Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 123

April 27, 2015

Educational Signaling: A Fad Whose Time Has Come, by Bryan Caplan

Talk to economists, and you'll find a large number who believe thatIt does indeed "make sense." And according to the only survey of which I know, economists in general are at least open-minded about educational signaling. But Noah strangely neglects to mention that empirical labor economists in general, and education economists in particular, rarely engage the signaling model. Human capital purism really is their dominant paradigm - and they studiously ignore the "when

college -- that defining institution of America's privileged youth -- is

mostly signaling. It makes sense, after all -- don't most people go to

college because they think it will get them a job? And honestly, when

was the last time you actually used any of the things you learned in

college at your job?

was the last time you actually used any of the things you learned in

college at your job?" argument.

Possibly the biggest promoter of the signaling theory of education is George Mason University's Bryan Caplan. Caplan believes so passionately in the model that he's writing

a book about it, called "The Case Against Education." He has already

written enough blog posts on the topic to make a small book!

Caplan's message is bound to appeal to people who dislike the

institution of college, whether because they think it's too politically

leftist, or they're worried about high tuition and student loans.

There's something to this. It's worth pointing out, though, that many defenders and fellow travelers of the signaling model are left-leaning sociologists.

But

there are some big holes in the case. Caplan's GMU colleague, Tyler

Cowen, is rightfully skeptical of claims that college is mostly signaling. Let me add my voice to the skeptical chorus.

First, intelligence isn't that hard to spot. Performance on any

mental task -- a standardized test or even a high school chemistry class

-- will give an employer an immediate general idea of ability. No need

to waste four of your prime years on a signal that can be generated in

two hours.

I've said this. I've also criticized the many economists who think Supreme Court rulings on intelligence testing are a major cause of the rising educational premium.

So is college a way to signal conscientiousness and willingness to

work? Maybe. But an even better way to signal that would be to actually work at a job

for four years. One would think that if young people needed to do some

hard work to signal their work ethics, some companies would spring up

that gave young people real productive work to do, and provided evidence

of their performance. Instead of paying through the nose to send a

signal of your industriousness, you could get paid. But we don't see

this happening.

Like most economists, Noah needs to be more sociological. In a cultural vacuum, working four years might be a great signal of work ethic. But no human being lives in a cultural vacuum. We live in societies thick with norms and expectations. And in our society, people with strong work ethics go to college and people with bad work ethics don't.

Disagree? Just picture how your parents would react if you told them, "I'm not going to college. I'm just going to get a job." In our society, your parents definitely wouldn't respond, "That makes sense, because you're such a hard worker." Why not? Because in our society, most hard-workers choose college. If a hard-working kid refuses to copy their behavior, people - including employers - understandably treat him as if he's lazy. Because lazy is how he looks.

Noah overlooks another key trait that education signals: sheer conformity to social norms. In our society, you're supposed to go to college, and you're supposed to finish. If you don't, the labor market sensibly questions your willingness to be a submissive worker bee.

When you think about it this way, the whole idea of

college-as-signaling becomes a little absurd. People's careers last for

35 to 45 years. But after you've been working for a while, prospective

employers can look at your work history -- they don't need the college

signal anymore. Caplan's theory therefore is that many young people are

spending four years -- and lots of tuition money -- on something that

will only affect the very beginning of a career.

As I've explained before, getting your foot in the door may seem like a small step, but it's invaluable nonetheless. Without the right degrees, it's extremely hard to even start building an impressive work history for employers to judge. Furthermore, if Noah were properly sociological, he'd know that employers are quite slow to fire employees whose formal credentials overstate their job performance - and even slower to publicize their negative evaluations to the broader labor market. Economists may balk at the idea that a mere credential can durably raise your earnings, but everyone long saddled with incompetent co-workers says otherwise.

There are many other reasons to doubt the signaling theory of

college. A more likely explanation for college's enduring importance is

that it provides a large number of benefits that are very hard to

measure -- building social networks, broadening people's perspective,

giving young people practice learning difficult new mental tasks and so

forth.

I'm glad to hear this. Noah inadvertently grants one of my key points: Most of education's labor market payoff is unrelated to the material your professors explicitly teach you. Once you accept this heresy, you're stuck with some combination of my multidimensional signaling story, and Noah's amorphous, evasive "large number of benefits that are very hard to measure" story. If that's the choice, my story will end up with the lions' share of the mix. Noah is welcome to the leftovers.

Final challenge for Noah: If education's rewards stem from this "large number of benefits that are very hard to measure," why on earth would the payoff for graduation vastly exceed the payoff for a typical year of education? My explanation, of course, is that given the vast social pressure to cross educational milestones, failure to graduate sends a very negative signal to the labor market, leading to discontinuous rewards. What's Noah's alternative? Do schools really delay "building social networks, broadening people's perspective,

giving young people practice learning difficult new mental tasks and so

forth" to senior year?

April 25, 2015

Mankiw on Free Trade in the NYT, by Bryan Caplan

(13 COMMENTS)

April 23, 2015

The Mellow Heuristic, by Bryan Caplan

I know a lot about the science of gender, so the crowd's poor behavior has little effect on my views. But I must confess: If I knew less, this would be a perfect time to apply what I call the Mellow Heuristic. The Mellow Heuristic is a rule of thumb for adjudicating intellectual disputes when directly relevant information is scarce. The rule has two steps.The entrance to the classroom where Sommers spoke was surrounded by flyers accusing her of supporting rapists. "F*** anti-feminists," read one sign.

The students responsible for the safe space were more polite,

although they did joke about biting people they disagreed with and

promised to zealously guard their precious space from "toxic, dangerous,

and/or violent" people--anyone who didn't share their perspective, in

other words. (Video of that here, courtesy of Nick Mascari, Third Base Politics).

Sommers told Reason that the most bizarre form of protest was the students who sat in the front row during her talk with their mouths taped shut.

"They just stared," she said.

Others did more than stare; they interrupted and booed whenever

Sommers said something that irked them. At one point, a philosophy

professor in the audience stood up and called for civility. They mocked

him and yelled at him to sit down, according to Sommers.

Step 1: Look at how emotional each side is.

Step 2: Assume the less emotional side is right and the more emotional side is wrong.

Why should we believe the Mellow Heuristic tracks truth? Most obviously, because emotionality drowns out clear thinking, and clear thinking tends to lead to truth. The more emotional people are, the less clear thinking they do, so the less likely they are to be right.

Furthermore, people who hope to persuade others normally highlight their strongest evidence. So if advocates of a view spend most of their time emoting on you, it is reasonable to infer that they lack better evidence. And sides with low-quality evidence are also less likely to be right.

Like all heuristics, the Mellow Heuristic is imperfect. If Hannibal Lecter debated one of his traumatized victims, the Mellow Heuristic would probably conclude that Lecter was in the right. But it's a good heuristic nonetheless. On average, the calm are really are more reliable than the agitated.

On some level, you already know this. That's why you tell yourself, "Calm down" when the costs of error are high. If you don't trust yourself to reach the truth when you're upset, why would you trust strangers who aren't even trying to keep their emotions in check?

(17 COMMENTS)

Thank You for Correcting Me, Matthew Baker, by Bryan Caplan

Still, all the files have been updated, and I'm immensely grateful to Mr. Baker for being so meticulous. I'll certainly be thanking him in the book credits when the project's done.

(0 COMMENTS)

April 22, 2015

Education and Apostasy, by Bryan Caplan

Sociologists of religion have long linked educational attainment to religious decline (Caplovitz and Sherrow 1977; Hadaway and Roof 1988; Hunter 1983; Sherkat 1998). But the assumption that a college education is the reason for religious decline gathers little support here. Emerging adults who do not attend college are most prone to curb all three types of religiousness in early adulthood.Simply put, higher education is not the enemy of religiosity that so many have made it out to be. So if a college education is not the secularizing force we presumed it to be, what is going on?"What is not contested, then, cannot be lost." True enough.

Certainly many college students participate less in formal religious activities than they did as adolescents, but church attendance may take a hit simply because of factors that influence the lives of all emerging adults: the late-night orientation of young adult life; organized religion's emphasis on other age groups, namely school-aged youth and parents; and collective norms about appearing "too religious." (Smith and Denton 2005)

The overwhelming majority (82 percent) of college students maintain at least a static level of personal religiosity in early adulthood. Similarly, 86 percent retain their religious affiliation. For most, it seems religious belief systems go largely untouched for the duration of their education. Religious faith is rarely seen as something that could either influence or be influenced by the educational process. This is true for several reasons. First, some students have elected not to engage in the intellectual life around them. They are on campus to pursue an "applicable" degree, among other, more mundane pursuits, and not to wrestle with issues of morality or meaning. They instead stick to what they "need to know" -- that which will be on the exam. Such students are numerous, and as a result students' own religious faith (or lack of it) faces little challenge. Indeed, many university curricula are constructed to reward this type of intellectual disengagement... What is not contested, then, cannot be lost. Faith simply remains in the background of students' lives as a part of who they are, but not a part they talk about much with their peers or professors.

Second, while higher education opens up new worlds for students who apply themselves, it can, but does not often, create skepticism about old (religious) worlds, or at least not among most American young people, in part because students themselves do not perceive a great deal of competition between higher education and faith, and also because very many young Americans are so undersocialized in their religious faith (before college begins) that they would have difficulty recognizing faith-challenging material when it appears. And even if they were to perceive a challenge, many young people do not consider religion something worth arguing over.

On the other hand are devoutly religious college students. They arrive on campus expecting challenges and hostility to their religious perspectives. When they do not get it, they are pleasantly surprised; when they do, it merely meets their expectations and fits within their expected narrative about college life. Campus religious organizations anticipate such intellectual challenge and often provide a forum for like-minded students. In fact, college campuses are often less hostile to organized religious expression and its retention than are other contexts encountered by emerging adults, such as their workplaces. Campus religious organizations provide additional religious community to which non-students lack access. Furthermore, the arrival of postmodern, post-positivist thought on university campuses has served to legitimize religiosity and spirituality, even in intellectual circles. Together with heightened emphasis on religious tolerance and emerging emphases on spiritual development, antireligious hostility on campus may even be at a decades-long low.

(9 COMMENTS)

April 21, 2015

Where Are the Pro-Life Utilitarians?, by Bryan Caplan

This is deeply puzzling. While I'm not a utilitarian, the utilitarian case against abortion seems very strong. Consider: Even if a pregnant woman deeply resents her pregnancy, she is only pregnant for nine months. How could this outweigh the lifetime's worth of utility the unwanted child gets to enjoy if he's carried to term?

A bundle of empirical regularities reinforce this prima facie case.

1. Almost everyone is glad to be alive. The unwanted infant may have a below-average quality of life, but below-average is usually excellent nonetheless.

2. There is a long waiting list - hence excess demand - to adopt healthy infants, so birth mothers need not raise their unwanted children.

3. Due to the endowment effect, unwanted children often become wanted by their birth mother once they're born - as many would-be adoptive parents discover to their sorrow.

4. Women who just miss the legal cutoff for abortion seem to quickly recover emotionally. Pregnant women who think "A baby will ruin my life" are, on average, factually mistaken.

How could a utilitarian avoid the pro-life conclusion? There are two tempting routes:

1. Argue that the utility of the unborn counts for nothing - at least until the fetus starts feeling pleasure and pain. Convenient. But once you accept the core utilitarian intuition - that the existence of pleasure is good, and the existence of pain is bad - the creation of creatures who will feel a lot more pleasure than pain seems like a great good. Picture an uninhabited world capable of supporting happy lives. How could a utilitarian not want to populate it?

2. Argue that each unwanted child has large negative social effects, even though people are eager to adopt. Most obviously, utilitarians could embrace an extreme Malthusian story where the birth of one human statistically dooms another. Once you accept this story, of course, saving any life becomes morally suspect.

When I present the utilitarian case against abortion, people normally reply, "But that implies a further moral duty to have tons of babies." They're right. From my perspective, that's yet another convincing argument against utilitarianism. Creating life is a prime example of what utilitarians conceptually reject: actions that are morally good but not morally obligatory. But given utilitarians' notorious willingness to bite bullets, why should they demur here?

P.S. If you do know of any pro-life utilitarians, please share URLs in the comments.

(45 COMMENTS)

April 20, 2015

Are Centers a Mistake?, by Bryan Caplan

1. Give ALL the money to one school to create a Center for the Study of X - an academic cluster where all ten pro-X professors work together.

2. Give EACH school enough money to hire ONE professor, so every university has a lone proponent of X.

Question: Which option will provide the best return on your charitable investment? Definitionally, #1 is better if there are economies of scale, and #2 is better if there are diseconomies of scale. But which description best fits the real world?

My main thoughts: #1 is probably much more fun for the faculty. Being part of a center of like-minded folks beats being a lone voice in the wilderness. #1 also plausibly attracts more media attention. A Center of ten professors is more visible than ten isolated professors. However, #2 also has a big advantage: It avoids redundancy. When a lone pro-X professor converts a student, it's hard to say, "It would have happened even if this professor hadn't been hired." But if one out of ten pro-X professors converts a student, "It would have happened even if this professor hadn't been hired" is quite plausible.

Bonus question: Suppose #1 is definitely better than #2. If each school already has one pro-X professor, would it be worthwhile for a donor to give one school enough money to "poach" all the pro-X professors from the other schools? Could clustering really be that valuable?

Please show your work.

P.S. Thanks to all the great people I met in Ohio. I'll be back!

(22 COMMENTS)

April 12, 2015

The Libertarian Target, by Bryan Caplan

The self-conscious libertarian population is, to belabor the obvious, extremely small and politically unsuccessful. Serious libertarianism is so rare that very few surveys of political identity even bother to include a libertarian response option. There isn't a single 20th-century president or any ruling governor in the same philosophical ballpark as Milton Friedman. Certainly no more than five current members of Congress qualify. Probably none.

The puzzle: Why do high-profile thinkers keep energetically targeting such a marginalized viewpoint? As a self-conscious libertarian, I'm definitely not complaining. I welcome all the publicity, no matter how negative. But the publicity remains peculiar. What motivates the critics to attack libertarianism time after time? Top possibilities the critics might embrace:

1. Despite their rarity and absence on the front lines of politics, self-conscious libertarians still strongly shape mainstream conservative politicians' economic policies.

2. Self-conscious libertarians, though rare, have still managed to sharply shift public opinion in a libertarian direction.

3. Self-conscious libertarians, though politically impotent, are a symbol of what's wrong with American politics.

And then there are the stories the critics won't embrace, but perhaps they're true nonetheless...

4. Libertarians, unlike mainstream conservatives, openly defend many unpopular views. Intellectuals who want to loudly champion popular views have to engage libertarians because there's hardly anyone else to argue with.

5. Libertarian arguments, though mistaken, are consistently clever enough to get under the critics' skin. The purpose of the criticism is shielding the world from bad ideas but giving the critics some intellectual catharsis.

6. Libertarian arguments are good enough to weigh on the critics' intellectual consciences. They attack libertarians to convince themselves that we're wrong. And they keep attacking us because they keep failing to fully convince themselves.

Other stories?

P.S. My four-day Ohio tour at Bowling Green, Ohio State, Kenyon, and Oberlin starts tomorrow. If you attend any of my talks, please say hi.

(7 COMMENTS)

April 9, 2015

Krugman versus the Audit Heuristic, by Bryan Caplan

Krugman notes that there are four logically possible combinations of social liberalism and economic liberalism. He calls their adherents liberals (high on both), conservatives (low on both), libertarians (high on social liberalism, low on economic liberalism), and hardhats (low on social liberalism, high on economic liberalism). Since social liberalism and economic liberalism are positively correlated, the latter two categories are relatively rare. So far, so good. But then he leaps to the claim that the latter two categories are absolutely rare - about as rare as they'd be if social and economic liberalism were perfectly correlated. Krugman:

You might be tempted

to say that this is a vast oversimplification, that there's much more to

politics than just these two issues. But the reality is that even in

this stripped-down representation, half the boxes are basically empty...

"Basically empty"? Gallup, Pew, and the American National Election Studies all disagree. Cautious definitions put the libertarian share of the U.S. population at 9-14%. Broader definitions put the share much higher. Libertarians themselves have done most of the data analysis, but you don't have to trust us. Nate Silver concurs. Or check out some social and economic questions in the General Social Survey for yourself, and see how they correlate. For example:

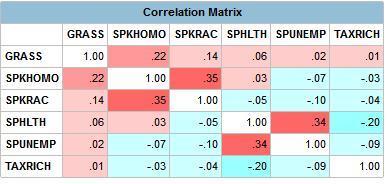

Social Questions

1. "Do you think the use of marijuana should be made legal or

not?" (GRASS, "Legal"=1, "Not legal"=2)

2. "Suppose this admitted homosexual wanted to make a speech in your

community. Should he be allowed to speak, or not?" (SPKHOMO, "Allowed"=1, "Not Allowed"=2)

3. "If such a person wanted to make a

speech in your community claiming that Blacks are inferior,

should he be allowed to speak, or not?" (SPKRAC, "Allowed"=1, "Not Allowed"=2)

Economic Questions

1. "Please indicate whether you would like to see more or less

government spending in each area. Remember that if you say 'much

more,' it might require a tax increase to pay for it. b. Health." (SPHLTH, "Spend much more"=1, "Spend more"=2, "Spend same"=3, "Spend less"=4, "Spend much less"=5)

2. "Please indicate whether you would like to see more or less

government spending in each area. Remember that if you say "much

more," it might require a tax increase to pay for it. g.

Unemployment benefits." (SPUNEMP, "Spend much more"=1, "Spend more"=2, "Spend game"=3, "Spend less"=4, "Spend much less"=5)

3. "Generally, how would you describe taxes in America

today... We mean all taxes together, including social security,

income tax, sales tax, and all the rest. a. For those with high

incomes, are taxes..." (TAXRICH,"Much too high"=1, "Too high"=2, "About right"=3, "Too low"=4, "Much too low"=5)

Here's the correlation matrix.

Mind the coding. On the social questions, lower answers are always more liberal. On the economic questions, lower answers are more liberal for spending, but more conservative for taxes. Social liberalism therefore statistically comes as a package, and so does economic liberalism. The correlations between the social and economic questions, however, are much smaller, and some have the wrong sign.

No doubt the low and irregular correlations partly reflect measurement error. As I've emphasized myself, low correlations between individual issues don't disprove the one-dimensional model. But even if you put responses on common scales and sum them to reduce measurement error, the correlation between social liberalism and economic liberalism is only .06. If you put in a hundred questions, measurement error would largely wash out, so you might get the correlation up to .2 or .3. But getting it up to .5 would be like pulling teeth. Plenty of data miners have tried! And with a .5 correlation, the libertarian and hardhat boxes remain very far from empty.

When I judge wide-ranging thinkers, I often use the following rule of thumb. Call it the Audit Heuristic.

1. Read what they say about a topic I know very well.

2. See how reliable they are on that topic.

3. Assume that they're about as reliable on topics I don't know well as they are on topics I do know well.

For the case at hand, Krugman fares poorly against the Audit Heuristic. I don't expect my favorite liberals to change their mind about him because one of his posts is mistaken. But my favorite liberals should at least admit that Krugman has given me reason to doubt his reliability. And I'd trust my favorite liberals more if they were quicker to concede Krugman's specific flaws rather than sing his general praises.

(18 COMMENTS)April 8, 2015

Kevin Carey's The End of College: Wrong But Beautiful, by Bryan Caplan

I've already explained why Carey's wrong about the prognosis for higher education. I'll bet on it. Online education primarily competes with blogs, not colleges. I was pleased, however, that Carey shines a spotlight on the subsidies the status quo enjoys:

When it comes to teaching, colleges and universities do not want to be more productive, and will do whatever they can to avoid such a fate.I don't think subsidies are the sole cause of lock-in; I also blame conformity signaling. But I'm delighted that Carey is calling shenanigans on taxpayer support for the status quo. (If he expands his critique to government support for K-12 education, I'll be ecstatic).

The question is why, unlike newspapers, travel agencies, record labels, and countless other industries, they were able to get away with it. The answer lies with public subsidies and regulations. The higher-education industry receives hundreds of billions of dollars every year in the form of direct appropriations, tax preferences (Harvard pays no taxes on its $33 billion endowment), and subsidies for their customers in the form of government scholarships and guaranteed student loans. The only way to get that money is to be an accredited college. And the accreditation system is controlled by the existing colleges themselves, who set the standards for which organizations are eligible for public funds. Those standards typically include things like hiring faculty who have degrees from an existing college and constructing a library full of books. It's like a world where Craigslist needs the local newspaper's permission to give online classified ads away for free, or Honda has to build cars exactly like GM.

What's so beautiful about Carey's vision? Because he loves education the way it should be loved - and realizes that online education is far more lovable than conventional education.

But liberal education? If you take its meaning at all seriously, liberal education is the work of a lifetime.Amen! Sadly, though, only a handful of nerds sincerely seek "liberal education." 5% of college students, tops - even at the best schools in the world. The rest is Social Desirability Bias and careerism.

[...]

The current higher-education business model consists of charging students and their parents a great deal of money for a short amount of time and then maintaining an ongoing relationship based on youthful nostalgia, tribal loyalty, professional sports entertainment, and occasional begging for donations...

To prosper, colleges need to become more like cathedrals. They need to build beautiful places, real and virtual, that learners return to throughout their lives. They need to create authentic human communities and form relationships with people based on the never-ending project of learning... The idea of "applying to" and "graduating from" colleges won't make as much sense in the future. People will join colleges and other learning organizations for as long or as little time as they need.

Large numbers of learners make this possible. When you talk to professors teaching MOOCs, none of them say they're doing it to make a lot of money or advance their careers. Instead, they're thrilled by the prospect of reaching tens of thousands of people all over the world who want to learn, of seeing how their ideas resonate in different cultural contexts, of experimenting in ways that were never possible before the advent of technology.

(10 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers