Steve Blank's Blog, page 50

October 10, 2011

Nokia as "He Who Must Not Be Named" and the Helsinki Spring

I was invited to Finland as part of Stanford's Engineering Technology Venture Program partnership with Aalto University. (Thanks to Kristo Ovaska and team for the fabulous logistics!) I presented to 1,000's of entrepreneurs, talked to 17 startups, gave 12 lectures, had 9 interviews, chatted with 8 VC's, sat on 4 panels, talked policy with 2 government ministers, 2 members of parliament, 1 head of a public pension fund and was in 1 TV-documentary. More details can be found at www.steveblank.fi

This is part 2 of 2 of what I found. Part 1 can be found here.

Toxic Business Press and Contradictory Government Incentives

Unique to Finland with its strong cultural emphasis on equality and the redistribution of wealth is a business press that doesn't understand startups and is overtly hostile to their success. When MySQL was sold for $1B and the cleantech company the Switch got acquired for $250M, one would have expected the country to celebrate that they had built these world-class companies. Instead the business press dumped on the founders for "selling out." In 2010 it got worse with an Act in parliament about the Monitoring of Foreigners' Corporate Acquisitions. Many founders mentioned this as a reason not to incorporate or grow their companies in Finland.

While the government says they love startups, the first thing they did this year is raise the capital gains tax. While it might have been politically expedient, it was not a welcome sign for long-term investment. I suggested they consider an investment tax credit for pension funds that invest in Finnish based VC firms.

Nokia as "He Who Must Not Be Named"

I was in Finland three days before I realized that no one had mentioned the word "Nokia." After I brought it up in a meeting, you could have heard a pin drop. Nokia was Finland's symbol of national competence. Most Finns take their failure as a personal embarrassment. (Note to Finland – lighten up. Nokia was blind-sided in a classic disruptive innovation. 50% the fault of a Nokia management that didn't see it coming, while 50% was due to brilliant Apple execution.) Ultimately, Nokia's difficulties will turn out to be good news for Finnish entrepreneurs. They've stopped hiring the best talent, and startups are not looking so risky compared to large companies.

Nanny-Culture, Lack of Risk Taking, Not Sharing

What makes Finland such a wonderful place to live and raise a family may ultimately be what kills it as a startup hub. There's a safety net in almost every part of one's public and private life – health insurance, free college tuition, unions, collective bargaining, fixed work hours, etc. And what's great for the mass of society – a government safety net verging on the ultimate nanny state – makes it impossible to fail. You find early stage employees expecting to work normal hours, to get paid a regular salary, and not asking or expecting equity. There isn't much of a killer instinct among the masses.

It's the rare region where risk equals experience. By nature Finns are not good at tolerating risk. This gets compounded by the cultural tendency not to share or talk in meetings, sometimes to the point of silence. This is a fundamental challenge in creating an entrepreneurial culture. This extends to sharing among startups. The insular nature of the culture hasn't yet created a "pay it forward" culture.

Summary

The young entrepreneurs I met are bringing impressive energy and intelligence to their goal of building one of Europe's leading technology hubs in Helsinki. Finland itself has significant engineering talent, and is also attracting entrepreneurs from Russia and the former USSR. It will be fascinating to see if they can lead the cultural change and secure the political support (in a government run by an older generation) to support their vision.

Lessons Learned

Finland is trying to engineer an entrepreneurial cluster as a National policy to drive economic growth through entrepreneurial ventures

They've gotten off to a good start with a start around Aalto University with passionate students

Startup incubators, business angels and VCs are starting to emerge

The country needs to figure out a long term privatization strategy for Venture investing

Finnish culture makes risk-taking and sharing hard

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching, Venture Capital

October 7, 2011

The Helsinki Spring

I spent the month of September lecturing, and interacting with (literally) thousands of entrepreneurs in two emerging startup markets, Finland and Russia. This is the first of two posts about Finland and entrepreneurship.

——

I was invited to Finland as part of Stanford's Engineering Technology Venture Program partnership with Aalto University. (Thanks to Kristo Ovaska and team for the fabulous logistics!) I presented to 1,000's of entrepreneurs, talked to 17 startups, gave 12 lectures, had 9 interviews, chatted with 8 VC's, sat on 4 panels, talked policy with 2 government ministers, 2 members of parliament, 1 head of a public pension fund and was in 1 TV-documentary.

What I found in Finland was:

a whole lot of smart, passionate entrepreneurs who want to build a startup hub in Helsinki

a government that's trying to help, but gets in the way

a number of exciting startups, but most with a narrow, too-local view of the world

and the sense that, before too long, they may well get it right!

While a week is not enough time to understand a country this post – the first of two – looks at the Finnish entrepreneurial ecosystem and its strengths and weaknesses.

The Helsinki Spring

Entrepreneurship and innovation are bubbling around Helsinki and Aalto University. There are thousands of excited students, and Aalto university is working hard to become an outward facing institution. Having a critical mass of people who think startups are cool in the same location is a key indicator of whether a cluster can catch fire. Finnish startup successes on a global stage include MySQL, F-Secure, Rovio, Habbo, Playfish, The Switch, Tectia, Trulia and Linux. While it's not clear yet whether the numbers of startups in Helsinki are sufficient to ignite, it feels like it's getting there, (and given the risk-averse and paternal nature of Finland that by itself is a miracle.)

The good news is that for a 5 million person country, there's an emerging entrepreneurial ecosystem that looks like something this:

Aalto University: Aalto Center for Entrepreneurship, Aalto Entrepreneurship Society

Startup Accelerators: Startup Sauna and Vigo which includes Lifeline Ventures, KoppiCatch, and Veturi

Startup Blog: Arctic Startup

Business Angels: FiBAn, Sitra

Venture Capital: FVCA, NextIt Ventures, Primus Ventures, Open Ocean Capital, Connor VC, and Inventure

Government Funding: Tekes, Sitra, Finnvera, Finnish Investment Industry

9-to-5 Venture Capital

Ironically one of the things that's holding back the Finnish cluster is Tekes, the government organization for financing research, development and innovation in Finland. It's hard enough to pick which existing companies with known business models to aid. Yet Tekes does that and is trying to act like a government-run Venture Capital firm. At Tekes, government employees (and their hired consultants) – with no equity, no risk or reward, no startup or venture capital experience – try to pick startup winners and losers.

Tekes has ended up competing with and stifling the nascent VC industry, indiscriminately handing out checks to entrepreneurs like an entitlement. (To be fair this is an extension of the government's role in almost all parts of Finnish life.)

In addition to Tekes, Vigo, the government's attempt at funding private business accelerators, started with good intentions and got hijacked by government bureaucrats. The accelerators I met with (the ones the government pointed to as their success stories) said they were leaving the program.

Tekes lacks a long-term plan of what the Finnish government's role should be in funding startups. I suggested that they might want to consider putting themselves out of the public funding business by using public capital to kick-start private venture capital firms, incubators and accelerators. And they should give themselves a 5-10 year plan to do so. Instead they seem to be stuck in the twilight zone of not having a long-term vision of their role. (There has been tons of reports on what to do, all seemingly ignored by an entrenched bureaucracy.)

Lack of Business Experience

Direct government funding of startups has also delayed the maturation of business experience of local angels and VC's. Finnish private investors don't yet have enough time-in-grade to have developed good pattern recognition skills, and most lack operating backgrounds. I have no doubt they'll get there by themselves, but in wouldn't take much imagination to attempt to recruit some seasoned overseas investors to add to the mix.

Even a more serious challenge is the lack of global business competence. The number of serial entrepreneurs is very low and until recently most of the talented sales and marketing professionals choose to work for Nokia.

Part 2 with more observations about Finland and the Lessons Learned will follow shortly.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching, Technology, Venture Capital

September 22, 2011

How To Build a Web Startup – Lean LaunchPad Edition

As part of our Lean LaunchPad classes at Stanford, Berkeley, Columbia and for the National Science Foundation, students build a startup in 8 weeks using Business Model Design + Customer Development.

One of the problems they run into is building a web site.

———

If you're an experienced coder and user interface designer you think nothing is easier than diving into Ruby on Rails, Nodes.js and Balsamiq and throwing together a web site. (Heck, in Silicon Valley even the waiters can do it.)

But for the rest of us mortals whose eyes glaze over at the buzzwords, the questions are, "How do I get my great idea on the web? What are the steps in building a web site?" And the most important question is, "How do I use the business model canvas and Customer Development to test whether this is a real business?"

My first attempt at helping my students answer these questions was by putting together the Startup Tools Page - a compilation of available web development tools. While it was a handy reference, it still didn't help the novice.

So today, I offer my next attempt.

How To Build a Web Startup – The Lean LaunchPad Edition

Here's the step-by-step process we suggest our students use in our Lean LaunchPad classes.

Set up the logistics to manage your team

Craft company hypotheses

Set up the Website Logistics

Build a "low-fidelity" web site

Get customers to the site

Add the backend code to make the site work

Test the "problem" with customer data

Test the "solution" by building the "high-fidelity" website

(Use the Startup Tools Page as the resource for tool choices)

Step 1: Set Up Team Logistics

Read Business Model Generation pages 1-72, and The Four Steps to the Epiphany Chapter 3

Set up the Lean LaunchLab or a WordPress blog to document your Customer Development progress

Use Skype or Google+ Hangouts for team conversations

Step 2. Craft Your Company Hypotheses (use the Lean LaunchLab)

Write down your 9-business model canvas hypothesis

List key features/Minimal Viable product plan

Size the market opportunity

Pick market type (existing, new, resegmented)

Prepare weekly 7-minute class progress summary: business model canvas update + weekly Customer Development summary (described after Step 8.)

Step 3: Website Logistics

Get a for your company. To find an available domain quickly, try Domize

Then use godaddy or namecheap to register the name. (RetailMeNot usually has ~ $8/year discount coupons for Godaddy You may want to register many different domains (different possible brand names, or different misspellings and variations of a brand name.)

Once you have a domain, set up Google Apps on that domain (for free!) to host your company name, email, calendar, etc

For coders: set up a web host

Use virtual private servers (VPS) like Slicehost or Linode (cheapest plans ~$20/month, and you can run multiple apps and websites)

You can install Apache or Nginx with virtual hosting, and run several sites plus other various tools of your choice (assuming you have the technical skills of course) like a MySQL database

If you are actually coding a real app, (rather than for class) use a "Platform As A Service" (PAAS) like Heroku, DotCloud or Amazon Web Services if your app development stack fits their offerings

BTW: You can see the hosting choices of YCombinator startups here

Step 4: Build a Low-Fidelity Web Site

For non-coders:

Make a quick prototype in PowerPoint, or

Use Unbounce, Google Sites, Weebly, Godaddy or Yola

For coders: build the User Interface

Pick a website wireframe prototyping tool, (i.e. JustinMind, Balsamiq)

99 Designs is great to get "good enough" graphic design and web design work for very cheap using a contest format. Themeforest has great designs

Create wireframes and simulate your "Low Fidelity" website

Create a "viral" landing page, with LaunchRock or KickoffLabs

Embed a slideshow on your site with Slideshare or embed a video/tour using Youtube or Vimeo

Step 5: Customer Engagement (drive traffic to your preliminary website)

Start showing the site to potential customers, testing customer segment and value proposition

Use Ads, textlinks or Google AdWords, Facebook ads and natural search to drive people to your Minimally Viable web site

Use Mailchimp, Postmark or Google Groups to send out emails and create groups

Create online surveys with Wufoo or Zoomerang

Get feedback on your MVP features and U/I

Step 6: Build a more complete solution (Connect the U/I to code)

Connect the UI to a web application framework (for example, Node.js, Rubyon Rails, Django, SproutCore, Jquery, Symfony, Sencha, etc.)

Step 7: Track your progress in driving traffic – Test the "Customer Problem" by collecting Customer Data

Use Web Analytics tools (Kissmetrics, Google Analytics, Mixpanel, etc.) to track hits, time on site, source

Create account to measure user satisfaction (GetSatisfaction, UserVoice, etc.) from your product and get feedback and suggestions on new features

analyze the behavior of your user in your website

Step 8: Test the "Customer Solution" by building a full featured High Fidelity version of your website

Update the Website with information learned in Step 5-7

For all Steps: Monitor and record changes week by week using the Lean LaunchLab

For Class: Use the Lean LaunchLab to produce a 7-minute weekly progress presentation

Start by putting up your business model canvas

Changes from the prior week should be highlighted in red

Lessons Learned. This informs the group of what you learned and changed week by week – Slides should describe:

Here's what we thought (going into the week)

Here's what we found (Customer Discovery during the week)

Here's what we're going to do (for next week)

Emphasis should be on the discovery done for that weeks assigned canvas component (channel, customer, revenue model) but include other things you learned about the business model.

———

If you're Building a Company Rather Than a Class Project

Search the US Patent Office (for free) for similar trademarks to yours

When you confirmed your product and identity, and obtained a good domain name, and a trademark you think you can own, register your company on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, CrunchBase, and AngelList pages

Incorporate the company

———

Comments, suggestions, corrections, additions and brickbats welcomed.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad

September 15, 2011

The Pay-It-Forward Culture

Foreign visitors to Silicon Valley continually mention how willing we are to help, network and connect strangers. We take it so for granted we never even to bother to talk about it. It's the "Pay-It-Forward" culture.

——-

We're all in this together – The Chips are Down

in 1962 Walker's Wagon Wheel Bar/Restaurant in Mountain View became the lunch hangout for employees at Fairchild Semiconductor. When the first spinouts began to leave Fairchild, they discovered that fabricating semiconductors reliably was a black art. At times you'd have the recipe and turn out chips, and the next week something would go wrong, and your fab couldn't make anything that would work. Engineers in the very small world of silicon and semiconductors would meet at the Wagon Wheel and swap technical problems and solutions with co-workers and competitors.

We're all in this together – A Computer in every Home

In 1975 a local set of hobbyists with the then crazy idea of a computer in every home formed the Homebrew Computer Club and met in Menlo Park at the Peninsula School then later at the Stanford AI Lab. The goal of the club was: "Give to help others." Each meeting would begin with people sharing information, getting advice and discussing the latest innovation (one of which was the first computer from Apple.) The club became the center of the emerging personal computer industry.

We're all in this together – Helping Our Own

Until the 1980's Chinese and Indian engineers ran into a glass ceiling in large technology companies held back by the belief that "they make great engineers but can't be the CEO." Looking for a chance to run their own show, many of them left and founded startups. They also set up ethnic-centric networks like TIE (The Indus Entrepreneur) and the Chinese Software Professionals Association where they shared information about how the valley worked as well as job and investment opportunities. Over the next two decades, other groups — Russian, Israeli, etc. — followed with their own networks. (Anna Lee Saxenian has written extensively about this.)

We're all in this together – Mentoring The Next Generation

While the idea of groups (chips, computers, ethnics) helping each other grew, something else happened. The first generation of executives who grew up getting help from others began to offer their advice to younger entrepreneurs. These experienced valley CEOs would take time out of their hectic schedule to have coffee or dinner with young entrepreneurs and asking for nothing in return.

They were the beginning of the Pay-It-Forward culture, the unspoken Valley culture that believes "I was helped when I started out and now it's my turn to help others."

By the early 1970's, even the CEOs of the largest valley companies would take phone calls and meetings with interesting and passionate entrepreneurs. In 1975, a young unknown, wannabe entrepreneur called the Founder/CEO of Intel, Bob Noyce and asked for advice. Noyce liked the kid, and for the next few years, Noyce met with him and coached him as he founded his first company and went through the highs and lows of a startup that caught fire.

Steve Jobs and Robert Noyce

The entrepreneur was Steve Jobs. "Bob Noyce took me under his wing, I was young, in my twenties. He was in his early fifties. He tried to give me the lay of the land, give me a perspective that I could only partially understand," Jobs said, "You can't really understand what is going on now unless you understand what came before."

What Are You Waiting For?

Last week in Helsinki Finland at a dinner with a roomful of large company CEO's, one of them asked, "What can we do to help build an ecosystem that will foster entrepreneurship?" My guess is they were expecting me talk about investing in startups or corporate partnerships. Instead, I told the Noyce/Jobs story and noted that, as a group, they had a body of knowledge that entrepreneurs and business angels would pay anything to learn. The best investment they could make to help a startup culture in Finland would be to share what they know with the next generation. Even more, this culture could be created by a handful of CEO's and board members who led by example. I suggested they ought to be the ones to do it.

We'll see if they do.

——

Over the last half a century in Silicon Valley, the short life cycle of startups reinforced the idea that - the long term relationships that lasted was with a network of people - much larger than those in your current company. Today, in spite of the fact that the valley is crawling with IP lawyers, the tradition of helping and sharing continues. The restaurants and locations may have changed, moving from Rickey's Garden Cafe, Chez Yvonne, Lion and Compass and Hsi-Nan to Bucks, Coupa Café and Café Borrone, but notion of competitors getting together and helping each other and experienced business execs offering contacts and advice has continued for the last 50 years.

It's the "Pay-It-Forward" culture.

Lessons Learned

Entrepreneurs in successful clusters build support networks outside of existing companies

These networks can be around any area of interest (technology, ethnic groups, etc.)

These were mutually beneficial – you learned and contributed to help others

Over time experienced executives "pay-back" the help they got by mentoring others

The Pay-It-Forward culture makes the ecosystem smarter

Filed under: Family/Career, Secret History of Silicon Valley, Teaching

September 1, 2011

Why Governments Don't Get Startups

Not understanding and agreeing what "Entrepreneur" and "Startup" mean can sink an entire country's entrepreneurial ecosystem.

———

I'm getting ready to go overseas to teach, and I've spent the last week reviewing several countries' ambitious attempts to kick-start entrepreneurship. After poring through stacks of reports, white papers and position papers, I've come to a couple of conclusions.

1) They sure killed a ton of trees

2) With one noticeable exception, governmental entrepreneurship policies and initiatives appear to be less than optimal, with capital deployed inefficiently (read "They would have done better throwing the money in the street.") Why? Because they haven't defined the basics:

What's a startup? Who's an entrepreneur? How do the ecosystems differ for each one? What's the role of public versus private funding?

Six Types of Startups – Pick One

There are six distinct organizational paths for entrepreneurs: lifestyle business, small business, scalable startup, buyable startup, large company, and social entrepreneur. All of the individuals who start these organizations are "entrepreneurs" yet not understanding their differences screws up public policy because the ecosystem in supporting each type is radically different.

For policy makers, the first order of business is to methodically think through which of these entrepreneurial paths they want to help and grow.

Lifestyle Startups: Work to Live their Passion

On the California coast where I live, we see lifestyle entrepreneurs like surfers and divers who own small surf or dive shop or teach surfing and diving lessons to pay the bills so they can surf and dive some more. A lifestyle entrepreneur is living the life they love, works for no one but themselves, while pursuing their personal passion. In Silicon Valley the equivalent is the journeyman coder or web designer who loves the technology, and takes coding and U/I jobs because it's a passion.

Small Business Startups: Work to Feed the Family

Today, the overwhelming number of entrepreneurs and startups in the United States are still small businesses. There are 5.7 million small businesses in the U.S. They make up 99.7% of all companies and employ 50% of all non-governmental workers.

Small businesses are grocery stores, hairdressers, consultants, travel agents, Internet commerce storefronts, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, etc. They are anyone who runs his/her own business.

They work as hard as any Silicon Valley entrepreneur. They hire local employees or family. Most are barely profitable. Small business entrepreneurship is not designed for scale, the owners want to own their own business and "feed the family." The only capital available to them is their own savings, bank and small business loans and what they can borrow from relatives. Small business entrepreneurs don't become billionaires and (not coincidentally) don't make many appearances on magazine covers. But in sheer numbers, they are infinitely more representative of "entrepreneurship" than entrepreneurs in other categories—and their enterprises create local jobs.

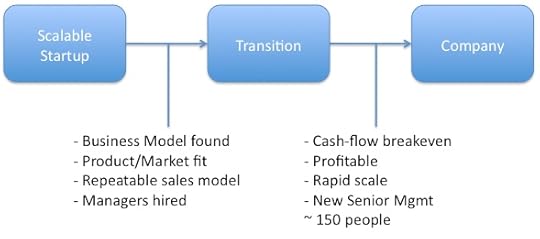

Scalable Startups: Born to Be Big

Scalable startups are what Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and their venture investors aspire to build. Google, Skype, Facebook, Twitter are just the latest examples. From day one, the founders believe that their vision can change the world. Unlike small business entrepreneurs, their interest is not in earning a living but rather in creating equity in a company that eventually will become publicly traded or acquired, generating a multi-million-dollar payoff.

Scalable startups require risk capital to fund their search for a business model, and they attract investment from equally crazy financial investors – venture capitalists. They hire the best and the brightest. Their job is to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. When they find it, their focus on scale requires even more venture capital to fuel rapid expansion.

Scalable startups tend to group together in innovation clusters (Silicon Valley, Shanghai, New York, Boston, Israel, etc.) They make up a small percentage of the six types of startups, but because of the outsize returns, attract all the risk capital (and press.)

Just in the last few years we've come to see that we had been building scalable startups inefficiently. Investors (and educators) treated startups as smaller versions of large companies. We now understand that's just not true. While large companies execute known business models, startups are temporary organizations designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.

This insight has begun to change how we teach entrepreneurship, incubate startups and fund them.

Buyable Startups: Born to Flip

In the last five years, web and mobile app startups that are founded to be sold to larger companies have become popular. The plummeting cost required to build a product, the radically reduced time to bring a product to market and the availability of angel capital willing to invest less than a traditional VCs– $100K – $1M versus $4M on up – has allowed these companies to proliferate – and their investors to make money. Their goal is not to build a billion dollar business, but to be sold to a larger company for $5-$50M.

Large Company Startups: Innovate or Evaporate

Large companies have finite life cycles. And over the last decade those cycles have grown shorter. Most grow through sustaining innovation, offering new products that are variants around their core products. Changes in customer tastes, new technologies, legislation, new competitors, etc. can create pressure for more disruptive innovation – requiring large companies to create entirely new products sold to new customers in new markets. (i.e. Google and Android.) Existing companies do this by either acquiring innovative companies (see Buyable Startups above) or attempting to build a disruptive product internally. Ironically, large company size and culture make disruptive innovation extremely difficult to execute.

Social Startups: Driven to Make a Difference

Social entrepreneurs are no less ambitious, passionate, or driven to make an impact than any other type of founder. But unlike scalable startups, their goal is to make the world a better place, not to take market share or to create to wealth for the founders. They may be organized as a nonprofit, a for-profit, or hybrid.

So What?

When I read policy papers by government organizations trying to replicate the lessons from the valley, I'm struck how they seem to miss some basic lessons.

Each of these six very different startups requires very different ecosystems, unique educational tools, economic incentives (tax breaks, paperwork/regulation reduction, incentives), incubators and risk capital.

Regions building a cluster around scalable startups fail to understand that a government agency simply giving money to entrepreneurs who want it is an exercise in failure. It is not a "jobs program" for the local populace. Any attempt to make it so dooms it to failure.

A scalable startup ecosystems is the ultimate capitalist exercise. It is not an exercise in "fairness" or patronage. While it's a meritocracy, it takes equal parts of risk, greed, vision and obscene financial returns. And those can only thrive in a regional or national culture that supports an equal mix of all those.

Building an scalable startup innovation cluster requires an ecosystem of private not government-run incubators and venture capital firms, outward-facing universities, and a rigorous startup selection process.

Any government that starts public financing entrepreneurship better have a plan to get out of it by building a private VC industry. If they're still publically funding startups after five to ten years they've failed.

To date, Israel is only country that has engineered a successful entrepreneurship cluster from the ground up. It's Yozma program kick-started a private venture capital industry with government funds, (emulating the U.S. lesson of using SBIC funds.), but then the government got out of the way.

In addition, the Israeli government originally funded 23 early stage incubators but turned them over to the VC's to own and manage. They're run by business professionals (not real-estate managers looking to rent out excess office space) and entry is not for life-style entrepreneurs, but is a bootcamp for VC funding.

Unless the people who actually make policy understand the difference between the types of startups and the ecosystem necessary to support their growth, the chance that any government policies will have a substantive effect on innovation, jobs or the gross domestic product is low.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Teaching, Technology, Venture Capital

August 29, 2011

It's Not How Big It Is – It's How Well It Performs: The Startup Genome Compass

What makes startups succeed or fail? More than 90% of startups fail, due primarily to self-destruction rather than competition. For the less than 10% of startups that do succeed, most encounter several near death experiences along the way. Simply put, while we now have some good theory, we just are not very good at creating startups yet. After 50 years of technology entrepreneurship it's still an art.

Three months ago I wrote about my ex-student Max Marmer and the Startup Genome Project. They've been attempting to quantify the art. They believe that they can crack the code of innovation and turn entrepreneurship into a science if they had hard data rather than speculation of why startups succeed or fail. Max and his partners had interviewed and analyzed over 650 early-stage Internet startups. In May they released the first Startup Genome Report— an in-depth analysis on what makes early-stage Internet startups successful.

Now 90 days later Max and his team have gathered data on 3200 startups and they believe they've discovered the most common reason startups fail.

Today you're invited to benchmark your own internet startup and see how you compare to the winners.

———

Benchmarking Your Startup

I hadn't heard from Max for awhile so I thought he took the summer off. I should have known better, it turned out he was hard at work.

Max and his team built a website called the Startup Genome Compass (their benchmarking web site) that allows an Internet startup to evaluate their business performance. The Startup Genome Compass uses a hybrid "Stage and Type" model that describes how startups progress through their business development lifecycle.

The benchmark takes 20 or so minutes to go through as series of questions, and in the end it spits out an analysis of how you are doing.

The benchmark is not perfect, it may even be flawed, but it is head and shoulders above what we have now – which is nothing – for giving Internet startups founders specific advice on best practices. If you have a few world-class VC's on your board you're probably getting this advice in person. If you're like thousands of other startups struggling to get started, it's worth a look.

It's Not How Big It Is – It's How Well It Performs

If you're interested (and you should be) in how you compare to other early stage ventures, they summarized their results in a report "Startup Genome Report Extra: Premature Scaling."

One of the biggest surprises is that success isn't about size – of team or funding. It turns out Premature Scaling is the leading cause of hemorrhaging cash in a startup – and death. In fact:

The team size of startups that scale prematurely is 3 times bigger than the consistent startups at the same stage

74% of high growth Internet startups fail due to premature scaling

Startups that scale properly grow about 20 times faster than startups that scale prematurely

93% of startups that scale prematurely never break the $100k revenue per month threshold

The last time I wrote about Max I said, "I can't wait to see what Max does by the time he's 21." Turns out his birthday is in a week, September 7th.

Happy birthday Max.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Market Types

August 22, 2011

Hiring – Easy as Pie

Over the last few weeks I've gotten involved in hiring for two startups, a public agency and a non profit. Part of each conversation was getting asked to help them put together a "job spec."

I had them leave with a pie chart.

——–

There must be something in the air. In the last week I had four separate groups through the ranch all wanting to talk either about hiring a senior exec or a senior exec looking for a new job. Having sat through these job discussions as an entrepreneur, board member, and now an interested observer, here's what I concluded:

Decide whether you're hiring someone to help search for the business model or to help execute a business model you've already found (same is true is you're looking for a job – are you going to be searching or executing?) Are you looking for a visionary or an operating executive?

The job spec's for the same title differ wildly depending on whether the job requires search versus execution skills. Founders search, operating executives execute.

If you're hiring an operating executive (CEO, VP, Executive Director, etc.)

Don't start with the candidate (board member x has a great VP of sales he knows, founder y wants this CEO he met at a conference, etc.)

Don't even start with the job spec

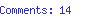

Since I've always been a visual guy, job specs with their long lists of job requirements always left me cold. My eyes would glaze over at these recruiter/board wish lists. I wished there was a way to see them at a glance. (Just to be clear this isn't the entire hiring process, just a way to visually begin the discussion.) So here's my suggestion: Start with a Pie Chart.

Draw a pie chart.

List all the job specs as slices

Adjust the width of the pie segments by importance. (Extra credit if you get the current CEO or internal candidate to help you write/draw the slices and weight their importance. Everyone involved in the hire gets to have an opinion on the slices and weights, but the person/group making the hiring decision gets to decide which ones to include.)

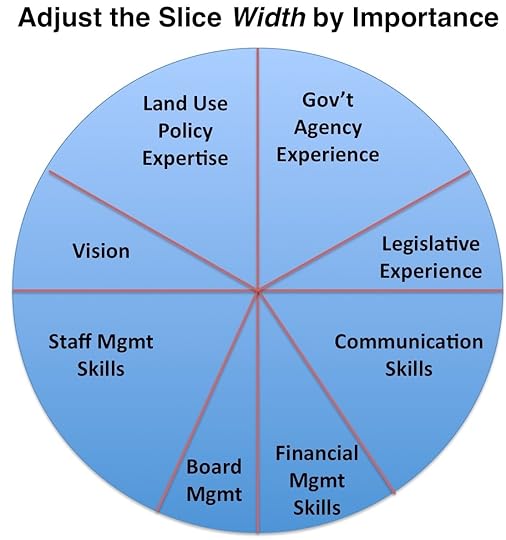

Now that you have this spec, evaluate each candidate by showing his/her competence in each slice by length

Compare candidates

Easy as pie!

Lessons Learned

Are you hiring for search or execution skills?

Show the job requirements visually as a pie chart

Prioritize each requirement by the width of the pie

Show your assessment of each candidate's competencies by the length of the slices

Now with the data in front of you, the conversation about hiring can start

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development, Family/Career, Technology

August 17, 2011

The Four Steps to the Epiphany is Now in Russian

The Four Steps to the Epiphany (Четыре Шага к Озарению) is now available in Russian.

Thanks to Denis Dovgopoliy for making the Russian version happen.

Thanks to Denis Dovgopoliy for making the Russian version happen.

It joins the French version: Les quatre étapes vers l'épiphanie

and the Japanese version アントレプレナーの教科書 [単行本(ソフトカバー)

and the Japanese version アントレプレナーの教科書 [単行本(ソフトカバー)

Now in Japanese

Pay It Forward

What's pretty remarkable is these translations are not from a commercial publisher, but rather a labor of entrepreneurial love. All these translations have been crowd-sourced.

Entrepreneurs from Japan, France and now Russia believed they could help startups in their country if the Four Steps to the Epiphany was available in their native tongue. They translated it at their own expense. These are the first three translations and more are underway.

These individuals are "paying it forward" for their communities and country's. Thousands of entrepreneurs are better for their efforts.

Blame it On Eric

We can blame it all on Eric Ries. When Eric was my student in one of the first Berkeley Customer Development classes, he suggested that I take my class notes, which until then had been printed at Cafepress.com, and offer it widely on Amazon. He said, "I bet there are a few people outside the class who might like to read it." I photoshopped a cover for my notes, called it the Four Steps to the Epiphany, and bet him he was wrong. He won the bet.

What A Long Strange Trip It's Been

I was going to end this post here, but it's late at night at the ranch and the coyotes are howling in the distance and somewhere closer, out in the redwoods, there's a barn owl hooting in the trees.

Seeing this book in Russian for me is more than just another translation.

As a child, my mother fled the Soviet Union smuggled out in a hay cart in the middle of Russian Civil war. Until she died, she reminded me that on the way to Ellis Island, her first view of the United States was the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor - and she never looked back. (As kids we memorized the poem inside the statue.)

When I was growing up the odds were pretty low that the Cold War war would end with a whimper rather than a bang. Both the U.S. and the Soviet Union trained daily to kill hundreds of millions of people. Entrepreneurship was a crime in the Soviet Union. In the 1970′s the Soviet military was on the ascendency and wasn't at all clear that the 20th century would end as the American century (or with 15,000 targeted nuclear warheads, anyones century.)

I spent my late teens here and my early 20′s here next to the sharp end of the spear, and this was no videogame. (There's equal part irony and satisfaction that Silicon Valley and semiconductor fabs had a role in the demise of the Soviet Union.)

When the Cold War ended I waited for the victory parade down Main Street.

We never did have a parade, but as a consolation prize there's now a McDonalds in Red Square, entrepreneurship is trying to blossom in a place that had 60 U.S. nuclear weapons aimed at it, my book (a revolutionary manual for capitalism,) is in Russian, and I've been asked to give my Secret History of Silicon Valley talk when I visit Moscow for the first time in September.

Good enough.

Filed under: Customer Development

August 15, 2011

There's Always a Plan B

Everyone has a plan 'till they get punched in the mouth.

Mike Tyson

One of the key distinctions between an entrepreneur and an operating executive is an entrepreneur's almost seamless agility in the face of changing circumstances versus an operating executive's intense execution focus on a plan. World-class entrepreneurs learn how to combine both.

WTF?

Driving home over the mountains from a Coastal Commission hearing, I had time to ponder an email I received from a city official as the road wound through the Redwood trees. The Coastal Commission had found that a zoning change his city requested didn't conform to the Coastal Act, and we denied it. I felt sorry for him because he had put together a project that depended upon the property owner, developer, unions, hotel operator, local neighbors, city council, weather, wind speed, phase of the moon and astrological sign all aligning just to get the project in front of us. It was like herding cats and pushing water uphill. Reading his email I was sympathetic realizing that if you substituted customers, channel, product development, hiring, board of directors, and fund raising, he was describing a typical day at a startup. I felt real kinship until I got to his last sentence:

"Now we're screwed because we had no Plan B."

I had to read his email a few times to let this sink in. I kept thinking, "What do you mean there's no plan B?" When I shared it with the other commissioners who were public officials, all of them could see that there could have been tons of alternate plans to get a project approved, and there were still several options going forward. But the mayor just had been so intently focussed on executing a complex Plan A he never considered that he might need a Plan B.

By the time the mountain road unwound into rolling pastures and then flattened into the farmland just south of Silicon Valley, I realized that this was a real-world example of the difference between an entrepreneur and an operating executive.

There's Always a Plan B

My formal definition of a startup is a temporary organization in search of a scalable and repeatable business model. Yet if you've founded a company you know that regardless of any formal definition, startups are inherently pure chaos. As a founder, keeping your company alive requires you to think creatively and independently because more often than not, conditions on the ground will change so rapidly that any original well-thought-out plan quickly becomes irrelevant. (It's equally true for startups, war, love and life.)

The reality is that to survive requires a mindset which can quickly separate the crucial from the irrelevant, synthesize the output, and use this intelligence to create islands of order in the all-out chaos of a startup.

To do this you are instinctually creating and testing multiple hypotheses which are creating an infinite number of possible future plans. And when the inevitable happens and some or all your assumptions were wrong, you pivot your model into the next plan and continue forward. You do this until you find a scalable and repeatable business model or you die by running out of money.

Great entrepreneurs don't just have a Plan B, they have Plans B through ∞

Lessons Learned

A startup is initially about the search for a repeatable and scalable business model

Most of the time your hypotheses about Plan A, B and C are wrong

Searching requires agility, tenacity, resilience, curiosity, opportunism and pattern recognition

Execution requires a different set of skills. At times it means bringing an operating executive

Operating executives excel at focussed execution

World-class technology CEO's learned how to combine Searching and Execution (Gates, Jobs, Ellison, Bezos, Page, et al)

Filed under: California Coastal Commission, Customer Development

August 11, 2011

Going Out With His Boots On

He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again

Shakespeare, Hamlet Act I, Scene 2

With 37 mllion people it's remarkable that California has one of the most pristine and unspoiled coastline in the United States. One man and the organization he's built is responsible for protecting it.

———–

California Dreaming

California Highway 1, (the Pacific Coast Highway) is a two-lane road that hugs the coast from Mexico to the town of Leggett in Northern California. It's carved out of the edge of the California almost designed to connect you to the Pacific Ocean in a way that no other road in the country does. In some stretches It's breathtaking and hair-raising and in others it's the most tranquil drive you'll ever take.

It goes through quintessential California beach towns right out of the 1950′s. It has hair-pin turns that have you're convinced you're about to fall into the ocean. It has open farm fields and hundreds of miles of unspoiled and undeveloped land. It's the kind of road you see in car ads and movies, one that looks like it was built to be driven in a Porsche with the top down. The almost 400 mile coast drive from Los Angeles to San Francisco is one the road trips you need to do before you die.

It goes through quintessential California beach towns right out of the 1950′s. It has hair-pin turns that have you're convinced you're about to fall into the ocean. It has open farm fields and hundreds of miles of unspoiled and undeveloped land. It's the kind of road you see in car ads and movies, one that looks like it was built to be driven in a Porsche with the top down. The almost 400 mile coast drive from Los Angeles to San Francisco is one the road trips you need to do before you die.

15 air miles away, the road parallels Silicon Valley (and the 7 million people in the San Francisco Bay Area.) In that 45 mile stretch – from Half Moon Bay to Santa Cruz – there's not a single stoplight and less than 5,000 people.

The Peoples Coast

Yet there's no rational reason most of the 1,100 miles of the California coast should look like this. 33 million Californians live less than an hour from the coast. It's some of the most expensive land in the country. As our economy is organized to extract the maximum revenue and profits from any asset, you wonder why there aren't condos, hotels, houses, shopping centers and freeways, wall-to-wall for most of it's length (except in parts of Southern California where there already is.)

The explanation is that almost 40 years ago the people of California passed Proposition 20 – the Coastal Initiative – and in 1976 the state legislature followed it up by passing the Coastal Act, which created the California Coastal Commission. Essentially the Coastal Commission acts as California's planning commission for all 1,100 miles of the California coast. It has a staff of ~120 who recommend actions to the 12 commissioners (all political appointees) who make the final decisions.

Among other things the legislature said the goals of the Coastal Commission was to: 1) maximize public access to the coast and maximize public recreational opportunities in the coastal zone consistent with sound resources conservation principles and constitutionally protected rights of private property owners. And 2) assure priority for coastal-dependent and coastal-related development over other development on the coast.

You Can Make a Difference

This week I had my public servant hat on in my role as a California Coastal Commissioner.

I don't write about the commission because I want to avoid any conflict in my role as a public official. But today is different. The single individual responsible for running the Commission staff for the last 26 years, it's executive director Peter Douglas, just announced his retirement.

Unlike Robert Moses who built modern New York City's or Baron Haussmann who built 19th century Paris in concrete and steel, the legacy and achievements of Peter Douglas are all the things you don't see in the 1,100 miles of the California coast; wetlands that haven't been filled, public access that hasn't been lost, highly scenic areas that haven't been spoiled and destroyed.

There's an old political science rule of thumb that says regulatory agencies become captured by the industries that they regulate within seven years. Yet for the 26 years of Peter's tenure he's managed to keep the commission independent despite of enormous pressure.

The Commission has been able to stave off the tragedy of the commons for the California coast. Upholding the Coastal Act had it taking unpopular positions upsetting developers who have fought with the agency over seaside projects, homeowners who strongly feel that private property rights unconditionally trump public access and local governments who believe they should have the final say in what's right for their community.

Peter opened the commission up to public participation and promoted citizen activism. He built a world-class staff who understand what public service truly means.

Over the last 40 years the winners have been 37 million Californians and the people who drive down the coast and can't imagine why its looks like it does. In spite of opposition the commission has carried out the public trust.

The coast is never saved, it is always being saved. The work is never finished. The pressure to develop it is relentless, and it can be paved over with a thousand small decisions. I hope our children don't look back at pictures of the California coast and wistfully say, "look what our parents lost."

As commissioners it's our job to choose Peter's replacement. Hopefully we'll have the wisdom in finding a worthy successor. The people of California and their children deserve as much.

Godspeed Peter Douglas.

Filed under: California Coastal Commission

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers