Steve Blank's Blog, page 49

January 4, 2012

Why The Movie Industry Can't Innovate and the Result is SOPA

This year the movie industry made $30 billion (1/3 in the U.S.) from box-office revenue.

But the total movie industry revenue was $87 billion. Where did the other $57 billion come from?

From sources that the studios at one time claimed would put them out of business: Pay-per view TV, cable and satellite channels, video rentals, DVD sales, online subscriptions and digital downloads.

The Movie Industry and Technology Progress

The music and movie business has been consistently wrong in its claims that new platforms and channels would be the end of its businesses. In each case, the new technology produced a new market far larger than the impact it had on the existing market.

1920's – the record business complained about radio. The argument was because radio is free, you can't compete with free. No one was ever going to buy music again.

1940's – movie studios had to divest their distribution channel – they owned over 50% of the movie theaters in the U.S. "It's all over," complained the studios. In fact, the number of screens went from 17,000 in 1948 to 38,000 today.

1950's – broadcast television was free; the threat was cable television. Studios argued that their free TV content couldn't compete with paid.

1970's – Video Cassette Recorders (VCR's) were going to be the end of the movie business. The movie businesses and its lobbying arm MPAA fought it with "end of the world" hyperbola. The reality? After the VCR was introduced, studio revenues took off like a rocket. With a new channel of distribution, home movie rentals surpassed movie theater tickets.

1998 – the MPAA got congress to pass the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), making it illegal for you to make a digital copy of a DVD that you actually purchased.

2000 – Digital Video Recorders (DVR) like TiVo allowing consumer to skip commercials was going to be the end of the TV business. DVR's reignite interest in TV.

2006 - broadcasters sued Cablevision (and lost) to prevent the launch of a cloud-based DVR to its customers.

Today it's the Internet that's going to put the studios out of business. Sound familiar?

Why was the movie industry consistently wrong? And why do they continue to fight new technology?

Technology Innovation

Technology Innovation

The movie industry was born with a single technical standard – 35mm film, and for decades had a single way to distribute its content – movie theaters (which until 1948 the studios owned.) It was 75 years until studios had to deal with technology changing their platform and distribution channel. And when it happened (cable, VCR's, DVD's, DVR's, the Internet,) it was a relentless onslaught. The studios responded by trying to shut down the new technology and/or distribution channels through legislation and the courts.

Regulation/Legislation

But why does the movie business think their solution is in Washington and legislation?

History and success.

In the 1920's individual states were beginning to censor movies and the federal government was threatening to do so as well. The studios set up their own self censorship and rating system keeping most sex and politics off the screen for 40 years. Never again wanting to be at the losing side of a political battle they created the movie industry's lobbying arm, MPAA.

By the 1960's, the MPPA achieved regulatory capture (where an industry co-opts the very people who are regulating it,) when they hired Jack Valenti, who ran the studios' lobbying efforts for the next 38-years. Ironically, it was Valenti's skill in hobbling competitive innovation that negated any need for studios to develop agility, vision and technology leadership.

Management of Innovation

The introduction of new technology is always disruptive to existing markets, particularly to content/copyright owners whose sell through well-established distribution channels. The incumbents tend to have short-sighted goals and often fail to recognize that more money can be made on new platforms and new distribution channels.

In an industry facing constant technology shifts the exec staff and boards of the studios have lawyers, MBAs and financial managers, but no management skill in dealing with disruption. So they rely on lobbying ($110 million a year,) lawsuits, campaign contributions (wonder why the President won't be vetoing SOPA?) and Public Relations.

Ironically, the six major movie studios have a great technology lab in Silicon Valley with projects in streaming rights, Video On Demand, Ultraviolet, etc. But lacking the support from the studio CEOs or boards, the lab languishes in the backwaters of the studios' strategy. Instead of leading with new technology, the studios lead with litigation, legislation and lobbying. (Imagine if the $110 million/year spent on lobbying went to disruptive innovation.)

Piracy

One of the claims that studios make is that they need legislation to stop piracy. The fact is piracy is rampant in all forms of commerce. Video games and software have been targets since their inception. Grocery and retail stores euphemistically call it shrinkage. Credit card companies call it fraud. But none use regulation as often as the movie studios to solve a business problem. And none are so willing to do collateral damage to other innovative industries (VCRs, DVRs, cloud storage and now the Internet itself.)

The studios don't even pretend that this legislation benefits consumers. It's all about protecting short-term profit.

SOPA

When lawyers, MBAs and financial managers run your industry and your lobbyists are ex-Senators, understanding technology and innovation is not one of your core capabilities.

The SOPA bill (and DNS blocking) is what happens when someone with the title of anti-piracy or copyright lawyer has greater clout than your head of new technology. SOPA gives corporations unprecedented power to censor almost any site on the Internet.

History has shown that time and market forces provide equilibrium in balancing interests, whether the new technology is a video recorder, a personal computer, an MP3 player or now the Net. It's prudent for courts and congress to exercise caution before restructuring liability theories for the purpose of addressing specific market abuses, despite their apparent present magnitude.

What the music and movie industry should be doing in Washington is promoting legislation to adapt copyright law to new technology — and then leading the transition to the new platforms.

The U.S. State Department has been championing the Internet Freedom initiative across the world. Secretary of State Clinton said, "…when ideas are blocked, information deleted, conversations stifled, and people constrained in their choices, the Internet is diminished for all of us."

It's too bad the head of the MPAA – an ex Senator - made a mockery of her words when he wondered "why our online censorship can't be like China?"

We wonder, "Why can't the film industry innovate like Silicon Valley?"

Lessons Learned

Studios are run by financial managers who lack the skills to exploit disruptive innovation

Studio anti-piracy/copyright lawyers trump their technologists

Studios have no concern about collateral damage as long as it optimizes their revenue

Studios $110M/year lobbying and political donations trump consumer objections

Politicians votes will follow the money unless it will cost them an election

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development

December 27, 2011

American Entrepreneur Radio Interview

I was lucky enough to get interviewed by Rob Morris of American Entrepreneur Radio.

Ron Morris has a great "radio voice," and actually seemed to understand what the heck I was talking about. It made for a fun interview.

Click here to listen to the interview: Steve Blank American Entrepreneur Radio interview

The following week Ron Morris interviewed Regis McKenna, who for decades was the "gold standard" for high tech Public Relations in Silicon Valley. Click here to listen to the Regis interview.

.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development

December 22, 2011

The National Science Foundation Innovation Corps – Class 2: The Business Model Canvas

The Lean LaunchPad class for the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps is a new model of teaching startup entrepreneurship. This post is part two. Part one is here. Syllabus here.

The 21 NSF teams had been out of the classroom for just 15 hours as they filed back in with their business model canvas presentations. Their assignment appeared (to them) to be deceptively simple:

Write down their initial hypotheses for the 9 components of their company's business model (who are the customers? what's the product? what distribution channel? etc.)

Come up with ways to test each of the 9 business model canvas hypotheses

Decide what constitutes a pass/fail signal for the test. At what point would you say that your hypotheses wasn't even close to correct?

Consider if their business worth pursuing? (Give us an estimate of market size)

Start their team's blog/wiki/journal to record their progress during for the class

Teaching logistics

Each week every team presented a 5-minute summary of what they had done and what they learned that week. As each team presented, the teaching team would ask questions and give suggestions (at times direct, blunt and pointed) for things the students missed or might want to consider next week.

While the last sentence is short, it's one of the key elements that made the class effective. Between the three of us on the teaching team there was 75 years of entrepreneurial experience. (The 2 VC's between them probably have seen 1000′s of presentations.) While there's no guarantee our comments were correct or we had any unique insight, we did have enough data for pattern recognition.

The instructors sat in the back of the room and used a shared Google spreadsheet for grading. We graded the teams on a scale of 1-10 and each of us left detailed comments the other teaching team members could share and comment on. Week after week it gave us a pretty detailed record of the progress and trajectory of each team.

(As great as the presentations may be, sitting through 21 of them in a row were exhausting. After this first cohort, the NSF will be putting 25 teams at a time in a class. We intend to break the group into three parallel presentation sections.)

All teams kept a blog – almost like a diary – to record everything they did outside the building. This let the teaching team keep tabs on their progress and offer advice in-between class sessions.

Getting the teams to blog required constant "encouragement," but it was invaluable. First, as we had a window into each teams engagement with customers, it eliminated most of the surprises when they came into class to present. Second, the blog helped us see if they were gaining insight from their customer discovery. Insight is what enables entrepreneurs to iterate and pivot their business model. The goal wasn't just to talk to lots of people – the goal was to learn from them. Finally, their blogs gave us and them a permanent record of who they talked to. Over time this contextual contact list will be turned into a shared contact database for all future NSF teams.

The 21 Teams Present

The first team up was Arka Lighting. We liked these guys, but for a while no one on the teaching team could figure out what their core technology was. We knew they wanted to make LED lights that had better performance because they would dissipate less heat. Finally when we understood that their core technology was heat pipes, it wasn't clear why that made them a better LED supplier. Were they selling to end users? OEMs? Manufacturers? We suggested that perhaps they had jumped to too many assumptions.

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

Next up was SenSevere – solid-state hydrogen and hydrocarbon sensors for use in severe environments. They were going to start with the $81M Chlorine market where they already had a partner. It seemed like a tiny business. Did they just want to become a licenser of technology? Were their other severe environments that their sensors fit into? Did customers just want the sensors or a more complete sensing solution?

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

Graphene Frontiers was next. Graphene is incredibly cool. It's touted as the new "wonder material" and its inventors won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. The team wanted to make wafer-scale Graphene films. And do it at ambient pressure. But their proposed products seemed like research lab selling other research labs low volume products. It seemed liked technology in search of a business. Reading the Graphene Frontiers blog for the first week, we realized that in a burst of enthusiasm they set up a Google AdWords campaign to drive traffic to their site!

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

Ground Flour Pharma was going to take Fluorine-18 and make a new generation of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) radiotracers for Positron emission tomography scanners. But it wasn't clear who benefits enough to make this a business. If they need FDA trials is it worth the money needed for approval? Is this just a technology license or is it a company?

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

C6 Systems had a great set of photos with things on fire in the woods. It seemed like they were going to burn downed trees to do what? Make charcoal? It looked like fun but is this a hobby or a scalable business? Is their any patentable Intellectual Property? What was their Value Chain? Their blog showed a good head-start on talking to customers.

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

Photocatalyst made nanogrids that became miniaturized self-supported mats, similar to fishing nets, that float on water and rapidly decompose crude oil using sunlight. The result is that pollutants are turned into water, carbon dioxide and other biodegradable organics for environmental remediation. Their slides sounded like a technical presentation of nanocatalyst features but their blog showed that they had been actively talking to customers in the last two days.

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

After the teams presented it was the turn of the teaching team. We presented our second lecture, this time on "Value Proposition."

If you can't see the slide deck above, click here

For tomorrow, the teams had 15-hours to get out of the building and talk to 10-15 customers and test their Value Proposition.

While most of the teams got on the phone or into their cars, a couple of others complained, "You didn't tell us we were supposed to use our spare time to talk to customers. We thought this was just spare time."

At first, I thought they were joking. Spare time? I don't think you understand the key principle in a startup – there is no such thing as spare time. The clock is running and you're burning cash.

Go!

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

December 20, 2011

The Government Starts an Incubator: The National Science Foundation Innovation Corps

Over the last two months the U.S. government has been running one of the most audacious experiments in entrepreneurship since World War II.

They launched an incubator for the top scientists and engineers in the U.S.

This week we saw the results.

63 scientists and engineers in 21 teams made 2,000 customer calls in 8 weeks, turning laboratory ideas into formidable startups. 19 of the 21 teams are moving forward in commercializing their technology.

It was an extraordinary effort.

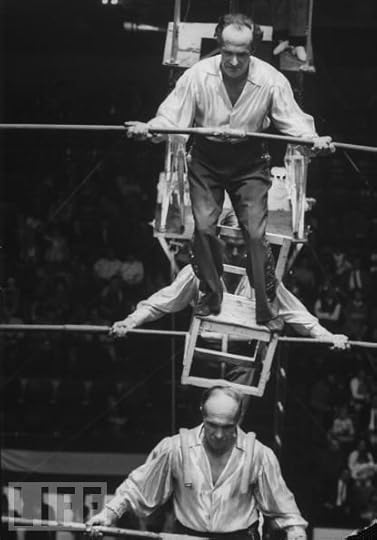

Your Country Needs You

Your Country Needs You

In July I got a call from Errol Arkilic, a program manager at the National Science Foundation (NSF), the $6.8-billion U.S. government agency that supports research in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. "We've been reading your blog about your Lean Launchpad class." Wow, that's nice, I thought, a call from a fan. No, the conversation was about to get more interesting.

"Our country needs you." Say what? "Part of the NSF charter is to commercialize the best of the science and engineering research we fund. We want to make a bet that your Lean Launchpad class can apply the scientific method to market-opportunity identification. We think your class can train scientists to start companies better than how we're doing it now." Uh oh, where's this heading? "We want to select the best of our researchers, pay them $50,000 to take your class and see if we can change the outcome of their careers and their research."

"That's great, maybe I can set up a class for you next year," I replied. The answer shot back, "We want the class to start in 90 days,"

I remember thinking, "Wow, whoever's on the other end of phone sounds just like an entrepreneur, they were asking for the impossible." Just as I was computing whether this was possible, he added, "And we want to bring 25 new teams every quarter."

So of course, I said yes.

While they'll never admit it, the National Science Foundation was starting an incubator – the Innovation Corps – to take the most promising research projects in American university laboratories and turn them into startups.

The Innovation Corps – Using the Lean LaunchPad as an Incubator for Scientists and Engineers

The Innovation Corps Startup Team

These weren't 22-year olds who wanted to build a social shopping web site. Each of the teams selected by the NSF had a Principal Investigator – a research scientist who was a University professor; an Entrepreneurial Lead – a graduate student working in the Investigator's lab; and a mentor from their local area who had business and/or domain expertise. And they were hard at work at some real science.

The I-Corps Incubator Program

Unlike other incubators, our Lean LaunchPad Class had a specific curriculum. We taught them the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack. This methodology forces rapid hypothesis testing and Customer Development by getting out of the building while building the product. (The mentors in our program are there to support the methodology, but aren't there to tell stories.)

The gamble was that we could train Professors doing hard-core science, who had never been near a startup or Silicon Valley, to get out of the building and talk to customers and Pivot as easily as someone at a web startup.

The Scientists, the NSF and the teaching team were all going to go where no one had before.

Given that Silicon Valley had started with scientists and engineers not MBA's, I thought this was a bet worth making.

The Curriculum

Since the teams were in Universities scattered across the U.S., we couldn't keep them in Silicon Valley for all 8 weeks, so we tried an experiment in teaching remotely.

First, we brought all 21 teams to Stanford for 3-days of 10 hour-a-day classes in business model design and customer development. After returning to their schools, they got out of their labs while they built their products. Once a week, via Webex,they presented their Customer Development progress on line to the teaching team and the other teams. Then it was our turn, and we lectured all the teams remotely. After 7 weeks they returned to Silicon Valley for their final presentations.

(The class syllabus is here. The class textbooks were "The Four Steps to the Epiphany and Business Model Generation.")

Assembling the Teaching Team

We recruited two veteran Venture Capital partners to be part of the 10-week teaching team: Jon Feiber, at Mohr Davidow and John Burke of True Ventures. Alexander Osterwalder joined us for the opening day, and Oren Jacob, ex-CTO of Pixar joined us for a finale.

The First Class

As the first class settled into their seats at Stanford I wondered if we were going to be able to get them to act like startups. Most of the Principal Investigators were professors. Some had their own labs managing large groups of researchers. Their average age was in the mid-40's. Their mentors were at least that old. Only the Entrepreneurial Leads (the PI's assistants) were in their mid to late 20's.

Looking at them I wondered if: 1) hard-core science and engineering projects could rapidly pivot, 2) if the Principal Investigators would simply "assign" the work to their graduate students. I thought about the common wisdom that only 20-year olds doing Internet startups could be agile. Some incubators would have labeled this group too old to be entrepreneurs. I smiled as I realized that I was older than most (but not all) of them.

The Stanford Lectures

Our first lecture was about 1) how to organize their thinking of what it takes to build a startup – the business model canvas and 2) how to test their hypotheses – the Customer Development Process.

Since the first part of the lecture was about Alexander Osterwalder's Business Model Canvas, Osterwalder flew in from Switzerland to teach slides 20-76. And since the rest of the slides were about Customer Development, I taught those.

The homework for the 21 teams in the next 24-hours? Come up with a business model canvas for their startup. And tell us how they will test each of their business model hypotheses.

As day one ended, I wondered what those canvases would look like.

Stay tuned for Part 2.

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

December 13, 2011

The Startup Team

Individuals play the game, but teams beat the odds

SEAL Team saying

Over the last 40 years Technology investors have learned that the success of startups are not just about the technology but "it's about the team."

We spent a year screwing it up in our Lean LaunchPad classes until we figured out it was about having the right team.

Startup Team Lessons Learned

During the last 12 months we've taught 42 entrepreneurial teams with 147 students at Stanford, Berkeley, Columbia and the National Science Foundation. (As many teams as most startup incubators.)

Get into the Class

When I first started teaching hands-on, project/team entrepreneurship classes we'd take anyone who would apply. After awhile it became clear that by not providing an interview process we were doing these students a disservice. A good number of them just wanted an overview of what a startup was like – an entrepreneurial appreciation class (and we offer some great ones.) But some of our students hadn't yet developed a passion for entrepreneurship and had no burning idea that they wanted to bring to market. Yet in class they'd be thrown into a "made-up in the first week" startup team and got dragged along as a spear-carrier for someone else's vision.

Step One – Set a Bar So as a first step we made students formally apply and interview for the Lean LaunchPad class. We were looking for entrepreneurs who had great ideas and interest in making those ideas really happen. We'd hold mixers before the first class and the students would form their teams during week one of the class.

So as a first step we made students formally apply and interview for the Lean LaunchPad class. We were looking for entrepreneurs who had great ideas and interest in making those ideas really happen. We'd hold mixers before the first class and the students would form their teams during week one of the class.

But we found we were wasting a week or more as the teams formed and their ideas gelled.

Step Two – Apply As A Team

So next time we taught, we had the students apply to the class as a team. We hold information sessions a month or more before the classes. Here students with preformed teams could come and have an interview with the teaching team and get admitted. Or those looking to find other students to join their team could mix and market their ideas or join others and then interview for a spot. This process moved the team logistics out of class time and provided us with more time for teaching.

But we had been selecting teams for admission on the basis of whether they had the best ideas. We should have known better. In the classroom, as in startups, the best ideas in the hands of a B team is worse than a B idea in the hands of a world class team.

Here's why.

Step Three – Hacker/Hardware, Hustler, Designer, Visionary

As we taught our Lean LaunchPad classes we painfully relearned the lesson that team composition matters as much or more than the product idea. And that teams matter as much in entrepreneurial classes as they do in startups.

In a perfect world you build your vision and your customers would run to buy your first product exactly as you spec'd and built it. We now know that this 'build it and they will come" is a prayer rather than a business strategy. In reality, a startup is a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model. This means the brilliant idea you started with will change as you iterate and pivot your business model until you find product/market fit.

The above paragraph is worth reading a few times.

It basically says that a startup team needs to be capable of making sudden and rapid shifts – because it will be wrong a lot. Startups are inherently chaos. Conditions on the ground will change so rapidly that the original well-thought-out business plan becomes irrelevant.

And finding product/market fit in that chaos requires a team with a combination of skills.

What skills? Well it depends on the industry you're in, but generally great technology skills (hacking/hardware/science) great hustling skills (to search for the business model, customers and market,) great user facing design (if you're a web/mobile app,) and by having long term vision and product sense. Most people are good at one or maybe two of these, but it's extremely rare to find someone who can wear all the hats.

It's this combination of skills is why most startups are founded by a team, not just one person.

University Silos

While building these teams are hard in the real world, imagine how hard it is in a university with classes organized as silos. Business School classes were only open to business school students, Engineering School classes were only open to engineering school students, etc. No classes could be cross-listed. This meant that you couldn't offer students an accurate simulation of what a startup team would look like. (In our business school classes we had students with great ideas but lacking the technical skills to implement it. And some of our engineering teams could have benefited from a role-model to follow as a hustler.)

So the next time we taught, we managed to ensure that the class was cross-listed and that the student teams had to have a mix of both business and engineering backgrounds.

I think we've finally got the team composition right – relearning all the lessons investors already knew.

But now on to the next goal – getting our mentor program correct.

Lessons Learned

Finding product/market fit in startup chaos requires a team with a combination of skills

Hacker/Hardware, Hustler, Designer, Visionary

At times an A+ market (huge demand, unmet need) may trump all

Getting the Mentors right is the next step

Filed under: Customer Development, Family/Career/Culture, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

November 30, 2011

You'll Be Dead Soon – Carpe Diem

Remembering that I'll be dead soon is the most important tool I've ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Because almost everything – all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure – these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important.

Watching an entrepreneur fail is sad, but watching but watching them fail from a lack of nerve is tragic.

Excitement

At the beginning of this year Bob, one of my ex-students was in entrepreneurial heaven. He had an idea for a new class of enterprise software insight-as-a-service based on big data web analytics as a Cloud/SaaS (Software As a Service) application.

Bob had taken to heart the business model canvas and Customer Development lessons. After graduating he put together a prototype and had quickly marched through Customer Discovery, iterating his product with the help of CIOs and Fortune 1000 IT departments.

I had made one of the introductions to a Fortune 100 CIO's so I got to hear his progress from both him and the CIO.

Takeoff

After 90 days, things seemed to be moving at startup speed. Bob had a backlog of users wanting to try his application, and the corporate IT people who were trying his early prototype said, "It's crude, we hate the user interface, it's missing lots of features – but we'll kill you if you try to take it away from us."

I pointed a VC who followed the space to the CIO who was testing the prototype. The VC told me the CIO wouldn't get off the phone. He kept telling him he couldn't remember when he had seen an enterprise software product with so much promise. The VC checked with other IT users and heard the same reaction. It was a "gotta use it, don't take it away, we'll have to buy it" product. After a demo and lunch, the VC (who normally did later stage deals) wrote my ex student a check for a seed round.

Life couldn't be better.

I followed Bob progress in bits and pieces from updates from the CIO, the VC and his emails and blogs. He seemed to be on the fast track to startup success. But pretty soon a few worrying warning signs appeared.

The first thing that I noticed was that Bob couldn't seem to find a co-founder. I wasn't close enough to know if he wasn't really looking for one, but given the early success he was having, it seemed a bit odd. But the next thing really got me concerned. Bob started hiring second rate developers. At best they were B- players.

Stall

A month went by, and the product stopped getting better. The U/I still sucked, and new features had stopped appearing. The next month, the same thing. I got a call from my CIO friend asking, "what was going on?" He said, "It was a great prototype, we would have loved to deploy it company-wide, and I hate to let it go, but it looks like Bob company just lost interest in developing it. I'm going to dump it and look for a substitute." So I called Bob and suggested we grab a coffee.

I asked him how things were going and got the update on how the earlyvangelists were using the product. As I had heard, they were ecstatic. But Bob said he was worried he hadn't found the right customer segment yet. "I'm not sure I can get all of these guys to pay me big bucks," he said. "That's why I stopped coding, and I'm spending all my time out in the field still talking to more customers." "What does your VC's say you ought to be doing?" I asked. "Oh, he hasn't had much time for me, his firm almost never does seed deals. It turns out I was an exception." Oh, oh.

The conversation was starting to make the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Bob had gotten to a place most founders never do – his product was a "gotta have it for people with big budgets." He should have been back rapidly coding, iterating and finding out what feature set would get him to paying customers.

Instead he had produced barely 3 weeks of progress in the last 5 months. His prototype was rapidly wearing out its welcome.

A Lack of Nerve

When I pressed Bob on this he admitted, "No I guess my engineers aren't very good. But I hired guys who were cheap because I wasn't sure if my hypotheses were right. Didn't you tell us to test our hypotheses first?" Now it was my time to be surprised. "Bob, you've validated your hypotheses better than any startup I've ever seen. You found that out in the first month. You got customers begging you to finish the product so they could buy it. You should have been hiring world-class talent and building something these CIO's will pay for. It's not too late. It's time to grab them by the throat and go for it."

I wasn't ready for the answer, "Steve, I've been reading all about premature scaling and making sure everything is right before I go for it. I want to be sure I get all of this right. I'm afraid I'll run out of money."

I thought I'd make one more run at it. "Bob," I said, "few entrepreneurs get the first time response you have from an early product. At your rate you're going to burn through your cash trying to get it perfect. It's a startup. You'll never have perfect information. You're sitting on a gold mine. Grab the opportunity!"

I got a blank stare.

We made some more small talk and shook hands as he left.

Bob was in the wrong business, not the wrong market. He wanted certainty, comfort and security.

I stared at my coffee for a long time.

Carpe Diem – make your lives extraordinary.

Lessons Learned

Yes, premature scaling is a cause of startup death

Yes, you need to get out of the building and test your hypotheses

But, when an opportunity smacks you in the head for gosh sake grab it with both hands and don't let go

If you can't, get out of the startup game

Filed under: Customer Development, Family/Career/Culture

November 15, 2011

Scientists Unleashed

Some men see things as they are and ask why.

Others dream things that never were and ask why not.

George Bernard Shaw

We're in the middle of our National Science Foundation Innovation Corps class – taking the most promising research projects in American university laboratories and teaching these scientists the basics of entrepreneurship. Our goal is to accelerate the commercialization of their inventions. Our Lean LaunchPad class teaches scientists and engineers that starting a company is another research project that can be solved by an iterative process of hypotheses testing and experimentation built around the business model / customer development / agile development solution stack. It's "the scientific method" applied to startups.

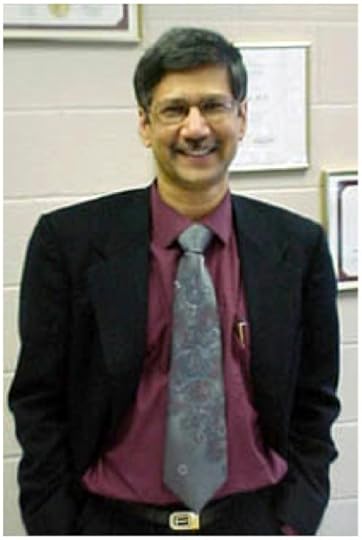

Although I typically don't write about a class while it's going on, I had to share this extraordinary reflection that Satish Kandlikar, one of the National Science Foundation principal investigators, posted to our Lean LaunchPad class blog.

Satish Kandlikar – The Spirit of Entrepreneurship Satish Kandlikar has been a professor in the mechanical engineering department at the Rochester Institute of Technology for the past twenty-one years. His research is focused in the areas of flow boiling, critical heat flux, contact line heat transfer, and advanced cooling techniques

Satish Kandlikar has been a professor in the mechanical engineering department at the Rochester Institute of Technology for the past twenty-one years. His research is focused in the areas of flow boiling, critical heat flux, contact line heat transfer, and advanced cooling techniques

His team, Akara Lighting, wants to build a device for LED lights that gets rid of heat 50% better than anything on the market. This would result in LED's having a higher performance at a reduced cost.

Here's what he had to say about his experience in the Lean LaunchPad class ….

"It is quite an eye-opening experience to transition from an academic "PI" (Principal Investigator) to someone who wants to run a technology start-up. The change in the mindset is perhaps the important factor on the path to success…

The teaching team is simply phenomenal in identifying the pitfalls in our path and guiding us in finding the solutions. They have shown us the other side of the equation from technology to market acceptability. We have been extremely fortunate in having this kind of guidance and support.

A key finding I would like to report is that we just had another "pivot" two days ago when our mentor brought to our attention that we can succeed as a heat pipe company providing thermal solutions to various LED products as well as other applications. I visited two companies, one providing data center cooling solutions, and other providing control panel cooling systems. Key alliances are expected to occur through these initial, very positive, contacts.

One fundamental change that I see in my approach going forward is that I am looking at the research in a totally different way. It is no longer, in my mind, a means to publishing papers and simply graduating students. It means now, to me, how the research can be applied to make products that are accepted in marketplace. Making students understand the entire process, to whatever extent I can influence them, and inspiring them to aspire for transferring their knowledge to products is becoming an important thrust in my classroom interactions.

Another eye-opener was on understanding communications. While making presentations in academic setting, it was more of a paper-based research with extension of knowledge, without too much understanding of its application. Knowing the audience was really not a factor. Now after making "cold-calls", and seeing that there is a certain way to get them interested in just a few opening sentences, was simply amazing. Knowing what their needs are is a crucial step.

Now it is becoming clear what Steve meant when he said, "get out of the building". It is clear that the building referred to our mindset more than the physical act of going out or simply contacting someone outside.

The purpose of this posting was to document my beginning of the transformation process from an academician to an entrepreneur. And I am definitely enjoying it."

Scientists Unleashed

Over fifty years ago Silicon Valley was born in an era of applied experimentation driven by scientists and engineers. Fifty years from now, we'll look back to this current decade as the beginning of another revolution, where scientific discoveries and technological breakthroughs were integrated into the fabric of society faster than they had ever been before, unleashing a new era for a new American economy built on entrepreneurship and innovation.

And scientists like Satish Kandlikar and the National Science Foundation will lead the way.

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development

November 1, 2011

Steel In Their Eyes – Why VC's Should Be Startup CEO's

A man who carries a cat by the tail learns something he can learn in no other way.

Mark Twain

Venture Capitalists who are serious about turning their firms into more than one-fund wonders may want to have their associates actually start and run a company for a year. Running a company is distinctly different from simply having operating experience – (working in bus dev, sales or marketing.) None of that can compare with being the CEO of a startup facing a rapidly diminishing bank account, your best engineer quitting, working until 10pm and rushing to the airport and catching a redeye for a "Hail Mary" close of a customer, with your board demanding you do it faster.

Today, you can start a web/mobile/cloud startup for $500,000 and have money left over. Every potential early-stage Venture Capitalist should take a year and do it before he or she makes partner.

Here's why.

——-

Venture capital as a profession is less than half a century old.

Over time Venture firms realized that the partners in the firms needs a variety of skills:

People skills (ability to recognize patterns of success in individuals and teams)

People skills

People skills

Market/technology acuity (patterns of success, domain expertise)

Rolodex/deal flow (deal sourcing/ability to make connections for the portfolio)

Board skills (Startup coaching, mentoring, strategy, operational/growth)

Fund raising skills

Some of these skills are learned in school (finance), some are innate aptitudes (people skills), some are learned pattern recognition skills (shadowing experienced partners, hard won success and failures of their own), and some are learned by having operating experience. But none of them are substitutes for having started and run a company.

How to Become a VC

Early-stage Venture Capital firms grow their partnerships in different ways, some hire:

partners from other firms

associates and put them on a long career path

venture/operating partners to get them into new industries

an executive who had startup "operating experience"

rarely a startup founder/CEO

In surveying my VC friends, I was surprised about the strong and diverse opinions. The feedback varied from:

".. because culture is such an important part of who we are, we will probably never hire a partner from another firm. The idea of bolting on someone from another firm is somewhat antithetical to who we are. We think that our venture partner role is the most likely path to general partner."

..we have a partner-track associates program. We want to find someone who has a lot of consumer internet product experience as either product manager, founder, VP Product, etc. with 3-7 years of experience."

"…we do not even try to train new partners. We bring people into our firm who have learned how to be VCs at the partner level somewhere else and have demonstrated their talent in boardrooms alongside of us. We completely and totally punt on the idea of "training a VC." It's an ugly and painful process and I don't want to be part of it."

"…if they don't have operating experience the odds of them knowing what they're talking about in a board meeting for the first five years is low.."

Carrying the Cat By The Tail

When I finally became a CEO it was after I had spent my career working my way up the ladder in marketing in startups. I did every low-level job there was, at times sleeping under my desk (engineering was doing the same.) By the time I was running a company, having some junior employee tell me why they couldn't do something because of "how hard it was" didn't get much sympathy from me. I knew how hard it was because I had done it myself. Startups are hard.

What running a company would do is give early-stage VC's a benchmark for reality, something most newly-minted partners sorely lack. They would learn how a founding CEO turns their money into a company which becomes a learning, execution and delivery engine. They would learn that a CEO does it through the people – the day-to-day of who is going to do what, how you hold people accountable, how teams communicate, and more importantly, who you hire, how you motivate and get people to accomplish the seemingly impossible. Further, they'd experience first hand how, in a startup, the devil is in the details of execution and deliverables.

My hypotheses is simple: what most VC's lack is not brains or rolodex or people skills – but hands-on experience as a startup CEO – knowing what it's like trying to make a payroll while finding sufficient customers while you're building the product. Sure, a year as a CEO won't make them an expert, but it will change them quicker than 10 years in the boardroom.

Does it Matter?

There's a school of thought that says the skill set of a great early-stage VC – awesome people skills, curiosity, likable, etc. – versus the attributes of a great entrepreneur – pattern recognition, tenacity, etc. may not have much overlap. Early stage investing is not a spreadheet, quantitative driven exercise, nor is it about technology – it is a deal business and people drive the deals. And while having experience as a startup CEO may make you a better board member, it may not substantively contribute to your career as an early stage investor – which depend on many more important skills.

Steel in their eyes

[image error]

Ten years ago starting a company required millions of dollars and first customer ship took years. Now it's possible to build a company, ship product and get tens of thousands of customers in a year with less than $500K. For venture firms who want to groom/grow associates or operating execs into partners (rather than hiring proven partners), here's my suggestion:

Have them start as an analyst (search for deal flow and people, due diligence)

Then take a year as a product manager in a startup in the firm's portfolio

Then come back as an associate for a year – shadowing board and partner meetings

Then take a year and $250-500K to start and run a mobile/web/cloud company. See what it's really like on the other side of that boardroom table

Then return as a partner

This process will create a new generation of venture capital partners, ones who have been battle tested in the trenches of a startup, hardened by hiring and firing, tempered by making a payroll and losing orders, and will never forget it's all about the people.

These VC's would return to their firms with steel in their eyes. They'd be relentless about accountability from board meeting to board meeting with laser like focus on the one or two issues that matter. They would understand the CEO-VC-board dynamic in a way that few who hadn't lived it could. They'd be ruthless in their choice of people and teams, looking for those few who have natural curiosity, a passion to win, and who won't take no for answer.

Lessons Learned

Venture Capital is still a "craft business"

Early stage VC's should have startup CEO experience

It can now be gained cheaply and quickly

It will give them perspective and edge that would take a decade to learn

Filed under: Venture Capital

October 20, 2011

How the iPhone Got Tail Fins – Part 2 of 2

Read part 1 of this post for background.

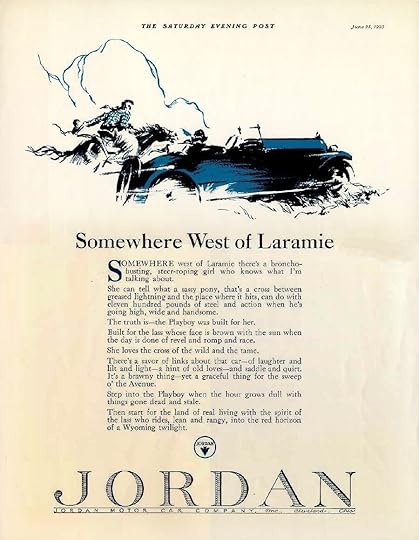

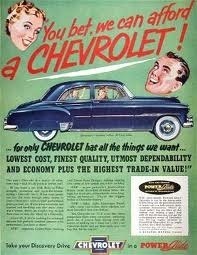

By the early 1920's General Motors realized that Ford, which was now selling the Model T for $290, had an unbeatable monopoly on low-cost automobile manufacturing. Other manufacturers had experimented with selling cars based on an image and brand. (The most notable was an ad by the Jordan Car company.) But General Motors was about to take consumer marketing of cars to an entirely new level.

Market Segmentation General Motors had turned the independent car companies acquired by its founder Billy Durant into product divisions. But in a stroke of genius GM transformed these divisions into a weapon that Ford couldn't match. With the rallying cry "a car for every purse and purpose," GM positioned its car divisions (Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac) so they would cover five price segments – from low-price to luxury. It targeted each of its brands (and models inside those brands) to a distinct economic segment of the population. Chevy was directly aimed at Ford – the volume car for the working masses. Pontiac came next, then Oldsmobile, then Buick. The top-of- the-line Cadillac offered luxury and prestige announcing you had finally arrived at the top of the conspicuous consumption heap. Consumers could announce their status and lives had improved by upgrading their brands.

GM had one more trick to make this happen. Within each brand, the top of the line was just a bit less expensive than the lowest priced model of the next expensive brand. The goal was to convince the consumer to spend a little more to trade up to a more prestigious brand.

Market segmentation by price was something no other automotive manufacturer had ever done. While other car companies could compete with one of GM's divisions, few had GM's capital and resources to compete simultaneously with the onslaught of car models from all five divisions.

Planned Obsolescence While market segmentation allowed GM to use its divisions to reach a wider market than Ford or Chrysler, this didn't solve the problem of market saturation. By the late 1920's, most everyone in the U.S. had a car. And cars lasted 6 to 8 years. Even worse, the market was now filled with used cars that provided even lower cost basic transportation. Sloan, the General Motors CEO, faced two seemingly unsolvable challenges:

How do you get consumers to abandon their perfectly fine cars and buy a new one?

How do you turn a product that competed on price and features into a need?

In another stroke of genius, GM invented the annual model change. Sloan borrowed this idea from fashion where styles changed every year and applied it to automobiles starting in the 1920s. General Motors would change the external appearance of cars every year. Sloan preferred to call it "dynamic obsolescence."

Styling and design became an integral part of GM's strategy. Sloan hired Harley Earl to set up GM's in-house styling staff. Earl would run it from 1927 to 1958.

Before Earl, cars were designed by in-house body-engineers who focused on practical issues like function, costs, features, etc. Each exterior component was designed separately to be functional – radiator, bumpers, hood, passenger compartment, etc. Some companies used 3rd party bodymakers to set the style , but GM was the first to take car design away from the engineers and give it to the stylists.

The concept of yearly "improvements", whether styling or incremental technology improvements, every model year gave GM an unbeatable edge in the market. (Henry Ford hated the idea. He had built Ford on economies of scale – the Ford Model T lasted for 19 years.) Smaller car makers could not afford the constant engineering and styling changes they had to make to keep competitive. GM would shut down all their manufacturing plants for a few months and literally rip out the tooling, jigs and dies in every plant and replace them with the equipment needed to make the next year's model.

[image error]

GM had figured out how to take a product which solved a problem – cheap transportation – and transform it into a need. It was marketing magic that wasn't to be equaled until the next century.

By the mid-1950′s every other car company was struggling to keep up.

Mass Marketing Starting in the 1920's and continuing for the next half century, automobile advertising hit its stride. Ads emphasized brand identification and appealed to consumers' hunger for prestige and status. Advertising agencies created catchy slogans and jingles, and celebrities endorsed their favorite brands. General Motors turned market segmentation and the annual model year changeovers into national events. As the press speculated about new features, the company's added to the mystique by guarding the new designs with military secrecy. Consumers counted the days until the new models were "unveiled" at their dealers.

Results

For fifty years, until the Japanese imports of the 1970's, Americans talked about the brand and model year of your car – was it a '58 Chevy, '65 Mustang, or 58 Eldorado? Each had its particular cachet, status and admirers. People had heated arguments about who made the best brand.

The car had become part of your personal identity while it became a symbol of 20th Century America.

After Sloan took over General Motors its share of U.S cars sold skyrocketed from 12 per cent in 1920, until it passed Ford in 1930, and when Sloan retired as GM's CEO in 1956 half the cars sold in the U.S. were made by GM. It would keep that 50% share for another 10 years. (Today GM's share of cars total sold in the U.S. has declined to 19%.)

How the iPhone Got Tail Fins

Over the last five years Apple has adopted the GM playbook from the 1920′s – take a product, which originally solved a problem – cheap communication – and turn it into a need.

In doing so Apple did to Nokia and RIM what General Motors did to Ford. In both cases, innovation in marketing completely negated these firms' strengths in reducing costs. The iPhone transformed the cell phone from a device for cheap communication into a touchstone about the user's image. Just like cars in the 20th century, the iPhone connected with its customers emotionally and viscerally as it became a symbol of who you are.

—-

The desire to line up to buy the newest iPhone when your old one works just fine was just one more part of Steve Jobs' genius – it's how the iPhone got tail fins.

It's one more reason why Steve Jobs will be remembered as the 21st century version of Alfred P. Sloan.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Technology

October 18, 2011

How the iPhone Got Tail Fins – Part 1 of 2

It was the most advanced consumer product of the century. The industry started with its innovators located in different cities over a wide region. But within 20 years it would be concentrated in a single entrepreneurial startup cluster. At first it was a craft business, then it was driven by relentless technology innovation and then a price war as economies of scale drove efficiencies in production. When the market was finally saturated the industry reinvented itself again – one company discovered how to turn commodity products into "needs."

They opened retail outlets across the country and figured out how to convince consumers to flock to buy the newest "gotta have it" version and abandon the perfectly functional last year's model.

No, it's not Apple and the iPhone.

It was General Motors and the auto industry.

In the Beginning

At the beginning of the 20th century the auto industry was still a small hand-crafted manufacturing business. Cars were assembled from outsourced components by crews of skilled mechanics and unskilled helpers. They were sold at high prices and profits through nonexclusive distributors for cash on delivery. But by 1901, Ransom Olds invented the basic concept of the assembly line and in the next decade was quickly followed by other innovators who opened large scale manufacturing plants in Detroit – Henry Packard, Henry Leland's Cadillac, and Henry Ford with the Model A.

The Detroit area quickly became the place to be if you were making cars, parts for cars, or were a skilled machinist. By 1913 Ford's first conveyor belt-driven moving assembly line and standardized interchangeable parts forever cemented Detroit as the home of 20th century auto manufacturing.

Feature Wars

The automobile industry was founded and run by technologists: Henry Ford, James Packard, Charles Kettering, Henry Leland, the Dodge Brothers, Ransom Olds. The first twenty-five years of the century were a blur of technology innovation – moving assembly line, steel bodies, quick dry paint, electric starters, etc. These men built a product that solved a problem – private transportation first for the elite, and then (Ford's inspiration) – transportation for the masses.

Market Saturation

Ford tried to escape the never-ending technology feature wars by becoming the low cost manufacturer. Fords River Rouge manufacturing complex – 93 buildings in a 1 by 1.5 mile manufacturing complex, with 100,000 workers – vertically integrated and optimized mass production.

[image error]

By 1923, through a series of continuous process improvements, Ford had used the cost advantages of economies of scale to drive down the price of the Model T automobile to $290.

When the 1920's began there were close to a 100 car manufacturers, but the relentless drive for low cost production forced most of them out of business as they lacked capital to scale. For a brief moment, half the cars in the world were now Fords. To make matters worse, the long service life of Ford and GM cars (8 years for Fords Model T, 6 years for everyone else) retarded sales of new cars. In 20 years, U.S. car ownership had risen from 0 to 80% of American families – the market was approaching saturation.

Now cars would have to be sold almost entirely to people who already owned a car.

The Crazy Entrepreneur

After success as a leading manufacturer of horse-drawn carriages, Billy Durant was one of the few who saw the writing on the wall and got into the car business.[image error] Although he wasn't a technologist, he was an entrepreneur with a great eye for acquiring car companies run by technologists. His keen insight was that several carmakers combined under one company umbrella would have more growth potential than one brand on its own. Like most founders, he was great at searching for a business model but terrible at in large company execution. When his board fired him, Durant bought a competing company called Chevrolet, built it larger than his last company, and used Chevy stock to buy out his old company – General Motors – and threw out the board. Yet a few years later under his brilliant but reckless leadership GM was again on the brink of financial disaster and his new board fired him. (Durant would die penniless managing a bowling alley.)

Durant's ultimate replacement – an accountant named Alfred P. Sloan – would turn GM into the leading and most admired company in the U.S.

Relentless

Over the next decade Sloan would implement a series of innovations which would last for over half a century. And catapult General Motors from the number 2 car company (with a ¼ of Ford's sales) into the market leader for the next 100 years. Here's what he did:

Distributed Accounting Unlike Ford, GM was originally a collection of separate companies. Distributed Accounting turned those fiefdoms into product divisions each of which, could be focused like Ford's mass-produced lines. But Sloan went further. He figured out how to centralize financial oversight of decentralized product lines. His CFO created standardized division sales reports and flexible accounting, and allocated resources and bonuses to the GM divisions by a uniform set of rules. It allowed GM to be ruthlessly efficient internally as well with its dealers and suppliers. It got the division general managers to fall in line with corporate goals but allowed them to run their divisions freely. GM became the prototype of the modern multidivisional company.[image error]

Car Financing. Realizing that Ford would only accept cash for car purchases, in 1919 GM formed GMAC to provide new car buyers a way to finance their purchases through debt.

Consumer Research. Every since his days at Hyatt Roller Bearing, Sloan, and by extension GM, was relentless about getting out of the building – they had an entire department that studied consumers, dealers, suppliers. More importantly, Sloan led by example. He visited dealers and suppliers, listened to customers and was tied tightly to his head of R&D Charles Kettering.

All this would have made General Motors a well-run and well-managed company. But what they did next would make them the dominant company in the U.S. and eventually put tail-fins on the iPhone.

Part 2 explains it all.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Technology

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers