Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 104

May 15, 2018

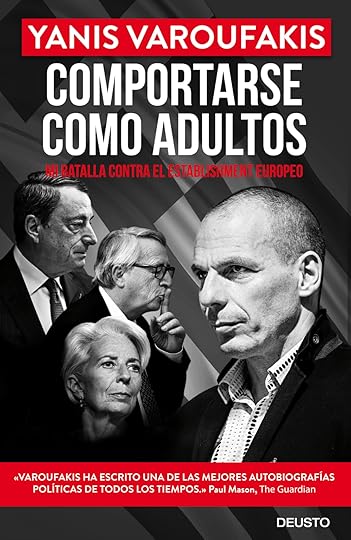

EL PAIS: COMPORTARSE COMO ADULTOS: El exministro de Finanzas griego ha publicado un libro sobre las entretelas de la política europea

Polémico. Atractivo. Brillante. Controvertido. Los seis meses de Yanis Varoufakis(Atenas, 1961) al frente del Ministerio de Finanzas de Grecia lo convirtieron en una celebridad global, en una suerte de estrella del rock de la política económica. Sus detractores lo caricaturizan como un extremista medio chiflado de izquierdas —según su propia definición—, enamorado de las motos potentes, de los restaurantes chic, de las chaquetas de cuero y del glamour de las islas griegas. La troika afirma que su gestión le costó a Grecia 100.000 millones de euros.

Lo más suave que dicen sus críticos es que se trata de un intelectual cuya inmersión en la política, más allá de la fama, puede calificarse como mediocre. Varoufakis acaba de responder a sus censores con un ejercicio de funambulismo literario: Comportarse como adultos, que en España acaba de publicar Deusto, ofrece una mirada única a las entretelas de Bruselas y es, sin duda, uno de los libros del año. A lo largo de 700 suculentas páginas se explica, asume algunos errores y, sobre todo, salda cuentas pendientes con una prosa de gran altura que incluye sonoros disparos a diestro y siniestro. El exministro conserva una lengua venenosa y es dueño de un análisis demoledor para Europa. “No se engañen, la crisis sigue ahí; el euro corre peligro”, embiste en una entrevista realizada con este periódico.

Europa crece a un ritmo superior al 2%. El paro ha bajado de la cota del 9%. Los déficits mejoran. Los populismos acechan, pero de momento siguen quedándose a las puertas de llegar al Gobierno en los grandes países. Las instituciones europeas presumen, en fin, de recuperación. Sin embargo, Varoufakis desdeña todo eso —“Una reactivación cíclica”, lo llama— y brinda un mal dato por cada dato bueno. Y, sobre todo, esboza un relato mucho menos complaciente que el de las élites de la UE.

“En la fase más aguda de la crisis del euro, hubo serios riesgos de fragmentación. El BCE supo contenerlos, pero las amenazas aún existen, aunque adopten otras formas: el Brexit, una Alemania que no logra formar Gobierno, la extrema derecha en Austria, Cataluña, el hundimiento del bipartidismo en Francia y los reflejos autoritarios en Europa del Este son claros síntomas de un malestar profundo. Las grandes crisis son momentos de revelación de las fallas del sistema: en Europa le hemos visto las costuras al euro y si nada cambia la amenaza es el hundimiento gradual de lo que solíamos llamar democracia liberal”.

Una situación como la de 2001

¿Lo peor ha pasado? No. Varoufakis, que ha fundado un nuevo partido (DiEM 25) para luchar contra ese malestar, se ríe cuando se le recuerda que el apocalipsis casi siempre defrauda a sus profetas: “Los análisis más pesimistas, entre ellos los míos, no han fallado en los últimos años; lo siento, pero es así”. ¿Lo peor ha pasado, al menos? “La situación actual me recuerda a la de 2001: veníamos de veinte años de encadenar burbujas, estalló la de las puntocom, y aun así nos las arreglamos para seguir igual y provocamos una crisis aún más grave con una burbuja aún mayor que estalló en 2008. Corremos el riesgo de volver a las andadas. En España, la deuda total va al alza. En Italia hay fuga de capitales, una crisis bancaria en ciernes, una situación política explosiva. Lo que tenemos en Grecia no puede llamarse recuperación, y la deuda es impagable. Los ejemplos son inagotables. En toda la periferia hemos cambiado empleos a tiempo completo por trabajos precarios, y con ello se ponen en peligro las pensiones futuras y las bases de la economía europea. Los desequilibrios financieros y macroeconómicos no solo no se han reducido, sino que son incluso mayores: me temo que no estamos para celebraciones. El euro, tal como está hoy, es insostenible”.

“Lo más preocupante”, acaba el griego, “es el bajo nivel de inversión y las divergencias crecientes en la zona euro. Sin inversión y sin convergencia es imposible hablar de fin de la crisis. Europa sigue metida en una: 10 años después de [la caída de] Lehman Brothers, somos incapaces de reforzar la arquitectura del euro y la moneda, contra lo que decían sus impulsores, es una fuente de incertidumbre. Europa es muy rica y puede mantener ese euro con pies de barro durante un tiempo, pero a la larga, créame, las costuras saltarán”.

Errores y maldiciones. Varoufakis se retrata a sí mismo como una suerte de héroe trágico en su libro. Alude a algunos de los errores que cometió como miembro del Gobierno de Alexis Tsipras, aunque su capacidad de autocrítica no está a la altura de su talento literario. Y aun así merece la pena prestar atención a su análisis. “Grecia no podía aceptar ningún acuerdo sin reestructurar su deuda, que era y es insostenible. Pero a los acreedores no les interesaba que pagáramos: simplemente querían dar una lección a Grecia como aviso a otros países. Al final, desgraciadamente, Tsipras capituló. En el póquer, si tienes malas cartas, solo tienes una posibilidad de ganar si tu farol es creíble y lo mantienes hasta el final, pero si crees que el oponente no va a retirarse no deberías jugar. Estoy orgulloso del auténtico susto, aunque breve, que se llevó la troika. Pero no supimos resistir”. “Nuestra derrota tuvo unos costes enormes”, admite en el libro. “Maldigo a mi Gobierno por no haber resistido”, añade durante la conversación.

Guindos: “Es uno de ellos”. Varoufakis critica con suma dureza a la Comisión Europea —“El Eurogrupo y hasta el grupo de trabajo del Eurogrupo mandan mucho más”—. Atiza sin miramientos a Tsipras, a Jean-Claude Juncker, a Pierre Moscovici, a Jeroen Dijsselbloem, a muchos otros. A lo largo de Comportarse como adultos apenas salva al ministro alemán Wolfgang Schäuble, que llegó a proponer la salida de Grecia del euro. Su análisis sobre Luis de Guindos está plagado de claroscuros: “Hablamos el mismo idioma porque Guindos, a diferencia de la gran mayoría del Eurogrupo, sabe de economía. Tuvimos interesantes discusiones, y a puerta cerrada estábamos más o menos de acuerdo. Pero en las reuniones Luis mantuvo posiciones indignantes: su primer objetivo era castigar a Grecia para penalizar a Podemos. Y siempre era el primero en darle la razón a Schäuble. Con él me pasó lo que con tantos otros: podía llegar a posiciones comunes en privado, pero a la hora de la verdad no servían de nada: eso es democráticamente deshonesto”. ¿Le ve con opciones al BCE? “Viene de la banca de inversión, como Mario Draghi. Tiene buenos fundamentos económicos. Y lo más importante: es uno de ellos”, remacha el exministro.

Egos revueltos. Varoufakis explica de forma pormenorizada en su nuevo libro qué significa ser uno de ellos a través de una conversación con el influyente Larry Summers, exasesor de Barack Obama y exsecretario del Tesoro con Bill Clinton. “Hay dos clases de políticos: los que ven las cosas desde dentro y los que prefieren quedarse fuera, los que prefieren ser libres para contar su versión de la verdad. El precio que pagan por su libertad es que los que están dentro, los que toman las decisiones importantes, no les prestan la menor atención. Los que viven las cosas desde dentro deben acatar una ley sacrosanta: no ponerse en contra de los que están dentro, no contar lo que sucede. ¿Cuál de los dos eres tú?”, le pregunta Summers. Varoufakis lo deja claro a lo largo de más de 700 páginas. Graba y transcribe reuniones, cuenta pormenores de decenas de entrevistas con líderes mundiales, pone sobre la mesa hasta el último y sonrojante detalle.

Yanis Varoufakis consigue reírse de sí mismo, aunque se las arregla para quedar bien casi siempre. Y mantiene el pulso literario de un volumen largo que tiene hechuras de novela negra y de drama shakespeariano. Pero sobre todo de tragedia griega. Porque a pesar de sus torrenciales explicaciones, el lector no alcanza a explicarse cómo Tsipras, Varoufakis y los suyos no consiguieron ni acercarse a lo único que importa: el mejor acuerdo posible para Grecia.

MARIO DRAGHI, EL “DÉSPOTA TRÁGICO”

Varoufakis nunca quiso salir del euro: su posición fue reclamar una reestructuración de la deuda pública griega (en torno al 180% del PIB: un nivel “insostenible”, según el FMI) y objetivos fiscales asumibles. Su estrategia era amenazar con un impago, y tener listo un sistema de liquidez alternativo si (como sucedió) los acreedores provocaban un cierre de los bancos.

En el momento clave, junio de 2015, el primer ministro, Alexis Tsipras, se echó atrás, y el BCE precipitó el final del drama. Varoufakis carga con suma dureza contra el Eurobanco (“el banco central más politizado del mundo”) en su libro. Califica a Draghi como “déspota trágico”. Le acusa de forzar la mano con “vergonzosas amenazas”. “Los abusones culpan a sus víctimas. Los abusones listos consiguen que la culpabilidad de sus víctimas parezca evidente. […] El BCE demostró una habilidad especial en esta última técnica”, dispara el exministro. Draghi, según esa versión, le obligó a cerrar la banca y le forzó a aceptar más austeridad, en un país que ha recortado las pensiones varias veces, prohibido la negociación colectiva y donde solo el 8% de parados recibe algún subsidio.

Marx predicted our present crisis; and points the way out – The Guardian, LONG READ, 20 APR 2018, print and audio versions

For a manifesto to succeed, it must speak to our hearts like a poem while infecting the mind with images and ideas that are dazzlingly new. It needs to open our eyes to the true causes of the bewildering, disturbing, exciting changes occurring around us, exposing the possibilities with which our current reality is pregnant. It should make us feel hopelessly inadequate for not having recognised these truths ourselves, and it must lift the curtain on the unsettling realisation that we have been acting as petty accomplices, reproducing a dead-end past. Lastly, it needs to have the power of a Beethoven symphony, urging us to become agents of a future that ends unnecessary mass suffering and to inspire humanity to realise its potential for authentic freedom.

[TO LISTEN TO THIS ARTICLE BEING READ OUT, CLICK HERE]

No manifesto has better succeeded in doing all this than the one published in February 1848 at 46 Liverpool Street, London. Commissioned by English revolutionaries, The Communist Manifesto (or the Manifesto of the Communist Party, as it was first published) was authored by two young Germans – Karl Marx, a 29-year-old philosopher with a taste for epicurean hedonism and Hegelian rationality, and Friedrich Engels, a 28-year-old heir to a Manchester mill.

As a work of political literature, the manifesto remains unsurpassed. Its most infamous lines, including the opening one (“A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism”), have a Shakespearean quality. Like Hamlet confronted by the ghost of his slain father, the reader is compelled to wonder: “Should I conform to the prevailing order, suffering the slings and arrows of the outrageous fortune bestowed upon me by history’s irresistible forces? Or should I join these forces, taking up arms against the status quo and, by opposing it, usher in a brave new world?”

For Marx and Engels’ immediate readership, this was not an academic dilemma, debated in the salons of Europe. Their manifesto was a call to action, and heeding this spectre’s invocation often meant persecution, or, in some cases, lengthy imprisonment. Today, a similar dilemma faces young people: conform to an established order that is crumbling and incapable of reproducing itself, or oppose it, at considerable personal cost, in search of new ways of working, playing and living together? Even though communist parties have disappeared almost entirely from the political scene, the spirit of communism driving the manifesto is proving hard to silence.

To see beyond the horizon is any manifesto’s ambition. But to succeed as Marx and Engels did in accurately describing an era that would arrive a century-and-a-half in the future, as well as to analyse the contradictions and choices we face today, is truly astounding. In the late 1840s, capitalism was foundering, local, fragmented and timid. And yet Marx and Engels took one long look at it and foresaw our globalised, financialised, iron-clad, all-singing-all-dancing capitalism. This was the creature that came into being after 1991, at the very same moment the establishment was proclaiming the death of Marxism and the end of history.

Of course, the predictive failure of The Communist Manifesto has long been exaggerated. I remember how even leftwing economists in the early 1970s challenged the pivotal manifesto prediction that capital would “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere”. Drawing upon the sad reality of what were then called third world countries, they argued that capital had lost its fizz well before expanding beyond its “metropolis” in Europe, America and Japan.

Empirically they were correct: European, US and Japanese multinational corporations operating in the “peripheries” of Africa, Asia and Latin America were confining themselves to the role of colonial resource extractors and failing to spread capitalism there. Instead of imbuing these countries with capitalist development (drawing “all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation”), they argued that foreign capital was reproducing the development of underdevelopment in the third world. It was as if the manifesto had placed too much faith in capital’s ability to spread into every nook and cranny. Most economists, including those sympathetic to Marx, doubted the manifesto’s prediction that “exploitation of the world-market” would give “a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country”.

As it turned out, the manifesto was right, albeit belatedly. It would take the collapse of the Soviet Union and the insertion of two billion Chinese and Indian workers into the capitalist labour market for its prediction to be vindicated. Indeed, for capital to globalise fully, the regimes that pledged allegiance to the manifesto had first to be torn asunder. Has history ever procured a more delicious irony?

Anyone reading the manifesto today will be surprised to discover a picture of a world much like our own, teetering fearfully on the edge of technological innovation. In the manifesto’s time, it was the steam engine that posed the greatest challenge to the rhythms and routines of feudal life. The peasantry were swept into the cogs and wheels of this machinery and a new class of masters, the factory owners and the merchants, usurped the landed gentry’s control over society. Now, it is artificial intelligence and automation that loom as disruptive threats, promising to sweep away “all fixed, fast-frozen relations”. “Constantly revolutionising … instruments of production,” the manifesto proclaims, transform “the whole relations of society”, bringing about “constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation”.

For Marx and Engels, however, this disruption is to be celebrated. It acts as a catalyst for the final push humanity needs to do away with our remaining prejudices that underpin the great divide between those who own the machines and those who design, operate and work with them. “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned,” they write in the manifesto of technology’s effect, “and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind”. By ruthlessly vaporising our preconceptions and false certainties, technological change is forcing us, kicking and screaming, to face up to how pathetic our relations with one another are.

Today, we see this reckoning in millions of words, in print and online, used to debate globalisation’s discontents. While celebrating how globalisation has shifted billions from abject poverty to relative poverty, venerable western newspapers, Hollywood personalities, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, bishops and even multibillionaire financiers all lament some of its less desirable ramifications: unbearable inequality, brazen greed, climate change, and the hijacking of our parliamentary democracies by bankers and the ultra-rich.

None of this should surprise a reader of the manifesto. “Society as a whole,” it argues, “is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other.” As production is mechanised, and the profit margin of the machine-owners becomes our civilisation’s driving motive, society splits between non-working shareholders and non-owner wage-workers. As for the middle class, it is the dinosaur in the room, set for extinction.

At the same time, the ultra-rich become guilt-ridden and stressed as they watch everyone else’s lives sink into the precariousness of insecure wage-slavery. Marx and Engels foresaw that this supremely powerful minority would eventually prove “unfit to rule” over such polarised societies, because they would not be in a position to guarantee the wage-slaves a reliable existence. Barricaded in their gated communities, they find themselves consumed by anxiety and incapable of enjoying their riches. Some of them, those smart enough to realise their true long-term self-interest, recognise the welfare state as the best available insurance policy. But alas, explains the manifesto, as a social class, it will be in their nature to skimp on the insurance premium, and they will work tirelessly to avoid paying the requisite taxes.

Is this not what has transpired? The ultra-rich are an insecure, permanently disgruntled clique, constantly in and out of detox clinics, relentlessly seeking solace from psychics, shrinks and entrepreneurial gurus. Meanwhile, everyone else struggles to put food on the table, pay tuition fees, juggle one credit card for another or fight depression. We act as if our lives are carefree, claiming to like what we do and do what we like. Yet in reality, we cry ourselves to sleep.

Do-gooders, establishment politicians and recovering academic economists all respond to this predicament in the same way, issuing fiery condemnations of the symptoms (income inequality) while ignoring the causes (exploitation resulting from the unequal property rights over machines, land, resources). Is it any wonder we are at an impasse, wallowing in hopelessness that only serves the populists seeking to court the worst instincts of the masses?

With the rapid rise of advanced technology, we are brought closer to the moment when we must decide how to relate to each other in a rational, civilised manner. We can no longer hide behind the inevitability of work and the oppressive social norms it necessitates. The manifesto gives its 21st-century reader an opportunity to see through this mess and to recognise what needs to be done so that the majority can escape from discontent into new social arrangements in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”. Even though it contains no roadmap of how to get there, the manifesto remains a source of hope not to be dismissed.

If the manifesto holds the same power to excite, enthuse and shame us that it did in 1848, it is because the struggle between social classes is as old as time itself. Marx and Engels summed this up in 13 audacious words: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

From feudal aristocracies to industrialised empires, the engine of history has always been the conflict between constantly revolutionising technologies and prevailing class conventions. With each disruption of society’s technology, the conflict between us changes form. Old classes die out and eventually only two remain standing: the class that owns everything and the class that owns nothing – the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

This is the predicament in which we find ourselves today. While we owe capitalism for having reduced all class distinctions to the gulf between owners and non-owners, Marx and Engels want us to realise that capitalism is insufficiently evolved to survive the technologies it spawns. It is our duty to tear away at the old notion of privately owned means of production and force a metamorphosis, which must involve the social ownership of machinery, land and resources. Now, when new technologies are unleashed in societies bound by the primitive labour contract, wholesale misery follows. In the manifesto’s unforgettable words: “A society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

The sorcerer will always imagine that their apps, search engines, robots and genetically engineered seeds will bring wealth and happiness to all. But, once released into societies divided between wage labourers and owners, these technological marvels will push wages and prices to levels that create low profits for most businesses. It is only big tech, big pharma and the few corporations that command exceptionally large political and economic power over us that truly benefit. If we continue to subscribe to labour contracts between employer and employee, then private property rights will govern and drive capital to inhuman ends. Only by abolishing private ownership of the instruments of mass production and replacing it with a new type of common ownership that works in sync with new technologies, will we lessen inequality and find collective happiness.

According to Marx and Engels’ 13-word theory of history, the current stand-off between worker and owner has always been guaranteed. “Equally inevitable,” the manifesto states, is the bourgeoisie’s “fall and the victory of the proletariat”. So far, history has not fulfilled this prediction, but critics forget that the manifesto, like any worthy piece of propaganda, presents hope in the form of certainty. Just as Lord Nelson rallied his troops before the Battle of Trafalgar by announcing that England “expected” them to do their duty (even if he had grave doubts that they would), the manifesto bestows upon the proletariat the expectation that they will do their duty to themselves, inspiring them to unite and liberate one another from the bonds of wage-slavery.

Will they? On current form, it seems unlikely. But, then again, we had to wait for globalisation to appear in the 1990s before the manifesto’s estimation of capital’s potential could be fully vindicated. Might it not be that the new global, increasingly precarious proletariat needs more time before it can play the historic role the manifesto anticipated? While the jury is still out, Marx and Engels tell us that, if we fear the rhetoric of revolution, or try to distract ourselves from our duty to one another, we will find ourselves caught in a vertiginous spiral in which capital saturates and bleaches the human spirit. The only thing we can be certain of, according to the manifesto, is that unless capital is socialised we are in for dystopic developments.

On the topic of dystopia, the sceptical reader will perk up: what of the manifesto’s own complicity in legitimising authoritarian regimes and steeling the spirit of gulag guards? Instead of responding defensively, pointing out that no one blames Adam Smith for the excesses of Wall Street, or the New Testament for the Spanish Inquisition, we can speculate how the authors of the manifesto might have answered this charge. I believe that, with the benefit of hindsight, Marx and Engels would confess to an important error in their analysis: insufficient reflexivity. This is to say that they failed to give sufficient thought, and kept a judicious silence, over the impact their own analysis would have on the world they were analysing.

The manifesto told a powerful story in uncompromising language, intended to stir readers from their apathy. What Marx and Engels failed to foresee was that powerful, prescriptive texts have a tendency to procure disciples, believers – a priesthood, even – and that this faithful might use the power bestowed upon them by the manifesto to their own advantage. With it, they might abuse other comrades, build their own power base, gain positions of influence, bed impressionable students, take control of the politburo and imprison anyone who resists them.

Similarly, Marx and Engels failed to estimate the impact of their writing on capitalism itself. To the extent that the manifesto helped fashion the Soviet Union, its eastern European satellites, Castro’s Cuba, Tito’s Yugoslavia and several social democratic governments in the west, would these developments not cause a chain reaction that would frustrate the manifesto’s predictions and analysis? After the Russian revolution and then the second world war, the fear of communism forced capitalist regimes to embrace pension schemes, national health services, even the idea of making the rich pay for poor and petit bourgeois students to attend purpose-built liberal universities. Meanwhile, rabid hostility to the Soviet Union stirred up paranoia and created a climate of fear that proved particularly fertile for figures such as Joseph Stalin and Pol Pot.

I believe that Marx and Engels would have regretted not anticipating the manifesto’s impact on the communist parties it foreshadowed. They would be kicking themselves that they overlooked the kind of dialectic they loved to analyse: how workers’ states would become increasingly totalitarian in their response to capitalist state aggression, and how, in their response to the fear of communism, these capitalist states would grow increasingly civilised.

Blessed, of course, are the authors whose errors result from the power of their words. Even more blessed are those whose errors are self-correcting. In our present day, the workers’ states inspired by the manifesto are almost gone, and the communist parties disbanded or in disarray. Liberated from competition with regimes inspired by the manifesto, globalised capitalism is behaving as if it is determined to create a world best explained by the manifesto.

What makes the manifesto truly inspiring today is its recommendation for us in the here and now, in a world where our lives are being constantly shaped by what Marx described in his earlier Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts as “a universal energy which breaks every limit and every bond and posits itself as the only policy, the only universality, the only limit and the only bond”. From Uber drivers and finance ministers to banking executives and the wretchedly poor, we can all be excused for feeling overwhelmed by this “energy”. Capitalism’s reach is so pervasive it can sometimes seem impossible to imagine a world without it. It is only a small step from feelings of impotence to falling victim to the assertion there is no alternative. But, astonishingly (claims the manifesto), it is precisely when we are about to succumb to this idea that alternatives abound.

What we don’t need at this juncture are sermons on the injustice of it all, denunciations of rising inequality or vigils for our vanishing democratic sovereignty. Nor should we stomach desperate acts of regressive escapism: the cry to return to some pre-modern, pre-technological state where we can cling to the bosom of nationalism. What the manifesto promotes in moments of doubt and submission is a clear-headed, objective assessment of capitalism and its ills, seen through the cold, hard light of rationality.

The manifesto argues that the problem with capitalism is not that it produces too much technology, or that it is unfair. Capitalism’s problem is that it is irrational. Capital’s success at spreading its reach via accumulation for accumulation’s sake is causing human workers to work like machines for a pittance, while the robots are programmed to produce stuff that the workers can no longer afford and the robots do not need. Capital fails to make rational use of the brilliant machines it engenders, condemning whole generations to deprivation, a decrepit environment, underemployment and zero real leisure from the pursuit of employment and general survival. Even capitalists are turned into angst-ridden automatons. They live in permanent fear that unless they commodify their fellow humans, they will cease to be capitalists – joining the desolate ranks of the expanding precariat-proletariat.

If capitalism appears unjust it is because it enslaves everyone, rich and poor, wasting human and natural resources. The same “production line” that pumps out untold wealth also produces deep unhappiness and discontent on an industrial scale. So, our first task – according to the manifesto – is to recognise the tendency of this all-conquering “energy” to undermine itself.

When asked by journalists who or what is the greatest threat to capitalism today, I defy their expectations by answering: capital! Of course, this is an idea I have been plagiarising for decades from the manifesto. Given that it is neither possible nor desirable to annul capitalism’s “energy”, the trick is to help speed up capital’s development (so that it burns up like a meteor rushing through the atmosphere) while, on the other hand, resisting (through rational, collective action) its tendency to steamroller our human spirit. In short, the manifesto’s recommendation is that we push capital to its limits while limiting its consequences and preparing for its socialisation.

We need more robots, better solar panels, instant communication and sophisticated green transport networks. But equally, we need to organise politically to defend the weak, empower the many and prepare the ground for reversing the absurdities of capitalism. In practical terms, this means treating the idea that there is no alternative with the contempt it deserves while rejecting all calls for a “return” to a less modernised existence. There was nothing ethical about life under earlier forms of capitalism. TV shows that massively invest in calculated nostalgia, such as Downton Abbey, should make us glad to live when we do. At the same time, they might also encourage us to floor the accelerator of change.

The manifesto is one of those emotive texts that speak to each of us differently at different times, reflecting our own circumstances. Some years ago, I called myself an erratic, libertarian Marxist and I was roundly disparaged by non-Marxists and Marxists alike. Soon after, I found myself thrust into a political position of some prominence, during a period of intense conflict between the then Greek government and some of capitalism’s most powerful agents. Rereading the manifesto for the purposes of writing this introduction has been a little like inviting the ghosts of Marx and Engels to yell a mixture of censure and support in my ear.

Adults in the Room, my memoir of the time I served as Greece’s finance minister in 2015, tells the story of how the Greek spring was crushed via a combination of brute force (on the part of Greece’s creditors) and a divided front within my own government. It is as honest and accurate as I could make it. Seen from the perspective of the manifesto, however, the true historical agents were confined to cameo appearances or to the role of quasi-passive victims. “Where is the proletariat in your story?” I can almost hear Marx and Engels screaming at me now. “Should they not be the ones confronting capitalism’s most powerful, with you supporting from the sidelines?”

Thankfully, rereading the manifesto has offered some solace too, endorsing my view of it as a liberal text – a libertarian one, even. Where the manifesto lambasts bourgeois-liberal virtues, it does so because of its dedication and even love for them. Liberty happiness, autonomy, individuality, spirituality, self-guided development are ideals that Marx and Engels valued above everything else. If they are angry with the bourgeoisie, it is because the bourgeoisie seeks to deny the majority any opportunity to be free. Given Marx and Engels’ adherence to Hegel’s fantastic idea that no one is free as long as one person is in chains, their quarrel with the bourgeoisie is that they sacrifice everybody’s freedom and individuality on capitalism’s altar of accumulation.

Although Marx and Engels were not anarchists, they loathed the state and its potential to be manipulated by one class to suppress another. At best, they saw it as a necessary evil that would live on in the good, post-capitalist future coordinating a classless society. If this reading of the manifesto holds water, the only way of being a communist is to be a libertarian one. Heeding the manifesto’s call to “Unite!” is in fact inconsistent with becoming card-carrying Stalinists or with seeking to remake the world in the image of now-defunct communist regimes.

When everything is said and done, then, what is the bottom line of the manifesto? And why should anyone, especially young people today, care about history, politics and the like?

Marx and Engels based their manifesto on a touchingly simple answer: authentic human happiness and the genuine freedom that must accompany it. For them, these are the only things that truly matter. Their manifesto does not rely on strict Germanic invocations of duty, or appeals to historic responsibilities to inspire us to act. It does not moralise, or point its finger. Marx and Engels attempted to overcome the fixations of German moral philosophy and capitalist profit motives, with a rational, yet rousing appeal to the very basics of our shared human nature.

Key to their analysis is the ever-expanding chasm between those who produce and those who own the instruments of production. The problematic nexus of capital and waged labour stops us from enjoying our work and our artefacts, and turns employers and workers, rich and poor, into mindless, quivering pawns who are being quick-marched towards a pointless existence by forces beyond our control.

But why do we need politics to deal with this? Isn’t politics stultifying, especially socialist politics, which Oscar Wilde once claimed “takes up too many evenings”? Marx and Engels’ answer is: because we cannot end this idiocy individually; because no market can ever emerge that will produce an antidote to this stupidity. Collective, democratic political action is our only chance for freedom and enjoyment. And for this, the long nights seem a small price to pay.

Humanity may succeed in securing social arrangements that allow for “the free development of each” as the “condition for the free development of all”. But, then again, we may end up in the “common ruin” of nuclear war, environmental disaster or agonising discontent. In our present moment, there are no guarantees. We can turn to the manifesto for inspiration, wisdom and energy but, in the end, what prevails is up to us.

Adapted from Yanis Varoufakis’s introduction to The Communist Manifesto, published by Vintage Classics on 26 April

For The Guardian’s site, click here

Turn the Brexit page and let’s move on by uniting progressives in the UK and in the EU: Interview in BIG ISSUE NORTH, 22 APR 2018

“It’s time to turn the page, to accept that it’s happening,” Varoufakis told Big Issue North. “It’s happening in a disastrous way but Theresa May is going to be allowed to see it through because the Cabinet does not want to fell her until she delivers something that they can then shoot her over.

“So there won’t be a general election, there won’t be a referendum, there won’t be a parliamentary debate over it.”

“In but against” EU

Varoufakis negotiated the most recent EU bailout for Greece but resigned from the government because he believed his one-time ally and prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, climbed down in the face of demands by the troika of financial institutions that the government impose even more austerity on its people.

He is a co-founder of the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025, or DiEM25, a progressive movement seeking to reform the EU by being “in but against”, and has recently launched a new political party in Greece that will stand in elections promising to end the country’s “debt bondage”.

As one example of a policy DiEM25 would support, Varoufakis suggested co-operation between European state investment banks on a massive green new deal that would boost renewable energy supplies and bring many new well paid jobs.

He said investment in Europe was at a 60-year low even though rich individuals and corporations were sitting on more wealth than ever before.

“Lift all boats”

“How could we emulate a democratic European union when there is none?” he said. “Jeremy Corbyn is talking about creating an investment bank along the lines of the Post Office savings bank – which used to be an investment bank. Let’s say he does. It won’t be enough because there won’t be enough investment capital in it.

“But we have the European Investment Bank in Europe. There is a German one, there is a French one, there is a Swedish one.

“Imagine if you had a press conference – no need for treaties, European Union institutions, anything like that – just a press conference. The heads of all these investment banks announce that they will collaborate and borrow from the private sector – issue bonds – £600-£700 billion every year for the whole of Europe. Now that’s a fantastic sum to invest across Europe. It would lift all boats.”

He said a co-ordinated promise by the heads of Europe’s central banks, including the Bank of England, to buy those bonds if others would not would support their value, giving private investors the confidence to buy them.

“Suddenly you have a huge green new deal for the whole of Europe,” said Varoufakis, speaking before a speech to Sheffield’s Festival of Debate. “So who gives a damn if Britain is in the EU?

“These are the things that we at DiEM25 are talking about. These are the things that can bring people together. What progressive in their right mind could ever object to this, whether they are Remainers, Leavers, half way house, whatever?”

Varoufakis also warned that those who believe the UK can stay in the EU single market but still end free movement of people were mistaken. “That’s nonsense,” he said. “I gave a speech to Labour MPs in the House of Commons a few weeks ago advocating a Norway-plus solution, which would maintain free movement of people.

“I am a strong believer in freedom of movement, not just in Europe but everywhere. It’s just a joke to be saying to the rest of the world that we are going to be stopping people at the border. It’s preposterous.”

But it is not only Brexiters who are proposing putting up barriers. Among EU members, Hungary’s leader Viktor Orban has just won another term by amplifying his anti-immigrant stance, while an government assault on the freedom of the judiciary in Poland has brought fears that the EU’s liberal values are under threat, particularly in former Soviet bloc countries.

The European Commission has threatened disciplinary action against Poland but its scope to act is limited. How would DiEM25 approach the problem?

“Iron-clad, manic might”

“In our manifesto, which was written well before Orban became such a menace we were very clear – we believe in an open Europe, we believe in a social Europe and we believe in a humanist Europe, so anyone who manages to speak to the fears of the populace, securing a mandate on the basis that we hate foreigners and we are going to keep them out at our borders while at the same time demanding we are in the European Union, should be confronted,” Varoufakis replied.

He said the contrast was “astonishing” between how the EU, “in all its iron-clad, manic might”, came down on the Greek government for resisting its demand to cut pensions for the poorest and its treatment of Hungary and Poland.

“Look what’s happening in Spain too with the Catalonians. Whether or not you are in favour of independence – the fact is that there are politicians in jail in Europe and Brussels is whistling in the wind and pretending this is not anything to do with the European Union.”

As well as support for migrants and refugees and a revitalisation of the European economy, DiEM25 is calling for transparency in the EU decision making process, where the roles and responsibilities of the main institutions remains unclear not only to millions of citizens but those who deal with them directly – like Varoufakis.

He said the outcome of the Greek negotiations he was involved with would have been “very different” if, for example, EU meetings were held in public.

“The way they divided and ruled over us was through opacity. I was saying one thing in the Eurogroup and they were reporting another. So imagine if these Eurogroup meetings were live-streamed – the whole thing would have collapsed…

“If there was transparency they would not have even been able to convince their own people. This character assassination plot – it was a plot – to portray our government as unreasonable rule breakers would simply have vanished.”

The political maze was laid out in Varoufakis’s 2017 book Adults in the Room, in which he also recounts a sinister call he received in 2011, before he was a minister but when he was helping journalists investigate banking scandals. The unnamed caller said Varoufakis’s son might not be safe if he continued with his efforts.

Varoufakis recalled his bewilderment at the way the troika conducted its business. “There was fragmentation both horizontal and vertical. There was fragmentation between the institutions. They actually hated each other. The IMF was so critical and dismissive of the Commission – and of the European Central Bank, less so but also – and at the same time the ECB didn’t give a damn about the Commission.

“That was the horizontal fragmentation but there was a vertical fragmentation too. The head of the Commission or the Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs would think one thing and his deputy would think something completely different, and you had no idea what to do or who to speak to.

“What was fascinating was that it was the little people, the lower ranks who had more authority, as usual. If you watch Yes Minister you’d know what I mean.”

Photo: Chris Sanders. For more information about the Festival of Debate see festivalofdebate.com

Interview by Kevin Gopal. Click here for the BIG ISSUE NORTH site.

Liberal Totalitarianism – Project Syndicate op-ed, 30 APR 2018

LISBON – It used to be an axiom of liberalism that freedom meant inalienable self-ownership. You were your own property. You could lease yourself to an employer for a limited period, and for a mutually agreed price, but your property rights over yourself could not be bought or sold. Over the past two centuries, this liberal individualist perspective legitimized capitalism as a “natural” system populated by free agents.

LISBON – It used to be an axiom of liberalism that freedom meant inalienable self-ownership. You were your own property. You could lease yourself to an employer for a limited period, and for a mutually agreed price, but your property rights over yourself could not be bought or sold. Over the past two centuries, this liberal individualist perspective legitimized capitalism as a “natural” system populated by free agents.A capacity to fence off a part of one’s life, and to remain sovereign and self-driven within those boundaries, was paramount to the liberal conception of the free agent and his or her relationship with the public sphere. To exercise freedom, individuals needed a safe haven within which to develop as genuine persons before relating – and transacting – with others. Once constituted, our personhood was to be enhanced by commerce and industry – networks of collaboration across our personal havens, constructed and revised to satisfy our material and spiritual needs… Click here to read the rest of the article.

April 30, 2018

May 1st: As long as capitalism exists, every generation of workers is condemned to wage the same struggles again and again – for dignity, wages, conditions, hours

The 1st of May commemoration is not an exercise in remembrance alone: Today’s generation is struggling against the same monsters that crushed the workers in May 1886 in Chicago – and for the same reason: The struggle to limit working hours to 8 per day, to extract from employers a living wage, to secure decent conditions, to safeguard the workers’ dignity in an era where young people are forced to choose between Uberisation, endless internships, or a soul-destroying process of branding and re-branding themselves as ultra-flexible, all-hours wage slaves who live for the corporation and not for themselves.

The struggle continues. And this is, in itself, excellent news!

ΠΡΩΤΟΜΑΓΙΑ: Όσο υπάρχει καπιταλισμός, κάθε γενιά εργαζόμενων είναι καταδικασμένη να δίνει ξανά και ξανά τους ίδιους αγώνες

Τον Μάη 1886 στο Σικάγο

Την μεγάλη απεργία του 1896 στο Λαύριο

Tην Φεντερασιόν του Αβραάμ Μπεναρόγια και τους νεκρούς της Πρωτομαγιάς του 1911 στην Θεσσαλονίκη

Τον Κρητικό συνδικαλιστή Λούη Τίκα, που έπεσε στο Κολοράντο το 1914 στην σφαγή απεργών στα ορυχεία του Ροκφέλερ

Τους νεκρούς απεργούς των ορυχείων της Μήλου…

Τα δικά μας Μνημόνια που δεν είναι παρά σκληρός ταξικός πόλεμος εναντίον των εργαζόμενων – μια πρόβα τζενεράλε μισανθρωπικών πολιτικών που δοκιμάζονται στο δυστιπικό εργαστήρι της Χρεοδουλοπαροικίας “Η Ελλάς” προτού εφαρμοστούν στην υπόλοιπη Ευρώπη.

Σήμερα, 1η Μάη, θυμόμαστε ότι η μισθωτή εργασία βρίσκεται υπό διωγμό παντού. Και ότι όσο το εργατικό κίνημα είναι αδύναμο, η ανθρωπότητα φθίνει οικονομικά, κοινωνικά, ηθικά.

April 23, 2018

Η αργόσυρτη δολοφονία της πρότασης Μακρόν επιβεβαιώνει την ανάγκη για υπεύθυνη ανυπακοή – ΕφΣυν 21 ΑΠΡ 2018

[Για την ιστοσελίδα της ΕφΣυν πατήστε εδώ.]

Αμέσως μετά την εκλογή του, ο Εμανουέλ Μακρόν κατέθεσε συγκεκριμένη πρόταση για τη σταθεροποίηση της ευρωζώνης. Ο ίδιος τη χαρακτήρισε μινιμαλιστική: το ελάχιστο δηλαδή που πρέπει να γίνει για να μπορέσει το ευρώ να πάψει να λειτουργεί ως μόνιμη πηγή υφεσιακών και αποδομητικών δυνάμεων.

Σε κατ’ ιδίαν συζήτηση μάλιστα, είχε δηλώσει ευθαρσώς ότι θεωρούσε την υλοποίηση της πρότασής του προαπαιτούμενο για να μπορέσει η Γαλλία να αναπνεύσει εντός της ευρωζώνης.

Τον τελευταίο χρόνο, το γερμανικό κατεστημένο καταφέρει τη μία μαχαιριά μετά την άλλη στο σώμα της πρότασης Μακρόν. Σήμερα, μετά τις τελευταίες δηλώσεις του Βερολίνου, το μετριοπαθές σχέδιο του Μακρόν για την ευρωζώνη κείται πλέον νεκρό, αν και ακόμα άταφο.

Μαζί του, αιμόφυρτη στο πάτωμα των διαδρόμων και αιθουσών όπου λαμβάνονται οι σημαντικές αποφάσεις, κείται και η τελευταία ευκαιρία του ευρωπαϊκού κατεστημένου να καταστήσει την ευρωζώνη βιώσιμη και να ξαναδώσει πνοή στην παραπαίουσα Ευρωπαϊκή Ενωση.

Η πρόταση Μακρόν για την ευρωζώνη

Η πρόταση του νέου Γάλλου προέδρου περιείχε τέσσερα βασικά σημεία.

1. Δημιουργία κοινού προϋπολογισμού της ευρωζώνης, που χρηματοδοτείται όχι από τα κράτη-μέλη αλλά από νέους «ομοσπονδιακούς» φόρους, καθώς και από δάνεια που επιβαρύνουν όχι τα κράτη-μέλη αλλά το σύνολο της ευρωζώνης. Επιγραμματικά: ομοσπονδοποίηση της δημοσιονομικής πολιτικής.

2. Πραγματική τραπεζική ενοποίηση έτσι ώστε όταν μια τράπεζα καταρρέει και χρειάζεται χρήματα (τη λεγόμενη, κατ’ ευφημισμόν, «ανακεφαλαιοποίηση»), αυτή η διαδικασία να μην επιβαρύνει τους πολίτες της χώρας στην οποία έχει τα κεντρικά της γραφεία η εν λόγω τράπεζα, αλλά να δίνεται μια λύση ευρωπαϊκή. Κι αν η τράπεζα πρέπει να κλείσει, οι εγγυημένες καταθέσεις των καταθετών να επιβαρύνουν συνολικά την ευρωζώνη, είτε μέσα από τον ESM σε συνδυασμό με την ΕΚΤ, είτε από τον κοινό προϋπολογισμό.

3. Κοινό ταμείο ανεργίας, έτσι ώστε μια μεγάλη ύφεση σαν αυτή της τελευταίας δεκαετίας να μη φέρνει σε ασφυξία τα κράτη με τη μεγαλύτερη ανεργία και να αναγκάζονται οι χώρες με τη μεγαλύτερη ανάγκη δημόσιων επενδύσεων να προβαίνουν στον εκμηδενισμό των δημόσιων επενδύσεων.

4. Κοινό επενδυτικό ταμείο, το οποίο να στρέφει επενδυτικές ροές στις πιο βαριά χτυπημένες από μια κρίση χώρες, με στόχο την εξισορρόπηση σε όλη την επικράτεια της ευρωζώνης.

Καμία από αυτές τις προτάσεις δεν ήταν καινοτόμες. Για την ακρίβεια, είναι οι αυτονόητες μεταρρυθμίσεις χωρίς τις οποίες η ευρωζώνη θα παραμένει ένα σιδερένιο κλουβί λιτότητας για τη μεγάλη πλειονότητα των πολιτών της, και μάλιστα ασταθές και επιρρεπές στη διάλυση. Αυτό που όμως ήταν καινούργιο ήταν πως για πρώτη φορά τέτοιες προτάσεις κατετίθεντο από τον πρόεδρο της Γαλλίας και, μάλιστα, σε μια συγκυρία ιδιαίτερα δύσκολη για τη Γερμανίδα καγκελάριο, η οποία σε τελική ανάλυση χρωστούσε την πολιτική της επιβίωση στην εκλογική νίκη του Μακρόν επί της Λεπέν. (Αμφισβητεί κανείς ότι, εάν είχε νικήσει η Μαρίν Λεπέν, η κ. Μέρκελ θα βρισκόταν στο σπίτι της σήμερα;)

Το σχέδιο του Μακρόν ήταν απλό: Θα «γερμανοποιούσε» τη γαλλική αγορά εργασίας, θα εφάρμοζε λιτότητα όσο χρειαζόταν για να ρίξει το έλλειμμα του γαλλικού προϋπολογισμού (για πρώτη φορά) κάτω από το κατά Μάαστριχτ «νόμιμο» όριο και, κατόπιν, θα πήγαινε στο Βερολίνο με το εξής επιχείρημα: «Εκανα αυτό που ζητούσατε χρόνια τώρα. Γερμανοποίησα τη γαλλική μισθωτή εργασία και τον γαλλικό κρατικό προϋπολογισμό. Σειρά σου τώρα, Ανγκελα, να συμφωνήσεις με την πρότασή μου σταθεροποίησης και ολοκλήρωσης της νομισματικής μας ένωσης».

Από την επόμενη κιόλας μέρα της εκλογής του Μακρόν (π.χ. βλ. 13/5/2017, «Εφημερίδα των Συντακτών»), προέβλεπα ότι «…το Βερολίνο δεν θα του δώσει τίποτα. Και τι θα κάνει τότε; Χωρίς τη διάθεση να ασκήσει βέτο στην Ε.Ε. και στο Eurogroup, τα ωραία του σχέδια για την ευρωζώνη θα ξεχαστούν, όπως του Ολάντ προηγουμένως, και το μόνο που θα μείνει είναι ο θυμός και η απόγνωση που τρέφουν η λιτότητα, η μείωση των φόρων για τους πλούσιους και η απορρύθμιση της μισθωτής εργασίας». Δυστυχώς αυτό ακριβώς συνέβη.

Η δολοφονία των πολλών, μικρών μαχαιριών

Το Βερολίνο ποτέ δεν είπε, μια κι έξω, όχι στην πρόταση του Μακρόν. Απλά, από την πρώτη μέρα άρχισε να την τραυματίζει με πολλές μαχαιριές, κάποιες πολύ μικρές, άλλες μεγαλύτερες. Η αρχή έγινε, βεβαίως, από τον Βόλφγκανγκ Σόιμπλε, ο οποίος απέρριψε την ιδέα ενός κοινού προϋπολογισμού με κοινό χρέος και κοινούς φόρους. Η Ανγκελα Μέρκελ είπε ότι συζητά τον κοινό προϋπολογισμό, αλλά όχι και το κοινό χρέος.

Μερικές μέρες αργότερα, επέστρεψε ο Σόιμπλε με μια πρόταση που φαινόταν συμβιβαστική ενώ, στην πραγματικότητα, ήταν το άκρον άωτον την επιθετικότητας απέναντι στον Μακρόν: Πρότεινε να επιτρέπεται ένα ποσό από τη χρηματοδοτική ικανότητα του ESM (σημ. ο ESM χορήγησε τα δάνεια του 3ου μας Μνημονίου) να χορηγείται σε χώρες της ευρωζώνης για επενδυτικούς σκοπούς κι όχι απλά για μνημονιακές διασώσεις.

Πολλοί αναθάρρησαν επειδή δεν κατάλαβαν τι είχε κατά του ο Σόιμπλε: την εδραίωση της τρόικας στο… Παρίσι (που, όπως μου είχε εξομολογηθεί δύο φορές, ήταν ο διακαής του πόθος).

Οποιος έχει διαβάσει το καταστατικό του ESM, καταλαβαίνει το γιατί: για να λάβει κράτος-μέλος έστω και ένα ευρώ από τον ESM, χρειάζεται Μνημόνιο και επιτήρηση. Το μήνυμα του Σόιμπλε στον Μακρόν ήταν απλό: Αν η Γαλλία ήθελε επενδυτικά κονδύλια από την ευρωζώνη, το Παρίσι θα πρέπει να ζει αγκαλιά με την τρόικα.

Από τότε, ο Σόιμπλε μπορεί να έφυγε από το ομοσπονδιακό υπουργείο Οικονομικών, όμως οι διάδοχοί του, τόσο ο χριστιανοδημοκράτης Αλτμαγιερ όσο και ο «σοσιαλδημοκράτης» Σολτς, συνεχίζουν να ρίχνουν τη μία μαχαιριά μετά την άλλη στο σώμα της πρότασης Μακρόν: Ξεκαθάρισαν ότι δεν υπάρχει πιθανότητα να προχωρήσει η τραπεζική ενοποίηση αν πρώτα δεν εξαφανιστούν τα «κόκκινα» δάνεια από την περιφέρεια (κάτι που είναι αδύνατον). Απέρριψαν την ιδέα ενός κοινού ταμείου ανεργίας. Απαγόρευσαν στο Eurogroup ακόμα και τη συζήτηση για κοινό προϋπολογισμό και κοινό χρέος.

Μήνυσαν στην Κομισιόν ότι ο ESM δεν πρόκειται ποτέ να περάσει στη δικαιοδοσία της, ούτε και να ενταχθεί στο κοινοτικό δίκαιο. Και το πιο βάναυσο και τελειωτικό χτύπημα: Ανακοίνωσαν ότι ο ESM, ακόμα κι εάν μετονομαστεί σε Ευρωπαϊκό Νομισματικό Ταμείο, θα παραμείνει εξαρτημένος από το ΔΝΤ, τον οποίο θα επικουρεί σε μελλοντικές «διασώσεις».

Κι εμείς;

Το αφήγημα του ελληνικού κατεστημένου ήταν και παραμένει ότι εμείς δεν έχουμε εναλλακτική από το να παίζουμε τον ρόλο των «υποδειγματικών κρατούμενων», περιμένοντας τους Βορειοευρωπαίους να προχωρήσουν σε λύσεις τύπου Μακρόν οι οποίες, κάποια στιγμή, θα μας δώσουν το πολυπόθητο εξιτήριο από τη δίνη του μη βιώσιμου χρέους και της αυτοτροφοδοτούμενης λιτότητας.

Το 2011 μας το έλεγαν αυτό οι κ. Παπανδρέου-Παπακωνσταντίνου. Το 2014, παρόμοιο τροπάρι ακούγαμε από τους κ. Σαμαρά-Βενιζέλο. Το 2018, η ίδια ιστορία από τους κ. Τσίπρα-Δραγασάκη:

Λίγη υπομονή ακόμα κι η Ευρώπη, ελέω Μέρκελ και με τη βοήθεια κάποιου Μακρόν, θα κάνει το μεγάλο βήμα προς την ομοσπονδία. Θα είναι έγκλημα να είμαστε εμείς απ’ έξω όταν θα γίνει αυτό το πολυπόθητο βήμα!

Τα ψέματα όμως τελείωσαν. Η δολοφονία της μετριοπαθούς πρότασης Μακρόν ήταν η τελευταία ευκαιρία μιας συστημικής μεταρρύθμισης του συστήματος. Αυτή η ευρωζώνη δεν θα μεταρρυθμιστεί μέσα από συναινετικές διαδικασίες. Τελεία και παύλα. Αυτός είναι ο λόγος που το ΜέΡΑ25 καταθέτει μια ψύχραιμη και ουσιαστική πρόταση: Ο μόνος τρόπος να είμαστε υπεύθυνοι σήμερα είναι μέσα από άμεση, ήρεμη αλλά αποφασιστική ρήξη με το Eurogroup και την ευρωζώνη.

Χωρίς φανφάρες, μεγαλοστομίες ή ρητορείες, να νομοθετηθούν οι επτά βασικές τομές που είναι προαπαιτούμενα για να αναπνεύσει η ελληνική κοινωνία είτε είμαστε στο ευρώ είτε όχι.

Απόψε, στο θέατρο Ιλίσια, το ΜέΡΑ25 οργανώνει συζήτηση μεταξύ των ανθρώπων του θεάτρου για τον πολιτισμό

Κρίση πολιτικής και πολιτισμού στην Ελλάδα με έμφαση στην τελευταία οκταετία. Διαπιστώσεις και προβληματισμοί για την τρέχουσα κατάσταση και οι προοπτικές για μια χώρα που βίωσε και βιώνει την πολυδιάστατη κρίση όλο και βαθύτερα.

Δευτέρα 23/4, 7:00 μ.μ., θέατρο Ιλίσια, Παπαδιαμαντοπούλου 4, σταθμός μετρό Μέγαρο Μουσικής

April 22, 2018

Jeremy Hardy nails it on the Syrian bombings and the preposterous excuse that “We had no alternative but to bomb” – from this week’s ‘News Quiz’, BBC Radio 4

For the complete program click here.

April 20, 2018

Addressing Sheffield’s Festival of Ideas: DiEM25 is here to help heal the rift between progressive Remainers and progressive Leavers – audio, 18 APR 2018

Ladies and gentlemen, the main reason for being here tonight is to use, in our capacity as the Democracy in Europe Movement – DiEM25 -, to press whatever resources we have into the service of healing the rift between progressive Remainers and progressive Leavers. We have enough divisions in the UK, we have enough divisions in the EU, we do not need another one along the lines of Brexit. Yes, we at DiEM25 campaigned, along with Jeremy Corbyn, John McDonnell, Caroline Lucas and others for a radical remain. But I am not here, tonight, as a Remainer. I am here tonight to propose ways so that, post-Brexit, British and Continental European progressives can come closer together than we have ever been to build a decent Europe.

Related article in The Guardian: Our new European party can unite Britain’s feuding Remainers and Leavers

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2452 followers