Steve Blank's Blog, page 56

December 15, 2010

Hubris, Passion and Customer Development

While I was teaching at Columbia in New York in November I was interviewed for the Shoshin Project by my friend Christian Jorg.

Filed under: Customer Development

December 13, 2010

Filed under: Uncategorized

Teaching Entrepreneurship in "Chilecon Valley"

Teaching in Chile

I've spent the last week in Santiago, a guest of Professor Cristóbal García at the Catholic University of Chile as part of Stanford's Engineering Technology Venture Program.

Valaparaiso houses

Entrepreneurship and innovation in what I call "Chilecon Valley" is being talked about continually here. In my next post I'll share a longer description of my impressions. But to give you a sense of how fast they are moving, it's only been a week since I posted the syllabus for our new Stanford entrepreneurship class Engr245 (The Lean Launchpad.) This week the class has been adopted in the Computer Science department of the Catholic University of Chile. (Thanks to Professors Professor Felix Halcartegaray Vergara and Rosa Alarcon who will be teaching the class.)

Here's the course announcement from Professor Vergara (in English):

Customer Development Course in Chile – Lean Launchpad

Next semester on the Department of Computer Science of the Catholic University of Chile professor Rosa Alarcón (@ruyalarcon) and I (@felixcl) will be teaching a course based on the Customer Development Model developed by Steve Blank. The objective of this course is that groups of students finish with a completed software product that has real customers and an identified market. The idea of this course started on a trip to Stanford University during March 2010, where we realized that many of the great innovations in Silicon Valley are born from Computer Science students, so we said "We should give our computer science students an opportunity to develop a company". Then we saw the great alignment between the Customer Development Model and the Agile software development methodologies so we decided to create the course IIC3515 "Workshop of Entrepreneurship with Software" that applies both models to develop real software products with customers from the startup ideas of the students.

A few weeks ago, it was great to see that professor Steve Blank was developing a very similar course in Stanford called "The Lean Launchpad" (Engr245) that combines the customer development model with agile development with the business model canvas, and therefore we convinced ourserlves that we where not so crazy with this course, or at least we are as crazy as they are. The syllabus for the Stanford course can be seen here. This course brings to life in a very interesting way the idea we had with professor Rosa Alarcón, and it starts on January 2011 so when Steve Blank was visiting Chile this week, we told him about our course, and he offered all his help and experience to help us, and so we are very grateful to him. Therefore we will leverage the experience in Stanford giving the course on January and February to have a very interesting proposal to our students on March when we start. The syllabus for our course (in Spanish) is here: Programa de curso IIC3515. In this blog post I will add more information about the development of this course when I have it. We are very excited on this project, and we think it will have an important impact on our university and our students so thank you very much Steve for making this happen.

The goal of course IIC3515 is that students get together in teams (probably of 4) and develop their business idea during the semester, developing the software that represents it. Unlike other courses on entrepreneurship, this one is NOT about developing a Business Plan (in fact, the idea is that they write little and spend the time programming and getting out of the building to talk to customers.) The students must develop their initial hypothesis of who their customers are and what is their products (using the Business Model Canvas) , and then get out to test this Hypothesis and pivot as they start knowing their customers and "getting smarter about them".

With this methodology, once they finish the course they will have very important tools to continue developing their startup, and they will also have a product that they will feel confident about that there are customers that want to buy it, unlike what usually happens when the development of the product is completed and then you go out to the market to see if any customer wants it. In this case, the customer will be considered since the first moment, and this results in a much more controlled market risk for the venture. The idea is also to have investors on the final stages of the course, and have mentors for the students that have real world experience in startups to support the students with their projects.

We look forward to your comments and suggestions! Any updates on this course in english will have the tag "Lean Launchpad course" to make it easier to search.

Here's the course announcement in Spanish

Filed under: Teaching

December 7, 2010

The Lean LaunchPad – Teaching Entrepreneurship as a Management Science

I've introduced a new class at Stanford to teach engineers, scientists and other professionals how startups really get built.

They are going to get out of the building, build a company and get orders in ten weeks.

Jon Feiber of Mohr Davidow Ventures and Ann Miura-Ko of Floodgate are co-teaching the class with me (and Alexander Osterwalder is a guest lecturer.) We have two great teaching assistants, plus we've rounded up a team of 25 mentors (VC's and entrepreneurs) to help coach the teams.

Why Teach This Class?

Business schools teach aspiring executives a variety of courses around the execution of known business models, (accounting, organizational behavior, managerial skills, marketing, operations, etc.)

In contrast, startups search for a business model. (Or more accurately, startups are a temporary organization designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.) There are few courses which teach aspiring entrepreneurs the skills (business models, customer and agile development, design thinking, etc.) to optimize this search.

Many entrepreneurship courses focus on teaching students "how to write a business plan." Others emphasize how to build a product. If you've read any of my previous posts, you know I believe that: 1) a product is just a part of a startup, but understanding customers, channel, pricing, etc. are what make it a business,

2) business plans are fine for large companies where there is an existing market, existing product and existing customers. In a startup none of these are known.

Therefore we developed a class to teach students how to think about all the parts of building a business, not just the product.

What's Different About the Class?

This Stanford class will introduce management tools for entrepreneurs. We'll build the class around the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack.

Students will start by mapping their assumptions (their business model) and then each week test these hypotheses with customers and partners outside in the field (customer development) and use an iterative and incremental development methodology (agile development) to build the product.

The goal is to get students out of the building to test each of the 9 parts of their business model, understand which of their assumptions were wrong, and figure out what they need to do fix it. Their objective is to get users, orders, customers, etc. (and if a web-based product, a minimum feature set,) all delivered in 10 weeks. Our objective is to get them using the tools that help startups to test their hypotheses and make adjustments when they learn that their original assumptions about their business are wrong. We want them to experience faulty assumptions not as a crisis, but as a learning event called a pivot —an opportunity to change the business model.

How's the Class Organized?

During the first week of class, students form teams (optimally 4 people in a team but we're flexible.) Their company can focus in any area– software, hardware, medical device or a service of any kind.

The class meets ten times, once a week for three hours. In those three hours we'll do two things. First, we''ll lecture on one of the 9 building blocks of a business model (see diagram below, taken from Business Model Generation). Secondly, each student team will present "lessons learned" from their team's experience getting out of the building learning, testing, iterating and/or pivoting their business model.

They'll share with the class answers to these questions:

What did you initially think?

So what did you do?

Then what did you learn?

What are you going to do next?

At the course's end, each team will present their entire business model and highlight what they learned, their most important pivots and conclusions.

We're going to be teaching it for the first time in January. Below is the class syllabus.

——————–

Engineering 245

This course provides real world, hands-on learning on what it's like to actually start a high-tech company. This class is not about how to write a business plan. It's not an exercise on how smart you are in a classroom, or how well you use the research library. The end result is not a PowerPoint slide deck for a VC presentation. Instead you will be getting your hands dirty talking to customers, partners, competitors, as you encounter the chaos and uncertainty of how a startup actually works. You'll work in teams learning how to turn a great idea into a great company. You'll learn how to use a business model to brainstorm each part of a company and customer development to get out of the classroom to see whether anyone other than you would want/use your product. Finally, you'll see how agile development can help you rapidly iterate your product to build something customers will use and buy. Each week will be new adventure as you test each part of your business model and then share the hard earned knowledge with the rest of the class. Working with your team you will encounter issues on how to build and work with a team and we will help you understand how to build and manage the startup team.

Besides the instructors and TA's, each team will be assigned two mentors (an experienced entrepreneur and/or VC) to provide assistance and support.

Suggested Projects: While your first instinct may be a web-based startup we suggest that you consider a subject in which you are a domain expert, such as your graduate research. In all cases, you should choose something for which you have passion, enthusiasm, and hopefully some expertise. Teams that select a web-based product will have to build the site for the class.

——————–

Pre-reading For 1st Class: Read pages 1-51 of Osterwalder's Business Model Generation.

Class 1 Jan 4th Intro/Business Model/Customer Development

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

What's a business model? What are the 9 parts of a business model? What are hypotheses? What is the Minimum Feature Set? What experiments are needed to run to test business model hypotheses? What is market size? How to determine whether a business model is worth doing?

Deliverable: Set up teams by Thursday, Jan 6 (a mixer will be hosted on Wednesday to help finalize teams). Submit your project for approval to the teaching team.

Read:

Business Model Generation, pp. 118-119, 135-145, skim examples pp. 56-117

Four Steps to the Epiphany Chapters 1-2

Steve Blank, "What's a Startup? First Principles," http://steveblank.com/2010/01/25/whats-a-startup-first-principles/

Steve Blank, "Make No Little Plans – Defining the Scalable Startup," http://steveblank.com/2010/01/04/make-no-little-plans-–-defining-the-scalable-startup/

Steve Blank, "A Startup is Not a Smaller Version of a Large Company", http://steveblank.com/2010/01/14/a-startup-is-not-a-smaller-version-of-a-large-company/

Deliverable for January 11th:

Write down hypotheses for each of the 9 parts of the business model.

Come up with ways to test:

is a business worth pursuing (market size)

each of the hypotheses

Come up with what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test (e.g. at what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct)?

Start your blog/wiki/journal

——————–

Jan 6th 5-7pm Speed Dating (Meet in Thornton 110)

Get quick feedback on your initial team business concept from the teaching team.

——————–

Class 2 Jan 11th Testing Value Proposition

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

What is your product or service? How does it differ from an idea? Why will people want it? Who's the competition and how does your customer view these competitive offerings? Where's the market? What's the minimum feature set? What's the Market Type? What was your inspiration or impetus? What assumptions drove you to this? What unique insight do you have into the market dynamics or into a technological shift that makes this a fresh opportunity?

Action:

Get out of the building and talk to 10-15 customers face-to-face

Follow-up with Survey Monkey (or similar service) to get more data

Read:

Business Model Generation, pp. 161-168 and 226-231

Four Steps to the Epiphany, pp. 30-42, 65-72 and 219-223

The Blue Ocean Strategy pages 3-22

Deliverable for Jan 18th:

Find a name for your team.

What were your value proposition hypotheses?

What did you discover from customers?

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Update your blog/wiki/journal

——————–

Class 3 Jan 18th Testing Customers/users

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

Who's the customer? User? Payer? How are they different? How can you reach them? How is a business customer different from a consumer?

Action:

Get out of the building and talk to 10-15 customers face-to-face

Follow-up with Survey Monkey (or similar service) to get more data

Read:

Business Model Generation, pp. 127-133

Four Steps to the Epiphany, pp. 43-49, 78-87 224-225, and 242-248

Giff Constable, "12 Tips for Early Customer Development Interviews," http://giffconstable.com/2010/07/12-tips-for-early-customer-development-interviews/

Deliverable for Jan 25th:

What were your hypotheses about who your users and customers were? Did you learn anything different?

Submit interview notes, present results in class. Did anything change about Value Proposition?

What are your hypotheses around customer acquisition costs? Can you articulate the direct benefits (economic or other) that are apparent?

If your customer is part of a company, who is the decision maker, how large is the budget they have authority over, what are they spending it on today, and how are they individually evaluated within that organization, and how will this buying decision be made?

What resonates with customers?

For web startups, start coding the product. Setup your Google or Amazon cloud infrastructure.

Update your blog/wiki/journal

——————–

Class 4 Jan 25th Testing Demand Creation

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

How do you create end user demand? How does it differ on the web versus other channels? Evangelism vs. existing need or category? General Marketing, Sales Funnel, etc

Action:

If you're building a web site:

Small portion of your site should be operational on the web

Actually engage in "search engine marketing" (SEM)spend $20 as a team to test customer acquisition cost

Ask your users to take action, such as signing up for a newsletter

use Google Analytics to measure the success of your campaign

change messaging on site during the week to get costs lower, team that gets lowest delta costs wins.

If you're assuming virality of your product, you will need to show viral propagation of your product and the improvement of your viral coefficient over several experiments.

If non-web,

build demand creation budget and forecast.

Get real costs from suppliers.

Read:

Four Steps to the Epiphany, pp. 52-53, 120-125 and 228-229

Dave McClure, "Startup Metrics for Pirates",

http://www.slideshare.net/dmc500hats/startup-metrics-for-pirates-seedcamp-2008-presentation

Dan Siroker, "How Obama Raised $60 Million by Running a Simple Experiment", http://blog.optimizely.com/how-obama-...

Watch: Mark Pincus, "Quick and Frequent Product Testing and Assessment", http://ecorner.stanford.edu/authorMaterialInfo.html?mid=2313

Deliverable for Feb 1st :

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Did anything change about Value Proposition or Customers/Users or Channel?

Present and explain your marketing campaign. What worked best and why?

Update your blog/wiki/journal

——————–

Class 5 Feb 1st Testing Channel

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

What's a channel? Direct channels, indirect channels, OEM. Multi-sided markets. B-to-B versus B-to-C channels and sales (business to business versus business to consumer)

Action: If you're building a web site, get the site up and running, including minimal feature.

For non-web products, get out of the building talk to 10-15 channel partners.

Read: Four Steps to the Epiphany, pp. 50-51, 91-94, 226-227, 256, 267

Deliverable for Feb 8th:

For web teams:

Get a working web site and analytics up and running. Track where your visitors are coming from (marketing campaign, search engine, etc) and how their behavior differs. What were your hypotheses about your web site results?

Submit web data or customer interview notes, present results in class.

Did anything change about Value Proposition or Customers/Users?

What is your assumed customer lifetime value? Are there any proxy companies that would suggest that this is a reasonable number?

For non-web teams:

Interview 10-15 people in your channel (salesmen, OEM's, etc.).

Did anything change about Value Proposition or Customers/Users?

What is your customer lifetime value? Channel incentives – does your product or proposition extend or replace existing revenue for the channel?

What is the "cost" of your channel, and it's efficiency vs. your selling price.

Everyone: Update your blog/wiki/journal.

What kind of initial feedback did you receive from your users?

What are the entry barriers?

——————–

Class 6 Feb 8th Testing Revenue Model

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

What's a revenue model? What types of revenue streams are there? How does it differ on the web versus other channels?

Action: What's your revenue model?

How will you package your product into various offerings if you have more than one?

How will you price the offerings?

What are the key financials metrics for your business model?

Test pricing in front of 100 customers on the web, 10-15 customers non-web.

What are the risks involved?

What are your competitors doing?

Read: John Mullins & Randy Komisar, Getting to Plan B (2009) pages 133-156

Deliverable for Feb 15th :

Assemble an income statement for the your business model. Lifetime value calculation for customers.

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Did anything change about Value Proposition or Customers/Users, Channel, Demand Creation, Revenue Model?

Update your blog/wiki/journal

——————–

Class 7 Feb 15th Testing Partners

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

Who are partners? Strategic alliances, competition, joint ventures, buyer supplier, licensees.

Action: What partners will you need?

Why do you need them and what are risks?

Why will they partner with you?

What's the cost of the partnership?

Talk to actual partners.

What are the benefits for an exclusive partnership?

Deliverable for Feb 22nd

Assemble an income statement for the your business model.

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Did anything change about Value Proposition or Customers/Users, Channel, Demand Creation?

What are the incentives and impediments for the partners?

Update your blog/wiki/journal

——————–

Class 8 Feb 22nd Testing Key Resources & Cost Structure

Class Lecture/Out of the Building Assignment:

What resources do you need to build this business? How many people? What kind? Any hardware or software you need to buy? Any IP you need to license? How much money do you need to raise? When? Why? Importance of cash flows? When do you get paid vs. when do you pay others?

Action: What's your expense model?

What are the key financials metrics for costs in your business model?

Costs vs. ramp vs. product iteration?

Access to resources. What is the best place for your business?

Where is your cash flow break-even point?

Deliverable for March 1st

Assemble a resources assumptions spreadsheet. Include people, hardware, software, prototypes, financing, etc.

When will you need these resources?

Roll up all the costs from partners, resources and activities in a spreadsheet by time.

Submit interview notes, present results in class.

Did anything change about Value Proposition or Customers/Users, Channel, Demand Creation/Partners?

Update your blog/wiki/journal

Guest: Alexander Osterwalder

For March 1st or 8th

Prepare 30 –minute Team Lessons Learned Presentation

Read:

Steve Blank, "Lessons Learned – A New Type of Venture Capital Pitch", http://steveblank.com/2009/11/12/"lessons-learned"-–-a-new-type-of-vc-pitch/

Steve Blank, "Raising Money Using Customer Development", http://steveblank.com/2009/11/05/raising-money-with-customer-development/

Business Model Generation, pp. 216-224

——————–

Class 9 March 1st Team Presentations of Lessons Learned (1st half of the class)

Deliverable: Each team will present a 30 minute "Lessons Learned" presentation about their business.

——————–

Class 10 March 8th Team Presentations of Lessons Learned (2nd half of the class)

Deliverable: Each team will present a 30 minute "Lessons Learned" presentation about their business.

——————–

March 11th 1-4pm Demo Day at VC Firm (Location TBD)

Show off your product to the public and real VC's. Set up a booth, put up posters, run demos, etc. Food and refreshments provided.

——————–

Mentor List (as of Dec 3rd 2010)

Gina Bianchini, Ning

David Camplejohn, Fliptop

Shawn Carolan, Menlo Ventures

Eric Carr, Loopt

Rowan Chapman, MDV

Jason Davies, SOS Technologies

Jonathan Ebinger, BlueRun Ventures

David Feinleib, MDV

Jim Greer, Kongregate

Konstantin Guericke, LinkedIn

Will Harvey, IMVU

Thomas Hessler, Zanox

Heiko Hubertz, BigPoint

Charles Hudson, Gaia/Virtual Goods

Maheesh Jain, Cafepress

George John, Rocket Fuel

Josh Reeves, unwrap

Karen Richardson, Silverlake Partners

Josh Schwarzapel, Cooliris

Justin Shaffer, Facebook

Jim Smith, MDV

Bryan Stolle, MDV

Steve Weinstein, Movielabs

George Zachary, Charles River Ventures

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

November 30, 2010

The VC Pitch – Confusing the Destination with the Journey

Too often we are so preoccupied with the destination, we forget the journey.

Unknown

Entrepreneurs hear that VC pitches ought to be short, 10-20 slides. What most don't know is that there is no way they can deliver a presentation that short by just "writing" the slide deck.

You Got to be Kidding

An entrepreneur I've known for a long time came by the ranch over Thanksgiving break to show me the first pass of his new startup slide deck.

My eyes were glazed by slide 9. It was over 35 slides long, with each slide feeling like it had 12 lines of 10-point type. It had a problem statement going back to the invention of the telephone, an opportunity claiming to exceed the Gross National Product and it had every possible product feature with enough left over for three other startups products.

My first reaction was, "you got to be kidding." Yet I was hearing the pitch from an experienced entrepreneur with multiple wins under his belt. He had raised money from name-brand VC's in past startups and knew what a fundable VC slide deck looked like. What was going on?

Then I remembered, every slide deck I ever wrote started out just like this.

The Slide Deck As A Brainstorming Tool

Most startups ideas are not built in an afternoon, typically they are the sum of seemingly disparate and discrete pieces of information, and a pattern recognition algorithm continuously running in a founders head.

What I was seeing was an entrepreneur using a slide deck as a way to collect his thoughts. The slides were his brainstorming tool. He was using them to think through the impact of the idea he had, and was trying on for size the potential opportunity and trying to use the slides to spec his features.

The difference between this entrepreneur and a novice was that he knew his presentation wasn't ready to show to a VC; he was using it to share his thinking with me to get more feedback on his business model.

We talked about how much of his presentation were just hypotheses (most but not all,) what hypotheses he could quickly test outside the building (assumptions about minimum feature set, pricing and customer archetypes) and how to turn some of the hypotheses into facts. I pointed him to my "Lessons Learned" slide decks that turn a standard VC pitch into something more informative. He left with both of us knowing that he was months away (and lots of customer feedback) from being ready for a VC pitch.

Advice From People Who Get Bored Easy

Most of the advice founders get about Venture Capital slide decks are from the recipients of the presentations – the VC's – letting you know how they want to see the final deck. And most of their recommendations are essentially "show us your business plan in PowerPoint." Few VC's have experienced the process a founder uses to get their idea into 10-slides. And none of them tell you how.

If you find yourself trying to shoehorn your 35-slide presentation into a "VC-ready" format, you don't know enough yet. And you won't know any more by sitting in your office surfing the web and writing more slides. Get out of the building and talk to potential users and customers. The irony is the more you know, the easier it is to make your presentation short and concise.

Lessons Learned

Long slide decks are indicative of you thinking out loud;

Get out of the building and get smarter.

The more you know (versus guess) the shorter the deck.

Most VC's are looking for the "give us the business plan in PowerPoint"

Give them a "Lessons Learned" VC presentation.

Filed under: Venture Capital

November 24, 2010

When It's Darkest Men See the Stars

When It's Darkest Men See the Stars

Ralph Waldo Emerson

This Thanksgiving it might seem that there's a lot less to be thankful for. One out of ten of Americans are out of work. The common wisdom says that the chickens have all come home to roost from a disastrous series of economic decisions including outsourcing the manufacture of America's physical goods. The United States is now a debtor nation to China and that the bill is about to come due. The pundits say the American dream is dead and this next decade will see the further decline and fall of the West and in particular of the United States.

It may be that all the doomsayers are right.

But I don't think so.

Let me offer my prediction. There's a chance that the common wisdom is very, very wrong. That the second decade of the 21st century may turn out to the West's and in particular the United States' finest hour.

I believe that we will look back at this decade as the beginning of an economic revolution as important as the scientific revolution in 16th century and the industrial revolution in 18th century. We're standing at the beginning of the entrepreneurial revolution. This doesn't mean just more technology stuff, though we'll get that. This is a revolution that will permanently reshape business as we know it and more importantly, change the quality of life across the entire planet for all who come after us.

There's Something Happening Here, What It Is Ain't Exactly Clear

The story to date is a familiar one. Over the last half a century, Silicon Valley has grown into the leading technology and innovation cluster for the United States and the world. Silicon Valley has amused us, connected (and separated us) as never before, made businesses more efficient and led to the wholesale transformation of entire industries (bookstores, video rentals, newspapers, etc.)

Wave after wave of hardware, software, biotech and cleantech products have emerged from what has become "ground zero" of entrepreneurial and startup culture. Silicon Valley emerged by the serendipitous intersection of:

Cold war research in microwaves and electronics at Stanford University,

a Stanford Dean of Engineering who encouraged startup culture over pure academic research,

Cold war military and intelligence funding driving microwave and military products for the defense industry in the 1950's,

a single Bell Labs researcher deciding to start his semiconductor company next to Stanford in the 1950's which led to

the wave of semiconductor startups in the 1960's/70's,

the emergence of venture capital as a professional industry,

the personal computer revolution in 1980's,

the rise of the Internet in the 1990's and finally

the wave of internet commerce applications in the first decade of the 21st century.

The pattern for the valley seemed to be clear. Each new wave of innovation was like punctuated equilibrium – just when you thought the wave had run its course into stasis, a sudden shift and radical change into a new family of technology emerged.

The Barriers to Entrepreneurship

While startups continued to innovate in each new wave of technology, the rate of innovation was constrained by limitations we only now can understand. Only in the last few years do we appreciate that startups in the past were constrained by:

long technology development cycles (how long it takes from idea to product),

the high cost of getting to first customers (how many dollars to build the product),

the structure of the venture capital industry (a limited number of VC firms each needing to invest millions per startups),

the expertise about how to build startups (clustered in specific regions like Silicon Valley, Boston, New York, etc.),

the failure rate of new ventures (startups had no formal rules and were a hit or miss proposition),

the slow adoption rate of new technologies by the government and large companies.

The Democratization of Entrepreneurship

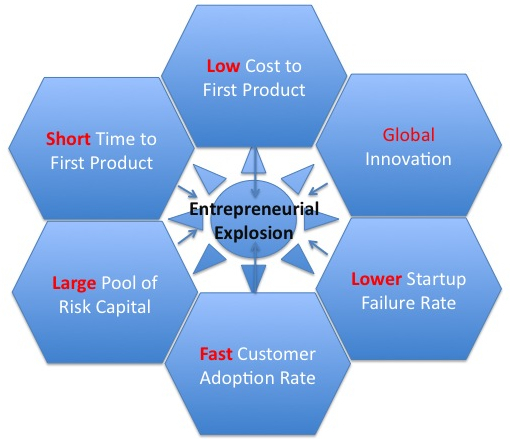

What's happening is something more profound than a change in technology. What's happening is that all the things that have been limits to startups and innovation are being removed. At once. Starting now.

Compressing the Product Development Cycle

In the past, the time to build a first product release was measured in months or even years as startups executed the founder's vision of what customers wanted. This meant building every possible feature the founding team envisioned into a monolithic "release" of the product. Yet time after time, after the product shipped, startups would find that customers didn't use or want most of the features. The founders were simply wrong about their assumptions about customer needs. The effort that went into making all those unused features was wasted.

Today startups have begun to build products differently. Instead of building the maximum number of features, they look to deliver a minimum feature set in the shortest period of time. This lets them deliver a first version of the product to customers in a fraction on the time.

For products that are simply "bits" delivered over the web, a first product can be shipped in weeks rather than years.

Startups Built For Thousands Rather than Millions of Dollars

Startups traditionally required millions of dollars of funding just to get their first product to customers. A company developing software would have to buy computers and license software from other companies and hire the staff to run and maintain it. A hardware startup had to spend money building prototypes and equipping a factory to manufacture the product.

Today open source software has slashed the cost of software development from millions of dollars to thousands. For consumer hardware, no startup has to build their own factory as the costs are absorbed by offshore manufacturers.

The cost of getting the first product out the door for an Internet commerce startup has dropped by a factor of a ten or more in the last decade.

The New Structure of the Venture Capital industry

The plummeting cost of getting a first product to market (particularly for Internet startups) has shaken up the venture capital industry. Venture capital used to be a tight club clustered around formal firms located in Silicon Valley, Boston, and New York. While those firms are still there (and getting larger), the pool of money that invests risk capital in startups has expanded, and a new class of investors has emerged. New groups of VC's, super angels, smaller than the traditional multi-hundred million dollar VC fund, can make small investments necessary to get a consumer internet startup launched. These angels make lots of early bets and double-down when early results appear. (And the results do appear years earlier then in a traditional startup.)

In addition to super angels, incubators like Y Combinator, TechStars and the 100+ plus others worldwide like them have begun to formalize seed-investing. They pay expenses in a formal 3-month program while a startup builds something impressive enough to raise money on a larger scale.

Finally, venture capital and angel investing is no longer a U.S. or Euro-centric phenomenon. Risk capital has emerged in China, India and other countries where risk taking, innovation and liquidity is encouraged, on a scale previously only seen in the U.S.

The emergence of incubators and super angels have dramatically expanded the sources of seed capital. The globalization of entrepreneurship means the worldwide pool of potential startups has increased at least ten fold since the turn of this century.

Entrepreneurship as It's Own Management Science

Over the last ten years, entrepreneurs began to understand that startups were not simply smaller versions of large companies. While companies execute business models, startups search for a business model. (Or more accurately, startups are a temporary organization designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.)

Instead of adopting the management techniques of large companies, which too often stifle innovation in a young start up, entrepreneurs began to develop their own management tools. Using the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack, entrepreneurs first map their assumptions (their business model) and then test these hypotheses with customers outside in the field (customer development) and use an iterative and incremental development methodology (agile development) to build the product. When founders discover their assumptions are wrong, as they inevitably will, the result isn't a crisis, it's a learning event called a pivot — and an opportunity to change the business model.

The result, startups now have tools that speed up the search for customers, reduce time to market and slash the cost of development.

Consumer Internet Driving Innovation

In the 1950's and '60's U.S. Defense and Intelligence organizations drove the pace of innovation in Silicon Valley by providing research and development dollars to universities, and purchased weapons systems that used the valley's first microwave and semiconductor components. In the 1970's, 80's and 90's, momentum shifted to the enterprise as large businesses supported innovation in PC's, communications hardware and enterprise software. Government and the enterprise are now followers rather than leaders. Today, it's the consumer – specifically consumer Internet companies – that are the drivers of innovation. When the product and channel are bits, adoption by 10's and 100's of millions users can happen in years versus decades.

The Entrepreneurial Singularity

The Entrepreneurial Singularity

The barriers to entrepreneurship are not just being removed. In each case they're being replaced by innovations that are speeding up each step, some by a factor of ten. For example, Internet commerce startups the time needed to get the first product to market has been cut by a factor of ten, the dollars needed to get the first product to market cut by a factor of ten, the number of sources of initial capital for entrepreneurs has increased by a factor of ten, etc.

And while innovation is moving at Internet speed, this won't be limited to just internet commerce startups. It will spread to the enterprise and ultimately every other business segment.

When It's Darkest Men See the Stars

The economic downturn in the United States has had an unexpected consequence for startups – it has created more of them. Young and old, innovators who are unemployed or underemployed now face less risk in starting a company. They have a lot less to lose and a lot more to gain.

If we are at the cusp of a revolution as important as the scientific and industrial revolutions what does it mean? Revolutions are not obvious when they happen. When James Watt started the industrial revolution with the steam engine in 1775 no one said, "This is the day everything changes." When Karl Benz drove around Mannheim in 1885 no one said, "They'll be 500 million of these driving around in a century." And certainly in 1958 when Noyce and Kilby invented the Integrated Circuit the idea of a quintillion (10 to the 18th) transistors being produced each year seemed ludicrous.

Yet it's possible that we'll look back to this decade as the beginning of our own revolution. We may remember this as the time when scientific discoveries and technological breakthroughs were integrated into the fabric of society faster than they had ever been before. When the speed of how businesses operated changed forever. As the time when we reinvented the American economy and our Gross Domestic Product began to take off and the U.S. and the world reached a level of wealth never seen before. It may be the dawn of a new era for a new American economy built on entrepreneurship and innovation.

One that our children will look back on and marvel that when it was the darkest we saw the stars.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Filed under: Customer Development, Customer Development Manifesto, Venture Capital

November 18, 2010

Crisis Management by Firing Executives – There's A Better Way

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

Albert Einstein

For decades startups were managed by pretending the company would follow a predictable path (revenue plan, scale, etc.) and being continually surprised when it didn't.

That's the definition of insanity. Luckily most startups now realize there is a better way.

Startups Are Not Small Versions of Large Companies

As we described in previous posts, startups fail on the day they're founded if they are organized and managed like they are a small version of a large company. In an existing company with existing customers you 1) understand the customers problem and 2) since you do, you can specify the entire feature set on day one. But startups aren't large companies, but for decades VC's insisted that startups organize and plan like they were.

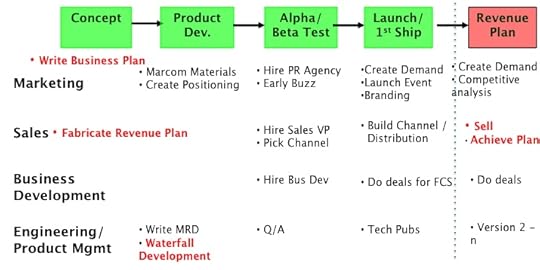

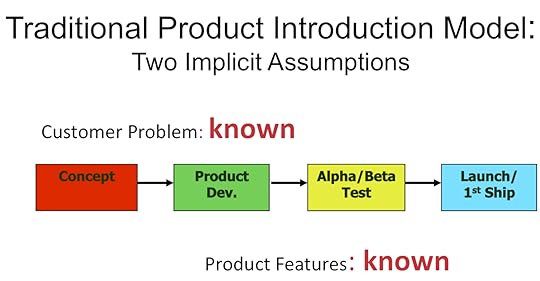

These false assumptions – that you know the customer problem and product features – led startups to organize their product introduction process like the diagram below – essentially identical to the product management process of a large company. In fact, for decades if you drew this diagram on day one of a startup VC's would nod sagely and everyone would get to work heading to first customer ship.

The Revenue Plan – The Third Fatal Assumption

Notice that the traditional product introduction model leads to a product launch and the execution of a revenue plan. The revenue numbers and revenue model came from a startups original Business Plan. A business plan has a set of assumptions (who's the customer, what's the price, what's the channel, what are the product features that matter, etc.) that make up a business model. All of these initial assumptions must be right for the revenue plan to be correct. Yet by first customer ship most of the business model hasn't been validated or tested. Yet startups following the traditional product introduction model are organized to execute the business plan as if it were fact.

Unless you were incredibly lucky most of your assumptions are wrong. What happens next is painful, predictable, avoidable, yet built into to every startup business plan.

Ritualized Crises

Trying to execute a startup revenue plan is why crises unfold in a stylized, predicable ritual after first customer ship.

You can almost set your watch to six months or so after first customer ship, when Sales starts missing its "numbers," the board gets concerned and Marketing tries to "make up a better story." The web site and/or product presentation slides start changing and Marketing and Sales try different customers, different channels, new pricing, etc. Having failed to deliver the promised revenue, the VP of Sales in a startup who does not make the "numbers" becomes an ex-VP of Sales. (The half-life of the first VP of sales of a startup is ~18 months.)

Now the company is in crisis mode because the rest of the organization (product development, marketing, etc.) has based its headcount and expenses on the business plan, expecting Sales to make its numbers. Without the revenue to match its expenses, the company is in now danger of running out of money.

Pivots By Firing Executives

A new VP of Sales (then VP of Marketing, then CEO) looks at their predecessors' strategy, and if they are smart, they do something different (they implement a different pricing model, pick a new sales channel, target different customers and/or partners, reformulate the product features, etc.)

Surprisingly we have never explicitly articulated or understood that what's really happening when we hire a new VP or CEO in a startup is that the newly hired executive is implicitly pivoting (radically changing) some portion of the business model. We were changing the business model when we changed executives.

Startups were pivoting by crisis and firing executives. Yikes.

Business Model Design and Customer Development Stack

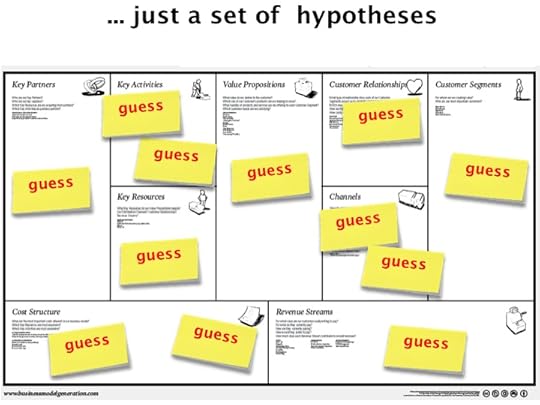

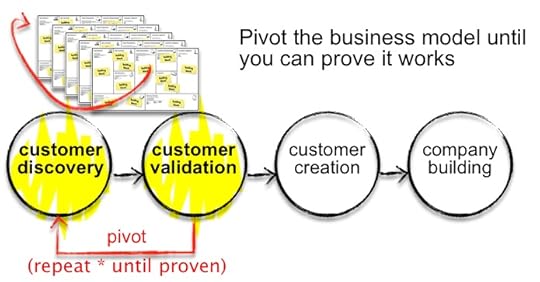

The alternative to the traditional product introduction process is the Business Model Design and Customer Development Stack. It assumes the purpose of a startup is the search for a business model (not execution.) This approach has a startup drawing their initial business model hypotheses on the Business Model Canvas.

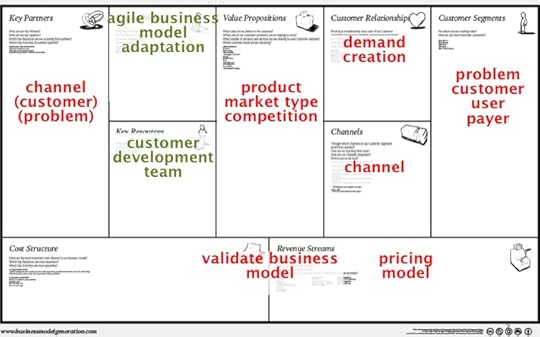

Each of the 9 business model building blocks has a set of hypotheses that need to be tested. The Customer Development process is then used to test each of the 9 building blocks of the business model. Each block in the business model canvas maps to hypotheses in the Customer Discovery and Validation steps of Customer Development.

Simultaneously the engineering team is using an Agile Development methodology to iteratively and incrementally build the Minimum Feature Set to test the product or service that make up the Value Proposition.

Pivots Versus Crises

If we accept that startups are engaged in the search for a business model, we recognize that radical shifts in a startups business model are the norm, rather than the exception.

This means that instead of firing an executive every time we discover a faulty hypothesis, we expect it as a normal course of business.

Why it's not a crisis is that the Customer Development process says, "do not staff and hire like you are executing. Instead keep the burn rate low during Customer Discovery and Validation while you are searching for a business model." This low burn rate allows you to take several swings at the bat (or shots on the goal, depending on your country.) Each pivot gets you smarter but doesn't put you out of business. And when you finally find a scalable and repeatable model, you exit Customer Validation, pour on the cash and scale the company.

Lessons Learned

"I know the Customer problem" and "I know the features to build" are rarely true on day one in a startup

These hypotheses lead to a revenue plan that is untested, yet becomes the plan of record.

Revenue shortfalls are the norm in a startup yet they create a crisis.

The traditional solution to a startup crisis is to remove executives. Their replacements implicitly iterate the business model.

The alternative to firing and crises is the Business Model/Customer Development process.

It says faulty hypotheses are a normal part of a startup

We keep the burn rate low while we search and pivot allowing for multiple iterations of the business model.

No one gets fired.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Customer Development Manifesto

November 15, 2010

Creating Startup Success – Customer Development + Business Model Design

In previous posts I've talked about what the combination of Business Model Design, Customer Development and Agile Methodologies mean to startups and intrapreneurs in large companies; it's the beginning of entrepreneurship as a science with its own rules and methodologies.

Alexander Osterwalder, who authored the Business Model Generation book, put together a slidedeck on his thoughts of what happens when you combine the business model concept to shape and structure your business ideas with the Customer Development approach to test, prove and build them.

I think his slides are great (and by far much easier on the eye then mine.)

http://www.slideshare.net/sblank/succ...

Teaching In the Big Apple

I was in New York teaching at Columbia University this week and gave a few talks around town. A nice surprise was an invite to crash a dinner in progress with Fred Wilson, Mark Suster, and Joanne Wilson. (Funny to learn latter that someone at the next table was listening to our conversation and tweeting it.)

My public talk at Columbia University was part of their Science, Technology, Engineering and Math Startup lecture series. Thanks to an invite by Professor Chris Wiggins in the Computational Biology and Bioinformatics Department (but better known as the founder of HackNY), I was honored to be shoe-horned in between Mark Suster who appeared the day before and Peter Thiel, who was going to present the next day.

It was great to see my ex Stanford teaching assistant Christina Cacioppo, now at Union Square Ventures, in the audience. (She posted her notes from the talk here.) Now I have an ex teaching assistant in VC firms on both coasts.

http://www.slideshare.net/sblank/colu...

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development

November 11, 2010

Get Out of The Building – And Win $50,000

The only thing that interferes with my learning is my education.

Albert Einstein

Entrepreneurship As A Management Science

Those of you who have been reading my blog already know that I have been talking about a new approach to entrepreneurship education called "E-School" or the Durant School of Entrepreneurship. I believe that we have now learned enough about entrepreneurship as its own management science, to rethink our approach on how to teach it.

A place to start would be by recognizing the fundamental difference between an existing company and a startup: existing companies execute business models, while startups search for a business model. (Or more accurately, startups are a temporary organization designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.) Therefore the very foundations of teaching entrepreneurship should start with how to search for a business model.

This startup search process is the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack. This solution stack proposes that entrepreneurs should first map their assumptions (their business model) and then test whether these hypotheses are accurate, outside in the field (customer development) and then use an iterative and incremental development methodology (agile development) to build the product. When founders discover their assumptions are wrong, as they inevitably will, the result isn't a crisis, it's a learning event called a pivot — and an opportunity to update the business model.

Business Model Design meets Customer Development

Lean Launchpad

So how do we teach this approach? Both Stanford and Berkeley have been extremely generous in letting me test these ideas in their engineering and business schools. In fact, starting in January, Stanford will offer Engineering 245, a.k.a the Lean Launchpad, the first hands-on class utilizing the entire business model/customer development / agile development stack. I'll be teaching this class with two world-class VC's: Ann Miura-Ko of Floodgate, and Jon Feiber of MDV.

In this class students get real world, hands-on learning on what it's like to actually start a high-tech company. This class is not about how to write a business plan. The end result is not a PowerPoint slide deck for a VC presentation. Instead students get their hands dirty talking to customers, partners and competitors as they encounter the chaos and uncertainty of how a startup actually works. They'll work in teams learning how to turn a great idea into a great company. They'll learn how to use a business model to brainstorm each part of a company and customer development to get out of the classroom to see whether anyone would want/use their product. Finally, they'll use agile development to rapidly iterate the product in class to build something customers will use and buy. Each week will be a new adventure as they test each part of their business model and then share the hard earned knowledge with the rest of the class.

But what if you're not a Stanford student and want to learn how to build a startup with the "get out of the building" experience as taught in the Lean Launchpad class?

You can.

International Business Model Competition

One of the things I have suggested is that instead of business plan competitions (which tend to focus on a static plan which is often just a series of guesses about a customer problem and the product solution), entrepreneurship educators should think about holding competitions that emulate what entrepreneurs encounter – chaos, uncertainty and unknowns. A business model competition would emulate the "out of the building" experience of the Stanford E-245 class and the customer development / business model / agile stack.

Nathan Furr, a professor at Brigham Young University, is launching the first international business model competition.

The competition will be held on January 24th 2011 (submission deadline Jan 10th) and is open to university students enrolled at least half-time anywhere in the world (more about the competition here and information packet is here). While Professor Furr's vision is to make this the Moot Corp (the championship of business plan competitions) of the business model world, the broader goal is to kick start change in the way students and educators think about how to train the next generation of entrepreneurs—Durant entrepreneurs.

Not only is this an exciting event planting a flag for the future of e-schools, but Alexander Osterwalder, who wrote the definitive book on business model design, and I will be doing the judging along with Professor Nathan Furr.

Oh yes, and by the way, the prize money is $50,000.

See you there.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

November 8, 2010

Hubris Versus Humility: The $15 billion Difference

Describing your product as "new and "never been done before" instead of "we're just like those others guys, but better" could cost your company billions. RIM and TiVo are two examples of getting it right and wrong.

Research in Motion (RIM)

By 1992 Research in Motion (RIM) had been in business for eight years, had 16 employees, sales of about $500,000 a year, and three or four business lines. That year the two founders decided to get serious about being a company, and hired a CEO. Soon, RIM was focusing on making products for people on the move, using wireless communication and digital data.

Wireless Communications

In the early 1990's two different trends were occurring in wireless communication. First, wireless voice networks – cell phone networks – had started to emerge. The ability to make a phone call untethered from a traditional phone was revolutionary and was starting to catch on fast. These new cellular phone networks were built around two-way circuit switched technology designed to move voice calls without interruption.

At the same time, digital data networks to support "pagers" were also growing rapidly. Pagers were small receive-only devices with 1 or 2-line displays that showed the phone number of who was "paging" them. Users ran to a traditional telephone and called a paging service who would read them their message. Doctors and drug dealers equally found these devices handy. Unlike the circuit-switched cell phone networks, pager networks were built around digital packet-switched technology.

Sell Directly to Businesses

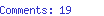

In 1996 RIM was still in the hardware business selling packet-switched wireless radio modems to OEMs. In a major strategy shift, they decided to sell a product directly to businesses. In 1997, RIM introduced the first packet-switched messaging device. It used narrowband PCS and was housed in a clamshell device with a full keyboard.

RIM Interactive Pager 900

The new device could hold names, email addresses, phone and fax numbers and incoming and outgoing messages. In 1998 RIM quickly followed this up with a next generation product with an 8-line display, ran on AA batteries and would last 500 hours.

The fact that you could send messages interactively blew people away. Underneath the hood RIM's product was a technical tour de force. But RIM decided to hide all of that from their customers.

RIM positioned the Blackberry as an "interactive pager" because pagers were something people could understand. While the device was actually was doing email, people understood it as "the pager that you could respond with." While phrases like "mobile email and packet switching" didn't mean a thing to RIM's first customers, the "interactive pager" positioning proved important in attracting early adopters.

Resegmenting an Existing Market

RIM's product needed very little explanation. If you knew what a pager was, you knew what an interactive pager was. You got it. (You might gulp at the price – paging prices were dropping like a stone ($9/month versus $99/month for a RIM interactive pager) since most people were moving from pagers to cell phone to get calls. But to businesses where instant information gave you a critical edge (Wall Street, politicians, etc.) these new capabilities were worth almost any price.

In today's language of Customer Development, RIM positioned the Blackberry as a segment of an existing market – pager users who needed two-way communication. Their intent: initial sales would come from users who already understood what the product could do so adoption would occur rapidly.

Humility

RIM, the Blackberry and its network had more inventions per square inch than most startups. The founders could have easily described the product as "the first packet-switched interactive messaging network." Or they could have said, "corporate email now seamlessly forwarded from your company's network to your pocket." They did none of that. The founders swallowed their pride and simply introduced the Blackberry as an "interactive pager." Their board, with no need to prove how smart and creative they were, agreed.

After a few years, as users became comfortable with the technology, the entire space of interactive pagers became known as the "Blackberry or "wireless email" market rather than the "interactive pager" market.

Video Recording

In 1999, about the same time RIM introduced its first interactive pager, another advanced technology company, TiVo, shipped its first product.

Recording video on magnetic tape was developed in the mid 1950's by Ampex, and had evolved into a consumer-friendly cassette by the late 1960's. VCR's caught on in the home in the late 1970's driven by movie rentals and pornography. Sales of VHS-based VCRs exploded after Sony and JVC fought a brutal standards battle (Betamax versus VHS) and when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that home taping of television programs for later viewing ("time-shifting") constituted a fair use.

But cassette tapes were still bulky and awkward. And most consumers had never mastered recording a TV program (let alone setting the clock on their VCR.)

TiVo

TiVo solved all those problems. It was the logical marriage of computers and video recording. Essentially TiVo was a computer with a hard drive integrated with a TV tuner and MPEG decoder. It digitized and compressed analog video from an antenna, cable or direct broadcast satellite. But it was the software that made the TiVo great. It was reliable. Its user interface was simple. It let users record from the familiar program guide. Since you were recording video to a hard disk, you could appear to pause live TV, instant replay, rewind or record anything.

TiVo Series 1

TiVo originally sold directly to consumers through consumer electronics stores, via Sony and Phillips and was integrated into set-top boxes from DirecTV.

Creating a New Market

TiVo's product needed very little explanation. After a demo, if you knew what a VCR was you knew what a TiVo was. You got it. (You might pause at the price – VCR prices were plummeting – $150 versus $800 for the first TiVos, but compared to a VCR it took your breath away.)

In today's language of Customer Development, a TiVo positioned as a segment of an existing market (VCR's) was a no brainer. Everyone would have immediately understood it.

Except there was one problem. The TiVo CEO hated the idea that customers might think of TiVo as a better VCR. In fact he said, "Anytime anyone says that to me, I go completely nuts. So we had this challenge of explaining, It's actually not a VCR. It's a lot more sophisticated and uses a hard disk, and therefore you can record and playback simultaneously and do clever things like pause live TV, and so on." And the board, being enamored with Silicon Valley technology, first mover advantage and concerned about the huge price gap between a VCR and TiVo, agreed.

As a result, the company instead chose to position TiVo as a New Market. In a new market when customers have no idea what the product can do, a company needs to educate potential customers about the space not the product. This results in a much slower adoption curve – the classic hockey stick.

New Market Revenue Curve

Hubris

TiVo spent the next five years trying to convince users that the box they wanted to buy as a better VCR was really something different. Hundreds of millions of dollars went into marketing campaigns to create an entirely new consumer electronics category – Digital Video Recorders. TiVo was first positioned as a "personal television system." But no one knew what that meant. Next they tried the slogan "TiVo, TV your way." Early adopters simply ignored the company's positioning buying the device in spite of the inane descriptions.

But trying to create a totally new market took its toll. TiVo had plenty of other battles to fight: competition, issues with channel partners, patent battles, as well as the movie studios, cable companies, broadcast networks and advertisers who all wanted TiVo dead. Instead the company used most its cash on marketing and advertising in trying to define a new product category and accelerate adoption.

Summary

RIM sales were $15 billion in 2010. In the last ten years they've made over $9 billion in profit.

TiVo sales were $240 million in 2010. In the last ten years they lost $400 million dollars.

How much of this can be traced back to the time, money and energy they spent on their initial positioning?

Lessons Learned

Market Type matters

No one will stop you from picking a new market.

If you do, realize you have defined a space with no customers. You now need to spend your marketing dollars in educating users about the market not your product.

In an existing market you've picked a space that has customers. Here you need to spend your marketing dollars differentiating your product from the incumbents. Are you faster and better? Are you cheaper? Do you uniquely appeal to a segment?

Filed under: Customer Development, Market Types

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers