Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 118

July 21, 2015

Is an Unused J.D. a Negative Signal?, by Bryan Caplan

Chapter 5, "The Myth of the Versatile Law Degree" is the book's single best chapter. Thesis: "It's quite true you can do many things if you have a law degree. The problem is that you can also do all those things if you don't have a law degree - except practice law." Campos then points out J.D.'s high rate of malemployment - ending up in jobs that don't actually require their credential.

My immediate reaction: Given the power of educational signaling, couldn't an unused law degree be vocationally useless but financially valuable? Campos anticipates the objection:

When tracking employment outcomes for law graduates, the ABA maintains a category of so-called "JD advantage" jobs - positions that don't require a law degree, but which are categorized by the graduates who obtain them or by the law schools who report the data as jobs where the graduate's JD played a role in obtaining it. (In 2012, 9% of new law graduates were categorized as employed in such jobs nine months after graduation - with how much accuracy it's difficult to say).Statistical support? None. But I'm inclined to trust Campos nonetheless. Question for readers with first-hand experience in the J.D. job market: Does Campos story ring true?

But there's a flip side to claims, whether accurate or not, that a JD helped someone get a non-legal job: jobs that people aren't able to get precisely because they have a law degree.

There's a great deal of evidence that suggests this category is actually quite a bit larger than the JD advantage category - that, in other words, on balance having a JD does more harm than good to the law school graduate who, by choice or necessity, is trying to get a job outside the legal profession. Rather than being a versatile degree, many graduates discover that a JD can be a toxic asset - one which they end up having to purge from their resume in order to move on with their careers once they've given up on entering and staying inside the legal profession.

... Four factors help transform law degrees into toxic assets for law school graduates who try to obtain work outside the legal profession:

(1) Non-legal employers assume that an applicant with a law degree is just marking time until he or she leaves for one of the many high-paying legal jobs that non-lawyers mistakenly believe most people with law degrees hold...

(2) Non-legal employers naturally wonder why someone with a law degree doesn't want to - or worse yet can't - practice law...

(3) Non-legal employers don't like the idea of hiring someone who they imagine will have a sophisticated understanding of employment law...

(4) Non-lawyers don't like lawyers.

Time and again, in the course of studying the collapsing market for both law graduates and experienced lawyers, I have encountered people who tell some variation of the same story: after a year, or two, or longer, of trying unsuccessfully to establish or maintain a legal career, the person started looking seriously for non-legal jobs. Remarkably often, these stories have the same conclusion: not until these people removed their law degree from their resumes were they able to begin to have some success in securing any non-legal job.

P.S. If you know of any relevant statistical evidence for or against Campos, please share URLs in the comments.

(21 COMMENTS)

July 20, 2015

Testing Unflattering Claims About Human Motivation, by Bryan Caplan

Personally, I believe that 80% of everyone's accusations are true. Of course Democrats resent the rich. Of course Republicans disdain the poor. But maybe I'm just being contrarian. Is there any fair-minded way to advance the conversation?

I think so. A vast number of surveys include Feeling Thermometers. A typical wording from the General Social Survey:

I'd like to get your feelings toward groups that are in theMy prediction: Standard Feeling Thermometer questions will support at least 80% of common motivational accusations in relative terms. Democrats will have noticeably colder views of the rich than Republicans. Republicans will have noticeably colder views of the poor than Democrats. And so on.

news these days. I will use something we call the feeling

thermometer, and here is how it works: I'll read the names of a

group and I'd like you to rate that group using the feeling

thermometer. Ratings between 50 degrees and 100 degrees mean

that you feel favorable and warm toward the group. Ratings

between 0 degrees and 50 degrees mean that you don't feel

favorable toward the group and that you don't care too much for

that group.

My word of honor: As I write, I have never played with this data. I am making an honest-to-goodness Assert First, Look Afterward prediction. My question for readers of all factions: Before you know the answers, are you willing to admit that Feeling Thermometers are an informative way to put unflattering claims about human motivation to the test?

If you have any intellectual reputation to bet, please "go on the record" in the comments.

(18 COMMENTS)

Resentment, Information, and Unemployment, by Bryan Caplan

PerhapsThe problem? From context, it sounds like there's symmetric information about resentment, so each individual's resentment causes his own unemployment. In reality, though, there's asymmetric information about resentment, so the average resentment poor workers feel causes unemployment for poor workers in general, including poor workers who are perfectly content.

low-skilled workers cannot be employed at lower wages because their

resentment at the low wage would be so high that they would impose

unacceptable morale costs on the organizations employing them. In other

words, insult them with a sub-par wage offer and they turn destructive

toward the entire organization. Companies of course prefer to keep

these workers at arms' length under this hypothesis.

Think about it like this. A firm asks job candidates, "You earned $15 per hour in your last job. This job pays $10 an hour, but you'll work side-by-side with other workers who earn $15 an hour to do the same job you'll be doing. Are these conditions going to make you resentful, reducing your productivity to less than $10 an hour?" Almost every candidate will respond, "Of course not! I just want to work." But many of these candidates are lying - to the interviewer and possibly themselves. Since firms have trouble telling the liars from the truth-tellers, hiring anyone may be unprofitable. If so, a worker who genuinely feels zero resentment, who is worth more than the market wage, ends up involuntarily unemployed.

How the math works: Suppose that in the preceding example, resentful workers produce $5 per hour, while content workers produce $11 per hour. There are two resentful workers for every content worker. With symmetric information, the firm will hire the one-third of workers who are content, and spurn the rest. If the firm can't distinguish the two types of workers in advance, however, the firm will look at the expected hourly productivity of $(2/3*5+1/3*11)=$7 and hire no one.

Why not just cut the wage to $7? The minimum wage aside, cutting the wage to $7 will provoke even more resentment. Resentful workers' productivity might fall to $2, and the share of content workers might fall to 10%, reducing expected productivity to $2.90. And so on. As I've said before, "Encouraging individual workers to be more flexible in their wage

expectations is still helpful advice. But it would be even more helpful

for the average worker if the average worker became more flexible."

(4 COMMENTS)

July 16, 2015

You Grew Up in Poverty? Okay, Here's Some Money, by Bryan Caplan

The goal of the program, of course, is to (a) help people who are statistically likely to be poor, and (b) partially equalize cumulative lifetime well-being by making adult income higher if your childhood income was low.

What's special about the program: It closely targets the statistically poor with minimal disincentive effect. Poor parents can't make money by having extra kids, because minors receive nothing. The checks start coming once the poor kids are legally adults. The recipients retain normal incentives to acquire skills and work, because the size of the checks depends on their family income when they were kids, not their current income. The program might slightly discourage teen labor, but that's about it.

I'm against this program, of course. But why would normal people oppose it?

(13 COMMENTS)

July 15, 2015

What's Wrong With the U.S. Peace Movement, by Bryan Caplan

Reading Michael Heaney and Fabio Rojas' excellent new Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11 (Cambridge University Press, 2015) confirms many of my deepest misgivings about the U.S. peace movement. The book begins with a puzzle: Democrats' war policies were very similar so those of their Republican predecessors, but the antiwar movement still durably dissolved once the Democrats gained power:

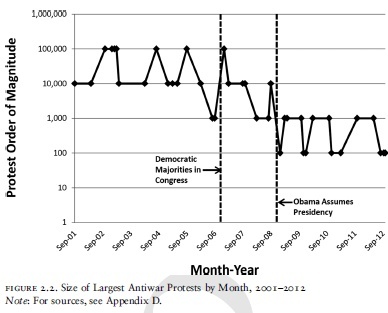

The antiwar movement became a mass movement from 2001 to 2006, as Democratic Party loyalty and anti-Bush sentiment provided fuel for the movement. However, the 2006 elections and their immediate aftermath were the high point for party-movement synergy. At exactly the time when antiwar voices were most well poised to exert pressure on Congress, movement leaders stopped sponsoring lobby days. The size of antiwar protests declined. From 2007 to 2009, the largest antiwar rallies shrank from hundreds of thousands of people to thousands, and then to only hundreds. Congress considered antiwar legislation, but mostly failed to pass it. In 2008, the Democrats nominated an antiwar presidential candidate in U.S. Senator Barack Obama (D-IL). But once Obama became president, his policies on war and national security resembled those of his Republican predecessor, President George W. Bush.In case these patterns are in doubt, check out the data on antiwar protest size and media coverage:

Drawing on a a vast number of original surveys -

most conducted in the midst of antiwar protests - Heaney and Rojas reach

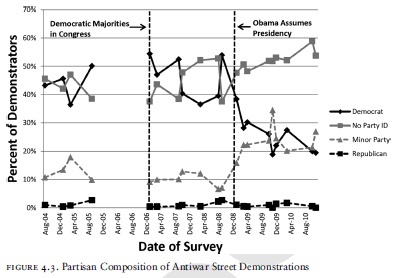

a cynical resolution of the puzzle: Democrats energized the antiwar movement, then dropped it as soon as

their side regained power. "We observe demobilization not in response to a policy victory, but in response to a party victory." Why? Because Democrats' real target was not war, but Republicans. The authors present wide-ranging evidence, but I'm impressed by this simple graph of partisan breakdown over time.

Since total participation was sharply falling, the overwhelming majority of Democratic protestors simply lost interest as their side gained power. Heaney and Rojas strive to be diplomatic, but read between the lines:

When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, the antiwar movement may or may not have gained an ally in the White House. However, it definitely lost its prime enemy: President Bush. The antiwar movement had relied on Bush as a mobilizing meme for almost eight years. For example, the radical antiwar organization World Can't Wait had adopted "Drive Out the Bush Regime!" as its slogan (Sweet 2008), though it never adopted the slogan "Drive Out the Obama Regime!" With Bush leaving the White House, some activists may have felt that their goal had been achieved...The great Bastiat once wrote, "The worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended." Though they're too polite to come out and say it, Heaney and Rojas' book shows that the good cause of peace was not merely ineptly defended, but insincerely defended. While the peace movement no doubt includes some honest-to-goodness pacifists, they're honorable outliers. The peace movement was not about peace.

Activists in the antiwar movement cared about the substance of foreign policy. They wanted more than just a change of party. However, for many of them, partisanship served as a lens through which to see policy. On the most basic level, Obama had promised a withdrawal from Iraq. Perhaps it would require substantial grassroots pressure to compel him to keep this promise. But for self-identified Democrats, it might also make sense to trust Obama to keep his word without actively applying pressure. These activists might not necessarily look closely at the details of the administration's policies. Yet, even if they did, they would find considerable ambiguity, leaving room for interpretation. While it was possible to consider Obama's policies to be mostly prowar, it was also possible to see them as antiwar. Self-identified Democrats might have been more likely to see Obama's policies in an antiwar light than non-Democrats would have. They might also be more likely than non-Democrats to make excuses for the president's policies, seeing them as the only practical option under the circumstances.

The period from 2001 to 2012 was a time of shifting identities for Democrats and antiwar activists. The initial shift occurred from 2001 through 2003, as Democratic identities began to be coupled with antiwar identities. Democratic identities raised the salience of antiwar identities, and vice versa. From 2003 to 2006, antiwar and Democratic identities were (mostly) self-reinforcing. However, starting in 2007, antiwar and Democratic identities began to conflict with one another. For some activists, the emergence of Democratic majorities in Congress was enough to satisfy their demand for change. Others, however, were troubled when Congress not only failed to use its power of the purse to end the war in Iraq, but also voted for supplemental appropriations to fund Bush's surge in Iraq. Likewise, once Obama became president, his promises of withdrawal from Iraq were good enough for some. Others were troubled by the prolonged timetable in Iraq, negotiations to extend the SOFA, the escalation in Afghanistan, the administration's liberal use of drones, the U.S. intervention in Libya, and the president's unsuccessful efforts to close the controversial U.S. prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Activists were increasingly compelled to choose between their identities. "Am I a Democrat? Or am I an antiwar activist?" It became difficult to be both.

The bad news for the antiwar movement was that activists were more likely to favor their Democratic identities over their antiwar identities. Especially once Obama became president, there were too many good reasons to be a Democrat.The country had its first African American in the Oval Office, an important symbolic outcome after centuries of struggle for racial equality. The Democratic majority in Washington - which was nearly a supermajority - meant that comprehensive health care reform would stand a real chance for the first time in fifteen years. Thus, many former antiwar activists shifted their attention to other issues on the progressive agenda.

(37 COMMENTS)

July 14, 2015

Party in the Street and the Party in Their Heads, by Bryan Caplan

Michael Heaney and Fabio Rojas' new Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party After 9/11 (Cambridge University Press, 2015) is packed with wide-ranging insight. The data collection alone inspires awe: The authors surveyed practically every major antiwar rally from 2004 to 2010, then collected further data on the Tea Party and Occupy movements to test the generality of their results.

My favorite part, though, is their dispassionate analysis of foreign policy under Bush versus Obama. Like me, Heaney and Rojas conclude that the differences between Democrats and Republicans are largely rhetorical - in the heads of partisans rather than the actions of their parties:

In comparing the similarities and differences between the Bush and Obama administrations on war policies in Iraq and Afghanistan, we find more continuity than change in policy. The large decline in forces in Iraq, as well as their ultimate withdrawal, were set in motion during the Bush administration. With respect to Iraq, the Obama administration largely carried out the Bush administration's policy without substantially changing direction. As we explain later, there may be some dispute about how differently the two administrations would have negotiated to extend the final Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) in Iraq. It is possible to argue that the Obama administration was somewhat less prowar with respect to the SOFA than another Republican administration would have been, but it is also possible that the two administrations would have ultimately reached the same or similar agreements. It seems possible that a Republican administration would have called for an increase of troops in Afghanistan, as did the Obama administration, but it would be reasonable to argue that Obama's increase was greater than would have been undertaken by a Republican administration. Regardless of which argument the reader finds most plausible, the differences between the administrations are subtle. At best, the Obama administration was slightly more peaceful than another Republican administration likely would have been. At worst, the Obama administration was somewhat more bellicose.Details on Iraq:

The declining violence in Iraq, as well as the surge that presumably brought about the decline, provided the backdrop for new negotiations between the United States and the Government of Iraq. On November 26, 2007, Bush and Prime Minister Maliki signed a Declaration of Principles that was the beginning of negotiations to disengage U.S. troops from Iraq (Mason 2009). They agreed that the objective of cooperation between the United States and the Government of Iraq was to train, equip, and arm the Iraqi government so that Iraq could take primary responsibility for its own security (White House 2007b). In a July 2008 interview, Maliki predicted that Iraq would shortly reach an agreement with the Bush administration on a timetable for withdrawal (M��ller von Blumencron and Zand 2008).Details on Afghanistan:

In keeping with Maliki's prediction, and after months of negotiations, the United States and Iraq signed a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) on November 17, 2008. A SOFA is a legal agreement between the United States and the government of another nation that allows the U.S. military to operate within that nation. The SOFA stipulated that U.S. forces would legally operate within Iraq only until December 31, 2011. Thus, the Bush administration had laid the foundation for the withdrawal of the U.S. military from Iraq.

Barack Obama campaigned for president advocating a sixteen-month timetable for withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq (Bohan 2008). This timetable would have sent all U.S. troops home in April 2010, a full twenty months earlier than promised in the SOFA. However, once in office, the Obama administration largely followed the timetable set out in the SOFA signed by the Bush administration, although there were some delays in meeting the intermediate withdrawal targets (Whitlock 2010). Under the Obama administration, the United States accomplished a partial withdrawal by August 2010, and then a full withdrawal by the scheduled December 2011 departure date (Robinson 2011). Even though military forces left the country, the United States retained its embassy in Baghdad with approximately seventeen thousand personnel; its consulates in Basra, Mosul, and Kirkuk with one thousand staff each; and thousands of military contractors (Denselow 2011).

One wrinkle in the story that Obama essentially followed the Bush timeline for withdrawal is that the Obama administration commenced negotiations with the Maliki government to extend the presence of U.S. troops beyond what Bush had agreed to in the SOFA. As the deadline for withdrawal approached, U.S. officials worried that Iraq had not achieved sufficient stability to maintain security without the U.S. military presence. To address this problem, U.S. negotiators sought an extension of the SOFA (Katzman 2012, p. 38). Prime Minister Maliki indicated that he would be willing to support the request for an extension if the proposal could gain the support of 70 percent or more of Iraq's Council of Representatives (Davis 2011). When it appeared likely that Iraq's government would grant the necessary approval, officials in the Obama administration began discussing the parameters of the U.S. presence, which would have likely consisted of approximately fifteen thousand troops (Katzman 2012, p. 38). However, Iraq issued a statement on October 5, 2011, that it would permit U.S. troops to remain in Iraq, but they would not have the legal protections granted by the SOFA, making them subject to the jurisdiction of Iraqi courts (Katzman 2012, p. 39). As a result, President Obama announced that all U.S. troops would leave Iraq by the end of 2011, in accordance with the existing SOFA. U.S. troops left Iraq because of Iraq's unwillingness to extend the legal protections of the SOFA, not because of the preferences of the Obama administration (Dreazen 2011). Nevertheless, during his 2012 campaign for reelection, Obama cited the full withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Iraq as one of his administration's major accomplishments (Obama 2012).

Obama's position on Afghanistan allowed him to claim during the election that he was simultaneously antiwar (regarding Iraq) and prowar (regarding Afghanistan), thus enabling him to appeal to a broad segment of the electorate. By splitting the difference between the wars, Obama may have hoped to appear flexible on foreign policy issues.This historical analysis lays the groundwork for the rest of book. The puzzle: If foreign policy remained quite stable between Bush and Obama, why did the antiwar movement almost completely dissolve as soon as Obama took the reigns? Tune in tomorrow for Heaney and Rojas' answer...

Once in office, Obama was in a position to put his vision into practice. While it would have been possible for him to walk away from his campaign pledge regarding Afghanistan, the president and his leading advisers (with the notable exception of Vice President Joe Biden) instead agreed to conduct a surge in Afghanistan analogous to the one that Bush authorized in Iraq. As presidential historian Andrew Polsky (2012, p. 332) recounts, they "envisioned a kind of Baghdad II, a troop surge of indefinite duration in which American forces and their NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] allies would practice 'seize, hold, and build' tactics to bring population security and economic development to rural Afghanistan." This strategy led to an increase of troops in Afghanistan from roughly 35,000 when Obama took office to a peak of 100,000 between August 2010 and April 2011 (Livingston and O'Hanlon 2012, p. 4). This increase of 65,000 troops far exceeded the two to three brigades (a maximum of about 15,000 troops) proposed by Obama during the election campaign.

More than just increasing the number of troops present, Obama's surge brought about a change in policy. Rather than focusing only on counterterrorism, the surge aimed to degrade the capacity of the Taliban so that the Afghan central government might exert greater control of its territory (Polsky 2012, p. 336). Despite these efforts, insurgent-initiated violence spiked in Afghanistan during the surge. American troops were subject to more attacks by insurgents in 2010 than in any other year of the occupation, making 2010 the deadliest year on record for American troops in Afghanistan (Livingston and O'Hanlon 2012, pp. 10-11). In September 2014, the United States and Afghanistan signed a new Bilateral Security Agreement to maintain the presence of U.S. troops for another six years (Walsh and Ahmed 2014).

When looking at the record of the Obama administration, it is obvious that it cannot be characterized as "antiwar" with respect to its policy in Afghanistan. In the first four years of the administration, 1,530 U.S. service members died in Afghanistan, almost three times the number (630) who died in Afghanistan during all eight years of the Bush administration (Livingston and O'Hanlon2012, p. 11). It is possible that a hypothetical President McCain would have reached exactly the same policy decision as did Obama. After all, McCain did promise to increase troops in Afghanistan. However, given that Obama increased troop levels far above what was discussed in the election, and the fact Obama used the Afghanistan issue as a way of distinguishing himself as a candidate, it also seems plausible that Obama's surge was uniquely his doing.

(19 COMMENTS)

Anthropology Versus Commodification, by Bryan Caplan

...we present a range of sociological and anthropological evidence that

there is no essential meaning to money or market exchange. Instead, the

meaning of money is a contingent social construct. In the absence of

non-semiotic objections to markets, the social meaning of money, of

markets, and commodification, is relative, not objective. Note that we

are not saying that morality is relative or a social construct, but, rather that the meaning we attach to market exchanges is.

[...]

There are facts about what symbols, words, and actions signal

respect. But--when there are no worries about exploitation, harm, rights,

and so on--these facts appear to vary from culture to culture. Consider

that King Darius of Persia asked the Greeks if they would be willing to

eat the dead bodies of their fathers. The Greeks balked. Of course, the

right thing to do was to burn the dead bodies on a funeral pyre. To eat

the dead would disrespect them, treating them like mere food. Darius

then asked the Callatians if they would be willing to burn their fathers

on a funeral pyre. The Callatians balked. The thing to do was to eat

one's father, so that part of the father was always with the son.

Burning the dead would treat them like mere trash.

The Greeks and Callatians agreed about what their obligations were.

They agreed that everyone has a moral obligation to signal respect for

their dead fathers... The issue

here is just that the Greeks and Callatians were, in effect, speaking

different (ritualistic) languages... Asking whether the Greek or Callatian practices are the

correct way to express respect is, at first glance, a bit like asking

whether English or French is the correct language.

Personally, I like the idea of being eaten by my family and friends after I die. But if that's not your thing, don't sweat it. :-)

Change My View: A Data Opportunity?, by Bryan Caplan

Hey

Prof. Caplan,

I

have been reading your recent posts on econlog about the lack of research on

debating tactics, and I wanted to propose a potential research avenue that you

or someone you know might be interested in.

I

moderate a forum on Reddit called "change my view" which is

essentially a debate forum, but specifically focused on people who have a view

but are open to changing it. As a part of the forum, we have a protocol

for people to note and reward changes in their views. Essentially, if

someone's post changes your view, you include a greek delta symbol in the

comment, and a bot comes around and gives the person who changed your view some

internet points.

You

can access the site here: https://www.reddit.com/r/changemyview

The

upshot of all this is that we have a tabulation of thousands of debates, and

thousands of posts within those debates which were effective at changing

someone's view. I don't know exactly how to methodologically turn that

into a useful conclusion about what's effective, but I figure you or one of

your students or colleagues might be interested in giving it a crack.

Good

luck in your future debating endeavors.

Best,

Peter

Hurley

[Bryan again]

Sample bias is the obvious problem. People who frequent this reddit are almost certainly unusual human beings. But I still like the idea. If anyone makes a serious go of it, I will blog it.

(11 COMMENTS)

July 13, 2015

David on Debate, by Bryan Caplan

1. David adds a principle to my list:

Admit when you're wrong. Or, even if the person on the otherI fully agree.

side hasn't convinced you that you're wrong, but has made you have

doubts, admit that you have doubts.

2. David's other main observation: "Appeals to emotion can be sleazy, but they're not necessarily sleazy."

My initial reaction was to disagree, but David's presentation gave me some doubts. On third thought, though, I stand by my original claim.

Key point: What counts as an "appeal to emotion"? It can't merely be any claim expected to produce a favorable emotion in the audience. By that standard, after all, virtually every statement a debater bothers to make constitutes an appeal to emotion. The standard meaning is much narrower. As Wikipedia puts it:

Appeal to emotion or argumentum ad passiones is a logical fallacy characterized by the manipulation of the recipient's emotions in order to win an argument, especially in the absence of factual evidence.The "especially in the absence of factual evidence" clause is fundamental.

Doesn't my Haitian example still qualify? As a moral realist who believes in moral facts, I say no. The flip side, incidentally, is that if you're a moral anti-realist, debating morality requires logical fallacy. But that's your problem!

(1 COMMENTS)

July 12, 2015

Return to the Caplan-Somin Foreign Policy Debate, by Bryan Caplan

P.S. Ilya and Alison Somin had their first child last month. May Somins blanket the earth!

(0 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers