Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 121

June 1, 2015

Was the Reagan Amnesty Bad for Immigrants?, by Bryan Caplan

If Washington still wants to "do something" about immigration, we propose a five-word constitutional amendment: There shall be open borders.

Perhaps this policy is overly ambitious in today's world, but the U.S.

became the world's envy by trumpeting precisely this kind of heresy. Our

greatest heresy is that we believe in people as the great resource of

our land. Those who would live in freedom have voted over the centuries

with their feet. Wherever the state abused its people, beginning with

the Puritan pilgrims and continuing today in places like Ho Chi Minh

City and Managua, they've aimed for our shores. They -- we -- have

astonished the world with the country's success.The nativist

patriots scream for "control of the borders." ...Does

anyone want to "control the borders" at the moral expense of a

2,000-mile Berlin Wall with minefields, dogs and machine-gun towers?

Those who mouth this slogan forget what America means. They want those

of us already safely ensconced to erect giant signs warning: Keep Out,

Private Property.The instinct is seconded by the "zero-sum"

mentality that has been intellectually faddish this past decade. More

people, the worry runs, will lead to overcrowding; will use up all our

"resources," and will cause unemployment. Trembling no-growthers cry

that we'll never "feed," "house" or "clothe" all the immigrants --

though the immigrants want to feed, house and clothe themselves.

What shocked me, though, is that Bartley's editorial asks Reagan to veto the Simpson-Mazzoli bill:

Simpson-Mazzoli, we are repeatedly told, is a carefully crafted

compromise. It is in fact an anti-immigration bill... If it survives conference, President Reagan

would be wise to veto it as antithetical to the national self-confidence

his administration has done so much to renew.

Simpson-Mazzoli is the very bill that ultimately became the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 that modern nativists so revile for amnestying millions of illegal immigrants. My first reaction was that Bartley was being a libertarian purist - focusing on minor downsides for immigrants instead of judging the overall package. But after pondering the details of the 1986 bill, I've reconsidered.

Key point: In addition to the amnesty, the bill made it illegal to hire or recruit illegal immigrants knowingly. In other words, before 1986, it was legal to knowingly hire and recruit illegal immigrants! Once immigrants were over the border, U.S. employers could hire them without fear. Sure, illegal workers were still vulnerable to deportation, but employers are easier targets for legal prosecution. Employees and employers can both hide from regulators, but only employees can run.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act was a blessing for illegal immigrants who arrived before 1982 (the amnesty cutoff), but a disaster for all the illegal immigrants who arrived since. What's the net effect for immigrants? You've got to look at the numbers. As opponents of the act often point out, illegal immigration exploded after the amnesty. The population climbed from around two million in 1983 to eleven million today. From nativists' point of view, this was a disaster because the 1986 act was supposed to make illegal immigration go down. From a principled pro-immigrant point of view, though, the disaster was that the 1986 act helped a stock of a few million current immigrants at the expense of an indefinite flow many millions of subsequent immigrants.

You could argue that the 1986 precedent caused the massive increase in illegal immigration by fostering hope of future amnesties. But suppose the amnesty never happened, but illegal immigrants knew that U.S. employers could hire them without fear. Wouldn't illegal immigration would have been higher still? If you're a prospective illegal immigrant, the vague possibility of getting amnesty in a decade or three is far less motivating than the strong probability of getting a decent job without papers as soon as you clear the border.

On balance, then, Bartley's dim view of the 1986 act seems justified. Indeed, the best case against Bartley is probably that if the 1986 act hadn't passed, Congress would have eventually adopted employer penalties without an amnesty. But I don't see any President from Reagan to Obama having both the will and the support to make that happen. Am I wrong?

(4 COMMENTS)

May 27, 2015

Systematically Biased Beliefs About Inequality, by Bryan Caplan

Fortunately, thanks to noble exceptions, the intellectual climate is slowly improving. Case in point: Gimpelson and Treisman's new NBER working paper on "Misperceiving Inequality." The paper's great from beginning to end, but here are some highlights.

Motivation:

What if the masses have little notion of how much wealth the elites have accumulated and whether the gap is growing or shrinking? What if even the rich cannot gauge how strong is the motive for the poor to revolt? In such cases, the neat link between actual inequality levels and political outcomes evaporates. The goal of this paper is to show that such uncertainty and misperception are ubiquitous. We present evidence from a number of large-scale, cross-national surveys that in recent years ordinary people have known little about the extent of income inequality in their societies, its rate and direction of change, and where they personally fit into the distribution. What they think they know is often wrong. This finding is robust to data sources, definitions, and measurement instruments. For instance, perceptions are no more accurate if we reinterpret them as being about wealth rather than income.Fun self-referential argument:

A strange inconsistency underlies much recent scholarship. On the one hand, theories assume that individuals correctly perceive the income distribution. On the other hand, scholars complain that the data available to test these same theories--in developed democracies and, even more so, in poorer, less free societies--are "dubious" (Ahlquist and Wibbels 2012) and "massively unreliable" (Cramer 2005). Yet, if experts throw up their hands at the quality of the data, it is strange to assume the general public is better informed. And if analysts fault the figures available today--despite the most sophisticated statistical agencies the world has ever seen--data quality must have been much worse during the nineteenth century heyday of revolution and democratization.Main conclusions:

The implications of this point for theories of redistribution, revolution, and democratization, are far reaching. If these are to be retained at all, they need to be reformulated as theories not about actual inequality but about the consequences of beliefs about it, with no assumption that the two coincide. We show that, although actual levels of inequality--as captured by the best current estimates--are not related to preferences for redistribution, perceived levels of inequality are... The actual poverty rate correlates only weakly with the reported degree of tension between rich and poor; but the perceived poverty rate is a strong predictor of such inter-class conflict.Gimpelson and Treisman heavily rely on the ISSP survey, which showed respondents around the world five different income distributions, then asked them which one best-described their own country. Results:

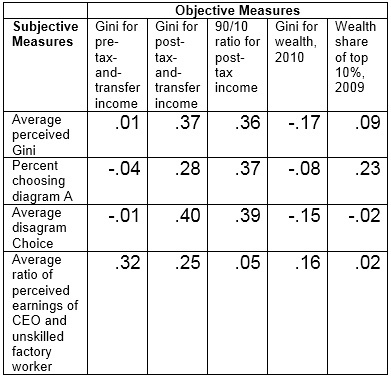

Respondents turn out to be wrong about their country's income distribution most of the time. Worldwide, 29 percent of respondents chose the "correct" diagram if we refer to their country's post-tax-and transfer Gini and 24 percent got it right if we use the pre-tax-and-transfer measure. For reference, a purely random choice among the five possible answers would get the answer right 22.5 percent of the time for post-tax-and-transfer incomes and 20 percent of the time for pre-tax-and-transfer incomes.12 In other words, respondents worldwide were able to pick the "right" diagram only slightly more often than they would have done if choosing randomly.G&T have a neat table summarizing the flimsy correlations between real and perceived inequality. Since it's hard to read, I've transcribed it:

[...]

Were most people at least close? To check this, we examined what proportion of respondents were within one diagram of the correct one (for instance, if the correct diagram was B, we measured how often the respondents picked A, B, or C). With only five options to choose between, getting within one place of the correct option is not a very difficult task. Picking randomly among the five diagrams, respondents should be within one place of the correct diagram 68 percent of the time if focusing on post-tax-and-transfer income and 43 percent of the time if focusing on pre-tax-and-transfer income. In fact, for post-tax-and-transfer income they were right 69 percent of the time, just one percentage point better than if they picked randomly.

G&T go on to show that people around the world imagine they're near the median income. Few people think they're poor, and almost no one thinks they're rich. Only 1% of people who own a second home think they're in the top decile of their country's income distribution!

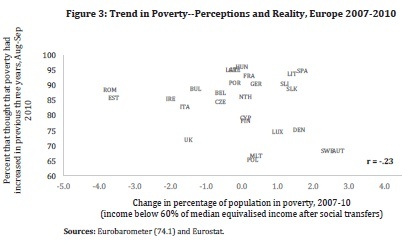

Owning two houses is usually a sign of wealth. In all 40 LiTS countries, at most one in four respondents said that his or her family owned a second residence, and in all but three countries the frequency was less than one in six. Yet most such property owners did not consider themselves especially rich. On average, 60 percent of the secondary residence owners placed themselves in the bottom half of the income distribution. In Uzbekistan, only three percent of respondents lived in households with a second residence, yet almost two thirds of these thought their incomes were below the national median. Such anomalies were somewhat rarer in the developed countries. Still, in France, Italy, and Great Britain, 40 percent or more of second residence owners placed themselves in their country's bottom half.What about changes in inequality? Here, the correlation between reality and belief is actually negative.

The coolest part of the paper, though, are the regressions of support for redistribution on objective and subjective measures of inequality. As every shrewd politician suspects, perception crushes reality:

[N]either the pre-tax nor the post-tax actual income Ginis are positively related to support for redistribution at either the country or the individual level. However, perceived inequality is highly significant in both cases. In countries where inequality was generally thought to be high, more people supported government redistribution. But demand for redistribution bore no relation to the actual level of inequality. In fact, given the average belief about inequality, higher actual inequality was associated with lower demand for redistribution. Breaking down perceptions into their general and idiosyncratic components, we found a stronger effect of the general perception in the country than of the individual's idiosyncratic perceptions. Still, both seemed to matter in the way expected.The same goes for perceived class conflict:

At the country level, post-tax-and-transfer inequality was significantly associated with greater reported tension between classes, although pre-tax-and-transfer inequality was not (Table 10, panel A). However, the effect of actual inequality was dwarfed by that of perceived inequality, which was about three times larger. And the effect of actual inequality disappears if one controls for the country's income and population (column 5)."Misperceiving inequality" has another, unstated lesson about inequality. Namely: One paper that tests the connection between objective and subjective inequality is worth a thousand that take it for granted. Read the whole thing.

(12 COMMENTS)

May 26, 2015

A Bettor's Tale, by Bryan Caplan

My Uncle, like the vast majority of people living in North America,

is not a fan of the idea of open borders. In fact, he's vehemently

opposed. The first time I told him I favored the idea, his reaction was,

well, a very hard to forget combination of incredulity and indignation.

Free trade in goods was fine he maintained but to extend the idea to

labor... madness!

We would debate the issue via e-mail and when we saw

each other in person. During one such visit, he was telling me, as he

had repeatedly, that support for open borders was just one hell of an

out there idea. I normally responded by saying that an idea being

outside the mainstream hardly meant it was a bad idea. After all,

support for many things that are now sacrosanct in our culture once only

enjoyed the support of a few articulate radicals.

However, at that

moment, a different response came to mind. I knew that The Wall Street

Journal had editorialized in favor of open borders under Robert Bartley.

My Uncle, a fiscal conservative who works in the financial sector,

surely could not deny that the Wall Street Journal was an impeccably

mainstream publication. So I said "Is The Wall Street Journal crazy? It

has editorialized in favor of open borders." He did not believe that the

Journal would ever be so "out there." Knowing I was right, and inspired

by Bryan, I suggested we bet to settle the dispute.

The terms were

clear: 50 bucks would be owed to me if I could find an editorial by the

Journal calling for open borders and 50 owed to him if I couldn't. A

30 second Google search later and there it was: an editorial by the

Wall Street Journal endorsing my ultra-marginal, insane libertarian

notion of open borders. The editorial even used the term "open borders."

My Uncle was not happy. "This is from the 80s," he protested. "Did I

say it was written yesterday? Come on Bob, the terms of the bet were

clear. Any editorial from the Journal advocating this and you owe me

50."

I really didn't feel this was sneaky since it's not like the

Journal has ever repudiated or even distanced itself from this position

and has indeed written many editorials advocating policies consistent

with the goal of ultimately opening up the borders completely. A few

minutes later, I was 50 dollars richer and he was 50 dollars poorer.

Since then, I have routinely suggested betting to settle disputes.No one

else has agreed to bet which shows you that even belligerent partisans

back off when there is a cost to being wrong.

Oh and in all fairness to my Uncle, he's a very bright, pleasant,

and successful guy. I hope to be like him in many ways but, you know,

without being terribly wrong on hugely important moral issues :)

P.S. I'd add that Mathieu's uncle is praiseworthy for betting in the first place. As I've pledged before, "When I win a bet, I will not shame my opponent, for a betting loser has

far more honor than the mass of men who live by loose and idle talk."

(15 COMMENTS)

May 25, 2015

Get Over Yourself, by Bryan Caplan

Part 1: We live in an evolutionarily novel anonymous society, so most people's opinions of me - good or ill - are inert. As long as I please key actors in my immediate social network, I do fine. Tyler Cowen's pro-Caplan stance has changed my life far more than the negative opinions of hundreds of my classmates.

Part 2: In any case, most humans are too self-obsessed to heed my eccentricities. As I often say, "We'd worry far less about what other people thought about us if we realized how little they think about us at all." In hindsight, the vast majority of the "hundreds of classmates" who seemed to dislike me were barely aware I was alive.

Part 1 seems indisputable, but Part 2's more in doubt. Last week, though, I stumbled across a mid-sized psychological literature on the "Spotlight Effect" - and learned the research is strongly on my side. Gilovich, Medvee, and Savitsky's seminal "The Spotlight Effect in Social Judgment" (Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2000) snaps together three experiments to show that individuals underestimate their social invisibility:

The research presented here supports our contention that people tend to believe that they stand out in the eyes of others, both positively and negatively, more than they actually do. Participants in Study 1 who were asked to don an embarrassing T-shirt overestimated the number of observers who noted that it was the singer Barry Manilow pictured on the shirt. Participants in Study 2 who were asked to wear T-shirts bearing the images of figures of their own choosing from popular culture likewise overestimated the number of observers who noted the individuals depicted on their shirts. Contributors to a group discussion in Study 3 thought their minor gaffes and positive contributions to the session stood out more to their fellow discussants than they actually did. It thus appears that people overestimate the extent to which others are attentive to the details of their actions and appearance. People seem to believe that the social spotlight shines more brightly onFun corollaries:

them than it truly does.

if people overestimate the extent to which others are attentive to their momentary actions and appearance, it stands to reason that they will also overestimate the extent to which others are likely to notice the variability in their behavior and appearance over time. Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon is reflected in the widespread fear of having a "bad hair day." Clearly, the fear of having such an affliction is not simply that one's hair can be recalcitrant and that rogue strands of hair can sprout in the most unfortunate places--it is that other people will notice any such aberrations that arise. But the research on the spotlight effect suggests that this concern may be often overblown. The variability that an individual readily perceives in his or her own appearance is likely to be lost on most observers. To others, one's putative bad hair days may be indistinguishable from the good. This phenomenon is hardly limited to physical appearance, of course. Academics, who frequently deliver the same lecture numerous times, are often surprised to find that marked fluctuations in their own assessment of their performance (whether they "nailed" or "bombed" a talk) are not met by corresponding fluctuations in their audiences' reactions. The variability that one so readily sees in oneself--and expects others to see as well-- often goes largely unnoticed.Followup evidence has been supportive, though note that much of it was conducted by the authors of the original research.

Parting question: How famous do you have to get before the social spotlight becomes brighter than you imagine? As far as I can tell, 10,000 Twitter followers isn't even close.

(0 COMMENTS)

May 21, 2015

When to Head for Your Bunker, by Bryan Caplan

1. When economists discuss worst-case macroeconomic scenarios, they often say stuff like, "Head for your bunker," "Dig a hole and jump in," and "Hopefully you've been hoarding canned goods."

2. When foreign policy experts discuss worst-case war foreign policy scenarios, they don't. In fact, they're likely to segue into sermons about courage, defying evil, and Churchill's "never surrender" speech.

The strangeness, in case it's not obvious, is that even another Great Depression would have a minimal body count, while a pint-sized nuclear war would kill millions. In the broad scheme of things, economic crises are disappointments, while wars are disasters.

Sure, you can use cost-benefit analysis to show that the Great Recession had a much higher social cost than a small war. But if distribution ever matters, it matters in war. Suppose a million Americans die in a nuclear inferno. With standard value of life numbers, that's a loss of $7 trillion - well below most estimates of the cost of the Great Recession. But who can doubt that a million violent deaths would have been far more tragic than the Great Recession, because the million victims lose everything they have. To quote Eastwood in Unforgiven, "It's a hell of a thing, killing a man. Take away all he's got and all he's ever gonna have."

Yes, I know that talk of bunkers, holes, and canned goods is intended as dark humor. But the humor spreads confusion nonetheless. If you live in the First World, economic crises are only a First World Problem. Major wars are macabre no matter no matter where they happen.

(0 COMMENTS)

May 20, 2015

Unlock the School Library, by Bryan Caplan

If you could change the K-12 curriculum in one small way, what would you change? My pick: Unlock the school library. By this I mean...

1. Give kids the option of hanging out at the library during every break period.

2. Give kids the option of hanging out the library in lieu of electives.

My elementary, junior high, and high schools all had marvelous libraries. But they were virtually always closed to the student body. You couldn't go during recess or lunch. And you certainly couldn't say, "Instead of taking music/dance/art/P.E./woodshop, I'll read in the library." Virtually the only time I entered a school library was when an entire class went as part of an assignment.

Unlocking the school library requires almost no resources. Simply:

1. Send one or two unskilled but mature workers to watch over the students.

2. Exile students who bother other students from the library. If you can't treat your fellow bookworms decently, you're sentenced to regular classes.

The benefits are twofold.

Intellectually, unlocking the library gives students much-needed time to explore their interests and satisfy their curiosity. You really learn a lot by reading.

Socially, unlocking the library allows students to escape pointless classes, boring teachers, and obnoxious peers. It also gives kids a chance to exercise independence and self-control.

After the novelty wears off, I expect many kids will get bored at the library. That's fine: Send them back to regular classes. But many other kids - especially nerdy kids - will seize the day. They'll finally have a sanctuary from the daily indignities of K-12 education - and a chance to learn what they want when they want. When I was a kid, unlocking the school library would have been heaven on earth.

Most educators and parents will scoff at my proposal. Why? At root, they like the idea of bossing kids around. They're so determined to make every child dance - yes, literally dance - that they're afraid to even give them the option of quietly reading in the library instead. Adults claim they're controlling children for their own good. I doubt it. As a child, I noticed that adults seemed more focused on their own egos than students' well-being - and my experiences as an adult and a parent strongly support my youthful cynicism.

Challenge to educators and parent: Prove me wrong. If you care about the children as much as you claim, you should at least experiment with my proposal. Instead of dismissing it out of hand, try unlocking the library on a small scale and see what happens.

(19 COMMENTS)

May 18, 2015

Designer Babies Are Nothing to Fear: A Reply to Dan Klein, by Bryan Caplan

The idea that technology will enable designer babies fills me withOK.

apprehension. My apprehension over designer babies would be great even

on two unrealistic assumptions: (1) That the government never got

involved in it (specifically, never made use of it or influenced the use

of it), and (2) That the technological development did not lead to

reductions in liberty, reductions prompted by results of the

development.

Designer babies would attenuate coherence with the past: One hundred

years hence, people would say, "When you watch him on the old videos, he

may not look like much, but back in the old times, Mike Tyson was

considered a pretty menacing fighter." People in the new times would not

know our sense of standard. And they would have difficulty knowing it.

Everything preceding the break, from Achilles to Rafael Nadal, would be

foreign and unintelligible.

You could say exactly the same about all the economic growth that happened since 1900. It has undeniably and dramatically "attenuated coherence with the past." I'm tempted to say "So what?," but what I really think is, "Good riddance." The world's improved beyond anything my great-grandparents could have imagined. I hope my ancestors would have had the good sense and benevolence to be happy for me. I'm happy for my super-descendents already.

People would lose a sense of historical coherence, a very importantI'm a lifelong history buff. The main thing I learn from history is that the past was awful, and the present far from satisfactory. A future society of designer babies should be more able to appreciate this lesson because they'll be beyond so many of our failures.

dimension in human meaning. But even within their time, across arenas,

people would lose a sense of standard.

In any case, most people currently have almost no sense of "historical coherence," so they won't be losing much.

People would diversify inWe're already grateful for the amazing fruits of specialization that we already enjoy. I see no reason not to embrace further specialization.

extremes, to the point of regarding those in other arenas of activity

(the musicians, the athletes, the scholars, the thinkers) almost as

separate species, literally a specialized breed, and be little able and

little interested in trying to relate to them. "Am I supposed to

applaud?" "Am I supposed to try to remember his name?"

Whatever sense of standard people did have, they would expect it to

dissolve quickly. So the breakdown in historical coherence would be in

relation to both the past and the future. Every generation would bring

drastic changes in standards, changes that were unforeseen and yet

unsurprising.

Again, this applies equally to rapid economic growth. Think about the breakdown of "historical coherence" between Maoist communes in 1960 and modern China. Good riddance.

I've used examples from sports, but I think the troubles pretty well

carry over to broader areas of life, including even wisdom and virtue. A

main point of Polanyi's book The Study of Man is that

reverence, that necessary instrument for perceiving greatness, is

especially applicable in the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. Those, too,

might have some genetic basis. But whereas we would still know which

ball players hit the most home runs, here we might have even greater

difficulty recognizing the standouts. And inasmuch as we did recognize

the standouts, or thought we did, we might regard them as we regard the

new home run champions: more as a specialized breed than as exemplars.

Would I ever have bothered to dwell in Michael Polanyi's thought if I

knew he were a designer baby?

The Dan Klein I know would focus on the quality of Polanyi's arguments, not his origin story. That's what we should all do.

Adam Smith held that all moral approval relates to a sympathy; the

sympathy ratifies or underwrites the approval. Suppose, on Smith's

authority, that the principle is sound. It would be just as sound in a

world of designer babies. But in such a world, the sympathies themselves

would be terribly attenuated, and hence also the moral approvals

underwritten. I think our moral confusion would grow more confused; I

suspect that the result would be moral and spiritual life that is

shallower, not deeper.

Dan, do you really think parents are going to select against genes for sympathy? That's very hard to believe. Kindness is one of the main things parents try to instill in their kids. If anything, we should expect designer babies to feel more sympathy, not less.

Now, here are some reasons why the two assumptions are not realisticPossibly, but I'm not worried. In Western societies, controlling reproductive choice is widely seen as totalitarian. Who today does not recoil in the face of the Supreme Court's notorious 1927 decision to allow mandatory sterilization? I am however worried that Western societies will deprive individuals of the right to use reproductive technology as they see fit, preemptively killing off an promising source of human progress.

(and why my apprehensions are greater still): If political disposition

in an individual has some genetic basis, then, just as governments got

involved in schooling, governments would likely get involved in

designing babies.

As for otherI can imagine designer babies would lead to marginally worse outcomes along these lines. But why on earth would you expect designer babies to "devastate" anything?

repercussions on liberty, consider these: (1) Designer babies would

devastate social coherence, connectedness, and personal meaning as

generated by voluntary, non-governmental affairs, and consequently, in

demanding them, people will look ever more to governmentalization;

Though to be honest, I hope Dan's right. In my view, existing levels of "social coherence" and "connectedness" are dangerously high, the cause of most of man's inhumanity to man. See Dan's great work on "the people's romance."

(2)The same goes for any high-cost novelty. Fortunately, the market usually outmaneuvers populist bellyaching long enough to turn novel luxuries into affordable conveniences.

If designing your baby is expensive, "the rich get richer" and "level

the playing field" will be louder than ever.

Liberalism brought rapid cultural change (see the first of the two trends I present in this 17-min video.)

I detect, especially in libertarians, a denial regarding the downside

of rapid change - and I mean a downside even apart from resultant

greater governmentalization.

But don't get me wrong about libertarians; they are not unique in

letting their ideological commitments distort their interpretations and

judgments.

Count me a libertarian "denier." Downsides notwithstanding, technological and economic progress are great. To even selectively rebut the massive presumption in favor of progress you need to point to something like Hiroshima in 1945, not intangible worries about historical coherence.

(24 COMMENTS)May 17, 2015

The Hours and Behavior Problems, by Bryan Caplan

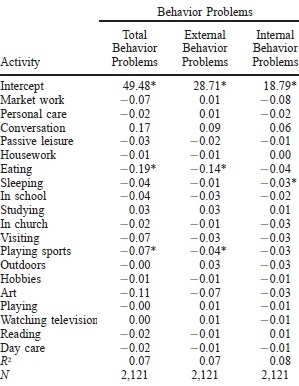

H&S have three measures of behavior problems. There's a measure of total problems, plus subscales for external problems (acting badly) and internal problems (feeling badly). Higher scores indicate more problems; SDs are 8 for total problems, 5.4 for external problems, and 3.2 for internal problems. Results continue to control for child's age, gender, race, ethnicity, head of household's education and

age, plus family structure, family employment, family income, and family

size.

Results for behavior problems are even scarcer than for academic achievement. None

of the nineteen kinds of time use predict behavior

problems across the board. Only two - eating and playing sports - have statistically significant effects on total problems. How big are the effects? Ten extra weekly hours of eating time cut problems by .24 SDs. Ten extra weekly hours of sports cut total problems by .09 SDs.

Look at all the stuff that doesn't matter: school time, study time, reading time, church time. Furthermore, contrary to pro-play psychologist Peter Gray, play time has near-zero effect on either external or internal behavior problems. Play may be intrinsically valuable for kids. I argue precisely this in The Case Against Education. But at least in this data set, the instrumental benefits of play are invisible.

While reverse causation remains a possibility, Hofferth and Sandberg do control for most of the obvious confounds. The large effect of eating time is at least consistent with preaching about the importance of shared family meals, though more plausibly long meals are a symptom of general family togetherness. Furthermore, even if we treat the effect of sports as entirely causal, it's still miniscule - especially compared to the triumphal rhetoric of our national cult of sport.

The chief takeaway, though, is that adults - not just parents but educators - need to relax. At least within the observed range, setting kids' daily agendas is almost fruitless. It's not helpful, it's not harmful, it's just bossy.

HT: Sandra Hofferth for giving me the mean and SD of the behavior subscales.

(5 COMMENTS)

May 14, 2015

3 Fun Quotes from Ayatollah Khomeini, by Bryan Caplan

[W]e do not repent, nor are we sorry for even a single moment for ourKhomeini on reactionary political thought:

performance during the war. Have we forgotten that we fought to fulfill

our religious duty and that the result is a marginal issue?

Yes, we are reactionaries, and you are enlightened intellectuals: You intellectuals do not want us to go back 1400 years. You, who want freedom,Khomeini on economics:

freedom for everything, the freedom of parties, you who want all the

freedoms, you intellectuals: freedom that will corrupt our youth,

freedom that will pave the way for the oppressor, freedom that will drag

our nation to the bottom.

Economics is for donkeys.All quotes from Khomeini's Wikipedia biography.

(9 COMMENTS)

May 13, 2015

Genetic Engineering Is Reproductive Freedom, by Bryan Caplan

I discuss the dystopian danger of genetic engineering in my chapter on "The Totalitarian Threat" in Global Catastrophic Risks :

Instead of searching for skeptical thoughts, aI pursue the utopian promise of genetic engineering in Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids :

totalitarian regime might use genetic testing to defend itself. Political orientation is already known to

have a significant genetic component. (Pinker 2002: 283-305) A "moderate" totalitarian regime

could exclude citizens with a genetic predisposition for critical thinking and

individualism from the party. A more

ambitious solution - and totalitarian regimes are nothing if not ambitious -

would be genetic engineering. The most

primitive version would be sterilization and murder of carriers of

"anti-party" genes, but you could get the same effect from selective

abortion. A technologically advanced

totalitarian regime could take over the whole process of reproduction, breeding

loyal citizens of the future in test tubes and raising them in state-run

"orphanages." This would not

have to go on for long before the odds of closet skeptics rising to the top of

their system and taking over would be extremely small.

Only one last obstacle stands between us and so-called "designer babies": figuring out which genes matter for each wish. Solid answers may be decades away, but human genetic engineering requires no more scientific breakthroughs--just persistence. The first customers will be wealthy eccentrics, but in a few decades, GE will be affordable and normal. Without strict government prohibition, I predict that our descendants will be amazingly smart, healthy, and accomplished.As usual, the wise way to avoid dystopia is to limit government, not technology:

Most people find my prediction frightening. Some paint GE as a pointless arms race; it's individually tempting, but society is better off without it. Others object that GE would increase inequality; the rich will buy alpha babies, and the rest of us will be stuck with betas. But there's something fishy about these complaints: If better nurture created a generation of wonder kids, we would rejoice. Suppose you naturally conceived an amazingly smart, healthy, and accomplished child. Would it bother you? If your neighbors had such a child, would you forbid your children to play with him? If your neighborhood were full of wonder kids, would you move away?

On my office wall, I have a picture of my dad at his high school graduation, towering a foot above his grandparents. Such height differences were common at the time because childhood nutrition improved so rapidly. I doubt that the grandparents who attended that graduation saw height as an "arms race" or griped that rich kids were even taller. They were happy to look up to their descendants -- and we'd feel the same way. Deep down, even technophobes want their descendants to surpass them. They just think that picking embryos is a vile way to make it happen.

Moderate defenders of genetic engineering often distinguish between good GE that prevents disease and disability and bad GE that increases intelligence, beauty, athletic ability, or determination. The theory is that good GE helps kids lead better lives, but bad GE merely panders to parents' vanity. The logic is hard to see. We praise parents who nurture their kids' health, intelligence, beauty, athletic ability, or determination because we know they're all good traits for kids to have.

Allowing parents to genetically engineer their children would lead to

healthier, smarter, and better-looking kids.

But the demand for other traits would be about as diverse as those of

the parents themselves. On the other

hand, genetic engineering in the hands of government is much more likely to be

used to root out individuality and dissent.

"Reproductive freedom" is a valuable slogan, capturing both

parents' right to use new technology if they want to, and government's duty not

to interfere with parents' decisions.Critics of genetic

engineering often argue that both

private and government use lie on a slippery slope. In one sense, they are correct. Once we allow parents to screen for genetic

defects, some will want to go further and screen for high IQ, and before you

know it, parents are ordering "designer babies." Similarly, once we allow government to

genetically screen out violent temperaments, it will be tempting to go further

and screen for conformity. The

difference between these slippery slopes, however, is where the slope

ends. If parents had complete control over their babies' genetic makeup, the

end result would be a healthier, smarter, better-looking version of the diverse

world of today. If governments had complete control over babies' genetic makeup, the

end result could easily be a population docile and conformist enough to make

totalitarianism stable.

The same goes, of course, for cloning.

(20 COMMENTS)Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers