Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 105

April 19, 2018

April 15, 2018

Το ΜέΡΑ25 στην Λέσβο: Διαπιστώσεις και προτάσεις για τερματισμό του συνειδητού και διαρκούς εγκλήματος που διαπράττει η ΕΕ και η ελληνική κυβέρνηση

Συναντήσαμε υπέροχους ανθρώπους, όπως στο Mosaik, χώρος εκπαίδευσης κι ένταξης των προσφύγων,

και στο λεγόμενο Πίκπα, χώρο φιλοξενίας, παροχής υπηρεσιών φροντίδας και απασχόλησης των προσφύγων

γνωρίζοντας ανθρώπους που κάνουν καταπληκτική δουλειά, δίνοντας όλο τους το Είναι.

Και τέλος η επίσκεψη στη Μόρια, με τη διπλή σειρά συρματοπλεγμάτων και τις σκηνές πάνω στο χώμα έξω από το στρατόπεδο. Ένας χώρος για 2000 άτομα το πολύ που έχει αυτή τη στιγμή περίπου 7000.

Ας περάσουμε λοιπόν στις πολιτικές Διαπιστώσεις από την επίσκεψη στη Μυτιλήνη και στις Προτάσεις του ΜέΡΑ25 για τη διαχείριση του προσφυγικού ζητήματος.

Διαπιστώσεις

Καταρχάς, η συμφωνία ΕΕ-Τουρκίας αποτελεί το ίδιο το πρόβλημα του προσφυγικού και όχι τη λύση του.

Χωρίς περιστροφές, πρόκειται για ένα διαρκές, συνειδητό έγκλημα που διαπράττει η ΕΕ με την συναίνεση και συμμετοχή της ελληνικής κυβέρνησης.

Αποτρέπει στους πρόσφυγες να καταγράφονται ως τέτοιοι και τοποθετεί γραφειοκρατικά εμπόδια στους ίδιους και στους αρωγούς αυτών των ανθρώπων, διατηρώντας τους πρόσφυγες, τις οργανώσεις που δραστηριοποιούνται για αυτούς και τις τοπικές κοινωνίες στην αβεβαιότητα, μην επιτρέποντάς τους τον σχεδιασμό της ένταξης ή μη των ανθρώπων αυτών.

Ταυτόχρονα, αυτό που συμβαίνει είναι ο συνδιασμός της απίστευτης αλληλεγγυής υπέρ των προσφύγων με την απόγνωση των τοπικών κοινωνιών, τόσο των ελλήνων όσο και φυσικά των προσφύγων. Από τη μία μεριά έχουμε την προσχεδιασμένη εξαθλίωση αυτών των ανθρώπων ως μέσο αποτροπής νέων αφίξεων και απο την άλλη έχουμε μια εγκαθιδρυμένη έλλειψη αλληλεγγύης απέναντι στους κατοίκους της Λέσβου, της Χίου, των νησιών που δέχονται τις προσφυγικές ροές, τα οποία έχουν μετατραπεί σε νησιά φυλακές.

Προτάσεις

Οι προτάσεις μας είναι δύο, σε ελληνικό, πρακτικό επίπεδο και σε ελληνοευρωπαϊκό επίπεδο.

Σε ελληνικό επίπεδο προτείνουμε πανελλήνιο δίκτυο αλληλεγγύης υπέρ των προσφύγων, με τη δημιουργία ανθρώπινων υποδομών σε όλη την επικράτεια για την αξιοπρεπή φιλοξενία και διαβίωση των προσφύγων, για την σωστή υποδοχή αυτών των 50.000 ανθρώπων που ζητούν άσυλο.

Για την στάση της ελληνικής κυβέρνησης σε ευρωπαϊκό επίπεδο προτείνουμε Κυβερνητική Ανυπακοή. Η ελληνική κυβέρνηση δεν θα πρεπε να έχει υπογράψει ποτέ τη συμφωνία ΕΕ-Τουρκίας. Τώρα απαιτείται η αφαίρεση της υπογραφής μας από αυτή τη κατάπτυση συμφωνία, κυβερνησητική ανυπακοή απέναντι σε μια κατ’επίφαση μεταναστευτική πολιτική που σκοτώνει την ίδια τη ψυχή της Ευρώπης και εξευτελίζει την έννοια του ευρωπαϊκού πολιτισμού. Βέτο λοιπόν της ελληνικής κυβέρνησης σε αυτή τη συμφωνία και φυσικά βέτο σε κάθε μιλιταριστική επίθεση που αναπαράγει το τραγικό προσφυγικό πρόβλημα.

On MeRA25, on DiEM25’s transnational European Parliament electoral campaign, on our allies in France & around Europe – interviewed by Fabien Perrier for regards.fr (English with French subtitles)

Sur son nouveau parti MeRA25

« Le but de MeRA25, c’est de convaincre des citoyens paralysés et découragés qu’une alternative existe. »

« L’alternative peut à la fois être modérée, réaliste et radicale. »

« C’est très intéressant d’occuper les places et de débattre, de voter et de discuter de tout de manière complètement démocratique et ouverte, mais ce n’est pas assez parce que le problème c’est qu’au bout d’un moment, les gens partent. »

« On a besoin d’organisations, de structures qui s’emparent de ces forums pour élaborer des propositions politiques qui puissent contaminer les imaginations de ceux qui ne sont pas sur ces places. »

Sur les élections européennes

« Notre stratégie est basée sur la désobéissance constructive. »

« Nous allons prendre la « Bastille » du Parlement, qu’il soit en Grèce, en France, à Bruxelles ou à Strasbourg parce qu’il n’y a pas d’autres moyens pour changer la vie des gens. »

« Les gens ont été abandonnés, ils sont paralysés, beaucoup ne votent pas. »

« Aucun des gouvernements européens n’a été réellement élu par une majorité convaincue et enthousiaste. »

Sur la situation politique en Grèce

« Ceux qui sont allés voter n’avaient pas d’autres alternatives que de voter pour l’enfer ou le moins pire. »

« Nous vivons une grande dépression : la spirale de la déflation de la dette est sans fin. »

« J’ai bien peur que Syriza n’existe plus aujourd’hui. »

« Syriza s’est rendue obsolète en tant que force progressiste. »

Sur la politique européenne

« Nous avons besoin d’un plan d’investissements massifs en faveur de la transition énergétique de 5 milliards d’euros par an pendant 5 an. Et ça, on peut le faire à traités constants. »

« On n’aime pas cette Union européenne mais sa destruction ne fera qu’alimenter le discours de Le Pen. »

« J’aurais aimé que la gauche européenne fasse son travail mais ça n’a pas été le cas. »

Sur la « gauche » européenne

« Les nationalistes ont une histoire cohérente avec leurs solutions : le Brexit, le Grexit, le Frexit, l’Italexit mais aussi construire de hauts murs autour du pays, virer les étrangers (…). Les seuls à ne pas avoir d’histoire cohérente c’est la gauche. »

« La partie européenne de la gauche à laquelle appartient Tsipras fait tout ce que la Troïka lui dit de faire en affirmant que c’est un succès. »

« Les partis européens de gauche n’ont pas d’histoire cohérente à présenter en Europe. »

Sur ses relations avec la gauche française

« En France, on est en discussion avec le Parti communiste français, avec les Verts, avec Benoît Hamon. »

« Les divisions de la gauche sont une source de problèmes pour nous. »

Sur Jean-Luc Mélenchon

« Je travaillerais volontiers avec Jean-Luc Mélenchon comme avec n’importe quel progressiste européen : le point de désaccord, c’est notre stratégie et notre tactique. »

« Nous avons besoin d’un plan A pour l’Europe et Jean-Luc Mélenchon se concentre sur le plan B. »

« Il faut s’unir autour d’un internationalisme de gauche. »

Sur Emmanuel Macron

« Nous sommes d’accord avec Emmanuel Macron sur ce qui détruit l’Europe : le système monétaire et le manque de démocratie. »

« Nous divergeons avec Emmanuel Macron sur ce qui doit être fait en Europe. »

« Emmanuel Macron s’est entouré de figures de l’establishment. »

« En optant pour une politique néolibérale Emmanuel Macron est fini. »

At home with the Financial Times – by Bruce Clark, 11 APR 2018

“I am besotted with technology,” he declares, sitting in a relatively modest Athens apartment where there are no sepia photographs, antique tables or anything else that speaks obviously of the past. He loves being able to Skype his 13-year-old daughter, who lives with her mother in Sydney, every morning, and he co-ordinates a pan-European political movement, DiEM25, with tele-conferences every few days.

As the moment demands, the things he says in eloquent, faintly accented English can be conciliatory or harsh. During his six stormy months as Greek finance minister, which ended with a bang in summer 2015, he was notorious for caustic soundbites. Whether or not they liked his policies, people enjoyed his description of Greece’s “fiscal waterboarding” by its creditors, and his comparison of the eurozone to Hotel California, where it’s easier to check in than to leave.

There are those, in both Athens and Brussels, who say that he bears a share of responsibility for the costly crisis in which Greeks faced sudden curbs on their cash movements, a disrupted tourist season and a near-crash out of the euro. Today, he is adamant that a fight between Greece and its creditors was inevitable. Without claiming infallibility, he insists: “I stand by the basic strategy I tried to follow, and in fact I was too lenient with the troika [of creditors].”

Varoufakis has at times been branded a high-living radical. During his time as finance minister, he lived in a desirable part of Athens near the Acropolis, courtesy of his parents-in-law. These days the base for his work is a fourth-floor apartment in a part of downtown Athens that is neither smart nor poor. The thunderous traffic and shabby stadium of Alexandras Avenue, marking the northern edge of the city centre, are only a few minutes away, but somehow his street is a quiet haven.

That is fortunate, because this rented expanse of parquet floor is only just big enough for the characters, human and otherwise, whose lives intertwine in it. Although she appears only briefly, the first impression on visiting the flat is of the fire that still crackles between Varoufakis and his wife Danae Stratou, an installation artist, photographer and art professor. Most of the objects in view are startling, experimental creations by Stratou or her pupils or friends. Having worked as an academic in England, as well as Sydney and Austin, Texas, Varoufakis doesn’t have many permanent possessions except books.

There is another house, too, on the nearby island of Aegina, on a hillside where Stratou’s father, an industrialist, parcelled out a piece of land between his daughters. In Varoufakis’s latest book, presented as an attempt to explain economic history to his daughter, there are idyllic descriptions of their summer meetings on the island. “I make sure I don’t have any work with me,” he says, “we go for walks, we go out on a boat, that’s where we have the opportunity for conversations.”

Sentimentally speaking, he says, “our real home is in Aegina”, but the majority of the couple’s time is spent amid the Athenian fumes, and that also has compensations. He enjoys living so close to Loras Bar, “a fantastic hang-out where I used to go as a young man,” which still sells good cocktails. They both have offices elsewhere in the city, but a lot of their work is done in the flat, at desks in adjoining rooms. Varoufakis launched the Greek branch of DiEM25 in March, vowing “constructive disobedience” if Euro-crats tried to stop a future Athens government from reflating the economy by cutting taxes.

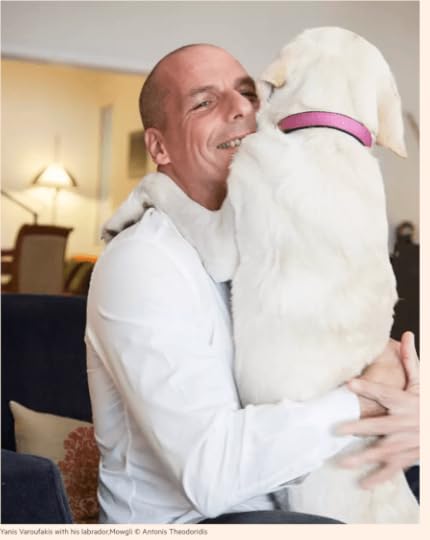

Across Europe, the movement’s aim is what Varoufakis calls a genuinely federal, and more democratic, EU. With supporters including Brian Eno, Julian Assange and Slavoj Zizek, it favours a green investment programme and generosity to refugees. It will field a list of candidates at next year’s European Parliament elections. “In some countries we will work with existing parties; in others we will start new ones,” explains Varoufakis, with the self-assurance of a man who can make a Herculean task sound manageable. Hectic as their lives are, Varoufakis and Stratou make time for a relaxed breakfast, and compete to spoil Mowgli, a lolloping white-and-fawn Labrador who is less than a year old. Next to Varoufakis’s piled-high desk is a cosy space where “we have our morning coffee, with the dog going from one of us to the other, having apple from me and yoghurt from Danae . . . those Labradors never stop eating.”

Across Europe, the movement’s aim is what Varoufakis calls a genuinely federal, and more democratic, EU. With supporters including Brian Eno, Julian Assange and Slavoj Zizek, it favours a green investment programme and generosity to refugees. It will field a list of candidates at next year’s European Parliament elections. “In some countries we will work with existing parties; in others we will start new ones,” explains Varoufakis, with the self-assurance of a man who can make a Herculean task sound manageable. Hectic as their lives are, Varoufakis and Stratou make time for a relaxed breakfast, and compete to spoil Mowgli, a lolloping white-and-fawn Labrador who is less than a year old. Next to Varoufakis’s piled-high desk is a cosy space where “we have our morning coffee, with the dog going from one of us to the other, having apple from me and yoghurt from Danae . . . those Labradors never stop eating.”

At the time of our visit, Mowgli is being fussed over because of a leg wound; as soon as this heals, his master and mistress will resume their daily dog walks over Mount Lycabettus, a stony outcrop that relieves the city’s concrete monotony. In the evening, Stratou’s 23-year-old son Nikos, who lives with them, often takes the hound for another lengthy stroll. “Those two boys, I don’t know what they get up to,” Varoufakis mutters with a grin.

At the time of our visit, Mowgli is being fussed over because of a leg wound; as soon as this heals, his master and mistress will resume their daily dog walks over Mount Lycabettus, a stony outcrop that relieves the city’s concrete monotony. In the evening, Stratou’s 23-year-old son Nikos, who lives with them, often takes the hound for another lengthy stroll. “Those two boys, I don’t know what they get up to,” Varoufakis mutters with a grin.

Looming over the apartment’s main sitting area, there is a large memento of a more rigorous mountain hike which Varoufakis and Stratou undertook a dozen years ago to seal their relationship. It is a photograph of a rice field on the front line of Kashmir’s war zone. As he recalls, within days of their decision to end their previous marriages and share their lives, he joined Stratou on a round-the-world tour. Her aim was to capture the nodal points of regions divided by conflict, ranging from Belfast to the Horn of Africa. He enjoys reminiscing about their Kashmiri scrapes. To ascend a towering peak, they persuaded a local man to crank up an ancient ski lift, but they had to scramble down on foot and Varoufakis nearly tumbled to his death. “I looked down and my feet were dangling from a cliff, and it was a 100-metre drop . . . ”

In the midst of the sitting space is a large table created by Stratou: a glass surface covering a carefully constructed metal labyrinth. Since childhood, Varoufakis explains, his wife has been intrigued by spirals. He, too, has long been fascinated with the story of the Minotaur, who waits at the heart of an underground maze to devour his annual quota of youths and maidens: “a dirty secret in the guts of the palace”, whose preservation is necessary to keep the system going. It is a useful metaphor, he argues, for Wall Street, which demands “tribute” from the surpluses of other capitalist countries.

Varoufakis loves talking about ancient Greece, in whose history and literature he was drilled at one of the city’s elite private day schools. As he reminisces about his father, still thriving in his mid-90s, he reveals an unexpected fact. It is common knowledge that, having endured prison as a suspected communist in the late 1940s, George Varoufakis became the right-hand person of a steel magnate. Less well known is his contribution to archaeology. Varoufakis senior pinpointed how the builders of the Parthenon used an iron-zinc alloy to stabilise the marble columns; they knew far more than some of the hapless would-be conservators of modern times. Varoufakis relishes his father’s discovery. “What a fantastic thing to find! The ancient iron rods lasted 2,000 years whereas the new ones, made of Birmingham steel, had rusted within two years.”

Varoufakis loves talking about ancient Greece, in whose history and literature he was drilled at one of the city’s elite private day schools. As he reminisces about his father, still thriving in his mid-90s, he reveals an unexpected fact. It is common knowledge that, having endured prison as a suspected communist in the late 1940s, George Varoufakis became the right-hand person of a steel magnate. Less well known is his contribution to archaeology. Varoufakis senior pinpointed how the builders of the Parthenon used an iron-zinc alloy to stabilise the marble columns; they knew far more than some of the hapless would-be conservators of modern times. Varoufakis relishes his father’s discovery. “What a fantastic thing to find! The ancient iron rods lasted 2,000 years whereas the new ones, made of Birmingham steel, had rusted within two years.”

Varoufakis shares his father’s penchant for delving into the genius of the past and asking how a similar spirit might guide the future. He describes himself as a libertarian follower of Karl Marx, and he thinks the German philosopher would be fascinated by today’s technology and the way it could change society. He realised this, he says, when acting as a consultant on economics for Valve, a Seattle-based computer games firm, in 2012. He observed with fascination how a new capitalism was emerging, with democratic decision-making and spontaneous team-building.

“Because there was no hierarchy, everybody did their own thing. And you had to walk around and meet people and say ‘Will you tell me what you do, so I can see if I can work with you?’ ” Agree with him or not, Varoufakis is a stimulating interlocutor, switching fluently between topics, countries and aeons of history. Among the handful of objects that recall his peripatetic life are his teenage LPs (he liked Roxy Music) and a small table made of Australian tropical wood. Yet he has found ways of making up for this deficit. His home life reveals an intense, durable attachment to intangible things, especially relationships — whether human or canine, long-distance or near-at-hand.

———–

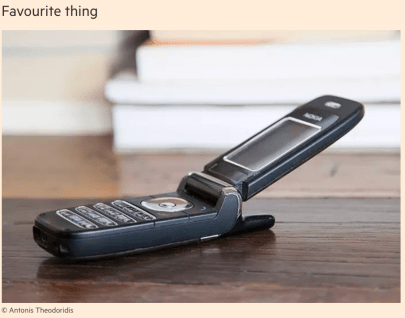

FAVOURITE THING: A once-snazzy mobile phone is the unlikely keepsake that Varoufakis uses to remember his mother Eleni, who died 10 years ago. They had a close but demanding relationship, based on tough love. He was an exasperating child, who would act lazy and then cram at the last minute, getting excellent results. So she bargained with him, setting him a programme of Greek and world literature that he had to read by the age of 13. It was understood that if he obeyed, he would be allowed more freedom. “I could get on my bike and disappear for hours, as long as I read my Dostoyevsky.” Despite her conservative family roots, Varoufakis’s mother converged politically with his father as a supporter of PASOK, the Greek Socialist movement that swept to power in 1981. Eleni became prominent in PASOK’s feminist wing, and in local government. She was a moderniser, not a sentimentalist, and her son was proud of that.

FAVOURITE THING: A once-snazzy mobile phone is the unlikely keepsake that Varoufakis uses to remember his mother Eleni, who died 10 years ago. They had a close but demanding relationship, based on tough love. He was an exasperating child, who would act lazy and then cram at the last minute, getting excellent results. So she bargained with him, setting him a programme of Greek and world literature that he had to read by the age of 13. It was understood that if he obeyed, he would be allowed more freedom. “I could get on my bike and disappear for hours, as long as I read my Dostoyevsky.” Despite her conservative family roots, Varoufakis’s mother converged politically with his father as a supporter of PASOK, the Greek Socialist movement that swept to power in 1981. Eleni became prominent in PASOK’s feminist wing, and in local government. She was a moderniser, not a sentimentalist, and her son was proud of that.

FOR THE SITE OF THE FINANCIAL TIMES CLICK HERE

Our new European party can unite Britain’s feuding Remainers and Leavers – by Yanis Varoufakis, Benoit Hamon (Generation-s), Luigi de Magistris (mayor of Naples), Rasmus Nordqvist (Alternativet); Rui Tavares, former MEP from Portugal (Livre); & Agnieszka D

The European Union and the UK are on a cliff edge. Left to its Brussels-based establishment, the EU continues to turn against most of its people who, as a consequence, turn against Brussels. Meanwhile, facing an immensely damaging Brexit, the people of Britain are becoming despondent. This is the moment for British and continental progressives to forge a close alliance.

Next year’s European parliament elections will not, sadly, be contested in Britain. And they are not capable of toppling the current EU regime, since the European parliament has no such authority. Nevertheless, this vote involving the electorates of 27 member states offers us a splendid opportunity to have the debate that we have been denied so far across Europe. Britain’s people – indeed, its MPs – never got a chance to debate the relationship they want the UK to have with the EU post-Brexit. Similarly, the peoples of mainland Europe have never had an opportunity to debate the clear and urgent changes that the EU needs to implement if it is to become a force for good.

We think that we have a duty to spearhead these debates in both Britain and on the continent, using the European parliament elections as our focal point. We also think that this is an opportunity to heal the rift between progressive remainers and leavers in Britain, as well as between continental progressives who have given up on the EU and those who disagree that the EU’s disintegration is the right agenda to take to Europeans.

To this end, we have decided not only to contest European elections in May 2019 on the strength of a single manifesto, mapping out a clear path to a democratic, ecological, egalitarian and ambitious Europe, but also to campaign in Britain. Naturally, we intend to do so in association with our natural allies in the country: Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party, our colleague Caroline Lucas, leader of the Green party, and other progressives in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Why campaign in the UK? To what effect? We believe strongly that a common crisis is undermining our societies and our democracies. As with climate change or tax avoidance, solutions cannot emerge either from the British establishment or from Europe’s pseudo-technocracy. “More of this Europe” won’t do the trick, nor will re-nationalisation of policy. What we need, in the UK and in the EU, is a combined municipal, national and pan-European strategy to tackle our common crises: private and public debt; the low levels of investment that contribute to precariousness, unemployment and poverty; environmental protection; solidarity with refugees etc.

As Europeans, British, French, Greeks, Italians, Poles and so on, we need to wrest democratic control over both our national and local governments and, vitally, over the European Union’s institutions. To do so, we need a realistic but radical pan-European plan involving all countries, regardless of whether they are in the European Union, in the eurozone, in the European Economic Area or none of the above.

A month ago, in Naples, we joined forces with political parties from Italy, Poland, Denmark and Portugal to agree to contest the May 2019 European elections on the strength of a single manifesto mapping out a clear path to a democratic, ecological, egalitarian and ambitious Europe. Our programme is founded on two pillars: a pan-European economic policy framework amounting to a green New Deal. And a commitment to launch a grassroots assembly process, from villages to cities and high schools across Europe, culminating in a constitutional assembly which, by 2025, will draft the new foundation texts of a democratic Europe.

Both these pillars are non-exclusive to the European Union and can, therefore, become part of a progressive agenda for a post-Brexit UK. Would it not be splendid if the people of the UK and of continental Europe demonstrated their contempt for the anti-democratic process conducted in the name of Brexit, by erecting an effective alliance upon these pillars? Would this not be the ideal way to overcome the division between remainers and leavers in the UK, as well as between those of us living in the EU and those outside its formal borders? Is the idea of a constitutional assembly process (which interrogates, in parallel, the UK constitution and our awful EU treaties) not a terribly invigorating prospect?

This is why we plan to include UK cities and towns on our campaign trail leading up to the May 2019 European parliament elections.

Yanis Varoufakis is the former finance minister of Greece and leader of MeRA25, a new Greek party inaugurated by DiEM25 -the Democracy in Europe Movement. Benoît Hamon was the Socialist party candidate in the French presidential elections of 2017. Luigi de Magistris is the mayor of Naples (DemA). Rasmus Nordqvist is a Danish MP (Alternativet). Rui Tavares, is a former MEP from Portugal (Livre); and Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk, leader of the Polish progressive party Razem

Click here for The Guardian’s site.

April 14, 2018

Να απελευθερωθεί ο Τζούλιαν τώρα! Βίντεο του ΜέΡΑ25

Η απομόνωση του Τζούλιαν Ασάνζ πρέπει να σταματήσει τώρα. Υπόγραψε το ψήφισμα.

Free Julian now! A MeRA25 video message in support of the petition to restore Assange’s access to the outside world

End Assange’s isolation now. Sign the petition!

April 13, 2018

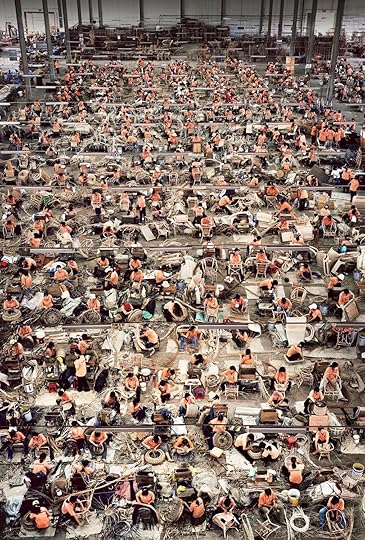

Internationalism vs Globalisation: Why progressives across Europe and beyond must forge a common internationalist movement – Talk at the Royal Festival Hall, accompanied by Andreas Gursky’s images and Danae Stratou’s ‘The Globalising Wall), 9 APR 2018

Ladies and gentlemen, there is bad news; there is worse news; and there is hope. The bad news is that globalisation has triumphed. The worse news is that it is in retreat – albeit not in ways that those of us who opposed its triumphant march can celebrate. And finally there is hope – hope that there is an alternative to both globalisation’s destructiveness and to the parochialism that is now trumping globalisation’s oeuvre in Trump’s America, in Brexit Britain, indeed everywhere.

And the name of this hope? Of the potential scourge of both globalisation and its xenophobic nemesis? Its name is… internationalism – an old friend from a bygone era that fell by the wayside as the Left collapsed into a pile in the late 1980s, weighed down by our own folly. It was that stupendous defeat that allowed the idea of a borderless, cosmopolitan world to be replaced by the dystopic vision of a planet in which digital money and containers stuffed with our artefacts move unimpeded and at incredible speeds while, at the very same time, people are fenced in – surrounded by a new type of impenetrable, brutal, unyielding, murderous wall.

Globalised capital’s triumph, and the fizzling out of the anti-globalisation movement, was perhaps epitomised by the manner in which the establishment succeeded in demonstrating the irrelevance of our polulous global demonstrations against invading Iraq – by invading… Iraq! And by subsequently silencing all opposition to their madness.

Fifteen years later, the globalising capitalist order is getting its comeuppance. And it does so in a manner reflecting a universal irony: It is falling prey to its own oeuvre – to globalising capital’s own, unique capacity to undermine itself – bringing to mind the inimitable lines from the Communist Manifesto of “…a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange” that it resembles “the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

It is a form of universal irony, is it not? The most audacious of globalised capitalist accumulation processes have begat labour saving technological change which now underpins jobless de-globalisation all over the planet. In this reading, Donald Trump is merely symptomatic of robotic and financial technologies infesting a social order unable to make good use of them. Which of course, as always, is a double edged sword; a sword that can cut both ways; either embodying our nightmares or, at long last, fulfilling our humanist dreams.

From where I stand, and this will be my argument tonight, only an ambitious new internationalism can help reinvigorate the spirit of humanism at a planetary scale.

Humanity has been globalising ever since our ancestors left Africa, the earliest economic migrants on record. This process was supercharged by capitalism. To quote again from the Communist Manifesto, using its “heavy artillery” – the “cheap prices of commodities” – it has been battering “down all Chinese walls”, “constantly expanding market for its products”, leading to the extraordinary substitution of “…intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations” for “the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency.”

None of this is new. So, why did the need for a term like ‘globalisation’ not arise until 1991? The answer is that, around 1991, something genuinely new happened: A world capitalist economic system emerged whose growth and stability relied on increasingly unbalanced trade and money movements – a deliciously contradictory system we have come to know as globalisation – a system that eventually yielded our generation’s 1929 moment in 2008 before, very recently, going into retreat that spawned new forms of parochialism and xenophobia.

But let’s take a closer look at the origins and incongruities of this remarkable species of global economy: of a fully financialised, globalising, capitalism that could only remain stable as long as it was growing increasingly imbalanced. Contradictions have never come more turbocharged than this!

Let’s begin at the beginning: In 1944, as the war was ending, the New Deal administration in Washington understood that the only way to avoid the Great Depression’s return was to ensure that foreigners (Europeans and the Japanese to be precise) would be buying the new washing machines, cars, television sets and passenger jets that American industry would switch to once it ceased producing military hardware for the war effort. But how could the devastated Europeans and Japanese afford American goodies? The only way was to transfer to them a portion of American economic surpluses. A form of ingenious surplus or wealth recycling was instituted. Its purpose was not philanthropy but a penchant to generate foreign demand for American net exports. The Marshall Plan was but one example of this.

Thus began the project of dollarising Europe, of founding the European Union as a cartel of heavy industry, and of building up Japan within the context of a global currency union based on the American dollar. This new system, also known as the Bretton Woods system, succeeded in equilibrating a global system featuring fixed exchange rates, almost constant interest rates, and… boring banks operating under severe restrictions. It was a dazzling design that brought us capitalism’s golden age of low unemployment and inflation, high growth, and impressively diminished inequality.

Alas, by the late 1960s it was dead in the water. Why? Because the United States lost its surpluses and slipped into a burgeoning trade deficit and an enormous federal budget deficit, rendering America no longer able to stabilise the global system it had fashioned. Never too slow to confront reality, Washington killed off its finest creation: On 15th August 1971 President Richard Nixon announced the ejection of Europe and Japan from the dollar zone. Unnoticed by almost everyone, what we now call globalisation was born on that summer day.

Nixon’s decision was founded on the refreshing lack of deficit-phobia that is typical of American policy-makers. He was simply unwilling to rein in deficits by imposing austerity. Why? Because austerity would have done more to shrink the America’s capacity to project hegemonic power around the world than to shrink its deficits. So, instead, Washington counter-intuitively stepped on the accelerator to boost those deficits! The result was that the United States functioned like a giant vacuum cleaner, sucking in massive net exports from Germany, Japan and, later, China.

SALERNO 1991

However, what gave that era (1980-2008) its energy and character was the manner in which America paid for these expanding deficits: by means of a tsunami of other people’s money – European, Japanese and later Chinese net exporters’ profits rushing into Wall Street in search of higher returns.

But for Wall Street bankers to act as this magnet of other people’s capital, Wall Street had to be unshackled from its New Deal and Bretton Woods era fetters. Bank de-regulation was part of a Faustian bargain: The bankers would syphon into America European and Asian profits to cover America’s trade and government deficits. And the American government would allow them to go berserk. That was the social contract, the Faustian bargain, behind globalisation.

There was also a second condition for Europe’s and Asia’s capital to want to flow into America: the cheapening of American labour that was essential to push Wall Street’s capital returns above those of Frankfurt and Tokyo, where competitiveness was based instead on enhancements to productivity.

FRANKFURT 2007

TOKYO 1990

But how could Americans continue to buy other people’s stuff when their wages shrunk? With escalating credit, provided by Wall Street, is the answer. You may recognise a similar history here in Britain, ladies and gentlemen. The United Kingdom, having de-industrialised under Mrs Thatcher, bet the house on attaching the City to Wall Street and turning the British economy into a simulacrum of America, without of course the capacity to regulate globalised capitalism: Private debt, financialised houses and the City became the only shows in this town, in London, the only town that matters to this country’s economic oligarchy.

Every new regime needs its own ideology, its religion. Neoliberalism was rescued from the loony fringes of political economics to play that role in the 1970s. It had as much to do with really existing capitalism as Marxism had to do with Brezhnev’s Soviet Union: Nothing whatsoever! Neoliberal economists were never central in policy making. But they did provide the sermons that steadied the hand of politicians repealing New Deal era protections for workers and society at large from the motivated abuses of Wall Street bankers and predators such as Wal-Mart who turned cheapened goods and cheapened labour into the West’s new mantra.

Before long, the Soviet Union and its satellites collapsed. In Eastern Europe, the new-old rulers were keen for a piece of the action. Meanwhile, in Beijing, the Chinese Communist Party was determined to survive by staging a managed insertion of China’s workers into capitalism’s proletariat. Financial capital’s inexorable march and two billion workers entering the global labour market ensured a spectacular redistribution of income and wealth.

NHO TRANG 2004

While billions of people were lifted from abject poverty in Asia, large numbers of Western workers were discarded, their voices drowned out by the cacophony of money-making in financialisation’s epicentres.

We now all lived in a global village, we were told. History had ended. The success or failure of each one of us, of our community, our nation now depended entirely on how cheap we and our products had become. It was a compelling narrative. Distances were shrinking through digitisation, supply chains lengthened hugely, global intercourse was exciting and it was revolutionary. Our May Day events, …

MAYDAY

…anti-globalisation gatherings, the World Social Forum – they all seemed out of place – the reactions of recalcitrants who refused to accept that we lived in a brave new paradigm.

BUT, one reality refused to concur with the global village narrative. A wall. Not a new wall. But one made up of many older walls that began to unite, to globalise, as if in order to expose globalisation for what it truly was: a process of deepening divisions, of dangerous imbalances, of a shocking disequilibrium presenting itself as harmony, as congruence, as… equilibrium.

The seeds of the wall I am talking about were sown in the Balkans, under the Nazi occupation, in Yugoslavia and in Greece. The harvest began in the streets of my hometown, Athens, in December 1944; yielding a Civil War of an awfulness and global significance that went almost wholly unnoticed. The world began to pay attention:

when, from the streets of Athens in December 1944, it moved to Berlin, which it partitioned in the following June

when it produced two Koreas in that August

leapfrogged to the mountain ranges of Kashmir exactly two years later, on 15th August 1947, as the new fledgling nations of the subcontinent, instead of celebrating independence, clashed

when it flared up in 1948 in the guise of ethnic cleansing and in the midst of all-out-war in Palestine

when it made its mark in the streets of Nicosia with a green line, drawn innocuously by a British general in 1956, before returning in the form of barricades in 1963, two years after the similar soft division in Berlin was transformed, within four short days, into the Wall’s most famed incarnation.

When the Troubles broke out in Belfast, and Sunday 30th January 1972 was indelibly bloodied by the British Army, it was there to embellish the pre-existing discontent with euphemistically called Peace Walls. Two years later, in 1974, the barricades along Nicosia’s Green Line, as if in a bid not to be outdone by Berlin or Belfast, grew also into a fully-fledged wall.

Then, in 1989, while the Berlin Wall was falling, and the world was turning, supposedly, into our Global Playground, something remarkable happened: Instead of these walls disappearing, they divided, multiplied and grew stronger, uglier. They invaded disintegrating Yugoslavia, stood tall in the midst of hitherto unified communities in Africa’s Horn, where they claimed grey zones from the rugged tablelands between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and grew more insidious in Palestine, the US-Mexico border, in the streets of Bagdad, in Georgia, in the Ukraine, in our own cities, their shopping malls and gated pseudo-communities; the list goes on.

In 2005, my partner, artist Danae Stratou, announced that her next installation would consist of pairs of photographs, one for each of seven harsh divisions from around the world. She would stand right on the division, in Palestine, in Kashmir, on the US-Mexico border… photograph each side… print the photos in large transparencies and then construct a corridor that the viewer would walk through made of these seven pairs of large hanging photographs – as if walking on a division line taking the viewer from Cyprus to Palestine to Kasmir to the beach dividing San Diego on the one side and Tijuana on the other – a path meant, potentially, to unify, to heal, the division.

For a year we travelled together to these divisions which globalisation, theoretically, was making obsolete but, in practice, it was reinforcing. During those travels a Great Paradox hit me: The more globalisation was meant to develop reasons for dismantling the dividing lines, the less powerful the forces working to dismantle them were proving. Deepening divisions, patrolled by increasingly merciless guards, appeared to us the homage that globalisation was paying to organised misanthropy.

During our travels, our faces pushed up against those hideous fences, the reality of globalisation hit me more powerfully than ever. Here is something that I put down in my diary in March 2006, in Juarez – a stone’s throw from El Paso:

“It is not just that the walls are getting stronger, rather than more brittle. It is also that they are globalising. The reason is, I think, because the importance of deep divisions for stabilising a grossly unstable world order is growing by the day. The raison d’ être is the same. It affects different Walls in similar ways. They start resembling each other. Both in terms of the social forces that huddle in their shadow but also physically. Aesthetically. A Mitrovica Serb would feel more at home in Nicosia than in Belgrade. An Eritrean residing in Tsorona will feel a sense of familiarity, despite the intense cold, near the Line of Control in alpine Kashmir than she would in Asmara. An Ulster unionist will have no trouble coming to grips with the reality of the ghost city of Famagusta, in Cyprus, whereas he may well feel a stranger in London. A Palestinian from Qalqilia will discover strange bonds with a resident of Juarez; bonds that she may not feel in Cairo. The mere fact that Israeli engineering teams have been employed by the US government to help transplant Sharon’s Wall to California, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas speaks volumes.”

After our travels, Danae completed and exhibited her installation, entitled ‘CUT – 7 dividing lines’. Soon after, based on these scribblings of mine and the idea that the divisions were but a single wall that was globalising – the nasty underbelly of the fictitious Global Village – she put together a video that featured as part of another installation entitled ‘The Globalising Wall’. Here it is, with a soundtrack comprising actual recordings Danae made in situ plus string music by Ada Pitsou.

That was in 2006. Two years before globalisation was to be mortally wounded by our generation’s 1929. John Maynard Keynes once wrote: “Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation.” Which is precisely what had happened by 2007: On the whirlpool of the tsunami of European and Asian profits rushing into Wall Street, bankers built oversized bubbles of exotic forms of private debt which, at some point, had surreptitiously acquired the properties of private money.

When these bubbles burst in 2008, the recycling loop maintaining globalisation was broken despite energetic money printing by central banks and the Chinese authorities’ breath-taking credit and investment spree. American deficits, even after they returned to their pre-2007 levels, could no longer stabilise globalisation. The reason? Socialist largesse for the few and ruthless market forces for the many damaged aggregate demand, repressed the entrepreneurs’ sales expectations, restricted investment in high quality jobs, diminished earnings for the many and, surprise-surprise, confirmed the entrepreneurs’ pessimism that underpinned low investment and low demand. Adding more liquidity to that mix made not a scintilla of a difference as the problem was not a dearth of liquidity but a dearth of demand.

Wall Street, Wal Mart and Walled citizens. Those were globalisation’s symbolic foundations. Today, all three have become a drag on globalisation:

Banks are failing to maintain the capital movements that globalisation used to reply upon, as total financial movements across the globe are less than one fourth of what they were in early 2007.

Wal Mart, whose ideology of cheapness symbolised the devaluation of labour and the gutting of traditional local businesses, is itself squeezed by the Amazon model whose ultimate effect is a further shrinking of overall spending.

And the walls that were the nasty underbelly of the ‘global village’ – the US-Mexico border; the European Union’s contemptible policy of strategically using the Mediterranean as a watery tomb for tens if not hundreds of thousands – our Globalising Wall is in the news more than ever before and a source of political discontent, illegitimacy, misanthropy.

AMAZON

Looking at the world from an Archimedean distance, globalization has been caught in a steel trap of its making. Let me put it bluntly: Its crisis is due to too much money in the wrong hands. Humanity’s accumulated savings per capita are at the highest level in history. However, our investment levels (especially in the things that humanity needs, like green energy) are, in comparison, at an all-time low.

In the United States, massive sums are accumulating in the accounts of companies and persons that have no use for them; while those without prospects or good jobs are immersed in mountains of debt. In China, savings approaching half of all income sit side-by-side with the largest credit bubble imaginable. Europe is even worse: There are countries with gigantic trade surpluses but nowhere to invest them domestically (e.g. Germany and the Netherlands); countries with deficits and no capacity to invest in badly needed labour and capital (e.g. Italy, Spain, Greece); and, to boot, a European Union unable to mediate between the two types of countries due to the lack of federal-like institutions that could do this.

And as if these discontents were not enough, there is also the rise of the machines. Almost half of the professions in Europe and North America will be susceptible to automation by 2020. Robots require few, highly paid, designers and operators but may replace millions. This generates labour shortages and labour gluts in the same city, at the same time. Western middle classes are in for another hollowing out, wage inequality is about to rise again in the richer countries, while developing countries will soon realize that having large young populations offers no respite from poverty: With robots getting smarter and cheaper, de-globalisation takes over and countries like Nigeria, the Philippines and South Africa will bear the brunt of re-localisation – especially so given the evolution of 3D printing.

Is it any wonder that, in view of globalisation’s secular crisis, parochialism, nativism and xenophobia are rearing their ugly head everywhere? Rather than focusing on the role of Facebook, Vladimir Putin or some unexplained new-fangled fear of the ‘foreigner’, the so-called liberal establishment (which by the way is neither liberal nor particularly well established – judging by recent electoral results in Europe and in America) should look instead at globalisation’s rotting foundations.

Watching globalisation’s liberal cheerleaders fret as trade is regionalised, capital flows drop off, and production is re-localised, reminds this left-winger of the denial in the faces of quite a few of my comrades as ‘really existing’ socialism was crumpling all around us in 1991. “But globalisation lifted billions from poverty!”, they squeal just as my comrades were squealing, equally correctly, that the Soviet Union had propelled a nation from the plough to Sputnik in a decade. So what? A system that is unsustainable will not be sustained.

Review 2016

If globalisation is no longer viable, what next? The answer offered by the alt-right, the xenophobes, and those who invest in militant parochialism is clear: return to the bosom of the nation-state, surround your selves with electrified fences, and cut deals between the newly walled realms on the basis of national interest and relative brute strength. The fact that this nightmare is presented as a dream is yet another failure of globalisation, just like Donald Trump was a symptom of Barrack Obama’s failure to live up to the expectations he had cultivated amongst the victims of globalisation and its 2008 spasm.

Lest we forget, our problems, are global. Like climate change they demand local action but, also, a level of international cooperation not seen since Bretton Woods. Neither North America nor Europe or China can solve them in isolation or even via trade deals. Nothing short of a progressive, new Bretton Woods can deal with tax injustice, the dearth of good quality jobs, wage stagnation, public debt, personal debt, low investment in things humanity desperately needs, too much spending on things that are bad for us, increasing depravity in a world awash with cash, robots that are marginalising an increasing section of our workforces, prohibitively expensive education that the many need to compete with the robots etc. National solutions, to be implemented under the deception of “getting our country back” and behind strengthened border fences, are bound to yield further discontent as they enable our oligarchs-without-borders to strike trade agreements that confine the many to a race-to-the-bottom while securing their loot in offshore havens.

Our solutions, therefore, must be global too. But to be so they must undermine at once parochialism and globalisation, both the right of capital to move about unimpeded and the fences that stop people and commodities from moving about the planet. In short, our solutions must be internationalist: Tax havens are crying out for international harmonisation. Climate change demands common environmental standards and a green energy union that should be democratically governed lest we end up with new monstrosities.

LES MEES 2016

Free trade must be combined with standards that enhance human happiness everywhere. The financial genie needs to be put back in its bottle with capital controls domestically and globally to be imposed by coordinated action in the Americas, in Europe, in Asia. Money must be democratised and be managed internationally in a manner that eliminates systematic trade deficits and systematic trade surpluses. The robots must become humanity’s slaves (so that the opposite does not obtain), a feat that ultimately requires their common ownership.

All this sounds utopian. But not more so than the idea that the globalisation of the 1990s can be maintained in the 21st century, or be replaced profitably for the majority by a revived nationalism. At historic junctures like the present, humanity is usually faced by a dilemma between an inexact utopia and a certain dystopia. The trick is to opt for the former, realistically, through targeting achievable first goals.

What should these be? Five goals of an International Green New Deal seem pressing and tangible:

(1) Higher wages everywhere, supported by trade agreements predicated upon commonly agreed minimum wages and conditions.

(2) Tax harmonisation, including a simple commitment to deny companies registered in off shore tax havens legal protection of their property rights.

(3) A Green Energy Union focusing on common investment and common standards, with the active support of public investment banks and central banks.

(4) A New Bretton Woods that recalibrates our financial infrastructure, with one umbrella digital currency in which all trade is denominated in a manner that curtails destabilising trade surpluses and deficits.

(5) A universal basic dividend to be administered by the New Bretton Woods institutions and funded by a percentage of big tech shares that are deposited in a World Wealth Fund.

Who should pursue this internationalist agenda? We must!

Progressives from Europe and North America have a duty to start the ball rolling. I have no doubt that, if we embark upon this path, others in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa will soon join us enthusiastically.

Closer to home, our Democracy in Europe Movement, DiEM25, takes this duty seriously. For example, we shall take this agenda, which we refer to as the European Green New Deal, to voters across Europe in the May 2019 European Parliament elections.

And, just in case you wondered, yes, we plan to campaign in Britain too, even though, sadly, there will be no European Parliament elections here.

Why campaign in Britain? Because Brexit or no Brexit, within or without the single market, British progressives and the rest of us on continental Europe must bind together – because we must not allow Brexit to forge new divisions either across the British Channel or between good, progressive Brits who support Brexit and good, progressive Brits who remain Remainers.

So, yes, we shall campaign in Britain too, alongside Jeremy Corbyn, John McDonnel, Caroline Lucas, progressives in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Starting with our first event next week in Sheffield, we shall campaign as symbolic proof of our commitment to the idea of unity amongst all progressives here, on the Continent, in North and South America, in Africa, everywhere.

With globalisation in retreat, and militant parochialism on the rise, we have a moral and political duty to tackle a failing globalisation with a renewed, ambitious internationalism.

Let us begin with an agenda, as Pink Floyd once called upon us to do, to ‘Take Down The Wall’ – this hideous, globalising wall.

Thank you

Το κόστος της τρόικας πριν και μετά το 2015 – ΕφΣυν 6 ΑΠΡ 2018

Από τα 238 δισ. το 2009 συρρικνώθηκε:

5% στα 226 δισ. το 2010

8,4% στα 207 δισ. το 2011

7,7% στα 191 δισ. το 2012

5,4% στα 180,7 δισ. το 2013

1,6% στα 177,9 δισ. το 2014

1,24% στα 175,7 δισ. το 2015

0,9% στα 174,2 δισ. το 2016 (*)

Πίσω από αυτά τα απαίσια νούμερα κρυβόταν μια αποκρουστική πραγματικότητα, την οποία η τρόικα εσωτερικού και εξωτερικού, που φέρει ακέραιη την ευθύνη, πασχίζει να αποποιηθεί. Για αυτό αξίζει να θυμηθούμε τι έγινε ξεχωριστά στην περίοδο 2009-14 και μετά το 2015.

2009-2014

380 χιλιάδες νέοι και νέες εγκατέλειψαν τη χώρα. Από αυτούς που έμειναν περισσότεροι από τους μισούς βρέθηκαν άνεργοι.

3,5 εκατομμύρια εργαζόμενοι έπρεπε να συντηρούν 4,5 εκατομμύρια που δεν εργάζονταν (χωρίς να υπολογίζονται οι ανήλικοι).

Από το 1,4 εκατομμύριο ανέργων μόνο οι 126 χιλιάδες (9%) έλαβαν έστω και ένα ευρώ επίδομα ανεργίας.

Οσοι ήταν αρκετά τυχεροί να μην απολυθούν είδαν τον μισθό τους να μειώνεται 40% κατά μέσον όρο.

Οι συντάξεις μειώθηκαν 12 φορές, 39% κατά μέσον όρο.

Από τα 2,8 εκατομμύρια οικογενειών το 1,4 εκατομμύριο επιβίωνε από μόνο μία σύνταξη.

1 εκατομμύριο νοικοκυριά δεν μπορούσαν να πληρώσουν τη ΔΕΗ.

2,3 εκατομμύρια οικογένειες δεν αντεπεξέρχονταν στις φορολογικές τους υποχρεώσεις.

Από τις 858 χιλιάδες επιχειρήσεις, 229 χιλιάδες έβαλαν λουκέτο, η παραγωγή μειώθηκε κατά 40,2% και 29,3% των υπαλλήλων τους απολύθηκαν.

Οι επενδύσεις σε μηχανήματα, κτίρια, δρόμους κ.λπ. μειώθηκαν από 49,2 δισ. στα 22 δισ.

Οι δημόσιες δαπάνες έπεσαν από 55,3 δισ. στα 36,4 δισ.

Οι δαπάνες των νοικοκυριών μειώθηκαν από 157 δισ. στα 118 δισ.

Το συνολικό ύψος των μισθών κατέρρευσε από τα 84,8 δισ. στα 59,8 δισ.

Οι αποταμιεύσεις συρρικνώθηκαν από 236 δισ. στα 160 δισ.

90 δισ. ιδιωτικών δανείων έγιναν «κατακόκκινα».

Οι δαπάνες για την υγεία μειώθηκαν κατά 20%, εκατοντάδες κλινικές έκλεισαν, εφτά χιλιάδες γιατροί μετανάστευσαν, η συμμετοχή των ασθενών στη φαρμακευτική δαπάνη έφτασε στα ύψη.

Σχολεία έκλεισαν, τα Πανεπιστήμια λειτουργούν σαν σκιά του πρότερου -προβληματικού- εαυτού τους.

Οι αυτοκτονίες αυξήθηκαν κατά 45%.

Μετά τον Ιούλιο του 2015

Από το 2015 έως σήμερα το Δημόσιο «πλήρωσε» στους δανειστές 54,1 δισ. –ποσό ίσο με το σύνολο του τζίρου (προ φόρων) όλων των ελληνικών επιχειρήσεων για 16 μήνες. Βέβαια τα χρήματα αυτά «βγήκαν» από το 3ο μνημονιακό δάνειο των 86 δισ. Από σήμερα μέχρι το 2030 το Δημόσιο θα πρέπει να αποπληρώσει άλλα 98 δισ., από τα οποία τα 66,1 δισ. πρέπει να μαζευτούν από φόρους (καθώς μόνο 31,9 δισ. θα απομείνουν από το 3ο μνημονιακό δάνειο). Κατόπιν από το 2030 μέχρι το 2060 άλλα 174 δισ. θα πρέπει να αποπληρωθούν στην τρόικα (Εχει άδικο το ΜέΡΑ25 να μιλά, με ένταση, περί Χρεοδουλοπαροικίας;)

Στο μεταξύ:

Οι συντάξεις μειώθηκαν και πάλι μεταξύ 10% και 20% και νέες μειώσεις αναμένονται το 2019.

Καταργήθηκε το ΕΚΑΣ.

Η συμμετοχή των ασθενών στη φαρμακευτική δαπάνη αυξήθηκε άλλο ένα 10%.

50% των απόφοιτων Ιατρικών Σχολών μετανάστευσε.

Το αφορολόγητο των φτωχότερων οικογενειών μειώθηκε 5% και θα ξαναμειωθεί το 2019.

Μείωση του επιδόματος θέρμανσης κατά 50%.

Ο πιο ταξικός φόρος, ο ΦΠΑ, αυξήθηκε ραγδαία και σε λίγο θα αυξηθεί σε 35 νησιά του Αιγαίου.

Κάθε μήνα αυξάνονται κατά 1 δισ. οι ληξιπρόθεσμες οφειλές των φορολογούμενων στην Εφορία.

Τα «κόκκινα» δάνεια ξεπέρασαν τα 100 δισ. ενώ ο εξώσεις και οι πλειστηριασμοί εντείνονται.

700 χιλιάδες εργαζόμενοι με μπλοκάκι αναγκάζονται να πληρώνουν υψηλότερο φόρο και να προπληρώνουν στο 100% τον φόρο της επόμενης χρονιάς.

560 χιλιάδες εργαζόμενοι δουλεύουν για 380 ευρώ μεικτά μηνιαίως –σε μια χώρα το ίδιο ακριβή με τη Γερμανία.

Αλλοι 120 χιλιάδες νέοι μετανάστευσαν, με τον ρυθμό της φυγής να αυξάνεται.

Δεκάδες χιλιάδες επιχειρήσεις μετέφεραν την έδρα τους σε Βουλγαρία και Κύπρο.

Απαγόρευση απεργιών όταν δεν συμμετέχουν στις συνελεύσεις τουλάχιστον 50% +1 των μελών του συνδικάτου που έχουν πληρώσει τις συνδρομές τους.

14 περιφερειακά αεροδρόμια τεράστιας διαχρονικής αξίας: πουλήθηκαν σε κρατική γερμανική εταιρεία η οποία δεν έβαλε ούτε ένα ευρώ από τα δικά της, δανειζόμενη όλο το ποσό από τις ελληνικές τράπεζες που ανακεφαλαιοποίησαν οι φορολογούμενοι με δανεικά. Λιμάνια Πειραιά και Θεσσαλονίκης: πουλήθηκαν. Λιμάνι Αλεξανδρούπολης: προς πώληση. ΟΣΕ: πουλήθηκε για ένα κομμάτι ψωμί σε ιταλική εταιρεία που δεν διαθέτει τους πόρους οι οποίοι απαιτούνται να επενδυθούν στους ελληνικούς σιδηρόδρομους.

Ελληνικό: πουλήθηκε σε ολιγάρχη προς 140 ευρώ το τ.μ. με δέσμευση του Δημοσίου να κατασκευάσει έργα που θα ωφελήσουν τον αγοραστή και θα μας κοστίσουν όσα αυτός έδωσε για να το αγοράσει. ΑΔΜΗΕ: μερική πώληση. Μονάδες παραγωγής της ΔΕΗ: προς πώληση. Μετοχές του Δημοσίου σε ΟΤΕ και αεροδρόμιο «Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος»: πουλήθηκαν. Ούτε ένα ευρώ από αυτά τα έσοδα-ψίχουλα δεν θα επενδυθεί στην ελληνική οικονομία, καθώς όλα πάνε στους δανειστές.

Οι αυτοκτονίες παραμένουν στα ίδια επίπεδα.

Αυτά για να μην ξεχνιόμαστε. Και για να μην ξεχνάμε πότε έγινε η καταστροφή, σε τι συνίσταται και ποιοι ευθύνονται.

Εχοντας καταγράψει τον κατάλογο των παθών, ακολουθεί η πραγματική ελπίδα -η ελπίδα που οικοδομείται στην απλή σκέψη και συνειδητοποίηση ότι οι καλύτερες στιγμές του ελληνισμού έρχονται στο ζενίθ μεγάλων κρίσεων- εκείνη ακριβώς τη στιγμή που αν και τα πάντα φαίνονται ολόμαυρα και σκοτεινά, ο λαός μας βρίσκει το κουράγιο να απορρίψει τον φόβο της ήττας, να νεκραναστήσει την ελπίδα και να αγκαλιάσει την υπεύθυνη ανυπακοή απέναντι σε εκείνα που τον εγκλωβίζουν.

(*) Αυτά είναι τα τελικά δεδομένα. Για το 2017 το τελικό νούμερο θα ανακοινωθεί στα τέλη Απριλίου. (Σημειωτέον: Τα μη τελικά στοιχεία πάντοτε εμφανίζονται υπεραισιόδοξα και άρα αποκλείονται ως μη πιστευτά –π.χ. το ΥΠΟΙΚ παρουσίαζε το εθνικό εισόδημα του 2016 αυξημένο σε σχέση με το 2015, πριν αναγκαστεί να παραδεχτεί ότι και το 2016 συνεχίστηκε η ύφεση.)

* γραμματέας του ΜέΡΑ25

Το άρθρο αυτό δημοσιεύτηκε στην Εφημερίδα των Συντακτών την 6η Απριλίου 2018

April 7, 2018

Why we founded new political party MeRA25 to challenge austerity in Greece – The New Statesman, 5 APR 2018

After successfully quashing Greece’s 2015 debtor’s prison break, Europe’s deep establishment has embarked on a mission to declare the country’s economic and social crisis over. To recall Tacitus, “they make a desert and they call it peace”. Since 2015, the Greek state has paid its creditors a sum equal to the aggregate pre-tax revenues of all Greek businesses over an 18-month period. And as if these pounds of flesh were insufficient, between now and 2030, the state must pay the creditors almost twice that sum, and more than three times the same amount between 2030 and 2060. Meanwhile, a vicious class war lurks behind the infamous “reforms” that the “radical left” Syriza government is implementing.

After successfully quashing Greece’s 2015 debtor’s prison break, Europe’s deep establishment has embarked on a mission to declare the country’s economic and social crisis over. To recall Tacitus, “they make a desert and they call it peace”. Since 2015, the Greek state has paid its creditors a sum equal to the aggregate pre-tax revenues of all Greek businesses over an 18-month period. And as if these pounds of flesh were insufficient, between now and 2030, the state must pay the creditors almost twice that sum, and more than three times the same amount between 2030 and 2060. Meanwhile, a vicious class war lurks behind the infamous “reforms” that the “radical left” Syriza government is implementing.Pensions, which had already been slashed by 40 per cent before 2015, have been cut by 10-20 per cent on average (and will be cut again in 2019); the small solidarity payment to the poorest pensioners was abolished; patients’ share of health bills has risen to more than 50 per cent; a third of working people are forced to do so part-time for monthly wages of €380; poor families’ income tax-free threshold has been reduced (and will be cut again in 2019); and the heating allowance for the poor was halved.

Income taxes on families earning €1,000 a month were increased; VAT was hiked to 24 per cent (the third-highest rate in the EU); home evictions accelerate daily; 700,000 workers on zero-hour contracts have been forced to pay higher taxes and, remarkably, to prepay their taxes a year in advance; the small business tax rate rose from 26 per cent to 29 per cent, and firms are also forced to prepay their taxes a year in advance.

Consequently, half a million young Greeks have now migrated (including half of our medical school graduates since 2015) with thousands more leaving every week. Tens of thousands of small and medium businesses have moved to Bulgaria, Cyprus and elsewhere in the European Union where they now pay their taxes.

As for public assets, the offensive fire sales are legion: 14 regional airports were sold to a German state company which paid not one euro of its own: it borrowed all the money from bailed-out Greek banks. The ports of Piraeus and Thessaloniki were sold. The old Athens airport site, probably the finest piece of real estate on the Eastern Mediterranean, was sold to Spiros Latsis, Greece’s wealthiest oligarch, for €140 per square metre, with the state promising to spend more than it received on roads and facilities that will benefit the new owner.

Our electricity grid – partly sold. Our power stations – for sale. Our railways – sold for a measly €47m to an Italian company lacking the resources to invest properly. The state’s share in Athens airport – sold.

To intensify the insult, not one euro received from these fire sales will be invested in Greece – the full proceeds will go to the creditors. Last but not least, suicides remain 45 per cent above their pre-crisis level.

That the inmates have stopped rioting, and the TV vans have moved on, is not inconsistent with conditions worsening in our sun-drenched debtor’s prison. Forcing our young to emigrate and imposing indignity on those who remain, Greece’s debt bondage hangs over it like a thick, dark cloud.

Meanwhile, our rulers are interested solely in persuading the public that Greece “has been sorted”, citing for example the reduction of the unemployment rate to 20.9 per cent, or the government’s success at returning “to the markets” for more loans.

“Can’t they see that unemployment is falling because our children are leaving in droves?” people ask me on the street, their faces contorted with hurt. “Why is it good news that the government borrowed more from foreign bankers when our state is bankrupt?” a taxi driver asked me the other day. No, the Greeks are not fooled by the recovery narrative. But fooling the Greeks is not the establishment’s aim.

As the philosopher Slavoj Žižek wrote to me recently: “They are trying to kill hope: the message of their propaganda is a resigned conviction that the world we live in, even if not the best of all possible worlds, is the least bad one, so that any radical change can only make it worse… With Syriza, the ‘radical left’ party, doing the dirty job of austerity, hope was killed, depoliticisation and demoralisation exploded.”

Nothing threatens a people more than the sense that there is no alternative to a path to oblivion. Our quiet desperation has lasted long enough. This is why we are now coming to the fore to create a credible alternative to Greece’s arid political landscape. On 26 March, we founded a new Greek party, MeRA25 – the European Realistic Disobedience Front.

MeRA25 is not just another political party. It is an indivisible part of DiEM25, the radical, transnational, Europeanist Democracy in Europe Movement 2025; a pan-European front against the dominant oligarchy-without-borders but also against nationalist parochialism. Constructive disobedience is our strategy in the context of our founding purpose: “In Europe. Against this Europe!” Putting radical democratic transnationalism into practice, MeRA25’s policy framework and office holders are chosen not only by our Greek members but also by our German, Italian, British and Polish DiEM25 counterparts.

As for our manifesto, we have already put forward seven detailed bills which the party intends to table in order to end Greece’s debt bondage immediately and without any prior negotiation with Brussels. While not advocating “Grexit”, if the EU threatens us with expulsion for enacting our seven bills, our answer will be: “Do your worst.”

We do not fear failure. We fear capitulation, submission, surrender. We do not fear putting the bar too high and failing. We fear the prospect of training our eyes too low and ending up on our knees.

This is why we have founded MeRA25.

The new party MeRA25’s website is here

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2451 followers