Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 124

April 7, 2015

How Econ Melts Your Brain, by Bryan Caplan

Learning economics changes your life and improves your mind. As Dilbert creator Scott Adams insightfully observes, "When you have a working knowledge of economics, it's like having a mild super power." Yet when grading economics exams, I often notice a serious downside of studying economics: Many econ students literally get detached from reality.

I don't mean something lame like, "Some econ students disagree with me. How dare they?" What I mean is: I ask a question about the real world. The question even contains the phrase, "In the real world..." Then instead of discussing the real world, many economics students tell me about a model they learned in class. Sometimes their answers even contain the phrase, "Assume model X."

For example, an exam question might ask, "What determines the price of water when two individuals bump into each other in a remote desert?" Many economics students will then start talking about supply and demand, or even state, "Assume perfect competition. Then blah blah blah."

This wouldn't be so bad if the students would at least argue that, contrary to appearances, the perfectly competitive model applies. But when students take a model for granted despite the violation of its core assumptions - such as no individual has any noticeable effect on the market price - something has gone terribly wrong.

Learning how to logically analyze hypothetical social situations is a great skill. Economists should proudly teach it. But mastering this skill can and often does melt students' brains. Before studying economics, no one would imagine that you can discuss models in lieu of discussing the real world. After studying economics, I'm sorry to say, many students tacitly embrace this absurdity.

As economic educators, we bear a lot of the blame for the misconceptions our students acquire on our watch. How can we do better?

(32 COMMENTS)

I don't mean something lame like, "Some econ students disagree with me. How dare they?" What I mean is: I ask a question about the real world. The question even contains the phrase, "In the real world..." Then instead of discussing the real world, many economics students tell me about a model they learned in class. Sometimes their answers even contain the phrase, "Assume model X."

For example, an exam question might ask, "What determines the price of water when two individuals bump into each other in a remote desert?" Many economics students will then start talking about supply and demand, or even state, "Assume perfect competition. Then blah blah blah."

This wouldn't be so bad if the students would at least argue that, contrary to appearances, the perfectly competitive model applies. But when students take a model for granted despite the violation of its core assumptions - such as no individual has any noticeable effect on the market price - something has gone terribly wrong.

Learning how to logically analyze hypothetical social situations is a great skill. Economists should proudly teach it. But mastering this skill can and often does melt students' brains. Before studying economics, no one would imagine that you can discuss models in lieu of discussing the real world. After studying economics, I'm sorry to say, many students tacitly embrace this absurdity.

As economic educators, we bear a lot of the blame for the misconceptions our students acquire on our watch. How can we do better?

(32 COMMENTS)

Published on April 07, 2015 22:12

April 6, 2015

The Outsider Advantage, by Bryan Caplan

"Judean People's Front?! We're the People's Front of Judea!"

- The Life of Brian

"Ned, have you considered any of the other major religions? They're all pretty much the same."

-Reverend Lovejoy, The Simpsons

Intellectually speaking, how far apart are each of the following pairs?

1. Democrats and Republicans

2. Catholics and Protestants

3. Sunnis and Shiites

4. Trotskyists and Stalinists

My conditional prediction of your answers hinges on how you see yourself. For each pair, tell me if you strongly identify with either side. If you say yes, I predict you will think the difference between the two sides is vast. If you say no, I predict you will think the difference between the two sides is modest.

My reasoning: All of these pairs are, in the broad scheme of things, variations on a theme. Democrat and Republican are both variations on American nationalism. Catholic and Protestant are both variations on Christianity. Sunni and Shia are both variants on Islam. Trotskyist and Stalinist are both variations on Marxism-Leninism. All you need to see these truths is some intellectual distance. As long as you're an outsider, you're well-positioned for objectivity.

Insiders have a corresponding disadvantage. Their identity hangs in the balance: If the differences are minor, there's no good reason to strongly prefer one side over the other. And if there's no good reason to strongly prefer one side over the other, why have they in fact embraced one side as their own? Talk about cognitive dissonance.

As an insider, of course, it's tempting to rebuke outsiders for their ignorance. If they understood the issues, the outsiders would realize that the world really does hang in the balance. And in any case, if the differences are minor, why are their rivals attacking them so viciously?

The outsiders' answer, of course, is the cynical one: There's nothing to explain. Human beings passionately fight over trivia all the time. If Catholics and Protestants could fight the Thirty Years' War over religious minutiae, why is it so hard to believe that Democrats and Republicans are polluting Facebook to determine which variant on nationalism and social democracy is the One True Way? The problem, as usual, is that insiders are too emotionally invested in their group identity to see how trivial their differences really are.

(9 COMMENTS)

- The Life of Brian

"Ned, have you considered any of the other major religions? They're all pretty much the same."

-Reverend Lovejoy, The Simpsons

Intellectually speaking, how far apart are each of the following pairs?

1. Democrats and Republicans

2. Catholics and Protestants

3. Sunnis and Shiites

4. Trotskyists and Stalinists

My conditional prediction of your answers hinges on how you see yourself. For each pair, tell me if you strongly identify with either side. If you say yes, I predict you will think the difference between the two sides is vast. If you say no, I predict you will think the difference between the two sides is modest.

My reasoning: All of these pairs are, in the broad scheme of things, variations on a theme. Democrat and Republican are both variations on American nationalism. Catholic and Protestant are both variations on Christianity. Sunni and Shia are both variants on Islam. Trotskyist and Stalinist are both variations on Marxism-Leninism. All you need to see these truths is some intellectual distance. As long as you're an outsider, you're well-positioned for objectivity.

Insiders have a corresponding disadvantage. Their identity hangs in the balance: If the differences are minor, there's no good reason to strongly prefer one side over the other. And if there's no good reason to strongly prefer one side over the other, why have they in fact embraced one side as their own? Talk about cognitive dissonance.

As an insider, of course, it's tempting to rebuke outsiders for their ignorance. If they understood the issues, the outsiders would realize that the world really does hang in the balance. And in any case, if the differences are minor, why are their rivals attacking them so viciously?

The outsiders' answer, of course, is the cynical one: There's nothing to explain. Human beings passionately fight over trivia all the time. If Catholics and Protestants could fight the Thirty Years' War over religious minutiae, why is it so hard to believe that Democrats and Republicans are polluting Facebook to determine which variant on nationalism and social democracy is the One True Way? The problem, as usual, is that insiders are too emotionally invested in their group identity to see how trivial their differences really are.

(9 COMMENTS)

Published on April 06, 2015 22:06

April 2, 2015

Education and Libertarian Tendencies: An International Pattern, by Bryan Caplan

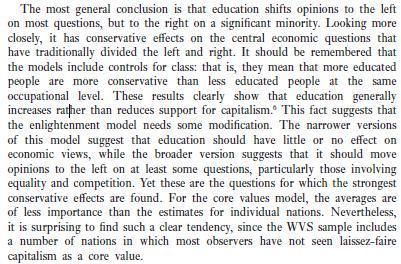

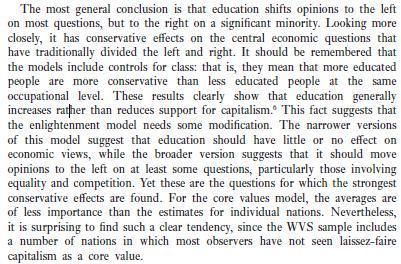

In the United States, the well-educated are more socially liberal and economically conservative. In absolute terms, they're statist, but they're nevertheless relatively libertarian. (See my notes for an intro, and Althaus for broader discussion).

Question: How does this pattern hold up internationally? Today I stumbled on interesting evidence from David Weakliem (2002. "The Effects of Education on Political Opinions." International Journal of Public Opinion Research). Punchline:

If academics around the world lean left, why on earth would education work this way? Peer effects are the obvious answer: Students pay a lot more attention to their fellow students than they do to the faculty. The longer you stay in school, the more time you spend around socially liberal, economically conservative peers - and the more you conform your views to theirs.

Why would social liberalism and economic conservatism appeal to the well-educated in the first place? My preferred answer is that (a) educated people are smarter, (b) smart people are somewhat more likely to notice the wonders of social liberalism and economic conservatism. But I'm open to other stories.

Before libertarians start celebrating education, however, they should ponder a serious unintended consequence. If well-educated people push each other in a libertarian direction, less-educated people presumably push each other in an authoritarian direction. As a result, randomly assigning one individual to either pool predictably changes his convictions. But moving everyone to the same pool wouldn't predictably change the average convictions of the pool.

P.S. Please don't apply my remarks to revisit the political externalities of immigration until you re-read this. And this.

(8 COMMENTS)

Question: How does this pattern hold up internationally? Today I stumbled on interesting evidence from David Weakliem (2002. "The Effects of Education on Political Opinions." International Journal of Public Opinion Research). Punchline:

If academics around the world lean left, why on earth would education work this way? Peer effects are the obvious answer: Students pay a lot more attention to their fellow students than they do to the faculty. The longer you stay in school, the more time you spend around socially liberal, economically conservative peers - and the more you conform your views to theirs.

Why would social liberalism and economic conservatism appeal to the well-educated in the first place? My preferred answer is that (a) educated people are smarter, (b) smart people are somewhat more likely to notice the wonders of social liberalism and economic conservatism. But I'm open to other stories.

Before libertarians start celebrating education, however, they should ponder a serious unintended consequence. If well-educated people push each other in a libertarian direction, less-educated people presumably push each other in an authoritarian direction. As a result, randomly assigning one individual to either pool predictably changes his convictions. But moving everyone to the same pool wouldn't predictably change the average convictions of the pool.

P.S. Please don't apply my remarks to revisit the political externalities of immigration until you re-read this. And this.

(8 COMMENTS)

Published on April 02, 2015 22:05

April 1, 2015

Are We Stuck With the Great Society?, by Bryan Caplan

A few months ago, Northwood University invited me to speak on, "Are we stuck with the Great Society?" This would probably sound like a strange topic to most Americans. To ask, "Are we stuck with Disneyland?," presupposes that Disneyland is bad. Similarly, to ask, "Are we stuck with the Great Society?," presupposes that the Great Society is bad.

Fortunately, I agree that the Great Society has been a terrible mistake, so it was an easy - and fun - talk to write. Most of the central arguments foreshadow what I'll be saying in Poverty: Who To Blame. For now, enjoy the slides.

(24 COMMENTS)

Fortunately, I agree that the Great Society has been a terrible mistake, so it was an easy - and fun - talk to write. Most of the central arguments foreshadow what I'll be saying in Poverty: Who To Blame. For now, enjoy the slides.

(24 COMMENTS)

Published on April 01, 2015 22:08

March 31, 2015

The Prevalence of Marxism in Academia, by Bryan Caplan

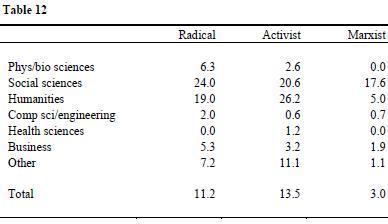

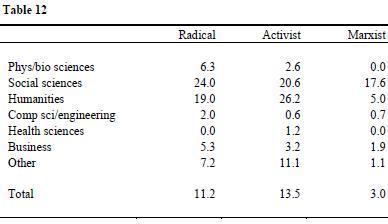

As the Iron Curtain crumbled, people often joked, "Marxism is dead everywhere - except American universities." The stereotype of the Marxist professor runs deep. But is this stereotype grounded in statistical fact? Here are the results from a 2006 nationally representative survey of American professors. The survey asked if the professor considered himself "radical," "political activist," or "Marxist." Survey says:

Overall, Marxism is a tiny minority faith. Just 3% of professors accept the label. The share rises to 5% in the humanities. The shocker, though, is that as recently as 2006, about 18% of social scientists self-identified as Marxists.

Neil Gross and Solon Simmons, the authors of the study, hasten to say, "Move along, nothing to see here."

I suspect that Marxists' share has fallen since 2006. But it makes me wonder: When precisely did American academia hit "peak Marxism" - and how high was the peak?

(35 COMMENTS)

Overall, Marxism is a tiny minority faith. Just 3% of professors accept the label. The share rises to 5% in the humanities. The shocker, though, is that as recently as 2006, about 18% of social scientists self-identified as Marxists.

Neil Gross and Solon Simmons, the authors of the study, hasten to say, "Move along, nothing to see here."

[S]elf-identified Marxists are rare in academe today. The highest proportion of Marxist academics can be found in the social sciences, and there they represent less than 18 percent of all professors (among the social science fields for which we can issue discipline-specific estimates, sociology contains the most Marxists, at 25.5 percent).In contrast, I urge you to rubberneck. If 18% of biologists believed in creationism, that would be a big deal. Why? Because creationism is nonsense. Similarly, if 18% of social scientists believe in Marxism, that too is a big deal. Why? Because Marxism is nonsense. Furthermore, if 18% of a discipline fully embrace a body of nonsense, there is also probably a large bloc of nonsense sympathizers - people who won't swallow the nonsense whole, but nevertheless see great value in it. Suppose, plausibly, that there is one fellow traveler for every true believer. That would bring the share of abject intellectual corruption to fully 35% - and 51% in sociology.

I suspect that Marxists' share has fallen since 2006. But it makes me wonder: When precisely did American academia hit "peak Marxism" - and how high was the peak?

(35 COMMENTS)

Published on March 31, 2015 07:39

March 29, 2015

How to Fix Seminars, by Bryan Caplan

I'm sick of academic seminars. Even if the presenter has a good paper and speaks well, the audience ruins things. How? Two minutes into any talk, the fruitless interruptions begin. Half the time, they're premature quality control: "Are you going to deal with ability bias?" "Uh, yes. On the next slide." The other half the time, they're bizarre pet peeves. "How does this relate to sequential equilibrium?" "Uh, it doesn't. It's an empirical paper." "Yes, but that reminds me of something Rudi Dornbusch once said. Now I'm going to talk for four minutes."

Once fruitless interruptions begin, there's no such thing as winning. There are only different degrees of losing. Even if you limit each question to a single minute of time, your ideas lose their flow. A well-planned talk handles complexities in logical order, allowing relative novices to follow your reasoning. Premature quality control smashes that order to pieces, leaving novices confused and experts bored. And after three pet peeve questions, the audience struggles to remember the topic of the talk - never mind its thesis.

Can't speakers deflect the pointless interruptions to make the talk train run on time? It's tough. You can't just say, "Please, only good questions." And once you take one silly question, every other squeaky wheel feels entitled to put in his two cents. "Hey, my question's clearly better than the last guy's!" As a speaker, then, you have to choose between offending a fifth of the audience or boring the entirety. Professionally speaking, the former is the greater danger.

Still, I come to fix seminars, not to abolish them. My colleague Dan Klein inspired the following alternate rules:

1. Split the talk into two parts. Part 1 is the first two-thirds of the allotted time. Part 2 is the last third of the allotted time.

2. During Part 1, the audience may not ask any questions. No exceptions.

3. However, the speaker retains the option to ask the audience questions during Part 1. If the speaker sees a lot of confused faces, he can query, "Are you familiar with the efficiency case for Pigovian taxation?" and adjust his presentation accordingly.

4. The speaker scrupulously ends Part 1 on time, then turns the rest of the talk over for questions.

Step 4 has two main advantages over the standard method.

First, it's easier for the speaker to filter out bad questions. Since there is a dedicated question period, multiple people will normally raise their hands. If an audience member asks bad questions, the speaker can call on other people first. If an audience member asks too many questions, the speaker can gently say, "Someone who hasn't already asked a question..."

Second, the question pool will generally be better. Once the audience understands your point, they can ask questions about the overall thesis rather than Slide 3. Quality control questions now serve their legitimate function: If you missed your opportunity to address a tricky point during Part 1, audience members can correct your oversight in Part 2. The pet peeves still make a spectacle of themselves, but at least the audience walks away knowing your thesis.

A few months ago, I saw Dan Klein use a similar format, though he made Part 1 shorter and Part 2 longer. This Wednesday, I tried it at the Public Choice Seminar. It could easily have been the best academic seminar I've ever done. The approach makes so much sense, it makes me wonder if the standard approach is ever better.

My best guess: The standard approach might be better for graduate students. Suppose you're a public speaking novice. Interruptions are an opportunity to improve your performance in real time. Toastmasters clubs, for example, appoint an "Ah-Counter" to clap whenever the speaker says "ah" or "um." Alternately, suppose you know less about your topic than several experts in the audience. Their interruptions are an opportunity to prevent you from derailing your own talk with errors and irrelevancies. The background assumption here, though, is that the speaker and the audience both constructively treat the seminar as training. Shredding graduate students helps no one.

Comments on my seminar system are good, but field experiments are better. Have I piqued your interest? Try my approach and tell me how it works.

(24 COMMENTS)

Once fruitless interruptions begin, there's no such thing as winning. There are only different degrees of losing. Even if you limit each question to a single minute of time, your ideas lose their flow. A well-planned talk handles complexities in logical order, allowing relative novices to follow your reasoning. Premature quality control smashes that order to pieces, leaving novices confused and experts bored. And after three pet peeve questions, the audience struggles to remember the topic of the talk - never mind its thesis.

Can't speakers deflect the pointless interruptions to make the talk train run on time? It's tough. You can't just say, "Please, only good questions." And once you take one silly question, every other squeaky wheel feels entitled to put in his two cents. "Hey, my question's clearly better than the last guy's!" As a speaker, then, you have to choose between offending a fifth of the audience or boring the entirety. Professionally speaking, the former is the greater danger.

Still, I come to fix seminars, not to abolish them. My colleague Dan Klein inspired the following alternate rules:

1. Split the talk into two parts. Part 1 is the first two-thirds of the allotted time. Part 2 is the last third of the allotted time.

2. During Part 1, the audience may not ask any questions. No exceptions.

3. However, the speaker retains the option to ask the audience questions during Part 1. If the speaker sees a lot of confused faces, he can query, "Are you familiar with the efficiency case for Pigovian taxation?" and adjust his presentation accordingly.

4. The speaker scrupulously ends Part 1 on time, then turns the rest of the talk over for questions.

Step 4 has two main advantages over the standard method.

First, it's easier for the speaker to filter out bad questions. Since there is a dedicated question period, multiple people will normally raise their hands. If an audience member asks bad questions, the speaker can call on other people first. If an audience member asks too many questions, the speaker can gently say, "Someone who hasn't already asked a question..."

Second, the question pool will generally be better. Once the audience understands your point, they can ask questions about the overall thesis rather than Slide 3. Quality control questions now serve their legitimate function: If you missed your opportunity to address a tricky point during Part 1, audience members can correct your oversight in Part 2. The pet peeves still make a spectacle of themselves, but at least the audience walks away knowing your thesis.

A few months ago, I saw Dan Klein use a similar format, though he made Part 1 shorter and Part 2 longer. This Wednesday, I tried it at the Public Choice Seminar. It could easily have been the best academic seminar I've ever done. The approach makes so much sense, it makes me wonder if the standard approach is ever better.

My best guess: The standard approach might be better for graduate students. Suppose you're a public speaking novice. Interruptions are an opportunity to improve your performance in real time. Toastmasters clubs, for example, appoint an "Ah-Counter" to clap whenever the speaker says "ah" or "um." Alternately, suppose you know less about your topic than several experts in the audience. Their interruptions are an opportunity to prevent you from derailing your own talk with errors and irrelevancies. The background assumption here, though, is that the speaker and the audience both constructively treat the seminar as training. Shredding graduate students helps no one.

Comments on my seminar system are good, but field experiments are better. Have I piqued your interest? Try my approach and tell me how it works.

(24 COMMENTS)

Published on March 29, 2015 22:08

March 25, 2015

Plug-and-Play People, by Bryan Caplan

One common complaint about proponents of open borders is that we picture human beings as interchangeable parts. If an American can do X, so can a Haitian. Why can't the open borders crowd see the obvious truth that people are not "plug-and-play" - that you can't jumble different kinds of people and expect them to function well together?

My instinctive reaction is to appeal to Econ 1 and basic facts.

The Econ 1: If people of different nationalities worked poorly together, employers would account for this fact in their hiring decisions. An employer with a 100% native-born American workforce would look at immigrant applicants and silently note, "Oil and water don't mix." Or perhaps he'd think, "Americans and high-caste Indians work well together, but Americans and Indian untouchables don't." Then he'd hire on the basis of these ugly truths, while paying lip service to equal opportunity and the brotherhood of man. As a result, immigrants - or at least the "wrong kind of immigrants" - would discover that migrating for better jobs is a waste of time. Jobs are better in the First World, but you have to be First-World-compatible to land one.

The basic facts: This manifestly is not how labor markets work. As the opponents of immigration loudly complain, First World employers hire immigrants all the time. They eagerly hire legal immigrants - and as long as the law is laxly enforced, they furtively hire illegal immigrants. Even when the law criminalizes non-discrimination, plenty of First World employers look over their shoulders, shrug, mutter "Money's money" and break the law. Doesn't this show that workers ultimately are plug-and-play?

Yet on reflection, my instinctive reaction misses much of the magic of the market. If you've ever been a boss, you know that getting human beings of the same culture to effectively cooperate together is like pulling teeth. Indeed, it's like pulling shark teeth that never stop growing back. The more different the members of your team are, the greater the miscommunication and strife.

How then do firms manage to function? The social intelligence of the leadership. Good managers know in their bones that diverse human beings aren't built for close cooperation. Rather than throw their hands up in despair, however, good managers rise to the challenge. True to their job description, managers manage their workers, forging them into effective teams despite their disparate abilities, personalities, and backgrounds. It's an uphill battle, and you have to keep running just to stay in place. But good managers kindle the fire of teamwork, then keep the fire burning day in, day out.

The critics of immigration are right to insist that people aren't plug-and-play. Cultural diversity definitely makes teamwork harder. Unlike the critics of immigration, however, businesses around the world treat this fact not as a plague, but a profit opportunity. Sure, some stodgy entrepreneurs mutter defeatist cliches about oil and water and keep hiring within their tribes. But more visionary entrepreneurs rise to the challenge of diversity every day. That's why even the most unskilled and culturally alien workers rightly believe that the streets of the First World are paved with gold. Given half a chance, socially adept businesspeople rush to do the paving.

But isn't the workplace a relatively favorable environment for diversity? No; the opposite is true. Stores gladly open their doors to the general public because almost any human being with money to spend is a lovely customer. As long as the customers don't bite each other, the more the merrier. Landlords are a little more selective, but not much: If your credit's good and you keep the noise down to a dull roar, they'll rent to you.

Employers, in contrast, hire with trepidation. They know that co-workers need to cooperate like the fingers of a hand. One bad worker makes a whole firm look bad. One bad worker can ruin a whole day's work. One bad worker can make ten good workers quit in frustration. Outside of the army, no voluntary endeavor in modern adult life is more regimented than the workplace. Yet by the power of social intelligence, business managers make diversity run smoothly, laughing all the way to the bank.

Where does politics fit in? It's a lingering concern, but vastly overrated. Most immigrants are even more politically apathetic than natives. They vote at sharply lower rates. And when they arrive in a vast new land, most of their old grievances become irrelevant overnight: Once they arrive in the U.S., Serbs and Croats, Hutus and Tutsis, even Israelis and Palestinians let bygones be bygones. Political plug-and-play is unnecessary because few immigrants want to play politics in the first place.

(27 COMMENTS)

My instinctive reaction is to appeal to Econ 1 and basic facts.

The Econ 1: If people of different nationalities worked poorly together, employers would account for this fact in their hiring decisions. An employer with a 100% native-born American workforce would look at immigrant applicants and silently note, "Oil and water don't mix." Or perhaps he'd think, "Americans and high-caste Indians work well together, but Americans and Indian untouchables don't." Then he'd hire on the basis of these ugly truths, while paying lip service to equal opportunity and the brotherhood of man. As a result, immigrants - or at least the "wrong kind of immigrants" - would discover that migrating for better jobs is a waste of time. Jobs are better in the First World, but you have to be First-World-compatible to land one.

The basic facts: This manifestly is not how labor markets work. As the opponents of immigration loudly complain, First World employers hire immigrants all the time. They eagerly hire legal immigrants - and as long as the law is laxly enforced, they furtively hire illegal immigrants. Even when the law criminalizes non-discrimination, plenty of First World employers look over their shoulders, shrug, mutter "Money's money" and break the law. Doesn't this show that workers ultimately are plug-and-play?

Yet on reflection, my instinctive reaction misses much of the magic of the market. If you've ever been a boss, you know that getting human beings of the same culture to effectively cooperate together is like pulling teeth. Indeed, it's like pulling shark teeth that never stop growing back. The more different the members of your team are, the greater the miscommunication and strife.

How then do firms manage to function? The social intelligence of the leadership. Good managers know in their bones that diverse human beings aren't built for close cooperation. Rather than throw their hands up in despair, however, good managers rise to the challenge. True to their job description, managers manage their workers, forging them into effective teams despite their disparate abilities, personalities, and backgrounds. It's an uphill battle, and you have to keep running just to stay in place. But good managers kindle the fire of teamwork, then keep the fire burning day in, day out.

The critics of immigration are right to insist that people aren't plug-and-play. Cultural diversity definitely makes teamwork harder. Unlike the critics of immigration, however, businesses around the world treat this fact not as a plague, but a profit opportunity. Sure, some stodgy entrepreneurs mutter defeatist cliches about oil and water and keep hiring within their tribes. But more visionary entrepreneurs rise to the challenge of diversity every day. That's why even the most unskilled and culturally alien workers rightly believe that the streets of the First World are paved with gold. Given half a chance, socially adept businesspeople rush to do the paving.

But isn't the workplace a relatively favorable environment for diversity? No; the opposite is true. Stores gladly open their doors to the general public because almost any human being with money to spend is a lovely customer. As long as the customers don't bite each other, the more the merrier. Landlords are a little more selective, but not much: If your credit's good and you keep the noise down to a dull roar, they'll rent to you.

Employers, in contrast, hire with trepidation. They know that co-workers need to cooperate like the fingers of a hand. One bad worker makes a whole firm look bad. One bad worker can ruin a whole day's work. One bad worker can make ten good workers quit in frustration. Outside of the army, no voluntary endeavor in modern adult life is more regimented than the workplace. Yet by the power of social intelligence, business managers make diversity run smoothly, laughing all the way to the bank.

Where does politics fit in? It's a lingering concern, but vastly overrated. Most immigrants are even more politically apathetic than natives. They vote at sharply lower rates. And when they arrive in a vast new land, most of their old grievances become irrelevant overnight: Once they arrive in the U.S., Serbs and Croats, Hutus and Tutsis, even Israelis and Palestinians let bygones be bygones. Political plug-and-play is unnecessary because few immigrants want to play politics in the first place.

(27 COMMENTS)

Published on March 25, 2015 22:02

March 24, 2015

When Orwell Met Aumann, by Bryan Caplan

Cowen and Hanson's "Are Disagreements Honest?" summarizes the theoretical case against "agreeing to disagree."

(6 COMMENTS)

Yet according to well-known theory, such honest disagreement is impossible. Robert Aumann (1976) first developed general results about the irrationality of "agreeing to disagree." He showed that if two or more Bayesians would believe the same thing given the same information (i.e., have "common priors"), and if they are mutually aware of each other's opinions (i.e., have "common knowledge"), then those individuals cannot knowingly disagree. Merely knowing someone else's opinion provides a powerful summary of everything that person knows, powerful enough to eliminate any differences of opinion due to differing information.It's hard to find real human beings who reason this way. What about fictional characters? One suddenly came to mind tonight: Winston Smith from George Orwell's 1984 . Smith is admirably meta-rational while brilliant Thought Policeman O'Brien intellectually bullies him.

Aumann's impossibility result required many strong assumptions, and so it seemed to have little empirical relevance. But further research has found that similar results hold when many of Aumann's assumptions are relaxed to be more empirically relevant. His results are robust because they are based on the simple idea that when seeking to estimate the truth, you should realize you might be wrong; others may well know things that you do not.

O'Brien was a being in all ways larger than himself. There was noAs far as I understand, Aumann's theorem only applies if both Smith and O'Brien are meta-rational. Otherwise, Smith is epistemically selling himself short. And the very fact that O'Brien combines intellectual argument with physical torture conveys extra negative information about O'Brien's credibility. What's striking, though, isn't that Smith takes Aumannian reasoning too far, but that he applies this reasoning in the first place.

idea that he had ever had, or could have, that O'Brien had not long ago

known, examined, and rejected. His mind CONTAINED Winston's mind. But

in that case how could it be true that O'Brien was mad? It must be he,

Winston, who was mad.

(6 COMMENTS)

Published on March 24, 2015 22:13

March 23, 2015

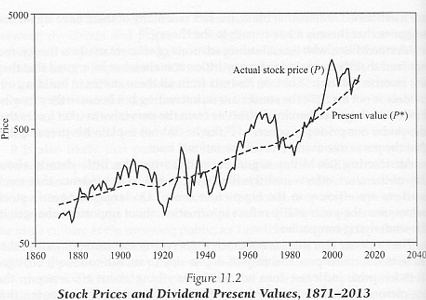

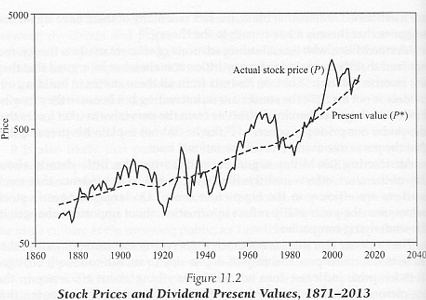

The Most Convincing Figure in Irrational Exuberance, by Bryan Caplan

I never got around to reading the previous editions of Robert Shiller's Irrational Exurberance, but I've finished reading the new third edition cover-to-cover.

Rather than review the whole book, consider the single most convincing figure. At first glance, it's easy to miss the point.

Shiller begins with an obvious observation: "The dividend value is extremely steady and trend-like, partly because the calculations for present value use data over a range far into the future and partly because dividends have not moved very dramatically."

So what? Here's what:

Now ask yourself: In Shiller's figure, which line is analogous to actual temperature? Actual present values of dividends, of course. Then which line is analogous to predicted temperature? Observed stock prices - the market's best guess of the present value of dividends. Yet contrary to the basic logic of forecasting, the latter is jumpy even though the former is steady.

This is a classic case of, "If you're not confused, you don't understand what's going on." Shiller's attempts to resolve these puzzles leave me dissatisfied, but kudos to him for opening my eyes to the enormity of the oddity.

(12 COMMENTS)

Rather than review the whole book, consider the single most convincing figure. At first glance, it's easy to miss the point.

Shiller begins with an obvious observation: "The dividend value is extremely steady and trend-like, partly because the calculations for present value use data over a range far into the future and partly because dividends have not moved very dramatically."

So what? Here's what:

[S]tock prices appear too volatile to be considered in accord with efficient markets. Assuming that stock prices are supposed to be an optimal predictor of the dividend present value, then they should not jump around erratically if the true fundamental value is growing along a smooth trend.The next three sentences are truly profound:

Only if the public could predict the future perfectly should the price be as volatile as the present value, and in that case it should match up perfectly with the present value. If the public cannot predict well, then the forecast should move around a lot less than the present value. But that's not what we see in Figure 11.2. [emphasis mine]By analogy, suppose you graphed actual temperature against predicted temperature. Which should be more volatile? Actual temperature, of course. Predicted temperature should be heavily based on long-run average temperatures, which don't jump around much. (Indeed, if you look more than ten days into the future, weather sites often just report historic means, putting zero weight on current weather). Actual temperatures, however, are routinely surprising.

Now ask yourself: In Shiller's figure, which line is analogous to actual temperature? Actual present values of dividends, of course. Then which line is analogous to predicted temperature? Observed stock prices - the market's best guess of the present value of dividends. Yet contrary to the basic logic of forecasting, the latter is jumpy even though the former is steady.

This is a classic case of, "If you're not confused, you don't understand what's going on." Shiller's attempts to resolve these puzzles leave me dissatisfied, but kudos to him for opening my eyes to the enormity of the oddity.

(12 COMMENTS)

Published on March 23, 2015 22:06

March 22, 2015

Perfect Pedagogy, by Bryan Caplan

When you were taught about perfect competition, what was the underlying interpretation of the model?

1. The model is a good approximation: Markets in the real world work about as well - and in roughly the same way - as the perfectly competitive model says. Regulation is therefore generally counter-productive.

2. The model is a foil: Markets only work well if the model's numerous extreme assumptions hold, so markets in the real world are at best so-so. Regulation is therefore generally beneficial, or even necessary.

3. The model is a special case: Markets work well when its assumptions hold, but the various forms of "imperfect" competition work well when the perfectly competitive assumptions are violated. Regulation - including regulation to make actual markets better match the perfectly competitive assumptions - is therefore generally counter-productive.

Take lectures, assigned readings, and homework into account when you answer. Please state the best of these three response options in the first sentence of your comment before elaborating or proposing alternative interpretations.

Bonus: If you've ever taught the perfectly competitive model, what underlying interpretation did you convey to your students?

(28 COMMENTS)

1. The model is a good approximation: Markets in the real world work about as well - and in roughly the same way - as the perfectly competitive model says. Regulation is therefore generally counter-productive.

2. The model is a foil: Markets only work well if the model's numerous extreme assumptions hold, so markets in the real world are at best so-so. Regulation is therefore generally beneficial, or even necessary.

3. The model is a special case: Markets work well when its assumptions hold, but the various forms of "imperfect" competition work well when the perfectly competitive assumptions are violated. Regulation - including regulation to make actual markets better match the perfectly competitive assumptions - is therefore generally counter-productive.

Take lectures, assigned readings, and homework into account when you answer. Please state the best of these three response options in the first sentence of your comment before elaborating or proposing alternative interpretations.

Bonus: If you've ever taught the perfectly competitive model, what underlying interpretation did you convey to your students?

(28 COMMENTS)

Published on March 22, 2015 22:02

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers

Bryan Caplan isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.