Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 15

December 9, 2016

Dreams Never Die

Two months ago, a letter arrived in the mail, It began “Dear Terry, I want to thank you for helping me to achieve one of my dreams.” and went on to tell a memorable–and cautionary–story of a decades-long pursuit of athletic dreams. I asked Thomas Lyden, who sent it, for permission to publish excerpts from it as a guest post. Here it is.

In 1980, at age 18, I watched ABC’s Wide World of Sports coverage of the Hawaii Ironman, the first time that event was on TV. I wasn’t a swimmer, cyclist, or runner, but I thought “It would be neat to do that some day.”

As a youngster, I rode all over town on a hand-me-down bicycle. In high school I thought about going out for cross country team, but never did. And I’d been a diver on the swimming team, but quit after sophomore year.

In my late 20s, in 1991, married with our first (of three) daughters, I bought my first pair of running shoes and a racing bike, and started swimming, teaching myself freestyle with the aid of library books. I entered a ‘sprint’ triathlon in Delaware, Ohio.

My age group was the last to start. It began to rain during the run and the volunteers were packing up the course as I struggled to the finish line. I thought I was the last to finish, but later learned I’d finished 15th out of 17 in my age group.

As I drove home I told myself I’d keep doing triathlons until I earned a ‘podium’ finish–1st, 2nd or 3rd in my age group.

In the late 1990’s I stopped training, while pursuing an MBA, picking it back up after my studies were complete. About this time, a co-worker gave me a copy of the book Total Immersion. This book helped me to improve my swim stroke. But I hated how long it took to get from one end of the pool to the other while doing drills. Everyone else was swimming laps while I was trying to “press my buoy.”

In the early 2000s, I entered the Columbus [Ohio] Marathon. Six weeks from race day, I’d already had enough. With all the mileage I was doing, running just wasn’t fun anymore.

On my final long run, a 20-miler, I returned home literally hurting from head to toe. I had a headache, my neck was chafed, my hips and knees hurt, and my toenails had turned black and blue. I was done. If I couldn’t run a marathon—without swimming and biking—doing an Ironman seemed far out of reach.

I decided to lower my sights to completing a half-Ironman. In the summer of 2004, without a training plan, just my own idea of combining swimming, biking and running, I trained for a half Ironman.

I took a few swim lessons at the YMCA, biked hard, and assumed the run would take care of itself. In retrospect, my 6:10 finish wasn’t bad. A half Ironman is a worthy accomplishment. It wasn’t, however, an Ironman.

One day in 2005 I bumped into a former neighbor at the YMCA. He commented he’d just finished a marathon. I thought, to myself “How could this guy ever finish a marathon?” He was built like a fire plug, short, stocky, and when I saw him running through the neighborhood, he just plodded along. I said to myself, then and there, “I’m going to run a marathon.”

In 2006 I finished the Cincinnati Flying Pig marathon in 3 hours, 28 minutes and 56 seconds. Had I been six months older–in the 45-49 age bracket–my time would have qualified me for the Boston Marathon. The dream of completing an Ironman was now within reach.

þ Run a marathon

A few months later, I got a new boss at work. His demands made my life miserable and left no time for physical activity, which I’d always loved to the point of obsession. Eighteen months later I left that position and resumed training, with a goal of completing a half Ironman in 2009. If I did well, I’d consider a full Ironman in 2010.

While training for the half Ironman , I attended a Student Leadership Conference in Orlando. At the conference, Dr. Jay Strack talked about the Mediocre Inn in the French Alps. Many climbers set out for the peak but when they reach the half-way point they stop and go into the inn (mediocre means “halfway” in French). While inside, they get warm and comfortable while resting. As a result, they turn around and descend back down the slope, never to reach the peak.

After listening to Dr. Strack, I decided I wasn’t going to get comfortable and satisfied with another half Ironman. Upon returning from Florida, I registered for a full Ironman in 2010.

It was time to get serious about swimming. I took some lessons at the YMCA but it wasn’t until I really started to study Total Immersion DVD’s, that my stroke started to become more efficient, and effortless.

Training for an Ironman is hard. Early in the season, I was out biking when there was still snow on the ground. Cold, dark, and rainy mornings give way to hot, long, and dry afternoons. By August, I started to have doubts about my ability to finish. Then I thought back to a family vacation we took when I was 12.

Throughout my childhood, I heard about the Empire State Building and how for years it was the world’s tallest building. A few years before our vacation, the World Trade Center was built and replaced it as tallest building. On our trip to New York City, our parents gave us the choice of going to either the top of the Empire State Building or the World Trade Center.

We picked the Empire State Building. I distinctly remember thinking “I can always come back and go to the top of the World Trade Center.” But I didn’t return to NY until 2005. I again went to the top of the Empire State Building, but there was no longer a World Trade Center. I never had the chance to go back nor to the top. I remembered that “never had the chance” as I pushed towards the end of my training.

On September 12, 2010 I fulfilled a 30-year dream of completing an Ironman Triathlon, finishing in 12 hours and 59 minutes.

þ Complete an Ironman Triathlon

At this point, I decided all future athletic endeavors would be “just for fun.” But for a Type A obsessive “just for fun” is hard. I still had the dream of standing on a podium.

By the summer of 2011 I was in the best shape of my life. I was lifting weights, swimming, biking, and running. On July 2nd I biked 50+ miles. On July 3rd I ran 8 miles in one of my fastest times ever. On July 4 I planned to go for a 60-70 mile bike ride.

Instead, I woke up in the back of an ambulance with a paramedic sticking a needle in my arm. “Mr. Lyden, hold still, I need to start an IV. You’ve had a seizure and we need to take you to the hospital.” I’d had a grand mal seizure and was diagnosed with epilepsy.

Four weeks later, it was all I could do to jog easily for two miles . Yet, I was undeterred. I continued to train. In my next marathon, I wanted to qualify for Boston.

On May 6, 2012 I finished the Cincinnati Flying Pig Marathon in 3 hours, 25 minutes and 6 seconds. I finished 11th of 238 in my age group and qualified for Boston.

þ Qualify for the Boston Marathon

I’d still not finished a triathlon “on the podium.” If I competed in a lot of races I might have accomplished this by now. I still had a life to live and when I train for a race, I want the race to be memorable.

Through all this training I swam only freestyle. I thought it was time to learn other strokes. I ordered TI videos for Backstroke, Breaststroke, and BetterFly. I started with Backstroke and set my sights on another half Ironman in 2013.

The podium finish was not to be. I finished 6th of 11 in my age group. Although my finishing time was the fastest of my three half Ironman races, the 2nd fastest run time in my age group could not overcome a slow bike split.

I’m not one to let a dream die easily. In 2016 I’d move into the 55-59 age bracket. How many competitors could there be? I could say I kept at it while others gave up competing. Wouldn’t that be something? Fifty-five years old, completing an Ironman, and “Standing on the Podium.”

I committed more fully to improving my swimming, for the first time hiring a TI Coach, Leah Nyikes, to film and analyze my stroke and work with me on weak points. I bought a new racing bike and worked with Ohio State Sports Medicine and Rehab to analyze my running stride and develop core exercises to improve it.

I trained. I had doubts. I trained. More doubts. My swim times were slower than in 2010, but my biking speed increased and my run times were far faster than 2010. I pushed and pushed and pushed.

Within seconds of crossing the finish line, my daughter called out, “Dad, you’re 2nd out of 9.” Eleven hours and 54 minutes earlier in the day I had set out for the podium. I made it.

þ Finish a triathlon “On the Podium”

I was elated. I’d achieved every dream. I would now “Stand on the Podium” in an Ironman.

After the race, I wasn’t feeling well. I went to the medical tent. I was dehydrated. They put two liters of fluids in me. The doctor ran an EKG. The results appeared abnormal. He suggested I go to the emergency room.

With lights and sirens I was transported to the local hospital. I spent the night in the ER. My family “stood on the podium” the next day at the awards ceremony while I lay in the hospital.

The test results indicated I’d damaged my heart. The cardiologists said “let this be a warning.” I’m done. I’ve run a marathon, qualified for Boston, completed an Ironman, and finished a triathlon standing on the podium. Dreams Never Die. Thanks to your help, I’ve achieved mine.

Thomas Lyden lives in Hilliard OH.

Postscript: After reading Tom’s letter I suggested to him that he could still pursue meaningful goals in a healthy manner: Return to the Different Strokes and achieve mastery . . . and ease.

The post Dreams Never Die appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 7, 2016

Improve Your Weekly Practice Plan

Rather than trying to train the skill in a variety of ways in a single practice, each practice focuses on one dimension of control and works it thoroughly…allows the skill to be developed under more precise constraints, isolating the weakest link in the performance systems.

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Improve Your Weekly Practice Plan.

The post Improve Your Weekly Practice Plan appeared first on Total Immersion.

December 2, 2016

Want to Swim Faster? Don’t Close Your Fingers

Should you keep your fingers closed or relax your hand while swimming to allow them to separate a bit? Many non-TI instructors and coaches say—and most swimmers seem to believe—that you achieve the best grip with fingers closed because that makes the hand more paddle-like.

In contrast, TI has long taught swimmers to avoid swimming with a stiffened hand and TI coaches watch carefully for closed fingers, even on recovery, as I demonstrate here.

A relaxed hand about to enter the Mail Slot

So who is right, TI or the traditionalists?

According to this article in the journal Science, a study presented last month at the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Fluid Dynamics suggested that freestyle swimmers are most efficient when they swim with fingers slightly apart, as this swimmer shows. (She also forms a beautiful line from right hand to right toes.)

This is how a 10-degree separation looks.

Physicists using 3D-printed plastic hand and arm models in a wind tunnel found that the model with its fingers spread 10° created the most drag because the slight opening between the fingers still obstructed air flow.

Though the subject under study was swimming, they performed this experiment in a wind tunnel rather than a pool to avoid the influence of surface waves. Because fluid dynamics follows the same principles as aero dynamics, they’d have reached the same conclusion in water.

The researchers calculated that a 10-degree finger spread could boost a swimmer’s speed by 2.5% compared with swimming with fingers pressed together. That translates into several tenths of a second over a 50-meter freestyle race, an enormous margin considering that the 2016 Summer Olympics 50-meter women’s freestyle race was won by 0.02.

A triathlete who completes 1500 meters in open water in 40 minutes could swim a minute faster, simply by relaxing the hand.

But the benefits of a relaxed hand can be even greater. Our primary reason for teaching a relaxed hand is that a common hydrodynamic effect of stiffening the hand and closing the fingers is that it leads to scooping the hand upward as you extend forward. This drops the legs, significantly increasing drag.

Enter at this angle to lift the legs, and reduce drag.

In contrast, when you relax your hand, it can cause the hand to naturally arc downward, lifting the legs and reducing drag, leading to far greater increases in speed.

Arc your hand and arm downward, like this, to lift the legs toward the surface.

I’ve been convinced for a long time that a relaxed hand can make you a significantly faster swimmer by improving balance and reducing drag. At the same time I was also fairly certain that it also makes the stroke more propulsive.

I arrived at this conclusion by performing a simple experiment: Just put the hand in water (at the pool or in a deep sink) and move it back and forth. First with fingers together, then allowing them to separate naturally (i.e. don’t splay them; just don’t squeeze together). Compare the resistance you feel with closed and separated fingers.

But it’s nice to have our ideas bolstered by physicists.

Learn the full range of energy-saving, speed-enhancing skills with our downloadable 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course.

The post Want to Swim Faster? Don’t Close Your Fingers appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 30, 2016

Comfort Needs Discomfort

Change – even if it is good change – is stressful for the body so the athlete encounters physical and mental resistance when trying to make changes to the system…Here is very sober physiological truth to let sink into your mind: your brain and body are never in a fixed-state of health and performance – there is no coasting along on good health…

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Comfort Needs Discomfort.

The post Comfort Needs Discomfort appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 28, 2016

Swim for Health and Vitality: Cancer as Opportunity?

Amby Burfoot won the Boston Marathon in 1968 as a Wesleyan undergrad, where Bill Rogers was his roommate and teammate. Amby’s best marathon time of 2:14:28.8 at Fukuoka later that year was just 1 second off the American record.

Amby became a leading chronicler of the running boom as editor-in-chief of Runner’s World for many years, where he continues to serve as editor-at-large. Amby and I developed a close friendship after he came to me for TI instruction in 2006 to help extend his enjoyment of the running life.

A measure of just how much Amby loves running is that he recently ran his 54th consecutive Manchester CT Road Race, a record-breaking streak dating from age 17 to 70! Running Manchester annually has given Amby a rare record of the effects of aging on his performance, which he described with humor and unflinching honesty in an email:

“The Manchester course has not changed over my 54 years, so I have an accurately depressing data set of performances. My best was about 22:22. Today I ran a not-proud-but-what-can-I-say 37:12–roughly 67% slower than my best, or 1.24% slower per year.

This hasn’t been a straight line. For over 4 decades, my decline rate was .9% per year, but the last 7 years have been more like 3% per year.

I’d say my training has been a constant for the last 40 years. Roughly 25-30 miles a week, including intervals, occasional 5K race efforts, and a couple hours of gym time.”

Amby’s message made me curious about my comparative decline in performance. I chose the 1650y (equivalent to 1500m) freestyle as my performance benchmark, both because it’s the longest swimming event for which a rigorous measurement is available, and because it’s closest in duration to the Manchester Road Race of all standard swim race distances.

I swam my fastest 1650 of 18:02 at age 20. I’ll swim my next 1650 on Dec. 11 and have no doubt, it will be a ‘lifetime slowest.’ Based on my current training, I estimate I might swim it in about 26 minutes. This would be 45% slower than my fastest, for an average decline of exactly 1% per year.

Like Amby my decline has been quite uneven, but there are few other similarities between our experiences.

Between age 20 and 55 I slowed by only 10%, or an average decline of only .28% per year.

Between 55 and 64 (last March), I lost a further 21%, an average performance decline of 2.3% per year.

Over the past 8 months—if my projection is correct—I’ll have lost an additional 14%, a function of the effects of cancer treatment.

I’ve slowed a lot less since age 20 than Amby has, but have declined far more precipitously of late. And while he’s run Manchester for 54 consecutive years—and never took a hiatus from regular run training—I ‘retired’ from swimming at age 20, returning to the pool at age 37. I didn’t race a 1650 for 21 years from age 20 to age 41. Yet—despite my lengthy hiatus–I slowed only 50 seconds, or just 4%, from my best during that period.

One reason is that Amby was an elite marathoner in college, nearly breaking the American record. I was a clueless, erratic, and underperforming athlete until my ‘retirement’ at age 20. But I spent my 17-year hiatus coaching others, gaining priceless insights into the value of technique, one of the things about which I’d been clueless as an athlete.

I founded TI near the end of that hiatus. I’d begun to prioritize a, ‘vessel-shaping’ approach to technique and had begun transforming my own stroke, while acting as ‘guinea fish’ for what we taught to TI students.

Illness as Opportunity

My most valuable insights however have come in the past decade, a period when I’ve experienced significant health challenges. I’d been fortunate to enjoy great health through my mid-50s. Shortly after breaking national records at age 55 and 56, I was hit by polymyalgia rheumatica, an autoimmune syndrome characterized by fatigue and inflammation. That greatly accelerated my loss of speed.

I swam few pool races during those years, but never stopped training. While I couldn’t train as long or effortfully as I had a few years earlier, I never became complacent. Though my repeat times were much slower, I developed an unprecedented keenness of focus, trying to eke out every last bit of speed and endurance from my limited capacity.

I swam my first 1650 in nine years last March. My time of 23:10 was my slowest ever (and 3 minutes, 40 seconds slower than I’d swum at age 55). Yet in the blog 1390 Seconds of Unwavering Focus I described it as one of the best races of my life, with respect to focus and execution of a race plan. I’m hopeful of doing similarly next month.

In my teens I worked as hard as humanly possible, yet often had race results that were most disappointing in comparison to how I swam in training. In my 60s, I’ve exerted myself quite judiciously yet have consistently raced intelligently and effectively. That intrinsic quality–and the quality of the experience–not the objectively measurable, but extrinsic, quality of time, has become my primary measure, and is consistent with what I teach.

I took a break from writing this blog to visit the pool at midday. While swimming I reflected on the almost limitless opportunities that exist in swimming to improve a performance, completely apart from one’s metabolic capacity at the moment.

There are countless mini-skills that can improve or degrade one’s performance on a single 100-yard repeat. A 1650-yard performance is the product of countless reps on which you can solve small problems and imprint the solution–at least if you train in the neurally-oriented manner TI advocates.

Two examples: Breathing is a given in running and cycling. You barely have to think about it. In swimming, it’s probably the most challenging skill. It’s possible to make a huge improvement in one’s stroke efficiency by learning better breathing skill.

Turns are another example. One must reverse direction every 25y/m or every 15 to 18 strokes. The difference in efficacy of a turn well executed vs poorly executed is massive. There’s also a breathing or breath control component to every turn, as it involves an interruption of 4 to 5 seconds from one’s normal breathing pattern. Imagine if a runner or cyclist were required to hold one’s breath for a similar period every 20 seconds or so.

If you take aging, or some period of reduced ability as a prod to minimize the effect on performance by improving one’s skill set, you can significantly minimize the decline.

One is slowly robbed of metabolic capacity by the aging process. I have twice had the experience of losing metabolic capacity rapidly and dramatically. In my late 50s through an autoimmune disorder, and more recently by cancer and its treatment.

Both times I viewed the experience as an opportunity to raise my game on the problem-solving aspects of training. And though every race I swim will probably be my slowest ever by quite a bit, I’ll continue swimming in Masters meets as long as I can, because filling out a race registration form gives my training even more purpose.

Watch this space for further updates on my training and racing.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: Cancer as Opportunity? appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 17, 2016

TI Stroke Drill Primer: Single ARM or Single SIDE?

This week, while updating my personal practice log on the Favorite Practices and Sets conference of the TI Discussion Forum, a short thread titled Surprising Discovery caught my eye. The poster had written “I recently noticed how fast I am with one-arm crawl, in which one arm is constantly in front, the other crawling. I timed myself and found this: 50m normal crawl, all out: 40s; 50m one-arm crawl: 50s (changing sides every 8th pull)”

I saw in this an opportunity for a followup to my recent post A TI Primer: The Why and How of Drills to illuminate the process we follow when dropping certain drills and choosing/designing others. Our process for doing is characterized by an unusual degree of rigor.

Traditional Single-Arm

The ‘one-arm crawl’ he describes should be quite familiar to anyone who has swum a workout directed by a non-TI coach. Single-arm, with the opposite arm forward, is among the most commonly-used of freestyle drills. We used this drill in our first swim camps, in 1989 and 1990. I was intimately familiar with it from my days as a coach of competitive swimmers 1972-88.

At those early camps—as I always had–I taught single-arm with close attention to form and feeling. Like current TI drills, I instructed swimmers to cycle through a series of focal points while practicing it. I also had them compare their right- and left-arm strokes by calculating 25y/m Swim Golf scores (strokes + seconds) for each.

We stopped using single-arm crawl in the early 90s because it no longer matched our evolving technique priorities. In fact, it directly violated them.

We’ve long been guided by the dictum that “The shape of the vessel matters more than the size of the engine.” In other words, reducing drag matters more than increasing propulsive power.

The one-arm crawl, in which you leave the non-stroking arm forward, violates that principle in three ways:

The swimmer focuses on pushing water back with the arm.

By starting the push-back in a flat-on-the breast position, there is no opportunity to use weight shift as the source of power. Instead you rely wholly on fatigue-prone arm and shoulder muscles.

It emphasizes steady flutter kicking–and can easily become a kicking exercise.

In TI, we believe that all stroke drills should imprint the same skills and habits as prevail in the whole-stroke you are seeking to develop.

These include:

Use available forces (gravity, buoyancy and body mass) to generate power before using muscular forces. In freestyle and backstroke, this occurs through weight shift. There is no weight shift in the drill you’re doing.

Use powerful and fatigue-resistant larger muscle groups–particularly the core–before smaller and fatigue-prone muscles, like the arm and shoulder.

In the case of the Catch-and-Press (which single-arm purports to develop), focus on Holding Your Place rather than on Pushing Water Back. Single-arm does the opposite.

Single-SIDE vs. Single-ARM

Our 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self Coaching Course teaches a Single-Side drill–as opposed to Single-Arm. In TI Freestyle, we strive to swim with the WHOLE BODY, not the arms and legs. This means we teach a core-driven stroke, which observes and promotes the three technique principles I list above.

You do Single-Side Freestyle with the non-stroking arm at your side (hand in ‘Cargo Pocket’ as in our Torpedo drill). When the other arm is forward, it impedes rotation, forcing you to use arm/shoulder muscles to create propulsion. The series of pix illustrate Right-Side Freestyle.

Begin in your best Skate position. In this position, the hand and arm are angled down, facing back, in the ideal position to trap water. In Single Arm- both arms are at the surface, facing down, at the start of the drill, and the swimmer is flat on the breast, rather than slightly rotated as I am here.

Strive to Hold Your Place with the right arm, as the left hip—aided by gravity begins to drive down—and the right foot is poised to drive down, lifting right hip toward the surface. In single-arm the left arm, being forward, impedes the ability of the left hip to drive down. And the feet flutter non-stop.

The weight shift and stroke are complete. The body has moved past the place where the hand was at the start. The left hip and right foot are down—as they would be in the whole-stroke version of a TI freestyle with a 2-Beat Kick.

After right-hand recovery I’m still balanced and aligned on my left side as my right hand comes through the Mail Slot. My right hip and left foot will drive together to return me to my starting position as in the first photo.

Our Single-Side drill–Lesson 1, Drill 2–in our Freestyle Mastery series, imprints a balanced and sleekly-shaped vessel (Pic 1), an effective catch, that moves you forward instead of moving the water around (Pic 2); propulsion that’s driven by the whole body (Pic 3), and great body control (Pic 4). Everything you could ask of a stroke drill.

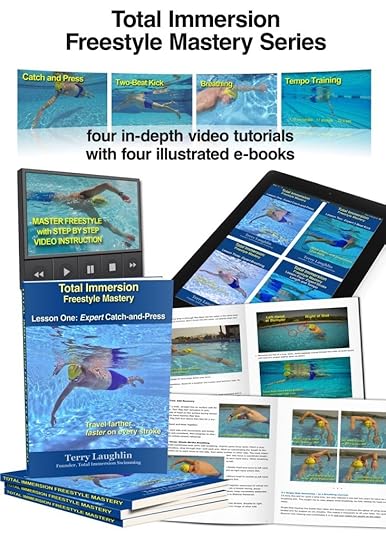

Learn this and more principles-based skin-building drills in our 1.0 and 2.0 Freestyle Self-Coaching Courses.

The post TI Stroke Drill Primer: Single ARM or Single SIDE? appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 16, 2016

Self-Limiting Practice Sets

Self-limiting exercises in swimming deal with the holistic view of training. They acknowledge the whole performance system, and expose weaknesses hidden behind alleged strengths and then work on those weaknesses until they no longer hinder the whole system…

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Self-Limiting Practice Sets

The post Self-Limiting Practice Sets appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 15, 2016

Swim for Health and Vitality: A ‘Miraculous’ Swim

A reader suggested I consider renaming my Zero Cancer blogs with a heading that’s an affirmation. I liked his suggestion, so henceforth I will publish occasional posts under the Health and Vitality heading. These will report on empowering swim experiences that also strengthen my immune system and sustain an indomitable spirit. This post reports on my evolving prognosis and several exciting and enjoyable open water swims over the past two months.

I had a PET scan Sept 12. It showed no tumor activity in organs, but revealed continued spread of cancer in my bones, with extensive scarring in my pelvis plus spots on three vertebrae and two ribs. Also, blood tests since then showed my PSA and two enzymes which reflect cancer activity rising aggressively.

My cancer had become resistant to chemotherapy during my last two treatment cycles. Even before the tests, I could sense this was happening–more days of feeling poorly and an increase in pelvic pain–however not to the point of needing pain relief.

Yet, while chemo was no longer effective in treatment, it continued to sap my stamina. During pool practices, I felt a burning sensation in arm muscles and across my chest. I could control this by swimming very easily, but with impeccable form. I seldom swam farther than a mile.

Despite all this, I enjoyed striking high points in open water. On Sept 17, I swam a 5K race at Coney Island. I experienced no burning sensation and relatively little fatigue. However I did feel quite drained the rest of the day. On Sept 24, I returned to Coney for a 2-mile race and felt even better. The following week, on Oct 1, I swam 1.5 miles in San Francisco Bay to raise funds for cancer research, which I described in this post. Despite feeling limited in the pool, I seemed to have ample stamina to cover long distances in open water.

I also enjoyed several informal swims with friends on Long Island, in the ocean at Rockaway Beach and in L.I. Sound. I was exhilarated to feel comfortable in water temperatures in the high 50s (14-15C), a tolerance I’d lost last spring.

My eighth and final chemo treatment was Oct 10. On Nov 15 (today) I begin a new treatment regime, receiving monthly injections of Radium 223 (commercial name Xofigo) and an anti-androgen called Xtandi in capsule form. Both treatments have a good record with men whose prostate cancer has behaved like mine. So I’m hopeful of feeling–and swimming–better. I was even confident enough to enter a 1650-yd freestyle race in a Masters meet on Dec 11 and to look hopefully at the possibility of breaking the Adirondack Masters 65-69 record.

Two Marathons in Two Days!

Oct 31 through Nov 8, I was in Israel to celebrate–and gain insights on–the fast growth achieved by TI-ISR head coach Gadi Katz and his team of 40 coaches and administrative support group. I scheduled my visit to coincide with their annual open water extravaganza, 3Days3Seas, which features 10K group swims on three consecutive days.

For two months prior to my trip to Israel, I’d swum only 3000 to 5000 yards per week so I doubted my readiness to complete even one 10K (an official swim marathon). But I’d swum in this event five years ago. It had been a lifetime highlight, an experience I wanted to repeat.

So I planned to swim within my capacity, continuing until I began to tire the first day, probably rest on the second day, then swim again the third day. I’d be pleased if I could swim as much as 6000 meters (a bit less than 4 miles) on the first and third days.

The first swim, Nov 3 in the Mediterranean at Tel Aviv, was cancelled because of high winds and rough seas. So if I was going to swim twice I’d do it on consecutive days, without a rest break between. On Nov 4 and 5, we’d be swimming in the Red Sea, starting in Eilat, an Israeli resort town, and proceeding south to within 300 meters of the Egyptian border.

Leaving Eilat at 5:40 am before sunrise

On Friday, I started with the slowest of four groups–one projecting a pace of 24-25 min/km then joined the 3rd group (22-23 min/km) after they overtook us at around 6K. I still felt fresh so I saw no reason not to carry on. With the aid of a moderate tailwind I completed the swim in 3:38. I did feel somewhat weary the last 2K, but finished without difficulty and felt no residual fatigue the rest of the day.

Creating a ‘Live’ TI Logo

On Saturday, I anticipated that fatigue might overtake me earlier, but I seem to have gotten a second wind–plus our tailwind was stronger. We had two planned feed stops at 5K and 8K. At 5K, I ate 2 medjool dates and drank about 8 oz of a diluted isotonic drink. I felt so strong when we reached the next planned stop at 8K that I passed on taking more calories and indeed felt fresh enough to quicken my pace over the last 2K. My time was 3:03.

Following the swim I marveled at what I’d just done. It seemed almost miraculous. But my ‘tireless’ swimming had nothing to do with miracles. Rather there were four concrete reasons for my being able to complete two marathons on consecutive days, and still feel fresh afterward–something utterly beyond the realm of the possible on land.

Being weightless. In the water, we experience only one-tenth the gravity we do on land. And when you balance and streamline well–as in TI technique– swimming requires remarkably little energy.

Put on a ‘stroke clinic.’ While TI technique gives you the potential to swim with unmatched economy, I went even farther, striving to put on a stroke clinic. I swam most of the way with partners, sometimes one on either side. I stayed with each partner or set of partners for between five and 20+ minutes, before finding new partners. I consciously tried to demonstrate my very best technique, hoping that my partners would try to imitate something they observed in my stroke. I heard many times how helpful this was.

Start slowly. The group with whom I started on Friday turned out to be a bit too slow. It found it a challenge to swim slowly enough to stay with them. But I’m convinced that swimming the first 5K (of my total 20K) super-slowly made all the difference. Studies have shown that marathon runners whose first 10K (of 42K) is their slowest have the best performances.

Draw energy from the group. On Friday I swam with a group of 40; on Saturday with about 25. In both cases, we were committed to staying together for at least 8K. I’ve swum many 10K races, and have generally endured, more than enjoyed, them. Swimming together feels entirely different. It’s a collaboration, not a competition. This aspect makes every stroke a pleasure, and everyone draws energy from the group.

Keeping the group together

On Friday, I’d swum near the front of the pack. On Saturday, I swam mostly in the middle for the first 8K, often in quarters as tight as a peloton in a cycling race. That meant I was drafting most of the time, using almost no energy while maintaining a steady 20 minutes/kilometer pace. When I went to the front of the pack during the final 2K, I felt as if I had boundless energy.

Guided by our Paddler

The finish came far more quickly and easily than I’d dreamed might be possible. Afterward I told many of my fellow swimmers that Saturday was my best day in the year since my diagnosis. Health and Vitality Swimming indeed.

I plan to return to Israel this time next year for a ‘Swim-Together-Marathon.’ I hope some of you will consider joining me.

The post Swim for Health and Vitality: A ‘Miraculous’ Swim appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 4, 2016

A Total Immersion Primer: The Why and How of Stroke Drills

Stroke drills have been an important part of TI methodology since our first adult swim camp in June 1989. The drills we teach have undergone continuous evolution since then, as have the ways we practice drills. Thus, it will probably surprise you to learn that I rarely do drills myself. Other than demonstrating them when I teach, I’d estimate that drills currently make up no more than 1% of my overall practice volume.

If they are so central to TI methodology, why are they such a small part of my own practice? It comes down to understanding the purpose of drills, when it’s right to do them, and when whole stroke is more valuable.

Why do Drills

Stroke drills are ideal when your priorities or opportunities include any of the following:

To Break Habits When Bill Boomer taught me my first balance drill, I’d been swimming unbalanced for nearly 25 years. Since I’d never experienced balance, heavy legs felt ‘normal’ and I’d developed several habits to compensate for that. It would have been difficult to tweak my deeply ingrained stroke to make a difference. But in about 10 seconds performing a balance drill, my legs felt so thrillingly different, that I could soon maintain that in whole stroke for a short distance. Not perfectly or permanently, but the new sensation was so welcome I knew I wanted to make it permanent. That small taste was all it took to commit me to intensive drill practice for the next 10 years.

To Deconstruct and Pinpoint An efficient stroke—especially freestyle—is one of the most complex movements in sport, compounded by the difficulty of executing a high level skill in water. TI makes learning easier by deconstructing the whole stroke into critical mini-skills. Drills pinpoint those deconstructed mini-skills in the way Torpedo highlights head position, allowing you to detect and correct errors far more quickly.

To Heighten Perception In the example above, Torpedo drill dramatically enhances your perception of head position. Is it slightly elevated, slightly depressed, or neutral and weightless? You quickly become aware of the difference in Torpedo—and should just as quickly take that heightened perception into whole stroke.

How to Maximize

Want to get more out of your drill practice? To use the right drill in the most effective way for precisely the skill that needs improving? Want to avoid wasted time and effort? Do the following:

Start with the End in Mind Before deciding to practice a drill, consider the kind of stroke you wish to end up with. Any drill you choose should imprint an aspect or quality you hope to see in the whole stroke. If it imprints any position, movement, or quality you don’t wish to see in whole stroke, you’re better off not doing it. For instance, you should neither practice flutter kicking flat on the breast, flat on the back, nor on your side (with shoulders and hips stacked) unless you intend to swim in those inefficient positions.

Clear Purpose Similar to the above, be crystal clear on the purpose of any drill you practice—because the main point of the drill is to imprint an efficient quality, position, or movement in the whole stroke. I often observe competitive swimmers (including Masters) and triathletes going through the motions in drill practice, seemingly more concerned with getting it done, than getting it right. Any time spent practicing a drill that fails to imprint a high quality, high efficiency movement is wasted time.

Find Right Sequence When you plan to combine several drills, practicing them in the right sequence makes all the difference. If working on propulsion, using a drill designed to improve the Catch-and-Press, or 2-Beat Kick, the propulsion-oriented drill will work better if you precede it with drills to balance the body and stabilize the core—so arms or legs are not occupied with correcting body position errors. This principle and application is covered in detail in the 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course.

What to Avoid

Unfocused Practice Swim teams often fit in drills as a part of sets like this (often given as part of warmup): 200 Swim 200 Pull 200 Kick 200 Drill. Apart from the fact that I don’t favor sets that isolate the kick or pull, there’s this: How much clear-eyed focus do you suppose the swimmers will bring to the 200s of kick or pull? Not much. They’ll be more focused on getting them done, not getting them right. And when it comes to the 200 Drill, is it likely they’ll suddenly find focus. Not very. If you do even a single length of a drill without complete clarity on what it’s designed to improve, and what sensations will affirm that it’s accomplishing its purpose, you’re wasting your time.

Too Much/Too Long Never do a drill by rote. Never do it simply out of habit, or as part of an ‘autopilot’ routine. (See above.) And don’t continue doing a drill which targets a skill you already perform at a high level in whole stroke. You’ll be wasting time if you do. Also never continue a drill to the point where (a) it’s become more of a kicking exercise, or (b) you’re more focused on getting to the other end of the pool than on super-high quality movement. You’ll be imprinting the wrong thing if you do. This is why most TI drills are now designed to be done in repeats of 10 yards or less. Including all those in our Self Coaching Courses.

No Closure Never follow a drill with something unrelated. Always follow a drill with some short repeats of whole-stroke–and same focal point–to immediately bring the new position/movement/sensation into the stroke. This ensures closure of the stroke-improvement loop.

How TI Drills Have Evolved

Drills we’ve dropped and why

These three drills were formerly an essential part of the TI freestyle sequence (with the approx. date they were replaced in parentheses).

Press the Buoy (1994) I learned this drill from Bill Boomer. In fact, it was the one that rocked my world by showing me I could have light legs. Unfortunately, its leg-lifting effect only worked flat on the breast, and became quite elusive when you rotated—as in whole stroke. Through experimentation we learned that a weightless head (1995) and slicing the hand below the bodyline after entry (1999) were even more successful at lifting the legs, and maintained that effect as you rotated.

Balance on Back (1998) This drill was very good at helping a student experience the support of the water, without interrupting that balance to take a breath. But it taught a body and breathing position that had no application to freestyle. We replaced it first with Sweet Spot, then by separating breathing exercises from those for body position (2008).

‘Zipper’ Drills (2008) These drills were part of the recovery sequence. We instructed students to draw the thumb up the side, as if pulling up a zipper. They produced a compact, even elegant recovery. But they also tended to cause over-rotation and instability in the core. Consequently, we replaced them with Rag Doll and Paint a Line drills which teach a more relaxed recovery, while preserving a stable core and promoting healthy shoulders.

Fewer Drills, More Rehearsals

In every stroke, we strive to teach the foundational skills (Balance, Stability, Streamlining, Integrated Propulsive Movements) in just three to four steps. For two reasons: (1) Fewer drills allow for more clarity on their purpose and essentials, and more quality and consistency in execution. (2) We want to prepare the student to swim a smoothly integrated, comfortable whole stroke—one well suited to further refinement–as quickly as possible. Our 1.0 Effortless Endurance Self-Coaching Course applies this principle as will our soon-to-be released Self Coaching Courses for Butterfly, Backstroke, and Breaststroke.

More Whole Stroke

In the 1990s, it was typical at a TI workshop to do some 6 hours of stroke drills before putting it all together in whole stroke for perhaps 10 minutes. Now we do several short reps of whole stroke within 10 to 15 minutes of the start of a workshop or lesson. Why? To immediately apply a new mini-skill (in this case a weightless head) as soon as possible after heightening awareness of that skill (in Torpedo.) And we continue with that approach throughout the workshop. Five to 10 minutes of a drill to heighten a sensation, followed by a similar amount of time testing that sensation in whole stroke. The proportion of drill to whole stroke is pretty close to 50:50.

This brings me to why I barely ever do stroke drills any more. I did intensive drill practice (and sometimes a full hour or more of nothing but drills) for most of the 1990s. During that time, I completely remade my stroke, dramatically increasing my efficiency. This followed a 25-year period in which there was virtually no change in my swimming.

However several things changed in the early 2000’s that led me to gradually reduce the stroke drill portion of my practice:

My improvement opportunities changed. Following 10 years focus on the vessel-shaping aspects of technique, there remained relatively little upside. I consequently shifted my focus to skills I’d relatively neglected during the 90s–Catch-and-Press and 2-Beat Kick. While there are several drills with value in learning them, most of the refinement potential comes from whole stroke practice with focal points.

I adopted new training aids. During this period I was introduced to Fistgloves and the Tempo Trainer. While the Fistgloves can be useful in some drill practice, both tools yield their greatest value in whole stroke practice. I discovered many new stroke refinement, and awareness-heightening, opportunities in whole stroke practice with one or the other.

I began racing more. Training for a certain level of speed can only be done with whole stroke. You acquire a high efficiency stroke at lower speeds, and with a mix of drill and whole stroke. You must then learn to maintain it while swimming at higher tempos, muscle loads, and heart rates. That’s whole stroke.

If you’ve been doing the same stroke drills for more than three years, it may be time to evaluate whether they are still creating improvement or simply ingraining a kind of status quo in your stroke. Is it time to change to drills for more advanced skills? Perhaps you’re ready for Mastery Skills. A visit to a TI Coach, or a video analysis by an expert TI coach can help determine.

Where I Am This Week and Next

I’m visiting Israel and our fantastic TI organization, led by Gadi Katz, from Oct 31 to Nov 7. Today I swam a 10K in the Red Sea, as part of the ‘social marathon’ event 3Days3Seas. Though my stamina has been significantly reduced by my treatment, to the point where I seldom swim more than 1600 meters in practice, I easily completed 10K today (the equivalent of two week’s worth of practice lately) by ‘swimming with friends.’ I’ll write more about this event in next week’s blog.

From Nov 8 to 11 I will visit Berlin Germany for the first time. We’re planning a meetup—and video tutorial–with TI fans there. If you’re a TI fan near Berlin and would like to join us, please email me at terryswim@gmail.com and I’ll forward info.

The post A Total Immersion Primer: The Why and How of Stroke Drills appeared first on Total Immersion.

November 2, 2016

Be Present During Movement

You’d think one could get badly injured once and learn his lesson, but we are cultural creatures too, and it is deep in our cultural ethos to ‘push through it’. It’s constantly reinforced in all the glory-through-sacrifice we promote in sports, and in the subconscious cues we have been programmed to follow… One needs to work into the discomfort zone to expand his capabilities but discomforts need to be filtered into positive signs of adaptation and warning signs of impending damage…

~~~

To read more of this article visit Coach Mat’s blog Be Present During Movement.

The post Be Present During Movement appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers