning; they talked about how “effortless” it felt. They didn’t try hard. In fact, some said they didn’t try at all. I’ve asked all of them if they ever felt like they were “one with the water” and most said that was an apt description though their state often defied further explanation. I believe being “one with the water” is the result of a level of mind and body coordination which is not the ordinary focus of the common swim practice. I learned many “mind and body” exercises through my years practicing Aikido and one in particular helped me understand how to become “one with the water.”

At the highest level, martial artists seem to defy gravity, ignore normal human speed limits and exhibit extraordinary reflexes. They can draw a sword, cut a fast moving ceramic pellet shot from a rifle in half and sheath that sword in the blink of an eye. They can reach out and catch an arrow out of the air. And while those are certainly the flasher movements one can see in a martial arts demonstration, there are other, more subtle benefits which I found just as powerful. I learned how to heighten my sense of touch, both internally and externally. This kind of body awareness is known as the state of kinaesthesia and encompasses three main sensations: the sensations of position and movement of joints; the sensations of force, effort and heaviness associated with muscular contraction; and the sensations of the perceived timing of muscular contractions. I first learned this by practicing martial arts while blindfolded. By masking one sense, especially sight, the other senses are heightened, senses like touch, hearing and balance. I was a martial arts instructor before I became a swimming coach and it wasn’t long after I started coaching that I asked myself if there was a swimming analogy for how crucial sight was to the practice of martial arts. I believe it’s how the hands grab the water. To a great extent, that’s where the rubber meets the road for swimmers. So I blindfolded my swimmers’ hands in various ways over the space of several years and started to see some amazing changes in their ability to feel the water.

It’s been known for a long time that sensory inputs from the skin are crucial for normal motor behavior, that their importance in both kinaesethesia and motor control has a strong connection. I could write about neuroplasticity and how quickly the brain compensates for lost senses but the truth is I’m not a neuroscientist and I can’t quote a single study about the specific roles cutaneous inputs play during motor behavior. I can quote a great number of coaches and swimmers who have experienced this heightened sense of touch after using a pair of fistgloves. John Leonard, Executive Director of the American Swim Coaches Association, described their use as resulting in a “. . . surprising and dramatic change in the hands’ sensitivity . . .” likening the effect to “voodoo” and suggesting that some day sports scientists will figure out why wearing fistgloves produces that effect. “As usual, coaches are ahead of the curve in figuring out why things work long before the eventual scientific explanation” he said.

The fistglove is a dual-use teaching aid. First, when they’re worn they take a swimmer’s hands out of the “balance” and “propulsive” equations. The hands are often “misused” to create balance. I believe hands should be used primarily to propel. By wearing a slick latex covering on the hands and turning them into small, slippery, ball-shapes, they become utterly useless for balancing OR propelling the swimmer. Swimmers must create a balanced state through body position. At the same time, the only way for swimmers to propel themselves forward is to employ the “under utilized” surface area of the forearms. The highly innervated skin of the hands compels swimmers to focus mainly on the end of the lever-arm, the hand, for propulsion. The skin on the forearm, though not nearly as sensitive to the pressure of the flow of water as the hands, is in fact much greater in area than the hands. When wearing fistgloves the hands are “cloaked” thus making it easier for swimmers to become aware of the position of the forearms vis a vis creating propulsion and results in accentuating the “high elbow” posture underwater. When the fistgloves are taken off, the hands become uncommonly sensitive to the forces of the water’s pressure allowing for very precise placement and a very precise degree of force application. This insures the hand-forearm lever has minimal backwards movement, or what coaches and swimmers call “slipping.” After wearing a pair of fistgloves swimmers experience just the opposite of slipping, what Terry Laughlin, the founder of Total Immersion, calls The Fistglove Effect.

In his latest book, Freestyle Mastery, Terry says “The first time I used fistgloves, I experienced transformative change in awareness. As I wrote at the time, it felt like “Alexander Popov’s hands had been magically grafted onto my arms.” Why get used to training with paddles when you feel so ineffective when you take them off? With the “fistglove effect” Terry says, “What could be better than a practice aid that makes your ‘normal equipment’ feel extraordinary?”

The great historian and member of the International Swimming Hall of Fame and the coach of World

Record holders on three different continents, Cecil Colwin, was an enthusiastic promoter of “clenched fist swimming”. After using a pair of fistgloves he said their use “. . . almost miraculously enhances sensitivity to the flow on both the palm and the knuckle-sides of the hand, a reaction that is quite unique, and will doubtlessly cause considerable excitement among coaches who are serious about improving the fluency and dexterity of their swimmers’ stroke mechanics.”

What kind of stroke mechanics could your swimmers learn if they were “aquatic sensory geniuses”, if during every practice one of their goals was to become one with the water?

For years the phrase “aquatic motor genius” was used to describe talented swimmers like Mark Spitz. His ability was unprecedented and he reportedly was able to break World Records in practice. He was an NCAA qualifier in every distance from the 50 free to the mile. He certainly wasn’t the biggest, strongest swimmer in the world but his feel for the water was considered off the charts. This elusive “feel” has been the source of debate for a long time. Can you teach it or do you have to be born with it? I’m not sure you can teach it. I AM sure it can be learned.

I believe the mind leads the body. I believe becoming an “aquatic sensory genius” must occur before you can become an “aquatic motor genius.” Try the fistglove, the world’s first true proprioceptive training aid and BECOME ONE WITH THE WATER.

Click Here to Order Your Pair Today!

The post Become One With The Water (Guest Post) appeared first on Total Immersion.

July 29, 2016

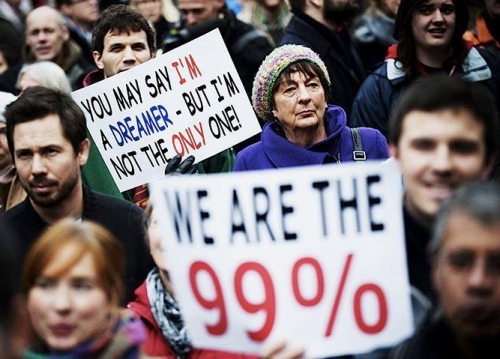

Total Immersion: Swimming for The 99%

The end of the presidential primary season, with the two parties’ nominating conventions the past two weeks, has gotten me thinking about some of the slogans we are likely to hear with frequently during the three months between now and Election Day, Nov 8. One that we are likely to continue hearing long after November, is: “We are the 99%.” Well, swimming has a 99% too, and if you read this blog, you’re highly likely to be in it. In fact I’ll bet that 99% of you are members of Swimming’s 99%.

Are you in Swimming’s 99%?

Are you self-coached 99% (or more) of the time? – Swimming in a group with a coach on deck doesn’t disqualify you. For each hour you swim with a coach on deck do you receive at least 30 seconds of effective coaching input about how to swim better? If not–though the coach may prescribe sets–you are essentially self-coached 99% or more of the time.

Do you practice solo all or most of the time, rather than with a group? Or if you do swim with a group, it’s an informal one, you with a friend or several pool buddies, as much for the camaraderie as because you want to be pushed by others.

Do you swim mainly for quality of life, the quality of your swim experience, and because you feel happier and healthier during and after . . . even if you sometimes participate in a competitive event of some kind–a triathlon, open water swim, or Masters meet?

Do you look forward to swimming for the rest of your life, rather than for a planned and finite period followed by ‘retirement’ to something with fewer demands or pressures–or simply that’s not swimming?

If one or more of these is true, then you are a member of swimming’s 99%–those who swim more for intrinsic reasons than external goals, and are mostly self-directed. My best guesstimate is that this describes 99% (or more) of all swimmers–though the greater visibility of the 1% can create an impression of them as greater in numbers and as having more ‘important’ goals.

Who is in Swimming’s 1%?

Well, I was for 25 years, from age 14 to nearly 40. From 14 through 20, all my swimming was in coached workouts and had but one purpose: To prepare for my next race. From 20 to my late 30s, I coached competitive swimmers. I still swam, but irregularly. I found I did my best workout-planning while swimming. But my mindset remained narrow: Swimming was about speed and endurance, not quality of life. I wasn’t focused on improvement; I thought my best swimming was far behind me.

During those years I gave little thought to the prospect that swimming might be a source of daily joy and play a completely holistic role in my life, two to four decades later.

Today I remain just as avid a competitor–if not more so. But 99% of my swimming occurs in practice. The Masters and open water races in which I compete account for only 1%. So, naturally, I focus on the 99%–striving to make it deeply pleasurable in the moment and the wellspring of the physical and psychic energy that helps me be at my best the rest of the day. That way of thinking places me firmly in Swimming’s 99%,

TI: The Swimming Method for the 99%

The origins of TI made it only natural that our focus would be on the 99%. It might not have seemed that way in the early days, since the summer swim camps we offered our first few years were aimed mainly at Masters swimmers, and our most rapid growth phase, in the early to mid 90s, was mainly due to a large influx of new triathletes. Since most were competitors of one sort or another, doesn’t that make them 1 Percenters?

Several factors made them more naturally 99 Percenters:

They were all adults. While younger swimmers have a finite horizon, thinking mostly of the next meet–almost never about swimming for life–all of our adult students were confirmed lifetime swimmers. They readily grasped that their approach to swimming would need to evolve in order to sustain them into their 70s, 80s, or longer.

Especially as triathletes came to predominate–eventually accounting for up to 70% of attendees at TI workshops–the great majority were self-coached. Thus they needed to be intrinsically motivated and empowered with the knowledge and confidence to become their own best coaches.

For our first decade, 1989-99, our focus was almost exclusively on technique. And every fundamental of our ‘fishlike’ techniques was completely counter-intuitive, requiring development of tireless and laser-sharp focus. After just a few weeks of experiencing purposeful and mindful practice, they discovered that practice had become its own reward. Their original goals remained important, but they’d come to enjoy practice so much that they’d have continued practicing, even if they’d stopped racing for some reason. The intrinsic nature of their motivation became complete.

Ironically, this transformation resulted in forming a new 1%–the tiny fraction of the 99% who fully embraced Kaizen and recognized in swimming an ideal vehicle for developing Mastery habits. We won’t quit until we’ve converted the other 99% of the 99% to Kaizen Swimmers. And a good number of the 1%–and their coaches too!

How to Join the One Percent of the 99%

Become a student of swimming, acquiring the knowledge and awareness to coach yourself effectively. Learn how your human body naturally behaves in water and the various natural forces–gravity, buoyancy, and drag–that act upon it. Understand the combination of skills–Balance, Core Stability, ‘Vessel Shaping,’ Active Streamlining, and Synchronous (all body parts working together) Propulsion–that maximize your comfort, control, enjoyment, and efficiency. Learn the principles and habits of Deliberate Practice–the approach that gives you the best chance of attaining the highest level of skill.

Be specific about the improvement you’re seeking. For each practice, choose a skill or aspect of technique that’s just outside your comfort zone, study it on video if possible, then break it into mini-skills you can do repeatedly (using rehearsals or drills–or focal points in whole stroke), revealing weaknesses and figuring out ways to strengthen them. Paying attention to what you got wrong and correcting it is the foundation of purposeful practice.

Be Kaizen. Each time you bring a skill from Conscious Incompetence to Conscious Competence–and then imprint in Unconscious Competence–find a new improvement opportunity and repeat the process. Swimming offers almost limitless opportunities to learn new skills, refine existing ones, and bring them into seamless harmony.

Our Ultra-Efficient Freestyle Self-Coaching Courses provide just the right resources to pursue the steps above. Each includes high-quality video of the skills you’re seeking to master–including the sequences of mini-skills that smooth the path to learning complex skills. And each video is accompanied by a workbook that comprehensively explains the skill, and the learning process.

Click here for more info, or to order.

The post Total Immersion: Swimming for The 99% appeared first on Total Immersion.

June 13, 2016

Should Triathletes train with Short Reps or Longer “Steady Aerobic” Swims?

I was invited to respond to a reader query in the Tri Clinic section of the UK-published magazine 220 Triathlon. It won’t be published there for another month or two, but readers of my blog get a sneak peek at my response. I’ve written at greater length and detail on this topic, but in this case the editor gave me a tight ‘budget’ of 420 words for my response.

“How often should I be doing steady aerobic swims? This seems to be a cornerstone of run/bike training, but it’s all short sets and rest breaks at my coached swim sessions. I’m confused!”

Your question provides an excellent opportunity to explain the contrast between your run/bike training and the sets you do at coached swims. [I’ll note first that I’ve swum over 40km, training mostly with pool repeats of 200 meters or less, saving longer swims for open water.]

By ‘steady aerobic swim,’ I surmise you mean a continuous swim of, say, 10, 20, or 40 minutes for a sprint, Olympic, or full/long distance event respectively. If swimming was more like cycling and running, this would make sense. But the factors determining how well you swim—and how the swim affects your ability to perform your best across three disciplines—are very different. A quick summary:

To have your best race, swim your desired pace as easily as possible—saving energy to work much harder, much longer, on the bike and run. You convert effort into speed far more efficiently on land than in the water. Thus bike and run workouts should be more aerobically demanding.

How fast you run and bike is determined 70% or more by aerobic capacity. For triathletes with no formal swim experience, efficiency—not aerobic fitness—will account for 90% of performance.

I surmise that your swim coach probably gives shorter repeats, because that’s what she’s most familiar with from experience as a competitive swimmer. It makes even more sense for triathletes because it’s the perfect way to train faster . . . easier.

E.G. let’s compare a continuous 20-minute swim with a set of 10 x 100m repeats. You would likely swim 5 to 10 percent faster with the same, or perhaps less, effort on the shorter repeats. As well, you’d almost certainly maintain a higher level of efficiency—swim that pace in fewer strokes—on the shorter repeats.

Rather than longer swims, I suggest you personalize the coach’s sets by striving to swim your current practice pace (1) more easily and efficiently; and (2) more consistently. Here are a few ideas for getting more value from a common set such as 10 (or more) x 100.

Experiment with efficiency-improving techniques like: (i) Align head and spine; Kick less; and Swim as quietly as possible.

Count strokes. Can you swim same pace in fewer strokes with those focal points?

Complete each repeat with as little variation as possible in time (and stroke count too.)

The enhanced purpose and focus of practice goals like these should become its own reward . . . but you’ll probably also find yourself swimming faster with less effort within weeks.

The post Should Triathletes train with Short Reps or Longer “Steady Aerobic” Swims? appeared first on Total Immersion.

May 20, 2016

Three ‘Secrets’ of Swimming Faster

There are two ways to try to swim faster. One is what I call the “Limbs, Lungs, and Muscles” approach. Move your limbs as fast as you can. Put more muscle into your stroke. Hope that your fitness will outlast failing muscles and that you can ‘push through pain barriers’ as coaches often say. For most this is a path to failure and frustration.

Total Immersion teaches a second way—speed as a problem-solving exercise. The fact that you’re solving the most exacting problems in swimming can also transform this into a Mastery pursuit. The TI way to swim faster is based on three well-proven principles. There not really ‘secrets.’ I only call them that because so few people take advantage of them.

1. Start with Stroke Length. The foundation for fast swimming is Stroke Length. For over 60 years, every authoritative study of factors that correlate with speed found that longer strokes matter most. This has proven true in all strokes and all ages—from 10 and under to 80 and up!

How far should you travel? For freestyle, from 55% to 65% or more of your height. We’ve converted that into Strokes Per Length (SPL), recorded on our Green Zone charts of height-indexed efficient stroke counts in any standard distance pool, available as a free download here.

When stroking at the lowest SPL for your height, your hand leaves the water–at the end of the stroke–pretty close to where it entered. In other words, most of your energy is converted into forward motion. When your stroke count is above the highest in your Green Zone, too much of your energy is moving water back.

Once you can swim your Green Zone counts with ease and consistency, strive to patiently increase the distance and/or speed at which you can maintain those counts. If you’ve been swimming at higher counts, try this simple exercise: Compare the speed of your arm moving back with the speed of your body moving forward. Slow your stroke until they match.

2. Train your Nervous–not Aerobic–System.

In 2005, just before I turned 55, I set several goals that were far more ambitious than any I’d contemplated before. I asked Jonty Skinner, Director of Performance Science for USA Swimming’s Olympic program, for training advice. Jonty said: “It’s neural conditioning, not aerobic conditioning, that wins races.”

Jonty meant that swimmers who trained to maintain a long stroke as they swam farther and faster would be much more successful those who simply focused on swimming longer or harder. Rather than train for the capacity to work harder, focus on creating and encoding the highest quality muscle memories—to make it easier to maintain longer strokes at faster rates. Not only will it require less oxygen to swim any pace, but cardiovascular conditioning still ‘happens.’ Only it’s now specific to the stroke length and rate to which your nervous system is highly adapted—rather than to non-specific hard efforts.

3. Master t he ‘Swimming Success Algorithm’

The term algorithm was coined in mathematics over 1000 years ago and has become widely familiar in the last 20 years due to its use in computer science. Its use in modern technology suggests something complicated, but it’s definition is pretty simple: An algorithm is “a process that solves a recurrent problem.”

A recurrent—indeed nearly universal—problem in swimming is how to swim the fastest of which you are physically capable. The overwhelming majority of swimmers fall far short of their true potential (I was a prime example in high school and college) because they choose ineffective means to solve the problem—stroke faster and swim harder. This is what I did in high school and college. It led to frustration and a feeling I lacked the ‘right stuff’ to swim fast, whatever that might be.

Stroking faster isn’t so much a choice as a primal instinct, which is why so many do it. Fortunately there is a solution for this problem that is so foolproof, I call it the Algorithm for Swimming Success. It comes from 40 years of data collected by USA Swimming on their very best swimmers.

Since 1976, USA-Swimming has assigned staffers to sit in the stands and record the stroke count and stroke rate of every swimmer, in every heat, of every event at Olympic Trials—the most competitive meet in the US, and sometimes the world. Every swimmer at this meet is hightly talented and supremely fit, but in each event only two competitors—of 60 to 70 entrants–will come away with the most precious prize of a slot on the Olympic Team.

USA Swimming collected this data to learn if there was some stroking or pacing pattern which maximizes a swimmer’s chances of being among the fortunate few.

After 40 years, the data shows most clearly that a rare and completely counterintuitive skill is the key to success in swimming. That skill is the ability to maintain Stroke Length while increasing Stroke Rate.

Why counterintuitive? Well what does everyone do naturally when trying to swim faster? Work harder and stroke faster—while ignoring Stroke Length! No wonder this virtually always leads to failure and frustration: They have it exactly backwards!

With this information, you can ensure that your efforts to swim faster will have a vastly greater chance of success. To do this, plan sets which:

Reveal your current ability to maintain one stroke count (say 18 SPL), while increasing Tempo.

Make a tiny increase in tempo (as little as a hundredth of a second) and count strokes. If your SPL holds, increase tempo and count strokes again.

Continue until your SPL increases.

When your SPL increases, you’ve discovered your current level of Conscious Incompetence at this combination of SPL and Tempo. Work at this level until you can easily and consistently swim this Tempo+SPL combo. Then raise tempo again until you find the tempo at which it’s a struggle to maintain your SPL.

Learn to swim with greater ease and speed in your Green Zone with our downloadable Ultra-Efficient Freestyle Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit.

Want to master the Swimming Success Algorithm? A Tempo Trainer is the essential tool.

May your laps be as happy as mine.

Terry Laughlin

The post Three ‘Secrets’ of Swimming Faster appeared first on Total Immersion.

May 13, 2016

“You can change profoundly at any age!”

Jeanne Safer and I were in the middle of a lesson in the Endless Pool at our home Swim Studio in New Paltz NY, when Jeanne suddenly stood up and blurted out: “You can change profoundly–in body and mind–at any age.”

What prompted this? Jeanne and I had spent the previous 15 minutes trying to effect a pretty significant change in her breaststroke pull. Over the past few months, Jeanne and I had been working to change the way her head returned to streamline following the breath.

I’d noticed that when her head followed her hands as they speared forward and slightly down, her stroke gained effortless power and she formed a sleek arrow-straight line that sloped slightly downward from her hips–the highest point of her body in the water–to her fingertips. At that moment, Jeanne, a 69-year old psychotherapist and author, almost exactly resembled elite athletes such as Rebecca Soni, gold medalist in the 2012 Olympics. I found it so inspiring to see that I regularly froze that moment on the underwater video so we could both admire and marvel at her form.

Jeanne and I meet once a week for an hour–an appointment we’ve kept with few exceptions for 12 years! Between lessons Jeanne works tirelessly in the Endless Pool at her weekend home, and a college pool near her NYC apartment to tweak, improve, and imprint the subtle mini-skills we worked on together.

Though she’d mastered the new head movement–and the ability to maintain it at a variety of tempos–the change in one part of her body had affected another. Her arm stroke felt a bit alien. So we’d worked for several weeks toward a more crisp instep and forward-spear, matched to the new head movement pattern.

At the beginning of today’s lesson I asked Jeanne to make the stroke more compact–seeking a feeling of natural leverage. To help her better feel what I was seeking, for several strokes I ‘caught’ her elbows with my hands, to redirect her arms forward a bit more quickly. (Anyone who coaches in an Endless Pool LOVES the ability to make those sort of instant adjustments because the swimmer stays in place in a current just inches away. We sometimes describe it as “like being a chiropractor in the water.”)

Jeanne picked up quickly on my ‘kinesthetic guidance’ and her stroke began to look quicker and crisper. On her next sequence–without any hands-on guidance–magic happened. She swam about 20 strokes, gaining confidence and awareness almost with every stroke. I was recording video the entire time.

At first I watched her directly, observing what she did above the surface. Then I turned my attention to the video monitor to observe what was happening underwater. As I did I could see dramatic transformation in the space of about eight strokes, as she increased the power, quickness, consistency, and assurance of this new movement. At one point, I involuntarily breathed out “Wow!”

Jeanne sprung to her feet excitedly as soon as she stopped swimming and said: “You can change profoundly–in body and mind–at any age.” And, in the next breath, she said: “But I’ve spent 12 years with you learning how to learn.”

What happened with Jeanne today was made even more striking by an observation I’d made less than 24 hours earlier. Last night I dropped in to watch the local Masters group work out. I swam with this group from 1993 to 2006, but not since. But next week the current coaches (college students) will leave for the summer and I will step in for them for the next several months.

I’ve known many of these swimmers for years. Last night their strokes looked exactly as they have since the first day I met them. In fact, one of them was a college teammate of my eldest daughter. He looked exactly the same last night as the first time I saw him swim 24 years ago.

When I begin coaching them next week, I will offer to help those who are interested to change their strokes for greater efficiency–and possibly to learn you can change profoundly at any age.

And when you realize your capacity to change your stroke, you may then begin to think: What else can I change?

May your laps be as happy–and evolving–as mine.

Terry Laughlin

Want to change your stroke–and yourself? Our Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit is designed to create transformation in how you swim and think.

Jeanne Safer’s latest book is The Golden Condom: And other essays on Love Lost and Found.

The post “You can change profoundly at any age!” appeared first on Total Immersion.

May 6, 2016

How to LOVE Practice–and Why That’s So Important

Three weeks ago I published a post The 4 Stages of Skill-Learning. And the Critical Kaizen Loop which proved to be one of the most popular of the year. In that post I explained the stages through which we all must progress in learning any skill, and why it’s so critical that the final two stages become an endless loop.

This post is about how to navigate those two final stages–especially as you move from simpler to more advanced skills. It’s in this process that you develop the habits of Mastery–habits you can apply to anything.

My Sensei (Master Teacher) on Mastery has been George Leonard. Leonard was a student of zen who began study of aikido at age 47, and earned the rank of Sensei. Of all who attained Sensei rank, he began study latest in life.

From this experience, he wrote Mastery, the Keys to Success and Long Term Fulfillment, which has become essential reading for any serious student of TI.

In a single sentence, Leonard’s message is: Success and satisfaction in any endeavor are byproducts of learning to love practice.

According to Leonard, that transformation occurs as a result of choosing a challenge that requires your full devotion. All TI instruction is consciously designed to provide that sort of challenge, and to increase your passion for, and enjoyment of, practice.

Four Mastery Habits

A conscious ingredient of all things TI is the goal of not only swimming better than ever, but also developing habits that have an enduring positive impact on body, mind, and spirit. Here are four essential habits, and one critical insight.

Habit One: Focus on improvement. Your core goal for every practice should be to Improve Your Swimming. For instance, learning to replace the instinctive habit of pushing water back with a conscious intention to use your hand to hold your place in the water is an important step in learning an effective Catch-and-Press (the part of the arm stroke which propels you forward. “““Can you sense yourself doing this slightly better after 10 minutes of concentrated practice? Did your ability to maintain focus also improve? Improving both is critical to success.

Habit Two: Strike a balance. Each time you practice Hold Your Place, set your ‘success bar’ slightly higher. In fact, every task you undertake should feel like a stretch—but not too much. Too easy = boredom. Too difficult = frustration. TI lessons are designed to guide you through a series of small ‘wins,’ each preparing you for the next.

Habit Three: Embrace imperfection. Most of the time, you’ll miss the mark you were aiming for. That’s good! Mistakes concentrate your attention and are essential for course correction. Continual improvement is a process of repeated mistakes and recalibrations, each bringing you slightly closer to success.

Habit Four: Love the ‘plateau. The most essential skills in swimming efficiently–Balance and Streamlining–involve large body parts and muscle groups, and require simpler coordination. So breakthroughs generally come in steady succession. As you progress to more advanced or complex skills, you encounter a steeper learning curve. At times, you may wonder if you’ve hit a plateau. You haven’t! If you embrace the first three habits, change is ongoing—but at the cellular level. That cell-level change periodically consolidates to produce an exciting forward leap. (After 50+ years of swimming, I still experience such leaps about once a year.) Between leaps, the pleasure of being totally immersed in practice becomes its own reward.

The Invaluable Insight: You never achieve Mastery! A true Master never becomes complacent, never stops pursuing improvement. Swimming, where every important skill is counter-intuitive, provides more opportunity for this than any other skill or sport. Among all athletes, and students of movement arts, swimmers have the greatest expectation of being able to realize lifetime learning and improvement. This is why TI embraces the ethos of Kaizen.

Our downloadable Ultra Efficient Freestyle Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit not only teaches the essential skills of an ultra-efficient freestyle. It also teaches the four habits of Mastery.

May your laps be as happy as mine.

Terry Laughlin

The post How to LOVE Practice–and Why That’s So Important appeared first on Total Immersion.

April 29, 2016

Video Chat with Kirsten Sass TI Coach, Multisport Athlete of the Year, Mom, Health Professional

Two months ago, at at the TI Triathlon-Swim Camp at the National Triathlon Training Center in Clermont FL, I enjoyed the privilege of coaching alongside a very strong group of TI coaches–all of whom happened to be women. Not only was I the only male in the group, I was also the only coach lacking formal triathlon credentials. Suzanne Atkinson, Celeste St. Pierre, Dinah Mistilis, and Tracey Baumann all boast some mix of certification as triathlon coaches, current direct coaching of multisport athletes (and swimmers), and/or experience participating in triathlon themselves.

Two other TI Coaches at that camp, Darbi Roberts and Kirsten Sass have the distinction of having achieved elite athlete status as triathletes. Between them, they made 2015 a banner year for TI coaches in multisport.

In November, Darbi improved her already-impressive Ironman personal record by 20 minutes to record a stunning 9:05. In our interview, Darbi shared that, though she races as a pro, she must balance her training with unusually demanding personal and professional pursuits, which include serving as a Dean at Columbia University, while concurrently pursuing a Doctorate in education at Columbia’s illustrious Teacher’s College. News Flash: Just this week, Darbi successfully defended her doctoral dissertation.

This week’s post features my chat with Kirsten Sass, who became the most decorated multisport athlete of all time. Kirsten–who is coached by Suzanne Atkinson–capped a fantastic racing year by adding the title of Overall Age Group World Champion in Olympic distance to a long list of USA national championships. And at year’s end, Triathlete Magazine honored her as both the Age Group Triathlete of the Year and Duathlete of the Year–so far as we can tell the first time one individual has ever won both honors.

Kirsten’s smile says it all: World Champion!

Like Darbi, Kirsten has balanced rarefied athletic feats with a full life. As Kirsten says, her most important role is as a mom to Sebastian and AlyssaBella, shown below, following one of Kirsten’s USA titles, with husband Jeff Sass

Kirsten’s Support Team

And Monday to Friday, Kirsten is a busy Physician Assistant at the McKenzie (TN) Family Medicine Center, founded by her dad Volker Winkler MD, a triathlete himself and a TI enthusiast for over 20 years.

Kirsten with nurses Gina Pinkston (L) and Marie Chappel (R)

As you’ll learn in the interview Kirsten has two great assets. First, an irrepressible positive attitude: After finishing last in her age group in her first triathlon, she thought, “Well, I have nowhere to go but up.” And second, TI techniques and practice principles, both of which she credits with helping her Achieve Flow as athlete, mother, and health professional.

Enjoy our chat. It includes several clips of Kirsten and I ‘synch-swimming’ in the National Triathlon Center pool.

Both Kirsten and Darbi have enjoyed such success and happiness–in and beyond their sport–in part, by swimming better through smarter choices–not greater efforts. Learn more about this in our ebook Sneaky Speed: Smarter Choices in Triathlon Swimming available as a free download in our online store.

Learn the ultra-efficient techniques that helped both Kirsten and Darbi (and thousands of others) swim faster . . . easier . . . with our downloadable Complete Self-Coaching Toolkit.

Or join us for our next Triathlon Swim Camp May 11 to 13 in Key Biscayne FL.

May your laps be as happy as mine,

Terry Laughlin

The post Video Chat with Kirsten Sass TI Coach, Multisport Athlete of the Year, Mom, Health Professional appeared first on Total Immersion.

April 21, 2016

Guest Post: A Recovery Journey of “strokes taken with awareness and care”

Robbie Stamp, the author of this guest post, originally sent this as an email, one of many messages of support, wisdom, and love I’ve received in recent months. I knew immediately it deserved to be shared as widely as I could as Robbie’s message about TI and cancer recovery is not meant for me alone. Enjoy!

Dear Terry

I am privileged to be coached by Tracey Baumann. You and I met once at Tracey’s group practice in Windsor and had a chat about Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theories on Flow and how that influenced your work and that of the the Consultancy I chair.

I was so sorry to read recently about your prostate cancer and I just wanted to add a small extra tributary, to the ‘river of love’ for your meditations: An image of clear cool water running over smooth stones just a few feet below your swimming form and the dart and blue of a kingfisher, glimpsed as you take a breath

I came to TI in the summer of 2012 after a hard 2-year journey following surgery for kidney cancer. My wife knew I had been struggling and also knew that I had always loved open water swimming. Indeed one of her favourite memories of our first holiday together is me saying “I’m going for a swim” and her thinking, “fair enough” and returning to her book. She was a little surprised when I didn’t return for two hours!

So she intuitively knew that, as I was having a hard time mentally and physically and was still not really comfortable in my new body, without its left kidney, that I needed to swim. She arranged a holiday on the fabled Lycian Coast in Turkey. On the first morning I took myself down the very steep hill to the sea and swam and then I swam for hours and hours on that holiday. I began to heal.

When I got back to London I googled “open water swimming.” With the universe holding me in the palm of its hand, of all the places I could have gone, I found my way to Taplow Lake where Tracey coached. She had a special aura of warmth and friendliness. I set out for a loop of the lake. Tracey said she could see that I could swim well enough, but might enjoy a lesson or two. I thought “Why not?” I hadn’t been ‘taught’ since I was a small boy at the “Monsoon Baths.”

Being honest, I went to my first lesson with a little hubris, expecting “a nip and a tuck here and there maybe.” Instead, from my first moments in Tracey’s Endless Pool, I could feel something very special. I embarked on that journey so many had taken before me of having my technique deconstructed and reconstructed with attention, care—even love.

I swam the English Channel in a relay this summer with friends from the Tracey’s Thursday practice group. Tracey bravely accompanied us—though knowing she would be quite sea sick. Indeed she was the one who gave me a big hug, on finishing my final leg which got us to within 750 meters of the beach in France. I sat in her arms and let out a primal howl of exhaustion, relief and triumph after five years in cancer’s shadow.

I know that my story is repeated in many forms, in the face of many challenges, around a world in which TI and swimming have come to matter so much to so many.

I love the concept of Kaizen–of the happiness of being on an endless journey—in recognition that it is indeed the journey rather than the destination. The ‘steps’ on that journey are measured in the awareness and care one gives every stroke and breath–and the feeling that ‘creating beauty’ in the water is the gift of a lifetime of practice.

I also wanted to say offer some other thoughts about cancer, and I hope that you will forgive the presumption. Some poetry first

I am sure you know these lines from William Blake’s Auguries of Innocence

“Man was made for Joy & Woe

And when this we rightly know

Thro the World we safely go

Joy & Woe are woven fine

A Clothing for the soul divine

Under every grief & pine

Runs a joy with silken twine..”

You might be less familiar with these lines from Edward Thomas, the English poet who died in the last days of the First World War, who is my favourite poet. I have loved his work since I was at school and listened to his then seventy-year old daughter read some of his poems, amongst which was “Liberty” from which this final verse comes.

“And yet I am still half in love with pain,

With what is imperfect, with both tears and mirth,

With things that have an end, with life and earth,

And this moon that leaves me dark within the door.”

Expressed so beautifully in the Blake and the Thomas is compassion, compassion for when the night seems darkest and our more vulnerable selves need care and an arm round the shoulder with that hard ‘grown-up’ acknowledgement that life can be hard too.

Here is why I think that what TI coaches do, when working at their highest calling, is so profound. The feel of the water, the sense of immersion and belonging, the pleasure like a Japanese calligrapher in the beauty of a pen line, in the beauty of a stroke and a breath and a fleeting sense of grace or a longer meditation: They all have compassion flowing through them – compassion for family and friends and colleagues and strangers and for our own small selves in the still watches of the night, in our confusions and uncertainties too.

I am sharing these lines too because I think they also contain important ideas about allowing the space for uncertainty in our cancer journey. Indeed you wrote of the “roller coaster between fear and doubt and hope and cheer.”

There is no doubt that positivity makes a huge difference, indeed maybe genuinely at a cellular level, but we would not be human if we did not have those moments of fear too. Amidst the health-giving food, meditation, and movement exercise and that drive to do good work, those feelings need to be acknowledged as part of being human. I found that the friends with whom I could share that uncertain space too were very precious.

I remember someone saying to me early on, before I had my operation, “It’s all in the mind.” I thought, “No its not, it’s in my kidney!” Others would say “It’s important to be positive.” Knowing they meant only kindness, there too, I sometimes longed to say, “So if I am having a tough hour, or afternoon, or indeed week, I can’t acknowledge the fear, that I must pretend otherwise?”

People often use militant or violent language about ‘fighting’ cancer. It is refreshing not to see that in what you’ve written. (Though if someone felt that helped them, I would never wish to take it away.) The key is that it is the person who has the cancer who gets to choose their metaphors. As you write, each individual must become “the agent of their own recovery.”

Early in my journey a friend who had had a brain cancer said that they were glad that they had had the cancer. At the time I thought “Wow, not sure how that works” but I now know what they meant.

If not for cancer, I would not have come to TI, would not have met Tracey and some of the wonderful fellow swimmers at the Thursday Masters practices, would not have swum the English Channel with special friends and would not have taken control of other aspects of my life too.

So Terry for all that you have brought and are yet to bring, in the hard moments ahead as well as the moments of revelation and for all the compassion and for your gifts in the water, thank you and I wish you flow for many, many years to come.

Robbie is Chairman of Bioss, a Consultancy business that thinks a lot about what being “in flow” means for organisations and individuals. He once started a company with the late great Douglas Adams, author of the Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy, executive produced the movie for Disney, and is also Chairman of h2g2.com the web site he and others started with Douglas way back in the 1990’s.

Robbie prefers ‘skins’ (no-neo) swimming and is hoping to swim Lake Windermere in England this July with TI friends.

The post Guest Post: A Recovery Journey of “strokes taken with awareness and care” appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers