Steve Blank's Blog, page 54

March 25, 2011

The LeanLaunch Pad at Stanford – Class 3: Value Proposition Hypotheses

The Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. This post is part three. Part one is here, two is here. Syllabus is here.

Week 3 of the class and our teams in our Stanford Lean LaunchPad class were hard at work using Customer Development to get out of the classroom and test the first key hypotheses of their business model: The Value Proposition. (Value Proposition is a ten-dollar phrase describing a company's product or service. It's the "what are you building and selling?")

The Nine Teams Present

This week, our first team up was PersonalLibraries (the team that made software to help researchers manage, share and reference the thousands of papers in their personal libraries.)  To test its Value Proposition, the team had face-to-face interviews with 10 current users and non-users from biomedical, neuroscience, psychology and legal fields.

To test its Value Proposition, the team had face-to-face interviews with 10 current users and non-users from biomedical, neuroscience, psychology and legal fields.

What was cool was they recorded their interviews and posted them as YouTube videos. They did an online survey of 200 existing users (~5% response rate). In addition, they demoed to the paper management research group at the Stanford Intellectual Property Exchange project (a joint project between the Stanford Law School and Computer Science department to help computers understand copyright and create a marketplace for content). They met with their mentors, and refined their messaging pitch by attending a media training workshop one of our mentors held.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

In interviewing biomed researchers, they found one unmet need: the ability to cite materials used in experiments. This is necessary so experiments can be accurately reproduced. This was such a pain point, one scientist left a lecture he was attending to find the team and hand them an example of what the citations looked like.

The team left the week excited and wondering – is there an opportunity here to create new value in a citation tool? What if we could help scientists also bulk order supplies for experiments? Could we help manufacturers, as well, to better predict demand for their products, or perhaps to more effectively connect with purchasers?

The feedback from the teaching team was a reminder to see if the users they were talking to constitute a large enough market and had budgets to pay for the software.

Agora Cloud Services

The Agora team (offering a cloud computing "unit" that Agora will buy from multiple cloud vendors and create a marketplace for trading) had 7 face-to-face interviews with target customers, and spoke to a potential channel partner as well as two cloud industry technology consultants.

They learned that their hypothesis that large companies would want to lower IT costs by selling their excess computing capacity on a "spot market" didn't work in the financial services market because of security concerns. However sellers in the Telecom industries were interested if there was some type of revenue split from selling their own excess capacity.

On the buyers' side, their hypothesis that there were buyers who were interested in reduced cloud compute infrastructure cost turned out not to be a high priority for most companies. Finally, their assumption that increased procurement flexibility for buying cloud compute cycles would be important turned out to be just a "nice to have," not a real pain. Most companies were buying Amazon Web Services and were looking for value-added services that simplified their cloud activities.

If you can't see the slides above, click here.

The Agora team left the week thinking that the questions going forward were:

How do we get past Amazon as the default cloud computing service provider?

How viable is the telecom market as a potential seller of computing cycles?

We need to further validate buyer & seller value propositions

How do we access the buyers and sellers? What sort of sales structure and salesforce does it require?

Who is the main buyer(s) and what are their motivations?

Is a buying guide/matching service a superior value proposition to marketplace?

The feedback from the teaching team was a reminder that at times you may have a product in search of a solution.

D.C. Veritas D.C. Veritas, the team that was going to build a low cost, residential wind turbine that average homeowners could afford, wanted to provide a renewable source of energy at affordable price. They started to work out what features a minimum viable product their value proposition would have and began to cost out the first version. The Wind Turbine Minimum Viable Product would have a: Functioning turbine, Internet feedback system, energy monitoring system and have easy customer installation.

D.C. Veritas, the team that was going to build a low cost, residential wind turbine that average homeowners could afford, wanted to provide a renewable source of energy at affordable price. They started to work out what features a minimum viable product their value proposition would have and began to cost out the first version. The Wind Turbine Minimum Viable Product would have a: Functioning turbine, Internet feedback system, energy monitoring system and have easy customer installation.

The initial Bill of Material (BOM) of the Wind Turbine Hardware Costs looked like: Inverter (1000W): $500 (plug and play), Generator (1000W): $50-100, Turbine: ~$200, Output Measurement: ~$25, Wiring: $20 = Total Material Cost: ~$800-$850

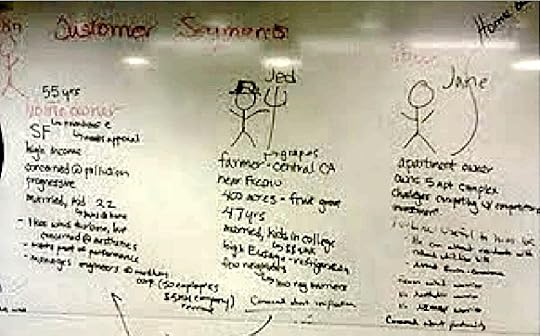

The team also went to the whiteboard and attempted a first pass at who the archetypical customer(s) might be.

To get customer feedback the team posted its first energy survey here and received 27 responses. In their first attempt at face-to-face customer interviews to test their value proposition and problem hypothesis (would people be interested in a residential wind turbine), they interviewed 13 people at the local Farmer's Market.

If you can't see the slide presentation above, click here.

The teaching team offered that out of 13 people they interviewed only 3 were potential customers. Therefore the amount of hard customer data they had collected was quite low and they were making decisions on a very sparse data set. We suggested (with a (2×4) that were really going to have to step up the customer interactions with a greater sense of urgency.The teaching team offered that out of 13 people they interviewed only 3 were potential customers. Therefore the amount of hard customer data they had collected was quite low and they were making decisions on a very sparse data set. We suggested (with a 2×4) that were really going to have to step up the customer interactions with a greater sense of urgency.

Autonomow

The last team up was Autonomow, the robot lawn mower. They were in the middle of trying to answer the question of "what problem are they solving?" They were no longer sure whether they were an autonomous mowing company or an agricultural weeding company.

They spoke to 6 people with large mowing needs (golf course, Stanford grounds keeper, etc.) They traveled to the Salinas Valley and Bakersfield and interviewed 6 farmers about weeding crops. What they found is that weeding is a huge problem in organic farming. It was incredibly labor intensive and some fields had to be hand-weeded multiple times per year.

They left the week realizing they had a decision to make – were they a "Mowing or Weeding" company?

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Our feedback: could they really build a robot to recognize and kill weeds in the field?

The Week 3 Lecture: Customers

Our lecture this week covered Customers – what/who are they? We pointed out the difference between a user, influencer, recommender, decision maker, economic buyer and saboteur. We also described the differences between customers in Business-to-business sales versus business-to-consumer sales. We talked about multi-sided markets and offered that not only are there multiple customers, but each customer segment has their own value proposition and revenue model.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Getting Out of the Building

Five other teams presented after these four. All of them had figured out the game was outside the building, with some were coming up to speed faster than others. A few of the teams ideas still looked pretty shaky as businesses. But the teaching team held our opinions to ourselves, as we've learned that you can't write off any idea too early. Usually the interesting Pivots happens later. The finish line was a ways off. Time would tell where they would all end up.

———

Next week each team test their Customer Segment hypotheses (who are their customers/users/decision makers, etc.) and report the results of face-to-face customer discovery. That will be really interesting.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

March 21, 2011

The Democratization of Entrepreneurship

I gave a talk at the Stanford Graduate School of Business as part of Entrepreneurship Week on the Democratization of Entrepreneurship. The first 11 minutes or so of the talk covers the post I wrote called "When It's Darkest, Men See the Stars."

In it I observed that the barriers to entrepreneurship are not just being removed. In each case they're being replaced by innovations that are speeding up each step, some by a factor of ten.

My hypotheses is that we'll look back to this decade as the beginning of our own revolution. We may remember this as the time when scientific discoveries and technological breakthroughs were integrated into the fabric of society faster than they had ever been before. When the speed of how businesses operated changed forever. As the time when we reinvented the American economy and our Gross Domestic Product began to take off and the U.S. and the world reached a level of wealth never seen before. It may be the dawn of a new era for a new American economy built on entrepreneurship and innovation.

If you can't see the video above, click here.)

If you've seen my other talks, after the first 11 minutes you can skip to ~1:04 with the Sloan versus Durant story and some interesting student Q&A. You can follow the talk along with the slides I used, below.

(If you can't see the slide presentation above, click here.)

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development

March 18, 2011

New Rules for the New Internet Bubble

Carpe Diem

We're now in the second Internet bubble. The signals are loud and clear: seed and late stage valuations are getting frothy and wacky, and hiring talent in Silicon Valley is the toughest it has been since the dot.com bubble. The rules for making money are different in a bubble than in normal times. What are they, how do they differ and what can startup do to take advantage of them?

First, to understand where we're going, it's important to know where we've been.

Paths to Liquidity: a quick history of the four waves of startup investing.

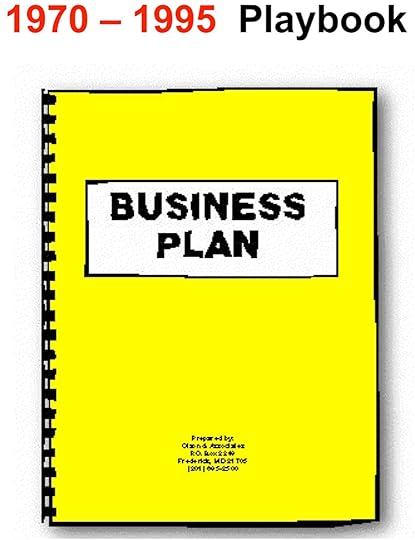

The Golden Age (1970 – 1995): Build a growing business with a consistently profitable track record (after at least 5 quarters,) and go public when it's time.

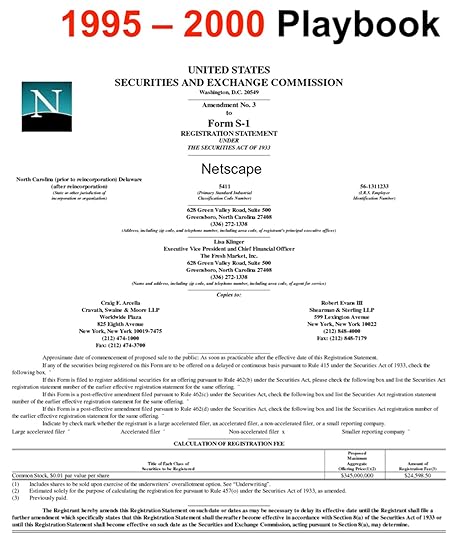

Dot.com Bubble (1995-2000): "Anything goes" as public markets clamor for ideas, vague promises of future growth, and IPOs happen absent regard for history or profitability.

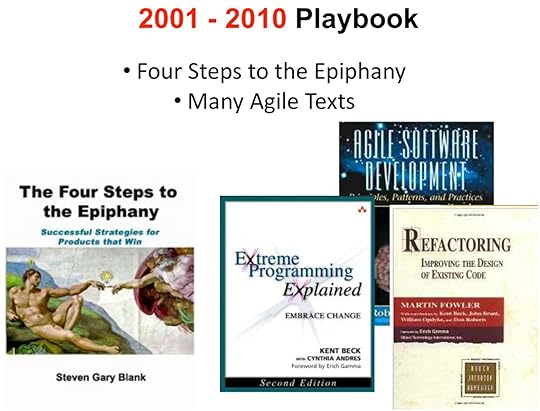

Lean Startups/Back to Basics (2000-2010): No IPO's, limited VC cash, lack of confidence and funding fuels "lean startup" era with limited M&A and even less IPO activity.

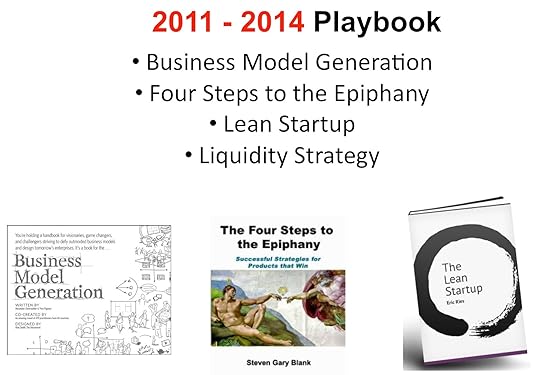

The New Bubble: (2011 – 2014): Here we go again….

(If you can't see the slide presentation above, click here.)

If you "saw the movie" or know your startup history, and want to skip ahead click here.

1970 – 1995: The Golden Age

VC's worked with entrepreneurs to build profitable and scalable businesses, with increasing revenue and consistent profitability – quarter after quarter. They taught you about customers, markets and profits. The reward for doing so was a liquidity event via an Initial Public Offering.

Startups needed millions of dollars of funding just to get their first product out the door to customers. Software companies had to buy specialized computers and license expensive software. A hardware startup had to equip a factory to manufacture the product. Startups built every possible feature the founding team envisioned (using "Waterfall development,") into a monolithic "release" of the product taking months or years to build a first product release.

The Business Plan (Concept-Alpha-Beta-FCS) became the playbook for startups. There was no repeatable methodology, startups and their VC's still operated like startups were simply a smaller version of a large company.

The world of building profitable startups ended in 1995.

August 1995 – March 2000: The Dot.Com Bubble

With Netscape's IPO, there was suddenly a public market for companies with limited revenue and no profit. Underwriters realized that as long as the public was happy snapping up shares, they could make huge profits from the inflated valuations. Thus began the 5-year dot-com bubble. For VC's and entrepreneurs the gold rush to liquidity was on. The old rules of sustainable revenue and consistent profitability went out the window. VC's engineered financial transactions, working with entrepreneurs to brand, hype and take public unprofitable companies with grand promises of the future. The goals were "first mover advantage," "grab market share" and "get big fast." Like all bubbles, this was a game of musical chairs, where the last one standing looked dumb and everyone else got absurdly rich.

Startups still required millions of dollars of funding. But the bubble mantra of get "big fast" and "first mover advantage" demanded tens of millions more to create a "brand." The goal was to get your firm public as soon as possible using whatever it took including hype, spin, expand, and grab market share – because the sooner you got your billion dollar market cap, the sooner the VC firm could sell their shares and distribute their profits.

Just like the previous 25 years, startups still built every possible feature the founding team envisioned into a monolithic "release" of the product using "Waterfall development." But in the bubble, startups got creative and shortened the time needed to get a product to the customer by releasing "beta's" (buggy products still needing testing) and having the customers act as their Quality Assurance group.

The IPO offering document became the playbook for startups. With the bubble mantra of "get big fast," the repeatable methodology became "brand, hype, flip or IPO".

2001 – 2010: Back to Basics: The Lean Startup

After the dot.com bubble collapsed, venture investors spent the next three years doing triage, sorting through the rubble to find companies that weren't bleeding cash and could actually be turned into businesses. Tech IPOs were a receding memory, and mergers and acquisitions became the only path to liquidity for startups. VC's went back to basics, to focus on building companies while their founders worked on building customers.

Over time, open source software the rise of the next wave of web startups and the embrace of Agile Engineering meant that startups no longer needed millions of dollars to buy specialized computers and license expensive software – they could start a company on their credit cards. Customer Development, Agile Engineering and the Lean methodology enforced a process of incremental and iterative development. Startups could now get a first version of a product out to customers in weeks/months rather than months/years. This next wave of web startups; Social Networks and Mobile Applications, now reached 100's of millions of customers.

Startups began to recognize that they weren't merely a smaller version of a large company. Rather they understood that a startup is a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. This meant that startups needed their own tools, techniques and methodologies distinct from those used in large companies. The concepts of Minimum Viable Product and the Pivot entered the lexicon along with Customer Discovery and Validation.

The playbook for startups became the Agile + Customer Development methodology with The Four Steps to the Epiphany and Agile engineering textbooks.

Rules For the New Bubble: 2011 -2014

The signs of a new bubble have been appearing over the last year – seed and late stage valuations are rapidly inflating, hiring talent in Silicon Valley is the toughest since the last bubble and investors are starting to openly wonder how this one will end.

Breathtaking Scale

The bubble is being driven by market forces on a scale never seen in the history of commerce. For the first time, startups can today think about a Total Available Market in the billions of users (smart phones, tablets, PC's, etc.) and aim for hundreds of millions of customers. And those customers may be using their devices/apps continuously. The revenue, profits and speed of scale of the winning companies can be breathtaking.

The New Exits

Rules for building a company in 2011 are different than they were in 2008 or 1998. Startup exits in the next three years will include IPO's as well as acquisitions. And unlike the last bubble, this bubble's first wave of IPO's will be companies showing "real" revenue, profits and customers in massive numbers. (Think Facebook, Zynga, Twitter, LinkedIn, Groupon, etc.) But like all bubbles, these initial IPO's will attract companies with less stellar financials, the quality IPO pipeline will diminish rapidly, and the bubble will pop. At the same time, acquisition opportunities will expand as large existing companies, unable to keep up with the pace of innovation in these emerging Internet markets, will "innovate" by buying startups. Finally, new forms of liquidity are emerging such as private-market stock exchanges for buying and selling illiquid assets (i.e. SecondMarket, SharesPost, etc.)

Tools in the New Bubble

Today's startups have all the tools needed for a short development cycle and rapid customer adoption – Agile and Customer Development plus Business Model Design.

The Four Steps to the Epiphany, Business Model Generation and the Lean Startup movement have become the playbook for startups. The payoff: in this bubble, a startup can actively "engineer for an acquisition." Here's how:

The Four Steps to the Epiphany, Business Model Generation and the Lean Startup movement have become the playbook for startups. The payoff: in this bubble, a startup can actively "engineer for an acquisition." Here's how:

Order of Battle

Each market has a finite number of acquirers, and a finite number of deal makers, each looking to fill specific product/market holes. So determining who specifically to target and talk to is not an incalculable problem. For a specific startup this list is probably a few hundred names.

Wide Adoption

Startups that win in the bubble will be those that get wide adoption (using freemium, viral growth, low costs, etc) and massive distribution (i.e. Facebook, Android/Apple App store.) They will focus on getting massive user bases first, and let the revenue follow later.

Visibility

During the the Lean Startup era, the advice was clear; focus on building the company and avoid hype. Now that advice has changed. Like every bubble this is a game of musical chairs. While you still need irrational focus on customers for your product, you and your company now need to be everywhere and look larger than life. Show and talk at conferences, be on lots of blogs, use social networks and build a brand. In the new bubble PR may be your new best friend, so invest in it.

Lessons Learned

We're in a new wave of startup investing – it's the beginning of another bubble

Rules for liquidity for startups and investors are different in bubbles

Pay attenton to what those rules are and how to play by them

Unlike the last bubble this one is not about selling "vision" or concepts.

You have to deliver. That requires building a company using Agile and Customer Development

Startups that master speed, tempo and Pivot cycle time will win

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

March 15, 2011

The LeanLaunch Pad at Stanford – Class 2: Business Model Hypotheses

Our new Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. This post is part two. Part one is here. Syllabus here.

By now the nine teams in our Stanford Lean LaunchPad Class were formed, In the four days between team formation and this class session we tasked them to:

Write down their initial hypotheses for the 9 components of their company's business model (who are the customers? what's the product? what distribution channel? etc.)

Come up with ways to test each of the 9 business model canvas hypotheses

Decide what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test. At what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct?

Consider if their business worth pursuing? (Give us an estimate of market size)

Start their team's blog/wiki/journal to record their progress during for the class

The Nine Teams Present

Each week every team presented a 10 minute summary of what they had done and what they learned that week. As each team presented, the teaching team would ask questions and give suggestions (at times pointed ones) for things the students missed or might want to consider next week. (These presentations counted for 30% of their grade. We graded them on a scale of 1-5, posted our grades and comments to a shared Google doc, and had our Teaching Assistant aggregate the grades and feedback to pass on to the teams.)

Our first team up was Autonomow. Their business was a robot lawn mower. Off to a running start, they not only wrote down their initial business model hypotheses but they immediately got out of the building and began interviewing prospective customers to test their three most critical assumptions in any business:

Value Proposition, Customer Segment and Channel. Their hypotheses when they first left the campus were:

Value Proposition: Labor costs in mowing and weeding applications are significant, and autonomous implementation would solve the problem.

Customer Segment: Owners/administrators of large green spaces (golf courses, universities, etc.) would buy an autonomous mower. Organic farmers would buy if the Return On Investment (ROI) is less than 1 year.

Channel: Mowing and agricultural equipment dealers

All teams kept a blog – almost like a diary – to record everything they did. Reading the Autonomow blog for the first week, you could already see their first hypotheses starting to shift: "For mowing applications, we talked to the Stanford Ground Maintenance, Stanford Golf Course supervisor for grass maintenance, a Toro distributor, and an early adopter of an autonomous lawn mower. For weeding applications, we spoke with both small and large farms. In order from smallest (40 acres) to largest (8000+ acres): Paloutzian Farms, Rainbow Orchards, Rincon Farms, REFCO Farms, White Farms, and Bolthouse Farms."

"We got some very interesting feedback, and overall interest in both systems," reported the team. "Both hypotheses (mowing and weeding) passed, but with some reservations (especially from those whose jobs they would replace!) We also got good feedback from Toro with respect to another hypothesis – selling through distributor vs. selling direct to the consumer."

The Autonomow team summarized their findings in their first 10 minute, weekly Lesson Learned presentation to the class.

Our feedback: be careful they didn't make this a robotics science project and instead make sure they spent more time outside the building.

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here.

Autonomow team members:

Jorge Heraud (MS Management, 2011) Business Unit Director, Agriculture, Trimble Navigation, Director of Engineering, Trimble Navigation, MS&E (Stanford), MSEE (Stanford), BSEE (PUCP, Peru)

Lee Redden (MSME Robotics, Jun 2011) Research in haptic devices, autonomous systems and surgical robots, BSME (U Nebraska at Lincoln), Family Farms in Nebraska

Joe Bingold (MBA, Jun 2011) Head of Product Development for Naval Nuclear Propulsion Plant Control Systems, US Navy, MSME (Naval PGS), BSEE (MIT), P.E. in Control Systems

Fred Ford (MSME, Mar 2011) Senior Eng for Mechanical Systems on Military Satellites, BS Aerospace Eng (U of Michigan)

Uwe Vogt (MBA, Jun 2011) Technical Director & Co-Owner, Sideo Germany (Sub. Vogt Holding), PhD Mechanical Engineering (FAU, Germany), MS Engineering (ETH Zurich, Switzerland

The mentors who volunteered to help this team were Sven Strohbad, Ravi Belani and George Zachary.

Personal Libraries

Our next team up was Personal Libraries which proposed to help researchers manage, share and reference the thousands of papers in their personal libraries. "We increase a researcher's productivity with a personal reference management system that eliminates tedious tasks associated with discovering, organizing and citing their industry readings," wrote the team. What was unique about this team was that Xu Cui, a Stanford postdoc in Neuroscience, had built the product to use for his own research. By the time he joined the class, the product was being used in over a hundred research organizations including Stanford, Harvard, Pfizer, the National Institute of Health and Peking University. The problem is that the product was free for end users and few Research institutions purchased site licenses. The goal was to figure out whether this product could become a company.

The Personal Libraries core hypotheses were:

We solve enough pain for researchers to drive purchase

Dollar size of deals is sufficient to be profitable with direct sales strategy

The market is large enough for a scalable business

Our feedback was that "free" and "researchers in universities" was often the null set for a profitable business.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Personal Libraries Team Members

Abhishek Bhattacharyya (MSEE, Jun 2011) creator of WT-Ecommerce, an open source engine, Ex-NEC engineer

Xu Cui (Ph.D, Jun 2007 Baylor) Stanford Researcher Neuroscience, postdoc, BS biology from Peking University

Mike Dorsey (MBA/MSE, Jun 2011) B.S. in computer science, environmental engineering and middle east studies from Stanford, Austin College and the American University in Cairo

Becky Nixon (MSE, Jun 2011) BA mathematics and psychology Tulane University Ex-Director, Scion Group,

Ian Tien (MBA, Jun 2011) MS in Computer Science from Cornell, Microsoft Office Engineering Manager for SharePoint, and former product manager for SkyDrive

The mentors who volunteered to help this team were Konstantin Guericke and Bryan Stolle.

The Week 2 Lecture: Value Proposition

Our working thesis was not one we shared with the class – we proposed to teach entrepreneurship the way you would teach artists – deep theory coupled with immersive hands-on experience.

Our lecture this week covered Value Proposition – what problem will the customer pay you to solve? What is the product and service you were offering the customer to solve that problem.

If you can't see the slide above, click here.

Feeling Good

Seven other teams presented after the first two (we'll highlight a few more of them in the next posts.) About half way through the teaching team started looking at each other all with the same expression – we may be on to something here.

———

Next week each team tests their value proposition hypotheses (their product/service) and reports the results of face-to-face customer discovery. Stay tuned

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

March 14, 2011

The Lean LaunchPad Class at Stanford: Class 2- Business Model and Customer Discovery Hypotheses

Our new Stanford Lean LaunchPad class was an experiment in teaching a new model of startup entrepreneurship. This post is part two.

By now the nine teams at our Stanford Lean LaunchPad Class were formed, and in the four days between the team formation and this class session we tasked them to:

Write down the hypotheses for the 9 parts of their company's business model.

Come up with ways to test:

each of the 9 business model hypotheses

is their business worth pursuing (give us an estimate of market size)

Come up with what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test (e.g. at what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct)?

Start their blog/wiki/journal for the class

The Nine Teams Present

Every week every team had to present a 10 minute summary of what they did and what they learned. As each team presented the teaching team would ask questions and give suggestions (at times pointed ones) for things they missed or might want to consider next week. (These presentations counted for 30% of their grade, and graded them on a scale of 1-5, posted our grades and comments to a shared Google doc, and had our Teaching Assistant aggregate the grades and feedback to pass on to the teams.)

Our first team up was Autonomow. They were going to develop a robot lawn mower. Off to a running start, they not only wrote down their initial business model hypotheses but they immediately got out of the building and began interviewed prospective customers to test their three most critical assumptions in any business: Value Proposition, Customer Segment and Channel. Their hypotheses when they left the campus were:

Value Proposition: Labor costs in mowing and weeding applications are significant, and autonomous implementation would solve the problem.

Customer Segment: Owners/administrators of large green spaces (golf courses, universities, etc.) would buy an autonomous mower. Organic farmers would buy if the Return On Investment (ROI) is less than 1 year.

Channel: Mowing and agricultural equipment dealers

All teams were keeping a blog – almost like a diary – of what they were doing. Reading the Autonomow blog for the first week was interesting, you could see their first hypotheses already starting to shift: "For mowing applications, we talked to the Stanford Ground Maintenance, Stanford Golf Course supervisor for grass maintenance, a Toro distributor, and an early adopter of an autonomous lawn mower. For weeding applications, we spoke with both small and large farms. In order from smallest (40 acres) to largest (8000+ acres): Paloutzian Farms, Rainbow Orchards, Rincon Farms, REFCO Farms, White Farms, and Bolthouse Farms.

We got some very interesting feedback, and overall interest in both systems. Both hypotheses (mowing and weeding) passed, but with some reservations (especially from those who's jobs they would replace!) We also got good feedback from Toro with respect to another hypothesis – selling through distributor vs. selling direct to the consumer."

The Autonomow team summarized their findings in their first 10 minute, weekly Lesson Learned presentation to the class.

Autonomow team members:

Jorge Heraud (MS Management, 2011) Business Unit Director, Agriculture, Trimble Navigation, Director of Engineering, Trimble Navigation, MS&E (Stanford), MSEE (Stanford), BSEE (PUCP, Peru)

Lee Redden (MSME Robotics, Jun 2011) Research in haptic devices, autonomous systems and surgical robots, BSME (U Nebraska at Lincoln), Family Farms in Nebraska

Joe Bingold (MBA, Jun 2011) Head of Product Development for Naval Nuclear Propulsion Plant Control Systems, US Navy, MSME (Naval PGS), BSEE (MIT), P.E. in Control Systems

Fred Ford (MSME, Mar 2011) Senior Eng for Mechanical Systems on Military Satellites, BS Aerospace Eng (U of Michigan)

Uwe Vogt (MBA, Jun 2011) Technical Director & Co-Owner, Sideo Germany (Sub. Vogt Holding), PhD Mechanical Engineering (FAU, Germany), MS Engineering (ETH Zurich, Switzerland

Personal Libraries

Our next team up was Personal Libraries. They wanted to help researchers manage, share and reference the thousands of papers in their personal libraries. We increase a researcher's productivity with a personal reference management system that eliminates tedious tasks associated with discovering, organizing and citing their industry readings. What was unique about this team was that Xu Cui a Stanford postdo in Neuroscience had built the product to use for his own research. By the time he joined the class it was being used in over a hundred research organizations including Stanford, Harvard, Pfizer, the National Institute of Health and Peking University. The problem is that the product is free to use for end users and few Research institutions purchased site licenses. The goal was to figure out whether this product could become a company.

The Personal Libraries core hypotheses are:

We solve enough pain for researchers to drive purchase

Dollar size of deals sufficient to be profitable with direct sales strategy

The market large enough for a scalable business

Personal Libraries Team Members

Abhishek Bhattacharyya, creator of WT-Ecommerce, an open source engine, Ex-NEC engineer, Masters EE candidate

Xu Cui Stanford Researcher Neuroscience, postdoc, PhD in Neuroscience from Baylor College of Medicine and a degree in biology from Peking University

Mike Dorsey B.S. in computer science, environmental engineering and middle east studies from Stanford, Austin College and the American University in Cairo MS/MBA candidate

Becky Nixon BA mathematics and psychology Tulane University Ex-Director, Scion Group, Stanford MS&E candidate

Ian Tien . MS in Computer Science from Cornell, Microsoft Office Engineering Manager for SharePoint, and former product manager for SkyDrive , Stanford MBA/MPP candidate

Teaching Team Week 2 Lecture: Value Proposition

Our working thesis was not one we shared with the class – we proposed to teach entrepreneurship like you would teach artists – deep theory plus immersive hands-on.

Our lecture this week covered Value Proposition – what problem is the customer going to pay you to solve? What product and service you were offering the customer to solve that problem.

———

Deliverable for Jan 18th:

Find a name for your team.

What were your value proposition hypotheses?

What did you discover from customers?

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Update your blog/wiki/journal

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

March 8, 2011

A New Way to Teach Entrepreneurship – The Lean LaunchPad at Stanford: Class 1

For the past three months, we've run an experiment in teaching entrepreneurship.

In January, we introduced a new graduate course at Stanford called the Lean LaunchPad. It was designed to bring together many of the new approaches to building a successful startup – customer development, agile development, business model generation and pivots.

We thought it would be interesting to share the week-by-week progress of how the class actually turned out. This post is part one.

A New Way to Teach Entrepreneurship

As the students filed into the classroom, my entrepreneurial reality distortion field began to weaken. What if I was wrong? Could we even could find 40 Stanford graduate students interested in being guinea pigs for this new class? Would anyone even show up? Even if they did, what if the assumption – that we had developed a better approach to teaching entrepreneurship – was simply mistaken?

We were positing that 20 years of teaching "how to write a business plan" might be obsolete. Startups, are not about executing a plan where the product, customers, channel are known. Startups are in fact only temporary organizations, organized to search–not execute–for a scalable and repeatable business model.

We were going to toss teaching the business plan aside and try to teach engineering students a completely new approach to start companies – one which combines customer development, agile development, business models and pivots. (The slides below and the syllabus here describe the details of the class.)

Get Out of the Building and test the Business Model

While we were going to teach theory and frameworks, these students were going to get a hands-on experience in how to start a new company. Over the quarter, teams of students would put the theory to work, using these tools to get out of the building and talk to customer/partners, etc. to get hard-earned information. (The purpose of getting out of the building is not to verify a financial model but to hypothesize and verify the entire business model. It's a subtle shift but a big idea with tremendous changes in the end result.)

Team Autonomow: Weeding Robot Prototype on a Farm

We were going to teach entrepreneurship like you teach artists – combining theory – with intensive hands-on practice. And we were assuming that this approach would work for any type of startup – hardware, medical devices, etc. – not just web-based startups.

If we were right, we'd see the results in their final presentations – after 8 weeks of class the information/learning density in the those presentations should be really high. In fact they would be dramatically different than any other teaching method.

But we could be wrong.

While I had managed to persuade two great VC's to teach the class with me (Jon Feiber and Ann Miura-ko), what if I was wasting their time? And worse, what if I was going to squander the time of my students?

I put on my best game face and watched the seats fill up in the classroom.

Mentors

A few weeks before the Stanford class began, the teaching team went through their Rolodexes and invited entrepreneurs and VCs to volunteer as coaches/mentors for the class's teams. (Privately I feared we might have more mentors than students.) An hour before this first class, we gathered these 30 impressive mentors to brief them and answer questions they might have after reading the mentor guide which outlined the course goals and mentor responsibilities.

As the official start time of the first class drew near, I began to wonder if we had the wrong classroom. The room had filled up with close to a 100 students who wanted to get in. When I realized they were all for our class, I could start to relax. OK, somehow we got them interested. Lets see if we can keep them. And better, lets see if we can teach them something new.

The First Class

The Lean LaunchPad class was scheduled to meet for three hours once a week. Given Stanford's 10 week quarters, we planned for eight weeks of lecture and the last two weeks for team final presentations. Our time in class would be relatively straightforward. Every week, each team would give a 10-minute presentation summarizing the "lessons learned" from getting out of the building. When all the teams were finished the teaching team lectured on one of the 9 parts of the business model diagram. The first class was an introduction to the concepts of business model design and customer development.

http://www.slideshare.net/sblank/stan...

The most interesting part of the class would happen outside the classroom when each team spent 50-80 hours a week testing their business model hypotheses by talking to customers and partners and (in the case of web-based businesses) building their product.

Selection, Mixer and Speed Dating

After the first class, our teaching team met over pizza and read each of the 100 or so student applications. Two-thirds of the interested students were from the engineering school; the other third were from the business school. And the engineers were not just computer science majors, but in electrical, mechanical, aerospace, environmental, civil and chemical engineering. Some came to the class with an idea for a startup burning brightly in their heads. Some of those applied as teams. Others came as individuals, most with no specific idea at all.

We wanted to make sure that every student who took the class had at a minimum declared a passion and commitment to startups. (We'll see later that saying it isn't the same as doing it.) We tried to weed out those that were unsure why they were there as well as those trying to build yet another fad of the week web site. We made clear that this class wasn't an incubator. Our goal was to provide students with a methodology and set of tools that would last a lifetime – not to fund their first round. That night we posted the list of the students who were accepted into the class.

The next day, the teaching team held a mandatory "speed-dating" event with the newly formed teams. Each team gave each professor a three-minute elevator pitch for their idea, and we let them know if it was good enough for the class. A few we thought were non-starters were sold by teams passionate enough to convince us to let them go forward with their ideas. (The irony is that one of the key tenets of this class is that startups end up as profitable companies only after they learn, discover, iterate and Pivot past their initial idea.) I enjoyed hearing the religious zeal of some of these early pitches.

The Teams

By the beginning of second session the students had become nine teams with an amazing array of business ideas. Here is a brief summary of each.

Agora isan affordable "one-stop shop" for cloud computing needs. Intended for cloud infrastructure service providers, enterprises with spare capacity in their private clouds, startups, companies doing image and video processing, and others. Agora's selling points are its ability to reduce users' IT infrastructure cost and enhance revenue for service providers.

Autonomow is an autonomous large-scale mowing intended to be a money-saving tool for use on athletic fields, golf courses, municipal parks, and along highways and waterways. The product would leverage GPS and laser-based technologies and could be used on existing mower or farm equipment or built into new units.

BlinkTraffic will empower mobile users in developing markets (Jakarta, Sao Paolo, Delhi, etc.) to make informed travel decisions by providing them with real-time traffic conditions. By aggregating user-generated speed and location data, Blink will provide instantaneously generated traffic-enabled maps, optimal routing, estimated time-to-arrival and predictive itinerary services to personal and corporate users.

D.C. Veritas is making a low cost, residential wind turbine. The goal is to sell a renewable source of energy at an affordable price for backyard installation. The key assumptions are: offering not just a product, but a complete service (installation, rebates, and financing when necessary,) reduce the manufacturing cost of current wind turbines, provide home owners with a cool and sustainable symbol (achieving "Prius" status.)

JointBuy is an online platform that allows buyers to purchase products or services at a cheaper price by giving sellers opportunities to sell them in bulk. Unlike Groupon which offers one product deal per day chosen based on the customer's location. JointBuy allows buyers to start a new deal on any available product and share the idea with others through existing social networking sites. It also allows sellers to place bids according to the size of the deal.

MammOptics is developing an instrument that can be used for noninvasive breast cancer screening. It uses optical spectroscopy to analyze the physiological content of cells and report back abnormalities. It will be an improvement over mammography by detecting abnormal cells in an early stage, is radiation-free, and is 2-5 times less expensive than mammographs. We will sell the product directly to hospitals and private doctors.

Personal Libraries is a personal reference management system streamlinig the processes for discovering, organizing and citing researchers' industry readings. The idea came from seeing the difficulty biomed researchers have had in citing the materials used in experiments. The Personal Libraries business model is built on the belief that researchers are overloaded with wasted energy and inefficiency and would welcome a product that eliminates the tedious tasks associated with their work.

PowerBlocks makes a line of modular lighting. Imagine a floor lamp split into a few components (the base, a mid-section, the top light piece). What would you do if wanted to make that lamp taller or shorter? Or change the top light from a torch-style to an LED-lamp? Or add a power plug in the middle? Or a USB port? Or a speaker? "PowerBlocks" modular lighting is "floor-lamp meets Legos" but much more high-end. Customers can choose components to create the exact product that fit their needs.

Voci.us is an ad-supported, web-based comment platform for daily news content. Real-time conversations and dynamic curation of news stories empowers people to expand their social networks and personal expertise about topics important to them. This addresses three problems vexing the news industry: inadequate online community engagement, poor topical search capacity on news sites, and scarcity of targeted online advertising niches.

While I was happy with how the class began, the million dollar question was still on the table – is teaching entrepreneurship with business model design and customer development better than having the students write business plans? Would we have to wait 8 more weeks until their final presentation to tell? Would we signs of success early? Or was the business model/customer development framework just smoke, mirror and B.S.?

The Adventure Begins

We're going to follow the adventures of a few of the teams week by week as they progressed through the class, (and we'll share the teams weekly "lessons learned," as well as our class lecture slides.

The goal for the teams for next week were:

Write down their hypotheses for each of the 9 parts of the business model.

Come up with ways to test:

what are each of the 9 business model hypotheses?

is their business worth pursuing (market size)

Come up with what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test (e.g. at what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct)?

Start their blog/wiki/journal for the class

Next Post: The Business Model and Customer Discovery Hypotheses – Class 2

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

March 2, 2011

Honor and Recognition in Event of Success

"Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success."

Attributed to Ernest Shackleton

In 1912 Ernest Shackleton placed this ad to recruit a crew for the ship Endurance and his expedition to the South Pole. This would be one of the most heroic journeys of exploration ever undertaken. In it Shackleton defined courage and leadership.

Over the last year I've been lucky enough to watch the corporate equivalent at a major U.S. corporation – starting a new technology division bringing disruptive technology to market at General Electric.

One of GE's new divisions – GE's Energy Storage – has been given the charter to bring an entirely new battery technology to market. This battery works equally well whether it's below freezing or broiling hot. It's high density, long life, environmentally friendly and can go places other batteries can't.

This is a new division of a large, old company where one would think innovation had long been beaten out of them. You couldn't be more wrong. The Energy Storage division is acting like a startup, and Prescott Logan its General Manager, has lived up to the charter. He's as good as any startup CEO in Silicon Valley. Working with him, I've been impressed to watch his small team embrace Customer Development (and Business Model Generation) and search the world for the right product/market fit. They've tested their hypotheses with literally hundreds of customer interviews on every continent in the world. They've gained as good of an insight into customer needs and product feature set than any startup I've seen. And they've continuously iterated and gone through a few pivots of their business model. (Their current initial markets for their batteries include telecom, utilities, transportation and Uninterrupted Power Supply (UPS) markets.) And they've being doing this while driving product cost down and performance up.

GE's performance in implementing Customer Development gives lie to the tale that only web startups can be agile. Corporate elephants can dance.

So why this post?

GE's Energy Storage division is looking to hire two insanely great people who can act like senior execs in a startup:

A leader of Customer Development — think of it as a Product Manger running a product line who knows how to get out of the building and not write MRD's but listen to customers.

A Sales Closer – a salesman who can make up the sales process on the fly and bring in deals without a datasheet, price list or roadmap. They will build the sales team that follows.

If you've been intrigued by the notion of customer development in an early stage startup —getting out of the building to talk to customers and working with an engineering team that's capable of being agile and responsive – yet backed by a $150 billion corporation, this is the opportunity of a lifetime. (The good news/bad news is that you'll spend ½ your time on airplanes listening to customers.)

If you have 10 years of product management or sales experience, and think that you have extraordinary talent to match the opportunity, submit your resume by: 1) Clicking on Customer Development or Sales Closer, and 2) Emailing your resume to Prescott Logan at prescott.logan@ge.com Tell him you want to sign up for the adventure.

Honor and recognition in event of success.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Technology

February 22, 2011

A Visitors Guide to Silicon Valley

If you're a visiting dignitary whose country has a Gross National Product equal to or greater than the State of California, your visit to Silicon Valley consists of a lunch/dinner with some combination of the founders of Google, Facebook, Apple and Twitter and several brand name venture capitalists. If you have time, the President of Stanford will throw in a tour, and then you can drive by Intel or some Clean Tech firm for a photo op standing in front of an impressive looking piece of equipment.

The "official dignitary" tour of Silicon Valley is like taking the jungle cruise at Disneyland and saying you've been to Africa. Because you and your entourage don't know the difference between large innovative companies who once were startups (Google, Facebook, et al) and a real startup, you never really get to see what makes the valley tick.

If you didn't come in your own 747, here's a guide to what to see in the valley (which for the sake of this post, extends from Santa Clara to San Francisco.) This post offers things to see/do for two types of visitors: I'm just visiting and want a "tourist experience" (i.e. a drive by the Facebook / Google / Zynga / Apple building) or "I want to work in the valley" visitor who wants to understand what's going on inside those buildings.

I'm leaving out all the traditional stops that you can get from the guidebooks.

Hackers' Guide to Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is more of a state of mind than a physical location. It has no large monuments, magnificent buildings or ancient heritage. There are no tours of companies or venture capital firms. From Santa Clara to South San Francisco it's 45 miles of one bedroom community after another. Yet what's been occurring for the last 50 years within this tight cluster of suburban towns is nothing short of an "entrepreneurial explosion" on par with classic Athens, renaissance Florence or 1920's Paris.

California Dreaming

On your flight out, read Paul Graham's essays and Jessica Livingston's Founders at Work. Then watch the Secret History of Silicon Valley and learn what the natives don't know.

Palo Alto – The Beating Heart 1

Start your tour in Palo Alto. Stand on the corner of Emerson and Channing Street in front of the plaque where the triode vacuum tube was developed. Walk to 367 Addison Avenue, and take a look at the HP Garage. Extra credit if you can explain the significance of both of these spots and why the HP PR machine won the rewrite of Valley history.

Walk to downtown Palo Alto at lunchtime, and see the excited engineers ranting to one another on their way to lunch. Cram into Coupa Café full of startup founders going through team formation and fundraising discussions. (Noise and cramped quarters basically force you to listen in on conversations) or University Café or the Peninsula Creamery to see engineers working on a startup or have breakfast in Il Fornaio to see the VC's/Recruiters at work.

Stanford – The Brains

Drive down University Avenue into Stanford University as it turns into Palm Drive. Park on the circle and take a walking tour of the campus and then head to the science and engineering quad. Notice the names of the buildings; Gates, Allen, Moore, Varian, Hewlett, Packard, Clark, Plattner, Yang, Huang, etc. Extra points if you know who they all are and how they started their companies. You too can name a building after your IPO (and $30 million.) Walk by the Terman Engineering building to stand next to ground zero of technology entrepreneurship. See if you can find a class being taught by Tom Byers, Kathy Eisenhardt, Tina Seelig or one of the other entrepreneurship faculty in engineering.

Attend one of the free Entrepreneurial Thought Leader Lectures in the Engineering School. Check the Stanford Entrepreneurship Network calendar or the BASES calendar for free events. Stop by the Stanford Student Startup Lab and check out the events at the Computer Forum. If you have time, head to the back of campus and hike up to the Stanford Dish and thank the CIA for its funding.

Mountain View – The Beating Heart 2

Head to Mountain View and drive down Amphitheater Parkway behind Google, admiring all the buildings and realize that they were built by an extinct company, Silicon Graphics, once one of the hottest companies in the valley (Shelley's poem Ozymandias should be the ode to the cycle of creative destruction in the valley.) Next stop down the block is the Computer History Museum. Small but important, this museum is the real deal with almost every artifact of the computing and pre-computing age (make sure you check out their events calendar.) On leaving you're close enough to Moffett Field to take a Zeppelin ride over the valley. If it's a clear day and you have the money after a liquidity event, it's a mind-blowing trip.

Next to Moffett Field is Lockheed Missiles and Space, the center of the dark side of the Valley. Lockheed came to the valley in 1956 and grew from 0 to 20,000 engineers in four years. They built three generations of submarine launched ballistic missiles and spy satellites for the CIA, NSA and NRO on assembly lines in Sunnyvale and Palo Alto. They don't give tours.

While in Mountain View drive by the site of Shockley Semiconductor and realize that from this one failed company, founded the same year Lockheed set up shop, came every other chip company in Silicon Valley.

Lunch time on Castro Street in downtown Mountain View is another slice of startup Silicon Valley. Hang out at the Red Rock Café at night to watch the coders at work trying to stay caffeinated. If you're still into museums and semiconductors, drive down to Santa Clara and visit the Intel Museum.

Sand Hill Road – Adventure Capital

While we celebrate Silicon Valley as a center of technology innovation, that's only half of the story. Startups and innovation have exploded here because of the rise of venture capital. Think of VC's as the other equally crazy half of the startup ecosystem.

You can see VC's at work over breakfast at Bucks in Woodside, listen to them complain about deals over lunch at Village Pub or see them rattle their silverware at Madera. Or you can eat in the heart of old "VC central" in the Sundeck at 3000 Sand Hill Road. While you're there, walk around 3000 Sand Hill looking at all the names of the VC's on the building directories and be disappointed how incredibly boring the outside of these buildings look. (Some VC's have left the Sand Hill Road womb and have opened offices in downtown Palo Alto and San Francisco to be closer to the action.) For extra credit, stand outside one of the 3000 Sand Hill Road buildings wearing a sandwich-board saying "Will work for equity" and hand out copies of your executive summary and PowerPoint presentations.

Drive by the Palo Alto house where Facebook started (yes, just like the movie) and the house in Menlo Park that was Google's first home. Drive down to Cupertino and circle Apple's campus. No tours but they do have an Apple company store which doesn't sell computers but is the only Apple store that sells logo'd T-shirts and hats.

San Francisco – Startups with a Lifestyle

Drive an hour up to San Francisco and park next to South Park in the South of Market area. South of Market (SoMa) is the home address and the epicenter of Web 2.0 startups. If you're single, living in San Francisco and walking/biking to work to your startup definitely has some advantages/tradeoffs over the rest of the valley. Café Centro is South Park's version of Coupa Café. Or eat at the American Grilled Cheese Kitchen. (You're just a few blocks from the S.F. Giants ballpark. If it's baseball season take in a game in a beautiful stadium on the bay.) And four blocks north is Moscone Center, the main San Francisco convention center. Go to a trade show even if it's not in your industry.

The Valley is about the Interactions Not the Buildings

Like the great centers of innovation, Silicon Valley is about the people and their interactions. It's something you really can't get a feel of from inside your car or even walking down the street. You need to get inside of those building and deeper inside those conversations. Here's a few suggestions of how to do so.

If you want the ultimate startup experience, see if you can talk yourself into carrying someone's bags as they give a pitch to a VC. Be a fly on the wall and soak it in.

If you're trying to get a real feel of the culture, apply and interview for jobs in three Silicon Valley companies even if you don't want any of them. The interview will teach your more about Silicon Valley company culture and the valley than any tour.

Go to at least three tech-oriented Meetup s or Plancast events in the Valley or San Francisco (Meetup is a deep list. Search for "startup" meetup's in San Francisco, Palo Alto and Santa Clara.)

Check out the meetups from iOS Developers, Hackers and Founders, 106Miles and Ideakick. Catch a monthly hackathon. Subscribe to StartupDigest Silicon Valley edition before you visit.

Find a real 3-10 person startup, working from a small crammed co-working space and sit with them for an afternoon. Offer to code for free. San Francisco has many co-working spaces (shared offices for startups). They're great to get a feel of what it's like to start when there's just a few founders and you don't have your own garage.Visit Founders Den, Sandbox Suites, Citizenspace, pariSoma Innovation, the Hub, NextSpace, RocketSpace, and DogPatch Labs. Driving down the valley see Studio G in Redwood City, Hacker Dojo in Mountain View, the Plug & Play Tech Center in Sunnyvale, Semantic Seed in San Jose.

Get invited to an event at Blackbox.vc and the Sandbox Network. See if there's a Startup Weekend or SVASE event going on in the Bay Area.

If you're visiting to raise money or to get to know "angels" use AngelList to get connected to seed investors before you arrive.

Use your entrepreneurial skill and get yourself into a Y-Combinator dinner or demo day, a 500 Startups or Harrsion Metal event. Go to a Techcrunch event. And of course go to a Lean Startup Meetup.

Talk yourself into a job.

Never leave.

Filed under: Family/Career, Technology, Venture Capital

February 15, 2011

College and Business Will Never Be the Same

Education is what remains after one has forgotten everything he learned in school

Attributed to Albert Einstein, Mark Twain and B.F. Skinner

There are 4633 accredited, degree-granting colleges and universities in the United States. This weekend I had dinner last night with one of them – a friend who's now the President of Philadelphia University. He's working hard to reinvent the school into a model for 21st century Professional education.

The Silo Career Track

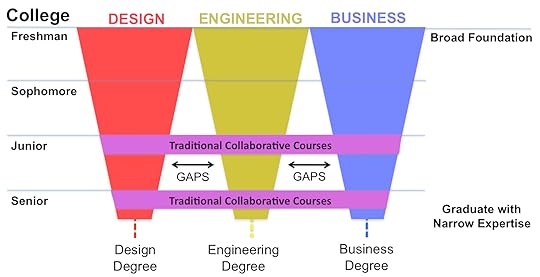

One of the problems in business today is that college graduates trained in a single professional discipline (i.e. design, engineering or business) end up graduating as domain experts but with little experience working across multiple disciplines.

In the business world of the of the 20th century it was assumed that upon graduation students would get jobs and focus the first years of their professional careers working on specific tasks related to their college degree specialty. It wasn't until the middle of their careers that they find themselves having to work across disciplines (engineers, working with designers and product managers and vice versa) to collaborate and manage multiple groups outside their trained expertise.

This type of education made sense in design, engineering and business professions when graduates could be assured that the businesses they were joining offered stable careers that gave them a decade to get cross discipline expertise.

20th Century Professional Education

Today, college graduates with a traditional 20th century College and University curriculum start with a broad foundation but very quickly narrow into a set of specific electives focused on a narrow domain expertise.

Interdisciplinary and collaborative courses are offered as electives but don't really close the gaps between design, engineering and business.

Interdisciplinary Education in a Volatile, Complex, and Ambiguous World

The business world is now a different place. Graduating students today are entering a world with little certainty or security. Many will get jobs that did not exist when they started college. Many more will find their jobs obsolete or shipped overseas by the middle of their career.

This means that students need skills that allow them to be agile, resilient, and cross functional. They need to view their careers knowing that new fields may emerge and others might disappear. Today most college curriculum are simply unaligned with modern business needs.

Over a decade ago many research universities and colleges recognized this problem and embarked on interdisciplinary education to break down the traditional barriers between departments and specialties. (At Stanford, the D-School offers graduate students in engineering, medicine, business, humanities, and education an interdisciplinary way to learn design thinking and work together to solve big problems.) This isn't as easy as it sounds as some of the traditional disciplines date back centuries (with tenure, hierarchy and tradition just as old.)

Philadelphia University Integrates Design, Engineering and Commerce

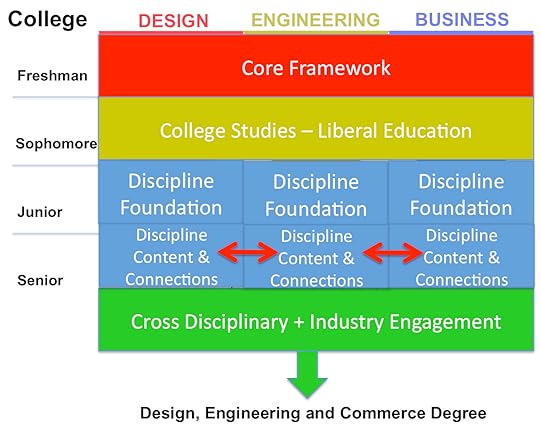

At dinner, I got to hear about how Philadelphia University was tackling this problem in undergraduate education. The University, with 2600 undergrads and 500 graduate students, started out in 1884 as the center of formal education for America's textile workers and managers. The 21st century version of the school just announced its new Composite Institute for industrial applications.

(Full disclosure, Philadelphia University's current president, Stephen Spinelli was one of my mentors in learning how to teach entrepreneurship. At Babson College he was chair of the entrepreneurship department and built the school into one of the most innovative entrepreneurial programs in the U.S.)

Philadelphia University's new degree program, Design, Engineering and Commerce (DEC) will roll out this Fall. It starts with a core set of classes that all students take together; systems thinking, user-centric design, business models and team dynamics. These classes start the students thinking early about customers, value, consumer insights, and then move to systems thinking with an emphasis on financial, social, and political sustainability. They also get a healthy dose of liberal arts education and then move on to foundation classes in their specific discipline. But soon after that Philadelphia University's students move into real world projects outside the university. The entire curriculum has heavy emphasis on experiential learning and interdisciplinary teams.

The intent of the DEC program is not just teaching students to collaborate, it also teaches them about agility and adaptation. While students graduate with skills that allow them to join a company already knowing how to coordinate with other functions, they carry with them the knowledge of how to adapt to new fields that emerge long after they graduate.

This type of curriculum integration is possible at Philadelphia because they have:

1) a diverse set of 18 majors, 2) three areas of focus; design, engineering, and business and 3) a manageable scale (~2,600 students.)

I think this school may be pioneering one of the new models of undergraduate professional education. One designed to educate students adept at multidisciplinary problem solving, innovation and agility.

College and business will never be the same.

Lessons Learned

Most colleges and Universities are still teaching in narrow silos

It's hard to reconfigure academic programs

It's necessary to reconfigure professional programs to match the workplace

Innovation needs to be applied to how we teach innovation

Filed under: Teaching, Technology

February 8, 2011

Startup America – Dead On Arrival

For its first few decades Silicon Valley was content flying under the radar of Washington politics. It wasn't until Fairchild and Intel were almost bankrupted by Japanese semiconductor manufacturers in the early 1980's that they formed Silicon Valley's first lobbying group. Microsoft did not open a Washington office until 1995.

Fast forward to today. The words "startup," "entrepreneur," and "innovation" are used fast, loose and furious by both parties in Washington. Last week the White House announced Startup America, a public/private initiative to accelerate accelerate high-growth entrepreneurship in the U.S. by expanding startups access to capital (with two $1 billion programs); creating a national network of entrepreneurship education, commercializing federally-funded research and development programs and getting rid of tax and paperwork barriers for startups.

What's not to like?

My observation. Startup America is a mashup of very smart programs by very smart people but not a strategy. It made for a great photo op, press announcement and impassioned speeches. (Heck, who wouldn't go to the White House if the President called.) It engaged the best and the brightest who all bring enormous energy and talent to offer the country. The technorati were effusive in their praise.

I hope it succeeds. But I predict despite all of Washingtons' good intentions, it's dead on arrival.

Dead On Arrival

I got a call from a recruiter looking for a CEO for the Startup America Partnership. Looking at the job spec reminded me what it would be like to lead the official rules committee for the Union of Anarchists.

There are three problems. First, an entrepreneurship initiative needs to be an integral part of both a coherent economic policy and a national innovation policy – one that creates jobs for Main Street versus Wall Street. It should address not only the creation of new jobs, but also the continued hemorrhaging of jobs and entire strategic industries offshore.

Second, trying to create Startup America without understanding and articulating the distinctions among the four types of entrepreneurship (described later) means we have no roadmap of where to place the bets on job growth, innovation, legislation and incentives.

Third, the notion of a public/private partnership without giving entrepreneurs a seat at the policy table inside the White House is like telling the passengers they can fly the plane from their seats. It has zero authority, budget or influence. It's the national cheerleader for startups.

The Four Types of Entrepreneurship

"Startup," "entrepreneur," and "innovation" now means everything to everyone. Which means in the end they mean nothing. There doesn't seem to be a coherent policy distinction between small business startups, scalable startups, corporations dealing with disruptive innovation and social entrepreneurs. The words "startup," "entrepreneur," and "innovation" mean different things in Silicon Valley, Main Street, Corporate America and Non Profits. Unless the people who actually make policy (rather than the great people who advise them) understand the difference, and can communicate them clearly, the chance of any of the Startup America policies having a substantive effect on innovation, jobs or the gross domestic product is low.

1. Small Business Entrepreneurship

Today, the overwhelming number of entrepreneurs and startups in the United States are still small businesses. There are 5.7 million small businesses in the U.S. They make up 99.7% of all companies and employ 50% of all non-governmental workers.

Small businesses are grocery stores, hairdressers, consultants, travel agents, internet commerce storefronts, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, etc. They are anyone who runs his/her own business. They hire local employees or family. Most are barely profitable. Their definition of success is to feed the family and make a profit, not to take over an industry or build a $100 million business. As they can't provide the scale to attract venture capital, they fund their businesses via friends/family or small business loans.

2. Scalable Startup Entrepreneurship

Unlike small businesses, scalable startups are what Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and their venture investors do. These entrepreneurs start a company knowing from day one that their vision could change the world. They attract investment from equally crazy financial investors – venture capitalists. They hire the best and the brightest. Their job is to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. When they find it, their focus on scale requires even more venture capital to fuel rapid expansion.

Scalable startups in innovation clusters (Silicon Valley, Shanghai, New York, Bangalore, Israel, etc.) make up a small percentage of entrepreneurs and startups but because of the outsize returns, attract almost all the risk capital (and press.) Startup America was focussed on this segment of startups.

3. Large Company Entrepreneurship

3. Large Company Entrepreneurship

Large companies have finite life cycles. Most grow through sustaining innovation, offering new products that are variants around their core products. Changes in customer tastes, new technologies, legislation, new competitors, etc. can create pressure for more disruptive innovation – requiring large companies to create entirely new products sold into new customers in new markets. Existing companies do this by either acquiring innovative companies or attempting to build a disruptive product inside. Ironically, large company size and culture make disruptive innovation extremely difficult to execute.

4. Social Entrepreneurship

4. Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurs are innovators focus on creating products and services that solve social needs and problems. But unlike scalable startups their goal is to make the world a better place, not to take market share or to create to wealth for the founders. They may be nonprofit, for-profit, or hybrid.

So What?

Each of these four very different business segments require very different educational tools, economic incentives (tax breaks, paperwork/regulation reduction, incentives), etc. Yet as different as they are, understanding them together is what makes the difference between a jobs and innovation strategy and a disconnected set of tactics.

Go take a look at any of the government organizations talking about entrepreneurship and see how many of its leaders or staff actually started a company or a venture firm. Or had to make a payroll with no money in the bank. We're trying to kick-start a national initiative on startups, entrepreneurs and innovation with academics, economists and large company executives. Great for policy papers, but probably not optimal for making change.

Rather than having our best and the brightest visit for a day, what we need sitting in the White House (and on both sides of the aisle in Congress) are people who actually have started, built and grown companies and/or venture firms. (If we're serious about this stuff we should have some headcount equivalence to the influence bankers have.)

Next time the talent shows up for a Startup America initiative, they ought to be getting offices not sound bites.

Lessons Learned

Lots of credit in trying to "talk-the-talk" of startups

No evidence that Washington yet understands the types of entrepreneurs and startups; how they differ, and how they can form a cohesive and integrated jobs and innovation strategy

Not much will happen until entrepreneurs and VC's have a seat at the table

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers