Steve Blank's Blog, page 2

April 15, 2025

How the U.S. Became A Science Superpower

Prior to WWII the U.S was a distant second in science and engineering. By the time the war was over, U.S. science and engineering had blown past the British, and led the world for 85 years.

It happened because two very different people were the science advisors to their nation’s leaders. Each had radically different views on how to use their country’s resources to build advanced weapon systems. Post war, it meant Britain’s early lead was ephemeral while the U.S. built the foundation for a science and technology innovation ecosystem that led the world – until now.

The British – Military Weapons Labs

When Winston Churchill became the British prime minister in 1940, he had at his side his science advisor, Professor Frederick Lindemann, his friend for 20 years. Lindemann headed up the physics department at Oxford and was the director of the Oxford Clarendon Laboratory. Already at war with Germany, Britain’s wartime priorities focused on defense and intelligence technology projects, e.g. weapons that used electronics, radar, physics, etc. – a radar-based air defense network called Chain Home, airborne radar on night fighters, and plans for a nuclear weapons program – the MAUD Committee which started the British nuclear weapons program code-named Tube Alloys. And their codebreaking organization at Bletchley Park was starting to read secret German messages – the Enigma – using the earliest computers ever built.

As early as the mid 1930s, the British, fearing Nazi Germany, developed prototypes of these weapons using their existing military and government research labs. The Telecommunications Research Establishment built early-warning Radar, critical to Britain’s survival during the Battle of Britain, and electronic warfare to protect British bombers over Germany. The Admiralty Research Lab built Sonar and anti-submarine warfare systems. The Royal Aircraft Establishment was developing jet fighters. The labs then contracted with British companies to manufacture the weapons in volume. British government labs viewed their universities as a source of talent, but they had no role in weapons development.

Under Churchill, Professor Lindemann influenced which projects received funding and which were sidelined. Lindemann’s WWI experience as a researcher and test pilot on the staff of the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough gave him confidence in the competence of British military research and development labs. His top-down, centralized approach with weapons development primarily in government research labs shaped British innovation during WW II – and led to its demise post-war.

The Americans – University Weapons Labs

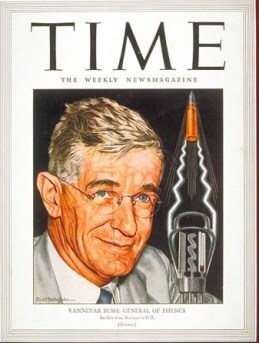

Unlike Britain, the U.S. lacked a science advisor. It wasn’t until June 1940, that Vannevar Bush, ex-MIT dean of engineering, told President Franklin Roosevelt that World War II would be the first war won or lost on the basis of advanced technology electronics, radar, physics problems, etc.

Unlike Lindemann, Bush had a 20-year-long contentious history with the U.S. Navy and a dim view of government-led R&D. Bush contended that the government research labs were slow and second rate. He convinced the President that while the Army and Navy ought to be in charge of making conventional weapons – planes, ships, tanks, etc. — scientists from academia could develop better advanced technology weapons and deliver them faster than Army and Navy research labs. And he argued the only way the scientists could be productive was if they worked in a university setting in civilian-run weapons labs run by university professors. To the surprise of the Army and Navy Service chiefs, Roosevelt agreed to let Bush build exactly that organization to coordinate and fund all advanced weapons research.

Unlike Lindemann, Bush had a 20-year-long contentious history with the U.S. Navy and a dim view of government-led R&D. Bush contended that the government research labs were slow and second rate. He convinced the President that while the Army and Navy ought to be in charge of making conventional weapons – planes, ships, tanks, etc. — scientists from academia could develop better advanced technology weapons and deliver them faster than Army and Navy research labs. And he argued the only way the scientists could be productive was if they worked in a university setting in civilian-run weapons labs run by university professors. To the surprise of the Army and Navy Service chiefs, Roosevelt agreed to let Bush build exactly that organization to coordinate and fund all advanced weapons research.

(While Bush had no prior relationship with the President, Roosevelt had been the Assistant Secretary of the Navy during World War I and like Bush had seen first-hand its dysfunction. Over the next four years they worked well together. Unlike Churchill, Roosevelt had little interest in science and accepted Bush’s opinions on the direction of U.S. technology programs, giving Bush sweeping authority.)

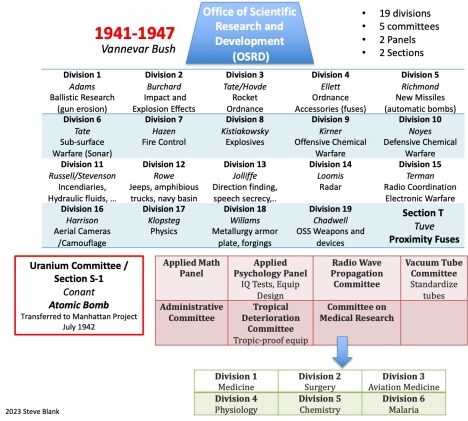

In 1941, Bush upped the game by convincing the President that in addition to research, development, acquisition and deployment of these weapons also ought to be done by professors in universities. There they would be tasked to develop military weapons systems and solve military problems to defeat Germany and Japan. (The weapons were then manufactured in volume by U.S. corporations Western Electric, GE, RCA, Dupont, Monsanto, Kodak, Zenith, Westinghouse, Remington Rand and Sylvania.) To do this Bush created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSR&D).

OSR&D headquarters divided the wartime work into 19 “divisions,” 5 “committees,” and 2 “panels,” each solving a unique part of the military war effort. There were no formal requirements.

Staff at OSRD worked with their military liaisons to understand what the most important military problems were and then each OSR&D division came up with solutions. These efforts spanned an enormous range of tasks – the development of advanced electronics, radar, rockets, sonar, new weapons like the proximity fuse, Napalm, the Bazooka and new drugs such as penicillin, cures for malaria, chemical warfare, and nuclear weapons.

Staff at OSRD worked with their military liaisons to understand what the most important military problems were and then each OSR&D division came up with solutions. These efforts spanned an enormous range of tasks – the development of advanced electronics, radar, rockets, sonar, new weapons like the proximity fuse, Napalm, the Bazooka and new drugs such as penicillin, cures for malaria, chemical warfare, and nuclear weapons.

Each division was run by a professor hand-picked by Bush. And they were located in universities – MIT, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Caltech, Columbia and the University of Chicago all ran major weapons systems programs. Nearly 10,000 scientists and engineers, professors and their grad students received draft deferments to work in these university labs.

Americans – Unlimited Dollars

What changed U.S. universities, and the world forever, was government money. Lots of it. Prior to WWII most advanced technology research in the U.S. was done in corporate innovation labs (GE, AT&T, Dupont, RCA, Westinghouse, NCR, Monsanto, Kodak, IBM, et al.) Universities had no government funding (except for agriculture) for research. Academic research had been funded by non-profits, mostly the Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations and industry. Now, for the first time, U.S. universities were getting more money than they had ever seen. Between 1941 and 1945, OSR&D gave $9 billion (in 2025 dollars) to the top U.S. research universities. This made universities full partners in wartime research, not just talent pools for government projects as was the case in Britain.

The British – Wartime Constraints

Wartime Britain had very different constraints. First, England was under daily attack. They were being bombed by air and blockaded by submarines, so it was logical that they focused on a smaller set of high-priority projects to counter these threats. Second, the country was teetering on bankruptcy. It couldn’t afford the broad and deep investments that the U.S. made. (Illustrated by their abandonment of their nuclear weapons programs when they realized how much it would cost to turn the research into industrial scale engineering.) This meant that many other areas of innovation—such as early computing and nuclear research—were underfunded compared to their American counterparts.

They were being bombed by air and blockaded by submarines, so it was logical that they focused on a smaller set of high-priority projects to counter these threats. Second, the country was teetering on bankruptcy. It couldn’t afford the broad and deep investments that the U.S. made. (Illustrated by their abandonment of their nuclear weapons programs when they realized how much it would cost to turn the research into industrial scale engineering.) This meant that many other areas of innovation—such as early computing and nuclear research—were underfunded compared to their American counterparts.

Post War – Britain

Churchill was voted out of office in 1945. With him went Professor Lindemann and the coordination of British science and engineering. Britain would be without a science advisor until 1951-55 when Churchill returned for a second term and brought back Lindemann with him.

The end of the war led to extreme downsizing of the British military including severe cuts to all the government labs that had developed Radar, electronics, computing, etc.

With post-war Britain financially exhausted, post-war austerity limited its ability to invest in large-scale innovation. There were no post-war plans for government follow-on investments. The differing economic realities of the U.S. and Britain also played a key role in shaping their innovation systems. The United States had an enormous industrial base, abundant capital, and a large domestic market, which enabled large-scale investment in research and development. In Britain, a socialist government came to power. Churchill’s successor, Labor’s Clement Attlee, dissolved the British empire, nationalized banking, power and light, transport, and iron and steel, all which reduced competition and slowed technological progress.

While British research institutions like Cambridge and Oxford remained leaders in theoretical science, they struggled to scale and commercialize their breakthroughs. For instance Alan Turing’s and Tommy Flower’s pioneering work on computing at Bletchley Park didn’t turn into a thriving British computing industry—unlike in the U.S., where companies like ERA, Univac, NCR and IBM built on their wartime work.

Without the same level of government support for dual-use technologies or commercialization, and with private capital absent for new businesses, Britain’s post-war innovation ecosystem never took off.

Post War – The U.S.

Meanwhile in the U.S. universities and companies realized that the wartime government funding for research had been an amazing accelerator for science, engineering, and medicine. Everyone, including Congress, agreed that the U.S. government should continue to play a large role in continuing it. In 1945, Vannevar Bush published a report “Science, The Endless Frontier” advocating for government funding of basic research in universities, colleges, and research institutes. Congress argued on how to best organize federal support of science.

By the end of the war, OSR&D funding had taken technologies that had been just research papers or considered impossible to build at scale and made them commercially viable – computers, rockets, radar, Teflon, synthetic fibers, nuclear power, etc. Innovation clusters formed around universities like MIT and Harvard which had received large amounts of OSR&D funding (MIT’s Radiation Lab or “Rad Lab” employed 3,500 civilians during WWII and developed and built 100 radar systems deployed in theater,) or around professors who ran one of the OSR&D divisions – like Fred Terman at Stanford.

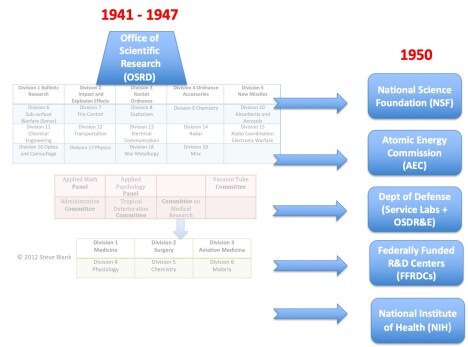

When the war ended, the Atomic Energy Commission spun out of the Manhattan Project in 1946 and the military services took back advanced weapons development. In 1950 Congress set up the National Science Foundation to fund all basic science in the U.S. (except for Life Sciences, a role the new National Institutes of Health would assume.) Eight years later DARPA and NASA would also form as federal research agencies.

Ironically, Vannevar Bush’s influence would decline even faster than Professor Lindemann’s. When President Roosevelt died in April 1945 and Secretary of War Stimson retired in September 1945, all the knives came out from the military leadership Bush had bypassed in the war. His arguments on how to reorganize OSR&D made more enemies in Congress. By 1948 Bush had retired from government service. He would never again play a role in the U.S. government.

Ironically, Vannevar Bush’s influence would decline even faster than Professor Lindemann’s. When President Roosevelt died in April 1945 and Secretary of War Stimson retired in September 1945, all the knives came out from the military leadership Bush had bypassed in the war. His arguments on how to reorganize OSR&D made more enemies in Congress. By 1948 Bush had retired from government service. He would never again play a role in the U.S. government.

Divergent Legacies

Britain’s focused, centralized model using government research labs was created in a struggle for short-term survival. They achieved brilliant breakthroughs but lacked the scale, integration and capital needed to dominate in the post-war world.

The U.S. built a decentralized, collaborative ecosystem, one that tightly integrated massive government funding of universities for research and prototypes while private industry built the solutions in volume.

A key component of this U.S. research ecosystem was the genius of the indirect cost reimbursement system. Not only did the U.S. fund researchers in universities by paying the cost of their salaries, the U.S. gave universities money for the researchers facilities and administration. This was the secret sauce that allowed U.S. universities to build world-class labs for cutting-edge research that were the envy of the world. Scientists flocked to the U.S. causing other countries to complain of a “brain drain.”

Today, U.S. universities license 3,000 patents, 3,200 copyrights and 1,600 other licenses to technology startups and existing companies. Collectively, they spin out over 1,100 science-based startups each year, which lead to countless products and tens of thousands of new jobs. This university/government ecosystem became the blueprint for modern innovation ecosystems for other countries.

Summary

By the end of the war, the U.S. and British innovation systems had produced radically different outcomes. Both systems were influenced by the experience and personalities of their nations science advisor.

December 3, 2024

How to Flip the Script, Beat China and Russia – And Fix the Broken Department of Defense

A version of this post previously appeared in War on the Rocks. This version has been updated with suggestions from leaders across the Department of Defense and Venture Capital community.

BLUF: In WW II, the U.S. outsourced advanced weapons systems development to civilians. The weapons they developed won the war. It’s time to do that again. This new administration can make it happen.

“The coming war is going to be a technology war. The country’s top innovators feel that there is a huge disconnect between what the U.S. military ecosystem can produce and what’s possible if we engaged civilians to develop weapon systems for critical technologies. The U.S. military has little idea of what civilians could provide in the event of war, and civilians are wholly in the dark as to what the military needs. As a result, we believe the U.S. is woefully unprepared and ill-equipped for a war driven by advanced technology.

The only solution is to outsource advanced weapons systems development outside of the traditional services and government ecosystem and hand the development to civilians.”

Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt in 1940

Insane?

President Roosevelt agreed, making a series of decisions that, without which, the Allies may have lost World War II.

The U.S. outsourced advanced weapons systems development and acquisition in 1941. Within three years this gave the U.S a stream of advanced weapons – radar, electronic warfare, proximity fuses, rockets, anti-submarine warfare, and nuclear weapons – all instrumental in our victory in World War II.

We need to do it again. The incoming Trump administration has a historic, once-in-a-century opportunity to do something similar today and give the United States a stream of advanced capabilities and weapons that will allow the United States to deter Russia and China or — failing that — defeat them in a war.

Here’s how.

Why Radical Change is Needed Now

It’s abundantly clear that the U.S. defense ecosystem is being challenged by the proliferation of commercial technology, hobbled by its legacy systems and prime contractors, and sabotaged by its own Acquisition system, rendering it unable to keep pace with threats to the nation.

Simultaneously, the rise of defense-oriented startups and venture capital firms have proven that a commercial ecosystem is more than capable of rapid delivery of most of the advanced weapons needed to deter or win a war. Companies like SpaceX, Anduril, Palantir, Saronic, Vannevar Labs, et al have proven they can deliver at speeds unmatched by existing contractors. Defense and dual-use venture capital firms like Shield Capital, General Catalyst, a16z, DCVC, 8VC, et al, have stepped up to fund this ecosystem, collectively investing tens of billions in new defense technologies.

But the Department of Defense is organized for a world it wishes it still had but no longer exists. Unfortunately our adversaries no longer allow us that freedom. While there have been innovative DoD experiments in innovation (Defense Innovation Unit and its Replicator initiative, Collaborative Combat Aircraft, and the Office of Strategic Capital, etc.), these new structures and initiatives do not yet have the scale required to meet the level of change required. Meanwhile, the overall glacial pace of acquisition and the capture of the status quo by the few prime contractors threatens our nation. In a perfect world, a bipartisan Congress would reorganize the Defense Department to integrate with this new wave of private companies and capital.

But that isn’t politically feasible in the time America has left to prepare for the possibility of major war, which may be as little as a few years. That’s where Vannevar Bush’s insights are critical for the present day.

We are out of time.

The U.S. needs to relearn the lessons that worked to win a World War and outsource advanced weapons systems development to private industry in areas that startups and scale-ups already lead or could move faster in: AI, drones, space, biotech, networking, cyber …

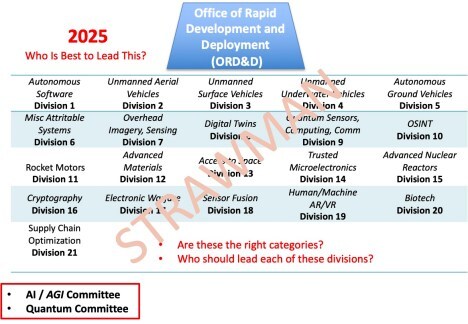

The Trump administration should create the Office of Rapid Development and Deployment (ORDD) modeled after the WW II’s Office of Science, Research and Development (OSRD.) This could build on the existing Defense Innovation Unit which is already taking many of the right steps, albeit with dramatically greater scale and autonomy as described below.

This new office would be responsible for things that are attritable, software, and have lifecycles of 3-10 years.It would outsource these to private industry focused on specific problems with speed and innovation.This office would have authority to define and issue “prototype” requirements on behalf of the Combatant CommandsThe Combatant Commands could buy directly from this office.The office would anticipate Combatant Commands needs via embeds, to observe, investigate and prioritize their critical problems.It would also be empowered to select solutions – not on lowest cost but best and fastest solution to deploymentThe office would have an independent and reliable budget for large scale Acquisition ~15% of the DoD RDT&E budgetThe office would be staffed with civilian and military talent commensurate with that budget, and with the ability to circumvent bureaucratic barriers to hiringWinning solutions would be supported with guaranteed production contracts to ensure swift deliveryThe office would take responsibility for integration and overall system strategy, managing how these systems are deployed, fielded, and supportedMajor defense contractors would be incentivized to partner with them – as providers of exquisite subsystems/kinetics, integrators or even as acquirers (Tax incentives could be offered to encourage the deployment and fielding of these solutions)For example, a collaboration between a traditional defense prime contractor like Lockheed Martin and a newer technology company like Anduril could generate significant synergies.The services would still be responsible for long term acquisition programs requiring a formal budgeting processes, extended supply chains, and decades of support.Primes would remain the main suppliers here – building exquisite systems that require complex integration and decades of support.We’d be ruthless in going through the portfolios of our military research labs and federally funded research centers, eliminating projects that the private sector can already handle effectivelyThese institutions would then be free to concentrate on tasks the private sector cannot address, such as fundamental research, advanced weapon systems, and programs requiring timelines of 10 years or moreGoals of an Office of Rapid Development and Deployment (ORDD)

The success of the “Office of Rapid Development and Deployment (ORDD)” will depend on a combination of clear goals, unprecedented collaboration, resource commitment, and the effective integration of the commercial ecosystem to rapidly solve practical military challenges with speed and precision.

Who Should Lead this Office?

Appoint a head of this office who is – or could become – a trusted advisor of President Trump, deeply understands technology, can look across VC portfolios and select the best domain experts, has a problem-solving mindset and is a charismatic leader.

Who fits this description? Not many. The only candidates I can think of are Elon Musk, Trae Stephens, Stephen Feinberg, Raj Shah, Mike Brown and Doug Beck.

A Once-in-a-Century Opportunity

The stakes have never been higher, and the path ahead demands the audacity of visionaries who can break free from the inertia of the status quo. Just as Vannevar Bush once harnessed the ingenuity of America’s best minds to outpace the enemies of his time, we now face a moment of similar urgency and promise. If the United States can empower its boldest innovators to lead, not as bureaucrats but as pioneers of rapid technological dominance, we can secure not just victory in the wars of tomorrow but the preservation of the values that make our nation worth defending.

The future hinges on our ability to act decisively, to embrace radical change, and to once again make history — not by clinging to the comforts of tradition but by seizing the opportunities of transformation. This is not merely a call to action; it is a rallying cry for a nation that must once again trust its greatest minds to deliver when it matters most.

October 22, 2024

Quantum Computing – An Update

In March 2022 I wrote a description of the Quantum Technology Ecosystem. I thought this would be a good time to check in on the progress of building a quantum computer and explain more of the basics.

Just as a reminder, Quantum technologies are used in three very different and distinct markets:  Quantum Computing, Quantum Communications and Quantum Sensing and Metrology. If you don’t know the difference between a qubit and cueball, (I didn’t) read the tutorial here.

Quantum Computing, Quantum Communications and Quantum Sensing and Metrology. If you don’t know the difference between a qubit and cueball, (I didn’t) read the tutorial here.

Summary –

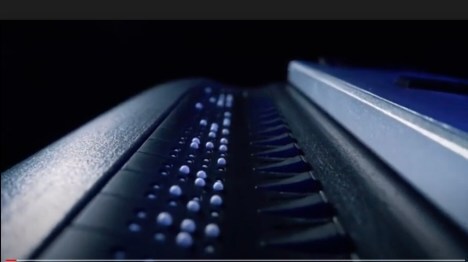

There’s been incremental technical progress in making physical qubitsThere is no clear winner yet between the seven approaches in building qubitsReminder – why build a quantum computer?How many physical qubits do you need?Advances in materials science will drive down error ratesRegional research consortiumsVenture capital investment FOMO and financial engineeringWe talk a lot about qubits in this post. As a reminder a qubit – is short for a quantum bit. It is a quantum computing element that leverages the principle of superposition (that quantum particles can exist in many possible states at the same time) to encode information via one of four methods: spin, trapped atoms and ions, photons, or superconducting circuits.

Incremental Technical Progress

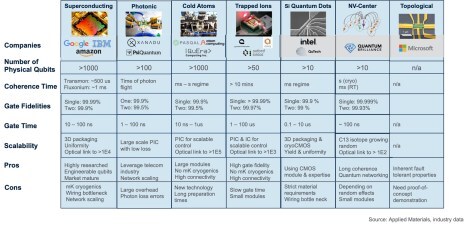

As of 2024 there are seven different approaches being explored to build physical qubits for a quantum computer. The most mature currently are Superconducting, Photonics, Cold Atoms, Trapped Ions. Other approaches include Quantum Dots, Nitrogen Vacancy in Diamond Centers, and Topological. All these approaches have incrementally increased the number of physical qubits.

These multiple approaches are being tried, as there is no consensus to the best path to building logical qubits. Each company believes that their technology approach will lead them to a path to scale to a working quantum computer.

Every company currently hypes the number of physical qubits they have working. By itself this is a meaningless number to indicate progress to a working quantum computer. What matters is the number of logical qubits.

Reminder – Why Build a Quantum Computer?

One of the key misunderstandings about quantum computers is that they are faster than current classical computers on all applications. That’s wrong. They are not. They are faster on a small set of specialized algorithms. These special algorithms are what make quantum computers potentially valuable. For example, running Grover’s algorithm on a quantum computer can search unstructured data faster than a classical computer. Further, quantum computers are theoretically very good at minimization / optimizations /simulations…think optimizing complex supply chains, energy states to form complex molecules, financial models (looking at you hedge funds,) etc.

However, while all of these algorithms might have commercial potential one day, no one has yet to come up with a use for them that would radically transform any business or military application. Except for one – and that one keeps people awake at night. It’s Shor’s algorithm for integer factorization – an algorithm that underlies much of existing public cryptography systems.

The security of today’s public key cryptography systems rests on the assumption that breaking into those keys with a thousand or more digits is practically impossible. It requires factoring large prime numbers (e.g., RSA) or elliptic curve (e.g., ECDSA, ECDH) or finite fields (DSA) that can’t be done with any type of classic computer regardless of how large. Shor’s factorization algorithm can crack these codes if run on a Quantum Computer. This is why NIST has been encouraging the move to Post-Quantum / Quantum-Resistant Codes.

How many physical qubits do you need for one logical qubit?

Thousands of logical qubits are needed to create a quantum computer that can run these specialized applications. Each logical qubit is constructed out of many physical qubits. The question is, how many physical qubits are needed? Herein lies the problem.

Unlike traditional transistors in a microprocessor that once manufactured always work, qubits are unstable and fragile. They can pop out of a quantum state due to noise, decoherence (when a qubit interacts with the environment,) crosstalk (when a qubit interacts with a physically adjacent qubit,) and imperfections in the materials making up the quantum gates. When that happens errors will occur in quantum calculations. So to correct for those error you need lots of physical qubits to make one logical qubit.

So how do you figure out how many physical qubits you need?

You start with the algorithm you intend to run.

Different quantum algorithms require different numbers of qubits. Some algorithms (e.g., Shor’s prime factoring algorithm) may need >5,000 logical qubits (the number may turn out to be smaller as researchers think of how to use fewer logical qubits to implement the algorithm.)

Other algorithms (e.g., Grover’s algorithm) require fewer logical qubits for trivial demos but need 1000’s of logical qubits to see an advantage over linear search running on a classical computer. (See here, here and here for other quantum algorithms.)

Measure the physical qubit error rate.

Therefore, the number of physical qubits you need to make a single logical qubit starts by calculating the physical qubit error rate (gate error rates, coherence times, etc.) Different technical approaches (superconducting, photonics, cold atoms, etc.) have different error rates and causes of errors unique to the underlying technology.

Current state-of-the-art quantum qubits have error rates that are typically in the range of 1% to 0.1%. This means that on average one out of every 100 to one out of 1000 quantum gate operations will result in an error. System performance is limited by the worst 10% of the qubits.

Choose a quantum error correction code

To recover from the error prone physical qubits, quantum error correction encodes the quantum information into a larger set of physical qubits that are resilient to errors. Surface Codes is the most commonly proposed error correction code. A practical surface code uses hundreds of physical qubits to create a logical qubit. Quantum error correction codes get more efficient the lower the error rates of the physical qubits. When errors rise above a certain threshold, error correction fails, and the logical qubit becomes as error prone as the physical qubits.

The Math

To factor a 2048-bit number using Shor’s algorithm with a 10-2 (1% per physical qubit) error rate:

Assume we need ~5,000 logical qubitsWith an error rate of 1% the surface error correction code requires ~ 500 physical qubits required to encode one logical qubit. (The number of physical qubits required to encode one logical qubit using the Surface Code depends on the error rate.)Physical cubits needed for Shor’s algorithm= 500 x 5,000 = 2.5 millionIf you could reduce the error rate by a factor of 10 – to 10-3 (0.1% per physical qubit,)

Because of the lower error rate, the surface code would only need ~ 100 physical qubits to encode one logical qubitPhysical cubits needed for Shor’s algorithm= 100 x 5,000 = 500 thousandIn reality there another 10% or so of ancillary physical bits needed for overhead. And no one yet knows the error rate in wiring multiple logical bits together via optical links or other technologies.

(One caveat to the math above. It assumes that every technical approach (Superconducting, Photonics, Cold Atoms, Trapped Ions, et al) will require each physical qubit to have hundreds of bits of error correction to make a logical qubit. There is always a chance a breakthrough could create physical qubits that are inherently stable, and the number of error correction qubits needed drops substantially. If that happens, the math changes dramatically for the better and quantum computing becomes much closer.)

Today, the best anyone has done is to create 1,000 physical qubits.

We have a ways to go.

Advances in materials science will drive down error rates

As seen by the math above, regardless of the technology in creating physical qubits (Superconducting, Photonics, Cold Atoms, Trapped Ions, et al.) reducing errors in qubits can have a dramatic effect on how quickly a quantum computer can be built. The lower the physical qubit error rate, the fewer physical qubits needed in each logical qubit.

The key to this is materials engineering. To make a system of 100s of thousands of qubits work the qubits need to be uniform and reproducible. For example, decoherence errors are caused by defects in the materials used to make the qubits. For superconducting qubits that requires uniform thickness, controlled grain size, and roughness. Other technologies require low loss, and uniformity. All of the approaches to building a quantum computer require engineering exotic materials at the atomic level – resonators using tantalum on silicon, Josephson junctions built out of magnesium diboride, transition-edge sensors, Superconducting Nanowire Single Photon Detectors, etc.

Materials engineering is also critical in packaging these qubits (whether it’s superconducting or conventional packaging) and to interconnect 100s of thousands of qubits, potentially with optical links. Today, most of the qubits being made are on legacy 200mm or older technology in hand-crafted processes. To produce qubits at scale, modern 300mm semiconductor technology and equipment will be required to create better defined structures, clean interfaces, and well-defined materials. There is an opportunity to engineer and build better fidelity qubits with the most advanced semiconductor fabrication systems so the path from R&D to high volume manufacturing is fast and seamless.

There are likely only a handful of companies on the planet that can fabricate these qubits at scale.

Regional research consortiums

Two U.S. states; Illinois and Colorado are vying to be the center of advanced quantum research.

Illinois Quantum and Microelectronics Park (IQMP)

Illinois has announced the Illinois Quantum and Microelectronics Park initiative, in collaboration with DARPA’s Quantum Proving Ground (QPG) program, to establish a national hub for quantum technologies. The State approved $500M for a “Quantum Campus” and has received $140M+ from DARPA with the state of Illinois matching those dollars.

Elevate Quantum

Elevate Quantum is the quantum tech hub for Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming. The consortium was awarded $127m from the Federal and State Governments – $40.5 million from the Economic Development Administration (part of the Department of Commerce) and $77m from the State of Colorado and $10m from the State of New Mexico.

(The U.S. has a National Quantum Initiative (NQI) to coordinate quantum activities across the entire government see here.)

Venture capital investment, FOMO, and financial engineering

Venture capital has poured billions of dollars into quantum computing, quantum sensors, quantum networking and quantum tools companies.

However, regardless of the amount of money raised, corporate hype, pr spin, press releases, public offerings, no company is remotely close to having a quantum computer or even being close to run any commercial application substantively faster than on a classical computer.

So why all the investment in this area?

FOMO – Fear Of Missing Out. Quantum is a hot topic. This U.S. government has declared quantum of national interest. If you’re a deep tech investor and you don’t have one of these companies in your portfolio it looks like you’re out of step.It’s confusing. The possible technical approaches to creating a quantum computer – Superconducting, Photonics, Cold Atoms, Trapped Ions, Quantum Dots, Nitrogen Vacancy in Diamond Centers, and Topological – create a swarm of confusing claims. And unless you or your staff are well versed in the area, it’s easy to fall prey to the company with the best slide deck.Financial engineering. Outsiders confuse a successful venture investment with companies that generate lots of revenue and profit. That’s not always true.Often, companies in a “hot space” (like quantum) can go public and sell shares to retail investors who have almost no knowledge of the space other than the buzzword. If the stock price can stay high for 6 months the investors can sell their shares and make a pile of money regardless of what happens to the company.

The track record so far of quantum companies who have gone public is pretty dismal. Two of them are on the verge of being delisted.

Here are some simple questions to ask companies building quantum computers:

What is their current error rates?What error correction code will they use?Given their current error rates, how many physical qubits are needed to build one logical qubit?How will they build and interconnect the number of physical qubits at scale?What number of qubits do they think is need to run Shor’s algorithm to factor 2048 bits.How will the computer be programmed? What are the software complexities?What are the physical specs – unique hardware needed (dilution cryostats, et al) power required, connectivity, etc.Lessons Learned

Lots of companiesLots of investmentGreat engineering occurringImprovements in quantum algorithms may add as much (or more) to quantum computing performance as hardware improvementsThe winners will be the one who master material engineering and interconnectsJury is still out on all bets

October 8, 2024

How Saboteurs Threaten Innovation–and What to Do About It

This article first appeared in First Round Review.

“Only the Paranoid Survive”

Andy Grove – Intel CEO 1987-1998

I just had an urgent “can we meet today?” coffee with Rohan, an ex-student. His three-year-old startup had been slapped with a notice of patent infringement from a Fortune 500 company. “My lawyers said defending this suit could cost $500,000 just for discovery, and potentially millions of dollars if it goes to trial. Do you have any ideas?”

The same day, I got a text from Jared, a friend who’s running a disruptive innovation organization inside the Department of Defense. He just learned that their incumbent R&D organization has convinced leadership they don’t need any outside help from startups or scaleups.

Sigh….

Rohan and Jared have learned three valuable lessons:

Only the paranoid survive (as Andy Grove put it)If you’re not losing sleep over who wants to kill you, you’re going to die.The best fight is the one you can avoid.It’s a reminder that innovators need to be better prepared about all the possible ways incumbents sabotage innovation.

Innovators often assume that their organizations and industry will welcome new ideas, operating concepts and new companies. Unfortunately, the world does not unfold like business school textbooks.

Whether you’re a new entrant taking on an established competitor or you’re trying to stay scrappy while operating within a bigger company here’s what you need to know about how incumbents will try to stand in your way – and what you can do about it.

Entrepreneurs versus Saboteurs

Entrepreneurs versus Saboteurs

Startups and scaleups outside of companies or government agencies want to take share of an existing market, or displace existing vendors. Or if they have a disruptive technology or business model, they want to create a new capability or operating concept – even creating a new market.

As my student Rohan just painfully learned, the incumbent suppliers and existing contractors want to kill these new entrants. They have no intention of giving up revenue, profits and jobs. (In the government, additional saboteurs can include Congressional staffers, Congressman and lobbyists, as these new entrants threaten campaign contributions and jobs in local districts.)

Intrapreneurs versus Saboteurs

Innovators inside of companies or government agencies want to make their existing organization better, faster, more effective, more profitable, more responsive to competitive threats or to adversaries. They might be creating or advocating for a better version of something that exists. Or perhaps they are trying to create something disruptive that never existed before.

Inside these commercial or government organizations there are people who want to kill innovation (as my friend Jared just discovered). These can be managers of existing programs, or heads of engineering or R&D organizations who are feeling threatened by potential loss of budget and authority. Most often, budgets and headcount are zero-sum games so new initiatives threaten the status quo.

Leaders of existing organizations often focus on the success of their department or program rather than the overall good of the organization. And at times there are perverse incentives as some individuals are aligned with the interests of incumbent vendors rather than the overall good of the company or government agency.

How Do incumbents Kill Innovation?

Rohan and Jared were each dealing with one form of innovation sabotage. Incumbents use a variety of ways to sabotage and kill innovative ideas inside of organizations and outside new companies. And most of the time innovators have no idea what just hit them. And those that do – like Rohan and Jared – have no game plan in place to respond.

Here are the most common methods of sabotage that I’ve seen, followed by a few suggestions on how to prepare and defend against them.

Founders and Innovators should expect that existing organizations and companies will defend their turf – ferociously.

Common ways incumbents kill innovation in both commercial markets and government agencies.Create career FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt). Positioning the innovative idea, product or service as risk to the career of whoever adopts or champions it.Emphasize the risk to existing legacy investments, like the cost of switching to the new product or service or highlighting the users who would object to it.Claim that an existing R&D or engineering organization is already doing it (0r can do it better/cheaper.)Create innovation theater by starting internal innovation programs with the existing staff and processes.Set up committees and advisory boards to “study” the problem. Appoint well respected members of the status quo.Poison funding for internal initiatives. Claiming that you’ll have to kill important program x or y to pay for the new initiative. Or funding the demo of the new idea and then “slow-walk” the budget for scale.File Lawsuits/Protests against winners of contracts.Use patents as a weapon. Filing patent infringement lawsuits – whether true or not. Try to invalidate existing patents – whether true or not.Claim that employees have stolen IP from their previous employer.File HR Complaints against internal intrapreneurs for cutting corners or breaking rules.Isolate senior leadership from the innovators inside the organization via reporting hierarchy and controlling information about alternatives.Object to structures and processes for the rapid adoption of new technologies. Treat innovation and execution as the same processes. Lack tolerance for failure at innovation. Do not cultivate a culture of urgency. Don’t offer a a structured career path for innovators.Lock-up critical resources, like materials, components, people, law firms, distribution channels, partners and make them unavailable to innovation groups/startups.Control industry/government standards to ensure that they are lock-in’s for incumbents.Acquire a startup and shut it down or bury its productPoach talent from an innovation organization or company by convincing talent that the innovation effort won’t go anywhere.Influence “independent” analysts, market research firms with “research” contracts to prove that the market is too small.Confuse buyers and senior leadership by preannouncing products or products that never ship – vaporware.Bundle products (Microsoft Office)Long term lock-in contracts for commercial customers or sole-source for government programs (e.g. F-35).How incumbents kill startups in government marketsFile contract appeals or protests, creating delays that burn cash for new entrants.File Inspector General (IG) complaints, claiming innovators are cutting corners, breaking rules or engaging in illegal hiring and spending. If possible, capture these IG offices and weaponize them against innovators.Hijack the acquisition system by creating requirements written for incumbents, while setting unnecessary standards, barriers and paperwork for new entrants. Ignore requirements to investigate alternate suppliers and issue contracts to the incumbents.Revolving door. The implicit promise of jobs to government program executives and managers and the implicit promise of jobs to congressional staffers and congressmen.Lobbying. Incumbents have dedicated staffs to shape requirements and budgets for their products, as well as dedicated staff for continual facetime in Washington. They are experts at managing the POM, PPBE, House and Senate Armed Services Committees and appropriations committees.Create career risks for innovators attempting to gain support outside of official government channels, penalizing unofficial contacts with members of Congress or their staffs.Create Proprietary interfacesWeaponize security clearances, delaying or denying access to needed secure information, or even pulling your, or your company’s clearance.How incumbents kill startups in commercial markets.Rent Seeking via regulatory bodies (e.g. FCC, SEC, FTC, FAA, Public Utility, Taxi/Insurance Commissions, School Boards, etc, …) Use government regulation to keep out new entrants who have more innovative business models (or delay them so the incumbents can catch up).Rent Seeking via local, state and federal laws (e.g. occupational licensing, car dealership laws, grants, subsidies, or tariff protection). Use arguments – from public safety, to lack of quality, or loss of jobs – to lobby against the new entrants.Rent Seeking via courts to tie up and exhaust a startup’s limited financial resources.Rent Seeking via proprietary interfaces (e.g. John Deere tractor interfaces…)Poison startup financing sources. Telling VCs the incumbents already own the market. Tell Government funders the company is out of cash.Legal kickbacks, like discounts, SPIFs, Co-advertising (e.g. Intel and Microsoft for x86 processors/Windows).State Attorney General complaints to tie up startup resourcesCreate fake benchmark groups or greenwash groups to prove existing solution is better or that new solution is worse.Innovators Survival Checklist

There is no magic bullet I could have offered Rohan or Jared to defend against every possible move an incumbent might make. However, if they had realized that incumbents wouldn’t welcome them, they (and you) might have considered the suggestions below on how to prepare for innovation saboteurs.

In both government and commercial markets:

Map the order of battle. Understand how the money flows and who controls budget, headcount and organizational design. Understand who has political, regulator, leadership influence and where they operate.Understand saboteurs and their motivation. Co-opt them. Turn them into advocates – (this works with skeptics). Isolate them – with facts. Get them removed from their job (preferably by promoting them to another area.)Build an insurgent team. A technologist, visionary, champion, allies, proxies, etc. The insurgency grows over time.Avoid publicly belittling incumbents. Do not say, “They don’t get it.” That will embarrass, infuriate and ultimately motivate them to put you out of business.Avoid early slideware. Instead focus on delivering successful minimal viable products which demonstrate feasibility and a validated requirement.Build evidence of your technical, managerial and operational excellence. Build Minimal Viable Products (MVPs) that illustrate that you understand a customer or stakeholders problem, have the resources to solve it, and a path to deployment.If possible, communicate and differentiate your innovation as incremental innovation. Point out that over time it’s disruptive.Go after rapid scale of a passionate customer who values the disruption e.g. INDOPACOM; or Uber and Airbnb, Tesla in the commercial worldAlly with larger partners who see you as a way to break the incumbents’ lock on the market. i.e. Palantir and the intelligence agencies versus the Army and in industry, IBM’s i2, / Textron Systems Overwatch.In commercial markets:Figure out an “under the radar” strategy that doesn’t attract incumbents’ lawsuits, regulations or laws when you have limited resources to fight back.Patent strategy. Build a defensive patent portfolio and strategy? And consider an offensive one, buying patents you think incumbents may infringe.Pick early markets where the rent seekers are weakest and scale. For example, pick target markets with no national or state lobbying influence. i.e. Craigslist versus newspapers, Netflix versus video rental chains, Amazon versus bookstores, etc.When you get scale and raise a large financing round, take the battle to the incumbents. Strategies at this stage include hiring your own lobbyists, or working with peers in your industry to build your own influence and political action groups.Jared is still trying to get senior leadership to understand that the clock is ticking, and internal R&D efforts and current budget allocation won’t be sufficient or timely. He’s building a larger coalition for change, but the inertia for the status quo is overwhelming.

Rohan’s company was lucky. After months of scrambling (and tens of thousands of dollars), they ended up buying a patent portfolio from a defunct startup and were able to use it to convince the Fortune 500 company to drop their lawsuit.

I hope they both succeed.

What have you found to be effective in taking on incumbents?

October 5, 2024

What Does Product Market Fit Sound Like? This.

I got a call from an ex-student asking me “how do you know when you found product market fit?”

There’s been lots of words written about it, but no actual recordings of the moment.

I remembered I had saved this 90 second, 26 year-old audio file because this is when I knew we had found it at Epiphany.

The speaker was the the Chief Financial Officer of a company called Visio, subsequently acquired by Microsoft

I played it for her and I think it provided some clarity.

https://steveblank.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/NIEL.wavIt’s worth a listen.

If you can’t hear the audio click here

September 17, 2024

How To Find Your Customer In the Dept of Defense – The Directory of DoD Program Executive Offices

Finding a customer for your product in the Department of Defense is hard: Who should you talk to? How do you get their attention?

Looking for DoD customers

How do you know if they have money to spend on your product?

It almost always starts with a Program Executive Office.

The Department of Defense (DoD) no longer owns all the technologies, products and services to deter or win a war – e.g. AI, autonomy, drones, biotech, access to space, cyber, semiconductors, new materials, etc.

Today, a new class of startups are attempting to sell these products to the Defense Department. Amazingly, there is no single DoD-wide phone book available to startups of who to call in the Defense Department.

So I wrote one.

Think of the PEO Directory linked below as a “Who buys in the government?” phone book.

The DoD buys hundreds of billions of dollars of products and services per year, and nearly all of these purchases are managed by Program Executive Offices. A Program Executive Office may be responsible for a specific program (e.g., the Joint Strike Fighter) or for an entire portfolio of similar programs (e.g., the Navy Program Executive Office for Digital and Enterprise Services). PEOs define requirements and their Contracting Officers buy things (handling the formal purchasing, issuing requests for proposals (RFPs), and signing contracts with vendors.) Program Managers (PMs) work with the PEO and manage subsets of the larger program.

Existing defense contractors know who these organizations are and have teams of people tracking budgets and contracts. But startups? Most startups don’t have a clue where to start.

This is a classic case of information asymmetry and it’s not healthy for the Department of Defense or the nascent startup defense ecosystem.

That’s why I put this PEO Directory together.

This first version of the directory lists 75 Program Executive Offices and their Program Executive Officers and Program/Project Managers.

Each Program Executive Office is headed by a Program Executive Officer who is a high ranking official – either a member of the military or a high ranking civilian – responsible for the cost, schedule, and performance of a major system, or portfolio of systems, some worth billions of dollars.

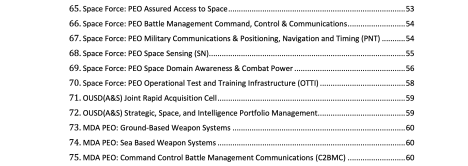

Below is a summary of 75 Program Executive Offices in the Department of Defense.

You can download the full 64-page document of Program Executive Offices and Officers with all 602 names here.

Caveats

Caveats

Do not depend on this document for accuracy or completeness.

It is likely incomplete and contains errors.

Military officers typically change jobs every few years.

Program Offices get closed and new ones opened as needed.

This means this document was out of date the day it was written. Still it represents an invaluable starting point for startups looking to work with DoD.

How to Use The PEO Directory As Part of A Go-To-Market Strategy

While it’s helpful to know what Program Executive Offices exist and who staffs them, it’s even better to know where the money is, what it’s being spent on, and whether the budget is increasing, decreasing, or remaining the same.

The best place to start is by looking through an overview of the entire defense budget here. Then search for those programs in the linked PEO Directory. You can get an idea whether that program has $ Billions, or $ Millions.

Next, take a look at the budget documents released by the DoD Comptroller –

particularly the P-1 (Procurement) and R-1 (R&D) budget documents.

Combining the budget document with this PEO directory helps you narrow down which of the 75 Program Executive Offices and 500+ program managers to call on.

With some practice you can translate the topline, account, or Program Element (PE) Line changes into a sales Go-To-Market strategy, or at least a hypothesis of who to call on.

Armed with the program description (it’s full of jargon and 9-12 months out of date) and the Excel download here and the Appendix here –– you can identify targets for sales calls with DoD where your product has the best chance of fitting in.

The people and organizations in this list change more frequently than the money.

Knowing the people is helpful only after you understand their priorities — and money is the best proxy for that.

Future Work

Ultimately we want to give startups not only who to call on, and who has the money, but which Program Offices are receptive to new entrants. And which have converted to portfolio management, which have tried OTA contracts, as well as highlighting those who are doing something novel with metrics or outcomes.

Going forward this project will be kept updated by the Stanford Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation.

In the meantime send updates, corrections and comments to sblank@stanford.edu

Credit Where Credit Is Due

Clearly, the U.S. government intends to communicate this information. They have published links to DoD organizations here, even listing DoD social media accounts. But the list is fragmented and irregularly updated. Consequently, this type of directory has not existed in a usable format – until now.

August 13, 2024

Security Clearances at the Speed of Startups

Imagine you got a job offer from a company but weren’t allowed to start work – or get paid – for almost a year. And if you can’t pass a security clearance your offer is rescinded. Or you get offered an internship but can’t work on the most interesting part of the project. Sounds like a nonstarter. Well that’s the current process if you want to work for companies or government agencies that work on classified programs.

One Silicon Valley company, Palantir, is trying to change that and shorten the time between getting hired and doing productive work. Here’s why and how.

Over the last five years more of my students have understood that Russia’s brutal war in Ukraine and strategic competition with the People’s Republic of China mean that the world is no longer a stable and safe place. This has convinced many of them to work on national security problems in defense startups.

However, many of those companies and government agencies require you to work on projects with sensitive information the government wants to protect. These are called classified programs. To get hired, and to work on them, you need to first pass a government security clearance. (A security clearance is how the government learns whether you are trustworthy enough to keep secrets and not damage national security.)

For jobs at most defense startups/contractors or national security agencies, instead of starting work with your offer letter, you’d instead receive a “conditional” job offer – that’s a fancy way to say, “we want you to work here, but you need to wait 3 to 9 months without pay until you start, and if you can’t pass the security clearance we won’t hire you.” That’s a pretty high bar for students who have lots of other options for where to work.

Types of Security Clearances

The time it takes for the clearance process depends on the thoroughness and how deeply the government investigates your background. That’s directly related to how classified will be the work you will be doing. The three primary levels of classification (from least to greatest) are Confidential, Secret, and Top Secret.  The type and depth of background investigations to get a security clearance depends on what level of classified information you will be working with. For example, if you just need access to Confidential or Secret material they would do a National Agency Check with Law and Credit (NACLC). The government will look at the FBI’s criminal history repository, do a credit check, and a check with your local law enforcement agencies. This can take a relatively short time (~3 months).

The type and depth of background investigations to get a security clearance depends on what level of classified information you will be working with. For example, if you just need access to Confidential or Secret material they would do a National Agency Check with Law and Credit (NACLC). The government will look at the FBI’s criminal history repository, do a credit check, and a check with your local law enforcement agencies. This can take a relatively short time (~3 months).

On the other hand if you’re going to work on a Top Secret/SCI project, this requires a more extensive (and much longer ~6-9 months) background check called a Single Scope Background Investigation (SSBI). Some types of clearances also require you to take a polygraph (lie-detector) test.

How Does the Government “Clear” you?

The National Background Investigation Services (NBIS) is the government agency that will investigate your background. They will ask about your:

Palantir’s Accelerated Student Clearance Plan

Palantir wants their interns and new hires to hit the ground running and work on the toughest and most interesting government problems from day one. However, these types of problems require having a security clearance. The problem is that today, all companies start an application for a security clearance the day you show up for work.

Palantir’s idea? If you get an internship or full-time offer from Palantir while you’re still in school, they will immediately employ you as a contractor. This will let them start your security clearance process while in school before you show up for work. That means you will be cleared ~9 months later in time for your first day on the job. Think of this like a college early admissions program. (If you’re interning, Palantir will hold your clearance for you if you come back to Palantir the following year.)

Why Do This?

Obviously this is a long-term strategic investment in Palantir’s college talent, but it also affects the entire defense ecosystem – to create a broader team of America’s best engineers who are able to support our country’s most critical missions. And they are encouraging other Defense Tech companies to implement a similar program.

I think it’s a great idea.

Now what are the other innovative ideas Silicon Valley can do to attract a national security workforce?

July 30, 2024

Why Large Organizations Struggle With Disruption, and What to Do About It

Seemingly overnight, disruption has allowed challengers to threaten the dominance of companies and government agencies as many of their existing systems have now been leapfrogged. How an organization reacts to this type of disruption determines whether they adapt or die.

I’ve been working with a large organization whose very existence is being challenged by an onslaught of technology (AI, autonomy, quantum, cyberattacks, access to space, et al) from aggressive competitors, both existing and new. These competitors are deploying these new technologies to challenge the expensive (and until now incredibly effective) legacy systems that this organization has built for decades. (And they are doing it at speed that looks like a blur to this organization.) But the organization is also challenged by the inaction of its own leaders, who cannot let go of the expensive systems and suppliers they built over decades. It’s a textbook case of the Innovators Dilemma.

I’ve been working with a large organization whose very existence is being challenged by an onslaught of technology (AI, autonomy, quantum, cyberattacks, access to space, et al) from aggressive competitors, both existing and new. These competitors are deploying these new technologies to challenge the expensive (and until now incredibly effective) legacy systems that this organization has built for decades. (And they are doing it at speed that looks like a blur to this organization.) But the organization is also challenged by the inaction of its own leaders, who cannot let go of the expensive systems and suppliers they built over decades. It’s a textbook case of the Innovators Dilemma.

In the commercial world creative destruction happens all the time. You get good, you get complacent, and eventually you get punched in the face. The same holds true for Government organizations, albeit with more serious consequences.

This organization’s fate is not yet sealed. Inside it, I’ve watched incredibly innovative groups create autonomous systems and software platforms that rival anything a startup is doing. They’ve found champions in the field organizations, and they’ve run experiments with them. They’ve provided evidence that their organization could adapt to the changing competitive environment and even regain the lead. Simultaneously, they’ve worked with outside organizations to complement and accelerate their internal offerings. They’re on the cusp of a potential transformation – but leadership hesitates to make substantive changes.

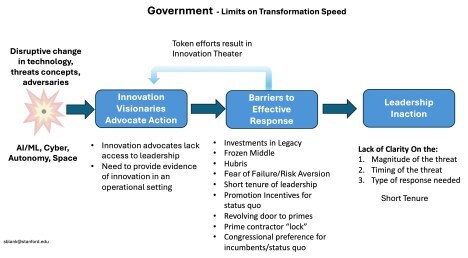

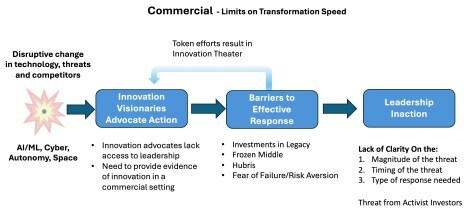

The “Do Nothing” Feedback Loop

I’ve seen this play out time and again in commercial and government organizations. There’s nothing more frustrating for innovators than to watch their organization being disrupted while its senior leaders hesitate to take more than token actions. On the other hand, no one who leads a large organization wants it to go out of business. So, why is adapting to changed circumstances so hard for existing organizations?

The answer starts at the top. Responding to disruption requires action from senior leadership: e.g. the CEO, board, Secretary, etc. Fearful that a premature pivot can put their legacy business or forces at risk, senior leaders delay deciding – often until it’s too late.

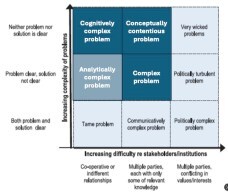

My time with this organization helped me appreciate why adopting and widely deploying something disruptive is difficult and painful in companies and government agencies. Here are the reasons:

Disconnected Innovators – Most leaders of large organizations are not fluent in the new technologies and the disruptive operating concepts/business models they can create. They depend on guidance from their staff and trusted advisors – most of whom have been hired and promoted for their expertise in delivering incremental improvements in existing systems. The innovators in their organization, by contrast, rarely have direct access to senior leaders. Innovators who embrace radically new technologies and concepts that challenge the status quo and dogma are not welcomed, let alone promoted, or funded.

Legacy – The organization I’ve been working with, like many others, has decades of investment in existing concepts, systems, platforms, R&D labs, training, and a known set of external contractors. Building and sustaining their existing platforms and systems has left little money for creating and deploying new ones at the same scale (problems that new entrants/adversaries may not have.) Advocating that one or more of their platforms or systems are at risk or may no longer be effective is considered heresy and likely the end of a career.

The “Frozen Middle” – A common refrain I hear from innovators in large organizations is that too many people are resistant to change (“they just don’t get it”.) After seeing this behavior for decades, I’ve learned that the frozen middle occurs because of what’s called the“Semmelweis effect” – the unconscious tendency of people to stick to preexisting beliefs and reject new ideas that contradict them – because it undermines their established norms and/or beliefs. (They really don’t get it.) This group is most comfortable sticking with existing process and procedures and hires and promotes people who execute the status quo. This works well when the system can continue to succeed with incremental growth, but in the face of more radical change, this normal human reaction shuts out new learning and limits an organizations’ ability to rapidly adapt to new circumstances. The result is organizational blinders and frustrated innovators. And you end up with world-class people and organizations for a world that no longer exists.

Not everyone is affected by the Semmelweis effect. It’s often mid-grade managers / officers in this same “middle” who come up with disruptive solutions and concepts. However, unless they have senior champions (VP’s, Generals / Admirals) and are part of an organization with a mission to solve operational problems, these solutions die. These innovators lack alternate places where the culture encourages and funds experimentation and non-consensus ideas. Ironically, organizations tend to chase these employees out because they don’t conform, or if forced to conform, they grow disillusioned and leave for more innovative work in industry.

Hubris is managerial behavior of overconfidence and complacency. Unlike the unconscious Semmelweis effect, this is an active and conscious denial of facts. It occurs as some leaders/managers believe change threatens their jobs as decision-makers or that new programs, vendors or ideas increase the risk of failure, which may hurt their image and professional or promotional standing.

In the organization I’ve been working with, the internal engineering group offers senior leaders reassurances that they are responding to disruption by touting incremental upgrades to their existing platforms and systems.

Meanwhile because their budget is a zero-sum game, they starve innovators of funds and organizational support for deployment of disruptive new concepts at scale. The result is “innovation theater.” In the commercial world this behavior results in innovation demos but no shipping products and a company on the path to irrelevance or bankruptcy. In the military it’s demos but no funding for deployments at scale.

Fear of Failure/Risk Aversion – Large organizations are built around repeatable and scalable processes that are designed to be “fail safe.” Here new initiatives need to match existing budgeting, legal, HR and acquisition, processes and procedures. However, disruptive projects can only succeed in organizations that have a “safe-to-fail” culture. This is where learning and discovery happens via incremental and iterative experimentation with a portfolio of new ideas and failure is considered part of the process. “Fail safe” versus “safe-to-fail” organizations need to be separate and require different culture, different people, different development processes and risk tolerance.

Activist Investors Kill Transformation in Commercial Companies

A limit on transformation speed unique to commercial organizations is the fear of “Activist Investors.” “Activist investors” push public companies to optimize short-term profit, by avoiding or limiting major investments in new opportunities and technology. When these investors gain control of a company, innovation investments are reduced, staff is cut, factories and R&D centers closed, and profitable parts of the company and other valuable assets sold.

Unique Barriers for Government Organizations

Unique Barriers for Government Organizations

Government organizations face additional constraints that make them even slower to respond to change than large companies.

To start, leaders of the largest government organizations are often political appointees. Many have decades of relevant experience, but others are acting way above their experience level. This kind of mismatch tends to happen more frequently in government than in private industry.

Leaders’ tenures are too short – All but a few political appointees last only as long as their president in the White House, while leaders of programs and commands in the military services often serve 2- or 3-year tours. This is way too short to deeply understand and effectively execute organizational change. Because most government organizations lack a culture of formal innovation doctrine or playbook – a body of knowledge that establishes a common frame of reference and common professional language – institutional learning tends to be ephemeral rather than enduring. Little of the knowledge, practices, shared beliefs, theory, tactics, tools, procedures, language, and resources that the organization built under the last leader gets forwarded. Instead each new leader relearns and imposes their own plans and policies.

Getting Along Gets Rewarded – Career promotion in all services is primarily driven by “getting along” with the status quo. This leads to things like not cancelling a failing program, not looking for new suppliers who might be cheaper/ better/ more responsive, pursuing existing force design and operating concepts even when all available evidence suggests they’re no longer viable, selecting existing primes/contractors, or not pointing out that a major platform or weapon is no longer effective. The incentives are to not take risks. Doing so is likely the end of a career. Few get promoted for those behaviors. This discourages non-consensus thinking. Yet disruption requires risk.

Revolving doors – Senior leaders leave government service and go to work for the very companies whose programs they managed, and who they had purchased systems from (often Prime contractors). The result is that few who contemplate leaving the service and want a well-paying job with a contractor will hold them to account or suggest an alternate vendor while in the service.

Prime Contractors – are one of our nation’s greatest assets while being our greatest obstacles to disruptive change. In the 20th century platforms/weapons were mostly hardware with software components. In the 21st century, platforms/weapons are increasingly software with hardware added. Most primes still use Waterfall development with distinct planning, design, development, and testing phases rather than Agile (iterative and incremental development with daily software releases). The result is that primes have a demonstrated inability to deliver complex systems on time. (Moving primes to software upgradable systems/or cloud-based breaks their financial model.)

As well, prime contractors typically have a “lock” on existing government contracts. That’s because it’s less risky for acquisition officials to choose them for follow-on work– and primes have decades of experience in working through the byzantine and complex government purchasing process; and they have tons of people and money to influence all parts of the government acquisition system—from the requirements writers to program managers, to congressional staffers to the members of the Armed Services and Appropriations committees. New entrants have little chance to compete.

Congress – Lawmakers have incentives to support the status quo but few inducements to change it. Congress has a major say in what systems and platforms suppliers get used, with a bias to the status quo. To keep their own jobs, lawmakers shape military appropriations bills to support their constituents’ jobs and to attract donations from the contractors who hire them. (They and their staffers are also keeping the revolving door in mind for their next job.) Many congressional decisions that appear in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and in appropriations are to support companies that provide the most jobs in their districts and the most funds for their reelection. These come from the Prime contractors.

What to Do About It?

It starts at the top. Confronted with disruptive threats, senior leaders must actively work to understand:

Increase Visibility of Disruptive Tech and Concepts/Add Outside Opinions

Actively and Urgently Gather Evidence

Run real-world experiments – simulations, war games, – using disruptive tech and operating concepts (in offense and defense.)See and actively seek out the impact of disruption in adjacent areas e.g. AI’s impact on protein modeling, drones in the battlefield and Black Sea in Ukraine, et al.Ask the pointy end of the organization (e.g the sales force, fleet admirals) if they are willing to take more risk on new capabilities.These activities need happen in months not years. Possible recommendations from these groups include do nothing, run small experiments, transform a single function or department, or a company or organization-wide transformation.

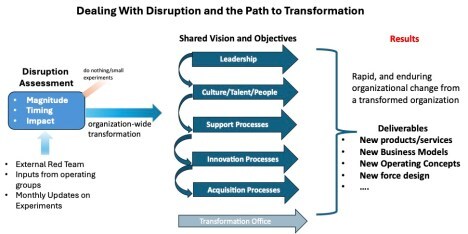

What Does Organization-wide Transformation look like?

What outcome do we desire?When do we need it?What budget, people, capital equipment are needed?What would need to be divested?How to communicate this to all stakeholders and get them aligned?In the face of disruption/ crisis/ wartime advanced R&D groups now need a seat at the table with budgets sufficient for deployment at scale.Consider organizing as an ambidextrous organization (e.g. SpaceX Falcon 9 operational execution versus Starship disruptive experimentation) (see this HBR article.)In addition to mangers of process, create rapid innovation teams (technologists, visionaries, senior champions)Finally, encourage more imagination. How can we use partners and other outside resources for technology and capital?Examples of leaders who transformed their organization in the face of disruption include Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and Steve Jobs from Apple, in defense, Bill Perry, Harold Brown and Ash Carter. Each dealt with disruption with acceptance, acknowledgment, imagination and action.

June 27, 2024

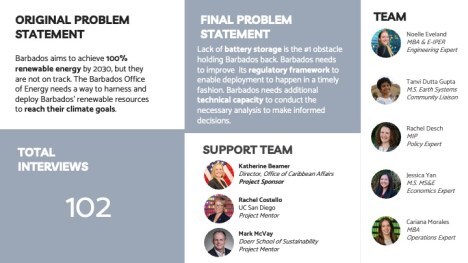

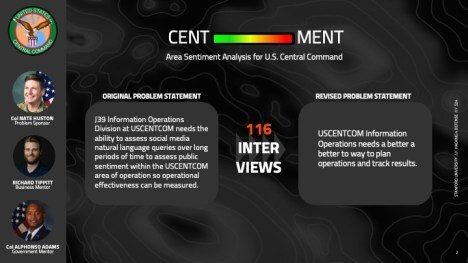

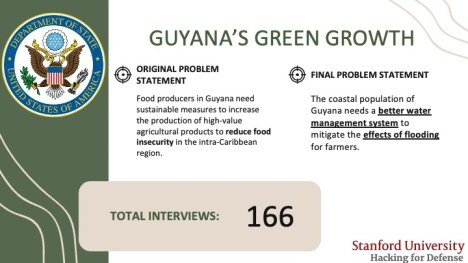

Lean LaunchPad @Stanford 2024 – 8 Teams In, 8 Companies Out

This post previously appeared in Poets and Quants.

This post previously appeared in Poets and Quants.

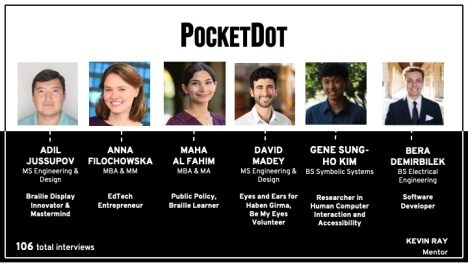

We just finished the 14th annual Lean LaunchPad class at Stanford. The class had gotten so popular that in 2021 we started teaching it in both the winter and spring sessions.

During the quarter the eight teams spoke to 919 potential customers, beneficiaries and regulators. Most students spent 15-20 hours a week on the class, about double that of a normal class.

In the 14 years we’ve been teaching the class, we had something that has never happened before – all eight teams in this cohort have decided to start a company.

This Class Launched a Revolution in Teaching Entreprenurship

Several government-funded programs have adopted this class at scale. The first was in 2011 when we turned this syllabus into the curriculum for the National Science Foundation I-Corps. Errol Arkilic, the then head of commercialization at the National Science, adopted the class saying, “You’ve developed the scientific method for startups, using the Business Model Canvas as the laboratory notebook.”

Below are the Lessons Learned presentations from the spring 2024 Lean LaunchPad.

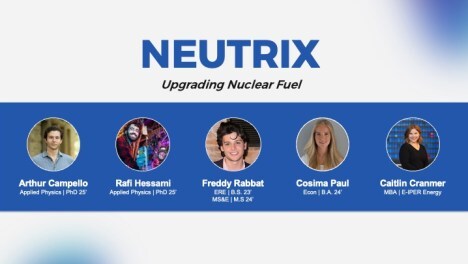

Team Neutrix – Making Existing Nuclear Reactors More Profitable By Upgrading Their FuelIf you can’t see the Neutrix video, click here

If you can’t see the Neutrix Presentation, click here

If you can’t see the Neutrix Presentation, click here

I-Corps at the National Institute of Health

In 2013 I partnered with UCSF and the National Institute of Health to offer the Lean LaunchPad class for Life Science and Healthcare (therapeutics, diagnostics, devices and digital health.) In 2014, in conjunction with the National Institute of Health, I took the UCSF curriculum and developed and launched the I-Corps @ NIH program.

If you can’t see the Virgil video, click here

If you can’t see the Virgil Presentation, click here.

If you can’t see the Virgil Presentation, click here.

I-Corps at Scale

I-Corps is now offered in 100 universities and has trained over 9,500 scientists and engineers; 7,800 in 2,546 teams in I-Corps at NSF (National Science Foundation), 950 participants at I-Corps at NIH in 317 teams, and 580 participants at Energy I-Corps (at the DOE) in 188 teams.

If you can’t see the Claim Pilot Presentation, click here

If you can’t see the Claim Pilot Presentation, click here

If you can’t see the Claim CoPilot video of their demo click here

$4 billion in Venture Capital For I-Corps Teams

1,380 of the NSF I-Corps teams launched startups raising $3.166 billion. Over 300 I-Corps at NIH teams have collectively raised $634 million. Energy I-Corps teams raised $151 million in additional funding.

If you can’t see the Emy.ai video, click here

If you can’t see the Emy.ai video, click here

If you can’t see the Emy.ai Presentation, click here

If you can’t see the Emy.ai Presentation, click here

Mission Driven Entreprenurship