Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 100

July 17, 2018

AUSTERITY (in 144 pages)- A Vintage mini

Read more here

Why Germany neither can nor should pay more to save the eurozone – IFO Munich Seminar, 11 June 2018

“I wanted a Germany that was hegemonic and efficient, not authoritarian and caught up in a European Ponzi scheme. That was in 2013.” Excerpt from the Munich Seminar.

This CESifo group Munich seminar took place on June 11, 2018 in Ludwig-Maximilian University, in Munich, in the Grosse Aula of the Ludwig-Maximilian University. The euro crisis has highlighted the urgent need for reform in the Eurozone. However, approaches to a solution can be divided into two camps. The disagreement, primarily between France and Germany, is reflected very clearly in their different attitudes towards fiscal union. While the French strongly support a fiscal union, which necessarily implies fiscal transfers by Germany and other donor countries, Germany absolutely rejects a fiscal union and favours a post-crisis write-off of bad loans instead. In his speech Yanis Varoufakis argues that both visions are flawed and potentially dangerous, going on to differentiate between the solution to the Eurozone’s structural problems and the zeal and ambitions of its political class.

Partial transcript of the speech below:

In these trying times for Europe, our common home, opportunities like tonight’s to discuss honestly and frankly Europe’s crisis are priceless.

When the title of my talk was announced, many of my critics were puzzled. Having portrayed me as a Greek politician who, back in 2015, came to Germany cap-in-hand demanding more money, they had difficulty explaining why I would be standing in front of you to argue that Germany neither can nor should pay more to save the eurozone.

The puzzle of course disappears after a close look at what I was saying since 2010. Let me give you an example. On July 24, 2013 I published an article in Handelsblatt entitled ‘Europe needs a hegemonic Germany’. In that article I had, again, surprised many by arguing in favour of a strong Germany as the best way of leading Europe out of its difficulties. My criticism of the German government, and its attitudes towards the eurozone more broadly and Greece more specifically, was not that Berlin was not paying enough but that, in a sense, it was paying too much – except that it was wasting the German people’s money in perpetuating what I termed a gigantic exercise in fraudulent bankruptcy concealment.Germany was paying too much… in perpetuating a gigantic exercise at fraudulent bankruptcy concealment.

I added that Europe needs a robust Germany, an energised Germany, to lead the way, to use its money wisely – in other words to be genuinely hegemonic, as opposed to spending too many resources on concealing impossible bankruptcies. Indeed, back then, in 2013, I had warned that continuing to insist on hiding serial bankruptcies would cost all of us more and more and would require increasing degrees of authoritarianism to perpetuate and reproduce the policies of denial.

In short, I wanted a Germany that was hegemonic and efficient, not authoritarian and caught up in a European Ponzi scheme. That was in 2013. Two years later, in March 2015, I wrote an article, while Greece’s finance minister, referring to the first and second bailout loans, of 2010 and 2012. Allow me to quote from it:

“The fact is that Greece had no right to borrow from German – or any other European – taxpayers at a time when its public debt was unsustainable. Before Greece took on any loans, it should have initiated debt restructuring and undergone a partial default on debt owed to its private-sector creditors.

But this “radical” argument was largely ignored at the time. Similarly, European citizens should have demanded that their governments refuse even to consider transferring private losses to them. But they failed to do so, and the transfer was effected soon after. The result was the largest taxpayer-backed loan in history, provided on the condition that Greece pursue such strict austerity that its citizens have lost one-quarter of their incomes, making it impossible to repay private or public debts.

The ensueing – and ongoing – humanitarian crisis has been tragic… Animosity among Europeans is at an all-time high, with Greeks and Germans, in particular, having descended to the point of moral grandstanding, mutual finger-pointing, and open antagonism. This toxic blame game benefits only Europe’s enemies.”

A personal note here, if you permit it: For me, nothing hurt more than my unfair portrayal as an anti-Europeanist Greek politician demanding more money from Germany, or arguing that Germany must pay more for Greece and for Europe. In fact the reason I resigned the ministry is simple: I was refusing to sign the third bailout, to take more of your money, because I was convinced that, when you are bankrupt you have no right to borrow more. What should we have done? Declare bankruptcy, suffer the pain together with the lenders that should not have lent to the previous governments, reform the country and move on. What happened instead?

Italy and Greece

A few weeks after my resignation, Mrs Merkel, Mr Tsipras and others agreed on another 85 billion euros loan to the Greek state. On that day I rose in Greece’s Parliament to denounce this as another extend-and-pretend loan – another mountain of money given to the bankrupt Greek state in order to pretend for a few more years that it is repaying its debts – and granted under conditions that guarantee that the Greek economy and our society would continue to shrink, that the debt would not be repaid, and that Europe would move on to repeat the same mistakes in Italy – a country whose public debts and banking losses are just too large for Germany and other countries to sustain via Greek-like bailout loans.

That is what I said in the summer of 2015. Today, I painfully observe the realisation of those fears. Italy has fallen to the forces of xenophobia and Europhobia that welcome the European Union’s breakup. How did that happen? It happened because the failed policies first tried on Greece were also implemented in Italy.

Just like Greece, Italy had been ruled for decades by a corrupt oligarchy enriching itself from EU transfers and relying on a kind of ‘establishment-populism ’ that traded on the impossible promise that everyone would become better off as long everyone pretended to adhere to the EU, Maastricht & Fiscal Compact rules – rules that could not be adhered to even if the government wanted to.

When this promise was proven false, and the doom loop of bankrupt state and zombie banks caused per capita income to shrink and prospects for most Italians to wither, the electorate voted for a new government representing two opposing anti-establishment populisms (that of the xenophobic Lega and of the Five Star movement). The crucial difference, ladies and gentlemen, between this Italian government and the Greek one I served in is that we were committed Europeanists – we did not want to leave the euro even though we had, realistically, to consider a Grexit – especially when constantly threatened with it by the creditors. The main movers behind the new Italian government, however dream of being threatened with Italexit, a fact that guarantees a clash of gigantic enormity with Berlin, Brussels and Frankfurt.

A badly designed monetary union

These developments, ladies and gentlemen, are not the result of bad choices, of human frailty. They are the result of a badly designed monetary union. Germany is simply not rich enough to support this faulty architecture. The EU cannot, backed by Germany, extend and pretend Italy’s 2.6 trillion debt, as well as the losses of their zombie banks. At the very same time, Italy will continue to stagnate within this faulty architecture until some political event will cause its uncontrolled, very costly breakdown. It is the fate of an unsustainable system not to be sustained. The longer it is sustained by political stealth and authoritarianism, the more catastrophic its collapse will be, when it comes.

What should we do?

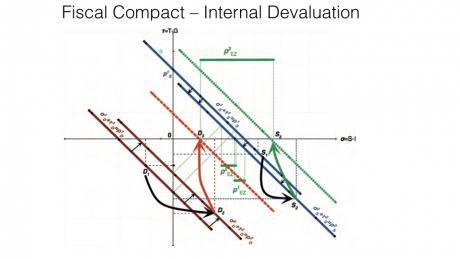

So, what should we do? What should Germany do? Some argue that we need the German treasury, and the treasuries of other surplus countries, to support the treasuries of the deficit countries. This is both infeasible and undesirable. Infeasible because the fiscal surpluses of the Germanies are dwarfed by the banking losses and debts of the Greeces and the Italies. Then there are those who propose the liquidationist approach – let public debt default if it must. While I sympathise with the logic, and I wish we had followed that approach with Greece’s public debt, liquidationism is inconsistent with the euro architecture: following such government bond automatic restructuring, our weak banks that rely on these bonds for collateral and repo operations will go under, demanding of the weakened states to refinance them – which defeats the purpose of liquidating part of their debt.

Back to square one then: What should we do? I shall be arguing that:

The current rules cannot be applied, even if we were all desperate to apply them

Those who seek a fiscal union with the German federal government footing the bill of other governments are wrong: the German government cannot afford to finance the eurozone’s necessary reforms and, indeed, it should not have to

Those who propose the liquidationist route – e.g. that the ESM extends loans to states at the price of restructuring of their debt – are also wrong, because they do not take into consideration the doom loop binding together the insolvency of our states with the insolvency of our banks (e.g. Italy’s)

Proposing a new Treaty as a solution to the eurozone’s immediate problems only deepens the sense of pessimism in the heart of those who, correctly, estimate that the current political climate makes New Treaties impossible

In this eventuality, there are two courses of action that we must consider: One is the controlled dismantling of the current eurozone. The other is a simulation of a federation using existing institutions and new policies based on a re-interpretation of the letter of the charters and treaties.

So, let me begin by explaining why the current rules cannot work within our asymmetrical monetary union (MU). Sure, the Maastricht rules and the ECB charter could have worked fine in a symmetrical MU, as long as governments wanted/were forced to stick to the rules: a symmetrical MU is one in which countries differ on productivity and endowments but every market in every country comprises exclusively pricetaking firms, customers and workers (in other words, no one has the capacity to influence prices). In such a symmetrical, perfectively competitive union trade surpluses and deficits, as well as different productivity growth paths, are auto-corrected through a process of devaluation in the country whose productivity growth lags behind and of internal revaluation in the ‘stronger’ country. Whether this devaluation is external or internal makes no difference. Whether we have the euro or separate currencies does not matter, except perhaps that under the euro we would have enjoyed lower transaction costs.

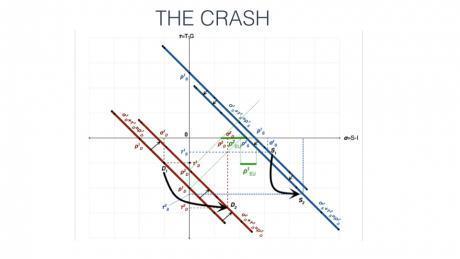

However, things are very different in an asymmetrical MU. In a positively asymmetrical MU like our eurozone, financial markets are bound to destabilise our economy and cause a crisis that makes impossible the implementation of our rules.

What exactly is an asymmetrical MU? It is a monetary union between:

1. National economies that comprise large oligopolistic manufacturing sectors, replete with economies of scale (as well as of economies of networks and of scope), with production units operating at excess capacity (that reflects their market power and their capacity to deter competitors), and concentrating much economic activity on the production of capital goods; and

2. National economies where the capital goods sector is atrophic, where production is much less capital intensive, and where economic rents are not due to economies of scale but due to corrupt practices and socio-political impediments to competition (e.g. restrictive practices, crony relations between authorities and particular business interests).

When one nation, or region, is more industrialised than another; when it produces most of the high value added tradable goods while the other concentrates on low yield, low value-added non-tradables; the asymmetry is entrenched. Think not just Greece in relation to Germany. Think also East Germany in relation to West Germany, Missouri in relation to neighbouring Texas, North England in relation to the Greater London area – all cases of trade imbalances with impressive staying power.

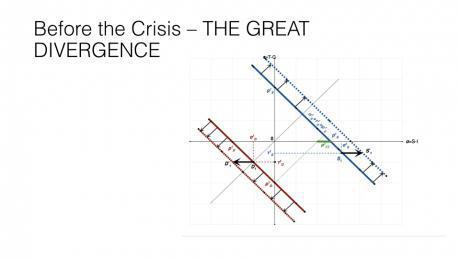

A freely moving exchange rate, as that between Japan and Brazil, helps keep the imbalances in check, at the expense of volatility. But when we fix the exchange rate or, even more ambitiously, introduce a common currency, something else happens: banks begin to magnify the surpluses and the deficits.

They inflate the imbalances and make them more dangerous. Automatically. Without asking voters or Parliaments. Without even the government of the land taking notice. It is what I refer to as toxic debt and surplus recycling. By the banks.

It is easy to see how this happens: A German trade surplus over Greece generates a transfer of euros from Greece to Germany. By definition! This is precisely what was happening during the good ol’ times – before the crisis. Euros earned by German companies in Greece, and elsewhere in the Periphery, amassed in the Frankfurt banks. This money increased Germany’s money supply lowering the price of money. And what is the price of money? The interest rate! This is why interest rates in Germany were so low relative to other Eurozone member-states. Suddenly, the Northern banks had a reason to lend their reserves back to the Greeks, to the Irish, to the Spanish – to nations where the interest rate was considerably higher as capital is always scarcer in a monetary union’s deficit regions.

And so it was that a tsunami of debt flowed from Frankfurt, from the Netherlands, from Paris – to Athens, to Dublin, to Madrid, unconcerned by the prospect of a drachma or lira devaluation, as we all share the euro, and lured by the fantasy of riskless risk; a fantasy that had been sown in Wall Street where financialisation reared its ugly head.

Crucially, the private capital inflows from a country like Germany to a country like Greece, alter the structure of B’s economy. A large, inefficient service sector develops in the Greece’s while periphery’s manufacturing wanes under the inexorable pressure of the surplus countries exports. While manufacturing wages collapse in absolute and per worker terms, the portion of the wage bill that comes from this parasitic, import-and-debt financed sector rises. And so does the corrupt oligarchy in the Periphery, house prices and a false sense of wealth. To sum this up in a vulgar but accurate manner, this is similar to buying a car from a dealer who also provides you with a loan so that you can afford the car. Vendor-finance, is the term used. Only in Europe we practised it at a macroeconomic level.This is similar to buying a car from a dealer who also provides you with a loan so that you can afford the car.

Irresponsible borrowers and irresponsible lenders

I think you can see the problem? To maintain a nation’s trade surpluses within a monetary union the banking system must pile up increasing debts upon the deficit nations. Yes, the Greek state was an irresponsible borrower. But, ladies and gentlemen, for every irresponsible borrower there corresponds an irresponsible lender. Take Ireland or Spain. Their governments, unlike Greek ones, were not irresponsible. But then the Irish and the Spanish private sectors ended up taking up the extra debt that their government did not. Total debt in the Periphery was the reflection of the surpluses of the Northern, surplus nations.

This is why there is no profit to be had from thinking about debt or surplus in moral terms. And this is why my message to my German friends is simple: before the crash, we Greeks invested our loans and transfers unwisely. But you invested your savings, your surpluses, unwisely.

Let’s take a dispassionate look at Germany’s current account: it is large, persistent, and extraordinary in international and historical comparison for a large country that is not focused on exporting raw materials. This means that your savings are increasingly entrusted to the hands of foreigners who do not have the capacity to look after them. Germany’s net international investment position is over 50% of GDP, after discounting past investments that have lost about 15% of GDP worth in the crisis. Moreover, the German surpluses are mostly due to the non-financial corporate sector, followed by government, with only a modest contribution by households and financial corporations having actually turned to a net borrowing position. So, it is not the demographics that drive the CA surplus in this country. It is the euro’s architecture.

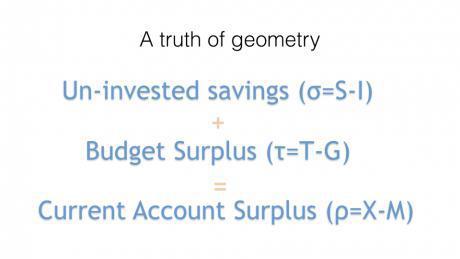

When σ>0 everywhere, and we push τ to zero, we are forced to a large trade surplus – which pushes the euro up and strengthens… Trump.

Will σ not equilibrate in the periphery if wages and prices fall? Will internal devaluation – austerity not do the trick? No, because private and public debts and losses do not devalue – and investment is deterred by this loop of doom, by this recycling of state and private bankruptcies. Even in countries like Spain and Ireland, the growth we have been celebrating recently is due to another unsustainable rise of private debt.

And this is where the rules become impossible and the EU’s attempt to pretend that they still hold ridiculous.

An example of Europe’s Ponzi schemes by which to pretend that the rules were adhered to:

In the rest of the lecture (last 20 minutes), Varoufakis argues that, instead of the wrong question (“How can we pretend that the rules still hold?’) we must ask the right questionL: ‘ What must we do to stop this crisis from destroying us?’ – see the video above. Finally, Varoufakis outlines two stark options: (a) The controlled dismantling of the current Eurozone, or (B) a simulation of a federation. ( Video 58 minutes in all).

For the subsequent Q & A ( 23 minutes), see below:

Η Ελλάδα στον κόσμο του κ. Τραμπ – ΕφΣυν 14 Ιουλίου 2018

Ας δούμε επιγραμματικά τις τρεις πτυχές του προβλήματος που το Μνημονιακό Τόξο του Νυν Υπέρ Πάντων το Ευρώ (Ν.Δ.-ΚΙΝ.ΑΛΛ.-ΠΟΤΑΜΙ-ΣΥΡΙΖΑ) αρνείται να δει:

Σε λίγους μήνες συμπληρώνεται δεκαετία από το κραχ του 2008 –μια δεκαετία κατά την οποία η Ε.Ε. πασχίζει να «κουκουλώσει» την κρίση της ευρωζώνης (αντί να την επιλύσει). Το αποτέλεσμα είναι η απαξίωση της Ε.Ε. στα μάτια της πλειονότητας των χειμαζόμενων Ευρωπαίων πολιτών, κάτι που φουντώνει την εκλογική δύναμη της Εθνικιστικής Διεθνούς (τόσο στα νέα ακροδεξιά κόμματα όσο και εντός παραδοσιακών συντηρητικών, αλλά και αριστερών, κομμάτων)

Τον επόμενο μήνα συμπληρώνεται τριετία από τότε που οι αυξημένες μεταναστευτικές ροές δημιούργησαν μεταναστευτική «κρίση» που ούτε καν να την «κουκουλώσει» δεν μπόρεσε η Ε.Ε. –μια «κρίση» που δεν θα την είχαμε βέβαια προσέξει αν υπήρχε Ευρωπαϊκή… Ενωση (δεδομένου ότι κάθε χώρα έδρασε ως τσαμπατζής που απαιτεί να λύσουν το πρόβλημα «άλλοι»).

Σήμερα, με την ευρωπαϊκή ήπειρο θύμα αυτών των φυγόκεντρων μακρο-οικονομικών δυνάμεων, κατακερματισμένη πολιτικά και καταρρακωμένη ηθικά, οι κινήσεις τεκτονικών γεωπολιτικών πλακών που ενορχηστρώνει ο πρόεδρος Τραμπ στενεύουν απελπιστικά τα περιθώρια επιβίωσης της Ε.Ε.

Ο σκοπός του κ. Τραμπ

Ο Αμερικανός πρόεδρος ενδιαφέρεται για ένα πράγμα μόνο: πώς θα καθυστερήσει τη συρρίκνωση της ηγεμονίας των ΗΠΑ σ’ έναν κόσμο ο οποίος θέλει να αγοράσει όλο και μικρότερο ποσοστό αγαθών Made in USA.

Ο κ. Τραμπ βλέπει τα οικονομικά θαύματα της Ιαπωνίας, την Κίνας και βεβαίως της Ε.Ε. ως κατασκευάσματα των ΗΠΑ καθώς:

■ χωρίς την άμεση βοήθεια και συστηματική διαχείριση της ευρωπαϊκής πολιτικής σκηνής, από το 1945 έως το 2008, η Ε.Ε. δεν θα υπήρχε καν,

■ χωρίς το άνοιγμα των αμερικανικών αγορών στη δεκαετία του 1950, η Ιαπωνία θα ήταν σήμερα φτωχότερη της Ταϊλάνδης,

■ χωρίς το εμπορικό έλλειμμα των ΗΠΑ τής μετά το 1990 περιόδου, η Κίνα δεν θα είχε ποτέ αναπτυχθεί.

«Εμείς σας δημιουργήσαμε -μας χρωστάτε ό,τι έχετε δημιουργήσει από το 1945 μέχρι σήμερα. Αλλά αντί να δείχνετε ευγνωμοσύνη, όχι μόνο δεν πληρώνετε καν για την άμυνά σας (*), αλλά απαιτείτε να εξάγετε σε εμάς τη δική σας κρίση μέσω όλο και μεγαλύτερων εμπορικών πλεονασμάτων (**) προς εμάς. Αυτά που ξέρατε ώς τώρα, τέλος!»

Κάπως έτσι σκέφτεται, και ομιλεί, ο πρόεδρος Τραμπ κάθε φορά που συναντά την κ. Μέρκελ και τους λοιπούς ηγέτες του G20. Βέβαια ο απώτερος στόχος του είναι η κατάργηση της συν-ηγεμονίας του καπιταλιστικού κόσμου με Ε.Ε., Καναδά και Ιαπωνία και η δημιουργία ενός νέου παγκόσμιου καπιταλισμού που να θυμίζει τροχό ποδηλάτου: με τις ΗΠΑ να είναι το κεντρικό ρουλεμάν/άξονας και τους υπόλοιπους (Γερμανία, Γαλλία, Ιαπωνία, Κίνα κ.λπ.) να είναι οι ακτίνες του τροχού.

Στο μυαλό του κ. Τραμπ με μια τέτοια «αρχιτεκτονική» οι ΗΠΑ-ρουλεμάν θα κυριαρχούν πάντα επί κάθε μιας των ακτίνων. Σε αυτό το πλαίσιο η Ε.Ε. δεν έχει ρόλο και η αποδόμησή της αποτελεί στόχο για τη χώρα, τις ΗΠΑ, που τη δημιούργησαν μετά τον Β’ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο.

Τα μέσα του κ. Τραμπ

Ακολουθεί παράδειγμα των μέσων με τα οποία ο κ. Τραμπ διαιρεί την Ε.Ε. ώστε να τη βοηθήσει να ολοκληρώσει την αποδόμησή της:

■ Η Γερμανία έχει τεράστιο εμπορικό πλεόνασμα με τις ΗΠΑ, με τις εξαγωγές γερμανικών αυτοκινήτων να παίζουν πρωταγωνιστικό ρόλο.

■ Η Γαλλία δεν έχει εμπορικό πλεόνασμα με τις ΗΠΑ, ιδίως ως προς την αυτοκινητοβιομηχανία της η οποία επιβιώνει λόγω των δασμών ύψους 10% που ισχύουν για τα εισαγόμενα σε χώρες της Ε.Ε. αυτοκίνητα.

Ο Αμερικανός πρόεδρος ανακοινώνει δασμούς 20% για όλα τα εισαγόμενα στις ΗΠΑ αυτοκίνητα, στη βάση ότι οι ΗΠΑ χρεώνουν μόνο 4% δασμούς –αντίθετα με την Ε.Ε. που χρεώνει 10%. Προσέξτε τι πετυχαίνει:

Τουλάχιστον 5 δισ. δημόσια έσοδα μόνο από τις πωλήσεις γερμανικών αυτοκινήτων στις ΗΠΑ.

Το Βερολίνο προτείνει την εκατέρωθεν «ειρήνη» με κατάργηση των δασμών στα αυτοκίνητα τόσο εκ μέρους των ΗΠΑ όσο και της Ε.Ε.

Το Παρίσι εξαγριώνεται καθώς Ρενό και Πεζό πλήττονται θανάσιμα από ιαπωνικά και κορεατικά εισαγόμενα αυτοκίνητα μετά την κατάργηση δασμών της Ε.Ε. ύψους 10%.

Με τέτοια μέσα ο κ. Τραμπ διαιρεί και βασιλεύει…

Το ψευτοδίλημμα

Μέρκελ, Μακρόν και λοιπές κατεστημένες δυνάμεις προσποιούνται ότι ο Τραμπ είναι ένα περαστικό «κακό», ότι η ευρωζώνη μεταρρυθμίζεται κ.λπ. Πρόκειται για το Σύνδρομο της Αρνησης.

Η Επιλογή της Αποδόμησης: δυνάμεις τόσο της Δεξιάς όσο και της Αριστεράς απαντούν: «Ας διαλυθεί η Ε.Ε. Ας επιστρέψουμε στο κράτος-έθνος μετά την αποτυχία της Ε.Ε.» -με τη δεξιά έκδοση να υιοθετεί τη γραμμή Τραμπ («Να ξανακάνουμε τη Γαλλία/Γερμανία/Ιταλία κ.λπ. μεγάλη!») και την αριστερή έκφανση (π.χ. Μελανσόν) να προκρίνει το αυτόνομο κράτος-έθνος ως τη βάση για τον σοσιαλιστικό διεθνισμό.

Η δική μας θέση, ως ΜέΡΑ25 και ως DiEM25, είναι πως πρόκειται για ψευτοδίλημμα: Τόσο η Αρνηση όσο και η εσκεμμένη Επιλογή της Αποδόμησης οδηγούν ακριβώς σε αυτό που θέλει ο κ. Τραμπ: την αποδόμηση της Ε.Ε. με τρόπο που θα φουντώσει τον εθνικισμό, θα ενισχύσει την ξενοφοβία, θα του επιτρέψει να έρθει σε μια συμφωνία ΗΠΑ-Κίνας που αφήνει την Ευρώπη απέξω και εν τέλει θα επεκτείνει στο διηνεκές την αμερικανική επικυριαρχία.

Και η Ελλάδα;

Στο μεταξύ στη χώρα μας το κατεστημένο ζει τον μύθο του, έχοντας καταφέρει -με την αρωγή της τρόικας- να κάνει ένα κόμμα της Αριστεράς, τον ΣΥΡΙΖΑ, να ενστερνιστεί ως κυβέρνηση όλες του τις αμαρτίες:

● υιοθέτηση των αποτυχημένων πολιτικών μιας ανοήτως αυταρχικής Ε.Ε.,

● ταύτιση του ευρωπαϊσμού με τη συνθηκολόγηση στην τρόικα,

● άκριτη αποδοχή όλων των ΝΑΤΟϊκών επιταγών στην περιοχή,

● συμμαχία με το Ισραήλ του Νετανιάχου.

Ομως αυτός ο θρίαμβος είναι ρηχός καθώς, για πρώτη φορά από το 1950, η Ε.Ε., που το ελληνικό κατεστημένο λαμβάνει ως δεδομένη, αποδομείται ηθελημένα από την υπερδύναμη που την έχτισε. Για εμάς, για το ΜέΡΑ25-DiEM25, μία είναι η επιλογή: ένα πανευρωπαϊκό κίνημα υπεύθυνης ανυπακοής τόσο στη λογική της Εθνικιστικής Διεθνούς, που τόσο πονηρά δημιούργησε και καθοδηγεί ο κ. Τραμπ, όσο και στην αυταρχική ανοησία του ευρωπαϊκού κατεστημένου.

(*) Πράγματι το Βερολίνο έχει παράδοση να ψέγει όσες κυβερνήσεις παραβιάζουν τους συμφωνημένους ποσοτικούς κανόνες, την ώρα που το ίδιο καταστρατηγεί ποσοτικούς κανόνες που δεν το συμφέρουν –π.χ. τη δέσμευση ότι φέτος θα ξόδευαν 1,5% του ΑΕΠ για την άμυνα ανεβάζοντας το ποσοστό αυτό στο 2% μέχρι το 2024, κάτι που δεν έχει σκοπό να κάνει η κ. Μέρκελ, ή το όριο του 6% του ΑΕΠ για το εμπορικό ισοζύγιο της χώρας (το οποίο ξεπέρασε το 8% εδώ και καιρό).

(**) Οταν μια οικονομία όπως η ευρωζώνη επιβάλλει λιτότητα στους πολίτες της (δηλαδή περικοπές και φόρους που στοχεύουν στα πρωτογενή πλεονάσματα), την ώρα που οι συνολικές αποταμιεύσεις ξεπερνούν τις συνολικές επενδύσεις, τότε νομοτελειακά αυξάνει το συνολικό εμπορικό πλεόνασμα. Με απλά λόγια, η οικονομία αυτή εξάγει την κρίση της στις χώρες με τις οποίες εμπορεύεται, π.χ. τις ΗΠΑ. Αυτό το γνωρίζει καλά ο κ. Τραμπ και είναι ο βασικός λόγος που εχθρεύεται την Ε.Ε. γενικά και την ευρωζώνη πιο συγκεκριμένα.

INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISM, NOT SOCIALISM IN ONE COUNTRY: On the UK Left’s relation with Europe – Open Labour document

Why is this Pamphlet important? In this pamphlet we outline the future options for a new EU-UK relationship:

Staying in the EU

The Customs Union

A Customs Union III. Norway, an EEA option and/or a new Single Market option

A Free trade deal

No deal

Contributions by:

Yanis Varoufakis, DiEM25 co-founder, MeRA25 Secretary (page 28)

Richard Corbett MEP (page 40)

Catherine West MP (page 11)

Manuel Cortes, General Secretary TSSA (page 17)

FOR THE COMPLETE PAMPHLET CLICK HERE

July 5, 2018

An anniversary to savour: the three days that shook Europe – 3rd to 6th July 2015 (Extracts from my ADULTS IN THE ROOM)

On the 5th of July 2015 the people of Greece wrote a stupendous chapter in the annals of the global struggle for democracy. It should be remembered as such, independently of what happened next. For, during these three days that shook Europe,

They turned a deaf ear to the local oligarchy’s hysterical threats

They laughed at the tv stations’ warning that voting No (OXI) to the troika’s ultimatum would bring Armageddon

They shrugged their shoulders when the European Central Bank, after having engineered a six-month long bank run, tried to throttle our democracy by closing down the banks (to punish our government for daring give the people the final say on the troika’s ultimatum).

And,

They flocked at the polling stations to deliver an astounding, brave, unprecedented 62% rejection of the international and local power-hungry establishment’s ultimatum.

Every 5th of July Europe’s and Greece’s establishment revisits its paroxysm of anger at having lost control of the Greeks – even if briefly. They just cannot fathom the fact. They feel compelled to vilify those who dared vote No on the 5th of July 2015. And, of course, they demonise any politician who underpinned that No vote and who continue to honour it to this day.

This is, of course, why the troika of lenders, together with their Greek agents, continue to vilify me, personally, especially around the beginning of July… As I promised in my letter of resignation in the wee hours of 6th July 2015, I wear their loathing as a badge of honour.

Below I copy the part of my ADULTS IN THE ROOM memoir pertaining to those magnificent three days.

Square of hope and glory

On the afternoon of Friday 3 June, as the working day drew to a close, I breathed a sigh of relief. A week of closed banks was almost over. Despite the long queues for ATMs and the uncertainty of what awaited us the following Monday, there had been no violence, no panic, no civil unrest. Greeks proved their credentials as a most sensible lot.

The media, however, had managed to fall below their already absurdly debased standards, competing with one another to find the most innovative ways to scare the public away from voting NO. Much of their reporting of the NO sponsors and supporters would in other countries be deemed incitement to violence. Their opinion polls consistently predicted that YES would win with more than 60% of the vote while their commentariat foamed at the mouth at the government’s audacity in holding the referendum against the creditors’ wishes. Meanwhile, the parliamentary opposition was managing to persuade its supporters to take to the streets in some numbers, waving EU flags and placards boasting, “We are staying in Europe!”

Later that Friday afternoon, I received an email from Klaus Regling, the Managing Director of the European Stability Mechanism, the Eurozone’s bailout fund. It was a reminder that he had the legal right to demand from me full and immediate repayment of the €146.3 billion lent to Greece as part of the first two bailouts. It was phrased in such a way as to suggest that I was personally liable, not least because, as finance minister, my name was on the loan agreement. It was too good an opportunity to pass up. I instructed my office to reply to our main creditor – and to the man who had advised me to default to my pensioners instead of the IMF – with two ancient words. They were the defiant response of the King of Sparta, leader of the 300 men who attempted to resist the entire Persian army at the legendary battle of Thermopylae in 480BC, when instructed by their enemy to throw down their weapons: “Μολών λαβέ” – ‘Come and get them!’

That evening, two rallies were organised, one in favour of YES, outside the ancient Olympic stadium where the first modern Olympics were staged in 1896, and one at Syntagma Square held by the NO campaign. The YES rally was held in the late afternoon. It was large and good-natured. But the NO rally at Syntagma was to be one for the ages. Since I was a boy, I had attended some magnificent, life-changing rallies at Syntagma Square. But what Danae and I participated in that night was unprecedented.

We walked to Syntagma from Maximos with Alexis and other members of the cabinet, their partners and aides. On the way we were mobbed by rapturous supporters. As we approached the square, the crowd’s energy exploded. A sea of five hundred thousand bodies consumed us. We were pulled into its depths by a forest of arms: tough-looking men with moist eyes, middle-aged women with determination written all over their faces, young boys and girls offering boundless energy, older people eager to hug us and shower us with good wishes, a pulsating magma of humanity into whose ebb and flow we surrendered. For two hours, struggling to hold hands so as not to be separated, Danae and I were absorbed into a single body of people who had simply had enough.

People from different generations saw their distinct struggles coalesce on that night into one gigantic celebration of freedom from fear. An elderly partisan pushed into my pocket a carnation and a piece of paper bearing the phrase “Resistance is NEVER futile!” Students forced to emigrate by the crisis who had returned to cast their vote begged me not to give up. A pensioner promised me that he and his sick wife did not mind losing their pensions as long as we recovered their dignity. And everybody, without a single exception, shouted at me, “No surrender, whatever the cost!”

This time, I believed they meant it. The banks had already been closed for a week. The hardship imposed by the creditors was plainly visible. And yet, here they were, these magnificent people saying in one word everything that had to be said: No! Not because they were recalcitrant or Eurosceptic. They craved an opportunity to say a big, fat yes to Europe. But yes to a Europe for its people, as opposed to a Europe hell-bent on crushing them.

That night, as Danae and I eventually found ourselves walking up the marble steps leading to Parliament, the phrase I had been looking for to describe what all this was about finally came to me: constructive disobedience. These people, with their pragmatic defiance, had given it to me. This is what I had been trying to practise in the Eurogroup all along: putting forward mild, moderate, sensible proposals, but when the deep establishment refused even to engage in a negotiation, to disobey their commands and say No! Our War Cabinet had never understood this, but the body of humanity that filled Syntagma Square that night surely did.

The first pro-troika rally took place in Syntagma Squareon 18 June, while I was in Brussels at one of the many Eurogroup meetings. A good ten to fifteen thousand people gathered, making Alexis and the rest of us feel uneasy.

One for true believers

That night, I felt the months of frustration, each terrible moment in Maximos, every disappointment along the way, all the nastiness and the stress had been wiped away, leaving nothing but contentment. And yet, I was still not convinced that the NO campaign would win the referendum. The demonstration at Syntagma suggested support for the cause had risen, but with the banks closed and the media screaming blue murder at anyone who contemplated NO, success looked unlikely. Over dinner with Danae, Jamie and some other friends at an outdoors restaurant in the neighbourhood of Plaka, I was asked if Alexis and Euclid would resign were YES to win. “Alexis will form a coalition government with the opposition,” I predicted, “after most of the true believers resign or are pushed.” Naturally, I would be long gone by then, I said. But Jamie insisted I was wrong. NO would win, he believed, and my leverage with Alexis would skyrocket, as I would have played a large part in delivering it to him. Unconvinced, I nonetheless raised my glass to toast Jamie’s optimism. “Hasta la vittoria siempre!” he said with an intense and committed look – ‘To victory, always!’

On the day of the referendum, I drove to Palaio Phaliro, the southern Athenian suburb where I grew up and where my father still lives. Together we made our way to the polling station. Inside, the majority of voters were ebullient when they saw me, except for one or two who remonstrated angrily that I had closed down the banks. With the television cameras rolling, I replied that the troika had given us an ultimatum and that accepting it would shape his and his children’s future. What we had done was to give him the opportunity to vote for or against it. “Vote YES if you think it is a manageable deal. We are the only government that respected your right to decide. The fact that the troika decided to close the banks down before you got a chance to express yourself is something that only you can interpret.” The man was I addressing seemed to calm down.

After voting, as I was helping my dad walk back to the car, an elderly woman approached me, surrounded by the usual television cameras. With a stern expression she asked me if I knew where she lived. I admitted I did not. “Ι sleep in an orphanage here in Palaio Phaliro. And do you know why they let me? Because your mother worked tirelessly to let vagrants like me have a permanent shelter.” I thanked her for the spontaneous and wonderful remembrance of my mum. But she was not finished. “I bless her every day. But do these bastards know this?”, she said pointing at the cameras and the TV crews. “I bet they don’t and they don’t even care.”

“It does not matter,” I assured her. Even if they didn’t, it was enough that she knew. Nonetheless, I must admit I was perturbed when in the evening news our heart-warming encounter was presented as me being accosted by a homeless woman blaming me for her destitution.

It was not until late that afternoon that I began to sense an historic victory might be on the cards. At my office I composed a piece, in English, for my blog. “In 1967,” I wrote, “foreign powers, in cahoots with local stooges, used tanks to overthrow Greek democracy. In 2015 foreign powers tried to do the same by using the banks. But they came up against an insanely brave people who refused to submit to fear. For five months, our government raged against the dying of the light. Today, we are calling upon all Europeans to rage with us so that the flickering light does not dim anywhere, from Athens to Dublin, from Helsinki to Lisbon.”

By 8pm I could see from the drooping shoulders and morose expressions of TV presenters that we had won. What I did not yet know was the extent of our victory. My fear was that a close shave would give Alexis the excuse to say we had a divided nation and, thus, insufficient support for a rupture with the troika. I told my team that the magic number was 55%. If the votes for NO were any greater, Alexis would have to honour them. I thought carefully of what I would say to the gathered journalists in my ministry’s pressroom in order to give him the necessary impetus to do so. By 9pm, I had written my speech. Traditionally, ministers wait for the Prime Minister to make his statement before issuing their own. So, I waited in my office for Alexis to address the press at Maximos’ pressroom.

At 9.30 I began to feel something was wrong. The results were more or less final, indicating that the 55% mark had been attained, but Alexis was still holed up in his Maximos office. My chief of staff was pressurising me to go to our pressroom as the journalists were getting agitated and were beginning to tweet that something sinister was afoot. I waited until after 10.00pm. I called Alexis. He did not pick up, and nor did his secretaries. Wassily walked in to inform me that other ministers were beginning to speak to the media, issuing lukewarm statements in response to what was in fact an earth-shattering outcome. I could not allow this to continue. Our voters deserved a proper response.

So, at around 10.30, I headed for the pressroom to make my statement with the intention of going to Maximos straight afterward, anxious to discover what was going on there. While reading out my prepared statement I had a very strong feeling that it would be my last as minister. That feeling, combined with the memory of Syntagma Square two nights earlier, made me read it defiantly, brazenly even:

On the twenty-fifth of January, dignity was restored to the people of Greece. In the five months that intervened since then, we became the first government that dared raise its voice, speaking on behalf of the people, saying NO to the damaging irrationality of our extend-and-pretend bailout program. We confined the troika to its Brussels’ lair; articulated, for the first time in the Eurogroup, a sophisticated economic argument to which there was no credible response; internationalised Greece’s humanitarian crisis and its roots in intentionally recessionary policies; spread hope beyond Greece’s borders that democracy can breathe within a monetary union hitherto dominated by fear.

Ending interminable, self-defeating, austerity and restructuring Greece’s public debt were our two targets. But these two were also our creditors’ targets. From the moment our election seemed likely, the powers-that-be started a bank run and planned, eventually, to shut Greece’s banks down. Their purpose? To humiliate our government by forcing us to succumb to stringent austerity. And to drag us into an agreement that offers no firm commitments to a sensible, well-defined debt restructure.

The ultimatum of the twenty-fifth of June was the means by which they planned to achieve these aims. The people of Greece today returned this ultimatum to its senders, despite the fear-mongering that the domestic oligarchic media transmitted night and day into their homes.

Our NO is a majestic, big YES to a democratic Europe. It is a NO to the dystopic vision of a Eurozone that functions like an iron cage for its peoples. But it is a loud YES to the vision of a Eurozone offering the prospect of social justice with shared prosperity for all Europeans.

As I stepped out into Syntagma Square, I saw delight in the faces around me. A proud people had been vindicated and were justly celebrating. The night’s air was full of anticipation and confidence. Alexis’ silence had filled me with apprehension but I refused to believe that Maximos could be sealed off entirely from that intoxicating air of defiance. Surely, I thought, it find its way in through some crack in the walls or through the hearts of the people working there who had also learned their politics at Syntagma Square. And yet, as I walked in, Maximos felt as cold as a morgue, as joyful as a cemetery.=

The overthrowing of a people

As I walked through the main entrance to Maximos, the ministers and functionaries I encountered looked numb, uncomfortable in my presence, as if they had just suffered a major electoral defeat. Alexis was meeting with the President in the adjacent Presidential Palace and would see me later, his secretary informed me. So, I waited in the conference room with other ministers, watching as the last results were declared on television. When the final number flashed up on the screen, 61.31% for NO out of a high turnout of 62.5%, I jumped up and punched the air, only to realise that I was the only one in the room celebrating.

As I sat and waited for Alexis, I found a message on my phone from Norman Lamont: “Dear Yanis, congratulations. A famous victory. Surely they will listen now. Good luck!” They would listen, I thought, but only if we were prepared to speak up. Sat there, witnessing in slow motion the annulment of our famous victory, I began noticing things about the people around me that had previously escaped me. The men had shed the rough Syriza look andresembled smartly attired accountants. The women were dressed as if for a state gala. When Danae joined me, I realised that not only were we the only happy people in the place but the only ones in jeans and t-shirts. It felt a little like being in one of those sci-fi movies in which body-snatching aliens have quietly taken over.

Eventually, Alexis walked into Maximos and, half an hour later, addressed the nation. Two key phrases in his speech unlocked the vault of his intentions. One ruled out a rupture with the troika. The other was his announcement that he had just asked the President to convene immediately the council of political leaders: on the morning after their decisive defeat, the pro-troika leaders of the ancien regime were being summoned to join him at the discussion table. “He is splitting Syriza up and preparing a coalition with the opposition to push the troika’s new bailout through,” I told Danae. I waited another hour and a half as he held separate meetings with Sagias and Roubatis before he would receive me.

It was after 1.30am when I entered his office. Alexis stared at me and said we had messed up badly.

“I do not see it that way,” I replied flatly. “There were plenty of mistakes but on a night of such a triumph we have a duty to rejoice and honour the result.”

Alexis asked me if I minded if Dimitris Tzanakopoulos, Maximos’ legal adviser, sat in on our meeting.

“Sure,” I replied. “In fact I want him to be here as a witness.” This was not going to be just another chat.

Alexis asked if the banks would open soon. It was a trick question. He was looking to justify his decision to capitulate. I pretended not to understand, saying that to honour the NO vote, we had immediately to start issuing electronic IOUs backed by future taxes and to haircut Draghi’s SMP bonds. “Without these moves to bolster your bargaining power,” I said, “the 61.3% will be scattered in the winds. But if we announce this tonight, with 61.3% of voters backing us, I can assure you that Draghi and Merkel will come to the table very quickly with a decent deal. Then the banks will open the next day. If you don’t make this announcement, they will steamroll over you.” I explained that I needed only a couple of days to activate this system using the tax office’s website. He pretended to be impressed, so I continued: “This 61.3% result is a capital asset that you must use well. You must manage it with greater respect to the people out there than you showed before the referendum. You must respect yourself more, too. After tonight you have a simple choice. Either you will re-activate our plan, giving me the tools I need, or you will surrender.”

We talked for a long time. We reviewed the previous months, weeks and days. I took no prisoners, providing a litany of his errors, pointing out the ways in which members of our War Cabinet had jeopardised our struggle, often in collaboration with the troika and its operatives. I shared with him evidence of one of them behaving in such a way that bordered on corruption. Looking surprised, he asked Dimitris his opinion: was the person I referred to such a problem? Dimitris answered: “Yes, and even more so.”

The conversation was meandering, so I decided to put it to him straight: would he honour the NO vote, I asked, by going back to our original Covenant? Or was he about to throw in the towel? His answer was elliptical but there was no mistaking the direction in which it headed: towards unconditional surrender. The first time in that conversation that he spoke decisively was when he said, “Look, Yani, you are the only one whose predictions were confirmed. But here is the problem: if any other government had given them what I did, the troika would have sealed the deal by now. I gave them more than Samaras ever would. And they still wanted to punish me, as you had said they would. But let’s face it: they do not want to give an agreement either to you or to me. Let’s be honest. They want to overthrow us. However, with the 61.3% they cannot touch me now. But they can destroy you.”

“Don’t worry about me, Alexi,” I said. “Worry about honouring the folks out there who are celebrating tonight while you are planning to give in. If we were to stick together, activate our deterrent, and show to them that we are united, they would touch neither you nor me. We could propose to them a deal that they could package credibly as their own idea, their own triumph.”

At that point Alexis confessed to something I had not anticipated. He told me that he feared that a ‘Goudi’ fate awaited us if we persevered – a reference to the execution of six politicians and military leaders in 1922. I laughed it off, saying that if they executed us after we had won 61.3% of the vote, our place in history would be guaranteed. Alexis then began to insinuate that something like a coup might take place: he told me that the President of the Republic, Stournaras, our intelligence services and members of our government were in a ‘readied state’. Again I fended him off: “Let them do their worst! Do you realise what 61.3% means?”

Alexis told me that Dragasakis had been trying to persuade him to get rid of me, everyone from the Left Platform and Kammenos’ Independent Greeks and, instead, forge a coalition government with New Democracy, PASOK and Potami. Dragasakis had assured him that once the agreement with troika had been signed, Alexis could then get rid of New Democracy, PASOK and Potami and bring me back. I told him it was the dumbest idea I had ever heard. He smiled in agreement, using an expression for Dragasakis that is not reproducible here.

“But,” he added, “there is something to the idea of proceeding in two ways, one public one hidden. Publically, we can approach the creditors with a rightwing posture involving a reshuffle that says “we are good kids now”. But, at the same time, hidden from public view, we can prepare the counter-strike.”

“This is bad thinking, Alexi,” I told him. “Look, tonight the people voted. They did not vote NO for you to turn it into a YES.” I told him he had come out and say what I had said in my press statement earlier: that the NO vote had given him the mandate he required to bring about a solution in cooperation with our European partners. “Add some complimentary words for the Commission, the IMF, even for the ECB, to illustrate that we mean it when we say we want a cooperative solution. But simultaneously project strength! None of this nonsense about preparing for an underground war in the catacombs of our state.” I told him that whatever we did now, we had to do it out in the open. We had to state clearly that we were preparing our own liquidity, as we had a duty to do when the ECB was keeping our banks closed. And we had to state clearly that the ECB’s SMP bonds would be restructured according to Greek law, the law under which they were created.

“It will be very difficult for them to give us a solution, Yani,” he said.

“You keep making the mistake of thinking of a solution as something that they give to us,” I replied. “This is not the right way to think about it. They need a solution as much as we do. It is not something that they hand out. We must extract it from them. But this requires that we have a credible threat. The SMP haircut and our own liquidity is exactly that!”

We were going around in circles, our bodies and minds wrecked by fatigue. So I told him that, since he had made his mind up to surrender one way or another, he had better just tell me what he had decided to do now. He said that he was thinking of reshuffling the Cabinet so as to stop the troika, the creditors and the media from targeting me. He asked me who I thought should replace me at the finance ministry. He had clearly decided who it would be already, but I decided to play along, suggesting the person who I was certain had agreed to take over from me already: my good mate Euclid. I even offered to try to convince Euclid to accept. (And when I did, Euclid pretended he needed to think about it.)

“I would like to ask you to take over the Economy Ministry, so as to team up again with Euclid,” Alexis said.

“What about Stathakis?” I asked.

“I will be happy not to see him in front of me again. Let him vanquish at the backbenches.”

“No, Alexi, I am not interested.” I told him. “You met me because I turned Greece’s debt into the dragon to be slain, and because of my proposals for how to slay it. I live, breathe, think and dream of debt restructuring, of a reduction in surplus targets, an end to austerity, tax rate reductions and the redistribution of wealth and income. Nothing else interests me. To assume the Economy Ministry to manage the EU’s structural fund handouts, just so as to remain minister, is not something I care for. Do you recall why I moved from America? Because you asked me to help you to liberate Greece financially. I ran for Parliament not because I was dying to be an MP but because I did not want to be a technocrat, an unelected finance minister. I thought that that way I would be more useful to the cause. Now, given your abandonment of that cause, I have no reason to be minister. It’s OK. Let someone else do it. I shall be in Parliament where I will help to the best of my ability.”

“You can have some other ministry – maybe Culture, which you and Danae know so much about?” he said laughing. “In any case, there will be many positions in the future from which you can help.”

“You are again confusing me with someone who cares about positions, Alexi. There is only one thing I care about and you know what it is!”

“Let’s sleep on it, let’s think about it.”

“There is nothing to think about,” I said. “There is no time. You have a lot to do.”

When I saw Danae afterwards, she asked me what had happened. “Tonight we had the curious phenomenon of a government overthrowing its people,” I mused.

Minister no more

Back at the flat, I narrated my discussion with Alexis for Danae and her camera and slept for a couple of hours before writing my seventh, and final, resignation letter. After proofreading it a few times, I posted it on my blog under the title ‘Minister No More’. It was one of the hardest pieces of prose I had ever had to compose.

On the one hand, I had a duty to warn the people, our democracy’s demos, that their mandate was about to be trashed. On the other hand, I felt an obligation to preserve whatever progressive momentum there was within our government and within Syriza. At that stage I still believed strongly that comrades like Euclid, with clout in the party that I lacked, would not sign up to the surrender document Alexis and Dragasakis were preparing. Losing a second finance minister in a month or two, if Euclid refused to become complicit in another harsh and hopeless bailout, might cause a rupture within the government and the party. This in turn might lead to new elections, which might further undermine the chances of our honouring the wishes of the 61.3%. I needed to signal both a defiant commitment to the NO vote but also to issue a call for unity. The result was the following text:

Like all struggles for democratic rights, so too this historic rejection of the Eurogroup’s 25th June ultimatum comes with a large price tag attached. It is, therefore, essential that the great capital bestowed upon our government by the splendid NO vote be invested immediately into a YES to a proper resolution – to an agreement that involves debt restructuring, less austerity, redistribution in favour of the needy, and real reforms.

Soon after the announcement of the referendum results, I was made aware of a certain preference by some Eurogroup participants, and assorted ‘partners’, for my… ‘absence’ from its meetings; an idea that the Prime Minister judged to be potentially helpful to him in reaching an agreement. For this reason I am leaving the Ministry of Finance today.

I consider it my duty to help Alexis Tsipras exploit, as he sees fit, the capital that the Greek people granted us through yesterday’s referendum.

And I shall wear the creditors’ loathing with pride.

We of the Left know how to act collectively with no care for the privileges of office. I shall support fully Prime Minister Tsipras, the new Minister of Finance, and our government.

The superhuman effort to honour the brave people of Greece, and the famous NO that they granted to democrats the world over, is just beginning.

With hindsight, I should have sounded a much louder alarm bell regarding Alexis’ intentions. That I did not reflects my misplaced trust in many people in our government, Euclid primarily, to carry out the task of preventing a recapitulation of the Samaras’ government. But I am not sure that a clearer warning would have made much difference. Everyone I have spoken to since that morning understood very well what had happened the moment they heard I had resigned on the night of our triumph.=

Thankfully, as well as the creditors and their groupies, there was one other person who was unconditionally happy at my decision. Daughter Xenia, who had come from Australia to see me two weeks before but had hardly laid eyes on me, upon hearing the news that I had resigned gave me a sleepy, early morning look and said: “Thank goodness, dad. What took you so long?”

———–

My mother, Eleni Tsaggaraki-Varoufaki, served as a local councillor and Deputy Mayor for the Palaio Phaliro Municipality for twenty years or so. She had, indeed, been responsible for the management of local facilities, including orphanages, that were converted into decent shelters for people young and old.

62.5% is very high a turnout given that no postal or remote voting is permitted.

His precise words were so offensive that I do not wish to reproduce them here.

The executed men were held responsible for the rout of the Greek army and the sacking of all ethnic Greek cities, villages and communities by the army of Kemal Ataturk and Turkish irregulars, eradicating all Greeks from Asia Minor where they had lived since Homer’s time. Hundreds of thousands died and even more flooded mainland Greece as refugees. A coup d’état ensued in Greece and a military tribunal was convened at which the political and military leaders of the disastrous campaign were found guilty of high treason.

June 30, 2018

Η γραβάτα ήταν θηλιά – EφΣυν 30 Ιουνίου 2018

Ενίσχυση του χαλύβδινου δεσμού μη βιώσιμου χρέους και σκληρής λιτότητας

Γιατί απαιτούσαμε αναδιάρθρωση χρέους το 2015; Γιατί από το 2010 την είχα αναδείξει στο κύριο ζητούμενο, σε βαθμό να με κατηγορήσουν (ορθώς) ακόμα και σύντροφοί μου ότι έχω «κόλλημα με το χρέος»; Για δύο λόγους.

1. Οσο το δημόσιο χρέος δεν είναι βιώσιμο, οι κυβερνήσεις αναγκάζονται να εφαρμόζουν σκληρή λιτότητα – στόχους πρωτογενούς πλεονάσματος πάνω από το 1,5% του εθνικού εισοδήματος ώστε να προσποιούμαστε ότι, από αυτά τα ματωμένα πλεονάσματα, θα αποπληρώνουμε το χρέος κανονικά για τις επόμενες δεκαετίες.

2. Οσο αυτό το παραμύθι συνεχίζεται, ακυρώνονται όλες οι σοβαρές επενδύσεις. Στόχοι πλεονασμάτων πάνω από το 1,5% σηματοδοτούν στους σοβαρούς επενδυτές απαγορευτική και αύξουσα φορολογία στο διηνεκές, σε μια οικονομία όπου η συνολική ζήτηση για προϊόντα και υπηρεσίες θα παραμένει καχεκτική.

Κανένας σοβαρός, υπομονετικός επενδυτής δεν πρόκειται να επενδύσει στην Ελλάδα σήμερα ή τις επόμενες δεκαετίες (εκτός από τους γνωστούς καιροσκόπους που πάντα θα έρχονται να κάνουν «αρπαχτές», χωρίς βέβαια να επενδύουν σε καλές θέσεις εργασίας).

Επιγραμματικά, το μη βιώσιμο χρέος ισοδυναμεί με πρωτογενή πλεονάσματα πάνω από 1,5% και, αντιστρόφως, πρωτογενή πλεονάσματα πάνω από το 1,5% ισοδυναμούν με μη βιώσιμο χρέος.

Με την πρόσφατη συμφωνία του Eurogroup ο στόχος του πρωτογενούς πλεονάσματος παραμένει στο 3,5% του εθνικού εισοδήματος για την επόμενη πενταετία και στο 2,2% για τα επόμενα… 38 χρόνια.

Τη μέρα που ανακοινώθηκε η συμφωνία ρώτησα:

«Τι να την κάνουμε την ελάφρυνση χρέους, σύντροφοι, αν η καταστροφική λιτότητα επεκταθεί για άλλη μια γενιά, που στο μεταξύ θα μεταναστεύσει στο εξωτερικό;»

Απάντηση δεν έλαβα. Τους ξαναρώτησα: «Ξέρετε άλλη χώρα που να έχει πετύχει πρωτογενές πλεόνασμα πάνω από 2,2% για 43 συναπτά χρόνια;»

Ούτε σε αυτό πήρα απάντηση. Τους ρωτώ άλλη μια φορά τώρα:

«Και τι θα γίνει όταν μια υστέρηση εσόδων ρίξει, εκ των πραγμάτων, το πρωτογενές πλεόνασμα στο 1,5%, που είναι το μέγιστο φυσιολογικό επίπεδο;»

Σε τούτο το ερώτημα δεν χρειάζεται η απάντηση της κυβέρνησης, καθώς την απάντηση την έδωσε το ίδιο το Eurogroup, η ανάλυση του οποίου δείχνει ότι, υπό τους όρους της συμφωνίας που πανηγυρίζει ο κ. Τσίπρας, ένα πρωτογενές πλεόνασμα στο 1,5% θα στείλει το δημόσιο χρέος στη στρατόσφαιρα το 2060 (πάνω από το 230% του εθνικού εισοδήματος).

Εν κατακλείδι, δεν χρειάζεται κανείς να μελετήσει τις τεχνικές λεπτομέρειες της πρόσφατης απόφασης του Eurogroup (βλ. πιο κάτω για τις λεπτομέρειες) ώστε να δει τι συνέβη.

Η διατήρηση των στόχων πρωτογενούς πλεονάσματος που ισοδυναμεί με μονιμοποίηση της σκληρής λιτότητας, την οποία θα επιβάλουν η τρόικα Ε.Ε.-ΔΝΤ-ΕΚΤ ανά τρίμηνο και για πάντα στο πλαίσιο της «ενισχυμένης επιτήρησης», τα λέει όλα.

Τι έκαναν και τι όχι: η ανατομία του 4ου Μνημονίου

Καμία από τις ελάχιστες κινήσεις που απαιτούνταν για να γίνει βιώσιμο το χρέος μας δεν έγινε. Ούτε κούρεμα. Ούτε μείωση του επιτοκίου. Ούτε διασύνδεση αποπληρωμών και ύψους του χρέους με το ονομαστικό ΑΕΠ και τον ρυθμό αύξησής του (τη λύση που προωθούσα το 2015 και την οποία, υποτίθεται, είχε ενστερνιστεί η κυβέρνηση του προέδρου Μακρόν).

Τι έγινε αντί για αυτά; Ενα 4ο Μνημόνιο, με νέα δανεικά και μόνιμη λιτότητα. Σε τι διαφέρει από τα προηγούμενα τρία Μνημόνια αυτό το 4ο Μνημόνιο που ονομάστηκε «Καθαρή Εξοδος από τα Μνημόνια»; Μόνο σε ένα: Αντί να εγκρίνουν νέο δάνειο (όπως συνέβη το 2010, το 2012 και το 2015), έκαναν τα εξής:

Μετέφεραν περί τα 24 δισ. δανείων του 3ου Μνημονίου που δεν είχαν χορηγηθεί για χρήση στους επόμενους 22 μήνες (ώστε η τρόικα να αποπληρώνει την τρόικα).

Μετέθεσαν αποπληρωμές περίπου 97 δισ. που θα έπρεπε να τους καταβάλουμε την περίοδο 2023-2032 από το 2ο Μνημόνιο για μετά το 2032, οπότε θα αποπληρωθούν με τόκο.

Οι υπόλοιπες αποπληρωμές (π.χ. στην ΕΚΤ, στο ΔΝΤ και σε ιδιώτες) θα συνεχιστούν κανονικά με την «εξασφάλιση» ότι μέχρι το 2030 το κράτος μας δεν θα χρειαστεί να αποπληρώνει στους δανειστές ποσά άνω του 15% του ΑΕΠ (και από το 2030 και μετά έως το 20% του ΑΕΠ). Πρόκειται για αστειότητα αν αναλογιστούμε ότι αποπληρωμές στους δανειστές ύψους 15% του ΑΕΠ ανέρχονται σε 27 δισ. ετησίως ή στο 55% (!) των φορολογικών εσόδων του κράτους. Με τέτοιους φίλους οι βλοσυροί κατακτητές είναι πράγματι αχρείαστοι!

Ακόμα κι αυτές οι «ευκολίες» πληρωμών, καθώς και το αγκάθινο «μαξιλάρι» των 24 δισ. έρχονται υπό τον όρο της μόνιμης, τριμηνιαίας επιτήρησης από την τρόικα και την εφαρμογή «μεταρρυθμίσεων». Π.χ. όταν η τρόικα θα θέλει να μειώσει κι άλλο τις συντάξεις, θα απαιτεί από την ελληνική κυβέρνηση νέα λιτότητα υπό την απειλή της αναίρεσης των «ευκολιών» πληρωμής.

Υπάρχει, αγαπητέ αναγνώστη, αμφιβολία ότι το μύθευμα περί «καθαρής εξόδου» και «ελάφρυνσης χρέους» δεν είναι παρά το αμπαλάζ του 4ου Μνημονίου της περιόδου 2018-2060;

Επίλογος

Μια κυβέρνηση που τόσο εύκολα επενδύει στον ενορχηστρωμένο αποπροσανατολισμό, με Ζάππεια και γραβάτες ως τα καθρεφτάκια που θα θαμπώσουν τους ιθαγενείς, πολύ γρήγορα έρχεται αντιμέτωπη με την απαξίωσή της.

Πώς μπορεί να πείσει τον ταπεινωμένο πολίτη, μετά από τρία χρόνια «ναι σε όλα» στα φιρμάνια των νεο-κατακτητών μας (τα οποία μάλιστα παρουσιάζει ως «απελευθερωτικά»), ότι η συμφωνία για το Μακεδονικό είναι συμφέρουσα για τη χώρα – ακόμα κι αν είναι;

Διανοείται ο πρωθυπουργός τις σημαντικές υπηρεσίες που προσφέρει στη Δεξιά:

(α) απο-ενοχοποιώντας πλήρως τη στρατηγική Σαμαρά-Βενιζέλου να παρουσιάζουν την επιμήκυνση του χρέους ως αναδιάρθρωση, και

(β) δίνοντας σε μια επόμενη κυβέρνηση Ν.Δ. το δώρο των εύκολων αποπληρωμών για 22 μήνες που αγοράστηκαν με τη μονιμοποίηση της Χρεοδουλοπαροικίας των Ελλήνων στο όνομα της Αριστεράς;

Οι λεπτομέρειες της απόφασης του Eurogroup

Χορηγούνται €15 δισ. από τα δάνεια του 3ου Μνημονίου που δεν χορηγήθηκαν ήδη ώστε να αποπληρώνεται το χρέος τους επόμενους 22 μήνες, εκ των οποίων €3,3 δισ. που θα χρησιμοποιηθούν για να εξαγοραστεί μέρος του χρέους προς το ΔΝΤ.

Δεκαετής αναβολή πληρωμών των τοκοχρεολυσίων του 2ου Μνημονίου της περιόδου 2022-2032 (περί τα €97 δισ.) για μετά το 2032 και έως το 2060 (οπότε θα αποπληρωθούν με τόκο) – υπό τον όρο πως θα κάνουμε ό,τι λέει η τρόικα έως το 2033.

Καμία μείωση επιτοκίων – αν και συμφώνησαν να μην αυξήσουν (!) το επιτόκιο στο μέρος των δανεικών του 2ου Μνημονίου που είχε χρησιμοποιηθεί για την επαναγορά χρέους το 2012/13.

Επιστροφή στην Ελλάδα των κερδών ύψους περίπου €4 δισ. που έβγαλε η ΕΚΤ από την αγορά των ελληνικών ομολόγων επιβάλλοντας στο κράτος μας να πληρώνει 100% της αξίας τους για ομόλογα που αγόραζε κοψοτιμής – και αυτά τα δικά μας χρήματα θα επιστρέφονται σταδιακά εφόσον κάνουμε ό,τι λέει η τρόικα!

*γραμματέας ΜέΡΑ25

June 29, 2018

Varoufakis Says There’s an EU Crisis, Not a Refugee Crisis – Bloomberg

Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis discusses the European Union agreement on migration which he calls “a fudge” and “complete failure.” He speaks on “Bloomberg Surveillance.” (Source: Bloomberg)

June 29th, 2018, 2:05 PM GMT+0300

June 28, 2018

Profiles in Euro-Denial: The thwarted euro reforms & Greece’s permanent debt bondage – Project Syndicate op-ed

ATHENS – Europe’s establishment is luxuriating in two recent announcements that would have been momentous even if they were only partly accurate: The end of Greece’s debt crisis, and a Franco-German accord to redesign the eurozone. Unfortunately, both reports offer fresh proof of the European Union establishment’s remarkable talent for never missing an opportunity to miss an opportunity.

The two announcements did not come in the same week by accident. The Greek debt implosion, back in 2010, was the ugly symptom of the eurozone’s design flaws, which is why it triggered a domino effect across the continent. Greece’s continuing insolvency reflects the deep disagreements within the Franco-German axis concerning eurozone redesign. While three French presidents and the same German chancellor were failing to agree on the institutional changes that would render the eurozone sustainable, Greece was asked to bleed quietly.

For the rest of the article click here….

June 26, 2018

Germany has been wasting its wealth in a manner that prevents the rest of the Eurozone from earning its keep – Video interview for Mission Money, Munich

Er galt als der große Euro-Schreck während seiner Amtszeit als griechischer Finanzminister! Doch waren die Vorwürfe von Politikern und Medien gegen Yanis Varoufakis wirklich gerechtfertigt? Im Interview mit der Mission Money vertritt Varoufakis spannende Positionen. Deutschland dürfe nicht für Pleite-Staaten haften, fordert er. Und außerdem werde Deutschland aus dem Euro austreten, wenn ein ganz bestimmtes Szenario eintritt….außerdem im Gepäck des Griechen: Zahlreiche Ideen, wie man die Euro Zone retten könnte! Das alles in unserem exklusiven Interview!!!! Hinweis: Das Video verfügt über einen Untertitel. Das Video zum Vortrag von Yanis Varoufakis am Ifo-Institut gibt es hier: http://mediathek.cesifo-group.de/play…

June 20, 2018

The Globalising Wall: How Globalisation built walls and divisions. By Y. Varoufakis & D. Stratou, in the Architectural Review

The seeds of our wall were sown in the Balkans, in Yugoslavia and in Greece under Nazi occupation. The harvest began in the streets of our hometown, Athens, in December 1944, yielding a civil war that, although atrocious and globally significant, went virtually unnoticed. But the world began to pay attention when, from the streets of Athens in December 1944, it moved to Berlin, which it partitioned in the following June. The world noticed when it produced two Koreas in that August and leapt to the mountain ranges of Kashmir exactly two years later, as the new fledgling nations of the subcontinent clashed instead of celebrating independence. The world sat up when it flared up in 1948 in the guise of ethnic cleansing and in the midst of all-out war in Palestine and when it made its mark in the streets of Nicosia with a green line – which had been drawn innocuously by a British general in 1956 – before returning in the form of barricades in 1963, two years after the similar soft division in Berlin was transformed (in four short days) into the wall’s most famed incarnation.

When the Troubles erupted in Belfast, and Sunday 30 January 1972 was indelibly bloodied by the British Army, it was there to embellish the pre-existing discontent with ‘peace walls’. Two years later, the barricades along Nicosia’s Green Line, as if in a bid not to be outdone by Berlin or Belfast, also grew into a fully fledged wall.

The Berlin Wall divided the city from 1961 until 1989. Image courtesy of CMSgt Don Sutherland / US DOD

Then, in 1989, while the Berlin Wall was falling, and the world was turning, supposedly, into our global playground, something remarkable happened. Instead of disappearing, these walls grew taller, more impenetrable, longer, stronger, uglier. They invaded disintegrating Yugoslavia, stood tall in the midst of hitherto unified communities in Africa’s Horn (where they claimed grey zones from the rugged tablelands between Ethiopia and Eritrea), turned more insidious and fiendishly complex in Palestine, along the US-Mexico border, in the streets of Baghdad, in Georgia, in Ukraine, in our own cities, their shopping malls and gated pseudo-communities.

We were hit by a great paradox: the more globalisation was meant to give reasons for dismantling the dividing lines, the less powerful the forces working to dismantle them were proving. Deepening divisions, patrolled by increasingly merciless guards, and convoluted architectural techniques, roads, tunnels and fortifications, appeared to us the homage that globalisation was paying to organised misanthropy.

‘We were hit by a great paradox: the more globalisation was meant to give reasons for dismantling the dividing lines, the less powerful the forces working to dismantle them were proving’

In this era of globalised financialisation, divisions were not what they used to be. In times past they simply fended off the enemy, and lightly imprinted the empires’ footprint on the land. Before the ‘discovery’ of the autonomous individual, the ancient polis dreamt of demolishing its walls or, at least, of never having to keep its gates closed. When a son of an ancient Greek city won an Olympics event, the elders ordered the demolition of part of the city walls. Only at times of crisis or degeneracy were the gates ordered shut. Unlike today in North Korea or the southern states of the US, open gates were, then, a symbol of power. Hadrian and the Chinese emperors built great walls, but never with the intention of freezing human movement. They were porous walls, mere symbols of their empires’ self-imposed limits, and a form of early warning system.

Hadrian’s Wall, England, begun AD 122, marked the northern limit of the Roman Empire. Photograph by Steven Fruitsmaak

China’s Great Wall, built over centuries, protected against invasion. Photograph by Jakub Hałun

Fences took on a new role and character at the time European feudalism was running out of steam. Under the strain of the commodification made possible by the new trade routes that linked Southampton with Calcutta, Macao, Japan and the ever-increasing number of colonial outposts strewn all over the globe, the English commons were cut up, fenced off, privatised. So the Enclosures ‘liberated’ the peasants from access to common land and the free labourer was born.

For the first time in history, they became free to choose and, equally, free to lose. Free to rove unimpeded, free to sell their labour, time, body and spirit to whomever, and equally free to starve, enter into desperate contracts with strangers, become a sad part of some productive machine owned by a faceless shareholder. So the age of reason and liberty was ushered in, hot on the trails of the globalisation drive that, on the one hand, fenced the peasants out of their commons at home and, on the other, fenced the slaves in ships to transport them to fenced-off land in the Caribbean and elsewhere, where they were put to work, producing the great surpluses that funded the Industrial Revolution.

From this wealth emerged the castles that Englishmen called home and for whom the fence separating their property from the next one became symbolic of freedom, neighbourliness and subservience under their sovereign. The accumulation of this wealth was the predecessor of the fenced sovereign nation, the gated neighbourhood and the notion of home as one’s castle. It followed the idea that the enemy of autonomy is the ‘other’, either as an individual or, even worse, as a collective, a State, the Inland Revenue …

The Green Line in Nicosia became impassable after the July 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Photograph by Owen Hatherley

The ‘peace walls’ in Belfast separated Nationalist Catholics from Unionist Protestants during the Troubles. Photograph by Danae Stratou

Once the American Revolution had rid the ex-colonies of the transatlantic sovereign as surplus to the requirements of the New World’s drive to accumulate, the US Constitution revelled in the light of reason and liberty while erecting fences to cast in stone the rights of man, defined in terms of freedom from interference; fences that would keep the riff-raff out and, of course, keep the state and the executive at bay; constitutional fences marking the autonomous realm of the liberal bourgeois individual. Border fences, in this manner, became synonymous with modernity in Europe, while in Africa, the Caribbean, parts of the American West, and of course Australia, the fence remained for decades the handmaiden of slavery, expropriation and genocide.

Meanwhile, at the level of theory, for at least 300 years now, reason is defined as the absence of unreason; as if a mighty fence separates the two, with reason maintaining a unique narrative to offer on unreason – courtesy of, on the one hand, economics, and, on the other, psychiatry. In the same manner, freedom is defined almost instinctively as the instrument that demarcates the self and pushes back the interfering others; whether they are foreign armies, migrant workers, one’s own employees, the homeless, even one’s nearest and dearest.

The very notion of the individual that emerged out of Anglo-Saxon capitalism hinges on the idea of ‘well-defined’ spaces within the ‘walls’ that exclude. So our newfangled concept of liberty and progress is contingent on the prior colonisation of ‘alien’ others, while our splendid cosmopolitanism is bought at the price of parochial divides that mindlessly cut the Earth’s face, giving shape to a world map divided, supposedly neatly, into nation-states.

Mitrovica in Kosovo is divided in two with Serbs living in the north, and Albanians in the south, separated by the Ibar river. Photograph by Danae Stratou

Peru’s 3-metre high ‘Wall of Shame’ in Lima divides the wealthy neighbourhood of San Juan de Miraflores from the poor region of Surco. Image courtesy of Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

Modernity, in short, spawned fences, walls and fortifications fit for exciting new roles. They liberated the individual from the tyranny of the ‘other’ and replaced love for one’s neighbour. They gave rise to the proletariat, so hugely expanding the productivity of labour, pacified the colonised, and marked the nation-state’s territory. Modernity’s fence imprisoned the alien, exterminated inconvenient peoples and institutionalised the weird. The fence helped destroy the silly old world and gave a hand to the construction of modern empires that the Romans could never have imagined.

One diary entry from our visit in March 2006 to Juarez, Mexico, while ‘studying’ perhaps the most sinister segment of the US-Mexico border, stands out:

‘It is not just that the walls are getting stronger, rather than more brittle. It is also that they are globalising. The reason seems to be because the importance of deep divisions for stabilising a grossly unstable world order is growing by the day. The raison d’être is the same: it affects different walls in similar ways; they start resembling each other. Both in terms of the social forces that huddle in their shadow but also physically. Aesthetically. A Mitrovica Serb would feel more at home in Nicosia than in Belgrade. An Eritrean residing in Tsorona will feel a sense of familiarity, despite the intense cold, near the Line of Control in alpine Kashmir than she would in Asmara. An Ulster unionist will have no trouble coming to grips with the reality of the ghost city of Famagusta, in Cyprus, whereas he may well feel a stranger in London. A Palestinian from Qalqilia will discover strange bonds with a resident of Juarez, bonds that she may not feel in Cairo. The mere fact that Israeli engineering teams have been employed by the US government to help transplant Sharon’s Wall to California, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas speaks volumes.’

Border Field State Park in San Diego forms a beach border between Tijuana, Mexico, and the US. Photograph by James Reyes

The Western Sahara Wall in Morocco separates Moroccan-occupied and controlled areas from those controlled by the Polisario. Running inside the border between Morocco and Mauritania, it extends as far north as Algeria. Image courtesy of Patrick Hertzog / AFP / Getty Images

Since our travels along the Globalising Wall, globalisation has had its comeuppance. The perverse flow of increasingly unbalanced money and goods that underpinned the myth of a Global Village had produced a wave of unsustainable financial trickery.

The steady stream of European and Asian profits rushing into Wall Street since the 1980s had, by the 2000s, turned into a tsunami of synthetic debts on a whirlpool of financial flows. Bankers were building Midas-like fortunes by inflating oversized bubbles of exotic forms of private debt which, at some point, had surreptitiously acquired the properties of private money. By autumn 2008 these bubbles had burst, causing our generation’s 1929 moment. Together with the financial bubbles, something else broke: the recycling mechanism that held globalisation together –US trade deficits generating global demand for the net exports of Europe, Japan, later China, South-East Asia and so on which, in turn, were paid for by the flood of profits rushing into Wall Street to complete the recycling loop. In 2008, despite energetic money-printing by central banks (and the Chinese authorities’ breathtaking credit and investment spree), this loop broke down. It was only a matter of time before the myth of globalisation would begin to unravel.

‘With globalisation in retreat, militant parochialism filled the space, bolstering the Globalising Wall, which is now running amok, spreading further afield’

American deficits, even after they returned to their pre-2007 levels, could no longer stabilise globalisation. The reason? Socialist largesse for the few, and ruthless market forces for the many, damaged aggregate demand, repressed the entrepreneurs’ sales expectations, restricted investment in good jobs, diminished earnings for the many and, surprise surprise, confirmed the entrepreneurs’ pessimism that underpinned low investment and low demand. Adding more liquidity to that mix made not a scintilla of a difference as the problem was not a dearth of liquidity but the dearth of demand. Abysmal inequality was merely the symptom.

Wall Street, Walmart and walled citizens – those had been globalisation’s symbolic foundations before 2008. Today, all three have become a drag on globalisation. Banks are failing to maintain the capital movements that globalisation used to rely on, as total financial movements are less than a quarter of what they were in early 2007. Walmart, whose ideology of cheapness symbolised the devaluation of global labour and the gutting of traditional local businesses, is itself squeezed by the Amazon model, whose ultimate effect is a further shrinking of overall spending. Meanwhile, the 3D printer, CAD and AI robots promise to de-globalise – and re-localise – production, denying, in the process, countries like the Philippines and Nigeria the advantage that young populations used to bestow on them during the years of globalisation’s rude health.

Tall walls have been built on motorways in Calais to prevent migrants in search of a better existence from accessing lorries bound for England. Image courtesy of Gareth Fuller / PA Archive / PA Images