Steve Blank's Blog, page 53

April 21, 2011

The LeanLaunch Pad at Stanford – Class 6: Channel Hypotheses

The Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment with a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. With two weeks and two more updates to go, this post is part six. Parts one through five are here, Syllabus is here.

While we've been pushing hard on the teams, this week the teaching team was about to get its socks blown off. All the teams were showing us what agile looked like, but this week several would remind us what focused and relentless really meant.

Week 6 of the class.

Last week the teams tested their hypotheses about Customer Relationships (how do they get, keep and grow customers.) This week they were testing their hypotheses about the sales "Channel" – how a company delivers its value proposition (i.e. its product or service) to its customers. There are two major channels: physical channels and virtual (web/mobile) channels. Physical channels include Direct Sales, Rep Firms, Systems Integrators, Value-added Resellers, Distributors, Dealers, Mass Merchandisers, and Original Equipment Manufacturers. Virtual channels include Dedicated e-commerce, Two-step e-distribution and Aggregators.

The Nine Teams Present

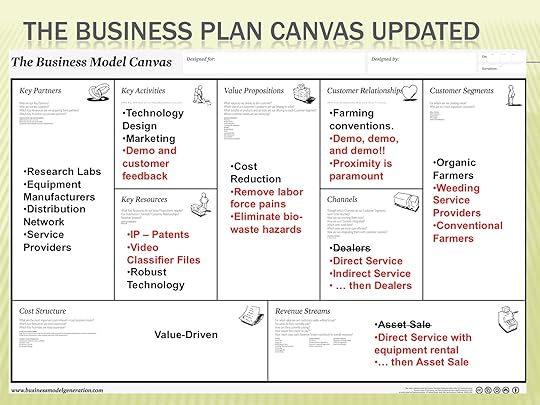

The first team up was Autonomow, the robotic mower farm weeder. They believed tthey would sell their robotic weeder to farm equipment dealers and distributors so they interviewed 9 more of them this week. They found that sales to this channel would require a demonstration, and that dealers would have to demo the robotic weeders to the customers. They learned that farmers expect personal and timely service/support. Relationships and trust are important.

Their week 6 business model now looked like this:

All that we expected. But what they showed us next astonished all of us.

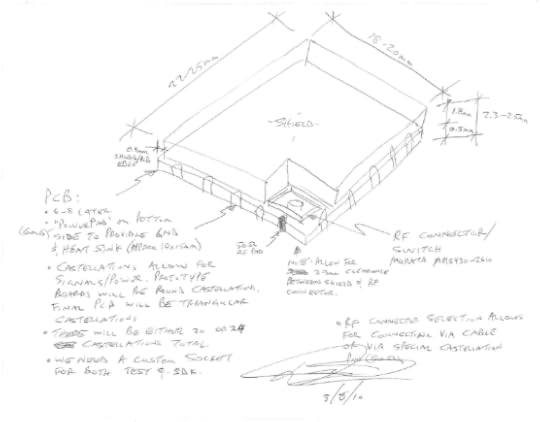

Last week we challenged the team that unless they developed hardware which could tell the difference between a weed and a plant, their business model would be just another set of PowerPoint slides. We expected that at best in the final 3 weeks of class they might build prototype hardware on a lab bench. Instead they built the prototype of an entire weeding robot – in one week. They called it the CarrotBot.

CarrotBot was their research platform to gather data for machine vision/machine learning. They wanted to test: can a machine tell the difference between a weed and a plant in the field? What about under different lighting and soil conditions? Could they train a machine to do this automatically?

The CarrotBot had a high-speed machine vision camera and a high-resolution camera for visual data as well as a panning LIDAR system for sub-millimeter depth measurement. Encoders on the drive motors and RTK-GPS measured precision position and velocity. After they validated the weed detection system, the next step was to arm the CarrotBot with a weed kill system (clove oil, high pressure steam/water, or lasers).

The Autonomow team worked 20-hour days, Wednesday – Monday. (On Wednesday night they got the idea to build a robot. On Thursday they ordered the parts, received them Friday, then built the robot over the next three days. (They got help from another student researcher in robotics and machine learning in the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab.)

Their goal is to deploy CarrotBot this week in the farm fields in Avenal, California, on the way to the World Ag Expo.

I'm sure the teaching team gave them some advice, but we were so busy trying to hide our jaws hitting the floor I can't remember what it was..

I'm sure the teaching team gave them some advice, but we were so busy trying to hide our jaws hitting the floor I can't remember what it was..

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

Next was D.C. Veritas, the team building a low cost residential wind turbine. This week the team got religion and decided that a major pivot was in order. They ditched the residential market as they realized that a more accessible and profitable customer segment(s) were cities, lighting companies and utilities.

In talking to customers, the team found that cities are actively trying to reduce street lighting costs (retrofitting with LEDs, turning off lights, and charging streetlight fees.) If they redesigned their the wind turbine, it could be embedded into street and highway light poles. Not only could the turbine power the street lights, but it would make excess energy that could be sold back into the grid. Their value proposition had now changed from a wind turbine supplier to homes, to a distributed power supplier to cities and utilities.

Their channel was still direct sales, but now selling to cities allowed them to sell multiple turbines with a larger order size.

D.C. Veritas estimated that their new total available market was 13 million city street lights in the U.S., plus an unknown number of highway lights.

The feedback from the teaching team was that with a new customer segment identified the team was now in a race against time to provide a meaningful business model before the class ended.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

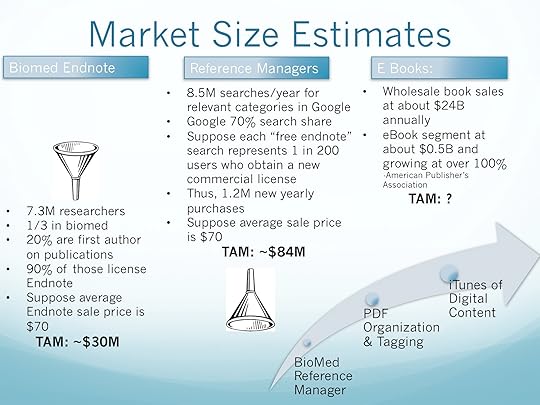

PersonalLibraries was focused on creating a reference management system for discovering, organizing and citing researchers' readings. Last week the teaching team had suggested that they ought to "run away from the academic researcher market as fast as possible." Yet like passionate entrepreneurs, the team ignored our advice and pressed on. (To be fair, one of their team members had built the software and worked on it for awhile.)

This team spoke with 10 more customers and potential channel partners. They heard: "the academic market is terribly small, charging $1 a user for a high volume academic site license is unrealistic, the cost of reaching lab managers is prohibitive, despite poor economics there are many niche competitors, and academic software is a "dinosaur" business with lots of competitors in the space because they started there years ago and aren't able to pivot out." Ouch!

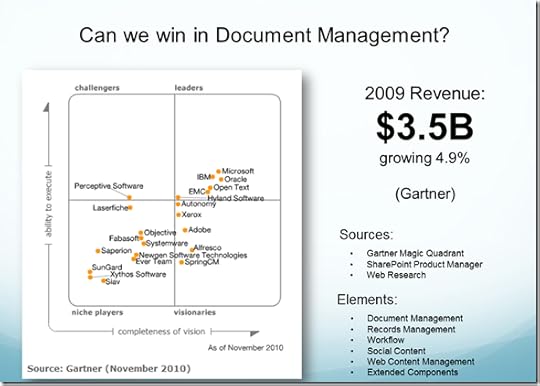

With the evidence piling up, the team is now starting to think about pivoting to other customer segments and/or other pricing models. Should they create a freemium version of their current product? Should they look at the Document Management market?

Time is running out for the PersonalLibraries team. Two more weeks of the class to go. Take a look at their presentations and you decide – what should they do?

Time is running out for the PersonalLibraries team. Two more weeks of the class to go. Take a look at their presentations and you decide – what should they do?

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

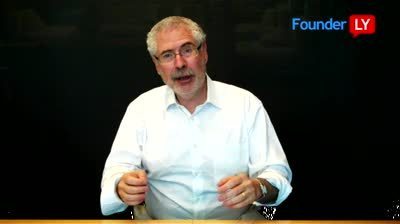

The Agora Cloud Services team, (a marketplace for cloud computing) spent the week testing their channel hypotheses and further refined their business model canvas. They believed they were going to have inside sales reps, third party cloud computing consultants and their own web channel sales.

The team interviewed another 9 customers and industry experts and attended the Amazon Web Services meetup in San Francisco.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

The Week 6 Lecture: Revenue Model

This week's lecture covered the Revenue Model including questions like these: How does your company make money? What are your customers going to pay for? What types of revenue streams are there? How does the web differ from other channels?

Our assignment for the teams for next week: What are the key financials metrics for your business model? If you have more than one product, how will you package it into various offerings? How will you price the offerings? What is the customer lifetime value? How are your competitors pricing? Each team has to test their pricing in front of 100 customers on the web or 10-15 customers non-web. And they had to assemble an income statement for the their business model.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

———

Most of the teams were doing great. A few were doing spectacularly well. One other team in the class, Jointbuy (an online platform allowing buyers to purchase products in bulk) turned in an equally extraordinary effort. When testing demand creation in their multi-sided business model, they couldn't get enough sellers to their site. So they sent out mass emails to create demand. They certainly got noticed – as they had hijacked the Stanford email system to send 16,000 emails before they got shut down.

Much like startups in the real world, team performance in entrepreneurship classes seems to follow a Pareto distribution.

Two weeks to go. Let's see how tenacity, sleepless nights, customer feedback and agile iteration change the final outcome.

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

April 19, 2011

Mentors, Coaches and Teachers

When the student is ready, the master appears.

Buddhist Proverb

Lots of entrepreneurs believe they want a mentor. In fact, they're actually asking for a teacher or a coach. A mentor relationship is a two-way street. To make it work, you have to bring something to the party.

A Question from the Audience

Recently when I was at a conference taking questions from the audience, I got a question that I had never heard before. Someone asked, "How do I get you, or someone like you to become my mentor?" It made me pause (actually cringe.) As I gathered my thoughts, I realized that I've never thought much about the mentors I had, how I got them, and the difference between mentors, coaches and teachers.

Teachers

What I do today is teach. At Stanford and Berkeley, I have students, with classes and office hours. For the brief time in the quarter I have students in my class, at worst I impart knowledge to them. At best, I try to help my students to discover and acquire the knowledge themselves. I try to engage them to see the startup world as part of a larger pattern; the lifecycle of how companies are born, grow and die. I attempt to offer them both theory, as well as a methodology, about building early stage ventures. And finally, I have them experience all of this first hand by teaching them theory side-by-side with immersive hands-on using Customer Development to find a business model.

At times, the coffees, lunches and phone calls I have with current and past students are also a form of teaching. Most of the time students come with, "Here's the problem I have. Can you help me?" Usually, I'll give a direct answer, but sometimes my answer is a question.

In both cases, inside or outside the classroom, I consider those activities as teaching. At least for me, mentorship is something quite different.

Mentors

As an entrepreneur in my 20's and 30's, I was lucky to have four extraordinary mentors, each brilliant in his own field and each a decade or two older than me. Ben Wegbreit taught me how to think, Gordon Bell taught me what to think about, Rob Van Naarden taught me how to think about customers and showed me how to turn thinking into direct, immediate and outrageous action.

At this time in my life, I was the world's biggest pain in the rear, lessons needed to be communicated by baseball bat, yet each one of these people not only put up with me, but also engaged me in a dialog of continual learning. Unlike coaching, there was no specific agenda or goal, but they saw I was competent and open to learning and they cared about me and my long-term development. I'm not sure it was a conscious effort on their part, (I know it wasn't on mine,) but it continued for years, and in some cases (with my partner Ben Wegbreit) for decades. What is interesting in hindsight is that although the relationship continued for a long time, neither of us explicitly acknowledged it.

Now I realize that what made these relationships a mentorship is this: I was giving as good as I was getting. While I was learning from them – and their years of experience and expertise – what I was giving back to them was equally important. I was bringing fresh insights to their data. It wasn't that I was just more up to date on the current technology, markets or trends, it was that I was able to recognize patterns and bring new perspectives to what these very smart people already knew. In hindsight, mentorship is a synergistic relationship.

Like every good student/teacher and mentor/mentee relationship, over time the student became the teacher, and this phase of relationship ends.

How Do I Find A Mentor

All this was running through my head as I tried to think of how to answer the question from the audience.

Finally I replied, "At least for me, becoming someone's mentor means a two-way relationship. A mentorship is a back and forth dialog – it's as much about giving as it is about getting. It's a much higher-level conversation than just teaching. Think about what can we learn together? How much are you going to bring to the relationship?"

If it's not much, than what you really want/need is a teacher, not a mentor. If it's a specific goal or skill you want to achieve, hire a coach, but if you're prepared to give as good as you get, then look for a mentor.

But never ask. Offer to give.

Lessons Learned

Teachers, coaches and mentors are each something different.

If you want to learn a specific subject find a teacher.

If you want to hone specific skills or reach an exact goal hire a coach.

If you want to get smarter and better over your career find someone who cares about you enough to be a mentor.

Filed under: Family/Career, Teaching

April 15, 2011

The LeanLaunch Pad at Stanford – Class 5: Customer Relationship Hypotheses

The Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. This post is part five. Parts one through four are here, Syllabus is here.

Week 5 of the class.

Last week the teams were testing their hypotheses about their Customers (who are the users, payers, buyers, etc.) This week they were testing one of the most confusing sections of a company's business model – Customer Relationships - the activities used to "Get, Keep and Grow" customers in a physical or virtual (web or mobile) channel. (Internet investor Dave McClure coined the acronym "AARRR," to remember the parts of Customer Relationships on the web.)

Many of the students had heard phrases that fall under Customer Relationships before; "customer acquisition, SEO/SEM, public relations, Social Network, Advertising, Loyalty programs, cross-sell and up-sell" etc., but now they were actually trying to implement it. (If their team was a web or mobile app they actually had to buy Google or Facebook ads and create demand.)

For some of the teams their expectation was if they built the product customers will come. Filing into the classroom I could tell that for some reality had just come crashing down on them. Seeing the lack of customer interest for the first time is always depressing. (The goal of the class was to get them to understand that in a startup, that was the norm not the exception. And to teach them a methodology of what to do about it.) It was making some of the teams question other parts of their business model (did they have the right customer, did they have the right product features to meet customer needs, etc.)

The Nine Teams Present

The first team to present was D.C. Veritas, the team building a low cost, residential wind turbine. During the week they interviewed 7 more companies and consultants, developed case studies for 20 different cities in 5 states, and finalized the bill of materials for the wind turbine. But the big project for the week was testing and analyzing Customer Acquisition Costs. The team put together their sales funnel and started testing demand.

The results were disappointing. The most optimistic estimates showed that the residential wind turbine market was less than $20m in year 5 and the costs to acquire the customers made this a money-losing business.

After regrouping the team decided that a major pivot was in order. Perhaps residential customers were the wrong target? Maybe the wind turbine they were building was better suited to a different customer segment? They had gotten feedback from consultants and industry experts that cities and utilities might be a more receptive audience. What if they redesigned the wind turbine to be embedded into street and highway light poles? Then they could serve cities, lighting companies and utilities. Using the business model canvas, the changes to their business were obvious.

(BTW, our definition of a Pivot: it's when you significantly modify one or more of the business model building blocks.)

Three more weeks to go. Can the D.C. Veritas team discover whether there's a real opportunity for their wind turbine in cities? The teaching team observed that the next few weeks are going to be interesting. Time to dig in and find out.

Our next team up was Autonomow, the robot lawn mower farm weeder. Last week they had pivoted from customers who needed large areas mowed, to organic farmers who needed lower costs for weeding. In this weeks foray into farm country they spoke to five farm implement dealers and interviewed yet another farmer. However, their primary focus was thinking through how they would "get" their initial customers. In talking to farmers and farm equipment dealers they learned the farm-specific places to create demand; trade shows like the World Ag Expo and magazines such as Vegetable Grower, Ag Source, Farm Equipment and Tractor House. The team then put together a specific budget for initial demand creation.

The teaching team suggested that was the research to date was great, but until they built a robot that could actual tell the difference between a weed and a plant, this would just be a paper exercise. They were engineers, certainly they could do better than that? The Autonomow team started thinking how they could prove that their paper business model was real.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

PersonalLibraries

Last week we asked the PersonalLibraries team: are there enough customers to make this a business? So during the week they ran more hands-on user testing, A/B tests, landing page conversion tests, and bought Google Adwords.

The results were not impressive. The feedback they were getting was that the product was a "nice to have" but not a "hair-on-fire" product.

Our feedback was, that their data seemed to say that their current users don't want to spend money and will incur infinite support and infinite cost. Our suggestion was, "run away from the academic researcher market as fast as possible." We offered that the team might want to expand their user research to think about new features and verticals (document management, law firms, lab managers with discretionary budget, etc.)

Our feedback was, that their data seemed to say that their current users don't want to spend money and will incur infinite support and infinite cost. Our suggestion was, "run away from the academic researcher market as fast as possible." We offered that the team might want to expand their user research to think about new features and verticals (document management, law firms, lab managers with discretionary budget, etc.)

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

Agora Cloud Services

The Agora team ended last week wondering whether they were 1) a true marketplace for cloud computing, where they provide both matching and exchange capabilities for real-time trading. Or were they 2) an information exchange, providing matching services for cloud computing buyers and sellers, providing matching services. This week they answered the question by "punting." They decided they were going to start as a information services, move to brokering, then prediction and finally evolve into a true market. They interviewed another 8 buyers/sellers/industry experts.

Their results on whether they could acquire with Google Adwords was a bit sobering. Their first effort didn't get much traffic: 6 clicks out of ~2000 impressions. Worse yet, each of these clicks cost about a $1.00. Reason? They had been bidding on keywords that are too generic (e.g. cloud, ec2, Amazon Web Services, etc.)

Their ads of "Cloud Demand Prediction" hadn't been catching the eyes of people searching for these keywords. So they picked more specific keywords such as, (cloud comparison, best cloud providers, etc). And they created ads with specific headlines, such as "Too many cloud providers?", "Reduce your cloud spend", etc). They also increased their daily campaign budget to $20.00. What they found was that the keywords that did have traffic volume are extremely expensive. Depending on the keyword, the first page bids were between $5.00 to $25.00 per click! Ouch.

The team concluded that AdWords may not be the best channel to create demand.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

The Week 5 Lecture: Channel

Channels are how a company delivers its value proposition (i.e. its product or service) to its customers. There are two major channels – virtual (web/mobile) and physical channels – and the difference is dramatic. In one, physical goods move from a loading dock to a customer or a retail outlet. In another the product is offered and sold online. (If the product is itself bits, it may not only be sold online but is often also delivered or used on-line.)

Our lecture talked out how to choose the right sales channel, how the channel makes money, how they're motivated, and the economics of a sales channel.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

———

The lesson for the students this week was failure. What we wanted to teach them wasn't how to fail fast – any idiot can do that. We wanted to teach them how to recognize failure, learn from it, and pivot. It's not about failing fast – it's about learning faster. That's the lesson at the heart of the search for a repeatable and scalable business model.

Now deep into the class most of the teams are starting to rethink their initial assumptions. Which teams will continue to Pivot? Will any completely abandon their current business and pick a new one?

Stay tuned.

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

April 12, 2011

Risk and Culture in Silicon Valley

Om Malik runs Gigaom, probably the most interesting and accurate site on the blogosphere.

Om was kind enough to have me in for an interview. We covered a wide range of topics. This talk on Risk and Culture in Silicon Valley is a small 1 minute snippet of a longer interview on his blog.

Filed under: Family/Career, Teaching, Technology, Venture Capital

April 9, 2011

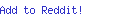

Entrepreneurs Are Artists

I wrote about entrepreneurs as artists in a previous post.

The FounderLy team interviewed me and got me to give a better explanation of what I was trying to say in this 2 minute video clip.

If you can't see the video click here.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Family/Career

April 8, 2011

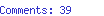

Flowery Words – True Ventures Founders Camp

The team at True Ventures was kind enough to invite me to speak at their Founders Camp. They pull in the founders of all their startups for 24 hours of activities, speakers, and discussions. I was blown away by the raw talent of these teams.

They had someone translating my words into a diagram as I spoke. (Click on it for the full effect.)

Filed under: Venture Capital

April 7, 2011

One Hand Clapping – Entrepreneurship In Ann Arbor, Michigan

I spent a few days in March in Ann Arbor Michigan as a guest of Professor Thomas Zurbuchen, Associate Dean for Entrepreneurial Programs, and Doug Neal, Director of Center for Entrepreneurship in the Engineering School at the University of Michigan.

I gave a keynote on entrepreneurship to MPowered, the student Entrepreneurship Organization, spoke on a panel on Entrepreneurship and the Aerospace Industry, and gave another keynote at the Ann Arbor New Tech Meetup and A2Geeks, the regional startup network.

I got smarter about engineering and innovation in "flyover country", met some wonderful people and shared some thoughts about what it might take to spark an innovation cluster in Ann Arbor.

This post is a personal view of what I saw in Ann Arbor — in no way does it represent the views of the fine institutions I teach at. Read this with all the usual caveats: visiting a place for a few days doesn't make you an expert, I'm not an economist, and the odds are I misunderstood or misinterpreted what I saw or just didn't see enough.

One Hand Clapping - Creating an Innovation Cluster – The Ann Arbor Experiment

In my short time in Ann Arbor, I spent time meeting with:

Faculty; I met with the Dean of Engineering, held faculty lunches and roundtables in the Engineering School, and met one-on-one with several engineering and med school faculty who wanted to turn their research into a company.

Students; presented to entrepreneurship classes teaching technology-driven Scalable startups as well as students interested in Social Entrepreneurship. Held office hours and met lots of passionate students with great ideas.

Business School, met with the entrepreneurship center in the Business School,

Entrepreneurs; presented to MPowered the University of Michigan student Entrepreneurship Organization, the Ann Arbor New Tech Meetup and A2Geeks, the regional startup network (talk here.)

Venture Capital; met with the local hardware/software venture capital firm.

Incubators: toured the TechArb, the engineering student accelerator, and the Michigan Venture Center in the University's Tech Transfer Office

The good news:

Entrepreneurship and innovation has been embraced big time at U of M. The Engineering School has 5,600 undergrads and 3,000 graduate students. It' s probably no coincidence that the Dean of the Engineering School founded a company and gets what "startup" means first hand. The Center for Entrepreneurship in the Engineering School is akin to Stanford's STVP program. It offers 35 entrepreneurship courses.

Everyone I met in this program "gets" the principles of Agile, Lean and Customer Development big time. The TechArb is the engineering student accelerator/incubator (cofounded by the local VC) and also embraces these ideas. Finally, I was impressed to find a robust local entrepreneurial community centered around A2Geeks and the Tech Brewery (after I met Dug Song I understood why.)

(I didn't have enough time to connect with the entrepreneurial groups working on medical devices and life sciences, but they are another big component of the startup pool coming out of the University.)

What needs work:

It's been 33 years since I was last in Ann Arbor. (I call it the best school I was ever thrown out of.) I was incredibly impressed with how far the University has inculcated innovation into the fabric of the Engineering School. However the challenges that still needed to be addressed were pretty apparent.

You Can't Start a Fire Without A Spark – A Lack of Venture Capital

For an Engineering School so focused on innovation and startups the lack of sufficient numbers of venture capitalists in the local community for Cleantech, hardware, Web/Mobile apps and aerospace was noticeable. Given the interesting things going on in the engineering labs I visited and the startups I met, one would have thought the school would have been crawling with VC's fighting over deals. Instead it seems that students who graduate simply pick up a plane ticket with their diploma. (Of course, some do stay. The spin-outs from Center of Entrepreneurship are impressive. Many of those companies are still Ann Arbor, but the ecosystem is a limiting factor.)

While one can't recreate all the happy accidents that made Silicon Valley, it doesn't take a rocket scientist to realize that it's the combination of technology entrepreneurs and risk capital that are two of the essential ingredients in any cluster. (I list some of the others in the diagram below.)

Innovation Cluster - What's Missing in Ann Arbor

Therefore the lack of critical mass in Venture Investors in Ann Arbor was palpable – and incomprehensible. This place could support at least one or two seed funds like 500 Startups, and a couple of True Venture/Floodgate-type of VC's as well as more Cleantech investors. Getting them in Ann Arbor would solve the other missing piece; the lack of a startup culture.

A Lack of a Startup Culture in the Community

Visiting Silicon Valley you can't mistake that its primary business is innovation. In Ann Arbor and southeast Michigan entrepreneurship is a small part of a more diverse business culture. One of the characteristics of a cluster is that it isn't hard to find other like-minded individuals. In Ann Arbor, they're scattered in between the auto industry, biotech, hospital workers, etc. As a consequence Ann Arbor lacks the culture of risk-taking and respect for failure critical in an innovation cluster. You see it in the existing angel groups and VC's. They feel more like banks than risk capital. And that lack of tolerance for failure and comfort with the status quo gets fed back to the entrepreneurs. Getting a few experienced super-angels and/or VC's seeding 5-10 Lean Startup deals here a year, with a couple of Cleantech/energy deals as well, could kickstart the culture.

Not My Problem

The interesting thing is that no one seems to own the problem. The University of Michigan tech transfer office has an incubator but 1) mixes software, hardware, med devices and life sciences deals in the same program, and 2) takes no ownership of figuring out how to get a risk capital ecosystem in place. Surprisingly, the same with the entrepreneurship center in the Business School. I would have thought they'd be leading the charge.

The new governor of Michigan, Rick Snyder was a venture capitalist in Ann Arbor, so I'm surprised he hasn't jawboned some combination of Michigan alumni working in venture capital in Silicon Valley to return, and paired them with the old-school money from the Auto industry, that's hiding under mattresses. (If the old money doesn't get the new mobile/web app space, note that new money is pouring into Cleantech/energy VC funds in the Valley. Silver Lake Kraftwerk's Fund just raised $1.3 billion for a Cleantech/Energy growth fund. Bet Ann Arbor and the Detroit Metro area have a few startups in that space. Where are the investors?)

—-

The real test of a cluster "catching fire" is not when it provides local employment, but when people from outside the area start coming to work and invest there.

These guys are this close to making it happen. It would be a shame if it didn't.

Lessons Learned

U of M has a College of Engineering dean who "gets it"

He's turned the school into an outward facing school, fostering an entrepreneurial and innovation culture

The Center for Entrepreneurship is on board with passionate faculty, innovative curriculum and excited students

The area has almost no experienced Angel, super Angel or Venture Capital (as we know it in Silicon Valley) for web/mobile apps, hardware and software

The lack of experienced risk capital means a lack of experienced mentors, coaches, and infrastructure.

Filed under: Teaching, Venture Capital

April 4, 2011

The LeanLaunch Pad at Stanford – Class 4: Customer Hypotheses

The Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. This post is part four. Part one is here, two is here and three is here. Syllabus is here.

Week 4 of the class.

Last week the teams were testing their hypotheses about their Value Proposition (their company's product or service.) This week they were testing who the customer, user, payer for the product will be (and discovering if they have a multi-sided business model, one with both buyers and sellers.) Many of them had heard the phrase "product/market fit" before, but now they were living it. And for some of the teams the halcyon days of "we're taking this class so we can just build our great product and get credit for it" had come to a screeching halt. The news from customers was not good.

Let the real learning begin.

The Nine Teams Present

This week, our first team up was PersonalLibraries (the team that had software to help researchers manage, share and reference the thousands of papers in their personal libraries.) Going into the first four weeks their business model hypotheses looked like this: Last week we told them team: 1) see if the market size was really large enough to support a business, and 2) to find that out they were going to have to

talk to more customers

outside of Stanford. So during the past week, the team got feedback from >60 researchers from

cold calls, in-person interviews, and a web survey. (We were impressed when we found that they did the in-person interviews by hiring usertesting.com for $39 to set up test scenarios, gave the users specific tasks to accomplish with their minimum viable product, videotaped the customer interactions and summarized customer likes and dislikes.) The good news was that customers said that their minimum viable product (easily organizing research papers) was correct. The bad news was that users would play with their product on-line for a while and leave and never return. Politely it was described as "poor customer retention" but in reality it was because the product was really hard to use.

Last week we told them team: 1) see if the market size was really large enough to support a business, and 2) to find that out they were going to have to

talk to more customers

outside of Stanford. So during the past week, the team got feedback from >60 researchers from

cold calls, in-person interviews, and a web survey. (We were impressed when we found that they did the in-person interviews by hiring usertesting.com for $39 to set up test scenarios, gave the users specific tasks to accomplish with their minimum viable product, videotaped the customer interactions and summarized customer likes and dislikes.) The good news was that customers said that their minimum viable product (easily organizing research papers) was correct. The bad news was that users would play with their product on-line for a while and leave and never return. Politely it was described as "poor customer retention" but in reality it was because the product was really hard to use.

But it was their market size survey that had the team (and us) even more concerned; last weeks "hot" market of biomed researchers looked like it was only $30m market, and the total available reference manager market was another $80M.The question was, even if they got the product right, were there enough customers to make it a business?

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

For next week, they decided to improve the product by adding more tutorials, do a 2nd Customer Survey and begin to create demand for their product with AdWords Value Prop Testing and Landing Page A/B Testing.

The feedback from the teaching team was that customer feedback seems to be saying that this product is a "nice to have" versus "got to have." Is the lack of excitement the MVP? Users? Is this a hobby or a business?

Agora Cloud Services

The Agora team started the week wondering whether they were 1) a true marketplace for cloud computing, where they provide both matching and exchange capabilities for real-time trading. Or were they 2) an information exchange, providing matching services for cloud computing buyers and sellers, providing matching services.

They began with a set of questions:

What are our new hypothesized value propositions?

Which segments have we identified and which do we want to narrow in on?

Which value added services do public clouds want to attract customers for?

Is there a certain segment of buyers that continually makes purchasing decisions (as opposed to only once at the very beginning of a company).

How can we attract buyers to our channel before they make purchasing decisions?

Longer-term work/planning: what other experiments should we be constructing

Sales process: buyer/ user/ influencer etc.? Demand generation?

The Agora team decided to formalize the customer discovery process by coming up with a set of Customer Discovery principles and questions that were as good as any I've seen.

They had 16 interviews with target customers (Zynga, Yahoo, VMware, Walmart, Zeconder, etc.) as well as channel partners and cloud industry technology consultants.

Agora was in a classic two-sided market (having both buyers and sellers. The Business Model Canvas is a great way to diagram it out. Each side of a market has it's own Value Proposition, Customer Segment and Revenue Model.) They learned that one their core customer hypothesis about their buyers, "startups would want to buy computing capacity on a "spot market" was wrong. Startups were actually happy with Amazon Web Services. The Agora team was beginning to believe that perhaps their ideal buyers are the companies that have to handle variable and unpredictable workloads.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

The Agora team left the week thinking that it was time for a Pivot: find cloud buyers and sellers who need to better predict demand. Perhaps in market segment: medium-large companies that do 3D modeling and life sciences simulations

The feedback from the teaching team "great Pivot" and very clear Lessons Learned presentation. Keep at it.

(For the teaching team one of the most important ways to track the teams progress was through the weekly blogs we made each team keep. This of this as their on-line diary. They hated doing it, but for us it added a window into their thinking process, allowed us to monitor how much work they were doing, and more importantly let us course correct when needed.

BTW, If I was on the board of a startup with a first time CEO I might even consider asking for this in the first year as they went through Customer Discovery. Yes it takes time, but I bet it's less than time than you would spend having coffee with an advisor each week.)

D.C. Veritas, was the team building a low cost, residential wind turbine that average homeowners could afford. From a slow start of customer interaction they made major progress in getting out for the building. This week they refined their target market by building a map of potential customers in the U.S. by modeling wind speed, energy costs, homeownership density and green energy incentives. The result was a density map of target customers. They then did face-to-face interviews with 20 customers and got data from 36 more who fit their archetype. They also interviewed two companies – Solar City and Awea in the adjacent market (residential photovoltaic's.)

If you can't see the slide presentation above, click here.

The teaching team offered that unlike solar panels which work anywhere, they've narrowed down the geographic areas where their wind turbine was economical. We observed that their total available market was getting smaller daily. After the next week figuring out demand creation costs, they ought to see if the homeowners were still a viable target market for residential wind turbines.

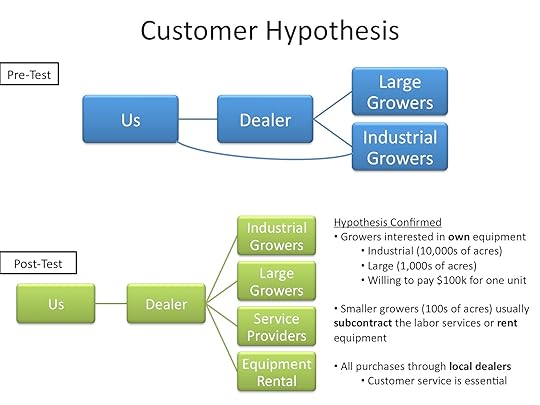

Autonomow, the robot lawn mower, came in with a major Pivot. Instead of a robotic lawn mower, they were now going to focus on robotic weeding and drop mowing as a customer segment. (Once you use the Business Model Canvas to keep score of Customer Discovery a Pivot is easy to define. A Pivot is when you substantively change one or more of the Business Model Canvas boxes.)

Talking to customers convinced the team that the need for robotic weeding was high, there was a larger potential market (organic crop production is doubling every 4 years and accelerating,) and they could make organic produce more affordable (labor cost reduction of 100 to 1) – and could possibly change the organic farming industry! And as engineers they believed weed versus crop recognition, while hard, was doable.

During the week the team drove the 160 miles round-trip to the Salinas Valley and had on-site interviews with two organic farms. They walked the fields with the farmers, hand-picked weeds with the laborers and got down into the details of the costs of brining in an organic crop.

They also talked by phone to organic farmers in Nebraska and the Santa Cruz mountains.

They acquired quantitative data by going through the 2008 Agricultural Census. Most importantly their model of the customer began to evolve.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Our feedback: could they really build a robot to recognize and weeds and if so how will they kill the weeds without killing the crops? And are farmers willing to take a risk on untested and radical ideas like robots replacing hand weeding?

The Week 4 Lecture: Customer Relationships

Our lecture this week covered Customer Relationships (a fancy phrase for how will your company create end user demand by getting, keeping and growing customers.) We pointed out that get, keep and grow customers are different for physical versus virtual channels. Then different again for direct and indirect channels. We offered some examples of what a sales funnel looked like. And we described the difference between creating demand for products that solve a problem versus those that fulfill a need.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

———

The biggest lesson for the students this week was the entire reason for the class – no business plan survives first contact with customers – as customers don't behave as per theory. As smart as you are, there's no way to predict that from inside your classroom, dorm room or cubicle. Some of the teams were coming to grips with it. Others would find reality crashing down harder a bit later.

Next week, each team tests its demand creation hypotheses. The web-based teams needed to have their site up and running and be driving demand to the site with real Search Engine Optimization and Marketing tests.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

March 31, 2011

Entrepreneurship is an Art not a Job

Some men see things as they are and ask why.

Others dream things that never were and ask why not.

George Bernard Shaw

Over the last decade we assumed that once we found repeatable methodologies (Agile and Customer Development, Business Model Design) to build early stage ventures, entrepreneurship would become a "science," and anyone could do it.

I'm beginning to suspect this assumption may be wrong.

Where Did We Go Wrong?

It's not that the tools are wrong, I think the entrepreneurship management stack is correct and has made a major contribution to reducing startup failures. Where I think we have gone wrong is the belief that anyone can use these tools equally well.

Entrepreneurship is an Art not a Job

For the sake of this analogy, think of two types of artists: those who creators and performers (think music composer versus members of the orchestra, playwright versus actor etc.)

Founders fit the definition of a creator: they see something no one else does. And to help them create it from nothing, they surround themselves with world-class performers. This concept of creating something that few others see – and the reality distortion field necessary to recruit the team to build it – is at the heart of what startup founders do. It is a very different skill than science, engineering, or management.

Entrepreneurial employees are the talented performers who hear the siren song of a founder's vision. Joining a startup while it is still searching for a business model, they too see the promise of what can be and join the founder to bring the vision to life.

Founders then put in play every skill which makes them unique – tenacity, passion, agility, rapid pivots, curiosity, learning and discovery, improvisation, ability to bring order out of chaos, resilience, leadership, a reality distortion field, and a relentless focus on execution – to lead the relentless process of refining their vision and making it a reality.

Both founders and entrepreneurial employees prefer to build something from the ground up rather than join an existing company. Like jazz musicians or improv actors, they prefer to operate in a chaotic environment with multiple unknowns. They sense the general direction they're headed in, OK with uncertainty and surprises, using the tools at hand, along with their instinct to achieve their vision. These types of people are rare, unique and crazy. They're artists.

Tools Do Not Make The Artist

When page-layout programs came out with the Macintosh in 1984, everyone thought it was going to be the end of graphic artists and designers. "Now everyone can do design," was the mantra. Users quickly learned how hard it was do design well (yes. it is an art) and again hired professionals. The same thing happened with the first bit-mapped word processors. We didn't get more or better authors. Instead we ended up with poorly written documents that looked like ransom notes. Today's equivalent is Apple's "Garageband". Not everyone who uses composition tools can actually write music that anyone wants to listen to.

"Well If it's Not the Tools Then it Must Be…"

The argument goes, "Well if it's not tools then it must be…" But examples from teaching other creative arts are not promising. Music composition has been around since the dawn of civilization yet even today the argument of what "makes" a great composer is still unsettled. Is it the process (the compositional strategies used in the compositional process?) Is it the person (achievement, musical aptitude, informal musical experiences, formal musical experiences, music self-esteem, academic grades, IQ, and gender?) Is it the environment (parents, teachers, friends, siblings, school, society, or cultural values?) Or is it constant practice (apprenticeship, 10,000 hours of practice?)

It may be we can increase the number of founders and entrepreneurial employees, with better tools, more money, and greater education. But it's more likely that until we truly understand how to teach creativity, their numbers are limited.

Lessons Learned

Founders fit the definition of an artist: they see – and create– something that no one else does

To help them move their vision to reality, they surround themselves with world-class performers

Founders and entrepreneurial employees prefer operating in a chaotic environment with multiple unknowns

These type of people are rare, unique and crazy

Not everyone is an artist

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development, Family/Career

March 29, 2011

Napkin Entrepreneurs

Faith is taking the first step even when you don't see the whole staircase.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

The barriers for starting a company have come down. Today the total available markets for new applications are hundreds of millions if not billion of users, while new classes of investors are popping up all over (angels, superangels, archangels, and even seraphim and cherubim have been spotted.)

Entrepreneurship departments are now the cool thing to have in colleges and universities, and classes on how to start a company are being taught over a weekend, a month, six weeks, and via correspondence course.

If the opportunity is so large, and the barriers to starting up so low, why haven't the number of scalable startups exploded exponentially? What's holding us back?

It might be that it's easier than ever to draw an idea on the back of the napkin, it's still hard to quit your day job.

Napkin Entrepreneurs

One of the amazing consequences of the low cost of creating web and mobile apps is that you can get a lot of them up and running simultaneously and affordably. I call these app development projects "science experiments."

These web science experiments are the logical extension of the Customer Discovery step in the Customer Development process. They're a great way to brainstorm outside the building, getting real customer feedback as you think through your ideas about value proposition/customer/demand creation/revenue model.

They're the 21st century version of a product sketch on a back of napkin. But instead of just a piece of paper, you end up with a site that users can visit, use and even pay for.

Ten of thousands of people who could never afford to start a company can now start several over their lunch break. And with any glimmer of customer interest they can decide whether they want to:

run it as a part-time business

commit full-time to build a "buyable startup" (~$5-$25 Million exit)

commit full-time and try to build a scalable startup

But it's important to note what these napkin projects/test are not. They are not a company, nor are they are a startup. Running them doesn't make you a founder. And while they are entrepreneurial experiments, until you actually commit to them by choosing one idea, quitting your day job and committing yourself 24/7 it's not clear that the word "founder or entrepreneur" even applies.

Lessons Learned

The web now allows you to turn your "back of the napkin" ideas into live experiments

Running lots of app experiments is a great idea

But these experiments are not a company and you're not a "founder". You're just a "napkin entrepreneur."

Founding a company is an act of complete commitment

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Teaching

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers