Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 122

May 10, 2015

Civil and Economic Liberties Under the Shah, by Bryan Caplan

Civil liberties under the Shah:

The Shah's crucial decade from 1965 to 1975 was also critical for the regime's cultural politics. Iran in this period was a discordant combination of cultural freedoms and political despotism - of increasing censorship against the opposition but increasing freedoms for everyone else. It is far from hyperbole to claim that during the sixties and seventies, Iran was one of the most liberal societies in the Muslim world in terms of cultural and religious tolerance, and in the state's aversion to interfere in the private lives of its citizens - so long as they did not politically oppose the Shah. Indications of this tolerance were many: from the quality of life of Iran's Baha'i and Jews to the artistic innovations and aesthetic avant-gardism of the Shiraz Art Festival...Economic liberties under the Shah:

Much to the consternation of the Shiite clergy in this period, the Baha'i enjoyed freedom and virtual equality with other citizens. The same was true about Iranian Jews - some 100,000 of the them, who had lived in Iran for over 3,000 years. In the words of David Menasheri, it was the Jews' "golden age," wherein they enjoyed equality with Muslims and in terms of their per capita incomes "they might have been the richest Jewish community in the world." Some of the most innovative and successful industrialists, engineers, architects, and artists were either Jewish or Baha'i...

In a fascinating speech on the floor of the Senate, he [Iranian senator and industrialist Qassem Lajevardi] offered a de facto manifesto for Iran's nascent industrialist class...Strong on civil liberties, weak on economic liberties - it almost seems like American liberals should have liked the Shah. The favorable theory is that liberals cared more about democracy than getting their preferred policies. The unfavorable theory is that liberals knew next to nothing about the Shah's actual policies, and opposed him chiefly for the traditional authoritarianism he symbolized rather than what he actually did - or how he compared to plausible alternatives.

Lajevardi began his remarks by pointing out the startling fact that 103 of the 104 government-run companies were losing money - the only one that showed any profit was the oil company. He also talked of the dangers or price control, knowing well the Shah's proclivity to use force to control prices, going so far as deputizing an army of students to identify and, if necessary, arrest businessmen accused of price gouging. The policy angered not just modern industrialists like Lajevardi but also members of the bazaar, long a bastion of support for the moderate opposition and for the clergy. Nowhere in the world, Lajevardi said, had the effort to forcefully control prices led to success. He went on to also criticize the government policy of arbitrarily deciding workers' wages. Wages, he said, must correlate with productivity and cannot, as was the case in Iran, be treated as a political bonus. Industrialists will invest, he said pointedly, only if they are allowed to make a fair profit. By then, a massive flight of capital from Iran had already started - a flight that would be redoubled when the political situation deteriorated.

HT: Mehi Haghani

(0 COMMENTS)

May 7, 2015

The Government of Bad Manners, by Bryan Caplan

We teach children to say "I'm sorry" when they've needlessly harmed others - even if the harm was done unintentionally or in good faith.

So riddle me this:

1. Why doesn't the IRS send thank you notes to taxpayers - especially the biggest taxpayers?

2. Why don't lawmaking bodies apologize to marijuana users - not to mention anyone who served jail time for a marijuana offense - when they decriminalize marijuana?

Whether or not you've got an explanation, feel free to add other examples of governments' bad manners in the comments...

HT: Partly inspired by a conversation with Miles Kimball

(21 COMMENTS)

May 6, 2015

The Neighborhood of Happiness, by Bryan Caplan

General traits of the person have rather strong relationships to happiness. The largest difference reflects the Social Class of Community (SCC) in which the teenagers live. SCC was computed on five levels of increasing affluence: Poor (mostly single-parent, unemployed), Working Class, Middle Class, Upper-Middle Class and Upper Class. Contrary to expectations, the highest level of happiness was reported by young people living in Working Class communities, then by those in Middle Class, Poor, Upper Class and finally Upper Middle Class environments. An ANOVA in which all the demographic variables (i.e. age, gender, SCC, Ethnic background) were entered showed the strongest effect for SCC (F = 8.09, p < 0.0001).Their take on their findings:

What is surprising is the lack of positive correlation between happiness and financial affluence. That teenagers from working-class, and even impoverished backgrounds should be happier than upper-middle-class teenagers living in exclusive suburban communities is difficult to explain. It is possible that some selection bias is responsible for this result: perhaps relatively more students from lower class backgrounds who were happy volunteered and completed the ESM compared with more affluent students. But the rates of volunteering had been high in all schools, including the ones in the inner city neighborhoods, so this explanation could not account entirely for the findings. Perhaps in the affluent suburban sub-culture it is not "cool" to admit to being happy. Or perhaps material well-being is in fact an obstacle to happiness. Recent research on materialism suggests that excessive concern with consumer goods and material possessions is inversely related with positive developmental outcomes (Schmuck and Sheldon, 2001).Not what I expected, but I'm hardly shocked. Are you?

(17 COMMENTS)

May 5, 2015

Orwell as Public Choice Socialist, by Bryan Caplan

There really ought to be a paper on George Orwell and Public Choice. Thanks to Loyola University senior Michael Makovi, there finally is. He's done a great job - "George Orwell as Public Choice Economist," forthcoming in The American Economist, is history of thought you can really sink your teeth into. Here are some highlights.

Abstract:

George Orwell is famous for hisFleshed-out version:

two final fictions, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. These

two works are sometimes understood to defend capitalism against socialism. But

as Orwell was a committed socialist, this could not have been his intention.

Orwell's criticisms were directed not against socialism per se but

against the Soviet Union and similarly totalitarian regimes. Instead, these

fictions were intended as Public Choice-style investigations into which

political systems furnished suitable incentive structures to prevent the abuse

of power.

Although

Orwell certainly was distrustful of individuals and suspected them of being

liable to abuse their power, he was also interested, as we shall see, in what

political institutions might affect their liability to abuse their

power. While Orwell's skepticism of political power and his fear of individual

abuse of that power are significantly consistent with Public Choice, in fact

Orwell's concerns went much further. Therefore Orwell was not only a skeptic of

political power but he was also concerned with political institutions and their

incentive structures, and thus a practitioner of Public Choice economics.

In this way, through the Public

Choice interpretation of Orwell, we may reconcile the sensibility and

straightforwardness of the conservative interpretation of Animal Farm

and Nineteen Eighty-Four as having been written to oppose socialism,

with the actual fact that Orwell was a socialist. For after all, Orwell was and

always remained an advocate of democratic socialism and he could not have been

a critic of collectivism per se. At the same time, the conservative

interpretation seems so sensible and appears to so readily agree with the texts

precisely because it is not altogether wrong. Orwell was not opposed to

socialism per se as the conservative interpretation suggests, but he was

opposed to a particular kind of socialism, viz. any form of socialism

which turned totalitarian because it neglected to provide suitable political

institutions to mitigate the abuse of power. The conservative interpretation of

Orwell's fictions as anti-socialist thus carries an important kernel of truth. Therefore,

Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were not intended as criticisms

of the abstract economics of collectivism in theory, but rather of the

political dynamics of "decayed communism," non-democratic forms of collectivism

in practice. Though these two fictions have many differences - Animal Farm

being an allegorical beast fable about the very recent past, Nineteen-Eighty

Four a relatively realistic dystopian novel set in the future - it is this

polemical intention which they share in common.

The Public Choice interpretation of Orwell helps us understand that Orwell was

opposed to a particular form of socialism -the totalitarian kind - and why. In

doing so, this interpretation allows us to square the sensibility of the

conservative anti-socialist interpretation with the fact that Orwell was a

socialist.

Orwell was totally a socialist:

Orwell

thought that "Capitalism, as such, has no room in it for any human

relationship; it has no law except that profits must always be made" ("Will

Freedom Die with Capitalism?"[1941] 1683).

Similarly, in "The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius"

(1941), which he wrote during World War II, Orwell defined "economic liberty"

as "the right to exploit others for profit" (Essays 294). Furthermore,

discussing Britain's ability to wage a defensive war, he continued,What this war has demonstrated is that private

capitalism - that is, an economic system in which land, factories, mines and

transport are owned privately and operated solely for profit - does not work.

It cannot deliver the goods. (Ibid. 315; emphasis in original)In

the same essay, Orwell came to the conclusion thatLaissez-faire capitalism is dead. The choice lies

between the kind of collective society that Hitler will set up and the kind

that can arise if he is defeated. (Ibid. 344)

More:

Unlike most contemporary socialists, however, Orwell abhorred intellectual victory by definition. He freely admitted that Nazism, like Communism, was socialist:But

if Orwell was a socialist, the question remains, why? What about socialism

appealed to him? Thankfully, Orwell tells us in his autobiographical "Preface

to the Ukranian Edition of Animal Farm" (1947):I became pro-Socialist more out of a disgust

with the way the poorer section of the industrial workers were oppressed and

neglected than out of any theoretical admiration for a planned society. (Essays

1211)

Thus, we should not expect that Orwell necessarily read

widely in economics, and certainly it seems that even if he had, this was not

what influenced him towards socialism. Instead, it appears that what Orwell

rejected more than anything else was any hierarchy or inequality which he

perceived to be socially unnecessary (Orwell, "Review of The Machiavellians

by James Burnham" [1944] in Essays 525; Orwell, "James Burnham and the

Managerial Revolution" [1946] in Essays 1070; cf. Goldstein in Nineteen

Eighty-Four in Complete Novels 1100). So Orwell was a socialist

because he was an egalitarian. Indeed, according to Richard White, he was what

Marxians would disdainfully call a "utopian" socialist, a socialist inspired by

ethical and moral views, determined to institute socialism for the sake of

social justice, whereas Marxists would consider socialism to be an amoral

historical inevitability (White, "George Orwell: Socialism and Utopia").

Furthermore:Orwell

even argued that by virtue of their undemocratic and collectivist nature, Nazi

fascism and Soviet communism were essentially the same thing, a fact which he

accused his fellow socialists of failing to appreciate:

[T]ill very recently it remained the official theory of

the Left that Nazism was "just capitalism." . . . Since nazism was not what any

Western European meant by socialism, clearly it must be capitalism. . . .

Otherwise they [the Left] would have had to admit that nazism did avoid

the contradictions of capitalism, that it was a kind of socialism,

though a non-democratic kind. And that would have meant admitting that "common

ownership of the means of production" is not a sufficient objective, that by

merely altering the structure of society you improve nothing. . . . Nazism can

be defined as oligarchical collectivism. . . . It seems fairly certain that

something of the same kind is occurring in Soviet Russia; the similarity of the

two regimes has been growing more and more obvious for the last six years.

("Will Freedom Die With Capitalism?" [1941] 1684; emphasis in original)

Some amusing ridicule by Makovi:Thus,

Orwell's experiences in Spain convinced him not that socialism was a

false ideal, but that the Soviet Union and the Communists had betrayed that

ideal. Orwell "was a socialist but, ever since Spain, an anti-Stalinist

socialist and his hostility to Communism was a pervasive feature of his

political writing" (Newsinger, Orwell's Politics 97). He thought that

"Communism is now a counter-revolutionary force" (Orwell, "Spilling the Spanish

Beans" [1937] 67), working against socialism. He became inspired to expose

their duplicity and conniving, and he related

the theme of the Soviet betrayal of the cause of socialism with the

totalitarian rewriting of the past:The

Communist movement in Western Europe began as a movement for the violent

overthrow of capitalism, and degenerated within a few years into an instrument

of Russian foreign policy. ("Inside the Whale" [1940] in Essays 233f.,

quoted in Newsinger, Orwell's Politics 113)

He furthermore referred to "Russian Communism . . . [as]

a form of Socialism that makes mental honesty impossible" (Orwell, "Inside the

Whale" 235), and so Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were

written not as defections from socialism, but as attempts to redeem true

socialism from the betrayal of the Communists.

One would defend the conservativeMy main suggestion for improvement: Makovi should have heavily emphasized the parallels between Orwell's 1984 and the late great Gordon Tullock's work on dictatorship and revolution. Listen to Tullock speak:

interpretation of Orwell's fictions as anti-socialist by arguing that Orwell

was no longer a socialist anymore when he wrote them. And it would be difficult

to refute the claim that Orwell had a change of heart prior to writing his last

two major works for the same reason that it is difficult to challenge a claim

that someone had made a deathbed recantation or confession.

Another obvious area for empirical investigation concerns the expectations of the revolutionaries. My impression is that they generally expect to have a good position in the new state which is to be established by the revolution. Further, my impression is that the leaders of revolutions continuously encourage their followers in such views. In other words, they hold out private gains to them. It is certainly true that those people that I have known who have talked in terms of revolutionary activity have always fairly obviously thought that they themselves would have a good position in the "new Jerusalem." Normally, of course, it is necessary to do a little careful questioning of them to bring out this point. They will normally begin by telling you that they favor the revolution solely because it is right, virtuous, and preordained by history.Now hear the words of O'Brien in 1984:

The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interestedP.S. I'm writing an all-new dystopian role-playing game for Capla-Con 2015, June 20-21 - and you're invited! Join the Facebook group for details.

in the good of others; we are interested solely in power. Not wealth or

luxury or long life or happiness: only power, pure power. What pure

power means you will understand presently. We are different from all the

oligarchies of the past, in that we know what we are doing. All the

others, even those who resembled ourselves, were- cowards and

hypocrites. The German Nazis and the Russian Communists came very close

to us in their methods, but they never had the courage to recognize

their own motives. They pretended, perhaps they even believed, that they

had seized power unwillingly and for a limited time, and that just

round the corner there lay a paradise where human beings would be free

and equal. We are not like that. We know that no one ever seizes power

with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means, it is an

end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a

revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the

dictatorship.

P.P.S. Makovi's paper was written under the direction of Prof. William T.

Cotton in his honors English literature course, "George Orwell and the

Disasters of the 20th Century" at Loyola University, New Orleans.

(17 COMMENTS)

Because Freedom, by Bryan Caplan

The ridicule is often unfair on its own terms. There are consequentialist arguments for these libertarian positions, if you care to listen. Still, critics correctly sense that even self-styled consequentialist libertarians have a strong pro-freedom, anti-government presumption. If the consequences of government action are anywhere in the vicinity of "bad overall," libertarians frequently do say, "Because freedom" to get over the hump.

What few critics care to admit, though, is that they too routinely makes the same intellectual move. Almost everyone does. Whenever an honest assessment of consequences of government action fails to yield ideologically palatable answers, non-libertarians retreat to "Because freedom" too.

Why not ban Satanism? Because freedom.

Why shouldn't societies where homophobes vastly outnumber gays legally persecute gays? Because freedom.

Why not punish strangers who have unprotected sex without being tested for STDs? Because freedom.

Why not forbid climbing Mount Everest? Because freedom.

Why not require adults to get a Non-Alcoholic's License to buy alcohol? Because freedom.

Why let the Nazis march in Skokie? Because freedom.

Why let parents prevent grandparents from visiting their grandchildren? Because freedom.

Sure, you can offer consequentialist justifications of these policies. But if you're convinced all of these consequentialist cases are clear-cut against government intervention, you're guilty of wishful thinking. Honestly, can you point to anyone who knows enough to do passable cost-benefit analysis of all of these issues? Doubtful. The argument that gets you to your conviction is "Because freedom."

Not that there's anything wrong with that. "Because freedom" isn't the only morally relevant political argument. But truth be told, it's one of the best.

(20 COMMENTS)

May 3, 2015

School Networking: Friends versus Connections, by Bryan Caplan

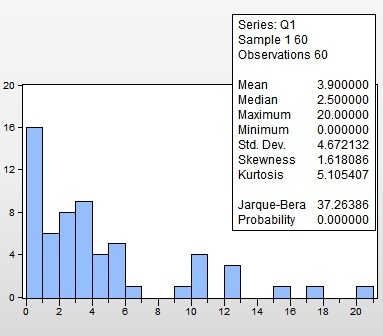

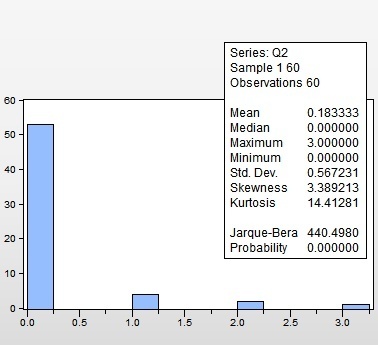

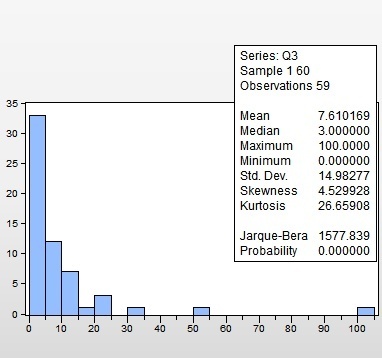

At least in this admittedly self-selected sample, the two big patterns are:

1. People make lots of friends at school at all academic levels.

2. People make few professional connections at school at any academic level.

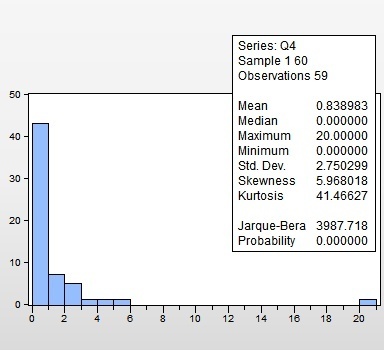

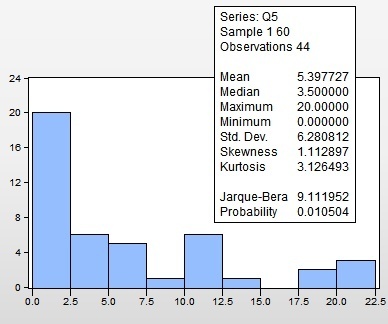

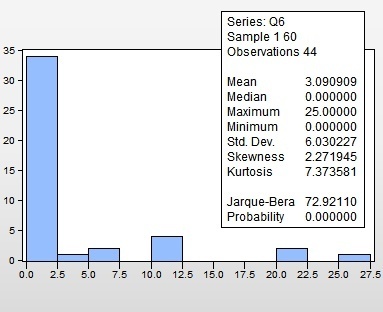

The histograms...

Question 1: How many people you met in K-12 are you still friends with?

Question 2: How many people you met in K-12 do you professionally interact with?

Question 3: How many people you met in college are you still friends with?

Question 4: How many people you met in college do you professionally interact with?

Question 5: How many people you met in graduate/professional school are you still friends with?

Question 6: How many people you met in graduate/professional do you professionally interact with?

As you might expect, people make the most professional contacts in graduate/professional school: .2 for K-12, .8 for undergraduate, 3.1 for graduate/professional. But the median is zero at all three levels.

You could argue that since my questions specified current interaction, it masks the full impact of professional connections. Maybe people use connections to jump start their careers when they're young, then gradually lose touch. However, simple regressions of professional contacts on age lend almost no support to this story. The average number of contacts lost per year is .01 for K-12, .03 for undergraduate, and .03 for graduate/professional.

P.S. Read this before you invoke "the strength of weak ties."

HT: Caleb Fuller, for tabulating the results. When respondents gave a finite range, I used the midpoint. When they gave an infinite range (e.g. 20+), I used the minimum.

(0 COMMENTS)

April 30, 2015

Kahneman and Renshon on Hawkish Biases, by Bryan Caplan

The role of overconfidence:

A group of researchers has recently documented the link between overconfidence and war in a simulated conflict situation (Johnson, McDermott et al. 2006). Johnson et al. conducted an experiment in which participants (drawn from the Cambridge, MA area, but not exclusively composed of students) played an experimental wargame. Subjects gave ranked assessments of themselves relative to the other players prior to the game, and in each of the six rounds of the game chose between negotiation, surrender, fight, threaten or do nothing; they also allocated the fictional wealth of their "country" to either military, infrastructure or cash reserves. Players were paid to participate and told to expect bonuses if they "won the game" (there was no dominant strategy and players could "win" using a variety of strategies). Players were generally overly optimistic, and those who made unprovoked attacks were especially likely to be overconfident (Johnson, McDermott et al. 2006: 2516).3The opacity of intentions:

The consequences of positive illusions in conflict and international politics are overwhelmingly harmful. Except for relatively rare instances of armed conflicts in which one side knows that it will lose but fights anyway for the sake of honor or ideology, wars generally occur when each side believes it is likely to win -- or at least when rivals' estimates of their respective chances of winning a war sum to more than 100 percent (Johnson 2004: 4). Fewer wars would occur if leaders and their advisors held realistic assessments of their probability of success; that is, if they were less optimistically overconfident.

[P]eople tend to overestimate the extent to which their own feelings, thoughts or motivations "leak out" and are apparent to observers (Gilovich and Savitsky 1999: 167). In recent demonstrations of this bias, participants in a "truth-telling game" overestimated the extent to which their lies were readily apparent to others, witnesses to a staged emergency believed their concern was obvious even when it was not, and negotiators overestimated the degree to which the other side understood their preferences (even in the condition in which there were incentives to maintain secrecy) (Gilovich, Savitsky et al. 1998; Van Boven, Gilovich et al. 2003: 117). The common theme is that people generally exaggerate the degree to which their internal states are apparent to observers.The halo effect at work:

The transparency bias has pernicious implications for international politics. When the actor's intentions are hostile, the bias favors redoubled efforts at deception. When the actor's intentions are not hostile, the bias increases the risk of dangerous misunderstandings. Because they believe their benign intentions are readily apparent to others, actors underestimate the need to reassure the other side. Their opponents - even if their own intentions are equally benign -- are correspondingly more likely to perceive more hostility than exists and to react in kind, in a cycle of escalation. The transparency bias thus favors hawkish outcomes through the mediating variable of misperception.

[I]ndividuals assign different values to proposals, ideas and plans of action based on their authorship. This bias, known as "reactive devaluation," is likely to be significant stumbling block in negotiations between adversaries. In one recent experiment, Israeli Jews evaluated an actual Israeli-authored peace plan less favorably when it was attributed to the Palestinians than when it was attributed to their own government, and Pro-Israeli Americans saw a hypothetical peace proposal as biased in favor of Palestinians when authorship was attributed to Palestinians, but as "evenhanded" when they were told it was authored by Israelis. In fact, the phenomenon is visible even within groups. In the same experiment, Jewish "hawks" perceived a proposal attributed to the dovish Rabin government as bad for Israel, and good for the Palestinians, while Israeli Arabs believe the opposite (Maoz, Ward et al. 2002).My main disappointments.

1. While Kahneman and Renshon admit the possibility that hindsight bias clouds their judgment, they don't take strong steps to defuse it. They could have gone through their paper bias-by-bias, asking, "Could this also lead to dovish bias? Does it?" I'm probably much more dovish than either Kahneman or Renshon, but behavioral economists really need to search harder for tensions between their psychology and their decidedly left-leaning politics.

2.. Kahneman and Renshon don't even cite Tetlock's work showing that political experts are bad forecasters, especially on issues that are controversial among experts. You could say that this isn't really a "hawkish bias." But combined with mildly deontological moral views on killing innocents, it is.

3. Kahneman and Renshon don't even mention Social Desirability Bias. This seems like a big omission, because "Let's stand up for our country" sure sounds better than "Let's swallow our pride to avoid costly conflict," "Maybe we'll lose" or "Perhaps the other side has reasonable grievances against us."

(0 COMMENTS)

April 29, 2015

Meritocracy Bleg, by Bryan Caplan

HT: Garett Jones

(18 COMMENTS)

April 28, 2015

School Networking Bleg, by Bryan Caplan

1. How many people you met in K-12 are you still friends with?

2. How many people you met in K-12 do you professionally interact with?

Questions for college attendees:

3. How many people you met in college are you still friends with?

4. How many people you met in college do you professionally interact with?

Questions for graduate/professional school attendees:

5. How many people you met in graduate/professional school are you still friends with?

6. How many people you met in graduate/professional do you professionally interact with?

Please include your age and major in your response.

(70 COMMENTS)

Return to Dorms Bleg, by Bryan Caplan

(13 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers