Steve Blank's Blog, page 46

October 17, 2012

How to Get a VC Meeting – the flowchart

I often get asked, “how do I get a meeting with a VC?” Here is my slightly tongue-in-cheek view.

Filed under: Customer Development, Venture Capital

October 8, 2012

Startup Communities – Building Regional Clusters

How to build regional entrepreneurial communities has just gotten it’s first “here’s how to do it” book. Brad Feld’s new book Startup Communities joins the two other “must reads,” (Regional Advantage and Startup Nation) and one “must view” (The Secret History of Silicon Valley) for anyone trying to understand the components of a regional cluster.

There’s probably no one more qualified to write this book then Brad Feld (startup founder, co founder of two VC firms – Mobius and Foundry, and founder of TechStars.)

Leaders and Feeders

Feld’s thesis is that unlike the common wisdom, it is entrepreneurs that lead a startup community while everyone else feeds the community.

Feld describes the characteristics of those who want to be regional Entrepreneurial Leaders; they need to be committed to their region for the long term (20+ years), the community and its leaders must be inclusive, play a non-zero sum game, be mentorship-driven and be comfortable experimenting and failing fast.

Feeders include the government, universities, investors, mentors, service providers and large companies. He points out that some of these, government, universities and investors think of themselves as the leaders and Feld’s thesis is that we’ve gotten it wrong for decades.

This is a huge insight, a big idea and a fresh way to view and build a regional ecosystem in the 21st century. It may even be right.

Activities and Events

One of the most surprising (to me) was the observation that a regional community must have continual activities and events to engage all participants. Using Boulder Colorado as an example, (Feld’s home town) this small entrepreneurial community runs office hours, Boulder Denver Tech Meetup, Boulder Open Coffee Club, Ignite Boulder, Boulder Beta, Boulder Startup Digest, Startup Weekend events, CU New Venture Challenge, Boulder Startup Week, Young Entrepreneurs Organization and the Entrepreneurs Foundation of Colorado. For a city of 100,000 (in a metro area of just 300,000 people) the list of activities/events in Boulder takes your breath away. They are not run by the government or any single organization. These are all grassroots efforts by entrepreneurial leaders. These events are a good proxy for the health and depth of a startup community.

Incubators and Accelerators

One of the best definitions in the book is when Feld articulates the difference between an incubator and an accelerator. An incubator provides year-round physical space, infrastructure and advice in exchange for a fee (often in equity.) They are typically non-profit, attached to a university (or in some locations a local government.) For some incubators, entrepreneurs can stay as long as they want. There is no guaranteed funding. In contrast, an accelerator has cohorts going through a program of a set length, with funding typically provided at the end.

Feld describes TechStars (founded in 2006 with David Cohen) as an example of how to build a regional accelerator. In contrast to other accelerators TechStars is mentor-driven, with a profound belief that entrepreneurs learn best from other entrepreneurs. It’s a 90-day program with a clear beginning and end for each cohort. TechStars selection criteria is to first focus on picking the right team then the market. They invest $118,000 ($18k seed funding + $100K convertible note) in 10 teams per region.

Role of Universities

To the entrepreneurial community Stanford and MIT are held up as models for “outward-facing” research universities. They act as community catalysts, as a magnet for great entrepreneurial talent for the region, and as teachers and then a pipeline for talent back into the region. In addition their research offers a continual stream of new technologies to be commercialized.

Feld’s observation is that that these schools are exceptions that are hard to duplicate. In most universities entrepreneurial engagement is not rewarded, there’s a lack of resources for entrepreneurial programs and cross-campus collaboration is not in the DNA of most universities.

Rather than thinking of the local university as the leader, Feld posits a more effective approach is to use the local college or university as a resource and a feeder of entrepreneurial students to the local entrepreneurial community. He uses Colorado University’ Boulder as an example of of a regional university being as inclusive as possible with courses, programs and activities.

Finally, he suggests engaging alumni for something other than fundraising – bringing back to the campus, having them mentor top students and celebrating their successes.

Role of Government

Feld is not a big fan of top-down government driven clusters. He contrasts the disconnect between entrepreneurs and government. Entrepreneurs are painfully self-aware but governments are chronically not self-aware. This makes government leaders out of touch on how the dynamics of startups really work. Governments have a top-down command and control hierarchy, while entrepreneurs work in a bottoms-up networked world. Governments tend to focus on macro metrics of economic development policy while entrepreneurs talk about lean, startups, people and product. Entrepreneurs talk about immediate action while government conversations about policy do not have urgency. Startups aim for immediate impact, while governments want to control. Startup communities are networked and don’t lend themselves to a command and control system.

Community Culture

Feld believes that the Community Culture, how individuals interact and behave to each other, is a key part of defining and entrepreneurial community. His list of cultural attributes is an integral part of Silicon Valley. Give before you get, (in the valley we call this the “pay it forward” culture.) Everyone is a mentor, so share your knowledge and give back. Embrace weirdness, describes a community culture that accepts differences. (Starting post World War II the San Francisco bay area became a magnet for those wanting to embrace alternate lifestyles. For personal lifestyles people headed to San Francisco. For alternate business lifestyles they went 35 miles south to Silicon Valley.)

I was surprised to note that the biggest cultural meme of Silicon Valley didn’t make his Community Culture chapter - failure equals experience.

Broadening the Startup Community

Feld closes by highlighting some of the issues faced by a startup community in Boulder. The one he calls Parallel Universes notes that there may be industry specific (biotech, clean tech etc.) startup communities sitting side-by-side and not interacting with each other.

He then busts the myths clusters tell themselves; “lets be like Silicon Valley” and the “there’s not enough capital here.”

Quibbles

There’s data that that seems to indicate a few of Feld’s claims about about the limited role of venture, universities and governments might be overly broad (but doesn’t diminish his observation that they’re feeders not leaders.) In addition, while Silicon Valley was a series of happy accidents, other national clusters have extracted its lessons and successfully engineered on top of those heuristics. And while I might have misread Feld’s premise about local venture capital, but it seems to be, “if there isn’t a robust venture capital in your region it’s because there isn’t a vibrant entrepreneurial community with great startups. As venture capital exists to service startup when great startups are built investors will show up.” Wow.

Finally, local government top-down initiatives are not the only way governments can incentivize entrepreneurial efforts. Some like the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps have had a big bang for little bucks.

Summary

Entrepreneurship is rising in almost every major city and region around the world. I host at least one region a week at the ranch and each of these regions are looking for a roadmap. Startup Communities is it. It’s a strategic, groundbreaking book and a major addition to what was missing in the discussion of how to build a regional cluster. I’m going to be quoting from it liberally, stealing from it often, and handing it out to my visitors.

Lessons Learned

Entrepreneurs lead a startup community while everyone else feeds the community

Feeders include the government, universities, investors, mentors, service providers and large companies

Continual activities and events are essential to engage all participants

Top-down government-driven clusters are an oxymoron

Building a regional entrepreneurial culture is critical

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Secret History of Silicon Valley, Teaching, Venture Capital

September 21, 2012

Why Too Many Startups (er) Suck

This is a guest post by my Startup Owner’s Manual co-author Bob Dorf.

——————-

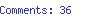

While statistics are weak on startup success rates, the worst one I’ve seen suggests that 2 in 1000 venture backed startups will ever achieve $100-million or more in valuation. Another stat puts that number at 2% rather than 0.2%. Either way, the “hurdle” for successful, scalable startups is high, and it gets higher every day as customer acquisition challenges continue to increase.

I’ve spent more than four decades founding, coaching, teaching and investing in startups, and nothing breaks my heart more than meeting a starry-eyed founder who says “we’re almost ready to show it to people.” The “it” is a physical or web product they’ve often been locked-down, pounding away at, for many weeks.

In my view, this is the nastiest of all startup sins: failing to involve customers and their feedback from literally the first day of a startup’s life, keeping the most vital opinions silent—those of the eventual customers—for far longer than necessary.

When I hear this comment, as I do far too often, I switch to pleading mode: “Please. Take a week. Get some feedback. Does anybody really care, or are they giving you polite nods and little more. This generally leads to the second biggest reason too many startups suck: they’re solving a non-problem.

Does anybody care? Many Startup Owner’s Manual readers ask why Steve Blank and I are adamant that Customer Discovery happen in two separate, distinct phases: “problem” discovery and, later, “solution” discovery. There’s just no other way but, as Steve Blank has said for a decade, to “get out of the building” and talk to the only folks who matter—your customers.

Building a solution to a problem of moderate or lukewarm interest to users is a long-term death sentence for startups, where founders will almost certainly commit to 20,000 hours of their lives(or 5 years of 80-hour workweeks) in order to “beat the odds” and deliver a breakout success: a sustainable, scalable, profitable business.

Why, then, are so many founders so reluctant to invest even 500 or 1,000 hours upfront to be sure that, when they’re done, the business they’re building will face genuine, substantial demand or enthusiasm. Without passionate customers, even the most passionate entrepreneur will flounder at best. Dropbox is a great example. It scaled like lightning by solving an urgent, painful problem for millions of consumers. The product is so good, helpful, and easy to use that it literally almost does its own marketing organically through the product’s viral nature, just as Hotmail and Gmail have done since inception.

What’s the honest trajectory? There can only be one Mark Zuckerberg, and at last look he’s young and healthy. Can every startup skyrocket like Facebook or Square or Google? It’s downright impossible. The solution: understand your startup’s “honest trajectory” and align objectives of the founding team and—importantly—its investors to define and agree about what “success” looks like. Thousands of entrepreneurs would be a lot happier if their focus was a solid, growable, defensible niche business that might never go public or be worth $100-million. There’s a ton of money to be made “in the middle,” a broad swath between struggling or gasping for cash and ringing the bell at the NASDAQ.

Find the right trajectory for your business and focus not only on reaching it, but on assuring that the result is a sustainable, repeatable profit engine that can perform and grow healthily over time. Use Customer Development to identify and refine the potential profitable niche and stay in close contact with customers as you build, to be sure you’re building something they’ll want to have…and keep.

Stand Out in the Crowd: If you’re solving an important problem, make sure your solution stands out in the crowd. Hundreds of entrepreneurs I’ve met never spent an entire day Googling their industry, other ways to solve “their” problem, and few have spent time “playing consumer,” trying to find “their” own product, or one like it, and creating a “market map” that assesses all the competitive solutions, their strengths/weaknesses, and where the new product fits clearly and distinctly in its competitive environment. If you can’t figure this out on your own, and relate it to customers succinctly, it’s a certainty that your customers never will.

Going Forward is NOT About Standing Still: Another of my high-frequency “sad” moments happens when visiting with a team that is consistently “flatlining,” or delivering minimal or trivial user growth week after week or worse. Clearly, something’s horribly wrong, and everyone just keeps showing up, doing their jobs, without attacking the core problem that’s almost always a lack of palpable customer enthusiasm. What’s the point? What are they waiting for? It’s time to bring the leadership team into a room, dissect each key element of the business model, and identify pivots that are worth exploring smartly—where else—with customers.

Going Forward Is Often About Going Backward First: Entrepreneurs pride themselves in their problem-solving abilities, tenacity, and willingness to run through brick walls to make things “go.” More often than not, the DNA strand that makes entrepreneurs great is the one that’s their undoing when confronted with “flatlining” user adoption, growth, referrals, or frequency. These entrepreneurs need to switch smartly out of “do” mode and return to the earliest “discovery” steps to find a distinctive, exciting solution to a seriously painful customer need or problem.

It’s the only way to make a startup not suck.

Filed under: Customer Development

September 6, 2012

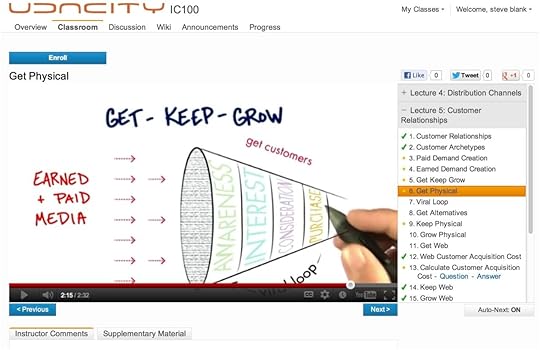

The Lean LaunchPad Online

You may have read my previous posts about the Lean LaunchPad class taught at Stanford, Berkeley, Columbia, Caltech and for the National Science Foundation.

Now you too can take this course.

I’ve worked with the Udacity, the best online digital university on a mission to democratize education, to produce the course. They’ve done an awesome job.

The course includes lecture videos, quizzes and homework assignments. Multiple short video modules make up each 20-30 minute Lecture. Each module is roughly three minutes or less, giving you the chance to learn piece by piece and re-watch short lesson portions with ease. Quizzes are embedded within the lectures and are meant to let you check-in with how completely you are digesting the course information. Once you take a quiz, which could be a multiple-choice quiz or a fill in the blank quiz, you will receive immediate feedback.

Sign up here

——–

Why This Class?

Ten years ago I started thinking about why startups are different from existing companies. I wondered if business plans and 5-year forecasts were the right way to plan a startup. I asked, “Is execution all there is to starting a company?”

Experienced entrepreneurs kept finding that no business plan survived first contact with customers. It dawned on me that the plans were a symptom of a larger problem: we were executing business plans when we should first be searching for business models. We were putting the plan before the planning.

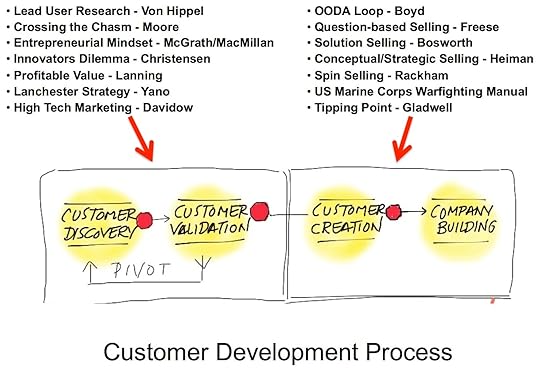

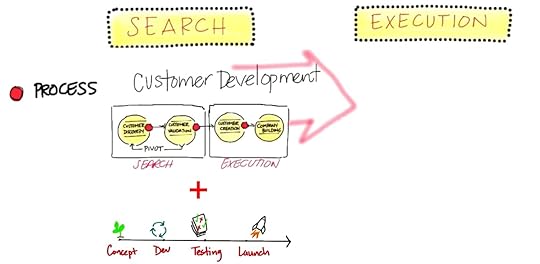

So what would a search process for a business model look like? I read a ton of existing literature and came up with a formal methodology for search I called Customer Development.

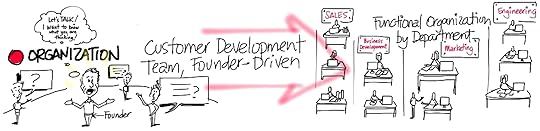

That resulted in a new process for Search: Customer Development + traditional product management/Waterfall Engineering. It looked like this:

This meant that the Search for a business model as a process now could come before execution. So I wrote a book about this called the Four Steps to the Epiphany.

And in 2003 the Haas Business School at U.C. Berkeley asked me to teach a class in Customer Development. With Rob Majteles as a co-instructor, I started a tradition of teaching all my classes with venture capitalists as co-instructors.

In 2004 I funded IMVU, a startup by Will Harvey and Eric Ries. As a condition of my investment I insisted Will and Eric take my Customer Development class at Berkeley. Having Eric in the class was the best investment I ever made. Eric’s insight was that traditional product management and Waterfall development should be replaced by Agile Development. He called it the “Lean Startup.”

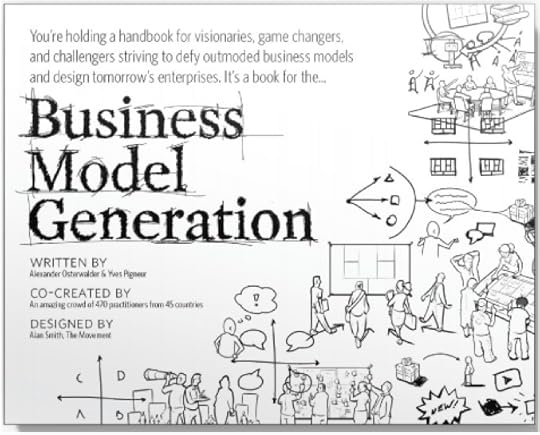

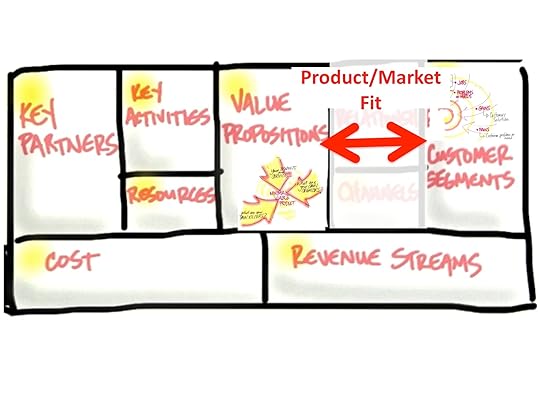

Meanwhile, I had said startups were “Searching” for a business model, I had been purposefully a bit vague about what exactly a business model looked like. For the last two decades there was no standard definition. That is until Alexander Osterwalder wrote Business Model Generation.

This book was a real breakthrough. Now we understood that the strategy for startups was to first search for a business model and then after you found it, put together an operating plan.

Now we had a definition of what it was startups were searching for. So business model design + customer and agile development is the process that startups use to search for a business model.

And the organization to implement all this was not through traditional sales, marketing and business development groups on day one. Instead the founders need to lead a customer development team.

And then to get things organized Bob Dorf and I wrote a book, The Startup Owners Manual that put all these pieces together.

But then I realized rather than just writing about it, or lecturing on Customer Development, we should have a hands-on experiential class. So my book and Berkeley class turned into the Lean LaunchPad class in the Stanford Engineering school, co-taught with two VC’s – Jon Feiber and Ann Miura-Ko. And we provided dedicated mentors for each team.

Then in the fall of 2011, the National Science Foundation read my blog posts on the Stanford version of the Lean LaunchPad class. They said scientists had already made a career out of hypotheses testing, and the Lean LaunchPad was simply a scientific method for entrepreneurship. They asked if I could adapt the class to teach scientists who want to commercialize their basic research. I modified the class and recruited another great group of VC’s and entrepreneurs – Jim Hornthal, John Burke, Jerry Engel,Bhavik Joshi and Oren Jacob – to teach with me.

We taught the first two classes of 25 teams each, and then in March of 2012 trained faculty from Georgia Tech and the University of Michigan how to teach the class at their universities. Georgia Tech and the University of Michigan faculty then taught 54 teams each in July of this year and will teach another 54 teams in October.

We then added four more schools – Columbia, Caltech, Princeton and Hosei – where our team taught the Lean LaunchPad. We also developed a 5-day version of the class to complement the full semester and quarter versions.

Then last month we partnered with NCIIA and taught 62 college and university educators in our first Lean LaunchPad Educators Program.

And now we’ve spent weeks in the Udacity studio putting the lecture portion of the Lean LaunchPad class online.

Sign up and find out how to start a company!

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad

September 4, 2012

Entrepreneurship is hard but you can’t die

We Sleep Peaceably In Our Beds At Night Only Because Rough Men Stand Ready To Do Violence On Our Behalf

Everyone has events that shape the rest of their lives. This was one of mine.

——-

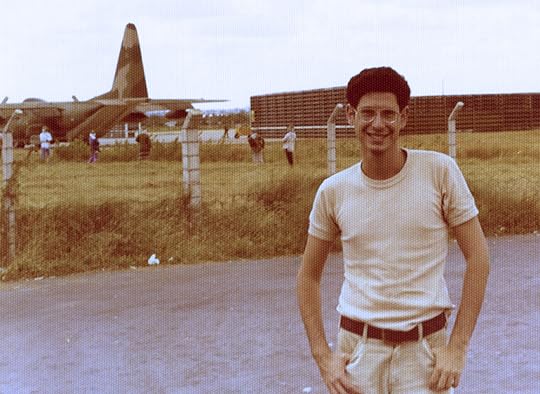

I’ve never been shot at. Much braver men I once worked with faced that every day. But for a year and a half I saw weapons of war take off every day with bombs hanging under the wings. It never really hit home until the day I realized some of the planes didn’t come back.

Life in a War Zone

In the early 1970’s the U.S. was fully engaged in the war in Vietnam. Most of the fighter planes used to support the war were based in Thailand, or from aircraft carriers (or for some B-52 bombers, in Guam.) I was 19, in the middle of a hot war learning how to repair electronics as fast as I could. It was everything life could throw at you at one time with minimum direction and almost no rules.

It would be decades before I would realize I had an unfair advantage. I had grown up in home where I learned how to live in chaos and bring some order to my small corner of it. For me a war zone was the first time all those skills of shutting out everything except what was important for survival came in handy. But the temptations in Thailand for a teenager were overwhelming: cheap sex, cheap drugs (a pound of Thai marijuana for twenty dollars, heroin from the Golden Triangle that was so pure it was smoked, alcohol cheaper than soda.) I saw friends partying with substances in quantities that left some of them pretty badly damaged. At a relatively young age I learned the price of indulgence and the value of moderation.

What a great job

But I was really happy. What a great job – you work hard, party hard, get more responsibility and every once in awhile get to climb into fighter plane cockpits and turn them on. What could be better?

Near the beginning of the year when I was at an airbase called Korat, a new type of attack aircraft showed up – the A-7D Corsair. It was a single seat plane with modern electronics (I used to love to play with the Head Up Display.) And it was painted with a shark’s mouth. This plane joined the F-4’s and F-105 Wild Weasels (who went head-to-head with surface-to-air missiles,) and EB-66’s reconnaissance aircraft all on a very crowded fighter base.  While the electronics shop I worked in repaired electronic warfare equipment for all the fighter planes, I had just been assigned to 354th Fighter Wing so I took an interest in these relatively small A-7D Corsair’s (which had originally been designed for the Navy.)

While the electronics shop I worked in repaired electronic warfare equipment for all the fighter planes, I had just been assigned to 354th Fighter Wing so I took an interest in these relatively small A-7D Corsair’s (which had originally been designed for the Navy.)

He’s Not Coming Back

One fine May day, on one of my infrequent trips to the flight line (I usually had to be dragged since it was really hot outside the air-conditioned shop), I noticed a few crew chiefs huddled around an empty aircraft spot next to the plane I was working on. Typically there would have been another of the A-7’s parked there. I didn’t think much of it as I was crawling over our plane trying to help troubleshoot some busted wiring. But I started noticing more and more vans stop by with other pilots and other technicians– some to talk to the crew chief, others just to stop and stare at the empty spot where a plane should have been parked. I hung back until one of my fellow techs said, “Lets go find out what the party is about.”

We walked over and quickly found out it wasn’t a party – it was more like a funeral. The A-7 had been shot down over Cambodia. And as we found out later, the pilot wasn’t ever coming home.

An empty place on the flight line

While we were living the good life in Thailand, the Army and Marines were pounding the jungle every day in Vietnam. Some of them saw death up close. 58,000 didn’t come back – their average age was 22.

Everyone shook their heads about how sad. I heard later from “old-timers” who had come back for multiple tours “Oh, this is nothing you should have been here in…” and they’d insert whatever year they had been around when some days multiple planes failed to return. During the Vietnam War ~9,000 aircraft and helicopters were destroyed. Thousands of pilots and crews were killed.

It’s Not a Game

I still remember that exact moment – standing in the bright sun where a plane should be, with the ever present smell of jet fuel, hearing the engines of various planes taxing and taking off with the roar and then distant rumble of full afterburners – when all of a sudden all the noise and smells seemed to stop – like someone had suddenly turned off a switch. And there I had a flash of realization and woke up to where I was. I suddenly and clearly understood this wasn’t a game. This wasn’t just a big party. We were engaged in killing other people and they were equally intent on killing us. I turned and looked at the pilots with a growing sense of awe and fear and realized what their job – and ours – was.

That day I began to think about the nature of war, the doctrine of just war, risk, and the value of National Service.

Epilogue

Captain Jeremiah Costello and his A-7D was the last attack aircraft shot down in the Vietnam War.

Less then ninety days later the air war over Southeast Asia ended.

For the rest of my career when things got tough in a startup (being yelled at, working until I dropped, running out of money, being on both ends of stupid decisions, pushing people to their limits, etc.), I would vividly remember seeing that empty spot on the flightline. It put everything in perspective.

Entrepreneurship is hard but you can’t die.

Filed under: Air Force, Family/Career/Culture

August 27, 2012

Vision versus Hallucination – Founders and Pivots

A founder’s skill is knowing how to recognize new patterns and to pivot on a dime. At times the pattern is noise, and the vision turns out to be a hallucination. Knowing how to sort between vision and hallucination can avoid chaos inside your startup.

———

Yuri, one of my ex students started a big-data analytics company last year. He turned his PhD thesis into a killer product, got it funded and now was CEO of a company of 30. It was great to watch him embrace the spirit and practice of customer development. He was constantly in front of customers, listening, selling, installing and learning.

And that’s where the problem was.

I got to spend time inside his company while I was using their software to analyze early-stage ventures. What I saw reminded me of some of the best and worst things I did as a founder.

A Pivot a Week

It seemed like once a week Yuri would come back from a customer meeting brimming with new insights. “We’re building the wrong product!” he’d declare. “We got to pivot now.” Tossing their agile development process and at times their entire business model in the air, the company would go into fire-drill mode and engineering would start working on whatever his latest insight was.

Other weeks Yuri would be buffeted by the realities of his burn rate, declining bank account and depressing comments from customers. This time he’d be back in the building declaring “We’re going to be out of business in 3 months if we don’t get our act together.” I even heard him say to a customer, “If we don’t get your order we’ll just have to close up in 90 days.”

As a consequence everyone was afraid to make a decision because they couldn’t guess what Yuri wanted to do that week. Some of the engineers figuring if the founder was declaring they were toast in 90 days were updating their resumes. The company already was gaining a reputation as one without a coherent strategy.

I cringed when I saw this – it sounded like me early in my career. I would come back from customer visits convinced that what I just learned was the “real” solution to the company’s future and havoc would reign.

Unfortunately for Yuri’s company, while there were three other founders, Yuri was the CEO and none of them had the stature to tell him that his “insights” were damaging his company.

So when we had a few minutes alone I offered Yuri that he was misusing the word “pivot” and confusing it with “whatever I feel like at the moment.” I said, “You got to realize you’re not just a smart engineer anymore; 30 people are dropping everything they’re doing when you make these pronouncements.”

Pivot as an excuse

I wasn’t surprised when he pushed back, “I’m just getting out of the building and listening to customers. All I’m doing is pivoting based on their feedback.” By now I’ve heard this more times than I liked. “Yuri, one of the things that you make you a great founder is that you have insight others don’t. But like all great founders some of these insights are simply hallucinations. The problem is you and other founders want immediate action every time you have a new idea.”

“That’s a mistake.”

“A pivot is a substantive change to one or more of components to your business model. You’re using “Pivot” as an excuse to skip the hard stuff – keeping focused on your initial vision and business model and integrating what you’ve heard if and only if you think it’s a substantive improvement to your current business model. There is no possible way you can garner enough information to pivot based on one customers feedback or even 20. You need to make sure it’s a better direction than the one you are already heading in.”

Sit on it for awhile

I said, “Sit on your great insights for 72 hours and see if they still seem good after reflection. Better, during that time brainstorm them with someone you trust. If not your co-founders, someone outside the company.”

I offered that at Epiphany, my partner Ben’s office was the first place I would go when I thought I had new “insights.” And we’d run them to the ground for days before we’d even let anyone else know. Most of the time after a few days of thought, these insights were really not much better than the current course the company was on. Or by then other customers would tell us something quite different. And the rule was we weren’t changing anything about the product architecture until Ben and I agreed. Which required Ben hearing from the same customers I did.

Change Value Proposition Last

Change Value Proposition Last

Second, that he needed to recognize that changing the value proposition – the features of the products/services he was offering – was a lot more traumatic for a startup than changing other parts of the business model.

He should make sure that there aren’t other parts of the business model (revenue model, pricing, partners, channel, etc.) that couldn’t change before he declares “we’re building the wrong product.”

In searching for product/market fit (the right match between value proposition and customer segment) the product should be the last part you think of changing – not the first – as the cost of upending your product development organization is high.

And to make sure everyone knew what he was doing, he might want to consider letting the entire company know “don’t worry when I’m talking about changing our business model every week – it’s a natural part of searching – only worry if I ask you to change the value proposition every month.”

Find a Brainstorm Buddy

Finally, I suggested that he find someone he respects on his advisory board, who he was comfortable brainstorming with and would tell him when he has a bad idea.

Yuri sat quietly for awhile. I wasn’t sure he had heard a thing I said, until he said “Wait 72 hours? I can do that. Now can I call you when I have a hot new idea?

Lessons Learned

Founders are great at seeing things others don’t – at times it’s a vision, most often it’s a hallucination

Founders want immediate action – often they call it a pivot

A Pivot should not be an excuse for a lack of a coherent strategy or a lack of impulse control

Disconnect your insights from you mouth for 72-hours

If you can unilaterally overrule your co-founders there are no brakes on you

Your board members are not your brainstorm buddies-find others you trust

Filed under: Customer Development

August 24, 2012

The Lean LaunchPad Class Online

August 20, 2012

When Microsoft Threatened to Sue Us Over the Letter “E”

By 1997 E.piphany was a fast growing startup with customers, revenue and something approaching a repeatable business model. Somewhere that year we decided to professionalize our logo (you should have seen the first one.) With a massive leap of creativity we decided that it should it should have our company name and the letter “E” with a swoop over it.

By 1997 E.piphany was a fast growing startup with customers, revenue and something approaching a repeatable business model. Somewhere that year we decided to professionalize our logo (you should have seen the first one.) With a massive leap of creativity we decided that it should it should have our company name and the letter “E” with a swoop over it.

1997 was also that year that Microsoft was in the middle of the browser wars with Netscape. Microsoft had just released Internet Explorer 3 which for the first time was a credible contender. With the browser came a Microsoft logo.  And with that same massive leap of creativity Microsoft decided that their logo would have their product name and the letter “E’ with a swoop over it.

And with that same massive leap of creativity Microsoft decided that their logo would have their product name and the letter “E’ with a swoop over it.

One of E.piphany’s product innovations was that we used this new fangled invention called the browser and we ran on both Netscape and Microsoft’s. We didn’t think twice about.

That is until the day we got a letter from Microsoft’s legal department claiming similarity and potential confusion between our two logos.

They demanded we change ours.

I wish I still had their letter. I’m sure it was both impressive and amusing.

I had forgotten all about incident this until this week when Doug Camplejohn, E.piphany’s then VP of Marketing somehow had saved what he claims was my response to Microsoft’s legal threat and sent it me. It read:

Response Letter to Bill Gates

Dear Bill,

We are in receipt of your lawyer’s letter claiming Microsoft’s

ownership of the look and feel of the letter “e”. While I understand

Microsoft’s proprietary interest in protecting its software, I did not

realize (until the receipt of your ominous legal missive) that one of

the 26 letters in the English language was now the trademarked

property of Microsoft.

Given the name of your company, claiming the letter “e” is an unusual

place to start. I can understand Microsoft wanting exclusive rights to

the letter “M” or “W”, but “e”? I can even imagine a close family

member starting your alphabet collection by buying you the letters “B”

or “G” as a birthday present. Even the letters “F” “T” or “C” must be

more appealing right now then starting with “e”.

In fact, considering Microsoft’s financial health and legal prowess

you may want to consider buying a symbol rather than a letter.

Imagine the value of charging royalties on the use of the dollar “$”

sign.

I understand the legal complaint refers to the similarities of our use

of “e” in the Epiphany corporate logo to the “e” in the Internet

Explorer logo. Given that the name of my company and the name of your

product both start with the same letter, it doesn’t take much

imagination to figure out why we both used the letter in our logos,

but I guess it has escaped your lawyers.

As to confusion between the two products, it is hard for me to

understand why someone would confuse a $250,000 enterprise software

package (with which we require a customer to buy $50,000 of Microsoft

software; NT, SQL Server and IIS), with the free and ever present

Internet Explorer.

Given that Microsoft sets the standard for most things in the computer

industry, I hope we don’t open the mail next week and find Netscape

suing us for using the letter “N”, quickly followed by Sun’s claim on

“J”. Perhaps we can submit all 26 letters to some sort of standards

committee for arbitration.

Come to think of it, starting with “e” is another brilliant Microsoft

strategy. It is the most common letter in the English language.

Steve Blank

Epilogue

Given later that year Microsoft ended up being a large multi-million dollar E.piphany customer all I can assume is that cooler heads prevailed (more than likely our new CEO,) and this letter was never sent and the threatened lawsuit never materialized.

Ironically, since the turn of the century Microsoft has done great things for entrepreneurs. Their BizSpark and DreamSpark programs have become the best corporate model of how a large company can successfully partner with startups and students worldwide.

But I am glad we helped keep the letter E in the public domain.

Filed under: E.piphany, Marketing

August 17, 2012

At times not losing is as important as winning

At times not losing is as important as winning.

Customer Validation

E.piphany was an 11-month-old startup with 31 people and on fire. We had closed four $100,000 deals for our customer relationship management software.

Joe Dinucci, our VP of Sales, was hot on the trail of our next big order. He had just demo’d our product to his friend, the CFO of Autodesk. After seeing the demo, the CFO walked Joe over to the office of Autodesk’s VP of sales, and said to her, “I think this product might solve your sales reporting problem.”

After a demo she agreed it would.

Joe came back to our company excited. If we won the Autodesk account it could be worth half a million dollars or more.

They Have A Problem and Know It

At the time Autodesk’s sales organization was frustrated with their IT department. It took weeks or months for Sales to get financial, sales results and customer reports from IT. Autodesk’s VP of Sales fit the profile of a earlyvangelist: she understood she had a pressing problem (couldn’t get timely data needed to forecast sales), she was searching for a solution (beating up the Autodesk CIO on a weekly basis to solve her problem), she had a timetable for a solution (now) and her company had committed budget dollars to solve this problem (they spend anything to stop missing forecasts.)

A Match Made in Heaven

For the next several weeks, the entire E.piphany engineering department worked with Autodesk’s sales operation team to build a prototype using real Autodesk data. Joe made a compelling ROI (Return On Investment) presentation to the VP of Sales and the CFO. E.piphany and Autodesk seemed like a match made in heaven and it looked like we had a $500,000 deal that could close in weeks.

Not quite.

The CIO

The CFO casually mentioned that as IT would install and maintain the system, they would have to recommend and sign off on an E.piphany purchase. As the CIO worked for the CFO, Joe paid what he thought was a courtesy call on Autodesk’s CIO.

The CIO didn’t say much in the presentation (warning, warning) and he passed Joe on to his manager of data warehouse development. What Joe didn’t know was that months ago, this IT group has been tasked to solve Sales’ reporting problems and was struggling with the complexity and difficulty of extracting data from SAP.

Joe was aware of the tense history between Autodesk sales and its IT department, but given how happy the VP of Sales was with E.piphany’s prototypes plus Joe’s personal relationship with the CFO, he didn’t see this as a serious obstacle. Joe believed the IT organization had nothing but technical piece parts to compete with E.piphany’s complete solution. Given E.piphany had a vastly superior solution, Joe believed there was no logical way they could recommend to the CIO to deploy anything else but E.piphany.

Joe was aware of the tense history between Autodesk sales and its IT department, but given how happy the VP of Sales was with E.piphany’s prototypes plus Joe’s personal relationship with the CFO, he didn’t see this as a serious obstacle. Joe believed the IT organization had nothing but technical piece parts to compete with E.piphany’s complete solution. Given E.piphany had a vastly superior solution, Joe believed there was no logical way they could recommend to the CIO to deploy anything else but E.piphany.

Wrong.

The IT Revolt

Unbeknownst to Joe a revolt was brewing in Autodesk’s IT organization. “Sales keeps asking for all these reports and now they are telling us what application to buy? If we deploy E.piphany’s entire solution, we’ll all be out of jobs. But if we recommend software tools from another startup, we could say we’re solving the needs of the Sales VP and still keep our jobs.“

Late in the afternoon, Joe got a call from a friend in Autodesk’s IT department warning that they were give the order to another startup. And the CIO would approve the recommendation and pass this to his boss, the CFO, the next day.

We’re Going to Lose

Joe arrived in my office, his face making it clear he brought bad news. E.piphany was now about to lose a half million-dollar Autodesk sale. Joe looked at his shoes while he muttered his frustrations with internal Autodesk politics.

We had a long discussion about the consequences if we lost. It was one thing for a startup to lose to a large company like Oracle or IBM. But to lose the sale to another startup with an inferior product would have been psychologically devastating to our little startup. E.piphany’s product development team had spent weeks inside the account, and they believed the deal was all but won. The competitor would trumpet the sales win far and wide and use the momentum to get more sales.

We couldn’t afford to lose this sale. What could we do?

The Third Way

It struck me that there might be more than two outcomes.Sales had defined the problem as a win or lose situation. But what if we added a third choice? What if we formally, publicly and noisily withdrew from the account? The worst case was that we could tell our engineering team that we should have won but the game was rigged. While we certainly wouldn’t win the business, withdrawing would solve the more emotionally explosive issue of losing. (And In the back of my mind, I believed this third way had a chance of giving us the winning hand.)

At first Joe hated the idea. Like every great sales guy, he was eternally optimistic about the outcome. However, I wasn’t in the mood to put the company’s future at risk on the testosterone levels of our sales guy. Withdrawing by claiming that Autodesk’s IT staff had already decided that it was “any solution but ours” was making the best of a deteriorating sales situation.

Joe called his friend the CFO, waiting until after 5pm, when he was sure he wasn’t in his office, and left him a message: “Thanks for introducing us to the VP of Sales and your technical staff. We really appreciate the opportunity to work with you. Unfortunately it looks like this deal isn’t going to happen. You have a bunch of smart guys working for you, but they are determined to make sure that the status quo won’t change. We have limited resources and can’t continue to give demos and hold meetings when the outcome is predetermined. My guess is we’ll be back in six to nine months when the VP of Sales is still unhappy. I’m going to call her and let her know that we can’t put in the system that she wanted, but I thought I’d check-in with you first. Thanks again for the opportunity.”

The “Take Away” Gambit

This is known as the “take-away” gambit. I believed that by pulling the deal away, there was at least a 50% chance the CFO would do what I knew he didn’t want to – go to his CIO and help him make the “right” decision. I understood that a potential downside consequence of this maneuver was an uncooperative IT organization when we tried to install the product, but by then their check would be in the bank, and I had a plan to win them over.

Joe was concerned that we had just lost the account, but he made the call and left the message.

Two hours later Joe got a call back from the CFO who said,, “Wait, wait! Don’t pull out. Why don’t you come up and meet with me tomorrow morning. I’ve chatted with my staff and we’re now ready for a contract proposal.”

Autodesk became our third paying customer. Over the next year they paid us over $1million for our software.

After a full-court charm offensive, the IT person who wanted anyone but us became our biggest advocate. She keynoted our first user conference.

Lessons Learned

In complex B-to-B sales, multiple “Yes” votes are required to get an order.

A single “No” can kill the deal.

Understanding the saboteurs in a complex sale is as important as understanding the recommenders and influencers

We needed a selling strategy that took all of this into account.

In a startup not losing is sometimes more important than winning.

Filed under: Customer Development, E.piphany, Marketing

August 3, 2012

Massacre at IBM

Long before there was the Lean Startup, Business Model Canvas or Customer Development there was a guy in Santa Barbara California who had already figured it out. Frank Robinson of SyncDev has been helping companies figure out their minimum viable product and pivots since 1984, long before I even knew what it meant. They’ve done it for more than 400 companies ranging in size from 200 hundred starts-ups, one of whom was Citrus Systems that became Citrix, to IBM.

Here’s a guest post from Frank.

———-

I want to tell you a story about how a team pivoted and succeeded by synchronizing product and customer development. Though it’s about a large company, it’s applicable to teams in start-ups. It’s vivid with respect to method and outcome.

Massacre at IBM

Intel was angry at their supplier about a third-generation wafer-inspection system. “How dare you,” the fab manager said. “We shut down production to setup your machine.” He blocked new business for two years.

The supplier’s CEO directed his business unit general managers to take a SyncDev workshop. The inspection- system GM decided to use it for his fourth-generation system, an 18-month program.

Though development was already underway, I kicked-off SyncDev in early November. The core team — a cross-functional team who could make all the business and technical decisions within a set envelop ─ consisted of product manager, hardware-engineering manager, software-engineering manager, applications analyst, and software designer. We would travel throughout the US and Asia to test-sell a validation prototype, listening to each customer as a jury listens to each witness.

The first wave of meetings was with five US customers in mid-November. On Monday, in San Jose, near the factory, we met with UltraTech Stepper, a friendly account. We did a quick overview of the product. That earned us the right to ask questions of fact about their department’s mission, goals, operations, volumes, tools, methods, and success metrics. We asked, “Given all that, what problems are you having?” We followed that with an hour-long design review, including disclosure of product limitations. For 30 minutes we did trial closes: Who would use it, how often, how would you justify it, and where does it rank on a list of purchase and to-do priorities.

The customer asked, “Where’s off-line setup?” The product manager said, “It’s in the release after this.”

That night we flew to Boise. Tuesday, 17 people at Micron asked the same question. We responded the same way.

We took a red-eye to JFK and a commuter to Burlington, VT for a 9:00 AM Wednesday meeting at IBM. At noon the boss said, “You guys have no credibility. We’ve asked for off-line setup for years. No one listened!”

Leaving the parking lot, the engineering managers in the back row of the van argued. The product manager who was driving whispered, “For years that said no one needs off-line setup. Now they’re arguing about how to do it.”

Wednesday night we flew to Orlando for A&T. Thursday, off line set up was not an issue. The same thing happened on Friday in Austin. Off-line set up had disappeared into the team’s rearview mirror.

Thanksgiving had come early that year. We were on the road again by late November to meet IBM in Fishkill, NY. After a 15-minute overview, they asked about off-line set up. After we responded their boss said, “Gentlemen, this meeting is over. We don’t want to hear about your roadmap. Please leave!”

Humiliated and depressed, our ride to the hotel felt more like one in a hearse than a van. The customer’s wants the next day would be no different. The product manager described the metamorphosis:

We gathered that night at the hotel, but we were changed. Humility had crumbled the walls between marketing and engineering. We had heard the voice of the customer as a team and they were unhappy. Thank God the whole team was there so we could decide on the spot.

For appetizers we slashed requirements. For soup we compressed schedule. For the main course we sliced up the configuration into bite-size pieces. For dessert we integrated customers into our testing. For after-dinner drinks we polished the new presentation and said a short prayer.

The next day was sunny. Breakfast was actually jovial. We looked back at yesterday with humor, not to cover our humiliation but because we had pivoted.

The next meetings went far better. We took wounds, but none like those at Fishkill. We continued with three more meetings. We returned to the factory and presented our new path.

“Are you nuts?” our product board asked. “You can’t change direction midstream!”

Without missing a beat, Engineering quoted the customer. I explained how we’d manage technical risks. We were a team, convinced by a shared experience, that we knew what to do. Better yet, we had switched the burden of proof from us to our skeptics.

In December and January we met with ten customers in Korea, Japan, and China. Changes were minor. Instead of pivoting we built virtual backlog.

In February, we returned to Fishkill. “Congratulations, gentlemen,” IBM said, “We apologize for November. With the train heading our way, we’ll get on now. We’ll take two more old units (multi-million dollar) now and replace all seven with new ones when it ships.”

In 90 days the team pivoted the product, saved a major account, captured a large order, cut schedule from 18 months to nine months, and developed virtual backlog.

Two years after release, product market share was up by 30% to 70%. Twelve of 17 competitors were gone. The division was the dominant global player.

The team followed these rules:

Cardinal Rules of Synchronous Customer and Product Development

Meet Customers as a Core, Cross-Functional Team authorized to act within a defined envelop.

Report to a “Board,” to explain and defend your strategy and business case

Meet Customers’ Decision Making Teams not just users

Meet on Site in the customers’ habitat: Home, office, lab, factory, or playground. See what they do. Meet their colleagues, form relationships, help fix stuff now, and return as required

Test Sell a Validation Prototype: Renderings, specs, and props. Don’t sell a vision! False positives result.

Ask questions. Take Notes. Ask question of fact, not opinion and shut up. Take notes. Tag data and quotes.

Disclose Limitations to surface objections. It enhances your credibility, too.

Conduct Trial closes. There are thirty good ones starting on slide one.

Meet in Waves to get bonked over the head by patterns, two customers per day, Tuesday to Thursday.

Find and Fix Bad News. Bad news early is good news, if you find and fix it early.

Filed under: Customer Development

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers