Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 120

June 11, 2015

NATO Bet, by Bryan Caplan

"At

least half of Germans, French and Italians say their country should not

use military force to defend a NATO ally if attacked by Russia," the

Pew Research Center said it found in its survey, which is based on

interviews in 10 nations.

There is more here, and so every great moderation must come to an end...

This is also of note:

According to the study, residents of most NATO countries still believe that the United States would come to their defense.

Meanwhile:

Eighty-eight percent of Russians said they had confidence in Mr. Putin to do the right thing on international affairs...

Solve for the equilibrium, as they like to say. It is much easier to

stabilize a conservative power (e.g., the USSR) than a revisionist

power (Putin's Russia).

In contrast, I think (a) a Russian attack on a NATO member is highly unlikely, and (b) would provoke a massive military response by NATO. Even a low-level, unofficial war in Ukraine has cost Russia dearly, and it looks to me like it will slowly become another "frozen conflict" in the Russian sphere of influence. Attacking a NATO member would not be suicide for Putin, but still much too risky for his taste.

As always, I am willing to bet on my forecast. I give even odds that Russia attacks zero NATO members for the next 25 years. I also give 5:1 odds that Russia attacks zero NATO members in the next 5 years. If anyone wants to bet, we can hammer out the exact definition of "attacks." I'm inclined to say that if the New York Times, Wall St. Journal, and Washington Post all have front-page stories saying that 1000 or more Russian troops have entered a specific NATO member, I lose. But I'm open to other definitions.

(13 COMMENTS)June 9, 2015

Identificationists Beware, by Bryan Caplan

Sometimes people ask me where I stand on economic policy. Am I a

free-marketer or an interventionist? I tell them that I'm an

identificationist.

In statistics, "identification" just means separating two groups in

order to tell if a treatment works. You give Group A the pill and you

give Group B a placebo, and you see if Group A does better than Group B.

In laboratory experiments this is usually possible to do. In the real

world, it's a lot harder -- you have to wait for a policy to bring about

a difference between two areas that are roughly comparable.

This is why I'm so happy about the $15 minimum wage that is being phased in in cities such as Los Angeles, Seattle, and San Francisco. We're about to find out if minimum wage laws really have big negative effects on the economy.

But how convincing will these experiments really be? If I were sympathetic to the minimum wage, I would say, "The worst the experiments will show is that high minimum wages hurt employment in individual cities. That wouldn't be too surprising, because it's easy for firms and workers to move in and out of cities. The experiments will shed little light on state-level minimum wages, and essentially no light on federal minimum wages. Identificationists like Noah are looking for their keys under the streetlight because it's brighter there."

Are these bad arguments? They are if you only embrace them after you incorrectly predict no change in employment. But minimum wage supporters can and should precommit to them today. Contrary to Noah, these city-level experiments barely speak to the debate that's raged in economics for decades.

The good news, though, is that there's a lot more relevant evidence on the disemployment effects of the minimum wage than Noah admits. It just hasn't been suitable framed.

(13 COMMENTS)June 8, 2015

Two Types of Fear, by Bryan Caplan

Type 1: Saying that a disaster will happen under certain conditions. Example: "If population continues to grow, hundreds of millions will starve by the year 1980."

Type 2: Saying that a disaster may happen under certain conditions. Example: "If we don't destroy ISIS, a nuclear bomb could go off in New York City sometime in the next 20 years."

Type 1 fear-mongering is almost always literally false, and therefore blatantly intellectually dishonest. Why? Because (a) disasters are extremely rare, and (b) predicting the rare disasters that do occur is extremely difficult. Think I'm being unfair? Then predict a well-defined, major disaster and bet me you're right at 5:1 odds. [crickets]

Type 2 fear-mongering, in contrast, is almost never literally false, and therefore almost never blatantly intellectually dishonest. Since virtually any scary scenario could happen, Type 2 speculations are not lies. On a deeper level, however, most Type 2 fear-mongering remains subtly intellectually dishonest. Why? Because the (a) whole point of Type 2 is to scare people into action, but (b) action without probabilities is folly. You can paint lurid scenarios about anything, but you can't "do something" about everything. Furthermore, "doing something" is often worse than doing nothing.

My general view is that the differences between Democrats/liberals and Republicans/conservatives are greatly overrated. Nevertheless, my strong impression is that the left is more inclined to Type 1 fear-mongering (think: the environment), while the right is more inclined to Type 2 fear-mongering (think: terrorism). Know of any relevant data?

(11 COMMENTS)

June 7, 2015

The Sum of All Fears, by Bryan Caplan

I didn't think there was anything more to say about infamous doomsayer Paul Ehrlich. Until he decided to justify his career to the New York Times. Background:

No one was more influential -- or more terrifying, some would say -- than Paul R. Ehrlich,

a Stanford University biologist... He later went on to forecast

that hundreds of millions would starve to death in the 1970s, that 65

million of them would be Americans, that crowded India was essentially

doomed, that odds were fair "England will not exist in the year 2000."

Dr. Ehrlich was so sure of himself that he warned in 1970 that "sometime

in the next 15 years, the end will come." By "the end," he meant "an

utter breakdown of the capacity of the planet to support humanity."

Okay, here's Ehrlich's side of the story:

After

the passage of 47 years, Dr. Ehrlich offers little in the way of a mea

culpa. Quite the contrary. Timetables for disaster like those he once

offered have no significance, he told Retro Report, because to someone

in his field they mean something "very, very different" from what they

do to the average person.

In the video interview, Ehrlich elaborates:

I was recently criticized because I had said many years ago, that I would bet that England wouldn't exist in the year 2000. Well, England did exist in the year 2000. But that was only 14 years ago... One of the things that people don't understand is that timing to an ecologist is very very different than timing to an average person.

Whenever smart people say things that strike me as absurd, I fear that this is what they're thinking. But it seems paranoid. What expert with a shred of integrity would intentionally pull this bait and switch? Yet we have it from Ehrlich's own mouth. He wasn't wrong. Neither did he lie. He just deliberately used words that meant one thing to him and a totally different thing to almost everyone who heard them.

Notice that if this excuse were generally permissible, no one could even be wrong, much less dishonest. The horror!

True, this hardly proves that Ehrlich's intellectual sin is widespread. But at least it's an existence theorem. Some people really are doing the unspeakable. And given the intense incentives to never confess such activities, a single high-profile confession makes me fear they're widely done. Ehrlich makes me feel like an epistemic germaphobe. Invisible corruption really could be swirling all around me...

June 3, 2015

Why Is Illegal Immigration So Low?, by Bryan Caplan

Even so, observed levels of immigration immigration are puzzlingly low. Let's stick with Mexico for simplicity. $3000 is a lot for a Mexican farm worker in Mexico, but not so much for a Mexican farm worker in the U.S. Suppose annual farm pay in Mexico is $1500, versus $15,000 in the U.S. That's a raise of $13,500 a year. Once he arrives, a Mexican worker could recoup his smuggling fee in under 12 weeks. Why then do most stay home?

True, these numbers ignore the horrors of the border

crossing. They are bad, but still seem modest compared to the magnitude

of the gain. A 0.1% risk of death is a pretty high estimate. According to standard calculations, pampered Americans would only pay $7000 or so to avoid

that risk. For would-be Mexican immigrants, even $1000 seems high.

Another major flaw in these calculations is that they assume that paying a human smuggler gets you into the U.S. for sure. In reality, the success rate is around 50%. The expected cost of crossing into the United States is therefore roughly double what it seems.

But neither of these sensible adjustments do much to resolve the puzzle. Add $1000 danger cost to the $3000 out of pocket cost. Then divide the sum by the probability of successful crossing. It implies that, on average, Mexicans recoup their full smuggling costs in 31 weeks. That's still a great return on investment - 167% per year.

What other factors are at work? One story I've heard is that illegal immigrants' expected gain is much lower than it seems because they only earn American wages if employed. But this seems a trivial factor. Illegal immigrants' unemployment risk is only slightly higher than natives'. And don't forget there's unemployment risk back in Mexico, too.

George Borjas suggests that people's strong attachment to their homeland deters migration. He's right about the general phenomenon, but grossly exaggerates the magnitude. In any case, feelings of attachment vary widely, and current immigration is far below potential. So you would still expect the marginal illegal immigrant's attachment to Mexico to be mild, leaving the puzzle intact.

The key factor, in my view, is quite different: Illegal immigration is relatively low because would-be immigrants have crummy credit and insurance options.

1. Crummy credit options. Most rural Mexicans can't just go to the bank to get an illegal immigration loan. Nor can they pay a coyote with a credit card. They start in a desperate situation with a lousy credit rating. To cross the border, they have to save years' worth of their own income, borrow years' worth of income from similarly desperate relatives and friends, or pay frighteningly high black market rates. When economists invoke such arguments to explain Americans' behavior, I'm skeptical. For poor people in developing countries, though, credit constraints are clearly a big deal.

What behavior economists call "debt aversion" amplifies the credit problem. Most human beings dislike "being in debt," even when the debt quickly pays for itself.

2. Crummy insurance options. Rural Mexicans can't readily buy "illegal immigration insurance." So when they finally accumulate their nest egg to cross the border, they're risking their life savings. 50% chance of crossing the border and entering the land of plenty, 50% of losing their nest egg and getting sent back to Mexico. A terrifying gamble. The black market could offer such insurance, of course, but would-be customers are right to worry they'll never get to collect.

Various choice-under-uncertainty anomalies probably amplify the insurance problem.

And that's the heart of my story. In a free market, of course, poor Mexicans would have access to reputable international lenders and insurers. But neither the U.S. nor the Mexican government would tolerate major First World corporations financing illegal migration.

I hope no one will mistake my analytical approach for lack of sympathy with illegal immigrants' plight. In a just world, they could enter the land of opportunity for the price of a bus ticket. My point is that relatively low levels of immigration do not show that the seemingly immense gains of border crossing are illusory. The gains are genuine. They're just hard for people in desperate poverty to realize with only the black market to help them.

HT: Partly inspired by a Facebook exchange with Bill Dickens, and Alex Nowrasteh's request.

(10 COMMENTS)

3 Answers from Alex Nowrasteh, by Bryan Caplan

1. How much higher would cumulative Mexican immigration since 1986 have

been if the IRCA's employer sanctions hadn't been imposed?

Temporary migration would've been higher AND more illegal immigrants would have permanently settled in the United States.2. How

much higher would cumulative Mexican immigration since 1986 have been

if the IRCA's border security boost hadn't been imposed? (Your comments

seem to suggest that it actually would have been lower, since guest workers wouldn't have bothered to bring their families).

Temporary Mexican migration would've been higher, BUT fewer of them would've settled here permanently.3. How much higher would cumulative Mexican immigration since 1986 have been if the IRCA's hadn't been passed at all?

More Mexican workers would've migrated BUT many fewer of themAlex closes with a question I was coincidentally planning on addressing: "If the benefits of immigration are as great as we like to argue, why are there so few illegal immigrants?" Answer coming soon!

would have permanently settled here as immigrants. The circular flow of

1965-1986 would have continued and probably increased. Without the amnesty, there would've been roughly 2.7 million fewer Mexicans with green cards, which would've meant many fewer green cards for Mexicans in the future.

P.S. My online immigration class starts tonight at 9 PM EST.

(1 COMMENTS)

June 2, 2015

Can Inequality Misperceptions Save Selfish Voting?, by Bryan Caplan

[Regression results here.]

OK, here's Table 9 from our paper, with an extra column where I've added the respondent's self-placement on the 1 to 10 scale (we interpret this as being about incomes, but the question's wording is: "In our society there are groups which tend to be towards the top and groups which tend to be towards the bottom. Below is a scale that runs from top to bottom. Where would you put yourself now on this scale?").

Self-placement on the scale is significant. The effects of perceived inequality remain significant and similar to those in the previous column. So both a belief that one is low on the social scale and a belief that inequality is high are associated with a stronger demand for government redistribution. The country-wide shared belief on the level of inequality seems to matter more than the individual's idiosyncratic opinions (i.e his or her divergence from the national average belief about inequality).

P.S. Note that I can't make a causal claim based on just these data.

[Bryan Caplan again.]

As usual, it's crucial to focus on the magnitude of the coefficients, not mere statistical significance. Since the perceived Gini coefficient, like the actual Gini coefficient, is bounded between 0 and 1, these updated results imply that:

1. Moving an individual's perceived status from the minimum to the maximum has the same effect on redistribution preferences as increasing the individual's perceived Gini coefficient by .51 - a pretty large effect.

2. Moving an individual's perceived status from the minimum to the maximum

has the same effect on redistribution preferences as increasing the average perceived Gini coefficient in his country by .13 - a modest effect.

The story, in short, is that redistributive preferences are primarily shaped by overall political culture. If most people in your country see a lot of inequality, you'll probably support a lot of redistribution - even if you're high status and don't think there's a lot of inequality! Within each political culture, however, your perceptions about your own status and overall inequality are comparably important.

(1 COMMENTS)

3 Questions for Alex Nowrasteh, by Bryan Caplan

1. How much higher would cumulative Mexican immigration since 1986 have been if the IRCA's employer sanctions hadn't been imposed?

2. How much higher would cumulative Mexican immigration since 1986 have been if the IRCA's border security boost hadn't been imposed? (Your comments seem to suggest that it actually would have been lower, since guest workers wouldn't have bothered to bring their families).

3. How much higher would cumulative Mexican immigration since 1986 have been if the IRCA's hadn't been passed at all?

P.S. Do your answers account for diaspora dynamics?

What do you think, Alex?

(0 COMMENTS)

Nowrasteh on the 1986 Immigration Act, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan,

I enjoyed your blog post. A few thoughts:

The bigger cost of IRCA was its boost of border

security, ending the 'salutary neglect' of immigration laws on the SW

border from the end of the Bracero Program in 1964 until 1986. When

that happened, temporary Mexican migrants were locked in by immigration

enforcement that made it more expensive to cross the border.

Massey's figure 7 shows a decline in the probability of returning that coincides with IRCA: http://www.iza.org/conference_files/amm2011/massey_d1244.pdf#page=29

The cross-border flow during that period of

salutary neglect was huge, but the net increase in US population was

relatively small. An estimated 26.7 million entries of unauthorized

Mexican migrants into the United States from 1965 to 1985 and 21.8

million departures to Mexico, yielding a net increase of just 4.9

million over 20 years. For lawful migrants, the return rate was lower

but fluctuated between 20 percent and 30 percent in the 1970s and 1980s.

I quote from Massey's book here: http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa719_1.pdf#page=4

IRCA mandated a 50% increase in border patrol staffing. CBP staffing by border sector increased from early 1990s: http://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/BP%20Staffing%20FY1992-FY2014_0.pdf

Here's a graph of border patrol staffing by sector from 1980: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R42138.pdf#page=19

There are many other ways to measure the

intensity of border enforcement, such as line-watch hours. Also, about

42% of unauthorized immigrants entered legally and overstayed their

visas.

If IRCA was combined with a workable guest worker

visa program for low-skilled workers then I think it would have

substantially reduced the flow of unauthorized immigrants after 1986,

but the small reforms to the H2 visa didn't nearly go far enough. If a

sufficiently large Bracero 2.0 was created with IRCA, it could've been

worth it. http://www.cato.org/blog/guest-worker-visas-can-halt-illegal-immigration

When the workers can't go back and forth, their

families will come north. The biggest impact of IRCA was that it locked

in many unauthorized immigrants who otherwise would have left. The

PATRIOT Act and post-9/11 border security bonanza sealed that

effect.

Alex

P.S. Alex's father is director Cyrus Nowrasteh. Don't miss his The Stoning of Soraya M.

June 1, 2015

The Psychology of Trolling, by Bryan Caplan

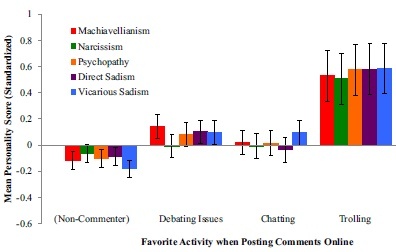

BTP combines questions about internet usage with a range of control variables, plus standard measures of the so-called "Dark Tetrad" - the personality traits of psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism, and sadism. What they find:

That Figure 1:A total of 23.8% of participants

A multivariate analysis on the Dark Tetrad revealed a significant effect of activity preference: Wilks' �� = 0.97, F(20, 1646.00) = 1.65, p = .03. Inspection of the pattern depicted in Fig. 1

expressed a preference for debating issues, 21.3% preferred chatting,

2.1% said they especially enjoy making friends, 5.6% reported enjoying

trolling other users, and 5.8% specified another activity. The remaining

41.3% of participants were non-commenters. Because of low endorsement

rates of the "making friends" option, we combined that category with the "other" category in the following analyses.

confirmed that, as expected, the Dark Tetrad scores were highest among

those who selected trolling as the most enjoyable activity.

Furthermore:

...Dark Tetrad associations were largely due to overlap with sadism. When

their unique contributions were assessed in a multiple regression, only

sadism predicted trolling on both measures (trolling enjoyment and GAIT

scores). In contrast, when controlling for sadism and the other Dark

Tetrad measures, narcissism was actually negatively related to trolling

enjoyment.

Please control your Dark Tetrad in the comments.

(0 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers