Steve Blank's Blog, page 47

July 30, 2012

Lying on your resume

It’s not the crime that gets you, it’s the coverup.

Richard Nixon and Watergate

Getting asked by reporter about where I went to school made me remember the day I had to choose whether to lie on my resume.

I Badly Want the Job

When I got my first job in Silicon Valley it was through serendipity (my part) and desperation (on the part of my first employer.) I really didn’t have much of a resume – four years in the Air Force, building a scram system for a nuclear reactor, a startup in Ann Arbor Michigan but not much else.

It was at my second startup in Silicon Valley that my life and career took an interesting turn. A recruiter found me, now in product marketing and wanted to introduce me to a hot startup making something called a workstation. “This is a technology-driven company and your background sounds great. Why don’t you send me a resume and I’ll pass it on.” A few days later I got a call back from the recruiter. “Steve, you left off your education. Where did you go to school?”

“I never finished college,” I said.

There was a long silence on the other end of the phone. “Steve, the VP of Sales and Marketing previously ran their engineering department. He was a professor of computer science at Harvard and his last job was running the Advanced Systems Division at Xerox PARC. Most of the sales force were previously design engineers. I can’t present a candidate without a college degree. Why don’t you make something up.”

I still remember the exact instant of the conversation. In that moment I realized I had a choice. But I had no idea how profound, important and lasting it would be. It would have been really easy to lie, and what the heck the recruiter was telling me to do so. And he was telling me that, “no one checks education anyway.” (This is long before the days of the net.)

My Updated Resume

I told him I’d think about it. And I did for a long while. After a few days I sent him my updated resume and he passed it on to Convergent Technologies. Soon after I was called into an interview with the company. I can barely recall the other people I met, (my potential boss the VP of Marketing, interviews with various engineers, etc.) but I’ll never forget the interview with Ben Wegbreit, the VP of Sales and Marketing.

Ben held up my resume and said, “You know you’re here interviewing because I’ve never seen a resume like this. You don’t have any college listed and there’s no education section. You put “Mensa” here,” – pointing to the part where education normally goes. “Why?” I looked back at him and said, “I thought Mensa might get your attention.”

Ben just stared at me for an uncomfortable amount of time. Then he abruptly said, “Tell me what you did in your previous companies.” I thought this was going to be a story-telling interview like the others. But instead the minute I said, “my first startup used CATV coax to implement a local-area network for process control systems (which 35 years ago pre-Ethernet and TCP/IP was pretty cutting edge.) Ben said, “why don’t you go to the whiteboard and draw the system diagram for me.” Do what? Draw it?? I dug deep and spent 30 minutes diagramming trying remember headend’s, upstream and downstream frequencies, amplifiers, etc. With Ben peppering me with questions I could barely keep up. And there was a bunch of empty spaces where I couldn’t remember some of the detail. When I was done explaining it I headed for the chair, but Ben stopped me.

“As long as you’re a the whiteboard, why don’t we go through the other two companies you were at.” I couldn’t believe it, I was already mentally exhausted but we spent another half hour with me drawing diagrams and Ben asking questions. First talking about what I had taught at ESL – (as carefully as I could.) Finally, we talked about Zilog microprocessors, making me draw the architecture (easy because I had taught it) and some sample system designs (harder.)

Finally I got to sit down. Ben looked at me for a long while not saying a word. Then he stood up and opened the door signaling me to leave, shook my hand and said, “Thanks for coming in.” WTF? That’s it?? Did I get the job or not?

That evening I got a call from the recruiter. “Ben loved you. In fact he had to convince the VP of Marketing who didn’t want to hire you. Congratulations.”

Epilogue

Three and a half years later Convergent was now a public company and I was a Vice President of Marketing working for Ben. Ben ended up as my mentor at Convergent (and for the rest of my career), my peer at Ardent and my partner and co-founder at Epiphany. I would never use Mensa again on my resume and my education section would always be empty.

But every time I read about an executive who got caught in a resume scandal I remember the moment I had to choose.

Lessons Learned

You will be faced with ethical dilemmas your entire career

Taking the wrong path is most often the easiest choice

These choices will seem like trivial and inconsequential shortcuts – at the time

Some of them will have lasting consequences

It’s not the lie that will catch up with you, it’s the coverup

Choose wisely

Filed under: Convergent Technologies, E.piphany, ESL, Family/Career/Culture, Zilog

July 24, 2012

Unrequited Love

If there’s only one passionate party in a relationship it’s unrequited love.

Here’s how I learned it the hard way.

The Dartmouth Football Team

After Rocket Science I took some time off and consulted for the very VC’s who lost lots of money on the company. The VC’s suggested I should spend a day at Onyx Software, an early pioneer in Sales Automation in Seattle.

In my first meeting with the Onyx I was a bit nonplussed when the management team started trickling into their boardroom. Their VP of Sales was about 6’ 3” and seemed to be almost as wide. Next two more of their execs walked in each looking about 6’ 5” and it seemed they had to turn sideways to get through the door. They all looked like they could have gotten jobs as bouncers at a nightclub. I remember thinking, there’s no way their CEO can be any taller – he’s probably 5’ 2”. Wrong. Brent Frei, the Onyx CEO walks in and he looked about 6’ 8’ and something told me he could tear telephone books in half.

I jokingly said, “If the software business doesn’t work out you guys got a pretty good football team here.” Without missing a beat Brent said, “Nah, we already did that. We were the Dartmouth football team front defensive three.” Oh.

But that wasn’t the only surprise of the day. While I thought I was consulting, Onyx was actually trying to recruit me as their VP of Marketing. At the end of the day I came away thinking it was smart and aggressive team, thought the world of Brent Frei as a CEO and knew Onyx was going to succeed – despite their Microsoft monoculture. With an unexpected job offer in-hand I spent the plane flight home concluding that our family had already planted roots too deep to move to Seattle.

But in that one day I had learned a lot about sales automation that would shape my thinking when we founded Epiphany.

I Know A Great Customer

A year later my co-founders and I had formed Epiphany. As other startups were quickly automating all the department of large corporations (SAP-manufacturing, Oracle-finance, Siebel and Onyx-Sales) our first thought was that our company was going to automate enterprise-marketing departments. And along with that first customer hypothesis I had the brilliant hypothesis that my channel partner should be Onyx. I thought, “If they already selling to the sales department Epiphany’s products could easily be cross-sold to the marketing department.”

So I called on my friends at Onyx and got on a plane to Seattle. They were growing quickly and doing all they could to keep up with their own sales but they were kind enough to hear me out. I outlined how our two products could be technically integrated together, how they could make much more money selling both and why it was a great deal for both companies. They had lots of objections but I turned on the sales charm and by the end of the meeting had “convinced them” to let us integrate both our systems to see what the result was. I made the deal painless by telling them that we would do the work for free because when they saw the result they’d love it and agree to resell our product. I left with enough code so our engineers could get started immediately.

Bad idea. But I didn’t realize that at the time.

It’s Only a Month of Work

Back at Epiphany I convinced my co-founders that integrating the two systems was worth the effort and they dove in. Onyx gave us an engineering contact and he helped our team make sense of their system. One of the Onyx product managers got engaged and became an enthusiastic earlyvanglist. The integration effort probably used up a calendar month of our engineering time and an few hours of theirs. But when it was done the integrated system was awesome. No one anything like this. We shipped a complete server up to Onyx (this is long before the cloud) and they assured us they would start evaluating it.

A week goes by and there’s radio silence – nothing is heard from them. Another week, still no news. In fact, no one is returning our calls at all. Finally I decide to get on a plane and see what has happened to our “deal.”

Instead of being welcomed by the whole Onyx exec staff, this time a clearly uncomfortable product manager met me. “Well how do like our integrated system?” I asked. “And by the way where is it? Do you have it your demo room showing it to potential customers?” I had a bad feeling when he wouldn’t make eye contact. Without saying a word he walked me over to a closet in the hallway. He opened the door and pointed to our server sitting forlornly in the corner, unplugged. I was speechless. “I’m really sorry” he barely whispered. “I tried to convince everyone.” Now a decade and a half later the sight of server literally sitting next to the brooms, mops and buckets is still seared into my brain.

I had poured everything into making this work and my dreams had been relegated to the janitors closet. My heart was broken. I managed to sputter out, “Why aren’t you working on integrating our systems?

Just then their VP of Sales came by and gently pulled me into a conference room letting a pretty stressed product manager exhale. “Steve, you did a great sales job on us. We really were true believers when you were in our conference room. But when you left we concluded over the last month that this is your business not ours. We’re just running as hard and fast as we can to make ours succeed.”

Unrequited Love

I realized that mistake wasn’t my vision. Nor was it my passion for the idea. Or convincing Onyx that it was a great idea. And besides not being able to tell me straight out, Onyx did nothing wrong. My mistake was pretty simple – when I left their board room a month earlier I was the only one who had an active commitment and obligation to make the deal successful. It may seem like a simple tactical mistake, but it in fact it was fatal. They put none of their resources in the project – no real engineering commitment, no dollars, no orders, no joint customer calls.

It had been a one-way relationship the day I had left their building.

It would be 15 years before I would make this mistake again.

Lessons Learned

When you don’t charge for something people don’t value it

When your “partners” aren’t putting up proportional value it’s not a relationship

Cheerleading earlyvangelists are critical but ultimately you need to be in constant communication with people with authority (to sign checks, to do a deal, to commit resources, etc.)

Your reality distortion field may hinder your ability to realize that you’re the only one marching in the parade

If there’s only one passionate party in a deal it’s unrequited love

Filed under: Customer Development, E.piphany, Marketing

July 19, 2012

Tenacious

Adjective:

Not readily letting go of, giving up, or separated from an object that one holds, a position, or a principle: “a tenacious grip”.

Not easily dispelled or discouraged; persisting in existence or in a course of action.

When I was a entrepreneur I’d pursue a goal relentlessly. Everything in between me and my goal was simply an obstacle that needed to be removed.

This week I had another reminder of what it was like.

Plenty of Time

I was speaking at the National Governors Conference in Williamsburg Virginia and my talk ended Sunday at noon. I knew I had to be in Chicago at 9:30Am Monday for a Congressional hearing (I was the lead witness) so I made sure I was on the next to last plane out of Richmond (just in case the last one got cancelled.)

My wife and I got to the airport for our 4:45pm plane and found it was delayed to 6pm. Ok, no problem. Oops now it’s delayed until 7:30pm. Hmm, the last plane out looks like it’s leaving on-time at 8pm – can I get on that? No, sold out. So we sit around and watch our plane get delayed to 8pm, then 9pm then 10pm, then cancelled. Oh, oh this is looking a bit tight, but there’s a 6am from Richmond to Chicago. No problem. If we can get on that I can still make the hearing. The nice smiling United agent says “oh that’s sold out as well. Now I’m getting a bit concerned, “Well how about the American Airlines 6am?” “Sold out” she replied. The next flight is at 8am.” Ok put me on that one. ”Oh that’s sold out as well.”

We Have a Problem

I need to be in downtown Chicago by 9:30am. Period.

So I ask, “where’s the nearest airport that has a 6am flight to Chicago?” Oh, that’s Dulles airport in Washington.”Ok, how far is that?” 120 miles.

We head back to the car rental booth, rent our second car of the day and head to Washington in pouring rain and drive in bumper to bumper traffic, crawling to our next airport. Three hours later we check into the airport hotel at 1:30am assured that all we needed to do is get 3 hours sleep and United would whisk us on the way to Chicago.

Tenacious

Waking up at 4:15am I glance at my email and couldn’t believe it – United canceled our 6am from Dulles. The next flight they had would get us into Chicago at 10am – too late to testify in front of Congress. It looked like there was simply no way to get where we needed to go.

My first instinct was to give up. Screw it. I tried hard, failed due to circumstances beyond my control. Why don’t we just go back to bed and get a good nights sleep.

That thought lasted all of 30 seconds.

We quickly realized that Washington has two airports – the other one, National was 30 miles away. I looked up the flight schedule and realized that there was a 6am and 7am leaving from National. I booked the 7am online not believing we could make the earlier 6am flight.

The only problem is that there weren’t any taxi’s to be found at 4:30 in the morning – in front of the hotel or on Uber. So I hiked over to the main road and flagged one down and had him drive me back to the hotel, pick up my wife and luggage and continued our adventure.

We got to Washington National Airport at 5am and walked directly into the longest security line I’ve seen in 10 years. Well, at least we can make the 7am plane (the one we’re ticketed on) and barely make the congressional hearing.

Getting through security the first gate we pass is the 6am for Chicago and they’re in the process of closing the door. ”Any chance you have any seats left?” Oh, we have two seats in the back of the plane but we don’t have time to re-ticket you.

Trying to remember my reality distortion field skills from my entrepreneurial days I convinced her to let us on.

We made it to Chicago. I actually got to sleep in our hotel for 45 minutes before the Congressional Field hearing.

Then I got to share this:

Lessons Learned

Your personal life and career will be full of things that block your way or hinder progress

Keep your eyes on the prize, not the obstacles

Remove obstacles one at a time

There’s almost always a path to your goal

Never, never never give up

Filed under: Family/Career/Culture

June 26, 2012

On Vacation

In Prague for the last three days and heading to Berlin tonight. Had an impromptu meet up with the local Prague entreprenuerial community. Smart group. It just reminds me that the worldwide democratization of entreprenuership is real. However, as in many other countries the lack of local “risk capital”, startup business expertise, infrasturcture and startup culture, forces most of the Czech startups to leave and head to Silicon Valley.

Warning very large (>20mb) files below. Click only for a panorama.

Charles Bridge over the Vltava River.

I saw two of the most beautiful libraries ever in the Starhov Monastery in Prague.

Theological Hall Strahov Monastery.

Now the question is – can I add one of them onto the ranch?

Philosophical Hall Strahov Monastery.

Filed under: Customer Development

June 11, 2012

Making a Dent in the Universe – Results from the NSF I-Corps

Our goal teaching for the National Science Foundation was to make a dent in the universe.

Could we actually teach tenured faculty how to turn an idea into a company? And if we did, could it change their lives?

We can now answer these questions.

Hell yes.

———–

The Lean LaunchPad class for the National Science Foundation (NSF)

Over the last 6 months, we’ve been teaching a version of the Lean LaunchPad class for the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps. We’ve taught two cohorts: 21 teams ending in December 2011, and 24 teams ending in May 2012. In July 2012 we’ll teach 50 more teams, and another 50 in October. Each 3-person team consists of a Principal Investigator, an Entrepreneurial Lead and a Mentor.

The Principal Investigator (average age of ~45) is a tenured faculty running their own research lab who has had an active NSF grant within the last 5 years. The Principal Investigator forms the team by selecting one of his graduate students to be the Entrepreneurial Lead.

The Entrepreneurial Lead is a graduate student or post doc (average age ~ 28) who works within the Principal Investigator’s lab. If a commercial venture comes out of the I-Corps, it’s more than likely that the Entrepreneurial Lead will take an active role in the new company. (Typically Principal Investigators stay in their academic role and continue as an advisor to the new venture.)

Mentors (average age ~50) are an experienced entrepreneur located near the academic institution and has experience in transiting technology out of academic labs. Mentors are recommended by the Principal Investigator (who has worked with them in the past) or they may be a member of the NSF I-Corps Mentor network. Some mentors may become an active participant in a startup that comes out of the class.

The NSF I-Corps: Class Goals

The NSF I-Corps Lean LaunchPad class has different goals then the same class taught in a university or incubator. In a university, the Lean LaunchPad class teaches a methodology the students can use for the rest of their careers. In an incubator, the Lean LaunchPad develops angel or venture-funded startups.

Unlike an incubator or university class, the goal of the NSF I-Corps is to teach researchers how to move their technology from an academic lab into the commercial world. A successful outcome is a startup or a patent or technology license to a U.S. company.

(While many government agencies use Technology Readiness Levels to measure a projects technical maturity, there are no standards around Business Maturity Levels. The output of the NSF I-Corps class provides a proxy.)

The NSF I-Corps doesn’t pick winners or losers. It doesn’t replace private capital with government funds. Its goal is to get research the country has already paid for educated to the point where they can attract private capital. (It’s why we teach the class with experienced Venture Capitalists.)

Teaching Objectives

Few of the Principal Investigators or Entrepreneurial Leads had startup experience, and few of the mentors were familiar with Business Model design or Customer Development.

Therefore, the teaching objectives of the I-Corps class are:

1) Help each team understand that a successful company was more than just their technology/invention by introducing all the parts of a business model (customers, channel, get/keep/grow, revenue models, partners, resources, activities and costs.)

2) Get the teams out of the building to test their hypotheses with prospective customers. The teams in the first cohort averaged 80 customer meetings per team; the second cohort spoke to an average of 100.

3) Motivate the teams to pursue commercialization of their idea. The best indicators of their future success were whether they a) found a scalable business model, b) had an interest in starting a company, and c) would pursue additional funding.

Methodology

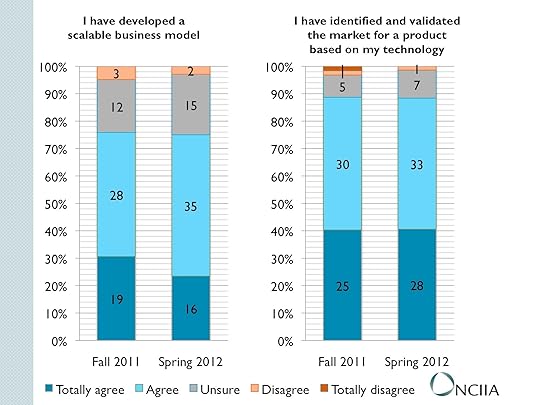

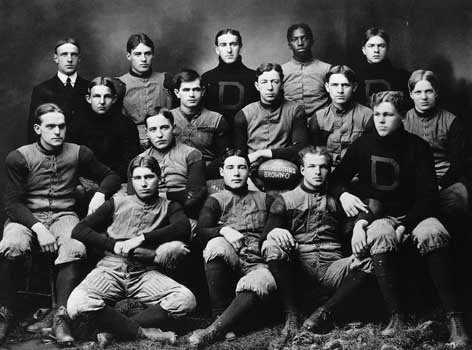

The National Science Foundation worked with NCIIA to establish a baseline of what the students knew before the class and followed it up with a survey after the class.

While my experience in teaching students at Stanford, Berkeley and Columbia told me that this class was an effective way to teach all the parts that make up a startup, would the same approach work with academic researchers?

Here’s what they found.

Results

Teams came into the class knowing little about what parts made up a company business model (customers, channel, get/keep/grow, revenue models, partners, resources, activities and costs.) They left with very deep knowledge.

I-Corps teams spent the class refining their business model and minimum viable product. By the end of the class:

Over 95% believed that they found a scalable business model.

98% felt that they had found “product/market fit”.

The class increased everyones interest in starting a company. 92% said they were going to go out and raise money – either from the NSF or with private capital. (This was a bit astonishing. Given that most of them didn’t know what a startup was coming in. These are new jobs being created.)

One of the unexpected consequences of the class was its effect on the Principal Investigators, (almost all tenured professors.) A surprising number said the ideas for the class will impact their research, and 98% of all of the attendees said it was going to be used in their careers.

Another unexpected result was the impact the class had on the professors own thinking about how they would teach their science and engineering students. We got numerous comments about “I’m going to get my department to teach this.”

What’s Next

The NSF and NCIIA understand that the analysis doesn’t end by just studying the results of each cohort. We need to measure what happens to the teams and each of the team members (Principal Investigator, Entrepreneurial Lead and Mentor) over time. It’s only after a longitudinal study that will take years, can we see how deep of a dent we made in the universe.

But I think we’ve made a start.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the team at NCIIA that provided the survey and analytical data (Angela Shartrand) and the logistical support (Anne Hendrixson) to run these NSF classes.

The National Science Foundation (Errol Arkilic, Babu DasGupta) took a chance at changing the status quo.

Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle who’ve realized cracking the code on how to teach starting companies means a brighter day for the future of all jobs in the United States – not just tech startups.

And thanks to the venture capitalists and entrepreneurs who volunteer their time for their country; Jon Feiber from MDV, John Burke from True Ventures, Jim Hornthal from CMEA, Jerry Engel from Monitor Ventures (and the U.C. Berkeley Haas Business School,) Oren Jacob from ToyTalk and Lisa Forssell of Pixar.

And to our new teaching teams at University of Michigan and Georgia Tech – It’s your turn.

Lessons Learned

The Lean LaunchPad class (Business Model design+Customer Development+ extreme hands-on) works

They leave knowing:

how to search for a business model (customers, channel, get/keep/grow, revenue models, partners, resources, activities and costs,)

how to find product/market fit, and a scalable business model

It has the potential to change careers, lives and our country

Filed under: Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

June 4, 2012

Entrepreneurship for the 99%

This is a guest post from Jerry Engel, the Faculty Director of the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps (and the Founding Faculty Director of the Lester Center for Entrepreneurship at UC Berkeley.)

———–

The 99%

As the morning fog burns off the California coast, I am working with Steve Blank, preparing for the Lean LaunchPad Faculty Development Program we are running this August at U.C. Berkeley. This is a 3-day program for entrepreneurship faculty from around the world how to teach entrepreneurship via the Lean LaunchPad approach (business model canvas + customer development) and bring their entrepreneurship curriculums into the 21st century. Over the past couple of years this Lean LaunchPad model has proven immensely effective at Berkeley, Stanford, Columbia and, of course, the National Science Foundations Innovation-Corps program. The data from the classes seem to indicate that we’ve found have a method how to make scalable startups fail less.

While we’re excited by the results, we’ve realized that we’ve been solving the problem for the 1% of new ventures that are technology startups. The reality is that the United States is still a nation of small businesses. 99.7% of the ~6 million companies in the U.S. have less than 500 people and they employ 50% of the 121 million workers getting a paycheck. They accounted for 65 percent (or 9.8 million) of the 15 million net new jobs created between 1993 and 2009. And while they increasingly use technology as a platform and/or a way of reaching and managing customers, most are in non-tech businesses (construction, retail, health care, lodging, food services, etc.)

While we were figuring out how to be incredibly more efficient in building new technology startups, three out out of 10 new small businesses will fail in 2 years, half fail within 5 years. The tools and techniques available to small businesses on Main Street are the same ones that were being used for the last 75 years.

Therefore, our remaining challenges are how to make them fail less – and how can we make the Lean LaunchPad approach relevant to the rest of the 99% of startups.

Serendipity

A serendipitous answer came to us around noon. His name is Alex Lawrence. Alex, vice provost for Innovation & Economic Development at Weber State University in Utah and completing his first year of teaching entrepreneurship. Alex is a successful serial entrepreneur –with the same drive and energy of many we have known here in Silicon Valley, but different. His nine startups have ranged from franchised fruit juice shops to Lendio a financial services company for small businesses. Alex had been recruited back by his Alma Matter to create an entrepreneurship program. In fact he had just been charged with creating an entrepreneurship minor – five or six courses for students of any major at the University that would help prepare them for the challenge of starting their own businesses.

Alex’s first insight was that the traditional “how to write a business plan” was as obsolete for Main Street as it is for Silicon Valley. So he had adopted Steve’s Lean LaunchPad class and was using The Startup Owner’s Manual as his core text. He had contacted us seeking advice on developing his curriculum, and it just seemed natural to invite him out to the ranch for a deeper dive.

As we dug into learning about Alex’s teaching experience we naturally asked him about the ventures his own students were creating. It was clear Alex was a bit apologetic; photo studios, online retail subscriptions to commodity household and personal hygiene products, etc. Alex explained that in his community building a successful venture that generated nice cash flows – not IPO’s – were the big win. To his students these were not “small businesses”, but ‘their businesses’, their livelihoods and their opportunities to create wealth and independence for themselves and their families.

Mismatch for Main Street

As we walked out to the pond, Alex explained that while he found the teachings of the Lean LaunchPad directly applicable and effective, there was a mismatch for his students in the size of the end goal (a great living versus a billion dollar IPO) and the details of the implementation of the business model (franchise and multilevel marketing versus direct sales, profit sharing versus equity for all, family and SBA loans versus venture capital, etc.)

Sitting by the pond we had a second epiphany: we could easily adjust the Lean LaunchPad class to bring 21st century entrepreneurship techniques to ‘Main Street’. To do this we needed to do is change the end goals and implementation details to match the aspirations and realities that these new small businesses face.

We called this Mainstream Entrepreneurship.

Mainstream Entrepreneurship

Mainstream Entrepreneurship recognizes that with the Lean LaunchPad class we now have a methodology of making small businesses fail less. That accelerating business model search and discovery and using guided customer engagement as a learning process, we could help founders of mainstream businesses just like those starting technology ventures.

For the rest of the afternoon, Steve and I brainstormed with Alex about how he could take his 20 years of entrepreneurial small business experience and use the Business Model Canvas and Customer Development to create a university entrepreneurship curriculum and vocabulary for the mainstream of American Business.

We think we got it figured out.

Alex Lawrence will be one of the presenters at the Lean LaunchPad Educators Program August 22-24th in Berkeley.

Lessons Learned

Small businesses make up 99.7% of U.S. companies

“How to write a business plan” is as obsolete for Main Street as it is for Silicon Valley

Using the Lean LaunchPad (the business model canvas and Customer Development) are the right tools

Small businesses have different end goals and implementation details

We can adapt/modify the Lean LaunchPad approach to embrace these goals/details

Filed under: Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

May 21, 2012

Why Facebook is Killing Silicon Valley

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win…

John F. Kennedy, September 1962

Innovation

I teach entrepreneurship for ~50 student teams a year from engineering schools at Stanford, Berkeley, and Columbia. For the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps this year I’ll also teach ~150 teams led by professors who want to commercialize their inventions. Our extended teaching team includes venture capitalists with decades of experience.

The irony is that as good as some of these nascent startups are in material science, sensors, robotics, medical devices, life sciences, etc., more and more frequently VCs whose firms would have looked at these deals or invested in these sectors, are now only interested in whether it runs on a smart phone or tablet.

And who can blame them.

Facebook and Social Media

Facebook has adroitly capitalized on market forces on a scale never seen in the history of commerce. For the first time, startups can today think about a Total Available Market in the billions of users (smart phones, tablets, PC’s, etc.) and aim for hundreds of millions of customers. Second, social needs previously done face-to-face, (friends, entertainment, communication, dating, gambling, etc.) are now moving to a computing device. And those customers may be using their devices/apps continuously. This intersection of a customer base of billions of people with applications that are used/needed 24/7 never existed before.The potential revenue and profits from these users (or advertisers who want to reach them) and the speed of scale of the winning companies can be breathtaking.

The Facebook IPO has reinforced the new calculus for investors. In the past, if you were a great VC, you could make $100 million on an investment in 5-7 years. Today, social media startups can return 100’s of millions or even billions in less than 3 years. Software is truly eating the world.

If investors have a choice of investing in a blockbuster cancer drug that will pay them nothing for fifteen years or a social media application that can go big in a few years, which do you think they’re going to pick? If you’re a VC firm, you’re phasing out your life science division.

As investors funding clean tech watch the Chinese dump cheap solar cells in the U.S. and put U.S. startups out of business, do you think they’re going to continue to fund solar? And as Clean Tech VC’s have painfully learned, trying to scale Clean Tech past demonstration plants to industrial scale takes capital and time past the resources of venture capital. A new car company? It takes at least a decade and needs at least a billion dollars. Compared to IOS/Android apps, all that other stuff is hard and the returns take forever.

Instead, the investor money is moving to social media. Because of the size of the market and the nature of the applications, the returns are quick – and huge.

New VC’s, focused on both the early and late stage of social media have transformed the VC landscape. (I’m an investor in many of these venture firms.) But what’s great for making tons of money may not be the same as what’s great for innovation or for our country.

Entrepreneurial clusters like Silicon Valley (or NY, Boston, Austin, Beijing, etc.) are not just smart people and smart universities working on interesting things. If that were true we’d all still be in our parents garage or lab. Centers of innovation require investors funding smart people working on interesting things - and they invest in those they believe will make their funds the most money. And for Silicon Valley the investor flight to social media marks the beginning of the end of the era of venture capital-backed big ideas in science and technology.

Don’t Worry We Always Bounce Back

The common wisdom is that Silicon Valley has always gone through waves of innovation and each time it bounces back by reinventing itself.

[Each of these waves of having a clean beginning and end is a simplification. But it makes the point that each wave was a new investment thesis with a new class of investors as well as startups.]

[Each of these waves of having a clean beginning and end is a simplification. But it makes the point that each wave was a new investment thesis with a new class of investors as well as startups.]

The reality is that it took venture capital almost a decade to recover from the dot-com bubble. And when it did Super Angels and new late stage investors whose focus was social media had remade the landscape, and the investing thesis of the winners had changed. This time the pot of gold of social media may permanently change that story.

What Next

It’s sobering to realize that the disruptive startups in the last few years not in social media - Tesla Motors, SpaceX, Google driverless cars, Google Glasses - were the efforts of two individuals, Elon Musk, and Sebastian Thrun (with the backing of Google.) (The smartphone and tablet computer, the other two revolutionary products were created by one visionary in one extraordinary company.)

We can hope that as the Social Media wave runs its course a new wave of innovation will follow. We can hope that some VC’s remain contrarian investors and avoid the herd. And that some of the newly monied social media entrepreneurs invest in their dreams. But if not, the long-term consequences for our national interests will be less than optimum.

For decades the unwritten manifesto for Silicon Valley VC’s has been; We choose to invest in ideas, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.

Here’s hoping that one day they will do it again.

.

If you can’t see the video above click here.

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

May 14, 2012

9 Deadliest Start-up Sins

Inc. magazine is publishing a 12-part series of excerpts from The Startup Owner’s Manual, the new step-by-step “how to” guide for startups. The excerpts, which appeared first at Inc.com, highlight the Customer Development process, best practices, tips and instructions contained in our book. Feedback from my readers suggested you’d appreciate seeing the series posted here, as well.

———–

Whether your venture is a new pizza parlor or the hottest new software product, beware: These nine flawed assumptions are toxic.

1. Assuming you know what the customer wants

First and deadliest of all is a founder’s unwavering belief that he or she understands who the customers will be, what they need, and how to sell it to them. Any dispassionate observer would recognize that on Day One, a start-up has no customers, and unless the founder is a true domain expert, he or she can only guess about the customer, problem, and business model. On Day One, a start-up is a faith-based initiative built on guesses.

To succeed, founders need to turn these guesses into facts as soon as possible by getting out of the building, asking customers if the hypotheses are correct, and quickly changing those that are wrong.

2. The “I know what features to build” flaw

The second flawed assumption is implicitly driven by the first. Founders, presuming they know their customers, assume they know all the features customers need.

These founders specify, design, and build a fully featured product using classic product development methods without ever leaving their building. Yet without direct and continuous customer contact, it’s unknown whether the features will hold any appeal to customers.

3. Focusing on the launch date

Traditionally, engineering, sales, and marketing have all focused on the immovable launch date. Marketing tries to pick an “event” (trade show, conference, blog, etc.) where they can “launch” the product. Executives look at that date and the calendar, working backward to ignite fireworks on the day the product is launched. Neither management nor investors tolerate “wrong turns” that result in delays.

The product launch and first customer ship dates are merely the dates when a product development team thinks the product’s first release is “finished.” It doesn’t mean the company understands its customers or how to market or sell to them, yet in almost every start-up, ready or not, departmental clocks are set irrevocably to “first customer ship.” Even worse, a start-up’s investors are managing their financial expectations by this date as well.

4. Emphasizing execution instead of testing, learning, and iteration

Established companies execute business models where customers, problems, and necessary product features are all knowns; start-ups, on the other hand, need to operate in a “search” mode as they test and prove every one of their initial hypotheses.

They learn from the results of each test, refine the hypothesis, and test again—all in search of a repeatable, scalable, and profitable business model. In practice, start-ups begin with a set of initial guesses, most of which will end up being wrong. Therefore, focusing on execution and delivering a product or service based on those initial, untested hypotheses is a going-out-of-business strategy.

5. Writing a business plan that doesn’t allow for trial and error

Traditional business plans and product development models have one great advantage: They provide boards and founders an unambiguous path with clearly defined milestones the board presumes will be achieved. Financial progress is tracked using metrics like income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow. The problem is, none of these metrics are very useful because they don’t track progress against your start-up’s only goal: to find a repeatable and scalable business model.

6. Confusing traditional job titles with a startup’s needs

Most startups simply borrow job titles from established companies. But remember, these are jobs in an organization that’s executing a known business model. The term “Sales” at an existing company refers to a team that repeatedly sells a known product to a well-understood group of customers with standard presentations, prices, terms, and conditions. Start-ups by definition have few, if any, of these. In fact, they’re out searching for them!

The demands of customer discovery require people who are comfortable with change, chaos, and learning from failure and are at ease working in risky, unstable situations without a roadmap.

7. Executing on a sales and marketing plan

Hiring VPs and execs with the right titles but the wrong skills leads to further trouble as high-powered sales and marketing people arrive on the payroll to execute the “plan.” Executives and board members accustomed to measurable signs of progress will focus on these execution activities because this is what they know how to do (and what they believe they were hired to do). Of course, in established companies with known customers and markets, this focus makes sense.

And even in some start-ups in “existing markets,” where customers and markets are known, it might work. But in a majority of startups, measuring progress against a product launch or revenue plan is simply false progress, since it transpires in a vacuum absent real customer feedback and rife with assumptions that might be wrong.

8. Prematurely scaling your company based on a presumption of success

The business plan, its revenue forecast, and the product introduction model assume that every step a start-up takes proceeds flawlessly and smoothly to the next.

The model leaves little room for error, learning, iteration, or customer feedback.

Even the most experienced executives are pressured to hire and staff per the plan regardless of progress. This leads to the next startup disaster: premature scaling.

9. Management by crisis, which leads to a death spiral

The consequences of most start-up mistakes begin to show by the time of first customer ship, when sales aren’t happening according to “the plan.” Shortly thereafter, the sales VP is probably terminated as part of the “solution.”

A new sales VP is hired and quickly concludes that the company just didn’t understand its customers or how to sell them. Since the new sales VP was hired to “fix” sales, the marketing department must now respond to a sales manager who believes that whatever was created earlier in the company was wrong. (After all, it got the old VP fired, right?)

Here’s the real problem: No business plan survives first contact with customers. The assumptions in a business plan are simply a series of untested hypotheses. When real results come in, the smart startups pivot or change their business model based on the results. It’s not a crisis, it’s part of the road to success.

Filed under: Customer Development

May 1, 2012

Why Innovation Dies

Faced with disruptive innovation, you can be sure any possibility for innovation dies when a company forms a committee for an “overarching strategy.”

—–

I was reminded how innovation dies when the email below arrived in my inbox. It was well written, thoughtful and had a clearly articulated sense of purpose. You may have seen one like it in your school or company.

Skim it and take a guess why I first thought it was a parody. It’s a classic mistake large organizations make in dealing with disruption.

The Strategy Committee

Faculty and Staff:

We believe online education will become increasingly important at all levels of the educational experience. If our school is to retain its current standards in terms of access and excellence we think it is of paramount importance that we develop an overarching campus strategy that enables and supports online innovation.

We believe our Departments play an essential leadership role in the design and implementation of online offerings. However, we also want to provide guidance and support and ensure that campus goals are met, specifically ensuring that our online education efforts align with our mission, values and operational requirements.

To this end, we are convening a Strategy Committee that is charged with overseeing our efforts and accelerating implementation. The responsibilities of the group will be to provide overall direction to campus, make decisions concerning strategic priorities and allocate additional resources to help realize these priorities. Because we anticipate that most of the innovation in this area will occur at the school/unit level we underscore that the purpose of the Strategy Committee is to provide campus-level guidance and coordination, and to enable innovation. The Strategy Committee will also be responsible for reaching out to and receiving input from the Presidents Staff and the Faculty Senate.

The Strategy Committee will be comprised of Mark Time, Nick Danger, Ralph Spoilsport, Ray Hamberger, Audrey Farber, Rocky Rococo, George Papoon, Fred Flamm, Susan Farber, and Clark Cable.

A Policy Team, which is charged with coordinating with the schools/unit to develop detailed implementation plans for specific projects, will report to the Strategy Committee. The role of the Policy Team will be to develop a detailed strategic framework for the campus, oversee the development of shared resources, disseminate best practices, create an administrative infrastructure that provides consistent financial and legal expertise, and consult with relevant campus groups: and the the Budget Office. The Policy Team will be led by two senior campus leaders, one from the academic side and one from the administration side.

We are extremely pleased that Dean TIrebiter has accepted the administrative lead role of the Policy Team. Dean Tirebiter brings to this position a deep knowledge of the online environment. He will be helping to identify a member of our Faculty to serve as the academic lead of the Policy Team.

The Strategy Committee will be meeting for a half-day retreat at Morse Science Hall in the coming weeks to begin work. We will be sending out an update to faculty and following this retreat, so stay tuned for further updates.

Sincerely,

President Peter Bergman

We Can Figure it Out in A Meeting

The memo sounds thoughtful and helpful. It’s an attempt to get all the “right” stakeholders in the room and think through the problem.

One useful purpose a university committee could have had was figuring out what the goal of going online was. It could have said “the world expects us to lead so lets get together and figure out how we deal with online education.” Our goal(s) could be:

Looking good

Doing good for all [or at least citizens of California]

Doing well by our enrolled students

Fixing our business model to fix our budget crisis

Having a good football team – or at least filling the stadium

Attracting donations

Attracting faculty

Oh and yes – building an efficient, high quality education machine

But the minute the memo started talking about a Policy Team developing detailed implementation plans, it was all over.

The problem is that the path to implementing online education is not known. In fact, it’s not a solvable problem by committee, regardless of how many smart people in the room. It is a “NP complete” problem – it is so complex that figuring out the one possible path to a correct solution is computationally incalculable. (See the diagram below.)

If you can’t see the diagram above click here.

Innovation Dies in Conference Rooms

The “lets put together a committee” strategy fails for four reasons:

Online education is not an existing market. There just isn’t enough data to pick what is the correct “overarching strategy”.

Making a single bet on a single strategy, plan or company in a new market is a sure way to fail. After 50-years even the smartest VC firms haven’t figured out how to pick one company as the winner. That’s why they invest in a portfolio.

Committees protect the status quo. Everyone who has a reason to say “No” is represented.

Dealing with disruption is not solved by committee. New market problems call for visionary founders, not consensus committee members.

My bet is that there will be more people involved in this schools Strategy Committee then in the startups that find the solution.

In a perfect world, the right solution would be a one page memo encouraging maximum experimentation with the bare minimum of rules (protecting the schools brand and the applicable laws.)

Lessons Learned

Innovation in New Markets do not come from “overarching strategies”

It comes out of opportunity, chaos and rapid experimentation

Solutions are found by betting on a portfolio of low-cost experiments

With a minimum number of constraints

The road for innovation does not go through committee

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development, Teaching

April 28, 2012

Five Days to Change the World – The Columbia Lean LaunchPad Class

We’ve taught our Lean LaunchPad entrepreneurship class at Stanford, Berkeley, Columbia and the National Science Foundation in 8 week, 10 week and 12 week versions. We decided to find out what was the Minimum Viable Product for our Lean LaunchPad class.

Could students get value out of a 5-day version of the class?

The Setup

At the invitation of Murray Low at the Entrepreneurship Center in the Columbia Business School, we went to New York to find out. We were going to teach the Lean LaunchPad class in 5-days. I was joined by my Startup Owners Manual co-author Bob Dorf, Alexander Osterwalder (author of Business Model Generation) and Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures.

As we’ve done in previous classes, the students form teams and come up with an idea before the class.

Potential students watched an on-line video of Osterwalder explaining the Business Model Canvas and then applied for admission to the class with a fully completed business model canvas. Here are two examples:

If you can’t see the presentation above, click here.

If you can’t see the presentation above, click here.

The Class

We had 69 students in 13 teams. Instead of going around the room introducing themselves, each group hit the ground running by presenting their canvas.

The class organization was pretty simple:

textbooks were The Startup Owners Manual and Business Model Generation

team presentations 9-12:30 (with continual instructor critiques)

working lunch 12:30-1:30 (with office hours)

lecture 1:30-3:00

get out of the building 3:00-on

repeat for 5-days

Resources

The 5-day syllabus is here.

All 13 teams Day 1 presentations are here.

Day 2 presentations here.

Day 3 presentations here.

Day 4 presentations here.

Day 5 presentations here.

The Outcome

After 5 days the teams collectively had ~1,200 face-to-face customer interviews, with another 1,000+ potential customers surveyed on-line.

Take a look at the same two teams presentations (compare it to their slides above):

If you can’t see the presentation above, click here.

If you can’t see the presentation above, click here.

Lessons Learned:

A five day Lean Launchpad Class is definitely worth doing.

The Business Model Canvas + Customer Development works even in this short amount of time

However we were in NYC where customer density was high.

As we’ve already found, this class needs to be taught as a joint engineering/mba class

Next time we teach we will complete the transition to a flipped classroom:

Have no lectures during class. We’ll offer video lectures, and use the time for class labs built around detailed analysis of 2 or 3 canvas pivots

Make teams use Salesforce, or some similar package, to track all contacts/customer calls

Filed under: Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers