Steve Blank's Blog, page 44

February 26, 2013

Failure and Redemption

“What’s gone and what’s past help

Should be past grief.”

William Shakespeare - The Winter’s Tale

We give abundant advice to founders about how to make startups succeed yet we offer few models about dealing with failure.

So here’s mine.

——–

In my experience, living through failure has 6 stages:

Stage 1: Shock and Surprise

Stage 2: Denial

Stage 3: Anger and Blame

Stage 4: Depression

Stage 5: Acceptance

Stage 6: Insight and Change

While I had been part of a few failed startups, none of them had fallen squarely on my shoulders until Rocket Science Games where my business card said CEO. It was there that I lived through all 6 stages and came out the other side a changed man.

Failure

Stage 1: Shock and Surprise

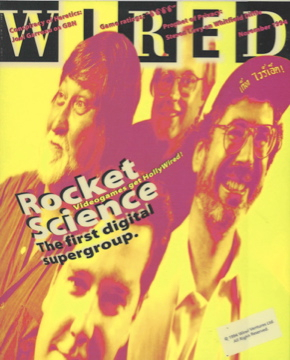

We raised $35 million and after 18 months made the cover of Wired magazine.  The press called Rocket Science one of the hottest companies in Silicon Valley and predicted that our games would be great because the storyboards and trailers were spectacular. 90 days later, I found out our games are terrible, no one is buying them, our best engineers started leaving, and with 120 people and a huge burn rate, we’re running out of money and about to crash. This can’t be happening to me.

The press called Rocket Science one of the hottest companies in Silicon Valley and predicted that our games would be great because the storyboards and trailers were spectacular. 90 days later, I found out our games are terrible, no one is buying them, our best engineers started leaving, and with 120 people and a huge burn rate, we’re running out of money and about to crash. This can’t be happening to me.

Stage 2: Deny any of it was your fault

In my mind, I had done everything the investors asked me to do. I raised a ton of money and got a ton of press. We hired everyone according to our plan. It was everyone else who screwed up. I did everything right.

Stage 3: Get angry and blame everyone else

This was the fault of my cofounder since he was in charge of game development, it was the engineers who bailed on me, it was the sales and marketing people who didn’t tell me how bad the games were, it was the VC’s who refused to put any more money in the company, it was Sega’s fault for making a bad gaming platform…

State 4: Get depressed

When the inevitability and magnitude of the failure sunk in, I slept in a lot. There were days I’d get up late and go to bed again at 5 pm. I lost interest in anything associated with my past industry. (To this day I still can’t play a video game.)

Redemption

Step 5: Gradually accept your role in the failure

A few weeks after leaving, I began to think about what I should have done, could have done and pondered why I didn’t do it. (I didn’t listen, I didn’t act, I didn’t own my role as CEO, I wasn’t prepared to do what was right or leave.) This was hard and didn’t happen overnight. My wife was a great partner here. I often reverted to Stages 2 and 3, but over time I took ownership of my primary role in the debacle.

Stage 6: Gain insight and change your behavior

This was the hardest part. While I stopped blaming others, understanding what I could change in my behavior took long months. It would have been much easier to just move on, but I was looking for the lessons that would make my next startup successful. I looked at the patterns of behavior, not just at my last company but also across my entire career. I learned how to dial back the hubris, get other smart people to work with me – rather than just for me, listen better, and act and do what was right – regardless of what others thought I should do.

Epilogue

For my next startup I parked the behaviors that drove Rocket Science off the cliff. We established a team of founders who worked collaboratively. When my co-founders and I got the company scalable and repeatable, we hired an operating executive as the CEO and returned a billion dollars to each of our two lead investors.

Now when I listen to entrepreneurs who’ve cratered a company, I listen for their stories of failure and redemption.

Lessons Learned

Six stages of failure and redemption

Don’t get stuck in Stages 2, 3 or 4 - move forward

Don’t skip acceptance of your role

Get to insight so you can change your behavior—then commit to the challenge of doing it differently the next time

Filed under: Family/Career/Culture, Science and Industrial Policy

February 23, 2013

Why Big Companies Can’t Innovate

My friend Ron Ashkenas interviewed me for his blog on the Harvard Business Review. Ron is a managing partner of Schaffer Consulting, and is currently serving as an Executive-in-Residence at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley. He is a co-author of The GE Work-Out and The Boundaryless Organization. His latest book is Simply Effective. For what I had thought were a few simple ideas about taking what we’ve learned about startups and applying it to corporate innovation, the post has gotten an amazing reaction. Here’s Ron’s blog post.

———–

What’s striking about Fast Company’s 2013 list of the world’s 50 most innovative companies is the relative absence of large, established firms. Instead the list is dominated by the big technology winners of the past 20 years that have built innovation into their DNA (Apple, Google, Amazon, Samsung, Microsoft), and a lot of smaller, newer start-ups. The main exceptions are Target, Coca Cola, Corning, Ford, and Nike (the company that topped the list).

It’s not surprising that younger entrepreneurial firms are considered more innovative. After all, they are born from a new idea, and survive by finding creative ways to make that idea commercially viable. Larger, well-rooted companies however have just as much motivation to be innovative — and, as Scott Anthony has argued, they have even more resources to invest in new ventures. Sowhy doesn’t innovation thrive in mature organizations?

To get some perspective on this question, I recently talked with Steve Blank, a serial entrepreneur, co-author of The Start-Up Owner’s Manual, and father of the “lean start-up” movement. As someone who teaches entrepreneurship not only in universities but also to U.S. government agencies and private corporations, he has a unique perspective. And in that context, he cites three major reasons why established companies struggle to innovate.

First, he says, the focus of an established firm is to execute an existing business model — to make sure it operates efficiently and satisfies customers. In contrast, the main job of a start-up is to search for a workable business model, to find the right match between customer needs and what the company can profitably offer. In other words in a start-up, innovation is not just about implementing a creative idea, but rather the search for a way to turn some aspect of that idea into something that customers are willing to pay for.

Finding a viable business model is not a linear, analytical process that can be guided by a business plan. Instead it requires iterative experimentation, talking to large numbers of potential customers, trying new things, and continually making adjustments. As such, discovering a new business model is inherently risky, and is far more likely to fail than to succeed. Blank explains that this is why companies need a portfolio of new business start-ups rather than putting all of their eggs into a limited number of baskets. But with little tolerance for risk, established firms want their new ventures to produce revenue in a predictable way — which only increases the possibility of failure.

Finally, Blank notes that the people who are best suited to search for new business models and conduct iterative experiments usually are not the same managers who succeed at running existing business units. Instead, internal entrepreneurs are more likely to be rebels who chafe at standard ways of doing things, don’t like to follow the rules, continually question authority, and have a high tolerance for failure. Yet instead of appointing these people to create new ventures, big companies often select high-potential managers who meet their standard competencies and are good at execution (and are easier to manage).

The bottom line of Steve Blank’s comments is that the process of starting a new business — no matter how compelling the original idea — is fundamentally different from running an existing one. So if you want your company to grow organically, then you need to organize your efforts around these differences.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan

February 19, 2013

Crazy enough to change the world

“Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma – which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of other’s opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.“

Steve Jobs, Stanford University commencement speech, 2005

Last week one of our mentors abruptly resigned from coaching one of the Lean LaunchPad student teams after claiming the students were ignoring his practical advice and years of expertise in the field.

His reaction reminded me one more time why entrepreneurship is an art, why VC’s manage portfolios of companies and why new ideas come from those who don’t respect the status quo.

I’m a Domain Expert Damn It

We always assign experienced mentors to our student teams. In this class this seemed like a perfect fit – a driven (irrational?) founder paired with a mentor who had two operating companies in this space, who had developed and sold vertical market software to companies in this space, and had studied the field as an academic specialty. A match made in heaven? Not exactly.

The mentor tried his best to get the team to look at the actual operating data that exists for this kind of service and the likely regulatory hurdles they will find. He was very negative about the concept and strongly suggested the team do a pivot, but the founder was very determined to make a go of his concept.

He finally quit in frustration.

And here’s the conundrum – given a wise mentor (or VC) with years of experience telling you it’s a bad idea – what should you as the founder do?

Are You Crazy Enough?

What we suggest to teams in the classroom is the same as I suggest to teams in real world startups – after customers and experienced people are telling you it won’t work –

Are you passionate enough to still believe?

Can you explain after why getting out of the building and hearing all the negative news you still want to persevere?

Will it change the world enough to make it worth the trials, travails and pain in getting there?

If so, ignore the other voices. The world moves forward on those who are dissidents. Because without dissent there is no creativity. A healthy disrespect for the status quo coupled with passion, persistence and agility trumps everything else.

Filed under: Customer Development, Teaching

February 7, 2013

Entrepreneurs Experience – Do It and Learn It

In 2012, in partnership with Stanford University, U.C. Berkeley and NCIIA, Jerry Engel and I first offered the Lean LaunchPad Educators Class. The class was designed to teach educators (and the adjunct entrepreneurs that support them) the Lean LaunchPad approach (Business Model Design, Customer Development and Agile Engineering) for teaching entrepreneurship. In addition the class offers a suggested “Lean Entrepreneurship” curriculum and the details of how to teach the capstone Lean LaunchPad class.

Matthew Terrell attended our latest Lean LaunchPad Educators Class. Matthew is an Adjunct Professor of Entrepreneurship at the University of Delaware where he teaches Introduction to Entrepreneurship in course called Entrepreneurs Experience.

He’s the Founder of Vision Creations & Founders Films. Matt asked some of the toughest questions in the class.

—–

I came to the Lean LaunchPad Educators Program 2 ½ day workshop to learn from the best in the business of entrepreneurship education. My fellow attendees were an accomplished collection of international entrepreneurs, investors, educators and in most cases, comprised all three disciplines. I had posed many questions during the three-day workshop, but I was struggling to accept the answer Steve now provided.

During the last session of the program I raised my hand and asked Steve, “Based on what we were learning about the Customer Discovery process, would my students develop a better understanding of entrepreneurship by learning Customer Discovery methods, or by launching a business during the semester generating as much as $50K in sales.” Steve’s answer to my question made me physically and emotionally uncomfortable.

Steve replied, “You have to decide if you’re running an incubator whose goal is revenue or teaching students a methodology that will last them the rest of their lives. The students would be better served if they passed on the cash if it meant they developed a better grasp of the key skills needed to be successful entrepreneurs.” I awkwardly shifted the weight around in my chair, my body tensed up, and I could not believe my ears. Steve said I was welcome to disagree with him, but in the long term, the students would be better off in their careers learning Customer Discovery skills. (To be fair Steve did point out that he did have teams that did both in class. Krave Jerky started in his Berkeley class and showed up with a $500K check from Safeway in the middle of course.) Far be it from me to disagree with a legend, but I struggled to digest his advice.

Take the Money First?

I am a founder first and an adjunct professor second. I am opportunity-obsessed, and I believe the advice I received from Babson President, Len Schlesinger: “Action Trumps Everything.” I love entrepreneurship because it is a full contact sport, requiring complete commitment. New ventures favor the hard-working hustler over the naturally gifted individual. I love teaching entrepreneurship because it sparks a fire in students. As with many educators in this field, I evaluate my success based on the number of new ventures that emerge from our class. Starting a business is a hands-on endeavor, and I am thrilled when my students take action and execute.

Admittedly I have traditionally taught my course with an emphasis on the business plan as the students’ culminating final project. Last year in recognizing the power of the business model canvas, I changed the final project to an Entrepreneurs Action Plan that required two pages of text on each of the nine canvas blocks, and students were required to create an Advisory Board. I felt this was an effective approach but during the Lean LaunchPad workshop, I came to accept the death of the business plan. Steve explained (smiling) that the business plan was most appropriate in a University’s English department, specifically in its creative writing courses as they were all fiction. (What he really said, was that an operating plan comes after you have some facts.)

During the break between sessions at the Lean LaunchPad workshop, I could not resist the opportunity to delve further into this topic with Steve. I explained my position: theories and models are useful learning tools, but nothing beats actual business development experience. We agreed, then, the question remains: What is the goal and desired outcome of the class? My goal is to teach the key skills needed to become a successful founder. Steve said that if this was my goal, then indeed, the Customer Discovery approach is best.

What’s the Goal of Teaching Entrepreneurship?

This concept has consumed me since I returned from the workshop. In trying to accept Steve’s perspective, I surmise that perhaps the customer interview process is not a theoretical feedback survey or focus group, but in fact, it is as dirty as direct sales. I continue to grapple with the issue and will see it firsthand in my class this semester, as my students dive deeper searching during the interview process.

Steve’s second piece of advice I struggle with is the removal of guest speakers. As part of my course, I created Founders Forum, where I host entrepreneurs to come share their early work experiences, their stories building their businesses, their lessons learned, and their advice to aspiring entrepreneurs. I find the firsthand accounts to be extraordinary learning tools for both my students and for me. I discourage PowerPoints and recommend the speakers candidly share experiences from the front lines. Additionally, meeting with speakers grants students an opportunity to develop networking skills. Furthermore, I find the Founders Forum to be a helpful tool in creating a more vibrant local entrepreneurial ecosystem. Steve said, “guest speakers are a wonderful addition to the entrepreneurship curriculum, (and ought to be part of every program as in Stanford’s ecorner speaker series) but they are a distraction in this class. The purpose of the Lean LaunchPad class is full immersion in customer discovery – everything else is a distraction.”

Changes

Since returning from the workshop I rewrote my curriculum and started class last night. It may best be described as Lean LaunchPad Light. We are using much of the Lean methodology for our curriculum, but I also include key career development skills.

Alexander Osterwalder’s Business Model Generation and Steve’s Udacity Lean LaunchPad Lectures are required reading/viewing. Additionally I recommend but I do not require: Startup Owner’s Manual, Founders at Work and the Founders Films clips. I also recommend students keep a personal journal for mind-mapping and brainstorming business ideas. The first exercise we do in class is Dave McClure’s Half-Baked game (but students also have to use the Value Proposition & the Customer Segment.) This exercise demonstrates the need to be flexible in business.

Additional outside readings includes a number of excellent book summaries ranging from Tina Seelig’s InGenius, Tom Kelley’s 10 Faces of Innovation, Anthony Tjan’s Hearts, Smarts Guts and Luck and Dan Pink’s To Sell is Human.

Steve’s insight and inspiration during the Lean LaunchPad Educators Program was extraordinary. I am enormously grateful for the opportunity to learn from the legend and exchange ideas with the best in the field. I appreciate Steve’s continued advice as I do my best to carry the Lean LaunchPad flag in Delaware.

Filed under: Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

January 30, 2013

Qualcomm’s Corporate Entrepreneurship Program – Lessons Learned (Part 2)

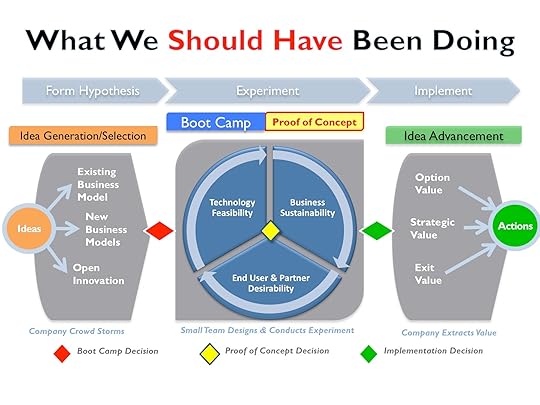

I ran into Ricardo Dos Santos and his amazing Qualcomm Venture Fest a few years ago and was astonished with its breath and depth. From that day on, when I got asked about which corporate innovation program had the best process for idea selection, I started my list with Qualcomm.

This is part 2 of Ricardo’s “post mortem” of the life and death of Qualcomm’s corporate entrepreneurship program. Part 1 outlining the program is here. Read it first.

———

What Qualcomm corporate innovation challenges remained?

Ironically, our very success in creating radically new product and business ideas ran headlong into cultural and structural issues as well as our entrenched R&D driven innovation model:

Cultural Issues: Managers approved their employees sign-up for the bootcamp, but became concerned with the open-ended decision timelines that followed for most of the radical ideas. Employees had a different concern – they simply wanted more clarity on how to continue to be involved, since formal rules of engagement ended with the bootcamp.

Structural Issues: Most of the radical ideas coming out of the 3-month bootcamp possessed a high hypotheses-to-facts ratio. When the teams exited the bootcamp, however, it was unclear which existing business unit should evaluate them. Since there weren’t corporate resource for further evaluation, (one of our programs’ constraints was not to create new permanent infrastructures for implementation,) we had no choice but to assign the idea to a business unit and ask them to perform due diligence the best they could. (By definition, before they had a chance to fully buy into the idea and the team).

With hindsight we should have had “proof of concepts” tested in a corporate center (think ‘pop-up incubator’) where they would do extensive Customer Discovery. We should had done this before assigning the teams to a particular business unit (or had the ability to create a new business unit, or spin the team out of the company).

The last year of the program, we tried to solve this problem by requiring that the top 20 teams first seek a business unit sponsor before being admitted into the bootcamp (and we raised a $5 million fund from the BUs earmarked for initial implementation ($250K/team.) Ironically this drew criticism from some execs fearing we might have missed the more radical, out-of-the box ideas!

Entrenched Innovation Model Issues: Qualcomm’s existing innovation model – wireless products were created in the R&D lab and then handed over to existing business units for commercialization – was wildly successful in the existing wireless and mobile space. Venture Fest was not integral to their success. Venture Fest was about proposing new ventures, sometimes outside the wireless realm, by stressing new business models, design and open innovation thinking, not proposing new R&D projects.These non-technical ideas ran counter to the company’s existing R&D, lab-to-market model that built on top of our internally generated intellectual property. The result was that we couldn’t find internal homes for what would have been great projects or spinouts. (Eventually Qualcomm did create a corporate incubator to handle projects beyond the scope of traditional R&D, yet too early to hand-off to existing business unit).

We were asking the company’s R&D leads, the de-facto innovation leaders, who had an existing R&D process that served the company extremely well, to adopt our odd-ball projects. Doing so meant they would have to take risks for IP acquisition and customer/market risks outside their experience or comfort zone. So when we asked them to embrace these new product ideas, we ran into a wall of (justified) skepticism. Therefore a major error in setting up our corporate innovation program was our lack of understanding how disruptive it would be to the current innovation model and to the executives who ran the R&D Labs.

What could have been done differently?

We had relative success flowing a good portion of ideas from the bootcamp into the business and R&D units for full adoption, partial implementation or strategic learning purposes, but it was a turbulent affair. With hindsight, there were four strategic errors and several tactical ones:

1) We should have recruited high level executive champions for the program (besides the CEO). They could have helped us anticipate and solve organizational challenges and agree on how we planned to manage the risks.

2) We should have had buy-in about the value of disruptive new business models, design and open innovation thinking.

3) We unknowingly set up an organizational conflict on day one. We were prematurely pushing some of the teams in the business units. The ‘elephant in the room’ was that the Venture Fest program didn’t fit smoothly with the BU’s readiness for dealing with unexpected ‘bottoms up’ innovation, in a quarterly- centric, execution environment.

4) Our largest customer should have been the R&D units, but the reality was that we never sold them that the company could benefit by exploring multiple innovation models to reduce the risks of disruption – we had taken this for granted and met resistance we were unprepared to handle.

Qualcomm Lessons Learned

The Venture Fest program truly was ground breaking. Yet we never told anyone outside the company about it. We should have been sharing what we built with the leading business press, highlighting the vision and support of the program’s originator, the CEO.

We should have asked for a broader innovation time off and incentive policy for employees, managers, and executives. Entrepreneurial employees must have clear opportunities to continue to own ideas through any stage of funding – that’s the major incentive they seek. Managers and execs should be incentivized for accommodating employee involvement and funding valuable experiments.

We needed a for a Proof of Concept center. Radical ideas seldom had an obvious home immediately following the bootcamp. We lacked a formal center that could help facilitate further experiments before determining an implementation path. A Proof of Concept center, which is not the same as a full-fledged incubator, would also be responsible to develop a companywide core competence in business model and open innovation design and a VC-like, staged-risk funding decision criteria for new market opportunities.

It’s hard to get ideas outside of a company’s current business model get traction (given that the projects have to get buy-in from operating execs) – encouraging spin-offs is a tactic worth considering to keep the ideas flowing.

Epilogue

The program became large enough that it came time to choose between expanding the program or making it more technology focused and closely tied to corporate R&D. In the end my time in the sun eventually ran out.

I had the greatest learning experience of my life running Qualcomm’s corporate entrepreneurship program and met amazingly brave and gracious employees with whom I’ve made a lifetime connection. I earnestly believe that large corporations should emulate Lean Startups (Business model design, Customer Development and Agile Engineering.) I am now eager to share and discuss the insights with other practitioners of innovation – I can be reached at ricardo_dossantos@alum.mit.edu

Lessons Learned

We now have the tools to build successful corporate entrepreneurship programs.

However, they need to match a top-level (board, CEO, exec staff) agreement on strategy and structure.

If I were starting a corporate innovation program today, I’d use the Lean LaunchPad classes as the starting framework.

Developing a program to generate new ideas is the easy part. It gets really tough when these projects are launched and have to fight for survival against current corporate business models.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

January 28, 2013

Designing a Corporate Entrepreneurship Program – A Qualcomm Case Study (part 1 of 2)

I ran into Ricardo Dos Santos and his amazing Qualcomm Venture Fest a few years ago and was astonished with its breath and depth. From that day on, when I got asked about which corporate innovation program had the best process for idea selection, I started my list with Qualcomm.

This is Ricardo’s “post mortem” account of the life and death of a corporate entrepreneurship program. Part 1 outlining the program is here. Part 2 describing the challenges and “lessons learned” will follow.

———-

The origin

In 2006, as a new employee of the Fortune 100 provider of wireless technology and services, San Diego’s Qualcomm, I volunteered to salvage a fledging idea management system (fancy term for an online suggestion box) by turning into a comprehensive corporate entrepreneurship program.

Qualcomm’s visionary CEO, Paul Jacobs, wanted to use internal Qualcomm ideas to find breakthrough innovation that could be turned into products, (not simply a suggestion box for creative thoughts or improving sustaining innovation.) He gave my innovation team free reign on designing a new employee innovation program. His only request was that we keep two of the original program’s goals:

1. The program had to remain fully open to employees from all divisions.

2. The ideas were to be implemented by existing business or R&D units – i.e., no need to create new permanent infrastructures for innovation.

And he added a third goal that would ensure his greater involvement and support going forward.

3. The program had to have an efficient mechanism to bubble-up the best ideas (and their champions) to the timely attention of the top executive team.

The design challenge

We wanted to transform our simple online suggestion box into a program that encouraged employees to behave like intrapreneurs (and their managers and executives as enablers). Our challenge was to design a program that could:

Teach participants on how to turn their ideas into fundable experiments.

Educate employees who submit ideas that in corporations, there is no magic innovation leprechaun at the end of the rainbow that turn their unsolicited suggestions into pots of gold – they themselves had to take ownership and fight for their ideas.

All while keeping in mind that employees, managers and executives have day jobs – so how could we ask them to spend significant time on new ideas while not sacrificing their present obligations?

Thus began our search for a program that would properly balance the focus on the present with the need to increase our options for the future.

Qualcomm Innovation Process

Qualcomm’s Corporate Entrepreneurship Program – Venture Fest

In 2006 we searched outside of Qualcomm for other similar entrepreneurship programs where participants also had to balance other obligations. We realized this mechanism had been occurring for years at University’s startup competitions, such as the MIT 100K Accelerate Contest. In these competitions, multidisciplinary self-forming teams of students work part time to pitch new companies. The program we implemented inside of Qualcomm ended up being very similar. We dubbed the program Qualcomm’s Venture Fest and the process, “Collective Entrepreneurship”, a three-phase program combining crowdsourcing with entrepreneurial techniques for startup creation.

The first phase of the program leveraged the idea management system to collect a large number of competing entries then ultimately down-selected to the top 10-20 concepts with the most breakthrough potential, according to peer and expert reviews.

Qualcomm Venture Fest

The second phase, and heart of the program, was a three-month, part time bootcamp that would prepare idea champions for the internal funding battle that followed. The bootcamp requested that participants do what entrepreneurs do before requesting seed funding – Discover, Network and Accelerate. (In hindsight we were having our employees get out of the building to talk to customers, build prototypes and generate partner interest – essentially doing Customer Discovery years before Steve Blank taught his Lean LaunchPad class at Stanford and the National Science Foundation!). Our employees faced the typical impediments to corporate entrepreneurship – lack of employee time, skills, connections, pre-seed money, and official sources to discuss and manage the risk/rewards tradeoffs of sticking your neck-out. So our program staff built a support system of contextual education, mentorship, micro-funding, and hands-on coaching.

Finally, the third phase of the program, implementation, began with the top team’s pitches to the C-level executive team, which determined the competition winners, prize money and directed other promising teams to target business unit sponsors. Our program staff facilitated the handoff and disseminated the value extracted from any funded experiments, including future option, strategic and exit value.

In retrospect we designed something akin to a startup accelerator, the Lean LaunchPad classes or the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps, although none of these existed in 2006.

What went right?

We had C-level support. The CEO of the company embraced the program and supported the process, especially since it brought novel and thought provoking ideas to his executive team’s attention.

The program steadily generated healthy interest from Qualcomm employees – submissions grew from 82 in the first year to over 500 in its fifth and final year. Several ideas were fully or partially implemented, (with hundreds of millions of USD invested), with a couple of genuine breakthrough successes, and hundreds of related patents were filed. Employees reported noticeable gains in entrepreneurial skills and attitude, and the CEO seemed happy with how his baby was being raised.

—-

Part 2 – challenges and lessons learned – to follow.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Teaching

January 22, 2013

Back to Colombia: Vive La Revolución Emprendedora!

My co-author and business Partner Bob Dorf spends much of his time traveling the world teaching countries and companies how to run the Lean LaunchPad program. He’s back to Bogota, Colombia this week for round two.

—–

Back to Colombia: Vive La Revolución Emprendedora!

Lean LaunchPad Colombia starts again today in Bogota with 25 more teams of tech entrepreneurs and at 25 mentors from the country’s universities, incubators, and chambers of commerce. The program is funded by the Colombian government and modeled after the NSF Innovation-Corps program created and built by my partner and co-author Steve Blank.

In this second cohort, Startup teams were selected from over 100 applicants in Colombia by SENA, a quasi-government organization that provides tech support, prototype labs, and mentoring to Colombian entrepreneurs. SENA and the Colombian Ministry of IT and Innovation both invest heavily to create jobs for the many skilled, educated and underemployed citizens. Other than the NSF Innovation-Corps program in the U.S., this may well be the most ambitious government-sponsored startup catalyst effort on the globe.

SENA and the Colombian Ministry of IT: targeting 15,000 young entrepreneurs

The Ministry hopes to supports to more than 15,000 entrepreneurs who have applied for help thus far, and to do it in varying levels of on- and off-line intensity. The hands-on Lean LaunchPad program offers the most intense support of all. In cohort one, 25 teams chosen from a field of 100+, worked fulltime for eight weeks to take their ideas from a “cocktail napkin” business idea to a viable, scalable business model.

While the Ministry would be glad to help develop the next Facebook or Google, the initial first step is more reasonable — get startups to breakeven or better while employing 15, 20, or more Colombians . Those who don’t make it into the class are offered a variety of on- and off-line tools, including government-funded translations of Steve’s nine-part Udacity.com Customer Development lectures, excerpts from the Startup Owner’s Manual in Spanish, and they’ve translated a long list of Code Academy courses and other tools as well. The goal is simple: to extend the reach of Customer Development and tech training far beyond those whose teams and business models earn them seats in the classroom.

Colombia needs to be ambitious to succeed in this effort, and I’m honored and pleased to be helping to drive it. The emerging economy faces three critical entrepreneurial challenges. First, there’s virtually no seed or angel investment capital, since affluent Colombian investors are highly risk-averse and put their money into real estate and established companies as a rule. Second, technology education is more skill-based, graduating lots of smart coders and IT managers, but not a lot of true development visionaries. And the academic community, while strong, still teaches traditional the business plan approach to startups, rather than Customer Development, so ideas have typically evolved far more slowly.

The first 8-week Lean LaunchPad Colombia program

We held the first cohort of 25 teams in Oct 2012. Amazingly by the end of the program’s eighth week, 8 of the 25 teams had customer revenue. One startup, Vanitech, generated revenue from more than 315 consumers in eight weeks, while a software prototyping startup called EZ DEV closed its first deal and had contracts out for two more. And while the startup ideas ranged from the pedestrian to the very brave (digital preventive healthcare, for example), the common thread was an intense passion for creating a business that would create lucrative jobs for the founders and their fellow Colombians.

This LeanLaunchPad simultaneously trains entrepreneurs and coaches to guide them. Each cohort started with a day of coach training. Then the coaches joined their teams for three days of business model development, feedback, and training. When I headed home, teams fanned out across Colombia to “get out of the building” to validate their ideas. They meet at least weekly with their coaches to process their learning and iterate their business models.

I returned twice more to Colombia for this first cohort: at the midpoint of the 8-week class to work with the coaches and teams, and at the end for the “Lessons Learned day.” At the Lessons Learned day, the ten teams pitched to an audience of 650, including investors and the Minister and Vice-Minister of IT. The presentations were a real eye-opener to Colombian investors. The hundreds of customer interactions made each team made their presentations credible. The difference between startups powered by Customer Development and those built the “old way” was on full display. Another unintended consequence of the class is that, we’re effecting a “technology transfer” by training the coaches, who are starting to run Lean LaunchPad programs for additional teams in smaller cities in Colombia. Overall, it’s one heck of an ambitious program and it’s starting to catch fire.

Three incredibly entrepreneurial government employees (usually quite an oxymoron in any country) conceived and drive this program, working nearly 7×24 and as hard as any Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, in their eight month old “startup,” the apps.co program. Program leader Claudia Obando and her two star lieutenants—Nayib Abdala and Camilo Zamora—have worked with us to lay every building block in the solid foundation Lean LaunchPad is providing for Colombia.

And so here I am back in Colombia as we launch this next, more cohort on its eight-week sprint, join apps.co in saying Viva Colombia!”

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

January 21, 2013

Don’t Underestimate the Undergraduates

Jim Hornthal splits his time between venture capital, entrepreneurship and education. Jim has founded six companies, including Preview Travel, one of the first online travel agencies, which went public in 1997 and subsequently merged to create Travelocity.com as an independent company. Today he is the co-founder and Chairman of Triporati, LaunchPad Central and Zignal Labs.

Jim co-taught classes with me at U.C. Berkeley, joined me in launching the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps class and now has been teaching his own Lean LaunchPad class at Princeton. I asked Jim to share what he learned in teaching the Lean LaunchPad class to undergraduates. Here’s what Jim had to say…

———

Don’t Underestimate the Undergraduates

Last fall, I began teaching the Lean LaunchPad course at Princeton (EGR 495: Special Topics in Entrepreneurship) with four teams of undergraduates (ok, there were a few engineering grad students in the mix), a brave first-time LLP co-teacher (Cal Simmons), and a talented and dedicated teaching assistant (Ismaiel Yakub).

This would be my fourth voyage in the captain’s cabin of the SS LaunchPad. My prior journeys were spearheaded by the founder of this school of teaching, Steve Blank. Our teams were from Berkeley/Columbia EMBA, the Haas/Berkeley Engineering graduate student ranks, and as a co-teacher at Stanford for the National Science Foundation I-Corps program.

This would be the first time the course was taught in an undergraduate environment, and the first time we would use Steve’s Udacity lectures to “flip” the classroom. This approach helped in several ways. First, it allowed us to use the classroom time to dive deep into each team’s discovery narrative as it related to that week’s section of the business model canvas. Second, it allowed the teams mentors to “follow along”, since they were all first timers to the Lean LaunchPad approach. I believe this ability to synchronize the teams with their mentors added a lot to the successful outcomes of each team’s process. Mentors also got a weekly email of things to look out for from their teams. These notes were derived (read: stolen) from the Lean LaunchPad Educator’s guide. Sharing the week-by-week highlights was a great way to focus the mentor’s attention on what we were trying to accomplish at the team level.

Challenges

As a fall course being taught for the first time, there were additional challenges. The first was selecting the students who could take the class. Last spring, the course was listed for students, requiring an application AND an in-person interview. I wanted to make sure that students understood the significant amount of work outside the classroom that this would entail, and did not want to have a significant drop/add turnover once the teams had begun their work in the fall.

We had over 55 students apply, and based on a careful read of their applications, all were eager and capable. I flew out to Princeton to conduct 5 minute “speed dating” interviews with all of them. I wanted to assess their flexibility, willingness to accept direct, sometimes harsh input and criticism, and to get a sense of their resiliency in the face of almost certain failure. That ‘cut’ still left me with over 40 potential thick-skinned budding entrepreneurs.

I next cut out any students for whom this would be one of five courses. I also eliminated rising all rising sophomores, and got a list of 20 that were invited to the class.

In the fall, 18 showed up, and we then had to address another flaw with a first-time course offered in the fall to undergraduates. We had no pre-formed teams to work with. Fortunately, the Princeton academic calendar affords 13 weeks, and the Lean LaunchPad process takes 10, so we had a few weeks in the beginning to run a modified “Startup Weekend” process where students could pitch their ideas to their peers, and the class would rank vote their top 3 choices from the 15 options (some students had more than one idea, and a few chose to work on the ideas of others, so they did not ‘pitch’ on their own).

When the dust settled, we had 4 teams ready to start, and in the context of the overview lecture and discussion from week one, each team was connected to their mentor (most interactions were via Skype), and we were ready to take off for parts unknown.

A huge concern of mine going in was wondering at what level could these students absorb the material? There was little-to-no practical work experience (one or two summer jobs seems potentially useful, but in the whole, this was virgin territory for nearly every student in the class).

Can you teach the Lean LaunchPad to Undergraduates? Heck Yes!

What did we experience? Compared to all of the other teams I have taught in my three other “performances”, I can say categorically that these students were the most fearless, adaptable, and relentless of any of the other cohorts, taken as a whole. One inadvertent mistake that we made (and were able to correct mid-course), was that the students took the “get out of the classroom” mandate too literally. The first month of customer discovery for most of their initiatives relied too much on conversations within the Princeton University community itself (fellow students, faculty and admin). This inadvertent filter created the risk of generating false positive (and false negative) results to a lot of the preliminary hypothesis testing that is a key part of an early Lean LaunchPad experience — searching to find a solid product-market fit.

Maybe it is because they are all “professional students”, or that they were particularly motivated to have a “real world” class experience for a change, they all devoured the work, their peer-to-peer interactions were exceptional, every week they raised the bar for themselves and each other, and by the end of the class, the teams averaged nearly 200 “customer discovery” engagements (this metric refers to customer interviews + business model canvas entries (and deletions), mentor engagements and faculty engagements. We were able to track their progress with the LaunchPad Central platform (disclosure: Steve and I are investors), which made keeping up with all of the chaos a more manageable task for faculty, mentors and teams alike.

Rather than try and tell you more about their amazing journeys, I invite you to explore the teams final videos and slides for yourselves. I think you will see the work of some talented and determined entrepreneurs who have honed their customer discovery and customer development skills to an impressive level. Don’t underestimate the undergraduates; in fact, the potential dividends of their academic prowess, augmented by their hard fought real-world experience makes them all formidable opponents. Hopefully none of you will have to face off against any of them in the marketplace. If you do, my bet is on these talented, motivated and well-prepared undergraduates. Let the games begin …

Class goals:

“Acquire real-world experience outside the classroom, working as a team to learn the skills of customer discovery and customer development; understand the business model canvas as a tool and learn how to create fast, cost-effective tests for each of their hypothesis along the way, and in the process acquire “x-ray” vision to see through business pitches and be able to ask the questions that matter.”

Lessons Learned

The student interview process and selection is critical

Undergraduates can handle the class

Clarify that “get out of the classroom” means “get off the campus”

Students bounce back from the direct and sometimes tough live feedback

Align and train mentors to embrace customer development

Go for it!

Team Final Videos and Presentations

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

January 14, 2013

The Endless Frontier: U.S. Science and National Industrial Policy (part 1)

The U.S. has spent the last 70 years making massive investments in basic and applied research. Government funding of research started in World War II driven by the needs of the military for weapon systems to defeat Germany and Japan. Post WWII the responsibility for investing in research split between agencies focused on weapons development and space exploration (being completely customer-driven) and other agencies charted to fund basic and applied research in science and medicine (being driven by peer-review.)

The irony is that while the U.S. government has had a robust national science and technology policy, it lacks a national industrial policy; leaving that to private capital. This approach was successful when U.S. industry was aligned with manufacturing in the U.S., but became much less so in the last decade when the bottom-line drove industries offshore.

In lieu of the U.S. government’s role in setting investment policy, venture capital has set the direction for what new industries attract capital.

This series of blog posts is my attempt to understand how science and technology policy in the U.S. began, where the money goes and how it has affected innovation and entrepreneurship. In future posts I’ll offer some observations how we might rethink U.S. Science and National Industrial Policy as we face the realities of China and global competition.

Office of Scientific Research and Development – Scientists Against Time

As World War II approached, Vannevar Bush, the ex-dean of engineering at MIT, single-handledly reengineered the U.S. governments approach to science and warfare. Bush predicted that World War II would be the first war won or lost on the basis of advanced technology. In a major break from the past, Bush believed that scientists from academia could develop weapons faster and better if scientists were kept out of the military and instead worked in civilian-run weapons labs. There they would be tasked to develop military weapons systems and solve military problems to defeat Germany and Japan. (The weapons were then manufactured in volume by U.S. corporations.)

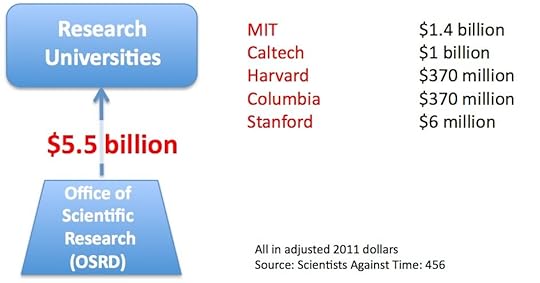

In 1940 Bush proposed this idea to President Roosevelt who agreed and appointed Bush as head, which was first called the National Defense Research Committee and then in 1941 the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD).

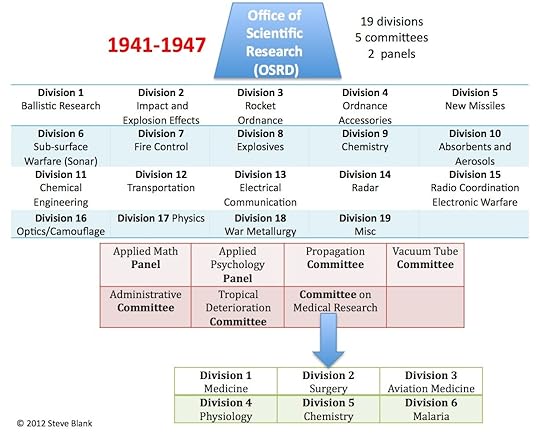

OSRD divided the wartime work into 19 “divisions”, 5 “committees,” and 2 “panels,” each solving a unique part of the military war effort. These efforts spanned an enormous range of tasks – the development of advanced electronics; radar, rockets, sonar, new weapons like proximity fuse, Napalm, the Bazooka and new drugs such as penicillin and cures for malaria.

The civilian scientists who headed the lab’s divisions, committees and panels were given wide autonomy to determine how to accomplish their tasks and organize their labs. Nearly 10,000 scientists and engineers received draft deferments to work in these labs.

One OSRD project – the Manhattan Project which led to the development of the atomic bomb – was so secret and important that it was spun off as a separate program. The University of California managed research and development of the bomb design lab at Los Alamos while the US Army managed the Los Alamos facilities and the overall administration of the project. The material to make the bombs – Plutonium and Uranium 235 – were made by civilian contractors at Hanford Washington and Oak Ridge Tennessee.

OSRD was essentially a wartime U.S. Department of Research and Development. Its director, Vannever Bush became in all but name the first presidential science advisor. Think of the OSRD as a combination of all of today’s U.S. national research organizations – the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institute of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Department of Energy (DOE) and a good part of the Department of Defense (DOD) research organizations – all rolled into one uber wartime research organization.

OSRD’s impact on the war effort and the policy for technology was evident by the advanced weapons its labs developed, but its unintended consequence was the impact on American research universities and the U.S. economy that’s still being felt today.

National Funding of University Research

Universities were started with a mission to preserve and disseminate knowledge. By the late 19th century, U.S. universities added scientific and engineering research to their mission. However, prior to World War II corporations not universities did most of the research and development in the United States. Private companies spent 68% of U.S. R&D dollars while the U.S. Government spent 20% and universities and colleges accounted just for 9%, with most of this coming via endowments or foundations.

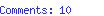

Before World War II, the U.S. government provided almost no funding for research inside universities. But with the war, almost overnight, government funding for U.S. universities skyrocketed. From 1941-1945, the OSRD spent $450 million dollars (equivalent to $5.5 billion today) on university research. MIT received $117 million ($1.4 billion in today’s dollars), Caltech $83 million (~$1 billion), Harvard and Columbia ~$30 million ($370 million.) Stanford was near the bottom of the list receiving $500,000 (~$6 million). While this was an enormous sum of money for universities, it’s worth putting in perspective that ~$2 billion was spent on the Manhattan project (equivalent to ~$25 billion today.)

World War II and OSRD funding permanently changed American research universities. By the time the war was over, almost 75% of government research and development dollars would be spent inside Universities. This tidal wave of research funds provided by the war would:

Establish a permanent role for U.S. government funding of university research, both basic and applied

Establish the U.S. government – not industry, foundations or internal funds – as the primary source of University research dollars

Establish a role for government funding for military weapons research inside of U.S. universities (See the blog posts on the Secret History of Silicon Valley here, and for a story about one of the University weapons labs here.)

Make U.S. universities a magnet for researchers from around the world

Give the U.S. the undisputed lead in a technology and innovation driven economy – until the rise of China.

The U.S. Nationalizes Research

As the war drew to a close, university scientists wanted the money to continue to flow but also wanted to end the government’s control over the content of research. That was the aim of Vannevar Bush’s 1945 report, Science: the Endless Frontier. Bush’s wartime experience convinced him that the U.S. should have a policy for science. His proposal was to create a single federal agency – the National Research Foundation – responsible for funding basic research in all areas, from medicine to weapons systems. He proposed that civilian scientists would run this agency in an equal partnership with government. The agency would have no laboratories of its own, but would instead contract research to university scientists who would be responsible for all basic and applied science research.

But it was not to be. After five years of post-war political infighting (1945-1950), the U.S. split up the functions of the OSRD. The military hated that civilians were in charge of weapons development. In 1946 responsibility for nuclear weapons went to the new Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). In 1947, responsibility for basic weapons systems research went to the Department of Defense (DOD). Medical researchers who had already had a pre-war National Institutes of Health chafed under the OSRD that lumped their medical research with radar and electronics, and lobbied to be once again associated with the NIH. In 1947 the responsibility for all U.S. biomedical and health research went back to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Each of these independent research organizations would support a mix of basic and applied research as well as product development.

Finally in 1950, what was left of Vannevar Bush’s original vision – government support of basic science research in U.S. universities – became the charter of the National Science Foundation (NSF). (Basic research is science performed to find general physical and natural laws and to push back the frontiers of fundamental understanding. It’s done without thought of specific applications towards processes or products in mind. Applied research is systematic study to gain knowledge or understanding with specific products in mind.)

Despite the failure of Bush’s vision of a unified national research organization, government funds for university research would accelerate during the Cold War.

Coming in Part 2 – Cold War science and Cold War universities.

Lessons Learned

Large scale federal funding for U.S. science research started with the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) in 1940

Large scale federal funding for American research universities began with OSRD in 1940

In exchange for federal science funding, universities became partners in weapons systems research and development

Filed under: Science and Industrial Policy, Secret History of Silicon Valley, Teaching, Technology

December 26, 2012

Завзятість – Tenacity: How I Spent A Year One Night in Kiev

This July I thought I had set the record for tenacity in my age group. Go ahead and take a moment to read the post, it’s short. I reminded my Startup Owners Manual co-author Bob Dorf this is how entrepreneurs played the game, blah, blah, blah.

As usual Bob did one better. Here’s a guest post on what happened to him in the Ukraine.

—–

Usually when you teach entrepreneurship, one of the key things you teach is tenacity, a vital characteristic of great entrepreneurs. Only rarely does the teaching itself require tenacity, as it did late last month in Kiev, Ukraine.

Following two days with a dozen startups at a brand-new incubator in Kiev called “Happy Farm,” it was time to head to my next stop: Skolkovo, the private Moscow business school formed to bring Silicon Valley-quality training to young Russian entrepreneurs. I was headed to my second Lean LaunchPad launch, excited that the first one in June had led to four funded startups raising some $2-million from Russian VC’s.

Ukraine was magnificent. Kiev is a beautiful city and Happy Farm Training Director Elena Kalibaba led me on a walking tour. Then it was on to a series of workshops and one-on-one coaching sessions with ten terrific startup teams, plus a press conference with Forbes Ukraine and others. When it was over, Happy Farm CEO and founder (and serial entrepreneur) Anna Degtereva drove me to the airport and–for some strange reason–escorted me to the gate.

I Spent A Year One Night in Kiev

As I approached the check-in desk, a very gruff Ukrainian customs official looked at my visa to Russia and said, “You cannot travel. Your visa to Russia has already been used. No exceptions.” He said nothing else in English, and waved me out of the line.

A mad scramble uncovered the problem: when I had changed planes for Kiev back in Moscow they stamped my visa as “entered” so that counted as “visiting” Russia. As far as Ukrainian customs was concerned I didn’t have a valid visa to enter Russia therefore I couldn’t get on my plane. No charm or magic worked at all with airport customs, and we were told in no uncertain terms that Bob Dorf would be living in Kiev for two weeks, absent miracles that seldom happen in government bureaucracies, at home or in Ukraine, for sure.

The problem was that I had 25 founders from all over the Russian republics expecting me to teach a Lean LaunchPad class 12 hours later in Moscow. And then I was heading to Paris and Bogota to teach as well. Oops. Not if I had to spend two weeks in the Ukraine applying for a new Russian visa!

We dashed off from the Kiev airport to the Russian consulate in hopes of sorting it out in two hours rather than two weeks. While on the way, we called the embassy at 12:55 and found out that the Embassy closes at 13:00 on Fridays, and we were 30 minutes away. And I don’t even like borscht, a prime Ukrainian delicacy, nor did I know how the “Bob Dorf world tour” would continue.

Four entrepreneurs in a car

Was this time to give up? Of course not. Four entrepreneurs in a car in Kiev means three cell phones buzzing in different directions in Russian and me as the non Russian-speaker on my iPad looking at travel sites for the next flight, just in case I could get a visa. We went to the consulate anyway, where two armed guards right out of your favorite spy movie (fat, grumpy, unshaven and did I say grumpy?) barred the door. After rapid-fire begging in Russian, a phone finally call got a functionary out to basically shoo us away. “Visa processing takes two weeks, and that would start Monday, since the visa office is now closed. The Professor can go home to America, but can not go from here to Russia.” Visions of stealth border crossings or—perhaps even worse—a ten-hour Skype talk with my Moscow students—played over and over again.

While the thoughts of going back to the U.S. for a weekend at home with my long-lost wife Fran were lovely, the thought of disappointing 25 students the next day and 50 more two days later in Bogota weren’t fun. I immensely enjoyed my last lectures at Skolkovo and was eager to do it again.

So we started an international incident of sorts

First, the truly entrepreneurial and unstoppable Happy Farmer, Anna, somehow in five phone calls got through to the Foreign Minister of Ukraine, told him the story, begged for his help. She did this through a friend (how everything happens in Ukraine, of course) who served as one of his deputies. “I will talk to him at four pm and he will call the Russians,” she said, which offered only nominal relief: the last flight out was at 7 pm, and there was no firm commitment that anything good would happen.

At the same time, on the Russian side of the border, Skolkovo’s equally tenacious Startups Project Director, Lawrence Wright, went to work, calling the Russian foreign office and imploring them to call the Ukrainian embassy and tell them “let Dorf out.” When they agreed to consider breaking every rule in the 40-pound Russian rulebook, the fun began.

The Ukrainian solution to all this, while we paced for two hours to see if anybody heard our cries: “lets go to lunch and have a drink.” In perhaps one of four times in my entire life, I was actually unable to eat. The thought of jumping barbed wire fences, pursued by Cossacks, was quickly looming as my only choice for an on-time performance launching the LaunchPad. Meanwhile, something clicked. Somebody got to somebody, and suddenly the Russian Consul himself, boss of the entire place, headed back to—or was sent back to–the office himself to personally produce a visa for Bob Dorf in one hour, not two weeks.

We were given less than an hour to find wifi and download the 20-page visa application in the backseat of an SUV. Needed to have the original, not a copy, of the new Skolkovo “invitation letter” physically in my hand. Scrambled to get a passport photo and a printer to print out the application. Done, back to the Consulate at Indy 500 speed!

Somehow it worked. If Anna and her team are as good at running over hot coals and through brick walls with their startups as they were with my visa, watch for lots of great companies emerging from the Happy Farm. As for me, I was sure I was headed to the funny farm. By nine I was heading to Moscow. Six hours of fun aggravation, five and a half of which had me absolutely sure we were opening a branch of K&S Ranch in Kiev.

But the best part of the adventure is that I now had a better tenacity story than Steve. Beat this one!

Filed under: Family/Career/Culture

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers