Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 11

August 18, 2017

Why I felt gratitude and joy after finishing 48th of 50.

The Betsy Owens Memorial Cable Swim has been my favorite open water event for, well, ever. It’s swum in Mirror Lake, a body of water of unsurpassed beauty in the center of historic Lake Placid NY, with a stunning Adirondack Mountain backdrop. The stainless steel cable, anchored a meter below the surface provides the equivalent of a lane line in open water. The entire field is strung along either side of the cable, rather than dispersed, which gives one far more of a feeling of swimming with your fellow OW enthusiasts. And finally, since 2005, it has memorialized my good friend Betsy Owens, who’d been an energetic, dynamic leader of Adirondack Masters until her death from breast cancer in 2004.

I’ve missed the event only a few times in nearly 20 years, so I really wanted to attend this year. However, I’ve had a challenging few months, swimming-wise. I’ve been tending toward anemia since the spring, possibly because tumors are affecting my bone marrow, hurting red blood cell production.

I first experienced a problem April 7 while swimming the 1000-yard freestyle in a Masters meet in Fairfax VA. Though I swam the first 500 very easily, I still felt breathless and anaerobic as I began the race’s second half. I managed to maintain my pace, giving up less than a tenth of a second per 50-yard interval, via several efficiency-boosting techniques. But I was surprised at this difficulty, as I’d felt fantastic all the way through a 1650-yard freestyle just three weeks earlier in Boston.

Shortly after, I found myself getting out of breath at the beginning of practice, but could create a ‘second wind’ by swimming very short (25 or 50 yards) and easy repeats for the first 10 minutes, then be able to swim longer repeats at a brisker pace over the next 50 minutes. I also felt breathless while walking whenever I had to go up an incline, whether a moderate hill outside, or climbing stairs indoors.

A blood test in early June revealed that my hemoglobin was near the lowest acceptable value of 8.0. My doctors said I would need a blood transfusion if it dropped below 8. I received my first transfusion several weeks later. Since then I’ve received two units of blood at approximately 3-week intervals, as my hemoglobin has dropped to 7.8, then 7.6 and most recently 7.4 within a few weeks of each transfusion. As I write this I’m sitting in Benedictine Hospital in Kingston NY receiving my third transfusion–a process that takes up to six hours each time.

But getting back to Betsy Owens. The event was Aug 12, last Saturday. I’d saved that date all summer. It offers both a 2-mile and a 1-mile event. I’d previously swum the 2-mile every time it was offered. On two occasions I also swam the 1-mile. In 2006, I broke the National Masters 55-59 record for the 1-mile there.

I dearly wanted to swim the 2-mile and entered it on-line two weeks in advance. I’d planned to swim the Steve Belson Memorial Ocean Mile at Rockaway Beach NY on Aug 5. If one mile went well, I’d attempt the 2-mile a week later. However, the Aug 5 event was cancelled because of storm surf, so I lost my gauge of readiness. And I was feeling more anemic as the end of my 3-week transfusion cycle approached, so I asked the organizers to switch me into the 1-mile.

Even one mile was likely to be a stretch. The farthest I’d swum all summer without stopping to catch my breath was 1200 meters, and I’d done that only three times. When I was most anemic I could barely make 200 meters without a break. And I’d swum at Lake Minnewaska—where I ordinarily swim almost every day in summer—only six times all summer, since the hilly half-mile walk to the beach had become quite an ordeal.

I went into the race with modest goals: To complete the event and swim as far as I could continuously. I expected, even with my best effort, to finish at the back of the pack, but to experience gratitude and joy while doing so. My guess-timated seed time of 32:45 for 1500 meters put me in the fifth and slowest-seeded wave of 10 swimmers.

The waves went off at 1-minute intervals, meaning our wave began four minutes after the fastest swimmers. As the horn sounded, most of the swimmers in my wave took off at a pace I dared not try to match. Two swam abreast of me for the first 200 meters. My stroke felt great, but my chest and shoulders were already beginning to fill with lactic acid, forcing me to ease up. For the next 1400 meters I swam alone.

The familiar feeling of breathlessness crept up in the second 200 meters. I focused deeply on taking one stroke at a time, making each stroke count, while seeking as much relaxation as possible. At the 400-meter turnaround, I took four strokes of breaststroke, allowing me a little more air, and a brief glimpse of the mountain backdrop.

The sense of breathlessness relented slightly on the second 400, heading back toward the start/finish line. The three fastest swimmers, now on their final 400 meters, passed me in quick succession on that leg. I admired their swiftness, without a hint of envy, as they went by.

As I began the third 400-meter leg, I rolled over and swam 40 strokes of backstroke, gratefully gulping air as I did. Then I returned to freestyle and—confident that I would finish—grinned widely, which I maintained throughout the second half mile. I crossed the finish line in a time of 42 minutes, 51 seconds—20 minutes slower than the last time I’d swum the mile at Betsy Owens—and placing 48th of 50 swimmers.

I’ve encountered swimmers (and assume this also occurs in running, cycling and triathlon) who find it so difficult to accept the slowing that occurs with age and/or debility that they stop participating. I’ve never considered doing so.

For most of my 50s I placed first in my age group in the majority of open water races, and recorded a ‘podium’ finish in nearly all the rest. I felt deeply satisfied because that success rewarded mastery of critical open water skiils.

But as my times and places have declined I’ve been equally proud and happy. Proud because I must now overcome greater challenges than any swimming rival has posed. Last Saturday, simply swimming continuously for nearly 43 minutes took a formidable combination of technique, focus, cunning and sheer will. (A blood test two days later revealed I was more anemic than at any previous time.)

Happy because participating brings incalculable pleasure and richness into my life. Last Saturday I enjoyed a full day in a setting of great natural beauty with a dozen or more good friends, first while swimming, then at a post-race lakeside picnic, and finally for post-picnic beers at the Lake Placid Brewpub, where we have long had a standing appointment each year after Betsy Owens.

If at all possible, you’ll find me back at Betsy Owens the second Saturday in August 2018.

Beth O’Connor Baker with me immediately after I finished the Betsy Owens 1-mile.

In 1980, I coached Beth O’Connor (Baker) to the Olympic Trials in 200-meter butterfly. Thirty-seven years later, we both swam the Betsy Owens 1-mile and her 20 y.o. son Ryan won the Betsy Owens 2-mile.

The post Why I felt gratitude and joy after finishing 48th of 50. appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 16, 2017

Guest Post: Jumping, Spinning, Swimming, and Coaching at 65

This is another in a series of Wednesday guest posts by TI coaches and enthusiasts. This week’s post, from Vicky Jordan of Pittsburgh, tells of her lifelong relationship with swimming, the powerful healing role it played when she was diagnosed with cancer, and how she became a TI Coach at age 65.

I have been a swimmer pretty much my whole life. I have always felt so comfortable and at home in the water. I can remember when I was a kid my dream was to be able to pitch a tent next to the swimming pool so I could dive in whenever I felt like it! I am also a figure skater – which I absolutely adore. (Still jumping and spinning at my advanced age of 65!!) During the period when I was raising children, I could only pursue one sport intensely, so I chose figure skating. But about eight years ago when we became empty-nesters, I decided to go back to swimming with renewed passion.

I had read about Total Immersion on the internet, and two years ago decided that this technique would give me the grounding and foundation that would help me to keep swimming for the rest of my life. So I found myself a TI coach – Suzanne Atkinson in Pittsburgh – and together we have transformed my swimming. Last January I even passed the TI level 1 Coach Certification Course! I feel so much smoother and coordinated in the water than ever before. And, in fact, I am swimming far more efficiently than when I was much younger and stronger. I feel a new awareness of every part of my body and a new consciousness of how to work with the water instead of against it.

In this sense TI really complements all I have done in figure skating which also requires a very keen awareness of body position. If you don’t know where your legs are and what they are doing in the air, you will never land on the proper edge — 1/16 of an inch of blade – when you land the jump! So I have found that the TI approach to total body awareness is transferable to so many other activities.

Swimming, in fact, was such an important part of my young life. I swam a lot, raced, competed and goofed off in the water as much as I could. But when I was twenty years old, I discovered that the discipline I had learned through swimming could help me through the toughest times. At that time I was very unexpectedly diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

After the surgery I had to undergo many months of radiation treatments and chemotherapy. This was more than 40 years ago, so the drugs available to control the side effects of these treatments were not as sophisticated as they are today. I was very sick a lot of the time, but surprisingly I felt a real drive to get in the water. So I did. And that began a process of using swimming as a way to control what was happening to my body and to my mind.

I am not even sure that I realized this at that moment; it was only in retrospect that I could express what swimming did for me during that time. I went to the pool every day. Even if I could only complete one or two lengths before being sick, I would do it. Some days I could do a full 1000 or even 2000, but most days I could not. But I noticed that each time I got in the water and did what I was capable of doing at the moment, I emerged feeling strong, as if I had some power to control my mental attitude toward what was happening to my body.

My oncologist encouraged me to use swimming in this way. In fact, one Sunday afternoon when I was standing by the side of the pool shivering and nauseated trying to convince myself to jump in, suddenly somebody pushed me in. When I sputtered to the surface and looked up to see who had done this to me, I saw my oncologist who had come to the pool with his family for a Sunday afternoon swim! He looked down at me and, in no uncertain terms said: “Get moving!” and I did.

So now more than four decades later, TI is helping me to increase and improve the coordination of my body in the water so that I can continue to delight in the water for the rest of my life. Suzanne has been the most amazing coach. She represents the ideals of TI: she is patient and encouraging, and always finds new ways of helping me to analyze how I feel in the water. She also knows exactly what I need to do to reach the next level. I am so grateful for the work I have done with Suzanne, and I feel that I am well poised to enjoy swimming for the next 30 years!

Victoria Jordan holds a PhD in Latin and retired last year from 30 years of teaching high school Latin. She and Tom, her husband of 35 years, have an adopted daughter who lives in Brooklyn. Vicky says: “I have been a lifelong athlete. My two greatest loves are swimming and figure skating. My next challenge — which I intend to take up this coming spring — will be rowing in the dragon boat division. TI has given me a focus to swimming that i was lacking. I am very grateful for the serenity it has brought me in the pool. And thanks to Suzanne Atkinson for her support and her inspiration.

The post Guest Post: Jumping, Spinning, Swimming, and Coaching at 65 appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 4, 2017

What book do I recommend most often, and why?

I was recently invited to contribute to a book that will be published at year end. I was asked to select from a list of questions and answer thoughtfully. I selected four questions to answer. The first I chose was “What book have you given most often as a gift, and why?” Here’s my response:

I’ve given about six copies of Mastery by George Leonard as a gift, but have recommended it hundreds of times. I first read this book 20 years ago, after belatedly reading Leonard’s Esquire article from May 1987, the seed from which the book grew. Leonard wrote the book to share lessons from becoming an Aikido master teacher, despite starting practice at the advanced age of 47.

I raced through its 170+ pages in a state of almost feverish excitement, so strongly did it affirm the methods TI was already using to teach swimming. The book helped me see swimming as an ideal vehicle for teaching mastery habits and behaviors closely interwoven with our instruction in the physical techniques of swimming. I love this book because it is as good a guide as I’ve ever seen to a life-well-lived.

Brief Summary:

Life is not designed to hand us success or satisfaction, but rather to present us with challenges that make us grow. Mastery is the mysterious process by which those challenges become progressively easier and more satisfying through practice. The key to that satisfaction is to reach the nirvana in which love of practice for its own sake (intrinsic) replaces the original goal (extrinsic) as our grail. The antithesis of mastery is the pursuit of quick fixes.

My Five Steps to Mastery

Choose a worthy and meaningful challenge

Seek a sensei or master teacher with expertise in that field to help you set out on the right path and establish priorities.

Practice diligently, striving tirelessly to learn or improve key skills and to progress incrementally toward new levels of competence.

Love the Plateau. All worthwhile progress occurs through brief, thrilling leaps forward followed by long stretches during which you feel you’re going nowhere. Though it seems as if you’re making no progress, learning continues at the cellular level. If you follow good practice principles, you are turning new behaviors into habits.

Mastery is a journey, not a destination. True masters never believe they have attained mastery. There is always more to be learned and greater skill to be developed.

The post What book do I recommend most often, and why? appeared first on Total Immersion.

August 1, 2017

Guest Post: How to Participate Healthfully in an Ironman Triathlon on 4 to 6 Hours/Week of Training

This is the second in a series of Wednesday guest posts from TI coaches and enthusiasts. Steve Howard is an ‘avocational’ TI Coach in Lafayette LA.

How in the world did I end up taking part in the Boulder Ironman, with total swim-bike-run training of just 4 to 6 hours a week, of which only one to two hours per month was swim training? My training has been minimal for the past two years, since my wife Debbie was diagnosed and treated for leukemia.

During her treatment, I spent many hours in the hospital with Debbie, participating in her training for recovery, which consisted of hours a day of walking the halls of the hospital together. Since her recovery, we spend our early mornings together. I’ve also had to spend more time focused on our engineering business due to the poor economy

A close friend had signed up for the Boulder Ironman. We decided it would be fun to do the event together and for our families to vacation together in Boulder. One of his daughters was attending pole vaulting school there that week. We attended the camp one of the days. So, three weeks before the Boulder 140.6 Ironman, I signed up for the event.

What can you accomplish on 4 to 6 hours a week of training? I consulted my triathlon coach who lives in Ft. Collins, Colorado. We decided to do a 2-week training build, preceded by a 1-week fitness test, to include a 1-mile open water swim in Indian Creek and two long bike rides.

I’ve only ridden outside a few times in the past three years: I worry about getting run over! The 1-mile swim at Indian creek went surprisingly well. I completed it at a pace of about 2:30 per 100y, which is my normal open water endurance pace.

Steve, holding a Long, Sleek Left-side Line (TI Skate) during pre-race practice.

My first road ride was 63 miles, broken up by 40 min. rest at Rouse’s Grocery Store. A week later I rode 74 miles with 30 min. rest along the way at McDonald’s in Abbeville. I did no running during this time. The primary focus was bike work on the road with an additional 45-min continuous pool swim.

Based on three week’s preparation we thought I had a chance to complete the 2.4-mile swim and ride 70 miles to the bike cut off point. If I finished the 112-mile bike, I would walk 5 miles and stop to avoid injury. Our purpose was to use the Boulder Triathlon as a training event/vacation.

Swimming was the most interesting and rewarding part of my Boulder experience. The week before we arrived, water temperature in the reservoir had been climbing through the mid-50s. On my first of four swims the water was 61-63F which—combined with wetsuit chest restriction and altitude—took my breath away.

I was working harder than I wanted to because of O2 starvation and cold water. In fact, I was on the verge of gasping, as in a panic attack. Solution: I stopped out in the lake to calm down, then slowed way down to a pace that allowed calm relaxed breathing. That turned out to be 3:00/100y.

I think, because I was undertrained, I felt nervous about the 2.4-mile swim cut off. But each day I was able to increase swim pace, without feeling starved for oxygen. By day 4, with the water warmed to 68 degrees, I was able to hold a 2:20/100y pace for 750 yards continuous. I rested on Saturday.

Sunday Race Day

The 2.4-mile swim is always most interesting/fun for me. This was my first race in a long time where I was unsure I could make the time cut off of 2 hours, 20 minutes due to altitude, cold water and six months of swimming only one to two hours per week. I set a goal of finishing in 2 hours 10 min.

When I started the swim, I started my watch, planning to look at it, at the end of the first leg of the swim and see if I needed to increase my pace. But while swimming, I knew I was at an optimal and enjoyable pace that I could hold for the 2.4-mile distance and have enough strength to ride some unknown distance on the hilly bike course.

The Swim Start

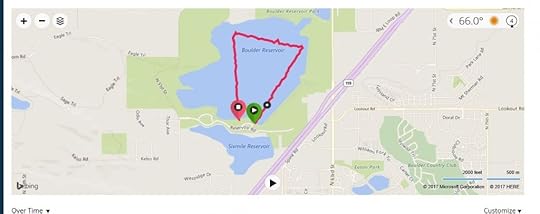

Consequently, I never looked at my watch while swimming. The GPS Swim Track file shows a zig – zag at 1.5 miles, where several inexperienced swimmers swam on top of me, pushing me off course several times. I estimate I lost 3 or 4 mins there. When I got out of the water my time was 1 hour 49 minutes, 20 mins faster than I’d projected. I attribute the better time to the four purposeful and focused days of open water practice.

Steve’s GPS Swim Track

After the swim, I went on to ride the 112-mile bike course at an average of 14 mph on a beautiful green hilly course and then walked 6 miles, at 20 min/mile and called it a day.

The Boulder triathlon was good training for upcoming events and a great test of general health and fitness. Because my coach and I chose for me not to complete the marathon, I left Boulder injury free, gained some fitness, and recovered very fast. In the week following the Ironman, I symbolically finished the 20+ miles of the marathon in several 4- to 6-mile runs at 11:30 to 12:30/mile pace.

The BIM is my second ever DNF. The first was the Pikes Peak 1/2 marathon ascent in 2014. I reached the 14,114’ summit, but missed the time cut off, and so did not receive a finishers medal. That time I also completed the other 13.1 miles of a marathon over the course of a week. In both cases I avoided injuries. The lesson learned was both events were fun adventures with safety nets.

The most important takeaway is “Trust your TI technique and training”. My Total Immersion Swim Knowledge and swim stroke allowed me to complete the Boulder Ironman swim and exceed my age-64 swim goal. Terry, thank you for all you have taught me.

Steve and Debbie Howard live in Lafayette LA, where he is the principal in the engineering firm, Howard Associates International. This week Steve is returning to Boulder, with knowledge and confidence gained from the 140.6 Boulder Ironman, to take part in the 70.3 Boulder Ironman, a 1.2-mile swim, 56-mile bike and 13.1-mile walk/run.

The post Guest Post: How to Participate Healthfully in an Ironman Triathlon on 4 to 6 Hours/Week of Training appeared first on Total Immersion.

July 29, 2017

How to Live a Full and Satisfying Life with Cancer

On October 19 2015, I completed one of my best marathon swims–a strong 10-miler in 64-degree (F) water from Corsica to Sardinia with two friends. Our time of 4 hours 30 minutes included feed stops every 30 minutes. My training—a demanding uphill mountain bike trail ride to a lake atop the Shawangunk Ridge, followed immediately by a brisk 2-mile lake swim, usually completed in under 55 minutes—had indicated that, at 64, my fitness was as good as at any time in my adult life.

On October 19 2015, I completed one of my best marathon swims–a strong 10-miler in 64-degree (F) water from Corsica to Sardinia with two friends. Our time of 4 hours 30 minutes included feed stops every 30 minutes. My training—a demanding uphill mountain bike trail ride to a lake atop the Shawangunk Ridge, followed immediately by a brisk 2-mile lake swim, usually completed in under 55 minutes—had indicated that, at 64, my fitness was as good as at any time in my adult life.

There was one disquieting element during our swim: After the first hour, I was unable to pee, and twice had to climb onto our escort boat to empty my bladder. The previous month during a 10K race at Coney Island in water of the same temperature, I’d had to drop out after completing 5K when discomfort from a full bladder became too great to carry on. This had never occurred previously, even during an 8-hour Manhattan Island Marathon Swim in slightly cooler water.

The reason for my bladder problems became apparent a week later. My physician sent me for a prostate biopsy after sensing irregularities during my annual checkup. The biopsy revealed that I had prostate cancer. My ‘Gleason’ score of 4 + 3 indicated an aggressive variety requiring immediate treatment. A bone scan a month later carried more sobering news: The cancer had metastasized to my pelvis, putting it in the stage IV category. I wondered how I’d gone from being in the shape of my life to having an incurable, life-threatening illness in a matter of weeks.

The original plan for prostate surgery was shelved. I began treatment with testosterone-blocking hormones. Doctors typically expect one to two years of cancer suppression from this treatment. My cancer resumed its advance in the second month, which my oncologist described as “the far side of bad news.” A week later, I began chemotherapy.

Around that time, I had a 26-hour dizzy spell. A brain scan to learn the cause showed that I’d had a small stroke—a known side effect of prostate cancer. The stroke left me with blurred vision and feeling unsteady on my feet. This immediately became a more pressing concern than cancer as it threatened to limit mobility and leave me unable to read or write.

These were only the beginning of a series of discouraging occurrences:

Between April and October, I received eight (of a planned 10) monthly infusions of Docetaxel, a chemotherapy drug. Blood tests showed an encouraging response the first two months. In the third month, critical markers began creeping in the wrong direction again, growing to alarmingly large reversals in months seven and eight.

With the cancer progressing rapidly, my oncologist switched me to monthly injections of Xofigo (radium 223), which more directly targets tumors in bone. Like the previous ‘standard of care’ treatments, this stabilized my condition (at its new more-threatening level) for a few months, until lab tests conducted when I received my fifth treatment indicated that my tumors were again growing rapidly.

Though the doctors had scrupulously avoided any mention of mortality rates for my cancer type, the radiologist who administered Xofigo gave me a pamphlet describing how it worked. Perhaps he didn’t realize it included this sobering statistic: Men receiving this treatment typically saw average survival time increase from 24 to 30 months.

Thus far this ‘cancer chronicle’ has read like a fairly standard account of how someone’s life is upended by an aggressive disease which quickly develops resistance to everything the doctors throw at it. But there’s another side.

Taking Charge

Immediately after the stroke, I shifted to a plant-based diet and began to practice meditation and the Chinese healing art of qi gong, during which I visualized the free flow of qi throughout my body. During yoga classes, I visualized the flow of healing prana throughout my body. I adopted these ancient healing practices and visualizations to lower my blood pressure and promote circulatory health to heal the effects of my stroke and prevent a recurrence.

Within weeks, my blood pressure was lower than at any time during my adult life and the effects of the stroke began to ameliorate. Three months later, my vision was clear and I was again steady on my feet. This experience strengthened my resolve to be an active, empowered participant in healing myself, rather than a passive patient, awaiting treatment.

Reading the Xofigo pamphlet was the first documentary evidence I’d had of my situation’s significant gravity. As with previous discouraging revelations, I experienced anxiety for a day or two then regained emotional equilibrium. I shared this news with my friend Mike Joyner M.D., an anesthesiologist/exercise scientist at the Mayo Clinic. He said, “With all survival projections, there’s a ‘long tail’ of people who survive far longer than average. The strongest predictor for being in that cohort is your state of health at the time of diagnosis and how healthy you remain during treatment.”

As I started chemotherapy, I’d seen an Australian TV documentary about a rigorous study of the effects of exercise during cancer treatment. Subjects who did regular cardiovascular and strength training survived twice as long as sedentary patients. I resolved to swim, do yoga, or lift weights nearly every day, including days I received a chemo infusion.

Illness-Free Zone

In 2010-2011, I’d been privileged to witness a remarkable phenomenon when one of my students, Dr. Jeanne Safer, was diagnosed with breast cancer then—shortly after being declared cancer-free, received a diagnosis of leukemia, unrelated to the breast cancer. During two years in treatment, Jeanne rarely ever missed our weekly lesson. She would come to our Swim Studio directly from a treatment session. Though she walked in each time looking utterly drained, she would regain energy and vitality during our hour together. Jeanne referred to the pool as her ‘illness-free zone.’

I experienced the same thing during 18 uninterrupted months of treatments that were often harsher in their effects than the disease. Though I often felt tired or ill, a stunning transformation would occur while taking yoga class or practicing swimming. Especially while in the pool or lake, I would feel vibrant health.

I’d felt a passion for swimming since adopting a kaizen (continuous improvement) ethos in the early 1990s. Now my gratitude for the ability to swim with flow and grace became boundless. I would feel a magical connection to the water with every stroke. I also brought to swimming the habit I’d learned from yoga and qi gong, visualizing healing energy flowing through my body with every stroke.

Since my mid-50s, when I’d reached my (age-adjusted) lifetime performance peak, I’d learned to embrace my physical self—with its gradually diminishing capabilities and increasing limitations through my late 50s and early 60s. That process became dramatically concentrated after my diagnosis and the onset of treatment. It seemed as if I experienced 10 or more years of loss of speed and lessening of endurance in just over a year.

Yet my sense of purpose and the pleasure I took from swimming became, if anything, greater. Even as I proceeded to set new ‘lifetime slowest’ marks in my favorite races and repeat times on almost a monthly basis, I never became complacent about trying to eke out the best performance of which I was capable.

In March 2016, I swam 1650 yards (equivalent of 1500scm) two minutes slower than I’d ever swum it before, yet in an Adirondack Masters 60-64 record time of 23:10. I described it in this blog as the most satisfying race of my life, because of the absolutely unwavering concentration it demanded.

In November, despite training just 3000 to 4000 yards per week, I completed two 10K swims on consecutive days in the Red Sea with Total Immersion Israel. Though I tired after 8K on the first, I finished the second with abundant energy. I told those who swam with me that it was the best day of my life.

In December, I swam 1650 in a time of 26:57, nearly four minutes slower than previously, yet good enough for an Adirondack 65-69 record and equally satisfying because the time was possible only because of several energy-saving adjustments I’d refined as my endurance and strength went south.

Since April, I’ve been in a clinical trial of an experimental treatment from Germany that, at the moment, seems to be working. I’ve had less pain, fewer days feeling ill, and more energy than in many months. I have no time for anxiety, anger over my situation, nor fear of the future. I’m far too preoccupied with taking pleasure from a glorious season of open water swimming, yoga classes, and my work, creating new TI content. In fact, I’ve been more productive, engaged in—and excited by—writing and video production the past year than at any time in the almost 30 years since I started TI.

Life is good!

The post How to Live a Full and Satisfying Life with Cancer appeared first on Total Immersion.

July 25, 2017

Guest Post: Reconciling Your Solid With That Liquid (A Satisfying Open Water Practice)

Last Sunday I’d planned to join my close friend and fellow swim-explorer Lou Tharp for an open water group practice at West Neck Beach on Long Island’s North Shore, but an allergic reaction to a wasp sting got in the way. Lou wrote me an email about the practice that I so thoroughly enjoyed reading, that I asked him to write a guest post for my blog. This is the first in a series of posts by guest writers we’ll publish on Wednesdays for several weeks. Enjoy.

Getting in the water without getting into a cooperative mindset first is the definition of taking a shower. And I wasn’t at West Neck Beach on the North Shore of Long Island last Sunday to take a shower.

I was looking at 2800 meters of still, high-70-degree water punctuated with four buoys in a straight line, scattered pleasure boats at anchor, and the signature North Shore rocky beach that meant you could ouch your way into the water barefoot or hope your flip flops didn’t get washed away with the tide while you were swimming.

The important part was that I was looking at it—approximately 2,800 meters if I went around the buoys twice. Even though I swim 15,000 yards a week and compete in open water and pool races, there has to be time and mental space before each swim for fear and respect on the way to recognition that water is your partner not your antagonist. It’s not a matter of muscle over mind – this pre-swim reconciliation of your solid and that liquid – it’s the aquatic equivalent of performer’s stage fright the way Greg Allman described it: “Stage fright is not a thing about ‘Am I any good?’ It’s about ‘Am I gonna be good tonight?’ It’s a right-now thing. It helps me. If I went out there thinkin’, ‘Eh, we’ll go slaughter ‘em,’ I’m positive something would go seriously wrong.”

Something can “go seriously wrong” more often than we want to admit in open water swimming, but while drowning is usually that something we automatically think of, it’s more often the serious mistake of not finding your comfortable place even within still water while swimming with (not racing) 65 other people. The visual is not the synchronicity of a school of fish. It’s more like paying eight quarters to look at your underwear through the washing machine window. But I need to be the fish, not the Calvins.

The first signal of reconciliation is the appropriate heart rate. That morning, an organized practice for the August 6 West Neck open water event, my heart rate was in the low 50s as I used the 50-meter swim to the start buoy as a pre-check that I was enjoying sliding through the water quietly. Too many people had brought their chatter into the water as we waited at the buoy to start. Bringing chatter and a high heart rate to the start of a practice or a race is like bringing a stomach full of pasta to a marathon. It only feels good before. In a pool, you can jabber your way (on a kick-board) through a kick-set, or race the first 100 yards as your warm-up, then stand in 3.5-foot water and reboot. There’s no standing, and usually no 3.5-foot water in open water swimming, and definitely no reboots, so this whole chatter/high-heart-rate thing has to be re-examined.

On August 6, race day, I would be on an ocean-swimming holiday at Rehoboth Beach, so this practice was for a half-iron relay I’d be doing October 1at Montauk, Long Island, when the weather would be colder, the water rougher and my heart rate higher. This practice was to practice doing what trout do in a stream – cooperatively gliding through the current. Montauk would be more like salmon in spawning season – finding a way upstream through the rushing Columbia River heading for their home streams. But salmon don’t have to sight the way we do.

Open water swimming is anticipating and then dealing with challenges. The first one Sunday morning was sighting. Sighting can severely disrupt balance or it can allow breathing, seeing, and energizing in a smooth motion. That didn’t happen during the first 500 meters. The first clue that I was losing balance as I sighted was an unruly kick. Once I began to sight less – every 10-15 strokes – and raise my head just enough to get a visual whiff of a buoy or a group of swimmers, my kick settled down to a productive two-beat and I wasn’t chasing speed or the swimmers ahead. Both came back to me.

I have no idea how much time the swim took because it wasn’t a race. I think in practice it’s more important to spend time than to measure it. And I spent time learning and relearning how to swim, finding the right muscle memory before the wrong muscle activation.

The result:

I swam faster and had more energy at the end than at the beginning.

For the final three-quarters of the swim, I effortlessly caught and passed other swimmers.

I could have swum another 2,800 meters and another 2,800 after that.

I was in peaceful, focused control.

Louis Tharp, who began swimming at 45, is the former swim coach for the West Point triathlon team, a medalist in open water and pool competitions, and executive director of the Global Healthy Living Foundation. His book, “Overachiever’s Diary, how the Army triathlon team became national contenders,” is available at

http://www.totalimmersion.net/store/books/overachiver-s-diary.html

. Reviews and other information is available at

http://www.overachieversdiary.com/

. He can be reached at LTHARP@overachieversdiary.com

The post Guest Post: Reconciling Your Solid With That Liquid (A Satisfying Open Water Practice) appeared first on Total Immersion.

July 24, 2017

Race Analysis: How Did Katie Ledecky Pace Her World Championship 400m?

The FINA World Swimming Championships began yesterday in Budapest. During the weeklong event I’ll post analysis of the pacing patterns of the three top swimmers, the medalists, in certain races.

Ever since I began coaching 45 years ago, one of the most instructive things I’ve done has been to study the pacing patterns of the world’s best swimmers. When I coached swimmers in all events I studied pacing patterns for all events. These days those I coach are most interested in the distance events. Thus, over the next several days, I’ll blog about the pacing patterns of the mens’ and womens’ 400m, 800m, and 1500m freestyles.

The mens’ and womens’ 400m freestyle was swum yesterday. Here are the final times and 200m splits of the medalists, as well as the world record holder

Womens 400m Freestyle

World Record

Katie Ledecky USA 3:56.46 (1:57.11—1:59.35) +2.2 sec

World Championships Finals

1st Katie Ledecky USA 3:58.34 (1:57.74—2:00.60) +2.8 sec

2nd Leah Smith USA 4:01.54 (1:59.55—2:00.99) +1.4 sec

3rd Li Bingjie CHN 4:03.25 (2:00.42—2:02.83) +2.4 sec

Mens 400m Freestyle

World Record

Paul Biedermann GER 3:40.07 (1:51.02—1:49.05) -2 sec.

World Championships Finals

1st Sun Yang CHN 3:51.48 (1:50.87—1:50.61) -0.2 sec.

2nd Mack Horton AUS 3:43.85 (1:51.83—1:52.02) +0.2 sec

3rd Gabriele Detti ITA 3:43.93 (1:52.31—1:51.62) -0.6 sec

The interesting pattern here is that the men mostly swam negative splits—i.e. swam the second half of the race faster, while the women swam positive splits, averaging about 2 second slower on the second 200 than on the first.

These splits are all excellent. Very few swimmers can swim the 2nd 200 of a 400 within 3 seconds of the first 200. However historically—dating back 40 years or more—elite swimmers’ pacing patterns were more like the mens’ pacing was yesterday, even split to swimming the 2nd 200 a fraction of a second faster than the 1st 200. This has prevailed because it delays a buildup of lactic acid in the muscles until very late in the race.

Why are the women swimming atypically faster in the first half of the 400m now? My best guess is that it’s because Katie Ledecky is such a dominant swimmer and goes out faster than anyone else is capable of. I believe the other women are pulled along, trying not to be left impossibly far behind.

What’s your guess?

The post Race Analysis: How Did Katie Ledecky Pace Her World Championship 400m? appeared first on Total Immersion.

June 27, 2017

Does Katie Ledecky Swim TI Style?

19 year old swimming legend Katie Ledecky

66 year old TI Founder Terry Laughlin

Katie Ledecky has has had a busy week at the FINA World Swimming Championships in Budapest, which conclude this weekend. So far she has won four gold medals, in the 400m and 1500m freestyles plus the 4 x 100 and 4 x 200 free relays. She also finished 2nd to world-record-holder Federica Pellegrini of Italy in the 200m free. Her final race, the 800m free, in which she is

A question we often hear is: “Does [prominent elite swimmer] swim with TI Technique?”

Our standard response is: “We take no credit for the technique of [prominent elite swimmer]. They learned it from their coaches and developed it over many years. Which is certainly true of Katie Ledecky

However: We strive continuously to refine TI technique and ensure that it’s on the cutting edge. We spend much time studying the technique of the world’s best swimmers—in all strokes—looking for aspects of their form that are not limited to those with youth or special athletic gifts, but are learnable by all.

In the screenshot at top from one of Katie’s races last month at the World Championship Trials, we can identify points of technique that are precisely the same as those we teach. Moving from front to rear, they are

Her sloped leading arm with a flexed wrist, and hand below the deepest part of the body as she applies initial pressure on the water.

Her ‘hidden’ (mostly submerged) head, aligned with her spine.

Her left arm forward of her head, poised to enter the water, while right hand is still forward of her head.

Her upper torso rotated OFF her stomach (not ON her side).

Her left hip poised to drive down and propel her past her right-hand-grip.

Now compare with the screenshot of 66 y.o. TI Head Coach Terry Laughlin and ask yourself “Does Katie Ledecky swim with TI technique.” The correct answer is that TI teaches techniques that made her the best freestyler in the world.

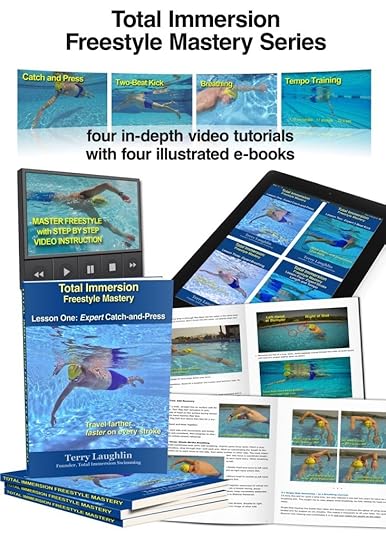

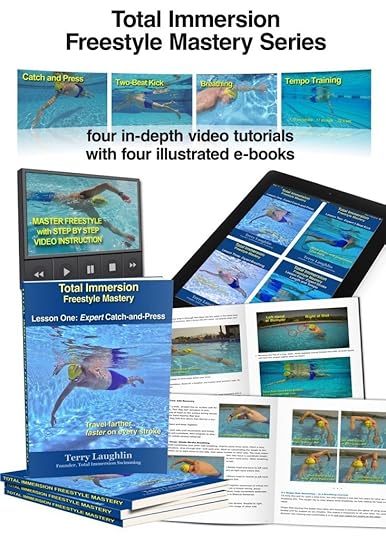

You can learn all five of the technique points listed above in our 1.0 Effortless Endurance and 2.0 Freestyle Mastery downloadable Self Coaching Courses and Workshops.

The post Does Katie Ledecky Swim TI Style? appeared first on Total Immersion.

Does Katie Ledecky Swim with TI Technique?

19 year old swimming legend Katie Ledecky

66 year old TI Founder Terry Laughlin

We often hear the question: “Does [insert the name of a prominent elite swimmer] swim with TI Technique?”

We always answer: “We take no credit for the technique of [prominent elite swimmer]. They learned it from their various coaches and developed it over many years . . .

However: We strive continuously to refine TI technique and ensure that it’s on the cutting edge. We spend much time studying the strokes of the best swimmers in the world looking for aspects of their form that are not limited to those with youth or special athletic gifts, but are learnable by everyone.

In this screenshot taken from one of 19 y.o. Katie Ledecky’s impressive races, we can identify points of technique that are precisely the same as we teach. Moving from front to rear, they are

Her sloped leading arm with a flexed wrist, and hand below the deepest part of the body as she applies initial pressure on the water.

Her ‘hidden’ (mostly submerged) head, aligned with her spine.

Her left arm forward of her head, poised to enter the water, while right hand is still forward of her head.

Her upper torso rotated OFF her stomach (not ON her side).

Her left hip poised to drive down and propel her past her right-hand-grip.

Now compare with the screenshot of 66 y.o. TI Head Coach Terry Laughlin and ask yourself “Does Katie Ledecky swim with TI technique.”

We teach all of these techniques in our 1.0 Effortless Endurance and 2.0 Freestyle Mastery downloadable Self Coaching Courses and Workshops.

The post Does Katie Ledecky Swim with TI Technique? appeared first on Total Immersion.

June 23, 2017

How to Get Better at Things You Care About: Explore your Performance Zone.

This week I received one of the regular messages sent by my good friend, Michael Bryant of Baltimore MD. Mike and wife Nancy have been TI students since 2008, having attended several TI workshops and camps. When they started with TI, Michael tore down the way he’d been swimming for 48 years and relearned from the bottom up. Nancy had never swum before.

Since then, Michael has completed six Ironman Lake Placid’s. Nancy has completed over 20 Sprint and Olympic distance tris. Michael says, “We are both dedicated to a healthy life style and TI practice is a bedrock of that life style.”

Michael heads his messages to me “From the Aqua Lab,” which is the term he applies to their practices, since both are committed to the Kaizen ideal of helping each other improve continuously—often via curious exploration.

Mike and Nancy at Lake Placid.

Michael’s latest message:

The other day in the Aqua Lab Nancy and I worked on technique. We alternated short reps of Superman to improve Balance with 25-yd reps of whole stroke, focused on Stroke Length. Nancy—who once needed 37 strokes to cover 25 yards—was easily holding half that number. However, I’d lately noticed Nancy had a “hitch” as her arm entered water.

I recalled a recent blog post of yours about bilateral breathing, where you mentioned a focal point of having “the chin follow the shoulder to air.” I reminded Nancy of that and the change was instantaneous and amazing.

Though Nancy had informed me at the start of practice that she would be doing no “speed” work, her form was looking so sleek and she was clearly moving faster that I suggested I time her for a few 50s.

I shared John Wooden’s quote, “Be quick but don’t hurry.”

Nancy’s times for 3 x 50 were 1:07, 1:06, and 1:03. This is the fastest she has ever swum! She was SO excited about her progress.

PS: Two days later Nancy did 3 x 50 in 1:02, 1:02, and 1:02. The 1:00 mark is about to fall! ( I focused on the Rag Doll Arm arm on my 50s and lowered my time from 50 to 48 seconds.)

PPS: We understand that time is only one metric and it’s all really just information, but this sure was fun!

I was as excited personally as Nancy and Michael because:

Nancy figured out how to improve her speed (i.e. strike the right balance between SL and SR) repeatedly and cumulatively quite a bit; and

Their practices exemplify an improvement principle I have only recently come to recognize.

Train in the Right Zone

Previously I’ve written that, in a Kaizen approach to swimming, there are three possible categories or ‘zones’ into which all your practice activities can fall:

Comfort Zone: In this zone, you don’t tax or stretch your capabilities or skills. You stay with activities that are familiar and those you consider your strengths. This zone requires relatively little effort, discipline, or focus.

Learning Zone: In this zone, you seek to strike a delicate balance between your present capabilities and the difficulty of your task. You focus on finding and fixing weak spots. This is quite demanding mentally—but not always physically. Falling slightly short of your goal—just enough to feel success is simply a matter of time and patience—is good. That means you’ve got the skills-challenge balance right.

Failure Zone: If you fall hopelessly short—experiencing only frustration—you need to rebalance the challenge of what you’re trying to better match your current skill level.

If you are purely oriented to the quality of your swimming experience, or lifelong learning as a swimmer (which many TI swimmers are), you could fruitfully spend all of your practice time in the Learning Zone. However . . .

Stretch Beyond Your Present Capabilities

Recently—after reflecting on my practice habits since my early 50s—I recognized the value of a fourth category.

The Performance Zone. In this zone, you swim a time trial or speed-oriented set; enter an open water event or Masters meet, or perhaps train with a Masters or other coached group.

The stakes are higher, the measurement standard more rigorous, and you may accept the possibility of slight decline from usual standards in efficiency (sense of ease or control, or SPL) in order to match or exceed a previous speed standard; or measure up to other swimmers of your ability or greater.

Ideally you would spend most of your time in the Learning Zone, then test or apply what you’ve learned there during brief ventures into the Performance Zone.

This is precisely what Nancy and Michael did this week. In these practice, which I guesstimate were 45 or more minutes, they spent 90% or more of time and volume in Learning Zone and the final five minutes of each practice in Performance Zone.

But the self-realization value of that brief time in Performance Zone was probably greater than the rest of the practice.

In next week’s post, I will share detailed suggestions on how to expand on Nancy’s simple set of 3 x 50 to seamlessly blend Learning and Performance zone experiences in one extended set.

Lesson 4 of our 2.0 Freestyle Mastery Self-Coaching Course focuses on how to strike the right balance between Learning and Performance Zone.

The post How to Get Better at Things You Care About: Explore your Performance Zone. appeared first on Total Immersion.

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers