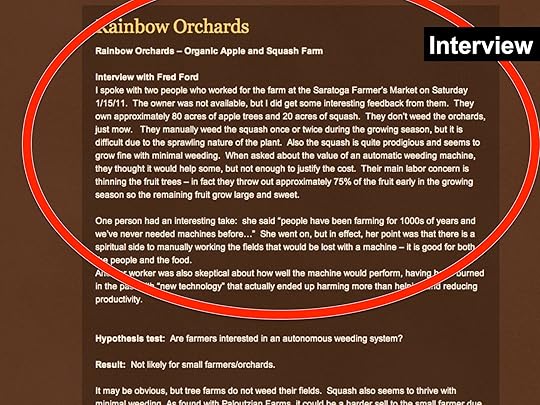

Steve Blank's Blog, page 51

August 5, 2011

Bonfire of the Vanities

When I was in my 20's, I was taught the relationship between marketing and sales over a bonfire.

—

Over thirty years ago, before the arrival of the personal computer, there were desktop computers called office workstations. Designed around the first generation of microprocessors, these computers ran business applications like word processing, spreadsheets, and accounting. They were an improvement over the dumb terminals hanging off of mainframes and minicomputers, but ran proprietary operating systems and software. My third startup, Convergent Technologies (extra credit for identifying the photo on page 2) was in the business of making these workstations.

The OEM Business

Convergent's computers were bought and then resold by other computer manufacturers – all of them long gone: Burroughs, Prime, Monroe Data Systems, ADP, Mohawk, Gould, NCR, 4-Phase, AT&T. Convergent had assembled a stellar team with founders from Digital Equipment Corporation and Intel and engineers from Xerox PARC. And once we went public, we hired a veteran VP of Sales from Honeywell.

As the company's revenues skyrocketed, Convergent started a new division to make a multi-processor Unix-based mini-computer. I had joined the company as the product marketing manager and now found myself as the VP of marketing for this new division. We were a startup inside a $200 million company. A marketer for 5 years, I thought I knew everything and proceeded to write the data sheets for our new computer.

Since this new computer was very complicated – it was a pioneer in multi-processing– I concluded it needed an equally detailed data sheet. In fact, when I was done, the datasheet describing our new computer, proudly called the MegaFrame, was 16 pages long. I fact-checked the datasheet with my boss (who would be my co-founder at Epiphany) and the rest of the engineering team. We all agreed it was perfect. We'd left no stone unturned in answering every possible question anyone could ever have about our system. As we typically did, I printed up several thousand to send out to the sales force.

The day the datasheets came back from the printers, I sent the boxes to the sales department in Convergent's corporate headquarters, a separate building across the highway, and sent a copy to our CEO and the new VP of Sales. (I was thinking it was such a masterpiece I might get an "attaboy" or at least a "wow, thanks for doing all the hard work for our sales organization.")

So when I got a call from the VP of Sales who said, "Steve, just read your new datasheet. Why don't you come over to corporate. We have a surprise for you," I smugly thought, "They probably thought it was so good, I'm going to get a thank you or an award or maybe even a bonus."

Fahrenheit 451

I got in my car to make the five minute drive over the freeway. Turning into the parking lot, I noticed smoke coming from the far end of the lawn. As I parked and walked closer I noticed a crowd of people around what seemed to be an impromptu campfire. "What the heck??" As an ex Sales and Marketing VP, our CEO had a Silicon Valley reputation for outrageous stunts so I wondered what it was this time - a spur-of-the-moment BBQ? A marshmallow roast?

Heading to a meeting with the VP of Sales, I almost walked past the crowd into the building until I heard the VP of Sales call me over to the fire. He was there with our CEO feeding things into the fire. In fact as I got closer, it looked like the campfire was being entirely fed by paper. "Here, toss these in," they said as they handed me a stack of…

Oh, my g-d they're burning my datasheets!!!

The Bonfire of the Vanities

I stood there stunned as I realized that my 16-page carefully constructed, brilliantly written, technically accurate datasheets were being destroyed en masse. I guess I was speechless for so long that the VP of Sales took pity on me and asked, "Steve, do you know we have a sales force?" I managed to stammer out, "Yes, of course." He asked, "Do you know how much we pay them?" Again, I managed to answer, "A lot." Then he got serious and started to explain what was going on. (In the meantime our CEO watched my reaction with a big grin on his face.) He said, "Steve, I've never seen such a perfect datasheet. It answers every possible question a prospective customer could have about our product. The problem is that our computer sells for $150,000. No one is going to buy it from the datasheet. In fact, reading these, the only thing your datasheet will do is give a prospective customer a reason for saying "no" before our salespeople ever get to talk to them.

"Do you mean you want a datasheet with less information?!" I asked, not at all sure that I was hearing him correctly. "Yes, exactly. Your job in marketing is to get customers interested enough to engage our sales force, to ask for more information or better, to set up a meeting. No one is going to buy our computer from a datasheet, but they will from a salesman."

Marketing to Match the Channel

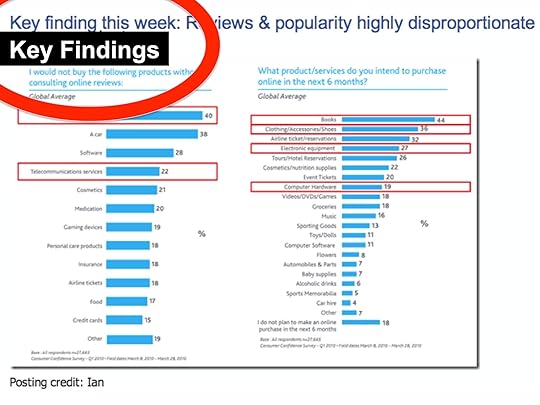

It took me a few weeks to get over the lesson, but it stuck. When selling a physical product through direct sales, Marketing's job is to drive end user demand into the sales channel. Marketing creates a series of marketing activities at each stage of the sales funnel to generate awareness, then interest, then consideration and finally purchase. [image error]

Ironically, over the last decade, I've seen web startups have the opposite problem. For web sites with an ecommerce component, the site itself is supposed to both create demand and close the sale. Web designers have to do the work of both the marketing and the sales departments.

Lessons Learned

Marketing materials need to match the channel

Marketings job in direct sales channels with consultative sales need to drive demand to the salesforce

Indirect channels require marketing material with more information than a direct channel

Web sites that sell products combine sales and marketing

Confusing these can get you your own bonfire

Filed under: Convergent Technologies, Marketing

July 28, 2011

Eureka! A New Era for Scientists and Engineers

The combination of Venture Capital and technology entrepreneurship is one of the great business inventions of the last 50 years. It provides private funds for untested and unproven technology and entrepreneurs. While most of these investments fail, the returns for the ones that win are so great they make up for the failures. The cultural tolerance for failure and experimentation, and a financial structure which balanced risk, return and obscene returns, allowed this system flourish in technology clusters in United States, particularly in Silicon Valley.

Yet this system isn't perfect. From the point of view of scientists and engineers in a university lab, too often entrepreneurship in all its VC-driven glory – income statements, balance sheets, business plans, revenue models, 5-year forecasts, etc. – seems like another planet. There didn't seem to be much in common between the Scientific Method and starting a company. And this has been a barrier to commercializing the best of our science research.

Until today.

Today, the National Science Foundation (NSF) – the $6.8-billion U.S. government agency that supports research in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering - is changing the startup landscape for scientists and engineers. The NSF has announced the Innovation Corps – a program to take the most promising research projects in American university laboratories and turn them into startups. It will train them with a process that embraces experimentation, learning, and discovery.

Today, the National Science Foundation (NSF) – the $6.8-billion U.S. government agency that supports research in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering - is changing the startup landscape for scientists and engineers. The NSF has announced the Innovation Corps – a program to take the most promising research projects in American university laboratories and turn them into startups. It will train them with a process that embraces experimentation, learning, and discovery.

The NSF will fund 100 science and engineering research projects every year. Each team accepted into the program will receive $50,000.

To commercialize these university innovations NSF will be putting the Innovation Corps (I-Corps) teams through a class that teaches scientists and engineers to treat starting a company as another research project that can be solved by an iterative process of hypotheses testing and experimentation. The class will be a version of the Lean LaunchPad class we developed in the Stanford Technology Ventures Program, (the entrepreneurship center at Stanford's School of Engineering).

—–

This is a big deal. Not just for scientists and engineers, not just for every science university in the U.S., but in the way we think about bringing discoveries ripe for innovation out of the university lab. If this program works it will change how we connect basic research to the business world. And it will lead to more startups and job creation.

—–

Introducing the Innovation-Corps

The NSF Innovation-Corps program (I-Corps) is designed to help bridge the gap between the many scientists and engineers with innovative research and technologies, but little knowledge of the first steps to take in starting a company.

I-Corps will help scientists take the first steps from the research lab to commercialization.

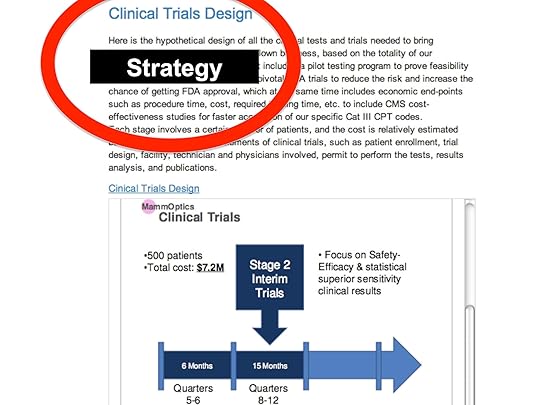

Over a period of six months, each I-Corps team, guided by experienced mentors (entrepreneurs and VC's) will build their product and get out of their labs (and comfort zone) to discover who are their potential customers, and how those customers might best use the new technology/invention. They'll explore the best way to deliver the product to customers, the resources required, as well as competing technologies. They will answer the question, "What value will this innovation add to the marketplace? And they'll do this using the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack.

At the end of the program each team will understand what it will takes to turn their research into a commercial success. They may decide to license their intellectual property based on their research. Or they may decide to cross the Rubicon and try to get funded as a startup (with strategic partners, investors, or NSF programs for small businesses). At the end of the class there will be a Demo Day when investors get to see the best this country's researchers have to offer.

What Took You So Long

A first reaction to the NSF I-Corps program might be, "You mean we haven't already been doing this?" But on reflection it's clear why. The common wisdom was that for scientists and engineers to succeed in the entrepreneurial world you'd have to teach them all about business. But it's only now that we realize that's wrong. The insight the NSF had is that we just need to teach scientists and engineers to treat business models as another research project that can be solved with learning, discovery and experimentation.

And Stanford's Lean LaunchPad class could do just that.

Join the I-Corps

Today at 2pm the National Science Foundation is publishing the application for admission (what they call the "solicitation for proposals") to the program. See the NSF web page here.

The syllabus for NSF I-Corps version of the Lean LaunchPad class can be seen here.

Along with a great teaching team at Stanford, world-class VC's who get it, and foundation partners, I'm proud to be a part of it.

This is a potential game changer for science and innovation in the United States.

Join us.

Apply now.

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching, Venture Capital

July 25, 2011

How Scientists and Engineers Got It Right, and VC's Got It Wrong

Scientists and engineers as founders and startup CEOs is one of the least celebrated contributions of Silicon Valley.

It might be its most important.

———-

ESL, the first company I worked for in Silicon Valley, was founded by a PhD in Math and six other scientists and engineers. Since it was my first job, I just took for granted that scientists and engineers started and ran companies. It took me a long time to realize that this was one of Silicon Valley's best contributions to innovation.

Cold War Spin Outs

In the 1950's the groundwork for a culture and environment of entrepreneurship were taking shape on the east and west coasts of the United States. Each region had two of the finest research universities in the United States, Stanford and MIT, which were building on the technology breakthroughs of World War II and graduating a generation of engineers into a consumer and cold war economy that seemed limitless. Each region already had the beginnings of a high-tech culture, Boston with Raytheon, Silicon Valley with Hewlett Packard.

However, the majority of engineers graduating from these schools went to work in existing companies. But in the mid 1950's the culture around these two universities began to change.

Stanford – 1950's Innovation

At Stanford, Dean of Engineering/Provost Fred Terman wanted companies outside of the university to take Stanford's prototype microwave tubes and electronic intelligence systems and build production volumes for the military. While existing companies took some of the business, often it was a graduate student or professor who started a new company. The motivation in the mid 1950's for these new startups was a crisis – we were in the midst of the cold war, and the United States military and intelligence agencies were rearming as fast as they could.

Why It's "Silicon" Valley

In 1956 entrepreneurship as we know it would change forever. At the time it didn't appear earthshaking or momentous. Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, the first semiconductor company in the valley, set up shop in Mountain View. Fifteen months later eight of Shockley's employees (three physicists, an electrical engineer, an industrial engineer, a mechanical engineer, a metallurgist and a physical chemist) founded Fairchild Semiconductor. (Every chip company in Silicon Valley can trace their lineage from Fairchild.)

The history of Fairchild was one of applied experimentation. It wasn't pure research, but rather a culture of taking sufficient risks to get to market. It was learning, discovery, iteration and execution. The goal was commercial products, but as scientists and engineers the company's founders realized that at times the cost of experimentation was failure. And just as they don't punish failure in a research lab, they didn't fire scientists whose experiments didn't work. Instead the company built a culture where when you hit a wall, you backed up and tried a different path. (In 21st century parlance we say that innovation in the early semiconductor business was all about "pivoting" while aiming for salable products.)

The Fairchild approach would shape Silicon Valley's entrepreneurial ethos: In startups, failure was treated as experience (until you ran out of money.)

Scientists and Engineers as Founders

In the late 1950's Silicon Valley's first three IPO's were companies that were founded and run by scientists and engineers: Varian (founded by Stanford engineering professors and graduate students,) Hewlett Packard (founded by two Stanford engineering graduate students) and Ampex (founded by a mechanical/electrical engineer.) While this signaled that investments in technology companies could be very lucrative, both Shockley and Fairchild could only be funded through corporate partners – there was no venture capital industry. But by the early 1960′s the tidal wave of semiconductor startup spinouts from Fairchild would find a valley with a growing number of U.S. government backed venture firms and limited partnerships.

A wave of innovation was about to meet a pile of risk capital.

For the next two decades venture capital invested in things that ran on electrons: hardware, software and silicon. Yet the companies were anomalies in the big picture in the U.S. – there were almost no MBA's. In 1960's and '70's few MBA's would give up a lucrative career in management, finance or Wall Street to join a bunch of technical lunatics. So the engineers taught themselves how to become marketers, sales people and CEO's. And the venture capital community became comfortable in funding them.

Medical Researchers Get Entrepreneurial

In the 60's and 70's, while engineers were founding companies, medical researchers and academics were skeptical about the blurring of the lines between academia and commerce. This all changed in 1980 with the Genentech IPO.

In 1973, two scientists, Stanley Cohen at Stanford and Herbert Boyer at UCSF, discovered recombinant DNA, and Boyer went on to found Genentech. In 1980 Genentech became the first IPO of a venture funded biotech company. The fact that serious money could be made in companies investing in life sciences wasn't lost on other researchers and the venture capital community.

Over the next decade, medical graduate students saw their professors start companies, other professors saw their peers and entrepreneurial colleagues start companies, and VC's started calling on academics and researchers and speaking their language.

Scientists and Engineers = Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Yet when venture capital got involved they brought all the processes to administer existing companies they learned in business school – how to write a business plan, accounting, organizational behavior, managerial skills, marketing, operations, etc. This set up a conflict with the learning, discovery and experimentation style of the original valley founders.

Yet because of the Golden Rule, the VC's got to set how startups were built and managed (those who have the gold set the rules.)

Fifty years later we now know the engineers were right. Business plans are fine for large companies where there is an existing market, product and customers, but in a startup all of these elements are unknown and the process of discovering them is filled with rapidly changing assumptions.

Startups are not smaller versions of large companies. Large companies execute known business models. In the real world a startup is about the search for a business model or more accurately, startups are a temporary organization designed to search for a scalable and repeatable business model.

Yet for the last 40 years, while technical founders knew that no business plan survived first contact with customers, they lacked a management tool set for learning, discovery and experimentation.

Earlier this year we developed a class in the Stanford Technology Ventures Program, (the entrepreneurship center at Stanford's School of Engineering), to provide scientists and engineers just those tools – how to think about all the parts of building a business, not just the product. The Stanford class introduced the first management tools for entrepreneurs built around the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack. (You can read about the class here.)

So what?

Starting this Thursday, scientists and engineers across the United States will once again set the rules.

Stay tuned for the next post.

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Venture Capital

July 19, 2011

The $10 million Photo and other VC Stories

While on vacation I had a phone interview with Kevin Ohannessian of Fast Company who wanted a few "funding stories." Here are two of them. Apologies for the rambling stream of consciousness. The original interview in Fast Company can be seen here.

Throw in the Photo and You Have a Deal

When we were trying to raise money for E.piphany, my last startup, I was negotiating with a venture capital firm called Infinity Capital. They really wanted to invest, but it was the beginning of the bubble, and I wanted (what was then) an absurd valuation. All we had were six slides, and I wanted a $10 million post-money valuation. But it was my eighth startup and my partner Ben was even more experienced: ex VC, ex Harvard Computer Science professor, genius at building products and teams. I had sat on a board of an Electronic Design Automation company with this VC, and we had gotten to know each other. So when I wanted to start a company he wanted to fund us. We had gone back and forth with them on valuation, but this was a new firm and they wanted to close a deal with us.

After about our fifth meeting I'm in their conference room. I say, "Why can't you guys do a $10 million post money valuation?" Picking the biggest number I could think of for three founders without a product a semi-coherent idea and badly written slides. Finally they admitted, "Steve, we're a new fund; everybody will think we are idiots if we do that." I said, "All right. Can you do some other number close to my number?" So I stepped out of the room as they caucused, and they called me back in 10 minutes later and said, "So listen. We can do $9.99 million." I'm trying to play poker with the deal, and one of the partners at the time was a great photographer–the firm had big prints of his on the walls. I was really in love with the one in the boardroom. So without thinking, when they made me that offer, trying to keep a straight face, I reached behind me, grabbed the photo off the wall and slammed it on the desk, and said, "If you throw this photo in, you got the deal!"

The $10 Million Photo

The look on their face was utter astonishment. I was thinking it was because I was being creative by throwing the photo in, but then I noticed that this cloud of dust was settling around me. I turn around and looked at the wall and it turned out the photo had been bolted into the drywall. And there was now a hole–I literally ripped a part of their boardroom wall off as I was accepting the offer. Without missing a beat they said, "Yes, you can have the photo. But we're going to have to deduct $500 to repair our wall." And I said, "Deal." And that's how E.piphany got its Series A.

Invest in the Team

Before we closed our Series A with Infinity, I had called on Mohr, Davidow Ventures, the firm which had funded my last company, Rocket Science. The senior partner at the time was Bill Davidow, a marketing legend and a hero of mine who had also funded other Enterprise software companies. I went in and pitched Bill the idea about how to automate the marketing domain. He gave me 15 minutes, then as politely as he could do it, walked me out the door and said, "Stupidest idea I ever heard, Steve. Enterprise software means across the Enterprise. Marketing is just one very small department." As he was walking me out, I remember as I physically crossed the threshold of the door that: A. He was right, and B. I figured out how to solve the problem of making our product useful across the entire enterprise. So E.piphany went from a bad idea to a good idea by being thrown out by a VC who gave me advice that made the company. He has reminded me since, "Sometimes you invest in the idea, but you should always be investing in the people. If I would've remembered who you were, I would've known you would figure it out."

(Kleiner Perkins would do the Series B round for E.piphany. After our IPO Infinity's and Kleiner Perkins' investment in Epiphany would be worth $1 billion dollars to each of them.)

I still have the photo.

Back from vacation soon.

Filed under: E.piphany, Venture Capital

July 6, 2011

On Vacation

June 22, 2011

The Internet Might Kill Us All

My friend Ben Horowitz and I debated the tech bubble in The Economist. An abridged version of this post was the "closing" statement to Ben's rebuttal comments. Part 1 is here and Part 2 here. The full version is below.

—————————————————

It's been fun debating the question, "Are we in a tech bubble?" with my colleague Ben Horowitz. Ben and his partner Marc Andreessen (the founder of Netscape and author of the first commercial web browser on the Internet) are the definition of Smart Money. Their firm, Andreessen/Horowtiz, has been prescient enough to invest in social networks, consumer and mobile applications and the cloud long before others. They understood the ubiquity, pervasiveness and ultimate profitability of these startups and doubled-down on their investments.

My closing arguments are below. I've followed them with a few observations about the Internet that may help frame the scope of the debate.

Are we in the beginnings of a tech bubble – yes.

Prices for both private and public tech valuations exceed any rational valuation to their current worth. In 5 to 10 years most of them will be worth a fraction of their IPO price. A few will be worth much, much more.

Is this tech bubble as broad as the 1995-2000 dot.com bubble – no.

While labeled the "dot.com" bubble, valuations went crazy across a wide range of technology sectors including telecommunications, enterprise software and biotech, not just the Internet.

Are tech bubbles necessarily bad – no.

A bubble is simply the redistribution of wealth from Marks to the Smart Money and Promoters. I hypothesize that unlike bubbles in other sectors – tulips, Florida land prices, housing, financial – tech bubbles create lasting value. They finance companies that invest in new technologies, new ideas and new products. And it appears that at least in Silicon Valley, a larger percentage of money made in the last tech bubble is recirculated back into investments into the next generation of tech startups.

While most of the social networks, cloud computing, web and mobile app companies we see today will fail, a few will literally remake our lives.

Here are two views how.

The Internet May Liberate Us

In the last year, we've seen Social Networks enable new forms of peaceful revolution. To date, the results of Twitter and Facebook are more visible on the Arab Street than Wall Street.

One of the most effective weapons in the Cold War was the mimeograph machine and the VCR. The ability to copy and disseminate banned ideas undermined repressive regimes from Poland to Iran to the Soviet Union.

In the 21st century, authoritarian governments still fear their own people talking to each other and asking questions. When governments shut down Google, Twitter, Facebook, et al, they are building the 21st century equivalent of the Berlin Wall. They are admitting to the world that the forces of oppression can't stand up to 140 characters of the truth.

When these governments build "homegrown" versions of these apps, the Orwellian prophecy of the Ministry of the Truth lives in each distorted or missing search result. Absent war, these regimes eventually collapse under their own weight. We can help accelerate their demise by building tools which allow people in these denied areas access to the truth.

Yet the same set of tools that will free hundreds of millions of people may end their lives in minutes.

The Internet May Kill Us

The next war will more than likely occur via the Internet. It may be over in minutes. We may be watching the first skirmishes.

In the 20th century, the economies of first-world countries became dependent on a reliable supply of food, water, electricity, transportation and telephone. Part of waging war was destroying that physical infrastructure. (The Combined Bomber Offensive of Germany and occupied Europe during WWII was designed to do just that.)

In the last few years, most first world countries have become dependent on the Internet as one of those critical parts of our infrastructure. We use the net in four different ways: 1) to control the physical infrastructure we built in the 20th century (food, water, electricity, transportation and communications); 2) as the network for our military interconnecting all our warfighting assets, from the mundane of logistics to command and control systems, weapons systems and targeting systems; 3) as commercial assets that exist or can operate only if the net exists including communication tools (email, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) and corporate infrastructure (Cloud storage and apps); 4) for our banking and financial systems.

Every day hackers demonstrate how weak the security of our corporate and government resources are. Stealing millions of credit cards occurs on a regular basis. Yet all of these are simply crimes not acts of war.

The ultimate in asymmetric warfare

In the 20th century, the United States was continually unprepared for an adversary using asymmetric warfare — the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Soviet Anthrax warheads on their ICBMs during the cold war, Vietnam and guerilla warfare, and the 9/11 attacks.

While hacker attacks against banks and commercial institutions make good press, the most troubling portents of the next war were the Stuxnet attack on the Iranian centrifuge facilities, the compromise of the RSA security system and the penetration of American defense contractors. These weren't Lulz or Anonymous hackers, these were attacks by government military projects with thousands of programmers coordinating their efforts. All had a single goal in mind: to prepare to use the internet to destroy a country without physically killing its people.

Our financial systems (banks, stock market, credit cards, mortgages, etc.) exist as bits. Your net worth and mine exists because there are financial records that tell us how many "dollars" (or Euros, Yen, etc.) we own. We don't physically have all that money. It's simply the sum of the bits in a variety of institutions.

An attack on the United States could begin with the destruction of all those financial records. (A financial institution that can't stop criminal hackers would have no chance against a military attack to destroy the customer data in their systems. Because security is expensive, hard, and at times not user friendly, the financial services companies have fought any attempt to mandate hardened systems.) Logic bombs planted on those systems will delete all the backups once they're brought on-line. All of it gone. Forever.

At the same time, all cloud-based assets, all companies applications and customer data will be attacked and deleted. All of it gone. Forever.

Major power generating turbines will be attacked the same way Stuxnet worked– over and under-speeding the turbines and rapidly cycling the switching systems until they burn out. A major portion of our electrical generation capacity will be off-line until replacements can be built. (They are currently built in China.)

Our transportation infrastructure– air traffic control systems, airline reservations, package delivery companies– will be hacked and our GPS infrastructure will be taken down (hacked, jammed or physically attacked.)

While some of our own military systems are hardened, attackers will shut down the soft parts of the military logistics and communications systems. Since our defense contractors have been the targets of some of the latest hacks, our newest weapons systems may not work, or worse if used, may have been reprogrammed to destroy our own assets.

An attacker may try to mask its identity by making the attack appear to come from a different source. With our nation in an unprecedented economic collapse, our ability to retaliate militarily against a nuclear-armed opponent claiming innocence and threatening a response while we face them with unreliable weapons systems could make for a bad day. Our attacker might even offer economic assistance as part of the surrender terms.

These scenarios make the question, "Are we in a tech bubble?" seem a bit ironic.

It Doesn't Have to Happen

During the Cold War the United States and the Soviet Union faced off with an arsenal of strategic and tactical nuclear weapons large enough to directly kill hundreds of millions of people and plunge the planet in a "Nuclear Winter," which could have killed billions more. But we didn't do it. Instead, today the McDonalds in plazas labeled "Revolutionary Square" has been the victory parade for democracy and capitalism.

It may be that we will survive the threat of a Net War like we did the Cold War and that the Internet turns out to be the birth of a new spring for us all.

Filed under: Family/Career, Secret History of Silicon Valley, Venture Capital

June 17, 2011

Are You the Fool at The Table?

My friend Ben Horowitz and I debate the tech bubble in The Economist. This post is the "rebuttal" statement to Ben's opening comments.

An edited version of this post originally appeared as part 2 of 3. Part 1 is here.

———————————————————————————–

You've got to know when to hold 'em

Know when to fold them

Know when to walk away

Know when to run

Kenny Rogers – The Gambler

My esteemed colleague Ben Horowitz essentially makes four arguments: 1) look at how relatively cheap Apple, Google and Amazon stock is compared to their growth; 2) Major technology cycles tend to be around 25 years long with the bulk of the purchases occurring in the last five-to-ten years. The major adoption wave for the Internet technology platform will hit in the next 8 years; 3) the economics of building Internet businesses has changed; 4) the markets are much bigger.

Therefore Ben concludes that boom is coming…and do you want to miss it because it has the possibility of becoming a bubble?

If this were a magic act, we'd suggest that Ben's arguments are misdirection. To answer the question before the house, "Are we in a tech bubble?" Ben offers that as Apple, Google and Amazon survived the dot.com crash, we can ignore the fate of the thousands of failed public and private dot.com companies when the bubble burst in March of 2000. I believe the issue isn't whether we're on a 25-year tech cycle or that the next 8 years are really going to be great. The issue is whether the next 100+ tech IPO's carried by this bubble will be worth their offering price in 8 years.

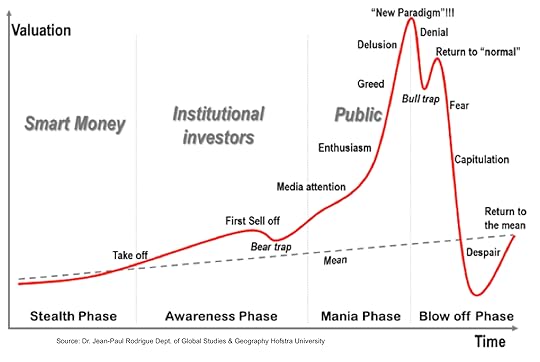

One of the least understood parts of a bubble is that there are five types of participants: Smart Money, the Shills, the Marks, the True Believers and the Promoters. Understanding the motivations of these different groups help make sense out of the bubble chart below.

Smart Money are prescient angel investors and Venture Capitalists who started investing in social networks, consumer and mobile applications and the cloud 3, 4 or 5 years ago. They helped build these struggling ventures into the Facebooks', Twitters', and Zyngas' before anyone else appreciated these companies could have hundreds of millions of users with off-the-chart revenue and profits.

In a bubble the smart money doubles down on their investment in the awareness phase, but when it starts becoming a mania – the smart money cashes out. (Really smart money recognizes it's a bubble and bets against it.) They manage this all with knowledge of the game they're playing, but they don't hype it, talk about it or fan the flames. They know others will.

The Shills are the middlemen in a bubble. They profit from the boom times. They're the mortgage brokers and real estate agents in the housing bubble, the investment bankers and technology press in the dot.com bubble. Since it's in their interest to keep the bubble going, they'll tell you that housing always goes up, that these bonds are guaranteed by a big bank, and that this tech stock is worth its opening price. All the stories peddled by Shills have at their heart why "it's a new age" and why "all the old ways of measuring value are obsolete." And why "you'll be an idiot if you don't jump in and reap the rewards and cash out."

The Marks are your neighbors or parents or grandparents. They're not domain experts. They know nothing about real estate, financial markets or tech stocks, but they don't want to miss the "investment opportunity of a lifetime". They hear reassurance from the Shills and take their advice at face value, never asking or questioning the Shills financial incentives to sell you this house/mortgage/tech stock. They see others making extraordinary amounts of money at the start of the mania (just buy a condo or two and you can sell them in six months.) What no one tells the Marks is that as they're buying, the smart money and institutional investors are quietly pulling out and selling their assets.

The True Believers don't financially participate in the bubble like the Marks (lack of assets, timidity, or time) but they could if they would. They have no rational evidence to believe, but for them it's a "faith-based" belief. By their numbers they give comfort to the Mark's around them.

The Promoters are the ones who keep the bubbles inflated even when they know that the asset exceeds its fundamental value by a large margin. While Shills have no credibility, Promoters have "brand-name" credibility that makes the Marks trust them. What makes the role of the Promoter egregious is that they are a small subset of the Smart Money. They loudly tell the Marks and Shills that everything is just fine, enticing them to buy into the bubble, even as the Promoters are liquidating their own positions.

Investment banks who sold CDO's (synthetic collateralized debt obligations,) in the financial meltdown and the mortgage lenders in the housing bubble are just two examples. Some investment banks actually bet that the very investments they were selling their customers would fail. There's a special place in hell waiting for these guys (only because our political and financial regulatory system won't deal with them while they're on earth.)

To support his position Ben used a quote from Warren Buffett I wish I had found, "The only way you get a bubble is when a very high percentage of the population buys into some originally sound premise…that becomes distorted as time passes and people forget the original sound premise and start focusing solely on the price action…

The "facts" that Ben raises, "the size and scale of these new markets have never been seen before; some of these applications and companies will reach billions of customers, generate unprecedented revenues and profits," are likely true. But they don't support his justification of the bubble valuations we are seeing for companies filing for IPO's (Pandora Media just priced its IPO at $2.6 billion dollars while admitting it will have operating losses through the end of fiscal 2012.) But to support his position for future valuations Ben lists the low price/earnings ratios of Apple, Amazon, Google, Salesforce.com. He argues that if we are in a bubble these companies ought to have their prices inflated as well.

It turns out that's not how a bubble works. Bubbles attract Marks and Shills to new shiny toys, not existing ones…, Apple, Amazon, et al are not the current objects of desire of this bubble. The question is, are we in a new tech bubble? Do the new wave of social/web/mobile/cloud companies going public have valuations which exceeds their fundamental value by a large margin? (today and in the foreseeable future.)

In other words, "would you want your mother to buy these stocks to hold them – or flip them?"

Every bubble is a big-stakes game – played for keeps. In it the usual cast of characters appear; the Smart Money, the Shills, the Marks and the Promoters.

There's a saying in Poker, "If you can't figure out who the Mark is at the table, it's you."

Filed under: Venture Capital

June 15, 2011

The Next Bubble – Don't Get Fooled Again

My friend, Ben Horowitz, and I debate the tech bubble in The Economist.

This post originally appeared as part 1 of 3

———————————————————————————–

We won't get fooled again

We don't get fooled again

Don't get fooled again

No, no!

First, let us start with a definition of a tech bubble.

A tech bubble is the rapid inflation in the valuation of public and private technology companies that exceeds their fundamental value by a large margin. It is accompanied by the rationalisation of the new pricing, and then followed by a spectacular crash in value. (It also has the "smart money" investing early and taking profits before the crash.)

Bubbles are not new; we have had them for hundreds of years (the Tulip Mania, South Sea Company, Mississippi Company, etc.). And in the last decade, we have had the dot.com bust and the housing bubble. This tech bubble is unfolding just like all the other bubbles before it.

Today, the signs of the new bubble are the Linked-In initial public offering (IPO), Facebook's stratospheric valuation and the rapid rise of early-stage startup valuation. Hiring technology talent in Silicon Valley is getting difficult, and the time it takes to drive across Palo Alto has tripled—all signs of the impending apocalypse.

Dr Jean-Paul Rodrigue, in the Department of Global Studies & Geography at Hofstra University, observed that bubbles have four phases; stealth, awareness, mania and blow-off. I contend that we are approaching the early part of the mania phase.

In the stealth phase, prescient angel investors and Venture Capitalists (VCs) start investing in an industry or market segment that others have not yet found. In the case of this bubble, it was social networks, consumer and mobile applications, and the cloud. VCs who understood the ubiquity, pervasiveness and ultimate profitability of these startups doubled-down on their investments. Long before others, they saw that these applications could have hundreds of millions of users with "off the chart" revenue and profits.

The awareness phase is where other later-stage investors start to notice the momentum, bringing additional money in and pushing prices higher. The Russian investment group, DST, is an example, with their $200 million investment in Facebook, at a $10 billion valuation, in 2009. This was followed by another $500 million investment (along with Goldman Sachs) in 2011, at a $50 billion valuation. Meanwhile, the bubble for "seed stage" startups began when Ron Conway's Silicon Valley Angels and DST guaranteed every startup out of a YCombinator $150,000. And it was hammered home with Color—a startup without a product—raising $40 million, at a reputed $100 million valuation, from brand name VCs who should have known better. When they did launch their product, it was compared to boo.com, and entered the dot.com bubble hall of infamy. Meanwhile, smart VCs continue to invest in this segment and increase their ownership of existing companies. The technology blogs (TechCrunch, et al.) start cheerleading, and the general business press/blogs start paying attention. And all of the investors trot out explanations of "why—this time—everything is different".

We have just entered the mania phase. The Linked-in IPO valued the company at $8.9 billion at the end of the first day of trading. It sent a signal that there is an irrational demand for tech IPOs. Silicon Valley startups are falling over each other to file their S-1 documents to go public.

We have just entered the mania phase. The Linked-in IPO valued the company at $8.9 billion at the end of the first day of trading. It sent a signal that there is an irrational demand for tech IPOs. Silicon Valley startups are falling over each other to file their S-1 documents to go public.

Some precursors to the bubble happened when Chinese Internet companies listed on United States stock exchanges. In December 2010, Youku—the YouTube of China—went public, with a valuation of $4.4 billion at the end of the first day (on $58.9 million in 2010 sales). In May 2011, RenRen—the Facebook of China—had a first day valuation of $7.4 billion (on $76.5 million in 2010 sales).

Dr Rodrigue's description of what happens next sounds familiar: "the public jumps in for this 'investment opportunity of a lifetime'. The expectation of future appreciation becomes a 'no brainer'…Floods of money come in creating even greater expectations and pushing prices to stratospheric levels. The higher the price, the more investments pour in. Unnoticed from the general public, the smart money as well as many institutional investors are quietly pulling out and selling their assets…Unbiased opinion about the fundamentals becomes increasingly difficult to find as many players are heavily invested and have every interest to keep asset inflation going."

"The market gradually becomes more exuberant as 'paper fortunes' are made and greed sets in. Everyone tries to jump in and new investors have absolutely no understanding of the market, its dynamic and fundamentals…statements are made about entirely new fundamentals implying that a 'permanent high plateau' has been reached to justify future price increases."

We are seeing this bubble unfold by the book.

No one doubts that social networks and web and mobile applications are reinventing commerce. Obviously, some of these companies will have hundreds of millions of customers, unprecedented revenue growth and great profits. Yet none of these companies have earned the valuations that they are receiving.

For all of these reasons, I believe this House should vote in favor of the motion before it.

Filed under: Venture Capital

June 8, 2011

The Democratization of Entrepreneurship

Last week I had 15 Finnish entrepreneurs out to the ranch (Aalto University has a partnership with Stanford's Technology Ventures Program.) Monday we hosted 40 Danish entrepreneurs for dinner and today its graduate students from Chalmers University in Sweden.

Looks like the ice is melting in Scandinavia.

Welcome to the democratization of entrepreneurship.

Hermione Way of TheNextWeb grabbed me for a short interview below that covers the challenges and opportunities of startups outside of Silicon Valley and the never ending discussion of the "new bubble." (Skip the first minute.)

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

June 2, 2011

Reinventing the Board Meeting – Part 2 of 2 – Virtual Valley Ventures

There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come

Victor Hugo

When The Boardroom is Bits

A revolution has taken hold as customer development and agile engineering reinvent the Startup process. It's time to ask why startup board governance has failed to keep pace with innovation. Board meetings that guide startups haven't changed since the early 1900's.

It's time for a change.

Reinventing the board meeting may allow venture-backed startups a more efficient, productive way to direct and measure their search for a profitable business model.

Reinventing the board meeting may offer angel-funded startups that don't have formal boards or directors (because of geography or size of investment) to attract experienced advice and investment outside of technology clusters (i.e. Silicon Valley, New York).

Here's how.

A Hypothesis – The Boardroom As Bits

Startups now understand what they should be doing in their early formative days is search for a business model. The process they use to guide their search is customer development. And to track their progress startups now have a scorecard to document their week-by-week changes – the business model canvas.

Yet even with all these tools, early stage startups still need to physically meet with advisors and investors. That's great if you can get it. But what if you can't?

What's missing is a way to communicate all this complex information and get feedback and guidance for startups who cannot get advice in a formal board meeting.

We propose that early stage startups communicate in a way that didn't exist in the 20th century – online – collaboratively through blogs.

We suggest that the founders/CEO invest 1 hour a week providing advisors and investors with "Continuous Information Access" by blogging and discussing their progress online in their startup's search for a business model. They would:

Blog their Customer Development progress as a narrative

Keep score of the strategy changes with the Business Model Canvas

Comment/Dialog with advisors and investors on a near-realtime basis

What Does this Change?

1) Structure. Founders operate in a chaotic regime. So it's helpful to have a structure that helps "search"

for a business model. The "boardroom as bits" uses Customer Development as the process for the search, and the business model canvas as the scorecard to keep track of the progress, while providing a common language for the discussion.

This approach offers VC's and Angels a semi-formal framework for measuring progress and offering their guidance in the "search" for a business model. It turns ad hoc startups into strategy-driven startups.

2) Asynchronous Updates. Interaction with advisors and board members can now be decoupled from the – once every six weeks, "big event" – board meeting. Now, as soon as the founders post an update, everyone is notified. Comments, help, suggestions and conversation can happen 24/7. For startups with formal boards, it makes it easy to implement, track, and follow-up board meeting outcomes.

Monitoring and guiding a small angel investment no longer requires the calculus to decide whether the investment is worth a board commitment. It potentially encourages investors who would invest only if they had more visibility but where the small number of dollars doesn't justify the time commitment.

A board as bits ends the repetition of multiple investor coffees. It's highly time-efficient for investor and founder alike.

3) Coaching. This approach allows real-time monitoring of a startup's progress and zero-lag for coaching and course-correction. It's not just a way to see how they're doing. It also provides visibility for a deep look at their data over time and facilitates delivery of feedback and advice.

4) Geography. When the boardroom is bits, angel-funded startups can get experienced advice – independent of geography. An angel investor or VC can multiply their reach and/or depth. In the process it reduces some of the constraints of distance as a barrier to investment.

Imagine if a VC took $4 million (an average Series A investment) and instead spread it across 40 deals at $100K each in a city with a great outward-facing technology university outside of Silicon Valley. In the past they had no way to monitor and manage these investments. Now they can. The result – an instant technology cluster – with equity at a fraction of Silicon Valley prices. It might be possible to create Virtual Valley Ventures.

We Ran the Experiment

At Stanford our Lean Launchpad class ran an experiment that showed when "the boardroom is bits" can make a radical difference in the outcome of an early stage startup.

Our students used Customer Development as the process to search for a business model. The used a blog to record their customer learning, and their progress and issues. The blog became a narrative of the search by posting customer interviews, surveys, videos, and prototypes. They used the Business Model Canvas as a scorekeeping device to chart their progress. The result invited comment from their "board" of the teaching team.

Here are some examples of how rich the interaction can become when a management team embraces the approach.

We were able to give them near real-time feedback as they posted their results. If we had been a board rather than a teaching team we would have added physical reality checks with Skype and/or face-to-face meetings.

We were able to give them near real-time feedback as they posted their results. If we had been a board rather than a teaching team we would have added physical reality checks with Skype and/or face-to-face meetings.

Show Me the Money

While this worked in the classroom, would it work in the real world? I thought this idea was crazy enough to bounce off a five experienced Silicon Valley VC's. I was surprised at the reaction – all of them want to experiment with it. Jon Feiber at MDV is going to try investing in startups emerging from Universities with great engineering schools outside of Silicon Valley that have entrepreneurship programs, but minimal venture capital infrastructure. (The University of Michigan is a possible first test.) Kathryn Gould of Foundation Capital and Ann Miura-Ko of Floodgate also want to try it.

Shawn Carolan of Menlo Ventures not only thought the idea had merit but seed-funded the LeanLaunchLab, a startup building software to automate and structure this process. (More than 700 startups signed up for the LeanLaunchLab software the day it was first demo'd.) Other entrepreneurs think this is an idea whose time has come and are also building software to manage this process including Alexander Osterwalder, Groupiter, and Angelsoft. Citrix thought this was such a good idea that their Startup Accelerator has offered to provide GoToMeeting and GoToMeeting HD Faces free to participating VC's and startups. Contact them here.

Summary

For startups with traditional boards, I am not suggesting replacing the board meeting – just augmenting it with a more formal, interactive and responsive structure to help guide the search for the business model. There's immense value in face-to-face interaction. You can't replace body language.

But for Angel-funded companies I am proposing that a "board meeting in bits" can dramatically change the odds of success. Not only does this approach provide a way for founders to "show your work" to potential and current investors and advisors, but also it helps expand opportunities to attract investors from outside the local area.

Lessons Learned

Startups are a search for a business model

Startups can share their progress/get feedback in the search

Weekly blog of the customer development narrative

Weekly summary of the business model canvas

Interactive comments and questions

Skype and face-to-face when needed

This may be a way to augment traditional board meetings

This might be a way to rethink our notion of geography as a barrier to investments

Or watch the video here.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Teaching, Venture Capital

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers