Steve Blank's Blog, page 5

February 14, 2023

Startups that Have Employees In Offices Grow 3½ Times Faster

This article previously appeared in EIX – Entreprenuers and Innovators Exchange.

This article previously appeared in EIX – Entreprenuers and Innovators Exchange.

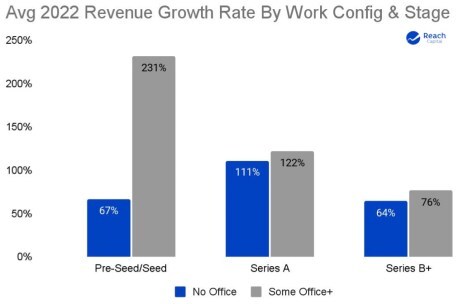

Data shows that pre-seed and seed startups with employees showing up in a physical office have 3½ times higher revenue growth than those that are solely remote.

Let the discussion begin.

During the pandemic, companies engaged in one of the largest unintended experiments in how to organize office work – remotely, in offices, or a hybrid of the two.

Post-pandemic, startups are still struggling to manage the best way to manage return-to-office issues – i.e. employee’s expectations of continuing to work remotely versus the best path to build and grow a profitable company.

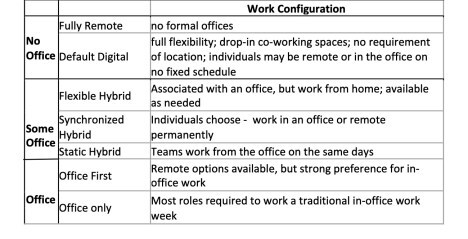

Before we can ask which is the best configuration, the first question is what, exactly do we mean by “remote work” versus “office work”? Today work configurations span the spectrum from no office (fully remote, default digital) to some office (flexible hybrid, synchronized hybrid, office first,) to office only.

James Kim at Reach Capital, an early-stage tech ed investor, surveyed their portfolio of 37 companies using the following taxonomy of how virtual and physical work could be configured.

Using this model James found that pre-seed and seed-stage startups that had employees returning to some type of office had 3½ times the revenue growth of startups that were fully remote. Those are staggeringly large differences, and while other factors may play some role (see “What Does This Mean, below), the impact of the all-hands-on-deck approach can’t be ignored.

Using this model James found that pre-seed and seed-stage startups that had employees returning to some type of office had 3½ times the revenue growth of startups that were fully remote. Those are staggeringly large differences, and while other factors may play some role (see “What Does This Mean, below), the impact of the all-hands-on-deck approach can’t be ignored.

What might account for these differences? Not surprisingly, almost 90% of the responses from pre-seed/seed startups said team culture was influenced by work configuration. However, unexpectedly, self-reported team culture, eNPS (employee Net Promoter Score) and regrettable attrition – departures that hurt the company — are similar across work configurations.

So while the employees said regardless of the office configuration the team culture didn’t appear to change, the performance of very early stage startups (as measured by revenue growth) told a different story.

So while the employees said regardless of the office configuration the team culture didn’t appear to change, the performance of very early stage startups (as measured by revenue growth) told a different story.

What Does This Mean?

The data is suggestive but not conclusive. See a full summary of the survey results here.

Let’s start with the data set. The survey sample size was 37 companies from the Reach Capital portfolio. That’s large enough to see patterns, but not large enough to generalize across all startups. Next, Reach Capital’s portfolio of companies are in education and the future of work. The revenue results by workplace configuration may be different in other markets. Reach Capital’s investments are made in many regions including Brazil, so the geography is not limited to Silicon Valley.

Finally office configuration is only one factor that might influence a startup’s growth rate. Still the results are suggestive enough that other VC’s might want to run the same surveys across their portfolio of companies and see if the results match.

(BTW, Nick Bloom at Stanford and others have done extensive research with thousands of people on remote and hybrid work here, and here. Their research is mostly focused on employees working on independent day-to-day tasks such as travel agents. However, we’re interested in the very specific subset of creative knowledge workers in the early stage of startups. Specifically at the stage when startups are searching for product/market fit and a business model not when they are executing day-to-day tasks.

If the results appear elsewhere, then one can speculate why. Working from home may offer more distractions by chores, family, network issues. Do those little things add up to meaningful productivity differences?

Is it that in early-stage startups the random conversations between employees at unscheduled and unplanned times lead to better insights and ideas? And if so, is the productive brainstorming occurring inside of departments –e.g. engineer to engineer — or is it the cross-fertilization between departments – e.g. engineering to marketing?

Research since the 20th century has proven that informal face-to-face interaction is important for the coordination of group activities, maintaining company culture, and team building. This informal information gives employees access to new, non-redundant information through connections to different parts of an organization’s formal org chart and through connections to different parts of an organization’s informal communication network. In addition, research has found that creativity is greatly enhanced in a “small world network – a network structure that is both highly locally clustered and often a hotbed of unscheduled fluid interactions that support innovation. In other words, inside an early-stage startup.

For decades Silicon Valley company founders and investors have known this small world network effect as tacit knowledge. It has been a hallmark of the physical design of Silicon Valley office space – from Xerox PARC to Pixar’s headquarters, to Google and Apple.

So perhaps the converse is true. Does remote work with ad hoc or fixed meetings via Zoom actually stunt the growth of creativity and new insights, just at the time a startup most needs them? Are there new tools such as Discord and others that can duplicate the water cooler effect of physical proximity?

Either way, it’s the beginning of an interesting discussion.

What has been your experience?

Lessons Learned

Data from one VC shows pre-seed and seed-stage startups with employees that show up to the office have 3½ times the revenue growth of those that work remotelyIs the data valid? Is it the same in all markets/industries?If it’s valid, why?Is there a difference in remote vs. in-office productivity for creative tasks versus execution tasks?

January 17, 2023

Is a Venture Studio Right for You?

This post previously appeared in the Harvard Business Review.

This post previously appeared in the Harvard Business Review.

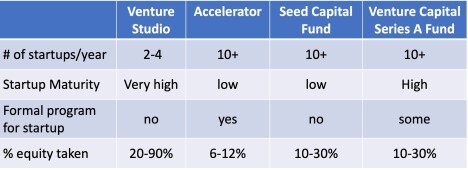

Three types of organizations – Incubators, Accelerators and Venture Studios – have emerged to reduce the risk of early-stage startup failure by helping teams find product/market fit and raise initial capital. Venture Studios are an “idea factory” with their own employees searching for product/market fit and a repeatable and scalable business model. They do the most to de-risk the early stages of a startup.

Outside a small university in the Midwest, I was having coffee with Carlos, a rising star inside a mid-sized manufacturing company. He had a track record of taking small teams and growing them into successful product lines. However, after a decade working for others, Carlos was interested in building and growing a company of his own. I asked how much he knew about how to get started. He said that from what he read, the path to building and funding a company seemed to be: 1) come up with an idea, 2) form a team, 3) start testing minimal viable products, 4) raise seed funding, 5) then obtain venture capital.

As he described his work in additive manufacturing and 3D printing, Carlos said he knew that there were seed investors in his town, but venture capital was still largely on the coasts, and it was hard to get their attention. He also wasn’t sure his idea was great. But he still had the itch to grow something small into a substantive company.

As we grabbed dessert, Carlos asked, “Other than raising money, are there other ways to start a company?”

I pointed out that there were.

Reducing Startup Risk

In the last two decades, three types of organizations — incubators, accelerators and venture studios — have emerged to reduce the risk of early-stage startup failure by helping teams find product/market fit and raise initial capital. Most are founded and run by experienced entrepreneurs that have previously built companies and who understand the difference between theory and practice.

I pointed out to Carlos that accelerators like Y-Combinator, Techstars, and 500 Startups offer a cohort of startups a six to 12-week bootcamp. But these look for founders who have a technical or business model insight and a team. Accelerators provide these teams with technical and business expertise and connect them to a network of other founders and advisors. The culmination of this bootcamp is a “demo day” where all startups in the cohort have a few minutes to pitch their companies to venture capitalists and angel investors. (In some cases the accelerator provides initial funding themselves.) In exchange for attending an accelerator, startups give up 5% to 10% of their company’s equity.

There are thousands of accelerators across the globe. The business model for most of these accelerators is to select startups that can generate venture-class returns – i.e. grow into companies that can potentially be worth billions of dollars. For most accelerators, admission is by application and interview. Some, like Y-Combinator, Techstars, and 500 Startups are open to all types of startups in any market, while others like SOSV, IndieBio, HAX, Orbit, dLab are more specialized.

Incubators are similar to accelerators in that they provide space and shared resources to startups, but usually no or very small amounts of capital. Their financial models are based on membership fees that grant access to a shared coworking space, resources, and access to other founders and operational expertise.

Carlos stirred his coffee. “Accelerators don’t sound like a fit for where I am at in my career,” he offered. “I don’t have a killer idea, or a technical team, but I do know how to build, grow, and manage teams.”

The Alternative: Venture Studios

I pointed out there were organizations that might be a better fit for his skills and passion to go out on his own — venture studios. Unlike an accelerator, a venture studio does not fund existing startups.

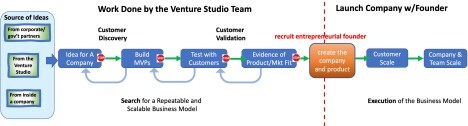

Venture studios create startups by incubating their own ideas or ideas from their partners. The studio’s internal team builds the minimal viable product, then validates an idea by finding product/market fit and early customers. If the idea passes a series of “Go/No Go” decisions based on milestones for customer discovery and validation, the studio recruits entrepreneurial founders to run and scale those startups. Examples of companies that have emerged from venture studios, include Overture, Twilio, bitly, aircalla, and the most famous alum, Moderna,

I suggested Carlos think of a venture studio as an “idea factory” with their own full-time employees engaged in searching for product/market fit and a repeatable and scalable business model.

How Venture Studios Work

Unlike an accelerator or incubator, a venture studio doesn’t fund existing startups. It’s a company that creates multiple startups in-house, then finds entrepreneurs who take them over to grow them.

Most venture studios create and launch several startups each year. These have a greater success rate than those that come out of accelerators or traditional venture-funded companies. That’s because unlike accelerators, which operate on a six- to 12-week cadence, studios don’t have a set timeframe. Instead, they search and pivot until product-market fit is found. Unlike an accelerator or a VC firm, a venture studio kills most of their ideas that can’t find traction and won’t launch a startup if they can’t find evidence that it can be a scalable and profitable company.

Comparing Startup Funding Options

Venture studios are a good fit for entrepreneurs who don’t have an idea or team but would like to run and grow a startup. The venture studio’s employees have already identified a product, market fit and early customers — meaning someone else has eliminated many of the early risks of a new venture. In return for the lower risk, a venture studio typically takes a larger percentage of equity.

There are four main types of venture studios:

Tech transfer studios, such as America’s Frontier Fund, work with companies and/or government labs to source ideas and intellectual property. They then transfer the IP and build the startup inside the venture studio.Corporate studios, such as Applied Materials, source ideas and intellectual property inside their own company. They then build the startup inside a separate corporate venture studio inside the company.A niche studio is a standalone venture studio that generates its own ideas and IP in a specific industry and domain – for example Flagship Pioneering , which is focused on health care and incubated LS18 — the company that became Moderna.An industry agnostic studio, such as Rocket Internet, is a standalone venture studio that generates its own ideas and IP and is industry and market agnostic.Today there are around 720+ venture studios across the world – half are in Europe. In both North America and Europe, many venture studios in non-major cities are funded by government agencies to stimulate local growth, at times with matching donations from companies. These studios have different metrics than startup studios whose limited partners are private family offices or venture capitalists.

Why Would an Entrepreneur Join a Venture Studio?

While we were on our second cup of coffee, I told Carlos about the downside to joining a company created by a venture studio — how much equity/ownership they take.

In contrast with an accelerator that takes 5%-10% of a startup’s equity, venture studios take anywhere from 30%-80% of a startup’s equity. This is because companies exiting a venture studios have been handed a startup that has de-risked of much of the early-stage startup process. (There’s a direct correlation between the amount of equity a venture studio takes and their belief in how much they want their founding CEO to be an entrepreneur versus executor.)

Why would an entrepreneur join a venture studio and give up the majority of their company rather than go to accelerator? Most accelerators tend to look for a “founder type” — a stereotypical techie, fresh out of college, who already has an idea and cofounders.

Most people don’t fit that pattern. Yet many are more than capable of taking an idea that’s been stress-tested and validated and building it.

What To Look for in a Venture Studio?

As we got up to leave Carlos asked, “How would I know whether the venture studio a good one?”

It was a great question. While there are no hard-and-fast rules, I advise entrepreneurs to ask these four questions:

Is the studio run by a former founder and does it have former founders as full-time employees? The most successful venture studios are founded by entrepreneurs that have previously built companies with $10+M in revenue and had 100+ employees.What percentage of equity are they asking for? The answer will be directly proportional to what they think your value is. Firms asking for greater than 60% are actually hiring an employee rather than a founder.Do you want a studio with specific expertise? Studios that focus on specific niches and industries can build a deep bench of domain experts – e.g. founder, advisors, and mentors – who are experts in this one fieldDo they have enough funding? Watch out for Zombie studios. If you’ve given away a majority of your company to a studio, it would be helpful to have them around for support after you’ve started. If they don’t have enough funding to keep the lights on for several years, you’re on your own. Make sure your studio has raised more than $10m in funding.A few weeks later I got a note from Carlos letting me know that he found that there was a venture studio in his city, another run by the state, and a third in his region focused on manufacturing. He had applied to all of them.

January 10, 2023

Be Where Your Business Is

This post previously appeared on the readwrite blog.

This post previously appeared on the readwrite blog.

A CEO running a B-to-B startup in needs to live in the city where their business is – or else they’ll never scale.

I was having breakfast with Erin, an ex-student, just off a red-eye flight from New York. She’s built a 65-person startup selling enterprise software to the financial services industry. Erin had previously worked in New York for one of those companies and had a stellar reputation in the industry. As one would expect, with banks and hedge funds as customers, the majority were based in the New York metropolitan area.

Where Are Your Biggest Business Deals?

Where Are Your Biggest Business Deals?

Looking a bit bleary-eyed, Erin explained, “Customers love our product, and I think we’ve found product/market fit. I personally sold the first big deals and hired the VP of sales who’s building the sales team in our New York office. They’re growing the number of accounts and the deal size, but it feels like we’re incrementally growing a small business, not heading for exponential growth. I know the opportunity is much bigger, but I can’t put my finger on what’s wrong.”

Erin continued, “My investors are starting to get impatient. They’re comparing us to another startup in our space that’s growing much faster. My VP of Sales and I are running as fast as we can, but I’ve been around long enough to know I might be the ex-CEO if we can’t scale.”

While Erin’s main sales office is in New York, next to her major prospects and customers, Erin’s company was headquartered in Silicon Valley, down the street from where we were having breakfast. During the Covid pandemic, most of her engineering team worked remotely. Her inside sales team (Sales Development and Business Development reps) used email, phone, social media and Zoom for prospecting and generating leads. At the same time, her account executives were able to use Zoom for sales calls and close and grow business virtually.

There’s a Pattern Here

Over breakfast, I listened to Erin describe what at first seemed like a series of disconnected events.

First, a new competitor started up. Initially, she wasn’t concerned as the competitor’s product had only a subset of the features that Erin’s company did. However, the competitor’s headquarters was based in New York, and their VP of Sales and CEO were now meeting face-to-face with customers, most of whom had returned to their offices. While Erin’s New York-based account execs were selling to the middle tier management of organizations, the CEO of her competitor had developed relationships with the exec staff of potential customers. She lamented, “We’ve lost a couple of deals because we were selling at the wrong level.”

Second, Erin’s VP of sales had just bought a condo in Miami to be next to her aging parents, so she was commuting to NY four days a week and managing the sales force from Miami when she wasn’t in New York. Erin sighed, “She’s as exhausted as I am flying up and down the East Coast.”

Third, Erin’s account execs were running into the typical organizational speedbumps and roadblocks that closing big deals often encounter. However, solving them via email, Zoom and once-a-month fly-in meetings wasn’t the same as the NY account execs being able to say, “Hey, our VP of Sales and CEO are just down the street. Can we all grab a quick coffee and talk this over?” Issues that could have been solved casually and quickly ballooned into ones that took more work and sometimes a plane trip for her VP of Sales or Erin to solve.

By the time we had finished breakfast it was clear to me that Erin was the one putting obstacles in front of her path to scale. Here’s what I observed and suggested.

Keep Your Eye on The Prize

While Erin had sold the first deals herself, she needed to consider whether each deal happened because as CEO, she could call on the company’s engineers to pivot the product. Were the account execs in New York trying to execute a sales model that wasn’t yet repeatable and scalable without the founder’s intervention? Had a repeatable and scalable sales process truly been validated? Or did each sale require a heroic effort?

Next, setting up their New York office without Erin or her VP of Sales physically living in New York might have worked during Covid but was now holding her company back. At this phase of her company the goal of the office shouldn’t be to add new accounts incrementally – but should be how to scale – repeatably. Hiring account execs in an office in New York let Erin believe that she had a tested, validated, and repeatable sales playbook that could rapidly scale the business. The reality was that without her and the VP of Sales living and breathing the business in New York, they were trying to scale a startup remotely.

Her early customers told Erin that her company had built a series of truly disruptive financial service products. But now, the company was in a different phase – it needed to build and grow the business exponentially. And in this phase, her focus as a CEO needed to change – from searching for product/market fit to driving exponential growth.

Exponential Growth Requires Relentless Execution

Exponential Growth Requires Relentless Execution

Because most of her company’s customers were concentrated in a single city, Erin and her VP of Sales needed to be there – not visiting in a hotel room. I suggested that:

I Hate New York

As we dug into these issues, I was pretty surprised to hear her say, “I spent a big part of my career in New York. I thought coming out to Stanford and the West Coast meant I could leave the bureaucracy of large companies and that culture behind. Covid let me do that for a few years. I guess now I’m just avoiding jumping back into an environment I thought I had left.”

We lingered over coffee as I suggested it was time for her to take stock of what’s next. She had something rare – a services company that provided real value with products that early customers loved. Her staff didn’t think they were joining a small business, neither did her investors. If she wasn’t prepared to build something to its potential, what was her next move?

Lessons Learned

For a startup, the next step after finding product/market fit is finding a repeatable and scalable sales processThis requires a transition to the relentless execution of creating demand and exponentially growing salesIf your customers are concentrated in a city or region, you need to be where your customers areThe CEO needs to lead this growth focusAnd then hand it off to a team equally capable and committed

January 5, 2023

Technology, Innovation, and Great Power Competition – 2022 Wrap Up

We just wrapped up the second year of our Technology, Innovation, and Great Power Competition class – now part of our Stanford Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation.

Joe Felter, Raj Shah and I designed the class to 1) give our students an appreciation of the challenges and opportunities for the United States in its enduring strategic competition with the People’s Republic of China, Russia and other rivals, and 2) offer insights on how commercial technology (AI, machine learning, autonomy, cyber, quantum, semiconductors, access to space, biotech, hypersonics, and others) are radically changing how we will compete across all the elements of national power e.g. diplomatic, informational, military, economic, financial, intelligence and law enforcement (our influence and footprint on the world stage).

Why This Class?

Why This Class?

The return of strategic competition between great powers became a centerpiece of the 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy. The 2021 Interim National Security Guidance and the administration’s recently released 2022 National Security Strategy make clear that China has rapidly become more assertive and is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system. And as we’ve seen in the Ukraine, Russia remains determined to wage a brutal war to play a disruptive role on the world stage.

Prevailing in this competition will require more than merely acquiring the fruits of this technological revolution; it will require a paradigm shift in the thinking of how this technology can be rapidly integrated into new capabilities and platforms to drive new operational and organizational concepts and strategies that change and optimize the way we compete.

Class Organization

The readings, lectures, and guest speakers explored how emerging commercial technologies pose challenges and create opportunities for the United States in strategic competition with great power rivals with an emphasis on the People’s Republic of China. We focused on the challenges created when U.S. government agencies, our federal research labs, and government contractors no longer have exclusive access to these advanced technologies.

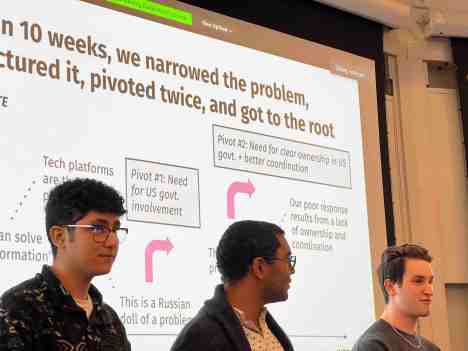

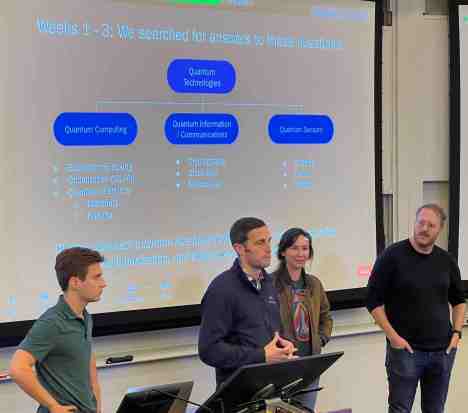

This course included all that you would expect from a Stanford graduate-level class in the Masters in International Policy – comprehensive readings, guest lectures from current and former senior officials/experts, and written papers. What makes the class unique however, is that this is an experiential policy class. Students formed small teams and embarked on a quarter-long project that got them out of the classroom to 1) identify a priority national security challenge, and then to 2) validate the problem and propose a detailed solution tested against actual stakeholders in the technology and national security ecosystem.

This course included all that you would expect from a Stanford graduate-level class in the Masters in International Policy – comprehensive readings, guest lectures from current and former senior officials/experts, and written papers. What makes the class unique however, is that this is an experiential policy class. Students formed small teams and embarked on a quarter-long project that got them out of the classroom to 1) identify a priority national security challenge, and then to 2) validate the problem and propose a detailed solution tested against actual stakeholders in the technology and national security ecosystem.

The class was split into three parts. Part 1, weeks 1 through 4 covered international relations theories, strategies and policies around Great Power Competition specifically focused on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Communist Peoples Party (CCP). Part 2, weeks 5 through 8, dove into the commercial technologies: semiconductors, space, cyber, AI and Machine Learning, High Performance Computing, and Biotech. In between parts 1 and 2 of the class, the students had a midterm individual project. It required them to write a 2,000-word policy memo describing how a U.S. competitor is using a specific technology to counter U.S. interests and a proposal for how the U.S. should respond. (These policy memos were reviewed by Tarun Chhabra, the Senior Director for Technology and National Security at the National Security Council.)

Each week the students had to read 5-10 articles (see class readings here.) And each week we had guest speakers on great power competition, and technology and its impact on national power and lectures/class discussion.

Guest Speakers

Guest Speakers

In addition to the teaching team, the course drew on the experience and expertise of guest lecturers from industry and from across U.S. Government agencies to provide context and perspective on commercial technologies and national security.

Our class opened with three guest speakers; former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis and the CIA’s CTO and COO Nand Mulchandani and Andy Makridis. The last class closed with a talk by Google ex-Chairman Eric Schmidt.

In the weeks in-between we had teaching team lectures followed by speakers that led discussions on the critical commercial technologies. For semiconductors, the White House Coordinator for the CHIPS Act – Ronnie Chatterji, and the CTO of Applied Materials – Om Nalamasu. For commercial tech integration and space, former Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) Director Mike Brown and B. General Bucky Butow – Director of the Space Portfolio. For Artificial Intelligence, Lt. Gen. (Ret) Jack Shanahan, former director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center. And for synthetic biology Stanford Professor Drew Endy – President, BioBricks Foundation.

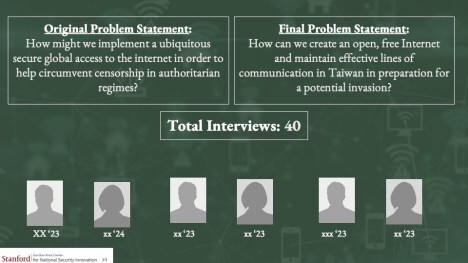

Team-based Experiential Project

The third part of the class was unique – a quarter-long, team-based project. Students formed teams and developed hypotheses of how commercial technologies can be used in new and creative ways to help the U.S. wield its instruments of national power. And consistent with all our Gordian Knot Center classes, they got out of the classroom and interviewed 20+ beneficiaries, policy makers, and other key stakeholders testing their hypotheses and proposed solutions. At the end of the quarter, each of the teams gave a final “Lessons Learned” presentation and followed up with a 3,000 to 5,000-word team-written paper.

By the end of the class all the teams realized that the problem they had selected had morphed into something bigger, deeper, and much more interesting.

Team 1: Climate ChangeOriginal Problem Statement: What combinations of technologies and international financial relationships should the US prioritize to mitigate climate change?

Final Problem Statement: How should the US manage China’s dominance in solar panels?

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

We knew that these students could write a great research paper. As we pointed out to them, while you can be the smartest person in the building, it’s unlikely that 1) all the facts are in the building, 2) you’re smarter than the collective intelligence sitting outside the building.

Jonah Cader: “Technology, Innovation and Great Power Competition (TIGPC) is that rare combination of the theoretical, tactical, and practical. Over 10 weeks, Blank, Felter, and Shah outline the complexities of modern geopolitical tensions and bring students up the learning curves of critical areas of technological competition, from semiconductors to artificial intelligence. Each week of the seminar is a crash course in a new domain, brought to life by rich discussion and an incredible slate of practitioners who live and breathe the content of TIGPC daily. Beyond the classroom, the course plunges students into getting “out of the building” to iterate quickly while translating learnings to the real world. Along the way the course acts as a strong call to public service.”

Team 2: NetworksOriginal Problem Statement: How might we implement a ubiquitous secure global access to the internet in order to help circumvent censorship in authoritarian regimes?

Final Problem Statement: How can we create an open, free Internet and maintain effective lines of communication in Taiwan in preparation for a potential invasion?

If you can’t see the presentation click here

By week 2 of the class students formed teams around a specific technology challenge facing a US government agency and worked throughout the course to develop their own proposals to help the U.S. compete more effectively through new operational concepts, organizations, and/or strategies.

Jason Kim: “This course doesn’t just discuss U.S. national security issues. It teaches students how to apply an influential and proven methodology to rapidly develop solutions to our most challenging problems.”

Team 3: AcquisitionOriginal Problem Statement: How can the U.S. Department of Defense match or beat the speed of great power competitors in acquiring and integrating critical technologies?

Final Problem Statement: How can the U.S. Department of Defense deploy alternative funding mechanisms in parallel to traditional procurement vehicles to enable and incentivize the delivery of critical next-generation technology in under 5 years?

If you can’t see the presentation click here

We wanted to give our students hands-on experience on how to deeply understand a problem at the intersection of our country’s diplomacy, information, its military capabilities, economic strength, finance, intelligence, and law enforcement and dual-use technology. First by having them develop hypotheses about the problem; next by getting out of the classroom and talking to relevant stakeholders across government, industry, and academia to validate their assumptions; and finally by taking what they learned to propose and prototype solutions to these problems.

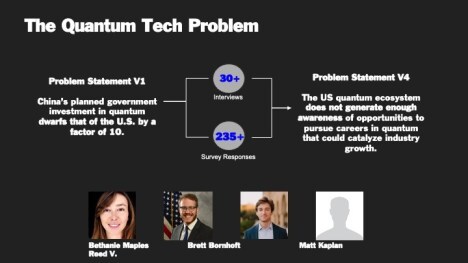

Matt Kaplan: “The TIGPC class was a highlight of my academic experience at Stanford. Over the ten week quarter, I learned a tremendous amount about the importance of technology in global politics from the three professors and from the experts in government, business, and academia who came to speak. The class epitomizes some of the best parts of my time here: the opportunity to learn from incredible, caring faculty and to work with inspiring classmates. Joe, Steve, Raj instilled in my classmates and me a fresh sense of excitement to work in public service.” Team 4: WargamesOriginal Problem Statement: The U.S. needs a way, given a representative simulation, to rapidly explore a strategy for possible novel uses of existing platforms and weapons.

Final Problem Statement: Strategic wargames stand to benefit from a stronger integration of AI+ML but are struggling to find adoption and usage. How can this be addressed?

If you can’t see the presentation click here

We want our students to build the reflexes and skills to deeply understand a problem by gathering first-hand information and validating that the problem they are solving is the real problem, not a symptom of something else. Then, students began rapidly building minimal viable solutions (policy, software, hardware …) as a way to test and validate their understanding of both the problem and what it would take to solve it.

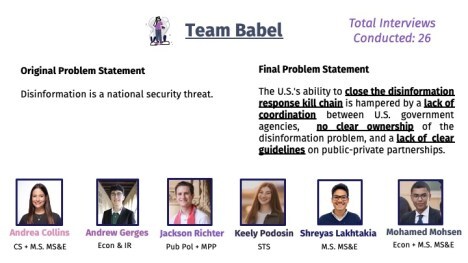

Etienne Reche-Ley: “Technology, Innovation and Great Power Competition gave me an opportunity to dive into a real world national security threat to the United States and understand the implications of it within the great power competition. Unlike any other class I have taken at Stanford, this class allowed me to take action on our problem about networks, censorship and the lack of free flow of information in authoritarian regimes, and gave me the chance to meet and learn from a multitude of experts on the topic. I finished this class with a deep understanding of our problem, a proposed actionable solution and a newfound interest in the intersection of technology and innovation as it applies to national defense. I am very grateful to have been part of this course, and it has inspired me to go a step further and pursue a career related to national security.”Team 6: DisinformationOriginal Problem Statement: Disinformation is a national security threat.

Final Problem Statement: The U.S.’s ability to close the disinformation response kill chain is hampered by a lack of coordination between U.S. government agencies, no clear ownership of the disinformation problem, and a lack of clear guidelines on public-private partnerships.

If you can’t see the presentation click here

One other goal of the class was to continue to validate and refine our pedagogy of combining a traditional lecture class with an experiential project. We did this by tasking the students to 1) use what they learned from the lectures and 2) then test their assumptions outside the classroom, the external input they received would be a force multiplier. It would make the lecture material real, tangible and actionable. And we and they would end up with something quite valuable.

One other goal of the class was to continue to validate and refine our pedagogy of combining a traditional lecture class with an experiential project. We did this by tasking the students to 1) use what they learned from the lectures and 2) then test their assumptions outside the classroom, the external input they received would be a force multiplier. It would make the lecture material real, tangible and actionable. And we and they would end up with something quite valuable.

Original Problem Statement: China’s planned government investment in quantum dwarfs that of the U.S. by a factor of 10.

Final Problem Statement: The US quantum ecosystem does not generate enough awareness of opportunities to pursue careers in quantum that could catalyze industry growth.

If you can’t see the presentation click here

We knew we were asking a lot from our students. We were integrating a lecture class with a heavy reading list with the best practices of hypothesis testing from Lean Launchpad/Hacking for Defense/I-Corps. But I’ve yet to bet wrong in pushing students past what they think is reasonable. Most rise way above the occasion.

We knew we were asking a lot from our students. We were integrating a lecture class with a heavy reading list with the best practices of hypothesis testing from Lean Launchpad/Hacking for Defense/I-Corps. But I’ve yet to bet wrong in pushing students past what they think is reasonable. Most rise way above the occasion.

Original Problem Statement: Supply and production of lithium-ion batteries is centered in China. How can the U.S. become competitive?

Final Problem Statement: China controls the processing of critical materials used for lithium-ion batteries. To regain control the DOE needs to incentivize short and long-term strategies to increase processing of critical materials and decrease dependence on lithium-ion batteries.

If you can’t see the presentation click here

All of our students put in extraordinary amount of work. Our students came from a diverse set of background and interests – from undergraduate sophomores to 5th year PhD’s – in a mix including international policy, economics, computer science, business, law and engineering. Some will go on to senior roles in State, Defense, policy or other agencies. Others will join or found the companies building new disruptive technologies. They’ll be the ones to determine what the world-order will look like for the rest of the century and beyond. Will it be a rules-based order where states cooperate to pursue a shared vision for a free and open region and where the sovereignty of all countries large and small is protected under international law? Or will it be an autocratic and dystopian future coerced and imposed by a neo-totalitarian regime?

This class changed the trajectory of many of our students. A number expressed newfound interest in exploring career options in the field of national security. Several will be taking advantage of opportunities provided by the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation to further pursue their contribution to national security.

This course and our work at Stanford’s Gordian Knot Center would not be possible without the unrelenting support and guidance from Ambassador Mike McFaul and Professor Riitta Katila, GKC founding faculty and Principal Investigators, and the tenacity of David Hoyt, Gordian Knot Center Assistant Director.

Lessons Learned

We combined lecture and experiential learning so our students can act on problems not just admire themThe external input the students received was a force multiplierIt made the lecture material real, tangible and actionablePushing students past what they think is reasonable results in extraordinary output. Most rise way above the occasionThe class creates opportunities for our best and brightest to engage and address challenges at the nexus of technology, innovation and national securityThe final presentations and papers from the class are proof that will happen

November 30, 2022

Why The Pentagon Can’t Count: It’s Time to Reinvent the Audit

This article previously appeared in War on the Rocks.

This article previously appeared in War on the Rocks.

In the past, headlines about the Pentagon failing its financial audit again would never have caught my attention. But having been in the middle of this conversation when I served on one of the Defense Department’s advisory boards, I understand why the Pentagon can’t count. The experience taught me a valuable lesson about innovation and imagination in large organizations, and the difference visionary leadership – or the lack of it – can make.

With audit costs approaching a billion dollars a year the Pentagon had an opportunity to lead in modernizing auditing. Instead it opted for more of the same.

Auditing the Department of Defense

By law, the Department of Defense has to provide Congress and the public with an assessment of where it spends its money and to provide transparency of its operations. A financial audit counts what the Department of Defense has, where it has it, and if they know where its money is being spent.

Auditing the Department of Defense is a massive undertaking. For one thing, it is the country’s largest employer, with 2.9 million people (1.3 million on active duty, 800,000 in the reserve components, and 770,000 civilians.) The audit has to count the location and condition of every piece of military equipment, property, inventory, and supplies. And there are a lot of them. The department has 643,900 assets, from buildings, to pipelines, roads, and fences located on over 4,860 sites, as well as 19,700 aircraft and over 290 battle force ships. To complicate the audit, the department has 326 different and separate financial management systems, 4,700 data warehouses and over 10,000 different and disconnected data management systems.

(BTW, just like in the private sector, financial audits and audits of contracts are separate. While the DoD Office of Inspector General is responsible for these financial audits of trillions of dollars of assets and liabilities, the Defense Contract Audit Agency is responsible for auditing the hundreds of billions of dollars of acquisition contracts. They have the same issues.)

This is the fifth year the Department has undergone a financial statement audit – and failed it. The audit was not a trivial effort, it required 1,600 auditors – 1,450 from public accounting firms and 150 from the Office of Inspector General. In 2019, the audit cost $428 million in auditing costs ($186 million to the auditors along with $242 million to audit support) and another $472 million to fix the issues the audit discovered.

Let’s Invent the Future of Audit

The Defense of Department’s 40-plus advisory boards are staffed by outsiders who can provide independent perspectives and advice. I sat on one of these boards, and our charter was to leverage private sector lessons to improve audit quality.

With defense spending on auditing approaching a billion dollars a year, it was clear it would take a decade or more to catch up to the audit standards of private companies. But no single company or even entire industry was spending this much money on auditing. And remarkably, the Defense Department seemed intent on doing the same thing year after year, just with more people and with a few more tools and processes to get incrementally better. It dawned on me that if we tried to look over the horizon, the department could audit faster, cheaper, and more effectively by inventing the future tools and techniques rather than repeating the past.

Nothing in our charter asked the advisory board to invent the future. But I found myself asking, “What if we could?” What if we could provide the defense department with new technology, new approaches to auditing, analytics practices, audit research, and standards, all while creating audit and data management research and a new generation of finance applications and vendors?

The Pentagon Once Led Business Innovation

I reminded my fellow advisory board members that in 1959, at the dawn of the computer age, the Defense Department was the largest user of computers for business applications.

However, there was no common business programing language. So rather than wait for one, the Defense Department led the effort to create one – the COBOL programming language. And 20 years later, it did the same for the ADA programming language.

With that history in mind, I proposed we lead again. And that we start an initiative for the 5th generation of audit practices (the Audit 5.0 Initiative) with machine learning, predictive analytics, Intelligent sampling and predictions. This initiative would also include automating ETL, predictive analytics, fraud detection, and a new generation of audit standards.

I pointed out that this program wouldn’t need more funds since the Department of Defense could allocate 10% of the $428M we were spending on auditors and fund SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) programs in auditing/data management/finance to generate 5-10 new startups in this space each year. Simultaneously we could fund academic research, to incentivize research on Machine Learning as applied to Audit 5.0 challenges in finance, auditing and data management.

I pointed out that this program wouldn’t need more funds since the Department of Defense could allocate 10% of the $428M we were spending on auditors and fund SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) programs in auditing/data management/finance to generate 5-10 new startups in this space each year. Simultaneously we could fund academic research, to incentivize research on Machine Learning as applied to Audit 5.0 challenges in finance, auditing and data management.

In addition, we could create new audit standards by working with existing government audit standards bodies such as (The Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS), Yellow Book, the GAO’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, Green Book and the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB). We could collaborate with civilian audit standard bodies (ASB (Auditing Standards Board) and PCAOB (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board). Working together, the defense department could create the next generation of machine-driven and semiautomated standards. Furthermore, it could help the Independent Public Accounting firms (KPMG, EY, PwC, Deloitte, et al) create a new practice and make them partners in the Audit 5.0 initiative.

By investing 10 percent of the existing auditing budget over the next few years, these activities would create a defense audit center of excellence that would fund academic centers for advanced audit research, standup “future of audit” programs that would create new 5-10 startups each year, be the focal point for government an industry finance and audit standards, and create public-private partnerships rather than mandates.

Spinning up these activities up would dramatically reduce the department’s audit costs, standardize its financial management environment, and provide confidence in their budget, auditability, and transparency. And as a bonus, it would create a new generation of finance, audit and data management startups, funded by private capital.

The Road Not Taken

I was in awe of my fellow advisory board members. They had spent decades in senior roles in finance and accounting in both the public and private sectors. Yet, when I pitched this idea, they politely listened to what I had to say and then moved on to their agenda – providing the DoD with Incremental improvements.

At the time I was disappointed, but not surprised. An advisory board is only as good as what it’s being chartered and staffed to do. If they are being asked to provide a 10 percent incremental advice, they’ll do so. But if they’re asked for revolutionary i.e. 10x advice, they can change the world. But that requires a different charter, leadership, people, innovation, and imagination.

In the end, the Department of Defense, the largest purchaser of accounting services in the world, whiffed a chance to be the leader in creating the next generation of audit tools and services, not only for financial audits, but for the hundreds of billions of dollars of acquisition contracts the Defense Contract Audit Agency audits. By now the department could have audit tools driven by machine learning algorithms, ferreting out fraud by vendors or contractors and anticipating programs that are at risk.

Lessons Learned

If you only get what you ask for you haven’t hired people with imaginationAmerica’s defense leaders ought to ask and act for transformational, contrarian and disruptive adviceAnd ensure they have the will and organizations to act on itMove requests for advice for incremental improvements to the consulting firms that currently serve the Defense DepartmentDefense leaders need to consider whether spending a billion dollars a year for an audit is causing the department to become appreciably more efficient or better managedOr whether there might be a better way

November 14, 2022

The 6th Lean Innovation Educators Summit – Education and Innovation in the Age of Chaos and Disruption

Join Jerry Engel, Pete Newell, and Steve Weinstein for the sixth edition of the Lean Innovation Educators Summit December 14, 1-4 pm Eastern Time, 10 am-1 pm Pacific Time. Register here.

—

This virtual gathering will bring together entrepreneurship educators from around the world who are putting Lean Innovation to work in their classrooms, accelerators, venture studios, and student-driven ventures.

The summit topic is “Education and Innovation in the Age of Chaos and Disruption.”

Our students will be facing the challenges of a world that’s rapidly changing, chaotic and uncertain. A world undergoing climate change, supply chain disruptions, political instability and continual technology innovation and disruption. It’s incumbent on us as educators to provide the next generation of innovators with the tools and mindset to meet these challenges.

Among the questions we’ll address in this short summit:

How do we as entrepreneurship and innovation educators best prepare the next generation?What role should our institutions help us do this?What are the other systems and partnerships that we need to take advantage of?We will have concurrent breakout sessions so participants have the opportunity to choose their own path to explore. We’ll then going to pivot to hear from colleagues across three broad categories of innovation:

Curriculum – We’ll discuss how best to equip educators with the tools they need to cultivate and guide student teams around solving mission-driven problems.Ecosystems – We’ll explore partnerships that engage and inform positive student engagement and outcomes and how to support diversity of thought, background.Trends – The rate of technological disruption shows no sign of slowing down. Climate change was a hypothesis for our generation but will be the facts on the ground for our students. The struggle between great powers and a fluid global landscape will accelerate. All of these will shape what future curriculums our students need and educators must deliver.Alexander Osterwalder, the creator of the business model canvas and Strategyzer co-founder will join the discussion about the intersection of education, innovation and entrepreneurship

During the breakout sessions, you will have the opportunity to contribute to the conversation via Chat, Q&A, and an online community bulletin board. We will close out the Summit with Alex Osterwalder’s fireside chat moderated by Dr. Jerry Engel.

How to register

When you register, you will receive a link to an online collaboration space where you can submit questions, challenges and feedback. This feedback will inform the content of the presentations, post-event white papers, and the curriculum delivered to our educator community.

This session is free but limited to Innovation educators. Register here and learn more on our website: We look forward to gathering as a community of educators to shape the future of Lean Innovation Education.

November 11, 2022

The Three Pillars of World-class Corporate Innovation

My good friend Alexander Osterwalder, the inventor of the business model canvas (one of foundations of the Lean Methodology) has written a playbook (along with his associate partner Tendayi Viki,) From Innovation Theater to Growth Engine to explain how to build and implement repeatable innovation processes inside a company.

My good friend Alexander Osterwalder, the inventor of the business model canvas (one of foundations of the Lean Methodology) has written a playbook (along with his associate partner Tendayi Viki,) From Innovation Theater to Growth Engine to explain how to build and implement repeatable innovation processes inside a company.

Here’s their introduction to the key concepts inside the playbook.

Over 75% of executives report that innovation is a top three priority at their companies. However, only 20% of executives indicate that their companies are ready to innovate at scale. This is the challenge for contemporary organizations: How to develop a world-class ecosystem that can drive repeatable innovation at scale.

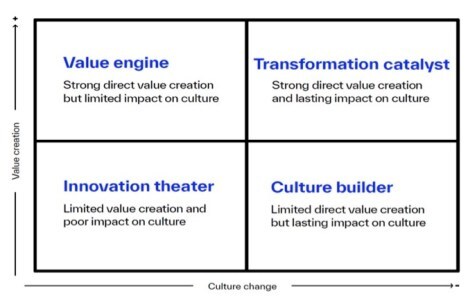

The playbook describes the three pillars of corporate innovation: Innovation Portfolios, Innovation Programs and a Culture of Innovation. Under each pillar, the playbook describes three questions that leaders and teams can ask to evaluate whether their company has the right innovation ecosystem in place.

Innovation Portfolio: what are your company’s portfolio of innovation projects?

Innovation Portfolio: what are your company’s portfolio of innovation projects?

Explore: Search for new value propositions and business models by designing and testing new business ideas rather than execution.

Exploit: Manage existing business models by scaling emerging businesses, renovating declining ones and protecting the successful ones.

Innovation Programs: how are your company’s innovation programs are structured and managed.

Innovation Programs: how are your company’s innovation programs are structured and managed.

To close the innovation capability gap, companies can evaluate their innovation programs by asking whether they’reinnovation theater or producing tangible results for the company.

Value Creation: Creating new products, services, value propositions and business models. These programs invest in and manage innovation projects that create value by producing new growth or cost savings.Culture Change: Transforming the company to establish an innovation culture. This may include new processes, metrics, incentive systems, or changing organizational structures. These transformations help the company innovate in a consistent and repeatable way. Innovation Culture: What are the blockers and enablers of innovation in your company –

Innovation Culture: What are the blockers and enablers of innovation in your company –

To overcome the innovation capability gap, companies need to create a culture that enables the right behaviors to produce world-class innovative outcomes. A reliable indicator of the quality of your innovation culture is how innovation teams would describe it. Is it a culture that is dominated by blockers of innovation or enablers of innovation?

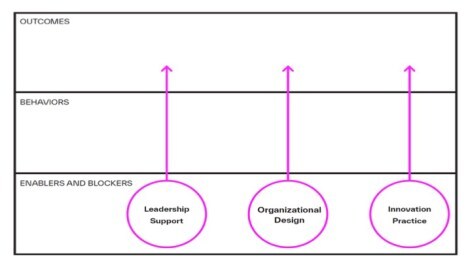

Leadership Support: How can corporate leaders have the biggest impact on innovation in terms of time spent, strategic guidance, and resource allocation.Organizational Design: How to give innovation legitimacy and power, the right incentives, and clear policies for collaboration with the core business.Innovation Practice: How to develop people’s innovation skills and experience and acquire the right innovation talent. How to ensure that we are using the right tools, processes, and metrics to test and adapt ideas in order to reduce risk.The three pillars of an innovation ecosystem:Innovation PortfoliosInnovation Programs a Culture of InnovationDownload the Osterwalder Playbook here

October 25, 2022

A Simple Map for Innovation at Scale

An edited version of this article previously appeared in the Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank website.

An edited version of this article previously appeared in the Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank website.

I spent last week at a global Fortune 50 company offsite watching them grapple with disruption. This 100+-year-old company has seven major product divisions, each with hundreds of products. Currently a market leader, they’re watching a new and relentless competitor with more money, more people and more advanced technology appear seemingly out of nowhere, attempting to grab customers and gain market share.

This company was so serious about dealing with this threat (they described it as “existential to their survival”) that they had mobilized the entire corporation to come up with new solutions. This wasn’t a small undertaking, because the threats were coming from multiple areas in multiple dimensions; How do they embrace new technologies? How do they convert existing manufacturing plants (and their workforce) for a completely new set of technologies? How do they bring on new supply chains? How do they become present on new social media and communications channels? How do they connect with a new generation of customers who had no brand loyalty? How to they use the new distribution channels competitors have adopted? How do they make these transitions without alienating and losing their existing customers, distribution channels and partners? And how do they motivate their most important asset – their people – to operate with speed, urgency, and passion?

The company believed they had a handful of years to solve these problems before their decline would become irreversible. This meeting was a biannual gathering of all the leadership involved in the corporate-wide initiatives to out-innovate their new disruptors. They called it the “Tsunami Initiative” to emphasize they were fighting the tidal wave of creative destruction engulfing their industry.

To succeed they realized this isn’t simply coming up with one new product. It meant pivoting an entire company – and its culture. The scale of solutions needed dwarf anything a single startup would be working on.

The company had hired a leading management consulting firm that helped them select 15 critical areas of change the Tsunami Initiative was tasked to work on. My hosts, John and Avika, at the offsite were the co-leads overseeing the 15 topic areas. The consulting firm suggested that they organize these 15 topic areas as a matrix organization, and the ballroom was filled with several hundred people from across their company – action groups and subgroups with people from across the company: engineering, manufacturing, market analysis and collection, distribution channels, and sales. Some of the teams even included some of their close partners. Over a thousand more were working on the projects in offices scattered across the globe.

John and Avika had invited me to look at their innovation process and offer some suggestions.

Are these the real problems?

This was one of the best organized innovation initiatives I have seen. All 15 topic had team leads presenting poster sessions, there were presenters from the field sales and partners emphasizing the urgency and specificity of the problems, and there were breakout sessions where the topic area teams brainstormed with each other. After the end of the day people gathered around the firepit for informal conversations. It was a testament to John and Avika’s leadership that even off duty people were passionately debating how to solve these problems. It was an amazing display of organizational esprit de corps.

While the subject of each of the 15 topic areas had been suggested by the consulting firm, it was in conjunction with the company’s corporate strategy group, and the people who generated these topic area requirements were part of the offsite. Not only were the requirements people in attendance but so was a transition team to facilitate the delivery of the products from these topic teams into production and sales.

However, I noticed that several of the requirements from corporate strategy seemed to be priorities given to them from others (e.g. here are the problems the CFO or CEO or board thinks we ought to work on) or likely here are the topics the consulting firm thought they should focus on) and/or were from subject matter experts (e.g. I’m the expert in this field. No need to talk to anyone else; here’s what we need). It appeared the corporate strategy group was delivering problems as fixed requirements, e.g. deliver these specific features and functions the solution ought to provide.

Here was a major effort involving lots of people but missing the chance to get the root cause of the problems.

I told John and Avika that I understood some requirements were known and immutable. However, when all of the requirements are handed to the action teams this way the assumption is that the problems have been validated, and the teams do not need to do any further exploration of the problem space themselves.

Those tight bounds on requirements constrain the ability of the topic area action teams to:

Deeply understand the problems – who are the customers, internal stakeholders (sales, other departments) and beneficiaries (shareholders, etc.)? How to adjudicate between them, priority of the solution, timing of the solutions, minimum feature set, dependencies, etc.Figure out whether the problem is a symptom of something more importantUnderstand whether the problem is immediately solvable, requires multiple minimum viable products to test several solutions, or needs more R&DI noticed that with all of the requirements fixed upfront, instead of having a freedom to innovate, the topic area action teams had become extensions of existing product development groups. They were getting trapped into existing mindsets and were likely producing far less than they were capable of. This is a common mistake corporate innovation teams tend to make.

I reminded them that when team members get out of their buildings and comfort zones, and directly talk to, observe, and interact with the customers, stakeholders and beneficiaries, it allows them to be agile, and the solutions they deliver will be needed, timely, relevant and take less time and resources to develop. It’s the difference between admiring a problem and solving one.

As I mentioned this, I realized having all fixed requirements is a symptom of something else more interesting – how the topic leads and team members were organized. From where I sat, it seemed there was a lack of a common framework and process.

Give the Topic Areas a Common Framework

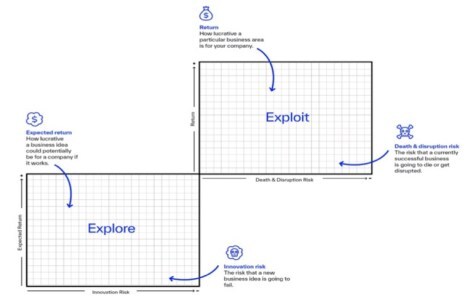

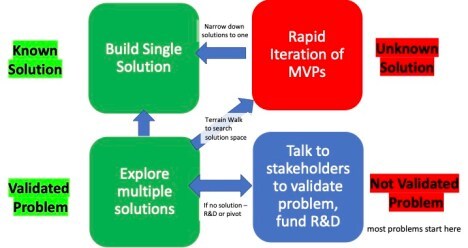

I asked John and Avika if they had considered offering the topic action team leaders and their team members a simple conceptual framework (one picture) and common language. I suggested this would allow the teams to know when and how to “ideate” and incorporate innovative ideas that accelerate better outcomes. The framework would use the initial corporate strategy requirements as a starting point rather than a fixed destination. See the diagram.

I drew them a simple chart and explained that most problems start in the bottom right box.

These are “unvalidated” problems. Teams would use a customer discovery process to validate them. (At times some problems might require more R&D before they can be solved.) Once the problems are validated, teams move to the box on the bottom left and explore multiple solutions. Both boxes on the bottom are where ideation and innovation-type of problem/solution brainstorming are critical. At times this can be accelerated by bringing in the horizon 3, out-of-the-box thinkers that every company has, and let them lend their critical eye to the problem/solution.

These are “unvalidated” problems. Teams would use a customer discovery process to validate them. (At times some problems might require more R&D before they can be solved.) Once the problems are validated, teams move to the box on the bottom left and explore multiple solutions. Both boxes on the bottom are where ideation and innovation-type of problem/solution brainstorming are critical. At times this can be accelerated by bringing in the horizon 3, out-of-the-box thinkers that every company has, and let them lend their critical eye to the problem/solution.

If a solution is found and solves the problem, the team heads up to the box on the top left.

But I explained that very often the solution is unknown. In that case think about having the teams do a “technical terrain walk.” This is the process of describing the problem to multiple sources (vendors, internal developers, other internal programs) debriefing on the sum of what was found. A terrain walk often discovers that the problem is actually a symptom of another problem or that the sources see it as a different version of the problem. Or that an existing solution already exists or can be modified to fit.

But often, no existing solution exists. In this case, teams could head to the box on the top right and build Minimal Viable Products – the smallest feature set to test with customers and partners. This MVP testing often results in new learnings from the customers, beneficiaries, and stakeholders – for example, they may tell the topic developer that the first 20% of the deliverable is “good enough” or the problem has changed, or the timing has changed, or it needs to be compatible with something else, etc. Finally, when a solution is wanted by customers/beneficiaries/stakeholders and is technically feasible, then the teams move to the box on the top left.

The result of this would be teams rapidly iterating to deliver solutions wanted and needed by customers within the limited time the company had left.

Creative destruction

Those companies that make it do so with an integrated effort of inspired and visionary leadership, motivated people, innovative products, and relentless execution and passion.

Watching and listening to hundreds of people fighting the tsunami in a legendary company was humbling.

I hope they make it.

Lessons Learned

Creative destruction and disruption will happen to every company. How will you respond?Topic action teams need to deeply understand the problems as the customer understands them, not just what the corporate strategy requirements dictateThis can’t be done without talking directly to the customers, internal stakeholders, and partnersConsider if the corporate strategy team should be more facilitators than gatekeepersA light-weight way to keep topic teams in sync with corporate strategy is to offer a common innovation language and problem and solution framework

September 20, 2022

Mapping the Unknown – The Ten Steps to Map Any Industry

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step

Lǎozi 老子

I just had lunch with Shenwei, one of my ex-students who had just taken a job in a mid-sized consulting firm. After a bit of catching up I offered he was looking a bit lost. “I just got handed a project to help our firm enter a new industry – semiconductors. They want me to map out the space so we can figure out where we can add value.

When I asked what they already knew about it, they tossed me a tall stack of industry and stock analyst reports, company names, web sites, blogs. I started reading through a bunch of it and I’m drowning in data but don’t know where to start. I feel like I don’t know a thing.”

When I asked what they already knew about it, they tossed me a tall stack of industry and stock analyst reports, company names, web sites, blogs. I started reading through a bunch of it and I’m drowning in data but don’t know where to start. I feel like I don’t know a thing.”

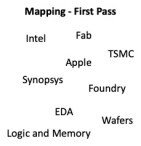

I told Shenwei I was happy for him because he had just been handed an awesome learning opportunity – how to rapidly understand and then map any new market. He gave me a “easy for you to say” look, but before h e could object I handed him a pen and a napkin and asked him to write down the names of companies and concepts he read about that have anything to do with the semiconductor business – in 30 seconds. He quickly came up with a list with 9 names/terms. (See Mapping – First Pass)

e could object I handed him a pen and a napkin and asked him to write down the names of companies and concepts he read about that have anything to do with the semiconductor business – in 30 seconds. He quickly came up with a list with 9 names/terms. (See Mapping – First Pass)

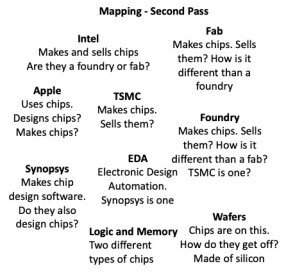

“Great, now we have a start. Now give me a few words that describe what they do, or mean, or what you don’t know about them.”

Don’t let the enormity of unknowns frighten you. Start with what you do know.After a few minutes he came up with a napkin sketch that looked like the picture in Mapping – Second Pass.  Now we had some progress.

Now we had some progress.

I pointed out he now had a starter list that not only contained companies but the beginning of a map of the relationships between those companies. And while he had a few facts, others were hypotheses and concepts. And he had a ton of unanswered questions.

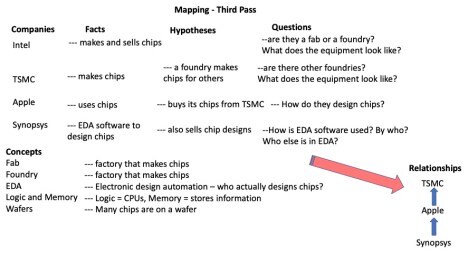

We spent the next 20 minutes deconstructing that sketch and mapping out the Second Pass list as a diagram (see Mapping – Third Pass.)

As you keep reading more materials, you’ll have more questions than facts. Your goal is to first turn the questions into testable hypotheses (guesses). Then see if you can find data that turns the hypotheses into facts. For a while the questions will start accumulating faster than the facts. That’s OK. Note that even with just the sparse set of information Shenwei had, in the bottom right-hand corner of his third mapping pass, a relationship diagram of the semiconductor industry was beginning to emerge.

Note that even with just the sparse set of information Shenwei had, in the bottom right-hand corner of his third mapping pass, a relationship diagram of the semiconductor industry was beginning to emerge.

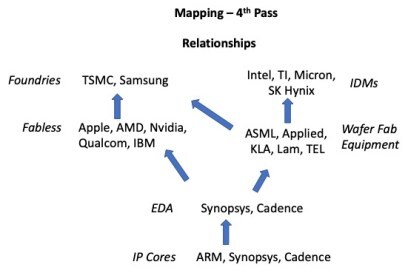

As the information fog was beginning to lift, I could see Shenwei’s confidence returning. I pointed out that he had a real advantage that his assignment was in a known industry with lots of available information. He quickly realized that he could keep adding information to the columns in the third mapping pass as he read through the reports and web sites.

Google and Google Scholar are your best friends. As you discover new information increase your search terms.My suggestion was to use the diagram in the third mapping pass as the beginning of a wall chart – either physically (or virtually if he could keep it in all in his head). And every time he learned more about the industry to update the relationship diagram of the industry and its segments. (When he pointed out that there were existing diagrams of the semiconductor industry he could copy, I suggested that he ignore them. The goal was for him to understand the industry well enough that he could draw his own map ab initio – from the beginning. And if he did so, he might create a much better one.)

When lunch was over Shenwei asked if it was OK if he checked in with me as he learned new things and I agreed. What he didn’t know was that this was only the first step in a ten-step industry mapping process.

Epilog

Over the next few weeks Shenwei shared what he had learned and sent me his increasingly refined and updated industry relationship map. (The 4th mapping pass showed up 48 hours later.) In exchange I shared with him the news that he was on step one of a ten step industry mapping program. Other the next few weeks he quickly built on the industry map to answer que

In exchange I shared with him the news that he was on step one of a ten step industry mapping program. Other the next few weeks he quickly built on the industry map to answer que stions 2 through 10 below.

stions 2 through 10 below.

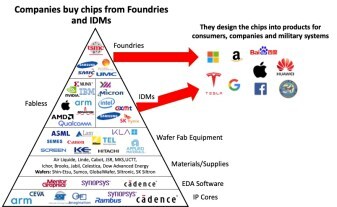

Two weeks later he handed his leadership an industry report that covered the ten steps below and contained a sophisticated industry diagram he created from scratch. A far cry from his original napkin sketch!

Six months later his work on this project convinced his company that there was a large opportunity in the semiconductor space, and they started a new practice with him in it. His work won him the “best new employee” award.

The Ten Steps to Map any Industry

Start by continuously refining your understanding of the industry by diagramming it. List all the new words you encounter and create a glossary in your own words. Start collecting the best sources of information you’ve read.Basic Industry Understanding

Diagram the industry and its segmentsStart with anythingBuild your learning by successive iterationWho are the key suppliers to each segment?How does this industry feed into the larger economy?Create a glossary of industry unique termsCan you explain them to others? Are there analogies to other markets?Who are the industry experts in each segment? For the entire industry?Economic experts? E.g. industry analysts, universities, think tanksTechnology experts? E.g. universities, think tanksGeographic experts?Key Conferences, blogs, web sites, etc.What are the best opensource data feeds?What are the best paid resources?Overlay numbers, dollars, market share, Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) on all parts of the industry diagram. That will inform velocity and direction of the market.Detailed Industry Understanding

Who are the market leaders? New entrants? In revenue, market share and growth rateIn the U.S.Western countriesChinaUnderstand the technology flowsWho builds on top of whoWho is critical versus who can be substitutedUnderstand the economic flowsWho buys from who in this industryWho buys the output from this industry.How cyclical is demand?What are the demand drivers?How do companies inside each segment get funded? Any differences in capital requirements? Ease of starting, etc.If applicable, understand the personnel flow for each segmentDo people move just between their segments or up and down through the entire industry?Where do they get trained?The beginner’s forecasting method is to simply extrapolate current growth rates forward. But in today’s technology markets, discontinuities are coming fast and furious. Are there other technologies from adjacent markets will impact this one? (e.g. AI, Quantum, High performance computing,…?). Are there other global or national economic initiatives that could change the shape of the market?Forecasting

What’s changed in the last 10 years? 5 years?Diagram the past incarnations of the industryWhat’s going to change in the next 5 years?Any big insight on disruption?New entrants?New technology?New foreign suppliers?Diagram your model of the industry in 5 yearsSeptember 13, 2022

National Industrial Policy – Private Capital and The America’s Frontier Fund Steps Up

This article previously appeared in The National Interest.

This article previously appeared in The National Interest.

Last month the U.S. passed the CHIPS and Science Act, one of the first pieces of national industrial policy – government planning and intervention in a specific industry — in the last 50 years, in this case for semiconductors. After the celebratory champagne has been drunk and the confetti floats to the ground it’s helpful to put the CHIPS Act in context and understand the work that government and private capital have left to do.

Today the United States is in great power competition with China. It’s a contest over which nation’s diplomatic, information, military and economic system will lead the world in the 21st century. And the result is whether we face a Chinese dystopian future or a democratic one, where individuals and nations get to make their own choices. At the heart of this contest is leadership in emerging and disruptive technologies – running the gamut from semiconductors and supercomputers to biotech and blockchain and everything in between.

National Industrial Policy – U.S. versus China

Unlike the U.S., China manages its industrial policy via top-down 5-year plans. Their overall goal is to turn China into a technologically advanced and militarily powerful state that can challenge U.S. commercial and military leadership. Unlike the U.S., China has embraced the idea that national security is inexorably intertwined with commercial technology (semiconductors, drones, AI, machine learning, autonomy, biotech, cyber, semiconductors, quantum, high-performance computing, commercial access to space, et al.) They’ve made what they call military/civil fusion – building a dual-use ecosystem by tightly coupling their commercial technology companies with their defense ecosystem.

China has used its last three 5-year plans to invest in critical technologies (semiconductors, supercomputers, Al/ML, quantum, access to space, biotech.) as a national priority. They have built a sophisticated public/private financing ecosystem to support these plans. The Chinese technology funding ecosystem includes regional investment funds that exceed 700 billion dollars (what they call their Civil/Military Guidance Funds). These are investment vehicles in which central and local government agencies make investments that are combined with private venture capital and State-Owned Enterprises in areas of strategic importance. They are tightly coupling critical civilian companies to their defense ecosystem to help them develop military weapons and strategic surprises. (Tai Ming Cheung’s book is the best description of the system.)

The U.S. has nothing comparable.